Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Design and Conduct of the Third and Fourth Funding Rounds of the Regional Development Australia Fund

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and conduct of the third and fourth funding rounds of the Regional Development Australia Fund.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Regional Development Australia Fund (RDAF) was established in early 2011 as a nationally competitive, merit-based grants program with discrete funding rounds. RDAF was one of the initiatives established to deliver on the then Government’s September 2010 agreement with the Independent Members for Lyne and New England.

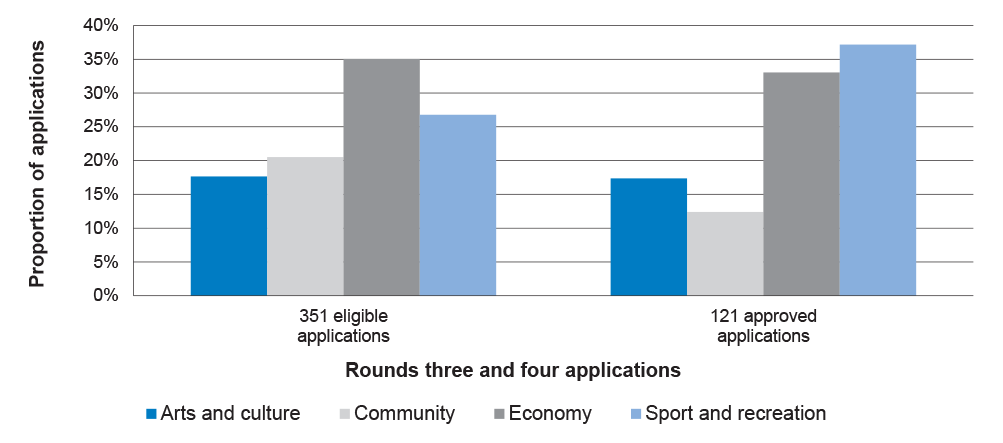

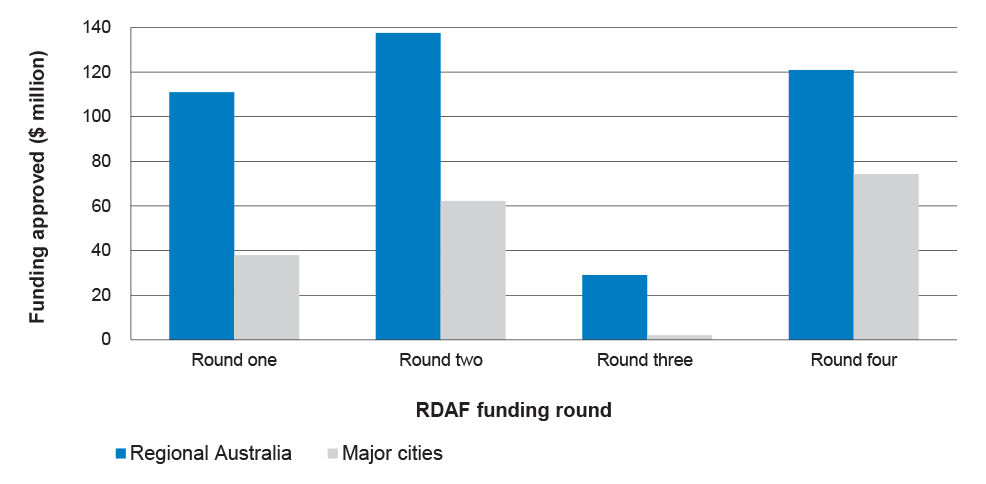

2. Four RDAF funding rounds were delivered between 2011 and 2013. Under the third and fourth rounds, which are the subject of this performance audit report, more than $226 million in grant funding was awarded to 121 capital infrastructure projects by the then Minister for Regional Services, Local Communities and Territories.1 Most of the funding was awarded to sport and recreation projects or projects that were expected to be of economic benefit to the area in which they were located. Nearly 70 per cent of the total funding approved over the four rounds was for projects located in regional Australia, with a number of the other approved projects that were located in major cities also expected to provide some benefits to regional Australia.

3. Administration of RDAF was initially allocated to the then Department of Regional Australia, Regional Development and Local Government, which became the Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport (DRALGAS) in December 2011.2 Since September 2013, following the change of government, RDAF has been administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD).3 In addition:

- the 55 Regional Development Australia (RDA) committees located across Australia played an important role in the expression of interest (EOI) process used to shortlist candidates for funding; and

- an advisory panel was responsible for assessing the individual and relative merits of eligible applications and recommending which applications should be approved. The panel members were selected for their experience, knowledge and expertise on regional Australia. The panel membership remained the same across each of the four competitive RDAF rounds.

4. The panel’s advice was provided to the then Minister by DRALGAS on 6 May 2013 for round three, and on 17 May 2013 for round four. Consistent with the program guidelines, the panel classified each eligible application into one of three categories:

- ‘Recommended for Funding’ (RFF). For round three, the panel categorised 95 applications as RFF and recommended to the Minister that those applications be awarded $38.3 million in grant funding. For round four, the panel categorised 34 projects as RFF and recommended to the Minister that those 34 projects be funded at a cost of up to $172.5 million. For each round, the panel provided the Minister with analysis of the geographical distribution of funding for recommended projects, as well as a list of the projects that were being recommended;

- ‘Suitable for Funding’ (SFF). The panel categorised as SFF:

- 20 round three applications. Those applications were seeking $7.6 million in funding, which could have been accommodated together with the 95 applications categorised as RFF within the $50 million funding announced as being available. However, the panel did not recommend that those 20 applications be awarded funding because they were, in the view of the panel, not of sufficient quality; and

- 19 round four applications that had sought $90.3 million in grant funding. Those applications could not have been accommodated within the $175 million in funding announced as available for round four and, in any event, the panel had concluded those applications were not of a high enough standard to be recommended for funding; and

- ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ (NRF). The panel included in this category 77 round three applications seeking $31.2 million in grant funding, and 106 round four applications seeking $628.0 million in grant funding.

5. In May 2013 the Minister approved 79 projects for round three funding of $31.1 million from the $50 million available for allocation under that round. As illustrated by Table S.1, the approved projects were drawn from each of the three categories. By late June 2013 the Minister had awarded $195.2 million to 42 round four projects, again drawn from across the three categories (see Table S.1).

Table S.1: Minister’s funding decisions in rounds three and four

|

Applications in each category |

Panel’s funding recommendations |

Minister’s funding decisions |

|

Round three |

||

|

95 applications in RFF |

95 recommended for $38.3 million |

67 approved for $26.1 million, other 28 applications rejected |

|

20 applications in SFF |

(none recommended) |

3 approved for $1.5 million |

|

77 applications in NRF |

(none recommended) |

9 approved for $3.6 million |

|

Round four |

||

|

34 applications in RFF |

34 recommended for $172.5 million |

21 approved for $91.7 million, other 13 applications rejected |

|

19 applications in SFF |

(none recommended) |

7 approved for $16.5 million |

|

106 applications in NRF |

(none recommended) |

14 approved for $87.0 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and conduct of the third and fourth funding rounds of the Regional Development Australia Fund.

7. The scope of the audit included the processes by which proposals were sought and assessed and successful projects were approved for funding. The audit criteria reflected the financial and grants administration frameworks then in effect, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs)4, as well as ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guide.

Overall conclusion

8. The Regional Development Australia Fund (RDAF) was introduced following the 2010 election as part of a $1.4 billion commitment to support the infrastructure needs and economic growth of regional Australia. The third and fourth RDAF funding rounds were conducted between October 2012 and June 2013. There was significant interest in the opportunity to compete for Australian Government funding, with more than 900 expressions of interest received, seeking over $2.5 billion in funding compared with the $225 million that was announced as being available. As it eventuated, more than $226 million in grant funding was awarded across the two rounds to support 121 capital infrastructure projects.

9. The award of funding was undertaken through a two-stage application process that initially involved the 55 Regional Development Australia (RDA) committees shortlisting expressions of interest and assigning a priority to each project in their region, prior to full applications being submitted to the Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport (DRALGAS, or ‘the department’). Those applications were then assessed by the department, which included assigning each eligible application a rating against each selection criterion. Improvements in the quality of the department’s assessment work, and of its application lodgement processes, were evident. An advisory panel, whose five members were selected for their experience, knowledge and expertise on regional Australia, was responsible for assessing the eligible applications and providing funding recommendations to the then Minister for Regional Services, Local Communities and Territories. The Minister made her funding decisions in May 2013 for round three and over May and June 2013 for round four.

10. The assessment and selection process as it was described in the program guidelines reflected a sound approach. However, in the manner implemented, the stages were not well integrated in that each step informed the next in only a limited way. As a result, there was not a clear trail through the assessment stages to demonstrate that the projects awarded funding were those that had the greatest merit in terms of the published program guidelines. In particular:

- the order of regional priority allocated to projects by the RDA committees was not used by the department or the panel at any point in the assessment of applications, and was not provided to the Minister to inform her decision-making;

- the panel categorised applications as ‘recommended’, ‘suitable’ and ‘not recommended’, but its categorisation was not supported by a documented assessment, by the panel, of the merits of each eligible application in terms of the published selection criteria. Rather, the panel advised ANAO that it considered and applied the selection criteria ‘in their entirety’;

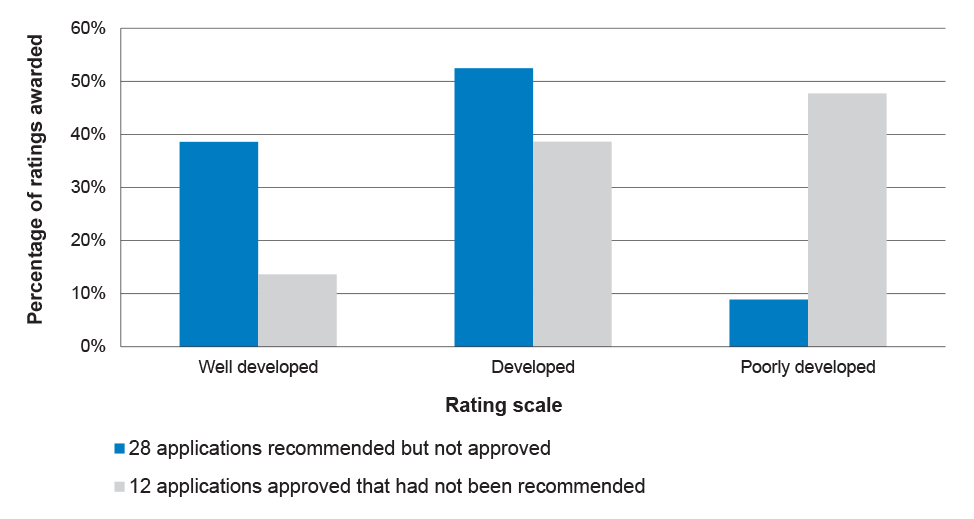

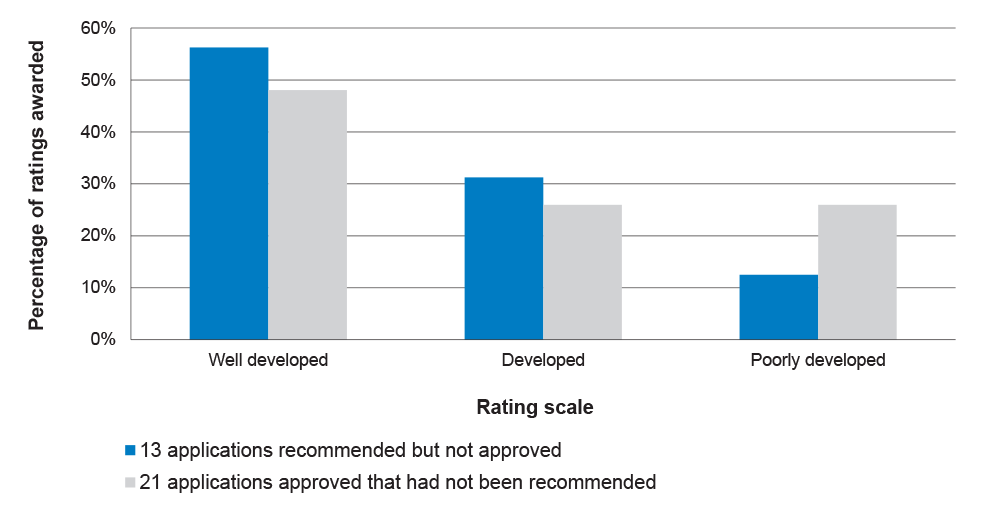

- the only recorded assessment of each eligible application against each of the published selection criteria was that undertaken by the department5; however a third of the applications awarded the highest possible rating against each selection criterion by the department were assigned to the lowest merit category by the panel;

- 27 per cent of the applications approved by the Minister, representing 48 per cent of total funding awarded, had not been included by the panel in the ‘Recommended for Funding’ category (as the panel did not consider them to be of sufficient quality). These applications represented:

- 15 per cent of approved round three applications (and 16 per cent of approved round three funding) categorised by the panel as other than ‘Recommended for Funding’, three quarters of which had been categorised as ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ with the remaining quarter classified as ‘Suitable for Funding’6; and

- 50 per cent of approved round four applications (involving 53 per cent of approved round four funding) categorised by the panel as other than ‘Recommended for Funding’. Two-thirds of these applications had been categorised as ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ with the other third categorised as ‘Suitable for Funding’7; and

- 56 per cent of those applications awarded funding had been assessed by the department to not satisfactorily meet one or more of the selection criteria.8

11. The absence of alignment or a clear trail between the assessed merit of applications against the published selection criteria and the rounds three and four funding decisions was a similar situation to that observed in ANAO’s audit of the first RDAF funding round.9 This shows that the recommendations made in the first audit, agreed by the department, had not been implemented by the department, and inadequate attention was given to relevant aspects of the grants administration framework. Effectively implementing agreed recommendations (which often reflect ANAO’s experience of practices other departments have found to be beneficial) and closer adherence to identified principles of better practice grants administration are matters that warrant greater attention by the department. In light of the findings of this current audit, ANAO has made a further three recommendations to DIRD directed at:

- improving the efficiency of two-stage grant application processes;

- a more rigorous approach to assessing whether candidates for grant funding will provide value with public money; and

- improving the quality and clarity of advice provided to Ministers to inform their decisions about the relative merits of proposals competing for grant funding.

12. A further similarity between the third and fourth RDAF rounds and the first round was that a relatively high proportion of approved projects had not been recommended for approval by the panel.10 In each of the four rounds, the panel recommended that funding be approved only for those applications it had included in the ‘Recommended for Funding’ category. This reflected the design of the program, where the three categories to be used by the panel (see paragraph 4) were intended to distinguish between the assessed relative merit of groups of applications. In this respect, the published operating procedures for the panel required that applications categorised as:

- ‘Recommended for Funding’ have been assessed as meritorious, meeting the selection criteria to a high degree and having a strong positive impact on the region;

- ‘Suitable for Funding’ have been assessed to meet the selection criteria and have a positive impact on the region but are considered to be not as strong as those categorised as ‘Recommended for Funding’; and

- ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ have been assessed as not strong and to have no identifiable positive impact on the broader community.

13. However, the Minister has informed the ANAO that: she had been advised by the department, and was always of the understanding, that projects in both the ‘Recommended for Funding’ and ‘Suitable for Funding’ categories were available for selection; in choosing projects from both categories she was complying with the program guidelines; and she would have reported to the Finance Minister her decisions to award funding to an application included in the ‘Suitable for Funding’ category if she had believed that the panel had not recommended them for funding.11 In this context, focusing solely on those applications approved for funding in the ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ category12, the proportion of applications approved for funding against panel advice falls (from 27 per cent) but nevertheless remains significant (at 19 per cent of all applications approved, comprising 11 per cent of approved round three applications and 33 per cent of round four applications). In terms of the proportion of funding approved, 40 per cent ($90.6 million) was awarded to applications categorised as ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ (comprising 11 per cent of the round three funding and 45 per cent of the round four funding awarded).

14. ANAO sought advice from the department on whether officers responsible for briefing the Minister on the outcome of the funding rounds had provided such advice to the Minister. In response, the department outlined to ANAO that it had: briefed the Minister that rounds three and four involved discretionary grant funding; identified the applications the panel had recommended be awarded funding (being those in the ‘Recommended for Funding’ category); and advised her that she should review the list of projects recommended and satisfy herself as to the benefits of each project and that, should she disagree with the recommendations and choose other projects, then the reasons for these decisions should be recorded.

15. Setting aside the different perspectives of the Minister and the department, the then Government’s guidelines for this program provided for the advisory panel to make the recommendations to the Minister as to those applications that should be awarded funding. Further, the grants administration framework has been designed to accommodate situations where decision-makers do not accept the advice they receive. Amongst other things, it requires that the basis for funding decisions be recorded.13 However, the records of the reasons for funding decisions taken contrary to panel advice generally provided little insight as to their basis and made no reference to the published selection criteria.14 This situation was particularly significant given that such decisions were largely at the expense of projects located in electorates held by the Coalition. Specifically:

- 80 per cent of Ministerial decisions to not award funding to applications recommended by the advisory panel related to projects located in Coalition-held electorates. This was most notably the case in round three, where 93 per cent of those recommended applications that were rejected were located in Coalition-held electorates. For round four, 54 per cent of recommended applications that were rejected were located in Coalition-held electorates; and

- 64 per cent of Ministerial decisions to fund applications that had been categorised by the panel as other than ‘Recommended for Funding’ related to ALP-held electorates15 compared with the 18 per cent relating to Coalition-held electorates. Having regard to the Minister’s advice to ANAO (see paragraph 13) that she viewed only those applications categorised as ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ as involving the approval of a not recommended application, 57 per cent of approved applications from this category related to ALP-held electorates compared with 17 per cent relating to Coalition-held electorates.16

16. Performance audits have been undertaken of each of the major regional grant funding programs introduced by successive governments over the last eleven years.17 Over this period, improvements have been observed in some important aspects of the design and implementation of regional grant programs. Nevertheless, in respect to each successive program there have been shortcomings in the design and administration of the assessment and decision-making processes, and indicators of bias in the awarding of funding to government-held electorates.

17. Such situations detract from the measures that have been implemented to date to make improvements to the grants administration framework, noting that it was experience with one of the earlier regional grant funding programs that was a catalyst for the introduction of the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines. More importantly, these situations detract from the ability of grant funding programs to deliver on their policy objectives to the extent practicable, and are detrimental to those communities that would have benefited had funding been awarded to those projects that had been assessed, in a structured way, to be the most meritorious in terms of the published program guidelines.

18. Against this background, a key message from ANAO audits of grant programs over the years, and highlighted in ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guides18, is that selecting the best grant applications that demonstrably satisfy well-constructed selection criteria promotes optimal outcomes for least administrative effort and cost. Another recurring theme in the ANAO’s audits of grants administration has been the importance of grant programs being implemented in a manner that accords with published program guidelines so that applicants are treated equitably. Similarly, the grants administration framework was developed based, in part, on recognition that potential applicants and other stakeholders have a right to expect that program funding decisions will be made in a manner, and on a basis, consistent with the published program guidelines.19 There is also an important message here for agencies to underline this expectation in advice to Ministers so as to avoid any misunderstandings and promote informed decision-making.

19. In this context, the most important message from this audit is that considerable work remains to be done to design and conduct regional grant programs in a way where funding is awarded, and can be seen to have been awarded, to those applications that demonstrate the greatest merit in terms of the published program guidelines. Ministers can show the way here by emphasising the importance of adhering to the published program guidelines, and discharging their responsibilities in accordance with wide considerations of public interest and without regard to considerations of a party political nature.20 History shows that this is particularly important in the lead-up to a Federal election.

Key findings by chapter

Regional Development Australia Committees’ Assessment of Expressions of Interest (Chapter 2)

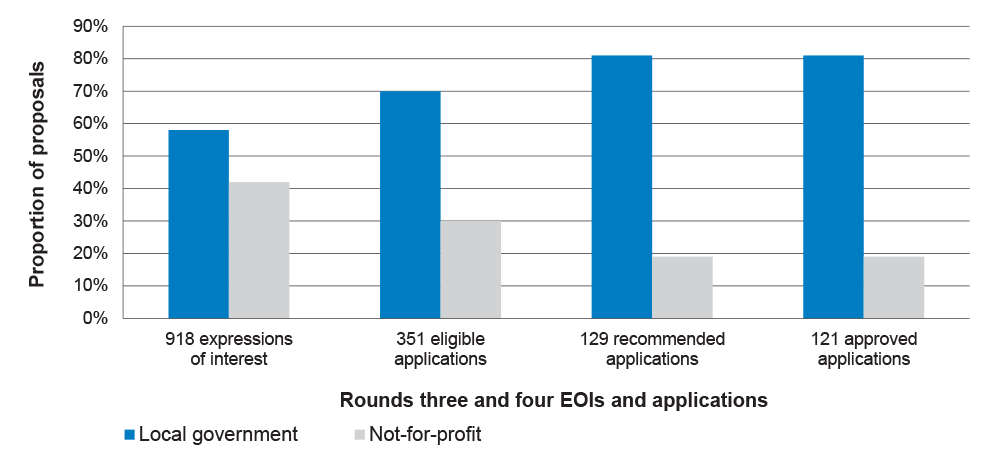

20. Compared with the one-stage process used in the first RDAF round, the two-stage application process used in later rounds improved the accessibility of the program, and was more cost-effective to administer. Proponents of 392 of the 918 EOIs submitted in rounds three and four were invited to lodge a full application. Further, consistent with the program’s objective of funding projects that meet community priorities and needs, the majority (95 per cent) of these had been endorsed by an RDA committee as being a priority project for the community and/or region. Nevertheless, there were two design elements of the program that could have been further improved, namely:

- the results of the RDA committees’ assessment of projects in terms of their individual and relative benefits to the community and/or region were not used in the assessment or selection of those same projects at full application stage, notwithstanding that these issues were directly relevant to two of the selection criteria and the program’s objective; and

- an assessment of project or applicant eligibility was not incorporated into the design of the EOI stage. This lead to a small number of proponents being invited to submit full applications only to be informed some months later that the applications were ineligible for reasons that could have been determined at the EOI stage.

Department’s Assessment of Applications (Chapter 3)

21. Compared with predecessor programs, improvements in the quality of the department’s assessment work were evident in the first RDAF round audited by ANAO, and this trend continued in the third and fourth funding rounds. This was particularly the case in relation to the eligibility checking and the conduct of risk assessments. In addition, the application lodgement and receipt processes were improved compared with those adopted in the first RDAF round.

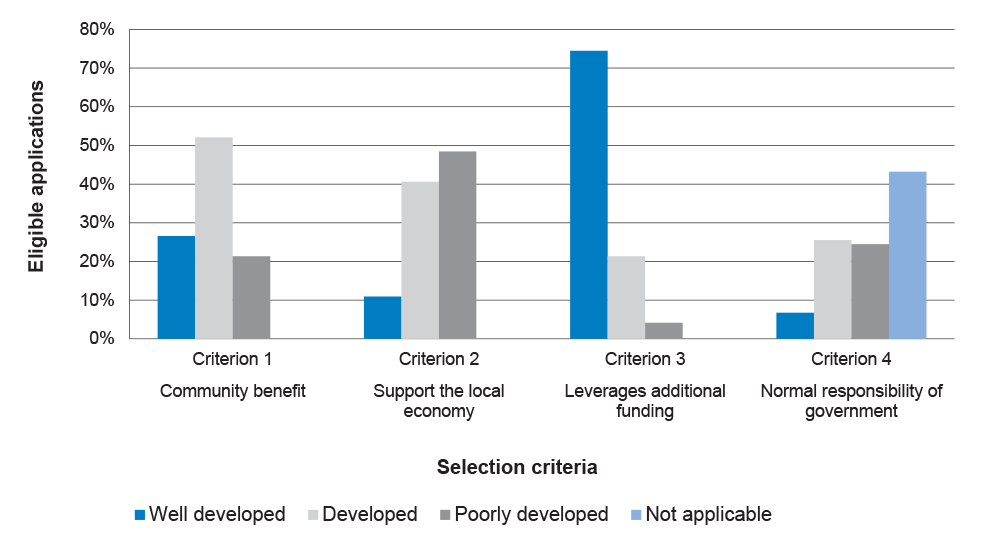

22. However, there remained significant shortcomings in the methodology employed to assess the merit of competing applications in terms of the published selection criteria. DRALGAS had agreed to two recommendations made in ANAO’s audit of the first funding round that were designed to address these shortcomings. However, instead of fully implementing these recommendations, the department retained:

- the same qualitative rating scale it had used in the first funding round, notwithstanding that it does not provide a clear and consistent basis for effectively discriminating between the relative merits of competing applications; and

- an unsound methodology for assessing value with public money that saw applications assessed as not satisfactorily meeting up to three of the four selection criteria identified as representing value with money. As has previously been observed by ANAO, applications that do not satisfactorily meet each of the published selection criteria are most unlikely to represent value with public money in terms of the objectives of the granting activity.

Panel’s Assessment of Eligible Applications (Chapter 4)

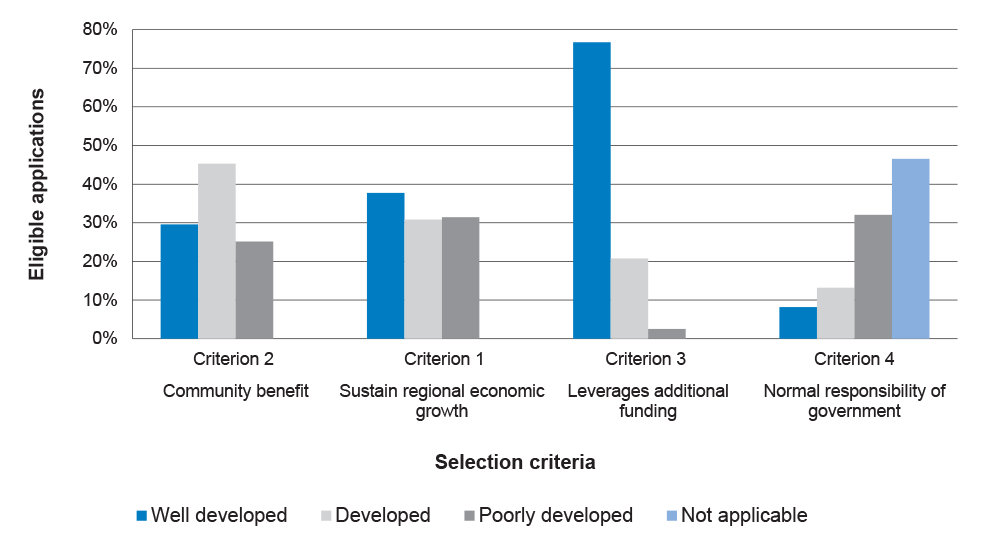

23. The RDAF advisory panel was tasked with considering the individual and relative merits of 192 eligible applications in round three, and 159 eligible applications in round four, and with recommending the most meritorious to the Minister. DRALGAS provided the panel with information and secretariat support to undertake this role.

24. Notwithstanding that the department and the panel had the benefit of two previous funding rounds to learn from, and the findings and recommendations of an ANAO performance audit of the first round, the methodology the panel had developed in August 2011 on the first day of its deliberations for the first funding round continued to be applied in May 2013 for rounds three and four. As a result, and notwithstanding that the program guidelines required the panel to assess and rank eligible applications based on the published selection criteria, there were no documented panel assessments of each application in relation to those criteria.

25. As required by the program guidelines, the panel categorised each eligible application in each round as ‘Recommended for Funding’ (RFF), ‘Suitable for Funding’ (SFF) or ‘Not Recommended for Funding’ (NRF). The panel was also required by the published guidelines to rank those categorised as RFF and SFF in order of merit. The panel chose to rank large numbers of applications equally by grouping them into a small number of bands. This approach represented a marked decline in the degree of differentiation offered to the Minister compared to the first funding round. Specifically, in the first round the panel had individually ranked each application in the RFF category as well as the 39 highest priority applications in the SFF category.21 For rounds three and four, the extent to which the Minister did not approve applications categorised by the panel as RFF was considerably higher than round one but the Minister did not have the benefit of applications in the SFF category being individually ranked so that it was not possible for her to work through those applications in the manner that had occurred in round one.

26. The panel recommended that the Minister fund the applications it had categorised as RFF. In round three, the panel also proposed that a lower level of funding be provided for three of the 95 recommended applications, reducing the total amount required to $38.3 million. This represented a considerable shortfall compared with the available funding of $50 million. While it is important that only applications that will demonstrably provide value for the public money involved be recommended for funding, it was not clear from the panel records why none of the 97 applications remaining were considered to be of sufficient merit. Of note was that each of these 97 applications had proceeded through the EOI stage, having been endorsed as a regional priority by an RDA committee, and a number had then been assessed by DRALGAS as satisfactorily meeting the selection criteria.

27. In round four, the panel proposed that the grant amount be reduced for 12 of the 34 applications it had recommended. This reduced the total amount required to $172.5 million, down from the $201 million requested by the applicants. While the maximum grant value advised to applicants was $15 million in round four, the panel recommended that applicants be provided with a maximum grant of $10 million ‘to ensure that both the impact and leverage of funds was maximised’. This figure was applied as a blanket cap to 25 of the applications categorised as either SFF or NRF by the panel, of which six were later approved for funding.

28. Similar with the first funding round previously audited by ANAO, there was not a clear trail between the applications ranked most highly against the selection criteria by DRALGAS and those recommended for funding by the panel. For example, half of the applications that had achieved ratings of ‘well developed’ against every selection criterion in round four were assigned by the panel to the lowest category in terms of merit. Instead, the majority of funding was proposed for relatively lower ranked applications (including ones rated ‘poorly developed’ against the two criteria assessing community and economic benefit to the region).

29. In these circumstances, while the panel viewed those projects it recommended as being of the highest quality, the approach the panel adopted to determining its recommendations was not consistent with a transparent, competitive, merit-based process to awarding grant funding in accordance with an assessment of applications against the published criteria. This situation reflects shortcomings in the overall design of the assessment process, particularly the insufficient linkages evident between the three assessment stages (shortlisting of EOIs by RDA committees; DRALGAS’ detailed assessment of applications, including against the published selection criteria; and the advisory panel’s deliberations and recommendations).

30. Additionally, it reflects that the department’s records of panel meetings exhibited similar inadequacies to those identified by ANAO in the audit of the first RDAF funding round. In particular, in a number of situations either no rationale for the panel’s decision was recorded or the recorded comment did not clearly relate to the decision taken. As well as being inconsistent with its previous advice to ANAO that it would address the record-keeping shortcomings identified in the audit of the first funding round, the approach taken by DRALGAS contradicted the program guidelines which had stated that the rationale for the panel’s decisions would be recorded. Overall, the approach taken did not support transparent and informed decision-making in the spending of public money through a granting activity.

Minister’s Funding Decisions (Chapter 5)

31. The enhanced grants administration framework has a particular focus on the establishment of transparent and accountable decision-making processes for the awarding of grants. Key underpinnings of that framework are that Ministers:

- not approve a proposed grant without first receiving agency advice on its merits relative to the relevant program’s guidelines;

- record the basis of each approval, in addition to the terms of the approval; and

- report to the Finance Minister all instances where they approve grants that the relevant agency recommended be rejected.

32. These requirements, together with other related enhancements to the grants administration framework, do not affect a Minister’s right to decide on the awarding of grants. Rather, they provide for an improved decision-making framework such that, where Ministers elect to assume a decision-making role in relation to the award of grants, they are well-informed of the assessment of the merits of grant applications and suitably briefed on any other relevant considerations. The requirements also seek to promote transparency of the reasons for decisions.

33. Against this background, the approach taken to advising the Minister as to which round three and four applications should be awarded funding had a number of significant shortcomings. In particular:

- applications were banded into a small number of categories22, which offered the Minister limited assistance in terms of delineating the relative merits of competing applications;

- the briefing materials were voluminous23, with insufficient summary material provided by the department. Such an approach makes it difficult for any decision-maker to compare the assessed merits of competing applications; and

- similar to the first round and notwithstanding the department agreeing to an ANAO recommendation that it enhance the documentation provided to the Minister to ensure assessment outcomes aligned with funding recommendations, the assessment of individual eligible applications against the published criteria (as recorded by the department and provided to the Minister) did not align with the panel’s categorisation of applications.24

34. Funding decisions were taken in May and June 2013. For round three, 79 projects were approved for funding of $31.1 million, with the remaining $18.9 million (38 per cent) reallocated to regional infrastructure projects under round four. This meant that the award of funding did not deliver on the commitment to quarantine $50 million of RDAF funding for projects in small towns, notwithstanding the high level of participation by small towns in the program (440 EOIs had been submitted under round three, seeking $162.4 million).

35. The Minister approved 42 projects for a total of $195.2 million in round four, compared with the $175 million that had been advertised as available under this round. In this respect, at funding approval stage, a total of $199.4 million was available. This comprised the original allocation of $175 million, $18.9 million reallocated from the underspend in round three and $5.5 million that became available following the early termination of a round one funding agreement.

36. A feature of the round three and round four decision-making was the lack of alignment with the assessment advice provided to inform those decisions. It is difficult to see such a result as being consistent with the competitive merit-based selection process outlined in the published program guidelines:

- only 53 (44 per cent) of the 121 approved applications had been assessed by the department as satisfying each of the published selection criteria.25 Further, among those applications not approved were 79 applications seeking a total of $292 million that had been assessed as satisfying each selection criterion and as representing value with public money; and

- nearly half of the funding awarded (48 per cent) went to applications that had not been recommended by the panel and a third of recommended applications were not approved. Specifically, the Minister:

- rejected 41 projects that had been recommended for funding of $93 million; and

- approved $109 million in funding for 33 projects that had not been recommended by the panel.

37. It is open to a Minister to reach a decision different from that recommended. In such cases, it would be expected that the recorded basis for each decision would outline how the Minister arrived at a different view as to the application’s merits relative to the published selection criteria. However, none of the recorded bases for the 74 decisions at odds with the panel’s advice directly referenced the selection criteria. Rather, the records tended toward generalised statements such as ‘based on my knowledge and expertise I have judged this to have strong regional benefit’; an approach that does not sit comfortably with the grants administration framework which requires the basis for grant funding decisions to be recorded.

38. Further, in recording why she approved some of the applications not categorised by the panel as ‘Recommended for Funding’, the then Minister recorded that her reason was ‘support panel recommendation’, which was the same annotation made in relation to decisions to approve applications that the panel had recommended for funding. This approach was consistent with the Minister’s advice to ANAO that: she viewed applications included in the ‘Suitable for Funding’ category as available for selection similar to those categorised as ‘Recommended for Funding’; in choosing projects from both categories she was complying with the program guidelines; and she did not need to report the approval of applications categorised as ‘Suitable for Funding’ to the Finance Minister. However:

- the department advised ANAO that it had: briefed the Minister that rounds three and four involved discretionary grant funding; identified the applications the panel had recommended be awarded funding (being those in the ‘Recommended for Funding’ category); and advised her that she should review the list of projects recommended and satisfy herself as to the benefits of each project and that, should she disagree with the recommendations and choose other projects, then the reasons for these decisions should be recorded;

- ANAO’s audit of the first RDAF funding round had outlined that the approval of funding for applications categorised as ‘Suitable for Funding’ involved, in the context of the grants administration framework, the approval of applications that the panel had ‘recommended be rejected’, and therefore should be included in the reporting of such instances to the Finance Minister;

- program governance documentation for rounds three and four, including the published guidelines and the published panel operating procedures, identified that the ‘Suitable for Funding’ and ‘Recommended for Funding’ categories were to comprise applications of differing merit. In this respect, advice to ANAO from the panel confirmed that it considered applications other than those in the ‘Recommended for Funding’ category to be ‘not of significantly high quality’ and ‘not of a high enough standard’ to be recommended for funding; and

- the department’s written briefings provided to the Minister, and the letters to the Minister from the panel in respect to each round, clearly identified that the panel was recommending for funding only those applications in the ‘Recommended for Funding’ category.

39. Nevertheless, the Minister’s advice to ANAO highlights that the ‘Suitable for Funding’ descriptor was not a particularly helpful descriptor. This situation also underscores the benefit of DIRD, in future granting activities, providing a clear statement for each grant proposal to either approve or reject the proposal.

Transparency and Accountability (Chapter 6)

40. In a number of important respects, the conduct of the third and fourth RDAF funding rounds was not consistent with the accountability and transparency principles outlined in the grants administration framework. Of particular note was that:

- grants reporting and responses to Senate Estimates questioning has not disclosed the significant extent to which grant funding was approved in respect to applications that the panel had not recommended be funded;

- those unsuccessful applicants that had been recommended for funding were not provided with accurate and complete feedback; and

- the recording of reasons for funding decisions did not adequately explain how the preference evident for projects located in Australian Labor Party (ALP)-held electorates had resulted from a merit-based process. In particular, those projects had a much higher approval rate than those located in Coalition-held electorates.26

41. In addition, experience with the third and fourth RDAF funding rounds also drew to attention a gap in one of the transparency and accountability mechanisms within the grants reporting framework. Specifically, where Ministers of the former government had approved grant applications the relevant agency had recommended be rejected in the months prior to the election, there is no obligation for there to be any reporting of those decisions.27 By way of comparison, any decisions in a non-election year to award funding to not recommended applications is required to be reported.28

Summary of entity responses

42. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 was provided to DIRD. The proposed report was also issued to the then Minister for Regional Services, Local Communities and Territories and the members of the former RDAF advisory panel with an invitation to them to provide a formal response for publication. An extract of the proposed report, relating to the grants framework reporting requirements, was provided to the Department of Finance.

43. A summary of DIRD’s response to the proposed audit report is below, with the full responses provided by DIRD and the Department of Finance at Appendix 1. The then Minister and the former panel also provided responses to the proposed report. The then Minister’s response, with related ANAO comments, is included at Appendix 2. The former panel also requested that an earlier submission that it provided to ANAO be published with its response. This material, with related ANAO comments, is included at Appendix 3.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development

I appreciate the ANAO acknowledgement:

- that the implementation of the two-stage application process improved cost effectiveness and accessibility;

- of the continued improvement in the quality of the Department’s assessment work, in particular the significant improvements in relation to eligibility checks and risk assessments; and

- of the work undertaken to improve the application lodgement and receipt processes to reduce the burden on applicants.

I also acknowledge that the audit report will assist in the future delivery of my Department’s grant programmes and undertake to consider the findings of the report in the ongoing development and management of programme implementation processes.

… The report has raised a number of significant issues that have been addressed through the Department’s responses to the Issues Papers. I note that on some occasions the Department and ANAO have differing views on the issues raised in the report, however, I appreciate that both organisations are working to the same goal of providing effective grant programmes with consistent and transparent outcomes for Government.

Recommendations

Set out below are the ANAO’s recommendations and DIRD’s abbreviated responses. More detailed responses from DIRD are shown in the body of the report immediately after each recommendation.

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.49 |

To improve the efficiency and effectiveness of any future two-stage grant application process, ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development: (a) include an assessment of eligibility considerations as part of the design of the expression of interest stage so as to minimise the risk of ineligible applications being received and allow the second assessment stage to focus on merit considerations; and (b) minimise duplication of effort, and provide a clear line of sight through the assessment process, by drawing upon the results of the assessment of expressions of interest where there are similarities or inter-relationships between some of the shortlisting criteria for expressions of interest and the assessment criteria for full applications. DIRD’s response: Agree. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.76 |

ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development incorporate in the value with money methodology adopted in future granting activities an approach that reflects that applications assessed as not satisfactorily meeting the published merit assessment criteria are most unlikely to represent value with public money in terms of the objectives of the granting activity. DIRD’s response: Noted. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 5.61 |

To improve the quality and clarity of advice provided to decision-makers, ANAO recommends that in future advice on the merits of proposed grants where funding is to be allocated using a competitive merit-based selection process, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development provide advice that: (a) clearly and consistently establishes the comparative merit of applications relative to the program guidelines and merit criteria; and (b) includes a high level summary of the assessment results of each of the competing proposals in terms of their merit against the published criteria. DIRD’s response: Agree. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Regional Development Australia Fund and of the ANAO performance audit of the first funding round. It also outlines the objective, scope and criteria of the audit of funding rounds three and four.

Background

1.1 The Regional Development Australia Fund (RDAF) was a national grants program established in early 2011 to fund projects that supported the infrastructure needs and economic and community growth of Australia’s regions. It was expected that nearly $1 billion would be allocated under the program through discrete funding rounds.

1.2 RDAF resulted from the Labor Government’s 2010 agreement with Independent members Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott. Also in accordance with this agreement, the Department of Regional Australia, Regional Development and Local Government was established in September 2010. Its responsibilities included establishing and administering RDAF. The department was subsequently affected by two machinery of government changes. The first was in December 2011, when it became the Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport (DRALGAS).29 The second occurred in September 2013, following the change of government, when DRALGAS was abolished and administrative responsibility for regional development, local government and services to territories moved to the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD).30

Overview of the funding rounds

1.3 The first four rounds of RDAF were conducted between 2011 and 2013 and were open to applications from local government and eligible not-for-profit organisations. A total of $575.8 million was approved to fund 202 capital infrastructure projects across Australia. The amount approved per funding round is outlined in Table 1.1. A further two funding rounds were commenced but not completed. In both of these cases, non-competitive processes were used.

Table 1.1: Applications and funding approved in rounds one to four

|

Funding round |

Date round opened |

Applications approved |

Funding approved |

|

Round one |

3 March 2011 |

35 |

$149.7 million |

|

Round two |

3 November 2011 |

46 |

$199.8 million |

|

Round three |

26 October 2012 |

79 |

$31.1 million |

|

Round four |

26 October 2012 |

42 |

$195.2 million |

|

Total |

|

202 |

$575.8 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

Impact of the 2013 Federal election

1.4 By convention, during the period preceding an election for the House of Representatives the Government assumes a ‘caretaker’ role until the election result is clear or, if there is a change of government, until the new Government is appointed. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet publishes guidance on the conventions and practices, which include that governments avoid entering into major contracts or undertakings during the caretaker period. In respect of applications that had been approved for RDAF funding, DRALGAS:

- continued to execute funding agreements where the proponent had been sent a funding agreement for their signature and a formal letter of offer dated prior to the 2013 caretaker period commencing; and

- continued to progress funding agreement negotiations with other proponents but the funding agreements were not finalised during the caretaker period.

1.5 The new Government was sworn in on 18 September 2013 and announced on 24 October 2013 that it would seek to repeal the Minerals Resource Rent Tax (MRRT). At the time RDAF was established, the funds to be appropriated had included $573 million that was subject to the passage of the MRRT and one of the new Government’s MRRT-related measures was to discontinue RDAF. As a result, the funding for RDAF was reduced to that required to meet the existing commitments.

1.6 At the time of the change of government in September 2013, 57 of the projects approved in rounds two to four of RDAF did not have a signed funding agreement. The fate of these projects became known on 4 December 2013 when the Government announced a new Community Development Grants Programme (CDGP) providing up to $342 million towards around 300 community projects across Australia. In addition to various Coalition election commitments and uncontracted projects from the Community Infrastructure Grants Program, these included the projects approved in rounds two to four of RDAF that did not have a funding agreement in place.

1.7 The applications approved for funding under RDAF that remained under RDAF, and those that transferred to CDGP as a result of the new Government’s decision, are summarised in Table 1.2. Receipt of CDGP funding for the RDAF approved projects was subject to confirmation from the proponents that the project could continue according to the original scope and other agreed arrangements.

Table 1.2: Applications approved under RDAF that continued to be supported following the 2013 change of government

|

Funding round |

Remained under RDAF |

Included within CDGP |

||

|

|

Applications |

Approved under RDAF |

Applications |

Approved under RDAF |

|

Round one |

35 |

$149.7 million |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Round two |

44 |

$191.8 million |

11 |

$5.0 million |

|

Round three |

50 |

$19.0 million |

29 |

$12.1 million |

|

Round four |

16 |

$70.0 million |

26 |

$125.2 million |

|

Round five |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Round 5B |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Total |

145 |

$430.5 million |

56 |

$142.3 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

Note 1: Another application approved under round two (for $3 million) did not have a funding agreement in place by the 2013 change of government. The proponent elected not to continue with the project and, therefore, it was not covered under CDGP and is not included in this table.

Previous ANAO audit activity

1.8 ANAO has undertaken performance audits of each of the major regional grant funding programs of successive governments, commencing with the then Coalition government’s Regional Partnerships Program (at the request of the Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee).31 The incoming Labor government’s first major regional funding program, the Strategic Projects Component of the Regional and Local Community Infrastructure Program, was also audited.32

1.9 Similarly, ANAO undertook a performance audit of the first RDAF funding round; Audit Report No. 3 2012–13, The Design and Conduct of the First Application Round for the Regional Development Australia Fund. The audit concluded that, overall, the department’s management of the design and implementation of the first application round was effective. However, a feature of the 35 projects approved for funding was the high proportion (14 projects or 40 per cent) that had not been recommended for funding by the panel. In addition, four of the projects the panel had recommended be awarded funding were not approved by the then Minister.

1.10 ANAO made three recommendations focused on further improving key elements of the application assessment and approval processes by the department:

- adopting a numerical rating scale for the merit assessment stage of future funding rounds;

- clearly outlining to decision-makers the basis on which it has been assessed whether each application represents value with public money in the context of the published program guidelines and program objectives; and

- improving the documentation provided to the Minister in respect to the assessment of individual eligible applications against the published selection criteria to promote a clear alignment between these assessments and the order of merit for funding recommendation.

1.11 DRALGAS agreed to all three recommendations, noting in its response to the audit that it would adopt the recommendations in round three and subsequent funding rounds.

Proposed ANAO audit of the second funding round

1.12 ANAO’s audit work program published in July 2012 included a potential audit of the second RDAF funding round. However, given the findings of the ANAO audit of the first funding round and the department’s advice to ANAO that implementation of the second RDAF funding round was similar in process, ANAO agreed to a request from the department that an audit of the second funding round not proceed. The ANAO informed the department that it would instead audit the third and fourth funding rounds.

Overview of rounds three and four

1.13 The program’s objective had been revised for round two, and was revised again for rounds three and four when it became ‘to support the economies and communities of Australia’s regions by providing funding for projects that meet community priorities and needs’. The desired program outcomes were:

- investment in the regional priorities identified by local communities through Regional Development Australia (RDA) regional plans;

- sustainable regional economic development, economic diversification and increases to the economic output of local and regional economies;

- strong, dynamic and progressive regional communities which support social inclusion and ‘Closing the Gap on Indigenous Disadvantage’ and are underpinned by quality recreational, arts, cultural and social facilities; and

- Australian, state and local government, private sector and community partnerships to support investment in regional communities.

1.14 Rounds three and four were announced on 23 October 2012, with their respective guidelines concurrently released on 26 October 2012. There were differences between the rounds, particularly in terms of their demographic focus, grant size and available funding. Specifically:

- round three was to provide $50 million to support projects in towns with a population of 30 000 people or less with grants of between $50 000 and $500 000; and

- round four was to provide $175 million for strategic regional infrastructure projects in regional Australia through grants of between $500 000 and $15 million.

1.15 DRALGAS continued the practice adopted in the second round of a two-stage application process, comprising a short expression of interest (EOI) followed by a ‘full’ application for invited proponents. EOIs for both rounds opened with the release of the guidelines and closed on 6 December 2012. DRALGAS then distributed these EOIs to the RDA committees to assess and rank in priority order by region. Each RDA committee was to select up to five priority projects under round three, and three priority projects under round four, to proceed to full application stage. In February 2013 the outcomes of the EOI stage were announced and the proponents of selected EOIs were invited to submit full applications.

1.16 DRALGAS was responsible for checking the full applications received for compliance with the eligibility requirements set out in the program guidelines. The department was also responsible for assessing eligible applications in terms of performance against the selection criteria, risk and value with money. The results of this assessment were provided to the RDAF advisory panel (panel) to inform its assessment and selection of projects for funding consideration.

1.17 The panel comprised five members selected for their experience, knowledge and expertise on regional Australia. The membership and role of the panel remained constant throughout the first four rounds of RDAF. The panel was to assess the individual and relative merits of eligible applications and provide advice to the then Minister for Regional Services, Local Communities and Territories on projects recommended for funding.

1.18 Under rounds three and four, projects needed to be for infrastructure related to or supporting the economy, community, arts and culture, or sport and recreation. The nature of the projects received against these categories was wide ranging. Those projects ultimately approved for RDAF funding were similarly varied, such as an upgrade to a bowling green, construction of a playground, expansion of an airport terminal, the construction of a new Indigenous art studio, development of an intermodal export freight precinct, and the construction of a youth and community centre.

Round three

1.19 Round three was to support smaller towns and municipalities through funding projects which would ‘improve liveability and sense of community’. Incorporated not-for-profit organisations with an annual average income of at least $500 000 and local government bodies were eligible to apply. Grants of between $50 000 and $500 000 were available. Unique to round three, projects needed to be located in a town with a population of 30 000 people or less.

1.20 Up to $50 million was available for allocation under round three. In summary:

- 440 EOIs were submitted seeking $162.4 million in funding;

- 216 EOIs seeking $84.7 million were invited to proceed to full application stage;

- 205 full applications were submitted seeking $82.4 million in funding;

- 95 eligible applications were recommended to the Minister by the panel for $38.3 million; and

- 79 applications were approved by the Minister for $31.1 million (including 67 of those recommended by the panel).

Round four

1.21 Round four sought to support strategic infrastructure projects, which could be located in any Australian town or city. Incorporated not-for-profit organisations with an annual average income of at least $1 million and local government bodies could apply. Applicants could request grants from $500 000 up to $15 million. At the time the round four program guidelines were released, $175 million was available for allocation. At funding approval stage, a total of $199.4 million was available. This comprised the original allocation, $18.9 million reallocated from the underspend in round three and $5.5 million following the early termination of a round one funding agreement.

1.22 In summary, under round four:

- 478 EOIs were submitted seeking $2.4 billion in funding;

- 176 EOIs seeking $1 billion were invited to proceed to full application stage;

- 163 full applications were submitted seeking $938.1 million in funding;

- 34 eligible applications were recommended to the Minister by the panel for $172.5 million; and

- 42 applications were approved by the Minister for $195.2 million (including 21 of those recommended by the panel).

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.23 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and conduct of the third and fourth funding rounds of the Regional Development Australia Fund.33

1.24 The scope of the audit included the processes by which proposals were sought and assessed and successful projects were approved for funding.

Audit criteria

1.25 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- application and eligibility assessment processes promoted open, transparent and equitable access to the available funding;

- the merit assessment process identified and ranked in priority order those eligible applications that best represented value with public money in the context of the program objectives and desired outcomes;

- the Minister, as decision-maker, was well briefed on the assessment of the merits of eligible grant applications, was provided with a clear funding recommendation and the reasons for the funding decisions were transparent (consistent with the requirements of the broader financial framework and the grants administration framework34); and

- the distribution of funding in geographic and electorate terms was consistent with the program objectives and guidelines, and was consistent with funding being awarded on the basis of competitive merit.

1.26 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $860 344. This cost represents the completion of the two concurrent audits of rounds three and four of RDAF (see footnote 33).

Report structure

1.27 The structure of this report is outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Regional Development Australia Committees’ Assessment of Expressions of Interest |

Provides an overview of the two-stage application process. It also examines the administration of the expression of interest stage and the role of the Regional Development Australia committees in the selection of priority projects to proceed to full application stage. |

|

Department’s Assessment of Applications |

Examines the process for lodging full applications and for checking their eligibility. It also examines DRALGAS’ assessment and ranking of eligible applications in terms of the selection criteria, risk and value with public money. |

|

Panel’s Assessment of Eligible Applications |

Examines the RDAF advisory panel’s assessment of eligible applications and its funding recommendations. It also addresses the provision of information to the panel by DRALGAS. |

|

Minister’s Funding Decisions |

Examines the advice provided to the Ministerial decision-maker on the individual and relative merits of applications, and the funding decisions then taken. |

|

Transparency and Accountability |

Analyses compliance with the grant reporting requirements of Ministers, the provision of feedback to unsuccessful applicants and the distribution of funding awarded. |

2. Regional Development Australia Committees’ Assessment of Expressions of Interest

This chapter provides an overview of the two-stage application process. It also examines the administration of the expression of interest stage and the role of the Regional Development Australia committees in the selection of priority projects to proceed to full application stage.

Introduction

2.1 A single-stage application process was used for the first funding round of RDAF, whereby the call for applications was open to all potential grant recipients. It attracted 553 applications seeking some $2 billion in funding. With only $100 million then available, the round was substantially oversubscribed. The allocation was subsequently increased to $150 million and funded the 35 successful applications.

2.2 Shortly after the outcomes of round one were announced, the chair of the RDAF advisory panel met with a range of applicants and other stakeholders to discuss their experiences and to identify improvements which could be made for round two. DRALGAS also encouraged stakeholders to give written feedback. Reflective of the applicant costs and frustration associated with the round one results of 63 per cent of applications being assessed as ineligible and 94 per cent being unsuccessful, stakeholder feedback supported the introduction of a two-stage application process for future rounds.

2.3 Stakeholders also called for a stronger role for RDA committees in the program. Taking on a stronger role was consistent with the origins of RDAF, which was to deliver on an agreement to fund infrastructure projects identified by the RDA committees in regional areas.35

2.4 Reflecting the feedback received, a two-stage application process was used for rounds two, three and four of RDAF. The first stage involved submission of a brief expression of interest (EOI), with each RDA committee given responsibility for assessing the projects predominately located in its region. The highest priority projects in each region were then to be invited by DRALGAS to submit full applications and compete for funding.

2.5 Against this background, ANAO examined the processes adopted for the lodgement of EOIs in rounds three and four and the assessment of EOIs by the 55 RDA committees.

Lodgement of expressions of interest

2.6 The third and fourth funding rounds of RDAF were run concurrently, but were otherwise discrete rounds with their own criteria, processes and program guidelines. Both sets of program guidelines were released on 26 October 2012, with EOIs to be emailed to DRALGAS by 6 December 2012. Local governments and eligible not-for-profit organisations could submit one EOI in each funding round, so long as they were for different projects. Each round also had its own EOI form, which was available from the department’s website. As intended, the EOI form required substantially less resources to complete than a full application.

2.7 There were 440 EOIs submitted under round three and 478 EOIs submitted under round four. The EOIs were registered by DRALGAS and then on-forwarded to the relevant RDA committee. A reconciliation process was undertaken to ensure that the EOIs had been successfully received by committees.

2.8 RDA committees were to assess the EOIs according to the processes described below. However, modified arrangements applied to the assessment of EOIs for projects located on Norfolk Island and in the Greater Western Sydney region. These arrangements are explained in paragraphs 2.25 to 2.29.

Assessment of expressions of interest by RDA committees

2.9 The program guidelines set out the process by which RDA committees were to assess the EOIs and select those to proceed to full application stage. DRALGAS also provided a suite of supporting documents to assist the committees in their role. These included guidance on maintaining probity and managing potential conflicts of interest, with RDA committees also given access to an independent probity adviser. Ad hoc guidance, updates and reminders were provided via notifications published by DRALGAS on the members-only section of the RDA website and via email correspondence.

Assessment and selection methodology

2.10 Each RDA committee was to assess the EOIs received for projects located in its region against the criteria (set out in Table 2.1) for the relevant funding round.

Table 2.1: Criteria for assessing expressions of interest

|

Round three EOI criteria |

Round four EOI criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Capacity of the project to address needs in the town and neighbouring towns. |

|

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of the published program guidelines.

2.11 In summary, the assessment and selection methodology was as follows:

- each member of the RDA committee was to assign a score out of 10 to each EOI, taking into account the criteria at Table 2.1 above—the higher the score, the more the project met these criteria and the stronger the benefits to the region;

- the scores assigned by each member were to be tallied to produce a total score for each EOI36;

- the EOI with the highest total score was to be allocated priority one, and so on until each EOI had been allocated a priority;

- members were to discuss the results, and adjust them as appropriate, to produce a final order of priority endorsed by the RDA committee; and

- up to the five highest priority projects in round three, and the three highest priority projects in round four, were to be selected by the relevant committee to be invited by DRALGAS to submit full applications.

Provision of results to DRALGAS, and departmental use of the results

2.12 According to the program guidelines, RDA committees were required to ‘advise the department of the outcome of their deliberations, including the rationale for their decisions’. A ‘scorecard’ template was provided for this purpose. Each RDA committee was to submit a completed scorecard for each funding round. At a minimum, the scorecard was to include the priority ranking and underlying rationale for each EOI assessed and was to identify those selected to proceed to full application stage.

2.13 As was required, each RDA committee submitted to the department a scorecard that identified the EOIs it had selected to proceed to full application stage. Beyond this, the level of detail varied. Some RDA committees reported more information than had been requested, such as by providing the scores assigned by each committee member. Conversely, some RDA committees provided less than the minimum requested. For example, the submitted scorecards for 12 per cent of EOIs in round three, and for 20 per cent of EOIs in round four, did not record the rationale for the committee’s decision.

2.14 The missing information was not then sought by DRALGAS. In explanation, DIRD advised ANAO in July 2014:

… the rationale for decisions and the priority allocated to projects was not used by the Department in its assessment process …

Given that RDA Committee prioritisations were not intended to be used by the Advisory Panel or the Minister in their decision making process and to reduce the compliance burden on RDA Committees, the Department did not seek information on the rationale for selection.

2.15 A result of the department not collecting such information was less accountability and transparency over the EOI process. Of particular significance in terms of the efficiency of the design of the funding rounds, was DIRD’s advice to ANAO that DRALGAS had not intended to use the results of the RDA committees’ assessment at EOI stage in the assessment of those same projects at full application stage.

2.16 Rather, the only element of the assessment results used by DRALGAS was the list of projects selected in each region. In correspondence with ANAO, DIRD described the assessment undertaken by the RDA committees as being ‘a filter process’. Further that ‘this process was to reduce the compliance burden on applicants and ensure that only projects which met regional priorities proceeded to the second stage of the application process’.

2.17 However, without diminishing the importance of their ‘filtering’ role, there would have been benefits if the priority rankings and rationale provided by RDA committees had been used to inform the assessment and selection of those same projects at full application stage. For example, their assessment of the capacity of round three projects to address needs in the town could have informed DRALGAS’ subsequent assessment of the extent to which the project would provide community benefit (see paragraph 3.37 in this regard).

2.18 While the filtering process ensured that the projects considered at full application stage were regional priorities, the projects had not been assessed as providing equal benefits to the region. Rather, the projects in each region had been ranked in order of their relative priority. Following the completion of round two, some stakeholders had expressed concern about the apparent lack of alignment between these relative priorities and the funding outcomes. Feedback to DRALGAS included that ‘RDA recommendation on the top three priorities were seen to be ignored when lower ranked projects received funding affecting their standing with stakeholders’. Also that ‘the Advisory Panel is a black box and the Guidelines should include how RDA priorities are dealt with as part of its deliberations‘. A stronger degree of alignment between the relative order of priority determined by RDA committees and the funding recommendations and outcomes would have been desirable in the context of achieving the program outcome of ‘investment in the regional priorities identified by local communities through RDA regional plans’.

2.19 The design of rounds three and four did not, however, address the above concerns about alignment. As the priorities assigned by RDA committees were not used in the full application stage, whether a round three project, for example, had been ranked first priority or fifth priority in its region had no influence on the assessment or selection process.37

Provision of assessment results to proponents

2.20 Following receipt of the scorecards from the RDA committees, DRALGAS notified all proponents of the outcome of the EOI process by email on 13 February 2013. It also published a complete list of EOIs on its website, identifying which ones had been selected to proceed to full application stage.

2.21 Proponents of selected EOIs were invited by DRALGAS to submit a full application by 27 March 2013 for round three funding and by 11 April 2013 for round four. They were directed to the web-based application form and supporting documentation.

2.22 DRALGAS also advised proponents that feedback on the relative strengths and weaknesses of their EOI could be obtained from the relevant RDA committee. Those proceeding to the second stage could also receive this feedback but the RDA committees were not to assist them in the preparation of full applications. The department issued guidance to RDA committees on providing feedback but was not otherwise involved.

Review of the assessment results and processes

2.23 The RDA committees’ decisions on the priority projects were final and there was no modification or review by DRALGAS. Giving RDA committees a high degree of autonomy was consistent with their responsibility for the RDA regional plans and the expectation that they had relevant knowledge of the priorities in their regions.

2.24 RDA committees were required to retain all documentation relating to the assessment and ranking process, including all working documents and minutes of meetings. The round two program guidelines had stated that DRALGAS would ‘review and audit the process followed by RDA committees to ensure consistency and compliance’. Similarly, in rounds three and four, a ‘frequently asked questions’ document stated ‘RDA committees should also note that the department will review processes and record-keeping in relation to the assessment of EOIs’. However, DIRD advised ANAO in February 2014 that an audit of RDA committees’ compliance with the intended EOI process in rounds two, three or four of RDAF had not been undertaken.

Assessment of expressions of interest from Norfolk Island and Greater Western Sydney

Norfolk Island

2.25 The program guidelines explained that, given Norfolk Island was not covered by an RDA committee, the Administration of Norfolk Island was permitted to submit one EOI and application in each of rounds three and four. The Administration of Norfolk Island elected to submit an EOI under each of the funding rounds. The EOIs were automatically progressed through to the next stage of the process without assessment. The Administration of Norfolk Island submitted full applications for its proposed projects, both of which were ultimately approved for funding by the Minister.

Greater Western Sydney

2.26 The RDA committee and the RDA regional plan for Sydney covered 41 local government areas, including the 14 local government areas collectively known as Greater Western Sydney. The RDAF program guidelines for rounds three and four outlined that RDA Sydney was to assess all EOIs for projects located in Greater Western Sydney and then select the priority projects to proceed under each round. This was to be undertaken as a separate exercise from its assessment and selection of EOIs from elsewhere in the Sydney region.

2.27 In the third funding round, five EOIs from Greater Western Sydney were received, assessed and ranked in order of priority by RDA Sydney. All five were selected to proceed to full application stage. Two of these applications were recommended for funding by the panel but they were not approved by the Minister on the basis that there was ‘not sufficient local benefit compared to other projects’.

2.28 There were 20 EOIs received from Greater Western Sydney in round four seeking grant funding of $117.7 million. RDA Sydney assessed and ranked them in order of priority, and then selected the three highest priority projects to proceed. However, a decision was later taken by the then Minister38 to invite the proponents of all EOIs from Greater Western Sydney to submit a full application. This meant that an additional 17 proponents from Greater Western Sydney were invited to compete for round four funding, bringing the total invited to 20 compared with a maximum of three proponents from each of the 55 RDA regions.

2.29 While no more than three projects from Greater Western Sydney were ultimately recommended or approved for funding, the decision to allow the additional 17 EOIs to proceed affected the outcome for the round, including the ability of projects that had been shortlisted by RDA committees to secure funding. Firstly, none of those recommended or approved for funding had been selected by RDA Sydney to proceed. Secondly, when the Ministerial decision-maker39 decided not to approve two of those recommended on the basis of ‘not sufficient regional benefit compared to other projects’, she had additional applications from Greater Western Sydney to select from. This culminated in Greater Western Sydney receiving the most funding of any region in round four ($19.8 million) and the equal highest number of applications approved (Melbourne East also had three approved).

Eligibility assessment of expressions of interest

2.30 Notably absent from the design of the EOI stage was any assessment of eligibility. Eligibility was to be assessed at full application stage only. This same design had been used in round two, in which 27 applications (18 per cent) were assessed as ineligible. Some stakeholders had expressed their concerns about the timing of the eligibility assessment in round two and posed a variety of solutions. Feedback to DRALGAS had included: ‘there should have been a filtering process prior to the RDA EOI stage to remove ineligible projects’; and ‘the Department should consider eligibility first then refer to RDAs to prioritise’. Alternatively, that ‘RDAs need to be able to look more closely at eligibility’. Feedback from the panel included the ‘need for step in process where priority projects chosen to proceed to full application are assessed by the Department for eligibility and advice provided on how to address eligibility related issues that might exist’.

2.31 The lessons learned from round two, as identified by departmental officers, included that ‘RDA committees selected projects which were ineligible due to their nature or the status of the applicant’. The proposed solution was to ‘consider allowing basic eligibility assessment by RDA committees to ensure three eligible projects from each RDA area are selected for full application’. However, the recorded action taken by DRALGAS in response was ‘In Rounds 3 and 4, the Department will continue to assess eligibility of projects after the EOI process and a full application has been made’.

2.32 An example of the approach taken in rounds three and four is DRALGAS’ handling of two EOIs that it had identified as being ineligible on lodgement. The applicant had submitted an EOI under round three and an EOI under round four for the same project, whereas the program guidelines stipulated that the EOIs ‘must be for different projects’. The record of the department’s decision included:

The Guidelines do not give the Department the capacity to review EOIs upon receipt for eligibility, nor do they set out any consequences if the requirements of the Guidelines are not met.

… The two EOIs should be sent to the RDA committee, per the process set out in the Guidelines. It is the responsibility of the RDA to consider each EOI, take external knowledge into account, and select the projects to proceed to full application.40

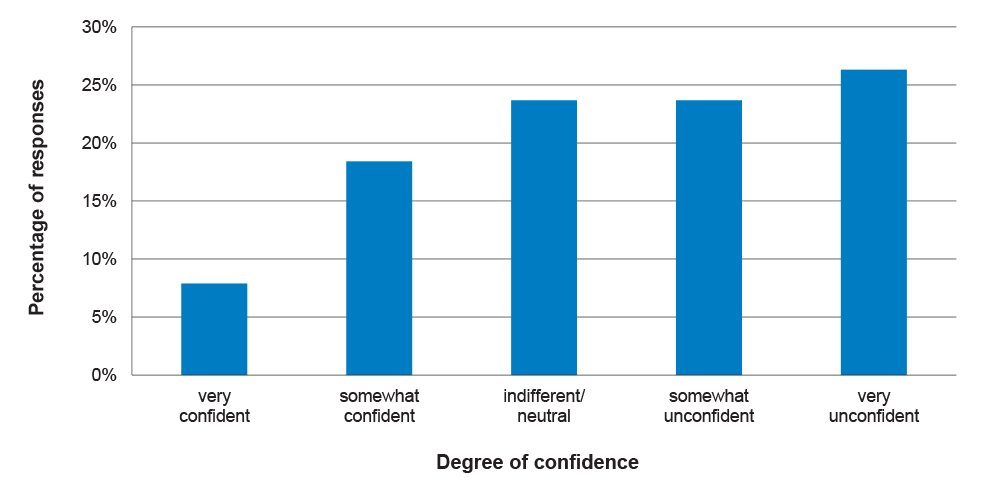

2.33 Further, while DRALGAS had advised RDA committees that ‘concerns about eligibility should be noted in the committee’s advice to the Department on the outcomes of its assessment process’, the process did not involve the department then reviewing or otherwise acting on the eligibility concerns raised. For example: