Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Planning and Governance of COVID-19 Procurements to Increase the National Medical Stockpile

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit is one of five performance audits conducted under phase one of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The Department of Health (Health), with the assistance of the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER), undertook emergency procurements of personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators and COVID-19 test kits for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS).

- The Australian Parliament and public require assurance that public resources were used properly and that the procurement requirement has been met.

Key facts

- The NMS is a reserve of medicines, vaccines, antidotes and PPE for use in response to a public health emergency, to be deployed as a supplement to state and territory stockpiles.

- At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic the NMS was valued at $123 million.

What did we find?

- The procurement requirement for PPE and medical equipment was met or exceeded. Elements of Health’s procurement planning for the NMS could be improved.

- Health’s pre-pandemic procurement planning for the NMS was partially effective.

- Health’s and DISER’s planning and governance arrangements for the procurements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were effective.

- Procurement of PPE for the NMS was approximately aligned with overall national health system demand.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made four recommendations to Health aimed at basing NMS procurement decisions on key strategic risks; collaborating with states and territories to document procurement priorities; developing a mechanism for sharing stockpile information between jurisdictions; and establishing protocols for emergency NMS procurements.

$3.23 billion

Total funding provided to Health between March and May 2020 to procure PPE and medical equipment

54

Number of contracts for PPE, medical equipment and COVID-19 test kits as at 31 August 2020

1.3 billion

Total items of PPE procured for the NMS as at 31 August 2020

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. From February 2020 the Australian Government commenced the introduction of a range of policies and measures in response to the emergence of COVID-19 that included:

- travel restrictions and international border control and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement of critical medical supplies.

2. The National Medical Stockpile (NMS) is a reserve of pharmaceuticals, vaccines, antidotes and personal protective equipment (PPE) for use during the national response to a public health emergency that could arise from natural causes or terrorist activities. It is meant to supplement state and territory supplies in a health emergency. Between 3 March and 1 May 2020 $3.23 billion in funding was provided to the Australian Government Department of Health (Health) to procure medical supplies, namely PPE and medical equipment, for the NMS. Procurement activity peaked in April 2020, with the last contract for NMS supplies prior to 31 August 2020 entered into on 14 August 2020.

3. The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) began assisting Health with the COVID-19 NMS procurements on 2 March 2020. On 18 March 2020 the Acting Secretary of Health decided, under paragraph 2.6 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), that the CPRs would not apply to the COVID-19 NMS procurements. Paragraph 2.6 allows the accountable authority to decide this in a range of circumstances, including to protect human health.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This audit is one of five performance audits conducted under phase one of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that will focus on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.1

5. A challenging procurement environment, as well as the decision to not apply the CPRs, created additional risks to the proper use of public resources and achievement of procurement outcomes for the COVID-19 NMS procurements. The Australian Parliament and public require assurance that the procurement requirement has been met through the planning and governance arrangements that Health and DISER established in conducting the procurements.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit examined whether the COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement was met through effective planning and governance arrangements.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Was pre-pandemic procurement planning for the NMS effective?

- As part of the Australian Government’s COVID-19 response, was the planning and governance of the NMS procurements effective?

- Was the COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement for PPE and medical equipment met?

Conclusion

8. The COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement for PPE and medical equipment was met or exceeded. Elements of Health’s procurement planning for the NMS could be improved.

9. Health’s pre-pandemic procurement planning for the NMS was partially effective. Procurement planning was partially risk-based. Agreement with states and territories about stockpiling responsibilities was not documented and stockpile information was not adequately shared. There were no protocols for emergency procurements.

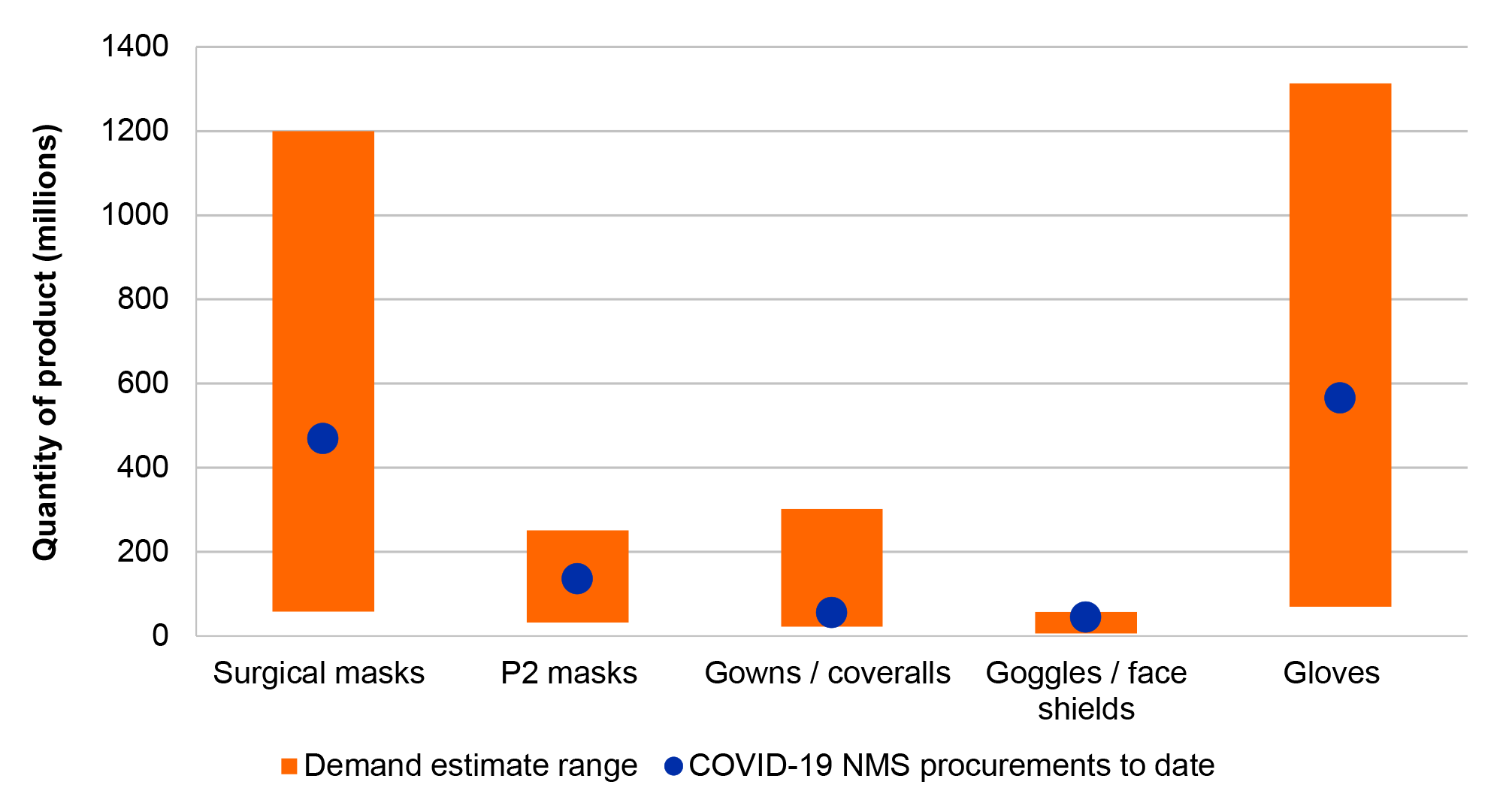

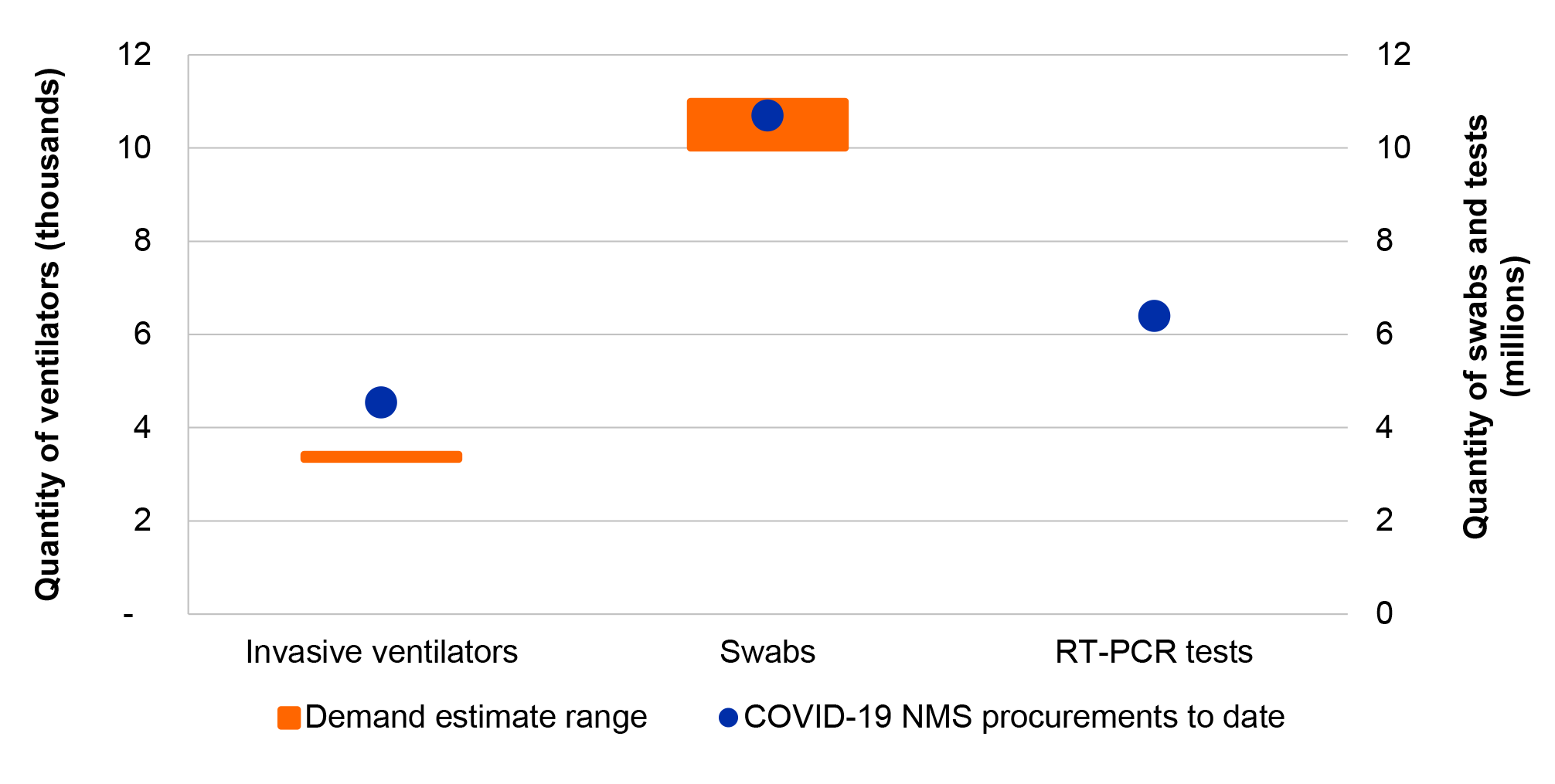

10. Health’s and DISER’s NMS procurement planning and governance arrangements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were effective. Both entities had elements of a plan for meeting the requirement, established fit for purpose governance arrangements and considered risks.

11. The COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement was not clearly specified for PPE, swabs and COVID-19 tests. Procured quantities for the NMS were approximately aligned with overall national health system demand estimates for all items where demand modelling was undertaken, suggesting the procurement requirement was met or exceeded.

Supporting findings

Pre-pandemic procurement planning for the National Medical Stockpile

12. Health’s procurement planning for the NMS was partially risk-based. A strategic plan for the NMS did not consider procurement in detail, but did establish an overarching framework for key risks to be considered in management decisions, including procurement decisions. A Replenishment Plan set out procurement priorities that were focused on chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) threats and an influenza pandemic and did not address other potential health threats. Procurement planning documents did not provide a risk-based rationale for the quantity of PPE to be procured and held within the NMS and Health did not consider potential risks to PPE supply chain security during an emergency.

13. NMS procurement planning was not adequately coordinated with the states and territories in light of the objective to ‘supplement’ and work ‘in concert’ with state and territory stockpiles. Health does not have a documented agreement with the states and territories about stockpiling and there was a lack of regular and systematic information sharing about stockpiles with the states and territories.

14. Strategic planning for the NMS did not adequately prepare for emergency procurements. High level plans for responding to a disease occurrence do not provide specific guidance on conducting emergency NMS procurements and, despite the NMS’s core function as an emergency mechanism, Health had not developed specific protocols for conducting these procurements or for coordinating the multi-jurisdictional procurement response.

Planning and governance of COVID-19 National Medical Stockpile procurements

15. Health’s planning for the COVID-19 NMS procurements was fit for purpose. It did not develop a strategic or operational procurement plan but elements of a plan — such as definition of objectives, timeframes and procurement method — were incorporated in documentation. DISER’s operational planning for the procurement activities was also fit for purpose. It did not develop an overarching operational plan for its involvement but taskforces developed, used and shared process maps, templates and checklists to guide procurement activities.

16. Health’s and DISER’s internal and cross-departmental governance arrangements for the COVID-19 NMS procurements were fit for purpose. Respective roles between Health and DISER were not documented but were broadly understood. Both departments used a flexible taskforce approach to manage the procurements, involved procurement advisory services and actively engaged executive management in decision-making. There was a process for managing conflicts of interest in both departments, however, a requirement for specific conflict of interest declarations for the NMS procurements was introduced late and incompletely adhered to.

17. Health and DISER assessed and treated risks to the proper use and management of public resources in the COVID-19 NMS procurements and to procurement outcomes. Health did not conduct an overarching assessment of risk in relation to COVID-19 NMS procurement activity and risk treatments for individual procurements were not well documented. Both departments considered procurement risks in a number of their implementation activities.

18. When conducting the COVID-19 NMS procurements, Health applied the CPRs appropriately. Health officials informed the delegate of the use of paragraph 10.3(b) of the CPRs when seeking approval to commit funds through limited tender and sought the approval of the Acting Secretary of Health to invoke paragraph 2.6 to not apply the CPRs to the procurements. No alternative procurement framework for the COVID-19 NMS procurements was specified by the Acting Secretary. The Acting Secretary revoked the application of paragraph 2.6 when it was no longer necessary.

Meeting the COVID-19 National Medical Stockpile procurement requirement

19. In formulating the NMS procurement requirement, demand estimates and supply chain issues were considered by Health and DISER. However, due to the dynamic situation and late and partial information about existing national stocks of PPE, only the ventilator procurement requirement was specified clearly. In the absence of a specified procurement requirement, Health and DISER officials understood the requirement was to procure as much PPE as possible, as quickly as possible.

20. The NMS procurement requirement for invasive ventilators was exceeded. In the absence of a specific procurement target for PPE and swabs, the ANAO compared procurements of PPE and swabs to national health system demand estimates and found that the NMS procurement requirement for PPE and swabs was met, or exceeded once procurements by other actors including the states and territories are taken into account. The ANAO was unable to determine if the procurement requirement for COVID-19 tests was met due to no specified requirement or comparable demand estimates.

Summary of entity responses

21. Health’s and DISER’s summary responses to the report are provided below and their full responses are at Appendix 1. State and territory health departments’ responses to a report extract are also shown at Appendix 1.

Department of Health

The Department of Health (the department) notes the findings in the report and agrees with the recommendations relating to COVID-19 procurement for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS).

As for many people across Australia and the world, 2020 has been an extraordinary year which has seen a 1-in-100 year pandemic ravage Australia’s economy and put incredible pressure on Australia’s health system, especially its health professionals. The department has been at the forefront of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including being focused on procuring the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical equipment and supplies to support Australia’s national and collaborative response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the start of the pandemic to 30 October 2020, the department dispatched from the NMS:

- Over 78 million masks (both surgical and P2/N95 respirators), including:

- Over 43 million to states and territories; and

- Nearly 19 million to aged care.

- Over 12 million gloves;

- Over 5 million gowns; and

- Over 4.6 million goggles/face shields.

As part of this national health response, the traditional role of the NMS pivoted to provide additional assistance to ensure critical supplies could be procured and utilised in support of the frontline response. Unlike what we are sadly seeing internationally, our national response has seen a significant reduction in the impact of the novel coronavirus, notwithstanding the tragic passing of 907 people in Australia (as at 23 November 2020).

It was pleasing to note the ANAO found that the procurement requirement for PPE and medical equipment was met or exceeded, and procurement of PPE for the NMS was approximately aligned with overall national health system demand. Australia has not, during this pandemic, been in a position where clinically recommended PPE has not been able to be supplied to a health worker. This is not the case for many other countries in the world.

I am very proud of the Department of Health’s contribution to this pandemic response and the extension of the NMS to support the health response has been a key part of this.

The department notes the ANAO has identified areas where improvements can be made, including pre-pandemic planning, collaboration and establishing emergency procurement protocols for the NMS.

The department will work through each of the areas identified by the ANAO and notes the NMS Review, which is already underway, will also take these findings into account along with other Government initiatives. Once the review is complete, the department will seek a decision from Government on the role of the NMS into the future.

For the first time in its history, the National Incident Room has been continuously operating for 12 months and the department continues to support the COVID-19 pandemic response. The department recognises that part of the response is taking into account the lessons that can be learnt on how things can be done better for the next day and the future. Even the smallest improvements to communication and procedures can make a huge difference during the reality of a national crisis.

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources

The department notes the audit’s recommendations relating to the Department of Health, and the key messages for all Australian Government entities in respect of governance and risk management.

The department acknowledges the report findings which confirm — inter alia — that the procurement requirement for personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical equipment was met or exceeded, and that both the department’s and the Department of Health’s procurement planning and governance arrangements were effective.

The COVID-19 pandemic posed many challenges. The department was pleased to support the Department of Health in procuring vital medical supplies to keep Australians safe.

I thank the Australian National Audit Office for its report and for the important work it is doing to provide assurance to the Parliament and Australian people about the proper use of public resources.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.23

Health’s business as usual procurement planning for the NMS be based on an analysis of strategic risks and threats, including a range of potential health emergencies, and the risk to the surety of supply chains for stockpiled items, including personal protective equipment.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.34

Health seek jurisdictional agreement about, and document, the respective objectives of the Commonwealth and state and territory stockpiles and the roles and responsibilities of each jurisdiction, including for stockpiling specific items.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 2.40

Health establish a mechanism for regular sharing of information between jurisdictions about stockpile inventories that will function in both business as usual and emergency conditions.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 2.46

Health put in place a strategic procurement, management and distribution plan for the NMS that includes protocols for emergency procurements.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages that have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of all Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. On 21 January 2020 the Australian Government listed COVID-19 as a disease of pandemic potential under the Biosecurity Act 2015.2 The World Health Organisation declared COVID-19 to be a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ on 30 January 2020.

1.2 From February 2020, the Australian Government commenced the introduction of a range of policies and measures in response to the emergence of COVID-19. On 18 March 2020, in response to the pandemic in Australia, the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia declared that a human biosecurity emergency exists.3

1.3 The Australian Government’s health and economic response has included:

- travel restrictions and international border control and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement of critical medical supplies for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS).

1.4 4With the release of the 2020–21 Budget on 6 October 2020, the Australian Government reported it had committed $507 billion in overall support since the onset of the pandemic, including $272 billion over five years (2019–20 to 2023–24) in direct economic and health support.

The National Medical Stockpile

1.5 The National Medical Stockpile Strategic Plan 2015–19 states that the purpose of the NMS is to be a ‘strategic reserve of pharmaceuticals, vaccines, antidotes and personal protective equipment (PPE) for use during the national response to a public health emergency which could arise from natural causes (risks) or terrorist activities (threats).’ The NMS is intended to supplement state and territory supplies in a health emergency. In ‘non-emergency conditions, or business as usual’, the operational goal of the NMS is to ‘maintain capability for immediate deployment within an emergency’, using a ‘cost effective and risk appropriate system for operations.’

1.6 The Australian Government Department of Health (Health) manages the NMS. The Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) advises the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council on health protection matters and mitigates emerging health threats related to infectious diseases, the environment and natural and human made disasters.5 The AHPPC provides policy oversight for the NMS.

1.7 The NMS is a potential response measure in a variety of national health response plans, including: the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI); the National Health Emergency Response Arrangements; the Health Chemical Biological Radiological Nuclear Incidents of National Consequence; the Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance; and, more recently, the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) (the COVID-19 Plan).

1.8 The NMS was established in 2002 as a reserve of medical supplies for use against potential chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) threats.6 Since its establishment the purpose and use of the NMS has changed to reflect evolving public health risks and national security threats. After outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and H5N1 influenza (avian flu) in 2004 in East Asia, the Australian Government allocated $124 million to the NMS for the purchase of anti-viral medicines. In 2005–06 the Australian Government released the AHMPPI and provided $135 million to the NMS to expand its capacity to respond to an influenza pandemic, including through the purchase of antivirals. The NMS was valued at $117 million at 30 June 2019 (Figure 1.1) and $123 million at 31 December 2019 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1: Purchases, deployments, impairments and value of the NMS, 2004–2019

Note: All values at 30 June. Impairment refers to a permanent reduction in the value of the NMS due to damage, expiry or other loss of functionality of NMS supplies. This does not include items that have been deployed or sold.

Source: Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) analysis of Department of Health annual reports.

1.9 At 31 December 2019 the NMS contained PPE valued at about $11 million (nine per cent of the total value) and medical equipment valued at $28,000 (less than one per cent).

Figure 1.2: Value of product categories held in the NMS, 31 December 2019

Source: ANAO analysis of NMS inventory reconciliation.

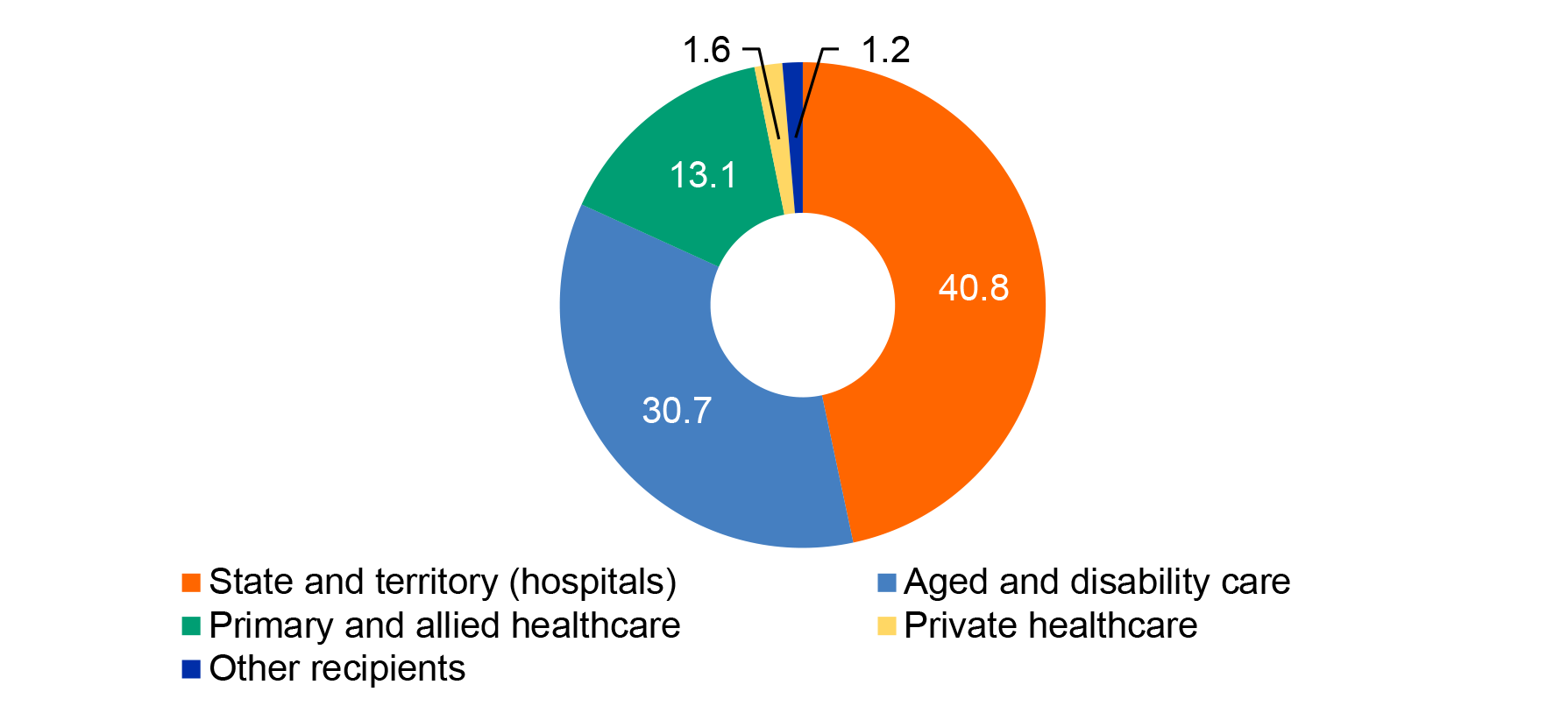

1.10 In 2009–10 an outbreak of swine flu in Australia led to the first large scale deployment of the NMS; about 900,000 courses of antivirals and 2.3 million items of PPE were distributed to healthcare workers and Australian border agencies. In January 2020, 3.5 million P2/N95 respirators (P2 masks) were distributed from the NMS as part of the Australian Government’s response to a bushfire emergency in parts of Australia; this was the first time the NMS had been used for a natural disaster. As part of the COVID-19 response, between 29 January and 28 August 2020, 87.4 million items of PPE and medical equipment were deployed from the NMS to state and territory governments and public hospitals; other frontline health workers, including general practices and community pharmacies; residential aged care facilities and disability settings in the event of an outbreak; and Commonwealth agencies. Figure 1.3 shows the number of items deployed to five categories of recipient.

Figure 1.3: Number of NMS items deployed (millions) by recipient type, 29 January to 28 August 2020

Note: ‘Private healthcare’ includes private hospitals and pathology. ‘Aged and disability care’ includes public and private residential aged care facilities. ‘Other’ includes Commonwealth agencies and testing facilities. Excludes PPE and medical equipment humanitarian assistance deployments, pharmaceuticals including antiviral medication, CBRN items and reagents.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health deployment data. The ANAO has not verified the completeness and accuracy of this data.

Procurements for the National Medical Stockpile in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

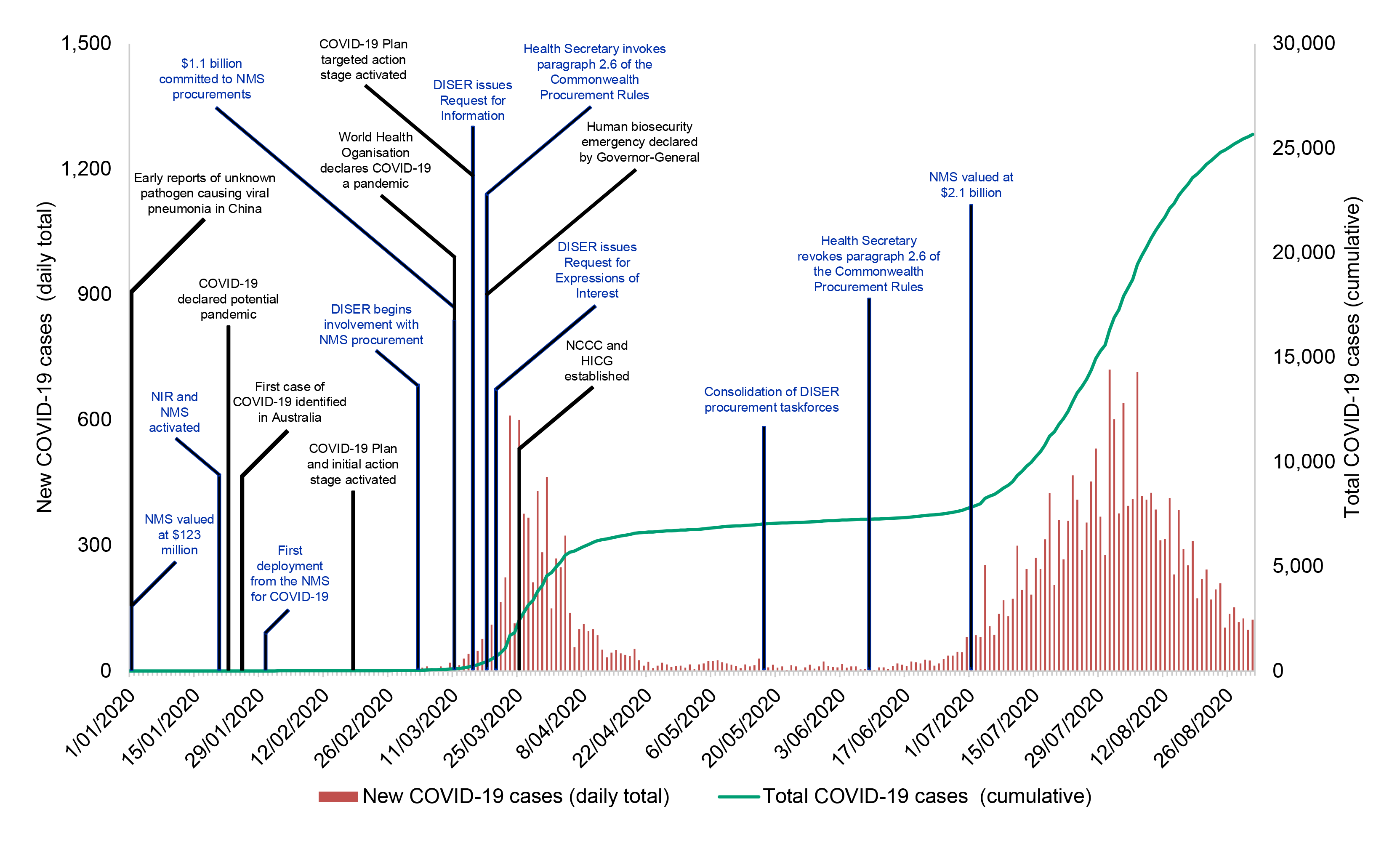

1.11 A timeline for the activation of the NMS as part of the Australian Government’s response to COVID-19 is shown at Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4: Timeline of COVID-19 NMS procurement, to 31 August 2020

Source: ANAO analysis of Health documentation, public information and daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Australia from Australia: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile, Our World in Data, AUS, 2020, available from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/australia?country=~AUS [Accessed 8 September 2020].

1.12 The National Incident Room was activated for COVID-19 on 20 January 2020. In late January Health turned its attention to procurement of essential medical supplies for the NMS. The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) began assisting Health with the COVID-19 NMS procurements on 2 March. Procurement activity peaked in April, with the last contract for NMS supplies prior to 31 August 2020 entered into on 14 August.

1.13 Between 3 March and 1 May 2020 $3.23 billion in funding was provided to Health to procure medical supplies for the NMS. This included $1.88 billion in various Advances to the Finance Minister on 3 March, 9 March, 3 April, and 9 April; and $1.35 billion from other funding measures.7 At 30 June 2020 the NMS was valued at $2.1 billion, 16 times its value at 31 December 2019 (refer Figure 1.2).

1.14 As potential gaps in national supply became evident, Health identified different priority products for NMS procurement and domestic production (refer Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Priority products for procurement and domestic production, March 2020

|

Dates |

Priority 1 |

Priority 2 |

Priority 3 |

|

Priority products as at 9 March 2020 |

Masks (surgical and P2)

|

Gowns Gloves Goggles Hand sanitiser |

Waste bag closure devices (ties) Clinical waste bags Blood and fluid spill kits Mask fit test kits Thermometers |

|

Priority products as at 24 March 2020 |

Masks (surgical and P2) Ventilators Test kits and swabs Gowns Gloves Goggles Hand sanitiser |

Waste bag closure devices (ties) Clinical waste bags Blood and fluid spill kits Mask fit test kits Thermometers |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Health and DISER documentation.

Whole-of-government response to the procurement

1.15 Health, as the accountable agency for the procurement, was the final decision-maker on all procurements and funded, negotiated, executed and managed contracts with suppliers. DISER’s role in the procurements included: identifying areas of supply chain vulnerabilities; sourcing, triaging and assessing offers to supply PPE and other medical supplies to the NMS; conducting due diligence on some offers of assistance; and drafting some contracts.

1.16 A number of other entities were involved in the COVID-19 NMS procurements, including through grants and logistical support to manufacturers and suppliers. These entities included the Department of Defence; Department of Finance; Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; Department of Home Affairs; Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO); and Australian Trade and Investment Commission.

Procurement framework for the COVID-19 procurements

1.17 The keystone of the Australian Government’s procurement policy framework is the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) issued by the Finance Minister under section 105(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act). Commonwealth officials must comply with the CPRs when conducting a procurement. Accountable Authority Instructions also set out entity-specific operational rules to ensure compliance with the rules of the procurement framework.

- ‘Division 1’ rules apply to all procurements. Achieving value for money is the ‘core rule’, or underlying principle, of the CPRs.8

- ‘Division 2’ rules apply to procurements that are at or above a relevant procurement value threshold. These rules specify that procurements must be achieved through open tender except when certain conditions and exemptions apply.

1.18 On 18 March 2020 the Acting Secretary of Health determined that the CPRs did not apply to the COVID-19 NMS procurements by invoking paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs. This provision allows the accountable authority to decide, in a range of circumstances including to protect human health, that the CPRs do not apply. In addition, a number of the procurements conducted prior to 18 March 2020 were exempted from CPR Division 2 rules under paragraph 10.3(b) — for reasons of extreme urgency. Despite the use of these provisions, the proper use and management of public resources in the procurements remained relevant under the PGPA Act.9

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.19 The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This audit is one of five performance audits conducted under phase one of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that will focus on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and one of two performance audits focused on procurements for the NMS.

1.20 A challenging procurement environment, as well as the decision to not apply the CPRs, created additional risks to the proper use of public resources and achievement of procurement outcomes for the COVID-19 NMS procurements. The Australian Parliament and public require assurance that the procurement requirement has been met through the planning and governance arrangements that Health and DISER established in conducting the procurements.

1.21 This audit will assist all Commonwealth entities to consider the effectiveness of their arrangements in identifying and responding to the challenges and risks associated with the rapid implementation of initiatives.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.22 The audit examined whether the COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement was met through effective planning and governance arrangements.

1.23 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Was pre-pandemic procurement planning for the NMS effective?

- As part of the Australian Government’s COVID-19 response, was the planning and governance of the NMS procurements effective?

- Was the COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement for PPE and medical equipment met?

1.24 The audit scope included planning and governance of COVID-19 NMS PPE and medical supply procurements to 31 August 2020. COVID-19 NMS pharmaceutical procurement was not considered. The ANAO is conducting a second audit, due to be tabled in 2021, which is examining implementation of the COVID-19 procurements and deployments of the NMS.

Audit methodology

1.25 The audit involved:

- reviewing entity documentation including contracts and correspondence;

- examining the business information system for NMS inventory management;

- interviewing officers from relevant business areas within Health and DISER;

- interviewing officers from state and territory health authorities; and

- reviewing seven submissions from organisations and individuals with an interest in PPE supply chains in Australia.

For the purpose of this audit, procured products are grouped into four broad categories: masks; other PPE; ventilators; and COVID-19 testing kits and components.10

1.26 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $424,000.

1.27 The audit team was Christine Chalmers, Zoe Pilipczyk, Irena Korenevski, William Richards, Matthew Rigter, Zhiying Wen, Song Khor, Ann MacNeill, Ammar Raza, Lesa Craswell, Rahul Tejani and Deborah Jackson.

2. Pre-pandemic procurement planning for the National Medical Stockpile

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether procurement planning for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS) was effective prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Conclusion

Health’s pre-pandemic procurement planning for the NMS was partially effective. Procurement planning was partially risk-based. Agreement with states and territories about stockpiling responsibilities was not documented and stockpile information was not adequately shared. There were no protocols for emergency procurements.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations to the Department of Health (Health) aimed at improving NMS procurement planning by basing decisions on key strategic risks; collaborating with states and territories to document respective procurement responsibilities; developing a mechanism for sharing stockpile information between jurisdictions; and establishing protocols for emergency procurements.

2.1 The Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI) specifies that the Australian Government is responsible for ensuring that the resources and systems required to mount an effective response to a pandemic are ‘readily available’ through the NMS, among other measures. According to the National Medical Stockpile Strategic Plan 2015–19 (the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan), the NMS is intended to ‘reduce security risks and support rapid responses, and [increase] Australia’s level of self-sufficiency for emergency items during times of high global and domestic demand and service delivery pressures.’

2.2 The ANAO examined pre-pandemic procurement planning for the NMS, comprising whether:

- there was risk-based procurement planning for the NMS;

- procurement planning for the NMS was adequately coordinated with the states and territories given its objective to be a ‘supplementary’ stockpile to state and territory stockpiles; and

- there was planning for emergency procurements.

Was there risk-based procurement planning for the National Medical Stockpile?

Health’s procurement planning for the NMS was partially risk-based. A strategic plan for the NMS did not consider procurement in detail, but did establish an overarching framework for key risks to be considered in management decisions, including procurement decisions. A Replenishment Plan set out procurement priorities that were focused on chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) threats and an influenza pandemic and did not address other potential health threats. Procurement planning documents did not provide a risk-based rationale for the quantity of personal protective equipment (PPE) to be procured and held within the NMS and Health did not consider potential risks to PPE supply chain security during an emergency.

2.3 Procurement planning should be documented and based on analysis of strategic risks and threats. The ANAO examined whether there was a procurement plan in place for the NMS prior to the COVID-19 pandemic emergency and risk was considered in procurement planning.

Was there a procurement plan?

2.4 The 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan provided a high level strategy for the NMS. There is no current strategic plan, however Health advised the ANAO that it considered the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan to be still valid and guiding the operation of the NMS during the 2020 COVID-19 response and that a new policy proposal was in the process of being drafted prior to the start of 2020 for consideration in the May 2020–21 budget. Health advised that the development of a new strategic plan is subject to the outcomes of a review of the composition, modelling and coverage of the NMS, which was requested by the Australian Government in July 2020 and is due to report in June 2021.

2.5 While the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan addresses broad priorities and potential initiatives in relation to procurement, and provides an overarching risk framework for management of the NMS, it does not consider procurement in detail.

2.6 In the 2017–18 budget the Australian Government provided $85 million to the NMS over three years, including $75 million for the replenishment of products.11 In September 2017 a three-year Strategic Replenishment Plan (2017–18 to 2019–20) (the Replenishment Plan) was approved by the Chief Medical Officer (CMO). The Replenishment Plan allocated the budgeted funds under three broad categories of CBRN threat countermeasure items, antivirals and PPE.

Table 2.1: Budget for NMS replenishment, 2017–18 to 2019–20

|

|

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Total budget |

Per cent of total |

|

CBRN items |

$4,234,418 |

$3,738,650 |

$4,000,088 |

$11,973,157 |

16% |

|

Antivirals |

$17,998,780 |

$18,001,026 |

$17,996,829 |

$53,996,635 |

72% |

|

PPE |

$3,015,689 |

$2,992,119 |

$3,009,373 |

$9,017,181 |

12% |

|

Budget allocation |

$25,248,888 |

$24,731,795 |

$25,006,290 |

$74,986,972 |

100% |

Source: Department of Health, Three Year Strategic Plan — Replenishment of National Medical Stockpile (NMS) Items 2017–18 to 2019–20 — As of 5 September 2017, Health, 2017.

2.7 A minute to the CMO seeking approval of the Replenishment Plan indicated three procurement priorities:

- CBRN items ($12 million notional allocation for 19 CBRN items);

- Antivirals ($54 million notional allocation for treatment courses); and

- PPE ($9 million notional allocation for 12 million ‘combo P2/N95 respirators and surgical masks’ (combo masks)).

2.8 Any changes to the Replenishment Plan were to be provided to the delegate for approval. This occurred on several occasions in 2018–20, including a 13 July 2018 request to approve commitment of funds for the replenishment of combo masks.

Was risk considered in procurement planning?

2.9 Various audits and reviews of the NMS since 2007 have commented on consideration of risk in NMS procurement planning. Auditor-General Report No.53 2013–14 Management of the National Medical Stockpile noted modelling to support decision-making on PPE inventory levels had concluded that the PPE stockpile was sufficient for use in a pandemic of moderate impact but recommended that Health update the strategic management plan for the NMS to identify objectives, priorities and strategies and review the operational risk management plan to incorporate emerging risks.12

2.10 The ANAO examined the extent to which risk was discussed in meetings with various advisory bodies to Health that are identified in the NMS 2015–19 Strategic Plan. In the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan, the National Health Emergency Management Standing Committee (NHEMS) of the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) and the CBRN Technical Panel were described as providing input on CBRN related plans and policies, including prioritisation of risks and selection of inventory.13 The NHEMS met on five occasions between March 2018 and June 2020, with an update on the NMS given at three meetings and CBRN threats discussed at two of these meetings. The CBRN Technical Panel did not meet in 2018–19 or 2019–20. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the NMS Advisory Group, the key advisory group to Health on the NMS, met most recently in July 2018 and March 2019.14 The meetings were not minuted, however, meeting agenda and papers do not indicate that risks and threats were to be discussed.

2.11 The ANAO also examined the extent to which risk was addressed in the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan and the Replenishment Plan. The 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan provided a framework for risk consideration in NMS management and identified three levels of risk:

- Foundation risk — risks to the health system in sourcing required medical supplies in a health emergency;

- Strategic risk — risks that should be considered in identifying and prioritising response capability requirements; and

- Operational risk — risks to the management and deployment of stock to effectively enable the implementation of relevant response plans.

2.12 The NMS itself is a treatment for foundation risk. It addresses the risk to human health during a national health emergency posed by insufficient medical supplies.15

2.13 Procurement is most closely aligned to strategic risk in the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan. The key strategic risks relating to procurements of the NMS comprised:

- Product — the logical and justifiable selection of the most appropriate NMS products considering their importance, efficacy, safety and quality standards;

- Identification and assessment — the accurate identification and assessment of potential health emergencies, including where certain items may need to be stockpiled and to what level; and

- Supply — surety and timeliness of procured supply, including the location of manufacturing facilities and the potential for global demand surges.

Product

2.14 In 2017 the NMS held about nine million surgical and five million P2/N95 respirators (P2 masks). PPE such as gowns, gloves and goggles were not held in the NMS prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.15 Neither the Replenishment Plan nor the 13 July 2018 commitment approval minute amending the Replenishment Plan provided a risk-based rationale for the approach to mask or other PPE procurement. The expenditure on antivirals is explained in the Replenishment Plan, however, the rationale for the CBRN prioritisation and quantity, and the allocation to PPE, is not explained. The 13 July minute indicated that budgeted expenditure on PPE was $7.8 million for 10.7 million masks over three years. A rationale for the 13 per cent reduction in expenditure on PPE compared to the Replenishment Plan was not provided. The minute explained that the stock of surgical masks in the NMS would expire in 2021–22 and there was no budget allocation to replace these, but that the combo masks could be used as a surgical mask if required.

Identification and assessment of potential health emergencies

2.16 In 2013 the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing, while commending the Commonwealth and state and territory governments on their influenza pandemic preparedness, noted that it was ‘concerned that planning for a national health emergency involving the spread of infectious disease appears to be solely focussed on pandemic influenza.’16

2.17 To mitigate the risk that potential health emergencies will not be accurately identified and assessed, the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan proposed ongoing threat assessments.

2.18 The possibility and implications of several types of CBRN attack were considered by the NHEMS in July 2018 and June 2019. Health advised the ANAO that threat assessments are also provided to Health and the NMS Advisory Group through annual briefings by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, the Defence Intelligence Organisation and the Australian Federal Police; daily briefings by the Australian Government Crisis Coordination Centre; and briefings when required by the Bureau of Meteorology and Emergency Management Australia. The ANAO found no evidence of discussion of the risk of a pandemic or the implications for stockpiling PPE.

2.19 Threat assessments to inform NMS procurement planning in the two years leading to the COVID-19 pandemic were primarily focused on CBRN threats. There is no evidence that the risk of a pandemic from a pathogen such as coronavirus informed NMS procurement priorities.

Surety of procured supply

2.20 The Global Health Security Index (GHSI) benchmarks health security capabilities for the 195 countries that are ‘States Parties’ to the World Health Organization 2005 International Health Regulations, with a particular emphasis on countries’ preparedness to counter infectious disease threats.17 In October 2019 Australia was ranked fourth out of 195 countries on the GHSI, which includes consideration of whether the country maintains and effectively deploys a stockpile of medical countermeasures. In relation to its stockpile of medical countermeasures, Australia ranked 24th out of 195 countries. Part of the rationale for Australia’s lower ranking on this category, relative to its overall ranking, was that, although Australia maintained a stockpile, it was highly reliant on products that are manufactured overseas. Prior to the pandemic, Australia produced very limited PPE domestically.

2.21 To mitigate the risk of supply chain disruptions during a global health emergency, the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan proposes collecting information for and conducting ‘supply risk assessments’. The Replenishment Plan and September 2017 minute to the CMO considered risks to supply of CBRN and influenza items, such as risk associated with the United States of America controlling the supply of CBRN products and risk to the supply of antivirals in the event of an influenza pandemic.

2.22 There is no evidence that the NMS considered the risk of reliance on overseas manufacturers for NMS stocks of PPE. Health advised the ANAO that it ‘is not responsible for domestic manufacturing policy or the creation of a commercial market for the wide range of PPE and various medical supplies that could potentially be required in any health response scenario.’

Recommendation no.1

2.23 Health’s business as usual procurement planning for the NMS be based on an analysis of strategic risks and threats, including a range of potential health emergencies, and the risk to the surety of supply chains for stockpiled items, including personal protective equipment.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

2.24 Health’s existing risk analysis, including partnering with relevant Government agencies, creates capacity to respond to a wide variety of potential health emergencies, noting the challenge of a novel coronavirus in this case, means by definition the specific pathogen and potential treatment were unknown.

2.25 Opportunities to consider strengthening these activities will be informed by the review of the NMS, along with other government initiatives, such as the Productivity Commission’s review of supply chains.

Was procurement planning coordinated with the states and territories?

NMS procurement planning was not adequately coordinated with the states and territories in light of the objective to ‘supplement’ and work ‘in concert’ with state and territory stockpiles. Health does not have a documented agreement with the states and territories about stockpiling and there was a lack of regular and systematic information sharing about stockpiles with the states and territories.

2.26 In the health sector, state and territory governments procure PPE to help meet health system demand. This may be held in public hospitals and in jurisdictional stockpiles. Private service providers, such as private hospitals and pathology laboratories, also procure PPE and other supplies. According to the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan, the NMS is intended to operate ‘in concert with medical stockpiles held by each state and territory’ by supplementing state and territory supplies in a health emergency. State and territory governments can formally request stock from the NMS in an emergency response, but are expected to maintain their own stockpiles. This co-dependency between the NMS and state and territory stockpiles means that planning for the NMS needs to be undertaken in close collaboration with the states and territories, which is acknowledged by the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan:

The Department cannot effectively manage and deploy the Stockpile without the cooperation and contribution of a range of other stakeholders. This means working directly and in concert with other Australian Government departments and state and territory health authorities and clinicians to ensure a consistent and comprehensive approach to stockpiling capability across Australia.

2.27 Under the AHMPPI, the Australian Government has a responsibility to ‘Coordinate development of policy, in consultation with states/territories regarding the inventory and deployment of the NMS (including conduct of modelling / research required to inform decisions).’18

2.28 A 2011 Health review of Australia’s response to the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic found there was inconsistency between jurisdictions in stockpiling; that policies regarding the rationale, content, allocation and release of stockpiled items was not well communicated between the states and territories and the NMS; and that there was a lack of clarity regarding the respective responsibilities of the NMS and the states and territory stockpiles for providing PPE.19 The Health Industry Coordination Group (HICG), a body established by the Australian Government in March 2020 to facilitate procurement, transport, distribution and domestic production or repurposing of PPE and other medical supplies, noted that during the COVID-19 response in 2020 there were very different expectations for the role of the NMS across states, territories and industry.20

2.29 Health advised the ANAO that states and territories are responsible for stockpiling of PPE, including surgical masks, and other high turnover consumables based on four key reasons:

- the addendum to the National Health Reform Agreement 2020–25 (NHRA)21 indicates that the states and territories are responsible for system management of public hospitals, including hospital services22; it is implied from pricing models that providing hospital services includes the purchase of PPE23;

- state and territories governments can more readily cycle high use inventory, such as PPE, through the health system thereby reducing impairment and waste;

- the focus of NMS expenditure should be where the Australian Government possesses unique leverage in relation to higher cost items, such as P2 masks, which can be purchased in bulk to lower costs; and

- the focus of NMS expenditure should be where the Australian Government possesses unique authority; with respect to strategic CBRN items, only the Australian Government has the legislative authority to import products that are not registered for use in Australia.

2.30 Health also advised the ANAO that the intention to focus on P2 rather than surgical masks in the NMS is because of their potential usage, when compared to surgical masks, in a broader range of emergency settings, and because surgical masks are funded through existing funding arrangements between the states and territories and the Commonwealth under the National Pricing Model established by the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority.24

2.31 The primary mechanism for consulting with the states and territories about stockpiling for health emergencies is the NMS Advisory Group. ANAO analysis of meeting agenda and papers found that discussions are related to NMS holdings at a general level, as well as deployment and warehousing arrangements.

2.32 In December 2016 Health shared a policy paper on the ‘Use of PPE from the NMS’ with NMS Advisory Group members. The paper noted the quantities of masks being held within the NMS and Health’s intention to stockpile P2 masks only, and stated that ‘states and territories will be expected to supply surgical masks during a pandemic response.’ In 2019 Health developed a draft policy discussion paper on a national PPE stockpiling strategy to inform potential changes to the AHMPPI. The paper re-stated Health’s position regarding surgical and P2 masks, noting that its stock of P2 masks was limited and that there was a need for national planning on how stockpiles can support the non-hospital health sector during a pandemic. The paper noted that the outlined NMS mask strategy is consistent with initial discussions held between Commonwealth and state and territory representatives regarding a National Stockpiling Agreement. Although the draft 2019 policy paper was presented to the Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA) it was not endorsed by the CDNA and has not been presented to the AHPPC.

2.33 While the NHRA establishes responsibilities for Australia’s public hospital system, to date, no documented agreement has been reached with the states and territories regarding a national medical supplies stockpiling strategy for a health emergency response, including specific roles and responsibilities for stockpiling. A National Stockpiling Agreement was foreshadowed in the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan but never eventuated. Health advised the ANAO that its position regarding mask and PPE stockpiling is ‘known and is a principle in place within the health system’, but that a stockpiling agreement will be developed as part of a review of the National Health Security Agreement. This was originally scheduled for 2020–21 but has been delayed due to the COVID-19 and other health emergencies; Health has advised the ANAO that consultation with the states and territories will be ‘absolutely essential’ to the review process.

Recommendation no.2

2.34 Health seek jurisdictional agreement about, and document, the respective objectives of the Commonwealth and state and territory stockpiles and the roles and responsibilities of each jurisdiction, including for stockpiling specific items.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

2.35 Health agrees that it is appropriate that all parties document objectives of their stockpiles. The Commonwealth notes that states and territories retain sovereignty of decision making and autonomy to prioritise on matters of budget. Collaboration will be required.

2.36 Health will, where appropriate and possible, continue to provide clarity on responsibilities, such as Commonwealth responsibility for chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear items, and jurisdictional responsibilities such as PPE, as per the National Health Reform Agreement.

2.37 Given the NMS’s role as a ‘supplementary’ stockpile, it is important for emergency planning and responsiveness that Health has a specific understanding of the items and quantities of medical supplies that states and territories hold in their stockpiles, and, conversely, that states and territories understand what is held in the NMS. A 2010–11 Department of Finance review of the NMS recommended better information sharing between Health and the states and territories regarding available inventory and distribution.25

2.38 There is no regular mechanism for collecting or collating data from states and territories on stockpile holdings. In 2016 and May 2019 Health attempted to gather information about items and brands held in jurisdictional stockpiles that were not Commonwealth owned. Following on from the 2019 investigation, at the June 2019 NHEMS meeting there was discussion of whether stock information could be shared among all jurisdictions; Health was to consider this proposal but it was not discussed at the next meeting of the NHEMS in October 2019.

2.39 Health’s information gathering in 2016 showed that New South Wales (NSW), Northern Territory (NT), Queensland (QLD) and Western Australia (WA) were stockpiling PPE. The results of the 2019 investigation, which was partly in response to requests from some states and territories to know more about items held in the NMS, showed that stockpiling across Australia was uneven, particularly in relation to gowns, goggles and gloves (Table 2.2). As this request for information about state and territory stockpiles did not provide or ask for quantities, once the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, it was unclear the extent to which the NMS in combination with other stockpiles would meet potential demand for PPE and other medical supplies.

Table 2.2: NMS and state and territory stockpiled items as reported to Health, May–July 2019

|

|

Jurisdictionsa |

||||||||

|

|

NMS |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLDb |

SA |

TAS |

Vicc |

WA |

|

Masks |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

No stockpile |

|

✔ |

✔ |

No stockpile |

✔ |

|

Gowns/coveralls |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Waste bags |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Thermometers |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

||

|

Goggles/face shields |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

|

||

|

Gloves |

|

|

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

||

|

Spill kits |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

|

|

||

|

Hand sanitiser |

|

|

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

|

||

|

Waste bag ties |

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

||

|

Mask fit test kits |

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

|

|

||

|

Swabs |

|

|

✔ |

|

|

|

|

||

Note a: Does not include PPE and pharmaceuticals held in public hospitals.

Note b: Queensland Health advised the ANAO that in 2015 it commenced a process to increase stockholdings of essential PPE, resulting in the establishment of an ‘active stock management system’, which allowed for PPE in the holdings to be rotated within their expiry period and replenished, rather than a ‘static stockpile’. Queensland Health advised that when the request for stockpile holdings was received in 2019, it was limiting static stockpile holdings to minimise the wastage and disposal costs associated with expired stock. Queensland Health advised Health in 2019 that ‘the majority of our PPE stock is not specifically stockpiled; however we hold a buffer amount over and above normal day to day purposes for periods of unexpected high demand.’

Note c: The Victorian Department of Health and Human Services advised the ANAO that Victoria’s public health system operates in a ‘devolved governance model’ where individual health services are responsible for managing supplies of PPE for their staff and patients, including for emergency events, but that a state supply chain was established in response to COVID-19 to dispatch stock to health services.

Source: ANAO analysis of May 2019 Health ’survey’ of state and territory stockpiles.

Recommendation no.3

2.40 Health establish a mechanism for regular sharing of information between jurisdictions about stockpile inventories that will function in both business as usual and emergency conditions.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

2.41 The Commonwealth agrees that a universal stock holding information system would be beneficial and will progress a comprehensive arrangement with the states and territories.

Did strategic planning for the National Medical Stockpile adequately prepare for emergency procurements?

Strategic planning for the NMS did not adequately prepare for emergency procurements. High level plans for responding to a disease occurrence do not provide specific guidance on conducting emergency NMS procurements and, despite the NMS’s core function as an emergency mechanism, Health had not developed specific protocols for conducting these procurements or for coordinating the multi-jurisdictional procurement response.

2.42 Although emergency procurement is acknowledged as a possibility in the 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan, health response plans such as the AHMPPI do not consider the potential need for procurements for the NMS in the early stages of a pandemic response. The 2015–19 NMS Strategic Plan states that in a health emergency where a required product is not stocked within the NMS an emergency procurement should be initiated where appropriate, but it does not provide further guidance regarding how to conduct that procurement.

2.43 Neither the AHMPPI, the Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance, the 2015-19 NMS Strategic Plan, nor any other planning document sets out operational principles or specific protocols for an emergency procurement of medical supplies for the NMS or for a coordinated national response to procurement in business as usual or emergency conditions.

2.44 On 7 April 2020 Health acknowledged that in the COVID-19 pandemic response there was an urgent need for greater coordination between the Australian government agencies involved in PPE procurement and the states and territories, noting that all were competing for the same products. The HICG concluded that an uncoordinated approach to COVID-19 procurements across jurisdictions caused price rises in some instances, disruption to contracts and a lack of clarity on procurement priorities.

2.45 Having protocols in place prior to an emergency would help ensure that, once a threat is realised, attention can be focused on the emergency response without diverting resources to establishing systems and procedures. Emergency protocols would help ensure that procurements can occur as rapidly as possible and that key governance structures are in place at an early stage thereby optimising their value. Emergency protocols for the NMS might include up to date cross-jurisdictional and cross-entity contact lists, temporary inter and intra-governmental governance arrangements to be implemented immediately, a cross-jurisdictional and departmental communications plan and a strategy for communicating with industry and suppliers, advance identification of a framework for the procurements should paragraph 2.6 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules be invoked, contract templates, channels and vetting arrangements for offers of assistance, checklists for initial procurement activities, record keeping and information management protocols, an up to date list of relevant standards and technical specifications for various types of supplies, and supplier panel arrangements including domestic suppliers.

Recommendation no.4

2.46 Health put in place a strategic procurement, management and distribution plan for the NMS that includes protocols for emergency procurements.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

2.47 Health agrees that it would be appropriate to put in place expanded documentation to record information in relation to emergency procurements that builds on the recently published ANAO and Department of Finance advice.

3. Planning and governance of COVID-19 National Medical Stockpile procurements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether, as part of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic response, the Department of Health (Health) and the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) had effective planning and governance arrangements for the COVID-19 National Medical Stockpile (NMS) procurements.

Conclusion

Health’s and DISER’s NMS procurement planning and governance arrangements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic were effective. Both entities had elements of a plan for meeting the requirement, established fit for purpose governance arrangements and considered risks.

3.1 Modelling in late February 2020, after the COVID-19 pandemic response was activated, indicated national health system demand estimates for masks would be between 250 million and 1.2 billion and Health system demand to 31 December 2020 established in late March for other PPE suggested there would be a need for as many as 161 million gowns and coveralls; 633 million gloves; and 57 million goggles. The government reported to the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee on 11 March 2020 that shortfalls in personal protective equipment (PPE) in jurisdictional stockpiles would be filled by the NMS. This resulted in a large-scale emergency procurement for the NMS, with the Australian government allocating $3.2 billion for the procurements at 31 August 2020 (refer paragraph 1.13).26 This procurement occurred in the context of disrupted global supply chains and a surge in demand and prices for PPE and other medical supplies.27

3.2 Fit for purpose governance and planning arrangements can mitigate risks to the proper use of public resources created by a challenging procurement environment.

3.3 The ANAO examined the planning and governance of the COVID-19 activities within the context of the urgent circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic response, including whether:

- a strategic and operational plan for meeting the COVID-19 procurement requirement was developed;

- fit for purpose governance arrangements for the COVID-19 procurement activities were established;

- risks to the proper use and management of public resources in the procurements were identified, analysed and treated; and

- Health appropriately applied the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) when conducting the COVID-19 NMS procurements.

Was a plan for meeting the COVID-19 procurement requirement developed?

Health’s planning for the COVID-19 NMS procurements was fit for purpose. It did not develop a strategic or operational procurement plan but elements of a plan — such as definition of objectives, timeframes and procurement method — were incorporated in documentation. DISER’s operational planning for the procurement activities was also fit for purpose. It did not develop an overarching operational plan for its involvement but taskforces developed, used and shared process maps, templates and checklists to guide procurement activities.

3.4 Strategic planning includes a consideration of objectives, the key activities involved and the operating environment, with the intention of providing clarity and transparency on the intended outcomes of the activity. Implementation planning is the process of determining how an initiative will be carried out. An implementation plan typically addresses key tasks, roles, responsibilities and timelines for milestones and deliverables, as well as record-keeping protocols.28 The ANAO considered whether Health, as the accountable agency for the procurements, developed a strategic and implementation plan that was fit for purpose and whether DISER, as an assisting agency for the procurements (refer paragraph 1.15), developed an implementation plan that was fit for purpose.

Did Health develop an effective plan for meeting the COVID-19 procurement requirement?

Strategic procurement planning

3.5 Health did not develop a single strategic procurement plan for the COVID-19 NMS procurements. However, elements of a plan were contained in various documents (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Strategic procurement planning components

|

Component |

Health activity |

|

A procurement objective expresses the goals and purpose of the procurement. |

On 11 March Health released a fact sheet that indicated that the objective of the NMS procurements was ‘effective protection of health professionals treating patients [helping] critical health staff avoid infection’ and the prevention of transmission of COVID-19 from patients. |

|

Procurement planning should consider the timeframes for the procurement. |

Health did not establish specific timeframes for the COVID-19 NMS procurement, but noted it should proceed as quickly as possible. |

|

Procurement planning involves selecting an appropriate procurement method, based on the procurement value. |

Health explicitly determined a limited tender procurement method in mid-March although limited tender procurement processes were well underway prior to this. |

|

Estimating the value of procurement helps with assessing procurement risk and determining the procurement method. |

Health did not estimate the total value of the COVID-19 procurements and has noted that this was not possible due to uncertainty over disease transmission and the changing price of key items on a daily basis. Funding was provided incrementally over three months from March 2020 in response to requests to government that outlined the potential costs of additional PPE based on prevailing prices at the time. |

|

Procurement planning should incorporate evaluation. |

Although no evaluation has been planned, Health advised the ANAO that an evaluation of the COVID-19 NMS procurements is being considered and will be conducted once Health’s active engagement in the COVID-19 response is concluded. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Health documentation and the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, April 2019.

Operational procurement planning

3.6 Health did not develop an operational plan for the COVID-19 NMS procurements to guide its activities or the work of DISER. Some elements of an operational plan were contained in various documents, including a process map dated 6 April 2020, which provided instructions to Health officials on the key actions to be taken as part of the procurement process. Some Health officials developed draft guidance for personal or taskforce use, which assigned responsibilities for specific tasks and provided instructions on processes, such as how to action contracts referred by DISER. A contract checklist that included directions for record keeping was developed, but not until most of the procurements had been completed in late May.

Did DISER develop an effective operational plan for meeting the COVID-19 requirement?

3.7 No overarching implementation plan was developed for the DISER procurement activities. Operational planning was managed by each procurement taskforce (refer Figure 3.1), with varying levels of effectiveness. A PPE taskforce developed an operational plan that included a statement of the taskforce’s goal; detailed instructions on the key actions to be undertaken by the taskforce in relation to product sourcing and contract preparation; staff responsibilities against specific PPE products and against particular work activities, including responsibility for approvals at key milestones; and instructions on record-keeping arrangements throughout the process, including shared documents to be updated throughout the work and naming conventions for key documents. This operational plan did not determine any specific timeframes for the activities, which was consistent with DISER’s view that the direction from Health was to ‘procure as much PPE…as possible, as quickly as possible.’ DISER’s mask, ventilator and COVID-19 test kit taskforces did not develop an operational plan of this nature, but implementation planning in the form of templates for email correspondence, process maps, a procurement checklist and staff allocation to specific work tasks were used to organise the work.

3.8 DISER taskforces had different focus areas but shared some planning and operational tools. As part of concluding activities and preparing to hand over remaining work, taskforces developed ‘closure reports’ that explained the overall objectives and strategies of the taskforce, the procurement activities undertaken, the location of records and key lessons learnt.

Were fit for purpose governance arrangements for the procurement activities established?

Health’s and DISER’s internal and cross-departmental governance arrangements for the COVID-19 NMS procurements were fit for purpose. Respective roles between Health and DISER were not documented but were broadly understood. Both departments used a flexible taskforce approach to manage the procurements, involved procurement advisory services and actively engaged executive management in decision-making. There was a process for managing conflicts of interest in both departments, however, a requirement for specific conflict of interest declarations for the NMS procurements was introduced late and incompletely adhered to.

3.9 In a rapidly evolving environment, governance arrangements need to be established that are fit for purpose and that support the entity in fulfilling its responsibilities, including the proper use of public resources. The accountable authority has a critical role in determining what is fit for purpose for the entity. To determine whether Health and DISER had fit for purpose governance arrangements for the COVID-19 NMS procurements, the ANAO reviewed whether:

- roles and responsibilities for the COVID-19 procurements were clearly assigned between and within Health and DISER;

- financial delegations were clear and adhered to;

- procurement advisory services were appropriately involved;

- executive management in both departments were appropriately engaged in procurement decision making; and

- there was a requirement for conflict of interest declarations.

Were roles and responsibilities clearly assigned across entities and within Health and DISER?

3.10 Effective governance and planning arrangements include clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Cross-boundary work requires agreement among stakeholders about the nature of the problems at hand and each party’s respective contribution to addressing these issues, such as through networked governance arrangements.

Roles and responsibilities across entities

3.11 On 2 March 2020 the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet requested that Health and DISER work together on medical, pharmaceutical and PPE stocks. DISER and Health subsequently confirmed that DISER would be responsible for leading a team focused on the procurement of masks and that Health would be the ‘ultimate procurer’.

3.12 Although there was a broad understanding of respective roles, there was no documented agreement on respective responsibilities. On 2 March DISER requested clarification from Health on the role and scope of its work. A proposed memorandum of understanding did not eventuate, but respective responsibilities were determined in subsequent days through emails and meetings. DISER sent its first draft contract for goods for Health’s review and action on 20 March, and on 25 March DISER wrote to Health to confirm DISER’s responsibilities in more detail, specifically in relation to DISER conducting due diligence reviews on suppliers prior to sending goods contracts to Health.29 Health also conducted due diligence on suppliers referred by DISER. In early April Health provided feedback to DISER in which it noted that ‘contracts received from DISER by Health are not always fit for purpose.’ This related to the contract template that DISER was using, with Health using a different contract template developed by its legal service provider, and Health concerns about needing to conduct further follow up with some suppliers thereby impeding rapid execution of contracts. After being advised of this, DISER used Health’s contract template.

3.13 DISER established the Health Industry Coordination Group (HICG) on 23 March to provide a single point of contact for industry and government and to reduce duplication and overlap of functions. In addition, the Health Industry Senior Officials Group was established in March to support efficient procurement of essential items to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic; this was chaired by DISER and attended by officials from the Commonwealth and all state and territory industry departments. Between 25 March and 6 May, the Commonwealth Minister for Industry, Science and Technology met state and territory manufacturing ministers and industry department officials on six occasions in order to, according to DISER, ‘understand PPE procurement arrangements occurring across Australia and focus on developing a coordinated approach to supporting local capability in PPE and other medical supplies.’

Roles and responsibilities within Health and DISER

3.14 Prior to the pandemic response, the NMS was managed by a section comprising seven staff within the Health Emergency Management Branch in the Office of Health Protection. In late January 2020 the National Incident Room was ‘stood up’ temporarily as a separate division, within which was formed the National Medical Stockpile and Finance Branch (NMS Branch), later the NMS Taskforce. An Assistant Secretary was appointed to lead PPE, ventilator and swab procurement work. On 22 July, after most of the procurements had been completed, the National Incident Room Division and Office of Health Protection amalgamated into one division, the Office of Health Protection and Response.

3.15 Test kit procurements were led by the Diagnostic Imaging and Pathology Branch (DIPB) within the Medical Benefits Division at Health, which had specific expertise in and direct engagement with the pathology sector. This division of labour reduced duplication of effort on test procurement. The procurements of swabs, a test kit component, was led by the NMS Branch. The DIPB and NMS Branch communicated regularly but DIPB developed its own procurement and documentation protocols.

3.16 A taskforce approach can be an effective means to develop governance and delivery arrangements in compressed timeframes. Health and DISER both implemented a taskforce approach for the NMS procurements (refer Figure 3.1), with DISER establishing this from the outset of its involvement on 2 March and Health establishing supplementary procurement teams to assist the NMS Branch in late March.

Figure 3.1: COVID-19 NMS procurements taskforce structure

Source: ANAO analysis of Health and DISER documentation.

3.17 Within Health, taskforces (called ‘procurement teams’ by Health) were used to manage surge resourcing requirements. In late March an initial procurement team was established to support the NMS Branch. As work outpaced capacity, by early April two additional procurement teams were established. The three procurement teams — each led by an Executive Level 2 official — drew personnel from across the department, including from the department’s Procurement Advisory Service (PAS). Health advised the ANAO that, at the peak of procurement activity, the NMS Branch, the three procurement teams, dedicated staff from the DIPB and a proposal triage team comprised 35 full time equivalent staff.

3.18 Although the DIPB specialised in COVID-19 test procurement, the NMS Branch and three procurement teams worked across all swab and PPE procurements and contracts on an as-needed basis without specialisation, leading to some duplication and overlap. Activities included due diligence, including of suppliers referred by DISER, and contract development and implementation. All DISER and Health taskforce referrals of draft contracts with suppliers for delivery of masks, PPE, ventilators, test kits and swabs were channelled through the Assistant Secretary, NMS Branch.