Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Compliance with Corporate Credit Card Requirements in the Productivity Commission

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit is one of a series of credit card audits to be tabled by the ANAO in 2023–24.

- The misuse of Australian Government credit cards, whether deliberate or not, has the potential for financial losses and reputational damage to government entities.

- The robustness of controls to detect and prevent misuse of credit cards and action taken on non-compliance are indicative of an entity’s culture and integrity.

- Previous ANAO audits have identified issues in other entities relating to positional authority in approvals of credit card transactions and ineffective controls in the management of the use of credit cards.

Key facts

- The Commission used 258 cards in the 2022–23 financial year: 23 procurement cards, 108 taxi cards, and 127 virtual travel cards.

- The Commission spent $1,029,292 in the 2022–23 financial year across procurement, taxi and travel cards.

What did we find?

- The Productivity Commission’s (the Commission’s) management of the use of corporate credit cards has been partly effective.

- The Commission had considered credit card risks and identified relevant controls. Its policies and procedures were largely fit for purpose but lacked detail on eligibility requirements and business needs. No structured training and education arrangements were in place. Monitoring and reporting on credit card use was not regular or systematic.

- Preventive controls were not effective in preventing non-compliant taxi card transactions. There were weaknesses in detective controls relating to the provision of supporting documentation when reconciling taxi transactions. The Commission had not documented its processes for escalating and managing identified non-compliance.

What did we recommend?

- There were six recommendations to the Commission relating to improving preventive and detective controls for credit cards.

- The Commission agreed to all recommendations.

12%

of the Commission’s workforce used a procurement credit card (intended for the purchase of general goods and services) between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

24

non-compliant purchases on taxi cards between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023 were identified by the ANAO.

2806

domestic travel transactions (including fees) were made on the Commission’s virtual travel cards between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide 206 defines a ‘corporate credit card’ as a credit card used by Commonwealth entities to obtain goods and services on credit.1 Credit cards are used by Commonwealth entities to support timely and efficient payment of suppliers for goods and services.2 For the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), credit cards include charge cards (such as VISA, Mastercard, Diners and American Express cards) and vendor cards (such as travel cards and fuel cards).

2. The Productivity Commission (the Commission) uses corporate credit cards for official purchases under $10,000, including for procurement, domestic taxi, and travel purposes. For 2021–22 and 2022–23, the Commission’s total credit card expenditure was approximately $1.5 million, comprising 6,884 transactions. Credit card expenditure represented 18 per cent of the Commission’s supplier expenses across the two years.3

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The misuse of corporate credit cards, whether deliberate or not, has the potential for financial losses and reputational damage to government entities and the Australian Public Service. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) states that:

establishing a pro-integrity culture at the institutional level means setting a culture that values, acknowledges and champions proactively doing the right thing, rather than purely a compliance-driven approach which focuses exclusively on avoidance of wrongdoing.4

4. In describing the role of Senior Executive Service (SES) officers, the APSC states that the SES ‘set the tone for workplace culture and expectations’, they ‘are viewed as role models of integrity’ and ‘are expected to foster a culture that makes it safe and straightforward for employees to do the right thing’.5 The New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption identifies organisational culture and expectations as a key element in preventing corruption and states:

[T]he way that an agency’s senior executives, middle managers and supervisors behave directly influences the conduct of staff by conveying expectations of how staff ought to act. This is something that affects an agency’s culture.6

5. Deliberate misuse of a corporate credit card is fraud. The National Anti-Corruption Commission’s Integrity Outlook 2022/23 identifies fraud, which includes the misuse of credit cards, as a key corruption and integrity vulnerability.7 The Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile indicates that credit cards are a common source of internal fraud risk. Previous audits have identified issues in other entities relating to positional authority for approving credit card transactions8 and ineffective controls to manage the use of credit cards.9 This audit was conducted to provide the Parliament with assurance that the Commission is effectively managing corporate credit cards in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

6. This audit is one of a series of compliance with credit card requirements that apply a standard methodology. The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2023–24 compliance with credit card requirements series are the:

- Productivity Commission (the Commission);

- Australian Research Council;

- Federal Court of Australia; and

- National Disability Insurance Agency.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Commission’s management of the use of corporate credit cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO examined:

- whether the Commission has effective arrangements in place to manage the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards; and

- whether the Commission has implemented effective controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures.

Conclusion

9. The Commission’s management of the use of corporate credit cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and entity requirements has been partly effective, as there were weaknesses in its implementation of preventive and detective controls and monitoring and reporting arrangements.

10. The Commission’s arrangements for managing the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards were partly effective. The Commission has considered risks associated with the use of corporate credit cards within its fraud control framework and identified relevant controls. Policies and procedures were largely fit for purpose, but eligibility criteria for issuing cards and information on providing supporting documentation for low value transactions (under $82.50) could be improved. The Commission did not have structured training and education arrangements in place to promote compliance with credit card policy and procedural requirements. The Commission’s credit card register was incomplete and inaccurate, and monitoring and reporting on credit card use was not regular and systematic. The Commission did not respond to Parliamentary questions on notice with accurate reporting on credit card use.

11. The Commission’s controls and processes for managing credit card issue, usage and return were partly effective in controlling the risk of credit card misuse. Preventive controls were not effective in preventing non-compliant taxi card transactions. There were weaknesses in detective controls relating to the provision of supporting documentation when reconciling taxi transactions. Positional authority risks could be better managed by clarifying delegation and approval requirements for senior executive cardholders. While the Commission has recovered funds from cardholders where instances of personal misuse have been identified, it has not documented its processes for escalating and managing identified non-compliance.

Supporting findings

Arrangements for managing corporate credit cards

12. The Commission had identified threats relating to credit card misuse and relevant controls in its fraud control plan. Assessment of these threats in the fraud risk register had not been informed by systematic controls testing. The Commission undertook an internal audit in 2022 that found significant gaps and weaknesses in its credit card controls and took action to address these findings. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.11)

13. The Commission’s policies and procedures for the issue, return and use of credit cards included coverage of core requirements within the Commission’s accountable authority instructions and other policies. Eligibility criteria for issuing credit cards and information on the need for supporting documentation for transactions under $82.50 could be improved. (See paragraphs 2.12 to 2.30)

14. While the Commission had published relevant policies and procedures on its intranet, it did not provide structured training and education to promote compliance with corporate credit card policy and procedural requirements. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.33)

15. The Commission’s cardholder register was incomplete and inaccurate and did not include sufficient details on the issue and return of cards. Reporting on the use of credit cards has occurred on an ad-hoc basis, with monitoring capability limited by the current financial management system in use. Detailed reporting on credit card non-compliance has not been provided to the Commission’s executive management, diminishing its understanding of fraud, risk and integrity implications arising from non-compliance. While the Commission reported on credit card issue and use when requested by Parliament, there were errors in its reporting. (See paragraphs 2.34 to 2.45)

Controls and processes for corporate credit cards

16. Preventive controls implemented by the Commission could be improved by strengthening visibility of cardholder spending and transaction limits. Preventive controls for hospitality and catering expenditure, purchases covered by whole-of-government arrangements, and to prevent non-compliant taxi card transactions were not operating effectively. Positional authority risks could be further managed through clarifying delegation and approval requirements for senior executive cardholders. (See paragraphs 3.4 to 3.30)

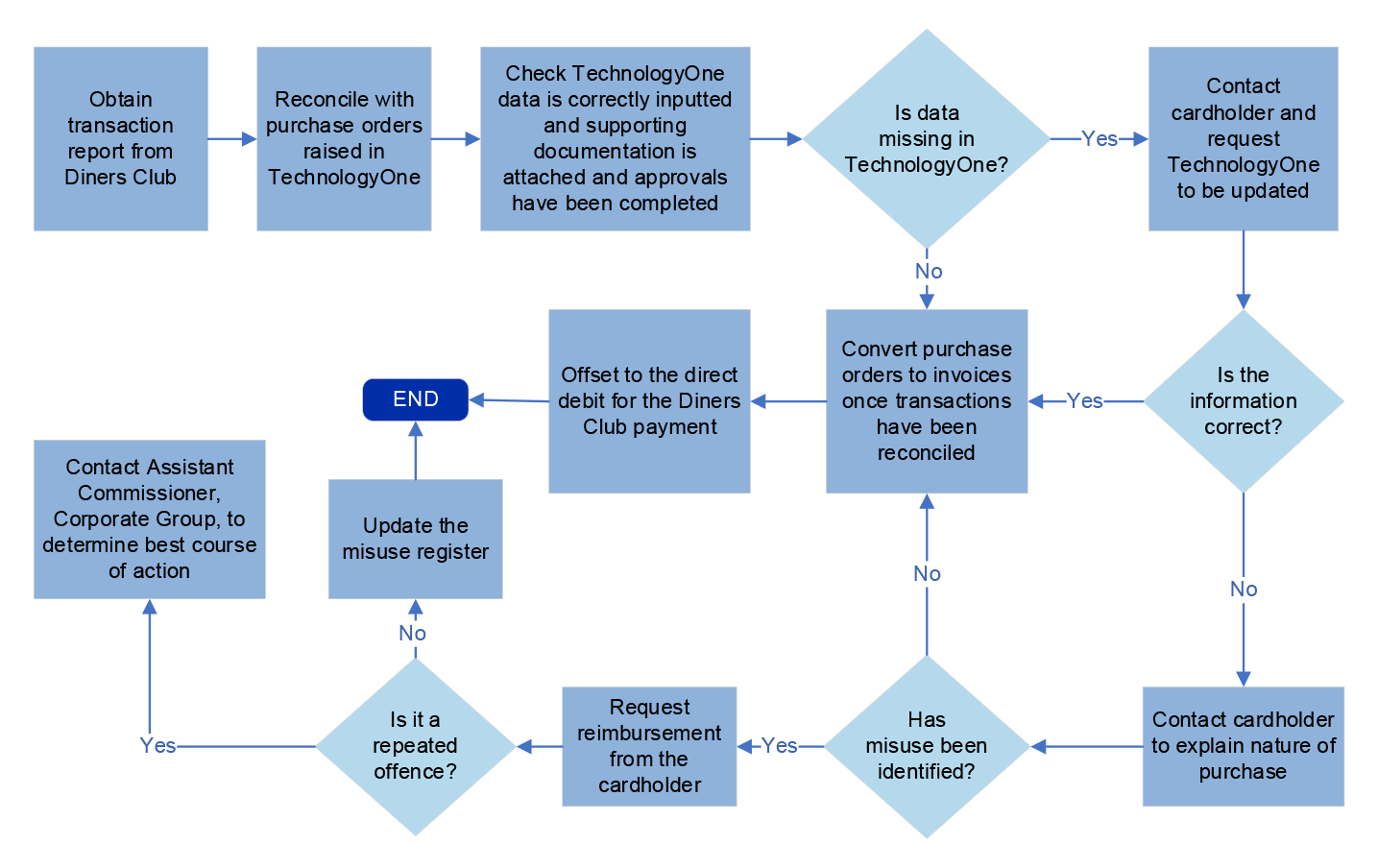

17. The Commission’s finance team reviews, acquits and verifies transactions manually each month. The Commission has not developed an approach to retaining and storing receipts for all taxi card transactions, which heightens the risk of errors, irregularities and fraud going undetected. (See paragraphs 3.31 to 3.41)

18. The Commission’s credit card control framework could be strengthened to ensure it identifies all potential instances of non-compliance. While the Commission has recovered funds from cardholders where instances of personal misuse have been identified, it has not documented its processes for escalating and managing identified non-compliance.(See paragraphs 3.43 to 3.50)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.16

The Productivity Commission update its policies and procedures for issuing credit cards to provide further guidance on eligibility criteria and applicable spending limits.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.36

The Productivity Commission implement a process to ensure its register of corporate credit cards:

- is up-to-date, complete and accurate; and

- includes appropriate details on the issue and return of cards and card limits in place.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.42

The Productivity Commission implement a systematic approach to reporting on corporate credit card issue, return and use to executive management on a periodic basis.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.23

The Productivity Commission establish arrangements to ensure corporate credit cards are only used for the purposes defined within its policy requirements.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.37

The Productivity Commission improve reconciliation of corporate credit card transactions by ensuring appropriate documentation is provided to approvers and the finance team as part of monthly reconciliation processes.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.50

The Productivity Commission document its process for managing identified instances of credit card non-compliance.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

19. The proposed audit report was provided to the Productivity Commission. The Commission’s summary response is reproduced below. Its full response is included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of the audit are listed at Appendix 2.

The Commission is committed to improving the management of corporate credit cards, agrees with all six recommendations put forward by the ANAO, and appreciates the additional improvement opportunities. The Commission acknowledges the work undertaken by the ANAO to prepare the report and their constructive engagement with us during the audit.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

20. This audit is part of a series of audits that applies a standard audit methodology to corporate credit card management in Commonwealth entities. The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2023–24 corporate credit card management series are the:

- Productivity Commission;

- Australian Research Council;

- Federal Court of Australia; and

- National Disability Insurance Agency.

21. Key messages from the ANAO’s series of credit card management audits will be outlined in an Insights product available on the ANAO website.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian Government entities use credit cards to support timely and efficient payment to suppliers of goods and services. ‘Corporate credit cards’ include charge cards (such as Visa, Mastercard, Diners Club and American Express cards) and vendor cards (such as travel and fuel cards).10 Other forms of credit used by Australian Government entities include credit vouchers (such as CabCharge e-tickets).

Australian Government framework for using credit cards

1.2 The Commonwealth Resource Management Framework governs how Australian Government entities use and manage public resources. The cornerstone of the framework is the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

1.3 Under section 56 of the PGPA Act, the Minister for Finance has delegated the power to enter into a limited range of borrowing agreements to the accountable authorities11 of non-corporate Commonwealth entities.12 This includes the power to enter into an agreement for the issue and use of credit cards, providing money borrowed is repaid within 90 days.

1.4 The PGPA Act sets out general duties of accountable authorities and officials of Australian Government entities. Relevant to credit card use, officials have a duty not to improperly use their positions to gain or seek to gain a benefit or advantage for themselves or others, or to cause detriment to the Commonwealth, entity, or others.13 Further, the duties of an accountable authority include:

- governing an entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources14; and

- establishing and maintaining appropriate systems of risk oversight and management and internal control, including measures to ensure officials comply with the finance law.15

1.5 Under subsection 20A(1) of the PGPA Act, an accountable authority may give instructions (referred to as accountable authority instructions) to entity officials about any matter relating to the finance law. The Department of Finance has published model accountable authority instructions, which include model instructions for the use of credit cards (see Box 1) as well as suggestions for additional instructions on credit card use.16

|

Box 1: Model accountable authority instructions for credit card use — non-corporate Commonwealth entities |

|

Only the person issued with a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, or someone specifically authorised by that person, may use that credit card, credit card number or credit voucher. You may only use a Commonwealth credit card or card number to obtain cash, goods or services for the Commonwealth entity based on the proper use of public resources. You cannot use a Commonwealth credit card or card number for private expenditure. In deciding whether to use a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must consider whether it would be the most cost-effective payment option in the circumstances. Before using a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must ensure that the requirements in the instructions Procurement, grants and other commitments and arrangements [a separate section of the model accountable authority instructions] have been met before entering into the arrangement. You must:

|

1.6 The PGPA Act and model accountable authority instructions include other content relevant to credit card use, particularly on spending public money, official hospitality, and official travel.

- Section 23 of the PGPA Act gives accountable authorities powers to approve commitments of ‘relevant money’ and enter into arrangements (which includes procuring goods and services with credit cards).17 Accountable authorities usually delegate these powers to entity officials, specifying delegation limits for officials in certain work groups based on their position and the category of spending. While the PGPA Act does not require separate and prior approval before entering into a spending arrangement, Section 18 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires officials with spending delegations to make a written record of their approval for a commitment as soon as practicable and to follow any directions or instructions of the accountable authority. The model accountable authority instructions suggest additional instructions could include: the circumstances in which approval is required; who has authority to approve different types of commitments; appropriate approval processes; and how to ensure spending commitments would be a proper use of public resources.

- Official hospitality involves using public resources — generally, by entering arrangements under section 23 of the PGPA Act — to provide hospitality to persons other than entity officials to support the achievement of Australian Government objectives. The model accountable authority instructions suggest additional instructions could include: what is considered official hospitality; who can approve it; recordkeeping and reporting processes; whether delegates can approve official hospitality if they may personally benefit from it; and whether alcohol can be provided and what rules, if any, apply to the provision of alcohol.

- When Australian Government officials travel for business purposes, they are generally required to use whole-of-government coordinated procurement arrangements. These arrangements encompass: domestic and international air services; travel management services; accommodation program management services; travel and card related services; and car rental services. Under the arrangements, entities must make payments for flights, domestic accommodation and car rental through an account with a credit provider.18 Entities can also allow their officials to use a ‘companion’ MasterCard (available through the Diners Club arrangement) to pay for meals, incidentals and general purchasing.

1.7 The Australian Government’s Supplier Pay On-Time or Pay Interest Policy requires non-corporate Commonwealth entities to make eligible payments valued under $10,000 by payment card (which includes by credit card), and to establish and maintain internal policies and processes to facilitate the timely payment of suppliers using payment cards.19 The policy also encourages payment card use for other payments (such as payments valued over $10,000).

Overview of the Productivity Commission

1.8 Under the PGPA Act, the Productivity Commission (the Commission) is classified as a non-corporate Commonwealth entity (a Commonwealth entity that is not a body corporate). The Chair of the Commission is the accountable authority. The Productivity Commission is an independent research and advisory body established to advise the Australian Government on a range of economic, social and environmental issues affecting the welfare of Australians.

1.9 The total staffing number for the Commission as of 30 June 2023 was 192 employees (including 175 ongoing and 17 non-ongoing employees). In addition, there were eleven Commissioners, including the Chair, and three Associate Commissioners. The Commission has office locations in Melbourne and Canberra.

Productivity Commission’s use of corporate credit cards

1.10 The Commission uses three types of corporate credit cards (managed by Diners Club):

- procurement cards (Mastercard) — for the purchase of goods and services;

- taxi cards (Mastercard) — for official domestic taxi travel and taxi alternatives; and

- travel cards (virtual) — for accommodation and flight bookings.

1.11 The Commission also uses supplementary CabCharge e-tickets in its Melbourne and Canberra offices for employees who travel infrequently.

1.12 The Commission’s expenditure on corporate credit cards in 2021–22 and 2022–23 is set out in Table 1.1. Credit card expenditure represented 18 per cent of the Commission’s supplier expenses across the two years.20 Ten out of the eleven Commissioners held a taxi and travel card, and no Commissioners held a procurement card.

Table 1.1: Credit cards in use, transactions and expenditure, 2021–22 and 2022–23

|

Card type |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||||

|

|

Cards in use |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

Cards in use |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

|

Procurement (Mastercard) |

15 |

567 |

$281,713 |

23 |

585 |

$358,897 |

|

Taxi (Mastercard) |

45 |

461 |

$18,739 |

108 |

1637 |

$73,900 |

|

Travel (virtual) |

75 |

828 |

$128,214 |

127 |

2806 |

$596,495 |

|

Total |

135 |

1856 |

$428,666 |

258 |

5028 |

$1,029,292 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Productivity Commission data.

1.13 Table 1.2 outlines the total number of vendors that received payments and the top five vendors based on transaction volume and expenditure.

Table 1.2: Procurement card usage by vendor

|

Financial year |

No. of vendors paid |

Top 5 vendors based on total expenditure |

Top 5 vendors based on transaction volume |

|

2021–22 |

211 |

Amazon Web Services ($57,071.49) The Hatchery Hub ($26,268.00) Zoom ($22,818.00) Fairfax Media GRP ($8,035.86) Microsoft ($6,415.77) |

LinkedIn (56) Twitter Online Ads (33) Amazon Web Services (23) CEDA (18) News Limited (15) |

|

2022–23 |

291 |

Amazon Web Services ($54,596.16) APSC ($36,650.00) Zoom ($22,818.00) Sticky Tickets PT ($20,650.00) The Hatchery Hub ($13,083.40) |

News Limited (39) Twitter Online Ads (25) Amazon Web Services (24) APSC (20) Asana.com (13) |

Source: ANAO analysis of Productivity Commission data.

1.14 Table 1.3 highlights spending analysis by transaction category for expenditure between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2023.

Table 1.3: Spend analysis by transaction category, 2021–22 to 2022–23

|

Categorya |

Procurement card |

Taxi card |

Travel (virtual) card |

|||

|

|

Amount ($)c |

% of totald |

Amount ($)c |

% of totald |

Amount ($)c |

% of totald |

|

Airlines |

4,662 |

0.7 |

1013 |

3.0 |

619,725 |

86.3 |

|

Car rental |

0 |

0.0 |

706 |

2.1 |

706 |

0.1 |

|

Gas/oil |

0 |

0.0 |

515 |

1.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Hotel |

5,929 |

0.9 |

210 |

0.6 |

97,650 |

13.6 |

|

Mail order |

2,154 |

0.3 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Vehicle hire |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Rail |

0 |

0.0 |

99 |

0.3 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Restaurant |

719 |

0.1 |

901 |

2.7 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Retail |

107,692 |

16.9 |

1,185 |

3.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Taxi/limousines |

0 |

0.0 |

13,356 |

40.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Telephone services |

45,636 |

7.2 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Otherb |

470,909 |

73.8 |

15,491 |

46.3 |

0 |

0.0 |

|

Total |

637,702 |

100.0 |

33,477 |

100.0 |

718,081 |

100.0 |

Note a: Expenditure categories are based on charge types identified in the Diners Club transaction data. Transactions categorised as Adjustments were not included in the figures. The total of the Adjustments was $95,408.

Note b: Most expenditure classified as ‘other’ was for parking.

Note c: Figures have been rounded to the nearest dollar.

Note d: Figures do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of Productivity Commission data.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.15 The misuse of corporate credit cards, whether deliberate or not, has the potential for financial losses and reputational damage to government entities and to the Australian Public Service. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) states that:

establishing a pro-integrity culture at the institutional level means setting a culture that values, acknowledges and champions proactively doing the right thing, rather than purely a compliance-driven approach which focuses exclusively on avoidance of wrong doing.21

1.16 In describing the role of Senior Executive Service (SES) officers, the APSC states that the SES ‘set the tone for workplace culture and expectations’, they ‘are viewed as role models of integrity’ and ‘are expected to foster a culture that makes it safe and straightforward for employees to do the right thing’.22 The New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption identifies organisational culture and expectations as a key element in preventing corruption and states:

[T]he way that an agency’s senior executives, middle managers and supervisors behave directly influences the conduct of staff by conveying expectations of how staff ought to act. This is something that affects an agency’s culture.23

1.17 Deliberate misuse of a corporate credit card is fraud. The Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile indicates that credit cards are a common source of internal fraud risk. Previous audits have identified issues in other entities relating to positional authority for approving credit card transactions24 and ineffective controls to manage the use of credit cards.25 This audit was conducted to provide the Parliament with assurance that the Commission is effectively managing corporate credit cards in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Commission’s management of the use of corporate credit cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and entity requirements.

1.19 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO examined:

- whether the Commission has effective arrangements in place to manage the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards; and

- whether the Commission has implemented effective controls and processes for corporate credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures.

1.20 The audit focused on the Commission’s management and use of credit cards, including travel approval and acquittals, in the 2021–22 and 2022–23 financial years.

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit methodology included:

- review of legislative and entity frameworks guiding the use of corporate credit cards;

- review of the Commission’s documentation, including policies and procedures, risks registers, training material and reporting;

- analysis of the Commission’s data, including publicly reported information and data obtained during the audit; and

- meetings with Commission staff.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $245,000.

1.23 The team members for this audit were Hayley Tonkin, Priyanka Varma, Brinlea Paine and Daniel Whyte.

2. Arrangements for managing corporate credit cards

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Productivity Commission (the Commission) had effective arrangements in place to manage the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards.

Conclusion

The Commission’s arrangements for managing the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards were partly effective. The Commission has considered risks associated with the use of corporate credit cards within its fraud control framework and identified relevant controls. Policies and procedures were largely fit for purpose, but eligibility criteria for issuing cards and information on providing supporting documentation for low value transactions (under $82.50) could be improved. The Commission did not have structured training and education arrangements in place to promote compliance with credit card policy and procedural requirements. The Commission’s credit card register was incomplete and inaccurate, and monitoring and reporting on credit card use was not regular and systematic. The Commission did not respond to Parliamentary questions on notice with accurate reporting on credit card use.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: ensuring the Commission’s policies and procedures include eligibility criteria for issuing cards and spending limits (paragraph 2.16); ensuring the cardholder register is complete and accurate (paragraph 2.36); and establishing appropriate reporting arrangements to executive management (paragraph 2.42).

The ANAO identified three opportunities for improvement for the Commission to: strengthen its fraud control testing (paragraph 2.8); improve the clarity of its policies and procedures relating to supporting documentation for low value transactions (paragraph 2.23); and periodically provide educational messaging to cardholders and managers (paragraph 2.33).

2.1 If Australian Government officials deliberately misuse corporate credit cards, they are committing fraud. Other risks of credit card use include: inadvertent personal use; unauthorised or inappropriate work use; incorrect charging by merchants; and external fraud enabled by stolen credit card details.

2.2 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), an accountable authority of an Australian Government entity has a duty to establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight and management and internal control, including measures to ensure that officials comply with the finance law.26

2.3 In addition, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) establishes a requirement for an accountable authority to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity.27 Specific requirements of the Fraud Rule include:

- conducting regular fraud risk assessments and developing and implementing a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks;

- establishing appropriate preventive controls (which should include fit-for-purpose policies and procedures and effective training and education arrangements); and

- establishing appropriate monitoring and reporting arrangements.

Have appropriate arrangements been established for managing risks associated with use of corporate credit cards within the Productivity Commission?

The Commission had identified threats relating to credit card misuse and relevant controls in its fraud control plan. Assessment of these threats in the fraud risk register had not been informed by systematic controls testing. The Commission undertook an internal audit in 2022 that found significant gaps and weaknesses in its credit card controls and took action to address these findings.

Enterprise risk management arrangements

2.4 The Commission has a draft Enterprise Risk Management Framework (last updated in November 2023) that includes risk assessments for its four enterprise risks.28 Risks relating to credit card use and travel are described in the framework as ‘other operational risks where the rating is considered low, after taking account of control measures’. There was no evidence of the Commission’s control assessment to support the ‘low’ risk rating.

Fraud Control Plan

2.5 The Commission’s Fraud Control Plan (last updated in November 2022) identifies two fraud threats related to credit cards: unauthorised use of official credit cards by non-Commission staff; and purchases made for personal gain. The plan also identifies three fraud threats related to travel, which are relevant to the use of travel and taxi cards: unnecessary or extended travel; overpayment of travel allowance; and inappropriate use of taxi card facilities. Table 2.1 outlines the existing controls identified in the plan to address these credit card and travel threats.

Table 2.1: Fraud threats and controls related to credit card use identified in the Commission’s 2022 Fraud Control Plan

|

Category |

Potential fraud threat |

Existing controls |

|

Credit card |

Unauthorised use of official credit cards by non-Commission staff |

|

|

Purchases made for personal gain |

||

|

Travel |

Unnecessary or extended travel |

|

|

Overpayment of travel allowance |

|

|

|

Inappropriate use of taxi card facilities |

|

|

Source: Productivity Commission, Fraud Control Plan, November 2022.

2.6 The 2022 Fraud Control Plan includes a risk register that assesses the inherent risk, control strength and residual risk for four of the five fraud threats related to credit card use (inappropriate use of taxi card facilities was not included in the register). All four threats were rated as ‘low’ inherent risk, with ‘good’ control strength and ‘low’ residual risk. The Commission’s Finance Director was identified as the risk owner for the four threats.

2.7 The Commission advised the ANAO in March 2024 that, while fraud risk control testing had not been documented, the risk management approach outlined in the Enterprise Risk Management Framework was followed to identify, analyse, assess and prioritise risks and controls. In the absence of robust control testing, deficiencies and potential improvements of existing controls may go unaddressed, resulting in controls not achieving their intended purpose in preventing and detecting fraud.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.8 Fraud control testing involves various methods including desktop reviews, system or process walkthroughs, data analysis, sample testing and pressure testing. The Commission could strengthen its fraud control framework by employing different testing methods and better documenting testing outcomes. |

Audit and risk committee consideration

2.9 The Commission engaged Pitt Group to undertake an internal audit of key financial controls that was completed in June 2022. The internal audit identified ‘significant gaps and weaknesses in the controls used to manage the Commission’s use of credit cards’, including the following key issues:

- a lack of documented procedures for the management of credit cards;

- credit cards being obtained for staff without prior confirmation of business needs;

- no credit card register being maintained with information on cardholders, credit limits and locations of cards; and

- no processes in place to review cardholders and credit limits.

2.10 The internal audit identified five ‘agreed actions’ to be implemented by December 2022:

Document processes for managing virtual credit cards, taxi cards and procurement cards

Establish a process for credit card requests and approvals to ensure cards are only issued where there is a clear business need

Establish a cardholder register to record key details associated with each card and cardholder

Review current virtual credit cards, taxi cards and procurement cards to determine if there is a continued business need for them

Schedule periodic reviews of the cardholder register to ensure currency of data and that staff issued cards have an ongoing business need.

2.11 Reporting to the Commission’s Audit and Risk Committee from November 2023 recorded all agreed actions as ‘closed’. The first three actions were noted as completed in May 2023 with the development of the Commission’s Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure and a cardholder register. The review of business needs was noted as completed in October 2023, and the periodic reviews were noted as underway.29

Has the Productivity Commission developed fit-for-purpose policies and procedures for the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards?

The Commission’s policies and procedures for the issue, return and use of credit cards included coverage of core requirements within the Commission’s accountable authority instructions and other policies. Eligibility criteria for issuing credit cards and information on the need for supporting documentation for transactions under $82.50 could be improved.

Issue

2.12 The June 2022 internal audit of key financial controls (see paragraphs 2.9 to 2.11) found the Commission’s processes for allocating taxi and travel cards did not consider employees’ roles and associated travel requirements and it recommended establishing a process for only issuing cards when there is a clear business need.

2.13 The Commission’s Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure (March 2023), which was developed in response to the internal audit, states that the Chair, Commissioners, and Senior Executive Service (SES) and Executive Level 2 (EL2) employees are eligible for taxi and travel cards, and all other employees will be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Card limits documented in the policy for the Chair, Commissioners, SES and EL2 employees were: $3000 per month and $300 per transaction for taxi cards; and no limit for virtual travel cards.

2.14 No criteria were documented in the policy for assessing other employees’ eligibility for these cards or applicable spending limits. There were also no eligibility criteria or applicable spending limits for procurement cards.

2.15 In March 2024 the Commission provided the ANAO a draft list of criteria that the finance team uses to assess credit card eligibility and advised that it would update its policy and procedures to provide more guidance regarding what factors should be considered when assessing business need.

Recommendation no.1

2.16 The Productivity Commission update its policies and procedures for issuing credit cards to provide further guidance on eligibility criteria and applicable spending limits.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

2.17 The Commission accepts the recommendation and has established further guidance on eligibility and spending limits when considering issuing a credit card.

Use

Accountable Authority Instructions

2.18 The Commission’s Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) (August 2023) include the Department of Finance’s model instructions for credit cards outlined at Box 1 in Chapter 1. The AAIs provide additional instructions for the use of credit cards, including:

The Commonwealth credit card must not be used for:

- Linking to an iTunes account.

- Cash advances (unless express written authorisation has been provided by the Head of Office).

A tax invoice must be obtained for all expenditures over $82.50. A receipt or credit card docket is acceptable for purchases less than $82.50 unless it is not possible to obtain appropriate documentation (e.g. for an overseas taxi fare). Where a credit card holder cannot provide the required documentation, a statutory declaration is required detailing the expenditure and an explanation of why the documentation cannot be provided.

2.19 The Commission’s AAIs also contain instructions for all officials on procurement, official hospitality, business catering and official travel, which are relevant to credit card use, including:

You must … use any mandated whole-of-government [procurement] arrangement …30

Any decision to spend relevant money on official hospitality must be publicly defensible.

Business catering is the provision of food or beverages to Productivity Commission staff, contractors, or Commissioners associated with meetings, seminars, conferences, training, and other events and may be provided when:

- The expenditure would be publicly defensible.

- An appropriate delegate has approved the expenditure.

Where the government has established coordinated procurements for a particular travel activity, you must use the arrangement established for that activity unless:

- an exemption has been provided in accordance with the CPRs, or reimbursement is to be provided to a third party (i.e. a non-Commonwealth traveller that cannot access coordinated travel procurements) for airfares, accommodation and/or car rental; or

- a travel allowance is to be provided for accommodation arrangements.

2.20 The Commission’s AAIs outline that for taxi (or taxi type travel) expenditure there is a limit of $300 (GST inclusive) per journey.

Corporate Credit Card Policy and Procedure

2.21 The March 2023 Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure includes appendices outlining cardholder responsibilities and including copies of the cardholder agreements that must be signed when employees are issued with procurement and taxi cards (key requirements from these appendices are outlined in Box 2).

|

Box 2: Key requirements for credit card use from the Commission’s Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure |

|

All cardholders must:

In addition, taxi card holders must:

|

2.22 While the cardholder responsibilities appendix states that itemised tax invoices must be obtained for all purchases, in a different section the policy states that employees must obtain a tax invoice for transactions above $82.50 (including GST). The policy does not include reference to the requirement in the AAIs to obtain receipts or credit card dockets for purchases less than $82.50, or to provide a statutory declaration where documentation cannot be provided.31

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.23 To help ensure cardholders and managers comply with credit cards policies and procedures, the requirements for obtaining receipts and tax invoices or providing statutory declarations outlined in the Commission’s AAIs could be replicated in its Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure. |

2.24 If there is no movement requisition for approved travel, the policy states that cardholders are responsible for providing supporting documentation to the finance team in a timely manner to enable the finance team to reconcile monthly transactions. The policy also states that Melbourne SES employees are permitted to use their taxi cards to pay for commercial parking near the Commission’s Melbourne office. After the ANAO enquired about the fringe benefit tax (FBT) implications of this arrangement, the Commission informed the ANAO in May 2024 that it had made an FBT reporting error in its 2022–23 tax return and was planning to amend the return and pay the amount owing.32

Travel Guidelines

2.25 In addition to the AAIs and Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure, the Commission has established Travel Guidelines (November 2023) that set out key considerations, arrangements and processes to follow when arranging staff travel. The Travel Guidelines state that:

Many Commission staff are issued with a Mastercard to pay for official taxi and ride-share travel. The card can also be used for official travel related costs (e.g. airport parking, sky bus).

The Mastercard may be used for all official journeys (e.g. between home/office and airports, between accommodation and airport when travelling overnight, to/from visits or meetings, to home after approved overtime or working late).

For travel related to [a movement requisition], travellers should obtain receipts/tax invoices and retain them for one month post travel. The Finance team reconcile corporate credit card expenses monthly and may request the receipts.

Use of credit cards for purchases over $10,000

2.26 As noted at paragraph 1.7, the Australian Government’s Supplier Pay On-Time or Pay Interest Policy requires non-corporate Commonwealth entities to make eligible payments valued under $10,000 by payment card (which includes by credit card), and to establish and maintain internal policies and processes to facilitate the timely payment of suppliers using payment cards. The Commission has incorporated this requirement into its Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure and its AAIs.

2.27 Table 2.2 provides accounts payable data and credit card transaction data from 2021–22 and 2022–23. In 2022–23 the Commission made over three times as many transactions under $10,000 using credit cards than it did through its accounts payable function.

Table 2.2: Accounts payable and credit card expenditure transactions under $10,000

|

Payment type |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||

|

|

No. of transactions under $10,000 |

Expenditure |

No. of transactions under $10,000 |

Expenditure |

|

Accounts payable |

1594 |

$1,063,773 |

1567 |

$1,361,325 |

|

Credit cards |

1850 |

$444,677 |

5120 |

$1,210,716 |

Source: ANAO analysis based on accounts payable data provided by the Productivity Commission.

2.28 Some accounts payable transactions cannot be paid by credit card (such as travel allowances, staff reimbursements, large account and milestone payments, or payments to individuals or sole traders without a credit card facility).

Return

2.29 The Commission’s Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure states that a card should be returned if a cardholder:

- resigns from the Commission;

- is transferred or promoted to another position or agency; or

- is instructed to do so by the card issuing officer.

2.30 The policy and procedure stipulates that cardholders should immediately report loss or theft of cards to the government premium service team, finance team and card issuing officer. The finance team is responsible for overseeing and managing the cancellation of cards.

Has the Productivity Commission developed effective training and education arrangements to promote compliance with policy and procedural requirements?

While the Commission had published relevant policies and procedures on its intranet, it did not provide structured training and education to promote compliance with corporate credit card policy and procedural requirements.

Intranet guidance

2.31 Guidance materials are available to staff on the Commission’s intranet. In addition to the AAIs, Corporate Credit Card Policy and Procedure and Travel Guidelines, intranet guidance includes:

- Guide to Creating a Travel Requisition (September 2023) — which outlines how staff should use TechnologyOne to raise a requisition and gain appropriate delegate approval for travel related procurement, including airfare, accommodation and car rental expenses. It documents the process for raising movement requests, amending purchases, and releasing purchase orders.

- Guide to Creating a Credit Card Transaction (September 2023) — which details the process for cardholders to acquit their transactions by raising credit card requisitions in TechnologyOne.

- Purchase Approval Guide (undated) — which provides instructions for obtaining and documenting expenditure approvals. This includes separate instructions for low-cost, mid-value, and hospitality and catering transactions.

Other training

2.32 The Commission advised the ANAO in November 2023 that all staff must complete a finance induction training session with the Finance Director, who can provide further tailored credit card training as required. There was no evidence of these induction training sessions other than a presentation for graduates and a reference outlining key financial resources available through the intranet. These materials did not include any content related to corporate credit card policy and procedural requirements.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.33 To ensure cardholders and managers comply with policy and procedural requirements for all credit card types, the Commission could periodically provide training and/or messaging that outlines good practices and raises awareness of fraud and non-compliance risks. This could be through intranet posts, messages within all staff email, or reminders at staff meetings. |

Does the Productivity Commission have appropriate arrangements for monitoring and reporting on the issue, return and use of corporate credit cards?

The Commission’s cardholder register was incomplete and inaccurate and did not include sufficient details on the issue and return of cards. Reporting on the use of credit cards has occurred on an ad-hoc basis, with monitoring capability limited by the current financial management system in use. Detailed reporting on credit card non-compliance has not been provided to the Commission’s executive management, diminishing its understanding of fraud, risk and integrity implications arising from non-compliance. While the Commission reported on credit card issue and use when requested by Parliament, there were errors in its reporting.

Monitoring issue and return

2.34 The June 2022 internal audit of key financial controls (see paragraphs 2.9 to 2.11) identified that the Commission did not have a credit card register that contained information such as the name of credit card holders, credit limits and location of cards. To address this finding, the Commission committed to establish a cardholder register. The action was closed in April 2023.

2.35 In response to the internal audit, the Commission established a consolidated cardholder register for all three credit card types. As of December 2023, a total of 330 card numbers were recorded in the cardholder register, held by 152 cardholders. There were no details in the register to match cardholders with their roles and delegation limits, card type and transaction limits (for virtual travel cards). In addition, the register was not complete and accurate, as ANAO analysis of 2022–23 credit card transactions identified 72 card numbers that were used in 2022–23 by the Commission that were not recorded in its register. Some cardholders in the register did not have card numbers recorded, which the Commission advised the ANAO in March 2024 was due to manual error by staff when inputting data.

Recommendation no.2

2.36 The Productivity Commission implement a process to ensure its register of corporate credit cards:

- is up-to-date, complete and accurate; and

- includes appropriate details on the issue and return of cards and card limits in place.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

2.37 The Commission accepts the recommendation and will implement the requirements to ensure that the credit card register is accurate and includes all information on issue, return and credit limits.

Monitoring use and reporting

2.38 The Commission uses monthly reports produced by its credit card provider (Diners Club) and its financial management system (TechnologyOne) to reconcile transactions. While the Commission’s finance team draws reports from these systems for acquittal purposes, the information is not used to produce management reporting on a regular basis. There was no regular reporting to the Commission’s executive management on credit issue, return or use, or non-compliance and actions taken in response to non-compliance. This reduces executive management’s visibility of non-compliance and the effectiveness of internal controls, impacting its ability to understand and manage fraud and integrity risks.

2.39 The Commission advised the ANAO in January 2024 that the outcomes of the credit card monthly reconciliation process were reported to the Assistant Commissioner, Corporate Group when requested for Senates Estimates hearings or when the finance team identified a possible issue requiring notification.

2.40 The Commission advised the ANAO in November 2023 that there were inefficiencies with its existing system, and it was looking to implement a new solution to centralise credit card reconciliation, acquittals, monitoring and reporting capability. The Commission developed a draft proposal to amend the credit card process in January 2024, which outlines current problems with credit card management, including:

- staff automatically receiving taxi cards without a business need;

- unnecessary duplications of cards;

- cards not being activated or distributed;

- considerable time spend acquitting statements as software is not fit for purpose; and

- lack of supporting data due to software restraints.

2.41 The draft proposal recommends that the Commission consolidate cards to one physical card and one virtual card, and implement a new financial management system to process transactions. While the Commission’s executive leadership was aware of the proposed changes to credit card operations, as of April 2024 the proposal had not been finalised or approved.

Recommendation no.3

2.42 The Productivity Commission implement a systematic approach to reporting on corporate credit card issue, return and use to executive management on a periodic basis.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

2.43 The Commission agrees to the recommendation and has incorporated reporting on card issues, returns and misuse into the monthly Finance paper to the Executive.

Reporting to Parliament on corporate credit card issue and use

2.44 The Commission provided responses to questions on notice on the issue and use of credit cards that were asked of the Treasury Portfolio in Senate Estimates hearings in 2022–23 and 2023–24. The Commission’s responses to these questions are outlined in Table 2.3 (see Appendix 3 for the complete set of questions).

Table 2.3: Responses to Senate Estimates questions on notice on credit cards

|

Question |

2022–23 Suppl. Budget estimates (asked 3/03/23) |

2022–23 Budget estimates (asked 16/06/23) |

2023–24 Suppl. Budget estimates (asked 3/11/23) |

|

Period covered by answer |

2022–23 financial year to date |

1/07/22–31/05/23 |

1/07/23–31/10/23 |

|

Number of cards on issuea |

142 |

145 |

97 |

|

Largest reported purchase |

$8,478.35 |

$8,478.35 |

$12,142.49 |

|

No. of cards reported lost or stolen |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

No. of purchases deemed illegitimate or contrary to policy |

27 |

32 |

12 |

|

Amount of illegitimate or contrary to policy purchases |

$622.44 |

$716.80 |

$204.31 |

|

Amount repaid |

$622.44 |

$716.80 |

$204.31 |

|

Highest value illegitimate or contrary to policy purchase repaid |

$51.24 |

$64.50 |

$81.08 |

Note a: The Commission reported on the number of taxi and procurement cards on issue.

Source: Senate estimates question on notice database.

2.45 The Commission interpreted ‘illegitimate or contrary to policy’ to be staff misuse and fraudulent transactions. The Commission’s process for preparing the responses was to examine its credit card register and general ledger for relevant transactions. Two fraudulent transactions in 2022–23 (two Quizlet transactions with a total value of $19.98) were not included in the Commission’s responses to the questions asked on 3 March 2023 and 19 June 2023.

3. Controls and processes for corporate credit cards

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Productivity Commission (the Commission) has implemented effective controls and processes for credit cards in accordance with its policies and procedures.

Conclusion

The Commission’s controls and processes for managing credit card issue, usage and return were partly effective in controlling the risk of credit card misuse. Preventive controls were not effective in preventing non-compliant taxi card transactions. There were weaknesses in detective controls relating to the provision of supporting documentation when reconciling taxi transactions. Positional authority risks could be better managed by clarifying delegation and approval requirements for senior executive cardholders. While the Commission has recovered funds from cardholders where instances of personal misuse have been identified, it has not documented its processes for escalating and managing identified non-compliance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: improving controls to prevent non-compliant credit card use (paragraph 3.23); increasing documentation requirements for monthly reconciliations (paragraph 3.37); and documenting processes for managing identified instances of non-compliance (paragraph 3.50).

The ANAO also identified three opportunities for improvement for the Commission to: establish a systematic approach to assessing and recording business needs for issuing credit cards (paragraph 3.7); maintain a complete and accurate record of monthly spending and individual transaction limits (paragraph 3.11); and clarify approval requirements and delegations for senior executive cardholders, and official hospitality and catering purchases (paragraph 3.20).

3.1 Preventive controls work by reducing the likelihood of inappropriate credit card use before a transaction has been completed. Preventive controls for credit cards can include: policies and procedures; education and training; deterrence messaging; declarations and acknowledgements; blocking certain categories of merchants; issuing cards only to those with an established business need; placing limits on available credit; and limiting the availability of cash advances.

3.2 Detective controls work after a credit card transaction has occurred by identifying if there is a risk that it may have been inappropriate. Detective controls for credit cards can include: regular reconciliation processes (with segregation of duties between cardholder and approver); exception reporting; fraud detection software; tip-offs and public interest disclosures; monitoring and reporting; and audits and reviews.

3.3 When detective controls identify instances of fraud or non-compliance, entities should have effective processes in place for managing investigations and follow-up actions (such as further training, sanctions, or referral to law enforcement agencies).

Has the Productivity Commission implemented effective preventive controls on the use of corporate credit cards?

Preventive controls implemented by the Commission could be improved by strengthening visibility of cardholder spending and transaction limits. Preventive controls for hospitality and catering expenditure, purchases covered by whole-of-government arrangements, and to prevent non-compliant taxi card transactions were not operating effectively. Positional authority risks could be further managed through clarifying delegation and approval requirements for senior executive cardholders.

Issuing credit cards

3.4 Issuing corporate credit cards to staff with an established business need is a key preventive control to reduce the risk of inappropriate use.

3.5 The June 2022 internal audit of key financial controls (see paragraphs 2.9 to 2.11) identified that credit cards were obtained for Commission staff without prior confirmation of a business need (although cards obtained were not always provided to staff). In response, the Commission committed to review current corporate credit cards to determine if there was a continuing need for them, and schedule periodic reviews of ongoing business needs. The first action was closed in October 2023, noting that a preliminary review of credit card utilisation had been completed and further action was delayed until the implementation of a new credit card provider in 2024. The second action was closed in April 2023, noting that a quarterly review schedule had been implemented by the finance team.

3.6 The Commission provided four emails between the finance team and cardholder managers from October 2023 as evidence of its a review of the cardholder register. The emails noted that the finance team was seeking to determine if corporate cards held in the safe were still required. The Commission had not completed subsequent quarterly reviews.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

3.7 The Commission could establish a more systematic approach to assessing and recording business needs for issuing credit cards and undertake a thorough review of the ongoing business needs of existing cardholders. |

Managing transactions

Credit card spending limits

3.8 As noted in paragraph 2.13, the Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure identifies that limits of $3,000 per month and $300 per transaction apply for taxi cards issued to the Chair, Commissioners, Senior Executive Service (SES) and Executive Level 2 employees and no limits apply to their virtual travel cards. The policy does not define any limits for procurement cards or taxi and travel cards held by other staff.

3.9 Limits for taxi cards had generally been adhered to, with one non-compliant airline transaction exceeding the $300 individual transaction limit, which the Commission attributed to a Diners Club administration error (non-compliant taxi card purchases are discussed at paragraphs 3.21 and 3.22).

3.10 As noted at paragraph 2.35, the Commission does not have a complete cardholder register that records cardholders’ monthly spending and individual transaction limits for other card types. This control weakness impedes the ability of the Commission to monitor adherence with spending limits for procurement cards. The Commission advised the ANAO in March 2024 that the credit card limit report can be downloaded from the Diners Club system anytime. Documenting assigned monthly and individual transaction spending limits within a register is an important control to ensure cards have been set up correctly by the credit provider, in alignment with entity delegations and guidance, as well as to facilitate assurance activities.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

3.11 The Commission could establish a process to ensure that it has a complete and accurate record of monthly spending and individual transaction limits for all credit card types, and that limits align with the Commission’s delegations instrument. |

Pre-approval for credit card purchases

3.12 Pre-approval and documentation of rationale for expenditure is a key control to ensure purchases are appropriate and can withstand public scrutiny.

Purchases covered by whole of Australian Government arrangements

3.13 As noted at paragraph 2.19, the Commission’s Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) state that staff must ‘use any mandated whole-of-government [procurement] arrangement’ (such as arrangements established by the Department of Finance and Digital Transformation Agency for accommodation and travel services, stationery and office supplies, and ICT equipment).

3.14 Analysis of the Commission’s credit card transactions shows there were transactions in categories covered by mandatory coordinated procurement arrangements in 2022–23 (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Transactions not using whole-of-government arrangements in 2022–23

|

Merchant |

Category |

Number of transactions |

Sum of transaction value |

|

Apple |

ICT equipment |

4 |

$9,053.90 |

|

Officeworks |

Stationery and office supplies |

5 |

$302.25 |

|

Ergonomic Office |

Stationery and office supplies |

4 |

$610.00 |

|

Enterprise Rent a Car |

Car rental services |

2 |

$904.07 |

Source: ANAO analysis based on transaction data provided from the Productivity Commission.

3.15 The Commission provided a rationale to the ANAO in March 2024 for each of the identified transactions where coordinated procurement arrangements were not used.

- For Apple charges, three transactions were originally placed through the panel, but Apple cancelled orders through the reseller to prioritise fulfilling direct orders. The other transaction was for an urgent repair that was deemed to be cheaper to repair directly through Apple. There was supporting documentation for three of the four transactions.

- Both car rental transactions were for rental cars in remote locations not covered by whole-of-government providers. There was supporting documentation for both transactions in the form of email correspondence and receipts.

- For the nine stationery and office supplies transactions, expenditure was for ergonomic equipment that was not available through the coordinated procurement arrangements or required immediately.

- For the four transactions from Ergonomic Office, there was documentation noting that the whole-of-government supplier did not supply the product required in three instances, and that urgent delivery was required for the other purchase.

- For the five transactions from Officeworks, two transactions were supported by documentation justifying the purchases. These purchases were made in relation to equipment recommended in Workstation Assessment Reports, which was not available through the whole-of-government supplier. Supporting documentation was not provided for the remaining three transactions. The Commission advised in March 2024 that the items were for ergonomic equipment either not available from the whole-of-government supplier or required immediately.

Official hospitality and business catering expenditure

3.16 As noted at paragraph 2.19, the Commission’s AAIs state that decisions to spend relevant money on official hospitality and business catering must be publicly defensible. In addition, the AAIs note that to enter into an arrangement to provide official hospitality, employees must be delegated the power to enter an arrangement, act in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, and complete an official hospitality form for fringe benefit tax requirements.

3.17 The Commission’s AAIs and Delegations Instrument do not define or limit who has a delegation to authorise expenditure on official hospitality related goods and services. The only references to delegations are on the Commission’s hospitality and catering form. The form identifies expenditure relating to social functions, restaurant meals, business meetings with lunch and employee achievement functions as hospitality expenses that can only be approved by the Head of Office (SES Band 3) or the Chair. For catering expenditure (morning and afternoon teas and light lunches), the form notes ‘current delegations apply’. The Commission advised the ANAO in April 2024 that:

The intent of the wording on the hospitality form is to guide the admin staff and not a delegation listed in our AAI.

3.18 The Commission’s credit card transactions in 2021–22 and 2022–23 shows there were a low number of transactions on food and beverage related transactions (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.2: Food and beverage related credit card expenditure, 2021–22 and 2022–23

|

Category |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

||

|

|

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

No. of transactions |

Expenditure |

|

Liquor store |

0 |

$0.00 |

1 |

$77.20 |

|

Restaurant/café |

10 |

$939.99 |

9 |

$1345.39 |

|

Supermarket |

20 |

$741.77 |

14 |

$747.55 |

|

Total |

30 |

$1,681.76 |

24 |

$2,170.14 |

Source: ANAO analysis based on data provided from the Productivity Commission.

3.19 The ANAO conducted targeted testing on ten food and beverage related transactions from 2022–23. Based on supporting documentation, the purchases were for: a social function (1); catering for internal events (coffee, bakery and supermarket purchases) (4); a restaurant meal (1); food items for an interstate trip (1); and attendance at external events including lunch (3).

- The one hospitality transaction for a social function (a seminar for internal and external participants) involved purchasing alcohol from a liquor store. It was supported by an itemised receipt, hospitality and catering form and documentation confirming attendees for the event. The purchase was pre-approved by a First Assistant Commissioner (SES Band 2) and advice was sought from the finance team prior to the purchase being made. As noted in paragraph 3.17, the Commission has not clearly defined who is delegated to authorise expenditure on official hospitality.

- Three of the four catering transactions were supported by hospitality and catering forms and emails confirming purchase pre-approval. The fourth transaction was a $73 purchase made by the Head of Office on 13 April 2023 (to buy coffees for Commissioners whilst visiting Melbourne). The transaction was not raised in TechnologyOne and did not have a supporting receipt retained. The Commission informed the ANAO in April 2024 that the Head of Office acknowledged this purchase was non-compliant and repaid the transaction on 17 April 2024. There was no pre- or post-approval recorded for this transaction. Under the Commission’s Travel Guidelines, the Chair or the Assistant Commissioner Corporate Group (if required) are expected to approve the Head of Office’s transactions. As the Assistant Commissioner Corporate Group is junior to the cardholder, this introduces positional authority risk.33 There was no evidence the potential for positional authority risk related to credit card use, including travel, had been appropriately assessed and managed by the Commission.

- The three external event transactions were supported by tax invoices and learning and development forms with pre-approval from appropriate delegates.

- The $306 restaurant meal transaction was supported by an itemised receipt, seminar agenda, and undated hospitality and catering form. There was no evidence of transaction pre-approval. In 2022 the Commission’s Research Committee approved broader funding for seminar services, but specific details on costings and timings were not discussed. The restaurant meal formed part of a lunch and seminar hosted by the Commission in April 2023. Supporting evidence indicated that the transaction was for six Commission staff and two external speakers.

- Two transactions were non-compliant taxi card purchases (non-compliant taxi card purchases are discussed at paragraphs 3.21 and 3.22).

- One was the $73 catering purchase (noted above) made by the Head of Office.

- The other transaction was a supermarket purchase of food items for an interstate meeting with a supporting receipt but no evidence of pre-approval.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

3.20 The Commission could clarify approval requirements and delegations for senior executive cardholders, purchases covered by mandatory coordinated procurement arrangements, and official hospitality and catering purchases. Additional guidance could also be provided on alcohol purchases. |

Merchant blocking

3.21 As noted in Box 2, the Commission’s Corporate Credit Cards Policy and Procedure includes a requirement to only use a taxi card for official domestic taxi travel and taxi alternatives. ANAO analysis of the Commission’s taxi card transactions identified 24 non-compliant purchases in 2022–23 (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3: Non-compliant taxi card transactions in 2022–23

|

Merchant |

Category |

Number of transactions |

Sum of transaction value |

|

Diplomat Hotel |

Hotel |

1 |

$195.00 |

|

Jetstar |

Airlines |

1 |

$37.38 |

|

KSBN Investments Pty Ltda |

Restaurant |

1 |

$73.00 |

|

Qantas Airwaysb |

Airlines |

1 |

$962.87 |

|

QBT Pty Ltdb |

Airlines |

2 |

$13.21 |

|

Quizletc |

Other |

2 |

$20.00 |

|

Ryan Traders Pty Ltd |

Retail |

1 |

$49.80 |

|

Spar Express |

Retail |

2 |

$15.72 |

|

Spotifyc |

Other |

7 |

$97.93 |

|

Uber Eatsd |

Restaurant |

1 |

$41.69 |

|

Woolworths |

Retail |

5 |

$345.82 |

|

Total |

24 |

$1,852.42 |

|

Note a: Transactions with these merchants were included the ANAO’s targeted testing discussed at paragraph 3.19.

Note b: The Commission advised the ANAO in April 2024 that the QBT Pty Ltd and Qantas Airways transactions were made on a virtual travel card, and not a taxi card, and there was an error with Diner Club administration.

Note c: The Commission identified Spotify and Quizlet transactions that were instances of fraud activities, cancelled the relevant cards and recovered $86.93 through alerting its credit provider to the fraudulent transactions.

Note d: The Uber Eats transaction was identified as accidental personal use and repaid by the cardholder. The transaction was recorded in the Commission’s misuse register as accidental misuse.

Source: ANAO analysis based on taxi card transaction data provided from the Productivity Commission.

3.22 The Commission’s control over taxi card compliance relies on staff adhering to its taxi card policy requirements and the finance team manually checking for non-compliant transactions each month. There are no processes in place to block or restrict certain merchant categories on taxi cards. As noted in Table 3.3, some of the non-compliant transactions were identified by the Commission as fraudulent or accidental misuse and recovered. For the remaining transactions, the Commission advised the ANAO in April 2024 that, despite being non-compliant with policy requirements, the purchases were made for acceptable business purposes.

Recommendation no.4

3.23 The Productivity Commission establish arrangements to ensure corporate credit cards are only used for the purposes defined within its policy requirements.

Productivity Commission response: Agreed.

3.24 The Commission accepts the recommendation and is reviewing the policy and the types of cards that are issued.

Returning cards

3.25 When ceasing employment or taking extended leave, cardholders are required to complete a clearance certificate to ensure that all types of credit cards are returned. The finance team signs off on the form once employees have returned the cards. The form outlines that:

All employees of the Commission who are leaving permanently, or who are expected to be on any type of extended leave for more than six months, must obtain the clearance required below before ceasing duty with the Commission, and before any final salary or cashed out leave entitlements will be paid.

3.26 The cessation form includes fields for finance, library, IT, human resources and payroll teams to sign off on the return of relevant equipment, including credit cards and outstanding monies.

3.27 In cardholder agreements for taxi cards and purchasing cards, cardholders are required to acknowledge that lost or stolen cards will be reported immediately to Diners Club, supervisors and the finance team.

3.28 The finance team maintains a card tracking and closure spreadsheet containing data extracted from the Diners Club system and employee cessation data obtained from human resources. There was one instance where the spreadsheet did not contain sufficient information to determine if cardholders had used their cards after they had ceased employment. The cardholder’s cessation date (provided by the human resources team) was recorded as January 2023, but credit card activity occurred after that date.

3.29 The Commission advised the ANAO in April 2024 that the employee had retired from the Commission in January 2023 and then returned as a casual employee, and as such the transactions identified after the date of cessation were acceptable. The card number identified in the card closure spreadsheet was different to the card number used in the transaction report and cardholder register, indicating that a new card was issued to the employee.