Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Take our Insights reader feedback survey

Help shape the future of ANAO Insights by taking our reader feedback survey.

Management of Corporate Credit Cards

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The aim of Audit Lessons is to communicate themes from our audit work to make it easier for people working within the Australian public sector to apply the lessons.

Audit Lessons — Management of Corporate Credit Cards is intended for officials working in financial management or governance roles with responsibility for the management of corporate credit cards.

Introduction

Australian Government entities use corporate credit cards to support timely and efficient payments to suppliers of goods and services. Corporate credit cards include charge cards (such as Visa, Mastercard, Diners Club and American Express cards) and vendor cards (such as travel and fuel cards). Credit vouchers (such as Cabcharge cards) are also used.

The misuse of corporate credit cards, whether deliberate or accidental, can result in financial loss and reputational damage to government entities and the Australian Public Service (APS). Deliberate misuse of a corporate credit card is fraud.

Australian Government framework for using corporate credit cards

The Commonwealth Resource Management Framework governs how Australian Government entities use and manage public resources. The cornerstone of the framework is the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). Under section 56 of the PGPA Act, the Minister for Finance has delegated the power to enter into a limited range of borrowing agreements to the accountable authoritiesof non-corporate Commonwealth entities.This includes the power to enter into an agreement for the issue and use of credit cards, providing money borrowed is repaid within 90 days.

The PGPA Act sets out general duties of accountable authorities and officials of Australian Government entities. Relevant to credit card use, officials have a duty not to improperly use their positions to gain or seek to gain a benefit or advantage for themselves or others, or to cause detriment to the Commonwealth, entity, or others.Further, the duties of an accountable authority include:

- governing an entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources; and

- establishing and maintaining appropriate systems of risk oversight and management and internal control, including measures to ensure that officials comply with the finance law.

Under subsection 20A(1) of the PGPA Act, an accountable authority may give instructions (referred to as accountable authority instructions) to entity officials about any matter relating to the finance law. The Department of Finance has published model accountable authority instructions, which include model instructions for the use of credit cards (see Box 1) as well as suggestions for additional instructions on credit card use.

Box 1: Model accountable authority instructions for credit card use — non-corporate Commonwealth entity

- Only the person issued a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, or someone specifically authorised by that person, may use that credit card, credit card number or credit voucher.

- You may only use a Commonwealth credit card or card number to obtain cash, goods or services for the Commonwealth entity based on the proper use of public resources.

- You cannot use a Commonwealth credit card or card number for private expenditure.

- In deciding whether to use a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must consider whether it would be the most cost-effective payment option in the circumstances.

- Before using a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must ensure that the requirements in the instructions ‘Procurement, grants and other commitments and arrangements’ [a separate section of the model accountable authority instructions] have been met before entering into the arrangement.

- You must: ensure that your use of a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher is consistent with any approval given, including any conditions of the approval; and ensure that any Commonwealth credit cards and credit vouchers issued to you are stored safely and securely.

Source: ANAO summary of information from the Department of Finance’s Accountable Authority Instructions (RMG 206).

The PGPA Act and model accountable authority instructions also include other content relevant to credit card use, particularly on spending public money, official hospitality, and official travel.

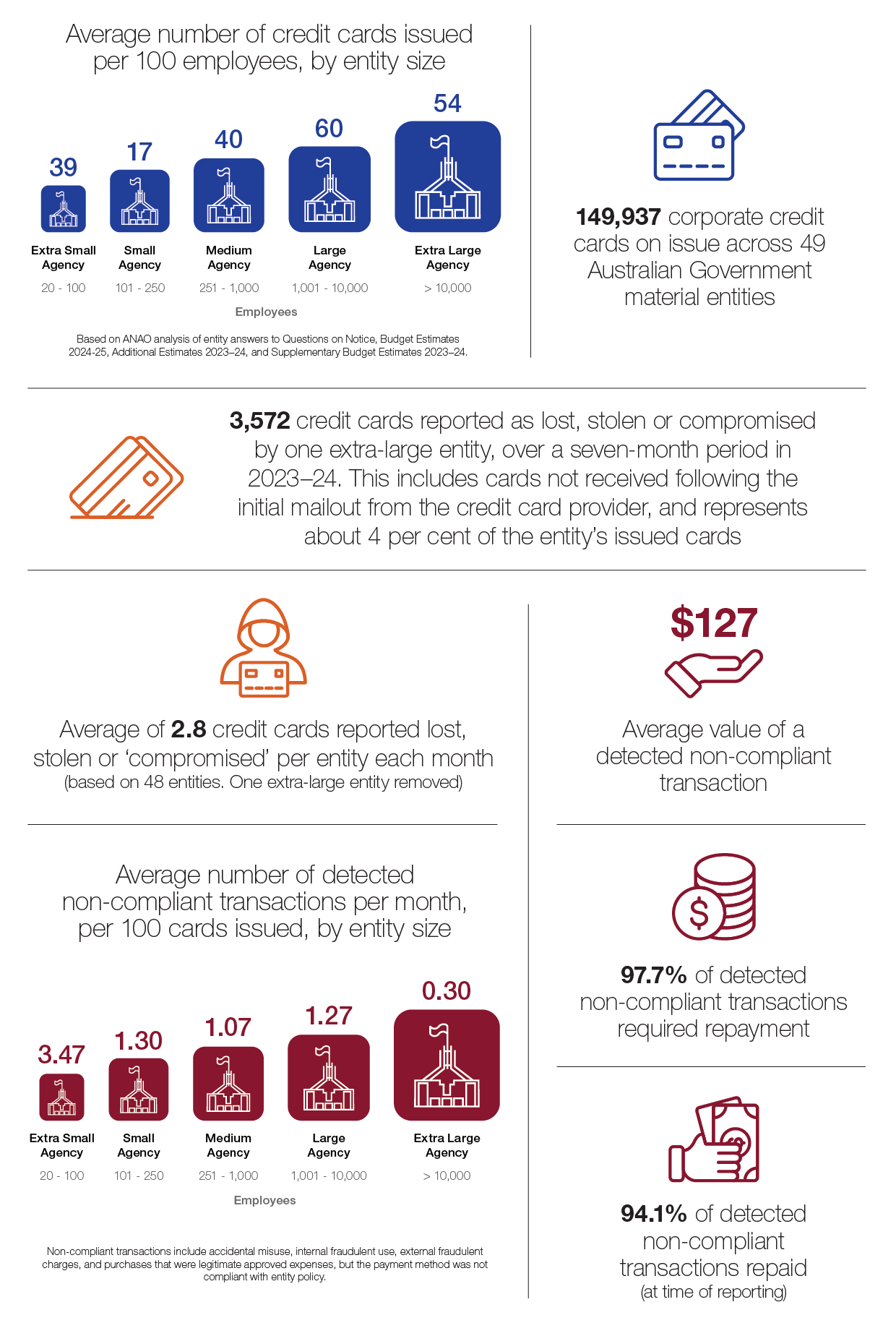

Snapshot of credit card management in the APS

Source: ANAO analysis (as at 27 September 2024) of self-reported credit card management for 49 material Australian Government entities in 2023–24.Material Australian Government entities are entities whose financial information has a material impact on whole-of-government financial statements. They include the top 99 per cent of the total general government sector.

ANAO audits of compliance with credit card requirements

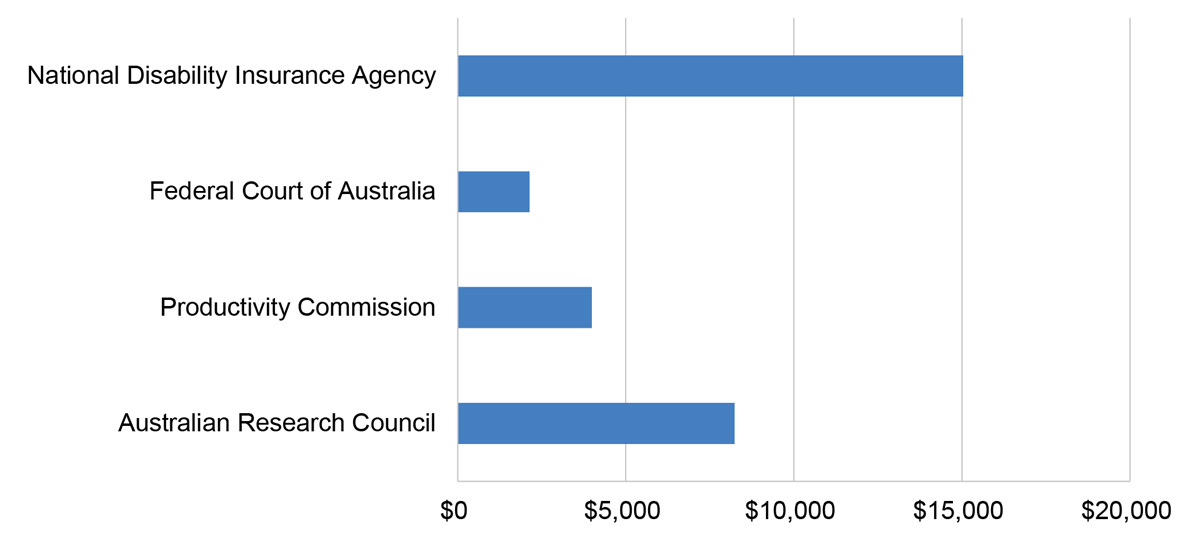

A number of ANAO performance audits between 2019–20 and 2022–23 have identified issues relating to the ineffective management of credit cards.In 2023–24, the ANAO conducted performance audits focused on four Australian Government entities’ management of corporate credit cards: National Disability Insurance Agency; Federal Court of Australia; Productivity Commission; and Australian Research Council.These entities have different profiles and approaches to the use of corporate credit cards, as outlined below.

Number of credit cards and total credit card expenditure, by entity, 2022–23

|

Entity |

Number of staff |

Number of credit cards in use |

Average number of cards per staff member |

Total expenditure by credit card ($) |

|

National Disability Insurance Agency |

5,652 |

246 |

0.04 |

3,700,000 |

|

Federal Court of Australia |

1,469 |

547 |

0.37 |

1,169,013 |

|

Productivity Commission |

192 |

258 |

1.34 |

1,029,292 |

|

Australian Research Council |

167 |

50 |

0.30 |

411,957 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Average expenditure per credit card, 2022–23

Source: ANAO analysis.

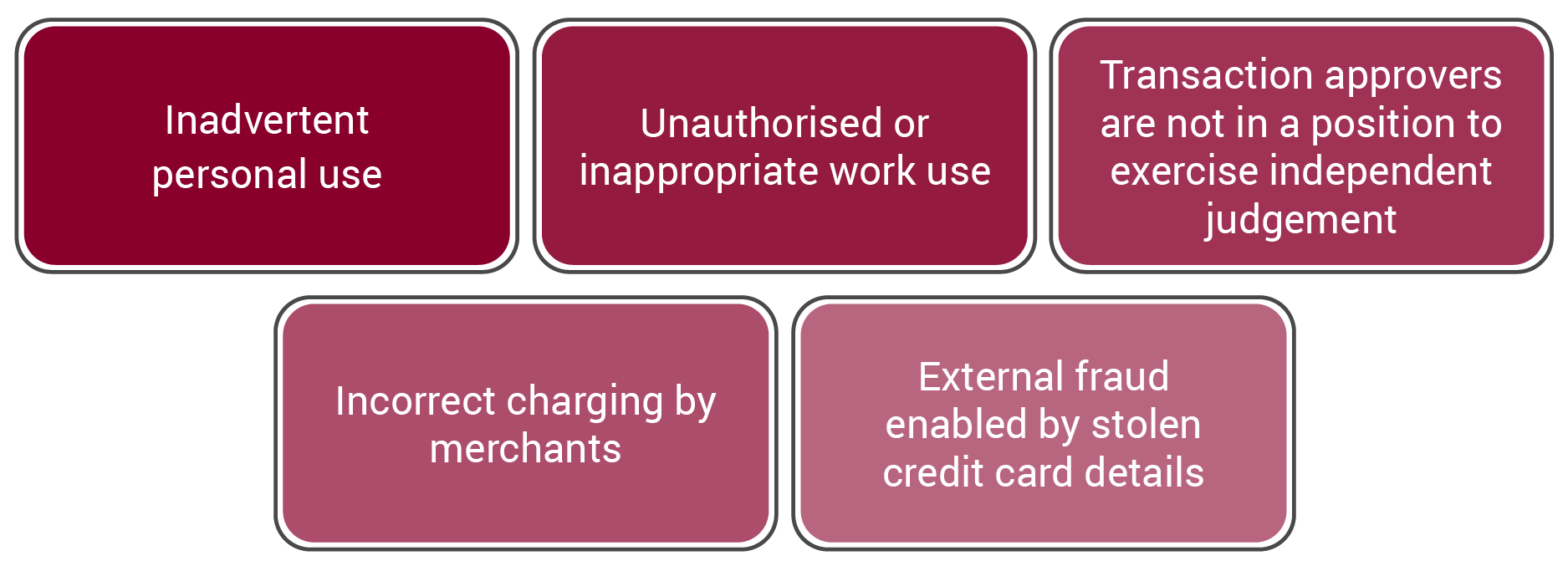

Types of credit card issues identified in ANAO audits across four entities

Note a: ‘Transaction splitting’ is where a transaction is split into smaller payments to circumvent transactional limits or procurement requirements.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Audit Lessons

This Audit Lessons sets out six lessons aimed at improving management of corporate credit cards, based on four ANAO 2023–24 performance audits on compliance with corporate credit card requirements and other relevant audits over the past five years.

1. Compliance with credit card requirements by senior executives sets the tone for the entity

2. Controls to prevent and detect credit card non-compliance are needed to address risks

3. Policies and procedures should be fit for purpose and make it straightforward for staff to do the right thing

4. Credit card training can improve levels of compliance

5. Transaction approvers should be in a position to exercise independent judgement

6. Internal audits and reporting on credit card compliance can assist with ongoing assurance and improvement

Lesson 1: Compliance with credit card requirements by senior executives sets the tone for the entity

Senior Executive Service (SES) officers set the tone for the entity. SES officers need to set a positive example for staff by demonstrating compliance with both the letter and the spirit of an entity’s integrity framework, which includes corporate credit card requirements.

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) states that the APS must maintain and foster a pro-integrity culture at the institutional level that values, acknowledges and champions doing the right thing.

The APSC states that SES officers ‘set the tone for workplace culture and expectations’, they ‘are viewed as role models of integrity and professionalism’ and ‘are expected to foster a culture that makes it safe and straightforward for employees to do the right thing’.SES officers can model integrity by:

- understanding and fulfilling their obligations for credit card use;

- complying with the letter and the spirit of credit card requirements;

- highlighting to staff that integrity should be central to every decision, including those related to the use of credit cards;

- making it safe for staff to raise concerns, admit mistakes and learn from them; and

- addressing suspected misuse of credit cards in a fair, timely and effective way.

Case study 1. SES compliance with credit card requirements

Three recent audits in the Productivity Commission (PC), National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) and the Australian Research Council (ARC) identified examples where individual SES officers did not appropriately use credit cards on matters including: non-compliance with internal policies on credit card use; lack of receipts; and splitting transactions (to circumvent transaction limits).

Lesson 2: Controls to prevent and detect credit card non-compliance are needed to address risks

Corporate credit cards are a source of fraud and corruption risk, as well as other financial risks. Accountable authorities must establish and maintain an appropriate system of internal control for the entity, including measures to ensure officials comply with the finance law.The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy supports this PGPA Act requirement.

The Fraud and Corruption Rule requires accountable authorities to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to their entities.The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policyand Finance guidancesupport these requirements.

Entities need to assess risks associated with corporate credit cards and put mitigating controls in place to prevent and detect non-compliance.

When developing controls for credit card management, an entity should consider risks in its operating environment.

Examples of corporate credit card risks

Preventive controls work by reducing the likelihood of inappropriate credit card use before it occurs. Preventive controls for credit cards could include:

- policies and procedures;

- education and training;

- deterrence messaging;

- declarations and acknowledgements to communicate and confirm that a person understands their obligations and the consequences for non-compliance;

- blocking certain categories of merchants;

- issuing cards only to those with an established business need;

- cancelling or suspending cards when staff resign or are on long-term leave;

- placing limits on available credit; and

- limiting the availability of cash advances.

Detective controls work after a credit card transaction has occurred by identifying if there is a risk that it may have been inappropriate. Detective controls for credit cards can include:

- regular acquittal and reconciliation processes (with segregation of duties between cardholder and approver);

- fraud detection software;

- detection of outlier transactions and exception reporting;

- tip-offs and public interest disclosures;

- monitoring and reporting incidents to management; and

- audits and reviews.

When detective controls identify instances of fraud or non-compliance, entities should have effective processes in place for managing investigations and follow-up actions (such as further training, sanctions, or referral to law enforcement agencies).

The Fraud and Corruption Rule requires relevant Australian Government entities to conduct periodic reviews of the effectiveness of the entity’s fraud and corruption controls. Fraud and corruption control testing can involve desktop reviews, system or process walkthroughs, data analysis, sample testing and pressure testing.Entities can strengthen their fraud and corruption control frameworks by employing different testing methods and better documenting testing outcomes.

Case study 2. Control weaknesses in credit card acquittal processes

Robust testing of controls can help identify deficiencies and potential improvements to the existing controls to ensure they are achieving their intended purpose in preventing and detecting fraud or misuse. Recently observed examples of control deficiencies include the following.

Australian Research Council

Federal Court of Australia

National Disability Insurance Agency

Productivity Commission

Lesson 3: Policies and procedures should be fit for purpose and make it straightforward for staff to do the right thing

Entities can help public servants comply with credit card requirements by ensuring credit card policies and procedures are straightforward and fit for purpose for the entity’s risks and operating environment.

Entities should ensure their policies and procedures clearly outline how credit cards are to be issued, used and returned; and what officials’ responsibilities are under the finance law. The Department of Finance has published model accountable authority instructions, which include instructions for managing corporate credit cards.These model instructions assist entities with establishing clear policies and procedures that are tailored to an entity’s operating environment and risks.

Case study 3. Policies and procedures for the issue, use and return of corporate credit cards

In 2024, the ANAO examined whether four entities had developed fit-for-purpose policies and procedures for the issue, use and return of corporate credit cards.

Australian Research Council

Federal Court of Australia

National Disability Insurance Agency

Productivity Commission

Lesson 4: Credit card training can improve levels of compliance

Delivering tailored training to credit cardholders and their supervisors on corporate credit card requirements is an effective preventive control that supports compliance. This should include periodic messaging that outlines good practices and raises awareness of fraud and non-compliance risks.

Training in the proper use of credit cards should be a prerequisite for the issuing of a credit card. All credit cardholders (including SES officers) and those with approver and reviewer responsibilities should be required to undertake induction and periodic refresher training (such as through an e-learning module). Training could outline good practice, provide clear examples of what non-compliance looks likes, and explain fraud and non-compliance risks. Monitoring training completion is important to ensure this control is operating as intended.

Case study 4. Credit card training — Productivity Commission

The ANAO examined whether the PC had developed effective training and education arrangements to promote compliance with policy and procedural requirements. The ANAO found that while the PC had published relevant policies and procedures on its intranet, it did not provide structured training and education to promote compliance with corporate credit card policy and procedural requirements.

The ANAO’s random sample of 47 PC credit card transactions included the following examples of non-compliance: no taxi card transactions had receipts; 16 transactions were not raised in the system prior to or within 48 hours of the transaction occurring; two travel-related transactions occurred on weekends, when the approved travel dates were weekdays; and there was one instance of accidental personal misuse.

Case study 5. Credit card training — Australian Securities and Investments Commission

In 2023, the ANAO examined probity management within the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), including ASIC’s management of credit cards. The ANAO found ASIC’s probity management to be largely effective and that ASIC had implemented credit card training.

Lesson 5: Transaction approvers should be in a position to exercise independent judgement

Under the PGPA Act, officials must exercise their powers, perform their functions and discharge their duties with care and diligence, honestly, in good faith and for a proper purpose.Officials also have a duty to not improperly use their position to gain a benefit or advantage for themselves or any other person.Transaction approvers must be able to fulfill these duties by being in a position to exercise independent judgement over the legitimacy of a credit card transaction.

A corporate credit cardholder’s expenditure is typically approved by their supervisor. An SES officer’s credit card expenditure should not be approved by an officer who is more junior to them (even if the approver is an SES officer). Having a more junior officer approve transactions introduces the risk that an officer will not perform their duties with the same level of care and diligence as they would if they were monitoring someone junior to them. This ‘positional authority’ risk should be considered when delegating authority to approve credit card transactions, including for key roles, such as accountable authorities.

If suitable, entities could also implement transparency measures, such as regularly reporting on the expenses of accountable authorities to audit committee chairs.

Case study 6. Managing ‘positional authority’ risk

In 2024, the ANAO examined entities’ arrangements for transaction acquittals and how entities managed the risk of ‘positional authority’ — where the approver is not in a position to exercise independent judgement.

Australian Research Council

National Disability Insurance Agency

Lesson 6: Internal audits and reporting on credit card compliance can assist with ongoing assurance and improvement

Regular reporting to executive management on credit card issue, use and return; non-compliance; and actions taken in response to non-compliance gives management visibility over the effectiveness of internal controls. It can also provide insights into fraud and integrity risks within the entity and help executive management to better understand and manage these risks.

Entities should include a rolling program of internal audits that examine key internal controls, including controls for corporate credit card management.

Reporting on credit card non-compliance can provide assurance to the accountable authority, the executive committee, the audit committee and other relevant governance committees. Timely and accurate internal reporting of credit card use is important to address risks and issues as they occur. Internal audits are a valuable way to identify opportunities for improvement and highlight areas of risk.

Case study 7. Reporting on credit card use and misuse

The ANAO’s review of the PC’s reporting on credit card use found the following.

Case study 8. Internal audits

As part of the examination of whether entities had appropriate arrangements for managing credit card risks, the ANAO examined whether credit card management had been the subject of a recent internal audit.

Australian Research Council

- An internal audit was completed in 2021–22 on reporting and monitoring of operational risks that exceed the ARC’s risk appetite. The internal audit did not directly consider credit card risk, but stated that ‘the ARC’s overall approach to undertaking the review process provides adequate assurance that it is complying with its financial management obligations under Finance Law’.

Federal Court of Australia

- Two internal audits relevant to corporate credit cards were undertaken and reported to the FCA’s audit and risk committee, one in 2017 and one in 2023.

Productivity Commission

- An internal audit on key financial controls was completed in 2022, which included a review of the PC’s use of credit cards. The internal audit identified five ‘agreed actions’ related to credit cards.

Further reading

ANAO links

- Fraud Control Arrangements | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Probity Management: Lessons from Audits of Financial Regulators | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Procurement and Contract Management | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Risk Management | Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)

External links

- Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) - (RMG 206) | Department of Finance

- APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- APS Values, Code of Conduct and Employment Principles | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework 2024 | Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre (counterfraud.gov.au)

- Fact sheet: Pro-integrity culture | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- Fact sheet: Upholding integrity | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud and corruption (RMG 201) | Department of Finance

- Supplier Pay On-Time or Pay Interest Policy (RMG 417) | Department of Finance