Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Upgrade of the M113 Fleet of Armoured Vehicles

The objective of the audit was to assess the progress of the M113 Upgrade Project (Defence Project: Land 106), including progress in the development of operational capability resulting from the introduction of the upgraded vehicles into service. The high-level audit criteria used to assess the project’s progress and Defence’s effectiveness in administering the M113 Upgrade Project were:

- the degree to which the schedule for the production and delivery of upgraded M113 vehicles to Defence had been recovered in accordance with Defence’s response to the 2008–09 audit report and contractual requirements, as negotiated over the life of the contract;

- Defence’s measurement and allocation of the total cost of the upgrade project; and

- the development of capability arising from the upgrade project.

Summary

Introduction

1. The M113s are a family of tracked vehicles, the most common variant of which is the Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC). The other six variants are: the Armoured Fitter (AF), the Armoured Recovery Vehicle Light (ARVL), the Armoured Logistics Vehicle (ALV), the Armoured Ambulance (AA), the Armoured Command Vehicle (ACV) and the Armoured Mortar (AM).1 They are the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF’s) only tracked vehicles available for transporting and providing close-combat support for infantry in battle. The M113’s primary function is to allow Army to effectively mount close-combat operations in a variety of threat environments, including by protecting the lives of the soldiers who rely on the vehicles as one of their main tools of battle.

2. The Department of Defence (Defence) is currently upgrading 431 of its aging fleet of over 700 M113s, which first saw service during the Vietnam conflict in the 1960s. The upgrading of the M113s commenced in 1992, with the decision to undertake a $50 million minor upgrade of the entire fleet to provide an interim capability until a replacement vehicle could be developed and produced.2 However, successive changes to the scope of the upgrade commenced almost immediately and by 2001 government had approved instead a project3 to undertake a major upgrade of 350 M113s at a cost of $594 million (October 2001 base date dollars).4 The Major Upgrade Contract was originally signed with Tenix Defence Pty Ltd in 2002,5 however in June 2008 Tenix Defence was purchased by BAE Systems, which is now the Prime Contractor.6

3. In August 2006, the Government approved Stage 1 of the Enhanced Land Force (ELF) initiative, designed to provide an increase in land force capacity to assist the ADF sustain multiple operations. Army’s then only mechanised infantry battalion, 5th/7th Battalion Royal Australian Regiment (RAR), was subsequently split in December 2006 to form two mechanised infantry battalions (5 RAR and 7 RAR) in the 1st Brigade (1 Brigade). In October 2008, the Government approved a proposal, as part of implementing ELF, to purchase an additional 81 upgraded M113 APCs under the Major Upgrade Contract so that 5 RAR and 7 RAR could operate M113s exclusively, rather than a mixed fleet of M113s and Bushmasters. The estimated total cost of the additional 81 vehicles was $222.1 million (2008–09 budget out-turned prices).7

4. In 2010–11, the total approved budget for the major upgrade project stood at $884.3 million (2010-11 budget out-turned prices). However, not all of the costs of upgrading the M113s are incurred under the Major Upgrade Contract. The cost of preparing and extending the hulls of the 350 vehicles originally ordered in 2002 is met by Army sustainment funding under another contract with the same contractor (the Commercial Support Program (CSP) Contract).8 The personnel and operating costs of the upgraded fleet and the costs of staffing and operating the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) project office also do not form part of the project budget. The estimated whole-of-life cost for the M113 fleet from 2002–03 to 2025–26, including both the capital costs of upgrading the M113s and the estimated personnel and operating costs of the upgraded fleet over its life, is some $1.6 billion.9

5. The first 16 upgraded vehicles were delivered to Army late in 2007 and, over four years later, a total of 356 upgraded vehicles had been accepted by Defence. The upgraded M113s are the core capability of Army’s two mechanised infantry battalions, 5 RAR and 7 RAR, in 1 Brigade. 1 Brigade has received over half of the upgraded vehicles delivered thus far, with the remainder either allocated to training or held in storage.10 The remaining un-upgraded M113s were progressively withdrawn from service from 2006.

6. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) previously examined the progress of Defence and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) in delivering this project in Audit Reports No.3 2005–06 Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project, and No.27 2008–09 Management of the Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project.

7. Defence’s overall response to the 2008–09 audit included the following statement:

The M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier vehicle fleet is undergoing a major upgrade under Project Land 106 which will realise a significant capability improvement over its current design. The Defence Materiel Organisation is charged with managing the $850 million Project and will deliver 350 upgraded M113 vehicles by December 2010 and [an] additional 81 upgraded vehicles under the Enhanced Land Force initiative by 2011.

8. In undertaking this third audit of the project, the ANAO sought not only to examine Defence’s progress in delivering the upgraded M113s into service, but also to examine the capability the vehicles have thus far provided to Army.

9. Defence defines capability as the:

capacity or ability to achieve an operational effect. An operational effect may be defined or described in terms of the nature of the effect and of how, when, where and for how long it is produced.11

10. Achieving capability can be complex, and requires more than purchasing equipment. The development of capability involves effectively combining the multiple personnel, equipment and support system inputs required, which Defence has codified in the Fundamental Inputs to Capability (FIC–see Table 5.1 and Appendix 1).

11. In the case of the upgraded M113s, these fundamental inputs include the vehicles, the systems and arrangements for training personnel and for administering support equipment, parts and spares and conducting maintenance, as well as those required for overseeing and planning operations and exercises. Achieving capability with the upgraded M113s also requires battle doctrine and plans to be developed, crews to be trained and exercised with the vehicles (preferably in concert with tanks) to test doctrine and plans, for performance to be evaluated and lessons learned, and for the logistics chain, including repairs and spares, to be effectively in place.

Audit approach

12. The objective of the audit was to assess the progress of the M113 Upgrade Project—LAND 106,12 including progress in the development of operational capability resulting from the introduction of the upgraded vehicles into service. The high-level audit criteria used to assess the project’s progress and Defence’s effectiveness in administering the M113 Upgrade Project were:

- the degree to which the schedule for the production and delivery of upgraded M113 vehicles to Defence had been recovered in accordance with Defence’s response to the 2008–09 audit report and contractual requirements, as negotiated over the life of the contract;

- Defence’s measurement and allocation of the total cost of the upgrade project; and

- the development of capability arising from the upgrade project.

13. ANAO commenced this audit of the major upgrade project in November 2010, shortly before the last of the original 350 vehicles were due to be delivered under the contract schedule both as originally framed in 2002, and as in place at the time of the 2008–09 audit. Audit fieldwork was conducted during the period November 2010 to October 2011. The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $625 000.

Overall conclusion

14. The M113 upgrade has, in one form or another, been underway since 1992. In its most recent form, the M113 major upgrade project (also known as Project LAND 106) commenced in July 2002 and involves extending ageing M113 hulls and fitting them with new or refurbished components and equipment. For an investment totalling more than $1 billion, the ADF expects to receive 431 upgraded M113s as an interim capability to carry it through to 2025 and the projected replacement of its armoured vehicles as part of Project LAND 400.13

15. This third audit of the M113 upgrade identified that the project continued to suffer from various technical, administrative and contractual problems following the November 2007 global settlement between Defence and the original Prime Contractor resulting in additional schedule delay. Following a further contract renegotiation in 2011, the majority of vehicles have now been delivered with Defence confident that the remaining vehicles will be delivered by late 2012 as per the revised contract. However:

- the project has suffered significant production delays over its life;

- deficiencies in the project’s original contract, in particular the failure to properly specify payloads, meant that technical problems with the vehicles’ design and production could not be effectively managed under its provisions;

- overall Defence’s cost and schedule management has not been effective, and Defence has been slow to respond to continuing project delays;

- a further contract renegotiation was required in 2011 to address claims by both Defence and the Prime Contractor. It resulted in DMO making financial and schedule concessions in order to maintain production rates and rectify contractual deficiencies. However, since this renegotiation, production has been in accordance with the revised schedule;

- senior decision-makers within Defence and government have not always been kept informed of the project’s status in a timely and accurate fashion affecting their capacity to make informed decisions in relation to the project; and

- the upgraded M113 does represent an improvement on the older, un-extended vehicle. However, a vehicle that was considered fit-for-purpose when the minor upgrade was first proposed 20 years ago now lags behind armoured infantry vehicles in use with other armed forces, and is vulnerable in many current threat environments, leaving Defence with an acknowledged capability gap.

Production delays

16. ANAO’s two previous audits of this project, in 2005–06 and 2008–09, each identified delays in development and construction evident from early in the M113 upgrade project that have not been recovered and have continued.14 The upgraded vehicles were originally expected to progressively enter into service from 2006, with the final vehicle of the 350 originally ordered due to be delivered by the end of 2010. However, in the event, the first production vehicles were not accepted by Defence until November 2007 and by December 2010 only 194 vehicles had been accepted.15

17. The delays led to major contract renegotiations between Defence and the original Prime Contractor in 2007 and again in 2011 with the current Prime Contractor. The intended outcome of the 200716 global settlement negotiations was to catch-up production, with the original Prime Contractor agreeing to a compressed schedule that still required delivery of all 350 vehicles by December 2010 and Defence agreeing to an incentive payment of $2.716 million if the December 2010 deadline was met.17

18. However, at no time between November 2007 and December 2010 was production on track to meet this schedule. This was so, notwithstanding the original Prime Contractor, in efforts to recover the schedule, having opened at its cost additional production facilities in Williamstown, Victoria and Wingfield, South Australia in late 2008.18

19. Between the 2007 and 2011 contract renegotiations, two major scope changes had also impacted the contract schedule:

- As noted in paragraph 3, in October 2008 the Government approved a proposal to purchase an additional 81 upgraded M113 APCs. The resulting contract amendment pushed out the due date for delivery of the final vehicle under the Major Upgrade Contract from December 2010 to November 2011, albeit with the original 350 vehicles still contracted to be delivered by December 2010; and

- In August 2009 the Government approved a proposal to extend the 21 Armoured Mortar variant vehicles.19 The additional work required as a result of this decision led Defence and the Prime Contractor to agree a contract amendment that pushed the scheduled delivery date of these vehicles past the December 2010 deadline, reducing the total number of vehicles then contracted to be delivered by December 2010 from 350 to 329. The delivery date for the final vehicle of the total of 431 on order also moved out from November 2011 to April 2012.

20. Given the continuing production delays, further negotiations were subsequently required during 2011 to settle a range of claims and counter-claims between Defence and the Prime Contractor. The latest round of contract negotiations culminated in the parties signing a deed of agreement and an amendment to the Major Upgrade Contract in August 2011.20 Under these arrangements, Defence accepted a revised schedule that extends the contractual delivery date of the final vehicle from April 2012 to December 2012.

21. Root causes of the delays can be traced to the earliest days of the project, and in particular to shortcomings in Defence’s approach to key engineering and contracting issues. Defence did not always act as an informed purchaser of the engineering and technical services necessary to successfully deliver the vehicles and, as a consequence, the engineering risks apparent early in the project’s life were not managed effectively.

22. Key engineering risks included the adoption of a new construction technique that relied for success on unfounded assumptions of the quality and consistency of the ageing M113 hulls that were to be upgraded.21 Further, insufficient attention was paid to proving the hull extension production process. This delayed the achievement of a fully effective vehicle construction and assembly process, which was not achieved until late 2010, four years later than originally anticipated and over eight years after the commencement of the current major upgrade project.

Impact of deficiencies in the original contract

23. Deficiencies in the Major Upgrade Contract meant that technical problems with the vehicles’ design and production could not be effectively managed under its provisions. Contrary to the advice tendered to government when the major upgrade was initially approved, critical milestones were not effectively incorporated into the contract, which also failed to properly specify vehicle payloads, prioritise vehicle technical specifications in order of necessity and desirability, or establish clear terms for liquidated damages.22 Over the life of the contract, Defence has sought to correct these deficiencies through various contract amendments, most recently in August 2011.

24. However, these deficiencies have reduced Defence’s capacity to effectively manage project risks through the contract, while simultaneously contributing to the numerous extensions of scope that have been a feature of the project. In particular, the failure to properly specify payloads in the contract led to initial vehicle production designs that compromised payload capacity as a means to remain within the gross vehicle weight limit of the vehicles, particularly for variants that were not originally planned to be built on an extended hull. To address this issue and achieve appropriate vehicle designs, Defence found it necessary to seek approval for successive changes to scope so that now all seven variants are to be extended, rather than extending only three variants as envisaged in 2002 when government originally approved the major upgrade.

Cost and schedule management

25. Overall, Defence’s cost and schedule management of the M113 upgrade has not been effective. Management and reporting has focused on the Major Upgrade Contract costs rather than total costs,23 and there have been significant, unanticipated increases in the estimated life cycle costs.24 In addition, higher than anticipated costs for work to prepare and extend M113 hulls prior to entry to the major upgrade assembly line, together with delays in finalising the designs of the variants, assembly capacity limitations, and the re-work requirements for completed vehicles, highlight that the project’s systems engineering process has also been underdeveloped.

26. Although aware that the Prime Contractor was significantly behind schedule, Defence was slow to respond to the continuing delays in delivering vehicles following the 2007 global settlement. Expenditure and production data provided by the Prime Contractor, and paid for under the Major Upgrade Contract, was not appropriately analysed by Defence. ANAO analysis of this data for the period October 2007 to April 2011 shows that while schedule slippage was particularly evident from January 2009, project expenditure continued as forecast. This can be attributed, in part, to: bringing forward the construction of the 81 additional, more expensive ELF M113s ordered by Defence in October 2008; and the purchase of costly long lead-time components in advance of need.25

2011 contract renegotiation

As discussed in paragraph 20, the delays led to another contract renegotiation to address claims by both Defence and the Prime Contractor that was concluded in August 2011. While Defence initially considered it would be in a strong position to refute the Prime Contractor’s claims, closer examination of the contract and previous actions of both parties soon led Defence to instead reach agreement with the Prime Contractor that the issues were ‘complex and multi-faceted and that responsibility for delay is shared between the Commonwealth and [the Prime Contractor]’.26 In response to the proposed audit report, Defence informed the ANAO that it had concluded that, to resolve the situation and get the vehicles as soon as possible for Army: ‘a ‘commercial’ approach would provide a better result than a ‘contractual’ approach’.

28. The outcomes of these negotiations included:

- the withdrawal by the Prime Contractor of $5 million in postponement claims;27

- agreement by Defence not to exercise contractual rights to seek liquidated damages of approximately $1 million for late delivery of vehicles;

- the agreement between the parties of a 9 December 2012 final delivery date for all vehicles; and

- incorporation into the contract of provisions providing the potential for incentive payments totalling $2.8 million to be made to the Prime Contractor if certain production targets are met over the period between August 2011 and October 2012, including bringing forward the final vehicle delivery to 31 October 2012.28

29. Defence further informed ANAO in March 2012 that the key purpose of these incentive payments was to ensure the Prime Contractor’s additional production facilities were not closed early to reduce the Prime Contractor’s costs, which would have resulted in further schedule delay.

30. Since the August 2011 contract renegotiation, production has been on schedule. Defence informed ANAO in March 2012 that the Prime Contractor’s subsequent production performance was sufficient to receive the first and second quarterly incentive payments available under the contract as amended, and that production in the third quarter has been sufficient to receive the third quarterly incentive payment. Defence considers that the Prime Contractor is currently on course to deliver all 431 vehicles by October 2012.

Advice to government and senior decision-makers

31. Over the life of the project, senior decision-makers within Defence and government have not always been kept informed of the project’s status in a timely and accurate fashion. Ongoing delays prompted the Government to place the M113 upgrade on its Projects of Concern list in December 2007. It was removed from that list in May 2008 on the basis of Defence advice that included incorrect information regarding production rates, and assurances that schedule delay would be recovered. Subsequent advice to government in support of the 2008 proposal to acquire a further 81 upgraded APCs and the proposal to extend the AM variant29 also contained incorrect and unrealistic advice relating to schedule production rates and projections. There have been several such instances of incorrect and/or unrealistic reporting on project status, and issues affecting this, over the life of this project.30

32. Notwithstanding the schedule slippage experienced by the project, and the ongoing engineering difficulties with the vehicles, Defence purchased an additional 81 vehicles at a significantly increased unit cost, and provided the Prime Contractor with a fourth prepayment of $16.2 million (October 2001 base date dollars) in 2008.31 The 2008 payment raised the total quantum of prepayments to the Prime Contractor in respect to upgrading Defence’s M113s to over $100 million (approximately 20 per cent of the Major Upgrade Contract value). This prepayment was made despite there being no ramp-up costs for the Prime Contractor, as the additional vehicles were to be upgraded using an established production line where APCs are the most produced variant. Providing a prepayment to an established production facility was at odds with normal commercial practice and the guidance contained in Defence’s own procurement policy.

33. When seeking government approval for the purchase of the 81 additional upgraded vehicles, Defence advised government that the unit cost of each of these vehicles was comparable to that of the APCs originally contracted in 2002. However, the total cost for upgrading the 81 additional vehicles is approximately $11.4 million (2001 base date dollars) more than the cost of upgrading to the same standard 81 APCs under the terms applying to the original 350 vehicles, despite being produced on the same production line.

Capability

34. In addition to engineering and contracting issues, capability issues have arisen in the course of the project. The delivery of new capability requires more than the delivery of a new or upgraded platform. The effective operation of new capability also relies on combining the multiple personnel, equipment and support system inputs, which Defence identifies as its Fundamental Inputs to Capability (FIC). The development and delivery of the upgraded M113 vehicles has occurred in isolation from the development of some of these FIC elements.32

35. As a consequence, the ability to deploy and effectively use the upgraded M113s is constrained by limitations in several key inputs to capability, including less than optimal communication systems, and restrictions on transporting the vehicles by means of Defence’s existing land and air assets. These issues have only been identified toward the end of the upgrade project. Remedying them relies on other allied Defence projects, which in some cases will take some years, and potentially will affect the M113 fleet through most of its remaining life.

36. As Army’s front-line mechanised infantry platform, the M113’s primary function is to allow Army to effectively mount close-combat operations in a variety of threat environments, including by protecting the lives of the soldiers who rely on the vehicles as one of their main tools of battle. Over the course of the M113 upgrade project, Defence and Army have confirmed to government the continuing requirement for these vehicles and Defence informed government in 2008 that an additional 81 upgraded vehicles were required in addition to the 350 vehicles then on order. However, since the commencement of the major upgrade in 2002, the threat environment for Army’s infantry forces has changed significantly, both in terms of the methods of current enemies and potential threats, and the military hardware they possess.

37. As a consequence of the delays in the design and production of the upgraded vehicles, this project is now delivering an increasingly dated class of vehicle. The Acting Chief of Army, as Capability Manager for the of the upgraded M113 fleet, informed ANAO in December 2011 that the upgraded M113 fleet of vehicles ‘is a significant improvement to the obsolete [un-upgraded fleet of vehicles] and affords greater flexibility in mechanised force structure for a range of contingency and future tasks until the comprehensive mounted close combat capability that will be provided by Land 400 solutions’.33 However, he also identified that a capability gap currently exists across all mechanised close-combat operations:

It is important to note that while the [upgraded M113] is a capable combat vehicle, it does have constraints and limitations through design and capacity as it is based on the [original M113] hull. This factor limits its potential in comparison to higher order platforms including current generation [infantry fighting vehicles]. This fact essentially provides a capability gap for the conduct of close combat across the spectrum of conflict until the introduction into service of the Land Combat Vehicle System (Land 400).34

38. In response to the draft audit report, in April 2012 the Chief of Army provided clarifying comments on the use and meaning of the term ‘capability gap’:

The term refers to the difference between a stated capability requirement and Army’s ability to fulfil that requirement … While the existing level of protection of the [upgraded M113] is high, analysis shows that the vehicle’s major limitation will be its ability to support close combat operations against an enemy which is capable of employing a broad variety of conventional and unconventional methods of attack.35

39. The Chief of Army also noted that:

as the Capability Manager … I am satisfied that the [upgraded M113] provides a significantly enhanced capability to Army and that it is a potent and capable platform. I am also satisfied that the delivery of [the upgrade project] satisfies the original requirement specified by the Capability Manager.

40. The upgraded M113 does represent an improvement on the older, un-extended vehicle. However, a vehicle that was considered fit-for-purpose when the minor upgrade was first proposed 20 years ago now lags behind other armoured infantry vehicles, and is vulnerable in many current threat environments. The major upgrade of the fleet, first announced in the 2000 Defence White paper, was only intended as ‘an interim or bridging capability’ until a replacement family of vehicles could be procured.36 However, LAND 400, which will include a replacement for the M113, does not currently plan to deliver its first operationally ready units until 2025–26 at the earliest,37 leaving Army a vehicle with significant limitations that is currently due to be withdrawn from service commencing around 2025.

41. At several stages during the project, Defence has reaffirmed the need to continue with the procurement of the upgraded M113s. In March 2007, Defence advised the then Minister that ‘termination [of the major upgrade project] is not being considered at this stage owing to the importance of this capability and the cost and schedule of viable alternatives’.38 Defence further justified to government in 2008 the purchase of the 81 additional upgraded M113s on the basis that:

- the upgraded M113s provided superior protection in comparison to the Bushmaster and ASLAV;

- the vehicles could be deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan with relatively low-cost upgrades; and

- the vehicles could withstand heavy machine-gun fire.

42. As late as March 2009, Defence’s assessment was that there were no viable alternatives to the upgraded M113s, and that delays in the development of the upgraded M113 capability were manageable. However, a number of key capability aspirations sought by Defence for the upgraded M113 capability have to date either been only partially achieved, are yet to be achieved or have proven unachievable (see Table 5.4).

43. It is an inherent risk in Defence major capital acquisitions that the often substantial elapsed time between approval and completion may lead to a gap opening up between the delivered capability and the requirements of the contemporary threat environment. In addition the long time-frames, of themselves, present challenges in coordinating the delivery of required FIC elements to generate the planned level of capability and project delays complicate this further. These circumstances require active management by Defence to successfully deliver these major projects.

44. In the case of the M113 upgrade project, this inherent risk has been exacerbated by the project’s history. The current Major Upgrade Contract was let without an open tender process and arose originally from an unsolicited proposal from the original Prime Contractor, who was at the time contracted both to undertake a minimal upgrade of M113 fleet and the sustainment work for the vehicles under the CSP Contract. The scope of the project has subsequently required extension several times, particularly in terms of extending all seven of the variants and acquiring the additional 81 ELF vehicles. However, during this audit, and the previous two ANAO audits, Defence has not been able to provide appropriate evidence that alternative strategies to deliver the required capability were effectively considered.

45. Even as originally planned, the M113 major upgrade project was expected to span some 8 years. In the event, some 10 years are currently expected to elapse before it is completed, albeit this includes several changes to the project’s scope including the acquisition of an additional 81 upgraded vehicles. The extended time-frame covered by the project has also exacerbated the impact of initial technical and contractual deficiencies. However, the full implications of these deficiencies have not always been communicated to senior decision-makers inside Defence and government in a timely way.

46. Following the 2007 global settlement, improved production rates were not achieved by the Prime Contractor until November 2010, but these have subsequently been sustained. As discussed in paragraph 30, since the August 2011 production has been on schedule and Defence considers that the Prime Contractor is currently on course to deliver all 431 vehicles by October 2012.

47. While Defence has demonstrated persistence in the face of numerous difficulties, the centrality and potential implications of the engineering, contracting and capability issues that have arisen over the life of this project required the informed engagement of leadership at the highest level. However, accurate information about the status of the project and the full implications of key issues was not always communicated to senior Defence decision-makers and the Government, ultimately limiting their capacity to address key project risks and the emergence of a capability gap over time. Maintaining effective strategies and processes to avoid such a state of affairs is a matter for leadership, and it is essential that Defence’s current reform efforts reinforce the importance of the strategic assessment of projects at key milestones, based on the best information available.

48. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the coordination of inputs to capability when developing or upgrading combat platforms.

Key findings by chapter

Chapter 2 – Managing vehicle design and project scope

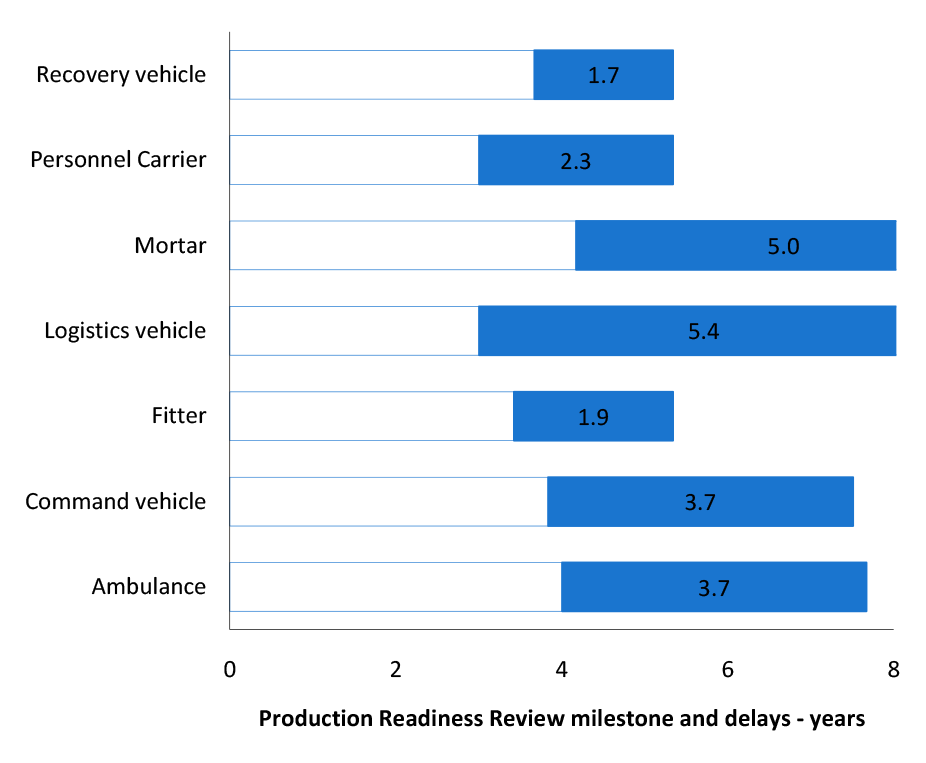

49. The design management framework for upgrading the M113 fleet is based on a series of critical design reviews and audits, culminating in a Production Readiness Review (PRR), which provides assurance that each variant is ready to enter full-scale production. As shown in Figure S 1, all variants in the M113 fleet suffered delays in completing their respective PRRs compared to the original contract schedule, particularly the ALV and AM variants.

Figure S.1: Delays in achieving the Production Readiness Review milestone against the original 2002 schedule

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence data.

50. This situation contrasts with DMO’s advice to the Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Procurement in May 2008 that, in its view, the major technical risks in the development of the M113 fleet were retired when the APC variant successfully completed its PRR in November 2007.39 Given the level of commonality in the other variants, DMO considered that the testing and development of the remaining variants was lower risk. The delays in the successful completion of PRRs, combined with slow production rates, have limited the number and range of variants delivered to Army thus far.

51. The prolonged development and design processes for the M113 variants resulted, in part, from the underestimation of the engineering requirements for the fleet upgrade at the outset of the major upgrade. This has been caused by an underdeveloped approach to the project’s systems engineering process. This is reflected in the unexpected findings that four of the seven variants (the ARVL, AA, AC and AM), if upgraded as planned based on their original unextended hulls, would exceed their Recommended Gross Vehicle Mass when loaded. From the outset the Major Upgrade Project contract provided for the extension of the hulls of the other three variants (the APC, AF and ALV)40, but, in the event, the hulls of all seven variants required extension to accommodate the weight of the upgrade. Defence’s contractual options for dealing with this issue were limited by defects in the Major Upgrade Contract, which included the failure to specify vehicle payload requirements in the original 2002 Major Upgrade Contract.

52. The scope of the upgrade project has changed significantly since the Government approved the major upgrade in June 2002. In addition to the progressive decisions to extend all seven of the M113 variants, rather than the three originally intended, 81 additional upgraded APCs were contracted for in 2008. The most recent scope change—the August 2009 decision to extend the AM variant—was based on various capability and cost benefits, however the primary cost benefit—the potential to replace the 81mm mortar—was predicated on a possible future decision for which no plans currently exist.41

53. Taken individually, each scope change has appeared moderate and manageable. If viewed in aggregate, however, their impact amounts to a major change in the overall design of the fleet, generating significant delays and highlighting the importance of maintaining strong overall design management.42 The 2008–09 ANAO report recommended that Defence set suitable threshold criteria for determining scope changes to allow decisions to be made on scope changes, especially where it involves changes in capability.43 Defence’s updated policy and guidance notes that scope changes may affect the capability originally sought, and highlights the need to engage with bodies such as Capability Development Group and the Capability Manager if capability changes affect the original project approval. However, this does not extend to documenting suitable threshold criteria for determining how significant changes in capability—including the timing of delivery and extent of capability to be delivered by a project—should be identified and considered for approval, irrespective of financial impact. In this context, Defence’s documented criteria remains focussed on financial thresholds, and Defence has some way to go before it has addressed the recommendation made by ANAO in March 2009.

54. As the responsibility for both design acceptance and for operational test and evaluation of Army materiel is vested in DMO, the degree and level of involvement of the Chief of Army as the Capability Manager in the agreement and management of the scope changes is not clear. There would be merit in Defence considering a greater separation of roles to provide a more transparent distinction between the organisation charged with developing major land systems, and responsibility for acceptance of the design, including major scope changes, which would benefit from the direct involvement of the Capability Manager. The current lack of separation between design acceptance and operational test and evaluation that exists for Army is at odds with the important principle that the organisation conducting operational test and evaluation should be independent from the equipment acquisition organisation.

Chapter 3 – Monitoring cost and schedule

Cost

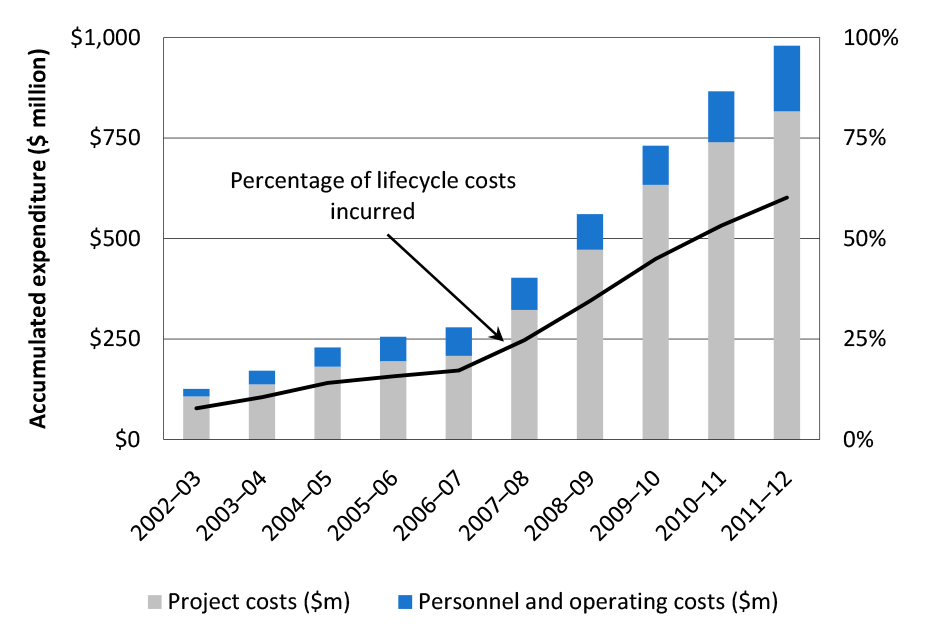

55. As at 30 June 2011, total expenditure on upgrading the M113s stood at $739 million, along with accumulated personnel and operating costs44 estimated at $127 million. As shown in Figure S 2, by July 2012 the accumulated expenditure on upgrading and operating the M113 fleet will approach $1 billion, or 60 per cent of the total estimated whole-of-life cost of more than $1.6 billion. Personnel and operating costs, including the costs of running the DMO Project Office, are not counted as part of the project’s cost. Defence estimates that personnel and operating costs will amount to $769 million over the life of the upgraded M113 vehicles.45

Figure S.2: Cumulative expenditure on upgrading and operating the M113 fleet, 2002–03 to 2011–12

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence data.

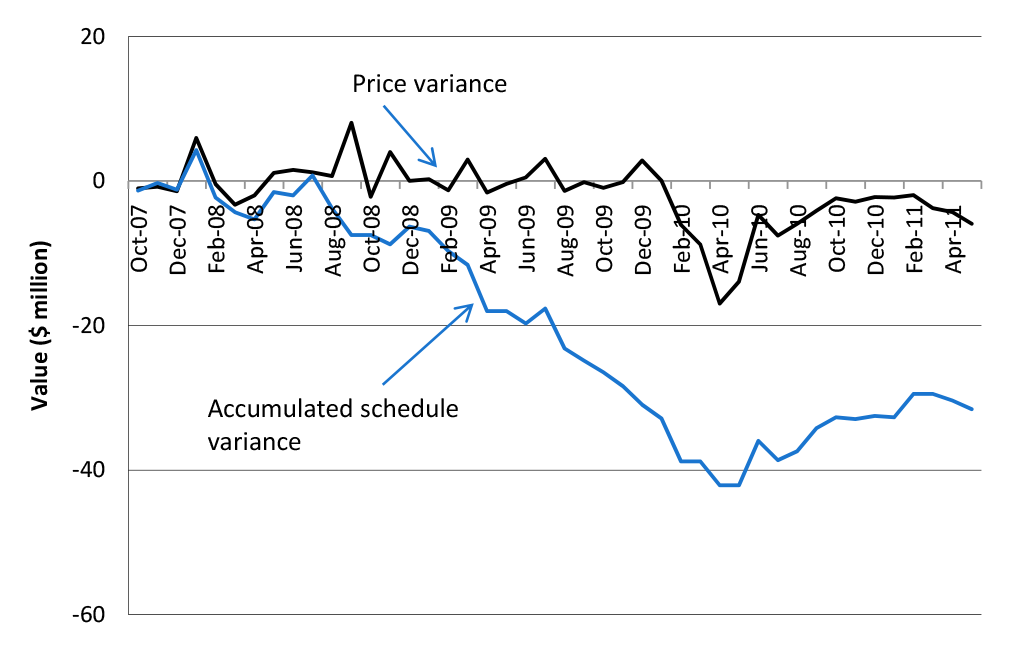

56. ANAO analysed monthly Cost Schedule Status Reporting (CSSR) reports provided to DMO by the Prime Contractor (see Figure S 3), comparing performance over time to the 2007 global settlement schedule (the schedule in place at the time of the last audit). This analysis indicates that Defence’s monthly expenditure was largely similar to that budgeted. However, from early 2009, actual schedule performance began slipping significantly behind the performance that would otherwise be indicated by the level of expenditure. Accumulated schedule slippage reached a low point in April 2010, with approximately $42 million of scheduled work not being delivered against the 2007 global settlement schedule.46

Figure S.3: M113 major upgrade project price and schedule variance trends

Note: CSSR reporting for the M113 project is based upon 'price' rather than 'cost'. Cost is the direct expense incurred for delivering a work package, while price is the amount the Commonwealth is paying for the work package. Price will include a rate of profit, and price is the basis of the deliverables listed in the Major Upgrade Contract's work breakdown structure.

Work conducted under the CSP is not included in this figure, as it is not performed under the Major Upgrade Contract.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

57. The trend identified in the CSSR data indicates that expenditure has occurred without the achievement of schedule, which may be attributed to a range of factors, including:

- The purchase of costly long lead-time items in advance of need: this has been done over time to avoid underspending budget allocations. ANAO fieldwork in September 2011 found 102 drive systems in stock (with additional drive systems in transit from overseas) worth approximately $51 million, which was in excess of need at the time.

- Higher contracted unit costs for ELF vehicles: despite Defence’s advice to the Minister that ELF APC unit costs were similar to unit costs of APCs under the Major Upgrade Contract, ANAO analysis shows that cost of the 81 ELF APCs will be approximately $11.4 million (October 2001 base-date dollars) more than for 81 of the originally contracted APCs out-fitted to the same standard.47

58. The contract amendment providing for the purchase of the 81 ELF vehicles included the provision of a $16.2 million prepayment (October 2001 base date dollars) to the Prime Contractor. Defence agreed to make this prepayment notwithstanding that the vehicles (all APCs) were to be built using an existing, well-established production line, where APCs are the most produced variant, and where no ‘significant non-recurring ramp-up costs’ are evident. This takes total advance payments over the life of the upgrade of M113s to some $100.4 million.48

Whole-of-life costs

59. At the time of project approval, Defence advised the Government that it estimated that the smaller upgraded M113 fleet would cost no more to run than the older, larger fleet it was replacing. During the 2008–09 audit, the ANAO sought information from Defence on the personnel and operating costs associated with the original M113A1 fleet of some 700 vehicles. However, Defence informed the ANAO that these costs were not recorded. It is not clear therefore what the baseline personnel and operating costs were that Defence used to estimate the likely quantum of these for the upgraded M113 fleet. As Defence has developed better cost estimates, factoring in the actual costs of operating these upgraded vehicles, its estimate of total personnel and operating costs has increased, with the current estimate close to $800 million (Budget 2010–11 prices) over the planned life of the upgraded vehicles to 2025. Part of the increased cost is due to the increase in size of the upgraded fleet from 350 to 431 in 2008.

Commercial Support Program Contract costs

60. Work on stripping, repairing, extending and painting most of the M113 hulls is conducted under a separate contract, the Commercial Support Program (CSP) Contract, and not provided for in the major upgrade budget. However, this work is funded from the major upgrade budget in respect of the additional 81 ELF APCs and the 21 AMs as a result of scope changes approved by government. Because of funding pressures in 2010–11 on Army’s sustainment budget (which funds M113 work under the CSP Contract), the production of the ELF APCs was brought forward, despite being originally scheduled to be produced last.

61. Defence and the Prime Contractor inspect stripped M113 hulls to determine whether it is feasible to upgrade them, based on both technical and economic viability. The cost of extending the hulls varies from hull to hull. After the first 40 hulls, when the necessary production techniques and systems had been established, the average number of hours worked on each hull has been in the order of 2200, for an average cost of approximately $96 000, almost double that estimated at the beginning of the production process.49 Up to December 2010, M113-associated costs under the CSP Contract were approximately $32.4 million, which are the latest costs available (based on Defence advice).

Schedule

62. At the time the last ANAO audit of this project was completed in March 2009, Defence was embarking on an ambitious program to recover the production schedule for upgrading the original 350 M113s, which were due by December 2010. In the course of that audit, Defence was not able to provide a contemporaneous analysis of the feasibility of the delivery schedule agreed as part of the 2007 global settlement.50 The recovery plan required increased production by the Prime Contractor, and with the decision to purchase an additional 81 APCs in October 2008, included opening additional facilities at Williamstown in Victoria and Wingfield in South Australia, which were to be operated at no additional cost to the Commonwealth.

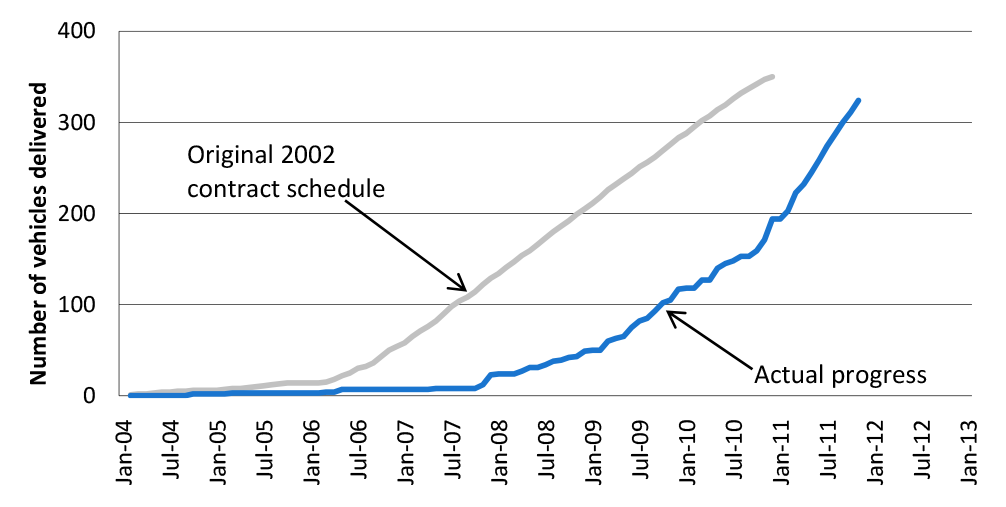

63. Figure S 4 compares the originally contracted schedule (350 by December 2010) with progress to date, showing that the schedule has not been recovered, and improved production rates have only been achieved since November 2010. By December 2010, only 194 of the required 329 vehicles had been accepted.51

Figure S.4: Originally contracted schedule and actual vehicle delivery, 2004 to December 2011

Note: The first upgraded vehicles produced were Initial Production Vehicles (IPVs or prototypes) required for testing prior to entry into full production, which occurred late in 2007.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

64. A range of factors have impacted on project schedule performance, including:

- delays in the preparation and extension of hulls under the CSP Contract to feed into the major upgrade production line;

- larger than anticipated numbers of vehicles requiring rework following quality assurance inspections, placing pressure on the production facilities at Bandiana, where there is limited room for rework;

- facility failures at the Defence-owned facilities in Bandiana;

- hull de-lamination,52 resulting in hulls requiring additional preparation work;53

- delays in the technical development of the ALV and AM; and

- shortages of vehicle communication harnesses to be supplied by Defence and required to complete the assembly of the vehicle.

65. However, the improved production rates achieved in November 2010 have been sustained since then. The Prime Contractor is meeting the quarterly production targets set out in the contract as renegotiated in August 2011, and Defence is confident that the Prime Contractor will deliver all 431 vehicles by October 2012.

Chapter 4 – Contract renegotiation and project reporting

66. A key outcome of the global settlement negotiations with the Prime Contractor in late 2007 was the development of a new production schedule that retained December 2010 as the date by which all of the original 350 vehicles were to be delivered.54 However, by December 2010, there had been no recovery of schedule as planned under the 2007 global settlement. Only 194 vehicles had been accepted for service by December 2010, of which 140 were APCs; 29 were Armoured Fitters (AFs); 13 were ARVLs; nine were ACVs; and there were two ALV Initial Production Vehicles (IPVs) and one AA IPV. Under the revised schedule that was current as at December 2010, more APCs and AFs should have been delivered by that time, and substantial progress should also have been made with delivery of ACVs and ALVs.

67. These continuing delays in the vehicles’ production led to another contract renegotiation. Preliminary discussions between Defence and the Prime Contractor commenced in June 2010—the actual contract negotiations commenced in February 2011 and concluded in August 2011. Initially, DMO was of the view that the delays were the responsibility of the Prime Contractor, and Defence would be entitled to recover liquidated damages. The Prime Contractor counter-claimed for $5 million in excusable delay claims, on the basis that the condition of the hulls, Defence facilities and equipment were responsible for delays. DMO’s rejection of this counter-claim triggered contractual dispute resolution procedures in November 2010.

68. After further review in February 2011, DMO reassessed its negotiation strategy for the following reasons:

- difficulty in documenting specific claims;

- receipt of more development documentation from the Prime Contractor;

- DMO may have already undertaken actions, or provided advice, that would contradict its own negotiation position; and

- the parties had been acting outside of certain contract provisions for a significant period of time, which would potentially undermine DMO’s attempts to enforce contractual dispute resolution clauses.

69. The main issues requiring negotiation were delays caused by:

- laminar cracking (which resulted in hulls being set aside until a suitable repair technique could be developed);

- missing/broken lifting eyes (which caused delays in moving hulls through the CSP process);55

- development of the AM variant; and

- facility failures at Bandiana.

70. DMO’s focus in the negotiations was to develop a new, realistic production schedule,56 and to provide contractual certainty over government-furnished materiel and the contractual liquidated damages regime. In order to achieve these goals, DMO was willing to provide an incentive payment for the Prime Contractor meeting a revised delivery date, and in return for each party withdrawing its claims regarding the period of delay.

71. In-principle agreement was reached in May 2011, with agreed outcomes subsequently finalised in late August 2011. The negotiation deed of agreement notes that the causes of the issues considered are ‘complex and multi-faceted and that responsibility for delay is shared between the Commonwealth and [the Prime Contractor]’.

72. The revised schedule specified that delivery of the final vehicle of the 431 to be upgraded was due on 9 December 2012, some eight months later the schedule agreed following the Minister’s approval in August 2009 of the change in scope to extend the AM variant. The Major Upgrade Contract, as amended in August 2011, now includes a total of $2.8 million in incentive payments57 should the Prime Contractor deliver all vehicles by 31 October 2012. The revised contract also improved the clarity of liquidated damages clauses and Government Furnished Equipment58 provisions, and Defence agreed not to seek liquidated damages against the Prime Contractor in respect of delays in delivery of vehicles over the dispute period and the Prime Contractor agreed not to seek its postponement costs claim.

73. As part of the negotiation process, in July 2011, DMO undertook an internal review of the proposed new schedule. The review was generally sceptical of the proposed new schedule, highlighting several risks and noting the lack of disclosure from the Prime Contractor of its detailed schedule. However, it noted that the schedule was achievable, provided that there were suitable contractual arrangements to protect the Commonwealth from further loss from delay.

74. DMO conducted a Gate Review in August 2011 to consider the outcomes of the 2011 negotiations and whether the project warranted a return to the Projects of Concern list.59 The review noted the new schedule was a low-medium risk, and that ‘the way ahead to complete the project is clear’.

75. The 2011 renegotiation resulted in financial and schedule concessions by Defence, with the Prime Contractor also withdrawing $5 million in postponement claims that were open to dispute. The circumstances which put DMO in a position where it could not confidently contest the counter-claims made by the Prime Contractor in reaching the August 2011 agreement, can be traced in large part to the 2007 global settlement. By not scrutinising the feasibility of the 2007 global settlement delivery schedule at the time, DMO agreed to an unrealistic production schedule, with delays evident well before renegotiations began in 2010.60

76. There does, however, appear to have been benefits in improving the clarity of certain contractual requirements. DMO was also able to ensure that the improved production rates—evident since November 2010—have been sustained since then, including during the negotiation process. Defence informed the ANAO in March 2012 that in undertaking these negotiations:

Defence’s requirement was to get the vehicles as quickly as possible, while keeping the [Prime] Contractor motivated to perform. Accordingly, a commercial ‘win/win’ solution was required, irrespective of the contractual issues—which were subject to interpretation by both parties.

Analysing and reporting on project progress

77. Overall, there has been a lack of detailed analysis of schedule by DMO over the course of the major upgrade project. As noted in paragraph 62, Defence was not able to provide any contemporaneous analysis of the feasibility of the delivery schedule agreed as part of the 2007 global settlement. There has also been a reliance on the Prime Contractor’s reported performance, including projected performance, without sufficient independent verification. It was not until June 2010 that senior-level meetings were held between DMO and the Prime Contractor to deal with production delays—at around the time that accumulated schedule variance reached its lowest point.

78. Over the life of the project, reporting to senior decision-makers within Defence and government has not always presented an accurate picture of the current and likely future performance of the M113 upgrade project. Part of this has been the practice of only reporting against revised contract due dates without reference to original project intentions. Additionally, there has been a lack of appropriate schedule analysis by DMO throughout the later stages of the project. A lack of detailed understanding of project progress and schedule issues has been an ongoing feature of this project. Project reporting is an important component of management and accountability processes and every effort should have been made to ensure that they provided clear and accurate advice on the extent of delays in the project, and their implications.

79. Advice to government following the 2007 global settlement has frequently contained incorrect and/or unrealistic advice on project progress and projected performance (this advice is analysed in Table 4.2).

Chapter 5 – M113 capability

80. Defence defines capability as ‘the capacity or ability to achieve an operational effect. An operational effect may be defined or described in terms of the nature of the effect and of how, when, where and for how long it is produced’. Capability development within Defence is not based solely on the acquisition of hardware, such as the upgraded M113. Rather, it involves the combination of multiple personnel, equipment and support system inputs.

81. These inputs are set out in Defence’s Fundamental Inputs to Capability (FIC) framework61 which enables Defence to effectively deploy and sustain its forces. In considering the capability of the upgraded M113, the ANAO examined the four elements of the FIC relevant to the current stage of the vehicle’s production and introduction into service: major systems; facilities; supplies and support.62

82. The major systems component of the FIC for the M113 upgrade project is the M113 vehicle, and its availability is a key issue from a capability perspective. Availability has two broad dimensions in this circumstance — the day-to-day availability of upgraded vehicles for their intended use, and the broader impact on capability of any failure to deliver upgraded vehicles in the first place.

83. In examining the first dimension, the ANAO analysed vehicle availability data from the School of Armour, currently the most frequent and consistent user of the vehicle.63 Maintenance records classify the vehicles as ‘Fully Functional’; ‘Restricted Use’; or ‘Unserviceable’. Over the three years to December 2010, the proportion of vehicles at the School of Armour classified as ‘Fully Functional’ decreased from an average of 62 per cent in 2008 to 38 per cent in 2010. Since 2010, this has not improved: Defence advised that as at 19 March 2012 the proportion of vehicles classed as ‘Fully Functional’ was 39 per cent across Army. The main factors affecting vehicle availability have been a lack of supplies (spare parts) and mechanical failures.

84. Defence has established adequate facilities to maintain and operate the vehicles, and 7 RAR’s move to Adelaide from Darwin in February 2011, allows the Battalion to take advantage of training areas which are not affected by the tropical climatic limitations of Darwin. The School of Armour also houses adequate facilities to provide training programs to M113 crews.

85. In terms of the second dimension of availability set out in paragraph 82, there has been considerable delay to the vehicles’ design and production schedule. Defence estimates that the final vehicle will be delivered by December 2012.

86. In addition to the impact on capability resulting from production delays, the vehicles’ overall capability is currently impacted by a lack of adequate communications equipment and logistical support. The M113 relies on the VIC 3 model communications harness as its main electronic communication system. There are currently a limited number of these harnesses available, and priority for these harnesses is given to the ASLAV vehicles, currently deployed to Afghanistan, which also share the VIC 3 platform. Army aims to rectify this shortage by December 2012 through fitting the Bushmaster fleet (some of which use the Vic 3 harness) with updated SOTAS communications systems, which will make an increased number of VIC 3 harnesses available for the upgraded M113 fleet.

87. Moreover, the electronic systems fitted to the upgraded vehicles do not permit optimal communication and data transfer with heavy tanks and the other force elements, such as artillery and aircraft, with which they are intended to operate. These electronic systems are to be replaced by new battle space communications systems currently under development, which are scheduled to deliver new equipment in 2013, initially to infantry. Army originally expected to address the current communications limitations of the M113 by fitting to these vehicles the systems to be developed under projects LAND 75 and LAND 125.64 However, in the context of the 2012-13 Federal Budget, the relevant phases of the linked projects, Land 75 and Land 125, that were to deliver these capabilities into the upgraded M113 vehicles will not now proceed. Defence informed ANAO that consideration will be given to including the installation of these capabilities in the upgraded M113s under later phases of these projects.

88. There are also restrictions transporting the upgraded vehicles using the ADF’s native land, and air transport:

- C17 transport aircraft: Chief of Army informed ANAO that a single CI7 has the capacity to carry up to four upgraded M113s, although the full air transportability certification process is still to be completed.

- C130 transport aircraft: Chief of Army also informed ANAO that a single upgraded M113 can be transported by a C130, although ‘significant preparation of the aircraft is required and significant limitations on aircraft air-land performance would be imposed’. ANAO notes that the initial testing for loading the vehicle into a C130 occurred in March 2006. However, as at March 2012 certification for this procedure had yet to be achieved.

- Land transport: Army is able to utilise the heavy tank (M1A1 Abrams) transport capability of its Armoured battalions, and lease commercial vehicles to transport the upgraded M113s by road. The heavy trucks necessary for the mechanised infantry battalions to transport M113s are to be acquired under Phase 3 of the LAND 121 project. While the preferred tenderer for the medium heavy vehicles was announced in December 2011, no date has been announced for delivering this capability.

89. In addition, ANAO was informed that upgraded M113s can be transported by sea aboard Navy’s two currently available transport ships, HMAS Tobruk and HMAS Choules. However, this capability has yet to be tested. Capacity to move the vehicles by sea will increase with Phase 5 of Joint Project 2048, when the Canberra class helicopter landing dock vessels currently being constructed receive their landing craft. This is currently scheduled for 2017.

90. In summary, at the upgrade project’s commencement, and throughout its life, there has been insufficient consideration by Defence of the FIC elements required for the upgraded vehicles to contribute as planned to Army’s close-combat operations. With the project nearing completion, Defence has identified limitations with the vehicles’ ability to communicate and be transported. Some of these limitations will not have been fully addressed by the time all 431 vehicles are scheduled to enter service in December 2012. There remains a fundamental challenge for Defence’s senior leadership, when upgrading or developing a major system such as the M113, to coordinate all elements of the related FIC to avoid significant limitations to capability developing, as in the case of the upgraded M113.

91. In comparison with vehicles currently in use with other armed forces, the upgraded M113 lacks firepower and other vital capabilities. Although superior to its predecessor, a vehicle that was considered fit-for-purpose when the minor upgrade was first proposed 20 years ago now lags behind other armoured infantry vehicles, and is vulnerable in many current threat environments. This state of affairs was acknowledged by the Acting Chief of Army in December 2011:

It is important to note that while the M113AS4 (the upgraded M113) is a capable combat vehicle, it does have constraints and limitations through design and capacity as it is based on the M113A1 hull. This factor limits its potential in comparison to higher order platforms including current generation IFV (infantry fighting vehicles). This fact essentially provides a capability gap for the conduct of mounted close combat operations across the spectrum of conflict until the introduction into service of the Land Combat Vehicle System (Land 400).

92. In response to the draft audit report, in April 2012 the Chief of Army provided clarifying comments on the use and meaning of the term ‘capability gap’:

The term refers to the difference between a stated capability requirement and Army’s ability to fulfil that requirement … While the existing level of protection of the [upgraded M113] is high, analysis shows that the vehicle’s major limitation will be its ability to support close combat operations against an enemy which is capable of employing a broad variety of conventional and unconventional methods of attack.65

93. The Chief of Army also noted that:

as the Capability Manager … I am satisfied that the [upgraded M113] provides a significantly enhanced capability to Army and that it is a potent and capable platform. I am also satisfied that the delivery of [the upgrade project] satisfies the original requirement specified by the Capability Manager.

Agency response

94. Defence’s response to the report is as follows:

Defence acknowledges this third Australian National Audit Office audit of the delivery of this particular capability. The audit report outlines the challenges that Defence and the contractor have experienced with the delivery of the Upgrade to the M113 Armoured Vehicle (LAND 106) project, but does not recognise the recent project deliverables and the importance of this capability to Defence.

In forming this observation, Defence notes that many of the improvements that the ANAO has suggested in previous audits, and to a lesser extent in this audit, are now in place or in the process of being implemented across Defence. Following the implementation of some of these improvements, Defence notes that, after overcoming some very challenging technical and commercial issues, the M113 project performance has significantly improved over the last year and is delivering the vehicles within the approved project budget and within the approved scope. Importantly, there are less than 70 vehicles to be delivered and the contractor is meeting the contract schedule for final delivery.

Conversely, Defence does acknowledge that a number of aspects of this project have not gone well over the life of the project and also acknowledges that there have been substantial delays during the project's life-cycle. Additionally, the ANAO correctly notes that Defence and the Contractor had been unduly optimistic regarding their ability to regain schedule and this optimism negatively impacted accurate project reporting. A major lesson learned by Defence is that, through the established reporting methods, senior management stakeholders, and Government should have been given a more accurate and frank picture of the status and risks to the project between 2007 and 2010. Since 2010, Defence has initiated additional assurance mechanisms to reduce the risk of this occurring again.

Capability Issues Raised in the Audit

During the course of this audit, Defence has highlighted the importance of the four capability enhancements provided by the M113AS4 including mobility, lethality, protection and communications. Furthermore, Defence has highlighted that the Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) variant is the primary platform necessary for conducting mounted close combat. Moreover, the M113 platforms combine to provide a key capability within Army's Combined Arms Fighting System (CAFS).

In light of recent announcements regarding the placement into storage of various components of Army's mechanised systems, and specifically the M113,66 Defence notes that this action is entirely related to the recent cuts to the Defence budget announced by the Government and the associated need to reduce operating costs in order to focus key resources to operational priorities and linked training support.

Footnotes

[1] The AF repairs vehicles in the field; the ARVL recovers vehicles from the field; the ALV transports equipment and supplies; the AA transports wounded troops; the ACV provides a field command post and communications hub; and the AM provides transport and support of an 81mm mortar.

[2] Land 400—Land Combat Vehicle System (LCVS)—is a replacement of the M113, Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle and the Australian Light Armoured Vehicle (ASLAV). Defence describes the current Land 400 project as: ‘the Army’s largest, most expensive [currently expected to be greater than $10 billion] and most complex major capability equipment project to date. The project aims to deliver the mounted close combat capability to the Land Force from 2025. LAND 400 will provide an integrated suite of land combat vehicle systems to fill the mounted close combat capability gap that is partially being enabled by a number of disparate existing light armoured vehicle fleets. The Land 400 Initial Operational Capability (IOC) is planned for 2025–26 and is currently planned to be one Armoured Cavalry Regiment of Land Combat Vehicle Systems (LCVS). Given the early stage of the project, the IOC is expected to become more defined as options to meet the capability requirement are sourced through the First to Second Pass process’.

[3] The full title generally used by Defence for the project in current publications (including on its internet sites) is ‘Upgrade of M113 Armoured Vehicles LAND 106’. In this report it is generally referred to as the M113 upgrade project.

[4] The details of the changes in scope that occurred between 1992 and 2002, and the reasons put forward for them, are examined in detail in ANAO Report. No.3 2005-06, Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project.

[5] Tenix Defence was also the Prime Contractor engaged to undertake work during the 1990s in connection with the minimum upgrade project for the M113s.

[6] Tenix Defence is referred to as the original Prime Contractor in this report and BAE Systems is referred to as the Prime Contractor.

[7] This estimate included all upgrade costs, three years of spares and contingency.

[8] Tenix Defence was also the original Prime Contractor for the CSP Contract which BAE Systems took over with its June 2008 purchase of that company.

[9] In the case of the upgraded M113 fleet, the personnel and operating costs estimate includes the costs of operating and maintaining the un-upgraded fleet until the final vehicles were withdrawn in 2010, and the upgraded fleet, from 2002–03 until the upgraded vehicles are withdrawn from service commencing in 2025–26. In addition, it includes the cost of items such as vehicle fuel, ammunition, spare parts, maintenance services and supply services, as well as the cost of decommissioning the vehicles at the end of their life.

[10] As at March 2012, 356 vehicles were delivered to Defence. Of these, 252 had been delivered to

1 Brigade, 24 to the School of Armour and 12 to other units. The remainder are in storage awaiting delivery to units.

[11] Department of Defence, Defence Capability Development Handbook, Canberra, August 2011, p. 2.

[12] ‘LAND 106’ is Defence’s project code for the M113 upgrade project.

[13] The vehicles were originally expected to be withdrawn from service in 2020. In March 2012, Defence informed the ANAO that the vehicles are now planned to be progressively withdrawn from service from 2025 with the last of the vehicles expected to leave service around 2030.

[14] Audit Reports No.3 2005–06 Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project and No.27 2008–09 Management of the Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project.

[15] By August 2009, the total number of vehicles contracted to be delivered by December 2010 had been reduced to 329 vehicles. This was a result of the decision to extend the 21 Armoured Mortar(AM) variant vehicles (see paragraph 52). The additional work required as a result of this decision led Defence and the Prime Contractor to agree a contract amendment that pushed the scheduled delivery date of these vehicles past the December 2010 deadline.

[16] The 2005–06 audit reported that the upgraded M113 was originally expected to progressively enter service between 2006 and late 2010 but that there was doubt as to whether the upgraded vehicles would meet this in-service date. At the time, the original Prime Contractor was also commencing production of vehicles at its own risk before they had passed formal testing by Defence. The audit report noted that ANAO considered this approach involved a high level of risk for the delivery of Army capability and that, notwithstanding the Prime Contractor’s liability for this risk, it would require close management by both the Prime Contractor and Defence. Audit Report No.3 2005–06 Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project p.14.

[17] The incentive payment of $2.716 million was an amount equivalent to the liquidated damages that had been received by Defence as ‘work in kind’ under the 2007 global settlement.

[18] The Prime Contractor’s intention to open the additional facilities in Williamstown and Wingfield was announced as part of the Government’s decision in October 2008 to purchase an additional 81 APCs.

[19] See paragraph 52.

[20] Contract Change Proposal (CCP) 205. Defence informed ANAO in March 2012 that: ‘the main reason for CCP 205 was to provide incentive payments to ensure the [Prime Contractor’s] additional production facilities were not closed early to reduce the [Prime Contractor’s] costs. This removed the threat of further schedule delay that could have moved production out by another 12 to 18 months. This was a prudent risk reduction strategy initiated by DMO’.

[21] The 2008–09 audit reported that meeting the compressed delivery schedule agreed in the 2007 global settlement depended on a smooth flow of hulls and vehicles through the Defence-owned facilities at Bandiana operated by the Prime Contractor. However, during a visit to Bandiana in August 2008, ANAO observed a backlog of work, indicating that schedule risks previously identified by Defence had been realised. The backlog was caused chiefly by delays in extending the hulls. This was proving more complex than anticipated and was taking longer than expected.

Audit Report No.27 2008–09 Management of the Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project p.19.

The report also outlined Defence’s investigation of a different hull extension process from that finally adopted. See pp. 69 to 72.

[22] ANAO Audit Report No.27 2008-09 Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project, pp. 35, 53-54, 65-69, 80-81, 84 and 88.

[23] As indicated in paragraph 4, the costs of preparing and extending the hulls of the 350 vehicles originally ordered in 2002 are not funded under the Major Upgrade Contract but are rather funded by Army sustainment funding under another contract with the same contractor (the Commercial Support Program (CSP) Contract).

[24] In 2001, when seeking government approval for the project, Defence advised that the impact on personnel and operating costs of this project would be cost-neutral, on the basis that the larger M113 fleet would be withdrawn and replaced with a smaller fleet of upgraded vehicles. As discussed at paragraph 3.11 in this report, this has not proved to be the case and the upgraded fleet will incur substantial additional personnel and operating costs over its planned life to 2025.

[25] As noted in paragraph 3, the Government approved the acquisition of an additional 81 upgraded APCs in October 2008 at a cost of $222.1 million as part of the ELF initiative. This approval was on the basis that the extra vehicles would be produced after the original 350 vehicles ordered in 2002.

[26] Negotiation Deed of Agreement between Defence and the Prime Contractor, August 2011.

[27] The Prime Contractor’s postponement claims covered four key issues: laminar cracking on M113 hulls (see paragraph 64); missing or broken lifting eyes on the hulls (see paragraph 69); delays caused by the AM extension; and facility failures at the Bandiana production facility, which is owned by Defence. These facility failures included: insufficient compressed air supply, water contamination in compressed air supplies, insufficient power for additional welding bays, breakdown of grit blasting equipment and cranes, and the breakdown of the machinery used for extending the hulls.

[28] The total incentives of $2.8 million are potentially available to the Prime Contractor under the amendment to the Major Upgrade Contract. These comprise four quarterly incentive payments of $400 000 each for meeting prescribed production targets and a final acceptance incentive of $1.2 million if all 431 vehicles are delivered by 31 October 2012. See Table 4.1 for further details of the timing and nature of the targets and incentives.

[29] In August 2009, the Government approved the extension of the last unextended variant, the Armoured Mortar (AM), at a cost of $17.1 million, and the resulting contract amendment pushed the completion date for the last vehicle out to April 2012.

[30] See Table 4.2

[31] An initial prepayment (or mobilisation payment) of $4.21 million was made to the Prime Contractor in May 1997 in connection with the then contract for a minor upgrade of the M113 fleet. Defence advised that this prepayment had been recovered in full by November 2007. Three prepayments have been made under the Major Upgrade Contract ($40 million in 2002, $40 million in 2007, and $16.2 million in 2008). Each of these later payments were in October 2001 base date dollars and are to be amortised across the remaining life of the contract from the point they were made.

[32] ANAO notes that the upgraded M113 is not an isolated case. In this context, another recent instance where coordination of essential inputs to capability has been less than optimal was the sub-standard maintenance of the Navy’s heavy-lift ships. The logistic underpinnings of materiel systems are integral to achieving capability and require attention throughout the capability life cycle.

[33] Minute to ANAO from the Acting Chief of Army, 19 December 2011.

[34] The Acting Chief of Army’s full response appears in Appendix 3 of this report.

[35] The Chief of Army’s full response appears in Appendix 4 of this report.

[36] See ANAO Audit Report No.27 2008–09 Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project, p. 27.

[37] At the time of the 2008–09 audit, Defence intended LAND 400 to begin replacing M113s and ASLAVs from around 2015.

[38] See ANAO Audit Report No.27 2008–09, Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project, p.87.

[39] This advice was provided in connection with DMO’s proposal that the Land 106 – M113 Upgrade Project be removed from the Government’s Projects of Concern list.

[40] The hulls of 259 of the 350 M113s ordered in 2002 were originally planned to be extended comprising 171 APCs, 38 AFs and 50 ALVs.

[41] In its business case to government, Defence identified several benefits from extending the AM variant. These included improving the firing position of the mortar, savings in long-term maintenance, and facilitating future upgrades of communication systems and mortars.

[42] In seeking approval for extending the AM, Defence advised Government that the technical and cost risk was ‘low’. However, because of the age and wear and tear on the AMs, the hulls require additional repair work, the cost of which is borne under the uncapped Commercial Support Program (CSP) Contract. The schedule risk presented by extending the AM was assessed by Defence as ‘low – medium’, lower than the ‘medium’ risk of not extending the mortar. This advice to government was based on a production rate that Defence had acknowledged six months earlier was unachievable. In addition, the final contracted delivery date was extended at that time from December 2011 to

April 2012, and the vehicle delivery schedule was rearranged to provide the AM variants last, despite Army’s preference to have the vehicles as early as possible. Defence informed ANAO that the decision to produce the AMs last was based on the increased work involved in their production.

[43] Audit Report No. 27 2008-09, Management of the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade Project, Recommendation No.1 and paragraphs 2.28 to 2.30, pp. 56-57.

[44] Personnel and operating costs include the cost of Army personnel to operate and maintain the vehicles, and the materiel sustainment costs such as spare parts and servicing.

[45] The total estimate is comprised of the costs of maintaining and operating the non-upgraded fleet from 2002–03 until their withdrawal in 2010 and the upgraded fleets from 2002–03 until their planned withdrawal from service in 2025, including items such as vehicle fuel, ammunition, spare parts, maintenance services and supply services, as well as the costs of de-commissioning the vehicles at the end of their life.

[46] The accumulated schedule variance line measures performance against the 2007 global settlement schedule and the schedule advised by Defence at the conclusion of the 2008–09 audit. If schedule variance is measured against subsequent rebaselined contracts, which includes those for the additional 81 vehicles and the extension of the mortar variant, the low point of schedule slippage would be February 2010, with $30 million of scheduled work not being delivered.

[47] Not all of the 171 original APCs in the first tranche of 350 vehicles were to be out-fitted with appliqué armour but all 81 ELF APCs are.