Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Compliance with the Wildlife Trade Provisions of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s management of compliance with the wildlife trade regulations under Part 13A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Summary and recommendations

1. The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), which is administered by the Department of the Environment (Environment), is the Australian Government’s primary legislation to protect Australia’s biodiversity and environment. Part 13A of the EPBC Act regulates the international movement of wildlife and wildlife specimens1, and encompasses Australia’s obligations under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Part 13A came into effect in January 2002, and was intended to support sustainable wildlife trade activities, promote conservation and address illegal wildlife smuggling.2

2. In Australia and internationally, wildlife is both legally and illegally traded:

- legal trade encompasses individuals and companies using wildlife for purposes including commerce, education, research, breeding, exhibition, and as household pets or personal items; and

- illegal trade ranges from single-item local bartering to commercial sized shipments and can include live pets, hunting trophies, fashion accessories, cultural artefacts, ingredients for traditional medicines, and meat for human consumption.

3. The legal trade in wildlife is regulated through a permit system with Environment responsible for assessing applications, and issuing or revoking permits. Environment relies on co-regulator entities, primarily the former Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS)3, to enforce wildlife trade arrangements on its behalf at the border. Enforcement responsibilities for both Environment and the ACBPS include inspecting goods, verifying permits, issuing caution notices, seizing suspected illegally traded items, and investigating and prosecuting serious non-compliance.

4. In 2013–14, Environment reported that 1983 permits were approved, and a combined total of 1640 caution notices and seizure notices were issued. Over this period, Environment finalised three investigations, two of which resulted in successful prosecutions, with the ACBPS completing 11 investigations, three of which resulted in successful prosecutions.

5. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s management of compliance with the wildlife trade regulations under Part 13A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

6. To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- administrative arrangements for managing compliance are appropriate;

- processes for gathering intelligence and assessing and managing compliance risks have been implemented;

- a risk-based compliance program to communicate regulatory requirements, and monitor compliance has been implemented; and

- there are effective arrangements in place to address non-compliance.

7. During 2014–15, the ACBPS was undergoing significant change in preparation for its integration with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) on 1 July 2015. This audit examined processes in place during 2014–15, and reflects the ACBPS organisational arrangements as at March 2015.

Overall conclusion

8. The effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s regulation of wildlife trade under Part 13A of the EPBC Act has been undermined by the absence of appropriate and tailored policy and procedural guidance, functional IT support systems and a risk-based approach to monitoring compliance. While the department considers the risks arising from this area of regulatory activity to be low compared to its other regulatory responsibilities, with settings and resources allocated accordingly, this position has not been informed by structured departmental-wide risk assessment focusing on its regulatory activities. As such, the department has limited assurance as to the adequacy of current settings. Further, the absence of an appropriate set of performance measures and reporting arrangements means that the department is not well positioned to report both internally and externally on the extent to which it is achieving its regulatory objectives.

9. The effective delivery of regulatory activities is also reliant on the former ACBPS (now DIBP) given its role as a co-regulator of the trade in wildlife. While, overall, the ACBPS had in place appropriate arrangements to undertake its responsibilities under the co-regulatory model, there is scope for improvements in the quality of regulatory data, the sharing of information and intelligence with Environment, and the greater coordination of compliance and investigation activities.

10. Environment has recognised the need to address shortcomings in its regulatory activities and is establishing a comprehensive regulatory compliance framework through a five year Regulatory Capability Development Program. This is an encouraging development and will assist the department to better understand the risks arising from its regulatory activities and tailor settings and target resources accordingly. Nonetheless, implementation of the program has been slower than expected.

11. The ANAO has made four recommendations designed to assist Environment and DIBP to:

- better assess and manage the risks to compliance with wildlife trade regulations;

- improve voluntary compliance through education and awareness activities;

- improve the data integrity of records; and

- strengthen performance monitoring and reporting.

Supporting findings

Compliance Intelligence and Risk Assessment (Chapter 2)

12. Environment is yet to establish an effective compliance intelligence capability for wildlife trade regulation, 13 years after Part 13A of the EPBC Act came into effect. Prior to March 2015, Environment had not extracted or analysed its wildlife trade information holdings, had not used intelligence analysis to inform its risk assessment of wildlife trade compliance, and was also yet to develop a risk-based strategy to monitor compliance with wildlife trade regulations. The department has commenced work to address these deficiencies, with projects underway to extract data for intelligence analysis and improve compliance information gathering and IT systems support.

13. While both Environment and the ACBPS have shared information relating to specific matters, data collected by both entities on the trade in wildlife has not been combined to deliver a holistic view of the risks posed to the legal trade in wildlife.

Monitoring Compliance (Chapter 3)

14. Environment has not developed a risk-based, compliance monitoring strategy to guide the delivery of compliance monitoring activities.

15. Environment’s IT systems, which support permit approval and acquittal, rely on manual data entry (with historic delays in the entry of acquittal data) increasing the risk to data integrity. The systems also provide limited reporting functionality, which has hampered the department’s ability to use collected data to inform the establishment of an effective risk-based monitoring process.

16. Environment has acknowledged these functionality and data integrity issues and the need to improve its business support systems for wildlife trade. The department is currently undertaking a project to define wildlife trade business systems requirements to deliver greater functionality. There is also scope for Environment to make greater use of alternative information sources, such as DIBP permit compliance data, to provide a more comprehensive perspective of compliance with wildlife trade regulation.

Responding to Non-compliance (Chapter 4)

17. Environment and the ACBPS have used education and awareness activities to encourage voluntary compliance. There is scope to better coordinate these activities.

18. There would also be benefit in DIBP updating its guidance to Australian Border Force staff to help to ensure that they are aware of their obligations. The ANAO identified inconsistent operational practices that created reputation risks through the incorrect release of wildlife specimens.

19. The quality of wildlife seizure data in Environment’s and the ACBPS’s IT systems is generally poor, with no automated exchange of data between the two entities or reconciliation of seizure records. The poor quality of seizure data limits its use for intelligence analysis and risk assessment.

Responding to Non-compliance (Chapter 5)

20. Environment’s and the ACBPS’s investigations frameworks largely aligned with established requirements although there is scope for Environment to improve policy and procedural documentation at the departmental level. Decision-making and documentation relating to the investigations cases of both entities was generally sound.

21. There were, however, deficiencies in Environment’s case selection process, with different case selection models used across areas of the department responsible for conducting investigations. Further, the department has not established a central repository to record allegations, referrals and investigations.

22. There would be merit in clarifying the process of referral between entities of allegations assessed as meeting investigation thresholds, but not able to be undertaken by an entity due to resource constraints. This would also lead to improved intelligence sharing.

Reporting of Wildlife Trade Regulation (Chapter 6)

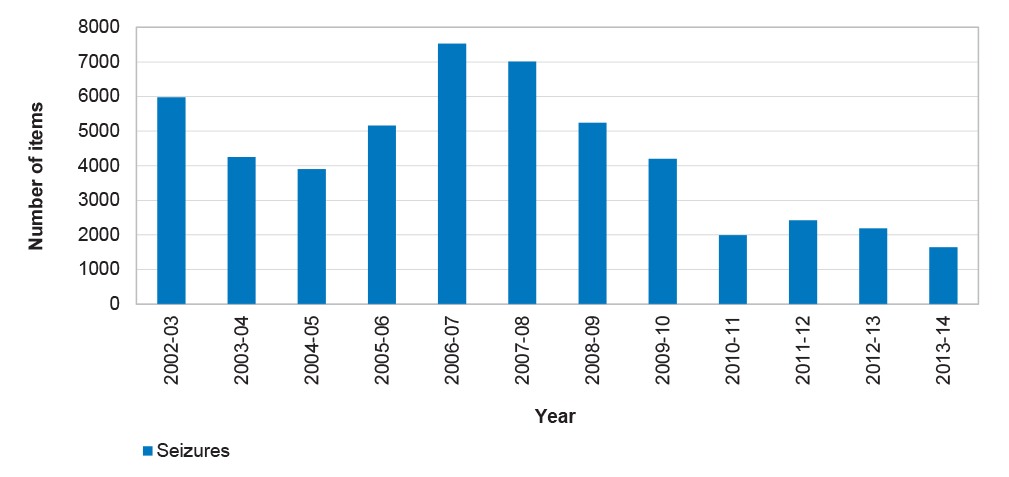

23. Environment does not have comprehensive key performance indicators against which it can illustrate trends over time and outline the extent to which Australia is meeting its international objectives. Developing more comprehensive key performance indicators would better position Environment and other stakeholders to assess the effectiveness of wildlife trade regulation.

24. The last publicly available data on Australian wildlife seizures was published in 2008. Environment currently provides only limited external reporting on the extent of illegal wildlife trade to and from Australia. As the lead regulator, and the only Commonwealth entity with access to both wildlife trade permit and seizure data, the department is well positioned to make such reporting available to the public.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Para 2.31 |

To better assess and manage risks to compliance with wildlife trade regulations, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Para 4.7 |

To improve voluntary compliance with wildlife trade regulation, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Para 4.28 |

To improve the integrity of wildlife trade data for compliance and regulatory purposes, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection:

Environment’s response: Agreed. DIBP’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Para 6.8 |

To improve the monitoring and reporting of wildlife trade regulation, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment develop appropriate key performance indicators and targets, and publicly report the extent to which the objectives for wildlife trade regulation are being achieved. Environment’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entities responses

Environment’s and DIBP’s summary responses to the proposed report are provided below, with the full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of the Environment

The Department of the Environment has considered the report and findings of the ANAO’s audit on Managing Compliance with the Wildlife Trade Provisions of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Environment agrees with the four recommendations contained in the report, as detailed in the responses to the recommendations.

Environment is committed to improving wildlife trade regulation and compliance under the EPBC Act. The report provides a sound foundation for improving the effectiveness of the department’s compliance approach to the wildlife trade provisions under Part 13A of the EPBC Act. Environment has commenced actions to increase the regulatory capacity for wildlife trade and is moving to a more risk-based, data driven and intelligence-focussed wildlife trade compliance programme.

Environment’s regulatory maturity is improving and the audit reflects the enhanced systems that are now in place for investigations and enforcement functions. The recommendations for wildlife trade outlined by this audit will assist the department to continue to improve its regulatory capacity. Environment is working closely with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection to implement our responses to the recommendations in areas of joint responsibility. Improved data exchange between departments will better inform Environment’s risk analyses on wildlife trade compliance and help reduce the threat of illegal wildlife trade to Australia.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (the Department) supports the Department of the Environment (Environment) to administer the wildlife trade provisions of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). Environment is responsible for policy and administration of the EPBC Act, while the Department enforces specific provisions of the EPBC Act on Environment’s behalf at the border.

The Department acknowledges that there is scope for improvements in the quality and provision of regulatory data with respect to wildlife trade. The Department supports the ANAO’s recommendation to strengthen the integrity of wildlife trade data for compliance and regulatory purposes, and will work collaboratively with Environment to adopt agreed data standards and develop improved information sharing arrangements.

The Department will also cooperate with Environment to support the implementation of other relevant recommendations of mutual interest relating to the collection of compliance data and the evaluation of publically available information to educate traders and travellers.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australia is a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international agreement between 181 countries aimed at ensuring that the international trade in wildlife species does not threaten the species’ survival.4 The convention provides a framework for enforcement through domestic legislation. Australia’s wildlife trade legislation is encompassed in Part 13A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). Part 13A came into effect in January 2002, and was intended to support sustainable wildlife trade activities, promote conservation and reduce illegal wildlife smuggling.

Legal and illegal trade in wildlife

1.2 In Australia and internationally, wildlife is both legally and illegally traded. The legal trade encompasses individuals and companies using wildlife for various purposes, including for commerce, education, research, breeding, exhibition, and as household pets or personal items. Australian examples include commercial kangaroo meat exporters, and zoos importing live endangered animals for captive breeding programs. Globally, the CITES Secretariat estimates the value of the legal trade in the billions of dollars.

1.3 The illegal trade in wildlife ranges from single-item local bartering to commercial sized shipments, and can include live pets, hunting trophies, fashion accessories, cultural artefacts, ingredients for traditional medicines, and meat for human consumption. Internationally, the illegal trade in wildlife has been estimated by different sources to be worth between US$7–US$23 billion annually.5 The trade in illegal wildlife products can be lucrative, for example, in January 2015 rhinoceros horn was worth more than the equivalent weight of gold.

1.4 The illegal trade in wildlife is widely acknowledged to: threaten the survival of particular species; involve animal cruelty; endanger the lives of the rangers who protect wildlife; pose a biosecurity risk by potentially introducing pests and diseases into agriculture and aquaculture industries and the environment; and the smuggled species can themselves become introduced environmental pests. Internationally it is now also widely recognised that illegal wildlife trade attracts organised criminal networks, and as such can have national security implications.6 Figure 1.1 provides some examples of Australian and non-Australian wildlife specimens seized on import to Australia or prior to export.

Figure 1.1: Examples of wildlife specimens seized in Australia

Note (a): Waste paper basket made from a rhinoceros foot (Environment).

Note (b): Australian reptiles illegally collected and seized before export (DIBP).

Note (c): Shipment of ivory seized in Perth, while being transhipped to Malaysia (DIBP).

1.5 Australia is not only an end point for international wildlife smuggling, with its biological uniqueness and diversity attracting illegal traders in Australian animals (primarily reptiles, birds, insects and spiders).7 The trade in live Australian animals is also among the most lucrative.8

Regulation of wildlife trade

International regulation

1.6 CITES, which entered into force on 1 July 1975, subjects the international trade in specimens of selected species to certain controls, including through a licensing system. The species covered by CITES are listed in three Appendices, according to the degree of protection they are determined to require, and approximately 5 600 species of animals and 30 000 species of plants are listed. The purpose of each of these appendices is summarised in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Purpose of CITES Appendices

|

CITES Appendix |

Purpose of Appendix |

|

I |

Species threatened with extinction which are or may be threatened by trade. Trade in specimens of these species is permitted only in exceptional circumstances. |

|

II |

Species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but which may become threatened unless trade in them is strictly regulated. |

|

III |

Species that are protected in at least one country, which has asked other CITES parties for assistance in controlling the trade. |

Source: ANAO summary of information in the text of CITES, Article II, 22 June 1979, p. 2.

1.7 Appendix I for example contains (but is not limited to) generally well known endangered species such as the great apes (chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans), the giant panda, many whales, tigers, and most populations of elephants and rhinoceroses. This appendix also contains species such as: all sea turtles; many birds of prey, cranes, and parrots; and some crocodiles, lizards, frogs, butterflies, mussels, orchids, and cacti.

Australian regulation of wildlife trade

1.8 CITES provides a framework for enforcement of wildlife controls through domestic legislation within those signatory countries. In Australia, Part 13A of the EPBC Act regulates the international movement of a broader range of species and circumstances than those specified under CITES, including the:

- export of Australian native species (unless identified as exempt9);

- import of all live plants and animals that could adversely affect native species or their habitats; and

- trade in elephant, cetacean (whales, dolphins and porpoises), rhinoceros and lion specimens is regulated more strictly in Australia than CITES requires as a minimum.10

1.9 There are a number of objectives of Part 13A, such as ensuring that Australia complies with its obligations under CITES and the Convention on Biological Diversity11, protecting wildlife that may be adversely affected by trade, and ensuring that the precautionary principle12 is taken into account in making decisions relating to the utilisation of wildlife.

Administrative arrangements

1.10 The Department of the Environment (Environment) is responsible for administering the EPBC Act and represents Australia in CITES decision-making forums.13 Environment, while the lead regulator, is a co-regulator with the former Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) for wildlife trade matters, with enforcement responsibilities delegated to specified Environment staff and to officers of the ACBPS (now officers of the Australian Border Force).14

1.11 The legal trade in wildlife is regulated by a permit system that is administered by Environment. ACBPS officers undertook border clearance functions for mail, passengers and cargo, as well as intelligence collection and investigations. The import and export of wildlife specimens may also be regulated by other Australian legislation, depending on the species and the circumstances.15

1.12 The co-regulation of the wildlife trade by Environment and the ACBPS is governed by a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The MoU, which was endorsed by the then Department of Environment and Heritage and the Australian Customs Service in 2002, sets out the administrative arrangements for the handling, storage and disposal of seized specimens, and how the entities will share information. It does not contain any provisions for regular reporting, or key performance indicators to measure the effectiveness of the arrangements. Environment approached the ACBPS in early 2014 to negotiate a new MoU, but negotiations were suspended in late 2014 given likely legislative and procedural changes arising from the integration of the ACBPS into DIBP. The entities agreed that existing arrangements would continue to operate, with negotiations likely to recommence in late 2015 or early 2016.

Stakeholders

1.13 Individual Australian states and territories also have environmental legislation that regulates the collection, trade and keeping of certain specimens, such as live native animals as pets. These regulators, and the Australian Government (through Environment), are represented on the Australasian Environmental Law Enforcement and Regulators neTwork (AELERT). AELERT provides a forum for Australian and New Zealand governments at local, state and national levels to: promote inter-agency cooperation; facilitate the sharing of expertise; and raise professional standards in the administration of environmental law.

1.14 There are also a number of international non-government organisations with Australian branches that have an interest in decreasing the illegal wildlife trade, with the most prominent being the: World Wide Fund for Nature; International Fund for Animal Welfare; Humane Society International, and TRAFFIC (a wildlife trade monitoring network).

1.15 The reported increase in the illegal trade in wildlife has also prompted a number of recent international forums, including the International Union for the Conservation of Nature—World Parks Congress held in Sydney in November 201416; and the Kasane Conference on Illegal Wildlife Trade held in Botswana in March 2015. This conference built on a declaration made at the February 2014 London Conference on the Illegal Wildlife Trade, by providing an opportunity for countries, including Australia, to report on progress against eradicating markets for illegal wildlife products, and strengthen law enforcement and partnerships.

Previous reviews and audit coverage

1.16 Over recent years, there have been a number of reviews and audits of aspects of the operation of the EPBC Act by independent reviewers, Environment’s internal auditors and the ANAO.

Review of the EPBC Act

1.17 In October 2009, the Report of the Independent Review of the EPBC Act (the Hawke Review) examined, among other things, the extent to which the objects of the EPBC Act had been achieved and the operation of the EPBC Act generally. The report identified the strong compliance and enforcement focus as a positive feature, but considered there was scope to improve arrangements for performance auditing and compliance. The review also noted broad concerns from stakeholders about the capacity of Environment to deliver the activities necessary to ensure the efficient and effective operation of the EPBC Act. One recommendation was specific to Part 13A, and was designed to:

- remove duplication;

- shift focus from the individual permitting system to assessment and accreditation of management arrangements for whole sectors; and

- streamline the different categories of approved sources for trading wildlife and wildlife products.17

1.18 The Australian Government agreed to implement this recommendation.18 However, legislative changes to the EPBC Act to implement this recommendation have yet to be presented to the Parliament.

Departmental internal audit coverage

1.19 In September 2013, Environment’s internal auditors finalised a review of Compliance and Enforcement Program Management in four divisions of the department. The audit found that each division was using inconsistent approaches for regulatory compliance and that these approaches were generally implemented reactively as a result of conflicting priorities and staff shortages.

1.20 In March 2014, Environment’s internal auditors finalised a review of the Wildlife Permits Program within the Wildlife Trade and Biosecurity Branch. The audit found that the framework for managing wildlife permits was adequate, but there were no monitoring processes to identify and manage non-compliance with permit conditions. The audit made five recommendations, including the: development of risk-based permit review criteria; and introduction of a risk-based compliance regime and conduct of regular spot checks of compliance with permit conditions.

ANAO performance audit coverage

1.21 The ANAO’s audit of Managing Compliance with EPBC Act Conditions of Approval (ANAO Audit Report No.43 2013–14) identified significant issues with Environment’s management of proponents’ compliance with environmental approvals. The ANAO made five recommendations directed towards: developing a compliance intelligence capability; undertaking periodic risk assessments; implementing risk-based compliance monitoring programs; improving the documentation to support enforcement responses; and performance reporting of the compliance monitoring function.19 Subsequently, in March 2015, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit’s inquiry into the ANAO’s report resulted in an additional two recommendations designed to improve Environment’s management of compliance.20

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

1.22 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s management of compliance with the wildlife trade regulations under Part 13A of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

1.23 To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- administrative arrangements for managing compliance are appropriate;

- processes for gathering intelligence and assessing and managing compliance risks have been implemented;

- a risk-based compliance program to communicate regulatory requirements, and monitor compliance has been implemented; and

- there are effective arrangements in place to address non-compliance.

Audit methodology

1.24 The audit involved the examination of documentation held by Environment and the ACBPS and data held in entity systems used to support the management of wildlife trade compliance. Interviews were also held with entity staff and a broad range of stakeholders with an interest in wildlife regulation.

1.25 This audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $616 000.

2. Compliance intelligence and risk assessment

Background

Compliance intelligence and robust risk assessment processes underpin an effective regulatory regime. Compliance information received and intelligence analysis conducted on a timely basis can inform the periodic assessment of the risks posed by regulated activities. These risk assessments can then be used to develop compliance strategies that target the greatest compliance risks to wildlife trade.

Conclusion

The maturity of intelligence and risk assessment arrangements varied across Environment and ACBPS, with Environment yet to establish an effective compliance intelligence capability and risk-based compliance program for wildlife trade. The effectiveness of Environment’s management of intelligence and assessment of risks was significantly hampered by poor IT systems and fragmented risk assessment processes. There was also an absence of appropriate information and intelligence sharing between the two entities.

Findings

Environment is yet to establish an effective compliance intelligence capability for wildlife trade regulation, 13 years after Part 13A of the EPBC Act came into effect. Prior to March 2015, Environment had not extracted or analysed its wildlife trade information holdings, had not used intelligence analysis to inform its risk assessment of wildlife trade compliance, and was also yet to develop a risk-based strategy to monitor compliance with wildlife trade regulations. The department has commenced work to address these deficiencies, with projects underway to extract data for intelligence analysis and improve compliance information gathering and IT systems support.

While both Environment and the ACBPS have shared information relating to specific matters, data collected by both entities on the trade in wildlife has not been combined to deliver a holistic view of the risks posed to the legal trade in wildlife.

Recommendation

The ANAO made one recommendation designed to strengthen Environment’s management of compliance information and assessment of risks to the effective regulation of wildlife trade.

Managing compliance information and intelligence

2.1 Compliance information may, in isolation, be inconclusive and it is the regulator’s ability to combine elements of information and analyse linkages that determines the effectiveness of its compliance intelligence capability. In the context of Part 13A of the EPBC Act, compliance intelligence should play an important role in informing Environment about the risks posed to the legal trade in wildlife and better place the department to either mitigate or manage these risks.

2.2 To inform its understanding of wildlife trade risk, Environment and the ACBPS have a number of internal and external information and intelligence sources (outlined in Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Sources of compliance information and intelligence

|

Source |

Compliance information and Intelligence |

|

|

Internal |

Permit applications and acquittals |

Information received from wildlife trade permit applicants and permit holders acquitting against permits. |

|

Wildlife Trade Operations and Wildlife Trade Management Plans |

Information received from the proponents of Wildlife Trade Operations and Wildlife Trade Management Plans, including during the assessment/approval process, and annual reporting (if required). |

|

|

Investigations |

Investigations can identify other intelligence, such as associates, or other businesses operating in the same manner. |

|

|

Caution and seizure notices |

Information relating to seizure and caution notices, including details about the items, senders and recipients. |

|

|

External |

Other regulators |

Compliance activities undertaken by other Australian and state and territory government entities, and international entities. |

|

Non-government organisations and researchers |

Allegations from the public, or their own research into the illegal trade. |

|

|

Members of the public |

Allegations of non-compliance received by the entities. |

|

|

Open source |

Internet sites, CITES trade database. |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Environment and ACBPS information.

Environment’s management of compliance information and intelligence

2.3 Intelligence functions within Environment for Part 13A are allocated across two departmental divisions: the Intelligence Team within Compliance and Enforcement Branch’s Investigations Section; and the Wildlife Trade Compliance Section within the Wildlife Trade and Biosecurity Branch.

2.4 In June 2014, the ANAO’s report on Managing Compliance with EPBC Act Conditions of Approval found that Environment did not have a documented strategy to guide its management of compliance intelligence. As at June 2015, this gap remained. The department’s Regulatory Policy (December 2013) and the separate and subordinate EPBC Act Compliance and Enforcement Policy (2013) make limited references to the capture, analysis and use of intelligence.

Collecting compliance information and intelligence

2.5 As outlined earlier, Environment collects compliance information and intelligence from a variety of sources, with:

- information relating to permits, wildlife trade programs and seizures collected through day-to-day work processes;

- allegations of non-compliance with wildlife laws obtained through contact details (telephone, facsimile and email) published on the department’s website, with reported information monitored by the Wildlife Trade Compliance Section; and

- investigations conducted by Environment also capturing intelligence.

2.6 However, Environment has not clearly assigned responsibility for collecting compliance intelligence to either the Investigations Section or the Wildlife Trade Compliance Section. There would be benefit in the department clarifying the responsibilities of its compliance teams to support the efficient collection, recording, analysis and sharing of intelligence.

2.7 Further, the receipt, recording and assessment of allegations have not been consistently performed across the two sections. For example, the Investigations Section’s Standard Operating Procedure states that allegations should first be recorded in the Compliance and Enforcement Management System21 (CEMS) and then assessed by the relevant line area. In contrast, prior to February 2015, the Wildlife Trade Compliance Section’s guidance material specified the initial recording of allegations as a separate file in the electronic filing system, and only after assessment were ‘valid’ allegations to be recorded in CEMS.22 While assessing the validity of intelligence is important, there are some allegations that may appear to have little or no significance when viewed in isolation. The failure to record all allegations in one system (along with assessments of those allegations) limits the department’s ability to detect important connections and trends.

Storage and use of compliance information and intelligence

2.8 A regulator’s ability to combine elements of information, and analyse linkages, substantially affects the effectiveness of its compliance intelligence capability. Environment’s information and intelligence storage methods and the use of this information is summarised in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Storage and use of gathered information and intelligence

|

Source |

Storage |

Use |

|

|

Information and intelligence received through day-to-day work processes |

|||

|

Permit applications and acquittals |

|

|

|

|

Wildlife Trade Management Plans and Wildlife Trade Operations |

|

|

|

|

Seizure and caution notices |

|

|

|

|

Investigations |

|

|

|

|

Allegations of non-compliance |

|||

|

Received by Wildlife Trade Compliance Section |

|

|

|

|

Received by Investigations Section |

|

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Environment information.

2.9 As Table 2.2 illustrates, Environment is yet to establish a centralised repository for compliance information and intelligence on Part 13A matters. Rather, data is stored in multiple IT systems and on electronic and hard copy files. As a consequence, the department is not well positioned to efficiently extract relevant data, undertake analysis or share compliance intelligence. The existence of legacy systems, which hold data that has not been migrated to replacement systems, also limits the department’s ability to bring together its compliance data. For example: historic permits are held on the Permit Administration Database (PAD), while the details of more recent permits are held on Permit Administration Workflow System (PAWS) and related information may be held on the former and current electronic filing systems.

2.10 While Environment is yet to develop an intelligence policy for its regulatory functions, as outlined earlier, in 2011 the Intelligence Team developed intelligence priorities according to departmental regulatory risks. In collaboration with the then International Wildlife Trade Section (now the Wildlife Trade Compliance Section), a number of projects to identify existing data sources, review targeted priorities, and evaluate existing intelligence about traditional medicines containing CITES species were agreed. The projects did not ultimately proceed because of difficulties experienced in accessing departmental data.

2.11 Issues relating to data access, in particular limited IT functionality associated with PAD and PAWS, have adversely impacted on Environment’s regulatory activities over a number of years.23 Prior to March 2015, the department had not extracted nor analysed its compliance information or intelligence holdings to inform an assessment of the risks associated with the legal and illegal wildlife trade, and the targeting of future regulatory activities. The department has advised the ANAO that a project has been established to extract data for intelligence analysis, and consequently assist with prioritising wildlife trade compliance activities. The project is expected to be completed in December 2015.

2.12 There is considerable scope to improve the collection and the storage of information and intelligence so that it is easily retrieved, analysed and shared to inform the identification of risk. The department has recognised the shortcomings of its intelligence functions, partly informed by recent internal and external audit coverage, and has recently commenced work to develop a department-wide intelligence capability. In April 2015, Environment engaged an external contractor to assess current compliance, enforcement and intelligence capabilities, and to determine potential IT solutions. As part of its Regulatory Capability Development Program (discussed in Chapter 4 at paragraph 4.2), the department also began scoping a project on regulatory intelligence gathering and analysis in May 2015.24

ACBPS’ management of compliance information and intelligence

2.13 The ACBPS had three branches responsible for strategic, operational and tactical intelligence, respectively, which were located in its Intelligence Division.25 The work of these three branches was guided by the ACBPS’ intelligence policy, which was outlined in five Practice Statements and associated Instruction and Guidelines.26 The Practice Statements outlined the ACBPS’ approach to: intelligence collection; recording of intelligence information; liaison with other law enforcement entities; dissemination of information internally and externally; and an internal client engagement model. These documents were released in 2007 and 2009. The ACBPS advised the ANAO that the documents are to be reviewed after the integration of the ACBPS and DIBP has been completed.

Collecting compliance information and intelligence

2.14 The ACBPS had three main sources of compliance information and intelligence: through its own operations; from the public and industry (through a program formerly called Customs Watch27); and from other Commonwealth or state/territory entities. All ACBPS officers had an information collection obligation, with information collected for a variety of purposes—from tracking goods that had been seized to recording intelligence that may have future use.

2.15 The ACBPS also had well established links with other Commonwealth and state/territory national security and law enforcement entities, as well as international entities such as the World Customs Organisation and Interpol. These entities exchanged information of interest, with the ACBPS also requesting information from these entities in relation to specific persons of interest. The ACBPS did not, however, actively task intelligence collection in relation to wildlife trade non-compliance given its broader responsibilities.

2.16 Allegations received by the ACBPS were processed by the Strategic Border Command Centre, which categorised the allegations into one of six categories. Information reports were then to be completed for ‘relevant’ reports, which were disseminated within the entity.

Storage and use of compliance information and intelligence

2.17 The National Intelligence System (NIS) was the ACBPS’ primary corporate intelligence recording system. NIS was used across a number of different work areas to enter reports that had an intelligence value internally or for partner entities. There was an expectation that officers would complete information reports for all major or significant detections.28

2.18 Compliance data was also held in other ACBPS systems, with all seizures of goods, including wildlife specimens to be recorded in the Detained Goods Management System (DGMS)—discussed further in Chapter 4. Depending on the work area, additional systems may also have had records associated with searches of travellers’ baggage or inspections of cargo. Information relating to investigations was recorded in a dedicated electronic case management system used for all referrals, investigation cases and outcomes.

Intelligence assessment

2.19 The ACBPS conducted annual strategic assessments of the threats posed to the Australian border and developed annual organisational intelligence priorities. These enabled the ACBPS to allocate intelligence resources to the highest priority threats and risks. While the illegal trade in wildlife has been acknowledged as a risk to the border in ACBPS threat assessments, in relative terms, the illegal trade in wildlife was not considered a high priority for the ACBPS. The completion of more detailed analysis using the compliance information and intelligence that is gathered in relation to wildlife trade would better position DIBP and Environment to determine the relative risk of the illegal trade in wildlife. Given the relative low priority of illegal wildlife trade in comparison to other border matters handled by DIBP, it may be more appropriate for Environment to undertake this analysis.

Sharing of information and intelligence

2.20 While Environment and the ACBPS respond to individual requests for information about specific matters relating to wildlife trade, neither entity has routinely shared information or intelligence to better inform the overarching assessment of compliance risks.29 The establishment of arrangements for the routine sharing of information and intelligence would better position Environment, as the lead regulator, to develop a more complete picture of the risks posed to the legal trade in wildlife.

Assessing compliance risks

2.21 A structured approach to risk assessment enables a regulator to identify, analyse and monitor regulatory risks, and to prioritise and plan compliance activities to mitigate these risks.

Environment’s assessment of compliance risk

2.22 Environment has developed an enterprise level risk assessment that identifies the key risks to the achievement of the department’s objectives. This assessment has identified risks arising from some of the department’s regulatory responsibilities. The department has not, however, specifically assessed the risks arising from its various regulatory activities and subsequently ranked its risk exposure from these activities. Such an assessment would enable the department to make informed decisions as to the regulatory settings to apply and the resourcing to allocate to its regulatory activities.

2.23 The assessment of compliance risks relating specifically to Part 13A of the EPBC Act is undertaken at the branch and section level. In 2013–14, the Wildlife Trade Compliance Section produced a Risk Assessment for Part 13A of the EPBC Act 1999 that detailed 12 risks, including: wildlife smuggling by permit and non-permit holders; intentional and organised small-scale smuggling; unintentional trade in personal items carried through international airports; illegal internet trade; and business risks such as loss of skilled staff and leakage of classified information. The risk treatments included: public awareness campaigns; updating internal policy and procedure documents; establishing closer links with wildlife law enforcement partner entities; and successful prosecutions.

2.24 An updated risk assessment was prepared in November 2014, and listed 14 risks, with the following ratings:

- three rated high—failure of internal and external stakeholders to prioritise wildlife trade non-compliance, inadequate IT capability, and increase in unsustainable trade due to Australia’s inadequate controls;

- 10 rated medium, including—failure to respond to non-compliance, failure to detect non-compliance, inadequate regulatory processes to facilitate action against non-compliance, and inadequate resourcing; and

- one rated low—lost or stolen forfeited specimens entering trade.

2.25 The other departmental sections with responsibility for wildlife trade matters have not prepared risk assessments, including for example, risks associated with non-compliance with permit conditions.

2.26 As discussed earlier, Environment has not extracted or analysed the compliance information or intelligence that it collects to inform an objective or holistic assessment of the risks associated with the legal and illegal wildlife trade. In the absence of this analysis, Environment cannot reliably determine the compliance risks to Part 13A, or develop a risk-based approach to compliance monitoring. The current fragmented approach to the assessment of risk for wildlife trade also impacts on the effectiveness of regulatory activities.

2.27 The March 2014 internal audit of wildlife permits acknowledged the department’s resource constraints and recommended that Environment introduce a risk-based compliance regime to assist in the implementation of a systematic approach to the review of permits with higher risk profiles. The department agreed with the recommendation, but stated that resource constraints made it difficult to prioritise the activity. A business case was to be developed for Executive consideration in the context of the 2014–15 Budget. The business case was subsequently overtaken by a project to define business requirements for a new Wildlife Trade and Compliance business system. This project is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 at paragraphs 3.8 and 3.14.

ACBPS’ assessment of compliance risk

2.28 The ACBPS’ risk management framework incorporated an annual entity-wide risk plan—the 2013–14 Risk Plan30—which was framed around the following three focus areas: key enterprise risks; border risks; and enabling functions. The border risks component of the plan discussed information sourced from the annual strategic threat assessment and included an assessment of whether current strategies and controls were adequate.

2.29 Border risk was described as the likelihood that people or goods would enter or leave the country without authorisation or without meeting the necessary conditions. While wildlife trade was not specifically mentioned in the border risks, it formed part of one of the 11 border risks—prohibited, restricted and regulated goods. Major threats affecting this risk included increasing trade and traveller volumes, resource constraints, and increasing economic integration and complexity. The assessment indicated that significant changes to border controls were not warranted, with the ACBPS to continue with current strategies. These strategies included continuing to: apply intelligence-led, risk-based targeting to ensure resources were focused on significant detections of higher risk prohibited items; and develop shared responsibility agreements with domestic partner entities.

2.30 The border risks articulated by threat assessments and risk plans cascaded down to inform the priorities set for operational activities performed by officers at the border. Given the relative low priority of illegal wildlife trade in comparison to other border risks, ACBPS officers interviewed by the ANAO advised that they targeted wildlife when intelligence was provided that enabled intervention activity.

Recommendation No.1

2.31 To better assess and manage risks to compliance with wildlife trade regulations, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

- collect, retain and regularly analyse compliance information from its own and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s holdings;

- identify and regularly review relevant risk factors for wildlife trade regulation; and

- develop and implement, as part of its compliance strategy, an annual risk-based program of compliance activities.

Environment’s response: Agreed.

2.32 Environment supports risk-based approaches to compliance and is improving the information systems that underpin the regulation of wildlife trade. The improvements will enable the management of risks to wildlife trade compliance to be based on the best available information, including through collaboration with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

2.33 Environment is engaging closely with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection to enable a coordinated approach to responding to the audit recommendations. Environment and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection have established a working group to ensure implementation of the audit response in areas of mutual interest.

- The Environment – Immigration and Border Protection working group will finalise an updated and revised Memorandum of Understanding to facilitate the regular exchange of enforcement and intelligence data on wildlife trade between departments.

2.34 Environment’s ability to receive and analyse the Department of Immigration and Border Protection data will be enhanced through investment in information technology. A scoping study was recently completed for a system to replace the current Compliance and Enforcement Management System database that is used for intelligence analysis and compliance case management.

2.35 Data sharing and access to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s information holdings will need to be in accordance with relevant legislative and security frameworks.

2.36 Environment has begun development of a new database to manage the issuance of wildlife permits and processing of seized wildlife products.

- An enhanced risk assessment for wildlife trade regulation has commenced. A Wildlife Intelligence Strategic Threat Risk Assessment is being developed and will be updated annually to inform the development of the annual risk-based compliance plan.

- Environment will update and better prioritise its annual compliance plans for wildlife trade to respond to the risks identified by Wildlife Intelligence Strategic Threat Risk Assessment.

2.37 From mid-2016, and based on the outcomes of Wildlife Intelligence Strategic Threat Risk Assessment and the priorities identified in the 2016–17 annual compliance plan, Environment will introduce a compliance monitoring program to address the risks of non-compliance with wildlife trade permits.

2.38 Environment has established a relationship with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection National Border Targeting Centre to assist with the implementation of enforcement and intelligence collection priorities identified in the annual compliance plans. Enforcement officers from Environment have access to National Border Targeting Centre and are strengthening the communication and coordination of intelligence and law enforcement between Environment and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

3. Monitoring compliance

Background

Proponents are required to obtain a permit from Environment before importing and exporting CITES-listed specimens, exporting regulated Australian native specimens, and importing some live animals and plants. The permits issued by Environment typically have common conditions, with departmental staff responsible for monitoring proponents’ compliance with these conditions.

Conclusion

Environment has not established robust processes and practices to gain a sufficient level of assurance that the conditions attached to permits and approvals for wildlife trade are being met nor to determine the extent of any non-compliance.

Findings

Environment has not developed a risk-based, compliance monitoring strategy to guide the delivery of compliance monitoring activities.

Environment’s IT systems, which support permit approval and acquittal, rely on manual data entry (with historic delays in the entry of acquittal data) increasing the risk to data integrity. The systems also provide limited reporting functionality, which has hampered the department’s ability to use collected data to inform the establishment of an effective risk-based monitoring process.

Environment has acknowledged these functionality and data integrity issues and the need to improve its business support systems for wildlife trade. The department is currently undertaking a project to define wildlife trade business systems requirements to deliver greater functionality. There is also scope for Environment to make greater use of alternative information sources, such as DIBP permit compliance data, to provide a more comprehensive perspective of compliance with wildlife trade regulation.

Permit monitoring

3.1 Permits are required before importing and exporting CITES-listed specimens, exporting regulated Australian native specimens, and importing some live animals and plants. Permits are categorised according to their nature, being commercial or non-commercial, with assessments to be conducted according to the purpose of the export or import. For example:

- non-commercial permits can be issued for the purposes of research, education, exhibition, conservation breeding or propagation, household pets, personal items, or traveling exhibition; and

- commercial export permits can be issued if specimens are sourced from an approved captive breeding program, artificial propagation program, cultivation program, aquaculture program, Wildlife Trade Operation (WTO), or Wildlife Trade Management Plan (WTMP).31

3.2 Permits can be issued as either single-use or multi-use and also have an expiry timeframe. Wildlife trade import, export and re-export32 permits state the species, type of specimen (such as leather, meat, or live animal) and the quantity of specimens that the permit covers. Permits issued by Environment typically have common conditions, regardless of the type of permit, such as including a requirement for the permit holder to complete and return a hard copy acquittal form within two weeks of the trade occurring.33

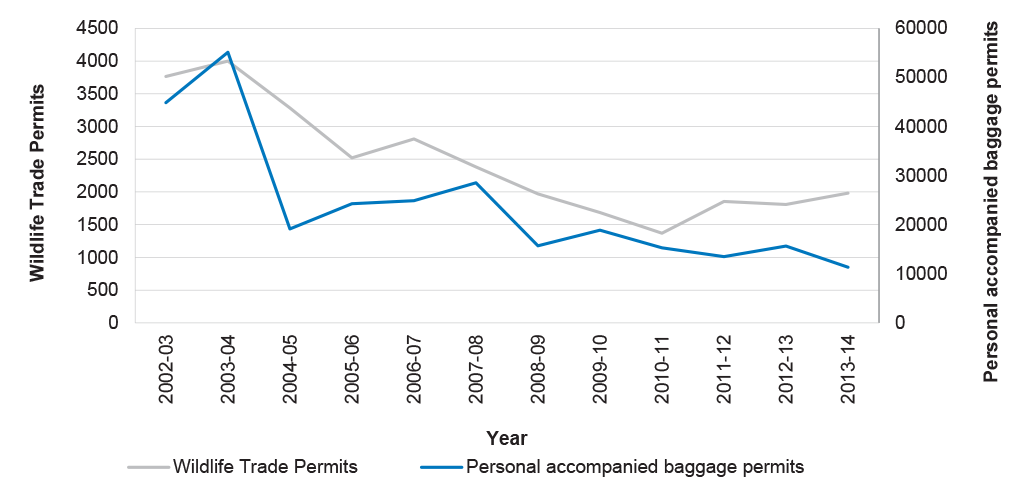

3.3 In the period from January 2002, when Part 13A of the EPBC Act came into effect, and 30 June 2014, Environment’s annual reports state that the department approved 31 284 wildlife trade permits and 299 372 personal accompanied baggage permits. The number of wildlife trade permits (illustrated in Figure 3.1) has fallen since 200234, but has remained relatively constant since 2008-09, with an average of 1700 approvals each financial year. The number of personal accompanied baggage permits is continuing to decline.35

Figure 3.1: Permits approved by Environment, January 2002 to June 2014

Source: Environment (and former departments responsible for the environmental legislation) Annual Reports, 2001–02 to 2013–14.

3.4 The data on approved permits must be viewed with some caution as, over time, Environment has varied its approach to the reporting of the types of permits that it has issued. For example, of the data on approved permits reported by Environment for 2011–12 to 2013–14, non-commercial research permit numbers were included in reported data for 2011–12 and 2012–13, but this figure was not included in the total number of import and export permits issued for these years (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Permit type by year, 2011–12 to 2013–14

|

Permit type |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

|

CITES specimens |

1540 |

|

1556 |

1741 |

|

Export of regulated native specimens |

289 |

|

233 |

223 |

|

Live specimens |

26 |

|

21 |

19 |

|

Export |

|

617 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Import |

|

1238 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Reported total1 |

1855 |

1855 |

1810 |

1983 |

|

Personal accompanied baggage |

13 529 |

|

15 635 |

11 358 |

|

Non-commercial research |

140 |

|

217 |

Not reported |

Note 1: The reported total is the total reported by Environment. The total does not include non-commercial research permits.

Source: Environment (and former departments responsible for the environmental legislation) Annual Reports, 2011–12 to 2013–14.

3.5 To assess Environment’s arrangements for post-approval monitoring of permits, the ANAO examined the department’s supporting IT systems and the processes established by Environment and the ACBPS to monitor the permits issued for goods being imported and exported.

Permit IT systems

3.6 Environment’s Permit Administration Workflow System (PAWS), which was implemented in May 2013, is a customised system designed and supported by a third party provider. Since its implementation, PAWS has received periodic upgrades, with a smartform application function introduced in November 2013, which has allowed online permit application submission.36 All permit acquittals are to be completed in hard copy by the permit holder, with acquittal data manually entered into PAWS by departmental staff. PAWS produces a number of standard reports for business management and external reporting purposes.

3.7 Prior to May 2013, the Permit Administration Database (PAD) was used by Environment for permit administration. PAD was an in-house developed database and workflow system. Permits were applied for and acquitted using hard copy forms, with staff manually entering this data into the system. While PAD was replaced by PAWS in 2013, it continues to be maintained by Environment, primarily because historic permit records were not migrated to the new system. PAD continues to be used for recording wildlife seizures37, as this functionality was not incorporated into PAWS, and for issuing personal baggage permits. Departmental staff are required to use both systems to determine an applicant’s permit history.

3.8 In relation to Environment’s permit IT systems, the March 2014 internal audit of wildlife permits found that the department was using multiple manual tools and IT systems for issuing permits, including the use of both hard copy and online application forms. The audit highlighted duplication in processes, with risks of inefficiency and inconsistency, and recommended consolidating the issuing of permits into one system, using online application forms only. Of the five recommendations made by the internal audit, two related to improving permit application processes, and one to determining whether migrating seizure data from PAD to PAWS was beneficial taking into consideration the potential cost. The department agreed with the audit’s recommendations and planned to complete a cost-benefit assessment of migrating seizure data by May 2014. This assessment was overtaken by a project to define business requirements for a new wildlife trade and compliance permit system. The department advised that system design and development are expected to occur during 2015–16.

3.9 The ANAO examined the integrity of the data held in PAWS, the processes and documentation surrounding its use, and the availability and accuracy of reports generated by the system. This examination identified:

- the absence of up-to-date system documentation describing the system and its data structures;

- errors in available standard reports.38 For example, the ANAO found that the standard ‘wildlife permit report’ (a report of the number of permits issued over a specified time span) was missing 63 valid permits (almost 2 per cent of 3344 permits) for the time period July 2011 to December 2014; and

- scope to improve the ability of PAWS to support ad-hoc management reporting.

3.10 Environment advised the ANAO that PAWS was designed as a workflow management system, and it has limited functionality for efficient downloading of data in a usable form. This limited functionality adversely affects the ability of line areas to extract and analyse data.39 As such, the department is not well positioned to use the data that it has collected to inform its administration of wildlife permits.

Environment’s monitoring of compliance with permits

3.11 Environment has established processes to manage compliance with permits, including permit reviews and acquittals. The department’s website states that a key aspect of the department’s compliance approach involves permit reviews.40 Permit reviews are intended to determine whether conditions attached to permits have been met, and whether goods being traded internationally have been obtained from an approved legal source. Reviews may be of documentation, conducted through site visits, or both. The department’s 2011–12 Annual Report stated that 14 reviews (0.07 per cent of the 1855 reported permits issued in that year) of wildlife permit holder compliance were conducted.

Permit monitoring approach

3.12 The March 2014 internal audit of wildlife permits found that, due to resource constraints, Environment had not undertaken routine monitoring processes (including permit reviews) to identify and manage non-compliance with permit conditions since July 2012. The internal audit further stated that non-compliance with permit conditions may lead to adverse impacts on animal welfare, border security, and reputational damage to the department as a regulator from adverse public opinions. Of the five recommendations made, two were designed to strengthen the department’s permit monitoring practices: developing and applying a risk profile to existing and new permit applicants; and introducing a risk-based compliance regime and conducting regular checks, based on the risk profile, to determine compliance with permit conditions.

3.13 Environment’s Audit Committee has previously expressed concerns about the absence of permit monitoring and recommended that a formal risk-based compliance regime, including both health checks and detailed reviews, be implemented. Further, it suggested that the department explore opportunities to engage formally with the ACBPS, particularly in relation to periodic reporting of permit use. The committee developed two action items relating to the administration of wildlife permits, including that the department’s executive needed to be made aware that an untreated risk existed so that an interim approach to address this issue could be considered. The audit committee’s tracking of action items notes completion of both items.

3.14 Environment advised the ANAO that the Wildlife Trade and Biosecurity Branch had reviewed the internal audit recommendations in April 2014, and noted that problems associated with wildlife permits management processes were one of a number relating to information management processes and systems in the department. These broader issues included incompatibility of multiple data management systems, poor or absent support for the maintenance of existing systems, and limited functionality of existing data management systems. The outcome of the review was the establishment of a project to define business requirements for a new wildlife trade and compliance permit system, discussed earlier in paragraph 3.8.

Permit acquittals

3.15 There are two sections within Wildlife Trade and Biosecurity Branch that are responsible for issuing permits and entering acquittals—Wildlife Trade Regulation and Wildlife Trade Assessments. Internal procedures manuals for these sections provide instructions for entering acquittal information into the permit system. However, while Environment advised that the compliance history of permit applicants is scrutinised, there is no guidance available to staff outlining the actions required for acquittals that are non-compliant with permits and no overarching compliance monitoring strategy for permits. In addition, Environment advised the ANAO that, prior to June 2014, the entry of acquittal data had been around two years in arrears due to resource constraints.41 Consequently, the department did not have up-to-date data to inform its monitoring activities until late 2014.

3.16 In the absence of a current permit monitoring strategy, Environment has established a permit acquittal process that involves system checks for compliance with permit conditions. The original design of PAWS included an online permit acquittal function with associated data validation at lodgement stage. However, the department advised that because of financial constraints this functionality was not implemented, and all acquittal information is manually entered. Further, the department advised that, after data entry, the validity of the acquittal information is automatically checked, with a ‘review’ workflow for items that require manual intervention.42

3.17 The ANAO’s examination of the 26 704 acquittal line items43 associated with 3353 PAWS permits issued between 1 May 2013 and 9 January 2015 found:

- two acquittals where the quantity of specimens exceeded the permitted amount, but the system status was marked as ‘compliant’;

- 52 acquittals that stated that the goods were shipped after the permit expired;

- 131 acquittals that stated that the goods were shipped before the permit was issued; and

- 1785 acquittals with a blank acquittal date marked as ‘compliant’ in the PAWS ‘standard acquittal report’. This report is used by Environment to monitor the extent to which permit acquittals comply with business requirements and to identify non-compliant records for review.44

3.18 The assurance that the department has over the compliance of permit holders with permit conditions is diminished because of poor data integrity and system functionality. The manual entry of permit acquittals data is time-consuming and, in addition to processing delays, increases the risk to data integrity. Some of the instances of apparent non-compliance with permit conditions found by the ANAO may have been the result of data entry errors. These issues relating to data integrity are coupled with system functionality issues that make it difficult for departmental staff to download data for use in analysing compliance risks.

3.19 Environment has recognised these functionality and data integrity issues and had identified the need to improve its business support systems for wildlife trade. The department is currently undertaking a project to define wildlife trade business systems requirements to deliver greater functionality (discussed earlier in paragraph 3.8). Notwithstanding these recent developments, the absence of a structured program of compliance activities is undermining the effectiveness of the regulatory framework. For example, Environment has not undertaken any permit reviews since July 201245, despite an internal audit and audit committee recommendation to do so in March 2014. It would be prudent for the department to establish interim compliance monitoring arrangements pending the scheduled completion of upgraded wildlife trade systems in 2015–16.

ACBPS monitoring of compliance with permits

3.20 The ACBPS advised the ANAO that, in its role in supporting and enforcing trade and industry policy at the border, it conducted some verification of imports and exports of wildlife specimens and permits. The total number of permits verified was not, however, recorded by the ACBPS.

3.21 The verification of permits occurred to differing degrees, dependent on whether the specimens were exported or imported, and the mode of transport (by mail, personally carried, or air or sea cargo). In relation to incoming mail and inbound travellers’ baggage, there was no pre-arrival information available to the ACBPS relevant to wildlife specimens. As such, the ACBPS was reliant on physical intervention, with:

- incoming mail items examined where screening (non-intrusive visual assessment of mail items or using x-ray) identified suspected wildlife specimens. However, only a proportion of mail was screened46; and

- incoming traveller’s baggage was examined where the traveller had declared a wildlife specimen47 or where screening or intelligence identified suspected wildlife specimens.

3.22 Outgoing mail and outbound traveller’s baggage were not routinely examined, unless as part of targeted operational activity or in response to intelligence or a declaration.

3.23 The verification of permits associated with air and sea cargo was more structured, with automated checks incorporated into the ACBPS’ Integrated Cargo System (ICS).48 Export declarations require self-selection of Australian Harmonized Export Commodity Classification49 codes, and for specific codes related to wildlife specimens, exporters are prompted to enter a wildlife trade permit number before the cargo can be authorised to leave Australia. Since August 2011, Environment has provided issued permit numbers and associated permit conditions to the ACBPS for uploading into ICS. There have been 18 978 electronic transactions relating to wildlife export permit numbers since that time.

3.24 All imported goods must be classified by tariff classification codes and declared through an import declaration to the ACBPS. The questions within the electronic declaration are designed to prompt an importer to enter a permit number for wildlife related goods. If an importer does not provide the permit or permit number to the ACBPS for clearance, the goods will be held pending the provision of a permit, or seized on the basis that they were imported without a permit. Unlike the electronic validation process in ICS for export permits, import permits are manually verified as no such validation function exists in ICS for imported goods. The ACBPS advised that it was unable to report on the number of import permits entered into ICS.

3.25 While changes to species that are regulated are infrequent, Environment has not reviewed the ICS system coding that prompts entry of an export permit number against the Australian Harmonized Export Commodity Classification since March 2011. The ACBPS had, however, reviewed the appropriateness of import tariff classifications (in 2012 and 2014), but the effectiveness of these classifications in detecting wildlife-related goods has not been assessed by either entity. There would be merit in Environment periodically reviewing the export codes used in ICS and the tariff classification codes for imports. This would provide Environment with greater assurance that ICS is appropriately identifying wildlife specimens.

Monitoring of approvals for commercial export

3.26 To commercially export Australian native wildlife specimens (unless exempt50) and/or CITES-listed specimens, proponents must first apply to Environment for approval as a captive breeding program, artificial propagation program, cultivation program, aquaculture program, Wildlife Trade Operation (WTO) or Wildlife Trade Management Plan (WTMP). Of these programs, the following two have associated conditions of approval:

- WTO—approved for a maximum of three years, examples include individuals that collect insect specimens for overseas trade and companies that conduct small scale harvesting of wallabies for skins and meat; and

- WTMP—approved for a maximum of five years, WTMPs are generally large scale industries that have plans developed by the state or territory government entity responsible for managing the particular species, such as state government regulated kangaroo harvesting, saltwater crocodile farming, or native plant harvesting.

3.27 Once approval is granted, the proponent can seek an export permit from Environment. In approving WTO and WTMP applications, Environment does not become responsible for regulating the operation or industry, but must be satisfied that the proposal will not be detrimental to the conservation status of the species and will not threaten ecosystems or the welfare of the species. Environment can place conditions on the approval, the most common of which is providing an annual report on harvest and trade data to the department.

3.28 While the Wildlife Trade Assessments Section is responsible for assessing applications for WTOs and WTMPs, responsibility for monitoring compliance has not been assigned. Further, the department has not developed guidance materials to inform the monitoring of proponent’s compliance with their approvals conditions (such as requesting overdue annual reports or assessing the annual reports received). In the absence of these materials, the Wildlife Trade Assessments Section does conduct limited compliance monitoring activities.

3.29 The ANAO assessed Environment’s compliance monitoring activities associated with WTOs and WTMPs by examining:

- a stratified sample of 10 of the 21 non-commercial fishery51 WTOs approved between 1 July 2011 and 31 December 2014, selected broadly to compare like-industries within WTOs and WTMPs52; and

- all 14 WTMPs approved within the same period.53

3.30 Where annual reports were required as an approval condition, the ANAO assessed whether reports had been provided, the documentation retained by Environment on assessment of these reports, and follow-up of non-compliance (such as non-provision of annual reports). The results of the ANAO’s assessment are summarised in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: ANAO assessment of WTO and WTMP compliance monitoring activities

|

Assessment category |

WTO |

WTMP |

|

Annual reports required (sample size) |

8 (of 10) |

14 (of 14) |

|

1 |

4 |

|

5 |

4 |

|

2 |

0 |

|

2 |

6 |

|

0 |

2 |

Source: ANAO assessment of Environment’s hard copy and electronic files.

3.31 The ANAO’s analysis indicates that there is considerable scope for Environment to improve its practices in relation to the assessment of annual reports. For example, of the nine approvals where an annual report had been provided to the department, documentation to evidence an assessment was retained in two cases. While the four WTMPs with annual reports provided had evidence of an assessment of quota reports54, there was no evidence of assessment of the annual reports for these WTMPs. Despite the absence of evidence to demonstrate that an assessment had been undertaken, the department informed the proponents that their annual reports were compliant.

3.32 Of the eight WTOs and WTMPs where annual reports were overdue, five had multiple annual reports overdue. In one instance of a five year approval, none of the five required annual reports had been provided, with the oldest being five years and nine months overdue. The department had also adopted inconsistent practices between approvals. For example, Environment sent reminder letters to proponents prior to the expiry of three WTOs that requested the provision of overdue annual reports, but in the case of another WTO the proponent was notified after expiry in response to the proponent’s submission of a permit application.55

3.33 Environment has limited recourse when conditions, such as supplying annual reports, are not met—apart from cancelling an approval or permits issued to the proponent. In the absence of internal instructions, a risk assessment or a compliance monitoring strategy to guide staff in relation to the frequency and type of monitoring, Environment has only limited assurance that its monitoring of WTOs and WTMPs is appropriate and ultimately whether activities are being carried out in a sustainable manner.

3.34 To provide assurance that holders of permits, and WTO approvals and WTMP approvals are complying with approval conditions, Environment should develop an approach to monitoring permit holders’ compliance with permit conditions, incorporating relevant permit clearance information from DIBP. Further, the department should incorporate into procedural guidance materials for staff the frequency and type of monitoring required for WTOs and WTMPs, and reinforce to staff the importance of documenting compliance assessments.

3.35 Given that there is limited evidence to indicate that Environment is using annual reports to assess the sustainability of WTO and WTMP programs, it would be prudent for the department to review the merits of this monitoring approach, particularly in light of the Government’s deregulation agenda.56

4. Responding to non-compliance

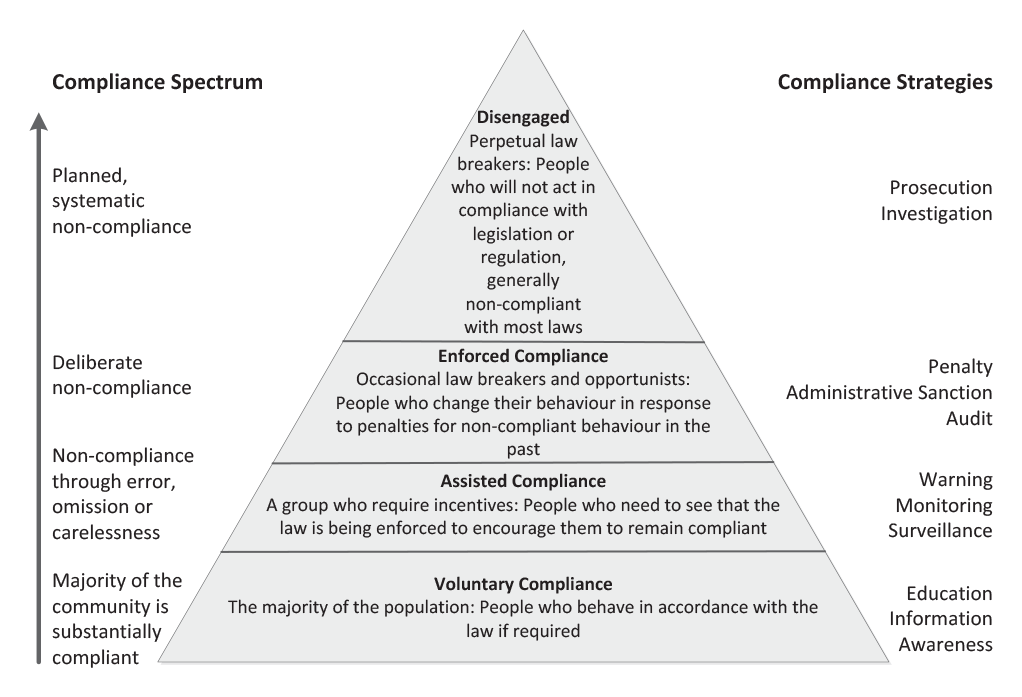

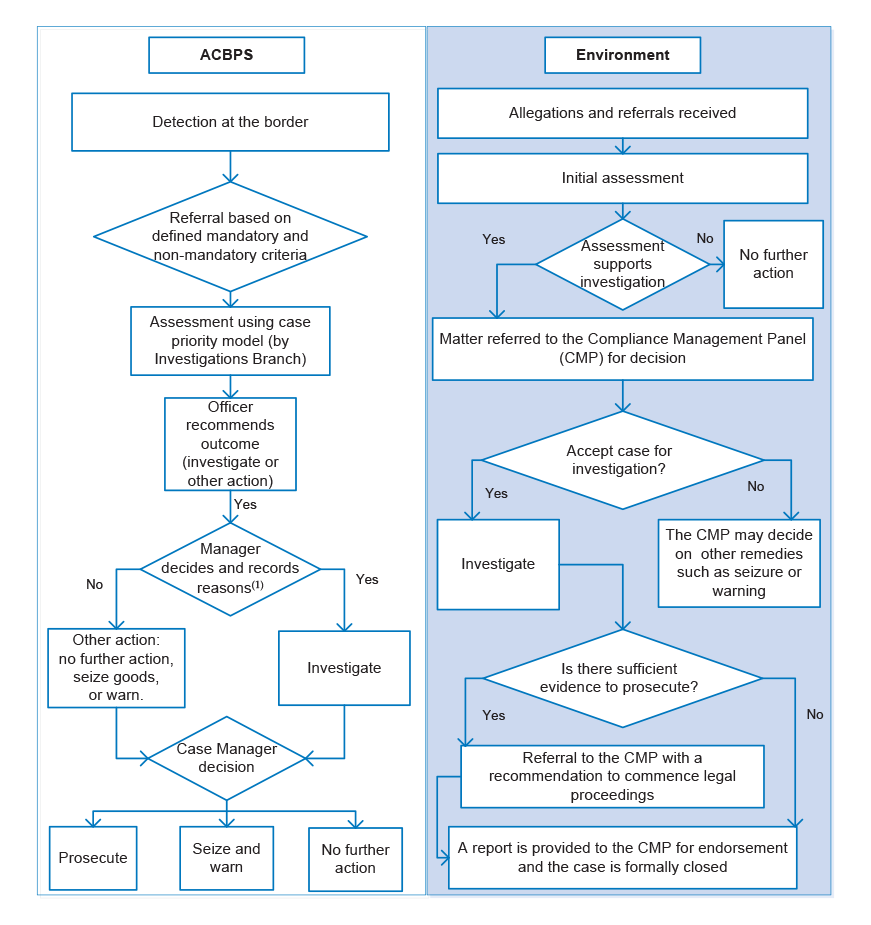

Background