Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Referrals, Assessments and Approvals of Controlled Actions under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The EPBC Act requires all actions that may significantly impact matters of national environmental significance (‘controlled actions’) to be referred to the Minister for assessment and approval.

- Effective administration of referrals, assessments and approvals reduces impacts on the environment while facilitating economic development.

Key facts

- Nine matters of national environmental significance are established in the EPBC Act.

- 6253 actions have been referred for assessment and approval since the commencement of the EPBC Act, with 1846 determined to be controlled actions.

- The EPBC Act requires referral, assessment and approval decisions to be made within specified timeframes.

What did we find?

- The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment’s (the department’s) administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the EPBC Act is not effective.

- The department’s regulatory approach is not proportionate to environmental risk.

- The administration of referrals and assessments is not effective or efficient.

- Conditions of approval are not assessed with rigour, are non-compliant with procedural guidance and contain clerical or administrative errors.

- The department is not well positioned to measure its contribution to the objectives of the EPBC Act.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made 8 recommendations to the department.

- The department agreed to all 8 recommendations.

116 days

Average overrun of statutory timeframes for approval decisions in 2018–19.

1034

Controlled actions approved with conditions since the commencement of the EPBC Act.

79%

Approvals assessed as containing conditions that were non-compliant with procedural guidance or contained clerical or administrative errors.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) is Australia’s primary national environmental legislation. It provides for the protection of the environment, in particular those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance. The EPBC Act defines nine matters of national environmental significance, which are:

- world heritage properties;

- national heritage places;

- wetlands of international importance;

- listed threatened species and ecological communities;

- listed migratory species;

- protection of the environment from nuclear actions;

- Commonwealth marine areas;

- the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park; and

- protection of water resources from coal seam gas development and large coal mining development.

2. Under the EPBC Act, all actions which may have a significant impact on matters of national environmental significance (defined as ‘controlled actions’) must receive prior approval from the Minister for the Environment (the Minister). This approval is received through an environmental assessment process, administered by the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (the department). The process is comprised of the following three stages.

- Referral — the action is referred to the Minister to determine whether it is a controlled action and requires approval.

- Assessment — the Minister determines the method of assessing the potential impacts of the controlled action, and the assessment is carried out.

- Approval — the Minister decides whether to approve the action and any conditions to attach to an approval.

3. From the commencement of the EPBC Act to 30 June 2019, 6253 proposed actions have been referred to the Minister, with 5088 of those actions approved and 21 actions not approved.1 Referred actions include small-scale agricultural grazing, residential and tourism developments, and the construction of large mining developments worth over $1 billion.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Effective administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the EPBC Act reduces impacts on the environment and facilitates economic development. Previous ANAO audits have identified shortcomings in the department’s administration of regulation under the EPBC Act in relation to the timeliness, consistency and effectiveness of regulatory actions.

5. The audit topic was listed in the ANAO Annual Audit Work Program in 2018–19 and 2019–20. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit identified the topic as an audit priority of the Parliament for 2019–20. The department requested that the ANAO commence the audit in July 2019 to inform the second statutory review of the EPBC Act, currently underway. The audit will provide an independent and up-to-date perspective on the department’s administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions and complement the statutory review of the Act.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment’s administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following three high-level audit criteria.

- Are governance arrangements sound?

- Is the administration of referrals and assessments effective and efficient?

- Are conditions of approval appropriate and assessed with rigour?

Conclusion

8. Despite being subject to multiple reviews, audits and parliamentary inquiries since the commencement of the Act, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment’s administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the EPBC Act is not effective.

9. Governance arrangements to support the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions are not sound. The department has not established a risk-based approach to its regulation, implemented effective oversight arrangements, or established appropriate performance measures.

10. Referrals and assessments are not administered effectively or efficiently. Regulation is not supported by appropriate systems and processes, including an appropriate quality assurance framework. The department has not implemented arrangements to measure or improve its efficiency.

11. The department is unable to demonstrate that conditions of approval are appropriate. The implementation of conditions is not assessed with rigour. The absence of effective monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements limit the department’s ability to measure its contribution to the objectives of the EPBC Act.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

12. Arrangements for collecting and managing information on compliance with the EPBC Act are not appropriate. The department does not have an appropriate strategy to manage its compliance intelligence, limiting its access to the regulatory information necessary for complete and accurate compliance risk assessments. Key limitations include poor linkages between sources of regulatory information and a lack of formal relationships to receive external information.

13. The regulatory approach to referrals, assessments and approvals has not been informed by an assessment of compliance risk. Strategic compliance risk assessments do not inform regulatory plans. In one instance, the department’s activities to promote voluntary compliance were aligned with an identified risk of inadvertent non-compliance in the New South Wales agriculture sector. The approach to individual referrals, assessments and approvals is not tailored to compliance risk.

14. While the department has established sound oversight structures, they have not been effectively implemented. Procedures for oversight of referrals, assessments and approvals by governance committees are not consistently implemented. Conflicts of interest are not managed.

15. The department has not established appropriate performance measures relating to the effectiveness or efficiency of its administration of referrals, assessments and approvals. All relevant performance measures in the department’s corporate plan were removed in 2019–20, and no internal performance measures relating to effectiveness or efficiency have been established. The department’s reporting under the regulator performance framework in 2017–18 was largely reliable.

Referrals and assessments

16. Systems and processes for referrals and assessments do not fully support the achievement of requirements under the EPBC Act. Procedural guidance does not fully represent the requirements of the EPBC Act and lacks appropriate arrangements for review and update. Information systems do not meet business needs and contain inaccurate data. Staff training is not supported by arrangements to ensure completion of mandatory requirements. There is no framework to prioritise work.

17. Referrals and assessments are not undertaken in full accordance with procedural guidance. Decisions have been overturned in court due to non-compliance with the EPBC Act and key documentation for decisions is not consistently stored on file. There is no quality assurance framework to assure the department that procedural guidance is implemented.

18. Proxy efficiency indicators developed by the ANAO indicate the efficiency of referrals and assessments has not improved over recent years. The department has no arrangements to measure its efficiency and the implementation of proposed efficiency improvement measures has not been appropriately tracked. Most referral, assessment method and approval decisions are not made within statutory timeframes.

Conditions of approval

19. Departmental documentation does not demonstrate that conditions of approval are aligned with risk to the environment. Of the approvals examined, 79 per cent contained conditions that were non-compliant with procedural guidance or contained clerical or administrative errors, reducing the department’s ability to monitor the condition or achieve the intended environmental outcome.

20. The department has not established appropriate arrangements to monitor the implementation of pre-commencement conditions of approval. The department’s systems for monitoring commencement of actions are inaccurate. The absence of procedural guidance for reviewing documents submitted as part of pre-commencement conditions leaves the department poorly positioned to prevent adverse environmental outcomes.

21. Appropriate monitoring, evaluation and reporting arrangements have not been established. Performance measurement and evaluation activities do not assess the contribution of referrals, assessments and approvals to the objectives of the EPBC Act.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.18

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment develop and implement a plan to collect and use regulatory information, and address gaps and limitations in information management, to better enable compliance information to be used to inform regulatory strategy and decision-making.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.27

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment conduct an up-to-date risk assessment of non-compliance across its environmental regulatory regimes and develop and implement arrangements to prioritise its strategic compliance assessments.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 2.62

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment ensure that its oversight of referrals, assessments and approvals is conducted in accordance with procedures, and conflict-of-interest risks are identified and treated.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 2.78

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment establish internal and external performance measures on the effectiveness and efficiency of its regulation of referrals, assessments and approvals.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 3.59

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment establish and implement a quality assurance framework to assure itself that its procedural guidance is implemented consistently and that the quality of decision-making is appropriate.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 3.83

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment establish efficiency indicators to assist in meeting legislative timeframes for referrals, assessments and approvals.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.7

Paragraph 4.18

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment improve its quality controls to ensure conditions of approval are enforceable, appropriate for monitoring, compliant with internal procedures and aligned with risk to the environment.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.8

Paragraph 4.53

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment develop guidance and quality controls to assure itself that pre-commencement conditions of approval are implemented and assessed consistently to protect matters of national environmental significance.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (the Department) agrees to implement all recommendations in the report and is committed to the continuous improvement of its processes and procedures. It will establish (where required) and strengthen (where already in place) sound governance arrangements to ensure successful implementation of improvements. This will support the efficient and effective administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

In fully implementing all recommendations, the Department will prioritise its resources to ensure that its response is flexible to any changes to the regulatory system as a result of the EPBC Act Review. Where improvements can be made in the short to medium term, the Department is committed to doing so in a timely manner. Where there is the potential for future systemic changes, the Department will design frameworks that are flexible to adapt to a new regulatory environment over the longer term.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Program implementation

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The ability of Australian governments to effectively conserve the environment while facilitating economic development requires well-coordinated and risk-targeted regulatory activities. Intergovernmental agreements developed in the 1990s2 provide a framework for cooperation and integration of Commonwealth, state and territory environmental regulation.3

1.2 The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) was designed to establish a new legislative framework for environmental regulation consistent with the intergovernmental agreements. The EPBC Act, which commenced in July 2000, replaced five previous Commonwealth Acts: the Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974, the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992, the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975, the Whale Protection Act 1980 and the World Heritage Properties Conservation Act 1983.

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

1.3 The first objective of the EPBC Act, administered by the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (the department), is to provide for the protection of the environment, particularly those aspects that are matters of national environmental significance. The Act defines nine matters of national environmental significance, which are:

- world heritage properties;

- national heritage places (added in 2003);

- wetlands of international importance (listed under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance);

- EPBC-listed threatened species and ecological communities;

- migratory species listed in international agreements4;

- protection of the environment from nuclear actions (such as uranium mines);

- Commonwealth marine areas;

- the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (added in 2009); and

- protection of water resources from coal seam gas development and large coal mining development (added in 2013).

1.4 To achieve this objective, the EPBC Act provides for ‘an efficient and timely Commonwealth environmental assessment and approval process that will ensure activities that are likely to have significant impacts on the environment are properly assessed’.5 Under this process, any person or entity (regulated entity) proposing to take an action6 that may significantly impact matters of national environmental significance (defined as ‘controlled actions’) must receive approval from the Minister for the Environment (the Minister).

1.5 Under the EPBC Act it is the regulated entity’s responsibility to determine if their action may be a controlled action. This includes determining whether the action is likely to have an impact on a matter of national environmental significance, whether the impact of the action will be significant, and whether the action is exempt from approval requirements.

1.6 Where an action may be a controlled action, it is required to be referred to the Minister (via the department) to undergo an environmental assessment process. The process is comprised of the following three stages, with the Minister (or a departmental official who has been delegated the responsibility under the Act)7 making a decision at each stage.

- Referral — the action is referred to the Minister to determine whether it is a controlled action and requires approval. The Minister may decide that the action is a controlled action, not a controlled action or is clearly unacceptable.

- Assessment — where actions are determined to be a controlled action and require approval, the Minister determines the method of assessing the potential impacts of the action, and the assessment is carried out.

- Approval — the Minister decides whether to approve the controlled action and decides on any conditions to attach to an approval, including any conditions that are to be met prior to the commencement of actions.

1.7 Bilateral agreements established with each state or territory accredit state or territory assessment processes under the EPBC Act. Where actions are covered by a bilateral agreement, the state or territory conducts the assessment and provides a report to the Minister, who then determines whether to approve the action.

1.8 The department is responsible for enforcing compliance with conditions attached to approvals and with the requirement not to undertake controlled actions without approval by the Minister. The department is also responsible for approving any documents required to be submitted before the action may commence, as part of the conditions of approval.

1.9 In the 19 years from the commencement of the EPBC Act to 30 June 2019, 6253 proposed actions were referred to the Minister. These included small-scale agricultural grazing activities, residential developments and large mining developments with expected investments of over $1 billion. Of these actions, 5088 have been approved8, with 21 actions rejected (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Outcomes for all referrals received under the EPBC Act to 30 June 2019

Note a: Cases where no decision has been made may be due to the referral lapsing or being withdrawn, assessment ceasing while waiting for information from the proponent, or the assessment still being undertaken.

Source: ANAO based on Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment data.

1.10 Decisions on referrals, assessments and approvals and related administrative actions must be made within timeframes specified in the EPBC Act. The department’s performance against these timeframes is published in its annual report. For the three key decisions (referral, assessment method and approval decisions), the department made only five per cent within statutory timeframes in 2018–19 (20 out of 368 decisions).

1.11 Referrals, assessments and approvals were part of Outcome 1, Program 1.5 (Environmental Regulation) of the Department of the Environment and Energy.9 In the department’s 2019–20 Portfolio Budget Statements10, Program 1.5 (which includes other environmental regulation) was allocated $50.2 million.11

1.12 As part of the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2019–20, the government announced $25 million over two years ‘to reduce unnecessary delays’ in environmental assessments and approvals. The additional funding was designed to address the backlog of environmental approval applications, with a focus on major projects.12 The department informed the ANAO that the budget for referrals, assessments and approvals in 2019–20, including this additional funding, was $20.3 million. As at February 2020, a total of 141 staff are allocated to referral, assessment and approval related work.13

Previous reviews

Parliamentary inquiries

1.13 The Parliament has conducted multiple inquiries into aspects of environmental regulation under the EPBC Act in recent years, including the:

- Senate Environment and Communications References Committee inquiry into Australia’s faunal extinction crisis14;

- Senate Select Committee on Red Tape, inquiry into the Effect of red tape on environmental assessment and approvals15;

- Senate Environment and Communications References Committee inquiry into the Continuation of construction of the Perth Freight Link in the face of significant environmental breaches16; and

- Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit inquiry, which included Auditor-General Report No. 43 2013–14, Managing Compliance with Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Conditions of Approval.17

Previous Auditor-General reports

1.14 Previous ANAO performance audits have examined elements of the department’s regulation under the EPBC Act in 2002–03, 2006–07, 2013–14, 2015–16 and 2016–17.18 Several weaknesses have been noted, including:

- a low likelihood of receiving referrals on all actions that may significantly impact matters of national environmental significance;

- delays in meeting statutory timeframes under the EPBC Act; and

- deficiencies in compliance monitoring and enforcement arrangements, relating to procedural guidance, risk-based compliance monitoring strategies, IT support systems and compliance intelligence capabilities.

1.15 The 2016–17 ANAO audit followed up the department’s progress in addressing the recommendations of the 2013–14 report on managing compliance with conditions of approval. While progress had been made against all five recommendations, limited progress had been made in implementing broader initiatives to strengthen the department’s regulatory performance.

Other reviews

1.16 Other major reviews of functions relating to referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Major reviews relating to referrals, assessments and approvals

|

Date |

Description of review |

Outcome |

|

October 2008 |

First independent review of the EPBC Act,a by Dr Allan Hawkeb |

Found that the EPBC Act was repetitive, complex and overly prescriptive, suggested that it be repealed, redrafted and replaced, and made 71 recommendations. The government generally agreed with the principles of the report but did not implement the reform package, choosing instead to amend and refine the existing Act. |

|

October 2015 |

Review of the department’s regulatory maturity, by Mr Joe Woodwardc |

Found the department’s approach to regulation was sound but lacked many elements of a mature regulator including overarching regulatory posture and clear performance measures. The government accepted the findings and established a project to implement the recommendations. |

|

March 2018 |

Review of interactions between the EPBC Act and the agriculture sector, by Dr Wendy Craik AMd |

Recommended a more proactive and strategic approach to protecting the environment and improving interactions between farmers and the department. The government acknowledged the report and committed to work with the sector, drawing on the recommendations of the report. |

|

August 2019 |

Productivity Commission study into resource sector regulation |

The final report is expected to be provided to the government by August 2020. |

|

October 2019 |

Second independent review of the EPBC Act,a led by Professor Graeme Samuel AC |

The final report is expected to be provided to the government by October 2020. |

Note a: The EPBC Act Section 522A requires there be an independent review at least once every 10 years.

Note b: Hawke, A. The Australian Environment Act – Report of the Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, 2009.

Note c: Woodward, J. Regulatory Maturity Project Final Report, 2016.

Note d: Craik, W. Review of interactions between the EPBC Act and the agriculture sector. Independent report prepared for the Commonwealth Department of the Environment and Energy, 2018.

Source: ANAO based on public documents.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 Effective administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the EPBC Act reduces impacts on the environment and facilitates economic development. Previous ANAO audits have identified shortcomings in the department’s administration of regulation under the EPBC Act in relation to the timeliness, consistency and effectiveness of regulatory actions.

1.18 The audit topic was listed in the ANAO Annual Audit Work Program in 2018–19 and 2019–20. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit identified the topic as an audit priority of the Parliament for 2019–20. The department requested that the ANAO commence the audit in July 2019 to inform the second statutory review of the EPBC Act, currently underway. The audit will provide an independent and up-to-date perspective on the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions and complement the statutory review of the Act.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment’s administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following three high-level audit criteria.

- Are governance arrangements sound?

- Is the administration of referrals and assessments effective and efficient?

- Are conditions of approval appropriate and assessed with rigour?

1.21 The audit scope included: use of compliance intelligence to inform regulatory activities; conduct and oversight of referrals, assessments and approvals; timeliness and efficiency in administering referrals and assessments; monitoring of pre-commencement conditions of approval; and performance measurement, monitoring and evaluation.19 It did not include monitoring of compliance with post-commencement conditions of approval or strategic assessments under the EPBC Act.

Audit methodology

1.22 To conduct this audit, the ANAO examined departmental documentation, analysed IT system data, tested samples of decisions, interviewed departmental staff and received public submissions.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $419,156.

1.24 The team members for this audit were Mark Rodrigues, Isaac Gravolin, Se Eun Lee, Sam Khaw, Thiago Gomes and Michael White.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

This Chapter examines whether the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (the department) has established sound governance arrangements to support its administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

Conclusion

The department has not implemented sound governance arrangements to support its administration of referrals, assessments and approvals of controlled actions.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at developing a compliance intelligence strategy, assessing compliance risk across regulatory regimes, improving governance oversight arrangements and developing appropriate performance measures. It also suggested that the department prioritise investment in IT capability.

2.1 Sound governance arrangements support effective and efficient regulation. This includes the establishment of frameworks to ensure that efforts are targeted to the level of risk, decisions are made consistently and objectively, and regulators are accountable for achieving their objectives. To determine whether the department has established sound governance arrangements, the ANAO examined whether:

- appropriate arrangements are in place to gather and manage compliance intelligence;

- regulation is informed by an assessment of compliance risk;

- sound oversight has been established; and

- appropriate performance measures have been established.

Are appropriate arrangements in place to gather and manage compliance intelligence?

Arrangements for collecting and managing information on compliance with the EPBC Act are not appropriate. The department does not have an appropriate strategy to manage its compliance intelligence, limiting its access to the regulatory information necessary for complete and accurate compliance risk assessments. Key limitations include poor linkages between sources of regulatory information and a lack of formal relationships to receive external information.

2.2 Understanding how and where non-compliance is likely to occur allows regulators to target their activities to those areas with an elevated risk of non-compliance. Appropriate arrangements to collect and manage compliance intelligence are necessary for regulators to be able to understand where non-compliance may occur.

2.3 In 2016, the department’s Regulatory Maturity Project Final Report (Regulatory Maturity Review) found that the department ‘does not have an established strategic intelligence capability’, limiting its ability to assess the risk of non-compliance with the Act. The review recommended improving the approach to compliance intelligence by working with co-regulators and enhancing IT capabilities, which was accepted by the department.20

2.4 The department has implemented a range of measures to strengthen its compliance intelligence capability.21 This includes the establishment of a departmental Office of Compliance and Chief Compliance Officer in July 2017 to consolidate environmental compliance intelligence and enforcement functions, new positions within the Office of Compliance responsible for strategic intelligence, and new compliance procedures and plans.22

2.5 The ANAO examined whether these measures supported an improved compliance intelligence capability with appropriate arrangements to gather and manage regulatory information.

Collection of regulatory information

2.6 Collecting regulatory information from a range of reliable sources assists regulators to ensure their information is complete and accurate. As the department operates within a network of environmental regulators, it should have arrangements to collect information from those sources as well as its own activities.

2.7 The department stores information from its own activities in multiple business systems across the department.23 It has also implemented measures to support internal information sharing, including establishing the Office of Compliance to oversee all compliance activities, iterative restructures to internal business committees, and establishing communities of practice.

2.8 To receive information from external sources, the department has established connections with a range of co-regulators:

- the department’s Chief Compliance Officer is vice-chair of the Australasian Environmental Law Enforcement and Regulators Network (AELERT)24;

- the department participates in joint site inspections with co-regulators25 and receives information about compliance with approval conditions;

- departmental officers engage with states on assessments and approvals that require both Commonwealth and state approval; and

- the department has an officer embedded in the Department of Home Affairs Border Intelligence Fusion Centre.

Arrangements between co-regulators

2.9 In 2016, the Regulatory Maturity Review noted that the department’s arrangements for managing relationships with other regulators were ‘out of date or inadequate’, recommending that it ‘formalise its relationships… including in relation to routine data sharing’.26

2.10 The department’s response to the recommendation was grouped with other recommendations, to be addressed by a single project. However, the scope of the project did not include the establishment of formal relationships with co-regulators and documentation (including the finalisation report) does not indicate that the recommendation was implemented.

2.11 Bilateral agreements with states and territories contain provisions to support information sharing. Each agreement contains commitments to cooperate in monitoring compliance with conditions of approval, including through establishing complementary arrangements. However, complementary arrangements have not been established. In addition, only one agreement commits to a regular schedule for the provision of compliance information.27

2.12 In the absence of agreed and structured information sharing arrangements, information received from co-regulators will be reactive, issue-based and dependent on personal relationships. As a consequence, compliance information may be incomplete and limited in value for strategic planning.

Management of regulatory information

2.13 Once regulatory information is obtained, it should be managed in a way that enables it to efficiently inform compliance intelligence. The department stores regulatory information in multiple systems maintained by different business areas (Table 2.1). However, the department has not established a procedure to extract all relevant compliance information from each of these different systems. There is no system to store and risk assess open source information, develop custom risk profiles for regulated entities, or undertake projects to gather intelligence.28

Table 2.1: Systems containing regulatory information

|

Information |

System/application |

Business use |

|

Reports of suspected non-compliance |

Spreadsheets |

Management of allegations |

|

Other intelligence information |

Target Knowledge Base |

Management of unstructured intelligence information |

|

Compliance case management |

Compliance and Enforcement Management System and spreadsheets |

Case management and intelligence |

|

Referrals, assessments and approvals |

Environment Impact Assessment System and spreadsheets |

Management of referrals and assessments information and workflows |

|

Spatial data |

Environment Matters Mapping Application, Protected Matters Search Tool and Wyliea |

Spatial data on the distribution of matters of national environmental significance |

|

Species data |

Species Profile and Threats Database |

Records threatened species and ecological communities, key threatening processes and critical habitats |

|

Wildlife trade |

Wildlife Trade System |

Management of seizure-related data and workflows |

Note a: Wylie is a mapping tool that displays matters of national environmental significance at a chosen location.

Source: ANAO based on Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment information.

2.14 The ability of the department to bring together information from these systems to support regulatory objectives is limited by a lack of linkages between systems and data management issues. In 2017, a departmental strategic intelligence report summarised these limitations, including:

- compliance data being stored in multiple locations, with no location containing all relevant information for a case;

- tracking sheets being updated as cases progressed, leading to the loss of previous data;

- poor quality data entry, hampering bulk data analysis29;

- data lacking necessary information for timely and accurate identification of trends30; and

- anecdotal information that does not constitute an incident or breach (but which may indicate a broader trend or issue)31 not being effectively captured.

IT system improvement projects

2.15 The department has commenced multiple projects to improve the identified issues with its business systems and management of regulatory information. However, as at January 2020, none of these projects have been completed (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Outcome of projects to improve management of regulatory information

|

Year |

Project |

Description |

Outcome |

|

2015 |

Intelligence Capability Project |

Project to map regulatory information requirements and develop a solutions architecture to establish links between systems. |

Became part of the ICT Regulatory Maturity Program. |

|

2017 |

ICT Regulatory Maturity Program |

IT process to support regulatory maturity through integrated IT systems in response to the Regulatory Maturity Review.a |

A range of IT database modernisation and remediation projects and business application work commenced under this process. None of those projects addressed compliance intelligence capability. |

|

2017 |

Regulatory Compliance System Improvements Roadmap |

Component projects included developing standardised regulatory compliance system processes, migrating compliance data from existing systems and developing a client incident reporting service. |

These projects did not commence. |

|

2018 |

ICT capital investment process |

Departmental process to catalogue the ICT systems, risks and development needs of each division to inform the development of a consolidated plan for ICT capital investment. |

In 2018–19, 29 ICT capital projects were selected for commencement at a cost of $13.9 million. Of the 7 business application and information management projects selected, 1 related to the development of a business case for intelligence and analytics capability. This project was not included in the 2019–20 ICT work program. |

Note a: The Regulatory Maturity Review recommended that as ‘a high priority, the department should bring forward investment in an integrated end-to-end IT system to improve its reliability, effectiveness and efficiency’.

Source: ANAO based on Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment information.

2.16 Without implementing these improvements, the department’s ability to utilise information from internal business systems and develop a comprehensive view of the regulatory landscape is limited. Key internal systems do not provide for a consistent, accurate and holistic view of regulated entities. This has resulted in staff checking multiple systems and re-entering information already stored elsewhere.

2.17 These limitations increase the risk that the department’s view of regulated entities and compliance risks is not complete and accurate. To address this, the department should prioritise ICT system improvement projects to improve its compliance intelligence capability. In addition, it should develop a compliance intelligence plan that includes: its approach to compliance information collection; data access arrangements; interdependencies with co-regulators; and actions to address gaps and limitations until long-term solutions are implemented.

Recommendation no.1

2.18 The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment develop and implement a plan to collect and use regulatory information, and address gaps and limitations in information management, to better enable compliance information to be used to inform regulatory strategy and decision-making.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

2.19 The Department recognises the importance of collecting and managing regulatory information to inform regulatory decision making. The Department acknowledges that the existing processes require improvement.

2.20 Building on the Department’s existing Compliance Framework, the Department will develop and implement a plan to strengthen the processes for collection and use of regulatory information, including compliance intelligence. The Department will implement other necessary actions to support information sharing, including system improvements, in the context of the EPBC Act Review. This will enhance governance and result in improved efficiencies of our current approach and practices.

Is the regulatory approach to referrals, assessments and approvals informed by an assessment of compliance risk?

The regulatory approach to referrals, assessments and approvals has not been informed by an assessment of compliance risk. Strategic compliance risk assessments do not inform regulatory plans. In one instance, the department’s activities to promote voluntary compliance were aligned with an identified risk of inadvertent non-compliance in the New South Wales agriculture sector. The approach to individual referrals, assessments and approvals is not tailored to compliance risk.

2.21 Regulators that assess the risk of non-compliance are better positioned to target regulatory activities towards areas of greatest impact. Strategic risk assessments can inform the design of regulatory approaches, including the allocation of resources between regulatory activities (such as promoting voluntary compliance, individual assessments and approvals, and compliance monitoring functions). Operational and tactical risk assessments may be used to inform decision-making on individual actions.

2.22 This audit reviewed the department’s compliance risk assessments and the extent to which they influenced the regulatory approach to referrals, assessments and approvals. This included an examination of:

- whether the department was assessing compliance risk across all of its regulatory responsibilities;

- the department’s strategic intelligence assessments;

- alignment of regulatory plans with strategic intelligence assessments; and

- whether the approach to individual referrals, assessments and approvals was targeted at the level of risk.

Assessment of compliance risk across regulatory responsibilities

2.23 Regulators are better positioned to target their effort if they consider compliance risk across all of their regulatory responsibilities. The department’s environmental responsibilities also include regulation of wildlife permits, hazardous waste, ozone protection and synthetic greenhouse gas management.

2.24 No assessment of compliance risk across all of the department’s environmental regulatory responsibilities has been completed. As part of its regulatory maturity project in 2019, the department began planning an overarching compliance risk assessment, which is scheduled to commence in 2020–21.

2.25 The department has not established arrangements to prioritise its assessments of compliance risk between its environmental regulatory responsibilities. It has commenced drafting a schedule for future compliance risk assessments across each piece of legislation it administers.32

2.26 Without an overarching assessment of compliance risk across its regulatory responsibilities or a process to prioritise its assessments, the department is not well positioned to develop a complete view of compliance risk. This weakens the basis of its strategic risk assessments and limits its ability to align regulatory functions and resources to the risk of non-compliance.

Recommendation no.2

2.27 The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment conduct an up-to-date risk assessment of non-compliance across its environmental regulatory regimes and develop and implement arrangements to prioritise its strategic compliance assessment.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

2.28 The Department acknowledges that it is important to use current risk assessments of non-compliance to appropriately target its regulatory activities. The Department will build on its Compliance Framework, including work already underway, to conduct an up-to-date risk assessment of non-compliance across the range of environmental legislation administered by the Department. In completing this work, the Department will prioritise the strategic compliance assessments.

Strategic intelligence assessments

The EPBC Act — a horizon scan

2.29 The EPBC Act — a horizon scan, November 2017 was the first strategic intelligence assessment produced by the Office of Compliance. Its purpose was to identify potential sources of non-compliance with referral requirements and conditions of approval, to support strategic and operational planning.

2.30 The assessment identified key compliance risks by sector and included considerations such as the basis of the analysis, assumptions, information gaps, and likelihood, consequence and risk ratings. Key risks identified included high volumes of land clearing for agriculture without referral or approval, non-compliance in residential development projects and continued non-compliance in the mining sector.

2.31 Proposed actions in response to the assessment were considered in September 2018.33 The division of the department responsible for referrals, assessments and approvals noted in October 2018 that it ‘will look to progress many of the draft actions as part of the upcoming review of the EPBC Act, or as part of its normal business operations during 2018–19’. The department’s records do not indicate work has been undertaken on those actions.

State of Compliance 2018–19

2.32 In 2019, the Office of Compliance completed the State of Compliance 2018–19 — Strategic Intelligence Assessment. The report included compliance assessments across sectors including agriculture, residential development and hazardous waste. The report drew on data stored in internal business systems, open source information and stakeholder input.

2.33 The report stated that despite the substantial impact of agriculture on the environment, agricultural development is rarely referred to the department. It noted that compliance risks are likely to increase as ‘new, expanded or intensified agricultural activity becomes more common’, and that ‘ongoing hardships’ are likely to drive non-compliance in smaller agricultural landholders.

2.34 Findings from the report aligned with existing pre-referral awareness activities which commenced in 2017 with the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI), including training NSW DPI staff and piloting draft guidelines for referring agricultural development in New South Wales.34 The Review of interactions between the EPBC Act and the agriculture sector noted these activities as a model for closer cooperation between states and territories and the department.35

2.35 The provision of improved guidance to regulated entities at risk of non-compliance may assist the submission and quality of referrals. However, as the department has not established a plan for increased engagement with the New South Wales agricultural sector, it is not well placed to assess the impact of those activities.

Alignment of regulatory plans with strategic intelligence assessments

2.36 The department’s approach to environmental regulation is established in its regulatory framework, which sets out the way the department develops and administers regulation.36 The framework outlines a model of regulation with responses proportionate to the behaviour of regulated entities, based on risk of harm, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Department’s risk-based regulatory approach

Source: Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment.

2.37 The regulatory framework is supported by a high-level compliance policy and an annual compliance plan. Of the five compliance outcomes listed in the 2019 compliance plan, one specifically refers to increasing compliance with the EPBC Act. Under this outcome, three compliance focuses are listed, including:

- supporting landowners, in partnership with state based regulators, to consider state and national environmental laws in parallel when planning agricultural development;

- monitoring compliance with approval conditions; and

- collaborating with domestic and international partners to detect and disrupt illegal wildlife trade.

2.38 Of these three compliance focuses, the first addresses a key risk identified in the department’s State of Compliance 2018–19 — Strategic Intelligence Assessment. The other two focuses are business-as-usual activities and do not reflect insights from the department’s strategic compliance assessments. Without addressing the other risks identified in strategic assessments (see paragraph 2.30), the department has limited assurance that its regulation is targeted to the areas of greatest risk.

Individual referrals, assessments and approvals

2.39 By tailoring the approach to individual referrals, assessments and approvals to the risk of each proposed action, effort can be targeted to the areas that will have the greatest impact on regulatory objectives. This would also reduce the administrative burden on entities proposing low-risk actions.

2.40 The administration of referrals, assessments and approvals under the EPBC Act inherently involves a consideration of the environmental risk of each proposed action. However, the department has not established a framework to target its efforts based on an assessment of the risk of each individual action. While risk is discussed generally in the department’s procedural guidance, prompting officers to consider environmental, legal, reputational and compliance risks, it does not indicate how risk assessments should be conducted or establish how the assessment should inform the level of regulatory effort applied.

2.41 The department has attempted to implement risk-based approaches to individual referrals, assessments and approvals. This includes recent efforts to reduce delays in referrals, assessments and approvals following the $25 million allocated to the department in December 2019 (paragraph 1.12). The key strategy in these efforts was a triage process whereby resources would be allocated to assessments and plans in proportion to the level of assessed risk. This was not implemented at the time of fieldwork.37

Have sound oversight arrangements been established to support regulatory activities?

While the department has established sound oversight structures, they have not been effectively implemented. Procedures for oversight of referrals, assessments and approvals by governance committees are not consistently implemented. Conflicts of interest are not managed.

2.42 Sound oversight arrangements are important to ensure that the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals under the EPBC Act is conducted efficiently, effectively and in accordance with the Act. Sound oversight arrangements enable management to: monitor regulatory performance; monitor progress against objectives and plans; and respond to emerging issues.

2.43 The ANAO examined whether the department had established sound governance arrangements to oversee the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals, including whether:

- the department’s governance framework supports effective oversight;

- activities were conducted in accordance with the governance framework;

- project reporting arrangements were effective; and

- conflicts of interest were identified and managed appropriately.

Governance framework

2.44 While the accountable authority is ultimately responsible for oversight of the department, operational oversight of referrals, assessments and approvals was the responsibility of the management committee known as the Environment Standards Division board (ESD board). The ESD board was established to provide strategic direction, determine objectives and manage performance. The ESD board existed from July 2015 to August 2019, after which point the responsibility transferred to the Environment Approvals Division (EAD) board.38

Terms of reference

2.45 The ESD board’s terms of reference included requirements for meeting weekly, twelve monthly review of the terms of reference, monitoring risks and progress against the business plan, and undertaking regular performance self-assessments.

2.46 The terms of reference do not specify the ESD board’s accountabilities or authority, as required under the department’s committee management policy. The terms of reference could also have been improved by including performance monitoring and reporting requirements, and timelines and mechanisms for performance self-assessments and oversight of risk and business plans.

2.47 The ESD board’s responsibilities did not include oversight of individual referral, assessment and approval decisions. In the absence of appropriate quality controls over these decisions (see paragraphs 3.49–3.51), the absence of oversight on key regulatory decisions limits the department’s assurance that its decisions are appropriate and aligned with regulatory objectives.

Conduct of board activities

2.48 The ANAO examined the papers of all ESD board meetings39 and found that its oversight was not conducted in accordance with its terms of reference (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Implementation of terms of reference

|

Terms of reference requirement |

ANAO assessment |

|

|

Monitoring progress of key business as usual areas within the division against the divisional business plan and annual operating plans |

■ |

There are no records in ESD board minutes or papers of any monitoring of progress against the divisional business plan. |

|

Undertaking regular self-assessment regarding key achievements, outcomes met and areas of improvement |

▲ |

A self-assessment of governance arrangements was conducted as part of a 2016 review, resulting in proposed changes to ESD’s arrangements that were not fully implemented. The self-assessment did not document consideration of ESD’s ‘key achievements, outcomes met and areas of improvement’. |

|

Meeting weekly |

■ |

The average time between meetings increased from 7.3 days in 2015 to 60.5 days in 2019.a |

|

Reviewing the terms of reference every 12 months |

■ |

Only 1 review of the terms of reference was documented in ESD board papers. |

Note a: The decrease in meeting frequency can partially attributed to a change from weekly to monthly scheduled meetings, agreed to by the ESD board in February 2017 but never incorporated into the terms of reference. However, the average time between ESD board meetings in 2018 and 2019 was 55 days, approximately half as often as the proposed monthly schedule.

Legend: ◆ appropriately implemented; ▲ partially implemented; ■ not implemented

Source: ANAO analysis based on Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment documentation.

2.49 The shortcomings summarised in Table 2.3 limit the ability of a management committee such as the ESD board to provide effective oversight of the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals. The absence of comprehensive self-assessments, reviews of progress against business plans and reviews of the terms of reference reduces assurance that oversight arrangements are effective. Furthermore, the ESD board’s lack of adherence to the established meeting frequency limits its ability to respond to emerging issues.

Oversight of projects

2.50 The ESD board also served as the divisional project board, to provide oversight through a recurring meeting agenda item in which it received reporting on the status of projects.

2.51 The procedures for project management reporting to the ESD board contained requirements for how often the board should receive reporting and what the reporting should contain. However, they did not include eight of the 14 project board roles and responsibilities recommended for inclusion by the department’s project management framework. These include endorsement of individual project plans, appointment and endorsement of project sponsors and managers, and recommending the engagement of independent assurance as required.

Compliance with procedures

2.52 Project management reporting to the board was inaccurate and non-compliant with procedures. Examination of all project reports, which include a high-level summary of all projects (including ‘traffic light’ reporting against different factors40) and individual project reports (required to be submitted for projects of high complexity or risk), identified that:

- 34 individual project reports were not submitted, out of a total of 176 required reports;

- 55 out of 93 ‘schedule’ traffic lights were not calculated in accordance with the procedures;

- 21 projects were removed from the high-level summary without being moved to the closed section or otherwise noted as closed in the report or board papers; and

- only one project report was submitted to the ESD board from December 2017 onwards, despite the procedure requiring reporting ‘approximately every quarter’.41

2.53 Of the 24 projects relating to referrals, assessments and approvals that were closed by the last project management report42, only nine were fully successful, with another nine never finalised.43 Projects that were not finalised or successful were often significant in the context of the department’s regulation. Examples include a project to streamline the assessment and approval process and provide greater consistency when applying final conditions to approved actions, and a project to assist the department assure itself of the quality of assessments conducted by state and territories under bilateral agreements.

2.54 Improved procedures for project oversight, with more accurate project reporting, will better enable the board to identify and address emerging project issues, contributing to improved project outcomes and therefore regulatory outcomes in future.

Oversight of probity risk

2.55 Under Commonwealth legislation, departmental staff are required to take reasonable steps to avoid real or apparent conflicts of interest and disclose any relevant material personal interests.44 As regulators of environmentally sensitive, high-value and often contentious development proposals, appropriate arrangements to manage conflicts of interest are particularly important for building public confidence in the department as a trusted regulator.

2.56 Conflicts of interest may arise through the personal interests of staff and their engagement with regulated entities, industry bodies and environmental organisations. The department has supported leave without pay for a staff member to work in an industry body (Minerals Council of Australia) and has pursued a potential secondment for a staff member to an environmental group (World Wildlife Fund). If not appropriately managed, such actions may give rise to conflicts of interest.

Conflict of interest policies

2.57 The department has established a conflict of interest policy that complies with Commonwealth legislation. It requires employees to regularly assess and review their personal interests, take reasonable steps to avoid conflicts, complete a declaration where conflicts are identified, take measures to manage any identified conflicts and record declarations on the department’s record management system.

2.58 The department’s committee management policy requires committees to have a standing agenda item requiring members to ‘disclose any actual or perceived conflicts of interest’.45 Records did not identify any agenda item on conflict of interest for the first 80 meetings46 of the ESD board. The next 17 meetings from April 2017 until the last meeting all included conflict of interest declarations on the agenda.47 No conflicts were declared.

Assessment and treatment of conflict of interest risks

2.59 The 2015–17 ESD fraud risk plan48 included multiple risk sources relating to conflicts of interest49 for referrals, assessments and approvals, resulting in two ‘high’ rated risks.50 It included three treatments for these risks: a conflict of interest register, fraud training to be completed by 90 per cent of staff, and half yearly reviews of the fraud risk plan. The department stated that it has not established a conflict of interest register as it has not identified any conflicts of interest, and was unable to provide evidence the other treatments had been completed.

2.60 The 2017–19 ESD fraud risk plan included one risk source relating to conflict of interest51, associated with one medium rated risk.52 No treatments for this risk were established.53

2.61 The division has not established a fraud risk plan for 2019–20 onwards. Without an active fraud plan to identify and treat potential conflicts of interests, there is an elevated risk of the regulation of referrals, assessments and approvals being influenced by conflicts of interest.

Recommendation no.3

2.62 The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment ensure that its oversight of referrals, assessments and approvals is conducted in accordance with procedures, and conflict-of-interest risks are identified and treated.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

2.63 The Department agrees that it is important to ensure that procedures for the oversight of administration of referrals, assessments and approvals are consistently implemented. Implementation of the Government’s congestion busting agenda has supported business improvements and policy reforms to lift performance against statutory timeframes, including more focused oversight arrangements. The Department will refine and update existing arrangements for ongoing management committee oversight for referrals, assessments and approvals under the EPBC Act to ensure they are conducted in accordance with procedures.

2.64 The Department is committed to the effective management of conflicts of interest in its administration of regulatory functions. A revised Conflict of Interest policy and system to support declarations will be rolled out Department wide in 2020. The Department also is currently consolidating the Fraud and Corruption Control Plans and associated risk assessments of the legacy Departments, to reflect the current risk landscape and ensure effective strategies are in place to control fraud and corruption risks.

Have appropriate performance measures been established?

The department has not established appropriate performance measures relating to the effectiveness or efficiency of its administration of referrals, assessments and approvals. All relevant performance measures in the department’s corporate plan were removed in 2019–20, and no internal performance measures relating to effectiveness or efficiency have been established. The department’s reporting under the regulator performance framework in 2017–18 was largely reliable.

2.65 A key element of regulatory governance is the establishment of appropriate performance measures that allow internal and external stakeholders to determine whether the regulator is achieving its intended results. The ANAO assessed the department’s external performance measures relating to referrals, assessments and approvals (reported under both the Commonwealth performance framework and the regulator performance framework) and its relevant internal performance measures.

Commonwealth performance framework

2.66 Commonwealth entities are subject to performance measurement and reporting requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 and accompanying guidance issued by the Department of Finance. These are collectively referred to as the Commonwealth performance framework.

2.67 Under the framework, entities must publish corporate plans for each financial year. Corporate plans must set out the entity’s purpose and provide performance measures that will measure the entity’s performance in achieving its purpose. Results against these performance measures are required to be provided in the entity’s annual performance statements, to provide accountability information to the Parliament and the public.

2.68 In 2018, the ANAO examined the department’s54 2016–17 performance measures, including those relating to referrals, assessments and approvals.55 The measures were found to be largely relevant and partially reliable, with their completeness unable to be determined. No efficiency measures were included. The ANAO also found that results and analysis in the performance statements contained inaccuracies, were not supported by suitable records, or both.

2.69 The department’s performance measures were updated for 2017–18 and 2018–19. This audit assessed the 2017–18 and 2018–19 performance measures relevant to referrals, assessments and approvals and found that they were largely relevant but not reliable. Reliability was largely limited by a lack of information on the methods of assessment and data sources used. No efficiency measures were included.

2.70 For 2019–20, no performance measures specifically relating to the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals were included in the corporate plan. Departmental documents indicated that no measures were proposed because the department could not find any relevant ‘outcome-based’ performance measures, as their impact was ‘masked by the cumulative contributions’ of other areas of the department.

2.71 The absence of performance measures relating to the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals inhibits accountability and transparency. Where outcome-level performance measures relating to the effectiveness of regulation are unavailable, do not exist or are too costly to collect, performance measures should include input, activity and output measures as proxies for effectiveness.56 In addition, the department should provide performance measures relating to the efficiency of its regulation.

Regulator performance framework

2.72 The regulator performance framework was released in October 2014 as part of a government commitment to reduce the cost of unnecessary or inefficient regulation imposed on individuals, business and community organisations.57 The framework requires regulators to publish annual self-assessments on their performance against six performance indicators.58 As at March 2020, the department has released self-assessments for 2015–16 and 2017–18.59

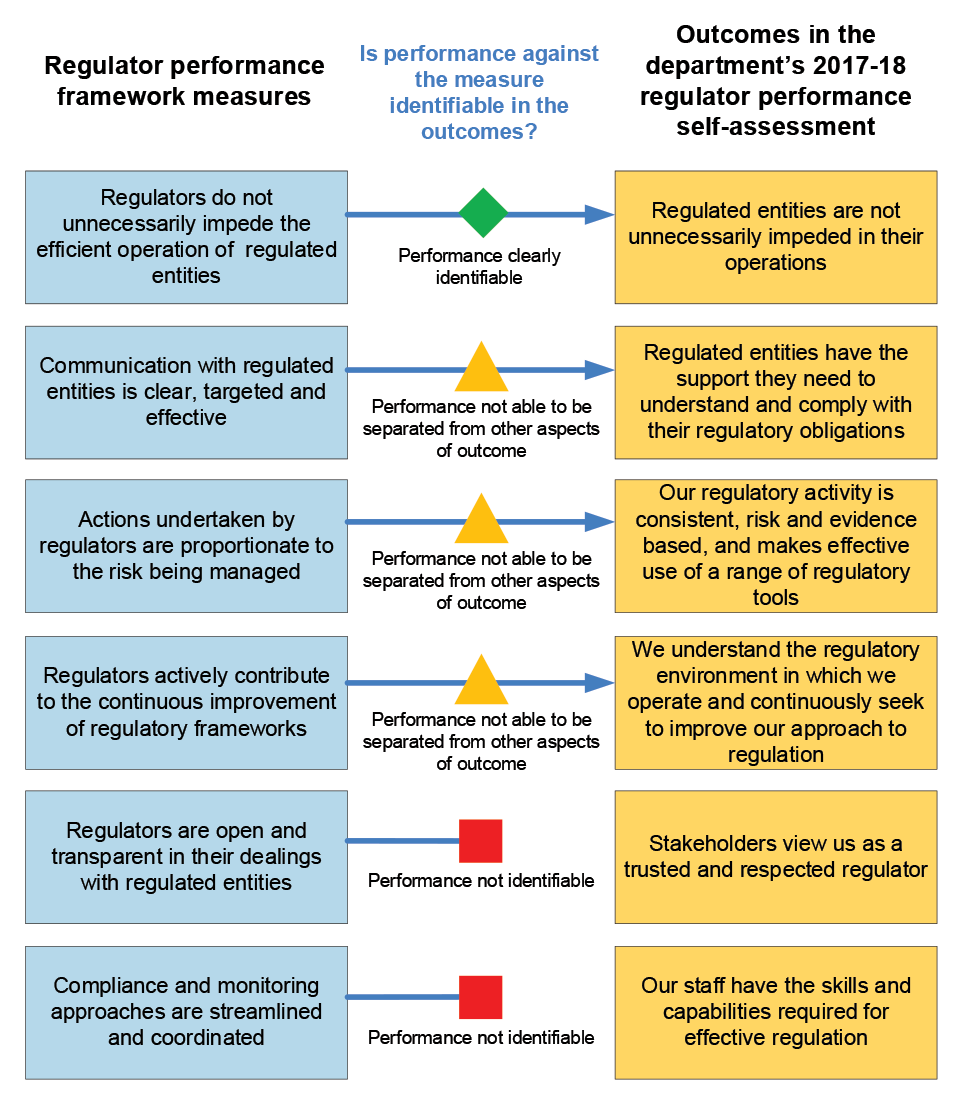

2.73 The ANAO examined the reporting in the 2017–18 self-assessment, in which the department adopted a different set of outcomes to those in the framework (see Appendix 1). The self-assessment, which was based on the results of surveys to stakeholders and departmental staff, was largely reliable. The report clearly presented the results against each survey question and provided a high level of detail about the methodology used to generate the results. Reliability could be further improved by explaining how external stakeholders were chosen to participate in the survey and how the results for individual questions determined the overall result for each outcome.

2.74 However, the ANAO identified three areas where the reporting was not compliant with the regulator performance framework (Table 2.4).

Table 2.4: Areas where the department’s 2017–18 regulator performance assessment was not fully compliant with the regulator performance framework

|

Regulator performance framework requirement |

ANAO assessment |

|

Where other performance measures are used in self-assessments, they must clearly articulate how they demonstrate performance against measures in the framework. |

Performance was only able to be clearly identified for 1 of the 6 measures in the regulator performance framework. 3 regulator performance measures were identifiable in the department’s outcomes but performance against the specific regulator performance measure was unable to be separated from other aspects of the outcome. More information is available in Appendix 1. |

|

A range of evidence from different sources should be used. |

Results were based solely on survey data, with 4 out of 6 outcomes using both the stakeholder and staff surveys, and 2 using only the stakeholder survey. |

|

Self-assessment must be timely. |

The self-assessment was published in September 2019 (14 months after the end of the period it was measuring) and the survey was undertaken between December 2018 and January 2019 (6 months after the period it was measuring). |

Source: ANAO based on Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment documents.

Internal performance measures

2.75 Internal monitoring of performance using well defined indicators or measures of effectiveness, efficiency and cost can be an invaluable source of information for a regulator on its strategies and areas for improvement. This is acknowledged in the department’s Evaluation Policy 2015–20, which requires ‘significant interventions’60 to develop performance measures addressing output, quality, impact and long-term outcomes.

2.76 The department has not established internal performance measures for the quality, impacts and long-term outcomes of its administration of referrals, assessments and approvals. It has established a number of output-level indicators, such as the number of statutory decisions made and the proportion of these decisions made within statutory timeframes. However, these do not provide any information on the effectiveness of the department’s regulation.

2.77 The department has highlighted the absence of appropriate internal performance measures and attempted to develop them on multiple occasions. These are summarised in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Attempts to develop appropriate performance measures relating to the administration referrals, assessments and approvals

|

Date |

Description of attempt |

Outcome |

|

December 2015 |

Development commenced on a set of output, quality, impact, and long-term performance measures. |

Document not completed. |

|

April 2016 |

Contracted re-development of ESD’s governance arrangements, including an outcome to develop a ‘rigorous approach to monitoring performance’. |

A suite of suggested internal reporting requirements were produced but not accepted. |

|

November 2016 |

Paper to ESD board notes ‘the need to improve our performance reporting’, proposing new section to be responsible for the division’s administrative and performance reporting responsibilities. |

New section established, performance indicators developed for output-level information. |

|

June 2017 |

New section informs ESD board that it is shifting its effort to ‘development of key performance indicators’ to tell a ‘coherent and persuasive performance narrative’. One proposed method was a ‘divisional performance reporting framework’. |

Not completed. |

Source: ANAO based on Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment documents.

Recommendation no.4

2.78 The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment establish internal and external performance measures on the effectiveness and efficiency of its regulation of referrals, assessments and approvals.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

2.79 The Department recognises the importance of establishing clear and appropriate performance measures so that the regulated community and the broader community can understand how the agency is achieving efficient and effective regulation. Implementation of the Government’s congestion busting agenda has seen the Department increase focus on improving measurement of performance against statutory timeframes and will look to build on this work.

2.80 The Department will build on existing internal and external performance measures with consideration to be given to the outcomes of the statutory review of the EPBC Act, and in line with Departmental corporate planning and reporting processes and the Commonwealth Regulator Performance Framework.

3. Referrals and assessments

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment’s (the department’s) administration of referrals and assessments is effective and efficient.

Conclusion

The department’s administration of referrals and assessments is not effective and efficient.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at establishing a quality assurance framework and efficiency benchmarks for referrals and assessments. The ANAO also suggested that the department consider more detailed guidance for complex decisions, prioritise investment in IT capability enhancements, establish a framework for prioritising its work and implement arrangements to ensure that staff complete mandatory training.

3.1 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires entities to be governed in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources. Proper use, as defined in the PGPA Act, is efficient, effective, economical and ethical.

3.2 Effective and efficient administration of referrals, assessments and approvals under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) enables the achievement of the Act’s objectives while minimising the use of public resources. To assess whether the department’s administration of referrals and assessments is effective and efficient, the ANAO examined whether:

- systems and processes for referrals and assessments support the achievement of requirements under the EPBC Act;

- referrals and assessments are undertaken in accordance with procedural guidance; and

- referrals and assessments are being undertaken efficiently.

Do systems and processes for referrals and assessments support the achievements of requirements under the EPBC Act?

Systems and processes for referrals and assessments do not fully support the achievement of requirements under the EPBC Act. Procedural guidance does not fully represent the requirements of the EPBC Act and lacks appropriate arrangements for review and update. Information systems do not meet business needs and contain inaccurate data. Staff training is not supported by arrangements to ensure completion of mandatory requirements. There is no framework to prioritise work.

3.3 For the department’s administration of referrals and assessments to be effective and efficient, it must be supported by appropriate systems and processes. Systems and processes should provide staff with the information and resources necessary to make informed decisions that are consistent with the objectives and requirements of the EPBC Act.

3.4 The ANAO assessed the department’s systems and processes in place to support its regulation under the EPBC Act. Specifically, the ANAO examined whether:

- procedures for referrals, assessments and approvals are appropriate and aligned with the EPBC Act;

- supporting business and information systems are fit-for-purpose;

- regulation is supported by appropriate staff training arrangements; and

- an appropriate framework has been established to prioritise and allocate work.

Procedures for referrals and assessments

3.5 Well-defined procedures assist consistency in regulatory decision-making. Procedures should cover all major decision points, clearly define roles and responsibilities for decision-making and be consistent with relevant legislative requirements.

3.6 The primary source of procedural guidance for the administration of referrals, assessments and approvals is the Environment Assessment Manual (the manual). The manual was established in stages from June 2018, as previous guidance was out-of-date and inconsistent with internal procedures. The manual is supported by other documents and templates, which provide supplementary information and guidance.

3.7 The ANAO examined whether the department’s procedural guidance was complete, consistent with the EPBC Act and appropriately maintained.

Completeness