Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Design, Implementation and Monitoring of Health's Savings Measures

Please direct enquiries relating to potential audits through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the department’s design, implementation and monitoring of select 2014–15 and 2015–16 Budget measures aimed at achieving $1.2 billion in savings and other benefits.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In 2017–18 the Australian Government budgeted $75.3 billion on healthcare representing around 16 per cent of all expenditure. Key drivers of health expenditure are Australia’s growing and ageing population, as well as the increasing prevalence of chronic disease and the use of new, but costly technologies in the treatment of illness. In recent years, the Government has pursued a range of strategies to manage the growth in costs of health services and to increase the efficiency of health administration.

2. Following the 2013 election, the Australian Government established processes to examine the appropriate role and scope of government activity as part of its Smaller Government Reform agenda. A series of ‘portfolio stocktakes’ were undertaken across government under the Efficiency through Contestability Programme instigated by the Minister for Finance. A Functional and Efficiency Review (FER) of the Department of Health (Health or the department), conducted between January and March 2015, made 90 recommendations for clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the department and increasing the efficiency of its operations. The review formed the basis of significant Budget savings.

3. The Department of Health is responsible for implementing the Australian Government’s health priorities. The role of the department is to provide high quality advice to the Minister for Health on how the Government’s objectives can be met and to action the Government’s decisions in line with its overall policy agenda. Within the context of the annual Budget this involves developing policy options for the allocation of funding to give effect to the Government’s priorities.

4. In the 2014–15 and 2015–16 Budgets, the health portfolio committed to deliver $1.2 billion in savings over the forward estimates through a number of measures aimed at achieving the Government’s objectives for fiscal constraint. The measures encompassed:

- election commitments to reduce duplication in spending by abolishing two small agencies established under the previous government;

- administered program measures where funds were to be returned to Budget or reallocated to other health policy or program priorities; and

- departmental measures which were to increase the efficiency of the department’s activity.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. Health’s management of savings measures was selected for audit because of the scale of health expenditure and the importance of sound financial management for the Australian Government’s overall fiscal position. Sound decision-making and the effective implementation of health savings supports the ability of the Government to maintain service provision into the future. Health has not reported on the impact of the savings measures on its delivery of programs through its annual reports or other means. The audit therefore provides information to Parliament about the status of the Budget measures and has the potential to inform the management and reporting of savings measures by other entities.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the Department of Health’s design, monitoring and implementation of select 2014–15 and 2015–16 Budget measures aimed at achieving significant savings and other benefits. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Were sound processes and practices established to support the design and implementation of specific measures?

- Is the achievement of savings and benefits being appropriately monitored?

- Is implementation of the measures on track?

7. The budget measures are set out below.

Budget 2014–15

- Smaller Government: Australian National Preventive Health Agency ($6.4 million over five years from 2013–14, departmental)

- Smaller Government: More Efficient Health Workforce Development ($142 million over five years from 2013–14, departmental).

Budget 2015–16

- Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs ($962.8 million over five years from 2014–15, administered)

- Smaller Government: Health Portfolio ($113.1 million over five years from 2014–15, departmental).1

Conclusion

8. The Department of Health was effective in designing the Government’s savings commitments. While administered savings were effectively implemented and monitored, the department lacked appropriate arrangements to monitor the implementation and impact of departmental efficiency savings.

9. Health used generally sound processes and practices to support the design and implementation of savings measures. The design of measures was consistent with guidance provided by the Department of Finance and the department’s internal budgeting processes. Advice to the Government to inform decision-making on the nature and extent of savings to health spending was relevant and timely.

10. The achievement of savings and benefits has not been sufficiently monitored. The department did not have robust information management systems in place to enable it to produce accurate reports on the status of grants from administered funds. Since the 2015–16 Budget the department has improved its governance arrangements for the management of administered appropriations and strengthened its systems for tracking grant expenditure. Health’s monitoring of departmental savings measures focused on high-level information about implementation activities and did not include information about reductions in operating costs or the achievement of specific benefits.

11. The department made appropriate adjustments to internal administered and departmental budget allocations to reflect the Government’s decision-making. The department did not establish arrangements to inform itself of the extent to which the intended benefits of efficiency measures had been realised.

Supporting findings

The design of measures

12. Health developed administered savings options in line with guidance provided by Finance. It designed measures, in the first instance, by drawing on uncommitted funding, consistent with its internal budgeting processes. In identifying further opportunities for savings, the department was responsive to the Government’s priorities and developed proposals based on policy considerations and program evidence. In designing departmental savings measures Health did not develop costings for all efficiency measures. There is merit in Health strengthening its approach to quantifying potential savings and establishing baselines for measuring their impact on efficiency during implementation.

13. Advice provided to government on administered savings was appropriate, regular, and reflected the Government’s policy and fiscal objectives. Health informed the Minister of its response to Functional and Efficiency Review (FER) recommendations and proposed a range of departmental efficiency measures. The department did not provide further briefing to the Minister on matters arising from the FER, including in relation to further work and consultation that it had committed to undertake. Health’s advice to the Government to support the abolition of the Australian National Preventive Health Agency (ANPHA) and Health Workforce Australia (HWA) was relevant and timely and included options for managing risks.

14. The department’s planning for the implementation of administered savings was generally appropriate, except for the lack of a coordinated strategy for engaging external stakeholders. The department has undertaken work since 2015–16 to improve its Budget stakeholder engagement processes. While departmental measures were incorporated into portfolio-wide plans for organisational change, Health did not undertake sufficient project planning for the measures in relation to implementation risks and mitigation strategies. The department developed timely, fit-for-purpose plans to support the abolition of ANPHA and HWA.

Monitoring of savings and benefits

15. Health used appropriate oversight arrangements to monitor the implementation of administered and departmental measures.

16. The oversight arrangements for departmental savings were undermined by a lack of appropriate measures to monitor the progress of implementation and its impact. The integration of efficiency measures into the department’s broader change program (Health Capability Program) reduced visibility of the department’s progress in achieving the efficiency outcomes.

Implementation and outcomes

17. Health made internal financial adjustments to give effect to the Government’s savings decisions. The department did not fully implement all of the efficiency measures included in the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio budget measure. In line with the Government’s decision to reduce duplication, ANPHA and HWA were abolished by the end of 2014–15 and functions were transferred to the department. However, the department has generally not retained documentation on performance outcomes.

18. The savings measures contributed to the Government’s fiscal agenda by reducing funding for programs, activities and departmental functions. In the absence of reliable information the department is unable to assure itself of whether efficiencies have been achieved. The abolition of ANPHA and HWA reduced duplication in the delivery of health workforce and preventive health functions.

Recommendation

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.19

That the Department of Health apply fit-for-purpose performance criteria to assist it to monitor the implementation of savings measures and assess their impact.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

Summary of the Department of Health’s response

The Department of Health notes the audit findings and agrees with the recommendation. I am pleased that the ANAO concluded that Health was effective in designing the Government’s savings commitments, and that it used generally sound processes and practices to support the design and implementation of savings measures.

The audit acknowledges the steps taken by Health since the 2015–16 Budget to improve its governance arrangements for the management and strengthening of systems for tracking administered expenditure, as well as work undertaken to improve the Budget stakeholder engagement process.

The Department of Health supports the key learnings identified for consideration by all entities.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit that may be considered by other Australian Government entities.

Policy design

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australia’s national system for delivering healthcare involves all levels of government, and the private and not-for-profit sectors. The Department of Health is responsible for implementing the Australian Government’s health priorities. It administers health-related programs and services, including Medicare, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, aged care and national mental health programs. It also manages a range of partnerships with the states and territories to support the public hospital system and the delivery of services to Indigenous communities. The department manages funding of around $5.3 billion for more than 10,000 grants delivered by over 4100 organisations.

1.2 In 2017–18, the Government budgeted $75.3 billion on health2, representing 16.2 per cent of all proposed government expenditure.3 Increases in government overall spending in recent years have been driven, in part, by substantial health care commitments. Health expenditure is projected to be a major source of longer-term pressure on federal and state budgets. Federal expenditure has averaged around 3.6 per cent per year since 2015–16, and is expected to grow in real terms from 2017–18 to 2020–21 reflecting higher demand for services. Demand is driven by factors such as the increasing prevalence of chronic disease, changing demographics, and the availability of new, but costly technologies.4

1.3 Over 80 per cent of Health’s administered funding is tied to special appropriations dedicated to Medicare, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and payments to the states and territories to support the operation of hospitals.5 Changes in legislation may be necessary to support savings in these areas of expenditure. The Government’s proposed 2014–15 Health Portfolio Budget savings measure – Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme – Increase in co-payments and safety net thresholds, intended to save $1.2 billion over the forward estimates, is an example of a measure requiring legislative amendment that was not passed by the Parliament and consequently could not implemented by the Government. In contrast, the Government’s 2017–18 measure to improve access to medicines that proposes to make $1.3 billion in savings over the forward estimates is not subject to the passage of legislation.

The incoming Government’s priorities for health expenditure

1.4 In 2013 the then Opposition made an election commitment to reduce the cost of health administration.6 Following the election, the Australian Government established processes to examine the appropriate role and scope of government activity as part of its Smaller Government Reform agenda.7 As part of these reforms, the Government established the National Commission of Audit to review and report on the performance, functions and roles of the Commonwealth Government. The federal health portfolio was a key area of government expenditure and service delivery considered by the Commission which noted the funding of health was ‘the Commonwealth’s single largest long-term fiscal challenge.’8

1.5 The Government also introduced the Efficiency through Contestability Programme implemented by Finance which included a series of ‘portfolio stocktakes’ undertaken across a number of entities.9 A review of the health portfolio — the Functional and Efficiency Review (FER) — conducted between January and March 2015, made 90 recommendations for clarifying the roles and responsibilities of the department and increasing the efficiency of its operations. The review formed the basis of significant savings announced in the 2015–16 Budget of close to $100 million over the forward estimates. The ANAO’s performance audit of the Efficiency through Contestability Programme examined the implementation of FER measures by portfolios and found that Health and other entities did not have processes in place to measure, monitor and report efficiency and performance improvements arising from the recommendations.10

The Department of Health’s savings measures

1.6 The $1.2 billion in savings measures selected for the audit represent key savings the Government applied to the health portfolio in 2014–15 and 2015–16.11 These savings contributed to funding new health priorities, including the establishment of the $20 billion Medical Research Future Fund. The measures encompass:

- election commitments to reduce duplication and waste in spending by abolishing two small agencies established under the previous government;

- administered program measures where funds were to be returned to Budget or reallocated to other health policy or program priorities; and

- departmental measures which were to increase the efficiency of government activity and contribute to the Government’s Smaller Government agenda.

1.7 The budget measures are set out in Box 1 below. The components of these measures are shown at Appendix 2.

|

Budget measures |

|

Budget 2014–15

Budget 2015–16

|

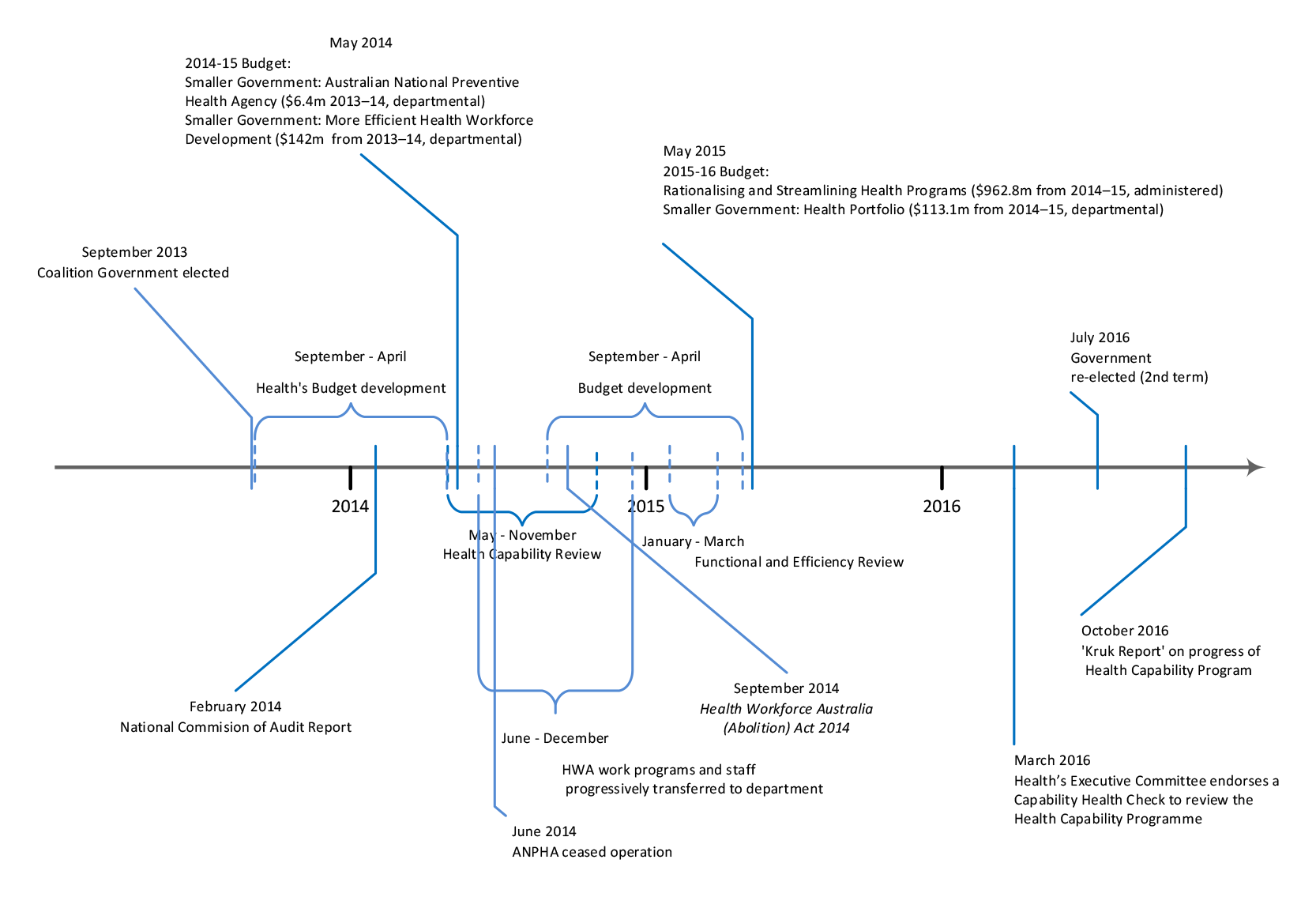

1.8 A timeline of key events in the development and implementation of the measures is at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Key events in the development and implementation of the health savings measures

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.9 Health’s management of savings measures was selected for audit because of the scale of health expenditure, and the importance of sound financial management for the Australian Government’s overall fiscal position. Sound decision-making and the effective implementation of health savings supports the ability of the Government to maintain service provision into the future. Health has not reported on the impact of the savings measures on its delivery of programs through its annual reports or other means. The audit therefore provides information to Parliament about the status of the Budget measures and has the potential to inform the management and reporting of savings measures by other entities.

Audit objective and criteria

1.10 The objective of the audit is to assess the Department of Health’s design, implementation and monitoring of select 2014–15 and 2015–16 Budget measures aimed at achieving $1.2 billion in savings and other benefits. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Were sound processes and practices established to support the design and implementation of specific measures?

- Is the achievement of savings and benefits being appropriately monitored?

- Is implementation of the measures on track?

1.11 The Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure encompassed savings to 14 funds and 14 program measures. Component savings varied from $1.2 million to $298.9 million. The audit has restricted its focus to the top 20 measures representing 87 per cent of the total value of the measure.

Audit methodology

1.12 The ANAO examined the Department of Health’s records relating to the development and implementation of the savings measures, including governance reviews, budget and committee papers, emails and briefings to the Minister. The ANAO also interviewed senior managers from the department, as well as the departments of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Finance.

1.13 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $365,900.

1.14 The team members for this audit were Judy Lachele, Jillian Blow, Meg Byrne, Dr Shay Simpson and Mark Rodrigues.

2. Design of the measures

Areas examined

This chapter examines the department’s design of health savings measures, including its provision of advice to the Government and planning for the implementation of measures.

Conclusion

Health used generally sound processes and practices to support the design and implementation of savings measures. The design of measures was consistent with guidance provided by the Department of Finance and the department’s internal budgeting processes. Advice to the Government to inform decision-making on the nature and extent of savings to health spending was relevant and timely.

Areas for improvement

There is scope for the department to strengthen its arrangements to support the evidence-based design of departmental savings measures and document its plans for the implementation of key measures, including the assessment of risks and mitigation approaches.

Was the design of measures soundly based?

Health developed administered savings options in line with guidance provided by Finance. It designed measures, in the first instance, by drawing on uncommitted funding, consistent with its internal budgeting processes. In identifying further opportunities for savings, the department was responsive to the Government’s priorities and developed proposals based on policy considerations and program evidence. In designing departmental savings measures Health did not develop costings for all efficiency measures. There is merit in Health strengthening its approach to quantifying potential savings and establishing baselines for measuring their impact on efficiency during implementation.

Administered savings

2.1 Administered savings under the 2015–16 Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs savings measure were developed by Health during the Budget development process. Savings of $962.8 million over four years were identified, made up of $366.6 million in targeted measures and $596.2 million through a reduction to a number of funding streams known collectively as Health Portfolio Flexible Funds (‘the Flexible Funds’).12

2.2 The department developed advice in line with guidance issued by Finance aimed at informing the Government’s consideration of options for ceasing or reducing expenditure. The department also gave appropriate consideration to policy criteria in its preparation of savings proposals, showing responsiveness to Government priorities; use of evidence; awareness of likely stakeholder reactions, risks and implementation issues. The agreed scheduling of savings over the four years gave the department scope to undertake further consultation and analysis, and to develop fully costed proposals.

2.3 Health considered options for making savings, including: returning unspent program funds; budget variations to reflect election commitments and/or changes in government priorities; adjustments to criteria used to determine whether individuals or organisations would be eligible to receive funding for programs; and changes to the delivery of programs. The proposed savings appropriately took into consideration policy priority, viability of implementation, and the level of saving that could be achieved.

Departmental savings

2.4 Health’s design of measures to increase the efficiency of its operations drew on the recommendations of a Functional and Efficiency Review (FER or the Review) conducted in 2015. The Review formed part of the Efficiency through Contestability Programme introduced by the Government in 2014–15 and implemented by the Department of Finance. A consultancy was commissioned to conduct the review in consultation with Health.13

2.5 The Review examined the appropriateness of the department’s functions, including whether functions should be performed by the department or delivered through other mechanisms and performance improvements that could be made to functions retained within the portfolio. The FER report made 90 recommendations, encompassing a broad range of departmental functions, to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the department’s operations.

2.6 The department’s proposal, Smaller Government: Health Portfolio, was accepted by government and included the implementation of 12 FER recommendations which had scope to reduce departmental costs. Some of the efficiency measures aimed to reduce costs and deliver better outcomes (for example, the restructuring of divisions within the department to reduce staffing and to improve policy development processes). Other proposed changes involved maintaining existing service levels with reduced resources (for example, the replacement of IT contractors with permanent staff). Savings were also to be delivered through achieving economies of scale and adjusting performance expectations (for example, the extension of online corporate services).

2.7 Table 2.1 sets out savings and outcomes that were to be delivered through organisational changes under the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio measure.

Table 2.1: Efficiency savings measures and intended outcomes

|

Action |

Basis for savings |

Intended outcome |

|

Operational efficiencies through better organisational alignment ($32 million) |

||

|

Merge Primary and Mental Care and Acute Care Divisions into a single division ($2 million) |

Savings to be achieved through reduction in staff and resourcing |

A more integrated approach to primary health care |

|

Abolish Best Practice Regulation and Deregulation Division and transfer functions to relevant areas of the department ($2 million) |

Savings to be achieved through reduction in staff and resourcing |

Ensure that new health policies do not create unnecessary regulation; and that existing regulation is optimised to minimise the regulatory burden |

|

Establish memoranda with specialist portfolio agencies to provide expertise to the department Reduce Commonwealth resources dedicated to monitoring public hospital performance Transfer hospital declaration process to the Medical Benefits Division Align chronic disease programs with the functions of the Primary and Mental Health Care and Population Health divisions Audit and rationalise registries ($28 million) |

Savings to be achieved through: discontinuation of functions; reduction in staff and resourcing; and outsourcing of functions (components of savings not individually costed) |

Better use of existing information sources and more efficient delivery of functions |

|

Operational efficiencies through corporate service delivery ($38.3 million) |

||

|

Amalgamate the corporate and legal services of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) into the mainstream service areas of the department ($16.2 million) |

Savings to be achieved through cost reductions in the provision of corporate and legal services; and reduction in staff and resourcing |

Improved economies of scale and efficiencies through the extension of the department’s corporate and legal services to TGA |

|

Remodel the provision of business and financial advice and support to divisions (‘embedded model’) ($22.1 million) |

Savings to be achieved through: standardisation of service provision; and reduction in staff and resourcing |

Improved accountability, capability and consistency in the business and financial management functions of corporate divisions |

|

IT insourcing ($22.1 million) |

||

|

Seek an exemption to the Australian Public Service recruitment freeze and replace IT contract staff with permanent employees |

Savings to be achieved through reduced contractor costs in the provision of IT services |

Greater value for money in the provision of IT services |

|

Leases and tenancies ($9.4 million) |

||

|

Cease nominated property leases (Bowes Place and Pharmacy Guild House) and consolidate tenancies into the Woden precinct |

Savings to be achieved through discontinuation of leases |

A consolidated property footprint with greater levels of utilisation |

Source: ANAO analysis of the department’s information.

The evidence-base for FER savings

2.8 As part of the budget development process, Health reached agreement with Finance on the overall level of savings to be proposed and the costing of individual FER measures. In the limited time in which the Review had been undertaken, neither the consultancy nor the department fully examined the proposed departmental savings measures to determine the full costs or benefits of changes to business process or of ceasing functions. Health adopted the FER’s recommendations for proposed savings measures unchanged, accepting the Review’s estimate of the savings.

2.9 The department advised the Minister that it wanted to retain flexibility in implementing the measures. The efficiency measures and associated costings were subsequently agreed by the Government. Health also advised the Minister that further analysis would be required to verify the costing information provided by the FER consultants. This further analysis was not undertaken. Without individually costing all measures, Health was unable to determine the contribution each initiative was to make to the overall savings estimate.

2.10 It is important that the department is able to assure itself that the costing of proposed efficiencies is robust and can be used as a baseline to support its monitoring of implementation, including the realisation of benefits. Finance guidance also requires policy proposals to outline how the delivery of the proposed outcome will be measured, for example, through departmental evaluation, key performance indicators, benchmarking or external review. This information was not provided in its briefing to the Government.

Abolition of entities

2.11 The closure of Health Workforce Australia (HWA) and the Australian National Preventive Health Agency (ANPHA) had been foreshadowed in 2013 in the election commitments of the then Opposition.

Health Workforce Australia

2.12 HWA had been established as a result of a $1.6 billion Council of Australian Governments (COAG) health workforce reform package in 2008. Key HWA programs related to clinical training, workforce modelling and the development of a national workforce planning statistical database. HWA was abolished in the 2014–15 Budget as part of a $142 million health workforce savings package — Smaller Government: More Efficient Health Workforce Development. The Budget measure covered the closure of the agency and the consolidation of its functions into Health ($88 million in savings), and other health workforce-related measures administered by the department.

2.13 The decision to abolish HWA was underpinned by two reviews. The 2013 Review of Australian Government Health Workforce Programs (the Mason Review) reported stakeholder concern about duplication and inconsistencies between HWA delivered programs and those managed by the department.14 In 2014 the National Commission of Audit recommended integrating HWA with the department as part of a broader agenda of rationalising government bodies.15

2.14 Within the first weeks of the Government’s term the department provided the Minister with advice on options for transferring key HWA programs to the department. As part of the 2014–15 Portfolio Budget Submission, the department put forward a proposal for abolishing the agency, citing the lack of state funding under the expired COAG National Partnership Agreement; the lack of Commonwealth control over the funds it had contributed; and duplication between HWA and departmental programs.

Australian National Preventive Health Agency

2.15 Established in January 2011, ANPHA undertook preventive health research activities and policy in the areas of alcohol, tobacco and obesity. The Government’s objective in abolishing the entity was to achieve savings by eliminating the duplication of administrative, policy and program functions between ANPHA and the department.16 Abolition of ANPHA was also intended to restore the Commonwealth’s capacity to direct or reprioritise funds allocated to ANPHA’s preventive health activities. While funding for the Agency’s activities had been agreed with the states and territories through the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health, only the Commonwealth had provided its share – majority funding of $202 million over five years.

2.16 ANPHA had received departmental and administered funds, and also had an administered Special Account primarily used to pay the Chief Executive Officer’s salary. The $6.4 million saving generated by the measure was based on the departmental appropriation for the agency over the forward years. The Government committed to maintaining ANPHA’s key functions.17

Was appropriate advice provided to government?

Advice provided to government on administered savings was appropriate, regular, and reflected the Government’s policy and fiscal objectives. Health informed the Minister of its response to Functional and Efficiency Review (FER) recommendations and proposed a range of departmental efficiency measures. The department did not provide further briefing to the Minister on matters arising from the FER, including in relation to further work and consultation that it had committed to undertake. Health’s advice to the Government to support the abolition of the Australian National Preventive Health Agency (ANPHA) and Health Workforce Australia (HWA) was relevant and timely and included options for managing risks.

Administered savings

Flexible Funds

2.17 The bulk of administered savings made in 2015–16 arose from a seven per cent reduction in expenditure on grants administered through Health’s Flexible Funds. In 2015–16 the Flexible Funds supported 10,500 individual grants delivered by more than 4100 organisations, with a total commitment of around $19.3 billion over the forward estimates. Grants were issued for:

- services—payments to organisations to deliver services, for example, 24/7 call centre support (such as Nurse Telephone Triage, After Hours GP Helpline and the Pregnancy, Birth and Baby Helpline);

- payments to individuals—for example, health workforce scholarships;

- research activities/data gathering—for example, primary health care;

- capital—for example, infrastructure projects for Commonwealth funded organisations; and

- discretionary grants—targeted services, such as education and prevention activities and funding to peak bodies.

2.18 In 2016 grant funding made up around 62 per cent of the total funding available through the Flexible Funds. There was also a number of programs within the funds which did not involve grant agreements, such as the Practice Nurse Incentive Program, the Practice Incentive Program for General Practice Fund, the Indemnity Insurance Fund and the Health Social Surveys Fund.

2.19 The Flexible Funds had been identified as a source of savings over a number of Budget cycles. In the 2014–15 Budget, savings of $197 million over three years were made through a pause in indexation and by reducing uncommitted funds. The 2015–16 Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure overlaid the budget savings measure of the previous year with an additional seven per cent reduction in funding over the forward estimates across 14 of the 16 funding categories.18 Overall, the advice provided by the department was sound and consistent with guidance provided by Finance.

2.20 The implementation of the Flexible Funds decision is examined in Chapter 4.

Departmental savings

2.21 The Government endorsed the department’s selection of efficiency measures by agreeing to the proposal, Smaller Government: Health Portfolio, as part of the 2015–16 Budget which outlined $106 million of departmental savings based on FER recommendations.19

2.22 As Health regarded efficiency measures proposed by the Review to be operational matters for the department’s Executive to consider and implement, it did not seek the Minister’s formal approval of its response to the Review. While the department noted the broad scope of the FER would provide a basis for further analysis and work, it did not prepare additional advice for the Government. Without robust costings linked with performance information, the department was not well positioned to inform itself of the potential impact of the measures on the delivery of policies and programs.

Abolition of entities

2.23 The department provided timely and appropriate advice to the Minister on the process for closing ANPHA and integrating key functions into the department. This advice canvassed a range of options for managing the closure of the agency. Subsequent to the decision to abolish the Agency, the department proposed options to the Minister for notifying state and territory governments. Advice was also provided to the Minister on negotiating terms for the resignation of the CEO.

2.24 The department briefed the Minister on legislative issues affecting both entities, including risks associated with timing. On the basis of internal legal advice, the department developed contingency arrangements to manage the possibility that repeal legislation would not be passed during the parliamentary 2014 Winter sittings. This would have left HWA in a situation without a CEO (whose term was due to expire in August 2014) and with an inquorate board, and therefore without officers authorised to carry out its activities.

2.25 As the HWA abolition bill did not proceed through Parliament during the Winter sittings, the department addressed risks by establishing a management agreement with HWA to cover the period between the expiry of the acting CEO’s term and the passage of legislation. This gave the department authority to manage HWA’s resources and continue closure activities prior to the passage of the legislation.

Were effective plans established to support implementation of the measures?

The department’s planning for the implementation of administered savings was generally appropriate, except for the lack of a coordinated strategy for engaging external stakeholders. The department has undertaken work since 2015–16 to improve its Budget stakeholder engagement processes. While departmental measures were incorporated into portfolio-wide plans for organisational change, Health did not undertake sufficient project planning for the measures in relation to implementation risks and mitigation strategies. The department developed timely, fit-for-purpose plans to support the abolition of ANPHA and HWA.

Administered savings

2.26 Planning for the implementation of individual administered measures arising from the Budget process was undertaken by the responsible divisions within Health. The scope for the department to undertake extensive planning for the implementation of Flexible Funds savings was limited, as the specific impacts on program activity and individual grant recipients had not been determined as part of the Budget process.

2.27 At the time the Budget was handed down in May 2015, the department did not have a strategy in place to respond to potential stakeholder concerns or queries about the savings component of the Budget. The department’s planning could have anticipated this as an important factor in effective implementation. A coordinated portfolio-wide communications strategy, deployed at the time of the Budget announcement, would have better positioned the department to communicate Budget measures and its intended approach to engaging with stakeholders in implementing the Flexible Funds decision.

2.28 At June 2015 Health had yet to develop options for the Minister on applying the savings to each affected Fund, or to contact organisations with contracts ending at the end of 2015 about their future funding arrangements.20 Organisations with grants due to expire by the end of December 2015 were not contacted until October or later. Organisations with grants expiring June 2016 were not able to obtain information through the department’s general hotline until February 2016.

2.29 Soon after the 2015–16 Budget the department reviewed its handling of the budget process. The review found that there was a need to manage key stages more proactively and strategically, including by supporting the Government in explaining the Budget and engaging stakeholders.21 The department’s newly formed Strategic Policy Committee, chaired at Deputy Secretary-level, assumed responsibility for advising on planning for Budget consultations with stakeholders. It commissioned a Budget Stakeholder Engagement Plan to identify opportunities and mechanisms for engaging with external stakeholders. The plan was used in subsequent budget processes.

Adjustments to programs

2.30 Once the Government had determined the proportion of savings to be applied to the Flexible Funds, the department advised the Minister of the principles it would apply in reducing grant allocations. These principles reflected the Government’s interests in maintaining service delivery and research functions and reducing duplication and minimising funding where the states and territories were considered to have primary responsibility.

2.31 The department’s planning to support implementation of the Flexible Funds savings was iterative, driven by progressive expiry of funding agreements over the forward estimates from 2015–16. The department advised the Minister that the practical means by which savings would be handled included redesigning programs and/or limiting the funding pool available to applicants.

Alignment of grant funding with priorities

2.32 The FER noted that the Flexible Funds had not delivered anticipated efficiencies, and were in practice relatively inflexible. Funds were often ‘locked up’ in smaller administrative funds, with only around ten per cent of each fund uncommitted. Funding could not be readily shifted across funding streams to align with broader and changing policy priorities.

2.33 The department informed the ANAO that the budget savings decisions over the forward estimates are now linked with portfolio priorities or outcomes. This would better position the department to review its activities on a flexible and continual basis to ensure proposals and savings options reflect the Government’s high-level priorities.

2.34 It will be important for the department to continue to develop its governance of the portfolio’s significant administered funding to help ensure that expenditure and savings options identified as part of the annual Budget process appropriately reflect the Government’s strategic policy interests.

Departmental

Adjustments to internal budgets

2.35 The department’s early planning for the implementation of departmental measures sought to balance the impacts of individual measures on particular divisions through a pro rata approach that distributed a proportion of savings across all divisions.

2.36 This approach to planning the allocation of savings was appropriate in that the:

- total savings to be achieved reflected the reduction in the department’s appropriation;

- cumulative financial impacts of the FER and other efficiency measures on the department’s appropriation were known and taken into account; and

- the financial impact of each efficiency initiative on each division and across divisions could be estimated and taken into account.

High-level and project-level planning

2.37 In May 2015 Health engaged a consultancy22 to develop an integrated high-level program and plans for all recommendations and initiatives arising from the Health Capability Program (HCP), FER and other reviews.23 The consultancy mapped reform activities underway within Health. However, more detailed project planning work, such as the development of ‘business improvement plans’, as specified by the contract, was not completed.

2.38 The HCP framework had five main themes: leadership and culture; strategy; governance and delivery frameworks; and risk and stakeholder engagement. Each theme had a number of broad objectives to be met through the implementation of specific ‘work packages.’ The ANAO’s analysis identified that the 12 FER savings measures were integrated into the HCP to align with 11 of its 56 distinct work packages or projects.

2.39 Health informed the ANAO that because it merged its response to the FER recommendations with multiple reviews at the time, it could not identify project-level plans or risk assessments specific to individual FER recommendations. However, a number of FER recommendations remained distinct initiatives throughout the department’s change process. Examples are the introduction of a new model for the delivery of corporate support to divisions and the extension of shared corporate services to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Risk assessments for these longer-term, more complex and higher-value initiatives would have better positioned the department to take timely and corrective action, if necessary, to support the effective implementation of efficiencies.

Abolition of entities

2.40 To support the abolition of ANPHA and HWA, the department set up senior level oversight committees and working-level groups to manage the transition of essential functions to the department. Working groups developed action plans covering an appropriate range of matters, including:

- commissioning due diligence reviews to ascertain the financial position and liabilities of the agencies;

- transferring appropriations and liabilities to the department;

- disposing of assets, terminate leases and utilities;

- communicating with staff and stakeholders;

- transitioning staff; and

- transferring functions and programs to the department.

2.41 The withdrawal of funding for HWA and ANPHA required the abolition of these agencies to occur by the end of the financial year, or soon thereafter. This was achieved in both cases.

3. Monitoring of savings and benefits

Areas examined

This chapter examines the department’s monitoring of savings measures and benefits.

Conclusion

The achievement of savings and benefits has not been sufficiently monitored. The department did not have robust information management systems in place to enable it to produce accurate reports on the status of grants from administered funds. Since the 2015–16 Budget the department has improved its governance arrangements for the management of administered appropriations and strengthened its systems for tracking grant expenditure. Health’s monitoring of departmental savings measures focused on high-level information about implementation activities and did not include information about reductions in operating costs or the achievement of specific benefits.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the department implement appropriate performance measures to support its monitoring of efficiency measures. It is also suggested that in reporting the progress of individual measures, the department ensure a clear line of sight is maintained between measures, as they evolve, and original commitments made to government to assist in tracking the achievement of objectives over time.

Did the department use appropriate oversight arrangements to monitor the implementation of measures?

Health used appropriate oversight arrangements to monitor the implementation of administered and departmental measures.

3.1 Once a portfolio’s appropriation has been reduced, savings are to be reflected in changes to internal budget allocations. Adjustments to the department’s operations, including its management of policy and program functions, then give substance to the Government’s direction. Appropriate oversight arrangements are needed to ensure that progress in implementation and the realisation of benefits can be tracked.

Administered

Oversight arrangements

3.2 Health established an Administered Grants Program Board in December 2015 chaired by the Chief Operating Officer and involving the heads of all divisions. It met on a regular basis to discuss the status and trend of spending across the department. The role of the Board includes providing options to the Minister, via a senior officer, to reprioritise existing funding decisions and advise on future proposals. The Board’s primary focus is tracking administered spending across the portfolio. The department has also recently established a Program Assurance Committee to strengthen oversight of program delivery from both a financial and non-financial perspective. The department has informed the ANAO that the Committee will receive performance reporting aimed at enabling the department to better assess the outcomes of program implementation.

Information management

3.3 The main system used by the department to manage its grant activities is FOFMS.24 This system contains grants information, including grant recipient details, legal commitments for current and forward years and actual expenses. In 2015–16, the department also used several other data systems to manage grant information. The multiplicity of data sources was accompanied by inconsistencies in business processes for recording data and the level of detail captured.

3.4 Health extracted data from FOFMs and other systems to generate reports for the Executive, the Minister and other stakeholders. The department used Excel spreadsheets to combine and manipulate data for reporting purposes. It was unable to use these systems to accurately correlate grant data with the aggregated program data that it had used to inform itself about the management of grants.

3.5 The department’s lack of ‘a single source of truth’ about the grants it managed hindered its ability to produce point-in-time reports on grant funding and forward commitments. The department informed the ANAO that the production of reports was a complicated and time-consuming process often taking days to prepare. Reports were also incomplete because they did not capture spending that had been approved by the Minister, but not recorded as committed in the department’s systems. The Executive became aware of the department’s significant data integrity and processing problems in June 2015 as it planned the implementation of the Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure.

3.6 Toward the end of 2015 the department initiated a financial management project to address the department’s poor data integrity, inconsistent and duplicative reporting processes, and unclear accountability for the management of data. The department informed the ANAO that this project is substantially implemented, but has not been used to support the development of the portfolio’s annual Budget.

Departmental

3.7 Following the Government’s announcement of the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio measure, the department established oversight arrangements to monitor the implementation of departmental measures. High-level planning was undertaken to establish a framework for reporting on the implementation of efficiency measures.

3.8 In September 2015 the Executive Committee agreed to a framework for reporting on the progress of implementation of the integrated Health Capability Program (HCP) using the themes identified by the Health Capability Review: Leadership and Culture; Strategy; Governance and Delivery Frameworks; Risks; and Stakeholder Engagement.

3.9 The Executive Committee received updates on implementation primarily through quarterly traffic light reports and periodic reviews. Reports outlined areas of focus and activities being undertaken. The progress of initiatives was predominantly rated green. However, the high-level reviews of progress described in Table 3.1 did not enable detailed tracking of financial and non-financial benefits being delivered through initiatives. The implementation of initiatives to give effect to the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio measure is examined further in Chapter 4.

Table 3.1: Reviews of Health’s implementation of its change program

|

Date |

Review |

|

December 2014 |

Initial Health Capability Program (HCP) Action Plan |

|

May 2015 |

Integrated plan developed by consultancy (Third Horizon) incorporating Functional and Efficiency Review recommendations |

|

September 2015 |

Integrated plan agreed to by the department’s Executive Committee |

|

July 2016 |

Independent Health Check (‘Kruk Report’) which reviewed the implementation of the HCP, but did not specifically report on FER measures |

|

December 2016 |

Health Capability Program Stocktake |

|

February 2017 |

Executive Committee Paper – Closure of Health Capability Program and transition to Wave 2 Program1 |

|

November 2017 |

Executive Committee Paper – Closure of Wave 2 Program with central monitoring of initiatives discontinued |

Note 1: The department used the term ‘Wave 2’ to describe a revised program of reform activities following the closing off of the Health Capability Program Action Plan.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

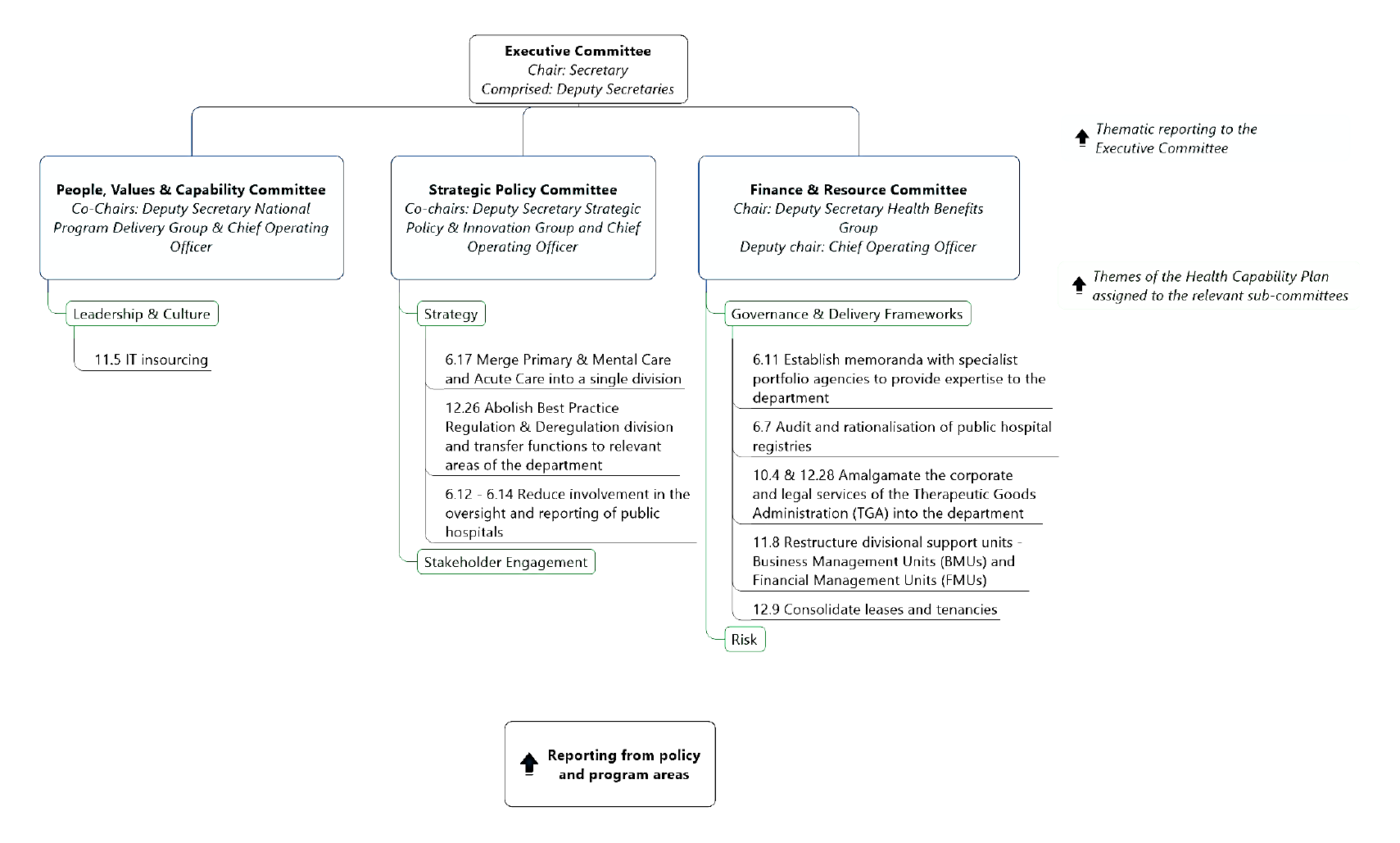

3.10 Responsibility for driving the implementation of organisational reform initiatives, including FER measures, was assigned to senior committees reporting to the Executive Committee (Figure 3.1). The three committees of the department—Strategic Policy; Finance and Resource; and People, Values and Capability—focused on initiatives linked to the five HCP themes25 with policy and program areas reporting, as needed, to the sub–committees. A business lead was identified for each work package or project in the plan. The committees reported to the Executive Committee on a quarterly basis, with the sub-committees meeting monthly to discuss strategic and specific organisational reform matters.26

Figure 3.1: Governance structure and oversight of departmental savings measures

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

3.11 The Executive Committee reviewed three quarterly performance reports of the HCP from the time FER recommendations were integrated with the HCP (September 2015) to its review of the Program and the transition of initiatives to business-as-usual or a new change program (October 2016).27 Executive Committee minutes indicate that it had actively considered performance reports and set directions in relation to specific matters arising from the management of the HCP.

Were appropriate performance measures established to support monitoring of departmental measures?

The oversight arrangements for departmental savings were undermined by a lack of appropriate measures to monitor the progress of implementation and its impact. The integration of efficiency measures into the department’s broader change program (Health Capability Program) reduced visibility of the department’s progress in achieving the efficiency outcomes.

3.12 The department’s monitoring of the implementation of administered savings measures occurred through tracking divisional spending against revised internal funding allocations. This section examines the department’s governance arrangements for monitoring departmental efficiency initiatives across the portfolio.

3.13 There was some variability in how departmental reform initiatives were monitored over time. This was due to changes made to frameworks for reporting on measures following Executive Committee reviews and stock-takes of progress. Table 3.2 shows the various ways in which projects were grouped between 2015 and 2017. Without a clear line of sight from original planning to the completion of the initiatives, the department is not well placed to determine whether the initiatives have been implemented within expected timeframes and have met their objectives.

Table 3.2: Departmental savings measures through successive reporting frameworks

|

FER savings measures |

Integrated into HCP ‘work package’ September 2015 |

Retitled in HCP stocktake February 2017 |

Carried forward in HCP Wave 2 June 2017 |

|

Merge Primary and Mental Care and Acute Care into a single division |

Strategic Policy and Innovation Group (SPIG) restructure |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Abolish Best Practice Regulation and Deregulation Division and transfer functions to relevant areas of the department |

SPIG restructure |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Regulatory Services Group restructure |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

|

Establish memoranda with specialist portfolio agencies to provide expertise to the department |

Leverage Capability of Specialist portfolio agencies |

Leverage Capability of Specialist portfolio agencies |

Leverage Capability of Specialist portfolio agencies |

|

Reduce Commonwealth resources dedicated to monitoring public hospital performance |

SPIG restructure |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Transfer hospital declaration process to the Medical Benefits Division |

SPIG restructure |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Align chronic disease programs with the functions of the Primary and Mental Health Care and Population Health Divisions |

SPIG restructure |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Audit and rationalisation of registries |

Audit of the department’s registries |

Audit of department’s registries |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Amalgamate the corporate services of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) into the mainstream service areas of the department |

Integrate corporate services functions with Regulatory Services Group |

Organisational alignment |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Amalgamate the legal services of the TGA into the department |

Legal services operating model |

Transactional Corporate Services |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Restructure the operation of divisional support units with Business Management Units (BMUs) to adopt an ‘account manager’ model and Financial Management Units (FMUs) a ‘co-located’ model |

Review current BMU/FMU model Finance Business Partners People Business Partners |

Consolidate corporate service delivery in Chief Operating Officer (COO) group |

COO Operating Efficiency and Effectiveness |

|

Seek an exemption to the APS recruitment freeze and replace IT contract staff with permanent employees |

Targeted capability identification and mobilisation |

Targeted capability identification and mobilisation |

No. Assessed as completed. |

|

Cease nominated property leases (Bowes Place and Pharmacy Guild House) and consolidate tenancies into the Woden precinct |

Undertake a strategic property review and ‘block and stack’ |

Increase strategic value–add to the business |

COO Operating Efficiency and Effectiveness |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

3.14 Traffic light reporting on the implementation of efficiency measures to the Executive Committee included the consideration of broad strategic risks. As noted in Chapter 2, the department has not retained documentation to demonstrate that specific risk mitigation plans were developed or used. Risk assessments would have supported more meaningful monitoring of risks by the Executive Committee and allowed action to be taken to correct potential under-performance in the delivery of specific initiatives and the savings to which the department had committed.

3.15 Health’s Executive had previously considered the need for meaningful performance information. In planning for the development of its 2015–19 Corporate Plan the Executive Committee identified the need for suitable performance measures to allow reporting on the rationale and intended results of its portfolio activities. Briefing provided to the Executive Committee in March 2016 noted that ‘until recently, the department has focussed primarily on compliance driven delivery rather than with a strategic lens targeted at benefits realisation, strategic planning and prioritisation as a whole’. The briefing stated that work had commenced to develop clearly defined Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for all initiatives under the HCP ‘to shift current behaviour and focus on measuring the achievement of outcomes’. As at June 2017 the work on developing suitable KPIs was determined to be 30 per cent complete. As central monitoring of initiatives ceased in December 2017, it is unclear whether this work was completed.

3.16 In July 2016, a year after the commencement of the HCP, the department commissioned a review (‘Kruk Health Check’) of its implementation. The review observed that while the department collected a lot of data and information, this was not provided to the Executive Committee in a manner that would inform strategic decision-making. The review recommended that appropriate metrics be developed to enable the tracking of strategic priorities and the assessment of ‘organisational health’. It also noted that increasing the use of project and program evaluations and improved performance metrics would also improve delivery. The department has not retained documentation to demonstrate that the review’s recommendations have been implemented.

3.17 The Executive Committee did not monitor financial outcomes arising from the implementation of efficiency measures. In reporting on individual projects, the department did not refer back to the original policy costing assumptions or use these as a baseline for measuring actual savings realised. The absence of financial reporting on individual initiatives, or at an aggregate level, to the Executive Committee, undermined its ability to assure itself that functions were being carried out more efficiently and within the reduced funding parameters required by the measure.

3.18 Overspending and increased pressures on a department’s budget and/or declining performance may indicate efficiency is not increasing. Reporting by the Finance and Resources Committee to the Executive Committee in July 2017 noted that savings imposed by a number of efficiency reviews, including the FER, had contributed to increased financial pressures within the department. To assist it to manage budgetary pressures, Health should develop its ability to track the implementation of savings measures and the achievement of efficiency objectives within a performance measurement framework. Tracking the impact of efficiency measures would also better place the department to identify and build on learnings from successful examples of effective implementation.

Recommendation no.1

3.19 That the Department of Health apply fit-for-purpose performance criteria to assist it to monitor the implementation of savings measures and assess their impact.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

3.20 Health has introduced a consistent approach to implementation planning for all 2018–19 Budget measures, including capturing information on performance indicators, key implementation issues and risks. Oversight of the ongoing implementation of Budget measures will also be undertaken by relevant Senior Governance Committees.

4. Implementation and outcomes

Areas examined

This chapter examines the implementation of activities to give effect to the savings measures.

Conclusion

The department made appropriate adjustments to internal administered and departmental budget allocations to reflect the Government’s decision-making. The department did not establish arrangements to inform itself of the extent to which the intended benefits of efficiency measures had been realised.

Were savings measures effectively delivered?

Health made internal financial adjustments to give effect to the Government’s savings decisions. The department did not fully implement all of the efficiency measures included in the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio budget measure. In line with the Government’s decision to reduce duplication, ANPHA and HWA were abolished by the end of 2014–15 and functions were transferred to the department. However, the department has generally not retained documentation on performance outcomes.

4.1 The effective implementation of measures involves adjusting financial allocations and taking the necessary steps to give substance to the Government’s direction.

Administered

4.2 The total saving to the Flexible Funds required by the Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure was seven per cent over the forward estimates. Health informed the Parliament that a ‘notional’ cumulative savings of 2.8 per cent per year had been applied to 14 of the 16 Flexible Funds for four years commencing July 2015.28 Savings were applied to each Fund to contribute to the total savings amount required, however, specific activities were not identified for termination. The approach provided the Minister with flexibility in applying the savings across the funds and over the forward estimates.

4.3 Following the Budget announcement, the savings to each Fund were not applied proportionally across the funds. Almost half of the savings generated by the Flexible Funds component of the Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure ($596.2 million) came from a $289 million saving applied to one of the Funds, (the Health Workforce Flexible Fund, HWF), representing a saving of approximately seven per cent to that Fund.29 The savings were applied in progressively larger increments to the Fund with most of the impact to be absorbed in later years.

Managing the impact of savings

4.4 The level of savings applied to the Flexible Funds was anticipated to be greatest in 2017–18 due to the Government’s earlier Budget decision in 2014–15 to reduce the Flexible Funds by pausing indexation (as discussed in Chapter 2). This three per cent saving over three years would come into effect at the same time as the Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure.30 The total amount of savings to the Flexible Funds as announced in the two successive Budget years was $793.3 million.

4.5 The department’s proposed approach to implementing the two savings measures was, in part, aimed at minimising disruption to the provision of health services. The Government, on advice from the department, set a low savings target for the first year of implementation ($57.8 million) to mitigate the impact of the measures on organisations with terminating funding agreements. Larger financial impacts were deferred to later years ($240.2 million in 2018–19). The expiry of grants over the forward estimates required the progressive application of savings from 2015–16, with decisions about which sub-programs or organisations would be subject to reductions in funding still to be made.

4.6 In relation to the Health Workforce Fund31, the department sought to develop options that would not affect frontline service delivery, but noted in advice to the Minister this would be difficult to achieve given the large scale of savings envisaged by the measure. In March 2017, almost two years after the measure was announced, the department sought the Minister’s agreement to options for managing reductions in HWF funding. These included reducing the number of scholarships and Commonwealth-supported places offered by intern and training programs and ceasing rural dental incentives programs.

Managing the expiry of grants

4.7 The department was not able to accurately determine how many Flexible Funds grants were due to expire by 31 December 2015 and 30 June 2016. Internal departmental advice prepared in October 2015 noted that in 2015–16 there were 2185 organisations in receipt of 3665 grants funded through the Flexible Funds. Of these, 17 per cent (632) were due to expire in 2015–16, with just under half of these (286) due to expire on or before 31 December 2015 (45 per cent). Advice from 9 February 2016, however, indicated just over 650 of the department’s expiring grants in 2015–16 related to Flexible Funds.32

4.8 As at October 2015, five months after the Budget decision, the department had yet to commence funding agreement negotiations for grants due to expire 31 December 2015 and 30 June 2016. Progress in implementing the savings measure depended on the outcome of the department’s approaches to market and decisions made progressively by the Minister.

4.9 The Government honoured existing contracts, and net savings were achieved by ending some time-limited projects, and applying a pause in indexation to new funding provided to organisations. Health has not retained documentation indicating whether the time needed to negotiate or extend funding agreements impacted on the capacity of organisations to maintain continuity in service provision.

4.10 Other savings effected through targeted measures identified through the budget development process were implemented by the responsible policy and program areas through changes to, or the cessation of, activities. Examples of changes to program activity were:

- GP Super Clinics: A budget saving $16.8 million over three years achieved by not progressing three GP Super Clinic projects which had not yet commenced construction. An amount of $0.3 million was allocated in 2014–15 to finalise the termination of the related funding agreements. The remaining 61 of the planned 64 clinics under the GP Super Clinics Program continued in line with their funding agreements. ANAO’s analysis indicates that the cost and time needed to complete the terminations were greater than expected due to extensive legal negotiations with affected parties.

- EHealth Pathology Reform: Ceasing the additional funding that supported the inclusion of pathology results in the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record in the Pathology Funding Agreement established April 2011. The measure delivered savings of $161 million over five years through the removal of funding that had been provided previously through two separate eHealth measures. Future funding for some of the remaining pathology eHealth initiatives were to be supported through alternative pathology programs.33

- Inborn Error of Metabolism Program: Ceasing the program from January 2016, resulting in a potential budget saving of $11.7 million over four years. Subsidies under this program were to cease for people with protein metabolic disorders qualified under the program. It was noted in the savings proposal that cessation of the program could draw criticism from participants and peak bodies, which later eventuated. Following representations to the Minister and a media campaign, the proposal developed by the department was found to lack a strong evidence-base. The Government reversed the decision in the following Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook Budget update, before its planned commencement date.

- Limited tender process for one piece stoma pouches: A planned budget saving of $19 million over four years to the Stoma Appliance Scheme through an approach to market to ensure products listed under the scheme represented best value for money. The results from the tender process did not, however, deliver the value for money savings sought by the Government nor were comparable products found for all users. The saving was therefore not realised.

- Voluntary Dental Graduate Year Program and the Oral Health Therapist Graduate Year Program: Cessation of the programs at the completion of the 2015 cohorts, saving $56.7 million over four years (under the Consolidate and Streamline Dental Workforce Programs savings measure).34 These programs focused on new graduate practice experience. The rationale for ceasing the programs was the relatively high cost per placement, with the majority of support directed to public sector dental services, primarily a state and territory responsibility. Almost half of placements were in metropolitan areas, whereas the aim of the program had been to attract new graduates to areas of need, such as regional and remote locations.

Departmental

4.11 The department informed the ANAO that Health Capability Program initiatives were implemented from July 2015 to October 2017, and that most of the efficiency initiatives included in the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio savings measure have been implemented. However, reporting to senior committees on specific FER initiatives is not clearly linked to original efficiency initiatives.

4.12 The ANAO reviewed whether projects have been implemented and the intended benefits of measures had been realised. Health’s records indicate that the majority of the FER related projects were implemented35, although the extent to which the department has achieved the intended efficiency outcomes cannot be substantiated.

Reporting to the Government on implementation

4.13 The department did not provided updates to the Minister on its progress in implementing the efficiency initiatives included in the Smaller Government: Health Portfolio measure and its impacts.

4.14 In March 2017, consistent with Department of Finance guidance, the department advised the Government of an expected operating loss for the 2016–17 financial year of $37.8 million (4.6 per cent of its departmental budget). Health cited reasons that were not directly related to departmental efficiency measures. In September 2017 Health advised the Minister that it had exceeded its expected operating loss for 2016–17 by $18 million bringing the total loss to $55.5 million (6.6 per cent of its departmental budget). The regular finance report to the Executive for July 2017 noted that the department had managed savings pressures associated with efficiency dividends and various reviews, including the FER. The report also emphasised the importance of the department operating within its resource allocation for the 2017–18 financial year.

4.15 The Executive Board of the department receives monthly reports on the department’s financial performance. To support accountability, it is important that the department is able to accurately track spending over the course of the financial year, including the drivers of costs, and to apprise the Minister of any potential impacts on the department’s performance.

Abolition of agencies

Health Workforce Australia

4.16 All former HWA functions and programs were transferred to the department by October 2014, as shown in Table 4.1. Planning for the transfer of HWA’s functions began in late 2013, with the department advising the Minister on options for transferring and amalgamating key programs, including retaining its workforce data modelling function.

4.17 After the Budget announcement the department regularly met with HWA staff to consider which key functions should continue within the department. HWA also provided ‘transition summaries’ and hand-overs for each of the functions. Summaries included work plans, objectives, final products, milestones, existing commitments and future work recommendations. The department also kept records during the management agreement period of all work completed on behalf of HWA.

Table 4.1: Transfer of Health Workforce Australia functions to Health

|

Key functions |

Description of work |

Status after abolition of HWA |

|

Clinical Training Subsidy |

Funding to complement existing funding provided by states and territories and Commonwealth Higher Education Contribution Scheme funding |

Continuation within the department, with funding agreements novated to the department (program ceased in January 2016). |

|

Clinical Training Supervision |

Funding for clinical supervision capacity |

Continuation within the department until the program ceased on 30 November 2014. |

|

Clinical Training Simulated Learning Environments |

Simulated learning environments with a focus on accessibility to rural and regional centres |

Continuation within the department. |

|

International Recruitment Program |

Consolidating jurisdictional international recruitment programs into a single program covering all professions. |

Amalgamation into the department with some elements ceasing. |

|

Workforce Redesign Funding |

Strategies and projects to improve efficiency and effectiveness of health workforce. |

Most projects were complete at the time of HWA’s closure. Remaining funding agreements were novated to the department. |

|

National workforce planning statistical database |

Workforce data to assist with effective planning of workforce requirements. |

Continuation within the department. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Health information.

ANPHA

4.18 The wind up of ANPHA was achieved by the end of the 2014–15 financial year, with 16.5 full time equivalent (FTE) staff transferred to the preventive health area of the department, and the remaining 9.5 FTE transferred to other positions. The CEO resigned in January 2015. The department informed the ANAO that the reduction in the number of staff dedicated to preventive health did not affect the delivery of the function, indicating that the Government’s objectives to streamline administrative arrangements were met.

4.19 The Australian National Preventive Health Agency (Abolition) Bill 2014 to formally abolish the agency was not passed by Parliament and has not been reintroduced. The practical consequence of this is that the $12.4 million remaining in the Special Account cannot be returned to Consolidated Revenue and used for other purposes.

Is the department able to demonstrate savings and benefits as a result of implementing the measures?

The savings measures contributed to the Government’s fiscal agenda by reducing funding for programs, activities and departmental functions. In the absence of reliable information the department is unable to assure itself of whether efficiencies have been achieved. The abolition of ANPHA and HWA reduced duplication in the delivery of health workforce and preventive health functions.

Administered measures

Savings

4.20 The department’s analysis of budget measures indicates that Health portfolio funding decisions between the 2013–14 MYEFO and the 2016–17 Budget aimed to deliver $10.6 billion in net savings. This figure, however, includes savings measures requiring legislative changes that were not passed by the Parliament.36 Unlegislated measures in the Health portfolio in 2016–17 totalled $2.9 billion over five years, around a quarter of total net savings the Government had planned to achieve. While appropriation is withdrawn at the time of the Budget decisions, Finance has advised that the budget year and forward estimates are adjusted in the Budget Estimates process each year to reflect the fact that enabling legislation has not been enacted. The unlegislated measures were reversed in the 2017–18 Budget, and the portfolio was not required to identify an alternative source of savings in that year.

Benefits

New priorities

4.21 The implementation of the Rationalising and Streamlining Health Programs measure reflects decisions taken by the Government on a large number of individual grants and programs. This has enabled lower spending priorities within the portfolio to be identified and the department’s level of underspend to be reduced.