Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Shared Services Centre

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training's administration of the Shared Services Centre to achieve efficiencies and deliver value to its customers.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. A shared services centre is an arrangement for the delivery of back-office support services such as accounting, human resources, payroll, information technology, legal, compliance, purchasing and security. The arrangement can allow a number of organisations to share operational tasks, avoiding duplication and providing economies of scale.

2. The Secretaries of the Department of Employment (Employment) and the Department of Education and Training (Education) established a shared services centre by agreement following the 2013 machinery of government (MoG) changes1 that abolished the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). The Secretaries’ agreement was intended to enable the departments to pursue efficiencies in the delivery of the services and to avoid the cost of separating the corporate functions of the former DEEWR. The centre is known as the Shared Services Centre (SSC).

3. The agreement also provided for service continuity to other ‘client’ entities2 that DEEWR had supported, and identified the potential for the SSC to provide services to other Commonwealth entities (entities). Expansion of the SSC as a services provider gained momentum during 2015 in the context of the broader whole-of-government shared and common services initiative administered by the Department of Finance (Finance) and overseen by the Australian Public Service (APS) Secretaries Board.3 A revised agreement between the two departmental Secretaries in March 2016 signalled the Secretaries’ aim that the SSC’s services be provided to other APS entities. The departments are referred to as ‘partner’ departments as part of this agreement.

4. As part of further machinery of government changes which occurred in September 2016, core transactional services provided by the SSC will move to Finance. The entities have advised that most of the remaining services provided to current SSC client entities will move to Employment, with a small number to Education. The Departments are working towards a 1 December 2016 date for the transfer of functions.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s and the Department of Education and Training’s administration of the Shared Services Centre (SSC) to achieve efficiencies and deliver value to its customers. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- governance arrangements incorporate sound oversight and planning;

- mechanisms have been established to ensure the effective delivery of services and the SSC’s ability to meet its commitments to customers to deliver value and ongoing efficiencies; and

- reporting arrangements and review activities provide for ongoing monitoring and continuous improvements to the operation of the SSC.

Conclusion

6. The department’s administration of the Shared Services Centre (SSC) has been effective for sharing resources between the departments and delivering selected back-office services to a small client base. However, the governance arrangements established to oversight the SSC have not positioned it well for the future and the departments have not yet determined if the arrangement is efficient and resulting in savings. In addition, responsible Ministers have not been well informed of the arrangements or their responsibilities in respect of competitive neutrality.

7. An advisory board provides guidance to the SSC on strategic matters and priorities. The ANAO found instances where the board was not consulted or involved in decisions relating to the strategic direction, financial arrangements and expenditure priorities. Information reported to the board did not focus on areas of strategic importance and the quality and completeness of this information could be improved. These issues limit the board’s ability to effectively perform its strategic oversight role.

8. The mechanisms established for setting out responsibilities and obligations and ensuring transparency for services delivered by the SSC are weak. Service standards and levels are not fixed and can change. The delineation of responsibilities between the SSC and its clients is not clear and there was no commitment by the SSC to certify the quality of its control framework. In addition, operating on a cost-recovery basis requires the SSC to attribute all its costs for delivering services to its clients and all risk is transferred to clients in this process.

Supporting findings

Establishing the Shared Services Centre

9. While the governance arrangements were appropriate for the SSC’s establishment, the partner departments, SSC governance board and Finance have recognised that as the SSC expands; alternative governance arrangements will be required to provide additional assurance to clients.

10. In establishing the SSC, the partner departments set out to avoid the cost of separating the corporate and information technology functions. In this process the departments anticipated efficiencies and estimated savings, however at the time of the audit, the departments had not determined if efficiencies or savings had been realised. The departments should have advised Ministers of the arrangement from the outset and of the potential to expand service provision. Advice since the SSC’s establishment has been limited and could have been more comprehensive and timely.

11. The partner departments have sought central agency advice on the application of the Australian Government’s competitive neutrality policy to the SSC’s operations but have not formally assessed its application and have not briefed Ministers of their responsibilities in this respect.

12. The departments have conducted a number of review activities since the establishment of the SSC. There would be benefit in the departments conducting an evaluation of the SSC against its aims and objectives. This would assist the departments to determine if the arrangement is effective, efficient and delivering value for money.

Oversight of the Shared Services Centre

13. The SSC Governance Board (the board) was established to provide guidance to the SSC on strategic matters and priorities. Despite these responsibilities being defined in the board’s terms of reference, there are instances where the board was not consulted or involved in decisions relating to the SSC’s strategic direction and operational priorities. This has limited the board’s ability to oversight the activities and operations of the SSC. The absence of direct and independent lines of reporting between the board and its sub-committees has further diminished the ability of the board to fulfil its governance role.

14. There is limited alignment between the activities set out in the SSC’s strategic plan and the information reported in the SSC’s balanced scorecard reports. Although the board instructed that the SSC regularly report the status of major projects and initiatives, reporting is limited. The SSC measures its performance against its peers using benchmarks and reports this information to the board. Both the coverage and quality of this information is limited. The board received no information in relation to the SSC’s customer’s satisfaction levels, feedback and complaints.

15. Visibility of the SSC’s accounts and transactions has relied upon information provided by the SSC to the partner departments, the board and the sub-committees. The board has: no role in the budget process; limited visibility of expenditure; and limited ability to influence expenditure priorities. The arrangement is not consistent with the role envisaged for the board and limits its ability to make decisions and assess risk. The partner departments have taken steps to improve visibility of SSC transactions for budget purposes.

Service delivery assurance

16. The SSC formalises agreements with clients through a memorandum of understanding (MoU). These include limited detail of the obligations of the SSC and the mechanisms in place to support administration of the arrangement. These agreements did not include details of: the controls the partners and SSC have established to ensure; legislative compliance; governance arrangements; and the delineation of responsibilities between the SSC and its clients. In addition, there was no commitment by the SSC to certify the quality of its control framework and no protocol to share the outcome of audits or reviews of the SSC’s activities where findings and recommendations potentially impact clients.

17. The MoU specified that the board is to agree all changes to the services catalogue and service levels. The ANAO found inconsistent treatment of changes to service levels as well as inconsistent advice regarding authority to change service levels, with not all significant changes being referred to the board. There were also differences between the performance measures included in reports to clients and those specified in the services catalogue. The board’s sub-committees are intended to provide clients with assurance regarding decision-making, price-setting and performance. However, not all initiatives were referred to the sub-committees for consideration or decision and this has limited transparency for clients.

18. The transition to a new financial framework and details associated with the cost-allocation model were not considered by clients prior to agreement by the board. Formal arrangements to control and oversee the operation of the SSC’s financial framework and provide assurance of the accuracy of the SSC’s cost model; to monitor cost variations; and to control the SSC’s use of the risk contingency funds have not been established.

19. A business plan agreed by the departmental Secretaries in April 2016, forecast significant savings for clients of the SSC based on a four-fold increase in clients and an organisational transformation program. The SSC’s experience on-boarding new clients was limited at the time of the audit, with only two entities having joined the SSC. Achievement of these savings is also reliant upon transition to new governance arrangements.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.15 |

The Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training not expand the Shared Services Centre to take on additional clients until its future direction and supporting governance arrangements are settled. Department of Employment response: Agreed. Department of Education and Training response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 2.26 |

The Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training review the applicability of the Government’s competitive neutrality policy to the operations of the Shared Services Centre and inform the responsible Ministers of the outcome. Department of Employment response: Agreed. Department of Education and Training response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 3.37 |

The Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training strengthen the role of the board and its sub-committees and improve the quality of information and communication provided to the board. Department of Employment response: Agreed. Department of Education and Training response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 4.30 |

The Department of Employment, the Department of Education and Training and the Shared Services Centre put in place transparent and sound processes for agreeing performance and cost parameters with clients and for monitoring and reporting the Shared Services Centre’s performance against these. Department of Employment response: Agreed. Department of Education and Training response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

20. The department of Employment and Department of Education and Training provided formal comment on the proposed audit report as part of a joint response. The summary response is included below, with the full response provided at Appendix 1.

The original context for the Shared Services Centre (SSC) partnership between the Department of Employment and the Department of Education (the partners) has changed significantly in its three years of operation. What was originally an initiative way to avoid the costs of creating separate corporate support functions has become one of several designated providers in a whole of government Shared and Common Service Program (SCSP). The partner departments have for some time appreciated that such a role transforms the SSC from its original focus and purpose, and that the governance and operating model of the SSC would need to change. The ANAO audit has been undertaken throughout this period of changing context. During this time the partners have continued to pursue the evolution of the SSC to a more commercially oriented model, and to explore appropriate governance arrangements to support this.

The ANAO has observed this work, and acknowledged much of it in the final report. Many of the issues identified by the ANAO are fundamentally altered by the recently announced organisational changes to the SSC.

In relation to some specific issues in the report, the partners contend that they have kept portfolio Ministers appropriately informed of the SSC, noting the clear responsibilities of the departmental Secretaries for the corporate support arrangements of the departments. In relation to the application of competitive neutrality, the Departments note that the SSC has continued the arrangements that were in place for several years under DEEWR, and that they have relied upon advice from the central agency policy owners that competitive neutrality does not apply.

Finally, the advisory board has been effective in supporting the partner Secretaries in implementing the SSC as a partnership. The Secretaries have remained the accountable authorities, and have exercised their responsibilities jointly within the board, and their ordinary roles as Secretaries with the support of their departmental officers, engaging with each other and other stakeholders, outside of the board structure, as is appropriate given the non-executive nature of the advisory board.

21. The ANAO also provided the Department of Finance with the proposed report. Finance advised that they had no formal comment to make on the report and will consider the recommendations made by the ANAO when implementing the recently announced MoG change relating to the SSC.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 A shared services centre is an arrangement for the delivery of back-office support functions such as accounting, human resources, payroll, information technology, legal, compliance, purchasing and security. The arrangement can allow a number of organisations to share operational tasks, avoiding duplication and achieving economies of scale. Business models for shared services vary in respect to services delivered; governance structures; and levels of autonomy between the shared services centre and participating entities.

1.2 The Secretaries of the Department of Employment (Employment) and the Department of Education and Training (Education)4 established a shared services centre by agreement following changes to the Commonwealth machinery of government announced in 2013.5 The arrangement provided for the continuation of the information and communication technology (ICT) and corporate arrangements that existed when the two departments were combined.

1.3 The Secretaries sought to pursue efficiencies in the delivery of shared services and to avoid the cost of separating their departments’ corporate functions following the MoG changes. The Secretaries’ agreement also provided for service continuity to other ‘clients’ that the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) had supported, which in 2013 included a number of portfolio and non-portfolio entities. Box 1 lists the Shared Services Centre’s (SSC’s) existing clients at December 2013:

|

Box 1: Existing SSC customers, December 2013 |

|

Asbestos Safety and Eradication Agency Australian Public Service Commission Australian Skills Quality Authority Comcare Department of Industry Fair Work Commission Fair Work Building and Construction Fair Work Ombudsman IP Australia (ICT services only) Safe Work Australia Workplace Gender Equality Agency |

Source: SSC Board paper, Scope of the Shared services Centre, Agenda Item 3, 6 February 2014.

1.4 During the first year of the SSC’s operation in 2014–15, the SSC’s gross costs6 were approximately $108 million and revenue from clients was $14 million (13 per cent of costs). In 2015–16, gross costs were approximately $121 million, with client revenue of $18 million (15 per cent).

1.5 The agreement between the Secretaries identified the potential for the departments’ shared services centre to provide services ‘more broadly should other agencies be interested in joining’.7 Expansion of the SSC as a services provider gained momentum during 2015 in the context of a broader whole-of-government initiative to implement shared services across the Australian Public Sector (APS).8 The Secretaries updated their agreement in March 2016 with the aim of the SSC providing ‘shared corporate services for public sector customers and other customers more broadly’.9 In early 2016, the SSC had 14 key clients and a number of other entities consuming single and ad-hoc services. In 2015–16, revenue from entities that purchased single and ad-hoc services accounted for approximately 25 per cent of revenue received ($4.4 million).10

1.6 As part of further MoG changes which occurred in September 2016, core transactional services provided by the SSC will move to the Department of Finance.11 The entities have advised that most of the remaining services that benefit from being shared, and provided to current client entities, will move to Employment, with a small number to Education. The Departments are working towards a 1 December 2016 date for the transfer of functions, and in the meantime, the SSC will continue to operate as normal. The department has also advised that the partnership agreement and its associated governance arrangements, including the SSC Governance Board will not continue.

Shared services centre

1.7 The SSC is administered jointly by the departments of Employment and Education through a non-legally binding heads of agreement entered into by the Secretaries. The SSC is not a separate entity and forms part of the departments’ corporate functions.12 In 2015–16 the SSC comprised approximately 525 staff employed by one or other of the partner departments.

1.8 The SSC Governance Board (the board) oversees the strategic direction and priorities of the SSC. In addition to the Secretaries, the board has eight members. The Secretary of Employment chairs the board and the Secretary of Education is a member. The board is advisory and decisions relating to the SSC are taken jointly by the Secretaries.13 Under this arrangement the Secretaries continue to exercise their powers as the accountable authorities of their respective departments on the advice of the board in respect to SSC matters. The SSC’s clients are invited to participate in its governance as members of the board’s sub-committees.14

1.9 To manage governance and strategic matters relating to the agreement and matters of direct interest to the partner departments, the agreement provided for the formation of a Partners Forum. The forum includes representatives from the departments of Employment and Education, and the SSC. The partner departments have also established cooperative arrangements for internal audit of the SSC’s operations and the provision of legal services.15 An illustration of the governance arrangements as agreed by the board in April 2014 and in place at the time of this audit is included in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: SSC governance arrangements, August 2016(a)

Note a: The dotted lines indicate relationships with groups outside the agreed governance arrangements.

Source: Developed by the ANAO from information provided by the SSC, August 2016.

1.10 Management of the SSC’s daily operations is the responsibility of the SSC’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The CEO is an employee of Education and the terms of the CEO’s appointment are agreed by the board.16 Financial, human resource and legal authority may be delegated by the departmental Secretaries to the CEO. The CEO is required to operate under the ‘direction of, and be accountable to, the board in accordance with the agreed strategy and business plans.’17 The CEO is also required to report to the board on the SSC’s risks, fraud controls and performance.

Shared services in the public sector

1.11 There are examples of shared service initiatives in other jurisdictions, including almost every Australian state and territory and in the United Kingdom and Canadian governments. Various reviews of these arrangements have indicated that their performance has been mixed and that for the most part, the anticipated benefits and outcomes have not been achieved.18 There are also examples within the APS, including arrangements administered by the Department of Defence, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Health.

1.12 In late 2013 the Australian Government announced the Smaller Government Reform Agenda aimed at transforming the public sector through reductions in the number of government bodies and staff. Efficiencies were also sought through implementation of a contestability framework to assess whether particular government functions should be open to competition. Allied to this program is the Shared and Common Services Program administered by the Department of Finance (Finance) with oversight by the Secretaries Board. The Shared and Common Services Program was initiated based on recommendations from analysis undertaken by Finance during 2014 aimed at optimising the Government’s investment in enterprise resourcing planning systems (ERP systems)19 and recommendations made in a report presented to the Secretaries Board in early 2014.20

1.13 Tranche one of the Shared and Common Services Program involves the consolidation of core transactional services, including: accounts payable and receivable, credit card management, ledger management, pay and conditions and payroll administration. During 2015, each entity was required to identify whether it would be a consumer or provider of the tranche one services under the whole-of-government shared services initiative. Entities identified as providers were required to provide a business plan by April 2016, to be used by Finance to assess their viability and by other entities to select a preferred services provider.21 Employment and Education lodged the SSC 2016 Business Plan22 with Finance in April 2016.

1.14 The SSC’s business plan set out a proposal to expand service delivery to 10 more Commonwealth entities over the next two to three years, and to potentially further expand to cover 45 per cent of the Commonwealth public sector (excluding Defence).

Audit methodology

1.15 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s and the Department of Education and Training’s administration of the SSC to achieve efficiencies and deliver value to its customers.

1.16 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- governance arrangements incorporate sound oversight and planning;

- mechanisms have been established to ensure the effective delivery of services and the SSC’s ability to meet its commitments to customers to deliver value and ongoing efficiencies; and

- reporting arrangements and review activities provide for ongoing monitoring and continuous improvements to the operation of the SSC.

1.17 Arrangements were in place prior to establishment of the SSC in December 2013 involving service delivery to a number of DEEWR portfolio and non-portfolio agencies. The ANAO did not look at the origins of this arrangement and only examined the SSC from the period since December 2013, at the point of the machinery of government change. The ANAO did not review implementation of the wider Shared and Common Services Program. The program is referred to where it has influenced the SCC’s direction.

1.18 The ANAO reviewed departmental records and interviewed representatives of the SSC, Education and Employment. The ANAO also interviewed representatives of entities that purchase services from the SSC and other shared services providers in the Commonwealth public sector and in the States and Territories.

1.19 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $736 000.

2. Establishing the Shared Services Centre

Areas examined

This chapter examines the establishment of the Shared Services Centre (SSC) by the Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training, including whether the governance arrangements were fit-for-purpose; and anticipated savings have been realised. It also examines advice to Ministers, including with respect to the application of the Commonwealth’s competitive neutrality policy.

Conclusion

The department’s administration of the SSC has been effective for sharing resources between the departments and delivering selected back-office services to a small client base. However, the governance arrangements established to oversight the SSC have not positioned it well for the future and the departments have not yet determined if the arrangement is efficient and resulting in savings. In addition, responsible Ministers have not been well informed of the arrangements or their responsibilities in respect of competitive neutrality.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at mitigating the risk associated with the current governance arrangements and ensuring compliance with competitive neutrality policy.

2.1 The Shared Services Centre (SSC) was established following the announcement of machinery of government changes (MoG changes) in 2013 which transferred the functions of the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) to new departments, including the Department of Employment (Employment) and the Department of Education and Training (Education). Employment and Education (the partner departments) sought to maintain continuity through the SCC:

- in the delivery of their key internal business functions; and

- services provided by DEEWR to a number of external entities.

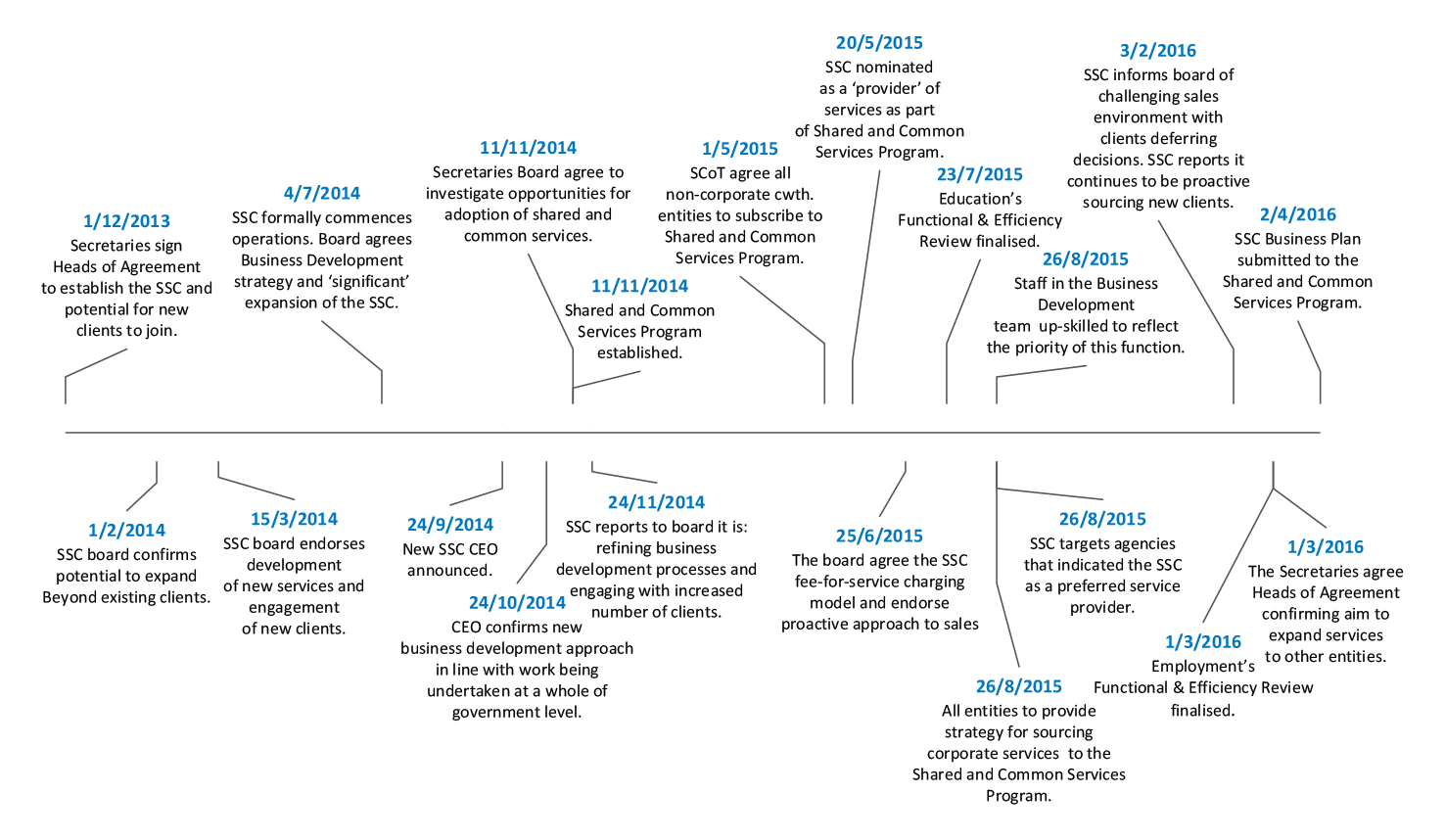

2.2 The partner departments also sought to position the SSC to be at the forefront of the whole-of-government shared and common services program led by the Department of Finance (Finance) and overseen by the Secretaries Board. From the signing of the two Secretaries’ agreement in December 2013, the partner departments allowed six months for the SSC to implement the necessary governance and operational arrangements. The SSC formally commenced operation from 1 July 2014. A timeline of events and decisions for the SSC, including some taken as part of the Shared and Common Services Program are shown at Figure 2.1:

Figure 2.1: Summary of key events and decisions in relation to the SSC, December 2013 to April 2016.

Source: ANAO analysis of SSC and Finance documentation.

Are the Shared Services Centre’s governance arrangements fit-for-purpose?

While the governance arrangements were appropriate for the SSC’s establishment, the partner departments, SSC governance board and Finance have recognised that as the SSC expands; alternative governance arrangements will be required to provide additional assurance to clients.

2.3 The SSC forms part of the partner departments’ corporate functions. It is not a stand-alone entity. The Secretaries’ agreement (clause 15.2) provided for the establishment of a governance board23 (the board) to be ‘responsible for providing oversight and guidance of the SSC in delivering shared and common services to Australian Public Service (APS) clients’.24 At the time these arrangements were established, the primary focus of the partner departments was to ensure that the SSC’s governance would support its establishment and provide transparency of decision-making for clients, particularly where these decisions impacted on the quality and costs of services being delivered.

2.4 The Secretary of Employment chairs the board and the Secretary of Education is a member of the board. The board has an advisory role, with decisions relating to the SSC taken by the Secretaries in recognition of their obligations and responsibilities under the PGPA Act. In effect, this arrangement allowed the Secretaries to continue to exercise their powers as the accountable authorities of their respective departments, on the advice of the board in respect to SSC matters. In April 2015, as a result of a review of the board’s functions and decision-making authority, the Secretaries empowered the board to make decisions, with the Secretaries able to veto these by exception.

2.5 The governance arrangements have been the subject of consideration by the Secretaries Committee on Transformation (SCoT), the governance board and Finance. The reviews have highlighted that the governance arrangements for the SSC will need to be reconsidered as the SSC further expands its activities.

Lessons learned

2.6 In a report to the SCoT, Finance identified lessons learned from shared services, including that:

- actual and perceived arms-length arrangements between the providers and customers is vital to the credibility of service providers;

- in the longer term there would be benefits in providers adopting alternative governance structures that better suit the nature of shared services.25

2.7 Reflecting on the experience of the SSC, Finance reported that the SSC’s operation as a ‘joint operation’ was ideal for its establishment, as it did not require significant investment and was able to leverage existing technology, skills and processes. Finance went on to report that as the ‘needs change and number of customers grows, the SSC requires more autonomy in planning for systems and process investments to achieve standardisation and process rationalisation’.26 Finance summarised the challenges associated with the SSC’s governance in the following terms:

This governance structure was effective when the SSC only serviced the two parent departments and a small number of additional customers. As the number of consuming agencies increases, the current governance structure of the SSC runs the risk of being insufficiently agile and innovative to service the needs of all customers.

The current governance structure may also limit the SSC’s ability to further mature, for example, issues could arise if the board is perceived to be acting in the interest of its parent Departments, instead of in the interest of all customers. A greater level of independence could be beneficial to all customers.

A known weakness of the current governance structure is the SSC’s lack of control over services revenue. The SSC is not an independent entity and its income and assets are managed jointly by the two partner departments. This creates difficulties with longer term strategic decisions.27

Consideration of alternative governance arrangements

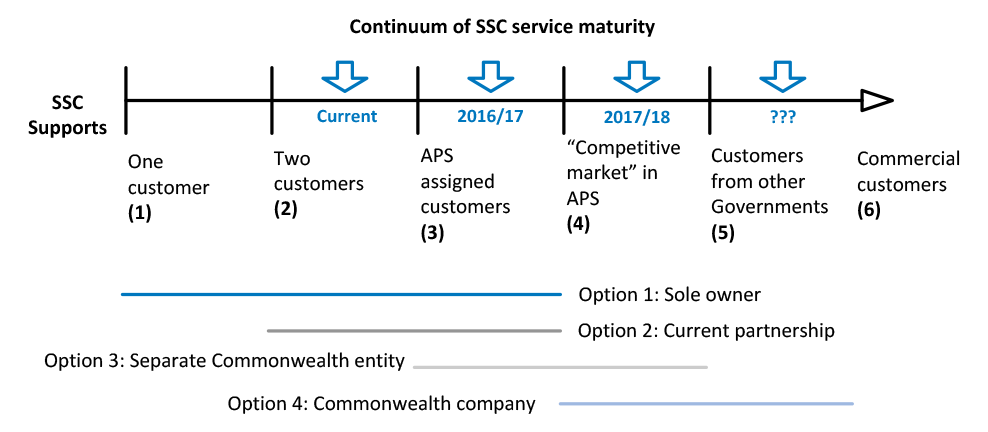

2.8 In April 2015, the board gave consideration to the SSC being a separate entity. The board tasked a working group to examine alternative governance arrangements and their suitability under different policy scenarios.28 The working group compared: the current arrangements; sole ownership; a separate Commonwealth entity; and a Commonwealth company.29 The working group’s final report (February 2016) identified key issues in determining the governance arrangements as: the future shared and common services environment; and the rate of SSC’s maturity development. Figure 2.2 shows the ‘most-likely’ future environment as depicted by the working group:

Figure 2.2: SSC ‘most likely’ future operating environment, February 2016

Source: Australian Government, Terms of Reference Working Group—Future Shared Services Centre Governance, February 2016.

2.9 The working group determined that the SSC’s likely future environment for the next financial year (2016–17) fell somewhere between points three and four, with the potential to move further to the right in the following financial years. The working group concluded that the current partnership arrangement would not suit the environments further to the right hand side of the scale. The report to the board recommended that a Commonwealth company (established under the Corporations Act 2001 and controlled by the Commonwealth) was the ‘most attractive longer term solution’30 and would aid in building a commercial culture and facilitate partnering and eventual sale. It was also noted that this arrangement closely aligned with the Government’s shared and common services agenda and offered commercial advantages, including:

- potential reduction in staffing costs through process improvement, automation and flexible non-APS employment arrangements31;

- ability to obtain investment funding;

- introduction of an equity partner; and

- engagement with the private sector to leverage expertise and capital to build maturity more quickly than would otherwise be possible.

2.10 The working group cautioned that transition to a Commonwealth company would require significant preparatory work, particularly given the need to transition employment arrangements from the Public Service Act 1999 and to ensure contracts were in place. The report noted that timing should be determined by the maturity of the SSC’s management systems and funding model, with the working group noting that there were risks involved ‘in transitioning to a separate entity while building and servicing a sustainable customer base’.32

2.11 The board agreed at its meeting in February 2016, that a decision could not be made until the outcome of the Shared and Common Service Program’s consideration of the role of the SSC as part of the whole-of-government shared service initiative was known.

2.12 In 2016, a review report by Finance to the Finance and Employment Ministers, that included examination of the SSC, highlighted three areas of potential concern with the SSC’s governance structure which were noted as cumulatively limiting the SSC’s ability to grow, these being:

- existing reporting requirements which limit accountability—as a jointly controlled operation, the SSC forms part of two departments. Both departments are required to report on the arrangement in terms of cost and income and do this through separating costs between the two of them. Clarity of reporting would enable entities to more readily become informed purchasers of corporate services.

- managing funding across portfolios risks friction between the partner departments particularly with respect to appropriations.

- new enterprise agreements leading to inequities within the SSC—the SSC does not employ staff, they are instead employed by one or other of the partner departments, inequities in pay and conditions could arise when enterprise agreements are negotiated and this could be viewed as unfair.

2.13 The report recommended that the SSC not outpace the whole-of-government shared services initiative and instead, that it should continue to consolidate its position and improve the cost and quality of its service offerings pending outcomes from the Shared and Common Services Program.

2.14 The partner departments advised the ANAO in August 2016 that:

The Secretaries are currently reviewing the SSC’s governance arrangements with the support of the SSC Governance Board. The Secretaries will not support any further expansion of the SSC’s customer base until the review of governance arrangements has been completed and recommendations have been implemented. The Secretaries have agreed that any proposal to expand the customer base needs to be backed by a thorough business case.33

Recommendation No.1

2.15 That the Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training not expand the Shared Services Centre to take on additional clients until its future direction and supporting governance arrangements are settled.

Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training response:

2.16 Agreed. The governance arrangements for services transferring to the Finance portfolio will be a matter for the Finance portfolio. The remainder of the services are to be provided to existing customers under the direct management of the Department of Employment or Department of Education and Training.

Were potential savings estimated and government approvals sought for the Shared Services Centre?

In establishing the SSC, the partner departments set out to avoid the cost of separating the corporate and information technology functions. In this process the departments anticipated efficiencies and estimated savings, however at the time of the audit, the departments had not determined if efficiencies or savings had been realised. The departments should have advised Ministers of the arrangement from the outset and of the potential to expand service provision. Advice since the SSC’s establishment has been limited and could have been more comprehensive and timely.

2.17 When the Secretaries established the SSC in December 2013, they entered into a resource sharing arrangement. The collaboration was expected to reduce costs and increase efficiencies through the consolidation and standardisation of processes. This was against the backdrop of previous work to harness improvements and efficiencies within the department-wide corporate functions of the former DEEWR. The departments considered that a full separation of the corporate functions would have had a significant cost impact, particularly in relation to the partners’ IT infrastructure and shared applications.

2.18 The partner departments estimated savings of around $5 million per annum for each department. The ANAO found that the partner departments had not determined if increased efficiencies had been realised through consolidation of processes or if any savings had been realised since the SSC’s establishment.

2.19 Section 19 of the PGPA Act states that an accountable authority must keep the responsible Minister informed of the activities of the entity and any subsidiaries of the entity.34 The Secretaries’ agreement reflected a continuation of the arrangements—including the provision of services to third-parties—in place under the former DEEWR. The departments should have advised responsible Ministers of the intention to continue the arrangements from the outset. Advice should have flagged the department’s intention to potentially expand the service provision to other Commonwealth entities.

2.20 The partner department’s records show that while advice has been provided to the responsible Ministers, this advice could have been more comprehensive and timely. Advice has comprised:

- a ministerial prepared by Employment to the Minister and the Assistant Minister for Employment in June 2014, proposing that they ‘note’ the implementation of the SSC;

- an incoming minister briefing for the Minister of Employment (September 2015); and35

- a ministerial briefing prepared by Education to the Minister for Education and Training in response to a request from the responsible Minister’s office (February 2016). The brief proposed that the Minister ‘note’ the information.

2.21 Separate to these briefings provided by the partner departments, the Minister for Employment and the Minister for Finance were provided with a report on outcomes of the Functional Efficiency Review in March 2016. This report included comprehensive information on the Shared Services Centre.

Was consideration given to the application of the Australian Government’s competitive neutrality policy?

The partner departments have sought central agency advice on the application of the Australian Government’s competitive neutrality policy to the SSC’s operations but have not formally assessed its application and have not briefed Ministers of their responsibilities in this respect.

2.22 The Commonwealth Competitive Neutrality Policy Statement36 (competitive neutrality policy) requires that a government business activity not enjoy net competitive advantage over their private sector competitors or potential competitors, by virtue of their public ownership. Where competitive neutrality arrangements are assessed as applying to a government business, pricing and accounting adjustments are required. Portfolio Ministers have responsibility for ensuring that competitive neutrality arrangements are implemented for all significant business activities within their portfolio.

2.23 The partner departments sought advice on competitive neutrality from Finance within the context of the Shared and Common Services Program in early 2015. At that time, the departments were advised that the competitive neutrality policy would not initially apply.37 By August 2015, as the Shared and Common Services Program progressed, Finance advised that shared services providers would need to ensure that they considered competitive neutrality and, where necessary, factor this into their prices.38

2.24 In July 2016, the partner departments sought formal advice from the Secretary of Finance in relation to assessing the applicability of competitive neutrality. The Secretary advised:

Providers deliver services on a cost-recovery basis, and there is no provision of services by private sector suppliers. In light of this, CN principles do not apply at this stage, though providing entities should undertake their own assessment to satisfy that this is the case in their own specific circumstances. Treasury has indicated that it also shared this position.39

2.25 At the time of finalising this audit report, the partner departments had not assessed the applicability of the Government’s competitive neutrality policy to the SSC and competitive neutrality had not been raised with responsible Ministers.

Recommendation No.2

2.26 The Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training review the applicability of the Government’s competitive neutrality policy to the operations of the Shared Services Centre and inform the responsible Ministers of the outcome.

Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training response:

2.27 Agreed. The application of the competitive neutrality policy to services transferring to the Finance portfolio will be a matter for the Finance portfolio.

Have mechanisms been established to evaluate the performance of the Shared Services Centre against its aims?

The departments have conducted a number of review activities since the establishment of the SSC. There would be benefit in the departments conducting an evaluation of the SSC against its aims and objectives. This would assist the departments to determine if the arrangement is effective, efficient and delivering value for money.

2.28 Evaluation activities are a core element of an entities’ performance assessment and are typically planned for at the design phase of activities so that appropriate consideration can be given to data requirements and availability. In many cases the effectiveness of a program may not be able to be assessed immediately from operational data and will require the analysis of results over time.

2.29 The departments have conducted a range of activities since the establishment of the SSC including: benchmarking analysis, customer surveys, process mapping and service level reporting. An evaluation of the SSC to determine the effectiveness and efficiency of the arrangement, and if it is delivering value for money had not been conducted. An internal audit of the SSC’s governance arrangements conducted by the Department of Education and Training during 2015 recommended development of an evaluation strategy. The SSC agreed to this recommendation and originally agreed to an implementation date of 30 June 2015 (this recommendation was reported as ‘problematic’ (Amber) at the June 2016 Audit Committee meeting). The SSC’s response to this recommendation noted:

The SSC has a number of existing mechanisms to evaluate numerous aspects of its performance. The existing benchmarking processes regularly assess the SSC’s organisational performance using industry standard benchmarks and provides these reports to the SSC Governance Board for each meeting. Service Performance reporting is undertaken on a monthly basis to determine the performance of individual services and their conformance with service level targets. Service performance reports are provided to the Business and Performance Sub-Committee.

The SSC conducts annual customer surveys to determine customers satisfaction with the services provided. The SSC undertakes process mapping as part of its continuous improvement activities to evaluate process performance and effectiveness. Reports are provided to the senior leadership and the SSC Governance Board. The SSC has now drafted an Evaluation Strategy that draws together the above performance assessments into a cohesive document which will be reviewed on a six monthly basis to ensure its relevance and effectiveness.40

2.30 The ANAO sought a copy of the evaluation strategy noted in the above response and was informed that it was not available.

3. Oversight of the Shared Services Centre

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the existing oversight arrangements and whether the Shared Services Centre (SSC) Governance Board (the board) is adequately supported in line with the partner’s commitment to clients.

Conclusion

An advisory board provides guidance to the SSC on strategic matters and priorities. The ANAO found instances where the board was not consulted or involved in decisions relating to the strategic direction, financial arrangements and expenditure priorities. Information reported to the board did not focus on areas of strategic importance and the quality and completeness of this information could also be improved. These issues limit the board’s ability to effectively perform its governance role.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at strengthening the role of the board to oversee and guide the SSC on behalf of all the SSC’s clients.

3.1 The Secretaries’ Heads of Agreement (HoA) (clause 15.2) provided for the establishment of the SSC Governance Board (the board).41 The board met for the first time in 2014.42 The agreement between the Secretaries confirmed the role of the board as follows:43

The SSC Governance Board will be responsible for providing oversight and guidance of the SSC, in delivering shared and common support services to Australian Public Service clients, including:

a) Supporting the long-term viability of the SSC in the context of the whole of government shared services agenda

b) Championing the shared services agenda across Government and supporting the growth of the SSC

c) Providing advice, guidance and monitoring the operations of the SSC.44

3.2 The membership of the board is set out in the board’s terms of reference and comprises the Secretaries, four client agency representatives and an independent member. A representative of the Department of Finance (Finance) and the Australian Public Service Commissioner are also on the board. The board’s membership was intended to provide: expertise in public sector finance, governance and management; advice on the whole-of-government shared services agenda; client representation; and an independent member who would provide private sector business expertise. A list of the board members as at April 2016 is at Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Members of the SSC board, April 2016

|

Member |

Details |

|

Chair |

Department of Employment Secretary |

|

Member |

Department of Education and Training Secretary |

|

Member |

Australian Public Service Commissioner |

|

Member |

Deputy Secretary, Department of Finance |

|

Client representative |

Deputy Secretary, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

|

Client representative |

CEO, Fair Work Ombudsman |

|

Independent member |

External to the Australian Public Service |

|

Ex-Officio(a) |

CEO, SSC |

Note a: The SSC CEO is a voting member of the board and a member of the board’s quorum.

Source: Information provided by the SSC, April 2016.

3.3 The board’s terms of reference provide for the establishment of governance arrangements to assist it to perform its role. At its first meeting in February 2014, the board established the following sub-committees to operate under its authority:

- Information Technology (IT) sub-committee to focus on IT related issues; and

- Business Performance sub-committee to focus on the SSC’s performance, business development and service strategy.

3.4 SSC’s clients are invited to participate as members of the board’s sub-committees to provide clients with transparency in decision-making and with a direct line of communication to and from the board.

Does the governance board have sufficient involvement in decision-making for it to effectively fulfil the role defined for it?

The board was established to provide guidance to the SSC on strategic matters and priorities. Despite these responsibilities being defined in the board’s terms of reference, there are instances where the board was not consulted or involved in decisions relating to the SSC’s strategic direction and operational priorities. This has limited the board’s ability to oversight the activities and operations of the SSC. The absence of direct and independent lines of reporting between the board and its sub-committees has further diminished the ability of the board to fulfil its governance role.

3.5 In March 2014, the board agreed a vision and mission statement45 for the SSC. The board also agreed the following objective statement and operating principles:

To be known as the preferred provider of professional, efficient and quality services that enable the customer to focus on their core business.

Operating principles:

- Understand and respond to the needs of our customers.

- Be innovative and continuously improve services.

- Be transparent and accountable for the work we do.

- Foster a professional and capable workforce.

- Respect and value our staff and uphold the values of the APS.46

3.6 The Secretaries HoA set out that the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) was to operate and be accountable to the board in accordance with agreed strategic and business plans. During 2014, the SSC focused on setting out the strategic direction of the SSC’s IT capability through development of the following:47

- SSC IT Strategic Direction 2014–1548 (August 2014)—sets out how the IT teams would respond to the challenge of the SSC’s vision of delivering a world-class service. A timeline for development of a longer term IT strategy (mid-2015) was to be developed in consultation with clients, staff and vendor seminars.

- SSC IT Capital Investment Plan 2014–15 to 2017–1849—developed to support the strategic direction of the SSC and to inform investment decisions. This plan was used by the SSC to inform IT investment decisions for 2014–15 and 2015–16.

3.7 In June 2015, the board agreed the first formal strategy documents for the SSC. These included the SSC’s strategic plan; IT strategy; and a marketing and growth strategy. The strategies referred to a new vision for the SSC ‘Leaders in exceptional and innovative shared services solutions’ and are framed against four ‘strategic pillars’. The strategic pillars included:

- a high performing organisation;

- operational excellence and improve productivity;

- continuous improvement; and

- commercialising our partner model.

3.8 The strategies and plans were high-level providing limited detail of proposed activities. Where activities were identified, information including their purpose, benefits and the timeframe for completion were not detailed. In addition, the strategy documents did not propose any performance measures for each of the strategic pillars or against any of the proposed activities.50

3.9 The process for approval or endorsement of the SSC’s plans and strategies has varied, with not all documents going to the board and/or its sub-committees for review or endorsement. For example:

- the final IT strategic direction and capital investment plan were presented to the IT sub-committee in August 2014 for its members information only. These documents have not been provided to the board; and

- the SSC’s strategic plan; IT strategy; and marketing and growth strategy were provided to the board for agreement in June 2015. There is no record of the sub-committees reviewing these documents prior to their submission to the board and of the board seeking the sub-committees’ input as part of its consideration and endorsement of these documents.

3.10 In April 2016 the partner departments agreed and delivered the SSC business plan to Finance for its consideration. The SSC business plan made reference to the strategic plans agreed by the board in June 2015 and identified activities under each of the strategic pillars. The activities listed in the business plan do not align with those included in the original strategy document. The business plan also provided details of the ‘future SSC’ outlining features that included amongst other activities: consideration of options for full or partial private sector investment; a high volume Standard Processing Centre51; and use of a mix of APS and non-APS staff. None of these activities were outlined in the strategy documents agreed by the board in June 2015 or in documents provided to the board or the sub-committees since.

3.11 Also included in the SSC business plan was a statement by the partner departments that the SSC would reduce the cost of corporate services to all its clients by over 30 per cent through expansion of its client base and a program of organisational transformation. Details of the transformation program and proposed cost savings as well as financial forecasts and volumes data, were not considered or agreed by the board or sub-committees prior to the business plan being proposed to Finance.

Advisory role of the sub-committees

3.12 When the board established the sub-committees, it confirmed their role as ‘advisory’ and that ‘significant decisions’ would be bought to it for consideration. The board appointed the CEO as Chair of both sub-committees and specified direct reporting lines between the sub-committees and the board.52 The terms of reference for each sub-committee specify that the sub-committee:

is responsible and accountable to the Shared Services Centre Governance Board for the exercise of its responsibilities. The sub-committee will report to the board, and the [sub-committee] Chair will provide a verbal update at the Board as needed.53

3.13 In practice, the flow of information between the sub-committees and board is through the CEO. There was no standing agenda item at board meetings for the sub-committees to report to the board, either verbally or through a written report. The SSC’s records show that papers and reports prepared by the SSC on topics relevant to the sub-committees were not as a matter of course, agreed by the sub-committees prior to being provided to the board.

Does the governance board have access to the right information to effectively fulfil the role defined for it?

There is limited alignment between the activities set out in the SSC’s strategic plan and the information reported in the SSC’s balanced scorecard reports. Although the board instructed that the SSC regularly report the status of major projects and initiatives, reporting is limited. The SSC measures its performance against its peers using benchmarks and reports this information to the board. Both the coverage and quality of this information is limited. The board received no information in relation to the SSC’s customer’s satisfaction levels, feedback and complaints.

3.14 The board’s terms of reference specify for it a role in advising, guiding and monitoring the operations of the SSC. This included a role in respect of organisational design and capability; the SSC’s performance; areas for improvement; management of strategic risks and issues; and the status of the major program of works. Throughout the course of this audit the board was informed of the SSC’s operational performance and progress through the balanced scorecard report and the program of works report.

Balanced scorecard

3.15 The balanced scorecard report provides a basic overview of the SSC’s performance in terms of: service levels achieved; financial performance; staff information; and benchmark measures. The board tasked the Business Performance sub-committee with development of the report on its behalf. The design of the scorecard report was agreed by the board in May 2014 and specified a report framed against the SSC’s objectives and supported by a tiered reporting regime that was to include strategic, tactical and operational measures. The SSC’s records show that the development of the balanced scorecard was constrained due to limited availability of data and as a consequence, it was agreed with the board that development of the report would be iterative as these challenges were addressed.

3.16 In June 2015 the balanced scorecard was reframed against the strategic pillars outlined in the SSC strategic plan. The board was informed this format was intended to support the board’s discussions as the SSC moved forward with the new strategy of growth, commercialisation and customer service. Table 3.2 compares the activities reported in the SSC’s strategic plan (agreed by the board in June 2015) and data reported as part of the SSC’s balanced scorecard report.

Table 3.2: Comparison of strategic plan and balanced scorecard by strategic pillar

|

SSC Strategic Plan ‘Our Strategies’ |

SSC balanced scorecard report, February 2016 |

|

High performing organisation |

|

|

|

|

Operational excellence and improved productivity |

|

|

|

|

Continuous improvement |

|

|

|

|

Commercialise our partner model |

|

|

|

Source: Extract from the balanced scorecard report provided to the board at its meeting in February 2016 and the SSC Strategic Plan 2015–17.

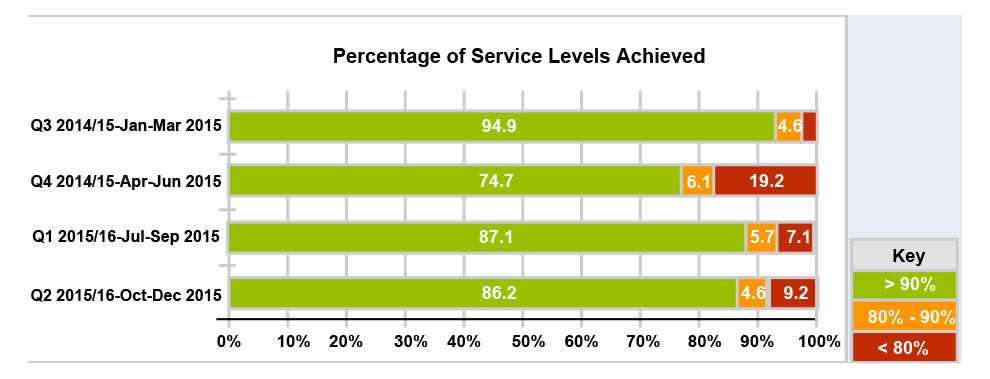

3.17 Commentary accompanying the balanced scorecard focused on describing movements during the period over which the information is presented. There was no analysis of trends or the impact of issues. Box 2 provides an extract of the SSC’s reporting to the board in February 2016, on its achievement against service levels:

|

Box 2: Balanced scorecard report service levels achieved, February 2016 |

|

The SSC’s achievement against services levels is aggregated, which does not provide the board with visibility of which, and how many services levels are being reported against. The balanced scorecard reported the SSC had service levels for 65 per cent of its services. Analysis of the SSC’s performance data used to compile this graph showed that only 27 per cent of services levels are reported on each quarter by the SSC. |

3.18 As noted in paragraph 3.15, the balanced scorecard report included information relating to SSC staff. Unscheduled absence data is shown for 2015–16 and compared with year–to–date APS data for 2013–14, although 2014–15 data is available both at the whole of the APS level and by organisational function. Relatively static measures, such as staff gender and diversity are displayed over a four-month period, with no comparative data or targets against which to measure performance. Baseline data that compares staff metrics and performance year–to–year or to compare the SSC with similar public sector or service delivery organisations or targets against which to measure progress was not included.

3.19 The balanced scorecard does not provide details of customer satisfaction levels; the SSC does not have a formal complaints management process; and does not conduct regular customer satisfaction surveys. The board agreed in early 2014 the SSC would initiate work to establish a regular client satisfaction survey that would allow it to report levels of client satisfaction on a regular and ongoing basis to the board. A single survey was conducted in June 2014. It was agreed not to repeat the survey and that the SSC would develop and conduct regular in-house surveys. A series of three satisfaction surveys were planned and agreed by the board in 2015: a survey targeted to senior executive level; front of house staff (targeting non-executive client staff members); and an ongoing point in time survey to survey clients after a service has been consumed. Only the first two surveys were undertaken. Responses to these surveys were not analysed until December 2015 and further surveys have not been undertaken.

Program of works report

3.20 The program of works report informed the board of the SSC’s progress on major projects it was undertaking to develop internal capability or as part of delivering services to clients. The ANAO found that although the board had agreed the criteria for determining which projects it would oversight, information contained in the program of works report did not reflect this. The SSC was required to include projects in the program of works report based on whether they were:

- high visibility to partner(s) / customer(s); or

- a major investment (cost > $400,000); or

- cross-SSC impact; or

- leading edge innovation.

3.21 The ANAO found that of the 17 IT projects approved for funding in 2014–15, ten had budgets that exceeded $400 000. Only two of these projects were included in the program of works report to the board.

3.22 For 2015–16, only three of the 24 IT projects approved for funding during this period were included in the report to the board, although the budget for 16 of these projects exceeded the $400 000 threshold. In addition, three key projects were removed from the program of works report (between the November 2015 and February 2016 board meeting) and no update was provided to the board regarding the status of projects, or whether they were finalised.

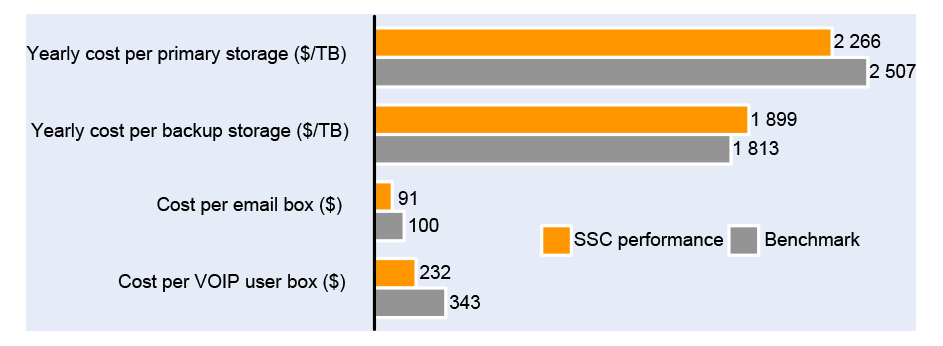

Benchmark reporting to the board

3.23 To allow the SSC to demonstrate to potential clients that it can provide value for money, the SSC has developed benchmark measures that focus on specific aspects of the services it delivers.54 Work to compile benchmarks commenced in early 2014 and the challenge in finding suitable measures and for the SSC to compile data and reports was raised with the SSC’s board in November 2014. It was agreed that benchmark reports should focus on the SSC’s most critical services and that new benchmarks would be incorporated into the reports as they became available.

3.24 While the number of benchmarks reported by the SSC had gradually increased, coverage across the SSC’s services was limited and most benchmarks were operationally focused. In February 2016, the SSC reported benchmark data for the measures shown in Table 3.3. A subset of these measures was also reported to the board as part of the balanced scorecard report.

Table 3.3: SSC’s available benchmark data for core services, February 2016

|

Service |

Benchmark |

|

Payroll |

Usage of self service by employees |

|

Full cost per payslip(a) |

|

|

Level of re-work required(a) |

|

|

Finance |

General ledger – month end close(a) |

|

Days to close books |

|

|

Days to report results |

|

|

Accounts payable |

Cost per invoice raised(a) |

|

Invoices processed per accounts processing full-time employee |

|

|

Accounts receivable |

Cost per invoice raised(a) |

|

Service desk |

Average abandonment call rate |

|

Average time to queue |

|

|

Average talk time |

|

|

Average wrap up time |

|

|

Average hold time |

|

|

Average handling time |

|

|

Internet gateway |

Unit cost per gigabit of traffic(a) |

|

ICT storage |

Utilisation of installed storage capacity(a) |

|

Annual cost per allocated backup storage per terabyte |

|

|

Annual cost per allocated primary storage |

|

|

ICT email |

Cost per email box |

|

Cost per email user |

|

|

Messaging service availability |

|

|

ICT general |

Backup success rate(a) |

|

Cost per window server image(a) |

|

|

Cost per voice/VOIP user |

|

Note a: These benchmarks are also reported at each board meeting as part of the balanced scorecard report.

Source: SSC Board paper, February 2016.

3.25 During 2015, benchmark information provided to the board compared SSC data compiled on a monthly basis with industry data compiled on an annual basis. While the SSC informed the board in February 2016 that it had moved to ‘six-month rolling’ reporting to better illustrate trends, in some instances, the data reported to the board was unchanged from that previously reported.

3.26 The SSC compared its performance for payroll and financial processing using benchmarks developed as part of the benchmarking exercise with peers within the Australasian region in late 2014. This study used 2013–14 data and the results were made available in December 2014.55 The benchmark study used a small sample of participants (14 participants) from a mix of private and public-sector organisations servicing varied industry types. The scale of the operations of participants also varied considerably. For example, 50 per cent of participants in this exercise reported they provide support for organisations with employee numbers greater than 20 000 and 70 per cent of participants reported they support organisations with revenue/operating budgets in excess of $5 billion.56 In its benchmark reporting for payroll and financial services, the SSC compares it performance to the ‘mean’ result calculated as part of this study.

3.27 Two of the IT related benchmarks compare the SSC’s performance against data sourced from Finance’s annual benchmark survey for 2012–13, although 2013–1457 data was published in April 2014 and benchmark results for 2014–15 were released in December 2015. The SSC compiles and reports on more than 70 benchmark measures as part of its contribution to the annual benchmark survey conducted by Finance, only nine IT benchmarks are reported to the board. Using benchmarks compiled annually as part of the Finance benchmark survey would potentially allow the SSC to report benchmarks measures for all the SSC IT functions (including management and administration) and further allow the SSC to more extensively benchmark its ICT capability against its peers within the public sector.

3.28 With limited performance information available, it is difficult to verify whether improvements against benchmarks reported by the SSC reflect changes in their calculation, or are the result of improvements in efficiency and service quality. The SSC does not have a complaints management system or regular client surveys to measure and report on client satisfaction levels and at the time of finalising this report most of the SSC’s clients were in the process of transitioning to a more accurate cost-allocation model for calculating the cost of the SSC’s services.

Examination of Shared Services Centre performance

3.29 The SSC’s performance was examined as part of a Finance review conducted in late 2015 (see paragraph 2.12). The review examined the SSC’s performance (relating to payroll, finance and IT) using benchmarks provided by the SSC and benchmark data compiled as part of the Shared and Common Services Program using data from other APS service providers to determine whether the SSC’s performance has scope for improvement through contestability.58 The review noted concerns expressed by Employment regarding the quality of the benchmarks due to lack of clarity around the methods of calculation. In the absence of alternative benchmarks, the review deemed these sufficient to assess potential future efficiencies.

3.30 The review’s report noted that the SSC’s primary competitive advantage against private sector corporate services providers was that it was a government provider and that where the SSC drove efficiencies the Commonwealth retained these benefits. The SSC had not achieved a significant market share for the services in which it had performed below industry benchmarks. The review noted that this indicated that the SSC’s status as a trusted provider did not outweigh the concerns of potential customers about service levels and costs.

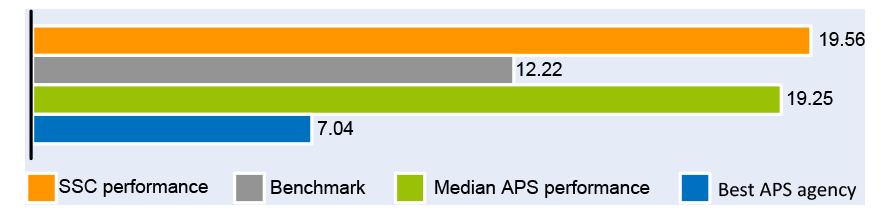

3.31 The final report stated that increasing contestability for the SSC’s financial services was the most viable way to improve performance outcomes for agencies and recommended four broad approaches that would align the SSC more closely with the Shared and Common Services Program vision for increased shared service use. These were to: improve internal performance; compel government agencies to use shared service providers; attract further engagement emphasising the SSC’s strength as a trusted provider; and engage in market testing and service brokerage to achieve efficiencies through private sector engagement. The review’s benchmark analysis is summarised in Box 3:

|

Box 3: The Shared Services Centre’s performance |

|

The review compared the SSC’s performance against: other providersa; the best APS agency; and the median APS performance.b The review examined the SSC’s performance processing payroll, both in terms of costs and re-work; and the costs of processing accounts payable and accounts receivable. This comparison showed that the SSC’s performance in delivering payroll services was below benchmark—with the SSC’s cost per payslip marginally below the APS mean and significantly higher than both the best performing APS agency and the provider means. Comparison of the cost per payslip is shown in the following figure(a):

The comparison of the percentage of payslips requiring re-work showed the SSC either meets or marginally falls short of benchmarks for the percentage of payslips requiring re-work. The SSC’s results against these benchmarks suggested that it was both more expensive and less consistent than other providers from outside the Commonwealth. The SSC’s processing costs for accounts payable and accounts receivable were also higher than benchmarks, with the results showing significant scope to reduce process costs. The review concluded that these factors indicate that the SSC provided financial services (including accounts payable, accounts receivable and payroll) less efficiently than the other benchmarked shared services providers and requires a greater level of rework. The review’s comparison of the SSC’s IT services was more favourable with the SSC meeting or exceeding benchmarks for: storage utilisation; primary storage costs; cost per email box; cost per email user; backup success rate; cost per window server image; emailing service availability; and, VOIP (voice over internet protocol) cost per user. The SSC did not meet benchmarks for: cost of gateway per gigabit used; and, backup storage costs. The review noted that this illustrated that the SSC performed more strongly than benchmarks in relation to providing services at a competitive price. The SSC’s performance against IT benchmarks is shown in the following figure(c):

|

Note a: This benchmark data was provided by the SSC and used data from the benchmark study undertaken by the Australasian Shared Services Association (ASSA) that the SSC participated in during 2014 (refer to paragraph 3.26). This data included private, state and territory, and Commonwealth shared services providers.

Note b: APS data was compiled by the Department of Finance as part of the Shared and Common Services Program.

Note c: Compiled by the ANAO using data provided by the SSC.

Have the partner departments put in place oversight mechanisms to ensure visibility over the Shared Services Centre’s budget and expenditure?

Visibility of the SSC’s accounts and transactions has relied upon information provided by the SSC to the partner departments, the board and the sub-committees. The board has: no role in the budget process; limited visibility of expenditure; and limited ability to influence expenditure priorities. The arrangement is not consistent with the role envisaged for the board and limits its ability to make decisions and assess risk. The partner departments have taken steps to improve visibility of SSC transactions for budget purposes.

3.32 The SSC is not a stand-alone entity59 and its budget is provided by the partner departments who allocate a share of their capital budgets to the SSC and share between them operating costs and revenues. The Secretary of each partner department is the accountable authority under the PGPA Act.60 The SSC’s financial arrangements are detailed in the SSC Financial Policy61 (the financial policy). The partner departments agree the SSC’s budget as part of an annual budget cycle. This process commences in February each year when the SSC provides the partner departments with its budget forecasts and the underpinning assumptions supporting these. The partner departments aim to finalise the SSC budget following release of the Federal Budget in May each year.

3.33 Each department’s contribution to the SSC is calculated using the relative share of total staff to the number of users as a proxy for usage.62 Funds provided by the partner departments are allocated to ‘managed accounts’ or the SSC’s ‘operational budget’63, reflecting their different treatment. The financial policy states the managed accounts are the sole responsibility of the partner departments and cannot be used for the SSC’s operational budget.64 The financial policy states that the ‘SSC will be provided with sufficient operational flexibility to manage its SSC operational budget.’

Financial information to the board

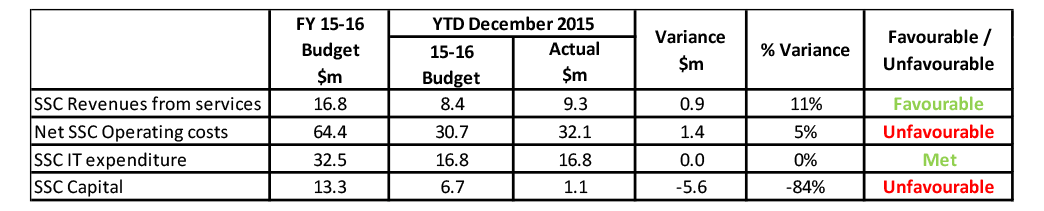

3.34 The balanced scorecard report provided the board with high-level financial information and tracked the SSC’s year-to-date expenditure and revenue. A breakdown of cost components or the impact of initiatives on the SSC’s budget was not provided. This limited the board’s ability to assess the SSC’s financial position and in turn, to query expenditure; make decisions; and assess risk. Figure 3.1 shows financial information presented to the board as part of the balanced scorecard report at each meeting:

Figure 3.1: SSC financial data reported to board, February 2016

Source: Extract from the balanced scorecard report provided to the board at its meeting on February 2016.

3.35 The financial policy provides for the SSC to determine its forecast IT investment relating to application development, infrastructure enhancement and capital investment in collaboration with the board’s IT sub-committee. The SSC’s records show that for the processes undertaken to determine IT investment for 2014–15 and 2015–16, the board was not briefed on the outcome or provided with details of the final suite of IT projects prior to these being proposed to the partner departments for their consideration. In addition, for 2015–16, details of these projects were not included in the SSC’s IT strategy agreed by the board in June 2015. The SSC informed the board at the time, that the strategy reflected the SSC’s ‘vision’ for the 2015 to 2017 period and that detailed business plans would be developed later, once the leadership team was established.

3.36 The SSC has been able to fund some initiatives using funds from a ‘managed’ account referred to as the Corporate IT Account (CITA).65 This expenditure was not visible to the partner departments as the partner departments did not have access to the SSC’s financial systems. The partner departments and members of the IT sub-committee requested details of the CITA account expenditure and transactions in late 2014 and during 2015. The partner departments delayed finalisation of the SSC’s 2015–16 budget until November 2015 pending this information being provided by the SSC. A minute from Education outlining the SSC’s 2015–16 budget described this delay in the following terms:

… initial high level allocations were provided to the SSC in December 2014 and again in July 2015. The SSC sought additional funding and the partner departments requested detailed information to support the increasing [sic] funding, in particular in relation to the Managed IT account and IT capital. A detailed breakdown of forecast expenditure for the Managed IT account was not provided to the partner departments until November 2015.66

Recommendation No.3

3.37 The Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training strengthen the role of the board and its sub-committees and improve the quality of information and communication provided to the board.

Department of Employment and the Department of Education and Training response:

3.38 Agree that improvements be made to the quality of information used in the future governance arrangements. The governance arrangements for services transferring to the Finance portfolio will be a matter for the Finance portfolio. The remainder of the services are to be provided to existing customers under the direct management of the Department of Employment or Department of Education and Training.

4. Service delivery assurance

Areas examined