Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Australian Taxation Office's Use of Data Matching and Analytics in Tax Administration

The objective of the audit was to evaluate the Tax Office's corporate management of data matching, including analytics.

The ANAO examined the Tax Office's strategic goals and governance arrangements for data matching and analytics, its compliance with privacy requirements and whether the Tax Office is achieving intended results, which include revenue collection, optimised compliance and provision of improved services to taxpayers.

Tax Office executives have been increasingly drawing on the interrelationships and conceptual commonalities of Tax Office data matching and analytics activity. Accordingly, the audit included these relationships and conceptual commonalities within the scope of the audit. The audit was guided, therefore, by a broader definition of ‘data matching': meaning ‘finding relationships and patterns in large volumes of data'. This includes the more traditional idea of data matching as ‘bringing together data from different sources and comparing it'.

Summary

Introduction

In 2006–07 the Australian Taxation Office's (Tax Office) revenue from income tax, indirect tax, other taxes and excise totalled some $254.8 billion.1 Australia's taxation system of self assessment places responsibility on taxpayers to declare all of their assessable income and claim only deductions and/or offsets to which they are entitled. In administering the taxation system, the Tax Office has to balance the underlying principles of self assessment with the need to manage risks, such as lack of compliance with legislation, failings in the integrity of the tax system, damage to the Tax Office's reputation, and erosion of the Commonwealth's revenue base, as efficiently and as effectively as possible.

In a self-assessment system the Tax Office seeks to achieve high levels of compliance by using the Compliance Model2 of behaviour to guide the application of risk mitigation strategies. These strategies range from the communication of information to help taxpayers fulfil their obligations to criminal prosecution to stop and deter egregious non-compliance. In terms of resource investments, audits have traditionally constituted the primary form of verification adopted by revenue bodies, including the Tax Office, to check taxpayers' compliance with their obligations. However, there are practical limitations regarding the level of taxpayer and income coverage achievable from audit activities.

Since the 1970s the Tax Office has been developing a computer-based data matching capability which is deployed to assist the mitigation of risks associated with the management of taxpayer compliance. Traditional semi automated data matching validates the income reported by taxpayers in their returns and discloses income that had not been reported to the Tax Office. In many cases it generates automatic correspondence to taxpayers.

More recently, the Tax Office has augmented traditional, semi-automated data matching with project-based data matching and analytics3 projects. The more focussed data matching projects are framed around categories of compliance risk and involve significant investigations by specialist tax officers. Most of the projects have a large research and development component. The analytics projects generally use advanced statistical and/or mathematical tools to examine a wide range of compliance risks. Once established after testing, some of the analytics projects involve semi-automated processes, which result in administrative action not unlike traditional semi automated data matching.

As the Tax Office gains more experience of the successes and challenges of these projects it is improving an evolving generic capability. The ANAO reviewed 80 data matching and analytics projects all of which indicate the scope and potential of this generic capability. In particular, it enables the bringing together and interrogation of large volumes of data from different sources. The capability has facilitated an increased capacity to make comparisons, link data sets, compare corresponding items, find relationships and patterns and construct descriptive or hypothetical representational and/or functional relationships amongst the data variables relevant to the management of compliance risks.

In summary, the Tax Office has expanded its range of computer-based strategies to support the management of compliance risks. These now range from traditional semi automated data matching to advanced analytics which create sophisticated mathematical models of varieties of serious non-compliance.

Within this expanding framework, the Tax Office defines traditional data matching as ‘the acquisition of external data used by the Tax Office for a variety of different purposes such as detection of un-disclosed income, non-lodgement of returns and activity statements, and entities outside the tax system.'4

The Tax Office undertakes two categories of data matching:

- large scale post-issue semi-automated system processing (e.g. the Tax Office's automated Australian Taxation Office matching system (ATOms) automatically matches data, including legislated data5 against data taxpayers provide directly to the Tax Office, detects discrepancies in stated income, and produces a pool of discrepant cases for compliance activity);6 and

- data matching projects (e.g. business lines7 initiate projects that involve acquiring and matching external data to internal Tax Office databases and producing a pool of cases for risk identification or compliance activity. See Appendix 2, Table A5 for a list of the Tax Office's data matching projects since 2000).

The two categories of data matching are administered by different areas of the Tax Office. The Micro Enterprises and Individuals business line is responsible for data matching in the first category. However, the Data Matching Steering Committee (DMSC) coordinates and facilitates the initiation and conduct of the data matching projects in the second category.

There are similarly two broad categories of analytics projects. Advanced analytics projects, largely based on data mining and modelling, are administered by the analytic group in the Office of the Chief Knowledge Officer. Basic analytics projects, using more conventional tools, are distributed broadly across most Tax Office business lines. Generically, analytics activities involve discovering relationships, patterns and trends in datasets, building, testing and operating data models using data provided directly to the Tax Office, internally generated data (such as the results of compliance activities) and externally sourced datasets. (See Glossary for definitions of advanced analytics, basic analytics, data modelling, and data mining).

Traditionally, Tax Office data matching has had a compliance focus, with external data being used for compliance verification purposes. However, the Tax Office has also recently begun to address in a substantial way the potential of data matching and analytics to support taxpayer service needs (and to reduce taxpayers' compliance burden, perhaps significantly). The spread and power of IT systems used by business and Government, in conjunction with more secure facilities on the World Wide Web, provides significantly increased capacity for timely electronic exchanges of data and opportunities for new and improved services to tax payers. This expanding use of high quality data, especially for the provision of web-based services at the time taxpayers complete their tax returns, represents a new paradigm in tax administration.

Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to evaluate the Tax Office's corporate management of data matching, including analytics.

The ANAO examined the Tax Office's strategic goals and governance arrangements for data matching and analytics, its compliance with privacy requirements and whether the Tax Office is achieving intended results, which include revenue collection, optimised compliance and provision of improved services to taxpayers.

Tax Office executives have been increasingly drawing on the interrelationships and conceptual commonalities of Tax Office data matching and analytics activity.8 Accordingly, the audit included these relationships and conceptual commonalities within the scope of the audit. The audit was guided, therefore, by a broader definition of ‘data matching': meaning ‘finding relationships and patterns in large volumes of data'. This includes the more traditional idea of data matching as ‘bringing together data from different sources and comparing it'.

At the conceptual level of this broader definition, traditional semi-automated Tax Office data matching is increasingly becoming an integrated element within Tax Office's more recently initiated analytics work. Accordingly, in this report, the phrase ‘data matching and analytics capability' includes all the computer-based methodologies that the Tax Office applies to bring together large volumes of data from different sources, making comparisons, linking data sets, comparing corresponding items, finding relationships and patterns and constructing descriptive or hypothetical representational and/or functional relationships.

The audit focussed on the conduct of data matching and analytics projects by Tax Office business lines, the significant synergies and interrelationships between these projects and other Tax Office activities, such as identity matching, Australian Taxation Office matching system (ATOms) and analytics projects.

Conclusion

The Tax Office is making use of its data matching and analytical capabilities in a more corporate and strategic way. This has contributed to the Tax Office reporting improved compliance, better services and the more efficient and effective use of resources. It has also enabled the Tax Office to better understand risks. Procedural arrangements have enabled the Tax Office to improve the use of data matching and analytics and comply with Privacy Commissioner Guidelines. Contact with a number of national revenue authorities of member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggest that the Tax Office is well regarded for its work in the data matching and analytics field.

The analytics group in the Office of the Chief Knowledge Officer has made a valuable contribution to tax administration during the three years since its establishment. It has pioneered many new sophisticated mathematical and statistical methodologies (see Glossary) resulting in improved compliance, improved services, and the more efficient and effective use of resources.

As a result of these achievements the Tax Office has developed a data matching and analytics capability which encompasses traditional data matching and its integration into the broader area of analytics.

The progressive implementation of the Easier, Cheaper and More Personalised Change Program (ECMP Change Program) now under way provides the Tax Office with the opportunity to get much more from the capability than previously possible. The ECMP Change Program provides for the first time, an administrative and systems environment which will enable the Tax Office to better manage the data matching and analytics capability strategically and corporately.

Although traditional semi-automated data-matching has been a feature of tax administration since the 1970s, the Tax Office has only recently developed the more comprehensive data matching and analytics capability. There is scope to improve its corporate and strategic management of this emerging capability. The development of a strategic plan for acquiring and using external data over a three to five year period would be a key step in this direction.

A high level stock take of achievements and lessons learned from the deployment of the capability would also inform the identification of opportunities for the improved management of the capability at the corporate and strategic levels.

Additionally, there is scope to improve the design and use of the Tax Office's identity matching systems especially in two areas. One concerns non individual identity matching, particularly in relation to companies, trusts and superannuation funds. The other concerns the implementation of a negative search9 facility in relation to the registration of individual tax payers and the administration of superannuation. A negative search facility provides increased assurance that individuals do not exist in the data sets, thus improving the integrity of the data.

The Tax Office is moving into an environment which is placing a premium on the fully effective use of the data matching and analytics capability. An example of this is the pre-filling initiative. It represents a paradigm shift for the Tax Office's use of data matching and analytics. This is because it is pioneering a shift from bulk post-assessment income data matching to the pre-filling of electronic tax returns with data that would have been used in semi-automated post-assessment data matching.

The longer term success of pre filling depends on the continued assistance by the suppliers of legislated data.10 However, to be fully effective the reporting deadlines for legislated data may have to be brought forward. Also, the Tax Office's use of third party data, necessary for improved administration and achieving a higher integrity tax system, would be improved if legislation enabled attachment of the TFN to the data in a manner similar to the arrangements that apply to legislated data.

The legislative development of the TFN reflects the tension of maintaining an appropriate balance between individual privacy and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of public administration. Given that the determination of where the balance of this tension lies is a matter for the Government and the Parliament, the ANAO has proposed that the Tax Office develop options for legislative amendment for discussion with the Treasury in the first instance.

In light of the Tax Office's stronger data matching and analytics capability, there is scope for its increased exploratory use. There is scope to more efficiently and more quickly identify a range of compliance risks, including those to the tax system's integrity and to the revenue base, thereby improving the Tax Office's understanding of these risks.

Most compliance risks in respect of the majority of taxpayers are addressed, in line with the Compliance Model, by the provision of services such as education, assistance, information, and making compliance easier, cheaper and more personalised. Compliance risks of the most egregious type, which are depicted in the Compliance Model as being towards the top of the compliance pyramid (Fig 3.1 in the report), are considered by the Tax Office as being best addressed by personalised, swift, forceful and, if at all possible, pre-emptive, action.

The implementation of pre-filling, other on-line, web-based services and the ECMP Change Program, provides the Tax Office with the potential to reduce post-assessment processing compliance activity and provide the education, assistance and information services more cost-effectively.

Developments reviewed in this Report have the potential to enable the Tax Office to respond to the challenge of optimising compliance in a way that is more efficient and effective than previously possible. These developments include the continuing roll out of on-line and web-based services supported by the technological innovations of the ECMP Change Program and the data matching and analytics capability.

Key findings by chapter

Chapter 2: Legislative and Policy Framework

Chapter 2 identifies the key features of the legislative framework for the Tax Office's data matching activities, and reviews the Tax Office's adherence to privacy legislation.

External data the Tax Office uses for data matching and analytics (and other activities) is acquired via four main avenues, namely:

- datasets provided by an external party to the Tax Office as a result of specific legislative requirements (e.g. Annual Investment Income Reports provided by financial institutions). These legislated data sets cover major income streams such as salary and wages and interest and dividends, but do not cover other income streams such as capital gains, net rents, and income from self employment;

- datasets provided by a government agency to the Tax Office, under memorandums of understanding (e.g. state revenue offices);

- commercially available datasets purchased by the Tax Office (e.g. electoral roll data); and

- datasets requisitioned by the Tax Office using legislative authority, on a non-routine basis, for data matching and analytics projects (e.g. data is requisitioned from sellers of luxury vehicles to assist in detecting undeclared income and identify other tax risks).

In the past, the Tax Office sometimes used different approaches to decide which of the Commissioner of Taxation's powers were to be used in procuring data. Enhanced consultation with all business lines and the Office of the Chief Knowledge Officer during the project planning stage would assist in ensuring that data is acquired under the appropriate legislative authority, the compliance burden on data providers is minimised, and enable the optimal use of the data by the Tax Office.

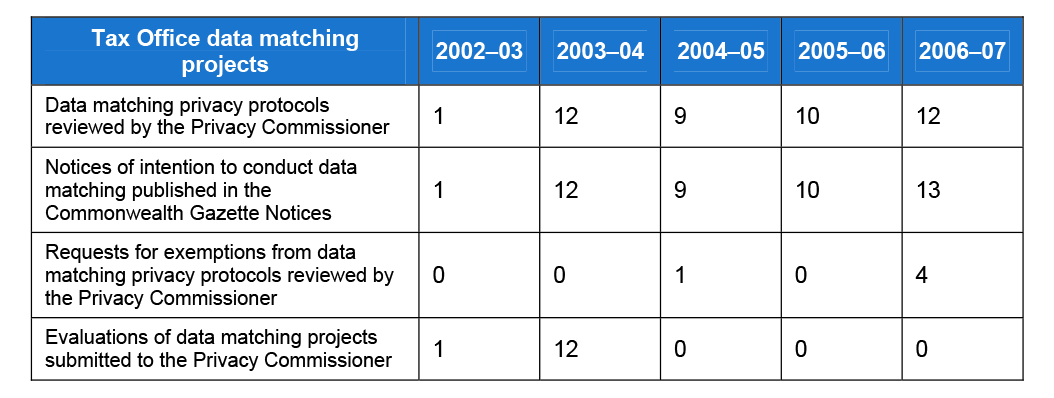

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner has published The Use of Data Matching in Commonwealth Administration – Guidelines (the Guidelines). These contain a number of procedures to ensure data matching activities are designed and conducted in accordance with sound privacy principles. The Tax Office has, as required by the Guidelines, submitted to the Privacy Commissioner Data Matching Program Protocols for its data matching projects, announced its intention to conduct authorised data matching projects through the Commonwealth Gazette, and submitted project evaluations to the Privacy Commissioner. Table 1 provides details of the Tax Office's submissions to the Privacy Commissioner, and announcements in the Commonwealth Gazette since inception of the DMSC in 2003. The ANAO notes that as compliance with the Guidelines is voluntary, the Privacy Commission reviews the Tax Office's submissions, providing the Tax Office with comment, not approval.

Table 1 Tax Office submissions to the Privacy Commissioner, 2003–04 to 2006–07

Source: Tax Office

The Tax Office could broaden the announcement of data matching projects by directly advising tax agents11 of gazetted data matching projects as well as communicating these projects through the Tax Office's marketing and education channels.

A number of recent developments have a bearing on the applicability of the Guidelines to contemporary data matching practices in the Tax Office. These include rapid advances in technology, changing community perceptions, and expansion of data matching activity.

Chapter 3: data matching and analytics capability in the Tax Office

In this report data matching and analytics capability includes a range of computer-based methodologies that have the common feature of bringing together and comparing large volumes of data from different sources. The capability includes all of the computer-based methodologies that the Tax Office applies to:

- make comparisons;

- link data sets;

- compare corresponding items;

- find relationships and patterns; and

- construct descriptive or hypothetical representational and/or functional relationships of variables of which the data is composed.

Whilst there are considerable technical differences between the algorithms which make up the methodologies used, and the particular uses to which the methodologies are put, all the methodologies at the corporate and strategic level have the common feature of bringing together and comparing large volumes of data from different sources.

The Tax Office applies these methodologies for a range of compliance improvement and revenue collection initiatives, to improve services, to better understand compliance risks and behaviour, and to better manage those risks.

Data matching and analytics capability not only consists of these computer-based methodologies but also includes the advanced professional skills of the staff who develop the software and interpret the results generated by the software, and specialised information technology software and hardware.

Data matching and analytics capability is a key competency or resource that the Tax Office has developed, beginning with the traditional computer-based data matching that began several decades ago.13 The capability supports the Tax Office's management of compliance risk having regard to the understanding of compliance behaviour summarised in the Compliance Model. The previous Commissioner of Taxation stated:

It is clear that data matching is an efficient and effective way to help ensure the integrity of our revenue system. For this reason we are continuing to explore ways to improve our data matching capability and to focus data matching exercises on genuine risks to the community's revenue base.14

The Tax Office's data matching and analytics capability extends beyond its traditional notion of data matching (e.g. identity matching, income matching using the ATOms and DMSC facilitated data matching compliance projects) and encompasses the full spectrum of Tax Office data matching and analytics activity. The Tax Office's Compliance Model emphasises that the provision of services to taxpayers is the most appropriate Tax Office response to compliance risks presented by the majority of taxpayers. The ANAO considered there was potential for the ‘provision of services' to be included in the criteria for data matching and analytics projects.

Recent speeches by the Tax Commissioner also take a broad view of the capability:

As our Integrated Core Processing matures, we will be able to develop more refined risk models with wider data warehousing, analytics, and data mining and matching capabilities. These capabilities will mean that we will be able to better differentiate between those taxpayers who are trying to do the right thing and those that are not.15

Legislation sets out that quotation of the Tax File Number (TFN) is voluntary in tax administration, and the use of a unique numeric identifier is not required in most non taxation situations.16 The Tax Office has developed its data matching and analytics capability partly to address this challenge. Nevertheless, partly because of shortcomings in the quality of third party data sets, the Tax Office is sometimes unable to associate a unique identifier to all relevant records and/or to link satisfactorily particular data items in third party data sets to entries in tax returns that should correspond. Additional forensic investigations are sometimes necessary. The ANAO noted these features do not apply in a number of sovereign states that are members of the OECD.

The Tax Office is moving into an environment which will increasingly depend on making better use of the data matching and analytics capability. An example is the pre-filling initiative. The Tax Office began piloting the pre-filling concept using e-tax for 2004–05. This pilot was limited to pre-filling data from Medicare Australia and Centrelink. In 2005–06 the Tax Office expanded its pre-filling pilot to include the 30 per cent childcare rebate, and bank interest and managed fund information from selected financial institutions. The ANAO noted the limited range of fields and data available for pre filling in 2005–06 restricted the relevance of the pre filling pilot facility to a relatively small proportion of e-tax users. In 2006–07, approximately 1.9 million individuals used e-tax to lodge their return, and of these, approximately 1.1 million used pre-filling. A further 1.9 million pre-filled reports for individuals were downloaded by tax agents through the Tax Agent Portal.

Introduction of pre-filling represents a shift for the Tax Office's use of data matching and analytics. It involves, for example:

- advising the taxpayer at the time tax returns are being completed the information the Tax Office holds relevant to the completion of their tax returns;

- a shift from bulk post-assessment income data matching to pre-filling of electronic returns;17 and

- the provision of web-based services that can only be enabled by data matching and analytics using multiple, high integrity data bases.

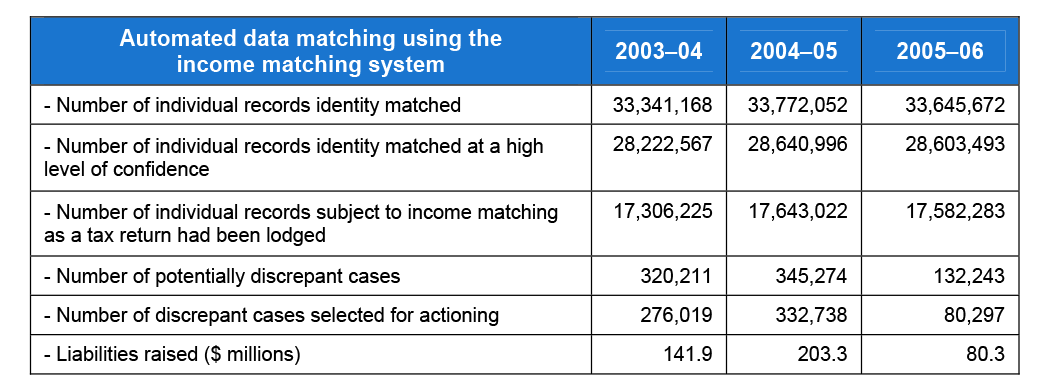

The ANAO reviewed the Tax Office's use of data acquired by different avenues: datasets provided by the Tax Office as a result of legislative requirements; datasets provided by Government agencies under memorandums of understanding; commercially available datasets; and datasets requisitioned by the Tax Office using its legislative authority. The Australian Tax Office's matching system (ATOms) automatically matches data from legislated data sources against data taxpayers provide directly to the Tax Office. ATOms detects discrepancies in stated income, and produces a pool of cases that may be selected for compliance activity. Processing statistics and amounts of additional revenue collected from automated data matching are collated and in some years have been published in the Tax Office's annual compliance program report. Table 2 summarises the Tax Office's automated data matching using ATOms for the last three available financial years (details for 2006–07 are not yet available).

Table 2 Automated data matching using Annual Investment Income Report (AIIR) and Dividend and Interest Schedule data, Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) data (e.g. salary, lump sums, fringe benefits), Centrelink data (e.g. various benefits and allowances, pensions), and Medicare Australia data (e.g. private health insurance premiums, Medicare levy surcharge data)

Notes:

1. The numbers refer to numbers of records, not numbers of individual persons, as individuals can be matched for more than one data type.

2. Processing for 2005–06 has not yet been completed. See additional table notes in the Report.

Source: Tax Office.

Chapter 4: Governance and Coordination Arrangements

The administration of the data matching and analytics capability is necessarily distributed across the Tax Office as the capability is integral to tax administration. The Tax Office established the DMSC to pursue a range of objectives. These include the coordination and facilitation of best corporate results from the data matching component of the capability; supporting other coordination and consultative arrangements; encouraging best practice and intra-business line consultation. These arrangements have generally worked well and the DMSC has been pivotal to results the Tax Office has achieved from the deployment of the capability. In the future, increased coordination between the OCKO's Analytics group and the DMSC would help ensure the two areas proceed jointly and efficiently with respect to strategic planning, prioritisation of projects and community consultation.

The Tax Office's data matching practices are well established. The DMSC has facilitated a more corporate and strategic use of data matching as an integral component of tax administration. This has resulted in improved compliance, increased revenue, improved services and the more efficient and effective use of resources. It has also enabled the Tax Office to better understand risks. The procedural arrangements established by the DMSC have enabled the Tax Office to improve the use of data matching and comply with Privacy Commissioner Guidelines.

The Tax Office would benefit from the consolidation at the corporate level of knowledge of the scope, achievements, lessons learnt and potential of data matching and analytics. It is timely to do this because of the:

- increased incidence of data matching and analytics work over the last five years;

- planned introduction of the ECMP Change Program; and

- demonstrable synergies between data matching and analytics methodologies.

Recommendations

The ANAO made six recommendations directed at improving the Tax Office's corporate and strategic management of its data matching and analytics capability.

Summary of agency response

The Tax Office welcomes the Australian National Audit Office's recommendations in relation to its use of data matching and analytics in tax administration.

Data matching and analytics play a key role in modern tax administration. As the report acknowledges, the Tax Office is recognised as a leader in the area by tax authorities internationally.

The Tax Office accepts the six recommendations.

Developments in technology are allowing the Tax Office to move to increasingly sophisticated approaches in the use of data. The Tax Office will continue to explore opportunities for the increased use of data to improve the operation of the tax system.

It is encouraging to note that the Australian National Audit Office supports the shift the Tax Office is making to use data matching to support a range of service initiatives. As noted in the report, these include the expanded pre-filling initiative and the extended use of third party information (for example, real property data) to assist taxpayers in correctly preparing income tax returns, rather than using this data exclusively to support post issue compliance checks.

Footnotes

1 Australian Taxation Office, Annual Report 2006–07, p. 283.

2 The Compliance Model (see Fig 3.1 of this Report) summarises a considerable body of knowledge about the reasons why people function the way they do in relation to society's institutional arrangements. The Model shows the most cost-effective compliance strategy that the Tax Office should adopt for a particular group of taxpayers. The Model provides a knowledge based framework for determining the most appropriate strategy to take in relation to a compliance problem, given what is known about taxpayers, their situation, circumstances, and lines of business. The Model was first presented in 1998 in the Second Report of the Cash Economy Task Force, Improving Tax Compliance in the Cash Economy; ATO April 1998.

3 In this Report ‘analytics' is a technical term with a precise meaning. ‘Analytics' means a discipline that identifies patterns, relationships and trends from data, using a variety of mathematically based technologies principally drawn from statistics and data mining. Most broadly, analytics covers what might be called basic analytics, including data exploration and aggregation, and advanced analytics, which uses data mining technology for discovery and model building purposes. Using statistical and data mining technologies, significantly more complex relationships within and between entities (e.g. taxpayers) can be discovered and modelled, based on analyses over very large populations of collected data. Analytics is assisted by the use of good data matching and data linking techniques which improve the quality and value of data inputs available to a data miner. Conversely, analytics can also provide technology to assist data matching and data linking activities. See further the Glossary at the end of this Report.

4 Tax Office, External Data Matching PS CM 2004/17.

5 Legislated data refers to data third parties provide to the Tax Office, as a result of specific legislated requirements (e.g. Annual Investment Income Reports (AIIR) provided by financial institutions see Audit Report No.48 2003–04, The Australian Taxation Office's Management and Use of Annual Investment Income Reports). Legislated data sets cover major income streams such as salary and wages and interest and dividends, but do not cover other income streams such as capital gains, net rents, and income from self employment. See Appendix 2, Table A2 for a list of legislated datasets the Tax Office regularly receives, and the legislation under which the data is provided.

6 The investigation of discrepant cases, which is critical to the effectiveness of ATOms relies on an investigatory effort in a way that is similar to some analytics projects. See Audit Report No.48 2003–04, The Australian Taxation Office's Management and Use of Annual Investment Income Reports, Chapter 5.

7 Business lines are the market segment compliance divisions and include Large Business and International, Small Business Enterprises, Micro Enterprises and Individuals, Superannuation, Serious Non Compliance, Debt, Goods and Services Tax and Excise.

8 For example, “As our Integrated Core Processing matures, we will be able to develop more refined risk models with wider data warehousing, analytics, and data mining and matching capabilities. These capabilities will mean that we will be able to better differentiate between those taxpayers who are trying to do the right thing and those that are not; and by integrating data matching work with our risk profiling we are making sure that they are working hand-in-glove. This work happens without the Tax Office contacting people and wasting their time.” And “In the future we will be developing more sophisticated multi-factor data matching, not just using, for example, TFN or name matches. We will match simultaneously across multiple data sources and more attributes, such as birth date and address. This wider range of factors will provide progressively higher degrees of reliability.” Michael D'Ascenzo, Commissioner of Taxation, Simplifying Tax Administration in a Complex World: The Challenge of Infinite Variety, Australian Tax Teachers' Association Conference, University of Queensland 22–24 January 2007.

9 A negative search facility can match and report a ‘No Match' as a success; that is, establish with a specific level of confidence, that the individual does not exist in the data being searched.

10 Legislated data refers to data third parties provide to the Tax Office, as a result of specific legislated requirements (e.g. Annual Investment Income Reports (AIIR) provided by financial institutions see Audit Report No.48 2003–04, The Australian Taxation Office's Management and Use of Annual Investment Income Reports). Legislated data sets cover major income streams such as salary and wages and interest and dividends, but do not cover other income streams such as capital gains, net rents, and income from self employment. See Appendix 2, Table 2 for a list of legislated datasets the Tax Office regularly receives, and the legislation under which the data is provided.

11 Tax agents prepare about 73 per cent of individual, and over 95 per cent of business tax returns.

12 Tax Office executives have been increasingly drawing on the interrelationships and conceptual commonalities of Tax Office data matching and analytics activity.

13 Audit Report No.1 of 1995–96, Income Matching System, reported on the Tax Office's computer based system which identified discrepancies between information in tax returns and external data, noting that the system had been in operation since late 1987.

14 Michael Carmody, Data Matching Improves Compliance, 28 September 2005, <www.ato.gov.au> [accessed 220 February 2007].

15 Michael D'Ascenzo, Simplifying Tax Administration in a Complex World: The Challenge of Infinite Variety, Australasian Tax Teachers Association Conference, University of Queensland, 22–24 January 2007.

16 A taxpayer (that is, a person, company, partnership, trust or superannuation fund) is not compelled to quote their TFN in any of their dealings with the Tax Office. This makes Australia unusual amongst nations with TFN type identifiers. Since 1990 legislation governing the use of the TFN for the receipt of most Commonwealth income support payments has required that people claiming, or receiving, this assistance have to provide a TFN as a condition of receiving such payments. TFN withholding taxes are imposed (subject to several exemptions) for not quoting a TFN for specific financial transactions (such as the interest earned on investment accounts). The TFN withholding tax imposed is at the top marginal tax rate (plus the Medicare levy) and applied to the interest earned above a minimum threshold of $120 per annum for interest earned and to each $1 earned as dividends. The top marginal tax rate (plus the Medicare levy) is imposed on the actual salary and wage income being paid for not quoting the TFN on the Employment Declaration Form regardless of the actual income. For further details see Audit Report No.37 1998-99 Management of Tax File Numbers Australian Taxation Office.

17 Commissioner's online update, May 2005.