Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Take our Insights reader feedback survey

Help shape the future of ANAO Insights by taking our reader feedback survey.

Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The aim of Audit Lessons is to communicate lessons from our audit work and to make it easier for people working within the Australian public sector to apply those lessons.

This edition is targeted at those responsible for implementing internal policies and controls on the receipt of gifts, benefits and hospitality in Australian Government entities.

Introduction

In the course of their duties, Australian Public Service (APS) employees may interact with many people and organisations, and may be offered gifts, benefits or hospitality as part of these interactions. These offers could range from small token items to larger more expensive gifts —such as an invitation to a gala dinner or travel. The acceptance of these offers can create conflicts of interest and pose risks to public confidence in entities and the APS more broadly, particularly in the public’s expectations of integrity, accountability, independence, transparency and professionalism.

The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires Australian Government officials to not improperly use their position to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit or advantage for themselves or any other person.The Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act) requires that APS employees and agency heads uphold the APS Valuesand Code of Conduct.The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) publishes guidance on gifts and benefits to assist APS officials with meeting their obligations.

APSC guidance

|

Guidance for Agency Heads — Gifts and Benefits |

|

|

APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice |

|

|

Declaration of interests |

|

Gifts and benefits management in the APS

94% of Australian Government agency heads publicly disclosed accepted gifts and benefits

The ANAO reviewed the published gifts and benefits registers of 115 Australian Government entities with staff employed under the PS Act. A key APSC requirement is that agency heads publish on their entity website a register of gifts and benefits valued over $100 that they accept. The ANAO examined the websites of 115 Australian Government entities as at September 2024 and found that 94 per cent of agency heads had published a register of gifts and benefits they had accepted.Most of these public registers also included gifts and benefits accepted by other agency staff.

The following table shows the alignment of public registers with other APSC requirements.

Percentage of agency heads meeting APSC requirements on gifts and benefits disclosure

|

APSC requirements for agency head disclosures |

Percentage of entities that met this requirementa |

|

Register published on a quarterly basis |

83% |

|

Reported for most recent quarter |

64%b |

|

Threshold for reporting set at $100 or lower (excluding GST) |

90% |

|

A link to the agency head gifts and benefits register provided to the APSC for publication on the APSC website |

93% |

Note a: The percentages are derived from the 115 Australian Government entities that the ANAO reviewed.

Note b: The ANAO reviewed websites at least 57 days after the end of the fourth quarter for 2023–24. The APSC policy requires reporting within 31 days.

Source: ANAO analysis of Australian Public Service Commission, Guidance for Agency Heads - Gifts and Benefits, 2021, available from https://www.apsc.gov.au/working-aps/integrity/integrity-resources/guidance-agency-heads-gifts-and-benefits [accessed 6 September 2024]; Australian Public Service Commission, Agency Heads Gifts and Benefits registers, 2024, Available from https://www.apsc.gov.au/agency-head-gifts-and-benefits-registers [accessed 5 September 2024]; and 115 Australian Government entities’ websites.

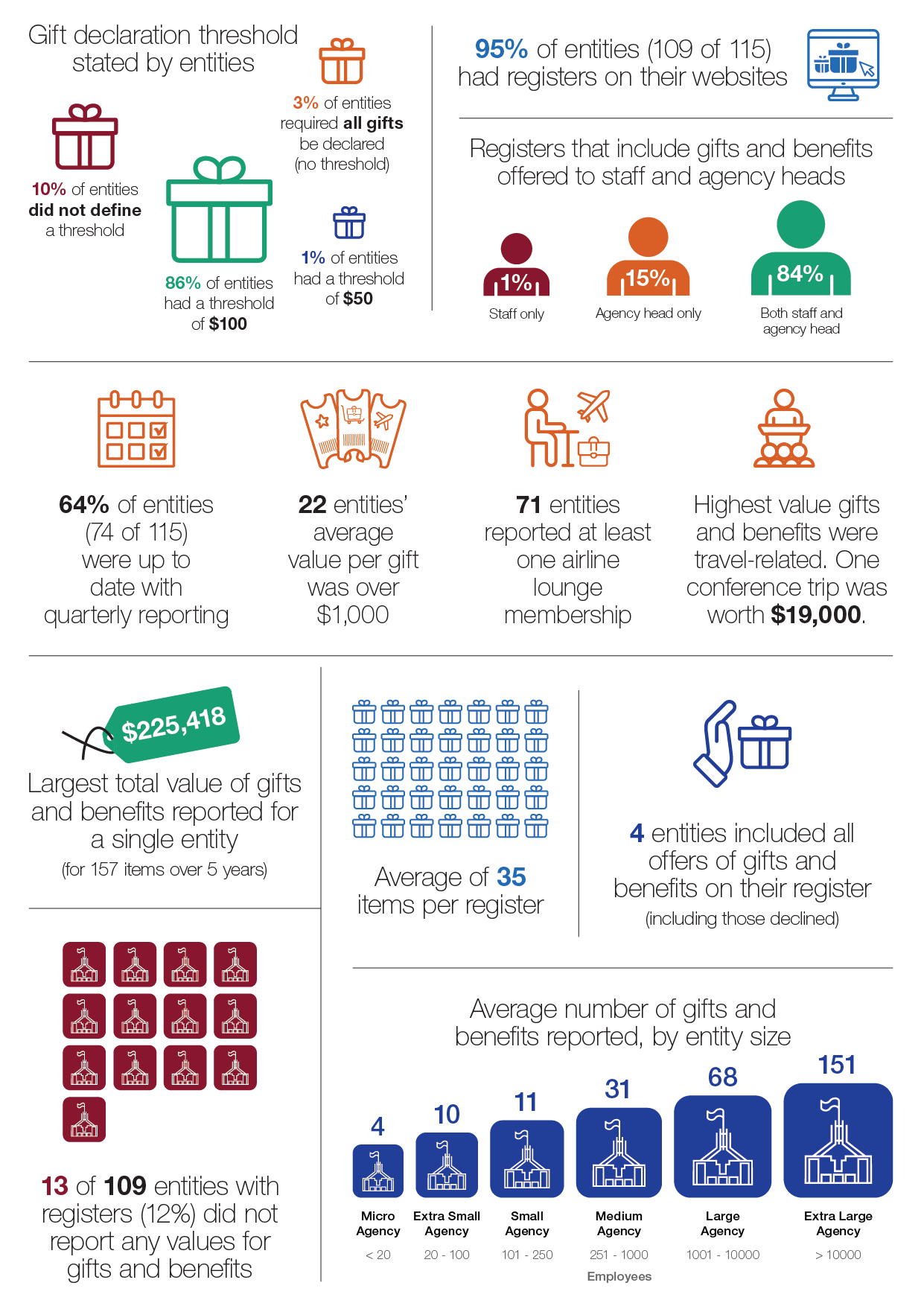

The APSC requirement for agency heads to report gifts and benefits on a public quarterly register came into force in October 2019. The following snapshot outlines all reporting on gifts and benefits publicly available on websites for 115 Australian Government entities.

Snapshot of gifts and benefits management in the APS

Source: ANAO analysis (as at week of 26 August 2024) of gifts and benefits management for 115 Commonwealth entities with staff employed under the PS Act.

Audit Lessons

This edition of Audit Lessons sets out seven lessons aimed at improving Australian Government entities’ compliance with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements.

1. Establishing a guiding principle for officials to generally avoid the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality helps promote a culture of integrity.

2. Establishing preventative and detective controls helps manage corruption risks associated with gifts and benefits.

3. Internal policies on gifts, benefits and hospitality should be clear and specific.

4. Guidance could highlight entity activities that are at a heightened risk from gifts, benefits and hospitality.

5. Controls can help ensure inappropriate personal benefits are not derived from official travel.

6. Reporting all gifts and benefits — not just those accepted — can help identify risks.

7. Accurate valuation of gifts, benefits and hospitality increases transparency.

These lessons are based on insights from ANAO performance audits over the past two years, including two performance audits focused on compliance with gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements in the Department of the Treasury (the Treasury) and Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA).

The further reading section provides links to: additional Insights products; and Department of Finance (Finance) and APSC resources.

Lesson 1: Establishing a guiding principle for officials to generally avoid the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality helps promote a culture of integrity

Section 27 of the PGPA Act states that an official must not improperly use their position to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit to themselves or another person. The receiving of gifts, benefits and hospitality can create the perception that an official is subject to inappropriate external influence. Finance’s model Accountable Authority Instructions indicate that Commonwealth entities should have the policy: ‘Generally, officials cannot accept gifts or benefits in the course of their work’. A clear guiding principle for officials to generally avoid the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality, regardless of their value, can help remove doubt or misunderstanding, set an appropriate tone from the top and promote a culture of integrity.

An entity could establish in its policies that the default position is that officials do not accept gifts, benefits or hospitality of any value. The policy could also clearly outline the situations where it may be acceptable to accept a gift, such as where a visiting dignitary offers a cultural gift to an official (which they could accept on behalf of the entity). This policy could also be communicated to suppliers, contractors, regulated entities and individuals, and other parties — to discourage gifts of any size being offered to Commonwealth officials.

Case study 1. AOFM’s management of gifts, benefits and hospitality

In 2024, the ANAO examined the effectiveness of the Australian Office of Financial Management’s (AOFM’s) management of the Australian Government’s debt, which included an assessment of the AOFM’s arrangements for managing gifts, benefits and hospitality.

Between 1 January 2020 and 30 June 2023, the AOFM recorded 146 entries on an internal gifts and benefits register: 139 were recorded as accepted; four were recorded as declined; and three entries had no action recorded.

The ANAO recommended that the AOFM review whether a guiding principle, consistent with other APS agencies, that officials are to generally avoid the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality is appropriate for the organisation.

Lesson 2: Establishing preventative and detective controls helps manage corruption risks associated with gifts and benefits

Risks associated with gifts, benefits and hospitality include fraud and corruption risks. Section 16 of the PGPA Act requires accountable authorities of Commonwealth entities to establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight, management and internal control for the entity. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy supports this PGPA Act requirement and can assist entities with establishing controls to help manage risks associated with gifts and benefits.

Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 — The Fraud and Corruption Rule — sets out the minimum standards for accountable authorities of PGPA Act entities in relation to managing the risk of fraud and corruption, including those associated with the acceptance of gifts and benefits. The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policy supports these requirements.

Element 1 of the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policy requires entities to conduct regular assessments of fraud and corruption risks. These risk assessments help entities identify, understand and document their exposure to fraud and corruption, the associated risks and their existing control arrangements.

Elements 5 and 6 of the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policy require accountable authorities to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and respond to fraud and corruption relating to the entity, including by: ensuring that the entity has appropriate mechanisms for preventing and detecting fraud and corruption.

Preventative controls for managing gifts and benefits could include:

- establishing a clear and simple principle that gifts and benefits of any value should not be accepted (with exceptions clearly defined) and communicating this policy to suppliers, contractors, regulated entities and individuals, and other parties (see Lesson 1);

- creating clear policies, guidance and training on gifts and benefits (which includes case studies and examples) that help staff identify what is a gift, decide whether to accept a gift, and understand their obligations and responsibilities (see Lesson 3);

- highlighting in guidance and training: the link between the management of gifts and benefits and the management of actual and perceived conflicts of interest; what is likely to be offered as a gift; and what could create a particular risk of conflicted interests given the unique business of the entity (see Lesson 4); and

- ensuring that officials understand that airline lounge memberships, status points and similar travel ‘perks’ are gifts and benefits (see Lesson 5).

Detective controls for managing gifts and benefits could include:

- maintaining a gifts and benefits register for all staff (not just the agency head);

- requiring staff to report all offered gifts and benefits on the register, regardless of value or whether they were accepted or declined (see Lesson 6);

- providing clear guidance on the valuation of gifts and benefits for reporting purposes (see Lesson 7);

- regular executive review of the gifts and benefits register; and

- confidential tip-off reporting channels for officials, third-party service providers and members of the public.

Entities should undertake regular management reviews and audits of the effectiveness of preventative and detective controls.

Case study 2. Treasury’s management of risks associated with gifts, benefits and hospitality

In 2024, the ANAO examined Treasury’s management of risks associated with gifts, benefits and hospitality and found:

Lesson 3: Internal policies on gifts, benefits and hospitality should be clear and specific

An internal policy on gifts, benefits and hospitality is an important element of a robust control environment and supports ethical conduct. The effective implementation of such a policy requires strong cultural settings within the entity, including the example set by senior leadership (‘tone at the top’), and prompt and accurate disclosures by entity personnel.

Entities should clearly and specifically define official’s responsibilities in relation to gifts, benefits and hospitality in internal policy.

Finance outlines potential internal policies on gifts and benefits in its Resource Management Guide (RMG) 206: Model Accountable Authority Instructions – Non-corporate Commonwealth entities. These include the following.

- Generally, officials cannot accept gifts or benefits in the course of their work.

- Gifts provided to officials in the course of their work immediately become entity property when received, unless entity policy indicates otherwise.

- Officials must not:

- ask for, or encourage, the giving of gifts;

- accept a gift of money (except in exceptional circumstances); or

- accept a gift or benefit that influences, or could reasonably be perceived to influence, a decision or action on a particular matter.

- Officials must have regard to the general duties of officials in deciding whether to accept a gift. If an official decides to accept a gift or benefit, the decision must be defensible and able to withstand public scrutiny.

RMG 206 outlines other additional instructions that could be covered in internal policy, such as:

- the entity’s policy for receiving gifts and benefits (including clarifying in what circumstances accepting a gift or benefit may be appropriate), hospitality or sponsorship;

- a requirement to inform an appropriate official when offered gifts or benefits;

- a requirement to maintain a register of gifts and benefits accepted (including estimated value);

- whether gifts of an inconsequential nature may be retained, or purchased from the entity, by the official (including relevant thresholds); and

- whether gifts or benefits can be received in relation to tenders or contract negotiations.

Policies could also:

- define the timeframes for reporting the offer of gifts, benefits and hospitality and the surrendering of gifts or benefits to the entity;

- include requirements for officials to record their assessment of whether acceptance of a gift or benefits could give rise to an actual or perceived conflict of interest and why;

- ensure the register includes all gifts, benefits and hospitality offered — not just those accepted; and

- establish that the register will include all officials (not just agency heads) and be published on the entity’s website for transparency and accountability.

Case study 3. Treasury’s internal policies on gifts and benefits

The ANAO’s examination of Treasury’s internal policies on gifts, benefits and hospitality found:

- a definition of gifts and benefits, with examples;

- the related duties of officials under the PGPA Act and APS Code of Conduct;

- processes for declaring and seeking approval when accepting gifts, benefits or hospitality; and

- considerations for officials when accepting gifts, benefits and hospitality.

Lesson 4: Guidance could highlight entity activities that are at a heightened risk from gifts, benefits and hospitality

Certain government activities — such as procurement or regulation — are at a heightened risk of conflict of interest for officials. The APSC states in its publication, APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice, that the appearance of a conflict can be just as damaging to public confidence as a conflict that gives rise to a concern based on objective facts. The acceptance of gifts, benefits or hospitality creates the risk of an actual, potential or perceived conflict of interest — at the time the gift was offered or during later decision-making activities.

Entities could establish procurement policies, guidance, training and templates arrangements that ensure risks posed by gifts, benefits and hospitality are managed. This could involve written activity-based declarations of interest for officials involved in procurement and regulatory activities, in addition to general declarations of gifts, benefits and hospitability required under the entity’s policy.

Procurement

The Commonwealth Procurement Rules state that officials undertaking procurement must act ethically throughout a procurement and that ethical behaviour includes not accepting inappropriate gifts or hospitality. APSC guidance states ‘It is not usually appropriate to accept a gift or benefit from a person or company if they are involved in a tender process with the agency, either for the procurement of goods and services or sale of assets’. As it is not clear in what circumstances a gift, benefit or hospitality would be ‘appropriate’ during a procurement, it would be better to err on the side of caution and decline all gifts, benefits and hospitality during a procurement process.

Regulation

The PGPA Act and the APS Code of Conduct require officials to not improperly use their position to gain, or seek to gain, a benefit or advantage for themselves or any other person.Regulators need to be particularly aware of risks of actual or perceived conflicts of interest and ‘regulatory capture’, which could arise from accepting gifts, benefits or hospitality from a regulated individual or business.

Case study 4. Managing conflicts of interest as a regulator - Australian Financial Security Authority

In 2024, the ANAO examined the Australian Financial Security Authority’s (AFSA) management of conflicts of interest, including arrangements for assessing conflict of interest risks and providing guidance to staff on how to comply with conflict of interest requirements. The ANAO found the following.

Lesson 5: Controls can help ensure inappropriate personal benefits are not derived from official travel

Travel-related benefits may include airline lounge membership, the earning of loyalty reward points such as airline frequent flyer points, and status credits. According to APSC guidance, loyalty reward points such as frequent flyer points ceased to accrue with the introduction of the Whole of Australian Government Travel Arrangements on 1 July 2010.

In accordance with Finance’s guidance on travel arrangements:

Promotional offers that present Australian Government travellers options to accept bonus Status Credits or bonus Frequent Flyer Points should not be accepted. [Australian Government] travellers should not obtain a personal benefit from Commonwealth funded activities, particularly as the acceptance of such an offer may influence the choice of airline for future official air travel.

The acceptance of bonus status credits or loyalty reward points from Australian Government funded activity is not permitted as it could incentivise officials to preference specific airlines and limit an entity’s ability to demonstrate that it has booked the cheapest practical airfare and achieved value for money.

Where an official accepts a gift, such as an airline lounge membership or a flight upgrade, this should be reported on the entity’s gifts and benefits register.

Finance’s Resource Management Guides (RMGs) 404 and 405 on domestic and international travel policy state that when undertaking official domestic or international air travel, officials must select ‘the lowest fare available at the time the travel is booked on a regular service (not a charter flight), that suits the practical business needs of the traveller’.

Entities can implement clearer guidance and controls to ensure staff are making travel decisions based on value for money and not to derive a personal benefit. Where an official selects a fare that is not the ‘best fare’, there should be a justification that is reviewed and either approved or rejected by their supervisor. Further, there should be a control to ensure the official has not accrued loyalty reward points or bonus status credits.

Lesson 6: Reporting all gifts and benefits — not just those accepted — can help identify risks

APSC guidance establishes the requirement that agency heads are to publish a register of gifts, benefits and hospitality that have been accepted and are above $100. This disclosure includes gifts, benefits and hospitality accepted by agency heads’ immediate families and dependants where it is related to the official duties of the agency head. APS Values and Code of Conduct in Practice provides that ‘agencies may require the employees to disclose offers which were not accepted, for example, where the offer could be perceived as a bribe’.

Disclosing offers of gifts, benefits and hospitality that were declined, in addition to those that were accepted is considered better practice as it assists with:

- promoting transparency and accountability;

- establishing a culture where gifts, benefits and hospitality are generally declined;

- discouraging external stakeholders from offering gifts, benefits or hospitality; and

- providing insight into avenues where influence may be being sought and therefore help manage potential corruption risks across the organisation.

Case study 5. ACMA’s policy for reporting on gifts, benefits and hospitality

As a regulator, ACMA has risks associated with potential regulatory capture. The ANAO found that ACMA’s internal guidance requires officials to estimate the value of any hospitality, gift or benefit received or declined, and record it. ACMA’s guidance does not require the publication of declined offers.

ANAO analysis of events attended by ACMA Senior Executive Service (SES) officers and members identified 19 gifts or hospitality events received by officials that were not disclosed on ACMA’s and eSafety Commissioner’s official hospitality, gifts and benefits registers. Based on the 131 instances of gifts, benefits and hospitality declared by ACMA and eSafety Commissioner, the 19 undeclared instances represented a 13 per cent non-compliance rate.

The ANAO outlined an opportunity for improvement that: ACMA stipulate in its policy that offers that have not been accepted are to be included in ACMA’s gifts, benefits and hospitality register so that the public is informed of ACMA’s interactions with its stakeholders.

Lesson 7: Accurate valuation of gifts, benefits and hospitality increases transparency

Valuation of gifts, benefits and hospitality needs to be accurate, transparent and defensible. Entities should provide staff with clear guidance on how to establish a value. Lack of guidance on how to quantify values increases the risk that values may be under-reported and/or avoid the requirement for delegate approval.

Values attributed to declared gifts, benefits or hospitality should reflect the costs that would have been expended if the organisation had acquired it directly. Where the actual cost is unknown, the use of a publicly available price of a comparable product is appropriate. According to APSC guidance, the value of an official gift is to be assessed on the basis of the:

- wholesale value in the country of origin of the donor of the gift and converted to Australian dollars at the current exchange rate; or

- current market value of the gift in Australia.

Entities could also avoid risks of gifts and benefits being undervalued and consequently not reported, by requiring staff to report all gifts, regardless of their value.

Case study 6. ACMA’s valuation of gifts, benefits and hospitality

The ANAO found that ACMA’s policy framework does not contain provisions for how the value of gifts and benefits should be quantified. ANAO analysis of 131 items that had been accepted by officials for the reporting period 1 July 2021 to 30 September 2023 found that it included instances where the declared value was below market value.

For example, for a charity fundraising event gifted by the Australian Football League, the event’s tickets were advertised at $1,000 per person. The internal declaration form initially declared these items at $1,000 each. On review of the declaration form, the Head of Business Operations within ACMA’s Office of the eSafety Commissioner discussed the event with the declaring official and amended the declared value of the lunch to $150 each. The item was reported in ACMA’s register at the revised value of $150 each.

Further reading

ANAO links

- Board Governance | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Fraud Control Arrangements | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Management of Conflicts of Interest in Procurement Activity and Grants Programs | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Probity Management: Lessons from Audits of Financial Regulators | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Procurement and Contract Management | Insights: Audit Lessons

- Risk Management | Insights: Audit Lessons

External links

- Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) - (RMG 206) | Department of Finance

- APS Values and Code of Conduct in practice | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework 2024 | Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre (counterfraud.gov.au)

- Commonwealth Risk Management Policy | Department of Finance

- Declaration of interests | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- Guidance for Agency Heads - Gifts and Benefits | Australian Public Service Commission (apsc.gov.au)

- Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud and corruption (RMG 201) | Department of Finance

- What is corrupt conduct | National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC)