Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Currently showing reports relevant to the Economics Senate estimates committee. [Remove filter]

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The National Reconstruction Fund was announced by the Minister for Industry and Science on 25 October 20221, as part of the 2022–23 Federal Budget, as a $15 billion investment to ‘diversify and transform Australia’s industry and economy.’

2. The Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) took the lead for the design and establishment of the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC). The Department of Finance provided support to DISR in the design and establishment of the NRFC.

3. The NRFC is a corporate Commonwealth entity established under the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Act 2023 (NRFC Act). It commenced on 18 September 2023 and is governed by an independent board. Under the NRFC Act, the Minister for Industry and Science and the Minister for Finance are the responsible ministers. In performing its investment functions, the NRFC Board is required to comply with the NRFC Act, the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (Investment Mandate) Direction 2023 (NRFC Investment Mandate)2 and the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (Priority Areas) Declaration 2023.3

4. On 19 November 2024, the NRFC announced its first two investments: a $100 million partnership with Resource Capital Funds, which includes a $40 million investment in Russell Mineral Equipment.4 As at 31 May 2025, the NRFC has announced nine investments totalling $434.5 million.5

5. In December 2024, Parliament passed the Future Made in Australia Act 2024. The Future Made in Australia measure establishes a ‘Front Door for investors with major transformational proposals within the Treasury portfolio’6, an Investor Council to support the Front Door and the involvement of Specialist Investment Vehicles in the Investor Council.7

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. The NRFC was announced on 25 October 2022 as a $15 billion vehicle through which the Australian Government will ‘facilitate increased flows of finance into priority areas of the Australian economy, through targeted investments to diversify and transform Australian industry, create secure, well-paying jobs and boost sovereign capability.’

7. The audit provides assurance to the Parliament as to whether the design and establishment of the NRFC was effective.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and establishment of the NRFC.

9. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Was the design process effective?

- Are governance arrangements sound?

- Are the Fund arrangements effective?

Conclusion

10. The design of the NRFC was largely effective, the establishment of the NRFC’s governance and fund arrangements was partly effective. There are opportunities to improve NRFC’s governance by establishing a financial strategy and reviewing its performance reporting. Further, there is scope for the NRFC Board to finalise its investment strategy, stakeholder engagement framework and some investment procedures, and to establish assurance over its investment compliance.

11. The design process for the NRFC was largely effective. Due diligence checks for one member of the NRFC Board were not documented. DISR applied lessons from similar programs and considered stakeholder feedback. Stakeholder engagement was largely consistent with better practice — with opportunities to close the loop with stakeholders, and documenting lessons to improve future engagement activities. Constitutional risks to investments were assessed and approaches to manage these were outlined in advice to government and the NRFC Board. Advice on establishing a new corporate Commonwealth entity was sound. Appointments to the NRFC Board were consistent with the NRFC Act.

12. NRFC’s governance arrangements are largely sound. The NRFC Board and CEO appointments, Board meetings and remuneration arrangements have been established under the NRFC Act. Investment Policies have been published pursuant to section 75 of the NRFC Act. NRFC’s reporting arrangements for its annual report, corporate plan, budget estimates, performance measures and statements have been established, with 2024–25 performance to be reported against ‘at least three identified areas of the economy’ out of seven under the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (Priority Areas) Declaration 2023. NRFC’s risk management, fraud and corruption control arrangements, and accountable authority instructions are underway and progressing as at March 2025. NRFC’s corporate policies are progressing as at March 2025. The NRFC Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) reviewed NRFC’s arrangements for risk management, internal controls, financial reporting except it did not review NRFC’s performance reporting arrangements for 2023–24 in line with the ARC charter and section 17 of the PGPA Rule. Recruitment is continuing, with the asset management function for investments underway as at March 2025. NRFC Board is yet to develop a financial strategy. NRFC has processes for managing procurement, recruitment, declaring gifts and benefits, and Freedom of Information (FOI). Access to NRFC’s released information under FOI is not consistent with guidelines from the Australian Information Commissioner.

13. NRFC’s fund management arrangements are partly effective. The NRFC Board has approved investments without finalising its investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework. NRFC’s investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework, listed as outputs within NRFC’s Corporate Plan 2023–24, were not completed. A draft investment strategy, draft stakeholder engagement framework, and the absence of a plan to evaluate them, limits the effectiveness of the NRFC Board’s fund promotion.

14. NRFC’s processes to assess investments against its legislative requirements are developing and partly effective. NRFC’s existing procedures relating to due diligence, risk management and assessing concessionality need clearly defined requirements for officials. NRFC is developing investment procedures relating to: credit risk, national security assessments, and investment impact. Investment assessment processes have gaps in: due diligence, risk management, and considerations of concessionality. NRFC’s Board has not received its Embargo Register to manage associated risks. NRFC did not obtain conflict of interest declarations and confidentiality agreements from suppliers who assisted with investment due diligence.

15. NRFC has established investment targets; and as at 31 May 2025, NRFC had announced investments totalling $434.5 million of a target of $550 million. At at 31 March 2025, NRFC’s Board has not developed a financial strategy and aligned it to its draft investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework, to inform and support the timely deployment of its investments.

Supporting findings

Design process

16. Lessons from similar programs were considered and addressed in the design and establishment of the NRFC. DISR assessed external reviews of Specialist Investment Vehicles (SIVs), prior ANAO audits and engaged with stakeholders to identify lessons on the design and establishment of the NRFC. A key lesson relating to the need for investment-ready projects for the NRFC, and steps to address this were outlined in advice to government. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.11)

17. Stakeholder input on key design parameters of the NRFC was considered and included in advice to government. DISR undertook a structured approach to consulting stakeholders and analysing feedback received. Stakeholder engagement was largely consistent with the APS framework for engagement and participation — with opportunities to close the loop with all stakeholders who have contributed, and documenting lessons to improve future engagement activities being identified. (See paragraphs 2.12 to 2.18)

18. DISR established an appropriate framework for providing advice to government. Advice was based on lessons learned from other SIVs, stakeholder input, and understanding the policy context of the election commitment. Advice outlined risks and approaches to manage risks. Advice on a corporate Commonwealth entity (CCE) being the preferred vehicle to establish the NRFC was based on DISR’s assessment that a CCE provided the most effective way to achieve policy objectives, and was most closely aligned with the election commitment of the NRFC being modelled on the Clean Energy Finance Corporation. Appointments to the NRFC Board were consistent with NRFC Act, except that due diligence checks were not documented for one member appointed to the NRFC Board in October 2023. (See paragraphs 2.19 to 2.55)

Governance arrangements

19. NRFC Board and CEO appointments, Board meetings and the Board and CEO’s remuneration arrangements have been established under the NRFC Act. A Board skills matrix was developed for commencement appointments. NRFC Board members, NRFC CEOs and acting CEO made conflicts of interest declarations and maintain conflicts of interest registers. NRFC experienced leadership changes in the 16 months from its commencement to January 2025, with two CEO appointments and two acting CEO appointments. NRFC has established its risk management, fraud and corruption risk management and reporting arrangements under the PGPA Act, with some elements in progress. The NRFC ARC reviewed NRFC’s arrangements for risk management, internal controls, financial reporting except for NRFC’s performance reporting. Corporate policies continue to be in progress as at March 2025. The NRFC Board has yet to develop a financial strategy to support its financial sustainability and return on investment. Processes are in place for managing procurements, recruitment, declaring gifts and benefits, and managing Freedom of Information, with an opportunity to make available released information for downloading from its website. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.57)

20. NRFC has established its Investment Policies under section 75 of the NRFC Act. The NRFC Board has established the Board Investment Committee to provide oversight of investment decision processes, including investment delegations and policies for managing conflicts of interest and personal trading. Recruitment for roles supporting investments management was continuing as at March 2025, and the investments were made prior to establishing the investment asset management function. (See paragraphs 3.58 to 3.71)

21. NRFC has established and published its performance measures in its Corporate Plan 2023–24 and Corporate Plan 2024–25. NRFC reported in its 2023–24 performance statement that it had achieved its performance measure of finalising its core corporate, risk and investment policies. These ‘core’ policies were not defined and there were 39 policies and related documents outstanding at June 2024. NRFC’s performance measures in 2024–25 incorporate measures to report that investments meet at least three of the seven economic priority areas, there is an opportunity to ensure that measures in future years report against all seven economic priority areas. Controls for performance information and methodologies for performance reporting are in development as at March 2025. (See paragraphs 3.72 to 3.79)

Fund arrangements

22. NRFC’s Board and senior executives have engaged with Commonwealth entities, industry stakeholders and prospective applicants. NRFC’s Corporate Plans for 2023–24 and 2024–25 have set out objectives and performance measures for partnering and engaging with stakeholders. In October 2023, the NRFC Board decided to formalise engagement activities. NRFC’s investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework were in draft and not finalised in 2023–24. A Stakeholder Engagement Strategy was approved by the NRFC Executive Leadership Team in May 2025. NRFC does not have a plan to periodically evaluate the effectiveness of its engagement activities. NRFC’s outputs relating to its investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework outlined in its Corporate Plan 2023–24 were not completed. NRFC has made investment decisions and engaged with stakeholders without an endorsed investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework. A draft investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework limit the effectiveness of the NFRC Board’s fund promotion activities to achieve the performance measures it has set to deliver NRFC’s performance outcomes. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.9)

23. NRFC’s processes and controls to assess and approve applications are developing as at March 2025. NRFC’s existing investment procedures address its legislative requirements except for national security and First Nations impact, which are under development. NRFC’s approach to assessing investments has gaps in due diligence, investment risk assessment, and concessionality. These gaps impact the consistency of investment assessments, completeness of risk advice provided to the NRFC Board, and the NRFC Board’s assurance over compliance with its legislative requirements. The NRFC Board has not received updates on the Embargo Register to prevent members from inadvertently dealing in entities on whom the NRFC holds inside information. NRFC has not obtained confidentiality agreements or conflict of interest declarations from suppliers undertaking due diligence on investments. There is scope to improve the consistency of documenting how NRFC’s investments crowd-in and do not crowd-out other market participants. (See paragraphs 4.12 to 4.62)

24. NRFC’s budget estimates and performance measures establish investment targets across the current and forward years from 2024–25 to 2027–28. As at 31 May 2025, NRFC had announced investments totalling $434.5 million against a target of $550 million for 2024–25. The NRFC Board has established quarterly monitoring arrangements for its investment target through its ‘Operating Plan FY2025.’ NRFC took between six and nine months to assess and approve investments reviewed by the ANAO. As at 31 March 2025, NRFC’s Board has not developed a financial strategy that links with its investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework to support it to deploy investments in a timely manner, and to generate returns to fund its operating expenses. (See paragraphs 4.67 to 4.71)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.23

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Board establish a financial strategy to support its activities to maintain financial viability and return on investment.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.35

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Board ensure that the Audit and Risk Committee review all future performance reporting arrangements in accordance with its charter and to ensure its compliance with paragraph 17(2)(b) of the PGPA Rule.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.10

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Board finalise its investment strategy and stakeholder engagement framework and develop a plan to evaluate effectiveness.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.35

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation:

- obtain conflict of interest declarations from its suppliers who assist with investment due diligence and re-validate declarations when the due diligence report is finalised, as part of the monitoring of conflicts of interests; and

- execute confidentiality agreements with suppliers who assist it with its investments.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.45

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Board should be informed of the risks associated with its Embargo Register.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.63

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Board:

- ensure existing procedures outline the roles and responsibilities of relevant officials and executives and set out the minimum requirements for due diligence, risk management, assessing concessionality and record keeping; and

- finalise and endorse investment procedures that are under development to assess, approve and manage investments.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.64

The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Board establish assurance arrangements and assign responsibilities to ensure the consistent:

- application of investments in accordance with the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation Act 2023 and National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (Investment Mandate) Direction 2023; and

- storage of records for investment assessment processes, assessments and decisions.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

25. Relevant parts of the proposed audit report were provided to the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, and the Department of Finance. Summary responses are reproduced below and full responses are at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

National Reconstruction Fund Corporation

The NRFC welcomes the ANAO’s report and its finding that the NRFC’s governance arrangements are largely sound. As the report notes, the NRFC was established on 18 September 2023, with the performance audit commencing less than a year into its operations. This early assessment of the Corporation’s governance processes provides assurance of the direction taken and offers useful insights to inform the Corporation’s commitment to continuous improvement.

The NRFC agrees with all recommendations and is committed to their implementation in a timely manner. We note that in all areas identified by the ANAO, active steps are being taken to ensure effective governance processes, including a number of areas where the recommended actions are already complete or where significant progress has already been achieved. Further work is underway to fully implement the remaining recommendations. The NRFC’s Audit and Risk Committee will oversee this implementation.

Department of Industry, Science and Resources

The department acknowledges the opportunity to comment on the report, noting it only had access to extracts relevant to the department.

In 2022, the Australian Government committed to establishing the National Reconstruction Fund (NRF) to support, diversify and transform Australia’s industry and economy.

To inform the NRF’s design, the department conducted extensive stakeholder engagement and public consultation. This included input from government and external stakeholders. Participants included representatives from business, unions, financial institutions, First Nations communities, regional groups, government and the public. This comprehensive process informed the NRFC’s structure, legislation, and successful establishment by September 2023.

In response to the one identified opportunity for improvement, the department acknowledges the release of RMG 127 in July 2024 and has updated its processes to ensure alignment with this latest guidance.

Department of Finance

The Department of Finance (Finance) welcomes ANAO’s performance audit report on the Design and Establishment of the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (Report). The report concludes that the implementation and governance of the NRFC was largely effective. Finance notes that the due diligence documentation did not meet the standard of Resource Management Guide 127 – Specialist Investment Vehicles (RMG 127), however this guide was not in place at the time of the appointment.

Finance agrees with the ANAO’s suggested area for improvement to document NRFC board appointment processes. Consistent with guidance in RMG 127, Finance commits to ensuring that all board appointment processes and considerations are thoroughly and accurately documented. This includes retaining all relevant records to ensure transparency and accountability. Finance has already implemented these measures to support the effective governance and oversight of the National Reconstruction Fund Corporation (NRFC).

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

26. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Transparency of reporting

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is the principal revenue collection agency of the Australian Government. Its purpose is ‘to contribute to the economic and social wellbeing of Australians by fostering willing participation in the tax, superannuation and registry systems.’1 Having strong organisational capability, including information and communication technology (ICT) capability, directly contributes to delivering the ATO’s purpose and activities. An action that the ATO is taking to manage strategic technology risks is investment across its technology environment, including procurement for a range of IT managed services between 2022–2024.2

2. As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity, the ATO must comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs)3 and the Australian Government Digital Sourcing Contract Limits and Reviews Policy. Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs. The Australian Government Digital Sourcing Contract Limits and Reviews Policy’s three main requirements for contracts signed from 1 February 2020 are: contracts must not exceed $100 million exclusive of GST (including all extensions); contracts must not exceed a three-year initial term; and contract extension options must not exceed three years and can only be used after a review of contractor performance and deliverables.

3. The IT Strategic Sourcing Program (ITSSP) was established in February 2021 to strategically plan how the ATO would procure services to replace five ICT contracts with an estimated value of $3,748.7 million, with contracts due to expire between November 2023 and December 2025. The ATO approached the market in three waves, for seven requests for tender, between March and November 2022. It entered into eight contracts for IT managed services between December 2022 and June 2024.

4. Each of the ITSSP procurement processes were supported by external advisors. The ATO engaged six external advisors. The total value of the advisor contracts is estimated to be $88.11 million. The six advisor contracts commenced between April 2021 and February 2022. The contracted services were for advice relating to strategic sourcing, technical, probity, legal, financial assurance and project management.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The ATO was procuring IT managed services as a material portion of its IT contract arrangements are due to expire. It was estimated that the new contracts would be valued at $2,536 million over 10 years if contract extension options are used (see paragraph 1.15). These contracts affect all ATO staff, clients and service delivery.

6. A cross entity audit of Establishment and Use of ICT Related Procurement Panels and Arrangements that included ATO was tabled in August 2020. That audit identified issues with ATO’s IT procurement, including that ATO did not meet the conditions for limited tender (including that there was no evidence of market research and that advice regarding risks to achieving value for money was not provided to the delegate), and that there was no or insufficient documentation of value for money and risk management, including probity risk management.

7. This audit provides assurance to Parliament about the ATO’s compliance with the CPRs for the procurement of IT managed services.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of ATO’s procurement of IT managed services.

9. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Has the ATO established sound governance arrangements for the IT managed services procurements?

- Has the ATO conducted the procurements in compliance with Commonwealth Procurement Rules and other requirements?

Conclusion

10. The ATO’s procurement of IT managed services was largely effective. Procurement activities for IT managed services were largely in line with the CPRs, including market engagement and soundings, and demonstrating value for money. There were, however, some shortcomings such as the ATO failing to observe core elements of the CPRs when conducting the legal services procurement, and not appropriately managing probity risks including declaring and managing conflicts of interest of the IT Strategic Sourcing Program delegate.

11. The ATO established largely sound governance arrangements for the IT managed services procurements. It established governance and oversight arrangements, procurement policies and procedures, and undertook market research to inform the design of its procurement strategy and plans. During planning, the program governance arrangements did not sufficiently distinguish endorsement and decision-making roles when seeking approvals. There were instances where the delegate, who was also the chair of the steering committee, provided approval to procurement planning related documentation and not separate delegate approval. Contrary to finance law in some instances Chief Executive Instructions (CEIs) were not consistently issued and approved by the accountable authority.

12. The ATO largely met core requirements of the CPRs except for probity management and conflict of interest. Mainframe Services and Hardware, Enterprise Operations and Technical Enablement (EOTE) and strategic sourcing partner procurements were largely in compliance with CPRs and other requirements. The approach to market and evaluation of the legal services procurement were not consistent with the intent of the CPRs4, and all required records were not maintained. The effectiveness of ATO’s management of probity risks could have been improved by ensuring that incumbent provider probity plans were approved by the ATO, and probity register records were effectively maintained. In addition, conflict of interest processes could have been better managed, including to address risks in a timely manner. Demonstration of value for money for the six advisor procurements was deficient with the cost of advisor contracts increasing from a total estimated value when approving the initial contracts of $19.06 million to a total value of $88.11 million, as at February 2025.

Supporting findings

Procurement governance and planning

13. A governance framework was implemented for the IT Strategic Sourcing Program (ITSSP), with the Chief Information Officer (CIO) as the delegate and senior accountable officer. Program risks were identified, assessed and managed. The initial planned completion including transition for the ITSSP was June 2024, this has been revised to December 2025. All procurements were completed and contracts signed by 20 June 2024 and transition is anticipated to be completed by December 2025. The steering committee considered options and risks to manage delays and impact on budget and timeframe. In some instances, consensus decision-making arrangements that were established through a steering committee led to a lack of clarity about when the delegate was exercising their delegation to make decisions. Over a period of 41 months there were 34 versions of the Chief Finance Officer’s (CFO’s) delegation schedules. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.31)

14. CEIs, procedures and guidance support ATO officials to undertake procurement in accordance with the CPRs. The ATO’s policy framework establishes arrangements where officers, other than the Commissioner, can approve and issue CEIs under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and the Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act). This has led to some instances where the Commissioner has not approved and issued CEIs that were required to be made under section 20A of the PGPA Act. The ATO’s CEIs, procedures and guidance align with the CPRs. The ITSSP applied the existing ATO procurement framework to the IT managed services and advisor procurements. (See paragraphs 2.32 to 2.50)

15. The ATO conducted redesign and planning activities in 2021 and 2022. Its annual procurement plan provided advance notice to the market of the planned ITSSP procurement. Market research supporting the procurement strategy included early market engagement through a request for information (RFI), a technology horizon scan, a market comparison report and like-sized agency comparison. For each of these activities there was clear advice to the steering committee and delegate about outcomes and how they inform the procurement approach. A procurement plan for the ITSSP set out the procurement strategy. Procurement plans were developed for the selected ITSSP and advisor procurements, except for the legal services procurement. (See paragraphs 2.51 to 2.71)

IT and advisor procurement processes

16. Approaches to market were fair and transparent for the selected procurements, except for the legal services procurement. Approach to market documentation apart from the legal services procurement was compliant with the CPRs with a few exceptions. For example, the request documentation was not a complete description in compliance with paragraph 10(6)(d) of the CPRs as there were instances where changes were subsequently made to the request for tender (RFT) evaluation criteria (such as the relative importance of the criteria) in the evaluation plan or report. The legal services advisor procurement did not demonstrate good practice as the ATO approached one supplier to quote for services and did not include evaluation criteria, with costs increasing from an initial quote of $665,500 to $10.9 million. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.18)

17. Tender evaluation plans were prepared for the selected ITSSP procurements prior to tenders closing. While a tender evaluation plan was prepared for the strategic sourcing partner procurement, it was not finalised prior to quotes closing. Instances of inconsistencies between evaluation criteria weightings presented in procurement plans, RFTs, evaluation plans and those applied during evaluation were: sub-criteria weightings were not included in the procurement plan or RFT; and priority rankings set were not included in the evaluation report. Non-compliant and unsuccessful tenderers were not notified promptly of outcomes of the evaluation phase for both of the selected ITSSP procurements. The legal services procurement did not develop an evaluation plan, involve an evaluation or meet mandatory reporting timeframes for contract notices on AusTender. (See paragraphs 3.19 to 3.48)

18. To support the management of probity risks for the ITSSP, the ATO appointed an external probity advisor, developed a probity plan and probity protocols, maintained a register of probity briefings, maintained a probity register, and maintained a register of probity cleared personnel (ATO staff and advisors). Some probity requirements, such as approval and review of incumbent provider management plans, were not fully implemented and records in registers were incomplete, impacting the ATO’s ability to manage probity, including conflicts of interest. Probity arrangements, including the management of conflict of interest, were established and largely implemented for one of the two selected advisor procurements. (See paragraphs 3.49 to 3.100)

19. The ATO has an established process for the management of conflict of interest, with additional processes introduced for the ITSSP. Not all elements of the process were followed, including for key personnel exercising delegation. Not all conflict of interest declarations were made (for example, a delegate was not asked to complete an initial conflict of interest declaration for the ITSSP) or were not made in a timely manner (for example, the ITSSP delegate did not declare a conflict for the first 12 months of the program), did not contain sufficient detail for the approver to make an informed decision (for example, three of the four officers that declared a shareholding did not report the quantum or value of the shareholding in all declarations), and did not contain a detailed management plan to support monitoring and assessment of their implementation. Record keeping was incomplete. (See paragraphs 3.75 to 3.100)

20. Advice was provided to the decision-maker at key stages throughout the selected procurements and approvals were documented, apart from the legal services procurement. The ATO documented value for money assessments for the selected ITSSP procurements and strategic sourcing partner procurement. An assessment of value for money was not documented for the legal services procurement. The ATO considered how the unit price of IT professional services changed over the period of the EOTE procurement process when assessing value for money, it did not consider other potential changes to the market such as new entrants and how this might impact value for money. The value of advisor procurements increased significantly throughout the life of the program without ongoing assessment of whether the services continued to represent value for money. (See paragraphs 3.103 to 3.123)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.14

When establishing program governance arrangements which includes procurement, the Australian Taxation Office ensure that: decision-making responsibilities are clearly set out, including to separate endorsement and decision-making roles; and processes support the appropriate decision-maker to make a decision.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.42

Consistent with section 20A and paragraph 110(2)(aa) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) the Commissioner for Taxation should issue and approve all accountable authority instructions. To achieve this, the Australian Taxation Office should:

- review its policy framework to ensure compliance with the PGPA Act and Public Service Act 1999;

- refer to instructions made under section 20A of the PGPA Act as accountable authority or Commissioner’s instructions; and

- where instructions are made for conflict of interest and security they be issued under section 20A of the PGPA Act.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.100

When declaring and managing conflicts of interest in relation to procurement, the Australian Taxation Office:

- ensure conflicts of interest are declared in a timely manner and declarations contain sufficient detail about the conflict to support an assessment of its nature and risk;

- apply treatments to declared conflicts that are commensurate with the nature and risk associated with the conflict, and provide sufficient detail about the actions to be taken and when they should be taken to support implementation and monitoring;

- have regard to previous declarations and management plans to ensure consistency and completeness; and

- ensure when new resources are added to a procurement, including senior executives, and when new suppliers tender or quote, that personnel complete the conflict of interest declaration process.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.119

For ancillary services, the Australian Taxation Office apply an appropriate amount of rigour when assessing value for money. Consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) the assessment should be commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of a procurement (CPRs paragraphs 4.4 and 6.2), and must consider whole of life costs (CPRs paragraph 4.5).

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to ATO, with an extract being provided to the former CIO. The ATO’s summary is provided below, and its full response is included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO welcomes the audit findings that the ATO conducted largely effective and compliant procurements for IT managed services with largely sound governance.

We accept all 4 recommendations and have commenced or completed improvements prior to, throughout, and subsequent to, the audit. Over the past three years, the ATO has made improvements to our procurement processes, Chief Executive Instructions, probity processes and policies to maintain the integrity of procurement outcomes. We will continue to strengthen our governance processes and ensure alignment with best practice.

The procurements examined through this audit set out to break-down and replace 5 contracts of significant scale and complexity prior to expiry. These contracts underpin the delivery of the ATO’s digital and ICT services to all Australians. We established 8 new contracts through open, transparent and competitive tenders that have delivered better outcomes.

Large IT procurements are challenging, needing robust governance, and forecasting of market trends and organisational demands while carefully balancing stability against transformation. The ATO is proud of the work the organisation has done in conjunction with the market to deliver this outcome.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Program design

Procurement

Conflicts of interest

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In July 2023, the Australian Government released a national wellbeing framework called Measuring What Matters (MWM). The Department of the Treasury (Treasury), as the policy owner for MWM, described the purpose for MWM was to construct a more complete picture of societal progress and enable government to better set and communicate policy priorities. Treasury stated a national wellbeing framework was important for better measurement of the progress of all Australians beyond economic measures. Treasury identified five themes for MWM — healthy, secure, sustainable, cohesive and prosperous — supported by 12 dimensions that describe aspects of the wellbeing themes and 50 key indicators1, to monitor and track progress, which will be updated over time.2

Rationale for undertaking the audit

2. The Australian Government has stated that MWM is ‘an important foundation on which we can build — to understand, measure and improve on the things that matter to Australians’.

3. This audit provides assurance to Parliament that the MWM framework was effectively designed and developed; and that Treasury’s arrangements to support implementation are effective.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Treasury’s design and implementation of the Measuring What Matters framework.

5. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were examined.

- Did Treasury effectively design and develop Measuring What Matters?

- Are arrangements to support the implementation of Measuring What Matters effective?

Conclusion

6. Treasury was largely effective in designing and implementing the Measuring What Matters framework. While Treasury had provided sound policy advice and considered practical implementation, it did not have arrangements in place to assess if MWM was meeting its policy objective.

7. Treasury was largely effective in its design and development of MWM. MWM was supported by sound policy advice and considered practical policy implementation. There was no evaluation plan to measure the effectiveness of the MWM framework. Treasury conducted stakeholder consultation with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally. Treasury did not document the rationale for how themes and indicators were selected based on the consultation feedback.

8. Treasury had largely effective arrangements in place to support the implementation activities for embedding MWM. Treasury facilitates discussions on MWM across government through an interdepartmental committee. Treasury has made progress to embed MWM into policy design and consulted with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) to improve the data quality. There are no arrangements in place to monitor, report or evaluate whether MWM is achieving its intended policy objective. The second MWM statement is intended to be released in 2026. Treasury does not have arrangements in place to facilitate the publication of the next MWM statement.

Supporting findings

Design and development

9. Treasury defined the intent of the policy and how outcomes would be measured. Treasury considered ways of integrating quantitative data into the MWM framework, and analysed information to select indicators based on qualitative data and quantitative measures. The policy advice identified risk and potential mitigation strategies. Treasury did not document decisions made to show linkages between data analysis and conclusions. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.22)

10. Treasury researched and consulted on other wellbeing frameworks used globally, and tested indicators with other government entities to determine if indicators were practical to implement. The design process considered policy evaluation in relation to indicators. Treasury is considering how to embed the MWM framework into policy-making processes. There is no evaluation plan in place to measure the effectiveness of the MWM framework. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.30)

11. Before the release of MWM in July 2023, Treasury consulted with stakeholders to design the themes, dimensions and indicators. The consultation consisted of meetings with government and non-government bodies domestically and internationally; and two public submission rounds. Treasury provided public updates throughout the consultation process. Treasury received feedback from the public wanting more time for consultations. Treasury did not document the rationale for how themes and indicators were selected based on the consultation feedback. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.71)

Planning for implementation

12. Treasury established an interdepartmental committee to facilitate discussions and seek feedback on MWM across government. Treasury worked with the ABS to provide advice to government and received funding for the ABS to reinstate and expand the General Social Survey as a dedicated survey for MWM. Treasury has made progress to embed MWM into policy design across government. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.37)

13. There are no monitoring or evaluation arrangements in place to measure the embedding of MWM across government. Treasury provides reports externally through the MWM dashboard and statement. The second MWM statement is intended to be released in 2026. Treasury does not have arrangements in place to facilitate the development and publication of the next MWM statement. (See paragraphs 3.38 to 3.48)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.42

To ensure Measuring What Matters is achieving its desired outcome, the Department of the Treasury establish arrangements for monitoring and evaluating how Measuring What Matters is being embedded across government to achieve its intended outcome.

Department of the Treasury’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.48

The Department of the Treasury implement arrangements for developing and publishing the next Measuring What Matters statement.

Department of the Treasury’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

14. The proposed audit report was provided to Treasury. Treasury’s summary response is reproduced below. The full response from Treasury is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

Treasury welcomes the report’s conclusion that it was largely effective in providing advice to Government regarding the design and implementation of the Measuring What Matters framework. Treasury welcomes the key messages that it provided sound policy advice, considered practical implementation of the framework and consulted broadly at all stages of design and implementation.

Treasury agrees with the recommendations presented in the report. As part of the work to implement Measuring What Matters, Treasury will establish arrangements for monitoring and evaluating progress toward achieving its intended outcomes and will design a plan to develop and publish the 2026 Measuring What Matters Statement.

Implementation and closure of these recommendations will be monitored by our Audit and Risk Committee.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

15. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Stewardship of strategies, policies and frameworks

Shared delivery and shared risk

Record keeping

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is the principal revenue collection agency of the Australian Government. Its roles and responsibilities include administering legislation governing tax, superannuation and the Australian Business Register. The ATO’s corporate plan 2024–251 outlines a strategic objective to ensure its client experience and interactions are ‘well designed, tailored, fair, transparent.’ This objective includes a core priority to ‘enable trust and confidence through policy, sound law design and interpretation, as well as resolving disputes’.

2. The ATO Charter (the Charter) outlines the ATO’s commitments to its clients and what can be expected in interactions with the ATO.2 Under the Charter, the ATO is obligated to be fair and reasonable, provide professional service, provide support and assistance, keep clients’ data and privacy secure, and keep the community informed. This includes working with clients to address concerns and informing them how to make a complaint. The Charter provides ‘we treat all complaints seriously and aim to resolve them quickly and fairly.’

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Better Practice Complaint Handling Guide states that ‘Australian Public Service agencies and contractors must deliver high quality programs and services to the Australian community in a way that is fair, transparent, timely, respectful and effective’3, and that ‘[g]ood complaint handling will also help meet general principles of good administration, including fairness, transparency, accountability, accessibility and efficiency’.4 Between 2020–21 and 2023–24 the number of complaints received by the ATO, including those referred by the Inspector-General of Taxation and Taxation Ombudsman (IGTO), increased from 24,740 to 49,414.

4. This audit will provide assurance to Parliament of the Australian Taxation Office’s effectiveness in managing complaints, including engaging with complainants, resolving complaints, and the implementation of relevant IGTO recommendations.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The audit objective was to assess the Australian Taxation Office’s effectiveness in managing complaints.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Does the ATO have fit-for-purpose arrangements to support the effective handling of complaints?

- Does the ATO report on complaints, effectively review its complaints management framework, and seek to improve processes and service delivery?

- Were agreed recommendations from the Inspector-General of Taxation regarding ATO complaint handling effectively implemented?

Conclusion

7. The ATO’s management of complaints is largely effective. Effectiveness would be improved if the ATO’s analysis of its complaints data also sought to identify the underlying causes of complaints and used this information to improve business processes and complaint handling.

8. The ATO’s complaints management framework is largely aligned with the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Better Practice Complaints Handling Guide. The complaints process is accessible through multiple channels, and complaints are triaged to allocate complaints to resolvers with appropriate experience. The ATO seeks to resolve complaints at first contact. The proportion of complaints resolved at first contact has declined over the last four financial years. The ATO uses timeliness of complaint handling as its indicator for efficiency. The process is reliant on complainant feedback to improve accessibility. The ATO largely applies its framework to handle complaints, though it does not consistently document discussions with complainants to extend complaint due dates which has an impact on the accuracy of performance reporting. The ATO has also not consistently communicated taxpayer review rights to the complainant.

9. The ATO is largely effective at reporting on complaints, collecting complaint data to monitor incoming complaint volumes, categories of complaints, performance against service commitments and performance of key complaint topics. The data is used to generate internal reports based on the needs of individual business areas and bodies that meet to discuss complaint trends. Public reporting through the ATO Annual Report consists of the total number of complaints received and performance against the ATO service commitment targets. The ATO is able to determine which issue categories lead to increases in complaints but does not identify the root causes of these increases. Analysis of cross-product issues indicates that ‘timeliness’ is the largest complaint issue across many business lines, accounting for 56.5 per cent of all complaints from 2020–21 to 2023–24.

10. The ATO is largely effective in using a variety of sources including complaint data to identify business improvements to enhance both the complaint handling system and broader ATO processes and service delivery. It manages these through the Business Intelligence and Improvement register to iteratively improve its processes and service delivery. The ATO could strengthen its Business Intelligence and Improvements framework.

11. The ATO was largely effective in implementing the six IGTO recommendations made between 1 July 2020 and 30 July 2024 concerning the ATO’s management of complaints. The ATO has guidance to assist business lines developing implementation plans for recommendations. Implementation plans for the selected recommendations were largely consistent with this guidance, with the exception that the ATO’s template does not address measures of success or outcomes to be realised as required in ATO guidance. Recommendations are monitored through quarterly reporting to the ATO External Scrutineers Unit (ESU), the Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) and the IGTO. Reporting of selected recommendations was completed for all relevant quarters, though there were inconsistencies in reporting regarding revisions to the target implementation date of one recommendation. Three of the selected recommendations were assessed by the ANAO as implemented in full, two were largely implemented, and one was assessed as partly implemented. The ATO completed closure statements with attached evidence of implementation for all selected recommendations, though these were all endorsed after the reported closure dates and the ATO did not establish if the desired outcome of the recommendation had been achieved before closure of the recommendations. Evidence gathering and finalisation of the closure statements continued after the closure date for five of the six recommendations, with two also identifying ongoing work at the time of closure.

Supporting findings

Arrangements to support the effective handling of complaints

12. The ATO’s complaints management framework is largely aligned with the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Better Practice Complaint Handling Guide. Complaints are received, are categorised, and are sent to the relevant Business Service Line if they cannot be resolved at first point of contact. Resolution is through prioritisation of calls to the complaints hotline, the use of First Contact Resolution, and via complaint categorisation at the point of receipt. The ATO approach to determining efficiency focuses on timeliness and does not consider inputs and outputs. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.48)

13. The process to make a complaint to the ATO is clearly articulated on its website, and guidance documents provided to staff to explain the complaints process are clear. The complaints process is accessed primarily through online web form and telephone, and is largely compliant with the BPG. The ATO does not specifically survey complainants on the ATO’s complaint management process, however complainants who have had an identity-verified interaction with the ATO were eligible to be randomly sampled for the ATO’s broader monthly Client Experience Survey. The information on complaints obtained through this survey does not support meaningful analysis. The ATO relies on complainant feedback to identify and address accessibility issues, and does not proactively monitor and assess potential accessibility barriers. The ATO implements changes when issues are brought to its attention through this channel. (See paragraphs 2.49 to 2.61)

14. The ATO uses notes, attachments and templates in the Siebel work management system to record actions taken while resolving a complaint. The complaint capture template was consistently completed by ATO staff. The issues template was largely completed in line with ATO guidelines and use of this template increased from 2020–21 to 2023–24. Notes and attachments recorded in Siebel and analysed by the ANAO indicate the ATO actions complaints in accordance with its guidance. Regular ongoing contact was not consistently maintained with complainants in 2022–23 and 2023–24, and some complainants were not advised of their review rights when a complaint was closed. The ATO did not have a discussion with complainants before extending due dates in the majority of complaint cases. The extended due dates exceed the ATO’s service commitment to resolve complaints within 15 business days. (See paragraphs 2.62 to 2.86)

Reporting, process improvement, and review

15. The ATO generates internal reports based on the needs of individual business areas and bodies that meet to discuss complaints. Public reporting through the ATO Annual Report consists of the total number of complaints received and performance against the ATO service commitment targets. The ATO is able to determine which issue categories have led to increases in complaints, but does not identify the root causes of these increases. Analysis of cross-product issues indicates that ‘timeliness’ is the largest complaint issue across many business lines, accounting for 56.5 per cent of complaints from 2020–21 to 2023–24. (See paragraphs 3.2 to paragraph 3.42)

16. The ATO uses a variety of sources including complaint data to identify opportunities to improve its complaints management framework. The ATO manages changes to its complaints management framework manually through the Business Intelligence and Improvement register. The ATO does not undertake regular evaluation of its complaint handing processes. (See paragraphs 3.43 to 3.46)

17. The complaint data collected by the ATO is used to monitor incoming complaint volumes and categories, performance against service commitments and performance of key complaint topics. The ATO also improves non-complaint handling processes and service delivery through the Business Intelligence and Improvement register. There is an opportunity for the ATO to strengthen the Business Intelligence and Improvements framework. (See paragraphs 3.47 to 3.63)

Implementation of Inspector-General of Taxation recommendations regarding complaint handling

18. The ATO has guidance for business lines developing implementation plans to address recommendations from the Inspector-General of Taxation and Taxation Ombudsman (IGTO). The ATO External Scrutineers Unit coordinates this process. Implementation plans were developed for all selected recommendations and largely reflect ATO requirements. Implementation plans are not provided to the IGTO for feedback as required and the implementation plan template does not address measures of success or outcomes to be realised as required in ATO guidance. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.21)

19. The implementation of recommendations from the IGTO is primarily monitored through quarterly reporting. The ATO’s External Scrutineers Unit sources updates from Business Service Lines on the implementation of recommendations to produce quarterly reporting. These updates were often returned to ESU after their due date and lacked evidence of action taken. The progress of selected recommendations was reported to the IGTO and ATO Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) in all relevant quarters. The ATO classified four of the six closed recommendations as implemented by their original target date. There are inconsistencies in the reporting of revisions to the target implementation date of one recommendation to the ARC. These revisions were made after the previous target date had passed. (See paragraphs 4.22 to 4.49)

20. Three of the six closed recommendations were assessed by the ANAO as implemented in full, two were largely implemented, and one was assessed as partly implemented. The ATO completed all required closure statements, although endorsement was provided after the closure date for all recommendations, and evidence attached was not sufficient to provide assurance of implementation status without seeking documentation from additional sources. Evidence gathering and finalisation of the closure statements continued after the closure date for five recommendations, with two also identifying ongoing work. The ATO did not establish if the desired outcome of the recommendation had been achieved before closure of the recommendations. (See paragraphs 4.50 to 4.80)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.86

The Australian Taxation Office:

- conducts and documents any discussion with complainants before extending complaint due dates; and

- communicates and documents that review rights have been discussed with the complainant in accordance with its own guidance.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.40

The Australian Taxation Office:

- analyses the root causes of complaints, particularly where there has been a significant increase in volumes; and

- enhances its public reporting on complaint trends, causes, and outcomes in its Annual Report to better align with the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Better Practice Complaint Handling Guide to improve transparency to the Parliament.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.21

The Australian Taxation Office shares implementation plans for agreed recommendations with the Inspector-General of Taxation.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.78

The Australian Taxation Office gains sufficient assurance of implementation by closing recommendations only after providing:

- the required senior executive endorsement; and

- appropriate closure statement evidence, in accordance with its guidance.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to the ATO. The ATO’s summary response is reproduced below and its full response is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

The Australian Taxation Office (the ATO) welcomes the ANAO’s report and finding that the ATO is largely effective in managing complaints.

Whilst complaints represent a very small portion of our interactions with taxpayers, we understand the importance of complaints in helping us to continue to improve their experience.

We are proud of the work we do to deliver for the Australian community in a manner that meets Government and community expectations. We are pleased to see the ANAO has found the ATO has developed largely effective arrangements to handle complaints and that we monitor, report and process improvements effectively. We remain committed to understanding the systemic issues that may be driving trends through complaints as it enables us to continually improve how we operate.

The ATO agrees with the four recommendations in the report. Implementation of the recommendations and opportunities for improvement identified by the ANAO will help us further strengthen our complaints processes, and ensure we continue to effectively meet our commitments to taxpayers and the Australian Government.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

Auditor-General’s foreword

Emerging technologies including artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly a part of public services, with 56 public sector entities advising in the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)’s 2023–24 financial statements audits that they have adopted AI in their operations. AI can offer the promise of better services, enhanced productivity and efficiency — and also has the potential for increased risk and unintended consequences.

AI is an area of public interest for the Australian Parliament, with two inquiries underway during the time of undertaking this audit. The Select Committee on Adopting AI reported in November 2024.1 At the time of presenting this audit report to the Parliament, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit is conducting an inquiry into the use and governance of AI systems by public sector entities.2 The Australian Government has policies and frameworks for agencies on the adoption and use of AI that are referred to in this audit.

The growing use of AI also brings new challenges and opportunities in auditing. As a first step in addressing these, the ANAO has identified providing assurance on the governance of the use of new technology as a way of bringing transparency and accountability to the Parliament in this area of emerging public administration. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO), as an agency that uses technology extensively in its administration of the tax and superannuation systems, was chosen as the first agency in this new line of audit work. I acknowledge the ATO’s work on governance to support rapidly emerging technologies and cooperation in the undertaking of this audit. I also acknowledge the assistance of the Digital Transformation Agency through consultation on this audit.

The ANAO will continue to focus on governance of AI while it develops the capability to undertake more technical auditing of the AI tools and processes used in the public sector. Building this capability will require investment in knowledge, methodology and skills to enable the ANAO to test more deeply how AI tools operate in practice.

Like audit offices around the world, the ANAO will seek to examine how AI can improve the audit process itself, in a profession where human judgement and scepticism are foundations in auditing standards. This work will progress through our relationships within the international public sector audit community over coming years.

Dr Caralee McLiesh PSM

Auditor-General

Executive summary

1. Performance information is important for public sector accountability and transparency as it shows how taxpayers’ money has been spent and what this spending has achieved. The development and use of performance information is integral to an entity’s strategic planning, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation processes.

2. Annual performance statements are expected to present a clear, balanced and meaningful account of how well an entity has performed against the expectations it set out in its corporate plan. They are an important way of showing the Parliament and the public how effectively Commonwealth entities have used public resources to achieve desired outcomes.

The needs of the Parliament

3. Section 5 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) sets out the objects of the Act, which include requiring Commonwealth entities to provide meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public. The Replacement Explanatory Memorandum to the PGPA Bill 2013 stated that ‘The Parliament needs performance information that shows it how Commonwealth entities are performing.’1 The PGPA Act and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) outline requirements for the quality of performance information, and for performance monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

4. The Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) has a particular focus on improving the reporting of performance by entities. In September 2023, the JCPAA tabled its Report 499, Inquiry into the Annual Performance Statements 2021–22, stating:

As the old saying goes, ‘what is measured matters’, and how agencies assess and report on their performance impacts quite directly on what they value and do for the public. Performance reporting is also a key requirement of government entities to provide transparency and accountability to Parliament and the public.2

5. Without effective performance reporting, there is a risk that trust and confidence in government could be lost (see paragraphs 1.3 to 1.6).

Entities need meaningful performance information

6. Having access to performance information enables entities to understand what is working and what needs improvement, to make evidence-based decisions and promote better use of public resources. Meaningful performance information and reporting is essential to good management and the effective stewardship of public resources.

7. It is in the public interest for an entity to provide appropriate and meaningful information on the actual results it achieved and the impact of the programs and services it has delivered. Ultimately, performance information helps a Commonwealth entity to demonstrate accountability and transparency for its performance and achievements against its purposes and intended results (see paragraphs 1.7 to 1.13).

The 2023–24 performance statements audit program

8. In 2023–24, the ANAO conducted audits of annual performance statements of 14 Commonwealth entities. This is an increase from 10 entities audited in 2022–23.

9. Commonwealth entities continue to improve their strategic planning and performance reporting. There was general improvement across each of the five categories the ANAO considers when assessing the performance reporting maturity of entities: leadership and culture; governance; reporting and records; data and systems; and capability.

10. The ANAO’s performance statements audit program demonstrates that mandatory annual performance statements audits encourage entities to invest in the processes, systems and capability needed to develop, monitor and report high quality performance information (see paragraphs 1.18 to 1.27).

Audit conclusions and additional matters

11. Overall, the results from the 2023–24 performance statements audits are mixed. Nine of the 14 auditees received an auditor’s report with an unmodified conclusion.3 Five received a modified audit conclusion identifying material areas where users could not rely on the performance statements, but the effect was not pervasive to the performance statements as a whole.

12. The two broad reasons behind the modified audit conclusions were:

- completeness of performance information — the performance statements were not complete and did not present a full, balanced and accurate picture of the entity’s performance as important information had been omitted; and

- insufficient evidence — the ANAO was unable to obtain enough appropriate evidence to form a reasonable basis for the audit conclusion on the entity’s performance statements.

13. Where appropriate, an auditor’s report may separately include an Emphasis of Matter paragraph. An Emphasis of Matter paragraph draws a reader’s attention to a matter in the performance statements that, in the auditor’s judgement, is important for readers to consider when interpreting the performance statements. Eight of the 14 auditees received an auditor’s report containing an Emphasis of Matter paragraph. An Emphasis of Matter paragraph does not modify the auditor’s conclusion (see Appendix 1).

Audit findings

14. A total of 66 findings were reported to entities at the end of the final phase of the 2023–24 performance statements audits. These comprised 23 significant, 23 moderate and 20 minor findings.

15. The significant and moderate findings fall under five themes:

- Accuracy and reliability — entities could not provide appropriate evidence that the reported information is reliable, accurate and free from bias.

- Usefulness — performance measures were not relevant, clear, reliable or aligned to the entity’s purposes or key activities. Consequently, they may not present meaningful insights into the entity’s performance or form a basis to support entity decision making.

- Preparation — entity preparation processes and practices for performance statements were not effective, including timeliness, record keeping and availability of supporting documentation.

- Completeness — performance statements did not present a full, balanced and accurate picture of the entity’s performance, including all relevant data and contextual information.

- Data — inadequate assurance over the completeness, integrity and accuracy of data, reflecting a lack of controls over how data is managed across the data lifecycle, from data collection through to reporting.

16. These themes are generated from the ANAO’s analysis of the 2023–24 audit findings, and no theme is necessarily more significant than another (see paragraphs 2.12 to 2.17).

Measuring and assessing performance

17. The PGPA Rule requires entities to specify targets for each performance measure where it is reasonably practicable to set a target.4 Clear, measurable targets make it easier to track progress towards expected results and provide a benchmark for measuring and assessing performance.

18. Overall, the 14 entities audited in 2023–24 reported against 385 performance targets in their annual performance statements. Entities reported that 237 targets were achieved/met5, 24 were substantially achieved/met, 24 were partially achieved/met and 82 were not achieved/met.6 Eighteen performance targets had no definitive result.7

19. Assessing entity performance involves more than simply reporting how many performance targets were achieved. An entity’s performance analysis and narrative is important to properly inform stakeholder conclusions about the entity’s performance (see paragraphs 2.37 to 2.44).

Connection to broader government policy initiatives

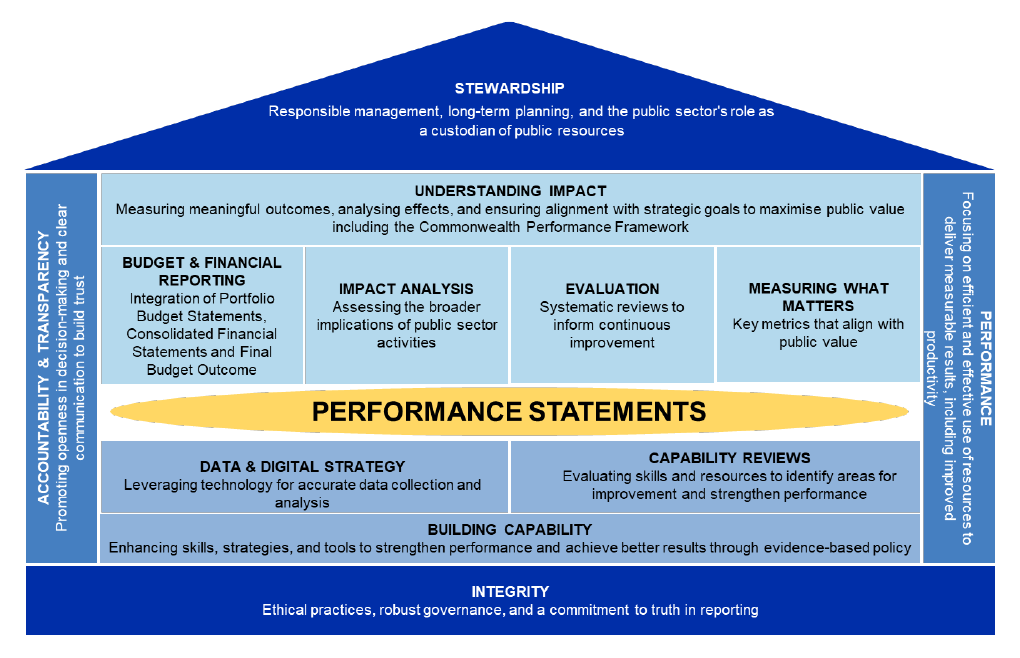

20. Performance statements audits touch many government policies and frameworks designed to enhance government efficiency, effectiveness and impact, and strengthen accountability and transparency. This is consistent with the drive to improve coherence across the Commonwealth Government’s legislative and policy frameworks that led to the PGPA Act being established.8 The relationship between performance statements audits and existing government policies and frameworks is illustrated in Figure S.1.

Figure S.1. Relationship of performance statements audits to government policies and frameworks

Source: ANAO analysis.

The future direction of annual performance statements audits

21. Public expectations and attitudes about public services are changing.9 Citizens not only want to be informed, but also to have a say between elections about choices affecting their community10 and be involved in the decision-making process, characterised by, among other things, citizen-centric and place-based approaches that involve citizens and communities in policy design and implementation.11 There is increasing pressure on Commonwealth entities from the Parliament and citizens demanding more responsible and accountable spending of public revenues and improved transparency in the reporting of results and outcomes.

22. A specific challenge for the ANAO is to ensure that performance statements audits influence entities to embrace performance reporting and shift away from a compliance approach with a focus on complying with minimum reporting requirements or meeting the minimum standard they think will satisfy the auditor.12 A compliance approach misses the opportunity to use performance information to learn from experience and improve the delivery of government policies, programs and services.

23. Performance statements audits reflect that for many entities there is not a clear link between internal business plans and the entity’s corporate plan. There can be a misalignment between the information used for day-to-day management and governance of an entity and performance information presented in annual performance statements. Periodic monitoring of performance measures is also not an embedded practice in all Commonwealth entities. These observations indicate that some entities are reporting measures in their performance statements that may not represent the highest value metrics for running the business or for measuring and assessing the entity’s performance (see paragraphs 4.32 to 4.35).

Developments in the ANAO’s audit approach

24. Working with audited entities, the ANAO has progressively sought to strengthen sector understanding of the Commonwealth Performance Framework. This includes a focus on helping entities to apply general principles and guidance to their own circumstances and how entities can make incremental improvements to their performance reporting over time. For example:

- in 2021–22, the ANAO gave prominence to ensuring entities understood and complied with the technical requirements of the PGPA Act and the PGPA Rule;

- in 2022–23, there was an increased focus on supporting entities to establish materiality policies that help determine which performance information is significant enough to be reported in performance statements and to develop entity-wide performance frameworks; and

- in 2023–24, there was an increased focus on assessing the completeness of entity purposes, key activities and performance measures and whether the performance statements present fairly the performance of the entity (see paragraphs 4.36 to 4.38).

Appropriate and meaningful

25. For annual performance statements to achieve the objects of the PGPA Act, they must present performance information that is appropriate (accountable, reliable and aligned with an entity’s purposes and key activities) and meaningful (providing useful insights and analysis of results). They also need to be accessible (readily available and understandable).

26. For the 2024–25 audit program and beyond, the ANAO will continue to encourage Commonwealth entities to not only focus on technical matters (like selecting measures of output, efficiency and effectiveness and presenting numbers and data), but on how to best tell their performance story. This could include analysis and narrative in annual performance statements that explains the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind the reported results and providing future plans and initiatives aligned to meeting expectations set out in the corporate plan.13

27. It is difficult to demonstrate effective stewardship of public resources without good performance information and reporting. Appropriate and meaningful performance information can show that the entity is thinking beyond the short-term. It can show that the entity is committed to long-term responsible use and management of public resources and effectively achieving results to create long lasting impacts for citizens (see paragraphs 4.39 to 4.45).

Linking financial and performance information

28. The ‘Independent Review into the operation of the PGPA Act’14 noted that there would be merit in better linking performance and financial results, so that there is a clear line of sight between an entity’s strategies and performance and its financial results.15

29. Improving links between financial and non-financial performance information is necessary for measuring and assessing public sector productivity. As a minimum, entities need to understand both the efficiency and effectiveness of how taxpayers’ funds are used if they are to deliver sustainable, value-for-money programs and services. There is currently limited reporting by entities of efficiency (inputs over outputs) and even less reporting of both efficiency and effectiveness for individual key activities.

30. Where entities can demonstrate that more is produced to the same or better quality using fewer resources, this reflects improved productivity.

31. The ANAO will seek to work with the Department of Finance and entities to identify opportunities for annual performance statements to better link information on entity strategies and performance to their financial results (see paragraphs 4.46 to 4.51).

Cross entity measures and reporting