Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Protecting Australia’s Missions and Staff Overseas: Follow-on

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective is to examine the effectiveness of measures taken to strengthen the protection of Australia’s missions and staff overseas.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for Australia’s external affairs and ensuring a collaborative whole-of-government approach to the conduct of Australia’s international relations. This responsibility is supported by DFAT’s network of 104 overseas diplomatic posts, which are staffed by approximately 897 Australian, and 2419 locally engaged, DFAT staff as at 30 June 2017. Around 20 other Australian Government agencies have official interests that require a presence at DFAT posts.

2. Australia’s diplomatic posts and staff overseas are exposed to a range of security threats, from politically motivated violence, general crime, civil disorder to espionage. The level and types of threats vary for each post depending on a range of factors.

3. DFAT has allocated overseas security responsibilities between DFAT Canberra and post management, with primary responsibility at posts held by the Head of Mission/Post. DFAT’s Security Branches division in Canberra undertakes a wide range of activities to support security at overseas posts, spending $114.5 million in 2015–16.

4. Since 2012, DFAT has commissioned several reviews of its arrangements for protecting staff and posts overseas and is currently implementing recommendations from the 2015 internal review.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of measures taken to strengthen the protection of Australia’s posts and staff overseas.

6. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO assessed whether:

- a robust security framework that articulates an appropriate risk management and security standards regime to assess and reflect risks at overseas posts was in place;

- appropriate security guidance, training and resourcing arrangements enabled the protection of Australia’s overseas posts and staff;

- security measures are effectively deployed, maintained and procedures are kept up-to-date, and lessons learned are captured to improve security at overseas posts; and

- arrangements to monitor and consult on the effectiveness of the security arrangements at overseas posts are effective.

Conclusion

7. The ANAO’s review of Australia’s overseas missions identified that DFAT has arrangements in place to provide security to overseas missions and staff. Aspects of the delivery of the overseas security, in particular the strategic planning, management of security measures and elements of the framework supporting staff training, have not been fully effective.

8. DFAT has a comprehensive Security Manual setting out policy, procedures and processes. DFAT undertakes threat and risk assessments of locations where DFAT has overseas posts. Implementation of the recommendations arising from DFAT’s security reviews would be more effective if a comprehensive plan was in place that encompasses the internal review recommendations, as well as a forward looking plan that articulates the desired end state for DFAT overseas security. A comprehensive plan would drive more consistent monitoring of reform activities underway. DFAT would also benefit from enhancing the recording of overseas post security measures to better inform the monitoring of post security risks.

9. DFAT’s arrangements to provide overseas security training have been generally effective. DFAT has established an overseas security training framework to support the delivery of training to overseas staff, and staff with dedicated security advisory roles. There are opportunities to further enhance security training and guidance for deployed and specialist security staff, as well as DFAT’s ability to monitor and analyse staff training across posts.

10. DFAT has arrangements in place to specify overseas physical security measures and select and deploy the measures to posts. The manner in which these measures have been deployed and managed has not been effective in all cases. Improving the specifications and guidance for all physical and operational security measures at posts would help mitigate security risks. DFAT has in place overseas security inspection arrangements to provide assurance on the effectiveness of security measures in place at posts. The effectiveness of these inspections could be enhanced through a centrally coordinated process for planning and recording security inspections.

11. DFAT has in place monitoring and reporting on security at overseas posts, however the effectiveness of the monitoring and reporting is limited as it is not consistently implemented or verified. This reduces the assurance provided by these arrangements that security at overseas posts is effectively mitigating risks.

12. The ANAO notes the department’s view that it has made progress in strengthening its security arrangements during the time of the audit.

Supporting findings

Overseas security framework

13. Following a number of internal reviews, DFAT has commenced reforms to address security capability gaps. These include the establishment of a Departmental Security Committee, improvements to security training and the decision to develop a Security Framework. The development of a forward looking strategy and an implementation plan would assist DFAT in managing the security reforms.

14. The DFAT Security Manual is the central policy document underpinning the delivery of security overseas. The Security Manual provides comprehensive security instructions for overseas posts and personnel security, however at the time of audit fieldwork the manual was not available to all staff due to its security classification. DFAT commenced a project to review security policies and the Security Manual, which included reassessing the security classification of the Security Manual. DFAT has now enabled all staff to access the Security Manual. The Security Manual would however benefit from a consistent delineation of the security roles and responsibilities between the Heads of Mission/Post and DFAT Canberra.

15. DFAT has established a group of analysts to undertake a program of ongoing threat assessment for overseas posts. However, the current framework for undertaking security risk assessments does not promote quality and consistency in assessments across the posts. In addition, the lack of consolidated information on existing security measures in place across the posts imposed limitations on DFAT’s ability to identify and report security issues and measures to senior management.

16. The ANAO identified instances where DFAT had not appropriately managed sensitive and classified information. Further guidance and support to posts would better position them to manage classified material.

Guidance, training and skills

17. DFAT has an overseas security training framework in place to support Australian staff deployed to overseas posts, locally engaged staff, and staff with dedicated security advisory roles. Security training provided to Australian and locally engaged staff is generally effective in supporting their needs at overseas posts, although there are opportunities to enhance the Security Leaders Training for Post Security Officers through practical guidance on the day-to-day security activities undertaken in that role.

18. DFAT deploys its Regional Security Advisers to higher threat posts on a risk basis. While DFAT has improved management and support of Regional Security Advisers, these roles would benefit from a formalised training package.

19. DFAT has commenced activities to enhance the policies and procedures to train Canberra-based security staff. Further improvements could be made to the training and guidance of specialist security staff undertaking security inspections of posts.

20. The information systems used to record the department’s security training information do not provide management with informative reporting and assurance that staff deployed overseas have the appropriate security training. Improvements in DFAT’s ability to monitor and analyse security training would assist DFAT in managing risk and provide more meaningful governance and oversight.

Overseas arrangements for security measures

21. DFAT’s arrangements overseas are based on the ‘security-in-depth’ security management principle. DFAT has largely established minimum specifications for physical security measures deployed to posts. There is limited guidance to overseas posts on operational security measures, such as guarding standards for different threat environments. There would be benefit in DFAT providing further guidance on these issues.

22. DFAT identifies the security measures to be deployed to overseas posts based on an operational threat assessment and a security risk assessment. There is no documented end-to-end process or procedure connecting the activities that inform the deployment of security measures, which are undertaken by different sections in the Security Branches division. This reduces DFAT’s effectiveness in determining the appropriate security measures to be deployed to posts.

23. DFAT undertakes overseas security inspections to ensure posts are appropriately protected. However, these inspections are not centrally coordinated or recorded. Inspection reports have varied in quality, yet recent reports have shown evidence of improved format and content consistency.

24. Based on the evidence from the four posts visited during the audit, each of which presents very different threat and risk environments, DFAT’s security measures at overseas posts are not being effectively managed and maintained in all cases.

25. The overseas posts visited during the audit had Crisis Action Plans in place, which include both business continuity planning and consular crisis planning. Testing of Crisis Action Plans at the posts visited was oriented towards consular crisis events external to the post rather than a security incident against the post or post staff. Crisis Action Plans would benefit from a greater focus on managing security incidents at posts.

Monitoring, reporting and consultation

26. DFAT monitors security arrangements at overseas posts through a combination of overseas security inspections and self-assessments. DFAT does not have a consistent process in place to ensure all self-assessments are accurate, reported and that identified security issues are actioned.

27. DFAT reports annually against the performance obligations for delivering security overseas as outlined in the Portfolio Budget Statements for the Foreign Affairs and Trade Portfolio. However, these performance indicators do not allow for a meaningful assessment of the extent to which DFAT is achieving its objectives.

28. DFAT has processes in place for reporting security incidents and breaches. The security breaches database has data integrity and system limitations that reduce DFAT’s ability to accurately record and consistently respond to security breaches. ANAO fieldwork at overseas posts identified instances of security incidents and breaches not being reported.

29. DFAT’s Internal Audit Branch is responsible for providing assurance on DFAT’s activities, controls, compliance with requirements and identifying opportunities for improvement to the DFAT Audit and Risk Committee. Post the 2015 Review, Internal Audit has included an audit in the Security Branches division of ‘Security Clearances: Processes and Outcomes’ in its 2016–17 work program as part of standard risk based internal audit planning.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.20

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade develop:

- a strategic plan that addresses its future security needs and aligns with key activities of the department, including encompassing all the reforms and activities underway; and

- a detailed implementation plan for addressing the 2015 internal review recommendations, as one of the reforms captured in the strategic plan.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.41

To better inform governance and oversight by the Departmental Security Committee, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade:

- develop and maintain a comprehensive database of physical and operational security measures at overseas posts; and

- develop a more consistent framework for assessing security risks for overseas posts.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.26

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade develop mechanisms to provide assurance that staff receive the required security training for their posting, and to inform future planning and improvements to the security training program.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 4.11

That the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade enhance the coordination of the deployment of security measures to achieve greater consistency when determining security measures to be deployed to overseas posts.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 4.21

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade refine a framework for risk-based selection of posts for security inspection, improve the deployment of inspection staff resources, and develop consistent standards and accountability mechanisms to enable the timely identification and resolution of security vulnerabilities at posts.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 4.26

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade strengthen arrangements for managing and maintaining security measures at overseas posts to ensure the measures appropriately mitigate identified risks.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.7

Paragraph 5.17

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade develop an information system to respond to security breaches, and identify trends and mitigation strategies, based on reliable and useful breach data.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

30. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trades’ summary response to the report is provided below. The full response is outlined in Appendix 1.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) welcomes the audit report Protecting Australia’s Missions and Staff Overseas: Follow-on (the Report).

DFAT takes very seriously its responsibilities for the security of staff, property and information at its overseas missions. DFAT accepts the Report’s recommendations, which are broadly in line with the ongoing implementation of reviews commissioned by DFAT in 2015.

DFAT would have welcomed more recognition in the Report of the measures taken and progress made to strengthen DFAT’s security culture, procedures and systems following the internal reviews. DFAT also does not agree fully with all of the Report’s supporting findings.

However, DFAT will be guided by the Report and will implement its recommendations to build on and further enhance DFAT’s commitment and ongoing program of work to strengthen DFAT’s security culture and to fulfil its security responsibilities in Australia and overseas.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for ‘Australia’s external affairs and ensuring a coherent, consistent and collaborative whole-of-government approach to the conduct of Australia’s international relations’.1 This responsibility is supported by DFAT’s network of 104 overseas diplomatic posts.2 DFAT’s posts contribute to the advancement of Australia’s national interests by undertaking diplomacy activities and by providing consular and passport services to Australian nationals within their host country or accredited regions.

1.2 Recent global security events, such as terrorism incidents in Europe, Africa and Asia, along with ongoing instability and conflict in the Middle East, continue to illustrate the evolving and dynamic overseas security environment in which the Australian Government operates its diplomatic posts.

1.3 Australia’s diplomatic posts and staff overseas are exposed to a range of security threats, including politically motivated violence, general crime, civil disorder and espionage. The level and types of threats vary for each post depending on a range of factors, such as ongoing conflict or civil unrest, capacity of the host government to provide a secure environment or the value of the information or assets held at the post.

1.4 The security threat against Australia was directly realised in September 2004 when the Australian Embassy in Jakarta was bombed resulting in nine fatalities, and injuries to 150 others. Following the attack the Australian Government approved a funding package of $860 million over four years to upgrade security at Australia’s overseas posts.3

1.5 Reflecting this overseas security environment DFAT has recognised that the security risk for which it is responsible is:

among the most extensive and potent in the department, and is growing. Elsewhere [in the department] poor risk management could be financial loss; here [in relation to security] the results could be catastrophic’.4

1.6 Two high-level Australian Government policies inform DFAT’s responsibility for, and management of, security at Australia’s overseas posts.5 The Prime Minister’s Directive: Guidelines for the Management of the Australian Government Presence Overseas gives DFAT responsibility for:

the implementation of appropriate physical, technical, information and personnel security procedures, measures and standards, and for coordinating business continuity and contingency planning at each mission/post.6

1.7 The Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) provides the high-level security policy, guidance and better practice advice for governance, personnel, physical and information security for all Australian Government entities. While the PSPF reflects that each Australian Government entity is best placed to assess their own risk environment and apply appropriate security controls, it does include a number of mandatory requirements to assist entities manage their risks. The PSPF acknowledges that some of the requirements may be difficult to apply overseas, and DFAT is responsible for providing specialist advice on overseas security standards.7

1.8 DFAT applies these policy frameworks to the overseas security environment, where it must consider and decide on appropriate policy settings. This presents DFAT with the dual challenge of establishing overseas security policies and standards, while also having to monitor, enforce and report against the appropriateness of the policies across the decentralised overseas post network. DFAT must determine, on a risk basis, the extent of responsibility for security devolved to overseas posts. Maintaining sufficient central oversight to support consistency across the network is difficult given that overseas posts are geographically removed and operating in a variety of threat environments.

Australia’s diplomatic network

1.9 DFAT’s 104 posts are located across more than 80 countries and are staffed by approximately 897 Australian, and 2419 locally engaged, DFAT staff as at 30 June 2017. Around 20 other Australian Government agencies have official interests that require a presence overseas at DFAT posts, with the larger agencies overseas including the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, Austrade, the Department of Defence and the Australian Federal Police.8 These other agencies have approximately 1159 Australian and 2042 locally engaged staff across DFAT posts.

1.10 Australia’s diplomatic posts range in size from large complex offices with up to 417 staff, to small posts of five staff. The posts comprise the chancery facility (embassy, high commission or consulate building) and staff residences, which can range from freestanding buildings within a compound, high-rise office space or apartment buildings.

1.11 DFAT is responsible for security arrangements at overseas posts, and has devolved some security responsibilities to post management, with primary responsibility at posts held by the Head of Mission/Post. The Head of Mission/Post is supported by a Deputy Head of Mission/Post, who in addition to their primary diplomatic role, holds the Post Security Officer role (in most cases), and as such is responsible for the day-to-day management of security arrangements. DFAT has 15 Regional Security Advisers located overseas. Regional Security Advisers are responsible for supporting either one or multiple posts within a region, through activities such as security risk assessments, inspections, procurement of security equipment and provision of security advice. Not all posts or regions are supported by a Regional Security Adviser rather, the allocation of a Regional Security Adviser is driven by the assessment of risk at particular posts.

1.12 DFAT’s Security Branches division located in Canberra supports the Head of Mission/Post in delivering security at overseas posts.9 The Security Branches division is responsible for all elements of DFAT’s protective security both overseas and within Australia, excluding IT and cyber security which is managed by the Information Management and Technology Division. The Security Branches division undertakes a broad range of activities as reflected in Box 1.

|

Box 1: Responsibilities of the Security Branches division |

|

1.13 To carry out its responsibilities the Security Branches division had 77 staff, including 61 full time equivalent (FTE) and 16 contractor positions, as at 30 June 2016. In 2015–16, the Security Branches division spent a total of $114.5 million, with $56 million or 48.9 per cent of funding expended on the security service contracts for armed guarding at the Kabul and Baghdad posts, as outlined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Security Branches division expenditure on overseas security

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT information.

1.14 Each of DFAT’s 104 posts is funded through a consolidated annual budget from which all post expenses (staffing, property, consular and security) must be met.

Security reviews

1.15 Since 2012, DFAT has commissioned several reviews of its arrangements for protecting staff and posts overseas. A 2014 review assessed DFAT’s threat analysis capability, while the broader operations of DFAT’s Security Branches division were examined in 2012 and 2015. In response to recommendations made in the 2015 internal review, DFAT has:

- appointed a Chief Security Officer;

- established a Diplomatic Security Committee that provides a governance body to oversee the department’s security activities;

- reinstated the former Security Training Section and developed a new pre-posting training program in an effort to better raise security awareness and expertise of deployed staff; and

- revised physical security standards and processes, along with a continuing program to update security policies.

Previous ANAO report

1.16 The ANAO previously reviewed the protection of missions and staff overseas in ANAO Audit Report No.28 2004–05 Protecting Australian Missions and Staff Overseas, which was tabled in Parliament in February 2005. This audit recommended that DFAT improve security guidance and training, security risk management, the implementation and effectiveness of security measures in mitigating risk and the monitoring of security at overseas posts.

Audit approach

1.17 The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of measures taken to strengthen the protection of Australia’s posts and staff overseas.

1.18 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO assessed whether:

- a robust security framework that articulates an appropriate risk management and security standards regime to assess and reflect risks at overseas posts was in place;

- appropriate security guidance, training and resourcing arrangements enabled the protection of Australia’s overseas posts and staff;

- security measures are effectively deployed, maintained and procedures are kept up-to-date, and lessons learned are captured to improve security at overseas posts; and

- arrangements to monitor and consult on the effectiveness of the security arrangements at overseas posts are effective.

1.19 The audit team examined DFAT records, consulted with a range of stakeholders, including DFAT staff at visited posts and those who had recently returned from a posting, and sought submissions from all posts and Regional Security Advisers on the overseas security arrangements.

1.20 The audit team undertook overseas audit fieldwork at four DFAT posts in the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Europe to provide insight into the management of security arrangements at posts. At each post, the audit team inspected the security arrangements both inside and outside the post, Head of Mission/Post residence and other staff residences, and interviewed DFAT and attached agency staff.

1.21 The audit did not include a review of: DFAT’s security service contract arrangements for the Baghdad and Kabul posts, as these arrangements are unique to those two locations; and the security arrangements for the 16 Austrade managed posts. DFAT’s delivery of domestic security and cyber security arrangements were not in the scope of the audit.10

1.22 The ANAO engaged the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation T4 Protective Security (ASIO-T4), to provide protective security advice based on the Australian Government PSPF standards in relation to physical security measures, security standards and risk management.11 The ANAO considers that the PSPF security standards form the minimum security standard DFAT should apply overseas where practical, given the limitations of operating in a foreign environment.12 ASIO-T4 assisted the ANAO’s review of the effectiveness of physical and operational security measures in place at the DFAT posts visited as part of the audit.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $764 000.

Omission of sensitive information

1.24 In accordance with section 37(1)(a) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (Cth) (the Act), the Auditor-General has determined to omit particular information from this public report. The reason for this is that such information would prejudice the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth, as per section 37(2)(a) of the Act.

1.25 In accordance with section 37(5) of the Act, a report including the omitted information has been prepared and a copy provided to the Prime Minister, the Finance Minister and the Minister for Foreign Affairs.

2. Overseas security framework

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) supporting arrangements for the deployment and management of physical security measures across the network of overseas posts. It examines the changes DFAT has put in place in response to the 2015 internal review of overseas security. It also examines DFAT’s management of security instructions for overseas posts, security risks, funding for security, and the protection of classified information.

Conclusion

DFAT has a comprehensive security manual setting out policy, procedures and processes. DFAT undertakes threat and risk assessments of locations where DFAT has overseas posts. Implementation of the recommendations arising from DFAT’s security reviews would be more effective if a comprehensive plan was in place that encompasses the internal review recommendations, as well as a forward looking plan that articulates the desired end state for DFAT overseas security. A comprehensive plan would drive more consistent monitoring of reform activities underway. DFAT would also benefit from enhancing the recording of overseas post security measures to better inform the monitoring of post security risks.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving DFAT’s strategic planning and management of overseas security reforms currently underway, and to introduce arrangements to record all security measures at posts, along with undertaking assessment of residual risk for posts.

How has DFAT responded to identified security capability gaps?

Following a number of internal reviews, DFAT has commenced reforms to address security capability gaps. These include the establishment of a Departmental Security Committee, improvements to security training and the decision to develop a Security Framework. The development of a forward looking strategy and an implementation plan would assist DFAT in managing the security reforms.

Reviews of the Security Branches

2.1 In 2015, the Secretary of DFAT commissioned an internal review of diplomatic security, focussing on the activities of the former Diplomatic Security Branch. The review covered a range of areas and made a total of 27 recommendations, relating to such issues as:

- inadequate executive oversight and governance arrangements;

- limitations with the structure and resourcing of the former branch;

- need for improved security training;

- limitations in the overseas physical security standards; and

- variable security awareness across the department.

Implementation of review recommendations

2.2 The status of the 27 recommendations was reported to the Departmental Security Committee on 28 October 2016. The ANAO reviewed the status report and found that DFAT did not have a plan for implementing the recommendations. In addition, reporting of implementation did not delineate between recommendations that had been completed, were closed for other reasons or remained inactive. ANAO assessment of other recommendations identified incorrect reporting of current implementation status. The ANAO’s analysis of the 2015 review recommendations as at 28 October 2016 is summarised in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: ANAO assessment of 2015 review recommendation status

|

ANAO assessment status |

Number of recommendations |

ANAO description of assessment |

|

Fully implemented |

6 |

Recommendations were implemented in full or consistent with the intent of the recommendation. |

|

Partially implemented |

3 |

Aspects of the recommendation were implemented, and recommendation is considered complete. |

|

Implementation underway |

5 |

Implementation of the recommendation was underway or ongoing. |

|

Not implemented |

7 |

Recommendations have not been implemented. |

|

Unclear on status |

3 |

It was not clear in the reporting the current status of these recommendations. |

|

Not agreed by DFAT |

3 |

Recommendations that were considered by the departmental executive that were not agreed to. |

Source: ANAO analysis, as at 28 October 2016.

2.3 DFAT would benefit from outlining an implementation plan that defines the actions to be taken, along with resourcing and timeframes for each recommendation to be implemented, and reporting against progress.

2.4 The following sections outline some of the key recommendations and reforms DFAT has progressed from the 2015 internal review.

Improved security governance

2.5 The 2015 internal review identified the need for greater executive oversight of the former Diplomatic Security Branch. It recommended the elevation for the former branch to divisional status, comprising two branches and the creation of a Chief Security Officer to oversee the new division. The intent was to improve executive oversight as the new division head would be ‘substantially freed from operational matters … to take a more strategic, relationship-building and internal advocacy role’.13

2.6 DFAT established the new Chief Security Officer and the Security Branches division in March 2016, comprising two branches.14 These changes have improved executive oversight of DFAT’s security matters.

2.7 The 2015 internal review also recommended the establishment of a diplomatic security governance body, the Departmental Security Committee, noting the:

department’s senior executive need to be well informed of security trends, threats and vulnerabilities, security incidents and incident responses, the effect of security settings on the department’s business and the residual risk which the department accepts. It also needs a forum to coordinate the activities of other divisions with security functions and arbitrate differences of views between them.15

2.8 DFAT established the Departmental Security Committee in July 2015. The committee’s purpose is to ‘set the strategic direction for DFAT’s security responsibilities for staff, property and information, and oversee their effective management and operation’. The committee’s terms of reference include: consider security threats, trends and incidents and decide on appropriate departmental responses; assess key security risks and risk mitigation measures and monitor the impact of residual risks on business operations; and confirm that appropriate governance arrangements are in place for DFAT security programs and operations.

2.9 The ANAO reviewed the meeting minutes (for the first five meetings) against the terms of reference and found the committee focused on Security Branches division activities and reforms arising from the 2015 internal review. During the meetings, the committee did not consider and accept the residual security risks across the overseas post network. Noting that the Departmental Security Committee was recently established and is still maturing, there would be benefit in the committee including on future meeting agendas, matters that cover the full remit of its terms of reference.

Improved security training

2.10 DFAT commenced reforms to the security training function in 2015, including16: reinstating the former Security Training Section in August 2015, which had been abolished in 2013; and revising the overseas security training framework, including by removing duplicated training content. DFAT has not developed a plan to manage or prioritise the overseas security training framework reforms, or established mechanisms to systematically monitor and evaluate overseas security training.

Security framework

2.11 The 2015 internal review made a range of findings related to DFAT’s current security policy model, which included:

- security awareness in the department is variable, and that an absence of security awareness in any area of the department is a security vulnerability;

- the need to make the security manual more user-friendly, accessible to all staff and based on risk rather than compliance, including declassification where appropriate;

- the need to improve the guidance on roles and responsibilities of posts, as the authority and role of the Post Security Officer is ‘currently sketched in the vaguest of terms’ in the Security Manual17;

- the need to address inconsistencies and contradictions between Security Manual policy and the actual practice at posts; and

- inconsistencies in the security culture and performance across posts.

2.12 One measure, through which DFAT has sought to address the 2015 internal review findings, was to update the Security Manual. Throughout the process of updating the Security Manual in 2016, DFAT identified that the current Security Manual approach would not adequately address its key challenges and has commenced developing a Security Framework based on a risk management approach. The proposed Security Framework moves away from the current single and comprehensive security policy document, and is soundly framed on a three tiered approach for managing security risks and policies. Table 2.2 outlines the characteristics of the three tiers.

Table 2.2: Proposed Security Framework structure

|

Framework tier level |

Description of tier |

|

Tier 1 – Governance |

Outlining the strategic direction, tolerance levels and DFAT’s approach to security risk management, including security business-level impacts, security principles, roles and responsibilities, reporting and assurance processes. |

|

Tier 2 – Security Policy |

Specifying DFAT’s mandatory policy requirements that meet legislative and government security requirements. Developed to be proportional to the risk, and the minimum necessary under the Australian Government’s Protective Security Policy Framework to achieve an effective outcome. |

|

Tier 3 – Standard Operating Procedures |

Standard Operating Procedures will support security policies by providing practical guidance, better practice information and standard templates. |

Source: DFAT.

2.13 Given DFAT’s decentralised post management arrangements and the identified need to improve security culture and awareness of staff, it is intended that the new Security Framework will include an accountability matrix that will articulate clear accountabilities for all staff. The accountability matrix aims to reinforce and improve security culture and awareness across the department that all staff have a professional responsibility to safeguard the security of staff, information and assets across Australia’s diplomatic network of posts.

2.14 DFAT’s Executive endorsed the development of the new Security Framework on 25 November 2016, including releasing an updated Security Manual as an interim measure in early 2017 while the new Security Framework is being developed. The Departmental Executive expects the Security Framework to be completed by late 2017.18

Strategic planning

2.15 The 2015 internal review recommended ‘as an early item of business’ that DFAT develop a business plan and a change agenda, with divisional priorities flowing through to work plans for each work unit to support the reforms and clarify roles and responsibilities.19

2.16 The new Security Branches division has developed an annual business plan for 2016–17, as a departmental requirement for all divisions. This plan is the first departmental business plan focused only on security, and summarises the intended results, delivery strategies, performance measures and key risks. DFAT has not developed a change agenda.

2.17 DFAT has developed specific strategic plans to address two of the recommendations made as part of the 2015 internal review, these being:

- a Security Communications Strategy and Action Plan for 2016–17 to improve engagement with the rest of the department; and

- an Internal Communications Action Plan 2016–17 to improve communication and relationships between the division’s sections.

2.18 DFAT also developed a five year strategic plan for one business unit, the Security Counter Measures Five Year Strategic Plan 2015–19.

2.19 While meeting the departmental divisional business plan requirement, the Security Branches division’s 2016–17 business plan does not meet the need for forward-looking strategic management of DFAT’s overseas security, or adequately address the scale of challenges outlined in the 2015 internal review. DFAT would benefit from developing a strategic plan that encompasses the reforms and activities underway, such as the new Security Framework, to ensure the desired changes in the provision of security for the department are achieved over the long-term. The strategic plan should assess the future security needs and be aligned with the key activities of the department, and provide the foundation to manage and assess change.

Recommendation no.1

2.20 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade develop:

- a strategic plan that addresses its future security needs and aligns with key activities of the department, including encompassing all the reforms and activities underway; and

- a detailed implementation plan for addressing the 2015 internal review recommendations, as one of the reforms captured in the strategic plan.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

2.21 The Department’s Departmental Security Framework, on which work began in 2016, will reflect future security needs as well as including the reforms and activities that have been underway since the 2015 internal review of diplomatic security. The Department expects to have the Framework finalised and in operation by the end of 2017.

Does DFAT have comprehensive security instructions for posts and personnel security overseas?

The DFAT Security Manual is the central policy document underpinning the delivery of security overseas. The Security Manual provides comprehensive security instructions for overseas posts and personnel security, however at the time of audit fieldwork the manual was not available to all staff due to its security classification. DFAT commenced a project to review security policies and the Security Manual, which included reassessing the security classification of the Security Manual. DFAT has now enabled all staff to access the Security Manual. The Security Manual would however benefit from a consistent delineation of the security roles and responsibilities between the Heads of Mission/Post and DFAT Canberra.

2.22 The Security Manual outlines the requirements and policies with which posts must comply, including having in place local security instructions on how the Security Manual is implemented specifically at each post. The Security Manual provides guidance and templates on how to draft local security instructions. All overseas posts visited by the ANAO during the audit had Post Security Instructions in place, with variations based on the different security environments at each post.

2.23 While the Security Manual is comprehensive in detail, there are inconsistencies and contradictions between Security Manual policy and the actual practice at posts, with the 2015 review identifying instances where practice at post has not aligned with policy. In February 2016 DFAT commenced a project to review DFAT’s security policy, the Security Manual and other security outreach information. This review is ongoing and should ensure that inconsistencies such as alignment between security policy and practices are resolved.

2.24 At the time of audit fieldwork the Security Manual, classified at the ‘Confidential’ level, was not available to staff at overseas posts that do not have a security clearance that allows access to information at that level (commonly locally-engaged staff). As part of review of the Security Manual DFAT reassessed the classification of the Security Manual material with the aim of providing the security policies, guidance and information contained within the manual to all DFAT staff. An ‘Unclassified’ version of the Security Manual was published on the DFAT intranet in April 2017 enabling all staff, including those without a security clearance, to access the department’s security policies.

2.25 The DFAT Security Manual reviewed during ANAO fieldwork did not clearly and consistently articulate the responsibilities for overseas security, as it holds the Head of Mission/Post accountable for all aspects of security at their post, while also centralising in DFAT Canberra certain security functions that the Head of Mission/Post cannot control. For example, the Security Manual clearly states that the Head of Mission/Post is accountable for ‘all aspects of physical, technical and personnel security at Missions overseas’, while other parts of the document divide those responsibilities between the Head of Mission/Post and DFAT Canberra. In reviewing the Security Manual, DFAT would benefit from a clear and consistent articulation of the security roles and responsibilities of the Head of Mission/Post and DFAT Canberra at overseas posts.20

Are security risks assessed, monitored and reported effectively?

DFAT has established a group of analysts to undertake a program of ongoing threat assessment for overseas posts. However, the current framework for undertaking security risk assessments does not promote quality and consistency in assessments across the posts. In addition, the lack of consolidated information on existing security measures in place across the posts imposed limitations on DFAT’s ability to identify and report security issues and measures to senior management.

Security threat assessments

2.26 The Security Branches division is responsible for undertaking threat assessments globally with regions split into the following groups: Asia, Africa and Europe; Middle East and Eurasia; and domestic security and the Pacific. DFAT assesses four categories of threat:

- politically motivated violence (terrorism);

- civil disorder (instability or protests);

- crime (general criminal activities); and

- foreign intelligence (espionage conducted by host or third party).

2.27 DFAT undertakes two types of threat analysis. The first is an operational threat assessment that is undertaken prior to the establishment of a new post. This is a whole-of-country assessment that informs decisions around the location, building construction and security measures required for the protection of that post. The second, a tactical threat analysis, is focused on threat analysis that examines the day-to-day operational threats for a particular post. The focused threat analyses are undertaken on a regular basis—either at the request of a post or when the threat environment changes.

2.28 DFAT allocates each post a threat rating for each of the four threat types. DFAT draws on reporting and information obtained from posts, the National Threat Assessment Centre, intelligence sources, the Office of National Assessments Open Source Centre and public sources to compile the overall threat rating for foreign intelligence, politically motivated violence, civil disorder and crime for each post. To help inform these assessments, posts are required on an annual basis, to provide the post’s most recent Threat Information Report.21

2.29 DFAT holds information on historic threat ratings for overseas posts in a variety of different locations. This limits DFAT’s ability to collate and report information efficiently when examining trends in threat ratings across the network of posts.

Assessment of residual risk

2.30 To determine the residual security risks of an overseas post, DFAT completes a security risk assessment that identifies the types and ratings of threats facing each post and analyses the effectiveness of the security measures in place to mitigate those threats. The risks that remain after mitigation are residual risks. DFAT can recommend the deployment of other security measures as additional mitigation or decide that the residual risks are tolerable.

2.31 Information on the security measures in place at overseas posts is not centrally recorded in DFAT, with security measures recorded in various ways, including at posts, and DFAT had no assurance on whether records were accurate or current.22 As a result, DFAT Canberra has in some instances relied on Post Security Officers to report on the security measures in place at overseas posts. Feedback from interviewed Post Security Officers highlighted that they only became aware of some post security measures after arriving at post and had conducted their own orientation (discussed further in Chapter 3).

2.32 At the time of the previous ANAO audit, DFAT Canberra annually reviewed the threat ratings and residual risks of each post based on the security measures in place. The department used an Overseas Security Management System (OSMS) database, established in June 2002, which contained information on all security measures in place at overseas posts to complete this task. DFAT kept the database current by sending an extract to each post to be updated annually. At the time of this ANAO audit the OSMS database had been withdrawn from use and DFAT was unable to advise the ANAO when use of the OSMS database had ceased.

2.33 During the ANAO audit, DFAT commenced developing a spreadsheet to centrally record security assets purchased by the Security Branches division or posts, based on data held in DFAT’s financial management system. This is a positive step to improve DFAT Canberra’s central recording of the security assets in place at overseas posts. However, recording security asset information may not in all cases provide a sufficient level of detail to adequately record all security measures at posts, such as: particulars and maintenance requirements of items; the number or placement of items such as security cameras; or the particulars of operational measures such as the local guarding arrangements.

Quality and consistency of security risk assessments

2.34 DFAT’s current consequence levels are not appropriate for making an assessment of risks to information security, such as from foreign intelligence threats, because the quantifiers for data breaches (moderate/major/severe) are not currently defined, which impacts on the consistent assessment of the risk. DFAT has commenced developing business impact levels as part of the new Security Framework, which is due to be completed in late 2017.

2.35 The acceptable (or tolerable) level of risk in DFAT’s security risk assessments has not been set based on consistently applied criteria or considered by an appropriate decision-maker. The tolerable level of risk in specifying risk treatment is determined, in most cases, by the officer undertaking the risk assessment. This has led to the same risk being assessed differently across a number of posts. The lack of consistently applied criteria can impact the selection and deployment of security measures at posts.

2.36 DFAT’s security risk assessments reviewed by the ANAO were of a variable quality, with examples including:

- listing the absence of a threat as an existing control even though this is not within DFAT’s control. For example, the lack of a previous terrorist attack is not necessarily a reason for lower risk treatments, especially for the low probability, high consequence risks faced by DFAT; and

- identifying ‘existing controls’ without highlighting any limitations. For example, one risk assessment analysed by the ANAO listed ‘x-ray machine’ and ‘guards’ as existing controls even though the report itself observes that these measures are ineffective as the guards do not know how to operate the machine and do not have Standard Operating Procedures in place.

Reporting of risk outcomes

2.37 DFAT’s divisions, posts and state and territory offices record their identified risks in their business plans and risk registers, which are reviewed by the Senior Executive as part of the business planning review. Every six months, DFAT compiles the highest rated risks into a critical risk list. This list is then assessed by the Enterprise Risk Group before it is provided to the Departmental Executive.23 Prior to the Security Branches becoming a division in July 2016, the security risks were channelled through the former Corporate Management Division’s risk register.

2.38 DFAT’s 2015 and 2016 critical risk lists identify high-level critical risks to the department, but did not identify physical security as a high-level risk. Some physical security risks were identified in relation to cyber security in 2015, and DFAT advised that physical security risks in the 2016 critical risk list were sufficiently covered by the Work, Health and Safety and cyber security risks.

2.39 DFAT’s Departmental Security Committee’s terms of reference specifies that it is to ‘assess key security risks and risk mitigation measures and monitor the impact of residual risks on business operations’.

2.40 The Departmental Security Committee meetings have included, as a standing item, a report on security threats and risks. The focus of these reports is largely on politically motivated violence rather than on risks and residual risks for each post. Consideration by the Departmental Security Committee of overseas posts’ residual risks would improve the oversight and acceptance of these security risks.

Recommendation no.2

2.41 To better inform governance and oversight by the Departmental Security Committee, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade:

- develop and maintain a comprehensive database of physical and operational security measures at overseas posts; and

- develop a more consistent framework for assessing security risks for overseas posts.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

2.42 This will enhance work already underway, in particular the progress made to improve security risk assessments.

Does DFAT appropriately manage classified information?

The ANAO identified instances where DFAT had not appropriately managed sensitive and classified information. Further guidance and support to posts would better position them to manage classified material.

2.43 DFAT’s Security Manual provides guidance as to the appropriate protection and classification of information in line with the requirements of the Protective Security Policy Framework.

2.44 The ANAO identified inadequate practices relating to the management of classified information.

2.45 In addition, the ANAO observed instances where material was not appropriately classified in accordance with current DFAT security policy or in line with the requirements of the Protective Security Policy Framework, such as appropriately applying security classification to the metadata for electronic information.

3. Guidance, training and skills

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT’s) arrangements to provide overseas security training, in particular the guidance and training arrangements that prepare and support staff responsible for security at overseas posts.

Conclusion

DFAT’s arrangements to provide overseas security training have been generally effective. DFAT has established an overseas security training framework to support the delivery of training to overseas staff, and staff with dedicated security advisory roles. There are opportunities to further enhance security training and guidance for deployed and specialist security staff, as well as DFAT’s ability to monitor and analyse staff training across posts.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving the recording of security training information to provide assurance that staff receive appropriate security training.

Is appropriate guidance and training provided to staff at post?

DFAT has an overseas security training framework in place to support Australian staff deployed to overseas posts, locally engaged staff, and staff with dedicated security advisory roles. Security training provided to Australian and locally engaged staff is generally effective in supporting their needs at overseas posts, although there are opportunities to enhance the Security Leaders Training for Post Security Officers through practical guidance on the day-to-day security activities undertaken in that role.

3.1 DFAT has three groups of staff overseas requiring security training, these are:

- Australian staff deployed to posts, that require pre-deployment security training;

- post locally engaged staff, who require base level security and post specific training; and

- post security role Australian staff, that require specific pre-deployment training on their security roles at post, such as the Post Security Officer and Regional Security Adviser.

Australian staff deployed overseas

3.2 DFAT’s security training program is delivered annually by the Security Branches division and covers six core courses, including the department’s new starters security awareness course that is completed by all new staff. Both DFAT and attached agency Australian staff deployed to a DFAT post are required to complete the same training requirements for each new long term posting. Training requirements for each staff member is determined on the threat environment for the post to which they are being deployed and the position the staff member is performing at post.

3.3 Table 3.1 outlines the six core overseas security courses delivered to Australian staff.

Table 3.1: DFAT security courses for Australian staff

|

Training course |

Course content |

Mandatory requirement |

|

New Starters Security Awareness |

Covers DFAT and Australian Government security policies and procedures. |

All staff granted a DFAT security clearance of Baseline Vetting and above. |

|

Overseas Security Awareness |

Covers overseas security fundamentals, including DFAT security policies and procedures. |

All long-term postings. Recommended for short term postings. |

|

Personal Security Awareness |

Covers personal safety and risk management, vehicle security, home security, travel security, kidnapping avoidance, defensive techniques and stress management. |

For all long-term postings to locations that meet a specific threat rating, particularly high criminal activity posts. Available and recommended for accompanying family members. Recommended for short-term postings. |

|

Defensive Driving |

Covers advanced driving skills, including driver awareness, observation and risk mitigation skills. |

For long-term postings to locations that have an elevated threat rating for vehicle travel. |

|

Security Awareness in Vulnerable Environments (formerly the Hostile Environment Awareness Training) |

Covers operational and specific threat and risk awareness, cultural awareness in a vulnerable context, close personal protection and emergency first aid. |

For long and short-term postings to high threat, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, and vulnerable environments where staff travel to remote areas, such as Nigeria. |

|

Security Leaders (formerly the Post Security Officers training) |

Covers security policy, compliance and reporting, post security management, risk management, local guard force operations and correct use of post security equipment. |

For Post Security Officers, Senior Administrative Officers and Post System Administrators (where appropriate). |

Source: DFAT.

3.4 Interviews with DFAT staff, who had returned from deployment and undertaken security training prior to 2015, informed the ANAO that the courses are valuable for first time posting but could include more specific information and examples relevant to the roles at post and the corresponding threat environments.24

Locally engaged staff

3.5 Training for DFAT’s 2419 locally engaged staff across its 104 posts is the responsibility of posts. DFAT Canberra provides specialist or additional training to some locally engaged staff with security responsibilities at post, such as guarding25 or armoured vehicle driver training. This training is provided in addition to the training locally engaged staff may receive locally. Additional training is provided either at the request of posts or scheduled by DFAT Canberra. Table 3.2 outlines the locally engaged staff training provided over the past three years, with 27 staff receiving training in 2015–16.

Table 3.2: DFAT Canberra’s locally engaged staff (LES) security training since 2013–14

|

Training course |

Course information |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

LES Security Manager’s Workshop (Canberra) |

Covers principles of security leadership, guard force management, risk management and DFAT physical security systems. |

- |

- |

14 |

|

Advanced Armoured Vehicle Driver Training (Canberra) |

Five day course that covers capabilities and limitations of armoured vehicles, situational awareness, risk, vehicle dynamics and differing terrains. |

- |

- |

6 |

|

Armoured Vehicle Driver training |

Training on the operation of armoured vehicles undertaken at individual posts and delivered by local providers. |

30 |

27 |

7 |

|

Guard training |

Equipment usage, patrolling, pedestrian screening, emergency procedures and standard operating procedures and can be tailored to meet post needs. |

(1 course)a |

67 |

- |

Note a: One course conducted in Port Moresby, but the number of participants could not be provided.

Source: DFAT.

3.6 DFAT piloted two Canberra-based training courses for locally engaged staff in May 2016, where locally engaged staff travelled to Canberra to undertake five days of specialist training. The first course, the ‘LES Security Manager’s Workshop’, is for locally engaged security managers from overseas posts and includes training on security leadership, guard force management, risk management and physical security systems. The second course ‘Advanced Armoured Vehicle Driver Training’ was for post drivers who had armoured vehicle driving duties. The Security Branches division advised that the pilots were a success and will be incorporated into the regular security training schedule. Both post management and interviewed returned staff advised that specialised training provided by DFAT Canberra addresses potential gaps in the training available at post.

3.7 As noted above, DFAT provides ad hoc additional guard training for local security guards employed at overseas posts when requested by post management. Such additional training is to ensure guards, who are trained to the local standards, receive additional training to meet DFAT’s standards. The ANAO identified one request from a post for assistance from DFAT Canberra to transition to a new security guard provider with pre-deployment and site specific training. DFAT was unable to fulfil this request due to ‘other current work pressures, resource constraints and staff absences’ in the Security Branches division.

3.8 The 2419 locally engaged staff at DFAT posts comprises the largest group of staff overseas. There would be merit in DFAT enhancing the arrangements to provide post specific security training and education for locally engaged staff, including local guards, particularly with supplementation training on posts’ standard operating procedures.

Post Security Officers

3.9 The Post Security Officer role is undertaken by the Deputy Head of Mission/Post. The primary focus of the Deputy Head of Mission/Post role is on diplomatic (policy, economic and consular) duties rather than security. DFAT’s decision to have the Post Security Officer role performed by the Deputy Head of Mission/Post therefore signals that security is an important priority at post.

3.10 The Post Security Officer is a critical role in managing the security at overseas posts by undertaking a range of activities such as: delivering staff security briefings; delivering overseas security awareness training; developing and updating Post Security Instructions and procedures; managing and implementing post security measures; and undertaking security risk management and reporting. This underscores the need to ensure they have the knowledge and skills to do the job effectively. While staff performing the Deputy Head of Mission/Post, and by default the Post Security Officer, role are not required to have specific security qualifications, it is important to ensure the Post Security Officer is trained, experienced and supported to respond effectively to risk.

3.11 The DFAT Security Manual provides information on the responsibilities of Post Security Officers. The Security Manual does not provide detail on the specific activities that Post Security Officers are required to perform, or clarify the division of responsibilities between the Post Security Officer and other post security roles, such as the Senior Administration Officer and the Regional Security Adviser. This view was expressed by DFAT staff interviewed during the audit. DFAT staff suggested that a greater level of guidance material for the Post Security Officer role would be valuable for staff performing the role, particularly where they had not performed post security roles previously.26

3.12 The Security Leaders course is the central training course for Post Security Officers, and was updated in 2016. ANAO staff attended the updated training course in September 2016 and observed that the course did not provide specific information about the variety of tasks a Post Security Officer performs at post, information on the security measures in place at posts or detailed guidance on how to undertake maintenance or testing of security measures.27 Finally, it did not reference DFAT’s risk matrix—rather, participants were provided a generic risk matrix.

3.13 Box 2 outlines the suggestions from DFAT staff during the course of the audit to improve the Post Security Officer training.

|

Box 2: Opportunities to improve the Security Leaders course |

|

What specialist security support does DFAT provide posts?

DFAT deploys its Regional Security Advisers to higher threat posts on a risk basis. While DFAT has improved management and support of Regional Security Advisers, these roles would benefit from a formalised training package.

3.14 Since 2006–07 DFAT began deploying Regional Security Advisers to support posts that are assessed to be high threat or where they are located in volatile security environments, such as Iraq and Afghanistan. Regional Security Advisers provide a post with a security specialist resource that are in the same region, and similar time zone, and therefore able to respond to security issues at post quickly—including travelling to a post at short notice.

3.15 The number and location of Regional Security Advisers has expanded over time, with Regional Security Advisers either responsible for a single, high threat post, while others support multiple posts in a region. DFAT deployed two new Regional Security Adviser positions in 2016 to support a further 16 posts.

3.16 Regional Security Advisers are deployed as a post resource, with funding for the position devolved to the post along with management, performance and reporting responsibility. For Regional Security Advisers that have coverage of multiple posts, their ‘home’ post is responsible for Regional Security Advisers funding, management, performance and reporting. DFAT’s 2015 internal review identified that it has been the practice for Regional Security Advisers in some cases to undertake other administrative tasks at post.

3.17 In November 2016, DFAT issued Guidelines and Administration Arrangements to all posts, which outlines the funding, management and performance arrangements, along with when consultation with Security Branches division and other posts is to occur, to ensure the Regional Security Advisers provide adequate support to all posts for which they have responsibility. DFAT would benefit from developing formalised arrangements to ensure desired consultation occurs and that standard expectations and practices are established across the overseas post network.

3.18 The ANAO sought feedback from current Regional Security Advisers on the training and support they receive prior to and during their posting. Their feedback identified a number of opportunities for improvement that are provided in Box 3.

|

Box 3: Opportunities to improve the support for Regional Security Advisers |

|

3.19 DFAT is trialling new arrangements and support mechanisms with the newly deployed Regional Security Advisers and has established Regional Security Adviser conferences commencing in December 2016, which will enable Regional Security Advisers to exchange information and develop skills.

Are appropriate arrangements in place to train and support Canberra based security staff?

DFAT has commenced activities to enhance the policies and procedures to train Canberra-based security staff. Further improvements could be made to the training and guidance of specialist security staff undertaking security inspections of posts.

3.20 The 2015 internal review of the Security Branches division noted that the variable performance across all functions of the Security Branches division pointed to a need for standard operating procedures. In mid‐2016, DFAT advised that this recommendation was ‘partly met’, including through the development and testing of a standard threat assessment template, and the development of standard operating procedures. DFAT advised in November 2016, that the development of standard operating procedures and technical manuals is underway.

3.21 The ANAO observed that the training for staff in the Security Branches division undertaking security inspections is limited. New Overseas Security Advisers usually undertake one inspection with an experienced team member before undertaking overseas security inspections individually.28 The ANAO observed that, given the absence of standardised guidance, DFAT’s approach does not enable sufficient knowledge transfer or on-the-job training to support a consistent quality of overseas security inspections.

3.22 There are no standard operating procedures or guidance in place for staff undertaking security inspections. As discussed in Chapter 2, there is variation in the quality of recent security inspection reports and the security risk assessments that underpin recommendations. This indicates the need for better quality control and management oversight of overseas security inspections, and in particular the security risk assessments.

Does DFAT monitor the delivery of overseas security training?

The information systems used to record the department’s security training information do not provide management with informative reporting and assurance that staff deployed overseas have the appropriate security training. Improvements in DFAT’s ability to monitor and analyse security training would assist DFAT in managing risk and provide more meaningful governance and oversight.

3.23 DFAT staff register for security training courses using the human resource system. Attached agency staff and family dependents do not have access to the DFAT human resource system and instead contact the Security Training Section to register for security training courses, and their attendance is recorded on a separate spreadsheet.

3.24 The human resource system cannot produce informative reporting on staff attendance at security training courses, such as the number of attendees for courses, details of where the attendees were being posted, courses completed and dates of completion. Obtaining security training information on DFAT staff requires a manual search of individuals’ training records in the system, rather than being able to search and generate reporting on the consolidated data set.29 Due to the limitations of the system used to record training information and data, DFAT is unable to:

- identify staff requiring additional training where the threat environment of a post changes;

- identify which posts require the most training;

- analyse the period between training being completed and postings; and

- monitor the differences in training for short or long term postings.

3.25 Developing mechanisms to better search and generate consolidated reporting on the training information and data would provide assurance that staff deployed overseas have the appropriate security training for their post. Such reporting would also enable DFAT to identify training gaps, or changes in training needs at particular posts and inform the forward security training program.

Recommendation no.3

3.26 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade develop mechanisms to provide assurance that staff receive the required security training for their posting, and to inform future planning and improvements to the security training program.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed.

4. Overseas security arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) specification, selection and maintenance of security arrangements at overseas posts, along with crisis and business continuity planning for overseas posts.

Conclusion

DFAT has arrangements in place to specify overseas physical security measures and select and deploy the measures to posts. The manner in which these measures have been deployed and managed has not been effective in all cases. Improving the specifications and guidance for all physical and operational security measures at posts would help mitigate security risks. DFAT has in place overseas security inspection arrangements to provide assurance on the effectiveness of security measures in place at posts. The effectiveness of these inspections could be enhanced through a centrally coordinated process for planning and recording security inspections.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving the process of selecting and deploying security measures to overseas posts, enhancing the coordination of overseas security inspections, and strengthening the management of deployed security measures.

Has DFAT developed specifications for overseas security measures?

DFAT’s arrangements overseas are based on the ‘security-in-depth’ security management principle. DFAT has largely established minimum specifications for physical security measures deployed to posts. There is limited guidance to overseas posts on operational security measures, such as guarding standards for different threat environments. There would be benefit in DFAT providing further guidance on these issues.

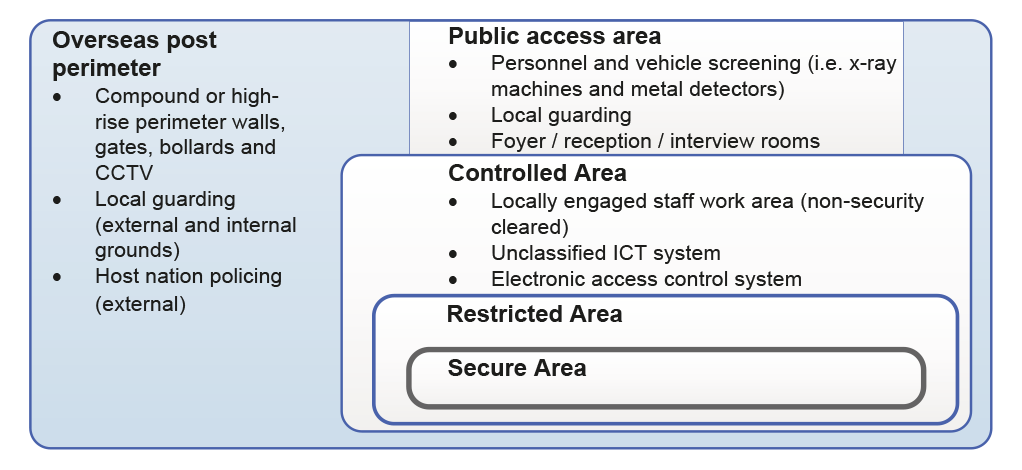

4.1 Figure 4.1 illustrates DFAT’s application of security-in-depth principles (including examples of security measures deployed) at overseas posts, where layers of security measures are applied to provide progressive protection that correspond to the value of the asset or information requiring protection.

Figure 4.1: DFAT’s application of security-in-depth at overseas posts

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT information.

Standards for physical security measures

4.2 DFAT first established minimum specifications for physical security measures in 2009. These specifications are outlined in two types of security briefs; one for ‘green field sites’ (where DFAT is building the overseas post from the ground up) and one for high rise tenancies (where DFAT does not own the building). DFAT has established specifications for security measures, which are translated into a brief for specific overseas posts projects (for new or refurbished overseas posts) based on threat analysis and risk assessment. The brief includes the security measures to be deployed and the standards for their construction or deployment. If there are practical limitations associated with the site that require the specifications to be altered, these changes are reflected in the project brief.

4.3 The Security Branches division and the Overseas Property Office translate the security project brief into a documented design brief based on Australian building standards that can be understood and delivered by overseas contractors. As construction is undertaken in overseas environments, and by foreign nationals, DFAT sanitises the detailed security specifications in the documentation provided to contractors. During this process, the Security Branches division is responsible for threat and security risk assessment and mitigation, while the Overseas Property Office is responsible for the design, selection, procurement and implementation of physical security construction components and items.

4.4 In response to a recommendation from the 2015 Review of Diplomatic Security, DFAT updated and developed specifications for several of the security measures throughout 2016.

Guarding

4.5 Guards control public access, respond to physical security incidents and operate equipment such as walk-through metal detectors. Overseas posts are responsible for contracting their own guarding services and determining the standards and operating procedures of those guards. The overseas posts ANAO visited during the audit used local guards. These were supplied through the host government or contracted by the post.

4.6 There is limited guidance to overseas posts on establishing appropriate guarding standards for different environments. The ANAO observed differing practices between the posts visited during the audit. DFAT should put in place measures to assure itself that consistent processes and practices are being followed by post guards. DFAT advised the ANAO that a priority component of the new Security Framework is to develop Security Guard Management Guidelines and Private Military and Security Company Management Guidelines.

Does DFAT effectively coordinate the deployment of security measures to overseas posts?

DFAT identifies the security measures to be deployed to overseas posts based on an operational threat assessment and a security risk assessment. There is no documented end-to-end process or procedure connecting the activities that inform the deployment of security measures, which are undertaken by different sections in the Security Branches division. This reduces DFAT’s effectiveness in determining the appropriate security measures to be deployed to posts.

4.7 As noted above, in some cases there are practical limitations associated with the overseas environment posts operate in that require alternative specifications for security measures to be implemented. For example, during the establishment of a post, DFAT advised that it was not possible to install the ballistic resistant wall as specified due to the building’s floor load rating. If the higher standard was required then a new building (with higher floor load rating) would be required. In this case, buildings with a higher floor load rating were not commercially available in that location and necessitated the installation of the ballistic resistant wall to a lower standard.