Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Procurement of My Health Record

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- My Health Record (MHR) is a national public system. It aims to improve the availability and quality of health information, and the coordination and quality of health care.

- It is estimated that $2 billion has been invested in the MHR system.

- Procurement and contract management relating to large public-interfacing IT systems involve unique and elevated risks.

Key facts

- Approximately 23.8 million Australians have a My Health record.

- Accenture has been contracted as the National Infrastructure Operator (NIO) of MHR since June 2012.

- The Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) has been responsible for MHR since 2016.

- ADHA varied the NIO contract with Accenture eight times between 2018 and 2023.

What did we find?

- ADHA’s procurement and contract management of the MHR NIO contract has been partly effective.

- ADHA’s governance framework for procurement and contract management is largely fit for purpose.

- ADHA’s management of the NIO contract has been partly effective.

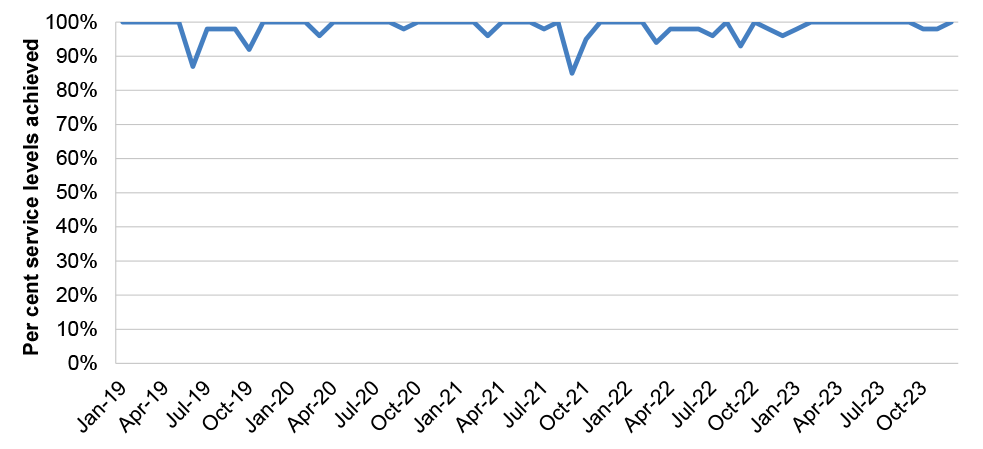

- ADHA has not conducted procurements of the MHR NIO effectively.

What did we recommend?

- There were 13 recommendations to ADHA. They related to management of risk, contract variations and records; review of contractor deliverables; assurance over system architecture documentation; procurement planning and decision-making; probity policies and practices; and AusTender reporting.

- ADHA agreed to 12 recommendations and agreed in principle to one recommendation.

$699 m

was added to the MHR NIO contract with Accenture through contract variations since 2012.

72%

of ADHA expenditure on MHR national infrastructure service providers (2018–19 to 2022–23) was to Accenture.

55%

of ADHA business area reviews of Accenture monthly operations reports were conducted in accordance with requirements in 2023.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. My Health Record (MHR) is a national public system for making health information about a healthcare recipient available for the purposes of providing healthcare to the recipient.1 The My Health Records Act 2012 (MHR Act) states that the goals of MHR are to overcome fragmentation and improve the availability and quality of health information; reduce adverse medical events and the duplication of treatment; and improve the coordination and quality of health care provided by different healthcare providers.2

2. The Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) was established as a corporate Commonwealth entity in 2016, at which time it became MHR system operator.

3. MHR ‘national infrastructure’ is comprised of the IT systems and support enabling the flow of information in and out of the MHR system. The Department of Health and Aged Care and ADHA used IT supplier contracts to implement MHR national infrastructure. The largest contract is for the National Infrastructure Operator (NIO), which is responsible for operation, maintenance, support and integration of MHR national infrastructure.

4. The NIO contract was first executed with Accenture Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (Accenture) on 27 June 2012 for a total value of $47 million to 30 June 2014. As at February 2024, arrangements with Accenture totalled $746 million for MHR NIO services between 2012 and 2025.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The Australian Digital Health Agency reports that approximately 23.8 million Australians had a My Health record as at March 2024.3 It is estimated that $2 billion has been invested in the My Health Record system.4

6. There has been parliamentary interest in government procurement.5 Procurement of large public IT systems can raise risks relating to obsolescence, security and interoperability. This audit provides assurance to the Australian Parliament about whether ADHA has effectively managed MHR procurement.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Digital Health Agency’s procurement and contract management of the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Does ADHA have a fit-for-purpose governance framework for contract management and procurement?

- Has ADHA managed the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator contracts effectively?

- Has ADHA conducted procurements of the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator effectively?

Conclusion

9. ADHA’s procurement and contract management of the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator has been partly effective. Effectiveness has been diminished by poor procurement planning and failure to observe core elements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

10. ADHA’s governance framework for contract management and procurement is largely fit for purpose. There are policies and guidance for procurement and contract management, although probity guidance could be improved. Management and oversight arrangements for procurements and contract management are largely appropriate. Internal audit coverage of procurement has been limited.

11. ADHA’s management of the National Infrastructure Operator contract has been partly effective. The identification and assessment of commercial risk has been limited. The effectiveness of day-to-day administration of the contract is diminished by contract management planning that is not fully fit for purpose. Contract variations within the existing contract term have been made with insufficient assessment of risk, consideration of materiality and justification of value for money. The management of contract performance has not utilised all available levers under the contract.

12. ADHA has not conducted procurements of the National Infrastructure Operator contract effectively. ADHA’s planning and decisions about how to approach the market for the contract in 2019 and 2022 were deficient. For both sole source limited tender procurements, ADHA’s conduct of limited tender processes under Division 1 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (including demonstrating value for money, managing probity and public procurement reporting) was also deficient.

Supporting findings

Governance framework for procurement

13. ADHA provides procurement and contract management training to staff and has policies and guidance for procurement and contract management. Although there are policies and guidance, these are not always reviewed in accordance with requirements. There are policies relevant to managing conflicts of interest in procurement and contract management, although instructions are inconsistent across policy documents. There is a policy relevant to managing gifts and benefits which lacked specificity but has been improved. Chief Executive Officer (CEO) gifts and benefits declarations are not always timely. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.21)

14. Business areas are responsible for procurement and contract management and are supported by a central procurement area. The board approves contracts above a certain value threshold and delegates the power to enter into a contract to the CEO for other contracts. There are CEO authorisation instruments to allow officials to conduct procurements and enter into contracts. From April 2021 there was regular reporting to the board on complex and high-risk procurement. The internal audit program has considered contract management but has had limited coverage of procurement. An Audit and Risk Committee has included procurement issues in its reporting to the board but has not provided advice about the sufficiency of controls over procurement risks. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.30)

Contract management

15. In addition to a quarterly strategic risk assessment which includes consideration of My Health Record and the National Infrastructure Operator, risk assessments specifically related to ADHA’s commercial relationship with Accenture were conducted in 2016, 2019, 2020 and 2022. The quality of the risk assessments varied. Although a 2021 contract management plan assessed the overall risk for the National Infrastructure Operator contract as ‘medium’, it provided no information to justify this overall rating, no indication if this risk assessment exceeded its risk appetite, and no description of or treatments for specific risks. ADHA did not re-assess contract risk on five of the six occasions when the contract with Accenture was varied during an existing contract term between 2018 and February 2024. ADHA assessed risk on two occasions when the contract with Accenture was varied through a procurement, although the quality of risk assessment for one procurement was poor. The terms and conditions of the National Infrastructure Operator contract address a range of commercial and security risks. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.16)

16. The effectiveness of contract administration has been diminished by the following.

- There is a National Infrastructure Operator contract management plan. The plan has not been reviewed as required and does not contain some of the required information. There are no instructions to officials about how and when to assess contract risk.

- The National Infrastructure Operator contract with Accenture was amended eight times between January 2018 and February 2024 largely to fund My Health Record system enhancements, including six amendments (valued at $54 million) executed during the term of the existing contract. For the six contract amendments, ADHA did not document value for money considerations.

- ADHA did not review the contractor’s performance when it exercised an option to extend the contract.

- ADHA held strategic and operational meetings with the contractor, but these were not always at the specified frequency. Not all specified meeting types took place and some meeting types took place that were not specified.

- Officials managing the National Infrastructure Operator contract did not adhere to the ADHA’s records management policies. (See paragraphs 3.17 to 3.34)

17. Although there is evidence of ADHA conducting reviews and requiring some National Infrastructure Operator deliverables to be resubmitted, ADHA has not reviewed contract reporting deliverables as required. Contract and contract management plan provisions to support performance management have rarely or never been used (benchmarking, annual performance reviews and audits) or have not been used as planned (issues monitoring). A request for updated My Health Record system architecture in August 2019 in preparation for approaching the market for the National Infrastructure Operator in June 2020 coincided with the commencement of a dispute between ADHA and Accenture about system architecture documentation. The dispute was not resolved until March 2023. The practice of advance payment for services before delivery weakens ADHA’s leverage in managing performance. ADHA has invoked contract provisions that penalise the contractor for failing to meet certain service levels. (See paragraphs 3.36 to 3.59)

Procurement processes

18. Planning and approach to market processes for the 2019 and 2022 procurements of the National Infrastructure Operator were deficient.

- Procurement plans were not approved before procurement decisions were made.

- Risk associated with a direct source limited tender was not well assessed for the 2019 procurement but was assessed for the 2022 procurement.

- For the 2019 and 2022 procurements, ADHA justified not going to open market using limited tender conditions listed in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, however there were weaknesses in how conditions were justified, approved, implemented and reported. In particular, the use of paragraph 10.3b of the CPRs (‘when, for reasons of extreme urgency brought about by events unforeseen by the relevant entity, the goods and services could not be obtained in time under open tender’) was inappropriate.

- In making procurement planning decisions, relevant information (including performance issues) was not appropriately considered by the decision-maker. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.36)

19. Cost and other factors, including Accenture’s experience as the National Infrastructure Operator, were considered in the decision to award a contract ‘extension’ to Accenture in 2019 and 2022. However, the accountable authority made the decision without fully considering Accenture’s performance history and ADHA did not document a clear value for money assessment for either procurement. Approvals were given by officials with appropriate authority and were appropriately documented. The approach to declaring potential conflicts of interest did not comply with ADHA policy and program-specific probity obligations were unclear. ADHA partly complied with AusTender reporting requirements. (See paragraphs 4.40 to 4.68)

Recommendations

20. This report makes 13 recommendations to ADHA.

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.11

Australian Digital Health Agency review risks associated with procurement and management of My Health Record.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.20

Australian Digital Health Agency update its National Infrastructure Operator contract management plan:

- annually, in accordance with review requirements;

- to provide sufficient guidance on key contract management elements such as termination and step-in, issues management and escalation;

- to incorporate guidance on key contract provisions such as dispute resolution, subcontracting, benchmarking and annual review of contractor performance; and

- to provide guidance and instructions to officials on how and when to identify, assess and manage National Infrastructure Operator contract risks.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.26

Australian Digital Health Agency ensure that:

- decisions to expend money through a contract variation document whether the variation represents a ‘minor’ change, and the value for money of the variation; and

- it reviews performance and deliverables prior to exercising a contract extension option.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.35

The Australian Digital Health Agency ensure that records created as part of the National Infrastructure Operator contract are stored in accordance with its information governance framework.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.46

The Australian Digital Health Agency document its approach to reviewing and reporting deliverables, put in place arrangements to ensure that it reviews National Infrastructure Operator contract reports and deliverables as required, and establish appropriate controls to provide assurance that reviews are occurring.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.50

The Australian Digital Health Agency ensure that National Infrastructure Operator contract arrangements that follow the expiry of the existing contract in June 2025 clearly specify the maintenance and provision of system architecture documentation and provide appropriate assurance arrangements for their timely provision.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.8

In anticipation of the expiry of the National Infrastructure Operator contract on 30 June 2025, Australian Digital Health Agency:

- publish a procurement plan on AusTender that provides reasonable notice to the market about the expiry of the contract; and

- prepare and endorse an internal procurement plan.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.35

The Australian Digital Health Agency implement controls to ensure that, in making procurement decisions, relevant information (including legal advice, and any past and ongoing disputes and performance issues with a supplier) is incorporated into the value for money assessment.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 4.37

The Australian Digital Health Agency ensure limited tender processes do not commence before the limited tender procurement approach has been approved by the relevant decision-maker, including (if applicable) consideration by the decision-maker of the specific conditions justifying limited tender.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 10

Paragraph 4.38

For the procurement of a National Infrastructure Operator following the expiry of the National Infrastructure Operator contract on 30 June 2025, Australian Digital Health Agency conduct an open tender in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed in principle.

Recommendation no. 11

Paragraph 4.46

The Australian Digital Health Agency, in approving expenditure through a procurement, ensure that decisions are supported by a clear value for money assessment, which considers the financial and non-financial costs and benefits of the procurement.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 12

Paragraph 4.60

Australian Digital Health Agency:

- ensure program-specific probity frameworks are consistent with other agency policies; and

- establish assurance processes over the declaration of interests in procurements to ensure that positive declarations are made as required under Australian Digital Health Agency’s conflict of interest policy and National Infrastructure Modernisation probity framework.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 13

Paragraph 4.69

The Australian Digital Health Agency establish controls to ensure that:

- all contracts and contract variations are reported accurately on AusTender within the required timeframes; and

- in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, for each contract awarded through limited tender, a written report is prepared that includes the value, a statement indicating the circumstance and conditions that justified the use of limited tender, and a demonstration of how the procurement represented value for money in the circumstances.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to ADHA. ADHA’s summary response to the audit is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

As the Report highlights, the My Health Record System (MHR) is a national public system supporting coordination and quality clinical decision making and provides health information for 23.7 million Australians where and when they need it.

MHR has been operating successfully for over a decade – delivering secure, reliable health information, with choice and privacy firmly in the hands of Australians. The Agency welcomes the key Report finding that governance frameworks and contract management approaches for MHR are largely fit for purpose.

During the pandemic, when Australian communities were at highest risk, MHR was upgraded to provide rapid access to COVID test results and vaccination certificates as part of the national effort to protect Australians and support freedom of movement. During this period system stability and reliability were priorities in procurement approaches taken.

The Agency accepts the ANAO’s recommendations on strengthening approval and review processes and record keeping across the procurement and contract management lifecycle and has significantly augmented these areas over the last three years. This includes successful complex IT infrastructure modernisation through competitive procurements that have reduced single vendor dependency. Further modernisation work is underway to deliver greater health information sharing and more connected care across the health system.

22. An extract of the proposed report was provided to Accenture Australia Holdings Pty Ltd. Accenture’s full response is provided at Appendix 1.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

23. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

1. Background

Introduction

Australian Digital Health Agency

1.1 The Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) was established in January 2016 as a corporate Commonwealth entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Establishing the Australian Digital Health Agency) Rule 2016 (the ADHA Rule). ADHA is responsible for supporting digital health initiatives including My Health Record, telehealth6 and electronic prescriptions.7 The functions of ADHA include to coordinate and implement a National Digital Health Strategy. On 22 February 2024 ADHA released the National Digital Health Strategy 2023–2028 to guide the development of digital health products and services. 8

1.2 ADHA is jointly funded by the Australian Government and the states and territories. In 2023–24 ADHA’s expenditure was estimated to be $352 million. In the 2023–24 federal Budget ADHA received $413.3 million over two years for My Health Record (MHR) operations and initiatives and $325.7 million over four years for investment in ADHA’s capabilities. In the 2024–25 federal Budget a further $57.4 million was allocated to continue initiatives under the Health Delivery Modernisation Program9 and to update MHR. As at 30 June 2023 ADHA had 412 staff located in Brisbane, Sydney and Canberra.

1.3 The ADHA Rule establishes the ADHA board (the board) as the accountable authority and sets out the functions and powers of the board and Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The CEO is responsible for the day-to-day administration of ADHA and takes directions from the board.

My Health Record

1.4 My Health Record is a national public system for making health information about a healthcare recipient available for the purposes of providing healthcare to the recipient. The MHR system was established by the Department of Health and Ageing in 2012.10 Section 3 of the My Health Records Act 2012 (MHR Act) states that the goals of MHR are to overcome fragmentation and improve the availability and quality of health information; reduce adverse medical events and the duplication of treatment; and improve the coordination and quality of health care provided by different healthcare providers. Consumers and healthcare providers can access and upload clinical and Medicare11 documents to MHR.12

1.5 As the MHR system operator since July 2016, ADHA is responsible for functions specified in section 15 of the MHR Act. These include maintaining a service that allows information in different repositories to be connected to registered health care recipients and facilitating the retrieval of such information when required. Auditor-General Report No. 13 2019–20 Implementation of the My Health Record System concluded that the implementation of MHR was largely effective and made five recommendations, all of which were agreed to by ADHA.13

1.6 From 2020 ADHA delivered a range of MHR-related measures to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic including: provision of pathology reports and results;.access to an immunisation history statement and proof of immunisation; and a COVID-19 dashboard showing immunisation, medicines, allergies and adverse reactions. ADHA reported that as at March 2024 there were more than 23.8 million My Health records (of which 98 per cent contained data) and over 1.2 billion uploaded documents.14

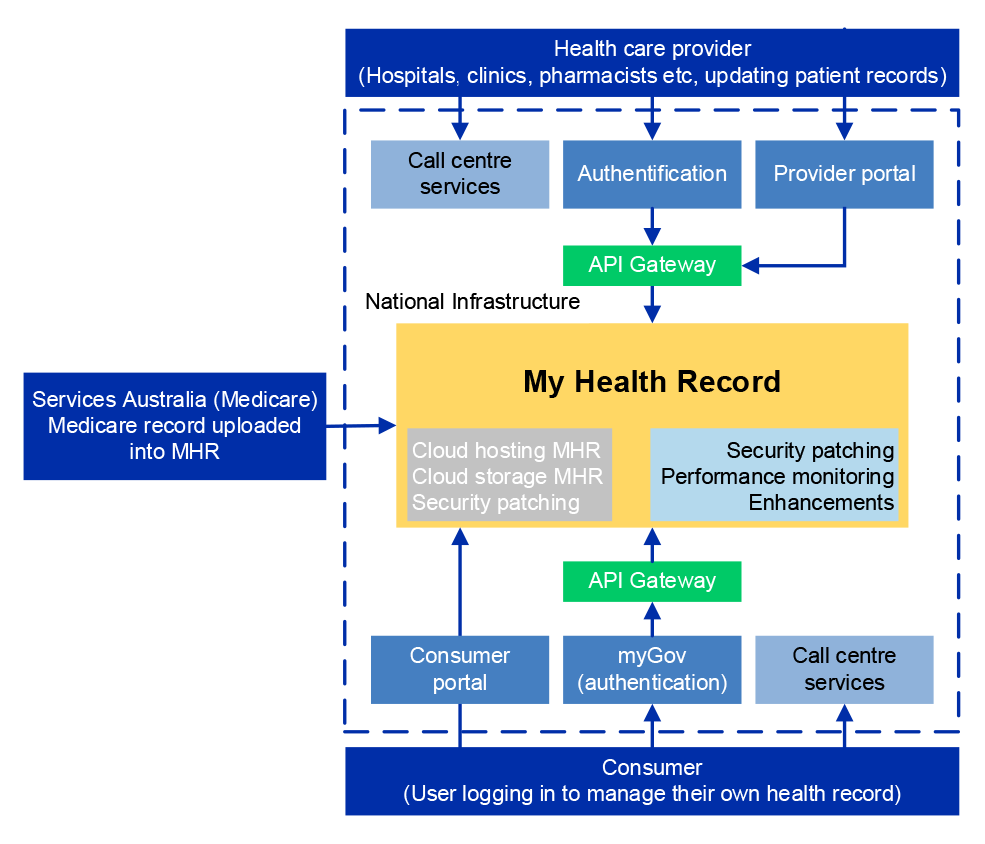

1.7 The MHR ‘national infrastructure’ is comprised of the IT systems and supports enabling the flow of information in and out of the MHR system. These include an Application Programming Interface (API) gateway to integrate the different software used by healthcare providers and consumers to connect to the MHR system (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: My Health Record national infrastructurea

Note a: Other related service components include hosting services, maintenance and support, the National Authentication Service for Health, the Health Identifiers Service and the National Clinical Terminology Service.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Procurement of My Health Record

1.8 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), the Finance Minister issues the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which govern how entities buy goods and services. ADHA has been subject to the CPRs since 1 January 2018.15

1.9 The Department of Health and ADHA used IT supplier contracts to implement the MHR. The largest contract is for the National Infrastructure Operator (NIO). The NIO contract was first executed with Accenture Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (Accenture) on 27 June 2012 for a total value of $47 million to 30 June 2014.

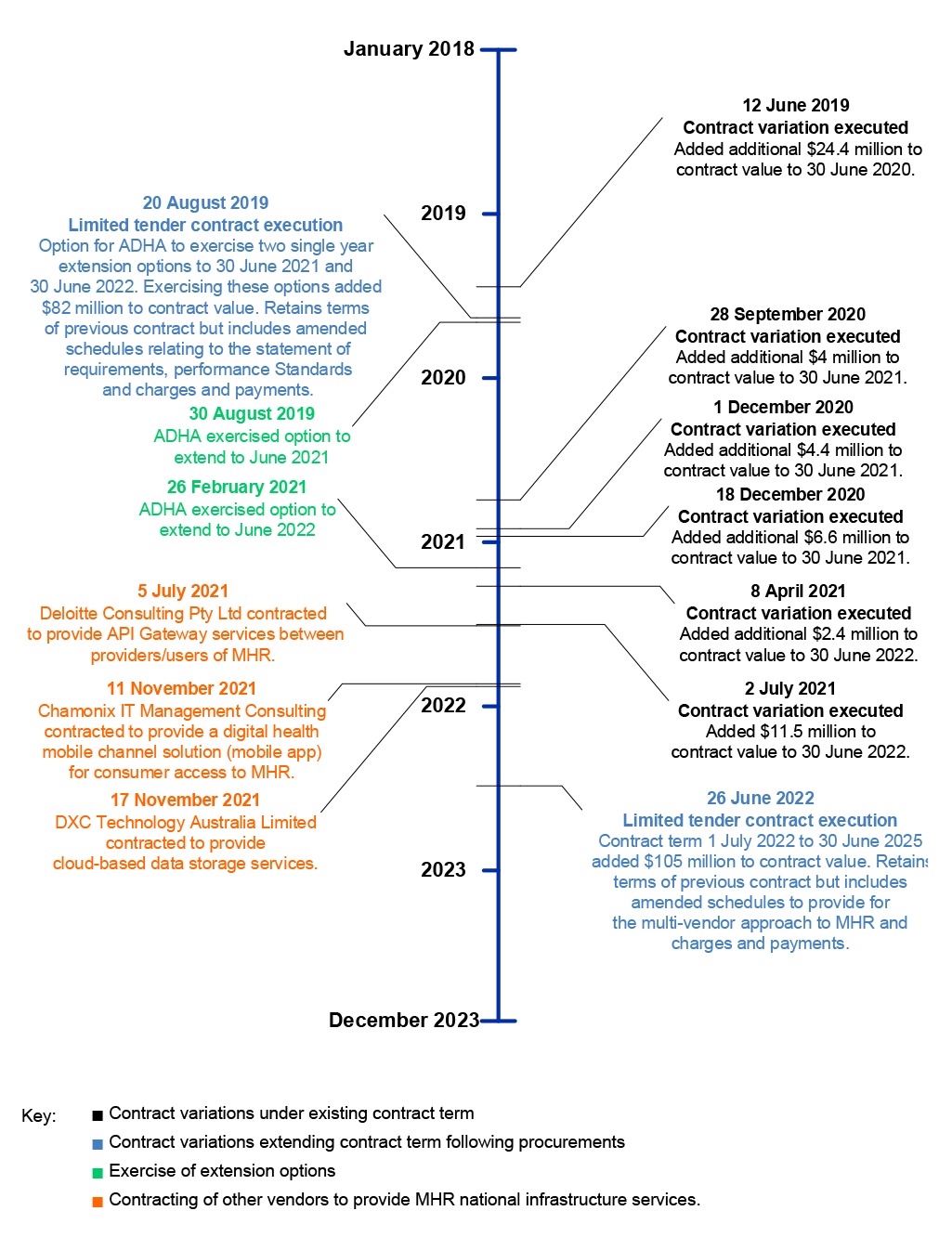

- The 2012 contract was due to expire on 30 June 2014, with an option to extend for three further periods of two years each (that is, to 30 June 2020). In 2014, the Department of Health exercised the first extension option to 30 June 2016, increasing the contract value by $49 million. In 2015, the Department of Health exercised the second extension option to 30 June 2018, increasing the value by $87 million. In 2017, ADHA exercised the third extension option to 30 June 2020, increasing the value by $159 million. Between 2012 and 31 December 2017, an additional $164 million was added through 21 other contract variations under the existing term of the contract, bringing the total cumulative value of the contract to $506 million as at 31 December 2017.

- As the maximum aggregate term of eight years under the 2012 contract was due to conclude on 30 June 2020, ADHA undertook a procurement process in 2019. The 2019 procurement was awarded to Accenture through a direct source limited tender, and was implemented through an amendment to the 2012 contract. The 2019 amendment included an option to extend the 2012 contract for two periods of one year each (that is, to 30 June 2022). On exercising these options, $82 million16, was added to the contract, bringing the total cumulative value of the contract to $588 million.

- As the additional aggregate term of two years was due to conclude on 30 June 2022, ADHA undertook a second procurement process in 2022. The 2022 procurement was awarded to Accenture through a direct source limited tender, and was implemented through a further amendment to the 2012 NIO contract. The 2022 amendment included an additional term of three years (that is, to 30 June 2025), and added $105 million, bringing the total cumulative value of the contract to $693 million.

- Between January 2018 and 31 December 2023, ADHA varied the contract amount and conditions within the existing contract term on six other occasions. The net amount added to the contract totalled $53 million across the six variations, bringing the total cumulative value of the contract to $746 million.

1.10 The audit covers the management of contractual arrangements with Accenture from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2023. Figure 1.2 shows NIO contract extensions and variations since 1 January 2018, as well as contracting to other vendors to provide some national infrastructure services from July 2021.

Figure 1.2: NIO contract variations, January 2018 to December 2023

Source: ANAO analysis of NIO contracts.

1.11 In July 2019 ADHA commenced the National Infrastructure Modernisation (NIM) Program. Advice to the board stated the purpose of the NIM Program was to ‘manage the activities, timeframes and resourcing required to replace the NIO contract’ and to ‘oversee the delivery of the capabilities, solutions, engagement and operationalisation of modernisation of the infrastructure underpinning the MHR system’. The 2022 contract amendment with Accenture allowed for a ‘multi-vendor approach’ to the MHR NIO. In 2021 ADHA contracted vendors other than Accenture to provide some NIO services which were either previously provided by Accenture under the 2012 NIO contract or were new services (Table 1.1).17

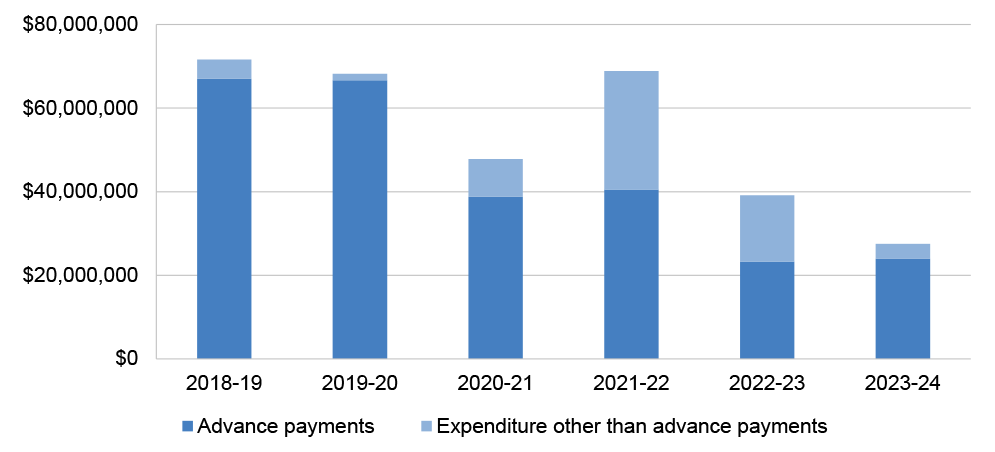

1.12 Between 2018–19 and 2022–23, MHR national infrastructure-related expenditure totalled $408.2 million, of which $295.6 million (72 per cent) were paid to Accenture as the NIO.

Table 1.1: MHR national infrastructure provider expenditure, 2018–19 to 2022–23 ($million)

|

|

Services |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

2021–22 |

2022–23 |

Total |

|

Accenture |

NIO |

71.6 |

68.2 |

47.8 |

68.8 |

39.2 |

295.6 |

|

Datacom Connect Pty Ltda |

Call centre |

28.1 |

4.5 |

5.5 |

14.0 |

11.9 |

64.0 |

|

DXC Technology Australia Limitedb |

Cloud storage |

– |

– |

– |

5.0 |

13.4 |

18.4 |

|

Deloitte Consulting Pty Ltdc |

API gateway |

– |

– |

– |

2.9 |

13.6 |

16.5 |

|

Chamonix IT Management Consultingd |

My Health app |

– |

2.2 |

3.0 |

4.6 |

3.8 |

13.7 |

|

Total |

|

99.7 |

74.9 |

56.3 |

95.3 |

82.0 |

408.2 |

Note a: AusTender contract notice CN3589159. Since 27 October 2023 Services Australia has provided call centre services under a separate contract with ADHA (CN4027950).

Note b: AusTender contract notice CN3843536.

Note c: AusTender contract notice CN3791712.

Note d: AusTender contract notice CN3827223. Expenditure in 2019–20 and 2020–21 relates to healthcare information provider service product development and support services.

Source: ANAO analysis of ADHA purchase orders.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.13 The Australian Digital Health Agency reports that approximately 23.8 million Australians had a My Health record as at March 2024.18 It is estimated that $2 billion has been invested in the My Health Record system.19

1.14 There has been parliamentary interest in government procurement.20 Procurement of large public IT systems can raise risks relating to obsolescence, security and interoperability. This audit provides assurance to the Australian Parliament about whether ADHA has effectively managed MHR procurement.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.15 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Digital Health Agency’s procurement and contract management of the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator.

1.16 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Does ADHA have a fit-for-purpose governance framework for contract management and procurement?

- Has ADHA managed the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator contracts effectively?

- Has ADHA conducted procurements of the My Health Record National Infrastructure Operator effectively?

1.17 The audit scope includes ADHA’s contract management and procurement processes for MHR NIO contracts with Accenture since 2019. The audit scope did not include the effectiveness of other MHR procurements or of MHR implementation more broadly.

Audit methodology

1.18 The audit methodology included:

- visits to ADHA offices and meetings with entity officials;

- meeting with Accenture;

- review of ADHA data, documentation, policies and procedures;

- review of AusTender records; and

- examination of Accenture reporting to ADHA.

1.19 The audit was open to public contributions. The ANAO did not receive any contributions.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $759,400.

1.21 The team members for this audit were April Howley, Kai Swoboda, Thea Ingold, Callum Mann, Katiloka Ata, Bezza Wolba, Jade Koay, Ketan Doshi and Christine Chalmers.

2. Governance framework for procurement

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) has a fit-for-purpose governance framework for contract management and procurement.

Conclusion

ADHA’s governance framework for contract management and procurement is largely fit for purpose. There are policies and guidance for procurement and contract management, although probity guidance could be improved. Management and oversight arrangements for procurements and contract management are largely appropriate. Internal audit coverage of procurement has been limited.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO suggested three opportunities for improvement relating to ensuring directions with regard to probity in procurement guidance are consistent; improving policies and practice in relation to the declaration of gifts and benefits; and increasing internal audit coverage of procurement.

2.1 A sound governance framework helps ensure that procurements and contract management are undertaken effectively and ethically, achieving value for money outcomes. The Australian Government Contract Management Guide notes that contract governance includes systems and processes for decision making; and oversight arrangements and reporting.21

Are there fit-for-purpose procurement and contract management policies and guidance?

ADHA provides procurement and contract management training to staff and has policies and guidance for procurement and contract management. Although there are policies and guidance, these are not always reviewed in accordance with requirements. There are policies relevant to managing conflicts of interest in procurement and contract management, although instructions are inconsistent across policy documents. There is a policy relevant to managing gifts and benefits which lacked specificity but has been improved. CEO gifts and benefits declarations are not always timely.

Accountable Authority Instructions

2.2 Accountable Authority Instructions assist accountable authorities in meeting their general duties under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and establishing appropriate internal controls for their entity. The Department of Finance (Finance) provides guidance on Accountable Authority Instructions.22

2.3 Between June 2018 and April 2023, ADHA had five versions of Accountable Authority Instructions. The June 2018 and August 2018 Accountable Authority Instructions were approved by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) instead of the accountable authority (the board). The April 2021, April 2022 and April 2023 Accountable Authority Instructions were approved by the Chair of the board.

2.4 The three versions of the Accountable Authority Instructions issued between April 2021 and April 2023 outlined the key duties and responsibilities of officials under the PGPA Act. The three versions state that officials must comply with the PGPA Act, Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) and Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs).

Procurement and contract management policies and guidance

2.5 In May 2021 ADHA published procurement policies, guidance and templates on its intranet under the ‘BuyRight’ framework.23 The linked policies included: a procurement policy (approved on 2 August 2018 and revised on 13 December 2023); a procurement manual (September 2018)24; a procurement complaints handling policy and procedure (September 2020); and other specific procurement guidance (such as ‘How to develop performance measures’ (August 2022), and ‘How to achieve value for money’ (August 2022)). BuyRight guidance for contract managers outlined the steps involved in managing a contract including contract administration, roles and responsibilities, risk assessments and contract extensions. The coverage of ADHA’s contract management guidance is consistent with the Australian Government Contract Management Guide, except that it does not provide information about the legislative framework, using advisors and unintentional contract variations through conduct. In December 2021 ADHA developed a policy and procedure to manage administrative approvals, financial approvals and board reporting for medium to high-risk procurement and contracts.

2.6 The August 2018 procurement policy (to be reviewed by 31 May 2019), September 2018 manual (to be reviewed by 31 May 2019), September 2020 complaints handling policy and procedure (each to be reviewed by 20 September 2021), and December 2021 medium to high-risk procurement and contract management policy and procedure (to be reviewed by 1 December 2022) were not reviewed in accordance with review requirements, despite changes to the CPRs during the period. In December 2023 ADHA completed a review of policies which identified that 59 documents had not been reviewed in line with specified review dates.

2.7 ADHA’s contract management guidance provides that ‘generally’ a contract management plan should be developed for procurements over $10,000. A ‘contract classification guide’ (October 2019) assists ADHA staff to classify contracts to ‘identify a suitable level of contract management planning’. Contracts are classified as complex/strategic under this framework based on factors including value ($1 million or more), strategic importance to ADHA and nature of contract deliverables. A September 2023 internal audit report on contract management practices, which examined four contracts25, found that ‘interviewed contract managers generally demonstrated sufficient level of awareness of the Agency’s contract management requirements’ and made four recommendations to improve contract management governance, including to change the threshold for developing a contract management plan. ADHA agreed with the recommendations and intended to address them by March 2024. In May 2024 ADHA advised the ANAO that implementation was ongoing and recommendations would be completed between 30 May 2024 and 30 September 2024.

2.8 There are separate contract management plan templates for routine/transactional contracts and strategic/complex contracts. For contracts classified as strategic/complex, it is mandatory for staff to use the relevant contract management plan template. The strategic/complex template covers: delegates, roles and responsibilities, key stakeholders and stakeholder communication, conditions of the contract, subcontracting arrangements, payment conditions, deliverables, milestones, key performance indicators, performance monitoring, supplier’s obligations, compliance requirements, transition arrangements, reporting requirements, audit requirements, contract meetings, risk assessment and issues management, contract review, dispute resolution, contract termination and contract renewal or extension. The template states that, depending on the nature and complexity of the contract, a probity plan might be attached. The template does not cover conflict of interest arrangements.

2.9 In March 2022 ADHA developed the ‘Information Technology Support Management framework’ to support the move to a multi-vendor environment (see paragraph 3.29). The purpose of the framework was described as being to prioritise resources; empower staff; enhance service delivery, information sharing and collaboration ‘at the right levels’; facilitate monitoring and management of service level agreements; clarify roles and responsibilities between ADHA and service providers; and ensure timely escalation of issues and continuous improvement. The framework was updated five times between 2 March 2022 and 28 September 2023, including to reflect ‘audit findings’, with another review scheduled for December 2023. The review did not occur and in March 2024 ADHA advised the ANAO that the framework will be reviewed before December 2024.

Procurement and contract management training

2.10 ADHA’s procurement area provides non-mandatory training for staff on procurement and contract management. A training session was held for staff when the BuyRight system was introduced in May 2021, which 241 staff attended. In June 2023 the procurement area delivered contract management training, which was attended by 60 ADHA staff. ADHA provided evidence of staff attendance at other training sessions held in 2023 covering BuyRight, financial literacy and procurement.

Probity policies

Conflict of interest

2.11 The Australian Public Service (APS) Code of Conduct requires that APS employees take reasonable steps to avoid any real or apparent conflict of interest.26 Where conflicts cannot be avoided, the APS Code of Conduct, PGPA Act, and PGPA Rule require that employees must disclose details of any material personal interest.27 The APS Commission states that entities may choose to require written declarations of interest of employees at particular risk of conflict of interest, such as those involved in procurement.28 The CPRs state that officials undertaking a procurement must recognise and deal with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest.29 Finance guidance on ethics and probity in procurement states that:

Persons involved in the tender process, including contractors … should make a written declaration of any actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interests prior to taking part in the process. These persons should also have an ongoing obligation to disclose any conflicts that arise through until the completion of the tender process.30

2.12 Although ADHA’s procurement policy does not mention conflicts of interest, other procurement guidance addresses this.

- The procurement manual (which was in force between August 2018 and December 2023) required officials involved in procurement to recognise and deal with conflicts of interest. The procurement manual stated that where a conflict of interest was declared, the person’s manager would decide how it would be managed, which could include divesting the interest, removal from the procurement process or seeking manager approval to continue. The procurement manual did not indicate whether ‘nil’ declarations were required.

- As at February 2024 ADHA’s BuyRight framework (which replaced the guidance in the procurement manual from 13 December 2023) included procurement-specific conflict of interest obligations in two different tender evaluation plan templates. One of the templates does not clearly indicate whether ‘nil’ declarations are required from ADHA employees involved in the procurement.31

- Contract management guidance on BuyRight states that in setting up contract administration, any conflict of interest declarations are to be provided. It also states that reminders of these obligations are to be included in meeting agendas if appropriate. Similar information is not included in the strategic/complex contract management plan template.

2.13 ADHA has had a general conflict of interest policy since June 2019 that is accessible to staff on its intranet.32 Senior Executive Service (SES) officers must make a declaration (including of nil interests) on appointment, annually, and if any material change. Non-SES staff must make a declaration if aware of a ‘real, apparent or potential’ conflict. The conflict of interest policy specifically deals with procurements, noting that ‘The purchase and disposal of goods and services across the public sector, including managing tenders and contracts, is considered an area of high risk for conflict of interest situations.’ The conflict of interest policy states:

In all cases, the procurement manager, steering group or advisory committee responsible for the procurement must have a mechanism in place to ensure that conflicts of interests are declared by all involved with the project’s decision-making and assessment processes.

2.14 Tender evaluation panel members are required by the conflict of interest policy to declare conflicts to the tender evaluation panel chair. Furthermore, the conflict of interest policy states that a ‘Confidentiality, Privacy and Conflict of Interest Deed Poll’ must be completed and signed by all delegates, tender evaluation team members and advisors. The Deed Poll requires a ‘nil’ declaration (that is, the signatory must warrant that no conflict of interest exists or is likely to arise in the performance of work associated with the procurement, or to detail any potential conflicts). The conflict of interest policy specifies conflict of interest requirements for contractors and consultants.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.15 ADHA could ensure that the procurement policy, procurement guidance, and contract management guide consistently address the risk of conflicts of interest, and are aligned to its conflict of interest policy, to ensure there are clear and consistent instructions for officials involved in a procurement about when and how to declare potential conflicts, including the requirement for a ‘nil’ declaration at the commencement of a procurement process. |

2.16 The conflict of interest policy does not apply to ADHA’s board. The board’s conflict of interest requirements are set out in the board’s charter.33 Board members are required to make a declaration of interests upon their appointment and then annually, with declared interests and management plans recorded in a register. In addition to periodic declarations, board members are required to give notice to the chair of the board of an interest relating to a meeting agenda, which are to be recorded in the meeting minutes.

Gifts and benefits

2.17 The CPRs state that officials conducting procurements must act ethically throughout a procurement, including ‘by not accepting inappropriate gifts or hospitality’.34 Finance guidance states that: ‘officials must not accept hospitality, gifts or benefits from any potential suppliers’.35

2.18 The ADHA procurement manual in force until December 2023 stated that as a general rule, gifts or hospitality should be refused. The procurement policy did not refer to gifts and benefits until updated in December 2023. The BuyRight framework refers to gifts and benefits in the context of contract management, where it notes ‘the Contract Manager should avoid accepting gifts or benefits from the supplier, including substantial hospitality’.

2.19 ADHA has had a general gifts and benefits policy since June 2019.36 As at February 2024, personnel were required to ‘ensure no conflict of interest exists or could be perceived to exist from the acceptance of a gift or benefit’. The gifts and benefits policy (as at February 2024) required ADHA officials to declare all gifts which are not an ‘inconsequential gift or benefit’. The policy did not define ‘inconsequential’, did not specify a timeframe in which declarations should occur, and did not specify whether unaccepted gifts must be declared. The gifts and benefits policy did not include procurement-specific requirements but did reference the CPRs, and stated that a branch manager or division head can apply additional gifts and benefits requirements where a procurement is being undertaken or a contract being managed. ADHA updated the gifts and benefits policy in March 2024. In the updated version, the reference to ‘inconsequential’ gift or benefit has been removed and there is a requirement for publication and maintenance of a register of gifts and benefits accepted by the agency head or officials that are valued at more than $100. The March 2024 policy states that the register must be updated within 31 days of receiving a gift or benefit.

2.20 As at December 2023 ADHA’s internal gifts and benefits register contained a total of 40 entries. The first entry was dated September 2016 and the last entry was dated November 2023.

2.21 APSC guidance37 states that agency heads must update a public gifts and benefits register quarterly or within 31 days of receiving a gift or benefit, and include any ‘nil’ declaration on the register where they have not accepted any gifts during the reporting period. The APSC guidance required agencies to publish their first register by 31 January 2020.

- In accordance with APSC guidance, ADHA’s gifts and benefits policy requires a public register for gifts and benefits accepted by the CEO valued at more than $100 to be published on ADHA website quarterly. The policy did not refer to the 31-day timeframe for declarations until amended in March 2024.

- As at 1 February 2024, the first register published by ADHA was for April–June 2020, and the last update was for July–September 2023.38

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.22 The Australian Digital Health Agency could:

|

Are there fit-for-purpose oversight arrangements for procurement and contract management?

Business areas are responsible for procurement and contract management and are supported by a central procurement area. The board approves contracts above a certain value threshold and delegates the power to enter into a contract to the CEO for other contracts. There are CEO authorisation instruments to allow officials to conduct procurements and enter into contracts. From April 2021 there was regular reporting to the board on complex and high-risk procurement. The internal audit program has considered contract management but has had limited coverage of procurement. An Audit and Risk Committee has included procurement issues in its reporting to the board but has not provided advice about the sufficiency of controls over procurement risks.

2.23 ADHA has a centralised area for procurement activity, the Procurement and Financial Governance section, with five staff. The section provides advice, training and support to business areas, which are responsible for procurement and contract management activities. For the My Health Record (MHR) National Infrastructure Operator (NIO) contract, the responsible business area is the Technology Planning and Delivery Branch. The August 2019 and June 2022 NIO procurements (see paragraph 1.9) were managed by this branch.

2.24 The ADHA board has delegated certain powers, including to enter into a contract through a procurement, to the CEO through a delegation instrument issued under section 17 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Establishing the Australian Digital Health Agency) Rule 2016 (ADHA Rule). The delegation includes financial limits on the CEO’s power to enter into contracts without the board’s approval. The CEO can authorise officials to spend money and enter into contracts under section 53 of ADHA Rule. Authorisation instruments were in place from March 2017.

2.25 Under section 18 of the ADHA Rule, the board consists of a Chair and at least six, and not more than 10, other members. The number of board members may fall below seven members for a period of not more than six months. Between November 2023 and 17 January 2024, the board was comprised of five members including the Chair. On 18 January 2024 and 26 February 2024, two new members were appointed, bringing the total number of members to seven as required under the ADHA Rule. As at February 2024 the board had experience across healthcare professions, health policy and management. The board has four advisory committees: Clinical and Technical; Jurisdictional; Consumer; and Privacy and Security.

2.26 The ADHA board must approve procurements above a certain value ($5 million as at February 2024). ADHA has had a policy since April 2021 requiring complex and high-risk procurements to be reported to the board every six months. These reports have been provided at the required frequency and include high-level updates on current contract status and procurement activity.

2.27 ADHA contracts out its internal audit function to Axiom Associates.39 Recent internal audits have covered contract management but not procurement. In the three years to 2023–24, contract management internal audits comprised: NIO operational practices and procedures (2021–22, see paragraph 3.4); the multi-vendor environment (2022–23); and contract management practices (2023–24).40 The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit noted in August 2023 that especially where entities are engaging in significant or complex procurements, audit committees should provide increased scrutiny of these activities and consider the prioritisation of procurement in the entity’s program of internal audit.41

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.28 The Australian Digital Health Agency Audit and Risk Committee could consider periodically including procurement on its internal audit work program. |

2.29 ADHA’s Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) has three members. The ARC met seven times in 2021–22, eight times in 2022–23 and four times between July and December 2023.42 During this period, the ARC considered reports on high risk and/or high value contracts and procurement at five meetings, prior to the submission of these reports to the board. The ARC considered the internal audit on NIO operational practices and procedures at its meeting on 16 March 2022 and the internal audit on contract management practices at its meeting on 15 November 2023. The ARC monitors the status of the implementation of internal audit recommendations. In November 2023 the ARC considered a report on the ‘Strategic Control Review Program’, which assessed the effectiveness of controls for contract management and procurement.43

- Contract management was assessed to be ‘largely effective’ based on the outcomes of the internal audit on contract management practices and a model assessing vendor performance to be implemented in September/October 2023.44

- Procurement was assessed as ‘partly effective’ based on the currency of the policy available to staff and the lack of second line assurance activities to ensure ADHA staff are complying with ADHA’s procurement policy and the CPRs.

2.30 Between 1 January 2018 and 30 December 2023 the ADHA board met 60 times and received an update from the ARC Chair at 27 of these meetings. The updates for eight meetings included commentary on procurement or contract management issues, including where the ARC had received briefings on an internal audit or sought more detailed advice from management on lessons learned from MHR-related procurement activity. The ARC endorsed two reports prepared for the board on high risk/high value contracts. In the period there was one specific reference to the NIO procurement for an April 2019 board meeting. The ARC did not report to the board on the adequacy of controls for procurement risks.

3. Contract management

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australia Digital Health Agency’s (ADHA) management of the My Health Record (MHR) National Infrastructure Operator (NIO) contract has been effective.

Conclusion

ADHA’s management of the National Infrastructure Operator contract has been partly effective. The identification and assessment of commercial risk has been limited. The effectiveness of day-to-day administration of the contract is diminished by contract management planning that is not fully fit for purpose. Contract variations within the existing contract term have been made with insufficient assessment of risk, consideration of materiality and justification of value for money. The management of contract performance has not utilised all available levers under the contract.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made six recommendations relating to reviewing procurement and contract management risks; developing a fit-for-purpose NIO contract management plan; improving decision-making on contract variations and the exercise of extension options; improving records management; consistently reviewing contract deliverables; and ensuring system architecture documentation obligations are clearly specified. The ANAO also suggested that ADHA include expenditure reconciliations when seeking approvals to expend and commit funds; clarify guidance on contractor meetings; and update the NIO contract management plan to reflect the current organisational structure.

3.1 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) state that contract management is important in achieving the objectives of a procurement.45 The Department of Finance (Finance) states that good contract management is an essential component in achieving value for money. Finance defines contract management as: ‘all the activities undertaken by an entity, after the contract has been signed or commenced, to manage the performance of the contract (including any corrective action) and to achieve the agreed outcomes’.46 Contract management includes: day-to-day contract administration (including records management); and performance management (measuring, monitoring, and assessing against agreed performance measures and deliverables to enable early warning of, and response to, performance issues).47 The CPRs require entities to consider risks and their potential impact when making decisions relating to value for money assessments, approvals of proposals to spend relevant money and the terms of the contract.48

3.2 The 2012 NIO contract with Accenture Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (Accenture) (see paragraph 1.9) included general terms and conditions, a statement of requirement, performance standards, charges and payments, and 12 schedules covering additional requirements.

Is there effective identification and assessment of National Infrastructure Operator contract risk?

In addition to a quarterly strategic risk assessment which includes consideration of My Health Record and the National Infrastructure Operator, risk assessments specifically related to ADHA’s commercial relationship with Accenture were conducted in 2016, 2019, 2020 and 2022. The quality of the risk assessments varied. Although a 2021 contract management plan assessed the overall risk for the National Infrastructure Operator contract as ‘medium’, it provided no information to justify this overall rating, no indication if this risk assessment exceeded its risk appetite, and no description of or treatments for specific risks. ADHA did not re-assess contract risk on five of the six occasions when the contract with Accenture was varied during an existing contract term between 2018 and February 2024. ADHA assessed risk on two occasions when the contract with Accenture was varied through a procurement, although the quality of risk assessment for one procurement was poor. The terms and conditions of the National Infrastructure Operator contract address a range of commercial and security risks.

3.3 ADHA’s risk management framework requires risk assessments to be undertaken when conducting ‘significant procurement activities’. Since September 2023, ADHA’s risk management toolkit incorporates examples of how to assess procurement risks and establish appropriate controls including through contract management.

3.4 A February 2022 internal audit report (see paragraph 2.27) found that ‘while basic elements of the NIO contract are being effectively managed, they are not adequate, given the scale and complexity of the NIO contract, and the ongoing allocation of key contract deliverables to new vendors’. Of the report’s three recommendations, two related to risk management: assess and document risk-based assurance processes that are coordinated across ADHA to gain independent assurance over key contract deliverables and emerging risks for the NIO contract; and enhance processes to specifically assess, control and treat shared risks within a multi-vendor environment.

3.5 ADHA first conducted a risk assessment relating to the commercial arrangement with Accenture in July 2016 when the contract was novated to ADHA from the Department of Health. The ‘Initial Risk Profile’ used a templated risk tool to determine the level of risk associated with the contract. This found that elements of the contract were potentially high risk including the value, complexity, technology and reputational consequences. The ‘supplier’ element was rated as low risk because ‘there are multiple suppliers in the marketplace with the required skills and experience’. The risk assessment template required content to be added for high-risk elements, including to indicate that ADHA’s central procurement and contract management area had been consulted, the central procurement area’s comments, further identified risks, and actions to be undertaken to address the risks. None of these fields were completed.

3.6 ADHA has assessed strategic risks each quarter since April 2018. Strategic risk assessments are reviewed by the board, the Audit and Risk Committee and the Senior Executive Committee, which supports the CEO.49 The strategic risk assessments establish risk owners, sources and consequences for each strategic risk, likelihood, controls and residual risks. From December 2022, ADHA identified four strategic risks: design, data, delivery and agency. MHR and the NIO were considered at a high level in the analysis of strategic risks.

- Operational risks associated with MHR expansion were considered in the strategic risk register from 2019.

- Aligning NIO risk management practice with ADHA frameworks was identified as a risk treatment in the strategic risk report considered by the board in June 2020.

- An ‘Operational Contracting and Procurement Risk Assessment’ (also called an ‘NIO Risk, Issue and Dependency Register’) was completed in September 2020 by ADHA’s central procurement area and included in ADHA’s broader strategic risk register. Listed risks (of which there were 32, including nine ‘very high’ to ‘extreme’) were operational in nature, with treatments and controls primarily relating to technical IT system features. The register was not updated after October 2020.

- ADHA and NIO security operations teams monitoring the security of MHR was identified as a risk treatment in the strategic risk report considered by the board in July 2021.

- Unsuccessful negotiation of an NIO extension beyond June 2022 was identified as a risk in the strategic risk report considered by the board in April 2022.

3.7 Between 2018 and 2023, five of the six variations (under the existing contract term) to the conditions and value of the 2012 NIO contract with Accenture (as described in paragraph 1.9 and Figure 1.2) did not incorporate any analysis of contract risk. Advice to the ADHA CEO for the variation executed on 12 June 2019 included a risk management plan. The plan identified seven risks, each of which had a likelihood, consequence and risk rating and treatment. There were five ‘medium’ and two ‘medium to high’ risks. Proposed treatments included contract terms, exercise of contract terms (such as the termination of advance prepayments and use of audits), management procedures, stakeholder communications, monitoring and reporting.

3.8 The ADHA board considered risks when approving 2019 and 2022 limited tender procurements to ‘extend’ the contract with Accenture (see paragraph 1.9). In relation to the 2019 procurement, the board considered a limited risk assessment on 6 December 2018 and 20 June 2019. A more thorough risk assessment was conducted for the 2022 procurement (see paragraphs 4.10 to 4.12 for a discussion of these risk assessments).

3.9 A June 2021 contract management plan noted that the overall residual risk rating for the NIO contract was ‘medium’. Reference was made to the July 2016 ‘Initial Risk Profile’ and the September 2020 ‘Operational Contracting and Procurement Risk Assessment’, however no further risk analysis was completed and no justification was provided for the overall ‘medium’ risk rating.

3.10 The NIO contract management plan notes that the contractor (Accenture) is required to deliver a ‘Contract Risk and Issue Management Tool’, which defines the approach the contractor uses to identify risks that may impact on MHR national infrastructure operations, maintenance and support. The contract management plan states that the tool is required to be reviewed annually. Since the novation of the contract to ADHA in 2016, the tool has been provided by the contractor and updated largely as required. The Accenture risk management plan states that ADHA is responsible for reviewing the identified risks and proposed strategies to manage the risks. ADHA has not reviewed the risks and treatments as required by the NIO contract management plan.

Recommendation no.1

3.11 Australian Digital Health Agency review risks associated with procurement and management of My Health Record.

Australian Digital Health Agency response: Agreed.

3.12 The Australian Government Contract Management Guide states that contract managers should consider all aspects of the contract to assess risk exposure, and provides a list of common sources of contract risk.50 The ANAO examined the most recent version (as at February 2024) of the NIO contract against a selection of risk sources. The contract variation executed in June 2022 included a range of provisions to manage risks (see Appendix 3).

National Infrastructure Operator security risk management

3.13 Auditor-General Report No. 13 2019–20 Implementation of the My Health Record System found that ADHA had largely appropriate systems to manage cyber security risks to the MHR core infrastructure, except that its management of shared cyber security risks and oversight processes should be improved.51 The report included five recommendations (all agreed by ADHA) to improve risk management and education, including two relevant to the NIO.52 ADHA’s Audit and Risk Committee closed the recommendations on 30 September 2021.

3.14 The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) sets out the Australian Government’s protective security policy.53 The PSPF is generally not mandatory for corporate Commonwealth entities, however the Intergovernmental Agreement on National Digital Health 2018–2022 required ADHA to comply with the Australian Government’s security and design standards, which include the PSPF.54 The CPRs, which apply to ADHA as a prescribed entity (see paragraph 1.8), state that ‘[r]elevant entities should consider and manage their procurement security risk, including in relation to cyber security risk, in accordance with the Australian Government’s [PSPF]’.55 This requirement is included in the ADHA’s Agency Security Plan, dated 5 July 2022.

3.15 The PSPF comprises five principles, and 16 core policies across four outcomes (security governance, information security, personnel security and physical security). The first outcome of security governance includes seven of the 16 policies: the role of the accountable authority (policy 1), management structures and responsibilities (policy 2), security planning and risk management (policy 3), security maturity monitoring (policy 4), reporting on security (policy 5), security governance for contracted goods and service providers (policy 6) and security governance for internal sharing (policy 7).

3.16 This audit did not examine ADHA’s compliance with the PSPF overall, or with the whole outcome of security governance, but did examine ADHA’s compliance with two elements of policy 6, as policy 6 is specifically focused on procured goods and services. The core requirement (B.1) of Policy 6 is that: ‘Each entity is accountable for the security risks arising from procuring goods and services and must ensure contracted providers comply with relevant PSPF requirements’.56 The ANAO examined compliance with two supporting requirements (B.2) of Policy 6: consideration of security risks in procurement activities and consideration of security risks in contract terms (Table 3.1). The ANAO did not examine the other Policy 6 supporting requirements as they were either beyond the scope of this audit or not relevant, namely: 3(a) (ensuring that security controls included in the contract are implemented, operated and maintained by the contacted provider and associated subcontractor); 3(b) (management of any changes to the provision of goods or services, and reassessment of security risks); and 4 (implementation of appropriate security arrangements at completion or termination of a contract).

Table 3.1: Compliance of NIO contract with selected supporting requirements of PSPF Policy 6

|

PSPF Policy 6 supporting requirement |

ANAO assessment of compliance |

Rating |

|

|

Supporting requirement 1. Assessing and managing security risks of procurement |

When procuring goods or services, entities must put in place proportionate protective security measures by identifying and documenting:

|

Many ADHA documents outline security risks and mitigations as they relate to the NIO, including the Operational Contracting and Procurement Risk Assessment developed in 2020 (discussed at paragraph 3.9), Accenture’s regularly updated Risk and Issue Management Plan (discussed at paragraph 3.10) and other Accenture deliverables, such as the Security Risk Management Plan and the System Security Plan. ADHA is rated as partly compliant with Policy 6 supporting requirement 1 because the security risks of procurement were not specifically and explicitly identified in procurement planning and advice for the two NIO procurements conducted between 2019 and 2022. ADHA did not discuss security risks as part of advice to the board in June 2019 when recommending the extension of the Accenture contract. Security risks were not considered in the procurement plan established for the 2019 procurement. ADHA identified and proposed mitigations for risks to MHR operations (including service continuity and reliability) in advice to the ADHA board in March 2022 when again recommending the extension of the Accenture contract, however this assessment did not cover security risks. While the ADHA board and Audit and Risk Committee were provided with regular strategic risk assessments and advice about the ADHA’s security risk posture and security activities (including three MHR-related Information Security Registered Assessor Program assessments conducted in 2019, 2021 and 2022), there is no evidence as to how these activities were taken into account in the 2019 and 2022 NIO procurements. ADHA advised the ANAO in March 2024 that ‘[ADHA’s] Procurement team is required to refer all procurement proposals for ICT services or IT products, including software as a service, through Cyber Security Branch (CSB) to ensure that a cyber risk assessment is completed prior to engaging new service partners’. Accenture, as an existing service provider, was not subject to these arrangements in the 2019 and 2022 procurements. ADHA advised the ANAO in May 2024 that: ’Although these risk assessments were not specifically conducted for each contract variation, the ongoing operational nature of the engagement and the existing contractual terms had already identified the risks and had controls in place to manage them.’ |

▲ |

|

Supporting requirement 2. Establishing protective security terms and conditions in contracts |

Entities must ensure that contracts for goods and services include relevant security terms and conditions for the provider to:

|

The contract includes a provision that Accenture comply with ADHA security procedures and requirements and specifies compliance by the contractor and its personnel with the Commonwealth Data Protection Protocol, the PSPF and the Information Security Manual. The contract provides that the ADHA may notify the contractor about the level of security or access clearance required for the contractor’s personnel. The contract includes that the provision of equipment by the contractor must comply with applicable Australian or New Zealand standards or, if required, applicable international standards.a |

◆ |

|

|

|

The contract provides that the contractor is ‘responsible for the pro-active, ongoing monitoring of the National Infrastructure, in order to detect potential and/or actual security breaches’.. There is a requirement for monthly security reporting on the ongoing management of security and identification of security risks, threats and incidents, which forms part of service levels. The contractor is required to develop an ‘operations plan’ which includes security management training; release management and upgrade planning; risk management plan that covers security risk management planning and mitigation; and business continuity and disaster recovery planning. |

|

|

|

|

The contract requires the contractor to ‘work closely and collaboratively with all other Providers in the effective operation of the My Health Record System’ and participate in meetings. An ‘Escalation Process’ is a contract deliverable, and this describes the escalation process followed in the case of incidents which are being managed by the contractor including the categorisation of security incidents. The contract includes provisions that require the contractor to perform the services ‘in accordance with any directions given by the Digital Health Agency from time to time, provided those directions are not inconsistent with the Contract’. |

|

Key: ◆ Compliant ▲ Partly compliant ■ Non-compliant.

Note a: The Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) performs evaluations for products used to protect data classified as SECRET and TOP SECRET. For an organisation seeking to procure evaluated products, the Common Criteria’s Certified Products List contains a list of products that have been evaluated, certified and recognised. The ASD Guidelines for Evaluated Products recommend that high assurance evaluations be sought from the Australian Signals Directorate for the provision of equipment used to protect SECRET data and the Common Criteria’s Certified Products List is considered when ensuring the integrity and authenticity of applications and ICT equipment provided by the contractor. See ASD, Guidelines for evaluated products, available at https://www.cyber.gov.au/resources-business-and-government/essential-cyber-security/ism/cyber-security-guidelines/guidelines-evaluated-products [viewed 10 February 2024]. The contract does not address high assurance evaluations. The ADHA advised the ANAO in February 2024 that as the ADHA’s data was rated to a maximum of ‘protected’, this was not relevant to the contract.

Source: PSPF Policy 6 and ANAO analysis of ADHA documentation, including the latest variation of the NIO Accenture contract as at February 2024, which is to 30 June 2025.

Has the National Infrastructure Operator contract been administered effectively?

The effectiveness of contract administration has been diminished by the following.

- There is a National Infrastructure Operator contract management plan. The plan has not been reviewed as required and does not contain some of the required information. There are no instructions to officials about how and when to assess contract risk.

- The National Infrastructure Operator contract with Accenture was amended eight times between January 2018 and February 2024 largely to fund My Health Record system enhancements, including six amendments (valued at $54 million) executed during the term of the existing contract. For the six contract amendments, ADHA did not document value for money considerations.

- ADHA did not review the contractor’s performance when it exercised an option to extend the contract.

- ADHA held strategic and operational meetings with the contractor, but these were not always at the specified frequency. Not all specified meeting types took place and some meeting types took place that were not specified.

- Officials managing the National Infrastructure Operator contract did not adhere to the ADHA’s records management policies.

Contract management planning

3.17 A contract management plan for the NIO contract was first established in 2016 and last amended in June 2021. The 2021 NIO contract management plan was required to be reviewed by 30 June 2022 or at the next contract variation. The NIO contract was varied on 26 June 2022, however as at February 2024 the 2021 contract management plan had not been reviewed.

3.18 As described at paragraph 2.8, the contract management plan template includes a list of required content. The 2021 NIO contract management plan includes a range of information consistent with this template including governance arrangements for contract management; deliverables; standards; performance monitoring arrangements; and payments. However, the 2021 contract management plan content does not fully align with the template.

- While the NIO contract management plan specifies the reporting deliverables that will be used for the performance assessment against service levels, it does not list the clauses of the NIO contract relating to performance obligations or what actions are to be taken if there is underperformance.

- The NIO contract management plan specifies that ADHA has the power to conduct audits under the contract but does not elaborate on when or how these are to occur.

- The NIO contract management plan refers to termination/step-in clauses, but does not include any detail on any processes to be followed including notice periods, show cause notices and any other invitations to remedy defects.

- The NIO contract management plan refers to a register of variations and extensions executed from 1 July 2016 and includes a flow chart of the ADHA’s approach to managing variations, but does not list the contract requirements for implementing a variation or contract closure.

- The contract management plan should include a link to the risk management plan and details of risk identification, analysis and management. As noted at paragraph 3.9, the 2021 NIO contract management plan included a link to 2016 and 2020 risk assessments, which were out of date and lacking in detail, and the contract management plan did not provide justification for the overall ‘medium’ risk rating. No specific guidance or instructions about how to assess and manage risk are addressed in the contract management plan.

3.19 The NIO contract management plan does not refer to, or provide instructions for, several key contract provisions:

- undertaking ‘benchmarking’ of the standards of delivery and costs of services57;

- arrangements relating to subcontractors and subcontracting;

- dispute resolution; or