Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Compliance with Corporate Credit Card Requirements in the Federal Court of Australia

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit is one of a series of credit card audits to be tabled by the ANAO in 2023–24.

- The misuse of Australian Government credit cards, whether deliberate or not, has the potential for financial losses and reputational damage to government entities.

- The robustness of controls to detect and prevent misuse of credit cards and action taken on non compliance are indicative of an entity’s culture and integrity.

- Previous ANAO audits have identified issues in other entities relating to positional authority in approvals of credit card transactions and ineffective controls in the management of the use of credit cards.

Key facts

- The FCA used 547 cards in the 2022–23 financial year: 83 credit cards and 464 CabCharge cards.

- The FCA spent $1,169,013 in the 2022–23 financial year across its credit and CabCharge cards.

What did we find?

- The Federal Court of Australia’s (FCA’s) management of the use of corporate credit cards has been partly effective.

- The FCA had considered credit card risks and identified relevant controls. Its policies and procedures included core requirements but lacked detail in key areas. No structured training and education was in place. While monitoring and reporting arrangements were in place, detailed reporting on non-compliance was not provided to executive leadership.

- There were weaknesses in the FCA’s implementation of preventive and detective controls, which heighten the risk that instances of credit card non-compliance could go undetected. Where misuse was detected, it was dealt with using established escalation processes and mechanisms.

What did we recommend?

- There were six recommendations to the FCA relating to improving preventive and detective controls for credit cards.

- The FCA agreed to all recommendations.

5.7%

of the FCA’s workforce used a corporate credit card between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

8

instances of external credit card fraud and inadvertent personal misuse were identified and recovered by the FCA between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

4138

domestic CabCharge trips were undertaken by employees of the Federal Court of Australia between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide 206 defines a ‘corporate credit card’ as a credit card used by Commonwealth entities to obtain goods and services on credit.1 Credit cards are used by Commonwealth entities to support timely and efficient payment of suppliers for goods and services.2 For the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), credit cards include charge cards (such as VISA, Mastercard, Diners and American Express cards) and vendor cards (such as travel cards and fuel cards).

2. The Federal Court of Australia (FCA) uses corporate credit cards for official purchases under $10,000 and CabCharge cards for domestic taxi fares. For 2021–22 and 2022–23, the FCA’s total credit card expenditure was approximately $2.1 million, comprising 13,393 transactions. Credit card expenditure represented 16 per cent of the FCA’s supplier expenses across the two years.3

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The misuse of corporate credit cards, whether deliberate or not, has the potential for financial losses and reputational damage to government entities and the Australian Public Service. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) states that:

establishing a pro-integrity culture at the institutional level means setting a culture that values, acknowledges and champions proactively doing the right thing, rather than purely a compliance-driven approach which focuses exclusively on avoidance of wrongdoing.4

4. In describing the role of Senior Executive Service (SES) officers, the APSC states that the SES ‘set the tone for workplace culture and expectations’, they ‘are viewed as role models of integrity’ and ‘are expected to foster a culture that makes it safe and straightforward for employees to do the right thing’.5 The New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption identifies organisational culture and expectations as a key element in preventing corruption and states:

[T]he way that an agency’s senior executives, middle managers and supervisors behave directly influences the conduct of staff by conveying expectations of how staff ought to act. This is something that affects an agency’s culture.6

5. Deliberate misuse of a corporate credit card is fraud. The National Anti-Corruption Commission’s Integrity Outlook 2022/23 identifies fraud, which includes the misuse of credit cards, as a key corruption and integrity vulnerability.7 The Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile indicates that credit cards are a common source of internal fraud risk. Previous audits have identified issues in other entities relating to positional authority for approving credit card transactions8 and ineffective controls to manage the use of credit cards.9 This audit was conducted to provide the Parliament with assurance that the FCA is effectively managing corporate credit cards in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

6. This audit is one of a series of compliance with credit card requirements that apply a standard methodology. The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2023–24 compliance with credit card requirements series are the:

- Federal Court of Australia (FCA);

- Australian Research Council;

- National Disability Insurance Agency; and

- Productivity Commission.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the FCA’s management of the use of corporate credit cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO examined:

- whether the FCA has effective arrangements in place to manage the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards; and

- whether the FCA has implemented effective controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures.

Conclusion

9. The FCA’s management of the use of corporate credit cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and entity requirements has been partly effective, as there were weaknesses in its implementation of preventive and detective controls.

10. The FCA’s arrangements for managing the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards were largely effective. The FCA had considered risks associated with the use of corporate credit cards within its overarching risk framework and identified relevant controls. Policies and procedures included core requirements but lacked detail on eligibility criteria for issuing cards and requirements for using CabCharge cards. No structured training and education arrangements were in place to promote compliance with policy and procedural requirements. While arrangements had been established for monitoring and reporting on credit card issue, return and use, detailed reporting was not provided to the FCA’s executive management on credit card non-compliance. The FCA did not respond to Parliamentary questions on notice with accurate reporting on credit card use.

11. The FCA’s implementation of controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures was partly effective. There were weaknesses in its preventive controls relating to assessing and recording business needs for issuing credit cards and documenting pre-approval and rationales for purchases. The implementation of detective controls was partly effective, with no managerial review process for CabCharge card transactions and no use of data analytics across credit card transactions to detect potential instances of purchase splitting. These deficiencies heighten the risk that instances of credit card non-compliance could go undetected. Where misuse was detected, the FCA used established escalation processes and mechanisms to deal with non-compliant transactions.

Supporting findings

Arrangements for managing corporate credit cards

12. The FCA had considered risks associated with the use of corporate credit cards within its overarching risk framework and identified relevant controls. Its enterprise-level fraud risk register identified misuse or unauthorised use of corporate credit cards as a low risk. The register was last updated in June 2021 and the FCA had not recently tested the effectiveness of its credit card controls. Risk monitoring and reporting arrangements were undergoing change and yet to be formalised. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.21)

13. The FCA’s policies and procedures for the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards included core requirements, which were covered within the FCA’s accountable authority instructions and other policies. Eligibility requirements for issuing credit cards could be improved by defining business need criteria for card issuance in policies and procedures. More guidance could be provided on using and acquitting CabCharge cards. (See paragraphs 2.22 to 2.44)

14. While the FCA had published relevant policies and procedures on its intranet, it did not provide structured training and education to promote compliance with corporate credit card policy and procedural requirements. Support was provided by the FCA’s finance team for cardholders and managers upon card issuance and when requested. (See paragraphs 2.45 to 2.48)

15. The FCA had arrangements in place for monitoring and reporting on the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards. Credit card usage was monitored by the FCA’s finance team. Detailed reporting on credit card non-compliance was not provided to the FCA’s executive management, diminishing its understanding of fraud, risk and integrity implications arising from non-compliance. While FCA reported on credit card usage and expenditure when requested by Parliament, there were errors in its reporting. (See paragraphs 2.49 to 2.58)

Controls and processes for corporate credit cards

16. The FCA’s implementation of preventive controls did not include a systematic approach to assessing and recording that staff have valid business needs prior to issuing credit cards. There were control weaknesses in documenting pre-approvals and rationales for entertainment purchases and purchases covered by whole-of-government arrangements. There were also control weaknesses in documenting pre-approvals for CabCharge card transactions that fell outside approved domestic travel budgets. The card returns process placed a reliance on the relevant manager both identifying that the employee had a card to return and ensuring the card was either returned to the finance team or destroyed. (See paragraphs 3.4 to 3.35)

17. The FCA has implemented detective controls to acquit, verify and review transactions. The monthly acquittal process for corporate credit card transactions could be improved by ensuring CabCharge card transactions are acquitted by cardholders and signed off by responsible managers. The FCA could make greater use of data analytics to identify potential non-compliance, such as purchase that have been split to avoid transaction limits. (See paragraphs 3.37 to 3.58)

18. Deficiencies in the FCA’s credit card control framework heighten the risk that instances of credit card non-compliance could go undetected. The FCA detected four instances of non-compliance in 2022–23 that triggered the escalation protocols in its credit card policy. This has led to the recovery of funds from cardholders and merchants where accidental misuse and fraudulent transactions were identified. (See paragraphs 3.60 to 3.63)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.26

The Federal Court of Australia update its policies and procedures for issuing credit cards and CabCharge cards to provide guidance on eligibility criteria and accurately reflect current processes.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.38

The Federal Court of Australia update its policies and procedures for credit card use to provide additional guidance on receipt and approval requirements for CabCharge cards.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.19

The Federal Court of Australia establish a process to confirm evidence of pre-approval by the designated official and the rationale for spending are documented when acquitting credit card transactions for official hospitality and entertainment purchases and instances where whole-of-government arrangements are not being utilised.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.28

The Federal Court of Australia establish a process to ensure evidence of pre-approval and receipts are recorded for all CabCharge card transactions.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.45

The Federal Court of Australia establish a process to ensure CabCharge card transactions are acquitted by cardholders and approved by their responsible managers on a monthly basis.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.57

The Federal Court of Australia formalise and document its process for conducting periodic analysis of credit card transactions targeting key areas of risk, including purchase splitting, and update its policies and procedures to prohibit purchase splitting.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

19. The proposed audit report was provided to the FCA. The FCA’s summary response is reproduced below. Its full response is included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of the audit are listed at Appendix 2.

The Federal Court of Australia (the Court) acknowledges and agrees the recommendations of the Australian National Audit Office and accepts the identified areas where the Court has opportunity to improve.

The Court will continue to focus on strengthening the current processes and guidance that are necessary to reduce risks associated with the potential inappropriate use of credit cards.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

20. This audit is part of a series of audits that apply a standard methodology to corporate credit card management in Commonwealth entities. The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2023–24 corporate credit card management series are the:

- Federal Court of Australia;

- Australian Research Council;

- National Disability Insurance Agency; and

- Productivity Commission.

21. Key messages from the ANAO’s series of credit card management audits will be outlined in an Insights product available on the ANAO website.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian Government entities use credit cards to support timely and efficient payment to suppliers of goods and services. ‘Corporate credit cards’ include charge cards (such as Visa, Mastercard, Diners Club and American Express cards) and vendor cards (such as travel and fuel cards).10 Other forms of credit used by Australian Government entities include credit vouchers (such as CabCharge e-tickets).

Australian Government framework for using credit cards

1.2 The Commonwealth Resource Management Framework governs how Australian Government entities use and manage public resources. The cornerstone of the framework is the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

1.3 Under section 56 of the PGPA Act, the Minister for Finance has delegated the power to enter into a limited range of borrowing agreements to the accountable authorities11 of non-corporate Commonwealth entities.12 This includes the power to enter into an agreement for the issue and use of credit cards, providing money borrowed is repaid within 90 days.

1.4 The PGPA Act sets out general duties of accountable authorities and officials of Australian Government entities. Relevant to credit card use, officials have a duty not to improperly use their positions to gain or seek to gain a benefit or advantage for themselves or others, or to cause detriment to the Commonwealth, entity, or others.13 Further, the duties of an accountable authority include:

- governing an entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources14; and

- establishing and maintaining appropriate systems of risk oversight and management and internal control, including measures to ensure officials comply with the finance law.15

1.5 Under subsection 20A(1) of the PGPA Act, an accountable authority may give instructions (referred to as accountable authority instructions) to entity officials about any matter relating to the finance law. The Department of Finance has published model accountable authority instructions, which include model instructions for the use of credit cards (see Box 1) as well as suggestions for additional instructions on credit card use.16

|

Box 1: Model accountable authority instructions for credit card use — non-corporate Commonwealth entities |

|

Only the person issued with a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, or someone specifically authorised by that person, may use that credit card, credit card number or credit voucher. You may only use a Commonwealth credit card or card number to obtain cash, goods or services for the Commonwealth entity based on the proper use of public resources. You cannot use a Commonwealth credit card or card number for private expenditure. In deciding whether to use a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must consider whether it would be the most cost-effective payment option in the circumstances. Before using a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must ensure that the requirements in the instructions Procurement, grants and other commitments and arrangements [a separate section of the model accountable authority instructions] have been met before entering into the arrangement. You must:

|

1.6 The PGPA Act and model accountable authority instructions include other content relevant to credit card use, particularly on spending public money, official hospitality, and official travel.

- Section 23 of the PGPA Act gives accountable authorities powers to approve commitments of ‘relevant money’ and enter into arrangements (which includes procuring goods and services with credit cards).17 Accountable authorities usually delegate these powers to entity officials, specifying delegation limits for officials in certain work groups based on their position and the category of spending. While the PGPA Act does not require separate and prior approval before entering into a spending arrangement, Section 18 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires officials with spending delegations to make a written record of their approval for a commitment as soon as practicable and to follow any directions or instructions of the accountable authority. The model accountable authority instructions suggest additional instructions could include: the circumstances in which approval is required; who has authority to approve different types of commitments; appropriate approval processes; and how to ensure spending commitments would be a proper use of public resources.

- Official hospitality involves using public resources — generally, by entering arrangements under section 23 of the PGPA Act — to provide hospitality to persons other than entity officials to support the achievement of Australian Government objectives. The model accountable authority instructions suggest additional instructions could include: what is considered official hospitality; who can approve it; recordkeeping and reporting processes; whether delegates can approve official hospitality if they may personally benefit from it; and whether alcohol can be provided and what rules, if any, apply to the provision of alcohol.

- When Australian Government officials travel for business purposes, they are generally required to use whole-of-government coordinated procurement arrangements. These arrangements encompass: domestic and international air services; travel management services; accommodation program management services; travel and card related services; and car rental services. Under the arrangements, entities must make payments for flights, domestic accommodation and car rental through an account with a credit provider.18 Entities can also allow their officials to use a ‘companion’ MasterCard (available through the Diners Club arrangement) to pay for meals, incidentals and general purchasing.

1.7 The Australian Government’s Supplier Pay On-Time or Pay Interest Policy requires non-corporate Commonwealth entities to make eligible payments valued under $10,000 by payment card (which includes by credit card), and to establish and maintain internal policies and processes to facilitate the timely payment of suppliers using payment cards.19 The policy also encourages payment card use for other payments (such as payments valued over $10,000).

Overview of the Federal Court of Australia

1.8 Under the PGPA Act, the Federal Court of Australia (FCA) is classified as a non-corporate Commonwealth entity (a Commonwealth entity that is not a body corporate). The accountable authority of the FCA is the Chief Executive Officer and Principal Registrar. The FCA entity is responsible for supporting the operation of four statutory bodies:

- Federal Court of Australia — which has jurisdiction over almost all civil matters arising under Australian federal law and some criminal matters;

- Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1) — which has jurisdiction over family law matters and considers more complex matters;

- Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) — which has shared jurisdiction over family law and child support, migration law, and other general federal law areas, and refers more complex matters to the Federal Court of Australia and Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1); and

- National Native Title Tribunal — which is responsible for various functions under the Native Title Act 1993, including processing applications for native title determinations and compensation.

1.9 The total staffing number for the FCA entity as of 30 June 2023 was 1,469 employees (824 ongoing and 645 non-ongoing employees). In addition, there were 12 statutory officers and 163 judges, who were not included in the total staffing number. The FCA has office locations in all Australian states and territories.

Federal Court of Australia’s use of corporate credit cards

1.10 The FCA uses corporate credit cards for official purchases under $10,000 and CabCharge cards for domestic taxi fares. The FCA’s expenditure on these cards in 2021–22 and 2022–23 is set out in Table 1.1. Credit card expenditure represented 16 per cent of the FCA’s supplier expenses across the two years.20 In 2021–22 and 2022–23, no judges were assigned corporate credit cards, and 31 judges were assigned CabCharge cards.

Table 1.1: Credit cards in use, transactions and expenditure, 2021–22 and 2022–23

|

Card type |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||||

|

|

Cards in use |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

Cards in use |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

|

Corporate credit cards |

83 |

3211 |

$843,329 |

83 |

3559 |

$951,612 |

|

CabCharge cards |

331 |

2485 |

$110,987 |

464 |

4138 |

$217,401 |

|

Total |

414 |

5696 |

$954,316 |

547 |

7697 |

$1,169,013 |

Source: ANAO analysis of FCA data.

1.11 Table 1.2 outlines the total number of vendors to which the FCA made payments in 2021–22 and 2022–23 and the top five vendors based on transaction volume and expenditure.

Table 1.2: Credit card usage by vendor

|

Financial year |

No. of vendors paid |

Top 5 vendors based on total expenditure |

Top 5 vendors based on transaction volume |

|

2021–22 |

794 |

Matthew Bender & Co ($68,231.33) Informa UK Ltd ($37,402.97) William S. Hein & Co Inc. ($22,207.86) Mwave ($23,183.32) Digicert Inc. ($21,308.86) |

News Limited (460) Fairfax Newspapers (243) IContact (64) Booktopia Pty Ltd (52) Tesla Inc (39) |

|

2022–23 |

873 |

Informa UK Ltd ($57,262.67) Apple ($53,668.20) Matthew Bender & Co ($47,449.10) Qantas ($36,428.05) William S. Hein & Co Inc. ($27,547.23) |

News Limited (484) Fairfax Newspapers (339) Tesla Inc (89) Qantas (67) Apple (54) |

Source: ANAO analysis of FCA data.

1.12 Table 1.3 shows the FCA’s credit card spending by transaction category for expenditure between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2023 (excluding transactions with no assigned category).

Table 1.3: Credit card spending by transaction category, 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2023

|

Categorya |

Amount ($)b |

Amount % of total |

Average amount ($)b |

Count |

Count % of totalc |

|

Airline |

68,803 |

3.87 |

510 |

135 |

2.23 |

|

Lodging |

98,147 |

5.55 |

423 |

232 |

3.83 |

|

Vehicle hire |

18,799 |

1.06 |

418 |

45 |

0.74 |

|

Restaurant |

44,360 |

2.50 |

175 |

254 |

4.20 |

|

Retail services |

1,334,822 |

75.13 |

274 |

4,873 |

80.51 |

|

Vehicle related |

20,677 |

1.16 |

97 |

214 |

3.54 |

|

Other |

190,678 |

10.73 |

636 |

300 |

4.96 |

|

Total |

1,776,286 |

100.00 |

N/A |

6,053 |

100.00 |

Note a: Transactions that had no merchant category coding in Smartdata were not included in the figures. The value of uncategorised transactions was $18,655.

Note b: Figures have been rounded to the nearest dollar.

Note c: Figures do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of Commonwealth Bank Smartdata transaction reporting.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.13 The misuse of corporate credit cards, whether deliberate or not, has the potential for financial losses and reputational damage to government entities and to the Australian Public Service. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) states that:

establishing a pro-integrity culture at the institutional level means setting a culture that values, acknowledges and champions proactively doing the right thing, rather than purely a compliance-driven approach which focuses exclusively on avoidance of wrong doing.21

1.14 In describing the role of Senior Executive Service (SES) officers, the APSC states that the SES ‘set the tone for workplace culture and expectations’, they ‘are viewed as role models of integrity’ and ‘are expected to foster a culture that makes it safe and straightforward for employees to do the right thing’.22 The New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption identifies organisational culture and expectations as a key element in preventing corruption and states:

[T]he way that an agency’s senior executives, middle managers and supervisors behave directly influences the conduct of staff by conveying expectations of how staff ought to act. This is something that affects an agency’s culture.23

1.15 Deliberate misuse of a corporate credit card is fraud. The Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile indicates that credit cards are a common source of internal fraud risk. Previous audits have identified issues in other entities relating to positional authority for approving credit card transactions24 and ineffective controls to manage the use of credit cards.25 This audit was conducted to provide the Parliament with assurance that the FCA is effectively managing corporate credit cards in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the FCA’s management of the use of corporate credit cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO examined:

- whether the FCA has effective arrangements in place to manage the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards; and

- whether the FCA has implemented effective controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures.

1.18 The audit focused on the FCA’s management and use of corporate credit cards, including travel approval and acquittals, in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 financial years.

Audit methodology

1.19 The audit methodology included:

- review of legislative and entity frameworks guiding the use of corporate credit cards;

- review of the FCA’s documentation, including policies and procedures, risks registers, training material and reporting;

- analysis of the FCA’s data, including publicly reported information and data obtained during the audit; and

- meetings with FCA staff.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $249,000.

1.21 The team members for this audit were Hayley Tonkin, Priyanka Varma, Brinlea Paine and Daniel Whyte.

2. Arrangements for managing corporate credit cards

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Federal Court of Australia (FCA) had effective arrangements in place to manage the issue, return, and use of corporate credit cards.

Conclusion

The FCA’s arrangements for managing the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards were largely effective. The FCA had considered risks associated with the use of corporate credit cards within its overarching risk framework and identified relevant controls. Policies and procedures included core requirements but lacked detail on eligibility criteria for issuing cards and requirements for using CabCharge cards. No structured training and education arrangements were in place to promote compliance with policy and procedural requirements. While arrangements had been established for monitoring and reporting on credit card issue, return and use, detailed reporting was not provided to the FCA’s executive management on credit card non-compliance. The FCA did not respond to Parliamentary questions on notice with accurate reporting on credit card use.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at ensuring FCA’s policies and procedures include eligibility criteria for issuing cards (paragraph 2.26) and approval requirements for the use and acquittal of CabCharge cards (paragraph 2.38).

The ANAO identified three opportunities for improvement for the FCA to: strengthen its fraud control testing (paragraph 2.17); periodically provide educational messaging to cardholders and managers; and provide detailed reporting on credit card non-compliance to executive management (paragraph 2.48).

2.1 If Australian Government officials deliberately misuse corporate credit cards, they are committing fraud. Other risks of credit card use include: inadvertent personal use; unauthorised or inappropriate work use; incorrect charging by merchants; and external fraud enabled by stolen credit card details.

2.2 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), an accountable authority of an Australian Government entity has a duty to establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight and management and internal control, including measures to ensure that officials comply with the finance law.26

2.3 In addition, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) establishes a requirement for an accountable authority to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity.27 Specific requirements of the Fraud Rule include:

- conducting regular fraud risk assessments and developing and implementing a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks;

- establishing appropriate preventive controls (which should include fit-for-purpose policies and procedures and effective training and education arrangements); and

- establishing appropriate monitoring and reporting arrangements.

Have appropriate arrangements been established for managing risks associated with use of corporate credit cards within the Federal Court of Australia?

The FCA had considered risks associated with the use of corporate credit cards within its overarching risk framework and identified relevant controls. Its enterprise-level fraud risk register identified misuse or unauthorised use of corporate credit cards as a low risk. The register was last updated in June 2021 and the FCA had not recently tested the effectiveness of its credit card controls. Risk monitoring and reporting arrangements were undergoing change and yet to be formalised.

Enterprise risk management arrangements

Enterprise Risk Management Policy and Plan

2.4 The FCA has a Risk Management Policy (February 2023) which sets out general requirements and minimum standards that need to be considered when implementing the risk management framework. The policy outlines the approach that should be taken to prepare for dealing with entity specific risks. This includes developing relevant risk methodologies and policies, establishing robust governance and roles and responsibilities, defining shared risks, and promoting a risk management culture. The policy states:

Identified risks are the responsibility of an owner. The risk owner is responsible for the implementation of the risk treatment plans, and will report to the Enterprise Risk Management Committee (EMRC) through the Risk & Audit Advisor, on its implementation progress within agreed timeframes.

2.5 The FCA’s Risk Management Plan (February 2023) provides a framework to identify and manage risk at the enterprise level. The plan provides general information on risk management within the entity, including relevant stakeholders, risk training, governance structures, risk owners, and guiding principles. The plan states that risks identified in the FCA are allocated to a risk owner who is accountable for management of the risk, its controls and their effectiveness.

2.6 The Risk Management Plan outlines enterprise risk categories that arise from aspects of the FCA’s business. This includes the category of ‘Financial’, which covers activities and risks including fraud, financial management, cost of goods and services, and procurement. The plan does not explicitly reference misuse of credit cards. It identifies misuse of funds as an example of a risk within the category. The plan states that the FCA has ‘medium risk tolerance’ for financial risks. In contrast, the plan notes that the FCA has ‘little or no tolerance’ for integrity or compliance related risks.

Risk Management Governance Framework

2.7 The FCA documented a revised Risk Management Governance Framework (the framework) in February 2024, outlining risk management reporting arrangements and roles and responsibilities within the entity. The framework identifies risk owners by business unit, including identifying the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) as the risk owner for the ‘Finance’ function. The framework noted that risk oversight and monitoring arrangements were ‘yet to be formalised’. The framework also noted the need to identify control owners, with no status documented for this action.

2.8 In line with the framework, a ‘Finance’ function risk register was developed through consultation with finance team. An extract of the risk register dated 12 March 2024 included one risk rated ‘high’, six rated ‘medium’, and 17 rated ‘low’. One ‘low’ risk related to credit card usage:

Staff making false claims (e.g. sick leave, overtime, timesheets, expenses or worker’s compensation, credit card usage for personal use)

2.9 This risk had a likelihood rating of ‘possible’, a consequence rating of ‘moderate’, an inherent risk rating of ‘medium’, and a residual risk rating (after control measures) of ‘low’. The next review date identified in the extract was 15 August 2024.

2.10 Control measures for this risk noted in the register were:

- Fraud Control Plan in place published on the intranet

- Tiered financial delegations as per AAIs

- The Entity also has a mature fraud incident reporting framework with responsible officers appointed at senior levels.

- Monthly review and approval of staff expenses to prevent cases of internal fraud.

- Manager Court Services to review and approve.

- Finance Department to test sample expenses.

- Discrepancies are investigated internal and reported if needed.

2.11 The effectiveness of these control was rated as ‘very good’ in the register. The FCA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that control effectiveness had been assessed through ‘risk control self-assessment’, which involved an undocumented discussion between the FCA’s risk advisor and the risk owner.

Fraud Control Plan and Fraud Risk Register

2.12 The FCA’s Fraud Control Plan and Fraud Risk Register (June 2021) were developed to meet the entity’s obligations under the PGPA Fraud Rule.

2.13 The objective of the Fraud Control Plan is to ‘establish mechanisms to deter, detect and respond to instances of possible fraudulent activity.’ The plan states that the FCA has a ‘zero tolerance’ attitude to fraudulent activities.

2.14 The Fraud Risk Register identifies eight fraud risks to the FCA including one risk relating to misuse or unauthorised use of corporate credit cards. The credit card fraud risk was rated as ‘low’ (with a likelihood rating of ‘unlikely’ and consequence rating of ‘minor’), as per the most recent fraud risk assessment undertaken in 2021. The following controls and mitigating practices were documented in the register:

- credit cards are only used for low level purchases;

- all transactions require receipts;

- a limited number of credit cards in circulation;

- low card limit levels; and

- guidelines for lost or stolen cards, resignation and inadvertent use.

2.15 Controls were largely operating as described, except that:

- there was no policy requirement for CabCharge card receipts to be provided to travellers’ managers post-travel (see 3.41), so not all transactions require receipts to be retained and reviewed; and

- the FCA has not defined what constitutes a ‘low card limit level’.

2.16 Entities are encouraged to conduct fraud risk assessments at least every two years.28 The next scheduled review date in the FCA’s Fraud Control Plan and Fraud Risk Register was June 2023. As of April 2024, the FCA had not updated its fraud risk assessment, nor updated its Fraud Control Plan and Fraud Risk Register since June 2021.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.17 Fraud control testing involves various methods including desktop reviews, system or process walkthroughs, data analysis, sample testing and pressure testing.29 The FCA could strengthen its fraud control framework by employing different testing methods and better documenting testing outcomes. |

Audit and risk committee consideration

2.18 The FCA’s Audit and Risk Committee provides oversight of the entity’s risk management, internal control framework, compliance and governance. Over the last seven years two internal audits relevant to corporate credit cards have been undertaken and reported to the committee:

- Corporate Credit Cards (November 2017); and

- Fraud Control and Corruption and Process Review (August 2023).

2.19 The August 2023 Fraud Control and Corruption Process Review, undertaken by RSM Australia30, found that processes and controls for managing fraud and corruption were operating effectively. The audit identified a ‘low risk’ issue relating to FCA’s lack of a formalised data analytics program for fraud and corruption, and recommended that the FCA:

Either enhance the existing month end data analytics testing, or revise the existing data analytic testing to create a formalised, documented and implemented fraud and corruption data analytics detection policy, procedure, and program covering all financial and other relevant transactions at the FCA.

2.20 In response to the recommendation, the FCA agreed to implement enhanced data analytics testing as part of its month end financial procedures and give consideration to introducing a fraud and corruption detection procedure covering relevant transactions. The FCA’s revised approach was documented in a March 2024 internal memorandum which outlined a series of checks that were undertaken for February 2024 month end reporting. The FCA has not tracked the implementation of the recommendation and progress has not been reported to the Audit and Risk Committee.

2.21 The FCA established an internal Enterprise Risk Management Committee (ERMC) in 2019 to support the Audit and Risk Committee and monitor the effectiveness of controls. The FCA’s February 2023 Risk Management Plan states that the ERMC is responsible for endorsing the annual enterprise-wide risk register and risk reports, and the Chair of the ERMC will provide reports on the outcomes of the ERMC meetings at each Audit and Risk Committee meeting. The FCA advised the ANAO in April 2024 that the functions of the ERMC had been devolved to functional risk managers in 2022, and the FCA was intending to reinstate the ERMC after it had resourced its governance, risk and compliance team, which was formed in January 2024.

Has the Federal Court of Australia developed fit-for-purpose policies and procedures for the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards?

The FCA’s policies and procedures for the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards included core requirements, which were covered within the FCA’s accountable authority instructions and other policies. Eligibility requirements for issuing credit cards could be improved by defining business need criteria for card issuance in policies and procedures. More guidance could be provided on using and acquitting CabCharge cards.

Issue

2.22 The FCA’s Commonwealth Credit Card Policy (October 2019) does not outline eligibility criteria or specific business needs for being issued a credit card, other than noting a requirement for a cardholder to be a permanent, ongoing employee (unless approval is granted by the Chief Financial Officer). The policy states:

When an Employee requires a Commonwealth Credit Card or Vendor Card, the Employee’s manager must request an application form from the Finance Team. The Finance Team will then issue the relevant forms including the Cardholder Agreement, which needs to read and signed by the Employee.

2.23 The ANAO’s analysis of the FCA’s current credit card register indicates that credit cards were issued to officers in positions with a business need. Corporate credit cards were largely held by three groups of staff:

- library staff — to purchase books and other resource material from overseas vendors;

- information technology staff — to purchase IT equipment and software; and

- administrative staff in registries — to make purchases for registry use, such as travel, events, training courses and newspaper subscriptions.

2.24 The FCA had 83 corporate credit cards and 464 CabCharge cards in use in 2022–23. Criteria for determining business needs for CabCharge cards were not documented.

2.25 The Commonwealth Credit Card Policy has not been updated to reflect changes in the FCA’s credit card issue process whereby employees now complete an online application form and cardholder acknowledgement through a Commonwealth Bank of Australia internet-based portal. The FCA’s finance team is unable to view or download online application forms, so has limited visibility of the online submission process.

Recommendation no.1

2.26 The Federal Court of Australia update its policies and procedures for issuing credit cards and CabCharge cards to provide guidance on eligibility criteria and accurately reflect current processes.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

2.27 The Federal Court of Australia agrees that the current Commonwealth Credit Card Policy could be strengthened by including specific guidance on eligibility criteria.

Use

Accountable Authority Instructions

2.28 The FCA’s Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) (November 2020) include the Department of Finance’s model instructions for credit cards outlined at Box 1 in Chapter 1. Additional instructions are included that require officials responsible for supervising credit card holders to notify the FCA’s finance team when a cardholder needs their credit limit amended or no longer requires a card, and ensure they approve all transactions within the acquittal portal by the 15th of each month.

2.29 The FCA’s AAIs also contain instructions for all officials on procurement, official hospitality and official travel, which are relevant to credit card use, including:

You must … use any mandated whole-of-government [procurement] arrangement …31

Any decision to spend relevant money on official hospitality must be publicly defensible.

Where the government has established coordinated procurements for a particular travel activity, you must use the arrangement established for that activity, unless:

- an exemption has been provided in accordance with the [Commonwealth Procurement Rules] or reimbursement is to be provided to a third party (i.e. a non-Commonwealth traveller that cannot access coordinated travel procurements) for airfares, accommodation and/or car rental; or

- a travel allowance is to be provided for accommodation arrangements.

Commonwealth Credit Card Policy

2.30 The FCA’s Commonwealth Credit Card Policy states:

When making a purchase, the cardholder must ensure:

- There is a legitimate business purpose justifying the expense,

- The purchase is consistent with achieving the [FCA’s] objectives, and

- The expectation that the purchase will achieve the business purpose is reasonable. […]

An employee must not obtain, or be perceived to obtain, a personal gain, via independent scrutiny referring to standards included in this Policy.

Ethical purchases occur when it can be readily demonstrated that the item/service purchased is for [FCA] business and undertaken in a manner that would stand up to reasonable independent scrutiny, for example independent audit.

2.31 The policy states that corporate credit cards must not be used for:

- private purchases;

- purchases by any other person than the cardholder;

- payments above the cardholder’s delegation (unless prior written approval is received from an appropriate delegate);

- gratuities (tips);

- enabling payment via devices (such as phones or tablets) where the card is not required to be present;

- goods and services ordered on a Purchase Order; and/or

- domestic travel and accommodation (excluding on-country remote accommodation).

2.32 Further, the policy outlines that no employee can approve their own expenditure, all purchases must be supported by a tax invoice, receipt or statutory declaration, and managers must review their employees’ transactions and ensure they are made in accordance with the policy and relevant financial delegations.

Official Hospitality and Entertainment Policy

2.33 The FCA’s Official Hospitality and Entertainment Policy (February 2020) outlines that hospitality and entertainment expenditure must receive prior approval from designated senior officials, and must withstand scrutiny on the grounds that the expenditure:

- is appropriate and within the allocation of funds for that purpose;

- contributes to the efficient and effective conduct of the activities of the FCA; and

- is not for the sole purpose of providing entertainment for FCA employees or statutory officers.

2.34 While no payment limits with relation to alcohol or catering are defined, the policy states:

The provision of alcohol for formal entertainment where that entertainment conforms to the overarching principle set out in this policy, is acceptable. This includes occasional entertainment of fellow officials and subordinates for the purpose of promoting good staff relations or in recognition of a special achievement or event.

In contrast, entertainment of an informal nature provided by an official to fellow officials and subordinates, such as after work drinks, must not be provided at public expense. These are personal expenses which must be met by the officials involved.

2.35 The FCA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that the policy is currently under review, with discussions ongoing as to which officials are able to approve hospitality expenditure.

Domestic Travel Policy

2.36 The FCA’s Domestic Travel Policy (June 2023) documents how the FCA manages official travel and includes guidance on the use of CabCharge cards. The policy outlines that all official FCA travel is to be booked through the FCA’s travel management software (Expense8). In relation to taxi and ride-share services, it states:

All officials that undertake regular travel throughout the year can apply for a CabCharge card, with their manager’s approval. Infrequent travellers can obtain eTickets for CabCharge from the Finance Team.

2.37 While the policy states that employees must provide receipts to travel approvers when using ride-sharing services, there are no travel approver or receipt requirements stated in the policy for trips taken using CabCharge cards. The policy does not cover when the use of CabCharge cards is appropriate.32

Recommendation no.2

2.38 The Federal Court of Australia update its policies and procedures for credit card use to provide additional guidance on receipt and approval requirements for CabCharge cards.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

2.39 The Federal Court of Australia agrees that the current Commonwealth Credit Card Policy (which also covers the use of CabCharge cards) could be strengthened by providing additional guidance for the acquittal of CabCharge cards.

Use of credit cards for purchases over $10,000

2.40 As noted at paragraph 1.7, the Australian Government’s Supplier Pay On-Time or Pay Interest Policy requires non-corporate Commonwealth entities to make eligible payments33 valued under $10,000 by payment card (which includes by credit card), and to establish and maintain internal policies and processes to facilitate the timely payment of suppliers using payment cards. The FCA has incorporated this requirement into its AAIs.

2.41 Table 2.1 provides accounts payable data and credit card transaction data from 2021–22 and 2022–23.

Table 2.1: Accounts payable and credit card transactions under $10,000

|

Payment type |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||

|

|

No. of transactions under $10,000 |

Expenditure |

No. of transactions under $10,000 |

Expenditure |

|

Accounts payable |

15,391 |

$13,435,551 |

19,574 |

$17,739,782 |

|

Credit card |

3,109 |

$892,467 |

3,493 |

$935,179 |

Source: ANAO analysis of FCA data.

2.42 Some accounts payable transactions cannot be paid by credit card (such as travel allowances, staff/judicial reimbursements, large account and milestone payments, or payments to individuals or sole traders without a credit card facility). Approximately 25 per cent of the FCA’s accounts payable transactions under $10,000 in 2022–23 were for courier services, subscription services, stationery and other low-value purchases where a credit card could potentially have been used.

Return

2.43 The FCA’s Commonwealth Credit Card Policy includes requirements for the return of credit cards. It states that, if cardholders are aware they will be on leave for an extended period or secondment to another entity, they must return their credit card to their manager or the finance team and email the finance team confirming the card has been returned and the period for which it will be held. In addition, upon resignation, termination, secondment or change in position, the finance team must be immediately notified to cancel an employee’s credit card and arrangements must be made to securely dispose of the card.

2.44 The FCA’s online employee separation form includes a prompt for managers to confirm that cardholders ceasing employment have returned their credit cards.

Has the Federal Court of Australia developed effective training and education arrangements to promote compliance with policy and procedural requirements?

While the FCA had published relevant policies and procedures on its intranet, it did not provide structured training and education to promote compliance with corporate credit card policy and procedural requirements. Support was provided by the FCA’s finance team for cardholders and managers upon card issuance and when requested.

Intranet guidance

2.45 The FCA has written guidance material relating to corporate credit cards available to staff on its intranet. This material includes the Commonwealth Credit Card Policy and two supporting standard operating procedures, a Cardholder Guide and Approvers Guide, which provide step-by-step instructions for cardholders and delegates on completing monthly acquittals. New card holders are advised to review the credit card policy and are required to sign an acknowledgement of their obligations as card holders.

2.46 No guidance was available for CabCharge cards, with the only information available for cardholders contained within the Commonwealth Credit Card Policy and Domestic Travel Policy.

Other training

2.47 The FCA advised the ANAO in November 2023 that the finance team offers tailored support to individual cardholders and managers if they feel further guidance may be beneficial. Internal communications from the finance team demonstrated that the team had offered to provide new cardholders with guidance and one-on-one support and sent reminders to complete acquittal processes. Documentation from March 2024 shows the FCA’s finance team and people and culture team had commenced discussions on developing a credit card specific training module for cardholders, which was intended to be delivered in 2024.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.48 To ensure cardholders and managers comply with policy and procedural requirements for credit cards and CabCharge cards, the FCA could periodically provide messaging that highlights good practices, outlines compliance requirements relating to the use of credit cards for purchases under $10,000, and raises awareness of fraud and non-compliance risks. This could be through intranet posts, messages within all staff email, or reminders at staff meetings. |

Does the Federal Court of Australia have appropriate arrangements for monitoring and reporting on the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards?

The FCA had arrangements in place for monitoring and reporting on the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards. Credit card usage was monitored by the FCA’s finance team. Detailed reporting on credit card non-compliance was not provided to the FCA’s executive management, diminishing its understanding of fraud, risk and integrity implications arising from non-compliance. While FCA reported on credit card issue and use when requested by Parliament, there were errors in its reporting.

Monitoring issue and return

2.49 The FCA finance team maintains spreadsheet-based registers for both corporate credit card and CabCharge card holders.

- Credit cards register — The credit card register records details of cardholders’ location, position, card number, expiry date, monthly card limit, individual transaction limit, and card status. The register was up to date and included relevant details for each card holder.

- CabCharge card register — The CabCharge card register captures details of cardholders’ location, position, card number, expiry date, manager, and card status. The register was up to date and included relevant details for each card holder.

2.50 The FCA’s finance team advised the ANAO in March 2024 that it conducts a biannual review of existing cardholders on the register to identify unused cards that can be cancelled. Periodic reviews were undertaken, but this process was not formally documented in the FCA’s policies and procedures.

Monitoring use

2.51 Credit card usage data for the FCA is managed and captured through three software applications, which also provide reporting capability:

- Smartdata — used for credit card transaction reporting, acquittals, approvals and monitoring;

- CabCharge+ — used to manage CabCharge accounts and extract CabCharge card transactions; and

- Expense8 — used for domestic travel arrangements and approvals.

2.52 While FCA’s finance team draws reports from these systems for acquittal purposes, it does not use them to produce management reporting on a regular basis.

2.53 The FCA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that it was in the process of introducing CabCharge reporting arrangements which would enable managers to have oversight of and review their direct reports’ taxi trips and CabCharge card spending. The FCA also advised that Uber was currently being piloted as a taxi alternative, with in-built reporting and compliance protocols.

Compliance reporting

Reporting to executive management

2.54 The FCA’s PGPA Act compliance reporting has included coverage of credit card usage and is provided to the FCA’s executive management biannually.

- In the June 2023 report, it was noted that two cardholders failed to reconcile the monthly statements for multiple periods. These cardholders were given final warnings to acquit purchases, otherwise cards would be cancelled. For this period, the FCA assessed the controls to address this as partially compliant with internal policy requirements and the PGPA Act. Both cardholders worked with the finance team to acquit transactions after the warning was issued, so neither of the cards were cancelled.

- In the December 2022 report, one instance of a credit card holder not understanding the policy on parking was identified. This resulted in the FCA recovering the funds for private parking charges. The FCA noted that controls to address this could be strengthened, but no subsequent actions were undertaken to strengthen controls.

2.55 The FCA’s executive management has not received detailed reporting relating to credit card non-compliance, or actions taken in response to non-compliance. This reduces its visibility of non-compliance and the effectiveness of internal controls, impacting its ability to understand and manage fraud and integrity risks.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.56 To provide visibility of non-compliance and the effectiveness of internal controls, including management of fraud and integrity risks, the FCA could provide detailed reporting to FCA’s executive management on corporate credit card non-compliance and actions taken in response to non-compliance. |

Reporting to Parliament on corporate credit card issue and use

2.57 The FCA provided responses to questions on notice on the issue and use of credit cards that were asked of the Attorney General’s Portfolio in Senate Estimates hearings in 2022–23 and 2023–24. The FCA’s responses to these questions are outlined in Table 2.2 (see Appendix 3 for the complete set of questions).

Table 2.2: Responses to Senate Estimates questions on notice on credit cards

|

Question |

2022–23 Suppl. Budget estimates (asked 3/03/23) |

2022–23 Budget estimates (asked 19/06/23) |

2023–24 Suppl. Budget estimates (asked 2/11/23) |

|

Period covered by answer |

2022–23 financial year to date |

2022–23 financial year to date |

2023–24 financial year to date |

|

Number of cards on issuea |

78 |

73 |

77 |

|

Largest reported purchase |

$15,129 |

$15,129 |

$15,753.57 |

|

No. of cards reported lost or stolen |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

No. of purchases deemed illegitimate or contrary to policy |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

Amount of illegitimate or contrary to policy purchases |

$29.65 |

$110.56 |

$45.97 |

|

Amount repaid |

$29.65 |

$110.56 |

$45.97 |

|

Highest value illegitimate or contrary to policy purchase repaid |

$29.65 |

$76.11 |

$45.97 |

Note a: The FCA reported on the number of corporate credit cards on issue, which did not include CabCharge cards.

Source: Senate estimates question on notice database.

2.58 The FCA interpreted ‘illegitimate or contrary to policy’ to be staff misuse, so fraudulent transactions were not reported. One instance of inadvertent staff misuse in 2022–23 (a $16.15 transaction for personal parking made on 12 December 2022) was not included in the FCA’s responses to the questions asked on 3 March 2023 and 19 June 2023.

3. Controls and processes for corporate credit cards

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Federal Court of Australia (FCA) has implemented effective controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures.

Conclusion

The FCA’s implementation of controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures was partly effective. There were weaknesses in its preventive controls relating to assessing and recording business needs for issuing credit cards and documenting pre-approval and rationales for purchases. The implementation of detective controls was partly effective, with no managerial review process for CabCharge card transactions and no use of data analytics across credit card transactions to detect potential instances of purchase splitting. These deficiencies heighten the risk that instances of credit card non-compliance could go undetected. Where misuse was detected, the FCA used established escalation processes and mechanisms to deal with non-compliant transactions.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at: improving preventive controls for capturing pre-approvals and rationales for certain transactions (paragraph 3.19); improving detective controls by strengthening acquittal and approval processes for CabCharge card transactions (paragraphs 3.28 and 3.45); and conducting data analysis of credit card transactions targeting key areas of risk, including purchase splitting (paragraph 3.57).

The ANAO identified two opportunities for improvement for the FCA to: establish a systematic approach to assessing and recording business needs for issuing credit cards and CabCharge cards (paragraph 3.7); and review its offboarding process to reduce reliance on cardholders’ managers to manage credit cards returns (paragraph 3.33).

3.1 Preventive controls work by reducing the likelihood of inappropriate credit card use before a transaction has been completed. Preventive controls for credit cards can include: policies and procedures; education and training; deterrence messaging; declarations and acknowledgements; blocking certain categories of merchants; issuing cards only to those with an established business need; placing limits on available credit; and limiting the availability of cash advances.

3.2 Detective controls work after a credit card transaction has occurred by identifying if there is a risk that it may have been inappropriate. Detective controls for credit cards can include: regular reconciliation processes (with segregation of duties between cardholder and approver); exception reporting; fraud detection software; tip-offs and public interest disclosures; monitoring and reporting; and audits and reviews.

3.3 When detective controls identify instances of fraud or non-compliance, entities should have effective processes in place for managing investigations and follow-up actions (such as further training, sanctions, or referral to law enforcement agencies).

Has the Federal Court of Australia implemented effective preventive controls on the use of corporate credit cards?

The FCA’s implementation of preventive controls did not include a systematic approach to assessing and recording that staff have valid business needs prior to issuing credit cards. There were control weaknesses in documenting pre-approvals and rationales for entertainment purchases and purchases covered by whole-of-government arrangements. There were also control weaknesses in documenting pre-approvals for CabCharge card transactions that fell outside approved domestic travel budgets. The card returns process placed a reliance on the relevant manager both identifying that the employee had a card to return and ensuring the card was either returned to the finance team or destroyed.

Issuing credit cards

3.4 Issuing corporate credit cards to staff with an established business need is a key preventive control to reduce the risk of inappropriate use.

3.5 The FCA does not have a systematic approach to recording that employees have a valid business need prior to card issuance. The FCA has not established a documented process that should be followed when assessing business need. There is a reliance on informal communications between managers and the finance team to validate the business needs of prospective cardholders prior to cards being issued.

3.6 Once approval is obtained from the finance team, employees complete an online application through a Commonwealth Bank of Australia internet-based portal. The finance team is unable to view or download the completed applications from the portal, so has limited visibility of application content and the status of applications.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

3.7 The FCA could establish a more systematic approach to assessing and recording business needs for issuing credit cards and CabCharge cards. |

Managing transactions

Credit card spending limits

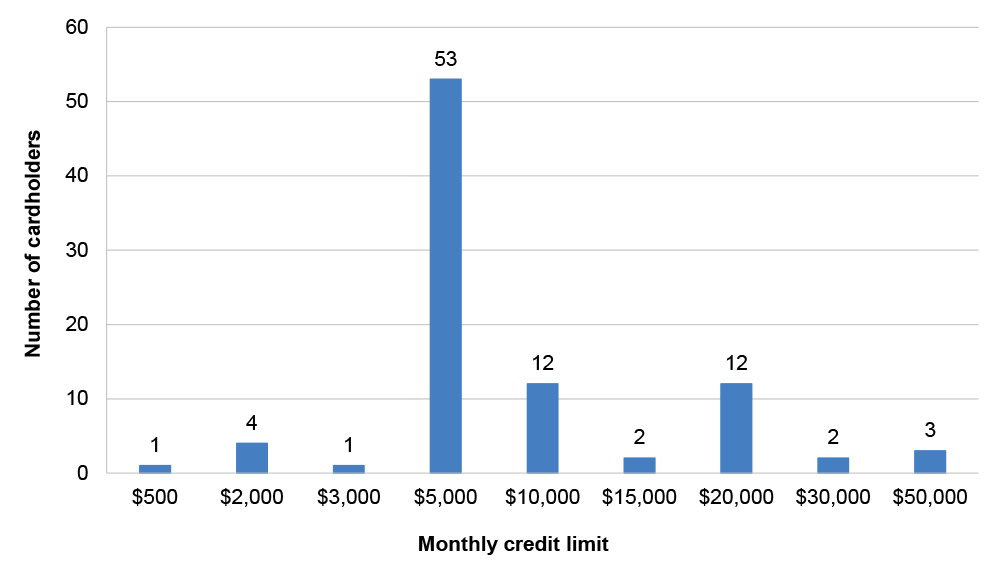

3.8 While the FCA has not specified credit card spending limits in its Commonwealth Corporate Credit Card Policy, monthly spending limits were documented in its credit card register for each cardholder. The spread of monthly spending limits across the entity is outlined in Figure 3.1. Cardholders with limits between $20,000 and $50,000 all held management positions within the library, information services and information technology areas of the FCA.

Figure 3.1: FCA assignment of monthly credit card limits for corporate credit cards

Source: ANAO analysis of FCA data.

Pre-approval for credit card purchases

3.9 Pre-approval and documentation of rationale for certain types of expenditure is a key control to ensure purchases are appropriate and can withstand public scrutiny.

Purchases covered by whole of Australian Government arrangements

3.10 As noted at paragraph 2.29, the FCA’s Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) require staff to use any mandatory coordinated procurement arrangement (such as arrangements established by the Department of Finance and Digital Transformation Agency for accommodation and travel services, stationery and office supplies, and ICT equipment).

3.11 Analysis of the FCA’s credit card transactions shows there were transactions in categories covered by mandatory coordinated procurement arrangements in 2022–23 (see Table 3.1)

Table 3.1: Transactions not using whole-of-government arrangements in 2022–23

|

Merchant |

Category |

Number of transactions |

Sum of transaction value |

|

Apple |

ICT equipment |

54 |

$53,668.20 |

|

Officeworks |

Stationery and office supplies |

74 |

$17,043.14 |

|

Avis Rent-a-Car |

Car rental services |

8 |

$2,632.40 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Commonwealth Bank Smartdata transaction reporting.

3.12 Acquittal records reviewed as part of sample testing did not include evidence of pre-approval and the rationale for not using the mandatory arrangements was not documented.

3.13 The FCA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that the SmartData system only allows one document to be attached for each transaction, with the FCA’s requirement being the attachment of tax invoices. As there is no facility to add further documentation (such as evidence of pre-approval) in SmartData, the FCA noted that it relies on cardholders maintaining records of expenditure approvals on the FCA’s network drive. This practice undermines the capacity of the entity to obtain assurance that purchases are compliant with policy requirements or to identify potentially fraudulent transactions.

Official hospitality and entertainment expenditure

3.14 As noted at paragraph 2.29, the FCA’s AAIs state that decisions to spend money on official hospitality must be publicly defensible. As noted at paragraph 2.33, the FCA’s Official Hospitality and Entertainment Policy outlines that hospitality and entertainment expenditure must receive prior approval from designated senior officials, and must withstand scrutiny.

3.15 FCA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that approval for entertainment purchases is usually provided verbally by the appropriate delegate, which is permitted under the FCA’s AAIs providing the approval is documented by the delegate as soon as practicable.

3.16 The ANAO analysis of the FCA’s credit card data identified a range of food and beverage related transactions that potentially related to official entertainment and hospitality (see Table 3.2). Additional analysis was conducted on transactions at alcoholic beverage merchants (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.2: FCA credit card expenditure on food and beverage, 2021–22 and 2022–23

|

Categorya,b |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||

|

|

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

|

Package stores, beer, wine, liquor |

31 |

$12,740 |

41 |

$14,318 |

|

Bakeries |

8 |

$1,305 |

5 |

$435 |

|

Caterers |

4 |

$1,586 |

21 |

$5,325 |

|

Eating places, restaurants |

65 |

$6,794 |

82 |

$12,893 |

|

Fast food restaurants |

35 |

$2,656 |

28 |

$3,339 |

|

Grocery stores, supermarketsc |

164 |

$5,782 |

230 |

$20,996 |

|

Miscellaneous food store, convenience stores, markets, specialty stores, and vending machines |

12 |

$973 |

14 |

$1,312 |

|

Total |

319 |

$31,836 |

421 |

$58,618 |

Note a: Categories are based on merchant category coding established by Mastercard.

Note b: Some transactions may relate to employees’ travel purchases (i.e. meals at restaurants and purchases from supermarkets).

Note c: Not all transactions at grocery stores and supermarkets related to food and beverage expenditure.

Source: ANAO analysis of Commonwealth Bank Smartdata transaction reporting.

Table 3.3: FCA credit card expenditure at alcohol merchants, 2021–22 and 2022–23

|

Merchant name |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||

|

|

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

|

BWS |

3 |

$399 |

5 |

$631 |

|

Dan Murphy’s |

27 |

$12,193 |

29 |

$12,724 |

|

Liquorland |

2 |

$328 |

2 |

$327 |

|

Vintage Cellars |

1 |

$478 |

3 |

$256 |

|

Red Bottle |

1 |

$275 |

1 |

$172 |

|

Kemeny’s Food and Liquor |

0 |

0 |

3 |

$6,180 |

|

Wine Sellers Direct |

0 |

0 |

1 |

$319 |

|

Total |

34 |

$13,673 |

44 |

$20,609 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Commonwealth Bank Smartdata transaction reporting.

3.17 The ANAO conducted targeted testing of the 42 alcohol related entertainment transactions from 2022–23, which found documented prior approval for purchases was not consistently recorded.

- 38 out of 42 tested transactions were not supported by sufficient documented evidence of delegate pre-approval.34

- Two transactions were approved by delegates in the system with incomplete receipts attached. One of these transactions was identified by the finance team and the complete receipt was provided by the cardholder upon request.

- One instance of purchase splitting was identified. The same cardholder made three separate purchases at Dan Murphy’s on 19 April 2023 at similar times for the same function. The sum of the three transactions was $1,166.59, which exceeded the cardholder’s individual transaction limit of $1,000.35 The FCA’s policies and procedures do not cover purchase splitting and its potential risks. As of April 2024, the three transactions had not been approved in the system, with no evidence of follow-up or escalation occurring with the cardholder or relevant manager.

3.18 Based on the descriptions in FCA’s system for each transaction, the rationales for the 42 alcohol purchases were: Chief Justice hosted events (14); miscellaneous meetings, workshops, seminars or meetings (11); ceremonial sittings (7); events for judges (5); National Native Title Tribunal farewells (3); and gifts (2).

Recommendation no.3

3.19 The Federal Court of Australia establish a process to confirm evidence of pre-approval by the designated official and the rationale for spending are documented when acquitting credit card transactions for official hospitality and entertainment purchases and instances where whole-of-government arrangements are not being utilised.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

3.20 The Federal Court of Australia agrees that the current process to ensure evidence of pre-approval for credit card transactions could be strengthened by:

- reinforcing the requirement of documented delegate pre-approval through staff refresher training; and

- providing additional guidance on the existing acquittal process for recording of spending pre-approval.

Use of CabCharge cards

3.21 The FCA advised the ANAO in December 2023 that there is a $300 (excluding GST) transaction limit for CabCharge card transactions. This was not documented in its policies and procedures or its CabCharge Card Agreement form.

3.22 The $300 transaction limit was adhered to, with no transactions from 2021–22 and 2022–23 exceeding the limit.

3.23 CabCharge transactions that formed part of a broader domestic travel budget were recorded in Expense8 and approved by the traveller’s manager. Manager approvals for one-off taxi transactions (usually within the same city) were not formally captured prior to travel.

3.24 The FCA’s CabCharge Card Agreement requires the cardholders to agree that they ‘will not use the CabCharge Card to incur expenditure except with the prior approval of a delegate on each occasion’. The FCA advised the ANAO in December 2023 that manager approval could be obtained in various ways including in writing, verbally, or through a diary note. Inconsistencies in the way approvals are obtained and recorded increases the risk that approval is not obtained in accordance with requirements and limits the FCA’s ability to undertake assurance activities over CabCharge card usage.

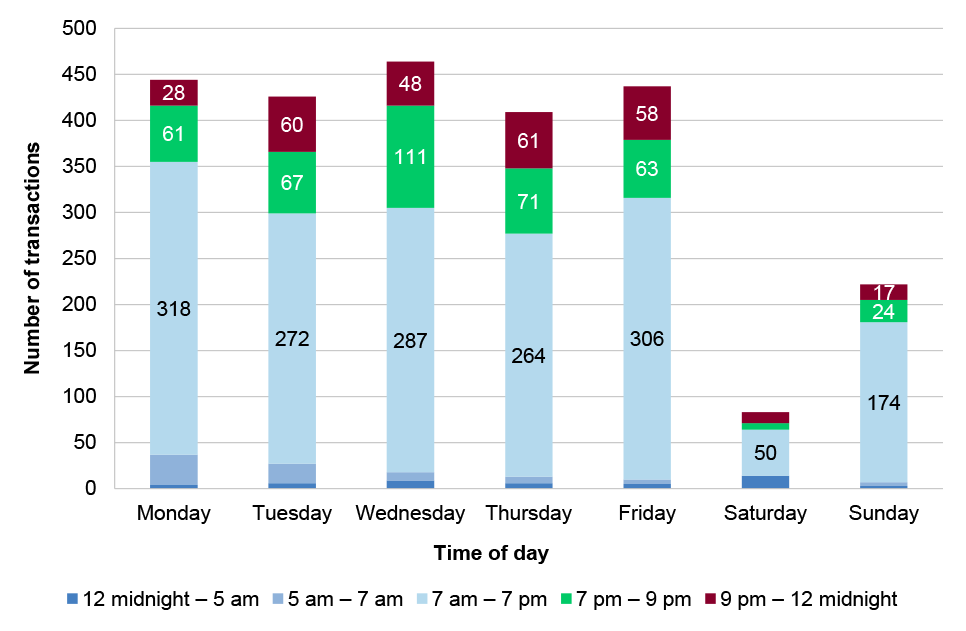

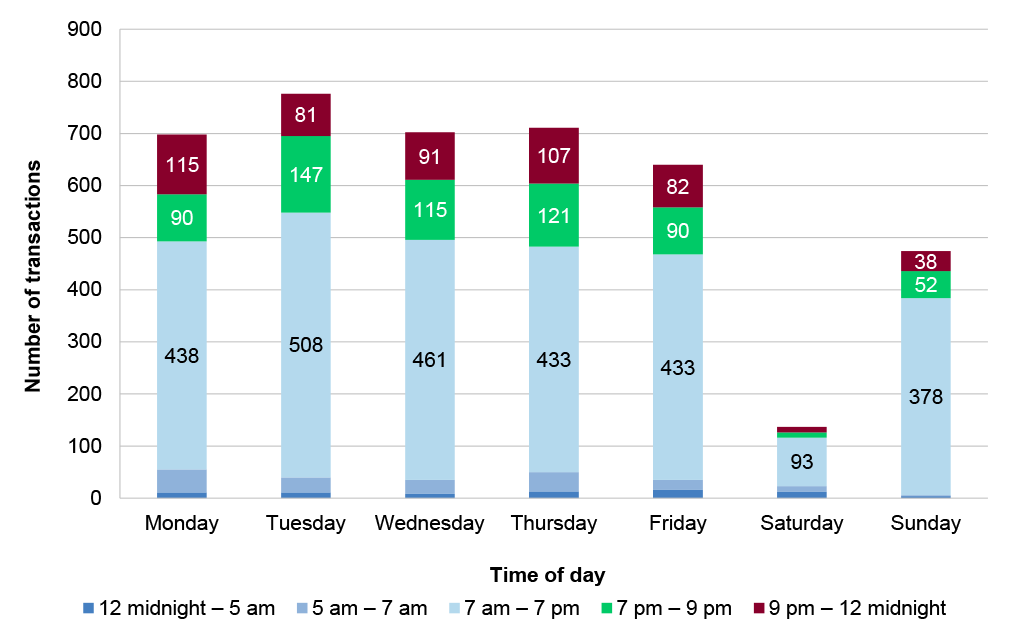

3.25 Analysis of the FCA’s CabCharge card transactions in 2021–22 and 2022–23 shows transactions were distributed across all days of the week and all hours of the day (see Figure 3.2 and Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.2: Day and time CabCharge transaction distribution 2021–22

Source: ANAO analysis of FCA data.

Figure 3.3: Day and time CabCharge transaction distribution 2022–23

Source: ANAO analysis of FCA data.

3.26 While there are potentially legitimate business reasons for taxi travel to occur on weekends and outside of normal business hours, the FCA’s lack of appropriate controls over CabCharge cards increases the risk that cards may be used inappropriately.

3.27 As noted in paragraph 2.53, the FCA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that it was seeking to implement a CabCharge acquittal process, which would include utilising the trip tagging functionality in CabCharge+. If this functionality was implemented, travellers would be prompted to log on after each trip, review their trip data and complete fields outlining: a declaration of business use; confirmation of the accuracy of the charge; a trip ID and/or purpose, and the name of an approver or pre-approver.

Recommendation no.4

3.28 The Federal Court of Australia establish a process to ensure evidence of pre-approval and receipts are recorded for all CabCharge card transactions.

Federal Court of Australia response: Agreed.

3.29 The Federal Court of Australia agrees that the current process to ensure evidence of pre-approval and receipts are recorded for all CabCharge card transactions could be strengthened by:

- reinforcing the requirement of documented delegate pre-approval through staff refresher training; and

- providing additional guidance on the existing acquittal process for recording of receipts for CabCharge transactions.

Return of cards