Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission’s Administration of the Biometric Identification Services Project

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission’s administration of the Biometric Identification Service project.

Summary

Background

1. On 1 July 2016, the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) was created through the merger of the CrimTrac agency (CrimTrac), the Australian Crime Commission (ACC) and the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC).1 Prior to the merger, CrimTrac had commenced planning and initial administration of the Biometric Identification Services project (the BIS project or BIS).

2. BIS was a $52 million project with two key goals:

- replacement of the existing National Automated Fingerprint Identification System (NAFIS)2; and

- addition of a facial recognition capability to enhance law enforcement’s biometric capabilities.

3. A Biometric Identification Solution Contract was signed on 20 April 2016 between NEC Australia (NEC) and CrimTrac, just prior to ACIC’s creation.

4. The BIS project encountered difficulties at an early stage. Despite intervention by the executive of ACIC and ultimately unsuccessful negotiations between ACIC and NEC, the ACIC CEO announced on 15 June 2018 that the project had been terminated.

5. When it became apparent that BIS would not be completed prior to the expiry in May 2017 of ACIC’s contract with Morpho, the company that operated NAFIS, ACIC extended its contract with Morpho (for a substantially higher price). The NAFIS contract is now due to expire in May 2020. ACIC has yet to decide the future of NAFIS.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

- The audit was requested by ACIC’s Acting Chief Operating Officer on behalf of ACIC on 14 February 2018; and

- the BIS (and the system it was to replace, NAFIS) are critical enabling systems for Commonwealth and state law enforcement. A threat to the availability of this capability would be of significant concern to the Australian Government.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of ACIC’s administration of the BIS project.

7. The audit criteria were:

- Was the procurement process for the BIS project conducted in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules?; and

- Has ACIC effectively managed the BIS project to achieve agreed outcomes?

Conclusion

8. While CrimTrac’s management of the BIS procurement process was largely effective, the subsequent administration of the BIS project by CrimTrac and ACIC was deficient in almost every significant respect. The total expenditure on the project was $34 million. None of the project’s milestones or deliverables were met.

9. The procurement was designed and planned consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and ICT Investment Approval requirements and the tender assessment process supported value for money. However, two critical requirements were overlooked in the requirements gathering phase and the approach to negotiating and entering the contract did not effectively support achievement of outcomes. This was a result of the contract not explaining the milestones and performance requirements in a manner that was readily understood and applied.

10. ACIC did not effectively manage the BIS project with its approach characterised by: poor risk management; not following at any point the mandated process in the contract for assessing progress against milestones and linking their achievement to payments; reporting arrangements not driving action; non adherence to a detailed implementation plan; and inadequate financial management, including being unable to definitively advise how much they had spent on the project.

Supporting findings

The tender process

11. The BIS procurement was largely effective. CrimTrac designed and planned the procurement consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and ICT Investment Approval requirements. Requirements were developed in conjunction with state and territory police, although two critical requirements were overlooked.

12. CrimTrac’s approach to market supported a value for money outcome. The approach to market had sufficient reach and two valid tenders were received.

13. The tender assessment process supported value for money. It was transparent and consistent with planning documents and the Commonwealth Procurement Rules in that:

- there was appropriate weighting of selection criteria;

- internal and external probity advisers oversaw all phases of evaluation; and

- the Tender Evaluation Committee report to the delegate was comprehensive.

14. The approach to negotiating and entering the contract did not effectively support achievement of outcomes because the contract did not explain the milestones and performance requirements in a manner that was readily understood and applied.

Management of the project

15. The governance framework for BIS was not effective.

- Risk registers established for the project were not used effectively.

- External reviews in June and November 2017 identified the absence of a robust governance structure.

- ACIC’s Audit Committee was not informed of the status of the project.

16. Contract management was not effective.

- The stipulated contract process by which progress against milestones and deliverables was to be assessed was not followed at any stage and ACIC thus had no way of assuring itself that it got what it paid for.

- ACIC agreed to more than $12 million in additional work. Documentation showed that some of this work may have been unnecessary and other work may have already been covered under the contract.

- ACIC ‘inherited’ the former CrimTrac and ACC Electronic Document and Records Management Systems (EDRMS), leading to duplication and ineffective record keeping. Further, many staff did not use any EDRMS, instead keeping records on their own computers, in uncurated network drives or in email inboxes.

- While a Benefits Management Framework was developed and evidence showed that a benefits realisation and documentation process was intended, it was not implemented.

- An internal audit report had found that ACIC did not have an effective contractor management framework.

17. ACIC established appropriate arrangements for reporting to stakeholders. However these were not fully effective because they did not result in sufficient action being taken and the external stakeholders felt that reporting dropped off over time.

18. The contract provided an implementation plan including Solution Delivery and Solution Design, with more detail for Solution Delivery.

- The agreed schedule was not adhered to and was repeatedly extended before BIS was terminated in June 2018.

- In order to maintain the uninterrupted availability of a national fingerprint capability for law enforcement, ACIC was obliged to renegotiate the existing NAFIS contract at a significantly increased cost.

19. Financial management of the BIS project was poor. ACIC’s corporate finance area had no responsibility for management of the financial aspects of the BIS project; neither did the project team have a dedicated financial or contract manager. ACIC was unable to advise definitively how much they had spent on the project.

20. ACIC made a ‘goodwill’ payment of $2.9 million to NEC which was not linked to the achievement of any contract milestone. ACIC was not able to provide details of how the quantum of this payment was calculated.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed report was provided to ACIC. A summary of its response is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) found the Australian National Audit Office’s audit of its Biometric Identification Services Project to be thorough and comprehensive. It has revealed significant failures in the management and delivery of the project, and has identified opportunities for the ACIC to refine its practices in order to improve its delivery of information and intelligence services to law enforcement and national security agencies in Australia.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

22. The findings from this audit provide a range of learnings for other government departments managing technical bespoke procurement, which contains inherent risks due to its complexity or untested suitability.

Governance and risk management

Contract management

Records management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The fact that every person’s fingerprints are unique was first recognised in the mid-19th century. Fingerprints and palm impressions are a fundamental law enforcement tool, enabling police to establish identity, collect evidence and solve crimes.

1.2 In the late 1980s, Australia became the first country to establish a National Automated Fingerprint Identification System (NAFIS).3 Individual police agencies4 also committed to a further national common police service known as the National Exchange of Police Information.

1.3 CrimTrac was established through an Inter-Governmental Agreement (IGA) in 2000 to enhance policing through the provision of information services. The Commonwealth Minister for Justice and state and territory Police Ministers, on behalf of their respective governments, signed the IGA on 13 July 2000.

1.4 CrimTrac received one-off government funding of $50 million to develop four national crime fighting systems5, including a ‘new’ NAFIS.6,7 CrimTrac’s ongoing operating costs were met from revenue collected from the provision of checking services such as NAFIS and police record checks and CrimTrac did not receive any budget funding.8

1.5 The Australian Crime Commission (ACC) was established in 2002 to collect intelligence to improve the national ability to respond to crime impacting Australia.9 As with CrimTrac, the ACC worked closely with state and territory law enforcement agencies. Both the CrimTrac and the ACC boards included state and territory police commissioners.

1.6 In October 2013, the government established a National Commission of Audit to ‘review and report on the performance, functions and roles of the Commonwealth Government’. Among the 86 recommendations in its February 2014 report, the National Commission of Audit recommended that CrimTrac be merged with the Australian Crime Commission ‘to better harness their collective resources’. The National Commission of Audit report noted that implementation of its recommendation would require consultation with the states.

1.7 In December 2014, consultation commenced between the Commonwealth minister and state and territory counterparts on options for the merger. Ensuing negotiations culminated in a package of legislation that would allow the merged agency to continue the funding model that supported CrimTrac services for over a decade, at no cost to the Commonwealth budget.

1.8 In 2015, the government introduced the Australian Crime Commission Amendment (National Policing Information) Bill to give effect to the merger of CrimTrac and the Australian Crime Commission. The merged agency was called the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC).10,11 In evidence at Senate Estimates in May 2015, the inaugural Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of ACIC, Mr Chris Dawson APM, said:

The Crime Commission’s role is in the intelligence space and in the analytical space. CrimTrac’s role is in the data being drawn in from each of the police jurisdictions. That data does not have an analytical interface over it, and that is what is required in terms of CrimTrac information systems interfacing much more readily with the Australian Crime Commission’s analytics.

1.9 The CrimTrac special account continued after the merger, with its purpose unchanged. At 30 June 2015, the balance of the special account was around $120 million. ACIC formally came into existence on 1 July 2016. It had approximately 830 staff: 220 from the former CrimTrac and 610 from the former ACC.

1.10 The ACIC Board represents Commonwealth, state and territory law enforcement and key regulatory and national security agencies. The Board is chaired by the Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police. The membership of the Board is shown at Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission board at 30 June 2018

|

Board members |

|

Commissioner, Australian Federal Police (Chair) |

|

Secretary, Department of Home Affairs |

|

Comptroller-General of Customs (Commissioner of the Australian Border Force) |

|

Chairperson, Australian Securities and Investments Commission |

|

Director-General of Security, Australian Security Intelligence Organisation |

|

Commissioner, Australian Taxation Office |

|

All state and territory Commissioners of Police |

|

Chief Executive Officer, ACIC (non-voting member) |

Note a: The Chief Executive Officer of AUSTRAC and the Secretary of the Attorney-General’s Department are non-voting observers.

Source: ACIC 2017–18 Annual Report.

1.11 Under the functions in section 7C of the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002, the Board is responsible for determining the national criminal intelligence priorities, providing strategic direction to the ACIC, and authorising the use of the ACIC’s special coercive powers12 through special intelligence operations13 and investigations.

1.12 The contract between CrimTrac and Morpho for NAFIS was due to expire in May 2017, following CrimTrac’s exercise of two one-year options to extend it. At the time, CrimTrac had experienced increased demand for NAFIS among police agencies and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.14 The increased demand also led CrimTrac to undertake a capacity upgrade of NAFIS from July 2013 until July 2015.

1.13 The Biometric Identification Services (BIS) project was a project that CrimTrac intended would deliver a national fingerprint and palm print capability, a facial biometric capability and the ability to match identity using both capabilities. As originally conceived,15 BIS would begin operating in May 2016, twelve months before the expiry of the NAFIS contract. The approved budget for the project was $52 million, with $28.9 funded from the special account and the balance ($23.1 million) funded from CrimTrac’s own existing resources.

1.14 NAFIS would continue to operate while BIS was designed, built and implemented to ensure that the critical national fingerprint capability continued uninterrupted. However, procurement for the BIS project culminated in a contract with NEC that was agreed and signed by both parties on 20 April 2016. By that time, timeframes were already tight. The contract provided for 17 milestones, with the facial recognition component occurring after implementation of the fingerprint component.

1.15 The BIS project encountered substantial difficulties. In order to attempt to resolve those difficulties, ACIC suspended the project on 4 June 2018 with NEC by mutual agreement.

1.16 In a media statement released on 15 June 2018, ACIC’s CEO announced that the BIS project had been terminated in light of project delays. In contrast, a media statement by NEC (also on 15 June 2018), stated that ‘the BIS Solution was ready to be handed over to ACIC for System Acceptance Testing when the project was placed on hold by ACIC.’16

1.17 In April 2018, prior to the cancellation of BIS, the ACIC extended the existing NAFIS contract with Morpho (which was renamed Idemia in May 2017) for a further year (to May 2019), with an option to extend it for a further year.

Audit approach

1.18 On 14 February 2018, ACIC’s Acting Chief Operating Officer wrote on behalf of the ACIC CEO requesting that the ANAO undertake a performance audit of the BIS project.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of ACIC’s administration of the BIS project.

1.20 The audit criteria were:

- Was the procurement process for the BIS project conducted in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules?; and

- Has ACIC effectively managed the BIS project to achieve agreed outcomes?

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit methodology involved:

- Examination of relevant entity records.

- Discussions with relevant staff.

- Discussions with BIS stakeholders, including state and territory police forces and the Australian Federal Police.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of about $353,000. The team members for this audit were Julian Mallett, Natalie Maras and Michael White.

2. The BIS procurement process

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the procurement process for the BIS project was conducted in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Conclusion and findings

The procurement was designed and planned consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and ICT Investment Approval requirements although two critical requirements were overlooked in the requirements gathering phase.

CrimTrac’s approach to market supported a value for money outcome. The approach to market had sufficient reach and two valid tenders were received.

The tender assessment process supported value for money by treating all tenderers equitably, adopting appropriate weighting of selection criteria, ensuring appropriate probity arrangements were in place and providing sufficient information to the delegate to make an informed assessment.

The approach to negotiating and entering the contract did not effectively support achievement of outcomes because the contract did not explain the milestones and performance requirements in a manner that was readily understood and applied.

The Commonwealth procurement process

2.1 Procurement by Commonwealth entities is governed by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). Pursuant to subsection 105B(1) of the PGPA Act, the Minister for Finance has issued Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) which set out mandatory rules with which Commonwealth entities must comply when planning a procurement, including calling for tenders. The guiding principle of the CPRs is to achieve value for money.

2.2 Additional requirements apply to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) procurements. Under the ICT Investment Approval ‘two pass’ process, entities seeking to make significant ICT investments are required to prepare a first pass business case for consideration by government as part of its budget deliberations for that year. Where the government approves the first pass business case, the entity prepares a second, more detailed, business case for government consideration. The process is designed to seek government agreement prior to an investment decision, which in some cases may involve the expenditure of many millions of dollars.

2.3 Separate from the ‘two pass’ process, if entities bring forward a high risk new policy proposal17 with a project cost of $30 million or more, which includes an ICT component of at least $10 million, the Department of Finance may recommend to government that the proposal be subject to the Gateway Review Process. The Gateway Review Process comprises a series of short intensive reviews at critical points across a proposal’s implementation lifecycle. Such reviews are conducted by an independent Assurance Review Team appointed by the Department of Finance in consultation with the entity involved. Gateway is not an audit process and does not replace an entity’s responsibility and accountability for implementing decisions and projects.

Was the procurement designed and planned in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and ICT Investment Approval requirements?

The BIS procurement was largely effective. CrimTrac designed and planned the procurement consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and ICT Investment Approval requirements. Requirements were developed in conjunction with state and territory police, although two critical requirements were overlooked.

2.4 Planning for BIS commenced in 2013. At the time, the Minister for Justice had Commonwealth responsibility for CrimTrac and provided guidance on strategic priorities. Under the IGA (see paragraph 1.3) CrimTrac’s Board of Management had responsibilities including approving and monitoring evolving business cases.

2.5 For the procurement of BIS, the relevant frameworks included:

- the Commonwealth Procurement Rules July 201418;

- the ICT Two Pass Review process; and

- internal CrimTrac Procurement and Contracting Guidance and Accountable Authority Instructions 2014.

2.6 As noted in paragraph 2.3, the Department of Finance may recommend to government that a proposal be subject to the Gateway Review Process. Although the total estimated cost of the BIS project (over $52 million) met the financial threshold (over $30 million) for the Department of Finance to recommend Gateway Review of the BIS proposal, the Department did not appoint independent reviewers for BIS.19

Establishing the business need

2.7 A principal motivating factor for the BIS project was the expiry of the NAFIS contract with Morpho in May 2017. By that date, both options to extend the contract would have been exercised.

2.8 By 2014, technological advancements had increased the ability of police investigators to identify people through other biometric ‘modalities’ such as facial images, scars, marks and tattoos as well as fingerprints. CrimTrac considered these advancements provided an opportunity to provide improved biometric capabilities to police partner agencies. CrimTrac commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to assess the market, which confirmed that the Australian biometrics market was sufficiently mature to deliver a biometric identification service capability, with four major vendors having capacity and ability to do so. PwC also advised that at that time, biometric technology for scars, marks and tattoos was not yet worth pursuing.

First and second pass business cases

2.9 In October 2014, CrimTrac submitted the BIS new policy proposal to the Department of Finance as required and BIS was included in the Attorney-General’s Budget Submission for 2015–16. The Expense Measures reflected government agreement to provide $0.7 million in 2015–16 for CrimTrac to finalise the development of the BIS business case (based on CrimTrac’s estimate of the cost of the process) although ACIC advised in October 2018 that the cost of the business cases was actually $2.265 million.

2.10 CrimTrac completed a first pass business case in November 2014, which considered stakeholder input, the scale and scope of the business requirement, and the market’s capacity to respond to a procurement. This business case detailed the benefits, costs and risks of three viable options, all of which were consistent with the objectives of the CrimTrac special account and the IGA.

2.11 The CrimTrac Board of Management agreed with the first pass business case and approved it one week after it was submitted to the Department of Finance.20

2.12 In February 2015, CrimTrac’s Strategic Issues Group21 noted that there could be a range of issues with facial recognition such as integration with state systems and system interfaces.

2.13 During March and April 2015, before CrimTrac released the Request for Tender (RFT) to market, it engaged PwC to assist in gathering, defining and developing requirements. This process involved meeting with fingerprint subject matter experts in all of the state and territory police forces to ensure that the design of BIS would meet their individual needs.22 Whereas industry experience for requirements development indicates months or years for complex IT projects23, CrimTrac and PwC completed requirements development with police for both BIS fingerprint and facial biometric solutions within weeks.

2.14 CrimTrac completed the second pass business case in December 2015. Although this business case provided some of the expected material, it did not closely follow the required structure of the template and did not fully meet standard requirements of the ICT Two Pass Review process. Specifically, the second pass business case lacked an options analysis (although it repeated options from the first pass business case); and assumed that Gateway reviews were not necessary due to the monetary value of the contract being under $50 million.

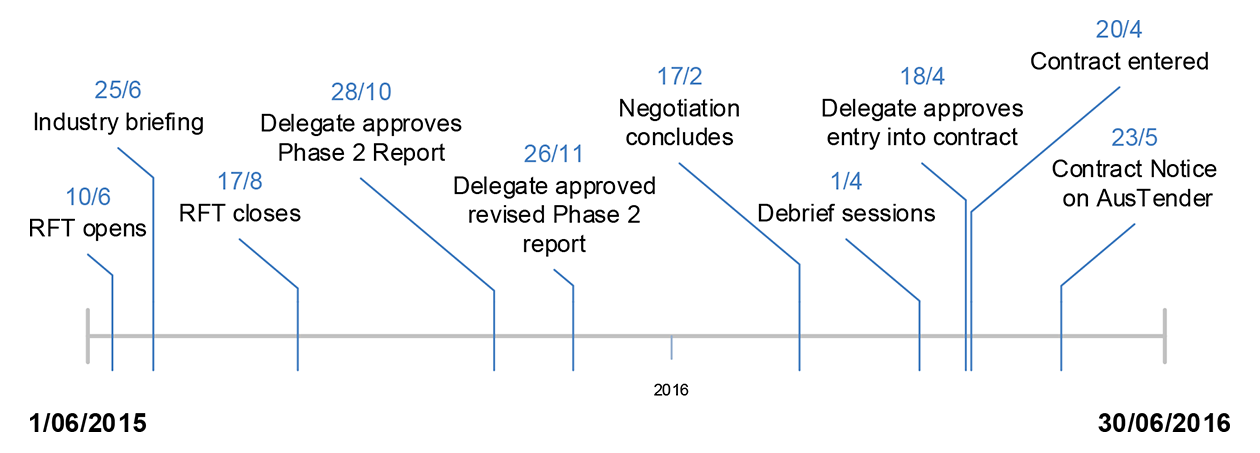

Figure 2.1: Timeline of business cases and approvals

Source: ANAO.

2.15 In December 2015, the Department of Finance provided CrimTrac with its Costing Agreement24 which showed that of a proposed budget of $52.0 million, CrimTrac would fund $28.931 million from the CrimTrac special account. At the time, sufficient funds (approximately $120 million) were available in the account.

2.16 The relevant Estimates Memorandum25 makes it clear that Second Pass approval is required to enable an informed decision by government on the investment before the proposed investment proceeds, otherwise there is a risk that invested resources lack sufficient measures to ensure successful implementation. By the time that the Prime Minister approved the development of the BIS on 24 March 2016, CrimTrac had already:

- issued the tender (on 10 June 2015);

- evaluated responses to the tender;

- selected the preferred tenderer; and

- completed contract negotiations (in February 2016).

2.17 All that remained was contract signature with the successful tenderer, which occurred on 20 April 2016.

Design and planning of the tender

Requirements gathering

2.18 The ANAO found evidence that two important requirements were overlooked in the requirements development phase, relating to assumed identities (AI) and witness security (known as WitSec).

2.19 Assumed identities are ‘invented’ identities given to police and intelligence officers (with official approval26) to allow them to operate ‘under cover’. Witnesses who have agreed to give evidence in the prosecution of serious crimes may be provided with police protection under the National Witness Protection Program. In both cases, it is critical to such people’s safety (and potentially their lives) that information (especially facial images) which might reveal either their true identity or their location, are closely protected and not compromised.

2.20 On 9 February 2018, the ACIC CEO advised the ACIC Board that the additional cost of the necessary work to have AI and WitSec included in the contract would be ‘approximately $10 million’.

2.21 In May 2018 (more than two years after the project commenced), various ACIC officers recognised that AI and WitSec were never adequately captured in the contract.

2.22 The ANAO sought ACIC’s explanation of the omission of AI and Witsec from the requirements gathering phase and the contract. In August 2018, ACIC confirmed that the lack of specific AI requirements in the contract was an oversight.

2.23 Other items were also overlooked. An internal email, dated 1 May 2018, said:

AI was not the only requirement overlooked by PwC’s requirements gathering exercise in the very beginning. It appears that the BIS project never asked for, nor were provided a UI [user interface] spec[ification]. Consequently there are, at last count, 15 data elements missing from the BIS tenprint browse screens that currently appear in NAFIS. Some of these are business critical. These will be highlighted, however without documented requirements, we have no mechanism to effect change. It will be interesting to see how this shakes out.

2.24 Neither of these omissions was corrected before BIS was terminated in June 2018.

Tender evaluation planning

2.25 CrimTrac prepared for tender evaluation by creating a Tender Evaluation Plan, which outlined the assessment process, including tender criteria.

Table 2.1: Planned weighting and streams

|

Item |

Evaluation criteria |

Weighting |

Stream |

|

1 |

Technical capability |

30% |

Solution |

|

2 |

Delivery capability |

25% |

Solution |

|

3 |

Implementation capability |

25% |

Business |

|

4 |

Service Level and reporting capability |

10% |

Business |

|

5 |

Tenderer’s experience, expertise and value added services |

10% |

Business |

|

6 |

Tenderer’s Pricing |

Unweighted |

Finance |

|

7 |

Risk (including, without limitation, the extent to which the Tenderer complies with the Draft Contract). |

Unweighted |

All |

Source: CrimTrac Tender Evaluation Plan.

2.26 The BIS RFT Evaluation Plan also outlined the Evaluation Governance Structure. The evaluation process involved three ‘Solution Streams’ as well as Financial, Legal and Business Streams, each responsible for assessing the components of each tender, preparing a report and submitting it to the Evaluation Chair. CrimTrac co-opted technical experts from state policing to assess technical aspects of proposed solutions. CrimTrac also appointed an external probity advisor for the BIS RFT process.

Figure 2.2: Biometric Identification Services evaluation governance structure

Source: CrimTrac BIS Evaluation Plan.

2.27 The CEO, Chief Information Officer (CIO), Director Legal and Procurement, Project Director and Evaluation Chair approved the BIS RFT Evaluation Plan on 17 August 2015. This was more than a month after CrimTrac published the RFT on 10 June. While not ideal, the late approval of the Tender Evaluation Plan did occur in time for assessment to follow the approved process.

Did the approach to market support a value for money outcome?

CrimTrac’s approach to market supported a value for money outcome. The approach to market had sufficient reach and two valid tenders were received.

2.28 CrimTrac published the RFT on AusTender on 10 June 2015. The BIS RFT had good ‘reach’ because numerous information technology magazines and media outlets picked up the AusTender Notice, further advertising it. CrimTrac records showed interactions with more than 200 entities that registered with CrimTrac to receive tender information.

2.29 The final RFT comprised 16 separate documents, including the overarching RFT documents, a conceptual solution architecture model, and a sample contract. It also included details of how and when CrimTrac would assess tenders and explained weightings for each criterion. In this respect, the process met the CPR requirements.

2.30 The RFT required a successful tenderer to deliver both systems and services to CrimTrac (that is design, build, implement and operate). The RFT invited responses from potential service providers to provide a solution for:

- a national capability for identification using the Biometric Mode of Fingerprint (including Palm Print and Foot Print);

- a national capability for identification using the Biometric Mode of Facial Recognition (FR); and;

- the fusion of available Biometric Data and the capability for expansion into the future to add additional Biometric Modes over time.

2.31 All tenderers were required to respond to each option. The RFT stated that it would assess all three options and select the option or combination of options ‘appropriate for inclusion in any resultant contract’.

2.32 The RFT expressly stated that CrimTrac preferred ‘a product where specific customisations are minimised (for example COTS27 where possible)’. While it is often appropriate for entities to encourage the market to design innovative solutions, such an approach carries greater risk than situations where system and technical design is more clearly defined.

2.33 In accordance with good practice, CrimTrac held an industry briefing session on 25 June 2015 while the tender was open. The market interest in the RFT was evident in attendance by 22 companies.

2.34 During the approach to market process, CrimTrac issued four addenda28 on AusTender to correct typographical errors in the RFT and answer 41 tenderer questions. All tenderers who registered to receive updates had access to these questions and answers, which supports openness and transparency. The original closing date of the RFT (6 August 2015) was extended by addendum to 17 August 2015 following requests for extension from five tenderers.

Did the tender assessment process support value for money?

The tender assessment process supported value for money. It was transparent and consistent with planning documents and the Commonwealth Procurement Rules in that:

- there was appropriate weighting of selection criteria;

- internal and external probity advisers oversaw all phases of evaluation; and

- the Tender Evaluation Committee report to the delegate was comprehensive.

Tender evaluation

2.35 Although 12 responses to the RFT were received, only two tenderers responded to the RFT with compliant responses. One of these was Morpho, the incumbent supplier of NAFIS. The other was NEC.

2.36 Adequate time to prepare a response to the RFT was an issue for four potential tenderers, including the incumbent. One vendor noted that ‘such procurements occur once every 12 to 15 years’ and took time to prepare a response. Although CrimTrac extended the deadline by 11 days, this was (at least) a week less than what half the actively interested vendors requested. Three out of four of the vendors that requested an extension ultimately did not submit a tender.

Figure 2.3: Timeline of Biometric Identification Services tender

Source: ANAO from ACIC documentation.

2.37 At the time that CrimTrac approached the market, there were other biometric projects underway. These included the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Smart Gates for airports; the Attorney-General’s Department’s National Facial Biometric Matching Capability; and the Australian Taxation Office’s biometrics authentication service for mobile app.

2.38 CrimTrac’s first pass business case indicated that CrimTrac was aware of these initiatives. Discussion with ACIC staff showed that vendors were possibly attracted to those bigger contracts. Large integrators might also have been put off the RFT contract because they would have needed to supplement their expertise with support from specialist biometrics vendors like Morpho, NEC and 3M.29

2.39 After the tender closed, it would have been open to CrimTrac to question whether it could achieve value for money through competition between two vendors. While a longer extension might have expanded the field of competitive tenders, there is no record of such deliberation and the RFT process continued with two vendors.

2.40 CrimTrac implemented the Tender Evaluation Plan, carrying out assessment in three phases. In Phase 1, the Evaluation Chair checked that tenders conformed to the conditions for participation. The CEO approved the results of this Phase. In Phase 2, detailed evaluation took place and the Evaluation Chair received solution reports, the financial report and the business report. The tender evaluation team prepared a Phase 2 Evaluation Report for distribution to the Tender Evaluation Committee (TEC). The delegate approved this report on 28 October 2015. The delegate approved a further evaluation update (that revised the RFT shortlist to exclude all but one tenderer, NEC) on 26 November 2015.

2.41 The tender assessment process included reference checks and legal compliance checks. Officials recognised and dealt with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest by maintaining records on the BIS Probity Register. CrimTrac quickly and efficiently dealt with a complaint from one of the tenderers. The external probity adviser confirmed in writing that all three phases of the assessment met probity requirements.

2.42 In March 2016, the Evaluation Chair presented the delegate with a minute containing the Phase 3 Evaluation Report and a clear recommendation. The minute also contained TEC sign-off; a letter from the preferred tenderer regarding the performance guarantee; and probity sign-off. Together, these documents summarised the outcome of the tender evaluation and provided the delegate with assurance that the tender had passed through the planned process and passed probity. The minute did not contain a draft contract, noting that once finalised, the contract would be provided separately.

2.43 After the delegate approved the TEC’s recommendation, CrimTrac informed NEC that it was the preferred tenderer, subject to successful negotiation of a contract. CrimTrac also debriefed the unsuccessful tenderer as required.

Did the approach to negotiating and entering the contract effectively support achievement of outcomes sought?

The approach to negotiating and entering the contract did not effectively support achievement of outcomes because the contract did not explain the milestones and performance requirements in a manner that was readily understood and applied.

Contract negotiation and execution

2.44 CrimTrac had prepared for the contract negotiation phase and produced a BIS Negotiation Directive on 7 December 2015. The directive outlined roles and responsibilities of the negotiation team, which comprised five people, supported by subject matter experts as required.

2.45 CrimTrac’s analysis of NEC’s proposal (in Phase 2) revealed 68 issues requiring clarification with NEC. CrimTrac recognised that this was a high number that could make it difficult to negotiate a contract with NEC. By Phase 3, CrimTrac reduced the list to 32 issues.

2.46 Whilst the BIS Negotiation Directive contemplated that CrimTrac would hold negotiation sessions over a two-week period, negotiations actually concluded after two months on 17 February 2016. This was partly due to availability of personnel over Christmas/ New Year. This was also due to NEC not initially proposing specific alternative drafting to the proposed contract terms.

2.47 Major issues identified for negotiation of contract terms included the pricing schedule, solution requirements, performance requirements, solution design phase and implementation requirements.

2.48 The ANAO’s examination of the records of the negotiation process indicated that CrimTrac and NEC had not resolved every issue by the time authorised officers signed the contract. In addition, the contract did not reflect every agreed negotiation issue. Outstanding items related to acceptance certificate payment, remote access, hardware milestones, and security clearances for personnel.

2.49 The contract was finalised and signed by NEC and CrimTrac on 20 April 2016.

The Biometric Identification Services contract

2.50 The contract entered by CrimTrac and NEC comprised more than 800 pages. The contract was for NEC to design, implement, integrate, support and maintain an integrated biometric system. NEC was to complete the Solution Design by 30 June 2016 and all contract requirements by 20 October 2017. The ‘support and maintain’ phase would continue to 30 November 2022.

2.51 The contract was divided into two phases: the Solution Design Phase and the Solution Implementation Phase. Within each phase, there were milestones, each with a specific completion date. The completion dates for individual milestones were not accompanied by a description of specific documents, activities, or tests needed for each milestone. The completion dates for milestones were not accompanied by specific standards. In many instances, work was to be completed ‘to the satisfaction’ of ACIC, which introduced an element of subjectivity in assessing when the milestone was complete. Table 2.2 shows the summary of milestones to which NEC originally agreed to work.

2.52 The structure of the contract as ‘design and build’ meant that achievement of the design phase was clearly critical: without an agreed design, later phases could not be completed. It also meant that any slippage in the achievement of the first milestone, Solution Design, would inevitably have knock-on effects for achievement of all later milestones.

Table 2.2: Biometric Identification Services contract milestones

|

NEC Contract Milestone |

Completion date |

|

1 Solution Design |

30 June 2016 |

|

2a Fingerprint Data Initial Load |

6 December 2016 |

|

2b Fingerprint data transition and parallel processing |

30 May 2017 |

|

2c Facial Data load |

30 June 2017 |

|

3a Fingerprint Functionality Part 1 Build |

5 October 2016 |

|

3b Fingerprint Functionality Part 2 Build |

30 November 2016 |

|

3c Fingerprint Part 1 deployment — First Stakeholder cutover |

8 December 2016 |

|

3d Fingerprint Part 1 deployment — Production cutover |

27 February 2017 |

|

3e Fingerprint deployment Part 2 |

30 May 2017 |

|

3f Fingerprint Part 1 90 days successful operation |

1 June 2017 |

|

4a Facial Recognition Part 1 Build |

23 March 2017 |

|

4b Facial Recognition Part 1 Deployment — First Stakeholder Cutover |

19 April 2017 |

|

4c Facial Recognition Part 1 deployment Production Cutover |

30 June 2017 |

|

4d Facial Recognition Build and Deployment Part 21 |

31 July 2017 |

|

4e Facial Recognition Build and Deployment Part 3 |

15 September 2017 |

|

4f Facial Recognition Part 90 Days Successful Operation (Part 1 and 2) |

31 October 2017 |

|

5 Fusion of Fingerprint and Face functionality |

20 November 2017 |

Note: The Solution Design Phase comprised only milestone 1. The Solution Implementation Phase comprised the remaining milestones.

Source: BIS Contract.

2.53 The parties agreed on three review dates. These were specified in the contract as the end of Phase 1 Solution Design Phase on 30 June 2016; the end of the Solution Implementation phase on 20 November 2017; and during the support and maintenance phase, annually on the contract anniversary.

2.54 In April 2016, CrimTrac created a contract summary for use in communicating about the contract with a variety of audiences. However, it did not finalise a Contract Management Plan until seven months later, in November 2016. The Contract Management Plan mentioned creation of a contract deliverables register shortly after contract signing that CrimTrac intended to use to track all contract events and deliverables. The Deliverables Register was supposed to be ‘the official tool for contract compliance reporting’ but was not used.

2.55 The contract provided for milestone payments in percentages, rather than fixed sums. To understand milestone payments and deliverables for solution implementation, personnel had to examine the contract, payment tables and schedules. In discussions with the ANAO, ACIC staff described their difficulty understanding how the milestone payments and deliverables worked in practice.

3. Management of the Biometric Identification Services project

Areas examined

The ANAO examined ACIC’s management of the BIS project from the signing of the contract in April 2016 until the cancellation of the project in June 2018.

Conclusion and findings

ACIC did not establish effective governance arrangements for the project. Risk management for BIS was ineffective: while risk registers were developed, there was little evidence that they were used or that risk was effectively reported against. The Audit Committee was not informed of the project’s difficulties.

ACIC did not effectively manage the contract. The mandated process in the contract for assessing progress against milestones and linking their achievement to payments was not followed at any point.

ACIC established appropriate arrangements for reporting to stakeholders. However these were not fully effective because they did not result in sufficient action being taken and the external stakeholders felt that reporting dropped off over time. Numerous reports identified the project’s ‘red’ status from an early stage but little meaningful action was taken until too late.

While a detailed implementation plan was developed, ACIC did not adhere to it to ensure delivery of specified outcomes, milestones and deliverables.

Financial management of the BIS project was poor. ACIC’s corporate finance area had no responsibility for management of the financial aspects of the BIS project; neither did the project team have a dedicated financial or contract manager. ACIC was unable to definitively advise how much they had spent on the project.

3.1 Creation of ACIC in July 2016 involved:

- new delegations, Accountable Authority Instructions and other key corporate documents (such as a new Corporate Plan);

- new governance arrangements for ACIC, its Board of Management and the BIS project;

- changes to senior management committee structures and composition; and

- administrative changes (personnel, payroll, security checks).

3.2 The new, larger, entity also moved to new premises.

3.3 By 1 July 2016, while managers were attending to merger activities, NEC was due to have completed the first solution design phase and was also due to have commenced progressing the second milestone, as this was due in December 2016. Figure 3.1 shows ACIC’s organisational structure immediately after the merger.

Figure 3.1: ACIC organisational structure at 1 July 2016

Source: ACIC.

Was an effective governance framework established for the Biometric Identification Services project?

The governance framework for BIS was not effective.

- Risk registers established for the project were not used effectively.

- External reviews in June and November 2017 identified the absence of a robust governance structure.

- ACIC’s Audit Committee was not informed of the status of the project.

3.4 The ANAO observed that between April 2016 (when the contract was signed) and June 2018 (when the contract was terminated), ACIC experienced a high degree of change at the Senior Executive Service (SES) level of the organisation. Specifically, including both substantive and acting occupants, ACIC had:

- three Chief Executive Officers30;

- four Chief Operating Officers;

- three Chief Technology Officers; and

- five National Managers of ICT Future Capability.31

3.5 The governance framework for BIS was largely the same as that outlined in the business case for CrimTrac. As noted at paragraph 2.49, the BIS contract was signed in April 2016, which was around two months before ACIC came into existence. Figure 3.2 shows the governance framework that ACIC continued for BIS after the merger.

Figure 3.2: ACIC governance framework for the Biometric Identification Services project at 1 July 2016

Source: ACIC Project Governance Model.

3.6 During the course of the audit, the ANAO identified numerous different governance arrangements. These are listed in Table 3.1 and vary from the initial governance framework shown in Figure 3.2 because of changes over time.

Table 3.1: Governance bodies for the Biometric Identification Services project

|

CrimTrac |

ACIC |

|

BIS Steering Committee |

BIS Project Board Executive |

|

BIS Project Board |

PwC resourced Project Management Office |

|

NEC/ACIC Joint Steering Committee |

Commission Executive Committee |

|

BIS Security Forum |

Chief Technology Officers Leadership Group |

|

BIS Commercial Forum |

Technology Capability Committee |

|

Technology Governance Committee |

Chief Information Officers Committee |

|

BIS Engagement Group |

BIS Change Champions |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACIC documentation.

3.7 While the ANAO was able to locate terms of reference for some of these bodies, it could not locate others (such as the BIS Engagement Group and the Chief Technology Officers Leadership Group). ACIC advised:

[It is] Highly likely these were either aspirational and were never established, or if they did exist, we knew them as something different. If it’s the latter, they certainly wouldn’t have had ToRs and were both a communication mechanism and an attempt to create some structure for NEC to bring technical issues to a body for some form of resolution.

3.8 Notwithstanding the existence of ACIC’s governance bodies listed in Table 3.1, governance was not effective. In June 2017, more than a year after the BIS contract was signed, a PwC review commissioned by ACIC reported that the program was yet to define a robust governance structure with roles and responsibilities across the project and that decision-making governance was unclear.

3.9 A further PwC review in November 2017 found similar shortcomings in governance:

- roles and responsibilities in the project team remained unclear;

- lines of communication were unclear;

- terms of reference for components of the governance framework did not exist;

- there was no formal process for escalation of issues to the ACIC executive; and

- the relationship between the BIS project team and ACIC Project Management Office was unclear and had not been defined.

Risk management

3.10 The PGPA Act and the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy require all Commonwealth entities to establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight, management and internal control. In practice, entities generally have both an overarching enterprise risk framework and lower level frameworks and plans for specific programs or projects. Consequently, the ANAO expected to see evidence of the existence of risk frameworks for both the enterprise and BIS.

Enterprise risk management

3.11 It is the responsibility of the entity’s Accountable Authority32 to determine organisational arrangements for designing, implementing, monitoring, reviewing and continually improving risk management throughout the entity.

3.12 The ANAO found evidence that following the merger, ACIC developed a revised enterprise risk framework. This included:

- developing a risk management framework;

- revising and expanding its corporate risk management policy and procedures;

- completing a risk benchmarking exercise;

- strengthening work health safety risk management;

- focusing on approaches to improving risk culture; and

- participating in multi-agency risk forums.

3.13 ACIC also considered the potential value of an enterprise risk management tool to record, monitor and report on agency risks.

Biometric Identification Services project risk management

3.14 Risk management of the BIS project originated in CrimTrac, and processes continued into ACIC for a period after the merger. For example, Ernst & Young (which CrimTrac had initially engaged to perform the role of risk advisor) continued to perform the role of risk advisor for BIS after the merger. The BIS Project Advisory Committee (whose responsibilities included identifying issues and risks requiring steering committee management, resolution or decision) also continued until June 2017. This meant that project risks were aired at appropriate governance forums and some risks were captured in risk systems.

3.15 In March 2016, the CrimTrac Audit and Risk Committee commissioned a review of internal audit status. While the focus of the review was internal audits, the internal audit team observed:

Individual risk owners at CrimTrac are unsure of CrimTrac’s appetite for risk and therefore there is confusion about when and to what extent a risk should be escalated through the existing governance structures.

3.16 After the merger, risks for the BIS project continued to be identified by members of the project team. However not all risks that were identified were included in the existing project risk register. For example, in August 2016, a significant testing risk (that ACIC and NEC use different test management tools) was identified for inclusion in the project risk register. Even in April 2017, this risk was not listed among the 37 risks in the Risk Register that was circulated to the ACIC’s Change Champions network.

3.17 Evidence showed that as well as employing a spreadsheet-style Risk Register, ACIC was also using a tool known as ‘Clarity’ to record risks, allocate risk owners, and propose treatments and record progress. However, risks were not actively managed. While risks to the BIS were clearly assigned to risk ‘owners’ in Clarity, the assignment was not effective because communication and consultation about risk did not materially affect the success of the project. Risk owners ensured that relevant governance bodies received regular updates on risks. When risk owners left the project, risks were not immediately reassigned to new owners.

3.18 In April 2018, two months before the project was terminated, known risks to delivery of BIS included:

- data migration on a critical path;

- solution design documents still not endorsed;

- unfitness and misalignment of certain requirements and documents;

- slippage of testing cycle;

- physical and personnel security;

- NEC had no approval to operate in the Systems Acceptance Test environment;

- inadequate mitigation of cyber intrusions;

- resourcing constraints after departure of experienced NEC staff;

- patchy and inadequate communication between PwC and ACIC BIS teams; and

- absence of a register to capture risks to delivery.

3.19 One week before ACIC discontinued the BIS project, the project had two active registers for BIS risks and issues. The risk register contained 45 open risks and the issues register contained 20 open issues.

ACIC’s Audit Committee

3.20 ACIC’s Audit Committee33, which has responsibility for oversight of risk management in ACIC, did not play an active role in monitoring the status of the BIS project. A member of the Audit Committee advised the ANAO in August 2018 that although the committee received regular reports on some key projects and on the progress of the integration of CrimTrac and ACC, ‘BIS was not identified as a project requiring specific reporting’. The same Audit Committee member also advised that following a review of the committee’s meeting papers for 2017 and 2018, the committee ascertained that it was ‘not advised of any concerns regarding the BIS project during that time’. While the committee considered in June 2018 whether an internal audit of BIS should be added to the ACIC internal audit program, ACIC senior management advised the committee that ‘there would be no significant value in an internal audit being undertaken’.34

3.21 These observations indicate that ACIC’s arrangements for ensuring that the Audit Committee receives timely and accurate reporting of the risk status of key ACIC projects was inadequate. They also suggest that the Audit Committee’s charter to “provide independent assurance and advice to the CEO on the agency’s risk, control and compliance and its financial statement responsibilities” was being compromised, due to a lack of management reporting on key risks and issues.

Was contract management effective?

Contract management was not effective.

- The stipulated contract process by which progress against milestones and deliverables was to be assessed was not followed at any stage and ACIC thus had no way of assuring itself that it got what it paid for.

- ACIC agreed to more than $12 million in additional work. Documentation showed that some of this work may have been unnecessary and other work may have already been covered under the contract.

- ACIC ‘inherited’ the former CrimTrac and ACC Electronic Document and Records Management Systems (EDRMS), leading to duplication and ineffective record keeping. Further, many staff did not use any EDRMS, instead keeping records on their own computers, in uncurated network drives or in email inboxes.

- While a Benefits Management Framework was developed and evidence showed that a benefits realisation and documentation process was intended, it was not implemented.

- An internal audit report had found that ACIC did not have an effective contractor management framework.

ACIC’s contractor management framework

3.22 In May 2016, just after the contract with NEC was signed, a report entitled Internal Audit of Contractor Management was provided to the CrimTrac Audit and Risk Committee. The report noted that CrimTrac had yet to formalise process improvements for contractor management and found that:

- CrimTrac did not have a robust control framework to govern the engagement of contractors from on-boarding through to their exit;

- significant improvements to the end-to-end control framework for managing contractors needed to be implemented;

- ownership, responsibilities and accountabilities for the end-to-end process for managing contractors had not been clearly defined; and

- [there was] a lack of clarity on roles, responsibilities and remit.

3.23 A significant proportion of contract management documentation was still in draft form more than two years after the BIS contract commenced. To avoid confusion after the merger, ACIC should have updated project documentation to reflect new organisational structures and internal stakeholders. Table 3.2 lists some examples of contract management documentation that was not finalised at the time of audit.

Table 3.2: Unfinalised contract management documentation

|

Governance documents |

Date of last revision |

|

Project Risk Management Framework |

March 2013 |

|

Strategic Engagement Framework |

August 2015 |

|

Stakeholder Guide and Communications Plan |

August 2015 |

|

BIS Governance Plan |

November 2015 |

|

Benefits Management Guide |

February 2016 |

|

Contract Schedule 7 Part 3: NEC High Level Design |

March 2016 |

|

Contract Schedule 7 Part 2: NEC Solution Implementation Plan and Risk Management Plan |

April 2016 |

|

Contract Schedule 7 Part 4: NEC Test Plan; Training Plan; Transition In Plan, Data Migration Plan |

April 2016 |

|

Contract Management Plan |

November 2016 |

Source: ACIC.

Contract milestones

3.24 The original BIS contract milestones are shown at Table 2.2. The contract created a framework and process to link the achievement of milestones to payments as follows:

- When NEC considered that it had satisfied a milestone by having completed a Key Project Document35, it would provide ACIC with a Milestone Completion Readiness Certificate.

- If ACIC agreed that the criteria for the milestone had been met to its satisfaction36, it would issue NEC with a Milestone Completion Certificate.

- NEC would only issue an invoice when it had received the Milestone Completion Certificate.

3.25 In practice, this process was not followed at any point by either NEC or ACIC. The ANAO asked ACIC to provide copies of all certificates described in paragraph 3.24 above. In August 2018, ACIC advised that no such certificates existed and advised:

As far as I know neither party followed the agreed process outlined in the contract of certifying that a milestone had been reached; rather we seem to have simply paid off an invoice. This was not deliberate (at least not on our part) but was, I think, the result of not having a contract manager on the team from day one (meaning no-one from ACIC knew what the process should have been).

3.26 As a result of this complete departure from the clearly established contractual process, no evidence exists that any of the 17 milestones shown in Table 2.2 were ever fully met. ACIC accepts that the fundamentally important Solution Design milestone (Milestone 1) was never fully met. With respect to the other 16 milestones, ACIC advised:

If the question is ‘under the contract what milestones are complete?’, then none if we apply the contract terms, but if you accept that neither party followed the process then only one: 2a37as the initial data was eventually loaded.

3.27 In April 2017 (by which time eight of the milestones shown in Table 2.2 should have been completed and thus certified), ACIC recognised that the failure to follow the contractual process meant, at the least, that it could not demonstrate that the project was making progress. ACIC considered whether it could ‘conditionally’ issue certifications for the missed milestones. The evidence showed that this was proposed in order to suggest that the contract was progressing.

3.28 ACIC recognised that the contract did not provide for conditional certification: for the purposes of the contract a key project document was either certified or not certified. By permitting conditional certification, ACIC would create a number of risks, including that NEC could claim that this in fact constituted certification on the basis that ACIC had not stated that it did not certify the relevant key project documents.

3.29 In June 2017, ACIC varied the contract to create ‘preliminary’ (rather than ‘conditional’) certification. On 15 June 2017, ACIC provided NEC with an ‘Acceptance Certificate’ stating that a number of key project documents specified in the Certificate ‘are accepted as certified preliminary key project documents for the purposes of the contract.’ Despite this, on 7 May 2018 (shortly before BIS was terminated), the ACIC CEO wrote to NEC requiring it to complete ‘all outstanding design documentation’. The letter included a list of incomplete documents, most of which were identical to the documents listed in the 15 June 2017 Acceptance Certificate.

3.30 In other words, key documents which ACIC accepted in June 2017 were stated to be incomplete in May 2018. The ANAO asked ACIC for clarification of this matter and was advised:

…neither former BIS Project Manager [named individual] nor [named individual] are in a position to advise whether or not this process was finalised (including the provision of documentation to NEC), as [named individual] was Project Manager at the time this occurred.

3.31 In summary, evidence obtained by the ANAO about milestone completion was confused and contradictory. Despite ANAO requests for clarification, at no stage was ACIC in a position to state with any confidence which Key Project Documents (and therefore corresponding milestones) were actually completed in a manner and to the extent specified in the contract. As noted at 3.26, at the time of audit, ACIC advised that in fact, no milestones were ever actually fully completed.

Additional work not included in contract

3.32 During the course of the project, ACIC approved 11 additional pieces of work which were not included in the original contract. These are shown at Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Additional NEC work not in original contract or contract variations

|

Work |

Agreed cost ($) |

Date |

|

Data remediation |

417,416 |

28 September 2017 |

|

Latent stitchinga |

354,303 |

28 September 2017 |

|

Comparison workflows |

198,764 |

28 September 2017 |

|

Reverse synchronisationb |

4,020,356 |

29 June 2017 |

|

Provisional ICT accreditation/goodwill |

2,944,506 |

21 August 2017 |

|

QPS Hybrid infrastructure increase |

204,582 |

28 September 2017 |

|

QPS Hybrid Implementation |

202,649 |

13 December 2017 |

|

QPS Hybrid Data migration and training |

120,000 |

13 December 2017 |

|

QPS Hybrid Standard Support |

80,410 |

22 February 2018 |

|

QPS Hybrid Premium Support |

416,899 |

22 February 2018 |

|

BIS Hardware Uplift |

3,113,440 |

23 March 2018 |

|

TOTAL |

12,073,325 |

|

Note a: For the purposes of this report, it is not necessary to explain what these pieces of work involved.

Note b: This amount comprised $2,170,356 for NEC and $1,850,000 for Idemia.

Source: ANAO from ACIC documentation.

3.33 While it is not uncommon for a need for additional work to be identified as a contract progresses, the ANAO located evidence that indicated that at least some of the additional work identified in Table 3.3 was either already covered by the contract (and would thus have represented a duplicate payment) or was unnecessary:

Some argument exists (unsubstantiated at this time) that the Latent Stitching proposal is actually part of the existing contract in terms of work NEC should be doing. Having said that, all three proposals have been signed as is. No evidence that the work has taken place is available to the BIS technical staff, but again, this has not been included in the criteria for payment.

- In relation to latent stitching, a 31 October 2017 email from the BIS Commercial Manager said:

- In relation to reverse synchronisation, an ACIC officer who was part of the project team told the ANAO that it was ‘madness’ and technically almost impossible to achieve. A senior executive service officer with knowledge of the project described it as ‘one of the worst decisions that was made’ and that a simple temporary revision to police operating procedure would have avoided the need for it altogether.

Provisional ICT accreditation/’goodwill’ payment

3.34 During fieldwork, the ANAO found references to a payment variously described as a Provisional ICT accreditation38 (PICTA) payment, ‘goodwill’ payment or ‘good faith’ payment of $2,944,506 made to NEC in September 2017 and sought clarification of the details from ACIC. In October 2018, ACIC advised:

At the time [September 2017] we were at an impasse with NEC. From a technology point of view NEC had claimed costs that were over and above the contract milestone payments due to contract deviations (schedule 4a). NEC claimed these deviations were acted upon by NEC in good faith and were agreed with the ACIC. Most of the ACIC staff involved in the email exchanges had left the agency so it was impossible to verify the agency’s intent. Looking at the written records, ACIC’s position is that there was no formal or authoritative agreement for the changes and in fact there were some meeting minutes that suggested that formal agreement to the deviations was explicitly not given. At the time [named officer] and I were of the view that the practicality of delineating responsibilities for the additional NEC expenditure was not going to be productive and would have put the future delivery of the project at risk. The best way forward, in our view, was accept some joint responsibility for the additional NEC effort, and negotiate a partial meeting of their costs. This was seen as a way to navigate the impasse and establish and re-baseline a constructive relationship for the continued delivery of the program.

3.35 The ‘goodwill’ payment does not appear to the ANAO to have been linked to the achievement of any specific milestone under the contract. ACIC was not able to explain how the quantum of this payment was calculated.

Contract reviews

3.36 The BIS contract provided for periodic and other reviews. This included reviews of:

- the scope of items provided or available to be provided pursuant to the contract;

- the adequacy of the performance management framework;

- benefits achieved by CrimTrac/ACIC and the Users under the contract;

- NEC’s performance; and

- how NEC can best support the ongoing needs of CrimTrac/ACIC.

3.37 After the merger, ACIC did not conduct any formal reviews until at least 12 months after the merger, by which time the first design phase was overdue by 12 months. In June 2017, the ACIC Board commissioned PwC to conduct a review of capability and project management gaps (see paragraph 3.8).

3.38 Consistent with clause 15.4.1 of the contract, the PwC review outlined the need for ACIC to critically analyse NEC’s capability to deliver. Following PwC’s recommendation, ACIC expanded the Stakeholder Engagement Team and additional resources (two project support officers, five Stakeholder Engagement Team members, a technical project manager, a contract manager, and a solution architect) joined the BIS project team.

3.39 In November 2017, ACIC invited PwC to return to undertake a formal contract review for ACIC (see paragraph 3.9). This review was not the type of review envisaged in the contract. PwC summarised at high level the work still required for the project, increases to costs, and challenges to successful delivery. Among the review’s findings were the following:

- delivery of the BIS program is currently challenged on multiple fronts spanning strategic to operational levels;

- there is no integrated project schedule or dependency mapping39;

- there are no clear escalation pathways or intervention processes;

- there are no appropriate financial management processes in place for management of the budget;

- contract and performance management processes are not in place;

- there are no management plans in place to address risks and issues; and

- the project has insufficient resources.

3.40 The contract reviews by PwC led ACIC in February 2018 to form a BIS Project Management Office headed by a PwC employee within ACIC. Also in February 2018, ACIC held a series of workshops with NEC Australia and NEC America to confirm actions for NEC.

3.41 ACIC’s final review was the Project Closure Report in July 2018.

Relationship management

3.42 PwC’s October 2014 market assessment (see paragraph 2.8) had noted that timely delivery of the project would depend on strong relationships.

3.43 Evidence showed that the relationship between ACIC and NEC deteriorated to such an extent during the project that ACIC decided to engage PwC to intervene. In December 2017, ACIC contracted PwC to facilitate ‘turnaround’ workshops between ACIC and NEC to ‘reset the relationship’ and ‘build trust’.

3.44 Subsequently in January 2018, ACIC exercised its contractual discretion to request removal and replacement by NEC of its Program Manager. The contract did not require ACIC to provide a reason for its request and ACIC was not able to provide any documented reasons for the request.

3.45 In late January 2018, a new NEC Program Manager arrived but left within two weeks. A third replacement NEC Program Manager also departed in late February 2018.

Recordkeeping

3.46 CrimTrac and the ACC both used an Electronic Document and Records Management System (EDRMS) called TRIM. At the time of audit, the systems had not been integrated and the ANAO located BIS audit evidence in both the former CrimTrac and ACC systems. ACIC advised that while the systems had been updated to the latest versions, it was unlikely to merge them ‘due to cost and the risk of extensive remediation’. In any event, the ANAO found that many staff did not use either of the two former CrimTrac or ACC TRIMs, preferring to store documents in ‘network drives’ or local area networks that are not designed or approved for electronic document storage, retention or retrieval.40 The ANAO also located relevant audit evidence in individual officers’ email accounts and on the ‘C’ drive of their individual computers. ACIC did not implement a systematic approach to retrieving project files from departing staff, so existing files remain incomplete.

3.47 After the audit had commenced, ACIC began a process of locating and collecting relevant records and transferring them into the former ACC TRIM system.

3.48 An example of poor record keeping was the BIS contract itself. While the ANAO located electronic drafts of the contract (or parts of it) in multiple locations, it took ACIC more than four weeks to find and produce a definitive original document.

Resourcing

3.49 Neither the first nor second pass business cases referred to the staffing resources required to manage the BIS project. The Costing Agreement with the Department of Finance (see paragraph 2.15) stated that ‘any staff diverted to the project would be from existing resources’.

3.50 Where a function or project is put out to contract or outsourced, there are certain ‘core’ functions which typically remain in the province of the government entity and therefore require resourcing. In the case of BIS, these included:

- contract management and administration;

- system and software testing;

- stakeholder management;

- progress and status reporting;

- risk management;

- financial management;

- legal advice; and

- records management.

3.51 The inadequacy of BIS staffing resources was referred to as a recurring theme throughout the evidence that the ANAO obtained, although this realisation appeared to happen late in the piece. For example:

- in June 2017, PwC noted that the project team then had 15 staff compared with its assessment of 40 actually required;

- in October 2017, in a project update, the BIS Project Manager noted that ongoing staff reductions to the ACIC project team ‘are creating insufficient stable capacity to maintain schedule and scope’;

- in May 2018, ‘insufficient and inappropriately skilled BIS Program team’ was identified as a ‘key issue’ by the BIS Executive Board (which noted that ‘ACIC are actively recruiting to address these gaps’); and

- some police groups also mentioned the lack of technical reference groups.

3.52 It is also notable that during the just over two-year period of the BIS, there were three different Project Managers.41 In each case, the Project Manager left his or her position abruptly.42 During the audit, the ANAO was made aware of concerns from staff with respect to workplace culture at CrimTrac and ACIC. The ANAO sought comments.

3.53 In August 2018, ACIC confirmed that the three successive Project Managers all left the position in the eight-month period between June 2017 and February 2018. ACIC also advised:

Australian Public Service Census results from 2017 and 2018 highlight a number of agency culture issues, predominantly resulting from the merger of CrimTrac, the Australian Institute of Criminology and the Australian Crime Commission on 1 July 2016, unrealistic time pressures and lack of staff consultation about change… The Integrity Assurance Team received no direct allegations of bullying involving BIS staff.

3.54 NEC’s resourcing of the BIS project was also affected by the imposition of mandatory security clearances and organisational suitability assessments (OSA). As NEC personnel engaged for BIS might have access to very sensitive information about individuals, ACIC required NEC personnel to be cleared to a Negative Vetting Level 1 (NV1) and pass the OSA process.

3.55 As noted in ANAO Audit Report 38 of 2017–18, Mitigating Insider Threats through Personnel Security, AGSVA’s average processing time for this level of clearance in 2016 was around four months. Although the contract listed 76 personnel, more than 200 NEC personnel actually worked on the project.

Benefits realisation

3.56 Benefits realisation plans are used to articulate a project’s benefits, including how benefits will be measured and to whom and when benefits accrue. As noted at paragraph 2.10, the First Pass Business case outlined the expected benefits of BIS and as noted at paragraph 3.23, a detailed Benefits Framework was approved by the CrimTrac CEO in December 2015. However, ACIC did not create a Benefits Realisation Plan for BIS.

Was there effective reporting to relevant stakeholders?

ACIC established appropriate arrangements for reporting to stakeholders. However these were not fully effective because they did not result in sufficient action being taken and the external stakeholders felt that reporting dropped off over time.

Internal reporting

3.57 In September 2014, in anticipation of the need to manage the BIS contract with its multiple stakeholders, CrimTrac created a Stakeholder Management and Communications Plan, which identified key stakeholders and established a reporting framework. However, following the merger, ACIC did not update the Plan to reflect its new organisational structure.

3.58 CrimTrac also established committees with membership that represented stakeholders and end users. Some of these committees (the BIS Steering Committee; BIS Project Advisory Committee, BIS Change Champions and Security Forum)43 continued after the merger. The merger also led to the establishment of new ACIC committees, which although contemplated before the merger, did not come into full operation until after the first design phase of the BIS project was due.

3.59 ACIC did not update the Stakeholder Management and Communications Plan after the merger. Five months after the merger in November 2016, ACIC created a Contract Management Plan outlining a new schedule of meetings at which to report project status. The frequency of meetings varied from weekly to monthly and the purpose of meetings included discussion of concerns, risks and issues, security and commercial matters.

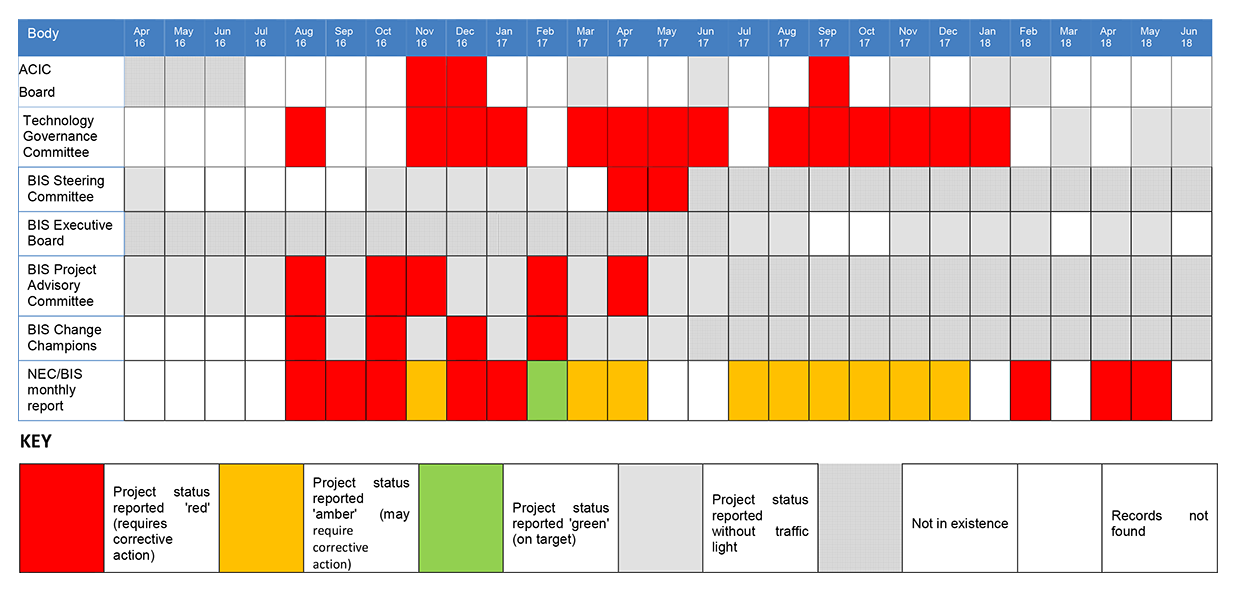

3.60 The ANAO located a large number of reports prepared by the various bodies referred to above, including weekly project-level reports (albeit with some gaps). Table 3.4 shows the overall project status as it was reported to various higher-level governance committees using a ‘traffic light’ system. Table 3.5 shows the membership of each of the bodies shown in Table 3.4.

Table 3.4: BIS project status as reported to selected governance bodies, April 2016 to June 2018

Source: ANAO from ACIC documentation.

Table 3.5: Selected governance bodies membership

|

Body |

Membership |

|

ACIC Board |