Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

COVID-19 Procurements and Deployments of the National Medical Stockpile

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit is one of five performance audits conducted under phase one of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The Department of Health (Health), with the assistance of the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER), procured personal protective equipment (PPE) and other supplies for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS). Health deployed PPE to health, aged care and disability workers.

- The audit will provide assurance to the Australian Parliament and public as to whether the procurements were a proper use of public resources and the deployments effectively met national health system needs.

Key facts

- The NMS is a reserve of medicines and PPE for use in a public health emergency as a supplement to state and territory stockpiles.

- During the pandemic, Health awarded over 50 contracts to 44 different suppliers of PPE and other medical supplies to the NMS.

- The objective of NMS PPE deployments was to protect health workers from infection.

What did we find?

- Procurement processes for the COVID-19 NMS procurements were largely consistent with the proper use and management of public resources. Inconsistent due diligence checks of suppliers impacted on procurement effectiveness and record keeping could have been improved.

- In the absence of risk-based planning and systems that sufficiently considered the likely ways in which the NMS would be needed during a pandemic, Health adapted its processes during the COVID-19 emergency to deploy NMS supplies. Large quantities of PPE were deployed to eligible recipients. Due to a lack of performance measures, targets and data, the effectiveness of COVID-19 NMS deployments cannot be established.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made four recommendations to Health, relating to procurement record keeping, deployment drills, planning and performance assessment.

- The department agreed to the four recommendations.

$2.83 bn

Total value of PPE, ventilators and COVID-19 test kits procured for the NMS from January 2020 to February 2021.

$1.04 bn

Value of contracts awarded to the largest single supplier of PPE to the NMS during the pandemic.

111 m

Items of PPE deployed from the NMS to health, aged care and disability workers between January 2020 and January 2021.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. From February 2020, the Australian Government introduced a range of policies and measures to respond to COVID-19.

2. The National Medical Stockpile (NMS) is a reserve of pharmaceuticals, vaccines, antidotes and personal protective equipment (PPE) for use during a national response to a public health emergency that could arise from natural causes or terrorist activities. Between 3 March and 1 May 2020 $3.23 billion in funding was provided to the Australian Government Department of Health (Health) to procure medical supplies, namely PPE and medical equipment, for the NMS.

3. The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) began assisting Health with the COVID-19 NMS procurements on 2 March 2020.

4. Paragraph 2.6 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) states that the CPRs do not apply to the extent that an official applies measures determined by their accountable authority to be necessary for the protection of human health. On 18 March 2020 the Acting Secretary of Health determined that the CPRs did not apply to the COVID-19 NMS procurements under paragraph 2.6.

5. Auditor-General Report No.22 2020–21 Planning and governance of COVID-19 procurements to increase the National Medical Stockpile concluded that the COVID-19 NMS procurement requirement for PPE and medical equipment was met or exceeded but that elements of Health’s procurement planning for the NMS could have been improved.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. This audit is one of five performance audits conducted under phase one of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the second of two performance audits focused on the NMS.

7. A challenging environment, as well as the decision to not apply the CPRs, created additional risks to the proper use of public resources and achievement of outcomes. The audit will provide assurance to the Australian Parliament and public as to whether the procurements for the NMS were an effective, efficient, economical and ethical use of public resources, and the NMS was deployed effectively to meet national health system needs.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The audit examined whether COVID-19 procurements to increase the NMS were consistent with the proper use and management of public resources and whether COVID-19 deployments of the NMS were effective.

9. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Were the COVID-19 NMS procurements consistent with the proper use and management of public resources?

- Was Health’s deployment of the NMS during the COVID-19 response effective?

Conclusion

10. Procurement processes for the COVID-19 NMS procurements were largely consistent with the proper use and management of public resources. Inconsistent due diligence checks of suppliers impacted on procurement effectiveness and record keeping could have been improved.

11. In the absence of risk-based planning and systems that sufficiently considered the likely ways in which the NMS would be needed during a pandemic, Health adapted its processes during the COVID-19 emergency to deploy NMS supplies. Large quantities of PPE were deployed to eligible recipients. Due to a lack of performance measures, targets and data, the effectiveness of COVID-19 NMS deployments cannot be established.

Supporting findings

COVID-19 procurements

12. Procurement processes were largely effective. The financial delegate committed public funds largely appropriately. Due diligence checks were inconsistent and gave partial assurance about the suppliers’ capability to provide specified goods of a sufficient quality. Health established contract management arrangements to identify non-compliance with contractual terms, including where products were not fit for purpose.

13. Ethical procurement processes were established, although interest declarations were late and incomplete. DISER approached the market in a manner that promoted equitable treatment. While the criteria for triaging offers could have been more transparent in both departments, the contracts awarded by Health were drawn from a range of sources. Efficiency was impacted by the dynamic situation. Procurement processes did not emphasise an economical outcome, but the average unit price paid was aligned with prevailing market prices where these were known.

14. Record keeping for the procurements was partially fit for purpose, which impeded review and transparency. Public reporting of the procurements complied with requirements.

COVID-19 deployments

15. Health’s deployment planning was partially effective. Health collaborated with the states and territories in operational deployment planning. Although some operational risks were managed prior to the pandemic, risks to effective deployment in a pandemic of any magnitude were not sufficiently considered in the years preceding the COVID-19 response. Pre-pandemic planning was based on a narrow definition of stockpile aims and eligibility. Because this did not align with the way in which the NMS was used during the pandemic, operational plans and systems were changed and additional plans developed during the course of the pandemic.

16. Health’s deployment of NMS supplies to various health provider groups during the pandemic was consistent in principle with its responsibilities to these groups under national health emergency agreements. In practice, Health limited eligibility to prioritised sub-groups. Disaggregated and unanalysed data about eligibility outcomes impedes transparency about eligibility decisions.

17. Health needed to adjust its usual deployment processes during the pandemic response because its planning had assumed a narrower set of goods and recipients than applied in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Adjusted systems enabled the deployment of NMS supplies to eligible groups.

18. Health deployed large quantities of PPE to eligible groups during the pandemic. Due to the lack of a performance framework including measures and targets, as well as reliable performance data, it is unclear to what extent these eligible groups received enough PPE of the right type and in time.

Summary of entity responses

19. Health’s and DISER’s summary responses to the report are provided below and their full responses are at Appendix 1.

Department of Health

The Department of Health (Health) notes the findings in the report and agrees with the recommendations relating to COVID-19 procurements and deployments of the National Medical Stockpile (NMS). I fully expect this audit will add to the earlier audit in relation to the National Medical Stockpile published in 2020 to enable Health, and the entire APS, to apply the lessons learned in preparation for future emergency responses.

As I noted in my letter to the ANAO in response to the Report Preparation Paper (RPP), this audit is the second consecutive audit completed by the ANAO into the NMS in less than 12 months. Health supports the transparency created through the audits, and notes they have placed a significant additional burden on the department’s staff while responding to an active, 1–in–100 year pandemic. I am proud of how my staff have stood up, responded and met the challenges before them in the protection of the health of the Australian public and its health workforce.

Noting the challenges faced by the department in responding to a novel coronavirus, it was pleasing to note the ANAO found procurements were largely consistent with the proper use of public resources and NMS processes were adapted during the emergency to deploy to unanticipated recipient groups.

While I acknowledge the changes made to the proposed report in response to the department’s comments on the RPP, I am of the view that the proposed report continues to underplay the environment in which the administration of the NMS occurred and does not sufficiently take account of the context in which the department undertook its procurements and deployments. I consider that any consideration of Health’s activities should fully reflect that the department was managing an entire system approach on the most critical national threat in recent history and responded accordingly. In procurement, due diligence and evaluation was commensurate with the speed necessary to secure goods in the national interest in this highly competitive international market and the risk associated with the procurements.

I also continue to strongly disagree with the ANAO’s assertions that, while “Health deployed large quantities of PPE to eligible groups during the pandemic… it is unclear to what extent these eligible groups received enough PPE of the right type and in time”. As I noted in my response to the RPP, as the Australian Government Department of Health does not employ staff or run hospitals, it is not solely, or even substantially, responsible for the procurement and supply of PPE to frontline health care workers. This is an explicit requirement of health service operators as employers. In addition, I reiterate the fact, as noted in the proposed report, that there is no evidence that any frontline health care worker in Australia was adversely affected by any shortage of clinically required PPE.

I have noted previously that the department pivoted the NMS program to expand and enhance its role in health care equipment supply, and did so quickly enough to ensure that a shortage did not impair health care delivery. This was done with a strong and abiding focus on value for money, with executive engagement internally and across the APS to deliver essential support in an agile and appropriate way. It is an achievement of which I am proud.

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources

The department acknowledges the conclusions relevant to the department which confirm that procurement processes were largely consistent with the proper use and management of public resources. We appreciate that the report recognises the department’s focus on continuous improvement, and the lessons we learned from being part of a rapid implementation situation.

The department notes the audit’s recommendations relating to the Department of Health.

The key messages for all Australian Government entities contained in this report and other recently published reports by the ANAO are being actioned within the department, with specific emphasis on probity measures to be applied in high value or complex procurements, and the management of activity-specific conflict of interest declarations.

The department was pleased to support the Department of Health in its procurement of resources to meet the emerging needs of the National Medical Stockpile during this period of rapid change and supply chain uncertainty.

I thank the Australian National Audit Office for its report, and for the important work it is doing to provide assurance to the Parliament and Australian people about the proper use of public resources and the effective deployment of critical medical supplies.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.73

As a component of the protocols for emergency procurements recommended and agreed to in Auditor-General Report No.22 2020–21, Health include protocols for record keeping that would facilitate reasonable assurance that public resources are being used properly during an emergency procurement.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.24

Health undertake regular deployment drills that test possible deployment scenarios and include all elements of deployment operations.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.31

Health put in place a strategic deployment plan for the NMS that is based on an analysis of risk and is developed in consultation with national health system stakeholders.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.62

Health develop a performance framework for NMS deployments that includes consideration of logistics providers’ and Health’s performance in conducting deployments in different emergency scenarios.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages that have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of all Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Records management

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. From late January 2020, the Australian Government introduced a range of policies and measures to respond to COVID-19.

1.2 Under the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework and the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19 Plan), the Minister for Health is the lead Minister for domestic public health crises and the Australian Government Department of Health (Health) is, along with the state and territory health departments, the primary party to the COVID-19 Plan.1

1.3 With the release of the 2020–21 Budget on 6 October 2020, the Australian Government reported it had committed $507 billion for COVID-19 response and recovery measures from 2019–20 to 2023–24, including $272 billion in direct economic ($257 million) and health ($14 billion) support. The Australian Government’s health response has included procurement of critical medical supplies for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS), which is managed by Health.

The National Medical Stockpile

1.4 The purpose of the NMS is to be a ‘strategic reserve of pharmaceuticals, vaccines, antidotes and personal protective equipment (PPE) for use during the national response to a public health emergency which could arise from natural causes (risks) or terrorist activities (threats).’

1.5 The NMS was established in 2002 as a reserve of medical supplies for use against potential chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) threats. Since its establishment the use of the NMS has changed to reflect evolving public health risks and national security threats. After outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and H5N1 influenza (avian flu) in 2004 in East Asia, the Australian Government allocated $124 million for the NMS for the purchase of anti-viral medicines. In 2005–06 the Australian Government provided $135 million for the NMS to expand its capacity to respond to an influenza pandemic, including through the purchase of antivirals. The NMS was valued at $117 million at 30 June 2019 (Figure 1.1) and $123 million at 31 December 2019.

Figure 1.1: Purchases, deployments, impairments and value of the NMS, 2004 to 2019a

Note a: All values at 30 June. Impairment refers to a permanent reduction in value due to damage, expiry or other loss of functionality of NMS supplies. This does not include items that have been deployed or sold.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health annual reports.

1.6 In 2009–10 an outbreak of H1N1 influenza (swine flu) in Australia led to the first large scale deployment of the NMS. About 900,000 courses of antivirals and 2.3 million items of PPE and other medical supplies were distributed to healthcare workers and Australian border agencies. In January 2020 3.5 million P2/N95 respirators (P2 masks) were distributed from the NMS as part of the Australian Government’s response to a bushfire emergency in parts of Australia. This was the first time the NMS had been used for a natural disaster.

1.7 The NMS was activated to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic on 20 January 2020. In late January Health turned its attention to procurement of essential medical supplies for the NMS. The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) began assisting Health with the COVID-19 NMS procurements on 2 March. Between 3 March and 1 May 2020 $3.23 billion in funding was provided to Health to procure medical supplies for the NMS. This included $1.88 billion in Advances to the Finance Minister on 3 March, 9 March, 3 April, and 9 April; and $1.35 billion from other funding measures.2 At 30 June 2020 the NMS was valued at $2.1 billion, 16 times its value at 31 December 2019.

1.8 The keystone of the Australian Government’s procurement policy framework is the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) issued by the Finance Minister under subsection 105(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act). Commonwealth officials must comply with the CPRs.3 CPR Division 2 rules specify that procurements must be achieved through open tender except when certain conditions apply.

1.9 Paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs states that:

These CPRs do not apply to the extent that an official applies measures determined by their Accountable Authority to be necessary for the maintenance or restoration of international peace and security, to protect human health, for the protection of essential security interests, or to protect national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value.4

On 18 March 2020 the Acting Secretary of Health determined that the CPRs did not apply to the COVID-19 NMS procurements by invoking paragraph 2.6. In addition, three procurements were exempted from CPR Division 2 rules under paragraph 10.3(b) and (d) — for reasons of extreme urgency or when only one particular business can supply the goods.

1.10 As part of the COVID-19 response, between January 2020 and January 2021 Health deployed 111 million items of PPE and medical equipment in around 6300 deployments to state and territory governments; Primary Health Networks; residential aged care facilities and disability providers; and Commonwealth agencies (refer Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Number of NMS items deployed, January 2020 to January 2021a

Note a: The ANAO did not verify the accuracy of this data against uncollated records.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health deployment data and daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Australia from Australia: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile, Our World in Data, AUS, 2020, available from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/australia?country=~AUS [Accessed 26 February 2021].

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.11 This audit is one of five performance audits conducted under phase one of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the second of two performance audits focused on the NMS.5

1.12 A challenging environment, as well as the decision to not apply the CPRs, created additional risks to the proper use of public resources and achievement of outcomes. The audit will provide assurance to the Australian Parliament and public as to whether the procurements for the NMS were an effective, efficient, economical and ethical use of public resources, and the NMS was deployed effectively to meet national health system needs.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.13 The audit examined whether COVID-19 procurements to increase the NMS were consistent with the proper use and management of public resources and whether COVID-19 deployments of the NMS were effective.

1.14 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Were the COVID-19 NMS procurements consistent with the proper use and management of public resources?

- Was Health’s deployment of the NMS during the COVID-19 response effective?

1.15 The audit scope included COVID-19 NMS PPE and medical equipment procurements and deployments. Pharmaceutical procurements and deployments were not considered.

Audit methodology

1.16 The audit involved:

- reviewing entity documentation including contracts, plans and correspondence;

- interviewing officers from relevant business areas within Health and DISER;

- interviewing officers from state and territory health authorities, as well as staff from 11 Primary Health Networks, the National Disability Insurance Agency, several private and public pathology laboratories and two logistics providers;

- conducting a survey of over 600 aged care and National Disability Insurance Scheme applicants to the NMS; and

- reviewing 20 submissions from organisations and individuals with an interest in PPE supply chains in Australia.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $485,000.

1.18 The audit team was Christine Chalmers, Irena Korenevski, Shane Armstrong, William Richards, Yoann Colin, Xiaoyan Lu, Song Khor and Deborah Jackson.

2. COVID-19 procurements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the COVID-19 National Medical Stockpile (NMS) procurements were consistent with the proper use and management of public resources.

Conclusion

Procurement processes for the COVID-19 NMS procurements were largely consistent with the proper use and management of public resources. Inconsistent due diligence checks of suppliers impacted on procurement effectiveness and record keeping could have been improved.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving the Department of Health’s (Health’s) record keeping protocols for emergency procurements. The ANAO also suggested that the proper use and management of public resources would have been better assured through earlier and more consistent application of probity measures (including use of conflict of interest declarations and appointment of probity advisors), greater transparency in selection criteria and a due diligence framework to guide officials.

2.1 Between February 2020 and February 2021 Health procured 595 million surgical masks, 168 million P2/N95 respirators (P2 masks), 53 million gowns, 44 million pieces of eye protection, 82 million pairs of gloves, nine million swabs, six million COVID-19 tests and 4040 invasive ventilators for the NMS.6 Contracts were awarded to 44 suppliers across 53 procurements (refer Appendix 2).7 In this audit, procured and deployed products are grouped into four categories: masks; other personal protective equipment (PPE); COVID-19 test kits and components; and ventilators (refer Appendix 3).8

2.2 Although the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) did not apply for the majority of COVID-19 NMS procurements, Health and the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) were obliged to conduct them in a manner that was consistent with section 15 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). This section states ‘The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must govern the entity in a way that…promotes the proper use and management of public resources for which the authority is responsible…’ The PGPA Act defines ‘proper’ to mean effective, ethical, efficient and economical.

2.3 The ANAO examined procurement activities of Health and DISER in relation to the four concepts of effective, ethical, efficient and economical, taking into account the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic response. In addition, the ANAO examined whether record keeping and reporting of the procurements were fit for purpose. The ANAO analysed 17 of the procurements undertaken between February and August 2020 in detail.9 This comprised five mask, five other PPE, five test kit and two ventilator procurements.

Were procurement processes effective?

Procurement processes were largely effective. The financial delegate committed public funds largely appropriately. Due diligence checks were inconsistent and gave partial assurance about the suppliers’ capability to provide specified goods of a sufficient quality. Health established contract management arrangements to identify non-compliance with contractual terms, including where products were not fit for purpose.

2.4 In March 2020 Health announced that the procurement objective was to increase Australia’s supply of PPE and pharmaceuticals held in the NMS in order to protect health professionals from transmission of COVID-19 from patients. The government decided that all proposals to source or manufacture masks or mask inputs would be ‘closely vetted to ensure products meet standards and provide value for money.’

2.5 In assessing the effectiveness of the procurement processes, the ANAO considered whether:

- Health and DISER undertook due diligence that gave assurance to the financial delegate about the suppliers’ capability to provide the specified goods;

- the financial delegate committed public funds appropriately; and

- Health established and managed supplier contracts to ensure that the agreed quality and quantity of goods were delivered.10

Due diligence checks

2.6 Due diligence is aimed at ensuring that a potential supplier has the legal, commercial and technical abilities to fulfil the procurement requirement. Appropriate due diligence will vary according to the procurement characteristics. The extent of due diligence should be proportionate to the risks involved in the procurement.

2.7 Health did not have a documented framework or protocols for conducting due diligence to guide procurement teams working on the COVID-19 NMS procurements.

2.8 Due diligence planning across DISER varied. A PPE taskforce developed a due diligence checklist used by PPE and mask taskforces. A test kit taskforce used a checklist that documented the outcomes of due diligence and developed a due diligence process map for swab suppliers, which made up most of the category. A ventilator taskforce did not have a documented framework. Improvements to the DISER framework were made over time, including extension of the PPE and mask taskforce checklist to incorporate more elements. Checklists could have been further improved by requiring officials to consider the company’s longevity and experience with manufacturing or distributing the goods in the required volumes. As a part of closure activities, DISER identified other ways in which due diligence could have been better, including specifying a process to be followed by all taskforces.

2.9 Suppliers passing an initial triage stage underwent due diligence checks by procurement taskforces in both departments. The ANAO considered whether due diligence checks resulted in sufficient assurance about the suppliers’ legal, commercial and technical ability to fulfil the requirement prior to entering into contractual arrangements (refer Table 2.1).

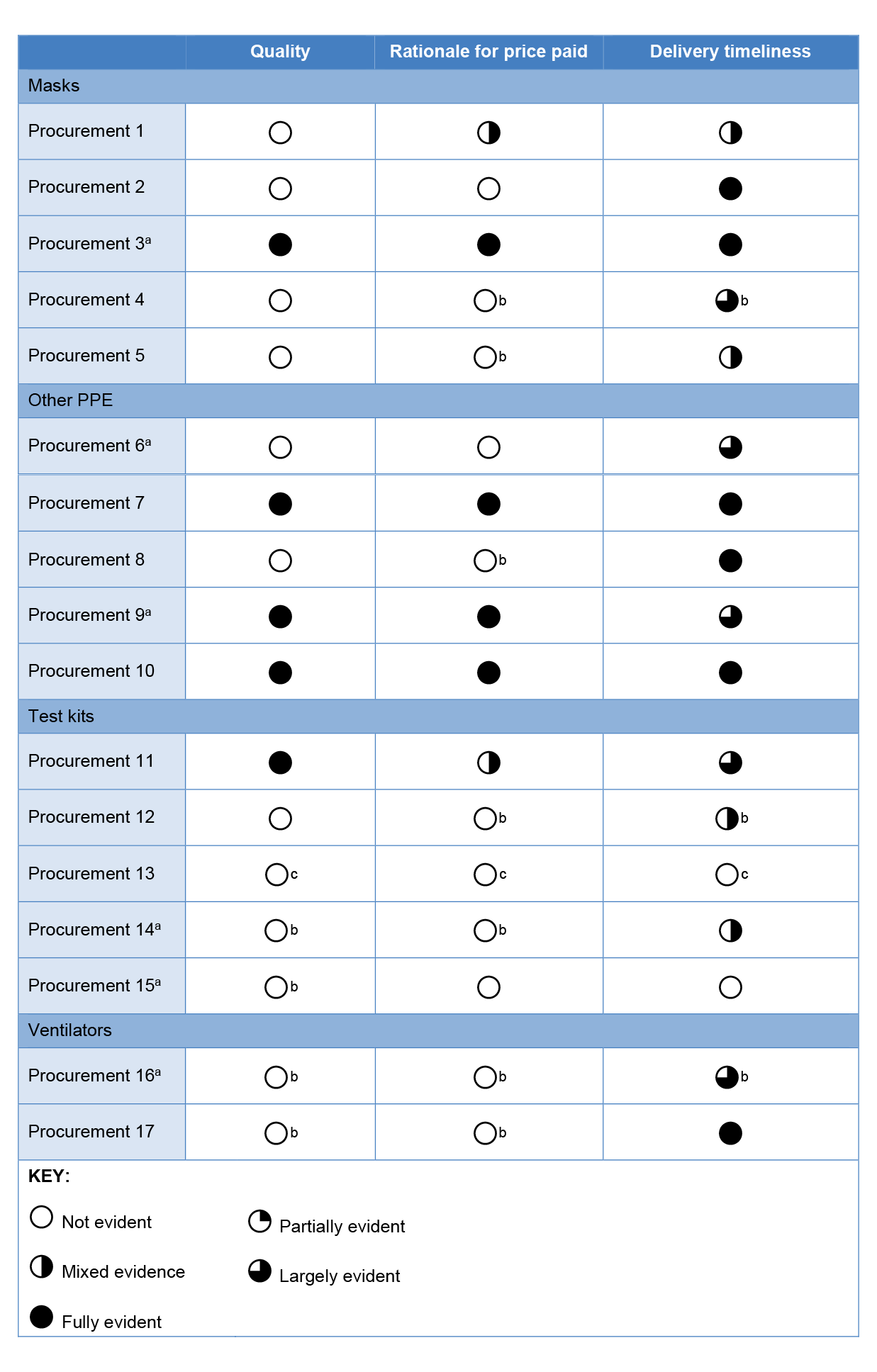

Table 2.1: Sampled procurements — Due diligence checks

Note a: This procurement was referred to Health by DISER.

Note b: The ANAO examined whether: due diligence had considered if the product needed to be on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG); advice was sought about the likelihood of the product to be approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA); or assurances were obtained that the supplier was in the process of obtaining ARTG status.

Note c: Not an established provider; the procurement was intended to create a domestic manufacturing capability.

Note d: During its assessment of the supplier, DISER documented that the product was not required to be on the ARTG.

Note e: Prior to awarding the contract, Health received confirmation that the majority of the product had already been delivered to Australia and the product had been validated by the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity.

Note f: ‘Evident’ refers to documentation of the due diligence check or, if not documented, sufficient evidence in emails, file notes or other records that the due diligence check was done.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health and DISER documentation and correspondence.

2.10 Most products procured for the NMS are regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (TGA Act) and are required to be listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). On 22 March 2020 the Acting Secretary of Health signed an emergency determination exempting Health-procured disposable face masks, gloves, gowns and protective eye wear from the requirement.11 Despite this exemption Health indicated that, as a risk mitigation strategy, it would include in contracts a requirement for goods to be on the ARTG and it examined the ARTG status of some potential products (such as whether or not the supplier was in the process of obtaining registration) at the due diligence stage. Of the 16 relevant tested procurements, Health confirmed for 13 the suppliers’ activities in relation to obtaining ARTG registration in advance of awarding the contract.

2.11 Health obtained Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) extracts — which Health advised were intended to confirm the identity of the directors, that the potential supplier legally existed and that the supplier was not subject to current external administration or other strike off (deregistration) action by ASIC — for 16 of 17 procurements. Company longevity was considered through the ASIC extract or, where not obtained, through an Australian Business Number search, for all 17 procurements. Potential integrity ‘red flags’ were not always pursued by Health at the due diligence stage of the procurements. For example, in one procurement, the ASIC extract showed that the sole company director was associated with a company in liquidation but Health did not consider this prior to awarding the contract. This contract was later dissolved due to non-delivery (refer paragraph 2.31).

2.12 Documented consideration of suppliers’ financial standing was generally minimal. For 12 of 17 tested procurements, Health’s legal services provider advised that in order to form a view on financial standing, Health would need to examine a copy of the most recent financial statements. Health obtained copies of financial statements for five of the 17 tested procurements. A review of financial statements was documented for only two procurements, although in two other procurements DISER undertook a credit check.

2.13 Suppliers with no experience or a lack of capacity may present a higher risk of failing to deliver. For the 17 tested procurements, the external legal provider advised Health on five occasions that an ASIC search did not provide information on the company’s ‘ability to deliver or experience’ and that Health ‘would need to make separate enquiries as to that’. Checks in the other PPE category were reasonably complete, but were variable in the mask and test kits categories. The experience of four providers (Procurements 1, 2, 6 and 15) was documented but not thoroughly analysed at the product level because technical ability was assumed based on the company’s general reputation. In one case (Procurement 5), no documented further assurance of technical ability was obtained beyond the supplier’s unverified claims. Due diligence activities in the ventilator category were informed by advice from the Chief Scientist and medical experts.

2.14 A framework would have assisted officers tasked with due diligence and enabled a more consistent approach across the procurements.

Commitment of public funds by the financial delegate

2.15 Section 18 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 stipulates that when a commitment of money is made, a record of the approval must be made in writing as soon as practicable and in a way that is consistent with accountable authority instructions. Health’s Accountable Authority Instructions indicate that Health officials must not approve a proposed commitment of relevant money unless they have been delegated powers to do so; approvals must be properly recorded; and approvals must be made before or at the same time as entering into the arrangements.

2.16 Health largely followed Accountable Authority Instructions. The appropriate delegate gave the approval in all instances. Suppliers assessed as passing the due diligence phase were recommended to the delegate via a commitment approval minute for 16 of 17 sampled procurements and in the seventeenth, which was for point-of-care test kits, the delegate indicated their approval of the commitment by sending a purchase order to the supplier. In one instance delegate approval for a commitment was obtained after entering into an arrangement with the supplier. In an additional three procurements, verbal approval was given after the commencement date of the contract but may have been before the date of contract execution, which was not documented.

2.17 Overall, commitment approval minutes consistently explained delivery timeframes to the delegate but did not consistently explain other key attributes such as the quality of the product or a rationale for the price paid (refer Table 2.2). Where commitment approval minutes in the test kit and ventilator categories existed they were lacking in detail, such as why the supplier was selected or how the procurement compares to other procurements in the same category. In eight of 17 procurements (indicated by note b to Table 2.2) the ANAO found evidence that officials analysed quality, price or timeliness but no evidence that this analysis was presented to the delegate approving the commitment.

Table 2.2: Sampled procurements — Evaluation in commitment approval minutes

Note a: This procurement was referred to Health by DISER.

Note b: There is evidence of analysis in other documentation (for example, email correspondence, file notes) but this detail was not provided in the commitment approval minute considered by the delegate.

Note c: There was no commitment approval minute for Procurement 13.

Source: ANAO analysis of commitment approval minutes.

Establishment and management of supplier contracts

2.18 Procurement includes the ongoing management of the contract that has been awarded. Value for money should be measured based on whole of life costs and is not fully realised until completion of the contract.12

Specification of contractual terms

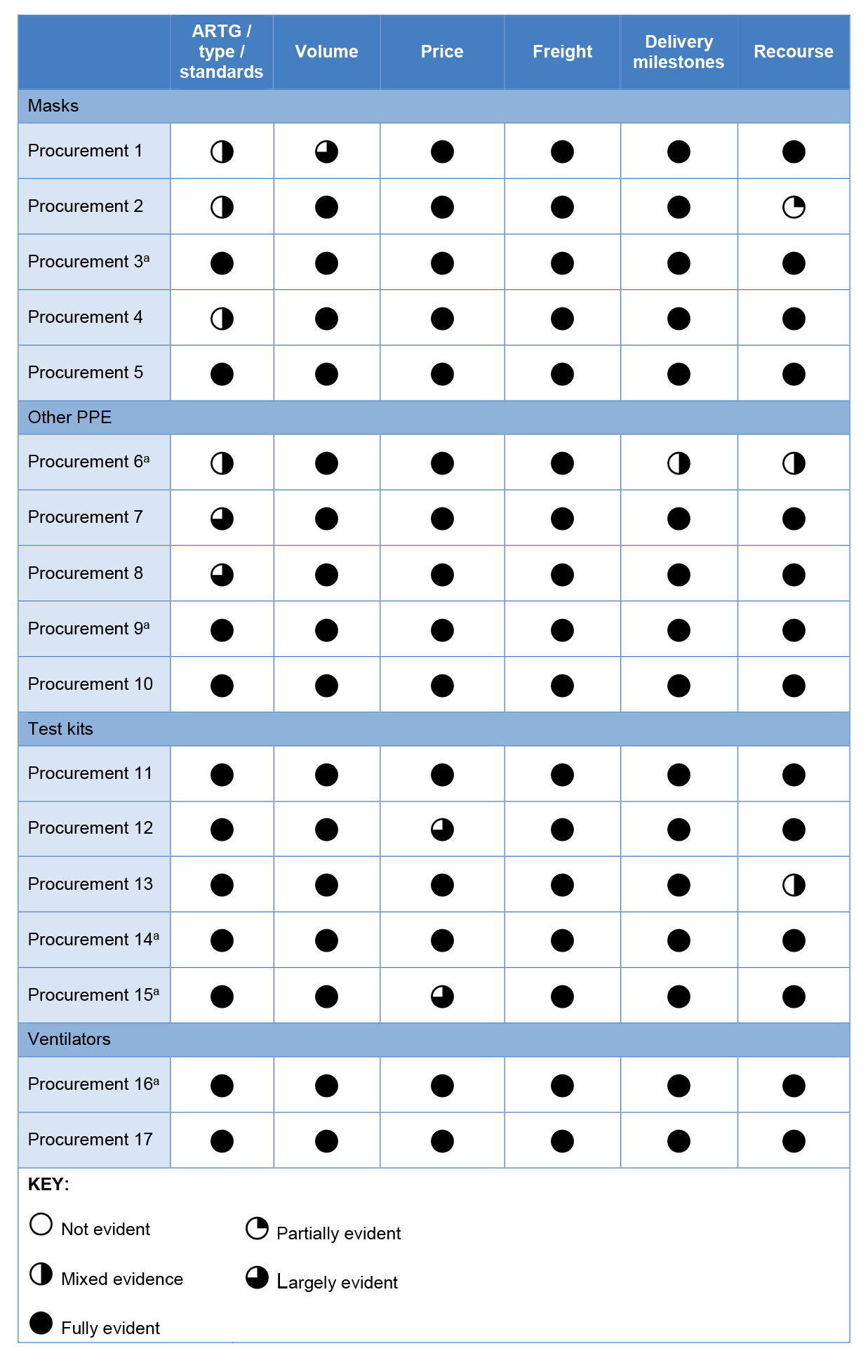

2.19 The ANAO reviewed 17 sampled contracts for the clarity of specifications on the type and standards of goods to be delivered, the volume of the product to be supplied, price, freight arrangements, delivery milestones and recourse mechanisms in the event of supplier failure to meet contractual obligations (refer Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Sampled procurements — Inclusion and clarity of contract specifications

Note a: This procurement was referred to Health by DISER.

Source: ANAO analysis of executed contracts.

2.20 Despite the TGA exemption (refer paragraph 2.10), Health included a requirement in nine of 10 tested mask and PPE contracts that the goods procured were registered on the ARTG because this provided ‘additional protection to the Commonwealth as the supplier…is subject to the obligations…under the [TGA Act] as well as specific contract provisions’. Tested contracts were generally clear, however specification of the product type, level and/or standards (where applicable) in the mask and other PPE categories and whether GST was applicable could have been clearer. Fifteen of the 17 tested contracts contained a seven or 14 day return period in which Health could reject the goods, and 14 of the 17 contracts included an additional warranty period in which the supplier must replace any defective goods at their own cost.13

Contract management

2.21 Contract management refers to all of the activities undertaken, after the contract has been signed or commenced, to manage the performance of the contract to achieve the agreed outcomes.14

Contract management planning

2.22 Health classifies procurements using a four-category risk continuum that comprises ‘routine’, ‘focussed’, ‘strategic’ and ‘complex’ classifications. Health guidance indicates that ‘focused’ procurements typically have an average contract value of less than $400,000 and are suitable where delays in delivery will cause inconvenience but will not affect organisational outcomes. Given the high value of many of the COVID-19 NMS contracts (including one contract valued at $800 million), the technical nature of the products, the high involvement of senior executive management, the reliance on overseas manufacturers and the public health consequences of non-delivery, some or all of the COVID-19 NMS procurements should have been classified as ‘complex’ or ‘strategic’. However, Health advised the ANAO that all the NMS COVID-19 contracts were classified as ‘focused’, the second classification, because the contractual arrangements were not complex, the contracts were generally short-term and the procurements related to the supply of goods within a negotiable timeframe. Health was unable to provide any documentary evidence of this classification.

2.23 Health procurement policy states that if the procurement is classified as anything above routine, contract management activities must be documented in a contract management plan. None of the tested mask or PPE procurements have a documented risk or contract management plan, however Health finalised an NMS Assurance Strategy on 9 November 2020. The Assurance Strategy contained many elements of contract management planning in the aggregate. Although the strategy is an important element of contract management planning, it was introduced late in the procurement life cycle, after suppliers delivered at least some component of their contract with Health. Around 70 per cent of 56 contracts specified a first delivery date before 30 June 2020.

2.24 The Assurance Strategy did not cover non-PPE items (COVID-19 test kits and components, and ventilators). Contract management plans were developed for three test kit contracts in December 2020, including for one contract that had been dissolved in May 2020.

Contract monitoring

2.25 Health maintained several spreadsheets to monitor contract deliverables for mask and PPE contracts, including delivery of goods by the delivery deadline specified in the contract, freight costs, ARTG status, quality certification and TGA post-market testing results.

2.26 Quality monitoring processes for mask and other PPE products procured for the NMS are outlined in the Assurance Strategy and included the following.

- Visual inspection of products and packaging — there were no specific protocols or criteria for conducting visual inspections. Health advised the ANAO that the logistics providers confirmed deliveries through stock on hand reports and performed visual inspections, which are also reported to Health through daily ‘inbound’ reports.

- Compliance documentation — on 29 May and 3 July Health asked suppliers for written information on how masks and other PPE already, or to be, supplied to the NMS meet Australian standards and recorded the results in a ‘PPE Assurance’ spreadsheet. ARTG registration status was also tracked, with 96 of 135 products described as registered as at February 2021. Results of desktop reviews of compliance documentation by the TGA as at 19 October 2020 were recorded for 49 of the products exempted from the TGA Act, with 21 described as a ‘pass’ (meaning the TGA held ‘absolute regulatory confidence’), 12 as ‘middle confidence’ and 16 as ‘fail’ (little confidence).

- Independent laboratory testing — Health sought outcomes from independent testing against Australian standards to provide assurance on suitability for use in Australia. The testing strategy was to sample goods supplied to the NMS based on prioritisation criteria due to limited domestic independent testing capacity. Samples of masks were sent for independent testing in July to October 2020.

- Post-market monitoring and compliance — at 9 November 2020, a Health minute indicates that samples from 27 of 54 manufacturers of surgical and P2 masks had been provided to the TGA by Health for post-market testing.15 Results were recorded in a ‘TGA results’ spreadsheet.

2.27 Health advised the ANAO that in the test kit and ventilator categories it relied on pre-market regulation by the TGA for quality assurance of procured items, as well as requirements under the Health Insurance Act 1973 for pathology laboratories to validate pathology tests prior to use. In addition to the pre-market regulation, as part of a broader exercise the TGA conducted a post-market assessment of two point-of-care serology tests procured for the NMS. Health advised the ANAO that ventilators need to be tested in situ and at February 2021 no ventilators had been deployed within Australia.

Contractual non-compliance

2.28 Health had a framework for dealing with contractually non-compliant items that included: notifying relevant Health officers about the non-compliance; tracking and tracing items to prevent further deployments; and recalling stock that had already been despatched. The framework permitted non-compliant goods to be used in different settings.16

2.29 Contracts contained provisions that allowed for the rejection of goods within a return period should they prove to be deficient. Health advised the ANAO that ‘the ability to undertake heightened, or in some cases traditional, goods receipting activities were impacted’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reasons included high volumes of procurements into warehouses over short periods, unavailability of Health and logistics provider staff due to COVID-19 restrictions on movement and limited domestic testing capabilities combined with an increase in testing demand. This meant that ‘potential lead times for results were often beyond contractual acceptance periods.’ However, despite the expiry of the return period, the warranty period represented an additional recourse option in most contracts (refer paragraph 2.20).

2.30 Health advised the ANAO that products are determined to be non-compliant by agreement between both parties, at times requiring the resolution of TGA regulatory processes or further independent testing. If contractual non-compliance is agreed, the options comprise replacement of non-compliant stock or refund. Should agreement not be reached, resolution would be sought under the contractual terms as required by law.

2.31 Across the 17 tested procurements, Health has managed instances of contractual non-compliance.

- One tested contract for point-of-care test kits was dissolved prior to payment due to non-delivery of the goods.

- Through independent testing completed in October 2020, Health determined that face shields delivered in full to the NMS through one procurement did not meet splash protection requirements. The supplier redesigned a product component and provided new independent test results demonstrating compliance on 1 February 2021. The supplier requested additional reimbursement for the replacement component. At May 2021 Health was continuing to discuss this proposal with the supplier.

- The TGA issued a product defect alert on 14 November 2020 for a mask procurement. Health requested the supplier’s assistance in reaching a resolution with the manufacturer, however the supplier noted that the manufacturer had ‘no legal obligation to either [Health] or [the supplier]’ under terms of the contract. The manufacturer disputed the test results and made a number of demands of Health that were rejected. At May 2021 Health was continuing to work with the TGA and the manufacturer to resolve the dispute.

- As of 16 December 2020 Health had issued seven notices of rejection, all to one supplier, with the first notice issued on 26 June 2020. At May 2021 legal advice had been sought and a resolution, including replacement of products through a deed of variation, was being negotiated.

2.32 A variation to a contract with one supplier due to non-delivery of gloves resulted in around $54,000 in pre-payments being reimbursed to the Australian Government. Health advised the ANAO that, at February 2021, no further funds expended on NMS COVID-19 PPE or medical supply procurements have been reimbursed.

2.33 While negotiations related to non-compliant products are underway, Health documentation indicates that the products are quarantined from deployment.

2.34 There is evidence of TGA post-market testing raising concerns about surgical and P2 masks that had passed earlier Health-commissioned independent testing and that had already been deployed. When this occurred, Health wrote to those to whom this product, or a product from the same manufacturer, had been deployed to advise them of the issue and offer replacements.

2.35 From 2 April 2020 Health produced daily reports of approximate stock, procurements and dispatches by product type. In October 2020 this reporting was amended to reflect the results of the quality assurance process. The bi-weekly (later weekly) reports included stock that was classified as ‘ready to deploy’ but excluded stock that was classified as ‘do not deploy’ (quarantined from deployment).17 Health advised the ANAO that a ‘do not deploy’ classification reflected a range of considerations including quality assurance, labelling, clinical advice on usage, TGA guidance and post-market testing and that:

‘Do not deploy’ may be applied to all stock until such time as the assurance matter is resolved, greater confidence can be gained about stock in the [logistics provider records] or there is a change in broader circumstance where risk of not deploying outweighs the potential risk from the assurance issue.

2.36 At October 2020, around half of mask stock on hand was classified as ‘ready to deploy’.

2.37 Health advised the ANAO that ‘do not deploy’ stock does not reflect any loss unless and until the stock is determined to be not fit for purpose and is returned to the supplier. At March 2021, 76 million surgical masks (13 per cent of all procured surgical masks), 39 million P2 masks (23 per cent) and 500,000 pairs of gloves (one per cent) had been determined not fit for purpose, with either contract resolution being pursued or, in rare cases, stock being returned to the supplier (refer Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Procurement outcomes, at 24 March 2021a

Note a: PPE classified as not fit for purpose is as advised to the ANAO by Health at 24 March 2021. The ANAO did not verify the accuracy of this data.

Source: ANAO analysis of contractual commitments and Health advice.

Were procurement processes ethical, efficient and economical?

Ethical procurement processes were established, although interest declarations were late and incomplete. DISER approached the market in a manner that promoted equitable treatment. While the criteria for triaging offers could have been more transparent in both departments, the contracts awarded by Health were drawn from a range of sources. Efficiency was impacted by the dynamic situation. Procurement processes did not emphasise an economical outcome, but the average unit price paid was aligned with prevailing market prices where these were known.

2.38 The audit team examined whether procurement processes for the COVID-19 NMS procurements were consistent with the proper use and management of public resources through the application of ethical, efficient and economical processes.

Ethical procurement processes

2.39 Ethical procurement practices can be demonstrated through the establishment and application of probity measures and the equitable identification of potential suppliers.18

Probity

2.40 Entities should identify any circumstances that involve elevated risk of conflicts of interest and require that declarations be made before the person begins the work.

2.41 Health’s conflicts of interest policy:

- requires that staff declare any conflicts of interest upon engagement with the department and when there has been a change in employee circumstances or work responsibilities, recognising that conflict of interest needs to be an ongoing consideration for employees;

- requires that senior executive service (SES) employees must complete an annual declaration of interests, which does not exclude the officer from the requirement to make a new declaration if there is any change in their work circumstances or if required through specific business processes;

- notes that separate conflict of interest declarations may be required by specific business processes such as procurement;

- states that procurement is considered an area of high risk for conflict of interest; and

- states that additional requirements may be applied for groups of employees undertaking particular higher risk functions and that officers are required to comply with this.

2.42 DISER’s policy requires staff to undertake awareness training on conflicts of interest upon engagement and annually. Non-SES officers are required to complete a conflict of declaration form only if they have a conflict, but SES officers are required to complete a declaration of interests form annually or if there is a change of work responsibilities, regardless of whether they have a conflict to disclose.

2.43 On 25 March and 15 April 2020 DISER directed staff who had been or were involved in any of the procurement activities related to the COVID-19 response taskforces to complete a declaration of interests by 18 April 2020, which required staff to indicate that they did not have a conflict of interest or to declare a conflict if one existed. Several times in May 2020 Health directed staff working in the National Stockpile and Finance Branch in any capacity to have up to date declarations of personal interest. These directions were late in the procurement process.

2.44 For the 17 sampled procurements, the ANAO compiled a list of key personnel with a substantive role in the procurements and determined whether a declaration of interests had been made as directed by both departments. Of 17 key Health personnel who received the direction, 13 filed the declaration of interests. Nine of 11 key Health personnel who did not get the direction but were substantively involved in the procurements completed a form of declaration. One senior key Health official did not file a declaration with Health until October 2020, but provided Health with a copy of a declaration submitted to a different department in November 2019. Of 22 key DISER personnel, 14 completed a declaration. Two senior officials did not complete the declarations relating specifically to the procurements, although they had filed an annual declaration.

2.45 At Health, all declarations were filed after 30 April 2020, after most of the procurements had been awarded. At DISER, the majority of declarations were filed in April and May 2020 after around 40 per cent of referrals had been sent to Health.

2.46 One Health official identified a conflict and this was managed appropriately in accordance with departmental policy through a written plan that restricted the official’s dealings with a specific supplier. At DISER, two officers declared a potential conflict of interest which were managed appropriately in line with departmental policy through assessment by a senior manager. Both conflicts were determined to be immaterial.

2.47 The separation of duties in procurement is an internal control in avoiding conflicts of interest and maintaining fairness and transparency in the procurement process. Department of Finance (Finance) guidance states that officials involved in the evaluation of tenders should not be those who are approving the proposal to spend public money.19 Health did not have a documented policy regarding separation of duties in procurement. In at least three of the COVID-19 NMS procurements, the Health delegate approving the expenditure also had a material role in the identification, due diligence or assessment of the supplier.

2.48 Finance guidance advises that an external probity specialist may need to be appointed where the procurement is high value, complex or unusual; the integrity of the procurement may be questioned; or a prequalified or limited tender process is proposed. Health’s probity principles state that an independent advisor should be appointed for complex, high risk or sensitive procurements. In early April 2020 Health engaged an organisation to provide ‘in flight assurance assistance’. The organisation finalised a review on the procurement and contracting of test kits from one supplier in July 2020. Appointing a probity advisor at the outset of the activities could have provided further assurance given the risk environment of the procurements.

Equity

2.49 Ethics in procurement includes ensuring that suppliers should not be excluded from consideration for inconsequential reasons.20 Procurement activities — including decision-making as to whether to approach the market, supplier identification and negotiation — began in January 2020. Until paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs was invoked on 18 March 2020, the procurement activities should have been aligned, at a minimum, with Division 1 of the CPRs, which require officials responsible for procurement to be satisfied that the procurement will achieve a value for money outcome through the encouragement of competition and non-discrimination.

2.50 Approaching the market and communicating about the procurements through AusTender are mechanisms for promoting equitable treatment. These enable potential suppliers to learn about the procurement opportunity in a manner that is consistent across suppliers and the procuring entity to learn about the range of potential suppliers. DISER approached the market via AusTender on four occasions comprising:

- a Request for Information (RFI) on domestic production capabilities relevant to a range of medical PPE (15 March) ;

- a request for Expression of Interest for the supply of swabs suitable for COVID-19 sample collection (20 March); and

- two RFIs for Australian production capability for components of COVID-19 test kits (3 and 9 April).

2.51 Health and DISER received up to 4076 offers of assistance to provide PPE and other medical supplies to the NMS from various sources.21 Initially, triage of the offers was conducted by the NMS operations section in Health and separate product category taskforces within DISER. In late March both departments established taskforces to triage offers.

2.52 Health advised the ANAO that there was a backlog of offers at the time the COVID Proposals Triage Team was established on 26 March 2020, which was resolved by June 2020. DISER taskforce closure documentation dated 8 July 2020 indicates that all PPE RFI submissions had been responded to by that time.

2.53 Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Health’s COVID Proposals Triage Team were created in mid April 2020. The SOPs indicate that PPE offers needed to be ‘bona fide’ in order to be progressed but provided no guidance on what this meant. Health advised the ANAO that the two primary criteria for further consideration of an offer were whether the offer looked legitimate and whether it was for an item that was needed according to the procurement priorities at the time.

2.54 DISER developed SOPs for dealing with PPE RFI responses and other offers and referrals. The guidance did not include the criteria to use in assessing offers of assistance, which DISER advised the ANAO was left to the judgement of individual officers who prioritised pace, quantity and quality within the context of Health’s direction to procure ‘as much as possible, as quickly as possible’. Closure documentation produced by DISER’s Triage and Coordination Taskforce indicates that PPE or medical equipment offers were checked to determine if they included relevant information regarding product type, quantity, location and relevant certifications and where they ‘met the necessary thresholds’, were providing ‘desired’ goods and were ‘promising’.

2.55 Documentation of clearly defined initial assessment criteria could have improved triage transparency in both departments.

2.56 As at February 2021, 53 contracts for PPE and medical supplies were awarded with a total value of $2.83 billion (refer Appendix 2).22 The procurements drew from a variety of sources, including direct approaches to Health or DISER, referrals from other Australian Government entities, Ministers’ offices and the AusTender approaches to market.

Efficient procurement processes

2.57 In the emergency circumstances of the COVID-19 NMS procurements, an efficient use of resources was important.23 At the peak of procurement activity, 35 full time equivalent staff were working on the procurements at Health and at DISER 173 full time equivalent staff were diverted to the taskforces supporting Health.

2.58 DISER’s role in the procurements included: identifying areas of supply chain vulnerabilities; sourcing, triaging and assessing offers to supply PPE and other medical supplies to the NMS; conducting due diligence on some offers of assistance; and drafting some contracts, which it then referred to Health. In total, DISER referred 61 contracts to Health (refer Table 2.4).

Table 2.4: DISER contract referrals and outcomes, at 31 December 2020

|

|

Masks |

Other PPE |

Test kits |

Ventilators |

Total |

|

Contracts referred to Healtha |

9 |

41 |

10 |

1 |

61 |

|

Referral outcomes |

|||||

|

Contracts executed by Health |

3 |

11 |

8b |

1 |

23 |

|

Per cent of referred contracts executed |

33% |

27% |

80% |

100% |

38% |

|

Contracts not executed by Health |

6 |

30 |

2 |

0 |

38 |

|

Reasons for non-execution by Health |

|||||

|

Product type was no longer needed |

3 |

11 |

0 |

n/a |

14 |

|

Due diligence raised concernsc |

1 |

4 |

2 |

n/a |

7 |

|

Specific product did not meet needs |

0 |

2 |

0 |

n/a |

2 |

|

Price increase / offer expired |

0 |

2 |

0 |

n/a |

2 |

|

Contract terms unfavourable |

0 |

1 |

0 |

n/a |

1 |

|

No documented reasond |

2 |

10 |

0 |

n/a |

12 |

|

Average value of referred contracts (millions)e |

$ 37.6 |

$ 21.2 |

$ 4.7 |

$75.2 |

$21.8 |

Note a: Where multiple contracts were referred by DISER for the same supplier and item, the analysis is based on the first referred contract.

Note b: One of the test kit (swabs) contracts referred by DISER and executed by Health was later dissolved.

Note c: This includes Health identifying a concern in DISER’s due diligence outcomes and Health deciding to conduct additional due diligence activities.

Note d: All of these contracts were referred by DISER to Health after 3 April 2020.

Note e: Amounts are in Australian dollars (AUD) excluding GST. The ANAO converted amounts in United States dollars to Australian dollars using the rate of exchange on the day of contract referral. Many contracts did not include freight costs at the time of referral.

Source: ANAO analysis of PPE and medical equipment contracts referred by DISER to Health.

2.59 Between 6 and 8 April 2020, Health adjusted the priority of products for procurement and determined that a number of product types in the other PPE category were no longer required (spill kits, thermometers, mask fit test kits and face shields). The decision to stop procuring spill kits was communicated to DISER on 6 April. By that time DISER had prepared and referred five contracts for spill kits. One referred contract was ultimately awarded. DISER referred a surgical mask contract to Health on 9 April 2020, the same day that Health formally advised DISER that surgical masks were no longer required. Although Health advised the ANAO that there was ‘constant communication on priorities and suppliers between Health and DISER’ the ANAO was unable to locate any earlier communication about these specific issues between the departments. Health and DISER have noted that these inefficiencies reflected the dynamic nature of the procurement environment at the time.

2.60 Lack of clarity on contract templates led to some inefficiencies across the departments. Although Health began using a bespoke contract template on 10 March as the preferred approach for contracts valued at greater than $200,000, Health did not request that DISER use this template until 26 March. Between 10 and 26 March DISER referred 13 contracts using the previous template; Health redrafted four using the bespoke template.

2.61 In taskforce closure documentation DISER identified several lessons learnt that could improve efficiency and benefit other Australian Government agencies facing similar challenges. These included: a modified online facility to receive responses to approaches to market; a contract tracking facility that could accommodate multiple simultaneous editors; improved inter-departmental communications on procurement outcomes; single points of contact between the departments and clearer communications protocols; a short daily meeting among directors, a communication board and a daily status email to improve communication and reduce duplication between taskforces; and improved clarity on contract drafting requirements.

Economical procurement processes24

2.62 As part of its closure reporting, the Health Industry Coordination Group (HICG) noted that the COVID-19 NMS procurements were conducted in a highly competitive environment of price volatility and variability for PPE and medical equipment.25 The HICG attributed the volatility to high international demand, trade restrictions, freight costs, unconscionable conduct on the part of some suppliers and lack of coordination among Australian procurers, among other factors.

2.63 Health advised the ANAO that ‘discussions on appropriate pricing for PPE and medical supplies took place throughout the procurements…’ and that although a ventilator price target was difficult to establish given varying features and technology, ventilator pricing decisions were informed by advice from clinical experts, DISER and the Chief Scientist.

2.64 Price was considered during triage at DISER. DISER advised the ANAO that the Expression of Interest and RFI processes provided information about prevailing prices which was used to guide ongoing decision making and advice to Health and that any ‘uncompetitive’ quotes were not progressed. There is evidence for some products (masks, goggles) of Health rejecting offers on the basis of price. Among the 17 tested procurements, four involved Health negotiating price.

2.65 The range of prevailing market prices was documented for some products (refer Table 2.5), although this was sometimes done too late to have informed procurement decisions. The average unit price paid was lower than or within the range of market prices, where this was known by Health or DISER. Some maximum prices reflected higher level specifications procured or earlier procurements.

Table 2.5: Prices paid compared to price rangesa

|

Product |

Prevailing unit prices |

Target unit price |

Minimum unit price |

Maximum unit price |

Average unit price |

Average compared to prevailing |

|

Surgical masks |

$0.80–$1.20 |

$2.50 |

$0.62 |

$2.59 |

$1.12 |

In range |

|

P2 masks |

$4.00–$6.50 |

$3.00 |

$0.65 |

$20.40 |

$6.28 |

In range |

|

Isolation gowns |

$4.00–$10.00 |

Unspecified |

$4.00 |

$9.69 |

$5.96 |

In range |

|

Surgical gowns |

$10.00–$14.80 |

Unspecified |

$9.80 |

$15.21 |

$12.85 |

In range |

|

Gloves (pair) |

$0.50–$1.67 |

Unspecified |

$0.17 |

$1.50 |

$0.20 |

Lower |

|

Medical coveralls |

$40.00–$54.00 |

Unspecified |

$28.10 |

$35.83 |

$31.58 |

Lower |

|

Face shields |

$4.00–$6.00 |

Unspecified |

$1.76 |

$9.85 |

$4.76 |

In range |

|

Goggles |

$7.00 |

Unspecified |

$3.93 |

$10.82 |

$5.93 |

Lower |

|

Invasive ventilators |

$25,000–$65,000 |

Unspecified |

$15,650 |

$53,950 |

$23,923 |

Lower |

|

Non-invasive ventilators |

Unspecified |

Unspecified |

$7300 |

$7300 |

$7300 |

n/a |

|

Point-of-care tests |

Unspecified |

Unspecified |

$13.90 |

$19.85 |

$17.25 |

n/a |

|

RT-PCR testsb |

$24.00 |

Unspecified |

$17.89 |

$21.55 |

$20.66 |

Lower |

|

Swabs |

$1.00–$4.00 |

Unspecified |

$2.24 |

$4.76 |

$4.00 |

In range |

Note a: All prices are excluding GST. Unit prices were obtained from commitment approval minutes. The ANAO converted prices in United States dollars to Australian dollars using the rate of exchange on the day of execution. Averages are the weighted averages taking into account the volume of items procured. The table does not differentiate between products with different specifications, for example: surgical masks which may be classified at level 1, 2 or 3; face shields which may be single use or reusable; and swabs which may be supplied with or without viral transport medium.

Note b: The unit price shown for COVID-19 tests is per test rather than per test kit.

Source: Analysis of Health commitment approval minutes and other Health documentation.

Was procurement record keeping and reporting fit for purpose?

Record keeping for the procurements was partially fit for purpose, which impeded review and transparency. Public reporting of the procurements complied with requirements.

2.66 Maintaining appropriate records provides evidence that an entity’s procurement processes were appropriate.26 In a COVID-19 Procurement Policy Note issued by Finance, Commonwealth officials engaged in procurements during the pandemic were reminded that ‘they should ensure appropriate records are kept commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement, having regard to the current COVID-19 environment’.27 The ANAO examined whether appropriate records were maintained and contract reporting was compliant with requirements.

Records maintenance

Due diligence and evaluation outcomes

2.67 Health did not systematically maintain records in relation to short-listing, due diligence and evaluation. A Procurement and Contract Management Checklist sent to officials on 21 May was filed for 13 of the 17 sampled procurements. The checklist was inconsistently completed and did not require officials to indicate by whom and when key decisions were made, provide a rationale for those decisions or attach supporting evidence for claims about value for money and risk.

2.68 A Health review into NMS finance processes in July 2020 found that, for 22 tested contracts, value for money considerations were ‘generally’ not clearly documented within the commitment approval documentation and that the documentation of risks and mitigation measures in minutes was ‘highly variable and, in some cases, limited.’ The ANAO found that in a sample of 54 commitment approval minutes, risk was explicitly mentioned in 48 minutes, but only 16 of the 48 minutes provided a justification for the risk rating.

2.69 A DISER internal audit found that there were varying levels of documentation to support the recommendations that were made to Health and there were instances where a recommendation was made without key decision-makers sighting the reasons. This made it difficult for internal auditors to determine how value for money was assessed. The audit recommended developing a better practice governance template to ensure basic processes were in place from the start.

2.70 Internal DISER taskforce closure documentation identified several areas in which record keeping could have been improved, including document naming conventions; a consistent filing approach for emails and quotes; a centralised, designated filing location; and earlier establishment of a central email from which to coordinate the drafting of contracts.

2.71 For the 17 tested procurements, key due diligence and assessment documents at Health and DISER were difficult to locate. The departments advised the ANAO that the rapid pace of decision-making and procurement of a large volume of PPE that was in high demand globally meant that many decisions were made during meetings, emails and telephone calls that were not always minuted or filed. Limited records were found in Health’s information management system relating to due diligence and the use of imprecise filing structures and inconsistent and ambiguous document naming meant that documents were not easily identifiable.

2.72 DISER undertook record keeping activities following protocols established through DISER taskforce closure activities in May and the internal audit recommendation.28 Health advised the ANAO that in addition to its ongoing activities to improve records, it would undertake ‘retrospective record keeping’ at the conclusion of ‘active contract management…to ensure increased accessibility for all records’. The ANAO has made findings with respect to record keeping in a number of previous performance audits of Health.29

Recommendation no.1

2.73 As a component of the protocols for emergency procurements recommended and agreed to in Auditor-General Report No.22 2020–21, Health include protocols for record keeping that would facilitate reasonable assurance that public resources are being used properly during an emergency procurement.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

2.74 In line with Health’s response to Recommendation 4 of Auditor-General Report No. 22 2020–21, Health agrees it would be appropriate to put in place expanded documentation to record information in relation to emergency procurements.

Delegate approvals of financial commitments

2.75 Commitment approval minutes were signed for 51 of 53 COVID-19 NMS procurements (refer Table 2.6).30 For two point-of-care COVID-19 test kit procurements there was no documented advice to the financial delegate but approval was indicated through emails sent by the delegate directly to the suppliers. In eight of 17 tested procurements, the minute was approved retrospectively, referring to previously provided verbal approval.

Table 2.6: Commitment approval minutes, to February 2021

|

|

Number |

Average valuea |

Maximum value |

|

Total procurements to February 2021 |

53 |

$53 million |

$800 million |

|

Procurements with a commitment approval on file |

51 |

$55 million |

$800 million |

|

Procurements with no commitment approval on file |

2 |

$9 million |

$10 million |

|

Commitment approvals through a formal minute |

45 |

$60 million |

$800 million |

|

Commitment approvals provided via email |

6 |

$20 million |

$72 million |

|

Indicating CPRs did not apply under paragraph 2.6 |

46 |

$60 million |

$800 million |

|

Indicating exempted from Division 2 under paragraph 10.3 |

3 |

$10 million |

$25 million |

|

No advice regarding CPRs provided |

4b |

$5 million |

$10 million |

Note a: All amounts are excluding GST. Excludes contract dissolutions as at February 2021.

Note b: Includes two procurements with no signed commitment approval minute on file.

Source: ANAO analysis of commitment approval minutes.

2.76 Finance advised Health to maintain clear documentation for the CPR ‘exemption’ (refer paragraph 1.9). Minutes record the invocation and revocation on 18 March and 9 July 2020, respectively.31

2.77 When seeking approval to commit funds, the delegate should be informed about whether the procurements complied with the CPRs. For 48 of the procurements, the advice to the delegate was that the CPRs did not apply under paragraph 2.6. Two contracts approved under these conditions commenced before 18 March 2020.

2.78 Three procurements were exempted from the competitive procurement processes under paragraph 10.3 of the CPRs.32 Procurements exempted under paragraph 10.3 must comply with additional reporting requirements outlined in paragraph 10.5 of the CPRs, namely a written report that includes the circumstances that justified the use of limited tender and how the procurement represented value for money. Health did not prepare a separate report for the three procurements, but advised the ANAO that this reporting obligation was achieved through commitment approval minutes. One of the three commitment approval minutes satisfied the requirements but two minutes lacked detail about value for money.

Contractual arrangements

2.79 Fifty four of 56 procurements had a written contract, purchase order or memorandum of understanding for the supply of goods. Two thermometer procurements in February 2020 were made without a formal contract or purchase order after verbal approval of the expenditure from the Minister for Health. Health advised the ANAO that these were urgent procurements of thermometers to support the screening of inbound travellers to Australia.

Contract reporting

2.80 The CPRs and Health’s Accountable Authority Instructions state that relevant entities must, within 42 days, report a new contract or amendment on AusTender if valued at or above the reporting threshold. Finance guidance indicates that contract details do not generally need to be reported on AusTender when an accountable authority applies paragraph 2.6 of the CPRs.33

2.81 Health advised the ANAO that prior to the pandemic, NMS contracts were not usually disclosed by Health on AusTender ‘due to the sensitive nature of the National Medical Stockpile’. However, on 3 June 2020 Health determined that COVID-19 NMS procurements would be reported in order to be ‘as transparent and open as possible’. Of 53 contracts for NMS medical supplies awarded to 30 August 2020, all were reported on AusTender by 30 September 2020, within 63 days on average.34

2.82 Section 2(b) of Senate Order 13: Entity Contracts requires ministers to provide a letter of advice that a list of contracts entered into by the entities they administer has been reported on the Internet. In accordance with Senate Order 13, Health placed a link on its website to the report on AusTender.35 The report contained all 38 NMS COVID-19 contracts that were valued above $100,000, as required, and awarded before 30 June 2020 (using the AusTender listed start date).

3. COVID-19 deployments

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Health’s (Health’s) deployments of the National Medical Stockpile (NMS) during the COVID-19 pandemic were effective.

Conclusion