Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Currently showing reports relevant to the Environment and Communications Senate estimates committee. [Remove filter]

Executive summary

1. Performance information is important for public sector accountability and transparency as it shows how taxpayers’ money has been spent and what this spending has achieved. The development and use of performance information is integral to an entity’s strategic planning, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation processes.

2. Annual performance statements are expected to present a clear, balanced and meaningful account of how well an entity has performed against the expectations it set out in its corporate plan. They are an important way of showing the Parliament and the public how effectively Commonwealth entities have used public resources to achieve desired outcomes.

The needs of the Parliament

3. Section 5 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) sets out the objects of the Act, which include requiring Commonwealth entities to provide meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public. The Replacement Explanatory Memorandum to the PGPA Bill 2013 stated that ‘The Parliament needs performance information that shows it how Commonwealth entities are performing.’1 The PGPA Act and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) outline requirements for the quality of performance information, and for performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

4. The Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) has a particular focus on improving the reporting of performance by entities. In September 2023, the JCPAA tabled its Report 499, Inquiry into the Annual Performance Statements 2021–22, stating:

As the old saying goes, ‘what is measured matters’, and how agencies assess and report on their performance impacts quite directly on what they value and do for the public. Performance reporting is also a key requirement of government entities to provide transparency and accountability to Parliament and the public.2

5. Without effective performance reporting, there is a risk that trust and confidence in government could be lost (see paragraphs 1.3 to 1.6).

Entities need meaningful performance information

6. Having access to performance information enables entities to understand what is working and what needs improvement, to make evidence-based decisions and promote better use of public resources. Meaningful performance information and reporting is essential to good management and the effective stewardship of public resources.

7. It is in the public interest for an entity to provide appropriate and meaningful information on the actual results it achieved and the impact of the programs and services it has delivered. Ultimately, performance information helps a Commonwealth entity to demonstrate accountability and transparency for its performance and achievements against its purposes and intended results (see paragraphs 1.7 to 1.13).

The 2023–24 performance statements audit program

8. In 2023–24, the ANAO conducted audits of annual performance statements of 14 Commonwealth entities. This is an increase from 10 entities audited in 2022–23.

9. Commonwealth entities continue to improve their strategic planning and performance reporting. There was general improvement across each of the five categories the ANAO considers when assessing the performance reporting maturity of entities: leadership and culture; governance; reporting and records; data and systems; and capability.

10. The ANAO’s performance statements audit program demonstrates that mandatory annual performance statements audits encourage entities to invest in the processes, systems and capability needed to develop, monitor and report high quality performance information (see paragraphs 1.18 to 1.27).

Audit conclusions and additional matters

11. Overall, the results from the 2023–24 performance statements audits are mixed. Nine of the 14 auditees received an auditor’s report with an unmodified conclusion.3 Five received a modified audit conclusion identifying material areas where users could not rely on the performance statements, but the effect was not pervasive to the performance statements as a whole.

12. The two broad reasons behind the modified audit conclusions were:

- completeness of performance information — the performance statements were not complete and did not present a full, balanced and accurate picture of the entity’s performance as important information had been omitted; and

- insufficient evidence — the ANAO was unable to obtain enough appropriate evidence to form a reasonable basis for the audit conclusion on the entity’s performance statements.

13. Where appropriate, an auditor’s report may separately include an Emphasis of Matter paragraph. An Emphasis of Matter paragraph draws a reader’s attention to a matter in the performance statements that, in the auditor’s judgement, is important for readers to consider when interpreting the performance statements. Eight of the 14 auditees received an auditor’s report containing an Emphasis of Matter paragraph. An Emphasis of Matter paragraph does not modify the auditor’s conclusion (see Appendix 1).

Audit findings

14. A total of 66 findings were reported to entities at the end of the final phase of the 2023–24 performance statements audits. These comprised 23 significant, 23 moderate and 20 minor findings.

15. The significant and moderate findings fall under five themes:

- Accuracy and reliability — entities could not provide appropriate evidence that the reported information is reliable, accurate and free from bias.

- Usefulness — performance measures were not relevant, clear, reliable or aligned to the entity’s purposes or key activities. Consequently, they may not present meaningful insights into the entity’s performance or form a basis to support entity decision making.

- Preparation — entity preparation processes and practices for performance statements were not effective, including timeliness, record keeping and availability of supporting documentation.

- Completeness — performance statements did not present a full, balanced and accurate picture of the entity’s performance, including all relevant data and contextual information.

- Data — inadequate assurance over the completeness, integrity and accuracy of data, reflecting a lack of controls over how data is managed across the data lifecycle, from data collection through to reporting.

16. These themes are generated from the ANAO’s analysis of the 2023–24 audit findings, and no theme is necessarily more significant than another (see paragraphs 2.12 to 2.17).

Measuring and assessing performance

17. The PGPA Rule requires entities to specify targets for each performance measure where it is reasonably practicable to set a target.4 Clear, measurable targets make it easier to track progress towards expected results and provide a benchmark for measuring and assessing performance.

18. Overall, the 14 entities audited in 2023–24 reported against 385 performance targets in their annual performance statements. Entities reported that 237 targets were achieved/met5, 24 were substantially achieved/met, 24 were partially achieved/met and 82 were not achieved/met.6 Eighteen performance targets had no definitive result.7

19. Assessing entity performance involves more than simply reporting how many performance targets were achieved. An entity’s performance analysis and narrative is important to properly inform stakeholder conclusions about the entity’s performance (see paragraphs 2.37 to 2.44).

Connection to broader government policy initiatives

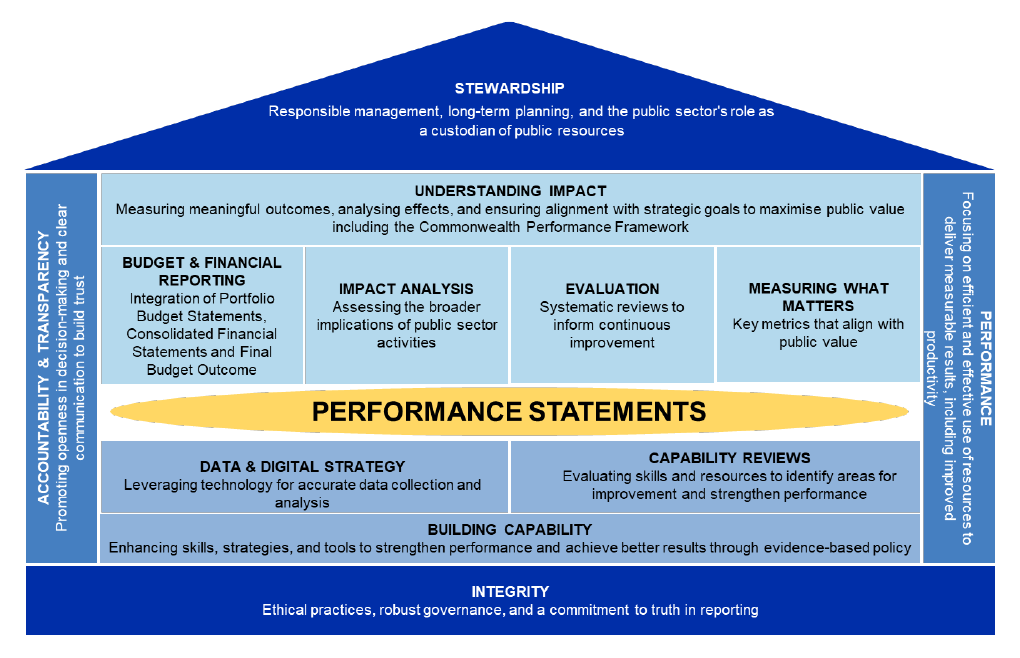

20. Performance statements audits touch many government policies and frameworks designed to enhance government efficiency, effectiveness and impact, and strengthen accountability and transparency. This is consistent with the drive to improve coherence across the Commonwealth Government’s legislative and policy frameworks that led to the PGPA Act being established.8 The relationship between performance statements audits and existing government policies and frameworks is illustrated in Figure S.1.

Figure S.1. Relationship of performance statements audits to government policies and frameworks

Source: ANAO analysis.

The future direction of annual performance statements audits

21. Public expectations and attitudes about public services are changing.9 Citizens not only want to be informed, but also to have a say between elections about choices affecting their community10 and be involved in the decision-making process, characterised by, among other things, citizen-centric and place-based approaches that involve citizens and communities in policy design and implementation.11 There is increasing pressure on Commonwealth entities from the Parliament and citizens demanding more responsible and accountable spending of public revenues and improved transparency in the reporting of results and outcomes.

22. A specific challenge for the ANAO is to ensure that performance statements audits influence entities to embrace performance reporting and shift away from a compliance approach with a focus on complying with minimum reporting requirements or meeting the minimum standard they think will satisfy the auditor.12 A compliance approach misses the opportunity to use performance information to learn from experience and improve the delivery of government policies, programs and services.

23. Performance statements audits reflect that for many entities there is not a clear link between internal business plans and the entity’s corporate plan. There can be a misalignment between the information used for day-to-day management and governance of an entity and performance information presented in annual performance statements. Periodic monitoring of performance measures is also not an embedded practice in all Commonwealth entities. These observations indicate that some entities are reporting measures in their performance statements that may not represent the highest value metrics for running the business or for measuring and assessing the entity’s performance (see paragraphs 4.32 to 4.35).

Developments in the ANAO’s audit approach

24. Working with audited entities, the ANAO has progressively sought to strengthen sector understanding of the Commonwealth Performance Framework. This includes a focus on helping entities to apply general principles and guidance to their own circumstances and how entities can make incremental improvements to their performance reporting over time. For example:

- in 2021–22, the ANAO gave prominence to ensuring entities understood and complied with the technical requirements of the PGPA Act and the PGPA Rule;

- in 2022–23, there was an increased focus on supporting entities to establish materiality policies that help determine which performance information is significant enough to be reported in performance statements and to develop entity-wide performance frameworks; and

- in 2023–24, there was an increased focus on assessing the completeness of entity purposes, key activities and performance measures and whether the performance statements present fairly the performance of the entity (see paragraphs 4.36 to 4.38).

Appropriate and meaningful

25. For annual performance statements to achieve the objects of the PGPA Act, they must present performance information that is appropriate (accountable, reliable and aligned with an entity’s purposes and key activities) and meaningful (providing useful insights and analysis of results). They also need to be accessible (readily available and understandable).

26. For the 2024–25 audit program and beyond, the ANAO will continue to encourage Commonwealth entities to not only focus on technical matters (like selecting measures of output, efficiency and effectiveness and presenting numbers and data), but on how to best tell their performance story. This could include analysis and narrative in annual performance statements that explains the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind the reported results and providing future plans and initiatives aligned to meeting expectations set out in the corporate plan.13

27. It is difficult to demonstrate effective stewardship of public resources without good performance information and reporting. Appropriate and meaningful performance information can show that the entity is thinking beyond the short-term. It can show that the entity is committed to long-term responsible use and management of public resources and effectively achieving results to create long lasting impacts for citizens (see paragraphs 4.39 to 4.45).

Linking financial and performance information

28. The ‘Independent Review into the operation of the PGPA Act’14 noted that there would be merit in better linking performance and financial results, so that there is a clear line of sight between an entity’s strategies and performance and its financial results.15

29. Improving links between financial and non-financial performance information is necessary for measuring and assessing public sector productivity. As a minimum, entities need to understand both the efficiency and effectiveness of how taxpayers’ funds are used if they are to deliver sustainable, value-for-money programs and services. There is currently limited reporting by entities of efficiency (inputs over outputs) and even less reporting of both efficiency and effectiveness for individual key activities.

30. Where entities can demonstrate that more is produced to the same or better quality using fewer resources, this reflects improved productivity.

31. The ANAO will seek to work with the Department of Finance and entities to identify opportunities for annual performance statements to better link information on entity strategies and performance to their financial results (see paragraphs 4.46 to 4.51).

Cross entity measures and reporting

32. ANAO audits are yet to see the systemic development of cross-sector performance measures as indicators where it has been recognised that organisational performance is partly reliant on the actions of other agencies. Although there are some emerging better practices16, the ANAO’s findings reveal that integrated reporting on cross-cutting initiatives and linked programs could provide Parliament, government and the public with a clearer, more unified view of performance on key government priorities such as:

- Closing the Gap;

- women’s safety;

- housing;

- whole-of-government national security initiatives; and

- cybersecurity.

33. Noting the interdependence, common objectives and shared responsibility across multiple government programs, there is an opportunity for Commonwealth entities to make appropriate reference to the remit and reporting of outcomes by other entities in annual performance statements. This may enable the Parliament, the government and the public to understand how the work of the reporting entity complements the work done by other parts of government.17

34. As the performance statements audit program continues to broaden in coverage, there will be opportunities for the ANAO to consider the merit of a common approach to measuring performance across entities with broadly similar functions, such as providing policy advice, processing claims or undertaking compliance and regulatory functions. A common basis for assessing these functions may enable the Parliament, the government and the public to compare entities’ results and consider which approaches are working more effectively and why (see paragraphs 4.52 to 4.56).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Murray–Darling Basin (the Basin) is a system of interconnected rivers and lakes in the south-east of Australia with significant environmental, cultural and economic value.

2. The Murray–Darling Basin Plan (the Basin Plan) was developed in 2012 in response to a significant period of drought in the Basin in the early 2000s (the Millennium Drought), which resulted in a recognition across the governments that a plan was needed to manage the Basin’s water resources carefully and protect the Basin for future generations. The Basin Plan sets limits on the amount of water that can be taken from the Basin for consumptive purposes by communities, farmers and businesses, while maintaining environmental sustainability, known as the Sustainable Diversion Limits (SDLs).

3. The establishment of the SDLs was accompanied by a water recovery target to ‘bridge the gap’ between the SDLs and how much water was taken from the Basin before the introduction of the Basin Plan. At the time the Basin Plan was agreed in 2012, the ‘Bridging the Gap’ target was set at 2,750 gigalitres. This was amended in 2018 to 2,075 gigalitres. As at 31 December 2022, the Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) estimated that a gap of 49.2 gigalitres of water remained in seven catchments to reach the ‘Bridging the Gap’ target.

4. The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) is the Australian Government entity responsible for recovering water to bridge the gap through: monitoring water recovery programs; funding, implementing and managing water infrastructure projects and efficiency measures; and undertaking purchases of water entitlements.

5. In March 2023, the department commenced an open tender process to purchase water entitlements to recover 44.3 gigalitres of water against the remaining gap of 49.2 gigalitres. The 4.9 gigalitres of surface water located in the ACT that also needed to be recovered to achieve the Bridging the Gap target was not included in the procurement process as water rights in the ACT are held and owned by a government entity. Separate arrangements were established with the ACT Government to bridge the gap in the territory.

6. The procurement process was finalised in January 2024. As at 17 January 2025, approximately 21.62 gigalitres of water has been recovered, fully bridging the gap in two of the six target catchments, with a gap of approximately 23.07 gigalitres remaining in the other four catchments.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. This audit examined the effectiveness of the department’s strategic procurement of water entitlements to meet the Bridging the Gap target under the Basin Plan. It followed on from Auditor-General Report No. 2 2020–21 Procurement of Strategic Water Entitlements to provide assurance to Parliament over the arrangements in place to support the procurement process, and the conduct of the procurement process to achieve value for money.

8. Water recovery is a topic of parliamentary and public interest. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) identified the audit as a priority of the Parliament for 2023–24.

Audit objective and criteria

9. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s strategic procurement of water entitlements to meet the Bridging the Gap target under the Basin Plan.

10. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Did the department establish appropriate arrangements to support strategic water procurement?

- Did the department conduct an effective procurement process to achieve value for money?

11. The audit focused on the 2023 Bridging the Gap procurement process, including arrangements to support the procurement and whether value for money was achieved. It also examined whether the recommendations from Auditor-General Report No. 2 2020–21 and the JCPAA Report 492 were implemented.

12. The audit did not examine: water recovery initiatives for targets other than the 2,075 GL/y Bridging the Gap target; compliance with water trading rules in the Basin Plan; activities of related bodies such as the MDBA or state water regulatory authorities; or the socioeconomic impacts of water recovery on local communities, except to the extent considered by the department as part of the procurement process.

Conclusion

13. The department’s strategic procurement of water entitlements to meet the Bridging the Gap target under the Murray–Darling Basin Plan was largely effective. While the department conducted an effective procurement process and demonstrated how it assessed value for money in accordance with its value for money framework, it was not able to meet the intended policy objective of fully bridging the gap through the procurement process. The current evaluation framework requires revision to enable an accurate measurement of the program’s impact on intended policy objectives, including in the context of broader evaluation activities planned for the Basin Plan. Further improvements are being made for subsequent tender processes to incorporate lessons learned, increase efficiency, and ensure better management of probity risks.

14. The department has established largely appropriate arrangements to support strategic water procurement. There are appropriate procurement frameworks in place, including a Strategic Water Purchasing Framework developed specifically for the water purchasing program outlining the scope of the program and the investment principles that would underpin water purchasing. The department has established appropriate oversight mechanisms to oversee the program and is managing program and procurement risks. An evaluation framework to monitor, report on and evaluate the strategic water purchasing program has been established. The evaluation framework does not enable an accurate measurement of the program’s impact on intended policy objectives, and requires revision to ensure that outcomes are appropriately defined, including in the context of other evaluation activities planned for the Basin Plan.

15. The department established a value for money framework for the procurement, specifying the key factors that would inform its purchasing decisions. The department documented and demonstrated how it assessed value for money in each of the six SDL resource units in accordance with its value for money framework. The procurement was compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), except in relation to minor errors in reporting contracts on AusTender. Negotiations were undertaken to maximise value for money outcomes, and revised value for money assessments were undertaken where negotiated prices differed from the delegate’s original approved figure. Relevant information and clear recommendations were provided to the delegate to enable them to make an informed procurement decision. The department provided sound advice to the minister on options to bridge the gap in the ACT and in SDL resource units with remaining gaps to bridge.

Supporting findings

Arrangements to support procurement

16. The department has established a procurement framework that aligns with the PGPA Act and the CPRs. This framework includes Accountable Authority Instructions providing guidance on the duties of officials when conducting a procurement, and departmental policies and guidance on key aspects of procurement. The department developed a Strategic Water Purchasing Framework specific to the water purchasing program, outlining the scope of the program and the investment principles that would underpin water purchasing. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.14)

17. The department has established appropriate oversight mechanisms for the water purchasing program, with clearly documented roles and responsibilities. The department is managing risks to the program and there is an appropriate level of oversight over program and procurement risks. (See paragraphs 2.15 to 2.52)

18. The department has established an evaluation framework to monitor, report on and evaluate the strategic water purchasing program. The evaluation framework is focussed on short- and medium-term program outputs and does not enable an accurate measurement of the program’s impact on intended policy objectives or link the program to evaluation activities planned for the Basin Plan. Monitoring and reporting arrangements have been established, and process improvements are being made following a lessons learned review of the 2023 Bridging the Gap procurement process. (See paragraphs 2.53 to 2.85)

Procurement process and value for money

19. The procurement process was compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), except in relation to minor errors in reporting contracts on AusTender. The department complied with the requirements relating to procurement planning and approach to market, and the tender evaluation process was conducted in accordance with the tender evaluation plan. Management of conflicts of interest was impacted by deficiencies in the declaration process. Manual tender screening and assessment processes resulted in some process inefficiencies and errors that were later discovered and corrected. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.46)

20. The department established a value for money framework for the strategic water purchasing program, specifying the relevant financial and non-financial factors it would consider in assessing value for money. The Tender Evaluation Panel’s value for money assessments were conducted in accordance with the approved value for money framework, and its discussions and recommendations were clearly documented in the tender evaluation reports and briefs to the delegate. Of 57 tenders approved for negotiation, the department negotiated reduced prices for 33 tenders. Revised value for money assessments were undertaken where negotiated prices differed from the delegate’s original approved figure. All tenders that were accepted or counteroffered were those recommended to the delegate as representing value for money. (See paragraphs 3.47 to 3.82)

21. The advice provided to the delegate contained relevant information to enable them to make an informed procurement decision. The department provided sound advice to the minister on options to bridge the gap in the ACT, including on whether the ACT’s proposal would contribute to bridging the gap and achieve value for money, and on strategies to bridge the remaining gap following the conclusion of 2023 Bridging the Gap procurement process. (See paragraphs 3.83 to 3.107)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.71

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water:

- review and update the evaluation framework for the strategic water purchasing program to ensure the chosen evaluation approach remains appropriate for the program; and

- if relevant, revise the outcomes in the evaluation framework to enable an accurate measurement of the impact of the strategic water purchasing program on intended policy objectives.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.28

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water update its procurement-related policies and guidance to provide clarity on establishing appropriate probity requirements, including on:

- determining who is required to complete probity forms and declarations;

- maintaining a complete and accurate record of individuals who have completed the relevant forms; and

- clearly documenting any conflicts that were declared and how they are being managed, to ensure the delegate has clear oversight of probity risks.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

22. The proposed audit report was provided to the department. The department’s summary response to the audit is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) welcomes the ANAO’s audit report on the Strategic Water Purchasing – Bridging the Gap 2023 procurement. The department appreciates ANAO’s recognition that administration of the Strategic Water Purchasing program for the 2023 procurement process was largely effective, with appropriate procurement frameworks and oversight mechanisms in place to support an effective procurement process, undertaken in accordance with the value for money framework.

The department agrees with the ANAO’s two recommendations identified in the audit report. Implementation of the recommendations has already commenced. The department is committed to providing meaningful evaluation of the program outcomes and has commenced a review of the evaluation framework. The department has also implemented strengthened arrangements to improve the oversight of conflict-of-interest requirements for its water purchasing programs.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

23. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Performance and impact measurement

Executive summary

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) publishes an annual audit work program (AAWP) which reflects the audit strategy and deliverables for the forward year. The purpose of the AAWP is to inform the Parliament, the public, and government sector entities of the planned audit coverage for the Australian Government sector by way of financial statements audits, performance audits, performance statements audits and other assurance activities. As set out in the AAWP, the ANAO prepares two reports annually that, drawing on information collected during financial statements audits, provide insights at a point in time of financial statements risks, governance arrangements and internal control frameworks of Commonwealth entities. These reports provide Parliament with an independent examination of the financial accounting and reporting of public sector entities.

These reports explain how entities’ internal control frameworks are critical to executing an efficient and effective audit and underpin an entity’s capacity to transparently discharge its duties and obligations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). Deficiencies identified during audits that pose either a significant or moderate risk to an entity’s ability to prepare financial statements free from material misstatement are reported.

This report presents the final results of the 2023–24 audits of the Australian Government’s Consolidated Financial Statements (CFS) and 245 Australian Government entities. The Auditor-General Report No. 42 2023–24 Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities, focused on the interim results of the audits of 27 of these entities.

Consolidated financial statements

Audit results

1. The CFS presents the whole of government and the General Government Sector financial statements. The 2023–24 CFS were signed by the Minister for Finance on 28 November 2024 and an unmodified auditor’s report was issued on 2 December 2024.

2. There were no significant or moderate audit issues identified in the audit of the CFS in 2023–24 or 2022–23.

Australian Government financial position

3. The Australian Government reported a net operating balance of a surplus of $10.0 billion ($24.9 billion surplus in 2022–23). The Australian Government’s net worth deficiency decreased from $570.3 billion in 2022–23 to $567.5 billion in 2023–24 (see paragraphs 1.8 to 1.26).

Financial audit results and other matters

Quality and timeliness of financial statements preparation

4. The ANAO issued 240 unmodified auditor’s reports as at 9 December 2024. The financial statements were finalised and auditor’s reports issued for 79 per cent (2022–23: 91 per cent) of entities within three months of financial year-end. The decrease in timeliness of auditor’s reports reflects an increase in the number of audit findings and legislative breaches identified by the ANAO, as well as limitations on the available resources within the ANAO in order to undertake additional audit procedures in response to these findings

5. A quality financial statements preparation process will reduce the risk of inaccurate or unreliable reporting. Seventy-one per cent of entities delivered financial statements in line with an agreed timetable (2022–23: 72 per cent). The total number of adjusted and unadjusted audit differences decreased during 2023–24, although 38 per cent of audit differences remained unadjusted. The quantity and value of adjusted and unadjusted audit differences indicate there remains an opportunity for entities to improve quality assurance over financial statements preparation processes (see paragraphs 2.138 to 2.154).

Timeliness of financial reporting

6. Annual reports that are not tabled in a timely manner before budget supplementary estimates hearings decrease the opportunity for the Senate to scrutinise an entity’s performance. Timeliness of tabling of entity annual reports improved. Ninety-three per cent (2022–23: 66 per cent) of entities that are required to table an annual report in Parliament tabled prior to the date that the portfolio’s supplementary budget estimates hearing commenced. Supplementary estimates hearings were held one week later in 2023–24 than in 2022–23. Fifty-seven per cent of entities tabled annual reports one week or more before the hearing (2022–23: 12 per cent). Of the entities required to table an annual report, 4 per cent (2022–23: 6 per cent) had not tabled an annual report as at 9 December 2024 (see paragraphs 2.155 to 2.166).

Official hospitality

7. Eighty-one per cent of entities permit the provision of hospitality and the majority have policies, procedures or guidance in place. Expenditure on the provision of hospitality for the period 2020–21 to 2023–24 was $70.0 million. Official hospitality involves the provision of public resources to persons other than officials of an entity to achieve the entity’s objectives. Entities that provide official hospitality should have policies, and guidance in place which clearly set expectations for officials. There are no mandatory requirements for entities in managing the provision of hospitality, however, the Department of Finance (Finance) does provide some guidance to entities in model accountable authority instructions. Of those entities that permit hospitality 83 per cent have established formal policies, guidelines or processes.

8. Entities with higher levels of exposure to the provision of official hospitality could give further consideration to implementing or enhancing compliance and reporting arrangements. Seventy-four per cent of entities included compliance requirements in their policies, procedures or guidance which support entity’s obtaining assurance over the conduct of official hospitality. Compliance processes included acquittals, formal reporting, attestations from officials and/or periodic internal audits. Thirty-one per cent of entities had established formal reporting on provision of official hospitality within their entities (see paragraphs 2.36 to 2.56).

Artificial intelligence

9. Fifty-six entities used artificial intelligence (AI) in their operations during 2023–24 (2022–23: 27 entities). Most of these entities had adopted AI for research and development activities, IT systems administration and data and reporting.

10. During 2023–24, 64 per cent of entities that used AI had also established internal policies governing the use of AI (2022–23: 44 per cent). Twenty-seven per cent of entities had established internal policies regarding assurance over AI use. An absence of governance frameworks for managing the use of emerging technologies could increase the risk of unintended consequences. In September 2024, the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) released the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government, which establishes requirements for accountability and transparency on the use of AI within entities (see paragraphs 2.67 to 2.71).

Cloud computing

11. Assurance over effectiveness of cloud computing arrangements (CCA) could be improved. During 2023–24, 89 per cent of entities used CCAs as part of the delivery model for the IT environment, primarily software-as-a-service (SaaS) arrangements. A Service Organisation Controls (SOC) certificate provides assurance over the implementation, design and operating effectiveness of controls included in contracts, including security, privacy, process integrity and availability. Eighty-two per cent of entities did not have in place a formal policy or procedure which would require the formal review and consideration of a SOC certificate.

12. In the absence of a formal process for obtaining and reviewing SOC certificates, there is a risk that deficiencies in controls at a service provider are not identified, mitigated or addressed in a timely manner (see paragraphs 2.57 to 2.66).

Audit committee member rotation

13. Audit committee member rotation considerations could be enhanced. The rotation of audit committee membership is not mandated, though guidance to the sector indicates that rotation of members allows for a flow of new skills and talent through committees, supporting objectivity. Forty-six per cent of entities did not have a policy requirement for audit committee member rotation.

14. Entities could enhance the effectiveness of their audit committees by adopting a formal process for rotation of audit committee membership, which balances the need for continuity and objectivity of membership (see paragraphs 2.16 to 2.21).

Fraud framework requirements

15. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 encourages entities to conduct fraud risk assessments at least every two years and entities responsible for activities with a high fraud risk may assess risk more frequently. All entities had in place a fraud control plan. Ninety-seven per cent of entities had conducted a fraud risk assessment within the last two years. Changes to the framework which occurred on 1 July 2024 requires entities to expand plans to take account of preventing, detecting and dealing with corruption, as well as periodically examining the effectiveness of internal controls (see paragraphs 2.16 to 2.21).

Summary of audit findings

16. Internal controls largely supported the preparation of financial statements free from material misstatement. However, the number of audit findings identified by the ANAO has increased from 2023–24. A total of 214 audit findings and legislative breaches were reported to entities as a result of the 2023–24 financial statements audits. These comprised six significant, 46 moderate, 147 minor audit findings and 15 legislative breaches. The highest number of findings are in the categories of:

- IT control environment, including security, change management and user access;

- compliance and quality assurance frameworks, including legal conformance; and

- accounting and control of non-financial assets.

17. IT controls remain a key issue. Forty-three per cent of all audit findings identified by the ANAO related to the IT control environment, particularly IT security. Weaknesses in controls in this area can expose entities to an increased risk of unauthorised access to systems and data, or data leakage. The number of IT findings identified by the ANAO indicate that there remains room for improvement across the sector to enhance governance processes supporting the design, implementation and operating effectiveness of controls.

18. These audits findings included four significant legislative breaches, one of which was first identified since 2012–13. The majority (53 per cent) of other legislative breaches relate to incorrect payments of remuneration to key management personnel and/or non-compliance with determinations made by the Remuneration Tribunal. Entities could take further steps to enhance governance supporting remuneration to prevent non-compliance or incorrect payments from occurring (see paragraphs 2.72 to 2.137).

Financial sustainability

19. An assessment of an entity’s financial sustainability can provide an indication of financial management issues or signal a risk that the entity will require additional or refocused funding. The ANAO’s analysis concluded that the financial sustainability of the majority of entities was not at risk (see paragraphs 2.167 to 2.196).

Reporting and auditing frameworks

Changes to the Australian public sector reporting framework

20. The development of a climate-related reporting framework and assurance regime in Australia continues to progress. ANAO consultation with Finance to establish an assurance and verification regime for the Commonwealth Climate Disclosure (CCD) reform is ongoing (see paragraphs 3.20 to 3.24).

21. Emerging technologies (including AI) present opportunities for innovation and efficiency in operations by entities. However, rapid developments and associated risks highlight the need for Accountable Authorities to implement effective governance arrangements when adopting these technologies. The ANAO is incorporating consideration of risks relating to the use of emerging technologies, including AI, into audit planning processes to provide Parliament with assurance regarding the use of AI by the Australian Government (see paragraphs 3.25 to 3.33).

22. The ANAO Audit Quality Report 2023–24 was published on 1 November 2024. The report demonstrates the evaluation of the design, implementation and operating effectiveness of the ANAO’s Quality Management Framework and achievement of ANAO quality objectives (see paragraphs 3.34 to 3.39).

23. The ANAO Integrity Report 2023–24 and the ANAO Integrity Framework 2024–25 were also published on 1 November 2024 to provide transparency of the measures undertaken to maintain a high integrity culture within the ANAO (see paragraphs 3.44 to 3.46).

Cost of this report

24. The cost to the ANAO of producing this report is approximately $445,000.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Bureau of Meteorology (the Bureau) is responsible for providing weather, water, climate, and ocean services for Australia. The Bureau’s weather forecasts, warnings, and analyses support decision-making by governments, industry, and the community. Australian sectors that are supported by timely and accurate weather services include emergency management, agriculture, aviation, land and marine transport, energy and resources operations, climate policy, water management, defence and foreign affairs.1

2. The Bureau is established by the Meteorology Act 1955 (Meteorology Act). Since 2002, it is an Executive Agency under the Public Service Act 1999. The Director of Meteorology has the powers and responsibilities of an accountable authority under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The Bureau’s accountable authority reports to the minister or ministers responsible for administering the Meteorology Act and the Water Act 2007 (Water Act). Since June 2022, the Director of Meteorology has reported to the Minister for the Environment and Water.

3. The Meteorology Act and the Water Act define the Bureau’s functions and the powers of the Director of Meteorology. Broadly, these are to:

- take and record meteorological observations and supply information such as forecasts, warnings, and advice on meteorological matters2; and

- collect, hold, manage, interpret, and disseminate Australia’s water information.3

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The Bureau manages more than $1.3 billion in non-financial assets. The Bureau estimates that observing network assets including observing network instruments and other items and systems that support the instruments’ proper functioning make up approximately 28 per cent of the Bureau’s total asset base.

5. Effective management of assets in the observing network is fundamental to the Bureau’s ability to provide services to the community. Meteorological instruments are highly specialised, geographically dispersed, and can require significant levels of investment to purchase, maintain, and repair to effectively support weather and climate forecasting, warnings, and research.

6. The audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament over the Bureau’s management of assets in its observing network.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Bureau of Meteorology is effectively managing assets in its observing network.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Does the Bureau of Meteorology have effective frameworks and systems governing assets in its observing network?

- Does the Bureau of Meteorology have appropriate arrangements to manage the lifecycle of assets in its observing network?

- Does the Bureau of Meteorology effectively monitor, measure, and report on its management of assets in its observing network?

9. This audit focused on the Bureau’s assets in its observing network including operational maintenance practices and records, and relevant plans, policies, and frameworks for managing assets that take observations. The ANAO reviewed the Bureau’s activities from 2018 to October 2024.

10. This audit did not assess:

- the accuracy or security of the measurements taken by the Bureau’s observing network meteorological instruments;

- the quality or accuracy of the Bureau’s forecasting in the delivery of general and extreme weather services, including the ‘downstream’ processing of data and the models used to develop and inform forecasting;

- the quality or accuracy of the Bureau’s maintenance of the climate record;

- supporting infrastructure systems and items, such as air-conditioners, fencing, and small buildings;

- the procurement of observing network assets where the procurement represented expenditure other than operational maintenance; or

- the Bureau’s provision of services to the Department of Defence and related stakeholders for civil defence exercises and operations.

Conclusion

11. The Bureau is partly effective in managing assets in its observing network. The Bureau has been implementing an asset management framework and supporting elements since 2020 however the asset management framework is not fully implemented. While the Bureau has continued to deliver weather services, key areas for further improvement include reviewing asset management planning documents, establishing medium to long term financial planning arrangements to support long term strategic planning, and establishing and embedding more extensive monitoring and reporting arrangements.

12. The frameworks and systems governing the Bureau’s management of assets in its observing network are partly effective. Not all policies and plans have been completed, reviewed, and embedded as planned. The Bureau has not reviewed or updated the Strategic Asset Management Plan to reflect its current practices and does not have a financial forecast for asset intensive areas to enable long term strategic planning. Roles and responsibilities are clearly identified. The Bureau’s Enterprise Asset Management System is in place and largely being used as planned. Development of asset management processes and training pathways is not complete.

13. The Bureau’s arrangements to manage the lifecycle of assets in its observing network are partly appropriate. The Bureau’s asset management plans include lifecycle management activities and related cost estimates. The Bureau’s budget planning process for 2024–25 did not incorporate the predicted costs presented in the asset management plans. All types of maintenance are recorded in the Bureau’s Enterprise Asset Management System and triaged based on priority. The Bureau’s asset management plans include outcomes to report against, however target and actual performance levels are not complete. The Bureau’s guidance surrounding disposals is not complete. The Bureau’s Fixed Asset Register and Enterprise Asset Management System each record assets and disposals differently and the Bureau does not have guidance to ensure records are aligned.

14. The Bureau’s monitoring, measuring, and reporting on assets in its observing network is partly effective. Information on observing network asset data availability is being recorded in Bureau systems and reported to established governance bodies. The Bureau is not reporting against the achievement of sustainability funding commitments. Three of the Bureau’s newly developed observing network performance measures report whether risks have eventuated and two report whether risk controls are being implemented. Since November 2020, the Bureau has been reporting against out-of-tolerance risks relating to ‘unviable’ asset capabilities. Monitoring and reporting is not being undertaken to regularly review asset management maturity, as proposed in the Strategic Asset Management Plan.

Supporting findings

Governance and planning

15. The Bureau has developed an Enterprise Asset Management Policy and a Strategic Asset Management Plan. The Bureau has not reviewed or updated the Strategic Asset Management Plan in the required timeframes. The Enterprise Asset Financial Overview has not been implemented, and the Bureau does not have a financial forecast for ongoing and capital funding requirements for asset intensive areas to enable long term strategic planning. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.30)

16. The Bureau has established governance bodies that support asset management. The Bureau has established asset management roles identified as needed in the Strategic Asset Management Plan. Responsibility and accountability for asset lifecycle management is defined. Maintenance and operations responsibilities of each observing network sub-network are documented in asset management plans. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.45)

17. The Bureau’s procedures and systems to support the management of assets are incomplete. The Bureau’s Enterprise Asset Management System is in place and largely being used as originally planned. The Bureau does not have a plan to develop all asset management processes identified as necessary in 2022. Development is not complete for training and competency frameworks for three sub-networks and two asset classes. (See paragraphs 2.46 to 2.84)

Asset lifecycle

18. The Bureau’s asset management plans include a section on lifecycle strategies, which describes the types of activities to be undertaken within each sub-network across the lifecycle, and a five- or ten-year investment profile that includes cost estimates and key activities. The Bureau’s budget planning process for 2024–25 did not incorporate the predicted costs presented in the asset management plans. Planning for renewal and disposal is not complete for all asset management plans. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.37)

19. All types of maintenance are structured through work orders in the Bureau’s Enterprise Asset Management System. Maintenance tasks are assigned priorities and triaged in accordance with these. For each sub-network, between 52 per cent and 79 per cent of target preventative maintenance work orders were achieved in 2023–24. The outcomes to measure performance throughout the 11 sub-networks are not complete. (See paragraphs 3.38 to 3.69)

20. The Bureau has established policies and procedural guidance that acknowledge the necessity of disposal. This guidance is not complete as there is no guidance to support operational decision-making about when disposal is appropriate. The Bureau’s Fixed Asset Register and Enterprise Asset Management System each record assets and disposals differently. The Bureau does not have a process or guidance to ensure records are aligned between the two systems. (See paragraphs 3.70 to 3.83)

Monitoring and reporting

21. The Bureau’s performance measurement strategy measures the output of the observing network through information on observing network asset data availability. This supports reporting on the achievement of corporate outcomes identified in the Bureau Strategy 2022–2027 and Data and Digital Group Plan. The Bureau is not reporting against the achievement of sustainability funding commitments. Without a strategy for investment in asset maintenance and monitoring and reporting of the impacts of investment, the Bureau cannot know whether investment is effective. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.23)

22. The key performance indicator for observing network assets is data availability which is based on the risk of weather information not being available to stakeholders. Three of the Bureau’s newly developed observing network performance measures report whether risks have eventuated and two provide insight into whether risk controls are available and being implemented. Since November 2020, the Bureau has been reporting against out-of-tolerance risks relating to ‘unviable’ asset capabilities. The addition and completion of treatment plans and controls has not reduced the reported risk level. (See paragraphs 4.24 to 4.58)

23. The Bureau has identified corrective actions to take against assets or the asset management approach when observing network asset performance monitoring targets are not met. Monitoring and reporting is not being undertaken to regularly review asset management maturity, as proposed in the Strategic Asset Management Plan. The Bureau has not addressed the risks identified within internal audit recommendations. (See paragraphs 4.59 to 4.76)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.19

The Bureau of Meteorology:

- review and update the Enterprise Asset Management Plan and the Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMP) to reflect the Bureau’s asset management practices and approach; and

- measure and report on the progress of the implementation of asset management uplift initiatives outlined in the SAMP and its roadmap.

Bureau of Meteorology response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.56

The Bureau of Meteorology develop procedures for asset management lifecycle activities and complete its review of processes.

Bureau of Meteorology response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.83

The Bureau of Meteorology finalise training requirements and methods for all maintenance and repair activities across the observing network.

Bureau of Meteorology response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.68

The Bureau of Meteorology include management outcomes in asset management planning documentation by:

- agreeing on and including all selected targets in relevant documentation;

- collecting data on performance;

- calculating actual performance levels over time; and

- documenting the impact of asset management approaches on desired outcomes.

Bureau of Meteorology response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

24. The proposed audit report was provided to the Bureau. The Bureau’s summary response is reproduced below. The full response from the Bureau is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Thank you for providing the Australian National Audit Office’s report on the Bureau of Meteorology’s Management of Assets in its Observing Network.

The observing network, consisting of almost 15,000 individual assets, distributed across Australia and its territories, is one of the nation’s largest and most complex data gathering endeavours. The meteorological information gathered by the observing assets, 24 hours a day every day of the year, consists of observations of the atmosphere, space weather, terrestrial waterways and oceans.

Together, they form the information base which is vital for the provision of public weather services, the specialist needs of industry and national security, the integrity of the national climate record, and Australia’s contribution to international meteorological data and science.

I recognise the Bureau’s significant reforms and investment in the observing capabilities over the last decade, including improvements to logistics and maintenance practices through automation of manual observations and new observations maintenance hubs, the introduction of consistent asset management and technology competency and training frameworks, and the recent implementation of a new enterprise asset management system.

The Bureau agrees with the ANAO’s recommendations as further contributions to the maturity of its observing network asset management and operations, and commits to relevant actions.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

25. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program design

Performance and impact measurement

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In September 2022 the Australian Energy Regulator reported that over the course of 2022, the war in Ukraine resulted in price volatility and price hikes for energy on international markets.1 Due to the links between domestic and export markets this affected domestic customers and the wider economy. Simultaneously, domestic factors contributed to wholesale energy price increases.

2. The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) and the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) were lead entities in the development of policy options to seek to address energy price increases. On 9 December 2022, the Prime Minister, the Treasurer, and the Minister for Climate Change and Energy announced the Energy Price Relief Plan (the plan) — a package of measures designed to ‘shield Australian families and businesses from the worst impacts of predicted energy price spikes.’

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The budget for the package of measures under the Energy Price Relief Plan was estimated between $3 billion and $3.5 billion over five years. The government sought urgent advice on options to seek to address energy price increases.

4. The audit provides assurance to Parliament on whether the Energy Price Relief Plan was effectively designed and the effectiveness of planned frameworks for implementation and evaluation.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design process for the Energy Price Relief Plan.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Was the development of the plan informed by sound policy advice?

- Was implementation effectively planned?

- Are the arrangements to assess the achievement of outcomes of the plan effective?

7. The audit did not assess:

- the design or implementation of the Capacity Investment Scheme which was also included in the 9 December 2022 announcement;

- the design of the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism reforms agreed to by government in September 2022; or

- the implementation of the extension of the energy bill rebates announced in May 2024.

Conclusion

8. The design process for the Energy Price Relief Plan was largely effective. The design process could have been improved with earlier engagement with delivery agencies. The Energy Price Relief Plan would benefit from a plan to assess the achievement of outcomes.

9. The development of the Energy Price Relief Plan was informed by sound policy advice. Roles and responsibilities, relevant guidance and risk management processes were in place to support the development of the Energy Price Relief Plan. Benefits of policy options were assessed and were supported by evidence. During the design process industry stakeholders were consulted on the gas market interventions. Stakeholders within the APS were consulted in the development of policy options, except for: Services Australia; the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (DITRDCA); and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). Earlier engagement with APS delivery agencies would have improved the consideration of implementation within the policy advice provided to government. Treasury and DCCEEW did not document risks associated with rapid policy development and risk mitigation strategies. Activities that can assist in reducing risks were undertaken, including seeking expert advice, engaging industry stakeholders, and establishing fit-for-purpose governance and coordination arrangements.

10. Arrangements established to support implementation of the Energy Price Relief Plan were largely effective. Policy advice to government identified risks for all measures. Risks related to the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism reforms were considered when the reforms were initially developed in 2022, however risks specific to bringing forward the commencement of the reforms were not incorporated with other risks included in policy advice. Treasury and DCCEEW monitored risks for three of the five measures — targeted electricity bill rebate, mandatory gas code of conduct, and coal price cap. The department responsible for the implementation of the targeted electricity bill rebate was not identified in policy advice provided to government in December 2022 and was not confirmed by government until August 2023. Treasury had not established a risk assessment and an implementation plan for the targeted electricity bill rebate and the gas price cap. Treasury’s progress reports to government on the targeted electricity bill relief included elements of implementation planning.

11. Arrangements to assess the achievement of outcomes for the Energy Price Relief Plan were largely effective. While activities to assess the achievement of outcomes for individual measures have been planned or undertaken, plans to assess the collective impacts of the five measures under the Energy Price Relief Plan were not established. Monitoring arrangements have been established for four of five measures and implemented — the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism has not been activated. Treasury and DCCEEW have produced reporting on the collective impacts of select measures. DCCEEW has conducted a review of the coal price cap. Planning has commenced for reviews of the targeted electricity bill rebate, mandatory gas code of conduct and Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism.

Supporting findings

Development of the plan

12. Roles and responsibilities were defined for the development of policy options. Treasury and DCCEEW have largely relevant guidance on developing policy advice available for staff. The departments did not document risks, and associated mitigation strategies, related to policy development. Activities that may reduce risks were undertaken: Treasury and DCCEEW sought expert advice; the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) engaged with select industry stakeholders; and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) established fit-for-purpose governance and coordination arrangements. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.19)

13. During the development of policy advice, APS stakeholders — except for Services Australia, DITRDCA and DVA — were engaged in the design of all measures. Select industry stakeholders were engaged on the gas market interventions prior to policy advice being provided to government. (See paragraphs 2.20 to 2.81)

14. Market modelling and data and advice from relevant government entities was used to support advice to government on policy options. Potential impacts of the proposed policy options included in policy advice were supported by evidence. Treasury and DCCEEW’s impact analysis included an assessment of regulatory burden costs and benefits for three measures — gas price cap, mandatory gas code of conduct and bringing forward the commencement of the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism reforms. While DCCEEW had undertaken a preliminary assessment, an impact analysis was not undertaken for the remaining two measures — targeted electricity bill rebate and coal price cap. (See paragraphs 2.82 to 2.94)

Planning for implementation

15. Advice to government identified risks for four of the five measures. Risks related to the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism reforms were considered as part of an earlier impact assessment process and specific risks related to bringing forward the commencement of the reforms were not highlighted in policy advice. Advice did not document the risk that payments may be made to ineligible recipients under the targeted electricity bill rebate measure. DCCEEW undertook risk assessments for two of the five measures — the mandatory gas code of conduct and the coal price cap. Risks were monitored for three of the four measures led by Treasury and DCCEEW — the targeted electricity bill rebate, mandatory gas code of conduct, and coal price cap. Risk reporting was undertaken by Treasury for the targeted electricity bill rebate and by DCCEEW for the mandatory gas code of conduct. Risks related to the gas price cap and coal price cap measures were not reported. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.16)

16. Advice to government included information on implementation of all five measures under the plan. Policy advice on the targeted electricity bill rebate and the coal price cap measures did not identify which department would be responsible for implementation. Implementation plans were established for three measures — mandatory gas code of conduct, coal price cap and bringing forward the commencement of the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism reforms. Implementation planning activities were undertaken for the remaining two measures. For the targeted electricity bill rebate, Treasury had not established an implementation plan. Elements of implementation planning were included within progress reports provided to government. Implementation planning was discussed in governance meetings co-chaired by Treasury and Services Australia. (See paragraphs 3.17 to 3.38)

Monitoring and assessing the achievement of outcomes

17. Subsequent to the announcement of the Energy Price Relief Plan in December 2022, oversight and monitoring frameworks have been established and implemented for four of five measures — the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism has not been activated and therefore monitoring arrangements have not been implemented. Monitoring activities are being undertaken in accordance with the frameworks which have been established. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.29)

18. Treasury and DCCEEW outlined the objectives and estimated impacts of the Energy Price Relief Plan. Plans to assess the collective impacts of the five measures under the plan were not established. Entities have developed plans to assess the achievement of outcomes for the individual measures, except for the gas price cap. Treasury and DCCEEW have reported collective impacts of the Energy Price Relief Plan and DCCEEW has conducted a review of the New South Wales coal price cap. Statutory reviews of the mandatory gas code of conduct and the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism reforms are due to be undertaken during 2025. (See paragraphs 4.30 to 4.70)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.16

The Department of the Treasury develop risk management guidance for staff where Treasury is the lead agency for a policy, including for managing risks identified in policy advice.

Department of the Treasury response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

19. The proposed report was provided to the Department of the Treasury and the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Extracts of the proposed report were provided to the ACCC, AER, DVA, Services Australia, DITRDCA, DISR, and PM&C.

20. Treasury, DCCEEW, the AER and DISR provided summary responses and these are below. Full responses from these entities are included at Appendix 1.

Department of the Treasury

Treasury welcomes the report, in particular the reflection that the policy was based on sound advice and that both policy and implementation development were largely effective to achieve the desired policy outcomes. Treasury also welcomes the report’s key messages, especially regarding the need to adapt risk appetite to short timeframes and urgent delivery. This aligns with Treasury’s risk management policy, noting our higher appetite for risk in these circumstances while still balancing potential consequences.

Treasury agrees with the recommendation presented in the report. Treasury accepts the ANAO’s evidence regarding the risk assessments and implementation planning during the development of the Energy Price Relief Plan. Treasury considers the recommendation recognises the ANAO’s findings and Treasury acknowledges it could develop guidance on how the risk management framework should be applied in situations where timeframes are short and delivery is urgent.

Treasury has engaged an external review of the implementation of the first round of the Energy Bill Relief Fund and will leverage findings from this review in drafting further risk management guidance.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) welcomes the ANAO report and the conclusion that the design process for the Energy Price Relief Plan was largely effective, with no recommendations made for the department.

The Government’s Energy Price Relief Plan was a package of measures developed to shield Australian families and businesses from the worst impacts of predicted energy price spikes. This rapid policy development occurred within complex electricity and gas markets and required engagement across multiple agencies and other parties during its development and implementation.

The ANAO’s observations including areas of improvement applicable in the unique setting of rapid policy development are valuable insights that will inform and influence the department’s continual improvement practices in stakeholder engagement and program governance.

Australian Energy Regulator

The AER was provided with extracts from the proposed report.

The AER notes that there are no findings or recommendations relating to the AER.

The AER notes the contents of the report, including the key messages. The key messages reflect the experience and approach of the AER.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources

The Department of Industry, Science, and Resources (the department) acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office’s proposed audit report on the Design of the Energy Price Relief Plan.

The department acknowledges the report’s key findings on policy design, governance and risk management. The department strives to achieve meaningful stakeholder engagement to ensure feedback is accounted for in policy design. In the design and implementation of the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism (ADGSM) reforms, two public consultation processes were conducted – on the design of policy and on the draft guidelines – to inform the development of effective policy that contributes to the delivery of positive outcomes for our stakeholders.

The department is committed to establishing and improving robust governance and risk management practices, and notes these principles are particularly important when designing and implementing policy initiatives in constrained timeframes.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

21. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy design

Governance and risk management

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act) requires that Australian Public Service (APS) employees, agency heads and statutory office holders abide by the APS Code of Conduct.1 The APS Code of Conduct, consistent with duties under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), require officials to declare the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality. Collectively, these requirements establish obligations for officials and Commonwealth entities in relation to how they manage the provision and receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality.

2. Section 27 of the PGPA Act states that an official must not improperly use their position to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit for themselves or another person, or to cause, or seek to cause, detriment to the entity, the Commonwealth, or any other person.2 The National Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 also contains provisions against conduct that adversely affects (or could adversely affect) the honest and impartial exercise of any public official’s powers, functions or duties.3

3. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) publishes Guidance for Agency Heads – Gifts and Benefits. The principles underpinning this guidance are that:

- agency heads are meeting public expectations of integrity, accountability, independence, transparency and professionalism in relation to gifts and benefits; and

- there is consistency in relation to agency heads’ management of gifts and benefits across APS agencies and Commonwealth entities and companies.4

4. The Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) is a corporate Commonwealth entity established under the Water Act 2007 (the Water Act) and comprises:

- an eight-member Authority (the Authority) with functions and responsibilities defined under the Water Act and conditions set by the Remuneration Tribunal5; and

- a statutory agency of staff engaged under the Public Service Act, with an average staffing level of 367 for 2024–25.6

5. The MDBA is responsible for coordinating how water resources are managed in the Murray–Darling Basin.7

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. Section 27 of the PGPA Act states that an official must not improperly use their position to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit for themselves or another person, or to cause, or seek to cause, detriment to the entity, the Commonwealth, or any other person. Public service entities must meet public expectations of integrity, accountability, independence, transparency, and professionalism. Acceptance of a gift or benefit that relates to an official’s employment can create a real or apparent conflict of interest that should be avoided.8

7. Public confidence in Commonwealth entities and the APS can be damaged when gifts and benefits that create a conflict of interest are accepted or not properly declared. The APSC states in its publication, APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice, that the risk of the appearance of a conflict can damaging to public confidence:

The appearance of a conflict can be just as damaging to public confidence in public administration as a conflict which gives rise to a concern based on objective facts.9

8. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to the Parliament that the MDBA has complied with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements.

Audit objective and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the MDBA had complied with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements.

10. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following two high-level audit criteria.

- Did the MDBA have effective arrangements in place to manage gifts, benefits and hospitality?

- Were the MDBA’s controls and processes for gifts, benefits and hospitality operating effectively in accordance with its policies and procedures?

11. The audit examined the management of gifts, benefits and hospitality within the MDBA over the period 1 July 2021 to 31 March 2024.

Conclusion

12. The MDBA has been partly effective in complying with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements. While the MDBA has policies and procedures for managing gifts, benefits and hospitality, the implementation of its controls and processes for ensuring compliance with gift, benefit and hospitality requirements have not been effectively operationalised.

13. The MDBA has established largely effective arrangements for managing gifts, benefits and hospitality. The MDBA has not considered conflict of interest risks associated with gifts, benefits and hospitality within its risk management framework. While the MDBA has developed policies and procedures for the acceptance and provision of gifts, benefits and hospitality, there are opportunities to improve the consistency between policies and procedures. Whole of government training on integrity and fraud and corruption is mandatory for MDBA staff. Limited guidance is provided to Authority members. The MDBA maintains an internal register of gifts and benefits accepted by MDBA officials, and has published a register of gifts and benefits received by the Chief Executive.

14. The MDBA’s controls and processes are partly effective in supporting its compliance with gift, benefit and hospitality requirements. Deficiencies were identified with preventative controls relating to reporting on mandatory training completion and the compliance with policy and procedural requirements for the acceptance and provision of gifts, benefits and hospitality. While the MDBA does not have specific detective controls relating to acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality, since 2022–23 it has included a question on provision of hospitality in its biannual financial compliance survey. The MDBA has not established processes for managing non-compliance or assurance activities for gifts, benefits and hospitality.

Supporting findings

Arrangements for managing gifts, benefits and hospitality

15. The MDBA has articulated risks and controls related to bribery and corruption in a 2024 fraud and corruption risk assessment. Existing controls related to acceptance or provision of gifts, benefits and hospitality were not referenced in the 2024 assessment. Two integrity-related risks were identified in the MDBA’s November 2021 Enterprise Risk Management Plan. The MDBA developed a revised suite of enterprise risks in August 2023, which no longer includes integrity-related risks. (See paragraphs 2.6 to 2.21)