Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Transport Services for Veterans

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs administration of the Repatriation Transport Scheme.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS or the Scheme) is a well-established program introduced by the Australian Government in 1986 to assist eligible veterans1 attend medical appointments.2 Administered by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA), the RTS has three primary components: travel reimbursement; the Booked Car Scheme (BCS); and ambulance services. Travel reimbursement was the initial support component of the RTS and involves DVA paying veterans for travel expenses they have incurred, including the cost of a medically required attendant. The BCS was introduced in the early 1990s as an additional support measure to assist frail veterans aged 80 and over, and involves DVA arranging and paying for taxi, hire car, or long distance travel.3

2. In 2013–14, the department processed around 160 000 claims for travel reimbursement at a cost of $21.4 million, and organised over one million trips to and from medical appointments through the Booked Car Scheme, at a cost of $64.4 million.4 In 2014–15, the department budgeted $191 million for the RTS as a whole with projected expenditure estimated to increase by an average of $4 million per annum over the next three years. This growth can be attributed to increasing use of ambulance and Booked Car Scheme services, particularly by the ageing cohort of Second World War veterans.

3. In its administration of the RTS, DVA draws on funding from the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 Special Appropriation. The principal basis for reimbursing travel expenses is under Section 110 of the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 (VEA)5, and the circumstances and amounts of travel assistance payable under the RTS are set out in the Veterans’ Entitlements Regulations 1986. For the Booked Car Scheme, DVA arranges and pays for travel for frail and aged veterans under sub-sections 84(1) and 84(2) of the VEA. In contrast to travel reimbursement arrangements, the Act and Regulations do not provide any further description of the Booked Car Scheme, and details of these arrangements are based on departmental policy and rules.

Previous audit coverage

4. ANAO Audit Report No.6 2002–03 Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Veterans’ Affairs examined fraud control arrangements across DVA including the RTS. The audit concluded that DVA had no systematic approach in place, or a quality assurance process, that would assist in identifying claim anomalies and potential fraud. The ANAO recommended that: ‘DVA take action to standardise travel allowance claim procedures and documentation under the RTS to be consistent with the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 and its Regulations’. The department agreed to the recommendation, acknowledging that there was a need to introduce a national quality assurance system for travel payments.6 As part of the department’s response to the recommendation, a quality assurance framework for the RTS was introduced in 2006 and operated until May 2012. Recent changes to quality assurance are examined in this performance audit.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) administration of the Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS).

6. To form a conclusion against the audit objective the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- DVA administers the RTS in accordance with legislation and relevant guidelines;

- DVA has implemented systems and processes to provide authorised transport services and travel reimbursements to eligible clients in an accurate and timely manner;

- DVA has procured transport services in accordance with relevant guidelines and effectively manages relevant contracts; and

- DVA effectively monitors and reports on performance to inform its delivery of the RTS.

7. The ANAO did not examine DVA’s administration of funding to state and territory governments for the provision of ambulance services under the RTS.

Overall conclusion

8. The Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS or the Scheme) was introduced in 1986 to assist eligible veterans to attend medical appointments. Assistance is provided through: the reimbursement of costs incurred for travel; a Booked Car Scheme (BCS); and ambulance transport in some circumstances. Veterans seeking travel reimbursement tend to be younger and can generally make their own travel arrangements, while the Booked Car Scheme is intended to assist aged and frail veterans with higher levels of need through contracted transport providers. In 2013–14, DVA processed around 160 000 claims for travel reimbursement at a cost of $21.4 million and organised over one million trips under the Booked Car Scheme, using over 300 contracted transport providers at a cost of $64.4 million. The department has budgeted $191 million for the RTS in 2014–15 and anticipates that expenditure will increase by approximately $4 million annually over the next three years.

9. Overall, DVA’s procurement and delivery of services to veterans under the RTS has been generally effective. The department provides transport services to many thousands of veterans on a daily basis, has reported consistently good performance against its targets for processing travel claims, and receives relatively few complaints relating to travel bookings arranged by the department. Further, DVA’s procurement of transport providers in 2011–12 introduced a more competitive pricing structure across a national network of transport service providers, and the department has actively managed its contracts with transport providers to maintain service quality. However, there remains scope for improvement in the RTS control framework to enhance the level of confidence regarding the validity and accuracy of travel claims and bookings.

10. In 2013–14, DVA reported that 93 per cent of all travel reimbursement claims were processed within the 28 day target7,8 and a consistently low level of complaints was recorded in relation to travel reimbursement claims and travel bookings arranged by the department.9 To effectively deliver the BCS, the department undertook a national procurement exercise in 2011–12 with a view to introducing a level of competition between transport providers and achieving better value for money outcomes. DVA subsequently entered into contracts with over 300 taxi and hire car providers, and has actively managed the agreements so as to maintain services at specified levels.

11. The department has also sought to improve services to veterans through the introduction of online claiming for the reimbursement of travel costs. As part of that process, in 2012 DVA removed key safeguards against fraudulent or incorrect payments—specifically the requirement for veterans to submit receipts with travel claims and the need for health providers to formally endorse the necessity for travel to a medical appointment. While the risks associated with the removal of these core payment controls were identified at the time, the department failed to implement its planned mitigation measures—the introduction of post-payment monitoring and enhanced quality assurance processes—and the risks remained largely untreated for three years.

12. During the course of this audit, DVA revised its quality management framework for travel claims reimbursement to include a process for monitoring the validity and accuracy of payments once they have been made. Implementation of the revised quality management framework is at an early stage, and in light of past experience the department should review its overall approach to implementing the planned initiatives so as to provide management assurance that agreed risk mitigation measures will be progressed and will operate as anticipated.

13. The administration of payments to contracted transport providers under the BCS is supported by appropriate controls built into the relevant ICT system, known as the Transport Booking and Invoicing System (TBIS). However, two older booking methods under the BCS—the Direct Booking Model and NSW Country Taxi Voucher Scheme—continue to operate outside the TBIS control framework. In particular, bookings are not made through TBIS and DVA staff cannot conduct normal pre-travel eligibility checks or provide travel approvals, and the department only becomes aware that travel has been undertaken when an invoice is received. The annual cost of bookings made through these methods is approximately $16 million, or one-quarter of the value of all bookings under the BCS. To strengthen the level of assurance that BCS requirements are met, there would be benefit in the department also applying the post-payment monitoring capability for travel reimbursement, currently under development, to the BCS.

14. A key lesson of this audit is the importance of senior management oversight and monitoring of planned implementation activities, and timely escalation when implementation risks emerge. As mentioned, in the course of implementing online service improvements in 2012, DVA failed to implement planned risk mitigation measures to help maintain the integrity of travel claims under the RTS. The ANAO has made one recommendation focusing on the provision of management assurance relating to the implementation of agreed risk mitigation measures.

Key findings by chapter

Travel Reimbursement (Chapter 2)

15. In May 2012 DVA removed a number of controls for travel reimbursement claims processing—including the reconciliation of reimbursement claims against receipts and endorsement by health providers of the need to travel—as part of its development of online claiming by veterans. At the time, the department identified a number of potential risks prior to the implementation of online claiming, such as increased non-compliance by clients, and proposed a number of risk mitigation measures. The measures included post-payment monitoring and enhanced quality assurance processes.10 However, the planned measures were not implemented in a timely manner, and the identified risks remained largely untreated for almost three years.

16. During the course of the audit DVA was developing its capacity to review the validity and accuracy of payments to reimburse travel, through revisions to the RTS quality management framework. Implementation of the revised framework is at an early stage, and the department should review the overall implementation approach to provide management assurance that the agreed risk mitigation measures will be progressed as planned, and will operate as anticipated. For instance, the appointment of a senior responsible officer and the development of a project implementation and risk management plan11 would contribute to the successful introduction of planned post-payment monitoring arrangements and enhanced quality assurance. There would also be benefit in DVA considering the introduction of internal performance measures to help monitor the operation and effectiveness of these arrangements.

17. The ANAO’s controls testing of the travel reimbursement processing system, known as the Repatriation Transport Claims Processing System (RTCPS), identified shortcomings in relation to: the absence of post-payment monitoring; quality assurance arrangements; ad hoc confirmation of distances claimed; and a lack of clarity regarding the period that receipts must be retained by veterans to facilitate checking by DVA. For instance, receipts for claims over $30 are only required to be kept for four months, which may limit the department’s capacity to check receipts as part of the post-payment monitoring arrangements currently being planned.

Booked Car Scheme (Chapter 3)

18. In 2011–12, DVA undertook a competitive national procurement exercise which resulted in the establishment of contracts with over 300 taxi and hire car providers to provide transport services under the Booked Car Scheme. The department set out to introduce a level of competition between transport providers so as to deliver value for money outcomes. While DVA’s tender and evaluation processes were generally sound, there remained scope for improvement in two areas, specifically: maintaining adequate records for the Tender Steering Committee; and the completion of conflict of interest disclosure statements for all members of relevant committees involved with evaluating tenders.

19. The department actively manages its Booked Car Scheme transport provider contracts to maintain adequate services for veterans. In particular, ongoing communication with contracted providers has contributed to effective service delivery by helping the department develop an understanding of service providers and the environment in which they operate. DVA has also acted promptly to amend contracts and booking allocations in response to frequent changes in taxi and hire car ownership arrangements—for example when existing contractors leave the transport industry or the owners of contracted companies change.

20. The introduction of automated booking arrangements in 2011 was expected to result in savings of $1.35 million per annum from a reduction in manual processing of tasks. However, DVA assessed that the changes delivered less than $25 000 in the first year after implementation. In particular, the 30 per cent target for uptake of the online bookings by service providers was not realised, with only 313 out of a possible 90 000 health providers (0.35 per cent) utilising the system by November 2012. The department has acknowledged that a key factor in the low take-up was insufficient consultation with health providers.

21. The Booked Car Scheme Transport Booking and Invoicing System (TBIS), has in-built system controls which are generally effective in supporting the integrity of transport bookings and associated payments to transport providers. In particular, controls built into this system assist staff in making soundly based assessments of eligibility, allocating bookings to transport providers according to predetermined percentages, and complying with program rules such as travel being to the ‘closest practical provider’ to the veteran. The manual and automatic checks established through TBIS provide a reasonable level of assurance that transactions are processed and recorded accurately.

22. However, two older BCS booking methods—the Direct Booking Model and the NSW Country Taxi Voucher Scheme—currently operate outside the control framework of TBIS.12 As bookings are not made through TBIS, DVA staff cannot undertake the regular manual and automatic checks discussed in paragraph 21, and the department only becomes aware that travel has occurred after receiving an invoice. The annual cost of bookings made through these methods is approximately $16 million, or one-quarter of the value of all BCS bookings, and the payment integrity risks relating to these booking methods merit review by the department. To strengthen the level of assurance that BCS requirements are met, there would be benefit in the department also applying the post-payment monitoring capability for travel reimbursement, currently under development, to the Booked Car Scheme.

Performance Monitoring and Reporting (Chapter 4)

23. The department reports against two key performance indicators (KPIs) in its annual report in respect to travel for treatment—timely processing of claims and the percentage of complaints. In 2013–14, DVA reported that 93 per cent of all travel reimbursement claims were processed within the 28 day target13, and performance against the target was between 89 and 100 per cent from 2010–11 to 2013–14. Further, a consistently low level of complaints was reported in relation to travel bookings arranged by the department, ranging from 0.02 per cent to 0.05 per cent from 2010–11 to 2013–14.

24. While the current KPIs provide an indication of the overall quality of travel services delivered by DVA, payment accuracy is also an important measure for the department and its clients. There would be benefit in the department considering the development of a performance measure for the accuracy of claims processing, in the context of implementing revised performance reporting arrangements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.14

25. DVA has access to reliable information on travel reimbursement through the RTCPS, and operational information on transport service providers from TBIS. However, the department has recognised that while these systems provide valuable operational data, they do not provide reliable information for effective internal monitoring of key trends in program performance. The recent completion of the Transport Business Intelligence Reporting Project (TBIRP) provides the department with the means to generate meaningful internal reports on key trends and will also contribute to post-payment monitoring.

Summary of entity response

26. The Department of Veterans’ Affairs provided the following summary response to the audit report. The formal departmental response is included at Appendix 1.

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs notes the findings of the report and agrees with the recommendation suggested by the Australian National Audit Office.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.25 |

The ANAO recommends that DVA review its approach to the implementation of post-payment monitoring and enhanced quality assurance arrangements for the Repatriation Transport Scheme, to provide management assurance that the planned measures—intended to improve the level of confidence of the validity and accuracy of travel claims and bookings—will operate as anticipated. DVA response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the Repatriation Transport Scheme’s purpose, legislative framework and operation. It also describes the audit objective, scope and criteria.

Background

1.1 The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) is responsible for developing and delivering programs that assist the veteran community, including health and related support services. The Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS or the Scheme) provides eligible veterans15 and their medically required attendants with financial assistance when travelling to approved medical treatment. Under the RTS, financial assistance is provided towards the cost of transport, meals and accommodation.

1.2 Eligible veterans have either ‘gold card’ or ‘white card’ access to government funded health services. Veterans who qualify for gold card access are eligible for financial assistance towards travel for treatment of all health conditions; whereas white card holders are only eligible for financial assistance for specific medical conditions accepted by DVA. Dependants of eligible veterans and approved attendants may also qualify for transport assistance under the RTS.

1.3 The RTS has three components: travel reimbursement, the Booked Car Scheme16, and ambulance services.17 The RTS is a well-established program, with travel reimbursement introduced through the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 (VEA)18 and the Booked Car Scheme evolving out of COMCAR19 in the early 1990s.

Administrative arrangements

Legislative framework

1.4 The RTS has a statutory basis. Section 110 of the VEA is the principal basis for reimbursing travel expenses under the RTS20, and the Veterans’ Entitlements Regulations (Regulation 9) detail the circumstances and amounts of travel assistance that may be paid.21

1.5 DVA arranges and pays for travel for frail and aged veterans through the Booked Car Scheme22, under sub-sections 84(1) and 84(2) of the VEA. In contrast to the travel reimbursement arrangements described above, the VEA and Regulations do not provide any further description of the Booked Car Scheme or long distance transport booked by DVA under the RTS. Details of these arrangements are based on Repatriation Commission and departmental policy and rules.

Program components

1.6 Travel reimbursement was the original focus of the RTS when it was introduced in 1986 and is available to all eligible veterans who hold a VEA white or gold card. Veterans seeking travel reimbursement tend to be younger and can generally make their own travel arrangements, using either a private vehicle or public transport. Veterans subsequently claim reimbursement of travel and related expenses from DVA. If a veteran declares that their medical condition prevents them using a private vehicle or certain types of public transport, they may be reimbursed for taxis, community transport or air travel.23 The department provides a contribution towards the cost of attending medical treatment, and may not cover all costs incurred by the veteran. The amount reimbursed is determined by travel reimbursement processing staff, who must consider whether the veteran has used the most economical means of attending treatment.24

1.7 The Booked Car Scheme was introduced to assist aged veterans with higher levels of need. Under the Booked Car Scheme, the department may arrange and pay for a taxi, hire car, or long distance transport (generally by plane). There are no out-of-pocket expenses for eligible persons, although allowances for associated meals and accommodation must be claimed using a DVA claim form.25 Given that a large proportion of eligible veterans are now over 80 years of age, the number of Booked Car Scheme trips now exceeds the number of claims for travel reimbursement, and the Booked Car Scheme has become the primary focus of the RTS.

1.8 The Booked Car Scheme was changed in 2007 to allow health providers to book transport directly with DVA contracted transport providers in certain areas (predominantly metropolitan). This arrangement is referred to as the Direct Booking Model (DBM) and was implemented as a workload risk mitigation strategy in response to Repatriation Commission26 and Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission decisions to extend the Booked Car Scheme for transport to local medical officers (general practitioners) and allied health professionals for gold card holders aged 80 years and over. In NSW country areas, the Booked Car Scheme includes the New South Wales Country Taxi Voucher Scheme (CTVS), which requires veterans to arrange their own taxi or hire car transport and obtain a DVA issued taxi voucher from their health provider to pay for transport.

Usage and expenditure trends

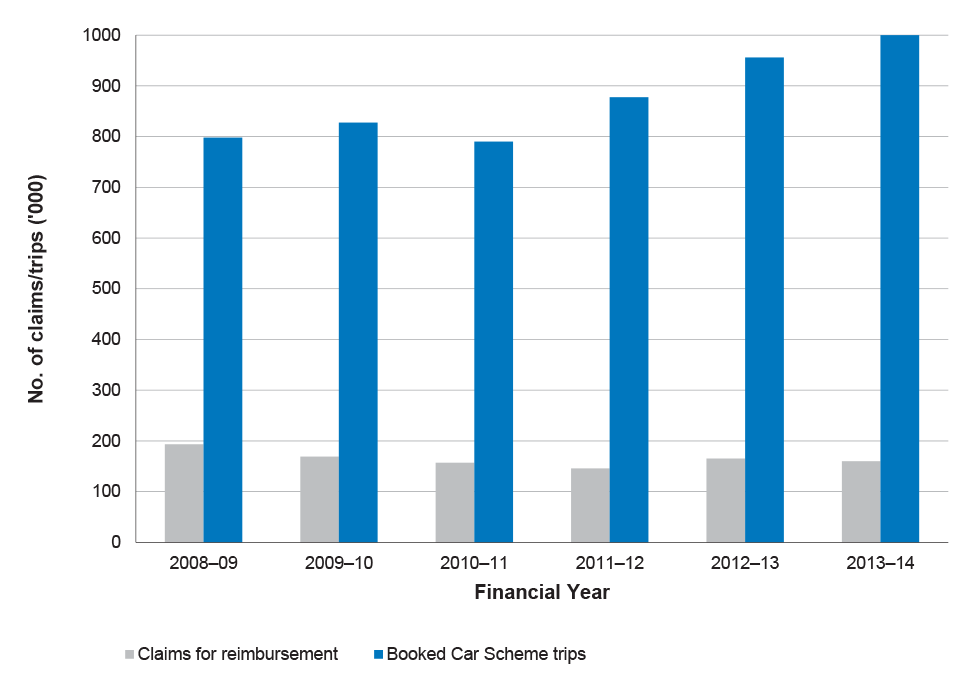

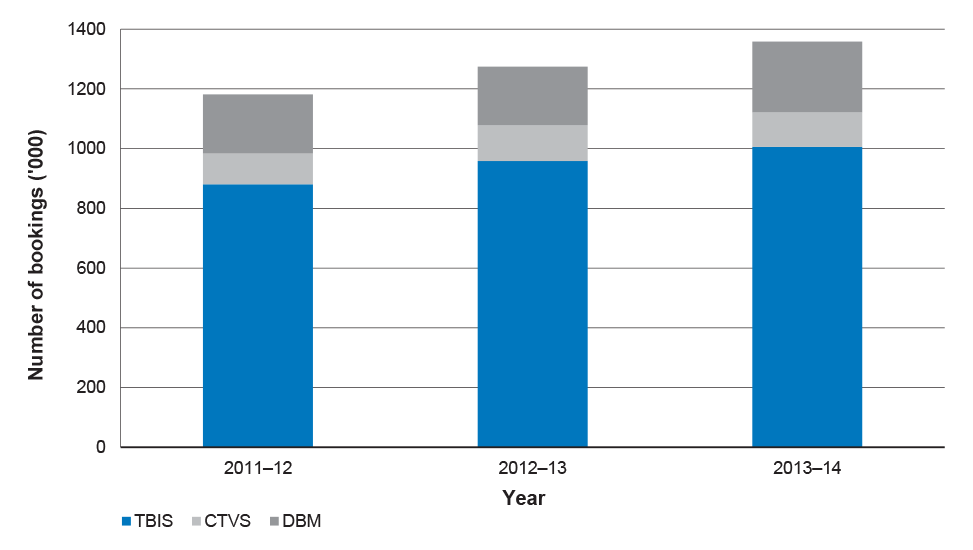

1.9 In 2013–14, DVA processed 159 905 travel reimbursement claims, a decrease of three per cent compared to 2012–13. The department also arranged 1 002 844 person trips27 through the Booked Car Scheme in 2013–14, a five per cent increase on the previous year’s total (see Figure 1.1). DVA reported in its 2013–14 Annual Report that these trends reflect an ageing population.28

Figure 1.1: Number of claims for travel reimbursement and Booked Car Scheme trips 2008–14

Source: DVA Annual Report data.

Notes: A ‘claim’ for travel reimbursement may contain a number of visits to a health provider as well as associated parking, tolls, meals, accommodation, and other costs. There is no limit on the number of trips that can be included on a claim. The number of trips per claim has ranged from between one and 165 on a single claim form.

A Booked Car Scheme trip is a one way trip to, or from, a health provider.

Figures for the number of Booked Car Scheme person trips for 2010–11 are not directly comparable with earlier years due to the introduction of the Booked Car Scheme transport booking and invoicing system (TBIS).

1.10 The Australian Government budgeted $184 million for veterans’ travel for treatment purposes and $7 million for subsistence (meals and accommodation allowances paid by DVA) in the 2014–15 Budget. The RTS is a demand-driven program with funding drawn from a Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 Special Appropriation. The department expects RTS expenditure to increase in the future as an ageing veteran population accesses a greater quantity and variety of healthcare services, notwithstanding a decreasing health card holder population.29 Over the next three years the cost of the RTS is estimated to total $585 million.

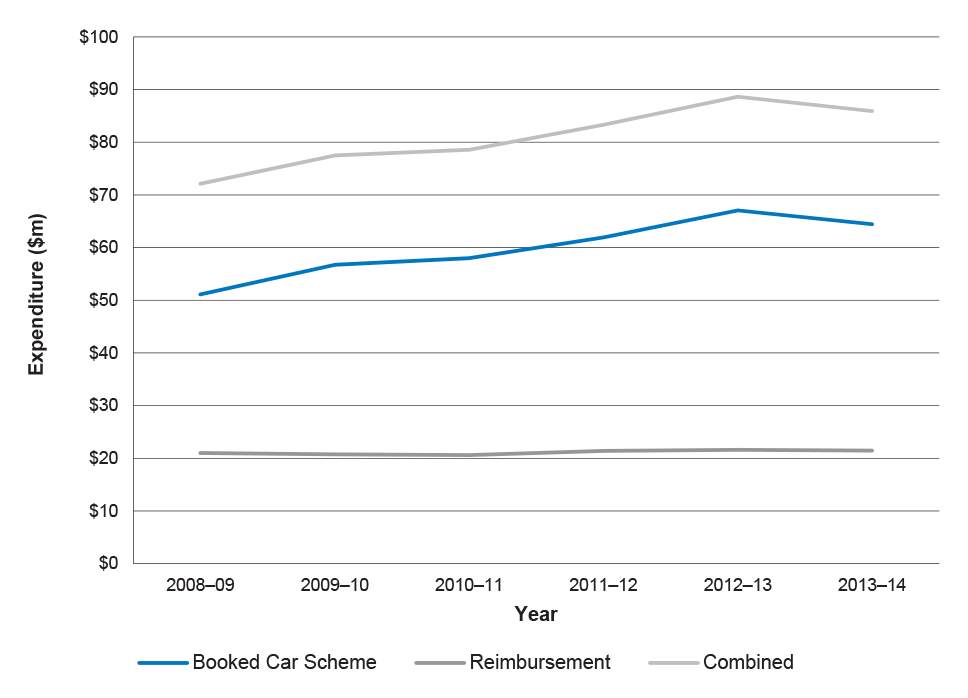

Figure 1.2: Booked Car Scheme and travel reimbursement claims expenditure 2008–14

Source: DVA Internal Data.

1.11 Figure 1.2 indicates that combined expenditure on the travel reimbursement and Booked Car Scheme components of the RTS was around $85 million in 2013–14.30 The cost of administering the RTS was $4.85 million in 2013–14, and has remained relatively stable over the last five years.31

Recent changes to the Repatriation Transport Scheme

1.12 The RTS is managed by the Veterans’ Transport Services Section within DVA’s Health and Community Services Division. From 2005, the administration of the RTS shifted from a state-based approach to a national basis, to improve national consistency and increase efficiency. Processing of all claims for travel reimbursement and long distance travel is now undertaken in Brisbane, whilst all accounts and contract management functions are managed in Sydney. The management of bookings under the Booked Car Scheme is undertaken by DVA offices in Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. As at 1 July 2014, there were 63.5 staff in the section, the majority of whom were responsible for making transport bookings under the Booked Car Scheme.

1.13 Other key developments in the RTS in recent years include:

- changes to travel reimbursement introduced in May 2012 which removed the requirement for claims to be certified by health providers and receipts to be attached, to facilitate the introduction of online claiming;

- a national panel of taxi and hire car providers established through a 2011–12 procurement process;

- the introduction of a new Booked Car Scheme IT system in June 2011—the Transport Booking and Invoicing System (TBIS); and

- the addition of transport data to DVA’s client database warehouse system in April 2014, which has enabled the department to interrogate multiple databases used for the RTS and report broad trends.32

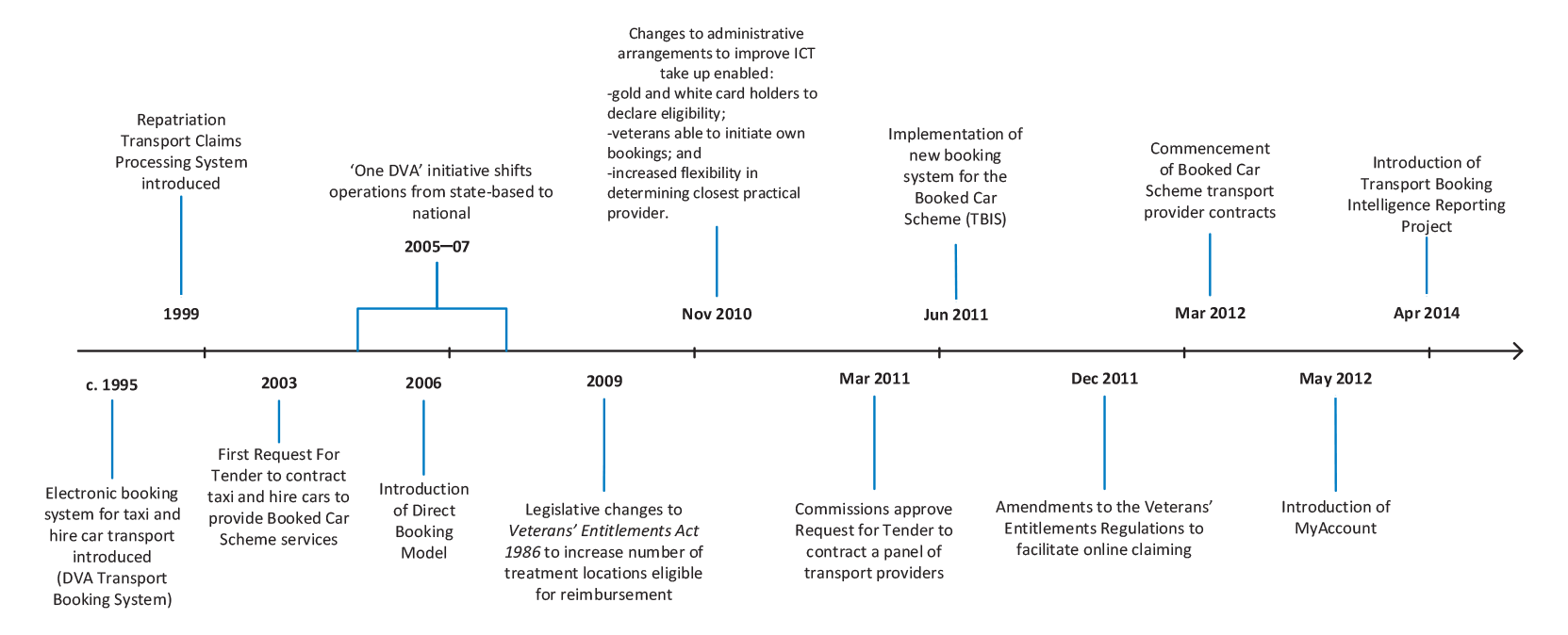

1.14 Figure 1.3 summarises the key developments in the RTS over the last two decades.

Figure 1.3: Timeline of key developments in the Repatriation Transport Scheme

Source: ANAO.

Previous audit coverage

1.15 ANAO Audit Report No.6 2002–03 Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Veterans’ Affairs examined fraud control arrangements across DVA including the RTS. In that audit, DVA staff advised the ANAO of their concerns about, and scope for, fraud in the RTS.33 In respect to the RTS, the audit concluded that:

- the department’s procedures were not consistent with applicable sections of the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 and Regulations; and

- there was no systematic approach in place, or a quality assurance process, that would assist in identifying claim anomalies and potential fraud.

1.16 The ANAO recommended that: ‘DVA take action to standardise travel allowance claim procedures and documentation under the RTS to be consistent with the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 and its Regulations’. The department agreed to the recommendation, acknowledging that there was a need to introduce a national quality assurance system for travel claims, and indicated that it would standardise travel allowance payment processes to ensure they were consistent with the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986.34 Progress in implementing the recommendation is examined in Chapter 2 of this audit.

1.17 In 2014–15, the ANAO tabled a cross-agency audit on the overall governance of fraud control arrangements in selected entities, including DVA.35 The audit concluded that the department was generally compliant with the applicable mandatory requirements of the 2011 Fraud Control Guidelines.

1.18 Since 2009–10, DVA has conducted four internal audits relevant to this audit:

- a review of DVA’s quality assurance in February 2010 found that the quality assurance program for travel reimbursement did not serve the current business objectives and was not adequate as a control in limiting errors. Recommendations related to reviewing the quality assurance program and developing new recording and reporting requirements;

- a review of transport for treatment in November 2010 focused on travel reimbursement and identified control weaknesses, an ineffective quality assurance program and inappropriate access to the travel reimbursement system;

- a review in April 2012 focusing on the Booked Car Scheme identified a range of issues in relation to quality assurance and post-payment monitoring, transport payment arrangements, poor controls in the processing system and payment approval inefficiencies. The audit recommended that the department complete a risk assessment and review of post-payment monitoring and update the quality assurance framework; and

- a post-implementation review of the Choice and Maintainability in Veterans’ Services transport booking module in November 2012 concluded that, while the Transport Booking and Invoicing System had delivered many of the planned benefits, there were limitations to these benefits. In response, DVA developed an action plan to address control and other issues.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.19 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) administration of the Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS).

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- DVA administers the RTS in accordance with legislation and relevant guidelines;

- DVA has implemented systems and processes to provide authorised transport services and travel reimbursements to eligible clients in an accurate and timely manner;

- DVA has procured transport services in accordance with relevant guidelines and effectively manages relevant contracts; and

- DVA effectively monitors and reports on performance to inform its delivery of the RTS.

Scope of the audit

1.21 The audit focused on the administration of travel reimbursement and Booked Car Scheme transport funded through the RTS. The audit did not examine the administration of funding provided under the RTS to state and territory governments for the provision of ambulance services to eligible veterans.

Audit methodology

1.22 The audit methodology included:

- reviewing relevant documentation including legislation, briefings, policies, procedures, reports and correspondence;

- interviewing DVA management and staff members;

- conducting a staff survey to assess training and development requirements, in addition to reviewing training and guidance material;

- reviewing written submissions from key stakeholders, including Ex-Service Organisations, contracted transport providers, and representatives of the taxi industry;

- mapping travel reimbursement and Booked Car Scheme processes to identify and test the effectiveness of existing controls;

- substantive testing of a selection of claims for travel reimbursement to verify the accuracy of claims processing; and

- identifying controls and associated risks for DVA’s systems for processing claims for travel reimbursement (Repatriation Transport Claims Processing System) and Booked Car Scheme bookings (Transport Booking and Invoicing System).

1.23 Field work was conducted between August and December 2014 in DVA’s national office in Canberra, and in DVA state offices in Brisbane and Sydney.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $592 000.

Report structure

Table 1.1: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Title |

Content |

|

2 |

Travel Reimbursement |

Examines the effectiveness of DVA’s administration of travel reimbursement, focusing on quality assurance processes and the adequacy of key controls. The chapter also examines the adequacy of training and support provided to DVA staff administering the Repatriation Transport Scheme. |

|

3 |

Booked Car Scheme |

Examines the administration of the Booked Car Scheme, including the procurement of transport services, contract management and the operation of the national booking system. |

|

4 |

Performance Monitoring and Reporting |

Examines the external and internal performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Repatriation Transport Scheme. |

2. Travel Reimbursement

This chapter examines the effectiveness of DVA’s administration of travel reimbursement, focusing on quality assurance processes and the adequacy of key controls. It also examines training and support provided to DVA staff administering the Repatriation Transport Scheme.

Introduction

2.1 Sound reimbursement processes feature a risk management approach, effective controls, quality assurance mechanisms, and appropriate training and guidance for staff. The ANAO examined DVA’s administration of travel reimbursement for the Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS or the Scheme), including key changes implemented since 2009, to assess the overall integrity of reimbursement arrangements.

Overview of claims process

2.2 Travel reimbursement is a long-established component of the RTS.36 DVA is responsible for paying a contribution towards travelling expenses, in the form of an allowance, for veterans attending DVA-approved medical treatment within Australia. Eligible veterans can claim reimbursement for kilometres travelled using a private vehicle, parking fees, road tolls, taxi fares, air travel, public transport costs and accommodation costs associated with medical travel.37 Eligible veterans need to attend the closest practical health provider to their residence and travel by the most economical and suitable means of transport available at the time.

2.3 Veterans claim for travel reimbursement under the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986. Claims can be made using ‘MyAccount’, which is the DVA online services channel, or by lodging a D800 Claim for Travelling Expenses form by post. The three main processing steps performed by DVA are to:

- determine the eligibility of the claimant;

- assess the claimant’s entitlement (including checking claim accuracy and making adjustments to claims, if necessary); and

- approve reimbursement of the travel claim.

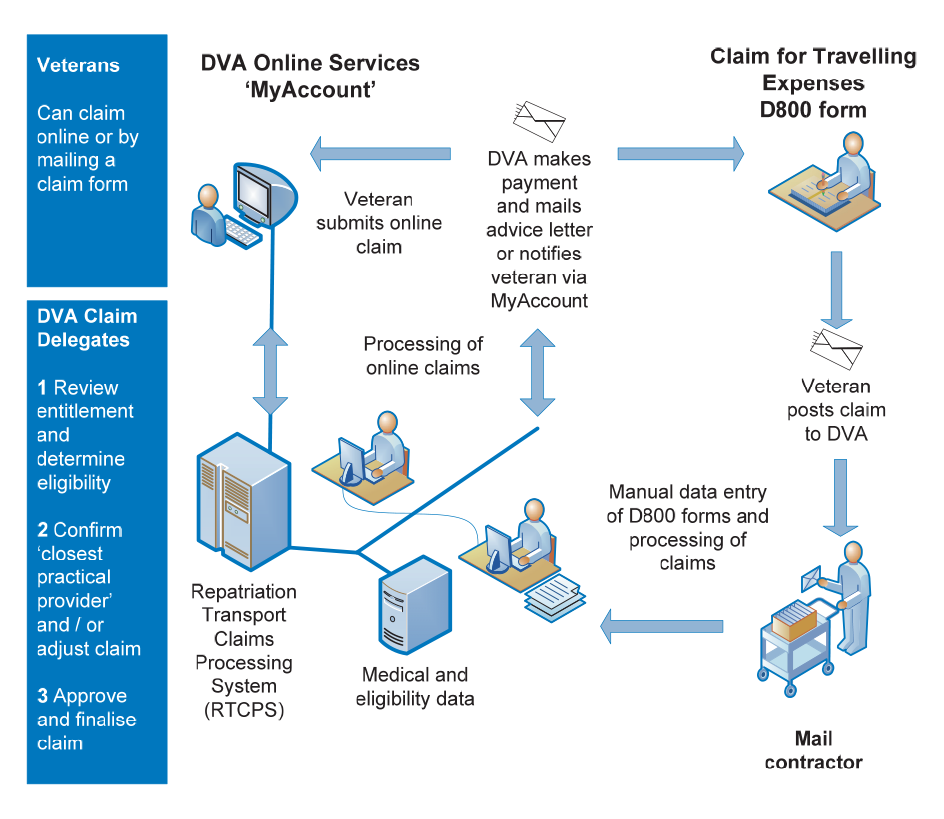

2.4 Figure 2.1 illustrates the main steps in the travel reimbursement process.

Figure 2.1: Main steps in travel reimbursement process

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.5 DVA’s Repatriation Transport Claims Processing System (RTCPS) is an electronic system used to record claims made by veterans for travel assistance, calculate entitlements based on data entered, and facilitate the payment of travel allowances to veterans.38 The RTCPS has operated for 15 years and is central to the processing of reimbursement claims.39

2.6 DVA has been aware for some time of limitations in the RTCPS, which requires a high degree of manual processing and intervention to process claims.40 Over time, enhancements have been made to the system and the department has also examined options to redevelop or replace the RTCPS. In 2008, the RTCPS was scheduled for replacement but the new system was not implemented due to unsatisfactory performance during testing. The department advised the ANAO that options for the replacement and/or redevelopment of the RCTPS are again under review.

Changes to travel reimbursement

2.7 Significant changes to the administration of travel reimbursement resulted from the Choice and Maintainability in Veterans Services (CMVS) program initiated by DVA in 2009. The program sought improvements to service delivery throughout the department, including simplifying travel reimbursement and providing greater online access to veterans.41 The department obtained endorsement from the Repatriation Commission for a range of changes to the D800 travel expenses claim form to facilitate online claiming in December 2011.42 The online lodgement of travel claims through ‘MyAccount’ was also introduced in May 2012. Table 2.1 outlines the key changes to travel reimbursement arrangements.

Table 2.1: Key changes to travel reimbursement since 2011

|

Type of change |

Change under new D800 form and online claiming module |

|

Legislative |

|

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Policy |

|

Source: DVA.

Managing the risks to travel reimbursement

2.8 As summarised in Table 2.1, the introduction of online claiming in 2012 was attended by changes in Scheme requirements. For example, claimants were no longer required to: provide receipts; or retain receipts for travel expenses less than $30. While the revised arrangements simplified administrative processes, a number of pre-payment controls and compliance checks were also removed. These had previously been key safeguards against fraudulent or incorrect payments.

2.9 Before seeking approval from the Repatriation Commission for changes to travel reimbursement arrangements, the department held a workshop in 2011 which identified key risks associated with the removal of pre-payment controls.43 The risks identified included an increased potential for fraud.44 The department also anticipated that potential fraud risks would be mitigated by the introduction of a post-payment monitoring system and enhancing its existing quality assurance processes. The department’s expectations in this regard were reflected in its advice to the Repatriation Commission:

The existing quality assurance program which has a traditional front end pre-decision compliance focus will be enhanced to include a more concentrated risk management post-payment monitoring focus.

2.10 The department developed a series of management strategies to mitigate the identified risks, which were assessed as moderate at the time. Table 2.2 outlines the strategies and the ANAO’s assessment of their implementation status as at December 2014.

Table 2.2: Risk management strategies implemented by DVA

|

Management strategies for key risks identified in December 2011 |

ANAO assessment as of December 2014 |

|

Quality Assurance Program to be aligned with the introduction of proposed amendments to regulations and legislation. |

Not implemented

|

|

Post-payment monitoring for claims over 100 km and monitor eligibility and use trends in the uptake of the RTS. |

Not implemented

|

|

Preparation of a communication plan |

Implemented

|

Source: ANAO.

2.11 In summary, while DVA took appropriate steps to identify risks associated with the changes introduced to travel reimbursement, the department failed to implement its planned mitigation measures45 and the risks remained largely untreated for three years. Further, the ‘moderate’ risk rating for the 2012 changes has not been reassessed since 2012, notwithstanding the failure to implement the planned quality assurance and post-payment monitoring processes.

2.12 Shortcomings in the RTS risk management framework reflect weaknesses in DVA’s broader risk management framework. A 2013 internal audit report on DVA’s risk management framework identified weaknesses in risk management at the enterprise, business and project levels.46 A follow-up internal audit completed in February 2014 indicated that whilst the department’s risk management capability had matured in relation to business risk and project risk, further development was required to: define roles and responsibilities; improve the quality of risk information for business planning; identify, assess and document risk management for business improvement activities; and improve central analysis of the quality of risk management information.

2.13 Since the 2014 internal audit, DVA has been taking steps to improve its risk management framework at both the enterprise and business levels.47 On 30 November 2014, the responsible branch head endorsed the 2014–15 business plan for the Transport, Research and Development Branch (which has responsibility for the Repatriation Transport Scheme). While the 2014–15 business plan included more detailed risk information than in the previous year48, the business risks have not been assessed and rated in terms of significance, likelihood and impact. Further, the business level risks have not been linked to relevant project risks although they have been linked to relevant enterprise-level risks.

Controls framework for travel reimbursement

2.14 The ANAO assessed the overall integrity of travel reimbursement arrangements by testing:

- relevant controls to determine whether they provide a reasonable level of assurance in respect to the validity and accuracy of travel claims; and

- a sample of claims.

Controls testing

2.15 System controls and documented procedures for the RTCPS are intended to provide support to claim delegates in assessing the validity and accuracy of claims. There are three types of controls:

- a range of automatic controls which provide alerts and warnings to claim delegates on claim limits and conditions, facilitate checks for eligibility and other medical need criteria, and assist in detecting duplicate claims or same day bookings;

- controls to maintain correct and up-to-date rates for travel reimbursement in the RTCPS; and

- a suite of IT-dependent and manual controls which support accurate and timely assessment of claims, for example, the identification of the health provider as the closest practical provider and regular reporting on the number of claims to be processed.

2.16 The ANAO examined a range of existing controls to assess their effectiveness. A summary of these controls and the ANAO’s assessment of their effectiveness is presented in Table 2.3. Key controls are bolded in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: ANAO assessment of travel reimbursement controls

|

Control Type |

Description of control (bold text denotes a key control) |

Assessment |

|

Automatic |

Claim delegates have up-to-date information on eligibility type (Gold Card/White Card), multi-Act eligibility (MRCA/SRCA) and medical data (accepted conditions). |

Effective |

|

The RTCPS is linked to the Transport Booking and Invoicing System (TBIS) for the Booked Car Scheme to identify same day bookings. |

Effective |

|

|

Duplicate claims or other RTCPS bookings made on the same day can be detected and the system warns claims delegate if accommodation date and visit date are different. |

Effective |

|

|

System alerts and warnings to claims delegate about claim limits or other conditions that need to be verified or corrected before making a decision to override. |

Effective |

|

|

Standing data |

Correct rates for reimbursement stored in the RTCPS, applied based on the date of visit, and updated in line with movements in the consumer price index effective each year from 1 July.a |

Effective |

|

IT-dependent manual controls |

RTCPS provides for claims delegate to include important notes on a particular claim and can also flag, if necessary, particular claims, which are then forwarded for review by a senior claims delegate.b |

Effective |

|

RTCPS provides for claim delegates to record previous assessments of closest practical provider.c |

Partially Effective |

|

|

Manual controls |

Induction and training of staff.d |

Partially Effective |

|

Regular reporting on claims to be processed. |

Effective |

|

|

Claim delegates use Google and Google maps to determine whether the health provider is the closest practical provider.e |

Effective |

|

|

Veterans required to retain receipts over $30 for four months. |

Partially Effective |

|

|

Claim delegates use Google maps to confirm distances claimed. |

Partially Effective |

|

|

Quality assurance. |

Not effective |

|

|

Post-payment monitoring. |

Not implemented |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Notes to Table 2.3:

(a) Access to the rates stored in the system were limited to authorised staff.

(b) For veterans with special conditions or a past claims history that requires ongoing checking, claims can be automatically diverted to a senior claims delegate for review.

(c) This control could be further strengthened by consistent recording of the date of last assessment of closest practical provider in the RTCPS.

(d) Discussed further in this chapter under training and staff support.

(e) Google and Google maps are web-based applications routinely used by claim delegates to support claims processing. In particular, Google assists in processing claims for travel outside closest practical provider thresholds—trips further than 50 kilometres from the home address of a veteran—so they are accurately assessed and correctly reimbursed.

2.17 In summary, shortcomings in the controls framework were identified in respect to:

- ad hoc quality assurance processes;

- the failure to implement post-payment monitoring;

- lack of clarity regarding the period that receipts must be retained by veterans to facilitate checking by DVA; and

- ad hoc use of Google maps to confirm distances claimed.

2.18 Specific weaknesses identified in the control framework are examined further in the following paragraphs.

Ad hoc quality assurance processes

2.19 Quality assurance activities are intended to assist in detecting and addressing errors in claims processing. Quality assurance will often involve third party review of a sample of claims for correct processing and accurate data entry into the information system. The percentage and type of errors are recorded to identify general error rates and trends, knowledge of which can assist in targeting areas of weakness and possible improvement.

2.20 Currently, DVA undertakes some quality assurance activities involving ad hoc checks of claims. The department advised the ANAO that some informal checking occurs where there are high value or long distance claims, and that checks are also undertaken when veterans contact the department to report potential overpayments. However, the ANAO’s review indicated that these checks are not systematic and are not part of a formal quality assurance program with third party review of a sample of claims and formal recording of errors to identify any systemic weaknesses.

2.21 The ANAO identified a number of weaknesses in relation to DVA’s quality assurance framework in the context of the 2011–12 and 2012–13 financial statement audits. Key weaknesses included incomplete quantification of identified errors, inadequate segregation of duties within the IT application used for quality assurance, lack of an audit trail and inadequate documentation.

Post-payment monitoring

2.22 Post-payment monitoring involves both sample testing of transactions against program requirements and statistical analysis of payments made. The department advised the ANAO that there has not been any formal post-payment monitoring since reimbursement commenced in 1986.

2.23 The department further advised the ANAO that planned enhancements to quality assurance processes and the introduction of post-payment monitoring were not implemented in May 2012 due to the pressure of competing business priorities, including delivery of major changes to the Booked Car Scheme. During the course of the audit DVA was developing its capacity to review the validity and accuracy of payments to reimburse travel, through revisions to the RTS quality management framework, including:

- preparing a Quality Management Framework for travel claims reimbursement49;

- developing a post-payment monitoring regime for reimbursement50; and

- conducting a risk and fraud assessment for the RTS which included the reimbursement of travelling expenses.51

2.24 Implementation of the revised quality management framework is at an early stage, and in light of past experience mentioned in paragraph 2.23, the department should review its overall approach to implementing the planned initiatives so as to provide management assurance that agreed risk mitigation measures will be progressed and will operate as anticipated. For instance, the appointment of a senior responsible officer and the development of a project implementation and risk management plan would contribute to successful implementation.52 There would also be benefit in DVA considering the introduction of internal performance measures to help monitor the operation and effectiveness of these arrangements.

Recommendation No.1

2.25 The ANAO recommends that DVA review its approach to the implementation of post-payment monitoring and enhanced quality assurance arrangements for the Repatriation Transport Scheme, to provide management assurance that the planned measures—intended to improve the level of confidence of the validity and accuracy of travel claims and bookings—will operate as anticipated.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs response: Agreed.

2.26 The development of quality assurance and post-payment monitoring for travel reimbursement has, in part, been affected by limitations in DVA’s data systems.53 In response to these limitations, the department initiated the Transport Business Intelligence Reporting Project (TBIRP) in 2013 to develop more flexible reporting capability enabling post-payment monitoring for the RTS.54 The resulting data set from the TBIRP was added to a reporting tool, the Departmental Management Information System (DMIS) in April 2014, which allows DVA to combine data from systems such as the RTCPS and the Transport Booking and Invoicing System (TBIS), with veterans’ data and health service usage data.55

2.27 The department advised the ANAO that the collection and analysis of reimbursement data for post-payment monitoring commenced during August and September 2014 (during the course of the audit) and involved cleansing data and resolving issues associated with data matching. An issue that the department identified in relation to the efficiency of data matching is the three to four month time lag involved in matching trips to medical appointments using Medicare data.56

Retention of receipts by veterans

2.28 The retention of receipts by claimants facilitates post-payment monitoring activities. This control has been assessed by the ANAO as partially effective (see Table 2.3) for two reasons. First, there has been no formal post-payment monitoring since the introduction of online claiming in May 2012, when DVA removed the requirement for receipts to be provided with claims.57 Second, claims can be lodged up to 12 months after the completion of travel, yet the need to retain receipts could be reasonably interpreted as being for four months from the date of travel.58 The department advised the ANAO that it considers the four month retention period is sufficient at this stage, but may review arrangements once reporting from the Quality Management Framework has been assessed.

Ad hoc use of Google maps to confirm distances claimed

2.29 A risk to the integrity of travel reimbursement arrangements is the overstatement by claimants of the kilometres travelled in a private vehicle or spent on taxi fares. Further risks arise as a meal allowance can be claimed for trips over 100 kilometres. Google maps is sometimes used by DVA to assist claim delegates assess travel outside closest practical provider thresholds—trips further than 50 kilometres from the home address of a veteran—so that travel claims are accurately assessed and correctly reimbursed. Currently, it is at the discretion of claim delegates to check distances claimed59, and there would be merit in the department considering the benefits of a more structured approach.

2.30 The ANAO tested a sample of travel claims to determine whether the distances claimed were accurate.60 In particular, the ANAO checked whether kilometres being claimed by veterans were reasonable based on queries run in Google maps.61 Figure 2.2 shows the percentage variation between distances claimed and the estimate obtained by the ANAO when checking a sample of claims with Google maps. A variation in the distance claimed and distance estimated using Google maps can indicate that there has been an overpayment or underpayment relating to the claim, or a non-compliant claim.

Figure 2.2: Percentage variation between distance claimed and estimate from Google maps

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.31 The ANAO’s testing indicated that there was a degree of variation between the distances claimed for travel and the distances estimated using Google maps. Approximately three quarters (75 per cent) of claims sampled claimed a distance that was greater than the distance estimated by Google maps, which represents a potential for overpayment. The remaining one-quarter of sampled claims (24 per cent) recorded a distance that was less than the distance estimated by Google maps and therefore indicate cases of potential underpayment. The remaining one per cent of claims sampled claimed a distance that was equal to the distance estimated by Google maps.

2.32 Twenty eight per cent—or 93 of the 349 trips sampled—claimed a distance that was more than 10 per cent higher than the distance estimated by Google maps.62 This degree of variation is statistically significant and indicates cases of potential overpayment that merit further review. The department’s ad hoc checking63 of a separate sample of claims in 2014 also identified several overpayments—that are subject to recovery action—and some potential cases of non-compliance which have been referred to DVA’s compliance section for investigation.64

Training and staff support

2.33 The effective operation of complex and high volume programs relies on well-trained staff with an appropriate level of understanding and access to tools, guidance material and sources of advice to support them.

2.34 Administration for the RTS is decentralised across five state capitals and involves some 63 staff. Staff process high volumes of travel claims and bookings which are subject to periodic fluctuations in workload.65 Further, the relatively high proportion of contract and temporary staff and associated turnover66 can place additional pressure on more experienced staff, who help provide on-the-job training and support for new staff.

2.35 The ANAO examined the training and support provided by DVA to Veterans’ Transport Services staff responsible for travel reimbursement and the Booked Car Scheme, including:

- training and support materials; and

- staff satisfaction regarding training and support.

Training and support materials

2.36 DVA has developed of range of useful materials to induct and train RTS staff, including:

- the Booked Car Scheme Participant Workbook, updated in June 2014;

- the travel reimbursement User Guide, updated in October 2014;

- a recently introduced Quick Reference Guide for travel reimbursement;

- induction material for new claim delegates, developed during the course of the audit67; and

- training material on telephone techniques for veteran transport service staff.

2.37 Interviews with selected staff from the Booked Car Scheme indicated that the training materials, in particular the induction training for the Booked Car Scheme, had been useful. Travel reimbursement staff interviewed by the ANAO commented favourably on a recently introduced Quick Reference Guide for travel reimbursement as a useful resource, particularly for newer staff. They suggested a number of enhancements including adding frequently asked questions and providing more examples.

Survey of staff satisfaction on training and support

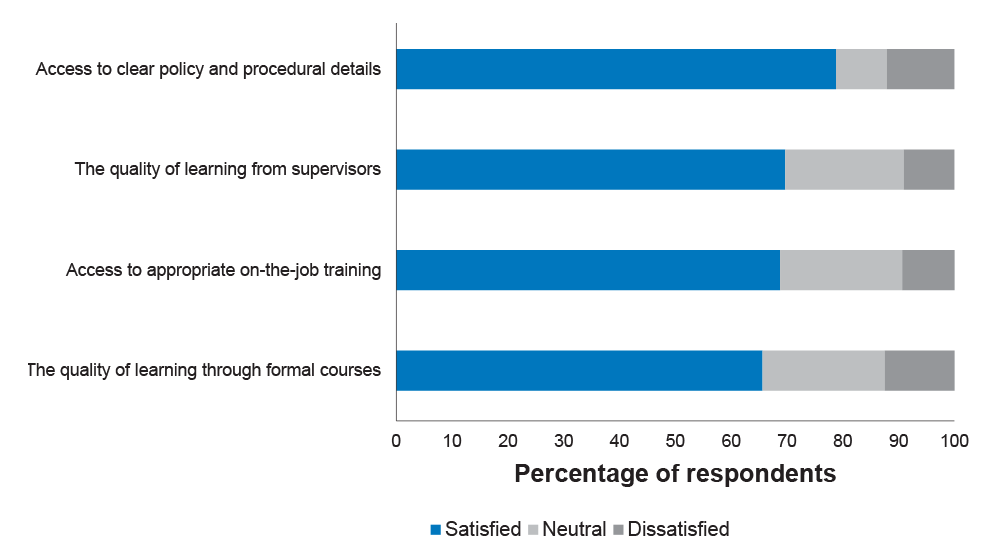

2.38 The ANAO conducted a staff survey of the training and support provided to RTS staff.68 Overall, staff were generally satisfied with the type of training and support that was available to them including on-the-job support, guidance material and formal training. Figure 2.3 summarises the level of DVA staff satisfaction with training and support.

Figure 2.3: Level of staff satisfaction with training and support

Source: ANAO.

2.39 Two key issues that emerged from the survey responses were: limited access to more experienced staff to provide on-the-job training; and work pressures curtailing time for training and development. There would be benefit in DVA considering strategies to improve access to training opportunities, particularly for new and inexperienced staff.

Conclusion

2.40 In May 2012 DVA removed a number of controls for travel reimbursement claims processing—including the reconciliation of reimbursement claims against receipts and endorsement by health providers of the need to travel—as part of its development of online claiming by veterans. At the time, the department identified a number of potential risks prior to the implementation of online claiming, such as increased non-compliance by clients, and proposed a number of risk mitigation measures. The measures included post-payment monitoring and enhanced quality assurance processes.69 However, the planned measures were not implemented in a timely manner, and the identified risks remained largely untreated for almost three years. Further, the risks first identified in 2011 have not been re-assessed since then, in light of experience in administering the revised arrangements.

2.41 During the course of the audit DVA was developing its capacity to review the validity and accuracy of payments to reimburse travel, through revisions to the RTS quality management framework. Implementation of the revised framework is at an early stage, and the department should review the overall implementation approach to provide management assurance that the agreed risk mitigation measures will be progressed as planned, and will operate as anticipated. For instance, the appointment of a senior responsible officer and the development of a project implementation and risk management plan would contribute to the successful introduction of planned post-payment monitoring arrangements and enhanced quality assurance. There would also be benefit in DVA considering the introduction of internal performance measures to help monitor the operation and effectiveness of these arrangements.

2.42 The ANAO’s controls testing of the travel reimbursement processing system, known as the Repatriation Transport Claims Processing System, identified shortcomings in relation to: the absence of post-payment monitoring; quality assurance arrangements; ad hoc confirmation of distances claimed; and a lack of clarity regarding the period that receipts must be retained by veterans to facilitate checking by DVA. For instance, receipts for claims over $30 are only required to be kept for four months, which may limit the department’s capacity to check receipts as part of the post-payment monitoring arrangements currently being planned.

3. Booked Car Scheme

This chapter examines the administration of the Booked Car Scheme, including the procurement of transport services, contract management and the operation of the national booking system.

Introduction

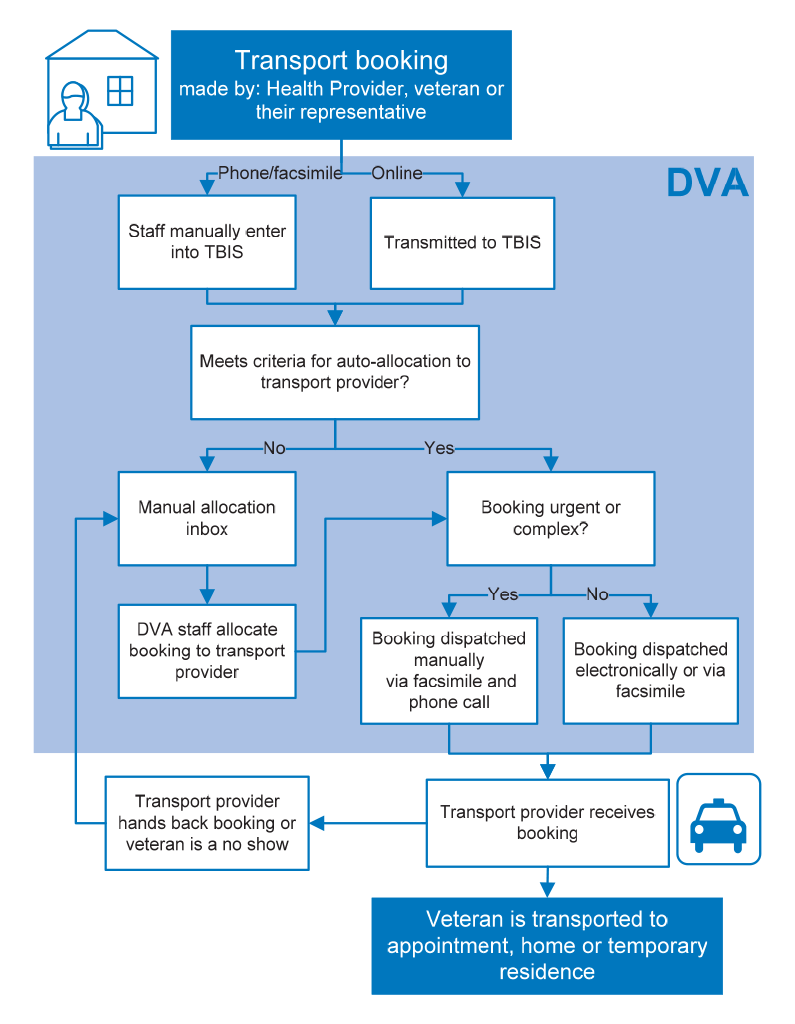

3.1 The Booked Car Scheme70 (BCS) is a component of the Repatriation Transport Scheme (RTS or the Scheme) which provides government funded taxi and hire car transport for veterans to travel to and from medical treatment. Veterans aged 80 or over who hold a gold card issued under the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 (VEA) are able to use the BCS to travel for treatment relating to any medical condition, whereas those aged 80 or over with a VEA white card may only travel to appointments related to approved conditions.71 Transport is provided at no cost to veterans, with contracted taxi and hire car companies (transport providers) invoicing the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) directly for services provided. The department has entered into contracts with over 300 transport providers nationally to provide veterans with access to transport services. In addition, DVA can arrange long distance travel via air or rail.72

3.2 The number of BCS bookings funded by DVA has been increasing steadily over recent years. Expenditure on the Scheme has also increased from $61.9 million in 2011–12 to $64.4 million in 2013–14. The department has reported that these trends reflect the ageing veteran population73, particularly the increasing use of the BCS by Second World War veterans.

3.3 To assess DVA’s administration of the Booked Car Scheme, the ANAO examined:

- procurement and contract management arrangements;

- the operation of the national booking system; and

- booking system risks and controls.

Procurement of services

3.4 In 2011–12, the department issued a Request for Tender (RFT) to establish a panel of over 300 transport providers to deliver Booked Car Scheme services to veterans nationwide. The successful providers range from metropolitan taxi networks with thousands of vehicles, to single vehicle hire car operators in rural areas. Individual contracts are valued at between $1000 and $27 million.74

3.5 At the time, Australian Government policy on procurement was set out in the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines (CPGs).75 Achieving value for money was (and remains) the ‘core rule’ of the procurement framework, and its application to procurement processes contributes to the proper use of Commonwealth resources.76 In this context, the ANAO examined the procurement process used in 2011–12 by DVA to select transport providers for the Booked Car Scheme.

3.6 The department’s approach to the 2011–12 tender process was informed in part by lessons learned from a previous tender for transport providers conducted by DVA in 2003. Evaluation of the 2003 tender process identified that the tender evaluation and contract negotiation process was lengthy and resource intensive, with a cost of approximately $1.4 million to the department. Moreover, DVA received feedback from the taxi and hire car industry that the complexity of the tender documentation resulted in many potential tenderers, particularly those in rural areas, not applying.

3.7 In April 2011, the Commissions77 approved a departmental proposal to undertake a single open (competitive) tender incorporating taxi and hire car providers for the Booked Car Scheme. A streamlined tender process was agreed upon, which:

- relied on state and territory regulatory frameworks for standards in areas such as accreditation and insurance;

- adopted a uniform approach to supplying and assessing pricing information; and

- involved a simplified assessment of other criteria.

3.8 Governance arrangements to manage the procurement process included a project team and a Tender Evaluation Panel. A Tender Steering Committee was also established to provide oversight and approve internal and external documentation and procedures. The Committee received additional advice from an external probity advisor as necessary.

Release of the Request For Tender

3.9 The RFT was advertised on AusTender78 from 24 June until 5 August 2011. The department also advertised the RFT through: national and state-based newspapers; the DVA website; an industry briefing session; and letters to current contractors, those who had previously contacted DVA expressing interest in becoming Booked Car Scheme providers, state and territory transport regulators, and industry bodies.

Tender Evaluation

3.10 The department received 290 tenders which were assessed as suitable for tender evaluation.79 The tenders were assessed through a four stage evaluation process involving: initial screening, assessment of weighted evaluation criteria, assessment of price to determine value for money, and identification of preferred tenderers. This process was undertaken from August to November 2011.

3.11 The department engaged an external procurement consultant from a government panel to assist with administration of the tender evaluation process.80 The consultant developed an Excel spreadsheet known as the Business Allocation and Reporting Tool to assist DVA in tracking tenderers’ scores against criteria, value for money and potential providers’ areas of operation. This tool was also used to forecast levels of demand in each area of operation using TBIS data.81

3.12 The Tender Evaluation Panel prepared a Tender Evaluation Report which summarised the evaluation process and listed the 258 transport providers identified as ‘preferred tenderers’. The report was endorsed by the probity advisor on 8 December 2011 and the Tender Steering Committee on 13 December 2011. The Commissions approved the tender outcomes on 2 February 2012 and three year Deeds of Agreement were subsequently negotiated with tenderers.82

Compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines

3.13 The ANAO examined DVA’s procurement process, having regard to the CPGs and better practice in procurement and contracting.83 The procurement exercise was conducted as an open tender and was assessed by the ANAO as generally in accordance with the CPGs, with some shortcomings identified relating to:

- maintaining records of the Tender Steering Committee discussions and decisions; and

- completing conflict of interest disclosure statements for members of the Tender Steering Committee.

3.14 Table 3.1 outlines the results of the ANAO’s assessment.

Table 3.1: ANAO assessment of the 2011 procurement process

|

Element |

Assessment |

|

Advertising, publishing and reporting |

DVA advertised the tender in numerous forums and published information on AusTender for access by potential tenderers. |

|

Probity and risk management |

DVA engaged an external probity advisor, who provided ongoing advice and approvals throughout the procurement process.a Risk assessment completed. |

|

Conflict of Interest |

While conflict of interest disclosure statements were signed by relevant DVA staff and governance committee members, Tender Steering Committee members did not sign conflict of interest disclosure statements. |

|

Evaluation of value for money |

Open competitive tender. Criteria were set out clearly and assessment against criteria was recorded. Value for money assessed as part of tender evaluation. |

|

Record keeping |

Evaluation process was documented. Key documents and approvals were mostly completed; however, the department was unable to provide records of the discussions and decisions of the Tender Steering Committee. |

|

Financial approvals |

Regulation 9 approval obtained before entering into commitments to spend public money. Regulation 10 approval not required.b |

Source: ANAO.

Notes:

(a) The department’s engagement of the probity advisor relied on a previous selection process for probity advice relating to a different procurement exercise. A separate quote and Regulation 9 approval for the expenditure of around $15 000 were not prepared for this exercise.

(b) Regulation 10 approval was not required as the source of funds was the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 Special Appropriation.

Outcomes of the procurement process

3.15 In February 2012, the department reported to the Repatriation Commission that the RFT process and outcomes had provided a number of benefits, including:

- competitive pricing for local distance trips, enabling the department to use both taxis and hire cars more efficiently;

- increased vehicle coverage and competition, especially in metropolitan areas; and

- the provision of free additional services by many tenderers and improved understanding of DVA’s expectations of transport providers regarding service quality.

3.16 There were several non-preferred tenderers who had provided Booked Car Scheme services under previous arrangements. The department briefed the Commissions and the Minister on the tender outcomes, potential post-tender issues with unsuccessful tenderers and other risks as they arose. In some cases, DVA was required to respond to a number of complaints to the Minister and to communicate with Ex-Service Organisations and transport providers in order to resolve issues. Communication activities undertaken by the department are discussed further at paragraph 3.27.

3.17 DVA reported to the Commissions that while the procurement provided the department with better service coverage, there were still 54 areas of operation that did not have adequate Booked Car Scheme provider coverage or had no coverage at all. The department also advised the Commissions that in order to address these service gaps, it would approach existing providers who did not submit a tender in the first instance, as this represented a low risk and involved minimal additional cost. In June 2012, DVA reported that it had direct sourced around 70 providers across Australia and had resolved all identified service gaps.84

3.18 The procurement exercise was complex, and DVA subsequently considered that, to increase the efficiency of any future procurement exercises for Booked Car Scheme transport services, it would: design the tender process to give more consideration to the way in which the taxi industry operates; and would use an online form for tender submissions to avoid time consuming manual entry of responses received from tenderers.85

Contract management

3.19 When developing a contract, it is important to establish a clear and appropriate statement of contract deliverables and an effective performance management framework. Active monitoring of contracts against contract deliverables can help government entities obtain value for money, meet accountability obligations, and achieve business and program objectives.86

Key Performance Indicators

3.20 The ANAO examined DVA’s contract management arrangements with Booked Car Scheme transport providers to assess whether contracts were being managed effectively and with regard to specified key performance indicators. Contracts with transport providers are managed from DVA’s NSW office, which undertakes ongoing monitoring against performance measures established in the Schedule to each Deed of Agreement.87 The performance measures are mirrored in the requirements for transport providers set out in the publicly available Booked Car Scheme Guidelines for Taxi and Hire Car Contractors.88 Contractors are responsible for managing the performance of their employees, including drivers, call centre workers and subcontractors..

3.21 Table 3.2 outlines the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in DVA’s Deeds of Agreement with transport providers.

Table 3.2: Key Performance Indicators—DVA contracted transport providers

|

KPI |

Benchmark |

Measurement |

|

Hand backsa |

Number of hand backs received <1% of the DVA bookings to individual contractors over a one month period. |

TBIS reports.b |

|

Arrival time of vehicle |

Ensure vehicles arrive within a reasonable time of the advised appointment time. |

TBIS reports. May also be measured using feedback from veterans/health providers. |

|

Accurate invoices |

100% of prices correct. No duplications. <5% of all invoices rejected. |

Invoices. TBIS reports. |

Source: DVA.

Notes:

(a) A ‘hand back’ is when a transport provider who is assigned a Booked Car Scheme booking ‘hands back’ the booking to DVA to be re-assigned to a different transport provider, generally because they are unable to complete the booking in a timely manner.

(b) The Transport Booking and Invoicing System (TBIS) is the national booking system for the Booked Car Scheme (see footnote 81).

Contract monitoring and review

3.22 The Veterans’ Transport Services Section uses hand back statistics as part of its monitoring of transport provider performance. There are a number of standard operational reports in TBIS that provide booking and hand back statistics, which enable the department to track the day-to-day performance of individual service providers. These reports provide valuable operational data, contributing to DVA’s capacity to actively manage relevant contracts.

3.23 The Veterans’ Transport Services Section undertook a formal performance review in May 2013, some 15 months after the commencement of the transport provider contracts. The review assessed the performance of all contracted transport providers from 30 June to 31 December 2012 on a state-by-state basis. The department:

- analysed transport providers and their operating regions;

- assessed the percentage of hand backs in relation to total bookings, and variations to defined work allocation percentages, to detect percentages outside the defined thresholds; and

- collated the number and types of complaints that were recorded for each provider.

3.24 The performance review assessed provider performance in terms of handback rates and complaints to determine the allocation of future business. DVA considered the reasons for variation in assigning risk and performance target ratings. As a result of the review, the department modified areas of operation and allocation percentages for specific providers. In addition, DVA consulted with a number of transport providers about improving their hand back ratios.

3.25 The performance review assisted DVA to identify unsatisfactory contractor performance and redirect business to other providers as appropriate. As such, the review supported active contract management and the achievement of agreed business outcomes. Similarly, ongoing communication with contracted providers, particularly where specific problems or issues arise, has enabled the department to gain an understanding of their providers and the environment in which they operate, which has facilitated the department’s contract management. The contracts with transport providers were extended on 1 March 2015 for a further two years and the department advised that it is planning to undertake a second performance review in the second half of 2015.

Complaints

3.26 The department also monitors provider performance through its complaints processes. Complaints about Booked Car Scheme service delivery are recorded in the DVA Complaints and Feedback Management System, and trend analysis of complaints is undertaken by DVA’s central Feedback Management Team. It is the role of the Veterans’ Transport Services Section to identify the source of complaints about the BCS and to seek a resolution. The department advised that it contacts the complainant in the first instance in order to identify the reasons for the complaint. The department further advised that the resolution of complaints may involve engaging with transport providers, local taxi networks and Ex-Service Organisations. The level of complaints reported in relation to travel bookings is examined in Chapter 4.

Communication activities

3.27 The ANAO examined the communication channels used by DVA to build and maintain relationships with transport providers and their representative groups. Whilst the department advised that it does not have a formal communications strategy for the RTS, it undertakes a range of practical activities, including:

- attendance at taxi industry functions, including state and territory regulator meetings, taxi council meetings and taxi conferences;

- collaboration with industry groups on the development of driver training;

- contributing articles about service quality and expectations to industry journals; and

- round table meetings with representatives from Ex-Service Organisations, taxi networks, state governments and health providers.

3.28 The department advised the ANAO that there were negative reactions from a number of transport providers to the revised contracting arrangements introduced in March 2012, due to increased competition and the introduction of different pricing structures.89 There was also an increase in the number of complaints, including one from a transport provider relating to the probity of the procurement process which was resolved in the department’s favour. The department had anticipated many of the issues that arose in the RFT process and had developed a communication and transition strategy for the new arrangements to inform its interactions with stakeholders.

Feedback from stakeholders

3.29 The ANAO sought feedback on the administration of the RTS from key stakeholders, including DVA contracted transport providers, taxi industry bodies90, and Ex-Service Organisations. Feedback received was predominantly from transport providers, and included observations such as:

- the Booked Car Scheme is well administered and benefits veterans and transport providers, especially those in rural areas;

- the department has effectively engaged with the taxi and hire car industry, veterans, Ex-Service Organisations and health providers;

- as a result of DVA’s engagement, taxi companies have introduced a number of innovations to improve services, including driver education, dedicated DVA phone lines, and right of return business cards;

- some improvements to systems and processes are required to streamline operations; and

- some transport providers were unhappy with the outcomes of the 2011–12 procurement exercise and believe that their competitors were unfairly allocated bookings.

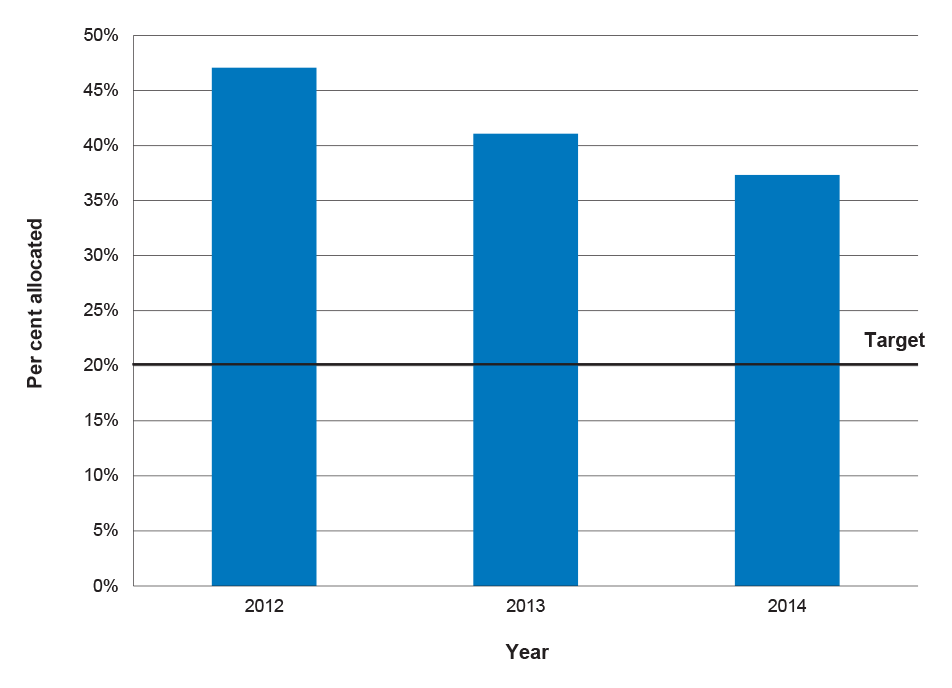

Access for veterans