Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Conservation and Protection of National Threatened Species and Ecological Communities

The objective of the audit was to assess and report on the administration of the Act by the department in terms of protecting and conserving threatened species and threatened ecological communities in Australia.

Summary

Background

Australia is home to more than one million species of plants and animals, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth. About 85 per cent of Australia's flowering plants, 84 per cent of its mammals, 89 per cent of its reptiles, 93 per cent of its frogs, 45 per cent of its birds and 85 per cent of inshore freshwater fish are unique to Australia.1 The State of the Environment Report (2006) noted that while Australia's biodiversity is of incalculable value, biodiversity continues to decline and faces ongoing pressures.2

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the Act) is the Government's ‘flagship' legislation to protect biodiversity.3 The second reading speech for the Act noted that the loss of biodiversity represented ‘the greatest challenge currently facing Australia'. The Act was designed to provide a legal framework for the conservation and sustainable use of Australia's biodiversity. The Act requires the Minister to complete a list of threatened species and ecological communities and then develop recovery plans or conservation actions for these species and ecological communities. It also outlines a range of requirements to regulate any interaction or possible threat to the survival of listed threatened species and ecological communities. As such, the Act is demanding in terms of the administrative support required to ensure the legislative provisions are met.

In December 2006, during the latter stages of the audit, the Act was amended. The amendments were designed to ‘cut red tape and enable quicker and more strategic action to be taken on emerging environmental issues…provide greater certainty for industry while at the same time, strengthening compliance with, and enforcement of, the Act'.4 A number of specific changes were made to the listing process for threatened species and ecological communities and to the development of recovery plans. The ANAO examined compliance with the requirements of the Act prior to the introduction of amendments to the Act. Where the amendments have impacted on the audit findings the implications are discussed in the relevant chapters of the report. The recommendations of the report have been designed to take into account the amendments to the Act.

The objectives of the Act are complemented by financial assistance ($1.3 billion from 2002–2008) provided through the Natural Heritage Trust (NHT) established by the Natural Heritage Trust of Australia Act 1997. The NHT aims to help restore and conserve Australia's environment and natural resources. The financial assistance is available to eligible bodies that include regional or local catchment management organisations as well as government and community organisations. The Government also provided more specific financial support for threatened species ($36 million over four years) from 2004 through the Biodiversity Hotspots program. This program aims to protect biodiversity values in areas that are rich in biodiversity and under immediate threat. The program provides incentives to landholders and assistance to conservation groups to purchase land to be managed for conservation.

Under the administrative arrangements order (AAO) of 30 January 2007, the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources is now responsible for administering the Act and the Department of the Environment and Water Resources (the department) is responsible for dealing with matters arising under the legislation. Prior to the AAO of 30 January, and for the period largely covered by this audit, the legislation was administered by the Minister for the Environment and Heritage and supported by the Department of the Environment and Heritage.

The objective of the audit was to assess and report on the administration of the Act by the department in terms of protecting and conserving threatened species and threatened ecological communities in Australia.5

The audit was designed to provide a comprehensive report that covered the range of measures to protect and conserve threatened species and ecological communities in Australia. These include:

- the listing of threatened species and ecological communities;

- the development of recovery plans for these species and ecological communities as well as the processes to mitigate threats to them;

- implementation of recovery actions and conservation through programs such as the NHT and the Biodiversity Hotspots Program;

- assessments and approvals of actions that are likely to impact on these threatened species or ecological communities; and

- the design and implementation of compliance and enforcement actions to maintain the integrity of the Act.

The audit also followed up relevant findings and recommendations from Audit report No. 38. 2002–03 Referrals, Assessments and Approvals under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Key Findings

Listing threatened species (Chapter 2)

Listing of threatened species is the first crucial step for the Commonwealth in protecting native flora and fauna under the Act. The Act requires the Minister to develop and maintain a list of threatened species. The Minister must also list key threatening processes.6 Prior to December 2006, specific timeframes were required for listing (12 months from the date of nomination for an expert scientific committee to consider and give advice; and 90 days for the Minister to make a decision taking the advice into consideration.)

As at 30 June 2006, there were 1 684 species listed in six different categories:

- extinct;

- extinct in the wild;

- critically endangered;

- endangered;

- vulnerable; and

- conservation dependent.

Criteria for listing threatened species and ecological communities are outlined in the regulations to the Act. Since 2000, there have been 183 changes to the list of threatened species. All changes were documented and made in line with the criteria. Statutory timeframes apply to all nominations of species received from the public. Most of these timeframes have been met.

However, for marine fish7 species there were excessive delays in expert advice being forwarded from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC) to the Minister. For the nine fish species under consideration by the TSSC the average elapsed time to list a marine fish species has been over four years. The department did not formally convey the TSSC recommendations for between six and twenty-eight months. Nevertheless, the department commented that the Minister was advised of the situation and approved extensions to the statutory timeframes.

The department has indicated that the reason for these delays was that the department ‘was seeking to resolve the scientific and legal uncertainties and complexities in commercial fish nominations'. To assist in developing an approach to listing marine species, the department chose to concentrate on the Orange Roughy as a test case. The Orange Roughy was listed as ‘conservation dependant' in December 2006.

The department has now advised that nominations for the outstanding marine species will be reconsidered by the TSSC under the new listing processes. A decision on whether they will be priorities for assessment is expected by September 2007. For those deemed to be priorities a final decision on listing is expected by late 2008.

The State of the Environment Report 2006 identified that there is a ‘lack of long-term, systematic biodiversity information that would allow firm conclusions to be drawn about the details and mechanisms of the decline [of species in Australia]'8. There are uncertainties and significant scientific gaps in knowledge of species. This makes the department's task difficult in terms of keeping the list current.

However, given the current knowledge of threatened species in Australia, the ANAO found that the list of threatened species is not sufficiently up to date. Almost 85 per cent (1 430) of the 1 684 species currently listed have been carried over from the previous Act. These were listed using different criteria and different categories. Even for the top twenty species most frequently generating regulatory actions under the Act, only two had complete and up-to-date information on the reasons for listing. The department has introduced processes to address the shortcomings in the completeness of the list. However, much work remains to be completed – particularly in terms of aligning, where appropriate, the national and State lists. At the time of the audit, only the Northern Territory and Western Australian lists had been aligned. This means that there is likely to be substantial inconsistencies and gaps in the national list of species when compared to the lists in the remaining States. The importance of aligning these lists is highlighted by the example in Western Australia where eight species that were previously classified by the Commonwealth as extinct are now classified from ‘critically endangered' to ‘vulnerable'. While this process is in an early stage (it commenced in 2004), the ANAO considers that it is a worthy departmental initiative which should assist in bringing the list up-to-date over the longer term.

There is a considerable risk remaining that incorrect decisions will be made in relation to other parts of the Act because only partial or incorrect information is available. This is because a decision to list a species or ecological community establishes a legal requirement to protect the species and creates a priority for investment through programs such as the NHT. Ideally, adjusting the existing list of species and updating information on listed species should be given priority and undertaken as soon as possible. However, this is unlikely to be achieved without additional resources being allocated to the task. Resource limitations and competing priorities have constrained progress to date.

The Listing of Ecological communities and other listing processes (Chapter 3)

The Act requires the Minister to establish a list of threatened ecological communities divided into ‘critically endangered', ‘endangered' and ‘vulnerable' which reflect the different levels of risk of extinction. The timeframes required for listing are the same as for threatened species. Prior to December 2006, the Act also required the Minister to decide whether to include an ecological community from a list kept by a State or Territory and to develop inventories of species on Commonwealth land and waters.

Progress under the previous requirements of the Act in listing ecological communities was slow, with a substantial backlog in the processing of public nominations. Of the 72 public nominations received since the Act came in to force, 39 of these have been processed by the TSSC and this has resulted in 15 listings (covering 31 of the processed nominations). A substantial backlog of 33 public nominations is still to be considered by the Minister.

The ANAO identified that the reasons for the backlog in listing ecological communities were:

- the technical challenges in defining ecological communities and their boundaries within their national context;

- an expanded consultation process with stakeholders;9

- changes in priority from a focus on public nominations, to a strategic assessment of national priorities for listing ecological communities and then back to a focus on public nominations over the last six years; and

- limited resources allocated to the task.

The ANAO estimates that clearing the backlog, under the previous processes of the Act, would have taken between six and seven years to address at current resource levels. The recent amendments to the Act regarding the nominations process provide that assessments must be completed within twelve months. However, the Minister may approve a longer period if proposed by the TSSC. Nevertheless, while the scale and complexity of the task is substantial, it would be expected that assessments will be done within a reasonable timeframe to ensure nationally significant ecological communities are protected.

The new arrangements will effectively remove the backlog in publicly nominated ecological communities. In the transition between the previous Act and the amendments, nominations where the TSSC advice has been provided to the Minister prior to the amendments taking effect can be determined by the Minister without going through the new process. The department anticipates that, for any nominations where the Minister does not make such a determination, these will be considered and prioritised under the new listing process within annual assessment periods. The ANAO considers that with the current level of resources and staff dedicated to administering ecological communities, there is a high risk that nationally significant ecological communities eligible for listing will not be listed within a reasonable timeframe. The department will need to carefully consider its business strategy (including the allocation of sufficient resources) to increase its capacity to process ecological community nominations in a timely manner in the future.

In addition to processing public nominations, there was a substantial backlog of approximately 700 State and Territory ecological communities to be considered. However, amendments to the Act repealed this requirement.10 The removal of the requirement to review State and Territory threatened ecological communities creates a risk that many eligible communities not identified through public nominations will not be considered for listing. The ANAO considers that the State and Territory listed ecological communities should be at least considered by the department and the TSSC within the context of the new listing process. The department has indicated that while not all of the State/Territory ecological communities will be high priority, it is important to assess the state listings for their relevance at a national level. The department is currently looking at options to address this concern.

The documentation to support decisions on key threatening processes was sufficient to explain the reasons for their listing or rejection. Inventories of species on Commonwealth land and marine areas were developed but were not complete or comprehensive. This constrained the capacity of the Commonwealth to meet the prescribed requirements of the Act, pertaining to Commonwealth areas. The amendments to the Act have removed the requirement for inventories of species in all Commonwealth areas. However, because the amendments allow the option for inventories and surveys to be conducted, the department will need to advise the Minister as to the circumstances where an inventory should be conducted.

Recovery and threat abatement plans (Chapter 4)

Recovery plans for listed threatened species and ecological communities, and Threat Abatement Plans (TAPs) for key threatening processes are important tools in protecting biodiversity. They set out the management actions necessary to maximise the long term survival of affected species and ecological communities. They also provide a basis on which funds available for biodiversity protection and conservation can be prioritised and directed.

Prior to December 2006, the Act required the Minister to ensure that there is always in force a recovery plan for each listed threatened species and ecological community (except for those species and ecological communities categorised as ‘extinct' or ‘conservation dependent').11 TAPs may also be made to reduce the effect of a threatening process such as feral pests.12

In addition to the requirements of the Act, Commonwealth, State and Territory Ministers also committed in 2000 to have recovery plans in place for all critically endangered and endangered species by 2004.13 The commitment was not met. Only 126 species (22 per cent) of the 583 species committed had recovery plans completed by 2004. Fifteen (68 per cent) of the 21 ecological communities committed had recovery plans in place by 2004.

Statutory timeframes for producing recovery plans in Commonwealth areas were generally not met. The reasons for the poor result were a lack of sufficient resources and insufficient capacity in agencies contracted to produce recovery plans.

The ANAO considers that monitoring implementation of recovery plans by the department has also been inadequate for reporting on their effectiveness in conserving species. The department has indicated that it does not have the resources to monitor what progress is being made against the targets and requirements in the recovery plans. Consequently, the requirement in the Act to review all recovery plans and threat abatement plans every five years was not met. Of the 56 recovery plans due for review, only one review had been completed. While recognising that the amendments to the Act have shifted the focus from recovery plans to recovery actions, recovery plans still have an important role to play in protecting endangered species and ecological communities. They have also been a key outcome indicator and performance measure for the department since the inception of the Act in 2000. Consequently, further progress could reasonably have been expected.

For twelve of the seventeen listed key threatening processes, the Minister has decided to produce TAPs. Ten of the twelve plans have been finalised. In most cases, the finalisation of a TAP met the statutory timeframes of the Act.14

Departmental reporting to Parliament on progress does not distinguish between recovery plans completed and those in preparation. This does not assist Parliament in understanding the backlog in the development of recovery plans and the reasons for this. In contrast, reporting on TAPs is more informative as it includes information on the status of plans and progress against outcomes.

Commonwealth investment in biodiversity conservation actions (Chapter 5)

The NHT ($1.3 billion over six years from 2002) and the Biodiversity Hotspots ($36 million over four years from 2004) are the Australian Government's main financial assistance programs established to help restore and conserve Australia's biodiversity. The NHT has allocated funding through national, regional and local streams which target different levels of activity and different stakeholders. For example, the national stream provides funding for national activities or proposals that cut across State boundaries while the regional stream focuses on regional catchment bodies. Some $78 million was spent directly on threatened species and ecological communities which accounts for approximately seven per cent of total NHT expenditure to date. More broadly, some $251 million has been spent on biodiversity conservation (22 per cent of total NHT expenditure) from the NHT from 2002–2006.15

The NHT has supported projects that impact on threatened species and ecological communities. These have included:

- the Threatened Species Network which reported activities to benefit over 80 species and ecological communities listed under the Act in 2005–06;

- two pilot projects for regional recovery plans covering 100 nationally listed threatened species (including implementation of recovery actions for over 40 threatened species);

- financial assistance to the department to support the work of the Threatened Species Scientific Committee and enable consideration of new nominations of threatened species and ecological communities as well as recovery planning; and

- regional funding for priority investments in key regions. For example, $11.3 million to the South West region of Western Australia – a world biodiversity hotspot with significant endemic species and ecological communities under threat.

However, the department's evaluation of the program found there is a lack of standard, meaningful and quantified monitoring and evaluation systems for the national investment stream. The ANAO agrees with this conclusion and notes that this has limited the capacity of the department to report to Parliament on the extent to which NHT initiatives, funded at the national level, have contributed to program objectives.

Biodiversity conservation has not been a high priority for all NHT funded regions and where it has been a priority, the level of investment from the NHT is expected to achieve some 10-20 per cent of high priority targets Australia-wide. The relatively few regions that are monitoring trends continue to detect a decline (that is, an ongoing net loss in native vegetation extent, and continued decline in native vegetation condition). The department's program evaluation (January, 2006) found that it will take a long time and sustained high levels of investment at the regional level to achieve national biodiversity conservation objectives. In some cases, funding levels are insufficient to reverse the decline in biodiversity.

The Biodiversity Hotspots program has experienced slow progress since its announcement in 2004. The Hotspots program was designed to improve the conservation of biodiversity hotspots on private and leasehold land by enhancing active conservation management and protection of existing terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems as habitat for native plants and animals. To assist in program implementation, the TSSC identified 15 biodiversity hotspots areas in Australia. As at 30 June 2006, spending was just over one third of the total financial commitment and well behind the original appropriations.

The reason for the delay related to the time taken to settle the method by which funds would be allocated under the program, whether through a grant program or a tender process. While a matter for Ministerial decision, the delay in delivering program funds has meant that the biodiversity conservation priorities of the program have not been addressed.

Of the funds that have been spent to date under the Biodiversity Hotspots program, the ANAO found that two of the three investments already announced by the Government were not within the identified biodiversity hotspots. In addition, these two investments were made prior to finalisation of program guidelines. The guidelines were not finalised until 9 June 2006 – some two years after the program was announced.

Referrals and assessments (Chapter 6)

The Act identifies listed threatened species and ecological communities as one of the seven matters of national environmental significance. The Act requires any person to refer an action to the Minister if they consider that the action may impact on a matter of national environmental significance. The Minister must determine whether or not the action will have an impact, if so what conditions should be imposed, or whether or not the action should be approved. Advice on these actions is provided by the department through assessments on each proposed action. Assessments involve analysis and documentation of the level of risk and the most appropriate controls required for the action that has been referred.

There are significant challenges in administering referrals for legislation that relies largely on self-regulation - that is, the onus of compliance rests with individuals and organisations to decide whether or not their activities have, or are likely to have, a significant impact on a matter of national environmental significance. While the department has taken steps to improve guidelines for the promotion of required referrals under the Act, there has been no substantial increase in the overall number of referrals made under the Act. Discussions with regional bodies in North Queensland and Western Australia as well as national industry and environment groups in particular suggest that significant efforts are required to improve awareness and ensure that all referrals that should be made are actually made.

The department has begun an important pilot initiative to align local council planning schemes with the referrals and assessments under the Act. This process could assist in increasing the number of referrals and achieving a more efficient assessment process – particularly where listed threatened species or ecological communities are identified and mapped within local council boundaries. The department has also been working with industry groups to improve knowledge of their requirements under the Act.

Nevertheless, there is considerable scope for expanding this type of initiative in priority local government areas. More broadly, there is considerable scope to improve awareness of the importance of compliance with the Act – particularly in regions with significant threats to listed species and ecological communities. A program of promotion and awareness raising would lift the profile of compliance with the Act. If administrative steps are not taken to improve performance in this area, it is unlikely that the all the projects that are required to be referred to the Minister under the Act will be referred. The ANAO recognises that such an approach overall, would involve some additional resources.

In terms of assessments of proposed actions referred to the department (that is, consideration of whether or not a proposed action such as a new commercial development in an environmentally sensitive area should be subject to the requirements of the Act),16 compliance with statutory timeframes has deteriorated since 2002–03.17 Since this time, the average number of business days in excess of the statutory timeframe for a decision increased from 1.9 to 2.4 days. Amendments to the Act in this area may assist in reducing workload pressures to some extent. However, the ANAO considers that there would be benefit in the department reviewing its processes to ensure that statutory timelines are met. This would be contingent on sufficient resources being allocated to the task.

Compliance and enforcement (Chapter 7)

An effective compliance and enforcement strategy is required to ensure the integrity of the Act and that any conditions placed on approved actions by the Minister are actually carried out. Between 2000 and 2006, 419 decisions, with multiple conditions, were made by the Minister or his delegate.18 These conditions were imposed on actions to mitigate any adverse impacts on a matter of national environmental significance such as a listed threatened species.

The department has a well designed compliance and enforcement strategy and since the last ANAO audit in 2002–03, has increased its capacity to undertake compliance and enforcement activities. For example, the department has introduced a new Environment Investigations Unit, staffed by specialist investigators and out-posted officers from the Australian Federal Police and the Australian Customs Service. In 2003 the Department pursued legal action in the Federal Court which resulted in a successful civil prosecution against a farmer for illegal clearing of land in the Gwydir Wetlands.

However, implementation of the compliance and enforcement strategy has been generally slow - particularly in regard to the managing compliance with conditions on approval. The department did not have sufficient information to know whether conditions on the decisions are generally met or not. There has been insufficient follow up on compliance by the department for those individuals or organisations subject to the Act and little effective management of the information that has been provided.

Consequently, the department has not been well positioned to know whether or not the conditions that are being placed on actions are efficient or effective. This is not consistent with good practice and does not encourage adherence to conditions set by the Minister. While voluntary auditing has been carried out for a small number of decisions, auditing and reporting on compliance with the statutory decisions is not yet well developed. From a small sample of eight decisions, departmental audits found that only 58 per cent of total conditions were fully complied with. This suggests that the audit program may need to be expanded to incorporate a review of a higher number of decisions in the future.

Overall audit conclusion

Since the introduction of the Act, 152 additional species have been listed and protected under the Act and over 200 new recovery plans have been written to assist in the protection and conservation of species. The department has recently introduced a number of processes to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of the Act. However, protecting and conserving threatened species and ecological communities still remains a challenge for the department. Three key factors constraining progress and limiting the achievement of the objectives of the Act are the:

- scale of the prescribed tasks required by the legislation;

- technical requirements for assessing, protecting and conserving over a thousand individual species and hundreds of ecological communities; and

- limited resources allocated to the task.

The audit identified a number of key areas of non-compliance with the Act (prior to December 2006). These were:

- keeping the list of threatened species and ecological communities in an up to date condition;

- surveying species on Commonwealth land;

- completing recovery plans in the required timeframes; and

- reviewing State and Territory listed ecological communities.

The amendments to the Act in December 2006 mean that the matters identified in paragraph 51 are no longer legal requirements. These amendments are likely to reduce the workload of the department in the above areas. However, the department will still need to consider these matters within an administrative context where they relate to the achievement of the objectives of the Act. In other areas such as referrals and assessments, the amendments may increase work load pressures.

In addition, there has been a range of administrative shortcomings in the department's administration of the legislation. These were:

- slow progress in listing species and ecological communities, particularly for the listing of marine species and publicly nominated ecological communities;

- inadequate implementation of the compliance and enforcement of conditions of approval under the Act. (There has been no significant follow-up on compliance with the conditions set for approved actions);

- gaps in the data and documentation to support listing of species transferred from the earlier Act; and

- insufficient monitoring and enforcement of conditions of approval in respect of actions that may have an impact on a matter of national environmental significance.

The department has sought supplementary funding four times since the introduction of the Act but these were not agreed to by government. Some minor reallocations of other departmental resources were made during this time to accommodate other resourcing requirements. In 2005 the department sought to develop a cost recovery regime but this was also not agreed to by government and the department was directed to reallocate resources from other areas within the department. Financial supplementation ($18 million from 2003–04 to 2005–06) from the Natural Heritage Trust has assisted the department in administering priority areas of the Act. However, these measures have not been sufficient to address the performance shortfall in the areas identified above.

In circumstances where resources are constrained, departmental strategies for resource allocation to achieve legislative compliance should be well targeted and directed to the priority areas that will achieve the objectives of the legislation. The ANAO considers that the department was slow in the early years of the Act to adjust its strategies to ensure it met its statutory responsibilities.

The department has indicated to the ANAO that it has been very aware of its lack of capacity to properly administer the requirements of the Act. Evidence obtained during the course of the audit indicated that Environment Ministers were informed of the difficulties in meeting the statutory obligations under the Act and Ministers had noted the approaches and initiatives that have been taken to better meet the objectives of the Act.

The department has commented that since the commencement of the Act, it has worked with the TSSC to meet its statutory obligations and where this was not possible, to develop alternative approaches to meeting the general objectives of the Act. The department has introduced a number of initiatives to improve the administration of the Act. In particular, initiatives include steps to better align the national list with those of the States/Territories, better information systems to support the referrals and assessments process, and the development of pilot regional and multi-species recovery plans.

The ANAO also notes that without Commonwealth funds, delivered through the NHT, many more species and ecological communities would have no actions undertaken to protect and recover them. Nevertheless, the threats to biodiversity in Australia remain and further attention to the administration of the Act is required if its objectives are to be realised.

Future Directions (Chapter 8)

The ANAO has made eight recommendations designed to improve performance by the department and to focus attention on key directions for the future. In addition, the ANAO has highlighted those recommendations which it considers are important for early implementation:

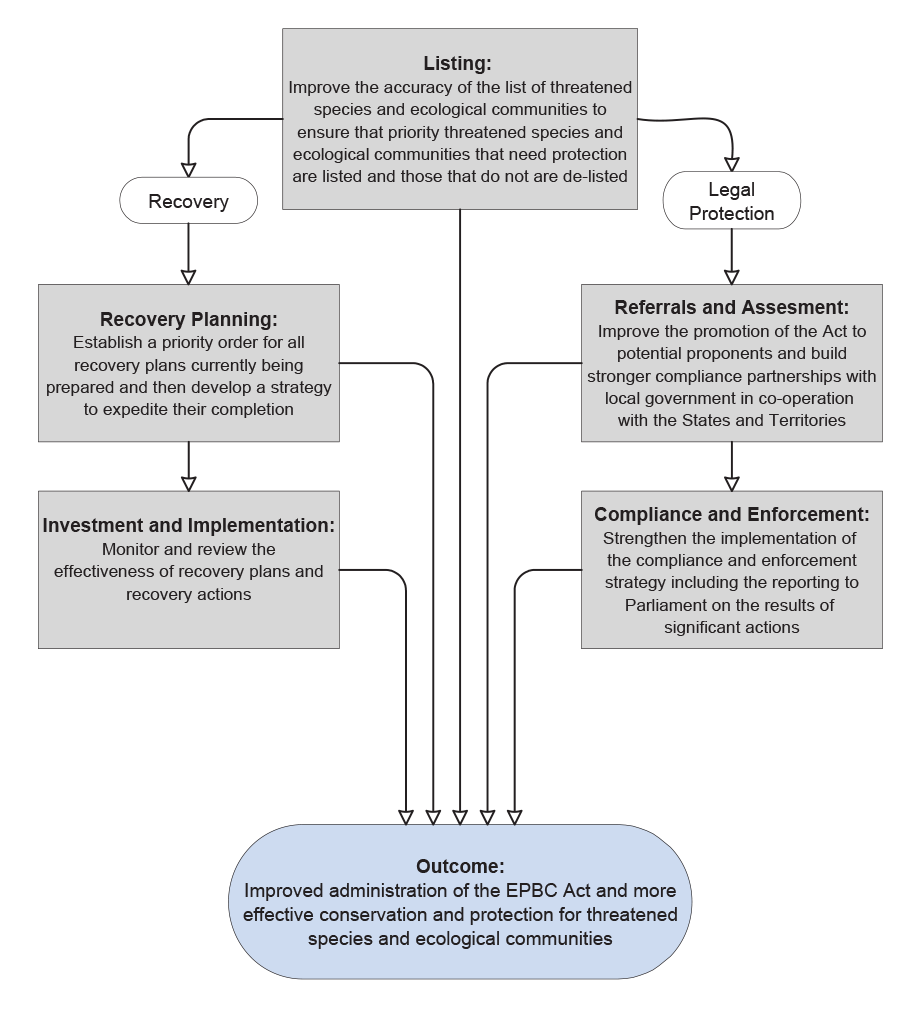

The key directions for early attention are:

- improving the accuracy and completeness of the list of threatened species and ecological communities based on the best available information to ensure that priority threatened species and ecological communities that need protection are listed and those that do not are de-listed;

- establishing a priority order for all recovery plans currently being prepared and then developing a strategy to expedite the completion of recovery plans and actions for all priority species and ecological communities with clear timetables for completion and subsequent implementation;

- improving the promotion of the requirements of the Act in priority regions of Australia; and

- strengthening the implementation of the compliance and enforcement strategy including the audits of compliance with conditions and reporting to Parliament on the results of significant actions.

The key directions for longer term attention are:

- ensuring to the extent practicable that the national list of threatened species and ecological communities is regularly updated and aligned with changes in State/Territory lists;

- building strong compliance partnerships with relevant bodies in priority regions of Australia to ensure that where practicable, that matters of national environmental significance are considered earlier in the planning process;

- considering the scope for providing assistance to local governments in priority areas of Australia to enable mapping and documentation of listed threatened species, ecological communities and critical habitat; and consolidating, disseminating and reporting on the lessons learned from the audit program each year; and

- giving sufficient priority to monitoring and reporting to Parliament on the timeliness and effectiveness of Commonwealth recovery actions for priority threatened species and ecological communities nationally.

Figure 1: Future directions

Agency Response

The Department of the Environment and Water Resources thanks the Australian National Audit Office for the work done on this audit. The Department considers the report a useful document that raises a number of important issues for this Department's administration of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, the Natural Heritage Trust and other relevant programs.

The audit is a balanced report which recognises the complexities involved in administering the Environment Protection and Conservation Act 1999 and the magnitude of some of its statutory requirements prior to the amendments passed by the Parliament in December 2006. The Department recognises that the timing of the audit created difficulties for the Australian National Audit Office with the amendments to the Act being considered during the course of the audit.

The Department believes the efforts of the Audit Office to take account of the requirements of the amended Act have made the report a more useful document that provides guidance on the way forward with administration of the Act, rather than merely looking backwards at a situation that no longer applies.

The Department agrees with the recommendations and considers they provide useful guidance on pursuing the highest priority actions to assist in meeting the objectives of the Act. The Department notes that, even under the provisions of the amended Act, however, its ability to fully implement all the recommendations will depend in part on the willingness of State and Territory agencies to collaborate on actions.

Footnotes

1 State of the Environment Advisory Council, Australia: State of the Environment Report (1996) p. 4-4.

2 State of the Environment Report (2006) Biodiversity Theme; Executive Summary p. 2.

3 Article 2 of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity defines biodiversity as ‘the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems'.

4 Environment and Heritage Legislation Amendment Bill (No 1) 2006; Second Reading Speech, p. 6.

5 The Act defines a threatened species as one that has been classified in one of six categories. For example a critically endangered species is one that is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. The Act defines an ecological community as an assemblage of native species that inhabits a particular area in nature and meets the additional criteria specified in the regulations (if any) made for the purposes of this definition.

6 S188 (3) of the Act defines a process as a key threatening process if it threatens or may threaten the survival, abundance or evolutionary development of native species or ecological communities. For example land clearing is an identified key threatening process.

7 This included four commercial fish species as well as five other fish species sometimes caught as by-catch.

8 op. cit.

9 This has the potential to produce more acceptable outcomes amongst stakeholders.

10 Not all of the 700 State and Territory ecological communities will be high priority as some will already be in national parks while others extend across state borders which will reduce the number to be considered. However, the backlog highlights the gap between expected and actual performance in meeting the requirements of the Act.

11 Amendments to the Act now require the Minister to ensure that there is approved conservation advice for each listed threatened species (except for those that are extinct or a species that is conservation dependant) and each listed threatened ecological community. The Minister now has the discretion to decide which species also require a recovery plan.

12 At the time of listing of a key threatening process, the Minister must decide whether a threat abatement plan is to be prepared.

13 National Objectives and Targets for Biodiversity Conservation for 2001–05.

14 Only one, Injury and fatality to vertebrate marine life caused by ingestion of or entanglement in, harmful marine debris is overdue. However, a draft for public comment is expected by the end of 2006.

15 The $251 million spend on biodiversity includes the $78 million spent directly on threatened species and ecological communities. It is difficult to precisely identify expenditure on biodiversity conservation as numerous projects have multiple objectives (including conservation). A significant number of initiatives funded may have indirect benefits for threatened species and ecological communities.

16 Audit Report No.38 2002–03, Referrals, Assessments and Approvals under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

17 Under the Act, the Minister must decide whether an action is subject to the requirements of the Act within 20 days of receiving the referred action.