Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Audits of the Annual Performance Statements of Australian Government Entities — 2021–22

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

This report reflects on the outcome of the first year of implementation of the program of auditing entities’ performance statements.

Executive summary

1. An effective system of measuring and reporting performance is essential if government is to achieve its policy goals in a way that is transparent and accountable. It enables Parliament and the public to hold Australian Government entities accountable for the proper use of public resources and regulatory powers, and for the effectiveness of their service delivery. It allows entities to assess their outcomes and the impact of their programs and services on outcomes. It also supports entities to improve data quality and data analytic and evaluation capability.

2. The Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) establishes an explicit framework for monitoring and evaluating performance. It recognises that financial information, by itself, does not show whether publicly funded programs and activities are achieving their objectives and outcomes.1 It places obligations on accountable authorities for the quality and reliability of performance information and requires Australian Government entities to provide meaningful information to the Parliament. This is an important aspect of the Australian Government’s public accountability system and enables the Parliament and the public to assess whether Australian Government entities deliver the outcomes for which they are funded. Without information on entities’ outcome achievement, the government lacks a sound basis for future investment and policy decisions.2

3. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) has played an active and important role in the implementation of the PGPA Act. The JCPAA has recommended amending the PGPA Act to enable mandatory audits of annual performance statements by the Auditor-General to encourage the provision of high-quality performance information to support parliamentary accountability of entity performance.3 In noting the success of the pilot of performance statements auditing, the JCPAA recommended amending the Auditor-General Act 1997 so that audits of annual performance statements are able to be initiated without the need for approval or direction from the Finance Minister.4

4. This report reflects on the outcome of the first year of implementation of the program of auditing entities’ performance statements.5 The introduction of performance statements audits is the most significant change in Commonwealth public sector auditing in 40 years, since the implementation of performance auditing in the early 1980s. Performance statements audits are an important element of the enhancements to public management and accountability introduced by the PGPA Act and will give the Parliament assurance on an annual basis over the usefulness and reliability of reporting by entities on their performance.

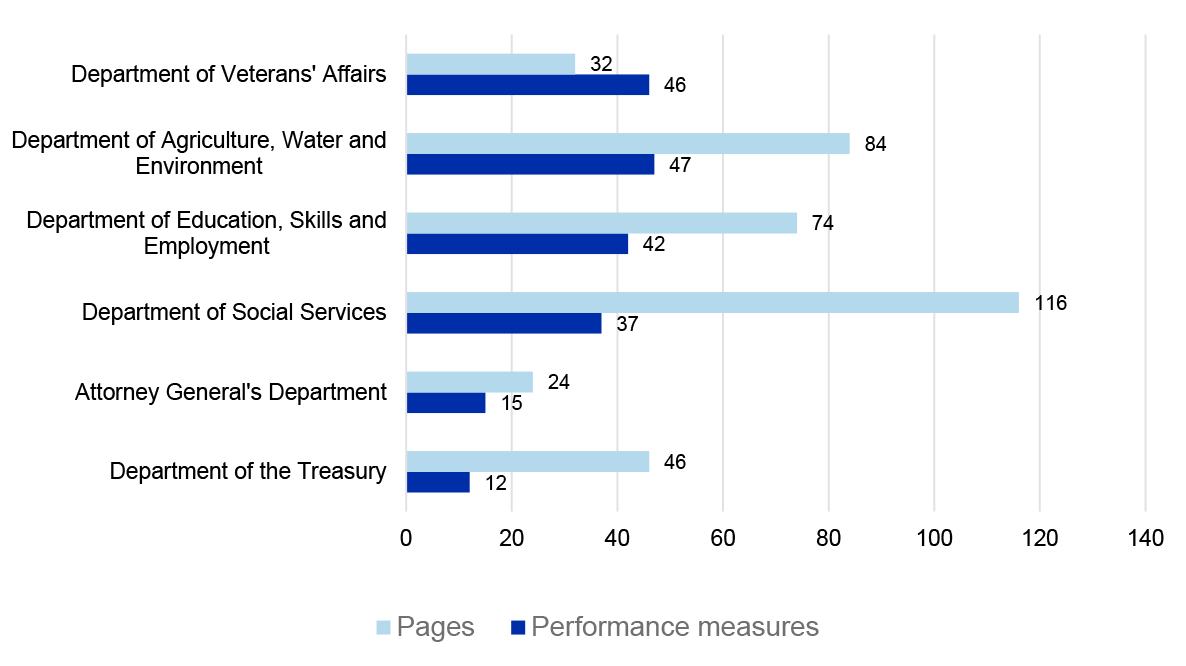

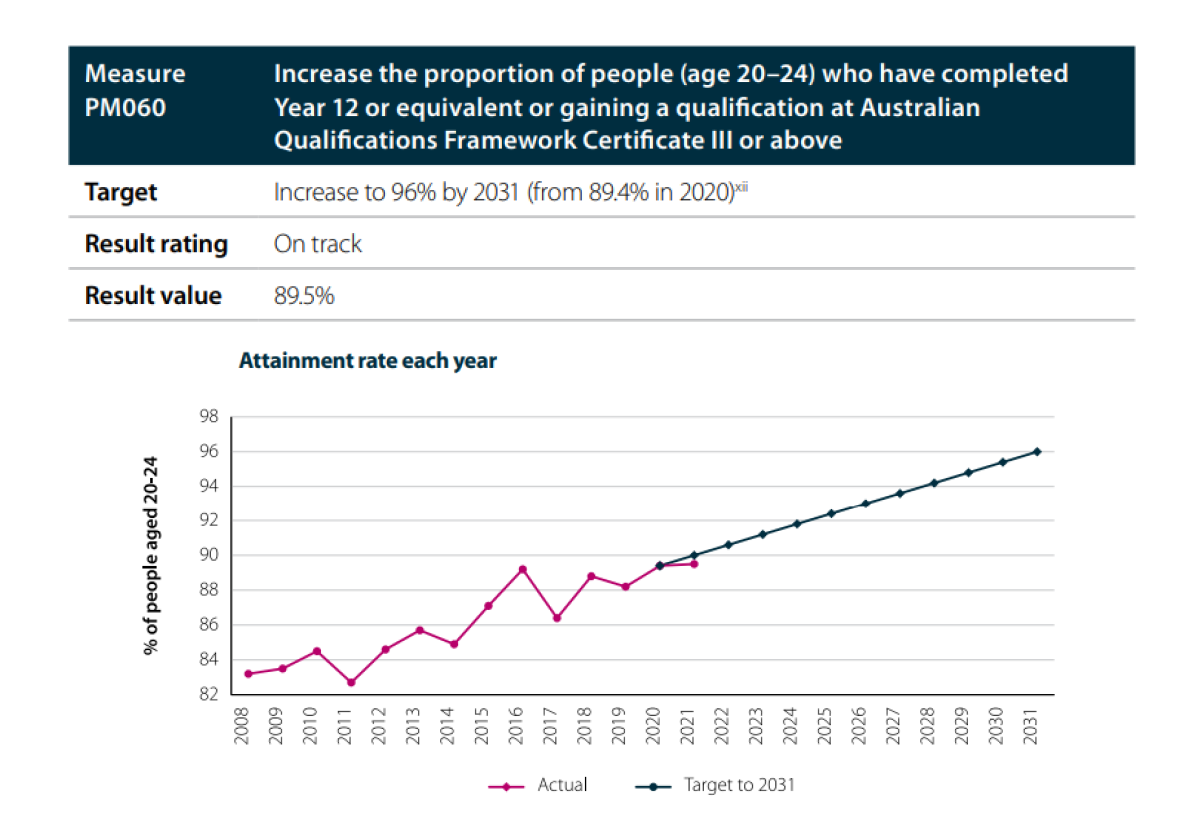

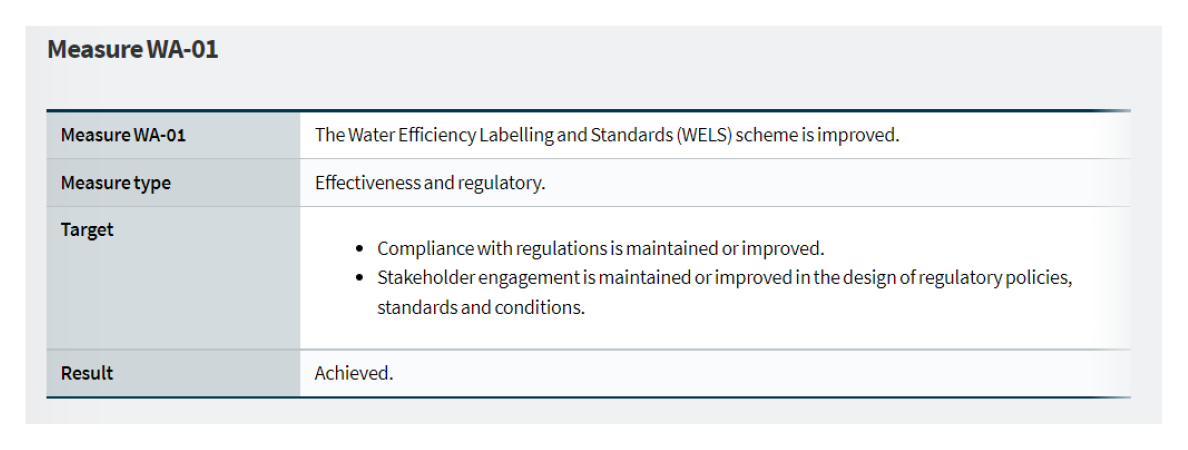

5. Audits were conducted on the 2021–22 performance statements of six entities: the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), the Department of Social Services (DSS), the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE), the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) and the Department of the Treasury (Treasury). These audits have demonstrated that entities are continuing to improve the quality of their performance reporting enabling the Parliament to have confidence in the performance statements.

Commonwealth Performance Reporting

6. The Commonwealth Performance Framework sets out requirements for performance reporting and the preparation of annual performance statements to promote accountability and transparency of entity performance. The Framework consists of the PGPA Act, the accompanying Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) and guidance issued by the Department of Finance (Finance), as the policy owner and standard-setter.

7. Currently, the PGPA Act makes provision for annual performance statements to be examined by the Auditor-General at the request of the Finance Minister or the responsible Minister. This enables the Auditor-General, where a request is received and an audit undertaken, to provide a level of assurance that is comparable to that provided by financial statements audits. The PGPA Act also requires that the requesting Minister table a report by the Auditor-General on an entity’s performance statements in the Parliament as soon as practicable after receipt.6 This is a different process to the tabling of financial statements audit reports, where the auditor’s report is included with the financial statements in an entity’s annual report that is tabled by the responsible Minister in the Parliament.

8. Following recommendations from the JCPAA and the Independent Review of the PGPA Act, and a request from the Minister for Finance in August 2019, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) undertook a pilot of performance statements auditing. During the pilot there was improvement in the standard of performance statements preparation and reporting for each of the audited entities7, demonstrating that audits of annual performance statements can improve the quality and reliability of performance reporting to Parliament.

9. After completion of the pilot, the ANAO was funded as part of the 2021–22 Budget to implement, in a staged way an ongoing program of performance statements audits, from six audits in 2021–2022 increasing to 24 audits from 2025–26. The program of performance statements audits is included in the Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and the ANAO’s Corporate Plan. Implementation of auditing of entities’ annual performance statements provides the Parliament the same level of assurance over the quality and reliability of non-financial performance information that it currently receives for financial information presented in entity financial statements.

Findings from the 2021–22 performance statements audits

10. Chapter 2 of this report presents the findings of the six audits.

11. Across the six audits, entities’ annual performance statements were largely effective in meeting the requirements of the performance framework and accurately reporting the performance of the entity in achieving its purposes. There were, however, some exceptions where entities did not have appropriate preparation processes, methodologies and assurance over the completeness and accuracy of results to support good quality performance reporting.

12. The notable exception was that the ANAO identified that reporting on seven of the ten performance measures in the DAWE performance statements relating to the Agriculture Objective did not meet the requirements of the PGPA Rule. As a result, the DAWE performance statements did not enable the user or reader to form an accurate assessment of the department’s performance in meeting this objective, which is to ‘assist industry to accelerate growth towards a $100 billion agricultural sector by 2030’.

13. In 2021–22, the Auditor-General issued modified audit conclusions for three of the six entities (50 per cent), which compares favourably to 2020–21 where all entities were issued a modified audit conclusion. AGD, DESE and the Treasury each received an unmodified audit opinion. DAWE, DSS and DVA received a modified audit conclusion. Qualifications related to 13 of the 199 performance measures, which represents a reduction from 2020–21 in the proportion of qualified performance measures from 15 per cent to 7 per cent.

The development of entities’ external performance reporting processes

Better practice

14. Chapter 3 identifies areas of better practice in entity performance reporting, demonstrating a progressive maturation in entity processes and practices. Specific areas of note include improvements to:

- performance statements governance and preparation processes, enabling the finalisation of performance statements audits in a timeframe that would enable the audited performance statements to be included in entity annual reports, consistent with the approach for financial statements (paragraphs 3.2–3.6);

- the timeliness and quality of supporting documentation for performance measures, which assists entities to develop appropriate performance measures consistent with the requirements of the Commonwealth Performance Framework (paragraphs 3.7–3.12);

- the structure and quality of performance information in entity performance statements. Entities improved the clarity and alignment of their purposes, key activities and performance measures included in their performance statements (paragraphs 3.13–3.16);

- the use of surveys by entities, where appropriate, to measure and report their performance, including by strengthening survey methodologies and quality assurance processes (paragraphs 3.17–3.22); and

- use of external experts to support performance reporting was generally well planned and documented. The entities used a variety of experts’ measurement and analysis to inform their performance reporting (paragraphs 3.23–3.25).

Areas for improvement

15. Chapter 3 also identifies opportunities for further improvement in entity performance reporting practices to support the production of high-quality, meaningful performance information on a consistent basis. These include:

- entities developing an enterprise level performance framework to integrate performance reporting into a cycle of ongoing planning, monitoring, evaluation and review (paragraphs 3.28–3.32);

- periodic monitoring and reporting of performance results. Processes to periodically monitor and report against performance measures vary across entities, whereas it is an established better practice in relation to financial information (paragraph 3.33–3.41);

- development and reporting of outcome-based performance measures and targets (paragraphs 3.42–3.53); and

- integrating reporting requirements to reduce the reporting burden and improve clarity, establishing the performance statements as the primary vehicle for reporting the performance of Commonwealth entities (paragraphs 3.54–3.60).8

The ANAO’s approach to auditing annual performance statements

16. To date, the ANAO has taken an educative approach to engaging with entities on annual performance statements audits. This approach has assisted in improving the quality of entities’ annual performance statements and the resolution of interim audit findings. It has also provided audit teams with insight into differences and similarities between entity approaches to planning, measuring and reporting their performance.

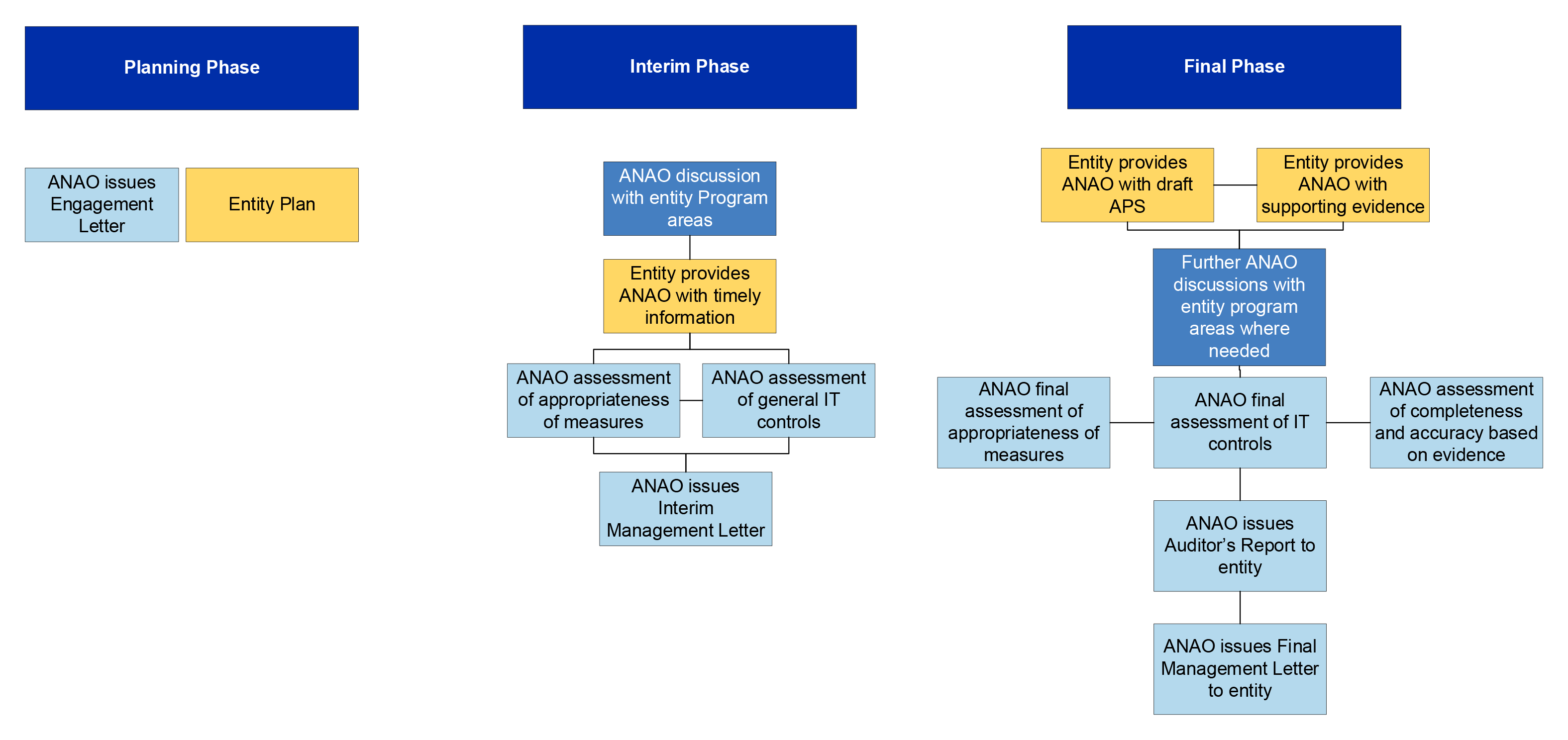

17. Performance statements audits are structured similarly to financial statements audits with a planning, interim and final phase, to allow entities time to correct issues noted and align with annual report tabling. As in financial statements audits, the intent of this structure is to enable the auditee to address matters identified at the interim phase of the audit and to reflect on final findings in the following reporting year.

18. To leverage the benefits of performance statements audits, the ANAO seeks to commence audits as soon as possible in a new financial year. Among other things, early commencement enables the ANAO to work collaboratively with entities to identify opportunities for improvement, which can be reflected in the preparation of the entity’s Corporate Plan and PBS for the next financial year. In the current legislative framework, the timing of a request from the Finance Minister or responsible Minister influences the commencement of auditing.

Future developments

19. The ANAO will continue to refine its audit methodology to ensure it remains fit-for-purpose and encourages entities to improve the quality of their performance reporting. This includes supporting entities to meet both the requirements of the PGPA Rule and the spirit and intent of the Commonwealth Performance Framework. The ANAO has established an Expert Advisory Panel, which will be important to guide maturity of the audit program as it reaches full implementation.

20. During the 2021–22 audit cycle, there was some evidence that entities were taking a compliance-based approach to developing and reporting performance measures to minimise the risk of audit qualification, as opposed to producing complete and meaningful performance information. The ANAO will seek to identify the extent of this practice during the 2022–23 audit cycle and identify how the performance statements audit methodology can better incentivise entities to improve the quality of performance reporting rather than seeking to meet the minimum standards that will satisfy the auditor. The ANAO will provide feedback to Finance on how the Rule is operating following the 2022–23 audit cycle.

1. Commonwealth performance reporting

Chapter coverage

This chapter describes Commonwealth performance reporting requirements and the context and progress of the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) performance statements audit program.

Commonwealth Performance Framework

The Commonwealth Performance Framework sets out requirements for performance reporting and the preparation of annual performance statements to promote accountability and transparency of entity performance. The Framework consists of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), the accompanying Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) and guidance issued by the Department of Finance (Finance), as the policy owner and standard-setter.

Improved performance reporting

Currently, the PGPA Act makes provision for annual performance statements to be examined by the Auditor-General at the request of the Finance Minister or the responsible Minister. This enables the Auditor-General, where a request is received and an audit undertaken, to provide a level of assurance that is comparable to that provided by financial statements audits. The PGPA Act also requires that the requesting Minister table a report by the Auditor-General on an entity’s performance statements in the Parliament as soon as practicable after receipt.a This is a different process to the tabling of financial statements audit reports, where the auditor’s report is included with the financial statements in an entity’s annual report that is tabled by the responsible Minister in the Parliament.

Following recommendations from the JCPAA and the Independent Review of the PGPA Act, and a request from the Minister for Finance in August 2019, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) undertook a pilot of performance statements auditing. During the pilot there was improvement in the standard of performance statements preparation and reporting for each of the audited entitiesb, demonstrating that audits of annual performance statements can improve the quality and reliability of performance reporting to Parliament.

After completion of the pilot, the ANAO was funded as part of the 2021–22 Budget to implement, in a staged way an ongoing program of performance statements audits, from six audits in 2021–2022, increasing to 24 audits from 2025–26. The program of performance statements audits is included in the Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and the ANAO’s Corporate Plan. Implementation of auditing of entities’ annual performance statements provides the Parliament the same level of assurance over the quality and reliability of non-financial performance information that it currently receives for financial information presented in entity financial statements.

Note a: Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, subsection 40(3).

Note b: The Department of Social Services, the Attorney-General’s Department and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs participated in the performance statements pilot.

The Commonwealth Performance Framework

1.1 Performance information shows how effectively the public sector has performed. The intended benefit of performance reporting is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of program delivery, as well as to provide accountability for achieving results that matter to the Parliament and the public. It allows entities to learn from experience, improve program performance and provide strategic, evidence-based policy advice to government. It enables government to allocate limited resources to where they have the most impact.

1.2 The Parliament, through the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), introduced requirements for the preparation of meaningful performance information and annual performance statements that provide accountability and transparency on whether policies and programs are achieving their intended purposes. This recognises that performance of the public sector is more than financial.9

1.3 The Commonwealth Performance Framework (the framework) sets out requirements for performance reporting and the preparation of annual performance statements. It consists of the PGPA Act, the accompanying Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) and guidance issued by the Department of Finance (Finance). (See Appendix 2)

1.4 The framework aims to:

- improve both financial and non-financial performance information by placing obligations on officials for the quality and reliability of performance information — for the Parliament to properly fulfil its oversight function, performance information is crucial to assessing whether policy goals are being achieved10; and

- provide the Australian Parliament and the public with transparent and meaningful information through a combination of financial and non-financial reporting.

1.5 The framework is designed to enable greater parliamentary and public scrutiny and accountability for improved performance. It also assists entities to improve the design and delivery of policies and programs and allocate resources accordingly.

The requirements of the Commonwealth Performance Framework

1.6 The framework requires entities to:

- prepare and publish a corporate plan that sets out the entity’s purposes and key activities and the results it plans to achieve.11 As a statement of planned performance an entity’s corporate plan is closely linked to its Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and annual report12;

- specify performance measures and targets (where reasonably practicable), against which the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes will be measured and assessed13; and

- prepare statements about the annual performance of the entity in achieving its purposes, including analysis of factors that have had a significant impact on the entity’s performance, which are included in the entity’s annual report.

1.7 A key objective of the framework is to establish an integrated performance reporting system to demonstrate to the Parliament and the public that public resources are being used efficiently and effectively by Australian Government entities.14 To this end, the framework aims to improve the ‘line of sight’ between what was intended and what was delivered.15 A reader should be able to identify what was planned to be achieved through the performance measures presented in the PBS and the entity’s corporate plan and the actual results achieved through reporting against the performance measures presented in the entity’s annual performance statements.

1.8 The clear line of sight between an entity’s planning documents and its key reporting document is known as ‘the clear-read’ principle. In its March 2021 guide to preparing the 2021–22 PBS, Finance states:

there must be a clear linkage from the Appropriation Bills to the PB statements, to individual entities’ corporate plan and annual report. Entities should present performance information clearly and consistently (and ensure it is reconcilable) between publications within and across reporting cycles.16

1.9 To achieve a clear line of sight between planned and actual performance, the framework, through a Finance Secretary’s Direction17, establishes requirements for entities to clearly structure their performance information in their PBS and corporate plan.

Portfolio Budget Statements requirements for performance measures

1.10 The requirements for reporting program performance in PBS are set out in a Direction issued by the Finance Secretary under subsection 36(3) of the PGPA Act (the Direction). The Direction sets out the minimum mandatory requirements for performance information to be included in PBS.18

1.11 The Finance Secretary’s Direction issued in December 2021 states that for each existing program, the entity must ‘report at least one high level performance measure and planned performance results, including targets where it is reasonably practicable to set a target’. For new or materially changed programs, the entity is required to report all performance measures and planned performance results, including targets where it is reasonably practicable to set a target.19

Corporate plan requirements for performance measures

1.12 Subsection 16E(2) item 5 of the PGPA Rule requires that the entity’s corporate plan include details of how the entity’s performance will be measured and assessed through ‘specified performance measures for the entity that meet the requirements of section 16EA’ and ‘specified targets for each of those performance measures for which it is reasonably practicable to set a target’.

1.13 Section 16EA of the PGPA Rule states that the performance measures for an entity meet the requirements of this section if, in the context of the entity’s purposes or key activities, they:

- relate directly to one or more of those purposes or key activities; and

- use sources of information and methodologies that are reliable and verifiable; and

- provide an unbiased basis for the measurement and assessment of the entity’s performance; and

- where reasonably practicable, comprise a mix of qualitative and quantitative measures; and

- include measures of the entity’s outputs, efficiency and effectiveness if those things are appropriate measures of the entity’s performance; and

- provide a basis for an assessment of the entity’s performance over time.

1.14 An integral part of the ANAO’s performance statements audit methodology is an assessment of whether the entity’s performance measures meet the requirements of section 16EA of the PGPA Rule, as well as the requirement for targets in subsection 16E(2). These requirements form the test of whether an entity’s performance measures are ‘appropriate’ to measure and assess the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes.

Context of performance statements reporting

1.15 The PGPA Act was enacted to promote high standards of governance, performance and public accountability. The Explanatory Memorandum to the PGPA Bill stated that ‘[I]t was the first time that the importance of performance had been explicitly recognised in Commonwealth legislation.’20 It explained that measuring performance in the public sector is about more than financial reporting and requires adequate and relevant non-financial information.21

1.16 The PGPA Act requires the accountable authority to measure and assess how well the Commonwealth entity has performed in achieving its purposes and prepare annual performance statements, creating equivalent accountability for non-financial information to that for financial information reported in financial statements. In this way, entities report on the money they have used and what they have achieved with that money.

1.17 The requirement for Australian Government entities to prepare annual performance statements under the PGPA Act took effect from 1 July 2015 with entities preparing and reporting annual performance statements for the first time in the 2015–16 reporting period.

1.18 The standards of accountability and transparency that apply to financial statements and performance statements are different due to differences in legislative requirements. For example, the requirement for all Commonwealth entity financial statements to be audited by the Auditor-General is mandated in the Auditor-General Act 1997, whereas the PGPA Act specifies that the conduct of performance statements audits is subject to request from the Finance Minister or the responsible Minister.

1.19 In addition, while the PGPA Act requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to include a copy of the annual performance statements in the entity’s annual report that is tabled in Parliament22, there is no requirement for the accountable authority to include a copy of the auditor’s opinion in the annual report, which is required for financial statements. Rather, the PGPA Act requires the requesting Minister to table a copy of the Auditor-General’s opinion in each House of the Parliament as soon as practicable after receipt. Department of Finance guidance on annual reports (Resource Management Guides 135 and 136) notes that ‘Normally annual reports are tabled on or before 31 October and it is expected annual reports are tabled prior to the October Estimates Hearings. This ensures annual reports are available for scrutiny by the relevant Senate standing committee.’ To support accountability, the ANAO’s timeframe for finalising performance statements audits aims to make the Auditor-General’s opinion available to Parliament in line with the timing for tabling of entity annual reports (noting the audit reports are to be tabled by the Finance Minister or requesting Minister).

1.20 The JCPAA has recommended amending the PGPA Act to enable mandatory audits of annual performance statements by the Auditor-General to encourage the provision of high-quality performance information to support parliamentary accountability of entity performance23 and amending the Auditor-General Act 1997 so that audits of annual performance statements are able to be initiated without the need for approval or direction from the Finance Minister.24 This would ensure similar accountability and transparency requirements for financial and performance statements.

Performance statements audit pilot

1.21 Effective independent assurance is fundamental to good performance reporting and assists in maintaining users’ trust. It provides public organisations, Parliament, and the public with the confidence they need to rely on that reported information.25

1.22 In Report 469, tabled in December 2017, the JCPAA recommended that the government amend the PGPA Act to enable mandatory audits of annual performance statements by the Auditor-General of entities selected by the Auditor-General for review.26

1.23 In September 2018, an Independent Review of the operation of the PGPA Act recommended that:

The Finance Minister, in consultation with the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, should request that the Auditor-General pilot assurance audits of annual performance statements to trial an appropriate methodology for these audits. The Committee should monitor the implementation of the pilot on behalf of the Parliament. (Recommendation 8)27

1.24 In August 2019, the Minister for Finance wrote to the Auditor-General requesting the conduct of a program of pilot assurance audits of annual performance statements of Australian Government entities subject to the PGPA Act, in consultation with the JCPAA.28

1.25 The Auditor-General agreed to the Finance Minister’s request and in 2020 commenced a pilot of performance statements audits, comprising the 2019–20 performance statements of the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), the Department of Social Services (DSS) and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). The same three entities’ 2020–21 annual performance statements were audited in 2020–21 as part of the pilot.

1.26 The pilot demonstrated that accessible and understandable audit conclusions can be issued that clearly set out to the user the extent to which the performance statements can be relied upon to assess the performance of the entity. There was improvement in the standard of performance statements preparation and reporting for each of the audited entities, demonstrating that mandated audits of performance statements can drive more transparent and meaningful performance reporting to the Parliament.

1.27 In the first year of the pilot, the Auditor-General provided his opinions to the Minister for Finance on 2 December 2020. These opinions were tabled by the Minister on 3 February 2021. In the second year of the pilot, the Auditor-General provided his opinions to the Minister for Finance on 9 December 2021. These opinions were tabled by the Minister on 8 April 2022.

1.28 In April 2022, the ANAO tabled its report on the pilot to Parliament.29

Ongoing program of performance statements audits

1.29 Following the first year of the pilot, as part of the 2021–22 Budget, the ANAO was provided funding to support the staged implementation of a program of performance statements audits, from three audits in 2020–21 increasing to six audits in 2021–22, 10 audits in 2022–23, 14 audits in 2023–24, 19 audits in 2024–25 and 24 audits from 2025–26. The 24 audits proposed by 2025–26 were the 15 departments of state (increased to 17 after Machinery of Government changes in July 2022) plus nine controls entities that are material by nature. A review of this scope will determine whether the program should be expanded. Significantly, this funding establishes assurance of non-financial reporting as a core component of assurance to the Parliament.30

1.30 The Auditor-General’s functions include auditing the annual performance statements of Australian Government entities in accordance with the PGPA Act as set out in section 15 of the Auditor-General Act 1997. The ANAO’s role in conducting audits of annual performance statements is currently subject to the request of the Minister for Finance or the responsible Minister for an Australian Government entity rather than initiated by the Auditor-General. The pilot and the six audits undertaken in 2021–22 have been conducted at the request of the Minister for Finance under section 40 of the PGPA Act.31

2022–23 performance statements audit program

1.31 The performance statements audit program will expand in 2022–23 to cover 10 entities.32 Table 1.1 shows the expansion in the number of performance statements audits from 2020–21, which was the last year of the pilot.33 Table 1.1 also shows that implementation of the new program from 2021–22 involves the addition of new entities, to those already subject to audit, in each subsequent year. This approach enables the ANAO to leverage the knowledge and expertise gained from auditing an entity to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the audit, reducing cost and improving processes for both the ANAO and audited entities. This improves the sustainability of the audit program and value for money.

Table 1.1: Entities included in performance statements audit program 2020–2023

|

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

|

The three entities audited in 2020–21 and the following three entities:

|

The six entitiesa audited in 2021–22 and the following four entities:

|

Note a: As a result of Machinery of Government changes that took effect from 1 July 2022, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment became the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and the Department of Education, Skills and Employment became the Department of Education.

1.32 On 25 October 2022, the Auditor-General wrote to the Minister for Finance, proposing to expand the program to 10 performance statements audits in 2022–23 consistent with the funding provided for the program.

1.33 The Auditor-General’s October 2022 correspondence to the Minister referenced the 1 July 2022 Machinery of Government (MOG) changes, proposing to continue the program of work with the six entities audited in 2021–22 and add four new entities; the Department of Health and Aged Care, Services Australia, as well as the newly created Departments of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR) and Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). Many of the programs managed by the new departments were included in the 2021–22 audit cycle in their originating departments. The Minister’s response on 16 January 2023 replaced DEWR and DCCEEW with the Department of Industry, Science and Resources and the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts in the 2022–23 audit program.

1.34 In addition, the Auditor-General asked the Minister for Finance to approve a proposed program of work for 2023–24 and 2024–25. The Minister’s response on 16 January 2023 did not address the proposed work program from 2023–24.

ANAO future areas of audit focus

1.35 To ensure that the quality of performance reporting continues to improve, the 2022–23 performance statements audits will focus on further maturing the ANAO’s auditing approach and building entities’ understanding of performance reporting, including in relation to:

- the application of materiality and completeness in the context of an entity’s performance measures and reported results, to ensure that the performance statements provide a comprehensive and meaningful assessment of an entity’s performance;

- whether the entity’s key activities and performance measures adequately cover the entity’s purposes, to ensure the entity’s performance results align with the purposes;

- performance measures relating to regulation, to ensure these are adequate to report on the entity’s regulatory responsibilities; and

- whether the entity’s performance statements are fair, balanced and understandable, to provide the reader with meaningful information on the entity’s performance.

1.36 Practice across the public sector is still evolving. The ANAO will provide the Parliament with updates on the progress of the performance statements audit program through an annual report. On 22 October 2021, the Finance Minister noted that a JCPAA inquiry to review the audit methods and outcomes each year during the roll-out of the performance statements audit program would inform incremental improvements in the program and inform the design of legislation going forward.34

Performance Statements Expert Advisory Panel

1.37 The ANAO has established a Performance Statements Expert Advisory Panel. The Panel membership includes the ANAO, the Department of Finance, the Department of the Treasury, the Parliamentary Budget Office, a state or territory Auditor-General and several entities’ audit committee chairs.

1.38 The Expert Advisory Panel’s role will include:

- providing advice on how the audit process can contribute to improving performance information and reporting so it assists to:

- improve policy design and evaluation;

- enable more effective service delivery and regulation; and

- provide better advice to inform government decisions;

- providing views on the appropriateness of the current performance statements audit methodology; and

- assisting to improve the ANAO’s understanding of strategic and operational issues, including national and international developments related to non-financial performance information and reporting.

1.39 At the commencement of the performance statements pilot in 2019, a Governance Committee was established to provide advice to the Auditor-General on audit methodology and options to scale the program. The Committee’s contribution was important to the success of the pilot. The Expert Advisory Panel will be important to mature the audit program as it reaches full implementation.

Emerging context for performance reporting and evaluation

1.40 The capacity of the sector to evaluate its policies and programs has received recent prominence in several contexts. For example, Productivity Commission reports have recommended investing in a better evidence base in key policy areas.35

1.41 In October 2022, the Minister for Finance described the government’s intent to coordinate current initiatives to promote evaluation:

Evaluation is also a priority for this Government. It helps us see if we’re actually doing what we said we would. To understand what is working and what isn’t. And being accountable to all Australians. This work has begun. Currently the Department of Finance is implementing the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy and Toolkit. Treasury is scoping how evaluation can help deliver measurable outcomes for Australians. The Office of Best Practice Regulation will support agencies to develop best-practice policy in all areas, not just regulation. We will align these functions and build the evaluation capability to drive service improvements.36

1.42 High-quality performance information is a necessary condition for effective evaluation. Effectively designed performance measures enable an entity to continuously monitor the performance of key activities, obtain regular feedback and collect appropriate data to underpin evaluation activities.

1.43 In turn, evaluation can assist entities to determine whether program objectives have been achieved or if adjustments need to be made, including to the design of key activities, performance measures, data collection and analytic approaches. To realise these benefits, entities will need to consider how best to integrate their evaluation and performance frameworks to form a continual cycle.

1.44 Department of Finance guidance notes that performance measurement and monitoring is used to contribute to an evidence base for future evaluations or review, particularly in helping to develop a program logic.37 In this context, performance statements audits can contribute by assisting entities to build a robust evidence base, monitor progress and strengthen data analytic capability to improve their capacity to evaluate their policies and programs.

1.45 Reliable and verifiable information sources and measurement methods, which is a key area of focus for audits, will drive improvement in the quality of data collected and used by entities, strengthening the evidence base for performance reporting, and policy and program evaluation. Information sources and methods that are not reliable and verifiable can compromise data integrity, which adversely impacts the accuracy and quality of evaluation and policy advice to inform government decisions.

1.46 Performance statements audits have shown that the quality of data and data analysis across entities is variable. Strengthening these capabilities will enable entities to generate deeper insights, provide better advice to inform government decisions, and enable more effective service delivery and regulation to improve social and economic outcomes.38

1.47 A key challenge for entities is to determine which data are needed and worth collecting, including data that may take several years to mature. Entities need to also recognise that what is seen as key today may change over time. Therefore, performance information requirements may need to evolve over time if they are to remain relevant.

Structure of the report

1.48 This report presents the findings of the 2021–22 annual performance statements audits (chapter 2), the areas of better practice and those for improvement (chapter 3), and the ANAO’s approach to performance statements audits (chapter 4).

2. Findings from the 2021–22 performance statements audits

Chapter coverage

This chapter provides the key findings of the 2021–22 annual performance statements audits and details the bases for the modified audit conclusions over entity performance statements.

Key findings

Across the six 2021–22 audits, entities’ annual performance statements were largely effective in meeting the requirements of the performance framework and accurately reporting the performance of the entity in achieving its purposes. There were, however, some exceptions where entities did not have appropriate measures or adequate processes to support good quality performance reporting.

The notable exception was that the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) identified that reporting on seven of the ten performance measures in the Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment’s (DAWE) performance statements relating to the Agriculture Objective did not meet the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule). As a result, the DAWE performance statements did not enable the user or reader to form an accurate assessment of the department’s performance to meet this objective, which is to ‘assist industry to accelerate growth towards a $100 billion agricultural sector by 2030’.

In 2021–22, the Auditor-General issued modified audit conclusions for three out six entities (50 per cent), which compares favourably to 2020–21 where all entities were issued a modified audit conclusion. AGD, DESE and the Treasury each received an unmodified audit opinion. DAWE, DSS and DVA received a modified audit conclusion. Qualifications related to 13 out of 199 performance measures, which represents a reduction from 2020–21 in the proportion of qualified performance measures from 15 per cent to 7 per cent.

2.1 ANAO’s performance statements audits improve transparency and provide Parliament with assurance over the quality and reliability of entities’ annual performance statements. They are also designed to identify areas where improvements can be made across the sector by presenting specific findings and recommendations to audited entities.

2.2 Findings and recommendations are communicated to entities at several stages during the audit to enable entities to address identified issues prior to finalising their performance statements for the reporting period. Where findings remain unresolved, these can be addressed by entities in the following year.

2021–22 performance statements audits

2.3 The ANAO conducted six performance statements audits in 2021–2022 of the following entities: the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), the Department of Social Services (DSS), the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE), the Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) and the Department of the Treasury (Treasury). (Appendix 1)

2.4 The Auditor-General provided his audit opinions to the Minister for Finance on 25 October 2022. The Minister tabled these opinions in the Senate on 16 December 2022. The Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires that the Minister requesting an audit of an entity’s annual performance statements must table a copy of the Auditor-General’s report in each House of Parliament as soon as practicable after receipt.39

2.5 The audits demonstrate how entities can establish sound practices and improve the standard of their performance reporting processes and their performance information over the reporting period.

2.6 The 2021–22 audits demonstrate that first year auditees can be issued with an unqualified audit opinion. DESE and Treasury each received an unqualified audit opinion, recognising the investment of these entities in developing robust governance arrangements and preparation processes.

2.7 The 2021–22 audits also showed that ‘repeat’ auditees can address matters that were a basis for qualification from the previous year. AGD, DSS and DVA each addressed matters contained in their 2020–21 auditor’s reports. These outcomes reflect early planning and a considered approach to resolving audit findings.

Key findings

2.8 Audit findings are raised in response to the identification of potential risks to an entity’s performance statements preparation, including where performance measures do not adequately measure the entity’s performance and prior year findings that have not been satisfactorily addressed. The rating scale for findings for the 2021–22 audit program is presented in Appendix 5.

2.9 Across the six 2021–22 audits, entities’ annual performance statements were largely effective in meeting the requirements of the performance framework and accurately reporting the performance of the entity in achieving its purposes. In particular, the results reported against the performance measures in the annual performance statements and accompanying supporting analysis were generally accurate and supported by appropriate records. There were, however, some exceptions where entities did not have appropriate measures or adequate processes to support performance reporting.

2.10 A total of 31 findings were reported to entities as a result of the 2021–22 performance statements audits. These comprised 10 significant, 11 moderate, and 10 minor findings. Appendix 4 presents these findings against 19 themes.

- The theme with the highest number (14) of significant and moderate findings related to the use of reliable and verifiable methodologies and data sources to support the reported results of individual performance measures. This included methodologies supporting the calculation of results not being sufficiently robust and data sources that were not reliable and verifiable.

- There were two significant audit findings relating to performance measures that did not provide an unbiased basis for measurement and assessment.

- There were two significant and two moderate findings relating to an entity’s inability to provide assurance over the completeness and accuracy of results.

- There was one significant and two moderate findings relating to poor recording keeping processes including inadequate oversight by management.

2.11 Table 2.1 summarises significant and moderate audit findings by theme presented to entities in 2021–22.

Table 2.1: Significant and moderate audit findings by theme

|

|

Disclosure and presentation |

Preparation processes including record keeping |

Methodology |

Completeness and Accuracy |

|

Attorney-General’s Department |

|

✘ |

|

|

|

Department of Social Services |

|

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

|

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Department of Education, Skills and Employment |

|

|

✘ |

✘ |

|

Department of the Treasury |

|

✘ |

✘ |

|

Key: ✘ indicates where an entity has received either a significant or moderate finding relevant to this theme.

Notes: Appendix 4 expands on this table by identifying sub-themes that relate to specific audit findings.

Appendix 4 contains the theme ‘Construct of Measure’, which is not included in this table as there were no significant or moderate audit findings relating to this theme.

Source: ANAO compilation of findings.

2.12 Table 2.2 summarises findings by category presented to entities in 2021–22. Of the ‘repeat’ entities audited in 2021–22, the ANAO observed that the number of audit findings reduced from 20 findings in 2020–21 to 10 findings in 2021–22.

Table 2.2: Performance statements audit findings by category

|

Category |

Closing position (2020–21) |

New findings (2021–22) |

Resolved findings (2021–22) |

Closing position (2021–22) |

|

Entities in the 2020–21 pilot |

||||

|

A — significant |

4 |

2 |

(4) |

2 |

|

B — moderatea |

6 |

2 |

(4) |

4 |

|

C — minorb |

10 |

2 |

(8) |

4 |

|

Subtotal |

20 |

6 |

(16) |

10 |

|

Newly audited entities |

||||

|

A — significant |

N/A |

11 |

(3) |

8 |

|

B — moderatec |

N/A |

10 |

(3) |

7 |

|

C — minor |

N/A |

13 |

(7) |

6 |

|

Subtotal |

0 |

34 |

(13) |

21 |

|

All audited entities |

||||

|

A — significant |

4 |

13 |

(7) |

10 |

|

B — moderate |

6 |

12 |

(7) |

11 |

|

C — minor |

10 |

15 |

(15) |

10 |

|

Total |

20 |

40 |

(29) |

31 |

Note a: One category B finding was downgraded to a category C finding during the interim audit phase.

Note b: One category B finding was downgraded to a category C finding during the final audit phase.

Note c: One category C finding was upgraded to a category B finding during the final audit phase.

Note d: One category B finding was upgraded to a category A finding during the final audit phase.

Source: ANAO compilation of findings.

2.13 Importantly, the ANAO observed that entities sought to resolve findings reported at the close of 2020–21, and findings identified during the reporting period, where possible. Entities resolved 29 findings during the year, with 31 remaining open at year end. The ANAO has actively worked with entities to support the resolution of findings to ensure that annual performance statements present accurate and meaningful performance information.

2.14 The ANAO also observed improvement in the resolution of findings from interim to final audit phases. Of the 35 unresolved interim audit findings, 23 (66 per cent) were resolved by the end of the year.

2.15 Figure 2.1 below shows the number of unresolved findings at the conclusion of each audit phase for the six audited entities. The figure shows a reduction in the number of findings by the 2020–21 pilot entities.

Figure 2.1: Findings by audit phase

Source: ANAO compilation of findings.

Bases for qualification

2.16 Performance statements audits are conducted under the ANAO auditing standards that adopt the Australian Standard ASAE 3000: Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information issued by the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. Under this standard, the auditor can issue an unmodified or a modified conclusion. An auditor’s conclusion may be ‘modified’ in one of three ways:

- A ‘qualified conclusion’ may be expressed when the auditor, having obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence, concludes that the performance statements as a whole are largely compliant with the PGPA Act or the PGPA Rule, but there are matters of non-compliance that, individually or in aggregate, are material but not pervasive to the performance statements. This could include where the auditor is unable to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence for specific performance measures, which, while material, is not pervasive to the performance statements. A qualified conclusion may also be referred to as an ‘except for’ qualification, as the qualification does not apply to the annual performance statements as a whole, but to specific measures reported in the statements.

- A ‘disclaimer of conclusion’ is expressed when the auditor, having been unable to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence on which to base the conclusion, determines that the possible effects on the [performance] statements of undetected non-compliance could be both material and pervasive.

- An ‘adverse conclusion’ is expressed when the auditor, having obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence, determines that matters of non-compliance, individually or in aggregate, are both material and pervasive to the [performance] statements.40

2.17 For the six 2021–22 performance statements audits, AGD, DESE and Treasury were issued an unmodified conclusion and DAWE, DSS and DVA were issued a modified conclusion, in the form of an ‘except for’ qualification. This is an improvement from 2020–21 where AGD, DSS and DVA audits were issued a modified conclusion. Two of the entities that were not part of the pilot and were audited for the first time, DESE and Treasury, received an unmodified conclusion.

2.18 Table 2.3 summarises the number of measures forming the basis of qualification across all six entities. This table shows that the three entities that received a modified audit conclusion in 2020–21 resolved all or the majority of these issues in their 2021–22 performance statements.

Table 2.3: Number of measures forming the basis of qualification

|

Entity |

Closing position (2020–21) |

Identified in 2021–22 |

Resolved in 2021–22 |

Closing position (2021–22) |

|

Entities included 2020–21 pilot |

||||

|

Attorney-General’s Department |

6 |

0 |

(6) |

0 |

|

Department of Social Services |

8 |

0 |

(7) |

1 |

|

Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

2 |

2 |

(2) |

2 |

|

Subtotal |

16 |

2 |

(15) |

3 |

|

Newly audited entities in 2021–22 |

||||

|

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

N/A |

10 |

0 |

10 |

|

Department of Education, Skills and Employment |

N/A |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Department of the Treasury |

N/A |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Subtotal |

0 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

|

Total |

16 |

12 |

(15) |

13 |

Source: ANAO 2020–21 and 2021–22 audit results.

2.19 Where appropriate, an auditor’s report may include an ‘Emphasis of Matter’ paragraph. The inclusion of this paragraph does not modify the auditor’s opinion.

2.20 Most commonly, an ‘Emphasis of Matter’ paragraph is a tool available to auditors to highlight important information. Such a paragraph is included in the auditor’s report when it is considered necessary to draw to the reader’s attention to a matter presented in the performance statements that, in the auditor’s judgement, is of such importance that it is fundamental to the users’ understanding of the performance statements. There was one Emphasis of Matter in 2021–22 in the audit report on DSS’ performance statements.

2021–22 modified audit conclusions

2.21 The ANAO’s conclusion on three of the six 2021–22 performance statements audits was an ‘except for’ qualification, which is described as follows in the auditor’s reports:

In my opinion, except for the effects and possible effects of the matters described in the Bases for Qualified Conclusion section of my report, the attached 2021–22 Annual Performance Statements of the Entity are prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with the requirements of Division 3 of Part 2-3 of the Public, Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the Act).

2.22 Table 2.4 and Table 2.5 summarise the audit conclusions for all six audited entities. Of the three entities that were audited for the first time in 2021–22, DAWE had an ‘except for’ qualification, with DESE and Treasury receiving unmodified audit conclusions. The ANAO issued modified audit conclusions for DVA and DSS in both 2020–21 and 2021–22.

Table 2.4: Summary of audit conclusions

|

Reporting year |

Number of audited entities |

Number of ‘except for’ qualifications |

Number of unmodified audit conclusions |

|

2021–22 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

|

2020–21 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

Source: ANAO 2021–22 and 2020–21 audit results.

Table 2.5: Summary of qualified measures as a proportion of total measures

|

|

AGD |

DSS |

DVA |

DAWE |

DESE |

Treasury |

|

Number of measures |

15 |

37 |

46 |

47 |

42 |

12 |

|

Number of qualified measures |

0 |

1 |

2 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

Note: Across the six entities’ performance statements, there are 199 performance measures underpinned by 238 targets.

Source: ANAO 2021–22 audit results.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment

2.23 DAWE’s 2021–22 performance statements reported on 47 performance measures underpinned by 51 targets. The auditor’s report on DAWE’s annual performance statements was qualified with respect to 10 of the 47 performance measures.41

Qualifications

2.24 The ANAO identified that reporting on seven of the ten performance measures relating to the Agriculture Objective did not meet the requirements of the PGPA Rule. As a result, the performance statements did not enable the user to form an accurate assessment of the department’s performance to meet this objective, which is to ‘assist industry to accelerate growth towards a $100 billion agricultural sector by 2030’.

2.25 The reasons underpinning the modified audit conclusion for the seven performance measures that were qualified are described below.

Progress on the Commonwealth’s obligations under the National Drought Agreement (AG-03)

2.26 Performance measure AG-03 reports on the progress of the Commonwealth’s obligations under the National Drought Agreement. The department is the lead Commonwealth agency where each jurisdiction self-assesses its progress against ratings. There was no supporting material for these assessments and no validation of the reported results for the ANAO to assess. Consequently, the requirements for performance measures to be based on a verifiable methodology and information sources and to provide an unbiased basis for measurement and assessment were not satisfied.42

2.27 In addition, this performance measure does not meet the requirement of subsection 16F(1) of the PGPA Rule to measure and assess the achievement of the entity’s purposes in the reporting period. The result is based on 2020–21 self-assessments and does not report on performance in the 2021–22 reporting period.

Performance measures on market access and regulatory costs (AG-04, AG-05, AG-06, AG-07, AG-08)

2.28 The five measures relate to the department’s role in supporting market access, protection and sustainment. The five measures did not meet the requirement of subsection 16EA(b) of the PGPA Rule for using sources of information and methodologies that are reliable and verifiable.

2.29 Performance measures AG-04 and AG-05 report on the department’s ‘market access achievements’. The measures relate to actions taken by the department that results in access to a new international market, improved access to an existing market, prevention of disruptions to trade with an existing market and restoration of market access.

2.30 The methodology for AG-04 and AG-05:

- relies on verbal advice to support industry value estimates. These estimates then form the basis from which to calculate an estimate of potential trade achieved from a ‘market access achievement’. No documentation was provided to verify this verbal advice. While in some cases the department has overridden these industry value estimates, there is no internal guidance or procedure to support these decisions; and

- excludes lost market access and foregone opportunities which means the reader does not have an unbiased basis with which to assess market access achievements.

2.31 Performance measure AG-06 relates to the department’s role in managing point of entry failures. The ANAO identified that the department does not have reliable or verifiable sources of information and methodologies for recording and reporting point of entry failures.

2.32 The audit found that the department’s ‘distressed consignment’ tracking sheet did not record some point of entry failures, with the department stating that ‘missing entries may be the result of administrative error by staff’. The department has also stated that 16 point of entry failures that were recorded in the tracking sheet should not have been included ‘due to the scope of definition of POE failure’.

2.33 Transparency for this measure could also be improved by reporting the number of point of entry failures in addition to the percentage of all consignments, as the percentage might fall while the number of failures rises. This would more accurately reflect a key objective of the Export Controls Act 2020 which is to ensure that (all) exported goods meet relevant importing country requirements.

2.34 Performance measure AG-07 relates to the reductions in the department’s regulatory costs for agricultural exporters.

2.35 The measure claims savings to the department from staff reductions; principally, the reduced number of Food Safety Meat Assessors (FSMAs) employed by the department, which must then be provided by exporters. The methodology is not a reliable basis for measuring and assessing the ‘reduction of $21.4 million in the department’s regulatory costs for agricultural exporters by 2024’. The methodology does not capture ‘cost recovery expense’, as per the target.

2.36 Performance measure AG-08 relates to reductions in compliance costs for agricultural exporters.

2.37 The ANAO identified that the department does not have a robust methodology for calculating compliance costs for agricultural exporters. It has not substantiated the time to prepare for an audit beyond the single industry expert estimate and has not explained how the exporters who participated in the anonymous user research are representative of industry.

Farm businesses making capital investments (AG-09)

2.38 Performance measure AG-09 reports on the proportion of farm businesses making capital investments with a specified target of new farm capital investment increasing. The performance statements state that an increase in new capital investments is ‘a proxy for measuring stronger confidence and a direct indicator of sectoral growth’ (per the Agriculture Objective). The result is ‘partially achieved’ with the following figures reported:

- five-year average to 2018–19: 56 per cent;

- five-year average to 2019–20: 55 per cent; and

- five-year average to 2020–21: 55 per cent.

2.39 The reported result of ‘partially achieved’ is not correct and is identified as a material misstatement in the auditor’s report. In the absence of an increase in the percentage of farm businesses making new capital investments, the result should have stated ‘not achieved’.

Increased responsiveness to post-border detections (BI-04)

2.40 Performance measure BI-04 reports on whether the department has ‘increased responsiveness’ to post-border biosecurity detections. The target is that ‘incidents are managed in a timely way to decrease the risk to the environment’.

2.41 The data sources and methodology for this measure have not been clearly identified. It is unclear, therefore, whether the information presented in the performance statements represents ‘partial’ achievement of ‘increased responsiveness’, management of incidents in a timely way, or a decreased risk to the environment.

2.42 Without a reliable and verifiable methodology to assist measuring the result, the ANAO cannot verify the accuracy of the result reported in the performance statements.

Performance measures on World and National Heritage Listed Properties (EN-07-1 and EN-07-2)

2.43 Performance measures EN-07-1 (World Heritage-listed properties) and EN-07-2 (National Heritage-listed properties) report on the percentage of listed properties with management plans that are consistent with principles in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) regulations. The department seeks annual updates from World Heritage property and National Heritage property place managers (third parties) and enters this information into ‘stocktake spreadsheets’ (World and National). These spreadsheets are the key data source for this performance measure.

2.44 The ANAO was not able to obtain sufficient evidence to verify the accuracy of the reported results for these measures. The audit has assessed that these measures fail the requirement of subsection 16EA(b) of the Rule, given the department:

- was not able to provide complete and accurate records to support the reported results;

- stated that it ‘has not verified the assurance from place managers of their plans’ consistency with the National Heritage management principles’;

- provided the audit with evidence from place managers that was inconsistent with data in the stocktake spreadsheets; and

- only provided the ANAO with partial evidence to verify the data in the spreadsheets, stating that not all place managers respond to requests for information and the department does not always retain the documentation.

Department of Social Services

2.45 DSS’ 2021–22 performance statements reported on 37 performance measures underpinned by 50 targets. The auditor’s report on the DSS’ annual performance statements was qualified with respect to one performance measure, a reduction from eight measures in 2020–21. There was also an Emphasis of Matter relating to one measure (see paragraph 2.50).

New qualification

Volunteering and Community Connectedness Be Connected (2.1.5-1)

2.46 The 2020–21 performance measure for the ‘Be Connected’ program (2020–21 performance measure 2.1.5-2) was qualified given DSS had not gained appropriate assurance over the reported results from two surveys of program participants.

2.47 The measure was changed in the 2021–22 reporting period from a measure of satisfaction, to a measure of outputs (the number of learners supported within a target range of 11,000 to 14,000).

2.48 DSS was not able to verify the number of learners. DSS did provide caveats that the reported number of learners does not include those who independently accessed the online learner portal and learners who received support from a Network Partner but did not register.

2.49 DSS did not meet the requirement of subsection 16EA(b) of the PGPA Rule, as the department was unable to verify the accuracy and the completeness of the reported result. It was determined the reported results could not be relied upon, notwithstanding the caveats disclosed in the statements.43

Emphasis of matter

Family safety performance measure (2.1.2-1)

2.50 DSS’ 2021–22 annual performance statements included a performance measure (2.1.2-1) relating the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the national plan).

2.51 One of the initiatives under the national plan relates to 1800RESPECT. The ANAO identified that the department did not have a process in place to independently validate the reported result from the department’s service provider on the number of calls answered in less than 20 seconds, and was unable to provide assurance that the reported result is accurate.

2.52 An Emphasis of Matter was included in the 2021–22 auditor’s conclusion to draw the user’s attention to the caveats and disclosures included in the annual performance statements for this measure. The Emphasis of Matter relating to the 1800RESPECT component of the Family Safety performance measure directed the reader’s attention to DSS’ disclosure in the performance statements that the department did not have a process in place to independently validate the reported number of calls answered in less than 20 seconds.44

2.53 The auditor’s conclusion was not modified with respect to this matter. In correspondence to the ANAO on 23 November 2022, the DSS Secretary notes ‘I fully accept that the findings are for the audit office to make and that there was a gap in our verification process’ but did ‘not consider…[the] issue posed a significant risk to the performance statements or constituted a material mis-statement to justify the A finding’.

Resolved qualifications from 2020–21 audit

Family safety performance measure (2.1.2-1)

2.54 The audit report stated in relation to 2.1.2-1:

I assessed performance measure 2.1.2-1 as not being appropriate. The target applied to report against performance measure 2.1.2-1 relates to the implementation of the Entity’s initiatives as part of the ‘National Plan to reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–22’. The target is a measure of the Entity’s activity and does not relate directly to the achievement of the Entity’s purposes related to performance measure 2.1.2-1 which is contributing to a reduction in violence against women and their children. Furthermore, I was unable to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence over the completeness and accuracy of the Entity’s records in regard to the reported achievement of this measure.

2.55 In 2021–22, the department revised the construct of the measure, aligning the measure and the target, and developed a more robust methodology, which resolved the issues that were the basis of a qualified audit conclusion in 2020–21.

Volunteer grants performance measure (2.1.5-1)

2.56 DSS revised this performance measure in 2021–22 due to the inherent bias of the prior year survey to determine an outcome and to meet the requirements of the PGPA Rule. The revised measure is as follows:

- Measure: Extent to which volunteers of the grant recipient organisations are supported to conduct their volunteer work; and

- Target: Number of volunteer grants awarded.

2.57 The ANAO verified the 2021–22 result for the revised volunteer grants measure. On this basis, the qualification is considered resolved.

Data Exchange (DEX) related performance measures (2.1.1-1, 2.1.4-1, 2.1.4-2, 2.1.5-2 and 3.1.3-1)

2.58 In its 2020–21 annual performance statements, DSS reported against five performance measures where service providers in receipt of DSS funding entered data on their clients into DEX.45 The department did not have adequate internal controls in place to validate the accuracy of the results reported by service providers to mitigate the risk that the reported results were not unbiased.

2.59 DSS’ main action to address this finding was to engage Australian Survey Research (ASR) to conduct a client survey to ‘validate and verify provider data to help ensure that it is accurate and unbiased’. DSS conducted a test to see the extent to which ASR survey responses matched what service providers had reported in DEX. DSS concluded that ‘the alignment tests have validated the DEX data and shown that there is minimal positive reporting bias by service providers’.

2.60 Given the implementation of these processes, the qualification is considered resolved.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs

2.61 The auditor’s report on DVA’s 2021–22 annual performance statements was qualified with respect to two of 46 performance measures (compared with two of 43 measures in 2020–21).

New qualification

Reliable and verifiable data sources and methodologies, and other record keeping matters (measures 3.1.1 and 3.1.2)

2.62 With respect to the two measures in Program 3.1 Provide and maintain war graves (measures 3.1.1 and 3.1.2), DVA could not demonstrate processes to support the completeness, accuracy and reliability of data in the War Graves System and did not use sources of information that were reliable or verifiable to support the reporting of a result. In addition, the Department’s assurance process of departmental staff visiting a selection of war graves to assess work undertaken by contractors was not effectively implemented during the period. The department was unable to provide the ANAO with information in regard to the selection of locations to be assessed, how the locations were selected, what sites were visited or reports providing the outcomes of the reviews.

2.63 While the department accurately stated ‘unable to report’ against the results for these two measures and the disclosure in the performance statements noted the issues of incomplete data, these measures are material to the performance reporting as maintenance of war graves is a part of the department’s purpose. On this basis the ANAO issued a qualified audit conclusion.

Resolved qualification

Inability to obtain sufficient evidence to support the result

2.64 DVA’s 2020–21 performance statements contained a measure in Program 1.5 Financial assistance to eligible students (measure 1.5.4) relating the progress of students through their education or career training. DVA’s records to support the result were incomplete with the department unable to provide evidence to support the current or previous year enrolment details for sampled students. The reported result was based on the presumption that students had progressed through the relevant level of education.

2.65 For the performance measure relating to support through Open Arms in Program 2.5 Mental and allied healthcare services (measure 2.5.6), DVA was unable to provide records to show it had appropriate controls to assure the reliability of the underlying systems from which the performance measure was reported. The ANAO was therefore unable to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to assess the completeness and accuracy of those records, and was unable to conclude whether the results reported against this measure were accurate and complete, and supported by appropriate records.

2.66 The DVA Executive Management Board approved the removal of these measures for the 2021–22 reporting period. On this basis, the 2020–21 qualification was removed.

3. The development of entities’ external performance reporting processes

Coverage of chapter

This chapter highlights areas of better practice and where opportunities exist to improve the quality of performance information in annual performance statements.

Areas of better practice

Areas of better practice in performance reporting include:

- performance statements governance and preparation processes, enabling the finalisation of performance statements audits in a timeframe that would enable the audited performance statements to be included in entity annual reports, consistent with the approach for entity financial statements;

- the timeliness and quality of supporting documentation for performance measures, which assists entities to develop appropriate performance measures consistent with the requirements of the Commonwealth Performance Framework;

- the structure and quality of performance information in entity performance statements. Entities improved the clarity and alignment of their purposes, key activities and performance measures included in performance statements;

- use of surveys by entities, where appropriate, to measure and report their performance, including strengthening survey methodologies and quality assurance processes; and

- use of external experts to support their performance reporting was generally well planned and documented. The entities used a variety of experts’ measurement and analysis to inform their performance reporting.

Opportunities for improvement

Opportunities to improve entity performance reporting include:

- entities developing an enterprise level performance framework to integrate performance reporting into a cycle of ongoing planning, monitoring, evaluation and review;

- periodic monitoring and reporting of performance results. Most entities have not established processes to periodically monitor and report against performance measures, including to audit committees, whereas it is an established better practice in relation to financial information;

- development and reporting of outcome-based performance measures and targets;

- integrating reporting requirements to reduce the reporting burden and improve clarity, establishing the performance statements as the primary vehicle for reporting the performance of Commonwealth entities; and

- strengthening capacity across the sector. Entities are seeking additional support and guidance on the development and reporting of high-quality performance information.

Areas of better practice

3.1 There are several areas of better practice in performance reporting that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has identified following the completion of the six 2021–22 annual performance statements audits. These emerging practices indicate that entities are committed to improving their processes to plan, measure and report their performance to the Parliament in accordance with the performance reporting requirements of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule).

Performance statements governance and preparation processes

3.2 Strong governance and preparation processes — including the way entities plan, assess and report their performance information — enable entities to effectively prepare high quality performance statements. These can reduce the risk of untimely, inaccurate or unreliable reporting. They can also support management reporting throughout the year creating efficiencies. Good governance and preparation also assists performance statements audits to be conducted in a timeframe that would enable the audited performance statements to be included in entity annual reports, consistent with the approach for entity financial statements.

3.3 During the 2021–22 reporting period, all six entities improved aspects of their governance and preparation processes. For example, entities:

- established a schedule for preparing annual performance statements with key deliverables and deadlines;

- clarified lines of responsibility between the central governance team responsible for the preparation of the annual performance statements and program divisions, which are responsible for the operational performance of key activities and programs;

- developed timely and high-quality supporting documentation on each performance measure;

- improved risk assessment processes to identify areas of risk that could impact the quality and accuracy of the annual performance statements; and

- improved processes to monitor and report performance results internally during the reporting period and to engage and update audit committees.