Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Auditor-General’s mid-term report

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The fifteenth Commonwealth Auditor-General of Australia, Grant Hehir, has prepared a mid-term report reflecting on his first five years in the role. The report presents a description and analysis of the role and impact of audit, as well as analysis of the financial audit and performance audit work of the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO). The report concludes with coverage of ANAO continuous improvement activities across audit quality, better communication, transparency, efficiency and workforce capability.

1. Foreword

This report has been prepared so that I could describe and analyse my first five years in the role of the Auditor-General for Australia and from this analysis draw some reflections on the performance of the Australian public sector. The following chapters present description and analysis, while this foreword presents some reflections.

These reflections go to areas where I believe the public sector could become better, however, they should not be seen to infer that Australia does not have a public sector of which in most respects it can be proud. The scepticism of mind and risk-based approach of audit process and selection could lead an avid reader of audit reports to an unwarranted negative view. However, over 50 per cent of performance audits undertaken in the past five years have found entities’ performance to be either fully or largely effective.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) is a critical part of the accountability/integrity framework for the Australian public sector. A key underpinning of this is the independence of the Auditor-General and the ANAO. The importance of independence only became completely clear to me when, after 30 years in the public service, I became an Auditor-General. Although in the public service people talk about being apolitical and providing frank and fearless advice (and I always tried to act that way), what that looks like is, and probably should be, starkly different from the statutory independence of the public sector auditor. The public sector exists to serve the government, the Parliament and citizens. As a public auditor, the ANAO exists to serve the Parliament and citizens. To be effective, public auditors cannot see their future as either individually or organisationally tied to the perceptions of, or reactions to, their work by government. That is why Auditors-General should have fixed terms (preferably non-renewable), have complete discretion over what they audit and how they audit it, have their budgets set by the Parliament with a limited role for government and not be subject to administrative directions by the government.

In my experience the impact of audit on public sector performance is pervasive and positive. It is far more than the publication of a report. The mere existence of audit (both financial and performance) moderates public sector activities to be more consistent with the expectations set out in its legislative and regulatory framework. For example:

- Nowhere is this clearer than in the difference in the assurance that the Parliament can have with respect to audited financial statements versus unaudited non-financial performance statements. Over the past five years the ANAO has published seven audits covering 34 entities in relation to the revised non-financial performance reporting framework established by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). The results of these audits indicate that there is still substantial improvement that needs to be made to entities’ non-financial performance reporting before they can be fully relied on by Parliament. On the other hand, the quality of audited financial statements is consistently high. This is why I strongly support the introduction of mandatory auditing of entity performance statements in a similar manner to which financial statements are audited.

- It is also demonstrated by the regularity with which entities begin reviews of an activity to clean up their systems as soon as a potential performance audit is flagged.

- Published reports play a critical role in the accountability framework, in particular in providing the evidence base for the Parliament to hold the executive government to account.

Audit reports also provide important information for the sector to learn from the successes and failures of others. There are good examples of the public sector operating as a learning system, not least some early evidence in its design of the response to COVID-19, where we have seen how the system has learned from previous failures in dealing with rapid implementation. But there are also too many cases where entities have not learned from the past.1 It concerns me when entities’ responses to audit reports try to publicly diminish the value of the report by suggesting that: a conclusion refers to a minor issue, when under auditing standards a negative conclusion can only relate to a material finding; the entity was already aware of the issue and was dealing with it, when evidence does not support this; or an audit hasn’t appropriately taken account of context, when the entity is really seeking to hide the conclusions in a narrative of excuses. I do not think a learning culture can be nurtured when the leadership of an entity fails to demonstrate that they are willing to confront the facts of performance presented by an audit.

The analysis of evidence from performance audits supports the view that the Australian Public Service has strong capability in relation to policy development, with a statistical correlation between positive audit conclusions and activities related to policy development. Audits related to the design stage of the delivery continuum also have a high proportion of positive conclusions.

On the other hand there is strong evidence, from both performance and financial audits, that the public sector’s approach to procurement regularly falls short of expectations set out in the regulatory frameworks. This is of particular concern given that procurement is a core activity of government and fundamental to the delivery of many of its services. In 2018–19 entities reported contracts with a combined value of $64.5 billion on AusTender. In many cases it is difficult for entities to be able to demonstrate that they have provided value in the use of public resources. It is also particularly concerning that we regularly see entities complying with the letter of the procurement rules but not with their intent. Often the evidence suggests that the decision to exempt procurements from open competition has been based more on it being a less costly and easier process for the entity to undertake, rather than a focus on the overall value of the use of taxpayers’ funds.

Developing capability in procurement, including contract management, should be a priority for public sector leaders.

Regulatory activity is the second category recording a high proportion of negative audit conclusions. Like procurement, regulation is an important function of the Australian Government and high quality regulation (whether of the private, not for profit or public sector) is crucial for the proper functioning of society and the economy. In many cases, audit findings raise issues with respect to the appropriate implementation of risk-based approaches to regulation. Risk-based regulation is important in ensuring that the burden of regulation is appropriate. However, it can only be successful if accountable authorities of entities utilise available evidence to develop a strategic, diligent and risk-based regulatory compliance approach and consistently implement this. Too strong a focus on ‘red tape’ reduction, including through not utilising the full range of regulatory powers provided by the Parliament, can often be at the expense of effective outcomes.

Further effort in improving the implementation of regulation by government entities is required.

Also of concern is that the analysis of both financial and performance audits indicate there is much that needs to be done to improve the delivery of services to Indigenous Australians. Indigenous programs in the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio have the highest proportion of negative conclusions from performance audits of any portfolio, while the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio had the highest number of findings from financial audits, overwhelmingly in Indigenous related entities.

Given the priority successive governments have given to Indigenous policy these findings are disappointing.

That said, the results of ANAO financial audits over the past five years indicate the high quality of financial reporting by Australian Government entities. This is reflected in the fact that only one qualified audit report has been issued over the period and the trend has been for the number of audit findings to decline. Good financial reporting arrangements are one of the key components of quality financial management. The quality of financial reports in the Australian public sector is therefore a positive indicator that financial management in the sector is generally sound.

However, the category which consistently has the most number of financial audit findings raised relates to the information technology control environment, with the most common area relating to weaknesses in security management. These findings are consistent with the conclusions in performance audits of cyber security, which have also consistently identified non-compliance.

With cyber security being an area of government priority for many years, these findings are disappointing.

The public sector operates largely under a self-regulatory approach. Policy owners — for example the Department of Finance for resource management (including procurement and grants); the Attorney-General’s and Home Affairs departments for cyber security; and the Australian Public Service Commission for integrity — establish the rules of operation and then largely leave it to entities’ accountable authorities to be responsible for compliance. There are almost no formal mechanisms in these frameworks to provide assurance on compliance. Often the ANAO is the only source of compliance reporting and our resources mean that coverage is quite limited. While I agree that accountable authorities must be responsible for entities’ compliance, it is also clear that policy owners need to be held accountable if the regulatory frameworks they put in place for the public sector do not result in an acceptable level of compliance. For this to occur, they should at least have processes in place to identify the level of compliance and be willing to modify their regulatory approach if it is not working. Unfortunately, this has not been a common approach.

In many cases where the ANAO identifies weaknesses in public sector’s effectiveness, questions could be raised around the capability, expertise and experience of those involved in the activity. It may be worthwhile reviewing whether the balance between subject matter expertise and generic leadership competencies is appropriately considered when establishing leadership teams.

Over the past five years, I have had a number of key areas of focus in leading the ANAO. In particular these have been:

- audit quality — by increasing transparency of what quality means in the ANAO and how we assess it; greater focus on benchmarking against other audit offices; enhancing external scrutiny through peer-review arrangements with the New Zealand Office of the Auditor-General; and by voluntarily having the Australian Securities and Investments Commission review the ANAO’s financial audit files;

- communication — by focusing on the accessibility and readability of reports along with digital publication; and increasing engagement with ANAO’s international and domestic counterparts;

- coverage of the ANAO’s mandate — by undertaking performance audits of Government Business Enterprises; developing new audit methodologies for performance statements and efficiency audits; and providing a greater range of assurance to the Parliament through assurance reports and information reports;

- transparency of business operations — by making the ANAO’s audit methodology publicly available; publishing information on engagement with the Parliament; providing greater clarity around the audit prioritisation framework; and improving corporate disclosures (such as gifts and benefits);

- efficiency of work performed — by investing in data analytics; a more collaborative work environment; and information technology capabilities; and

- workforce capability.

A challenge that has increasingly faced the ANAO’s performance audit work is how the culture of an organisation is considered during an audit. The performance of an entity cannot always be determined by the extent to which it complies with a particular framework. In many audits, culture comes into the frame in relation to the governance arrangements of organisations. This became most obvious in our audits of cyber security where it quickly became clear that complying with the minimum requirements of the framework (such as the Australian Signals Directorate’s Top Four cyber mitigation strategies) was not a sufficient test for cyber security. The ANAO developed a framework of cyber resilience designed to consider whether entities had developed a cyber security culture. Similar issues exist in other compliance audits, such as in procurement and grants management, where culture is a driver of the proper use of public resources. Compliance with minimum standards is essential, but internal culture drives entity behaviours and affects whether their approach to compliance results in actions consistent with the intended outcomes of a framework.

In this respect, a key area of weakness that I believe still remains in the ANAO’s application of its mandate relates to our work on ethics — the fourth ‘e’ in the definition of proper use and management of public resources in the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. Most audit work we do in the other three areas — effectiveness, economy and efficiency — can draw on performance against clearly defined objectives, frameworks, rules or standards. However, the area of ethical behaviour can be much more nuanced. It is clearly unethical to comply with the letter of a rule, but in a way which undermines its intent. For example, using the provision of ‘extreme urgency brought about by events unforeseen’ to grant an exemption from open competitive tendering, simply because the procurement process was left too late. While ANAO audits have outlined the facts of these situations, I have been reluctant to call out the ethics of this behaviour — after all it may have just been inefficiency or incompetence. However, I think a reluctance on my part to make findings on the ethics of particular actions is unsustainable. On this basis, the development of an audit methodology to assess ethics is a priority for the second half of my term as Auditor-General for Australia.

An important role of the ANAO is to assist the Parliament in holding the executive government to account. It is important to note that the ANAO relies on its audit work to do this. To this end, the ANAO will always let an audit report ‘speak for itself’, rather than providing commentary outside of the audit work undertaken. Submissions and evidence before parliamentary committees are geared towards assisting the Parliament to understand findings and conclusions. I do not see it as the ANAO’s role to do more than this, nor to provide anything other than factual briefings to parliamentarians or the media. Briefings and appearances are important in assisting parliamentarians to understand — in a neutral way — what is required of entities in executing activities and how they have performed in doing so. In similar parliamentary democracies around the world, audit offices provide an advisory function to parliaments in a more systematic way than the ANAO currently does. As Australian Government models of service delivery change to meet community need, this is an area where the ANAO could do more, if the Parliament so desired.

While a number of people in the ANAO provided input into the preparation of this document, I want to particularly acknowledge Sam Painting who provided valuable input into its planning, and Se Eun Lee who was critical in undertaking its analysis and drafting.

Grant Hehir

Auditor-General

2. Role and impact of audit

Summary

2.1 The role of the Auditor-General is to provide independent reporting and assurance to Parliament on whether the executive government is operating in accordance with Parliament’s intent, and within the executive’s own policy and rule framework, to achieve desired objectives. The Auditor-General’s mandate extends to all aspects of Commonwealth entities’ efficiency, effectiveness, economy and ethical behaviour in their use and management of public resources.

2.2 Independence is critical to maintaining trust and confidence in audit work, which in turn is fundamental to the impact of that work. An auditor must be independent, and be seen to be independent, for their opinions, findings, conclusions, judgments and recommendations to be impartial and viewed as impartial by reasonable and informed third parties.

2.3 The statutory independence of the Auditor-General is provided for in the Auditor-General Act 1997. However, the current legislative frameworks within which the ANAO operates also contain several challenges to the Auditor-General’s independence. Most significantly, the executive has the ability to prevent the publication of certain material in Auditor-General reports under section 105D of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and paragraph 37(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act. These provisions have the potential to affect the Parliament’s scrutiny of the executive by limiting the Auditor-General’s independent reporting to Parliament.

2.4 The impact of audit extends beyond the direct impact of audit work, such as the number of audit recommendations agreed to and implemented. The fact that independent external audit exists and the accompanying potential for scrutiny improves performance at both individual program and whole-of-system levels.

2.5 Several times a year, the ANAO also collates key learnings from audit reports in thematic publications called Audit Insights, which further facilitate improvements by communicating important lessons for the public sector to utilise.

Public sector accountability

2.6 The Australian public sector operates under an accountability model that consists of interconnected legal and regulatory frameworks, creating vertical and horizontal accountability relationships between the electorate, the Parliament, the government and public officials.

Figure 2.1: Australian public sector accountability framework

Source: ANAO.

2.7 The executive government is accountable to the Parliament for their performance and operate under a number of key legislative frameworks set by the Parliament, such as the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) which governs the use and management of public resources. Consistent with relevant legislation, the Australian Government develops rules and sets out policy frameworks to be implemented by departments and other agencies. Accountable authorities of each Commonwealth entity may also set in place internal frameworks to instruct officials on certain matters.

2.8 The Australian public sector is expected to operate within these frameworks when carrying out its functions. The maintenance of clear lines of accountability within the public sector is crucial in providing confidence to the Parliament and the Australian public that the public sector is delivering advice and services in a transparent and accountable way, in line with the values of a modern and open democratic society.

Role of the Auditor-General in the accountability framework

2.9 The office of the Auditor-General was the first statutory integrity agency established by the Commonwealth Parliament, following the passage of the Audit Act 1901.2 That Act was the fourth piece of legislation passed by the new Commonwealth Parliament. As such, the functions and role of the Auditor-General are well established in the accountability framework of the Australian public sector.

2.10 The role of the Auditor-General is to provide independent reporting and assurance to Parliament on whether the executive is operating in accordance with Parliament’s intent, and within the executive’s own policy and rule framework, to achieve desired objectives. The two main assurance functions of the Auditor-General are:

- an annual program of mandatory financial statements audits, which ensure the executive’s accountability to the Parliament for the expenditure of public funds; and

- a wide-ranging program of performance audits, which touches on many aspects of government entities’ resource management, governance and performance.

2.11 The Auditor-General’s mandate extends to all aspects of Commonwealth entities’ efficiency, effectiveness, economy and ethical behaviour in their use and management of public resources. Thus, the role and functions of the Auditor-General are critical in facilitating the flow of accountability from the executive government to the Parliament, and ultimately to the broader community.

Importance of audit independence

2.12 Independence is the foundation on which the value of an audit is built.3 Independence requirements for auditors are set out in professional standards and legislation. APES 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants (APES 110) applies to all audits conducted in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards.4 Under APES 110, independence comprises two critical elements:

- independence of mind – the state of mind that permits the expression of a conclusion without being affected by influences that compromise professional judgment, thereby allowing an individual to act with integrity and exercise objectivity and professional scepticism; and

- independence in appearance – the avoidance of facts and circumstances that are so significant a reasonable and informed third party would be likely to conclude, weighing all the specific facts and circumstances, that a firm’s, or a member of the audit team’s, integrity, objectivity or professional scepticism has been compromised.5

2.13 For audits of companies, Divisions 3, 4 and 5 of Part 2M.4 and section 307C of the Corporations Act 2001 apply.

2.14 Independence is critical to maintaining trust and confidence in audit work, which in turn is fundamental to the impact of that work. An auditor must be independent, and be seen to be independent, for their opinions, findings, conclusions, judgments and recommendations to be impartial and viewed as impartial by reasonable and informed third parties.

Auditor-General’s independence

2.15 The statutory independence of the Auditor-General is provided for in the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). Section 8 of the Act establishes the Auditor-General as an independent officer of the Parliament, and provides that the Auditor-General has complete discretion in the performance or exercise of functions or powers. In exercising the mandatory and discretionary functions and powers, the Auditor-General is not subject to direction from anyone in relation to:

- whether or not a particular audit is to be conducted;

- the way in which a particular audit is to be conducted; or

- the priority to be given to any particular matter.6

2.16 There are other legislative provisions that ensure the Auditor-General’s independence. Under section 9 and schedule 1 of the Act, the Auditor-General is appointed by the Governor-General, on the recommendation of the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) and the Prime Minister, for a non-renewable term of 10 years. This reduces the risk that the Auditor-General’s judgment may be impacted by allegiance from appointment or a desire to be reappointed.

2.17 The Auditor-General can only be removed from office by the Governor-General, at the request of both Houses of Parliament, on the grounds of misbehaviour, or physical or mental incapacity.7 This enhances the independence of the office as the Auditor-General will not be inclined to provide positive reports for fear of removal.

2.18 In respect of individual audits, there are two elements that preserve the Auditor-General’s independence. Commonwealth entities can only be audited by the Auditor-General. Auditees are also unable to prevent the commencement or progression of an audit once the Auditor-General determines the audit would be conducted. This strengthens the independence of audit work as entities cannot seek an alternative audit arrangement in the event of adverse findings.

2.19 Section 50 of the Act states that money is to be appropriated by the Parliament for the purposes of the Audit Office. This means that audit fees are ‘paid for’ by the Parliament and not the entities which the ANAO audits,8 reducing the risk that fee negotiations with audited entities can result in a conflict between audit quality and economic self-interest.

2.20 The ANAO is established under section 38 of the Act to assist the Auditor-General in performing the Auditor-General’s functions. Directions to ANAO staff relating to the performance of the Auditor-General’s functions may only be given by the Auditor-General or a member of the staff of the Audit Office authorised to give such directions by the Auditor-General. This prevents staff undertaking the Auditor-General’s functions from being subject to external direction for audit-related functions.

Challenges to the Auditor-General’s independence

2.21 The current legislative frameworks within which the ANAO operates contain several challenges to the Auditor-General’s independence.9 A recent review of public sector auditor independence undertaken by the Australasian Council of Auditors-General (ACAG) found that the ANAO was ranked lower than a number of other ACAG offices on independence.10

2.22 For administrative purposes, the ANAO is an entity within the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio and subject to the Public Service Act 1999. This creates a challenge for the ANAO to accomplish its mandate to provide independent oversight of the Australian Public Service (APS), while fulfilling responsibilities as an entity operating under the requirements of that framework. Further, as members of the APS, the Deputy Auditor-General and ANAO staff are potentially subject to external direction under the framework.

2.23 As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity, the ANAO is subject to policies of the Australian Government that have the potential to impact the Auditor-General’s independence. Whole-of-Government rulings or the ANAO’s inclusion in APS-wide service arrangements or tendering processes could require the ANAO to adopt policies or use services that the ANAO would also need to audit.

2.24 Under section 19 of the PGPA Act, the Auditor-General, as the accountable authority of the ANAO, has a duty to keep the responsible minister and the Finance Minister informed. This means the executive retains the ability to demand reports, documents and information of the ANAO’s activities. There is an inherent risk of conflict because the ANAO’s role is to scrutinise the executive.

2.25 The executive also has the ability to prevent the publication of certain materials in Auditor-General reports. Under section 105D of the PGPA Act, the Finance Minister may use written determinations to require modifications of material that relate to designated activities of intelligence or security agencies or listed law enforcement agencies. Further, paragraph 37(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act provides that the Attorney-General can issue a certificate to the Auditor-General preventing the latter from including particular information in a public report, if the Attorney-General is of the opinion that such disclosure would be contrary to public interest.

2.26 On 28 June 2018, the Attorney-General issued such a certificate, which required the omission of material from the performance audit report Army’s Protected Mobility Vehicle—Light.11 This was the first performance audit tabled by the Auditor-General of Australia with a disclaimer of conclusion.12 The issuance of a section 37 certificate presented one of the most significant challenges to the independence of the office of the Auditor-General in recent times, with the potential to affect the Parliament’s scrutiny of the executive by limiting the Auditor-General’s independent reporting to Parliament. In a subsequent parliamentary inquiry, the JCPAA made a number of recommendations that the Committee proposed be given detailed consideration on the next occasion a section 37 certificate is issued or at the next review of the Act, whichever is the earlier.13

Relationship with the Australian Parliament

2.27 The ANAO’s primary relationship is with the Australian Parliament, particularly the JCPAA. The Public Accounts and Audit Committee Act 1951 provides for the appointment of the Committee and establishes a formal link between the Auditor-General and the Parliament.

2.28 In addition to reports tabled in the Parliament, the ANAO’s assistance to the Parliament occurs through the provision of submissions and information and appearances before parliamentary committees, and briefings to individual parliamentarians. The ANAO publishes on its website briefings provided to parliamentarians and parliamentary committees about audits and related services. Table 2.1 below summarises the number of appearances and submissions to parliamentary committees from 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Table 2.1: Number of appearances and submissions to parliamentary committees

|

Financial year |

Number of appearances and submissions to parliamentary committees |

|

2015–16 |

30 |

|

2016–17 |

39 |

|

2017–18 |

36 |

|

2018–19 |

40 |

|

2019–20 |

47 |

Source: ANAO annual reports 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Responsiveness to Parliamentary recommendations

2.29 In recent years, the JCPAA and other parliamentary committees have expressed interest in the performance of Australian Government entities in relation to implementing audit and parliamentary recommendations.14 Recommendations from parliamentary committees and the ANAO’s performance audits identify risks and shortcomings to the successful delivery of outcomes. Recommendations can specify actions aimed at addressing those risks and identify opportunities for improving entity administration. Tabling an agreed response to a recommendation in the Parliament represents a formal commitment by the government or entity to Parliament to implement the recommended action. The adequate and timely implementation of agreed recommendations is an important element of realising the full benefit of those recommendations, and serves to demonstrate the entity’s commitment to improving public administration.

2.30 Along with follow-up audits examining the implementation of ANAO recommendations15, the ANAO has established a program of work to examine entities’ implementation of recommendations from parliamentary committees. Out of 62 parliamentary committee recommendations examined across eight performance audits tabled in 2015–16 to 2019–20, the ANAO found that 44 recommendations (71 per cent) were fully implemented, 11 (17.7 per cent) were partially implemented and seven (11.3 per cent) were not implemented, at the time of respective audits.

2.31 In November 2019, the ANAO published an edition of Audit Insights outlining the approaches entities are taking to implement recommendations to improve public administration practices and outcomes. The Audit Insight summarised that entities with strong governance structures were more likely to have successfully implemented recommendations. Features of strong governance arrangements included:

- having established processes for responding to recommendations;

- clearly assigning responsibility for implementing recommendations;

- developing implementation plans;

- monitoring and tracking implementation; and

- reporting to and review by the entity’s audit committee on the progress of implementation.

Impact of audit

2.32 The impact of audit can be difficult to assess. What is clear is that impact should not simply be measured by high profile audits like Auditor-General Report No. 12 of 2010-11 Home Insulation Program, or Report No. 23 of 2019–20 Award of Funding under the Community Sport Infrastructure Program, where interest in the issues raised by the ANAO spilled into wider debate in the Parliament and the community. Nor can it be judged only by the direct impact of audit work, such as:

- the number of audit recommendations, or subsequent parliamentary committee recommendations, agreed and implemented; and

- issues identified and rectified by the auditee during an audit. This almost always occurs whether it is a financial audit or a performance audit. The placing of a potential topic on the annual audit work program (AAWP), or the commencement of an audit, often leads to the audited entity undertaking actions to resolve known issues.

2.33 The fact that independent external audit exists, and the accompanying potential for scrutiny, improves performance. One indicator of this is the major difference in quality between the annually audited financial statements and the rarely audited non-financial performance information of entities (now presented in the form of annual performance statements). Australian Government entities largely produce high quality financial statements, which are rarely qualified with few significant audit findings.16 ANAO performance audits which consider non-financial performance information regularly find that they do not meet the relevant, reliable and complete principles17 as set out in the Department of Finance’s guidance.18

2.34 The impact of the ANAO’s ongoing scrutiny can be seen at both the individual program and whole-of-system levels. Several times a year, the ANAO also collates key learnings from audit reports in thematic publications called Audit Insights, which further facilitate improvements by communicating important lessons for the public sector to utilise.

Program improvements

2.35 Program-level improvements usually occur: in anticipation of ANAO audit activity; during an audit engagement as interim findings are made; and/or after the audit has been completed and formal findings are communicated.

In anticipation of audit

2.36 The potential for scrutiny from the ANAO often motivates entities to conduct a review of their own performance. The ANAO’s AAWP plays a key role in driving improvement in the sector before audits formally commence.

2.37 The AAWP development process starts with an environmental scan to develop a comprehensive understanding of: areas of parliamentary interest; changes and trends in the Australian Government sector; and risks to the achievement of government and legislative objectives. This involves extensive analysis across all areas of government service delivery, policy development, and regulatory, compliance and corporate activity. The ANAO also looks at the delivery of large scale investments and procurements, major change programs, areas of significant citizen reliance, and large outflows of government funds.

2.38 Through this process, the ANAO determines areas of audit focus based on portfolio-specific risks and room for improvement identified in prior-year audits and other reviews, as well as emerging sector-wide risks from new investments, reforms or operating environment changes. Entities are consulted on the draft AAWP and invited to provide comments and feedback. This process engages entities in discussions of risk and risk management, and helps both the ANAO and the entities build an informed understanding of material risks within the portfolio.

2.39 As well as early engagement on entity risks, the ANAO flags potential audit topics months in advance by publishing the AAWP for the financial year in early July, outlining the planned audit coverage for the Australian Government sector.19 The AAWP therefore signals to entities that certain programs are considered higher risk by the ANAO and may require closer attention. It is not uncommon for entities to start an internal process to review the program flagged in the AAWP as a potential audit topic. In these cases, by the time an audit commences the entity may have self-identified some of the issues the audit will consider, and begun addressing these issues.

2.40 These review processes can help strengthen the entity’s governance and risk management frameworks by bringing to management’s attention issues and risks that may have been previously unrecognised or unmanaged. The process can also encourage entities to embed regular internal reviews as part of their project management practices.

2.41 Even where the entity has already reviewed the program that will be audited, the ANAO’s independent assurance plays a crucial role in ensuring transparency and accountability. There is a substantial difference between management-initiated internal reviews20 and external audit. In the former, the management sets the terms of reference, controls access to information, potentially influences the methodology applied, and generally does not make the results available publicly. In contrast, an external audit by the ANAO has scope and methodology determined independently, is supported by extensive access powers, is made public through tabling in Parliament and is undertaken to assist Parliament to scrutinise the entity’s performance. In addition to greater transparency through public reporting to Parliament, the benefits of ANAO audit can include the following:

- where a review is ongoing at the time of audit, the ANAO can suggest areas of focus to realise the full benefit of the review process21;

- where the entity is addressing review findings at the time of audit, the ANAO can make suggestions to help strengthen its processes to fully implement the intent of recommendations made22;

- where review recommendations have recently been implemented, the ANAO can provide assurance over the effectiveness of measures taken in response to review findings, such as whether relevant risks have been fully addressed23; and

- ANAO audits can benchmark the entity’s performance against other Commonwealth entities or other jurisdictions, and draw out key lessons for the rest of the sector.24

During audit engagement

2.42 For both financial and performance audits, the ANAO seeks to ensure communication throughout the audit process such that there are ‘no surprises’ in the final audit report.25 This approach provides opportunities for entities to consider the audit findings during the course of the audit. As discussed above, entities will often begin to address issues as they emerge during the audit process. New evidence emerging from these actions is generally taken into consideration in compiling the final audit report.

2.43 Throughout the financial audit process, the ANAO undertakes regular meetings and liaises with the entity to deal promptly with any issues that may emerge. Findings raised during the interim audit phase (reported to Parliament in the Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities) are often addressed by the final audit phase (reported to Parliament in Audits of the Financial Statements of Australian Government Entities), allowing the ANAO to downgrade or close the finding.

2.44 Performance audits also involve close engagement between the ANAO and the audited entity as well as other stakeholders involved in the program or activity being audited. Throughout the audit engagement, the ANAO outlines to the entity the preliminary audit findings, conclusions and potential audit recommendations. This ensures that final recommendations are appropriately targeted and encourages entities to take early remedial action on any identified matters during the course of an audit. Remedial actions entities may take during the audit include:

- strengthening governance arrangements26;

- initiating reviews27; and

- revising and updating policies or guidelines.28

After the completion of audit

2.45 Through the tabling of audit reports, the ANAO reports to the Parliament on areas where improvements can be made to aspects of public administration and makes specific recommendations to assist public sector entities improve performance.

2.46 As outlined above, tabling an agreed response to a recommendation in the Parliament comprises a formal commitment by the government or entity to the Parliament to implement the recommended action. The ANAO conducts follow-up performance audits to examine the implementation of agreed ANAO and parliamentary recommendations.29 The role of parliamentary committees is also crucial in ensuring that entities are addressing the issues identified in the ANAO’s audit reports.

2.47 The JCPAA is required to review all reports that the ANAO tables in the Parliament and to report on the results of its deliberations to both houses of Parliament. The JCPAA tabled 29 reports from its inquiries from 2015–16 to 2019–2030, examining 57 Auditor-General reports. Committee reports may contain recommendations of their own to government or relevant entities, such as to report back to the committee on progress on the implementation of recommendations. This ensures the Parliament maintains scrutiny over key areas of risk.

2.48 For example, Auditor-General Report No. 25 of 2014–15 Administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement examined the effectiveness of the development and administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA). The report found shortcomings in important aspects of the Department of Health’s (Health) administration of the 5CPA, including in: the clarity of the 5CPA and related public reporting; record-keeping; the application of financial framework requirements; risk management; and seeking ministerial approvals. The report also concluded that Health was not in a position to assess the extent to which the agreement had met its key objectives, including achieving $1 billion in expected savings. The ANAO made eight recommendations aimed at improving the overall administration of the 5CPA and informing the development of the next community pharmacy agreement. Health agreed to all eight recommendations.

2.49 In June 2015, the JCPAA selected Report No. 25 for further review and scrutiny at public hearings. In its submission to the inquiry, Health stated that:

The themes and recommendations of the ANAO Report have been reflected in the 6CPA [Sixth Community Pharmacy Agreement], both in terms of the negotiation and agreement finalisation process, and in the 6CPA itself.31

2.50 Health outlined some of the actions taken in response to the ANAO’s recommendations, which included: applying the principle of value for money in the design of 6CPA; appointing a full-time senior probity and risk officer to support the negotiations; and implementing a mandatory requirement for all staff in the Pharmaceutical Benefits Division to undertake record-keeping and risk management training.

2.51 In response to one of the recommendations from JCPAA’s subsequent report32, the ANAO conducted a follow-up audit to examine Health’s implementation of the ANAO’s recommendations from Report No. 25 in the context of the negotiation and implementation of the 6CPA. The audit concluded that as at May 2016, six of the eight recommendations were fully implemented with Health completing the necessary actions in a timely manner. The remaining two recommendations were partially implemented. The audit report also noted that:

The various actions taken by Health in response to the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement audit recommendations have resulted in improved transparency of funding under the Sixth Community Pharmacy Agreement, better recordkeeping and contract management processes, and an enhanced financial and performance reporting framework.33

System improvements

2.52 Through audit and related functions, the ANAO contributes to the development and implementation of whole-of-system reforms that seek to improve the utilisation and management of public resources across the public sector. Key areas of contribution include driving improvements in: public finance; performance; transparency and integrity; and compliance.

Improving public finance

2.53 The ANAO presents two reports to Parliament annually, addressing the outcomes of the financial statements audits of all Australian Government entities and the Consolidated Financial Statements of the Australian Government. The aim of the financial statements audit is to provide independent assurance that the entity’s financial statements are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error, and that they have been prepared in accordance with the government’s financial reporting framework and Australian accounting standards.

2.54 The ANAO’s independent reports support the integrity and transparency of the public sector’s use of resources and provide assurance that the information about Commonwealth entities’ financial performance and position are free from material misstatement and presented fairly. The ANAO’s audit procedures include:

- assessing the effectiveness of management’s internal controls over financial reporting and legal compliance, where the ANAO intends to rely on the controls;

- examining, on a test basis, information to provide evidence supporting the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements; and

- assessing the appropriateness of the accounting policies and disclosures used, and the reasonableness of significant accounting estimates made by the accountable authority.

2.55 The audit procedures also extend to key aspects of legislative compliance, such as requirements relating to the appropriation of monies. The results of relevant performance audits are also considered in determining the auditor’s report on the financial statements.

2.56 The PGPA Act requires each reporting entity to include a copy of the financial statements and the auditor’s report in its annual report. Annual reports inform the Parliament, through the responsible minister, and other stakeholders about the performance of entities and assist the Parliament in its deliberations, including on whether, or at what level, to fund particular programs for delivery by an entity.

2.57 The existence of the ANAO’s mandatory annual financial statements audit program enforces good financial reporting practices. The importance of continuous external scrutiny is emphasised when comparing the overall high quality of financial statements to performance statements. Out of 1236 auditor’s reports issued on entity financial statements for financial years 2014–15 to 2018–1934, only one auditor’s report was qualified35 and 22 contained emphasis of matter paragraphs.36 In comparison, three performance audits and one assurance audit of 14 entities’ performance statements from 2015–16 to 2019–20 have shown that none of the entities have fully met the objectives of performance reporting under the PGPA Act – to provide the Parliament and the public with meaningful information, including by establishing performance measures that are relevant, reliable and complete. An ongoing program of assurance audits of annual performance statements of Commonwealth entities is being piloted.37

2.58 The ANAO’s assurance work also helps entities identify and manage risks to quality financial management. The ANAO directs audit effort to areas most expected to contain risks of material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error, with correspondingly less effort directed at other areas. Risks may arise due to the nature of, or changes in, the entity’s business environment and business and accounting processes, including information technology. Sources of risk include changes in the entity’s functions or objectives, complexity, financial market volatility, global uncertainty, or changes in legislation or the financial reporting framework. The preparation of timely and accurate audited financial statements is an important indicator of the effectiveness of an entity’s financial management, which fosters confidence in the entity on the part of users.

2.59 In its report tabled in Parliament in around December each year, the ANAO analyses the balance sheet positions of material Australian Government entities. The balance sheet lists the entities’ assets and liabilities and is an important measure of its financial position at a point in time. As the National Commission of Audit reported in 2014:

It is the position of the Commonwealth balance sheet which heavily influences credit ratings and borrowing costs and is an important indicator of short term fiscal sustainability and the government’s ability to respond to economic shocks. The balance sheet also reflects the debt that must be repaid by future generations.

A greater focus on the balance sheet position would be beneficial as it would broaden the debate on fiscal policy which can often be fixated on which year a government returns to surplus. For instance, following the global financial crisis, the primary public focus was on whether the Budget would return to surplus while substantial increases in deficits in 2010–11 and 2011–12 which resulted in significant balance sheet deterioration were largely overlooked.

A balance sheet focus would also provide impetus for better asset management. The responsibility for managing assets and liabilities on a day-to-day basis has been devolved to individual agencies. Sound asset management suggests that governments should adequately fund upfront expenditure on assets, but also ongoing capital maintenance and operating costs.38

2.60 All entities are expected to actively manage their underlying financial position, maintain asset levels to support their operations and ensure that sufficient funds will be available to meet liabilities as they fall due. The ANAO’s balance sheet focus assists the Parliament in determining which entities are most likely to require additional funding in the future.

Improving performance

2.61 As well as driving program-level improvements, the ANAO’s audit activities help improve public sector performance on a more systemic level. In certain areas of strong parliamentary interest or high risk, the ANAO undertakes a rolling series of audits to ensure continuing scrutiny of the relevant activities across the sector.

2.62 In recent years, the implementation of the resource management framework introduced by the PGPA Act and related PGPA Rule 2014 has been a focus of ANAO audit work programs. This framework introduced system-wide planning and performance reporting requirements and strengthens the accountabilities of accountable authorities of Commonwealth entities and companies for measuring and reporting on their performance to Parliament. The JCPAA played a key role in the development of the framework and it has continued to be a focus of the Committee’s work.39

2.63 To date, the ANAO has conducted: three audits of corporate planning40; three audits of annual performance statements41; one audit on the clear read across the Commonwealth resource management framework as a whole42; and commenced a program of pilot assurance audits of annual performance statements of Commonwealth entities.43 These audits were identified by the JCPAA as priorities of the Parliament and have found major issues with the appropriateness of performance reporting.

2.64 Appropriate and timely performance information strengthens accountability by informing the Parliament and the government about the impact of public sector entities’ activities relative to government objectives. It also assists entities to manage activities for which they are responsible and provides a basis for advice to government.

2.65 Progress in achieving the improvement in the performance framework over the seven years since its implementation has been disappointing, more so given that the framework built on a previous one that had similar elements and aspirations. The ANAO’s continuing focus in this area is expected to assist in keeping the Parliament, the government, and the public informed on implementation of the framework and to provide insights to entities to encourage improved accountability and transparency of performance.

2.66 Another key requirement under the PGPA Act is the duty of accountable authorities in relation to governing the entity for which they are responsible.44 Governance involves putting appropriate systems and processes in place that shape, enable and oversee the management of an organisation. Reflecting its importance, governance is the most frequently audited activity by the ANAO.45 It was also the subject of a series of audits in 2019 that assessed whether the boards of four corporate Commonwealth entities had established effective arrangements to comply with selected legislative and policy requirements, and adopted practices that support effective governance.46

2.67 Key observations from this audit series were included in an edition of Audit Insights to assist Commonwealth boards and others with an interest in board governance arrangements in Commonwealth entities. The first report in this series also included a recommendation that the Department of Finance update its guidance to accountable authorities on their governance responsibilities, having regard to the key insights and messages for accountable authorities identified in recent inquiries and reviews. Finance agreed to the recommendation.

2.68 Policy development is another area of activity audited by the ANAO which has recently become a focus.47 The public sector plays a key role in the development of public policy, including through providing quality advice to the government. Although the ANAO does not routinely comment on the merits of government policies, audits often examine whether the policy design process was informed by a strong evidence base and sound analysis, and whether the advice provided to government was timely, objective and impartial.48 Audits also comment on the importance of record-keeping. Sufficient records should be created and retained to demonstrate the basis on which key policy design and implementation decisions were taken.49

2.69 The ANAO also conducts continuing programs of audits on major areas of public investment, including in:

- defence capability – for example, the ANAO initiated a series of audits on the Future Submarine program to provide assurance on progress, due to the program’s cost, longevity and risk50;

- large-scale infrastructure such as the National Broadband Network51;

- grants programs52;

- major procurement activities53;

- significant service delivery programs, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS)54;

- programs targeting Indigenous Australians55; and

- the government’s response to COVID-19.56

2.70 As well as ensuring that entities responsible for the delivery of significant government-funded programs are adequately scrutinised and accountable for their performance throughout program implementation, these audits provide recommendations and insights for system-wide improvements.

Improving transparency and integrity

2.71 The ANAO contributes to improved transparency and integrity in the public sector through audit and assurance activities, as well as corporate disclosures.

2.72 It is the role of the Auditor-General to provide independent, accurate and complete information to the Parliament to promote accountability and transparency in the public sector. The annual Major Projects Report (MPR) is a good example of an ANAO assurance activity intended to improve the accountability and transparency of significant government activity for the benefit of Parliament and other stakeholders. The MPR includes a Priority Assurance Review57 undertaken by the ANAO, at the request of the JCPAA, of material prepared by Defence related to major Defence equipment acquisition projects. The projects reviewed in the MPR represent a selection of the most significant projects managed by Defence, with a total approved budget of approximately $64.1 billion in 2018–19. Their high cost and contribution to national security, and the challenges involved in completing them within the specified budget and schedule, and to the required capability, make Defence major projects a subject of continuing parliamentary and public interest.

2.73 The ANAO also raises transparency issues in the public sector from a corporate reporting perspective. In Auditor-General Report No. 33 of 2016–17 Audits of the Financial Statements of Australian Government Entities for the Period Ended 30 June 2016, observations were made about the level of transparency of remuneration for key management personnel in the public sector, noting that the requirements for listed companies under the Corporations Act 2001 provided more detailed disclosures of individual key management personnel remuneration than disclosures of Australian Government entities.58 The report stated that there would be benefit in government considering making the aggregate level of transparency for key management personnel remuneration in the public sector consistent with that required for listed entities.

2.74 In a subsequent inquiry into Report No. 33, the JCPAA recommended in Report 463 that the Department of Finance:

- re-establish a formal requirement for disclosure of senior executive remuneration by Commonwealth entities (including, without limitation, Government Business Enterprises), with this requirement to be duly reflected in the relevant legislation and guidance; and

- ensure that the relevant disclosure is published in entity annual reports.59

2.75 This was followed by a recommendation in the Independent Review into the operation of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Rule to increase disclosures of remuneration paid to executives and highly paid staff.60 In response, the Minister for Finance amended the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 to require Commonwealth entities to make remuneration disclosures for key management personnel, senior executives and other highly paid staff in annual reports. The first additional disclosures were made in entities’ 2018–19 annual reports and were reviewed by the ANAO in Auditor-General Report No. 20 of 2019–20 Audits of the Financial Statements of Australian Government Entities for the Period Ended 30 June 2019.61

2.76 Another area of corporate disclosure the ANAO has influenced is the reporting of gifts and benefits in the public service. The ANAO reviewed entities’ gifts and benefits policies in Auditor-General Report No. 47 of 2017–18 Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities. The ANAO noted that there would be merit in the development of a whole-of-government gifts and benefits policy setting the minimum requirements for entities to include within their policies, to promote good practice across Commonwealth entities.62 A gifts and benefits policy incorporating regular review and monitoring increases accountability, while transparency would be enhanced through the publication of entity gifts and benefits registers on the internet. The maintenance of a central register may assist entities in meeting accountability and transparency obligations.

2.77 In October 2019, the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) produced new guidance relating to gifts and benefits, directing agency heads to:

- create and keep a register of gifts and benefits accepted;

- update their register of all gifts and benefits accepted with a value of more than AU$100.00 (excluding GST), within 28 days of receiving the gift or benefit; and

- publish on their agency’s website the register of gifts and benefits accepted where the value of the gift or benefit exceeds AU$100.00 (excluding GST) on a quarterly basis.

Improving compliance

2.78 The ANAO conducts a number of audits focusing on entities’ compliance with key legislative or policy frameworks in order to ensure continuing observance of mandatory requirements.

2.79 Cyber resilience and compliance with mandatory IT security policies has been a key program of audit in recent years. In addition to IT controls assessment performed as part of the financial statements audit, the ANAO also reviews information systems and related controls as part of its program of performance audits. Since 2013–14, the ANAO has conducted five performance audits to assess the controls over cyber security for 17 different government entities.63

2.80 The first three of these audits assessed both IT general controls and the selected entities’ implementation of the mandatory Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions (commonly known as the Top Four mitigation strategies) in the Australian Government Information Security Manual (ISM)64, which are required by the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF). These controls have been mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities since July 2014. The fourth audit was extended to also review implementation of the four non-mandatory strategies that make up the Essential Eight.65 The fifth audit assessed the effectiveness of the management of cyber security risks by three Government Business Enterprises or corporate Commonwealth entities. A sixth audit on cyber security strategies of nine non-corporate Commonwealth entities to meet mandatory requirements under the PSPF is in progress and due to table in late 2020. The Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities published in May 202066 also considered cyber security in the context of financial report preparation.

2.81 These audits found that compliance with mandatory requirements of information security continued to be low. The 2018 Cyber Resilience audit found that low levels of compliance were driven by entities not adopting a risk-based approach to prioritise improvements to cyber security, and cyber security investments being focused on short-term operational needs rather than long-term strategic objectives. The ANAO has made recommendations aimed at improving the cyber security framework which were agreed by the relevant policy agencies, the implementation of which will be reviewed in the sixth cyber security audit.67 As part of its audit processes, the ANAO developed a list of behaviours and practices that may improve the level of cyber resilience in an entity.68 The ANAO has also prepared an Audit Insights publication on conclusions drawn from its audit work in this area.69

2.82 Other compliance audits include those focusing on whether procurement and grant activities follow the Commonwealth’s procurement and grant frameworks. The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs), issued by the Minister for Finance, contain both mandatory requirements and good practice to assist agencies. While the requirements under these frameworks generally only apply to non-corporate entities, audits indicate that boards of corporate entities regularly include them in their internal frameworks as they represent good practice. Given that most corporate entities are responsible for public resources it is often unclear why these frameworks are not mandated more broadly.

2.83 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the CPRs. To achieve value for money, procurements should:

- encourage competition and be non-discriminatory;

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth;

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision making;

- encourage appropriate engagement with risk; and

- be commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.70

2.84 ANAO audits into procurement have found that entities can generate significant value from having an understanding of the market, the industry providing the goods or services and the product being purchased. Entities that understood their market were better able to scope their service or product needs, were more aware of the options available and could better provide assurance of best value for money being delivered – demonstrating compliance with the CPRs.71

2.85 The ANAO has observed that the introduction of the CGRGs has led to some important improvements in the standard of grants administration. For example, it is now common for program guidelines to be in place and for those guidelines to include clear eligibility and merit assessment criteria. The establishment of the CGRGs has also meant that entities have clear minimum briefing standards they must meet when advising Ministers on the award of grant funding and (through the GrantConnect website) there is a consistent standard of public reporting on the award of grant funding once a funding agreement has been signed.

2.86 Performance audits of grants administration have nevertheless continued to identify significant shortcomings in the design and administration of grants programs. This has most particularly been the case in relation to the processes by which applications for funding have been assessed and funding decisions made.72

Audit Insights

2.87 The ANAO adopts a range of communication practices to strengthen the impact of its work and facilitate the sharing of audit insights. This has included the publication of Better Practice Guides on aspects of Commonwealth administration, for the information of Australian Government entities.

2.88 The 2015 Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation recommended that the ANAO review whether there is a continuing need to develop and maintain separate guidance material, where regulators and policy owners have developed or are developing policy guidance material. This recommendation reflected the risk that entities would treat Better Practice Guides from the ANAO as being the minimum expectation for any subsequent audits. This also posed independence risks as the ANAO would be auditing against the expectations set in its own publication. Following consultation with the Parliament and across government, the ANAO discontinued the publication and distribution of Better Practice Guides from 1 July 2017.73

2.89 There remains, however, an opportunity for the ANAO to share its unique insights into good practice in public administration across the sector. In 2017–18, the ANAO developed Audit Insights, a new product which identifies and discusses common recurring issues, shortcomings and good practice examples, identified through the ANAO’s financial statement and performance audit work. The objective of Audit Insights is consistent with the ANAO’s purpose, to contribute to improved public sector performance.

2.90 To date, there have been 16 editions of Audit Insights, covering a variety of key learnings such as cyber resilience, the effectiveness of governance boards in corporate Commonwealth entities, and the management of conflicts of interest. Recently, Audit Insights have transitioned from summaries of lessons learned from audits tabled over the quarter, towards a more tailored, topic specific selection of themes using source information from a range of relevant audits. This ensures that the ANAO can better target its audience, and that each edition of Audit Insights is a relevant and contemporary product that addresses the emerging risks in the sector.

2.91 The ANAO published an Audit Insights edition on 16 April 2020 that outlines key messages from Auditor-General reports which have examined the rapid implementation of government initiatives. The focus is on key lessons learned from audits of past activities, which are likely to have wider applicability to the APS as it supports the national COVID-19 pandemic response.

3. Performance audit analysis

Summary

3.1 In analysing performance audits carried out over the past five years, those audits which related to the activity of policy development were statistically correlated with positive audit conclusions. In addition, audits related to the design stage of the delivery continuum had the highest proportion of positive conclusions. This provides some evidence to support the view that the Australian Public Service has relatively strong capability in relation to policy development and program design.

3.2 In contrast, the activity of procurement was statistically correlated with negative audit conclusions. This is the case irrespective of the portfolio involved, the objective of the audit or the stage of delivery. This is of particular concern given that procurement is a core activity of government and fundamental to the delivery of many of its services. In 2018–19 entities reported contracts with a combined value of $64.5 billion on AusTender. ANAO audits indicate the need for entities to have a strong focus on improving their capability in procurement.

3.3 Although not determined to be statistically significant, regulatory activity was the second category of activity that had recorded a high proportion of negative audit conclusions. Like procurement, regulation is an important function of the Australian Government and high quality regulation is crucial for the proper functioning of society and the economy. Further effort in this area by government entities is also required.

3.4 Audits of Indigenous programs in the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio have the highest proportion of negative conclusions of any portfolio. Audits in the Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio have the highest proportion of positive conclusions.

3.5 Over the past five years, performance audits have made 618 recommendations aimed at entities improving their performance. It is positive that approximately 90 per cent of these recommendations were fully agreed by entities and that this percentage has been relatively stable across the years. Acting on recommendations is more important than agreeing to them and it is also positive that audits following up on the implementation of agreed recommendations indicate that 96 percent of recommendations had either been implemented or partially implemented at the time of the follow-up audit.

Background

Performance audit

3.6 The ANAO’s performance audit activities involve the independent and objective assessment of all or part of an entity’s operations and administrative support systems. Performance audits may involve multiple entities and examine common aspects of administration or the joint administration of a program or service.

3.7 The Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act) authorises the Auditor-General to conduct performance audits, assurance reviews or audits of the performance measures of Commonwealth entities, Commonwealth companies and their subsidiaries. The Act also authorises the Auditor-General to conduct a performance audit of a Commonwealth partner. Audits of Commonwealth partners that are part of, or controlled by, state or territory governments, must be requested by the responsible minister or the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). Audits of Commonwealth Government Business Enterprises (GBEs) must be requested by the JCPAA. The Act enables the Auditor-General to propose that the JCPAA make such a request.

3.8 Through this activity, the ANAO reports to the Parliament on the performance of executive government and areas where improvements can be made to aspects of public administration, and makes specific recommendations to assist public sector entities to improve performance. The audits can include consideration of:

- economy (minimising cost);

- efficiency (maximising the ratio of outputs to inputs);

- effectiveness (the extent to which intended outcomes were achieved);

- ethics (acquitting responsibilities with integrity, in accordance with the intent of the legislative or policy framework); and

- legislative and policy compliance.

3.9 Performance audit reports are tabled in Parliament as soon as practicable after completion and published on the ANAO website on the day of tabling. Performance audits that are in-progress are listed on the performance audits in-progress page.

About the chapter

3.10 This chapter examines the results of 229 performance audits tabled by the ANAO from 2015–16 to 2019–20. Across these reports, the ANAO made 618 recommendations to audited entities and the Australian Government.

3.11 Through this analysis, the chapter provides an overview of the public sector’s performance over the five years, across various metrics captured through performance audits. The analysis highlights the public sector’s strengths, as well as areas of weaknesses that would benefit from greater focus in future years.

3.12 The first part of the chapter analyses performance of audited entities as determined by the audit conclusion. During the performance audit process, the ANAO gathers and analyses the evidence necessary to draw a conclusion on the audit objective. For the purpose of this analysis, audit conclusions were sorted into four categories:

- unqualified;

- qualified (largely positive);

- qualified (partially positive); and

- adverse.

3.13 An example of these conclusions in the context of an audit examining an entity’s effectiveness would be: fully effective; largely effective; partially effective; and ineffective. In this chapter, ‘unqualified’ and ‘qualified (largely positive)’ conclusions are considered positive conclusions while ‘qualified (partially positive)’ and ‘adverse’ conclusions are deemed negative conclusions.

3.14 These conclusion categories from the 229 performance audits were examined against four variables:

- primary activity being examined;

- portfolio of the audited entity74;

- objective of the audit; and

- stage of delivery of the activity.

3.15 The second part of the chapter examines audited entities’ responses to the recommendations made in performance audit reports, namely:

- the number of recommendations received by portfolio;

- whether an entity has agreed to audit recommendations; and

- whether an entity has implemented agreed recommendations.

3.16 The entities examined in this chapter were grouped in accordance with the ANAO’s 2019–20 annual audit work program (AAWP) portfolio classification. This means, for instance, that the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is analysed separately to the rest of the Treasury portfolio. The analysis also reflects the portfolio structure prior to the machinery of government changes announced in December 2019 and implemented in February 2020.75

Analysis of performance audit conclusions

3.17 Of the 229 performance audits examined, 12.3 per cent were unqualified, 41.5 per cent were qualified (largely positive), 37.4 per cent were qualified (partially positive) and 8.9 per cent were adverse. Given the risk-based approach of audit process and selection, the fact that 53.8 per cent of audit conclusions are largely positive or better could be seen as a positive indicator of the overall effectiveness of the public sector.

Analysis by activity

3.18 To ensure appropriate coverage of portfolio responsibilities, the ANAO considers proposed audit topics against a range of key public administration activities. The activity categories are:

- asset management and sustainment;

- grants administration;

- governance;

- policy development;

- procurement;

- regulatory; and

- service delivery.

3.19 Table 3.1 below shows the breakdown of audit coverage from 2015–16 to 2019–20 by using the major activity category for each audit (many audits relate to more than one activity category). Governance is the most common activity audited (41.9 per cent).76 This is followed by service delivery (20.1 per cent). Policy development is the least common activity the ANAO has audited over the past five years (3.1 per cent).

Table 3.1: Audit coverage across activities, 2015–16 to 2019–20

|

Activity |

Number of audits (%) |

|

Governance |

96 (41.9%) |

|

Service delivery |

46 (20.1%) |

|

Regulatory |

25 (10.9%) |

|

Procurement |

23 (10.0%) |

|

Grants administration |

21 (9.2%) |

|

Asset management and sustainment |

11 (4.8%) |

|

Policy development |

7 (3.1%) |

|

Total |

229 (100%) |

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audit reports published 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Activity by portfolio

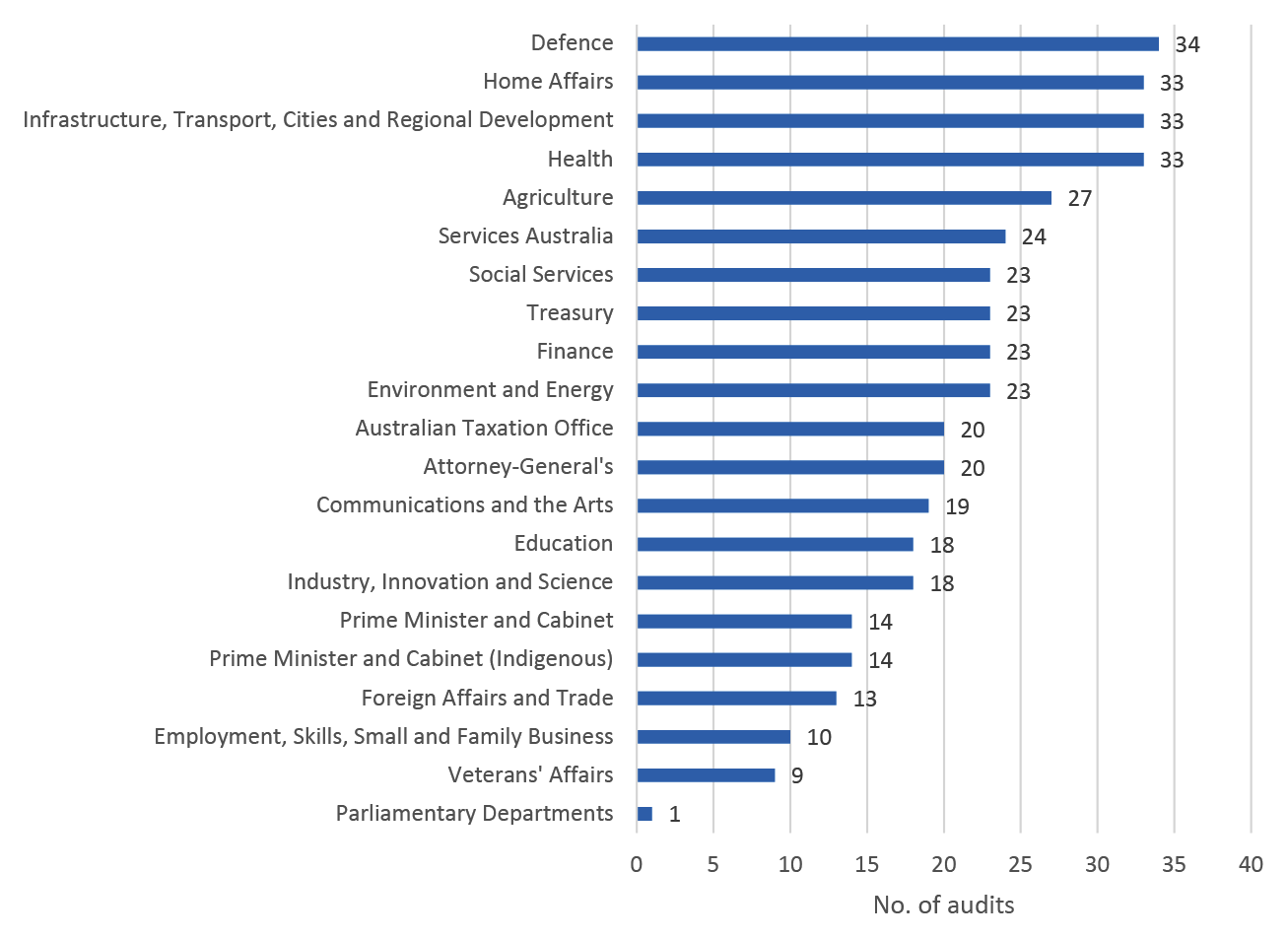

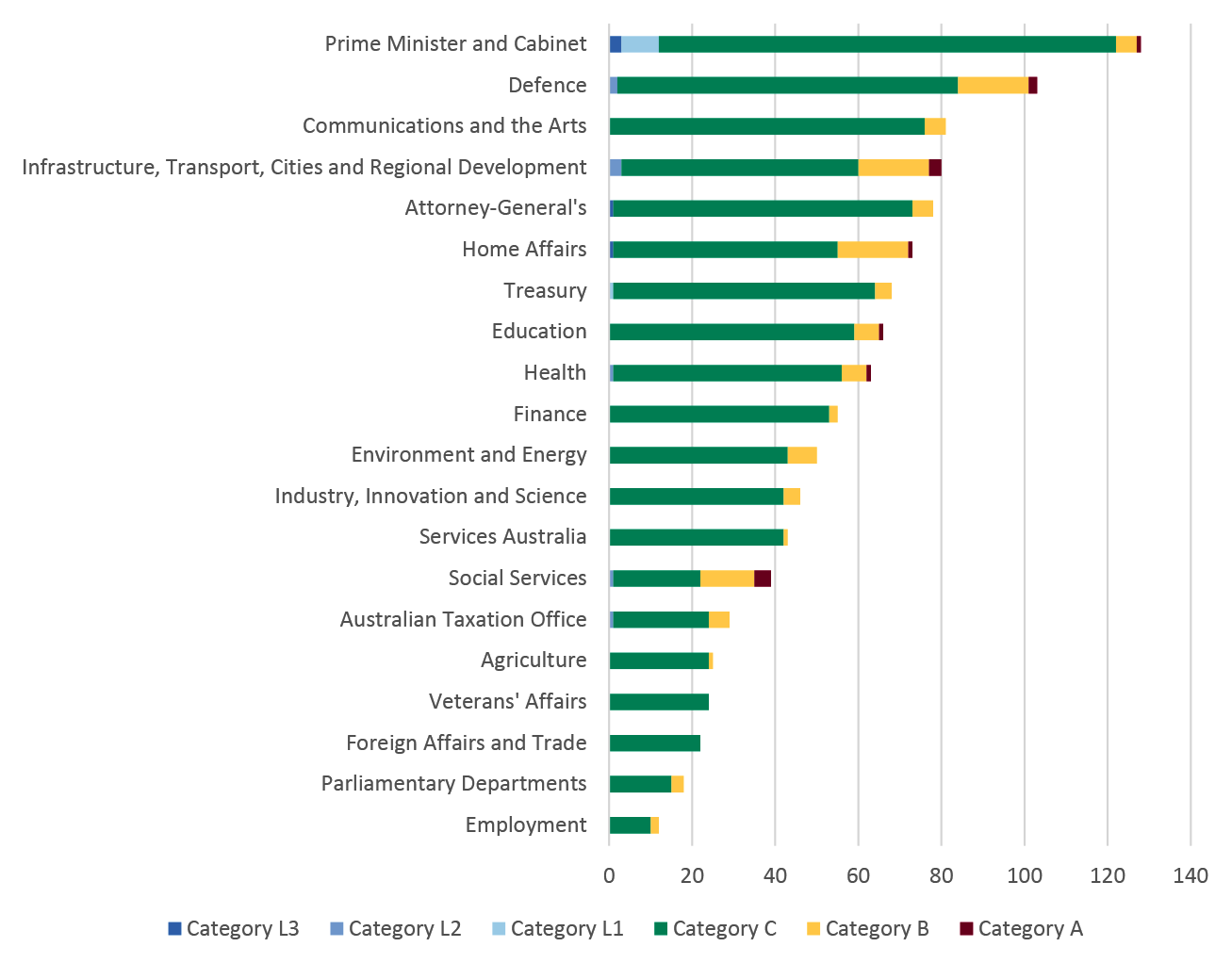

3.20 Figure 3.1 breaks down the audits conducted in each portfolio77 by activity. The spread of audits reflects the distinct roles and responsibilities of each portfolio and their associated risk areas. Governance is critical to all entities and has been the focus of the highest proportion of audits undertaken in every portfolio, with the exception of:

- Services Australia and Social Services, where service delivery is the predominant activity; and

- Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development (Infrastructure), where procurement is the equally dominant activity to governance.

3.21 Only one portfolio, Infrastructure, has not had an audit focused on service delivery activity.

3.22 Asset management and sustainment audits have been conducted in six portfolios: Defence; Veterans’ Affairs; Communications and the Arts; Home Affairs; Industry, Innovation and Science; and Infrastructure. Procurement audits are more common in the Infrastructure, Defence and Finance portfolios, while regulatory activities are more frequently audited in the Treasury, Attorney-General’s, Environment and Energy portfolios, and the ATO.

Figure 3.1: Activity breakdown by portfolio

Note a: The Parliamentary Departments portfolio has been excluded from this analysis, as it was only audited once over the five years (Auditor-General Report No. 19 of 2016–17 Managing Contracts at Parliament House).

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits tabled in 2015–16 to 2019–20.