Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Governance of Artificial Intelligence at the Australian Taxation Office

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The term artificial intelligence (AI) incorporates a range of technologies. AI technologies are evolving and the use of AI is expanding.

- AI has the potential to support public sector entities to improve productivity, services and their effectiveness. On the other hand, there are risks that need to be managed.

- The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) uses AI, and it has plans to expand its use.

- This audit provides assurance to the Parliament over whether the ATO has effective arrangements to support the adoption of AI.

Key facts

- The Australian Government Policy for the responsible use of AI in government took effect from 1 September 2024.

- AI is used in different contexts by the ATO, including to: analyse data to assess non-compliance risks; assist with the drafting of communications; and help with visualisations.

What did we find?

- The ATO has partly effective arrangements in place to support the adoption of AI, including arrangements for: governance; design, development and deployment; and monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

- The ATO is adapting its current arrangements and introducing new arrangements to support its adoption of AI.

What did we recommend?

- The ANAO made seven recommendations to the ATO relating to AI governance, risk management, evaluation and information management.

- The ATO agreed to all seven recommendations.

43

ATO-built AI models in production at the ATO, as of 14 May 2024.

8

Number of publicly available generative AI tools approved as low risk by the ATO, as of 18 June 2024.

74%

Percentage of the ATO’s AI models in production that did not have completed data ethics assessments, as of August 2024.

Auditor-General’s foreword

Emerging technologies including artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly a part of public services, with 56 public sector entities advising in the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)’s 2023–24 financial statements audits that they have adopted AI in their operations. AI can offer the promise of better services, enhanced productivity and efficiency — and also has the potential for increased risk and unintended consequences.

AI is an area of public interest for the Australian Parliament, with two inquiries underway during the time of undertaking this audit. The Select Committee on Adopting AI reported in November 2024.1 At the time of presenting this audit report to the Parliament, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit is conducting an inquiry into the use and governance of AI systems by public sector entities.2 The Australian Government has policies and frameworks for agencies on the adoption and use of AI that are referred to in this audit.

The growing use of AI also brings new challenges and opportunities in auditing. As a first step in addressing these, the ANAO has identified providing assurance on the governance of the use of new technology as a way of bringing transparency and accountability to the Parliament in this area of emerging public administration. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO), as an agency that uses technology extensively in its administration of the tax and superannuation systems, was chosen as the first agency in this new line of audit work. I acknowledge the ATO’s work on governance to support rapidly emerging technologies and cooperation in the undertaking of this audit. I also acknowledge the assistance of the Digital Transformation Agency through consultation on this audit.

The ANAO will continue to focus on governance of AI while it develops the capability to undertake more technical auditing of the AI tools and processes used in the public sector. Building this capability will require investment in knowledge, methodology and skills to enable the ANAO to test more deeply how AI tools operate in practice.

Like audit offices around the world, the ANAO will seek to examine how AI can improve the audit process itself, in a profession where human judgement and scepticism are foundations in auditing standards. This work will progress through our relationships within the international public sector audit community over coming years.

Dr Caralee McLiesh PSM

Auditor-General

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The term artificial intelligence (AI) encompasses a broad range of technologies, some of which have been in existence for many years. The Australian Government (the government) has adopted the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD’s) definition of an AI system.

An AI system is a machine-based system that for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.3

2. There is no one-size-fits-all governance approach to support the adoption of AI. At the entity level, governance and assurance arrangements should be commensurate with the level of risk. Existing governance arrangements may need to be adapted or updated for AI, or new ones may need to be established.

3. The government has committed to adopting AI to ‘improve user experience, support evidence-based decisions and gain efficiencies in agency operations’ and to equip entities to safely engage with emerging technologies, including AI.4 In 2024, the government released an assurance framework for the use of AI in government5 and a policy on the responsible use of AI6, with an aim of positioning the government as an exemplar in the safe and responsible use of AI.

4. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) uses AI in a variety of contexts and has committed to the ethical and lawful adoption of AI. It plans to expand its use of AI over the coming years. The ATO’s primary use of AI involves AI models that it has built in house7, and publicly available generative AI tools that is has assessed as low-risk and approved for use. As of 14 May 2024, the ATO had 43 AI models in production and, as of 18 June 2024, eight publicly available generative AI tools approved for use. Table 2.1 provides further information about the ATO’s use of AI.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. AI technologies offer organisations, including public sector entities, a range of opportunities. AI can help public sector entities to drive productivity growth, to improve service delivery and to more effectively deliver on their purposes. On the other hand, issues that need to be managed include the risk of bias, lack of transparency and accountability, privacy, security and legality. This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament as to whether the ATO has effective arrangements in place supporting its adoption of AI.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the ATO has effective arrangements in place to support the adoption of AI.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Does the ATO have effective governance arrangements supporting the adoption of AI?

- Has the ATO established effective arrangements to support the design, development and deployment of AI models?

- Is the ATO effectively monitoring, evaluating and reporting on the adoption of AI?

Conclusion

8. The ATO has partly effective arrangements in place to support its adoption of AI. Within the Australian Government sector, requirements and guidance for AI governance and management are evolving. In 2024, there were a range of AI-related initiatives underway, including that the government policy on the responsible use of AI in government took effect from September 2024. The ATO is adapting existing data management and data governance arrangements and introducing new arrangements to support its adoption of AI, including to support risk management and assessments of ethical considerations. It lacks effective arrangements for the design, development, deployment and monitoring of its AI models.

9. The ATO has partly effective governance arrangements supporting its adoption of AI. In December 2023, it introduced a policy on the use of publicly available generative AI tools and it developed an automation and AI strategy in October 2022. The ATO has not: established fit-for-purpose implementation arrangements for this strategy; clearly defined enterprise-wide roles and responsibilities; established AI-specific risk management arrangements; and implemented its data ethics framework sufficiently for AI.

10. The ATO has partly effective arrangements supporting the design, development and deployment of its AI models.

- The ATO does not have specific policies and procedures for the design, development and deployment of its AI models, although there are enterprise policies and procedures which are relevant. The lack of approved and embedded policies and procedures creates risks to the effective implementation of models.

- The ATO has not sufficiently integrated ethical and legal considerations into its design and development of AI models. This impairs the ability of the ATO to demonstrate that its AI models are: fair and free from bias; reliable and safe; protecting privacy; transparent and explainable; contestable; and have appropriate accountability arrangements.

- There are no clearly defined assurance and approval arrangements that set out testing, validation, review and decision-making throughout the design, development and deployment of AI models.

11. The ATO has partly effective arrangements to monitor, evaluate and report on its adoption of AI.

- There was no evidence of structured and regular monitoring of ATO-built AI models in production. This was being addressed through the development of a monitoring and reporting framework for its AI models.

- The ATO did not regularly report on the implementation of its automation and AI strategy between October 2022 and January 2024. It has developed a monthly report since February 2024 to report on the implementation of the strategy. It has not set out an evaluation approach for the strategy.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements supporting the adoption of artificial intelligence

12. The ATO is developing a strategic framework to support its adoption of AI. It:

- is developing an AI policy and risk management guidance (due December 2025);

- has established a policy on the use of publicly available generative AI by ATO officers;

- does not have sufficient centralised visibility and oversight of its use of AI, impacting its ability to effectively govern the use of AI across the organisation; and

- has not established fit-for-purpose implementation arrangements for its automation and AI strategy. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.30)

13. The ATO uses existing organisational and governance structures to support its adoption of AI, and it has been adapting these for AI. Over time, the ATO has also established AI-focussed governance bodies. Key roles and responsibilities with respect to AI are not always clearly defined, including enterprise-wide responsibilities and accountabilities over the ATO’s AI governance framework and for AI models and systems. In September 2024, the ATO established a Data and Analytics Governance Committee in recognition that stronger governance arrangements were needed. In November 2024, the ATO appointed its Chief Data Officer as its accountable official under the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.45)

14. There are risks related to the adoption of AI at various levels at the ATO.

- The ATO has two enterprise risks that relate to AI due to their focus on data and analytics. These risks are ‘above tolerance’.

- The ATO has risk assessment processes that apply to its adoption of AI. It has identified that these are not sufficient for AI-specific risks, and it is working to introduce processes that better support the management of AI risks.

- The ATO has a risk-based approach to approving the use of publicly available generative AI technologies by ATO officers. (See paragraphs 2.46 to 2.74)

15. The ATO’s data ethics framework aims to support the ATO to deliver ethical data activities, including AI. For its AI models, the ATO has not complied with the requirements of this framework (74 per cent of AI models in production did not have completed data ethics assessments). This undermines the ATO’s ability to deliver and to assure the delivery of AI that aligns with ethical principles. The ATO has not developed effective monitoring and assurance arrangements for its data ethics framework. (See paragraphs 2.75 to 2.93)

Arrangements supporting the design, development and deployment of artificial intelligence models

16. The ATO has not established a framework of policies and procedures for the design of AI models. For the 14 models that the ATO developed and deployed between 1 July 2023 and 14 May 2024, there were mixed practices related to planning, governance and design. The ATO largely defined business problems to be solved by AI models, defined roles and responsibilities and documented stakeholder engagement. There were gaps in terms of: project planning and risk management; assessment of ethical, security, privacy and legal considerations; and assurance, decision-making and record keeping. For the work-related expenses AI models8, there were gaps in how the ATO assessed ethical, privacy and legal considerations. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.16)

17. The ATO has not established a framework of policies and procedures for the development of AI models, although model development is to be documented in a standardised modelling solution report. For the 14 models that the ATO deployed between 1 July 2023 and 14 May 2024, there were differences in approaches as to: how data suitability was assessed and documented within the context of each model; how testing and validation was conducted; and decision-making arrangements for the development phase. For the work-related expenses AI models, the ATO assessed two potential biases. There was a lack of evidence to demonstrate that the ATO had considered whether data was fit for purpose and documented considerations relating to reproducibility. (See paragraphs 3.17 to 3.25)

18. The ATO’s IT change enablement policy applies to all IT changes at the ATO, including the deployment of its AI models. For the 14 models that the ATO deployed between 1 July 2023 and 14 May 2024, practices varied for defining deployment criteria and deploying models. The ATO planned for model deployment and partially conducted verification and validation of models. (See paragraphs 3.26 to 3.31)

Monitoring, evaluating and reporting on the adoption of artificial intelligence

19. The ATO does not have policies and procedures supporting the monitoring and evaluation of its in-house built AI models. For the 14 AI models built and deployed between 1 July 2023 and 14 May 2024, there was no evidence of ongoing performance monitoring and reporting. For the work-related expenses AI models, there were some examples of monitoring and evaluation. Baselines were not reported in ongoing monitoring and reporting to show the impact of introducing the models. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.9)

20. The ATO has a project underway to introduce an enterprise-wide approach to monitoring the performance of its AI models by December 2026. The ATO has developed a ‘use of publicly available generative AI technology policy’. The ATO does not report on compliance with this policy to relevant internal governance bodies. For its automation and AI strategy, the ATO introduced status reporting in February 2024. It does not have arrangements in place to measure the effectiveness of the strategy. Some continuous improvement arrangements were evident including an internal governance review and the delivery of the automation and AI strategy. There is a need for the ATO to improve its management of information in support of the transparent and accountable adoption of AI. (See paragraphs 4.10 to 4.32)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.29

The ATO align implementation arrangements for the automation and AI strategy with enterprise-wide requirements.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.44

The ATO clearly define and communicate enterprise-wide organisational structures and governance arrangements supporting its adoption of AI, including defining accountabilities and responsibilities at the model and system level.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.61

The ATO review the misuse of data and analytics enterprise risk in accordance with its enterprise risk management framework and risk appetite, and update and incorporate controls relating to the impact of AI on this risk.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.92

The ATO improve its arrangements in support of the design, development, deployment and use of AI that aligns with ethical principles by:

- specifying requirements relating to AI reproducibility and auditability;

- ensuring the data ethics framework is integrated into other ATO processes;

- completing ethics assessments for the AI models in production; and

- introducing monitoring, assurance and reporting arrangements over the implementation of its data ethics framework.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.30

The ATO develop and implement policies and procedures to support the effective design, development, deployment and assurance of AI models. Where relevant ATO policies and procedures exist, the ATO ensure that the design, development and deployment of AI models aligns with these.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.22

The ATO establish performance measurement and evaluation arrangements for its automation and AI strategy.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.31

The ATO ensure that its approach to managing information supports transparency and accountability with respect to its adoption of AI.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to ATO. The ATO’s summary response is provided below, and its full response is included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

The ATO aims to continually improve its use of data and analytics to derive the insights needed to give better clarity and certainty for our decisions and actions. The ATO remains committed to managing taxpayer data with integrity and ensuring ethical decision making in everything we do. We recognise the importance of robust governance and accountability to support the development and use of analytical models that are ethical, safe and deliver outcomes that are fit for purpose.

The ATO therefore welcomes this review and the ANAO’s insights as to how to continue to improve our artificial intelligence (AI) related governance. We also have appreciated the opportunity to assist the ANAO benchmark its approach to conducting similar AI use and governance audits in the future, as well as providing insights to other APS Agencies.

We are proud to be a leading agency of data governance and management in the APS. We acknowledge what is considered leading practice for AI use and governance is still evolving and we will continue to not only strive to achieve leading practice, but also assist the broader APS. The next phase of maturing our data governance has commenced as we develop and implement AI specific policies and guidance.

We agree with the seven recommendations in the report and are working to implement them. The recommendations will help us evolve our existing governance and practices to remain current in the face of rapidly advancing AI capability.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

Record keeping

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Technologies considered to be artificial intelligence (AI) have been in existence for many years. AI has the potential to support public sector entities to drive efficiencies and productivity growth, to improve service delivery and to deliver on their purposes more effectively. On the other hand, poor implementation of AI in public service delivery could risk eroding trust in the public service or cause harm.9

1.2 Good governance and assurance arrangements support the delivery of ethical and lawful AI.10 Given the breadth of AI, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has highlighted that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to AI governance:

different AI systems bring different benefits and risks. In comparing virtual assistants, self-driving vehicles and video recommendations for children, it is easy to see that the benefits and risks of each are very different. Their specificities will require different approaches to policy making and governance.11

1.3 The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) employs AI in a variety of contexts to analyse large datasets for the provision of analysis and assessments.12 The ATO’s primary use of AI involves AI models that it has built in house, and publicly available generative AI tools that it has assessed as low-risk and approved for use. As of 14 May 2024, the ATO had 43 AI models in production and, as of 18 June 2024, eight publicly available generative AI tools approved for use. Table 2.1 provides further information about the ATO’s use of AI.

Artificial intelligence

1.4 There is no single commonly agreed upon definition of AI. The OECD has identified that this may create challenges when developing legislation and regulation for AI.13 As technology has advanced and evolved, definitions have changed and may continue to change.14

1.5 The Australian Government (the government) has adopted the OECD’s definition of an AI system and suggests that entities should keep up to date on changes to this definition (Box 1).15

|

Box 1: Definition of an AI system |

|

In November 2023, OECD countries adopted a consensus definition of an AI system:

|

Note a: OECD, Explanatory memorandum on the updated OECD definition of an AI system, OECD, March 2024, p. 4, available from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/explanatory-memorandum-on-the-updated-oecd-definition-of-an-ai-system_623da898-en [accessed 5 April 2024].

1.6 AI systems can be broadly categorised as:

- narrow or weak AI — an AI system that is ‘trained’ to deliver outputs for specific tasks to address specific problems, such as search engines or facial recognition; or

- general purpose or strong AI — an AI system that can be used for a broad range of tasks, both intended and unintended by developers, such as text or image generation.16

Artificial intelligence in the Australian Government sector

1.7 The government has stated that AI has the potential to enhance Australia’s wellbeing, quality of life and economic growth.17 In its Data and Digital Government Strategy published in December 2023, the government committed to adopting AI to ‘improve user experience, support evidence-based decisions and gain efficiencies in agency operations’ and to equip entities to safely engage with emerging technologies, including AI.18

OECD AI Principles and Australia’s AI Ethics Framework

1.8 The ethical use of AI involves promoting the responsible design, development and implementation of AI that is ‘innovative and trustworthy and that respects human rights and democratic values’.19 Ethical AI practices assist organisations to implement AI technologies that are safer, more reliable and fairer, and reduce the risks of negative outcomes.20

1.9 The OECD has developed five AI principles around: inclusive growth, sustainable development and wellbeing; human rights and democratic values, including fairness and privacy; transparency and explainability; robustness, security and safety; and accountability.21

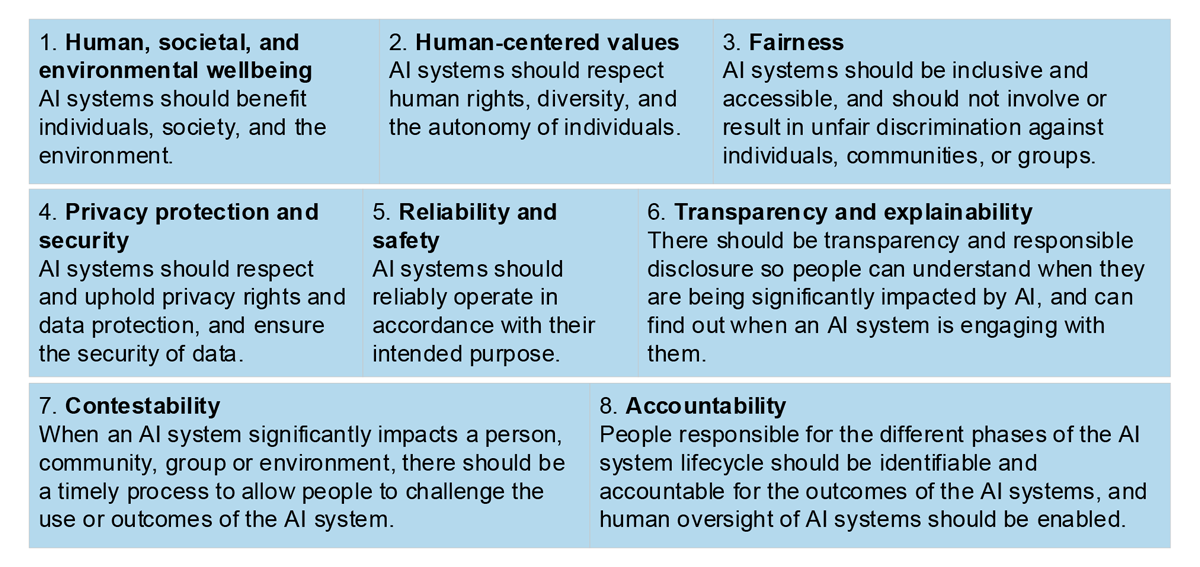

1.10 The government committed to meeting the OECD principles through Australia’s AI Ethics Framework which was published in November 2019.22 This framework ‘guides businesses and governments to responsibly design, develop and implement AI’ and includes eight AI Ethics Principles (see Figure 1.1).23 The framework states that by applying the ethics principles and committing to ethical AI practices, organisations can build public trust, positively influence outcomes from AI, and ensure all Australians benefit from this technology.

Figure 1.1: Australia’s AI Ethics Principles

Source: Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Australia’s AI Ethics Principles.

Use and initiatives

1.11 As of 30 June 2024, 56 Australian Government entities had reported to the ANAO that they had adopted AI (2022–23: 27 entities).24 Most of these entities had adopted AI for research and development activities, IT systems administration and data and reporting. Of the 56 entities adopting AI, 36 (64 per cent) established internal policies specifically governing the use of AI, while 15 (27 per cent) established internal policies regarding assurance over AI use. Use of AI by entities includes: chatbots, virtual assistants and agents in service management; document and image recognition; to support law enforcement; data mapping to geographical areas; and, as noted in Table 1.1, a trial of Copilot for Microsoft 365.

1.12 Table 1.1 presents a timeline of key Australian Government and parliamentary initiatives relating to AI between 1 July 2023 and 31 December 2024.

Table 1.1: Key Australian Government and parliamentary AI initiatives, July 2023 to December 2024

|

Date |

Initiative |

|

6 July 2023 |

The Digital Transformation Agency released ‘Interim guidance on generative AI for Government agencies’. An update was published on 22 November 2023. |

|

20 September 2023 |

The AI in Government Taskforce was established to develop whole-of-government AI policies, standards and guidance. It comprised secondees from 11 entities, including the ATO. It ended in June 2024. |

|

13 November 2023 |

The government responded to the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme. In response to recommendation 17.2 (establishment of a body to monitor and audit automated decision-making), the government stated that it would ‘ensure there is appropriate oversight of the use of automation in service delivery’. It noted that this would include AI. |

|

15 December 2023 |

|

|

1 January – 30 June 2024 |

More than 50 Australian Public Service entities, including the ATO, undertook a six-month trial of Copilot for Microsoft 365.a |

|

2 February 2024 |

The AI Expert Group was established to advise on proposed mandatory guardrails for the safe design, development and deployment of AI systems in high-risk settings. The group includes government and non-government members. |

|

21 June 2024 |

The National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government was released to set ‘foundations for a nationally consistent approach to AI assurance’. |

|

15 August 2024 |

The government released the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government with effect from 1 September 2024 to position the government as an exemplar under its safe and responsible AI agenda. It includes mandatory requirements for accountable officials by 30 November 2024 and transparency statements by 28 February 2025. |

|

September 2024 |

The Digital Transformation Agency commenced the pilot of the Australian Government AI Assurance Framework with a group of entities, including the ATO. |

|

5 September 2024 |

The government announced further consultation on guardrails for AI in high-risk settings and released the Voluntary AI Safety Standard. |

|

12 September 2024 |

The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit commenced an inquiry into the use and governance of AI systems by public sector entities. |

|

11 October 2024 |

The Senate Select Committee on Adopting Artificial Intelligence released its interim report, making five recommendations. It was established in March 2024 to inquire into and report on the opportunities and impacts arising out of the uptake of AI. |

|

11 October 2024 |

The Digital Transformation Agency released Guidance for staff training on AI and an AI in government fundamentals training module. |

|

23 October 2024 |

The Digital Transformation Agency released an evaluation of the whole-of-government trial of Copilot for Microsoft 365. The evaluation concluded that ‘there are clear benefits to the adoption of generative AI but also challenges with adoption and concerns that need to be monitored’. |

|

26 November 2024 |

The Senate Select Committee on Adopting Artificial Intelligence tabled its final report. It made 13 recommendations. |

|

13 December 2024 |

The government announced that it would develop a National AI Capability Plan to support growth of Australia’s AI capabilities. |

|

17 December 2024 |

The government released a whole-of-government data ethics framework to provide guidance on best practice for ethical considerations relating to public data use. |

Note a: Copilot for Microsoft 365 is a generative artificial intelligence chatbot/assistant which integrates with Microsoft 365 products. The ANAO participated in this trial.

Source: ANAO analysis.

National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government

1.13 In June 2024, the Australian Government and state and territory governments released the National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government to support Australia’s governments in ‘gaining public confidence and trust in the safe and responsible use of AI’.25 The framework is based on Australia’s AI Ethics Principles with the intention to establish a ‘nationally consistent’ approach to foundations for AI assurance practices across all aspects of government.26

Policy for the responsible use of AI in government

1.14 In August 2024, the government released the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government to position the Australian Government sector ‘as an exemplar under its broader safe and responsible AI agenda’ and ‘to create a coordinated approach to the government’s use of AI’.27 The policy came into effect on 1 September 2024 and requires28 that:

- entities designate ‘accountable officials’ by 30 November 202429; and

- entities publish AI transparency statements by 28 February 2025 and update these annually or sooner, if they make significant changes to their approach to AI.30

Artificial intelligence at the Australian Taxation Office

1.15 The ATO’s purpose is ‘to contribute to the economic and social wellbeing of Australians by fostering willing participation in the tax, superannuation, and registry systems’.31 The ATO states that it uses data and analytics (including AI) to: understand and improve interactions with its ‘clients’; make better, faster and smarter decisions; deliver outcomes with ‘agility’; and support advice to government.32

1.16 The ATO has stated that its data activities (including its use of AI) must be both lawful and ethical. The ATO’s six data ethics principles (see paragraphs 2.77 to 2.79) set the minimum standards that must be considered when collecting, using, sharing, archiving, and disposing of data. Through these principles, the ATO aims to address the main identified ethical risks that may arise in data activities and ensure that data is used by the ATO in an appropriate way.

1.17 The ATO reported on the way that it uses AI:

The ATO uses AI tools to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of work done by staff enabling us to deliver better services and greater value to the community. The ATO currently uses AI to review large quantities of unstructured data for risk and intelligence purposes, power risk models to identify potential non-compliance for human review, and draft and edit communications. The ATO has human oversight over all uses of AI, and decision making that impacts clients is always made by a human.33

1.18 The ATO uses AI in a variety of contexts including: to assess risks associated with submitted claims, such as individual tax returns; to help manage its call centre volumes; and to provide its virtual assistant on the ATO website, Alex (see Table 2.1 for an overview of AI in use at the ATO).

1.19 The ATO has participated in government AI-related initiatives, such as: the AI in Government Taskforce; the Copilot for Microsoft 365 trial; the trial of the Australian Government AI assurance framework; and the development of a whole-of-government Data Ethics Framework.

Previous audits and reviews

1.20 In Audits of the Financial Statements of Australian Government Entities for the Period Ended 30 June 2024, the ANAO outlined that an ‘absence of frameworks governing the use of emerging technologies could increase the risk of unintended consequences’. The ANAO reported that during 2023–24, ‘64 per cent of entities that used AI had also established internal policies governing the use of AI (2022–23: 44 per cent). Twenty-seven per cent of entities had established internal policies regarding assurance over AI use’.34

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.21 AI technologies offer organisations, including public sector entities, a range of opportunities. AI can help public sector entities to drive productivity growth, to improve service delivery and to more effectively deliver on their purposes. On the other hand, issues that need to be managed include the risk of bias, lack of transparency and accountability, privacy, security and legality. This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament as to whether the ATO has effective arrangements in place supporting its adoption of AI.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.22 The objective of the audit was to assess whether the ATO has effective arrangements in place to support the adoption of AI.

1.23 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Does the ATO have effective governance arrangements supporting the adoption of AI?

- Has the ATO established effective arrangements to support the design, development and deployment of AI models?

- Is the ATO effectively monitoring, evaluating and reporting on the adoption of AI?

1.24 The audit scope included:

- an examination of the ATO’s governance arrangements applying to its adoption of AI, with a focus on the period from 1 July 2022 to 30 June 2024;

- an examination of the design, development, deployment and monitoring of 14 AI models deployed by the ATO between 1 July 2023 and 14 May 2024 — see Appendix 3 for a list and description of these models; and

- an examination of the ATO’s AI models that it uses in the context of processing and assessing work-related expenses claims — see Appendix 4 for a list and description of these models.

1.25 The audit scope does not include an examination of the ATO’s data governance and data management more broadly.

Audit methodology

1.26 The audit methodology involved:

- examination of entity records, including email records and electronic documentation;

- meetings with ATO officers and external stakeholders;

- walkthroughs of ATO systems and analysis of selected AI models; and

- review of citizen contributions to the audit.

1.27 Appendix 5 provides an overview of the sources (legislation, standards, policies and guidance) that have informed the methodology for this audit.

1.28 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $892,944.

1.29 The team members for this audit were Nathan Callaway, Dr Shannon Clark, Stewart Hafey, Kayla Hurley, Nancy Jin, Kelvin Le, Zhuo Li, Alyssa McDonald, Benjamin Siddans and David Tellis.

2. Governance arrangements supporting the adoption of artificial intelligence

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has effective governance arrangements in place supporting its adoption of artificial intelligence (AI).

Conclusion

The ATO has partly effective governance arrangements supporting its adoption of AI. In December 2023, it introduced a policy on the use of publicly available generative AI tools and it developed an automation and AI strategy in October 2022. The ATO has not: established fit-for-purpose implementation arrangements for this strategy; clearly defined enterprise-wide roles and responsibilities; established AI-specific risk management arrangements; and implemented its data ethics framework sufficiently for AI.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at: establishing implementation arrangements for the ATO’s automation and AI strategy; defining roles and responsibilities; reviewing the ATO’s misuse of data and analytics risk; and enhancing the arrangements supporting the delivery of AI that aligns with ethical principles.

The ANAO also suggested that the ATO could: update relevant policies and procedures; have a register of all AI; and improve risk management arrangements for generative AI.

2.1 AI governance is an evolving area, with a common theme that there is no one-size-fits-all governance model. The National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government outlines that ‘[g]overnance structures should be proportionate and adaptable to encourage innovation while maintaining ethical standards and protecting public interests’.35

2.2 At the organisational level, AI governance includes: establishing an AI policy and strategy; assigning and communicating roles and responsibilities; establishing risk management arrangements; and integrating ethical considerations into the design and development of AI systems.

Does the ATO have an effective strategic framework supporting the adoption of artificial intelligence?

The ATO is developing a strategic framework to support its adoption of AI. It

- is developing an AI policy and risk management guidance (due December 2025);

- has a policy on the use of publicly available generative AI by ATO officers;

- does not have sufficient centralised visibility and oversight of its use of AI, impacting its ability to effectively govern the use of AI across the organisation; and

- has not established fit-for-purpose implementation arrangements for its automation and AI strategy.

Artificial intelligence policy

2.3 The ATO’s data management and data governance policies apply to its use of AI.36 The ATO’s Data Management Chief Executive Instruction (data management policy) sets out requirements for managing data throughout the data lifecycle.37 The ATO states that its data governance arrangements incorporate: policy, standards and guidance; organisational structures and oversight mechanisms; culture, ethics and behaviour; people, skills and competencies; and compliance and issues management.

2.4 While the ATO’s data management and data governance arrangements apply to AI, it has identified that these are not fit for purpose for AI. This includes that: existing arrangements do not sufficiently capture AI-specific risks; there is no defined process when undertaking AI-related activities; there are staff capability gaps around AI-specific risks and data management obligations; there is minimal AI-specific governance, with limited enterprise visibility; and there are few controls to manage risks associated with AI activities.

2.5 The ATO was updating or had plans to update several aspects of its data management and data governance arrangements for AI.

- The ATO was developing an AI policy and AI risk management guidance. These were expected to be delivered in 2024, however, as of December 2024, are expected by December 2025. The ATO has identified that a ‘complex consultation process is required to stand up’ the new policy.38

- The ATO’s data management policy mandates the application of the ATO’s data ethics framework and data stewardship model for all data activities, including AI. In August 2024, the ATO updated its ethics assessment processes for analytical models, including AI models (see paragraph 2.81).

2.6 As part of an April 2024 internal review by the ATO, the ATO sought to determine the extent to which AI requires its own governance and management arrangements. The conclusion was that ‘AI requires a more distinct approach since specialist knowledge is required to be able to manage the unique issues and risks that AI poses’. In the review, the ATO assessed that its framework39 for AI had the most significant gaps (compared to data, analytics and automation frameworks) and the lowest level of maturity.40 It also noted a lack of a strategy to fill the gaps at the time. The ATO advised the ANAO on 16 September 2024 that ‘prioritisation and resource constraints have slowed planned work to address data governance gaps’.

2.7 The Policy for the responsible use of AI in government outlines that entities should integrate AI considerations into existing frameworks such as those for privacy, protective security, record keeping, cyber and data.41 As of July 2024, the ATO had not reviewed other relevant ATO frameworks and policies to assess their applicability to AI and to determine if they need to be updated and adapted for AI.

Opportunity for improvement

2.8 The ATO could review and update other enterprise policies and procedures for AI, as appropriate.

Use of publicly available generative AI policy

2.9 The Australian Government released guidance on the use of publicly available generative AI tools in July 2023, with updated guidance in November 2023.42 In December 2023, the ATO finalised a policy for ATO officers on using publicly available generative AI technology.43 The policy sets out processes aimed at supporting the appropriate and responsible use of publicly available generative AI tools by ATO officers. The policy states that ‘publicly available generative AI technologies may be approved for ATO work purposes, on ATO devices and networked computers, where the risk of negative impact is low’. The ATO’s oversight of this policy is discussed at paragraph 2.39 and its approach to assessing the risk of publicly available generative AI technologies is discussed at paragraphs 2.69 to 2.73.

Artificial intelligence at the ATO

2.10 Prior to the release of the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government, the ATO defined AI as a ‘subset of computer science that deals with computer systems able to perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence, such as object recognition, speech recognition, decision-making and language translation’.

2.11 In October 2024, the ATO reported that it has adopted the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) definition of AI in accordance with the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government. It has also stated that it ‘refers to any application of machine learning, deep learning and generative AI as AI. But does not consider rules-based analytics to be AI, as this form of analytics does not infer how to generate outputs from the inputs they receive’.44 Table 2.1 provides an overview of AI in use at the ATO.

Table 2.1: AI in use at the ATO

|

Category |

Description |

|

AI models built and developed by the ATO |

On 14 May 2024, the ATO provided the ANAO with a list of 43 modelsa in production that it defined as being AI. These models were developed in house by the ATO.

The ATO’s AI models use a range of machine learning algorithms, including natural language processing, deep learning and neural networks, in both supervised and unsupervised learning approaches. The ATO uses its AI models to support decision-making. None of the 43 models make fully automated decisions. Paragraph 2.15 sets out the nature of automated actions of these models. |

|

Publicly available generative AI |

The ATO has a register of publicly available generative AI technologies and associated uses approved for use under its ‘use of publicly available generative AI technology policy’. As of 18 June 2024, there were eight publicly available generative AI technologies approved for use within the ATO.c |

|

Other |

The ATO has some other uses of AI such as the virtual assistant on its website (Alex) and within call centres. |

Note a: The ATO defines AI models as: algorithms designed to mimic or surpass human intelligence and make predictions based on data; and that use mathematical, statistical or machine learning techniques trained on extensive datasets to process and analyse information.

The ATO’s AI models can link to one or more machine learning algorithms. The 43 AI models link to a total of 93 machine learning algorithms.

Note b: One of the work-related expenses AI models — document understanding — is not included in this list as it had not been put into production as of 14 May 2024.

Note c: These were: Microsoft Copilot; GitHub Copilot Visual Studio 2022 Extension for Business; Code Llama; Llama 2; Adobe Creative Cloud; OpenAI ChatGPT Team; IBM Cloud IaaS; and CoPilot for Microsoft 365.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

2.12 The ATO does not have a centralised inventory of all AI uses across the organisation. The ATO advised the ANAO on 16 September 2024 that there were no other uses of AI within the entity other than those listed in Table 2.1. Subsequent to this advice, in October 2024 the ATO reported to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit that it had also used AI to process 36 million documents to help identify entities of interest and their relationships, commencing in 2016. Although the original AI models used for this work have since been decommissioned, the ATO further advised the ANAO in January 2025 that it currently uses commercial software which incorporates AI for extracting intelligence from high-volume structured and unstructured data.45 This use is not included in Table 2.1.

Register and type of AI models

2.13 The National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government (June 2024) states that an entity should maintain a register of when it uses AI, its purpose, intended uses and limitations.46

2.14 The ATO’s list of 43 AI models in production included the model name and grouping, and information about the timing of model execution. The list did not include information about each use case such as: the purpose and context of use; the type of model and technology infrastructure being used; the data used in both training and operation; ongoing cost; the results of recent ethical, privacy, legal and other risk assessments; performance information; and the extent of automation or automated decision-making.

2.15 Having oversight over the use of AI in relation to decision-making is important for governance and managing risks.47 The ATO advised the ANAO on 10 May 2024 and 22 July 2024 that of the 43 AI models, 30 did not include fully automated actions and 13 did.48 Eleven included automated ‘nudge’ messaging49; five included other automated messaging; seven included automated case selection for compliance action; and seven included other automated actions.50

2.16 Not having a centralised inventory of AI which includes key information impacts the ability of the ATO to effectively oversee and to be transparent and accountable with regard to its use of AI. Having good visibility and clearly defined purposes for AI models and systems is an important component of building fit-for-purpose governance. As at July 2024, the ATO was developing a register of its data and analytics models, including AI models. The ATO expects to finalise the register by March 2025.

Opportunity for improvement

2.17 The ATO could ensure that it has a complete and accurate inventory of all uses of AI across the organisation.

2.18 While the ATO does not maintain a register of key information about its AI models, the ATO’s 43 AI models could all be categorised as narrow AI (refer to paragraph 1.6) because they perform specific tasks or functions. The primary function of these models is to help the ATO analyse data in order to evaluate the risks that a taxpayer’s claims are not compliant, or to understand the impact tax agents have on their clients’ tax affairs.

Artificial intelligence strategy

Development and oversight of the strategy

2.19 The ATO commenced development of an automation and AI (A&AI) strategy in September 2020. The ATO did not have a planned approach to the development of this strategy. Consultation occurred across the ATO in developing the strategy — in the strategy, the ATO outlined that 17 business areas across the ATO were consulted to identify 52 potential A&AI use cases.

2.20 The ATO’s Data and Analytics Committee51 endorsed the A&AI strategy on 7 October 2022, two years after development commenced. In December 2022, the Data and Analytics Committee was dissolved, with its responsibilities transferred to the ATO’s Strategy Committee.52 The Strategy Committee makes decisions and provides advice in relation to the ATO’s strategies, oversees the implementation of strategies and monitors operational performance.

Goals of the strategy and linkages to other ATO strategies and plans

2.21 The ATO’s A&AI strategy states that there is a need for an ‘organisational strategy [for A&AI] to fully harness the benefits’. The vision is that ‘by 2030 the ATO is a leader in developing and industrialising ethical, impactful and scalable A&AI solutions, creating immense economic and social benefit for our nation and citizens’. Measurement against the strategy’s goals is discussed further in paragraphs 4.20 to 4.22.

2.22 The A&AI strategy has links to other ATO strategies and plans, including its corporate plan, digital strategy and data and analytics strategy. These strategies and plans incorporate strategic goals and objectives in relation to the adoption of AI.

2.23 Central to the ATO’s A&AI strategy is the delivery of five enterprise A&AI uses cases. The ATO outlined that use cases were prioritised based on value to deliver, feasibility of implementation and demand. The use cases aim to enhance existing or build new AI systems at the enterprise level. An overview of the five use cases is in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: A&AI strategy use cases

|

Use case |

Objective |

Future state |

|

AI automatically reads, understands and analyses any document, saving significant human workload. |

Auto content extraction and understanding for most of the ATO’s common documents. |

|

Meet increasing need for real-time or pre-emptive insight and identification. |

Pre-emptive insight and action whenever possible. Real-time interaction whenever appropriate. |

|

Connect systems, data and intelligence to create a complete picture of taxpayers. |

Taxpayer enterprise-wide personalisation. Improved compliance and experience. Reduced management and compliance cost. |

|

AI learns from law frameworks and precedential rulings to suggest correct application of the law. |

Enterprise knowledge base that serves as a ‘second brain’: having all the knowledge, and capable of inferencing. |

|

Enterprise and systematic approach to closing the loop between AI and human. |

Communicate with AI enterprise wide. Human and AI as interacting partners through feedback integration APIsb for enterprise-wide reusability. |

Note a: Use case five is not AI. Rather, it involves the development of a model monitoring system.

Note b: An application programming interface (API) is a software intermediary that allows applications to communicate with each other.

Source: ATO’s A&AI strategy.

Implementation arrangements

2.24 On several occasions throughout the development of the A&AI strategy, the ATO committee overseeing the development of the strategy sought clarity on implementation. The A&AI strategy did not set out implementation arrangements. It stated that the next steps would involve the development of implementation arrangements including: developing a plan; scoping and designing value cases for each enterprise use case; implementing use cases; reporting on value returned; and proceeding with other future use cases.

2.25 Between October 2022 and July 2024, the ATO acknowledged the need to develop overarching implementation arrangements for the A&AI strategy. On 23 July 2024, the ATO provided the ANAO with a document titled ‘A&AI Implementation plan’ dated January 2024. The ATO described this document as ‘a high-level implementation plan designed for an executive audience’ and noted that further detailed planning is needed. Approval of this document was not evident.

2.26 Implementation of the A&AI strategy is the responsibility of the ATO’s Smarter Data area. The Assistant Commissioner Data Science within Smarter Data is nominated as the senior responsible officer for implementation of the strategy. Roles and responsibilities supporting the implementation of the strategy across the ATO have not been clearly defined.

2.27 According to the ATO’s policy on corporate project management, a corporate project is a body of work that requires resourcing or services that cannot be funded or sourced from within a single business line. While this is the case for the A&AI strategy which has funding sources from multiple business areas, implementation of the A&AI strategy is not being managed as a corporate project. The ATO is implementing the A&AI strategy as a business line project.53 The ATO’s guidance for business line projects require a project outline be completed to document how the project will be managed. A project outline had not been developed for the A&AI strategy.

2.28 On 22 May 2024, the Strategy Committee recommended that delivery of the five use cases should continue with current funding and resourcing (this includes a mix of business-as-usual funding and funding from new policy proposals).

Recommendation no.1

2.29 The ATO align implementation arrangements for the automation and AI strategy with enterprise-wide requirements.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.30 The ATO will undertake work to improve the alignment of the automation and AI strategy with enterprise requirements, noting we may need to subsequently evolve it to align with the rapidly changing AI environment and any APS requirements as they are developed.

Has the ATO clearly defined and communicated roles and responsibilities supporting the adoption of artificial intelligence?

The ATO uses existing organisational and governance structures to support its adoption of AI, and it has been adapting these for AI. Over time, the ATO has also established AI-focussed governance bodies. Key roles and responsibilities with respect to AI are not always clearly defined, including enterprise-wide responsibilities and accountabilities over the ATO’s AI governance framework and for AI models and systems. In September 2024, the ATO established a Data and Analytics Governance Committee in recognition that stronger governance arrangements were needed. In November 2024, the ATO appointed its Chief Data Officer as its accountable official under the Policy for the responsible use of AI in government.

2.31 A part of good governance is ensuring that responsibilities and accountabilities, including decision-making and oversight roles, are clearly defined and communicated.54 For AI, ‘existing decision-making and accountability structures should be adapted and updated to govern the use of AI’.55 It should be clear who is responsible and accountable for determining and implementing an entity’s overarching approach to AI and for individual AI systems or uses of AI.56

Organisational structures

2.32 The ATO advised the ANAO on 19 April 2024 that key AI responsibilities are within the Client Engagement Group, and the Enterprise Solutions and Technology Group.

2.33 Within the Client Engagement Group, the Smarter Data area57 has primary responsibility for the ATO’s management and governance of data and analytics, including AI activities. The Data Science branch in Smarter Data provides skills and advice on AI, machine learning, deep learning and natural language processing. In January 2024, the ATO established an AI Governance team within the Data Management branch in Smarter Data. The Deputy Commissioner Smarter Data is responsible for:

- guiding strategic data management policies, practices and procedures;

- ensuring consistent data governance and management across the ATO; and

- the management of two AI-related enterprise risks: the ‘maximising the value of data and analytics’ risk and the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk (see Table 2.4).

2.34 Within the Enterprise Solutions and Technology Group, key responsibilities relating to AI relate to technology solutions and ICT architecture, cyber security governance and operations.

Enterprise-level governance committees

2.35 The Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) is the accountable authority of the ATO and is supported by the ATO Executive Committee. The ATO’s Audit and Risk Committee supports the Commissioner by providing independent advice and assurance.58 The Commissioner and the ATO Executive Committee are supported by six enterprise-level committees: Finance Committee; People Committee; Risk Committee; Security Committee; Strategy Committee and National Consultative Forum.59

2.36 The ATO’s Risk Committee and Strategy Committee have roles in relation to AI.

- The Risk Committee is responsible for oversight of the management of enterprise risks including the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ and the ‘maximising the value of data’ risks.

- The Strategy Committee is responsible for overseeing the implementation of the ATO’s A&AI strategy. It also has responsibilities in relation to data and analytics including ensuring that ATO strategies and programs are data and analytics driven, and overseeing data ethics and data stewardship issues.

2.37 The ANAO reviewed meeting minutes of the ATO Executive Committee, the Audit and Risk Committee, the Risk Committee and the Strategy Committee between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2024 to understand how these committees have considered the ATO’s adoption of AI.60 A summary of this analysis is presented in Table 2.3. AI was discussed at and reported to these committees on a range of occasions, although reporting was not based on defined and agreed arrangements.

Table 2.3: ATO governance committees’ oversight of the ATO’s adoption of AI

|

Committee and summary of discussion related to AI, July 2022 to June 2024 |

|

The Commissioner and the ATO Executive Committee — the ATO Executive Committee discussed AI five times. Discussions included: AI in the context of a scan of business community concerns; review of governance arrangements to manage proposals and the application of AI; two briefings in relation to generative AI; and the ATO’s A&AI strategy. These discussion items were initiated by the Audit and Risk Committee, the Risk Committee and the Chief Financial Officer. |

|

Audit and Risk Committee — Discussions included: the use of AI in a service delivery context; the ATO’s two AI-related enterprise risks, the inclusion of AI in the ATO’s data management policy; the ATO’s policy on the use of publicly available generative AI; the impact of AI on emerging data and technology-related risks; whole-of-government AI initiatives; and audits of AI as part of the internal audit program. |

|

Risk Committee — the Risk Committee discussed AI on five occasions. Discussions included: the risks and opportunities for the use of generative AI across the ATO; the two AI-related enterprise risks; and a proposal to establish a data and analytics governance committee. |

|

Strategy Committee — the Strategy Committee discussed the A&AI strategy on three occasions. It also discussed the opportunities and risks related to generative AI technologies and, more broadly, the potential use of AI by those in the taxation and superannuation systems for ‘nefarious purposes’. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

AI roles and responsibilities

AI governance committees

2.38 Over time, the ATO has established governance bodies with areas of focus relating to AI. In September 2024, the ATO established the Data and Analytics Governance Committee. The committee’s role is to make decisions and provide to promote the responsible use of data and analytics at the ATO. The charter notes that this role will evolve over time. It reports to the Strategy Committee.

2.39 In establishing this committee, it was noted that ‘continued fragmentation of approaches to [data and analytics] governance and management’ was a risk of not establishing the committee. From October 2024, the following extant groups report to the Data and Analytics Governance Committee.

- The Business Automation Governance Committee (established in June 2021) is to govern and oversee business automation decisions and to ‘fulfil the A&AI strategy’. The Committee’s role in relation to the A&AI strategy is not clearly defined. The ATO advised the ANAO on 8 August 2024 that it has no formal role in relation to the strategy.

- The Data Ethics Review Panel (established in November 2021) is as an escalation point for data ethics issues. The panel is convened as needed. As of April 2024, it had not been convened.

- The Generative AI Senior Executive Service Band 2 Group (Gen AI B2 Group) was established in November 2023 to oversee the ATO’s use of generative AI technology. It is responsible for the ATO’s ‘Use of publicly available generative AI technology policy’. The Gen AI B2 Group61 reports to the Risk Committee.

Accountable officials and other expertise

2.40 The Policy for the responsible use of AI in government requires that entities designate accountability for implementation of the policy to accountable officials by 30 November 2024.62 The responsibilities of accountable officials ‘may be vested in an individual or in the chair of a body. The responsibilities may also be split across officials or existing roles (such as Chief Information Officer, Chief Technology Officer or Chief Data Officer) to suit agency preferences’. In November 2024, the ATO appointed its Chief Data Officer (Deputy Commissioner Smarter Data) as its accountable official.

2.41 The National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government outlines that AI ‘requires a combination of technical, social and legal capabilities and expertise … such as data and technology governance, privacy, human rights, diversity and inclusion, ethics, cyber security, audit, intellectual property, risk management, digital investment and procurement’.63

Responsibilities and accountabilities — system level

2.42 The accountability principle of Australia’s AI ethics principles states that ‘people responsible for the different phases of the AI system lifecycle should be identifiable and accountable for the outcomes of the AI systems, and human oversight of AI systems should be enabled’.64

2.43 The ATO’s data stewardship model is about defining the accountabilities and responsibilities around the management and oversight of the ATO’s data assets. The ATO has identified that further work is needed to fully implement stewardship for AI outputs.

Recommendation no.2

2.44 The ATO clearly define and communicate enterprise-wide organisational structures and governance arrangements supporting its adoption of AI, including defining accountabilities and responsibilities at the model and system level.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.45 The ATO will define and communicate enterprise-wide organisational structures and governance arrangements supporting its adoption of AI, including defining accountabilities and responsibilities at the model and system level.

Does the ATO have effective arrangements for managing risks in relation to the adoption of artificial intelligence?

There are risks related to the adoption of AI at various levels at the ATO.

- The ATO has two enterprise risks that relate to AI due to their focus on data and analytics. These risks are ‘above tolerance’.

- The ATO has risk assessment processes that apply to its adoption of AI. It has identified that these are not sufficient for AI-specific risks, and it is working to introduce processes that better support the management of AI risks.

- The ATO has a risk-based approach to approving the use of publicly available generative AI technologies by ATO officers.

2.46 An accountable authority must establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight and management and internal control for their entity.65 The ATO is required to comply with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. The National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government outlines that ‘risks should be managed throughout the AI system life cycle’ and that ‘monitoring and feedback loops should be established to address emerging risks, unintended consequences or performance issues’.66

Enterprise risk management — AI-related enterprise risks

2.47 The ATO’s Risk Management Chief Executive Instruction67 and Enterprise Risk Management Framework (ERMF) set out the ATO’s enterprise-wide approach to risk management. The ATO has a register of its enterprise risks.68

2.48 The ATO advised the ANAO on 12 March 2024 that two of its enterprise risks are related to AI due to their focus on data and analytics (see Table 2.4).69 This section focusses on these two risks.

Table 2.4: The ATO’s AI-related enterprise risks

|

Description of risk event |

Control effectivenessa |

Risk levelb |

Tolerancec |

|

Maximising the value of data and analytics |

|

|

|

|

There is a risk that the ATO does not effectively utilise data and analytics capabilities, caused by inappropriate investment in or maintenance of data and analytics foundations and capabilities, resulting in sub-optimal decision-making, organisational inefficiency and uneconomic outcomes. |

Partially effective |

High |

Above tolerance as target risk leveld is ‘medium’ |

|

Misuse of data and analytics |

|

|

|

|

There is a risk that the ATO (or those the ATO shares data or analysis with) does not lawfully or appropriately use its data and analysis, caused by a failure in its or its partners’ data and analytics governance, resulting in adverse impacts on individuals, loss of revenue and/or loss of public trust and confidence and reduction in willing participation. |

Partially effective |

Medium |

Above tolerance as target risk leveld is ‘low’ |

Note a: Controls are assessed as: effective; partially effective; ineffective; and insufficient evidence.

Note b: The risk level is based on the consequence if the risk is realised and the likelihood that the risk will be realised. The ATO’s risk levels categories are: very low; low; medium; high; very high and extreme. The ATO updated its risk level and consequence category names in August 2024.

Note c: The tolerance rating is either within tolerance or above tolerance. Above tolerance means that the risk rating is higher than what is acceptable.

Note d: Target risk refers to the level of risk willing to be tolerated for a risk.

Source: ATO documentation.

2.49 The ATO’s risk appetite statement states that it is willing to accept higher levels of risk where there is a clear opportunity to realise benefits and where risks can be controlled to acceptable levels. It is less willing to accept risk where it is not clear that benefits will be realised or where risks are unable to be controlled to acceptable levels. The risk appetite statement provides a sound basis to guide its approach to managing the AI-related enterprise risks. The ATO has identified that failing to appropriately treat the ‘maximising the value of data and analytics’ risk could result in ‘sub-optimal outcomes or opportunities lost’ and failing to appropriately treat the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk could result ‘in actual harm’.

Responsibilities

2.50 Roles for managing the AI-related enterprise risks are defined in accordance with requirements. Under the ERMF, risk owners of enterprise risks are ‘personally accountable’ for risk management, provide direction on relevant risk management activities and oversee the status of risks, controls and treatment strategies. The Deputy Commissioner Smarter Data is the risk owner for the two AI-related enterprise risks. In accordance with the ATO’s ERMF, each of these risks also has a risk manager, and control and treatment owners.

Risk assessment

2.51 The ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk was categorised as an enterprise risk in March 2023. The ‘maximising value of data and analytics’ risk was updated in May 2023 to include ‘analytics’ as part of its scope. The following paragraphs examine the management of these risks.

Maximising the value of data and analytics risk

2.52 There were nine controls allocated to the ‘maximising the value of data and analytics’ risk. Overall, these controls were rated as ‘partially effective’. One of the ATO’s controls had a direct link to the ATO’s adoption of AI and was about the implementation of the five A&AI strategy use cases. This control was identified as supporting the ATO to leverage investment across the organisation by providing access to A&AI solutions more efficiently and quickly.

2.53 The ATO had not assessed the effectiveness of this control due to ‘insufficient evidence’.70 The ATO’s assessment indicated a lack of progress in implementing the use cases of the A&AI strategy.

2.54 Overall, the risk was rated as high. The tolerance for this risk (target risk level) was ‘medium’ which means that this risk was above tolerance. As controls were ‘partially effective’ and the risk was tracking above tolerance, the ATO has allocated a risk treatment which focusses on the ATO’s Data and Analytics Strategy, including delivering the A&AI strategy. The treatment owner for this risk was the Deputy Commissioner Smarter Data. The due date for this treatment was listed as 31 December 2024 in the enterprise risk register and 31 December 2027 in the risk assessment and treatment plan. The ANAO sought clarification from the ATO about the due date for this treatment. The ATO advised the ANAO on 16 September 2024 that it anticipates that both enterprise risks will be within tolerance by the completion of the next Data and Analytics Strategy which is planned for 2029.

Misuse of data and analytics risk

2.55 There were 17 controls allocated to the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk. These controls were rated as ‘partially effective’ overall. One control was directly relevant to the ATO’s adoption of AI — the implementation of a model ethics assessment process for models containing automation, AI or machine learning. It was described as aiming to detect the possible misuse of data and analytics, including AI, in the design and implementation of models. This control was assessed as having ‘insufficient evidence’ to be able to be assessed as the model ethics assessments were in pilot phase at the time of assessment. See paragraph 2.81 for further discussion on the model ethics assessment process.

2.56 Overall, the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk was rated as medium. The tolerance for this risk was ‘low’ which means that this risk was above tolerance. As controls were ‘partially effective’ and the risk was tracking above tolerance, the ATO has allocated a treatment for the risk — the same treatment as for the ‘maximising the value of data and analytics’ risk which relates to the implementation of the ATO’s Data and Analytics Strategy and the A&AI strategy.

Shared risks

2.57 The ATO has categorised the two AI-related enterprise risks as shared71 with other Australian Government entities that receive or use its data or analytical outputs. According to the ATO’s guidance, shared risks require shared oversight and management between entities.72 Arrangements for managing these shared risks have not been established.

Monitoring and review

2.58 The ATO’s risk management guidance states that risks should be monitored on an ongoing basis and periodically reviewed. Monitoring and review should be planned, with clearly defined responsibilities. The ‘maximising the value of data and analytics’ risk should have been reviewed in August 2024 and the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk in February 2024. Both risks were reviewed in December 2024.

2.59 Commonwealth entities are required to establish processes for identifying, managing and escalating emerging risks.73 The ATO has identified that of its data and analytics activities74, AI activities have the highest overall risk, with a particularly high risk for the ‘misuse of data and analytics’ risk. This is due to the combination of autonomy and adaptivity and lack of controls. This highlights the importance of ongoing monitoring and review of the two AI-related enterprise risks as they are likely to continue to evolve.

2.60 ATO risk management guidance outlines that reporting on risks is ‘an integral part of governance’.

- There was no structured and regular reporting on the two AI-related enterprise risks to the risk owner. The ATO advised the ANAO in January 2025 that since June 2024 the risk manager for the two AI-related risks ‘generally meets with the risk owner on a fortnightly basis’.

- In November 2023 and September 2024, the risk owner for the two AI-related risks provided an update to the Risk Committee, including an overview of the risks, and work underway to mature controls and treatment strategies. The September 2024 reporting provided more information about the environmental factors and drivers of the risks, the controls in place and the treatments needed to bring the risks in tolerance.

- The ATO’s Audit and Risk Committee receives reporting on all enterprise risks, including the two AI-related enterprise risks. This reporting has improved over time.

Recommendation no.3

2.61 The ATO review the ‘misuse of data and analytics enterprise’ risk in accordance with its enterprise risk management framework and risk appetite, and update and incorporate controls relating to the impact of AI on this risk.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.62 The ATO will review the misuse of data and analytics enterprise data risk in accordance with the ATO Risk Management Framework and update and incorporate controls relating to the impact of AI.

Arrangements for managing AI business risks

2.63 Under the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy, ‘risk management must be embedded into the decision-making activities of an entity’.75 The National framework for the assurance of artificial intelligence in government outlines that the use of AI should be risk based.76 According to the OECD:

[o]rganisations should devise, adopt and disseminate a combination of risk management policies that articulate an organisation’s commitments to trustworthy AI. These policies should be embedded into an organisation’s oversight bodies.77

2.64 At the ATO, business risks are all other risks (i.e. not enterprise) associated with day-to-day operations. Business risks may be at the group, business line, team or project level. There is no central register of business risks, although these risks can be added to the enterprise register. The ATO advised the ANAO on 12 April 2024 that there are no AI-related business level risks in the enterprise risk register. The ATO also advised that risks may be managed at the project level. It did not identify any such risks.

Risk management throughout the AI system lifecycle

2.65 The ATO’s organisational risk appetite statement notes that it is willing to accept higher risk if there are clear opportunities and where risk can be controlled to an acceptable level. Except for the process to assess publicly available generative AI tools for use by ATO officers (see paragraphs 2.69 to 2.73), as of July 2024, the ATO did not have a defined process for assessing the risk level of AI models and systems.78

2.66 The ATO has identified that its current arrangements ‘do not sufficiently capture AI specific risks’. As at July 2024, the ATO was developing AI risk management guidance which is planned to include an AI risk assessment approach. The guidance will aim to assist ATO officers assess whether proposed AI systems are within risk tolerance and whether governance is being applied proportionate to the risk. The ATO’s desired future state includes that governance and processes for AI will be tailored and based on assessed risk.

2.67 As at July 2024, the ATO had a variety of processes that capture or assess risks related to AI. This includes: data and analytics ethics assessments79; privacy impact assessments; security risks assessments; and risk assessments as part of project management and model design documentation.