Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Procurement Initiatives to Support Outcomes for Indigenous Australians

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of procurement initiatives to support opportunities for Indigenous Australians.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Government’s policy on procurement is contained in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which are administered by the Department of Finance (Finance). The CPRs set out the rules for government procurement and the obligations on officials when undertaking a procurement. The CPRs also incorporate the requirements of Australia’s international trade obligations. The core element of the CPRs is to promote the use of sound and transparent procurement practices that seek to achieve value for money for the Commonwealth.1 To support value for money outcomes, procurement by government entities is expected to be based on processes which encourage competition and non-discrimination, and which result in the efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of public funds.2

2. The significant purchasing power of government means that procurement policies and actions of governments can also be used to influence broader strategic policy objectives, such as employment outcomes for marginalised groups, environmental outcomes, and growth of the small and medium business sectors.3 Successive Australian Governments have developed and maintained a range of Procurement Connected Policies (PCPs) to support the achievement of such targeted outcomes within the overall procurement framework. As at June 2015, there were 18 PCPs in place, covering a range of areas including outcomes for Indigenous Australians.4

3. The Australian Government’s approach to promoting Indigenous opportunities through procurement generally operates at two levels. Firstly, the approach seeks to maximise opportunities within government contracts to increase Indigenous training, employment and business opportunities by placing obligations on suppliers. Secondly, the approach seeks to increase the number of Indigenous businesses that are awarded government contracts in their own right.

4. The Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines released in 19985 required entities issuing contracts over a financial threshold of $5 million ($6 million for construction), and in areas with high Indigenous populations, to consider how employment and training outcomes for Indigenous Australians could be promoted. This requirement was subsequently referred to as the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP). The IOP was strengthened in 2011, to require any suppliers (Indigenous or non-Indigenous) that won Australian Government contracts in IOP regions, which were over the financial threshold, to develop, implement and report on a plan to employ, train and provide sub-contracting opportunities to Indigenous Australians.

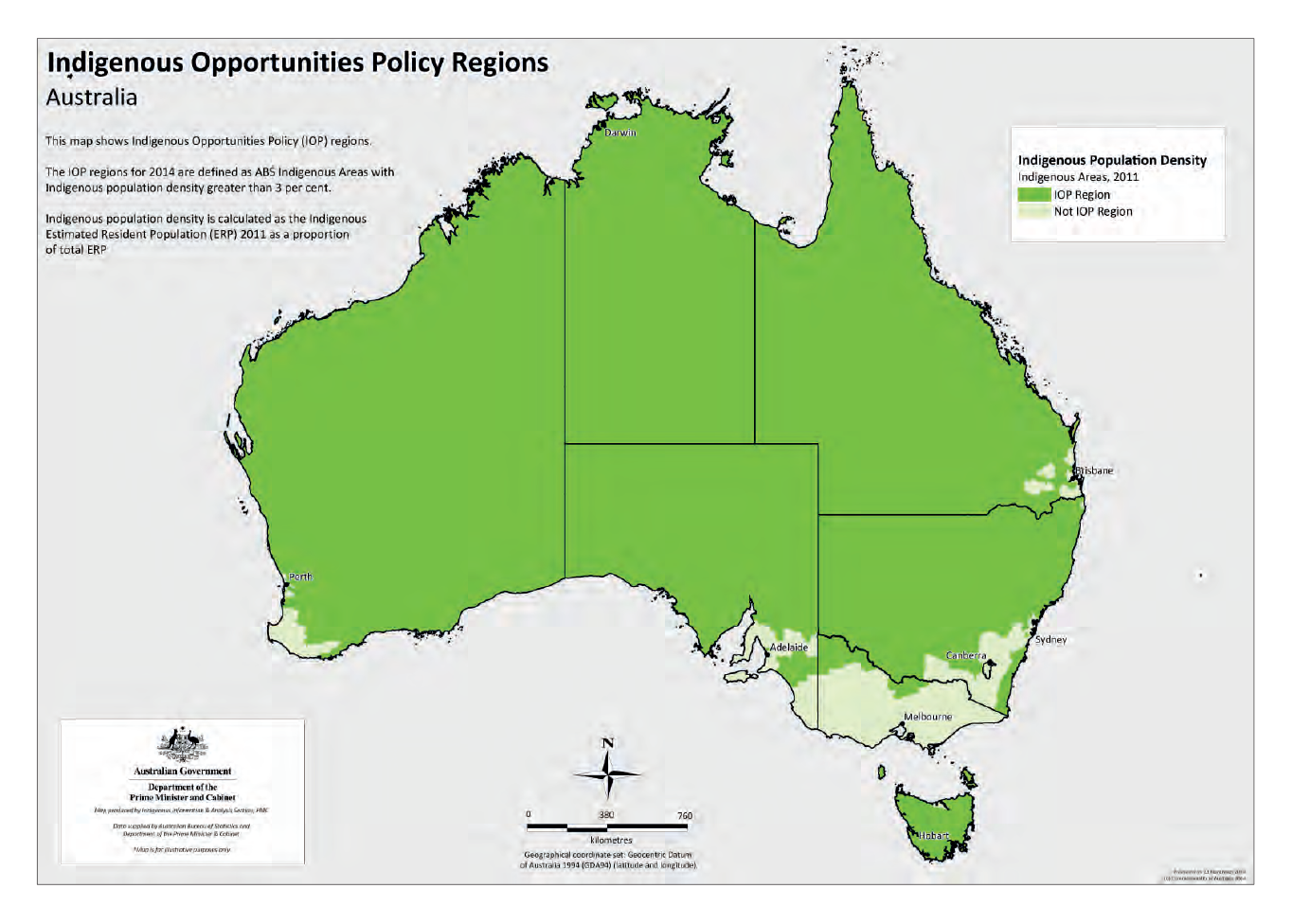

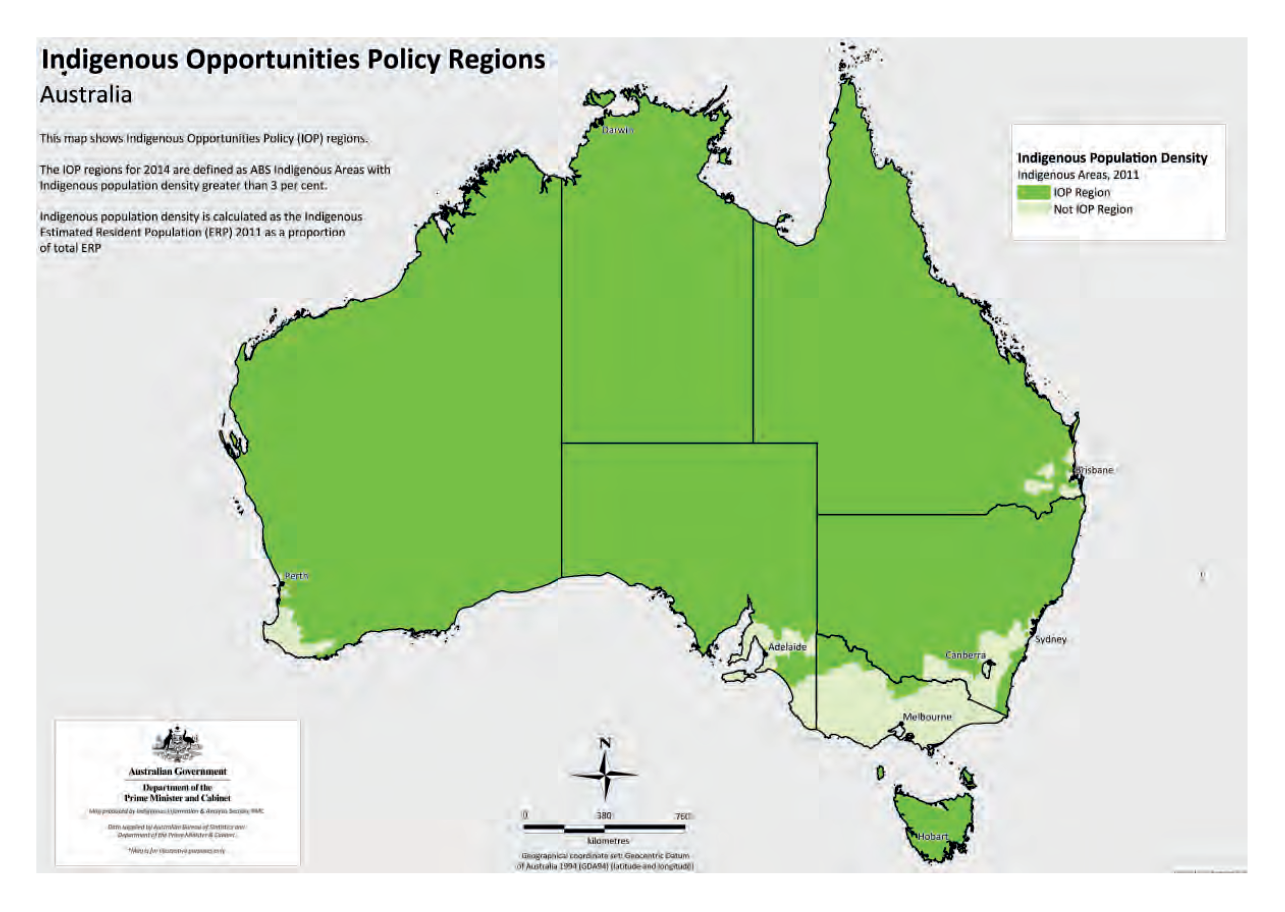

5. A region was defined as an IOP region if the Indigenous population for the area was above the national average of three per cent. IOP regions, as at April 2015, are shown in Figure S.1. In most urban areas of Australia the Indigenous population is lower than the national average and therefore these areas were generally excluded from the operation of the IOP.6

Figure S.1: Indigenous Opportunities Policy Regions as at April 2015

Source: PM&C.

Note: Additional maps, showing some local areas within major cities which are identified to be in IOP regions are included at Appendix 6.

6. Under the IOP, Australian Government entities were required to identify whether a proposed procurement met the requirements to be identified as an IOP contract and include this information in their approach to market. All suppliers that were successful in winning IOP related contracts were in turn required to develop and implement an approved Indigenous Training, Employment and Supplier Plan (IOP Plan) to create training, employment and business opportunities for Indigenous Australians. The IOP was administered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), which was responsible for establishing guidance, monitoring and reporting on the application of the policy. Australian Government entities were required to ensure that the supplier to which they issued an IOP related contract had an IOP plan, which had been approved by PM&C, in place for the duration of the contract. Entities were not, however, required to include the approved plan within their contract arrangements with the supplier, nor were they required to monitor or report on the outcomes achieved for Indigenous Australians resulting from their procurement activities. Suppliers with IOP related contracts were required to provide regular reporting to PM&C on the implementation of their IOP plans.

7. With respect to directly increasing the participation of Indigenous businesses in government contracting, the Australian Government added a specific exemption under the CPRs in 2011. The Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE) enables entities to directly approach Indigenous businesses for procurements valued over the relevant financial threshold7 without making an open approach to market or applying the other additional conditions required under the CPRs for high value procurements. The intent of the IBE was to streamline procurement and reduce administrative requirements where possible. As at June 2015, the IBE was one of 17 exemptions to the CPRs.8The CPRs are administered by Finance, the decision as to whether to apply the IBE, along with the responsibility to do so in accordance with the CPRs, rests with the entities undertaking procurement.

8. The Australian Government’s Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) came into effect on 1 July 2015 to replace the IOP. The IPP requires all government portfolios to have a target for the number of contracts awarded to Indigenous businesses. The target is being phased in over time and is expected to reach 3 per cent of all contracts by 2019–20. Performance against the target is to be published annually and reporting arrangements strengthened. In addition, for certain Commonwealth contracts, a mandatory set aside process applies, which requires entities to consider whether an Indigenous business can deliver the required goods or services on a value for money basis before an approach to market can be made. Similar to the IOP, some government contracts are still required to include minimum ‘Indigenous participation requirements’ for Indigenous employment and Indigenous business use, however, in contrast to the previous IOP, procuring entities are now required to monitor these. No changes have been made by Finance to the administration of the IBE, however the introduction of targets, and the set aside approach, is expected to result in an increase in the use of the IBE by entities, and an ability to extract relevant data is expected to be enhanced.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

9. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of procurement initiatives to support opportunities for Indigenous Australians.

10. To conclude against this objective the ANAO adopted high-level criteria which considered the effectiveness of the administration by PM&C and Finance of the IOP and IBE respectively. The criteria also considered the application of these policies by selected entities and the overall monitoring and reporting of outcomes achieved.

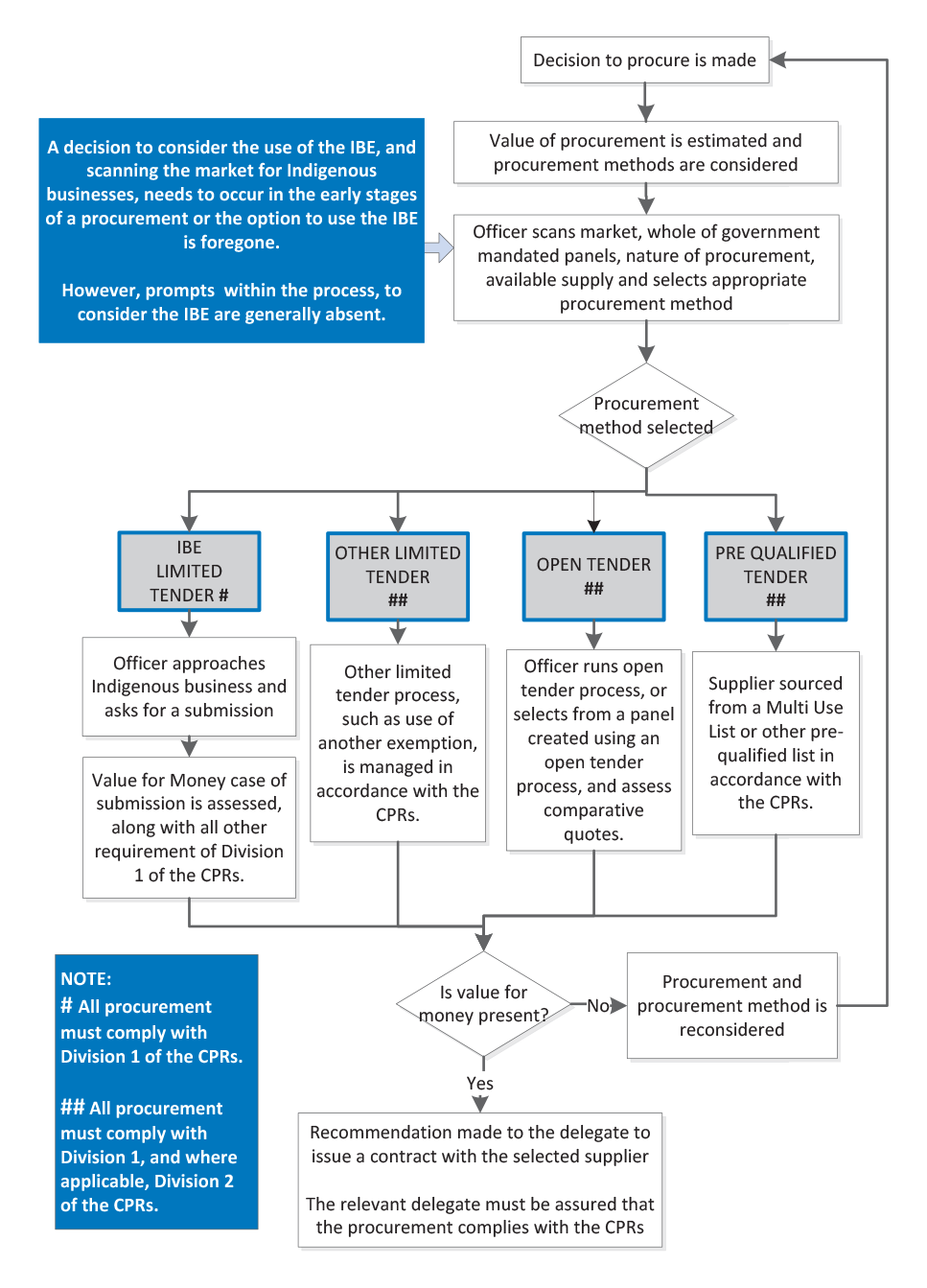

11. The scope of the audit included:

- the application of the IOP since 2011 by selected Australian Government entities and its overall administration by PM&C, and formerly by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR); and

- the use of the exemption for Indigenous businesses in the CPRs by selected Australian Government entities and the administration of the exemption by Finance since 2011.

12. The application of the IOP and the IBE was examined in the following entities:

- Department of Defence (Defence);

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO);

- Department of Human Services (DHS);

- Department of Employment (Employment);

- Department of Industry and Science (Industry); and

- Department of Education and Training.

13. The ANAO also considered aspects of the Indigenous Procurement Policy which commenced from 1 July 2015, insofar as the experience of the IOP and IBE is relevant to its implementation.

Overall conclusion

14. Procurement Connected Policies (PCPs) to improve Indigenous economic outcomes have been used in various forms by the Australian Government since 1998. Through the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP) and the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE), a two-tiered approach was developed that sought to increase Indigenous involvement in the government supply chain, both directly as suppliers and indirectly through training and employment opportunities. Indigenous organisations have generally played a significant part in the delivery of government services funded through grant programs but the participation of Indigenous businesses in government procurement has remained very low.

15. Overall, while the policy intent to leverage better Indigenous outcomes from Australian Government procurement activity has been clear, the frameworks developed by entities to achieve the objectives have not generally facilitated effective delivery of the outcomes sought. Key factors in this respect include the geographical limitations placed on the application of the IOP, the absence of any requirement for procuring entities to drive or monitor outcomes including those resulting from either their own or their suppliers actions, and the voluntary reporting requirements placed on entities which have hindered the ability of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the Department of Finance (Finance) to analyse activity and provide advice to government. A number of these issues are being addressed in the development of the new policy arrangements from 1 July 2015, although achieving the intended policy outcomes is likely to require continued efforts by government entities.

16. In developing the IOP framework, a significant population was defined as being one where the proportion of the Indigenous population of a region was equal to or higher than the national average. This relative approach, however, had the effect of excluding areas, particularly urban areas, where there were significant Indigenous populations in absolute rather than relative terms. As a result, the geographic regions where the IOP applied until June 2015 included only 73 per cent of the total Indigenous population and did not generally include urban and some regional areas where economic activity was likely to be higher and more diverse.

17. The geographic requirements of the IOP also provided practical challenges to its application by entities. Entities were required to determine whether contracts over certain values should have been identified as being subject to the IOP based on the physical location of the main contract activity. IOP regions were determined and publicised by PM&C, and it provided guidelines for entities and businesses. However, in cases where contracted activity occurred in multiple locations, including in both IOP and non-IOP regions, the interpretation of the requirements was not always straightforward and implementation by the entities included as part of this audit was not always consistent. More broadly, the data systems of audited entities often did not sufficiently capture the geographical locations where the main contracted activity was to take place and generally a limited record was maintained of decisions in relation to whether the IOP should be applied to particular approaches to market.

18. In order to minimise the additional workload on procuring entities arising from the introduction of the IOP, entities were required only to take steps to ensure that a supplier has an approved IOP plan in place prior to issuing a contract. These plans were to provide details of the suppliers’ commitments in relation to Indigenous employment, training and business opportunity. Suppliers were required to implement these commitments if awarded a contract. Entities, however, were not required to include any of the supplier’s commitments under the plan into the contract nor to monitor the implementation of any of those commitments as part of managing the contracts. Instead, PM&C—and prior to that the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR)—had the responsibility to monitor that entities are appropriately identifying contracts to which the IOP applied and to receive the required reports from suppliers about the implementation of their IOP plans. While PM&C, and previously DEEWR, made appropriate efforts to fulfil this responsibility, the voluntary nature of entity reporting and data limitations, where the geographical location of contracts is not recorded in the government’s procurement database (AusTender), means that relevant information upon which to assess implementation was not easily accessible. As a result PM&C was not well positioned to advise government on the extent that the IOP contributed to the desired objective of creating economic opportunities for Indigenous Australians, or on the extent that Australian Government entities were appropriately implementing the IOP.

19. To complement the IOP and improve direct access for Indigenous business as suppliers to government, the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE) allows entities to conduct streamlined procurement processes with Indigenous businesses within the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). Although the IBE has been available under the procurement framework since 2011, use of the IBE was low in the entities examined by the ANAO and there is no aggregated reporting by Finance on the use of the exemption by Australian Government entities. Based on available data, the involvement of Indigenous businesses in government purchasing is very limited. Since 2011, 120 contracts with Indigenous businesses certified through Supply Nation9 have been listed on AusTender. Of these, only 17 were listed as limited tender procurements over the relevant financial threshold and where the exemption may have been applied.

20. Using the IBE requires procurement officers to consider choosing a procurement method on the basis of the indigeneity of the supplier and, at times, with limited information on the strength and distribution of the Indigenous supplier market. These decisions are required early in the procurement process and require entity staff to assess the value for money represented by an Indigenous business proposal in the absence of a competitive assessment process, requiring other information to be sought in order to make an assessment of value for money. While the IBE may shorten the timeframes of some procurements by removing the need for an open tender process to occur, the additional steps (scanning the market for suitable Indigenous supplier(s) and approaching them for a quote) and decisions (assessing the value for money offering of a supplier in the absence of an open approach to market) outside of the more commonly used procedures, may also be contributing to the low levels of application of the IBE.

21. Some Indigenous businesses interviewed by the ANAO reported that use of the IBE was generally only considered by entity staff when support for its use was advocated by a sufficiently senior officer of the entity, and that committed leadership was a key element present in the cases when their approaches to entities resulted in the use of the IBE. However, Indigenous businesses reported that in most cases, their approaches to entities did not result in the use of the IBE being actively considered as a procurement method.

22. From 1 July 2015, Australian Government portfolios are required to report performance against agreed targets for the level of contracting with Indigenous business, and to set aside some contracts for which Indigenous businesses will be approached, on a value for money basis, prior to any approach to the open market. Based on current performance, both in terms of the low level of entity use of Indigenous suppliers and in terms of oversight, monitoring and reporting arrangements, successful implementation of these new policy requirements will need increased promotion and support.

23. The Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) introduces flexibility in the way entities can approach their targets including by: setting them at portfolio levels; allowing sub-contracting opportunities to be included; applying a formula to enable the conversion of the target from number of contracts by volume to a target by contract values; and including contracts with Joint Ventures which have at least 25 per cent Indigenous equity. Nonetheless, the targets are ambitious. There are risks in seeking to move quickly to meet the new targets and entities will need to be vigilant to ensure that the requirements of the procurement framework, including achieving procurement outcomes economically and efficiently, continue to be met in addition to meeting the targets. While the IPP is the overarching framework in relation to Indigenous procurement policy, some elements of the IOP have remained, including the use of geographically-defined areas. In view of the experience of entities to date there would be merit in PM&C further reviewing the approach to determine the conditions under which the proposed minimum Indigenous participation requirements may be most effectively applied, particularly those relating to the use of Indigenous businesses by government suppliers. The ANAO has made three recommendations to assist PM&C and Finance to better implement, monitor and report on initiatives seeking to increase opportunities for Indigenous Australians through government procurement.

Key findings by chapter

Chapter 2 – Application of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy

24. As the administrator of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP), PM&C, and previously the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR), sought to facilitate its efficient administration and the creation of opportunities for Indigenous Australians. In that context, PM&C, and DEEWR, undertook a number of activities and developed systems and guidelines to promote awareness and understanding of the IOP, and to clarify key aspects of the policy. However the regional application of the IOP added complexity to its administration, and the guidelines allowed a number of possible interpretations, particularly where contracted activity occurred in multiple locations.

25. Entities were responsible for implementing the IOP by determining its applicability to a project in the planning stages (and consulting with PM&C if they were uncertain), and by ensuring that Approaches to Market (ATM) documentation included reference to the IOP when applicable. Entities were also responsible for ensuring that IOP Plans had been approved, or were in the process of being assessed by PM&C for the tenderer(s), and that they remained current during the term of any IOP related contracts. Overall, the application of the IOP by entities was variable, and while some entities reported to PM&C on the contracts to which they have applied the IOP, not all entities reported, and not all contracts applied the IOP as required. The voluntary nature of entity reporting, and the lack of a central mechanism for PM&C to monitor application of the IOP to contracts meant that the extent of under-reporting by entities was not accurately known by PM&C.

26. The Australian Government introduced the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) with effect from 1 July 2015. The new policy has added additional requirements on entities to monitor and report against their activities and to apply the mandated ‘set aside’ policy and the minimum participation requirements to some contracts. Some elements of the IOP have continued under the new policy, including the geographic application of ‘minimum Indigenous participation requirements’ to some contracts. In this respect the experience of implementation of the IOP to date is relevant to informing the implementation of the IPP including the complexities introduced by a regional approach, in relation to the use of Indigenous businesses and the ability to use AusTender for overall monitoring.

Chapter 3 – Use of the Indigenous Business Exemption

27. The Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE) is a component of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which are administered by Finance. As part of its overall role in relation to the CPRs, Finance has prepared guidelines on the use of the IBE. However, an approach to more broadly promoting the potential for the IBE to contribute to Indigenous policy outcomes has not been developed by PM&C, or previously by DEEWR. Some Indigenous suppliers interviewed by the ANAO observed a low level of awareness of the IBE. Entity staff interviewed by the ANAO perceived a number of potential barriers to the IBE’s use, including the difficulty in identifying a suitable Indigenous business, and having sufficient information to assess whether a value for money outcome would be achieved through the use of the IBE, compared to undertaking an open tender process.

28. Data on the overall use of the IBE is not collected or reported by either Finance or PM&C. Finance generally does not report on the use of any of the CPR exemptions. Finance does, however, regularly extract data using the Australian Business Numbers (ABNs) of Australian Disability Enterprises, to assist the Department of Social Services in monitoring the use of the exemption provided for Disability Enterprises (Exemption 16 of the CPRs). While no similar arrangement had been put place in relation to the IBE as at June 2015, PM&C has agreed with Supply Nation to expand the list of ABNs it holds from 1 July 2015, and for PM&C to use this list for data extraction from AusTender. The introduction of targets for procurement from Indigenous businesses and the requirement for entities to set aside certain procurements to give Indigenous businesses first option to tender are likely to increase the future use of the IBE. Accordingly, strengthened promotion of the IBE by PM&C among entities will be an important consideration to support the implementation of the changed Indigenous procurement arrangements from July 2015.

Chapter 4 – Monitoring Outcomes

29. The broad aim of the IOP and the IBE has been to increase the employment and business opportunities available to Indigenous Australians generated as a result of the procurement activity of Australian Government entities. To assess the effectiveness of these initiatives over time, a baseline of current use would need to be established and supported by periodic and reliable reporting of relevant performance data. However, the extent to which Indigenous businesses were included in government procurement supply chains has been difficult for relevant departments to establish due to the lack of a comprehensive and accessible way of identifying Indigenous businesses. In addition there have been variations in the definitions of an Indigenous business10 used over time.

30. Further, the reporting arrangements for the IOP limited the ability of PM&C to readily obtain information on the use of the IOP and any outcomes being achieved and there were no obligations on the entities managing IOP contracts to actively assess outcomes. The use of exemptions to the CPRs is not required to be reported, and data on the use of exemptions, in general, is not centrally collected. Accordingly, and in line with the voluntary nature of its application, there is currently no centralised capture of data on the use of the IBE. As a result there has been no regular reporting to government on the effect of either initiative in relation to their operation or impact on the desired policy outcomes.

Summary of entity responses

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

The Department agrees with all of the recommendations in the report. The ANAO’s recommendations align with the new Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) that was jointly released on 25 May 2015 by the Minister for Indigenous Affairs and the Minister for Finance. From 1 July 2015, the IPP will commence, replacing the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP).

I appreciate the collaborative approach the ANAO has taken in performing this audit and acknowledge the contribution that your work has made in developing the IPP.

Department of Finance

The Department supported all of the recommendations in the report.

Department of Defence

Defence acknowledges the recommendations contained in the audit report on the Procurement Initiatives to Support Outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

Defence has made a significant contribution to the new Indigenous procurement policy through its membership of the Indigenous procurement cross entity working group that is co-chaired by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and Department of Finance. Defence has also implemented various initiatives to support Indigenous suppliers; such that spending has increased to over $900 000 in quarters 1 and 2 of Financial Year 2014-15.

Defence notes that to obtain entity buy-in, current and future policy and procedures should be practical in their application, otherwise they will be difficult and resource intensive to apply and desired outcomes may not be achieved.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) notes that there are no recommendations directed to the department. Notwithstanding, the department welcomes the report and considers that implementation of its recommendations will enhance the effectiveness of the Commonwealth Procurement Framework in providing opportunities to Indigenous Australians through government procurement.

The introduction of the Indigenous Procurement Policy, which the department is currently assisting the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet to develop, will be a significant step in addressing the ANAO recommendations and will assist the department in delivering further outcomes to Indigenous business through its established Supplier Diversity Strategy.

Department of Education and Training

The recommendations in this report are supportive of a whole of government approach aimed at the ongoing improvement for Indigenous Australians in relation to government procurements.

The Department of Education and Training looks forward to continuing this work through implementation of the new Indigenous Procurement Policy.

Department of Employment

The Department of Employment welcomes the report on Procurement Initiatives to Support Outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

The Department of Employment will continue to be actively involved in the implementation of the Indigenous Procurement Policy to improve Indigenous economic development and Indigenous employment. As part of our commitment to Indigenous procurement initiatives, and in collaboration with the Shared Services Centre, the Department has implemented strategies to promote the introduction of the Indigenous Procurement Policy on 1 July 2015.

The new Indigenous Procurement Policy includes improved monitoring considerations and the Department is taking steps to improve our procurement monitoring and reporting to include the capture of all Indigenous procurement in accordance with the Indigenous Procurement Policy definitions.

Department of Industry and Science

The Department of Industry and Science acknowledges the findings of the ANAO audit on Procurement Initiatives to Support Outcomes for Indigenous Australians and supports the recommendations proposed in the report.

The department notes the difficulty in identifying a broad sample of Indigenous businesses and as a result the approach taken was to rely heavily on Supply Nation. The department notes that this approach is likely to underestimate the actual instances of procurement from Indigenous Businesses given that Supply Nation certified suppliers represent a small percentage of Indigenous Businesses.

Australian Taxation Office

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) strongly supports this ANAO report’s findings and recommendations. The ATO will work with and support PM&C and Finance on delivering the recommendations.

In particular the ATO supports the approach in which agencies take responsibility for achieving the Indigenous Procurement Policy outcomes for their own contracts.

The ATO accepts the feedback from Indigenous businesses in the report that application of Indigenous procurement policies generally only occurred when supported by senior leaders in an agency.

The ATO’s senior leaders actively support the objective of increased Indigenous economic participation through our procurement activities.

To support this, the ATO has:

Established a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) and Supplier Diversity strategy that includes procurement targets,

Proactively engaged with suppliers to build sustainable arrangements that incorporate Supply Nation certified suppliers, and

Actively sourcing MURU Group paper supplies through our stationery supplier.

The ATO’s approach and strategy to engage, inform and support Supplier Diversity has received endorsement from Supply Nation and Indigenous businesses.

Supply Nation

Supply Nation, on behalf of its Indigenous certified suppliers and corporate and government members welcomes this report and the lessons learnt from the government’s history of Indigenous business engagement. Supply Nation and its partners aim to effectively adapt to and enhance the new strengthened Indigenous Procurement Policy, launching 1 July 2015.

Supply Nation has begun registering 50 per cent or more Indigenous owned business, which will be listed on a new public directory of Indigenous businesses called Indigenous Business Direct, to launch 1 July 2015. Registered businesses that meet certification criteria (51 % or more owned, managed and controlled) will be encouraged by Supply Nation to become certified. Once certified, the business will be clearly marked as certified with the Supply Nation Certified logo.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.15 |

In order to inform implementation arrangements for the Indigenous Procurement Policy the ANAO recommends that PM&C, in consultation with other government entities, review the regional approach of the IOP and, as appropriate, provide advice to the Australian Government on potential alternative models by which the proposed minimum Indigenous participation requirements may be most effectively applied. PM&C’s Response: Agreed Finance’s Response: Supported |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.18 |

In order to better promote the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE), the ANAO recommends that PM&C, in consultation with Finance, develop a strengthened promotion strategy which takes into account the exemption’s potential contribution to broader Indigenous policy outcomes. PM&C’s Response: Agreed Finance’s Response: Supported |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 4.25 |

In order to better monitor and report on the contracts facilitated by the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE), the ANAO recommends that PM&C, in consultation with Finance, develop a periodic reporting arrangement, and provide regular advice to the government on the extent of Indigenous business participation in government procurement. PM&C’s Response: Agreed Finance’s Response: Supported |

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the policy context for procurement initiatives targeting outcomes for Indigenous Australians. It also provides an outline of the audit objective, criteria and approach.

Supporting outcomes for Indigenous Australians through procurement

1.1 There is a long history of Indigenous organisations receiving grant funding from government, and there has been a relatively high level of participation by Indigenous organisations in the delivery of services on behalf of the Australian Government. However, to date there has been a much lower level of participation by Indigenous entities in procurement opportunities on a commercial basis. In relation to broader efforts to reduce Indigenous disadvantage, successive Australian Governments have sought to make use of government procurement activities to increase employment and training opportunities for Indigenous people, as well as increasing participation by Indigenous businesses as suppliers to government on a commercial basis.

1.2 Procurement of goods and services is a substantial activity for the Australian Government and in 2013–14, 66 047 procurements were undertaken with a value of $48.9 billion.11 The significant purchasing power of government means that, along with the objective of the efficient and effective purchasing of goods and services, procurement policies and actions of governments can influence broader strategic policy objectives. Examples of these strategic policy objectives include better employment outcomes for marginalised groups, improved environmental management outcomes, and the growth of the small and medium business sectors.

1.3 Through the establishment of Procurement Connected Policies (PCPs) and the inclusion of these into the procurement framework, the Australian Government has sought to leverage off its procurement activities in order to support other policy objectives.12 As noted in the foreword to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules:

The Government is committed to improving access to Government contracts for competitive Small and Medium Enterprises, Indigenous businesses and disability enterprises. Ensuring these suppliers are able to participate in Commonwealth procurement benefits the Australian community and economy.13

1.4 Reflecting this sentiment, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has observed that ‘OECD member countries are no longer considering value for money in the strict sense of price and quality as the sole objective of public procurement’ and that OECD members are ‘gradually including more strategic objectives such as support to small and medium enterprises (SMEs), innovation, and environmental considerations.’14

The procurement framework

1.5 The Australian Government’s policy on procurement is contained in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) which are managed and administered by the Department of Finance (Finance). The core element of the CPRs is to promote the use of sound and transparent procurement practices that seek to achieve value for money for the Commonwealth.15 Division 1 of the CPRs imposes a number of mandatory requirements that apply to all Australian Government procurements, including the need to achieve value for money and the requirement that procurements:

- be non-discriminatory and encourage competition;

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth;

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision making;

- encourage appropriate engagement with risk; and

- be commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.

1.6 As the value of procurement increases, additional mandatory requirements for procurements are applied at certain financial thresholds. Division 2 of the CPRs applies to non-corporate Commonwealth entities for all procurements of $80 000 and over (for procurement of construction services the threshold is $7.5 million). Among other things, Division 2 sets out the requirements for approaching the market, including the requirements for Request for Tender (RFT) documentation, and time limits for which an approach to market must remain open.

Exemptions

1.7 Under certain circumstances, procurements are exempted from the additional requirements of Division 2 of the CPRs. There are 17 exemptions identified in the 2014 CPRs, including the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE) (see Appendix 2 of this report). Finance provides guidance to Australian Government entities on all procurement matters, including in relation to the exemptions. However, as exemptions are generally seeking to achieve outcomes in areas where other entities have the policy responsibilities, the role of promotion (as distinct from providing interpretive guidance) does not necessarily fall to Finance. For example, the Department of Social Services has taken a lead role in the promotion of and monitoring outcomes under Exemption 16 the Disability Enterprise Exemption, and is supported in this role with procurement data provided to it by Finance.

Procurement connected policies seeking to enhance economic outcomes for Indigenous Australians

1.8 The potential for government procurement to support economic participation opportunities for Indigenous Australians has been recognised since at least 1991 when the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody made two recommendations seeking to leverage outcomes from Commonwealth procurement. These recommendations were that governments:

- adopt a fair employment practice of preferencing tenderers for government contracts who are able to demonstrate that they have implemented a policy of employing Indigenous people; and

- award contracts for public works in remote Indigenous communities to local tenderers and those that provide training and employment opportunities to the local community.

1.9 The resulting policies adopted by the Australian Government introduced the requirement for government entities to include clauses:

- in their requests for offer, asking tenderers to indicate the employment opportunities they would provide for Indigenous people if they were to gain the contract; and

- in contracts with winning suppliers specifying their responsibilities in this regard.16

1.10 Subsequently, the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines17 released in 1998 required entities managing procurements over certain financial thresholds ($5 million or $6 million for construction projects) in locations where there were significant Indigenous populations and where there were limited private sector employment and training opportunities for Indigenous people, to:

- consider employment opportunities for training and employment for local Indigenous communities and document the outcomes;

- consider the capabilities of local Indigenous suppliers when researching sources of supply; and

- consult the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission and/or the relevant community council or group, as appropriate, in the planning stages of proposed projects.18

These requirements became known as the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP).

1.11 Further attention to achieving Indigenous economic outcomes through procurement was given in 2008 by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs. In its report Open For Business, the committee made the following recommendations:

- Recommendation 1:

- that the Australian Government conduct a biennial national review of Indigenous businesses in Australia, collating data on industry sector, business size and structure, location and economic contribution.

- Recommendation 9:

- that the Australian Government establish a series of target levels of government procurement from Indigenous businesses, and require all Australian Government agencies and authorities to nominate a target; and

- that all Australian Government agencies and authorities be required to report in their annual report the procurement level from Indigenous businesses and that future consideration should be given to introducing an escalating series of mandated procurement levels over the next decade.

- Recommendations 13 and 14:

- that the Australian Government fund an Indigenous Minority Supplier Development Council; and

- that government agencies with significant procurement budgets become members of the Supplier Council and direct a targeted proportion of their budget to Indigenous suppliers through the supplier council.19

1.12 The then Australian Government did not formally respond to the Committee’s recommendations,20 although an Indigenous Minority Supply Council (now known as Supply Nation) was subsequently developed in 2009 as part of the National Partnership Agreement on Indigenous Economic Participation agreed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). In addition to the establishment of the supply council, COAG resolved to strengthen ‘government provisions … requiring successful contractors to … implement Indigenous training and employment and supplier strategies‘21. For the Australian Government, the IOP already provided a framework largely consistent with these commitments, although the Government agreed to revise the IOP to further strengthen its implementation.

The Indigenous Opportunities Policy 2011

1.13 The revised IOP, formally introduced in July 2011, required suppliers to government to develop and implement Indigenous Training, Employment and Supplier Plans (IOP Plans) that included commitments on the provision of Indigenous training, employment and business opportunities. IOP plans were to be in place for businesses that win Australian Government contracts over $5 million (or $6 million for construction) in regions where there were significant Indigenous populations.22 Businesses that won contracts to which the IOP applied were to report annually on the implementation of their IOP plans and the results achieved.

1.14 The revised IOP adopted the same thresholds ($5 million for all non-construction contracts, and $6 million for construction contracts) as the 2003 IOP, but where the earlier policies only asked entities to consider and to consult with respect to Indigenous outcomes, the 2011 IOP formally required suppliers to have an approved IOP plan, to implement it and to report against outcomes annually. In the development of the strengthened IOP, one of the initial proposals considered by the Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) was to require all suppliers with contracts over the threshold values to develop and implement approved IOP Plans. However this initial proposal was not supported, and a regional approach was adopted which required the establishment of the IOP regions.

1.15 The rationale for identifying specific IOP regions stemmed from the Singapore-Australia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) which was signed in 2003. International free trade agreements generally require that government procurement practices do not unreasonably restrict the ability of overseas businesses from tendering competitively for contracts, but can include various exemptions to this principle. The SAFTA includes an exemption allowing the use of procurement measures to promote ‘opportunities for Indigenous persons’ noting that ‘…nothing [in the Government Procurement chapter of the agreement] shall prevent Australia from promoting employment and training opportunities for its Indigenous people in regions where significant Indigenous populations exist.’23

1.16 A region was defined as an IOP region if the Indigenous population for the area was equal to or above the national average of three per cent. IOP regions, as at April 2015, are shown in Figure 1.1. In most urban areas of Australia the Indigenous population is lower than the national average, and therefore these areas were generally not identified as IOP regions, although some localised areas within some cities had been identified as IOP regions, for example some parts of western Sydney.

Figure 1.1: Indigenous Opportunities Policy Regions as at April 2015

Source: PM&C.

Note Additional maps, showing some local areas within major cities which were identified to be in IOP regions are included at Appendix 6.

The Indigenous Business Exemption to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules

1.17 In parallel to the development of the revised IOP, the Australian Government also introduced in 2011 an exemption in the CPRs. The Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE) was proposed by the Department of Finance (Finance) in response to some of the criticisms24 of the draft revisions to the IOP proposed in 2010, and was intended to broaden the geographic footprint and the applicable financial thresholds of the initiatives.

1.18 All procurements are required to meet the core principles of the CPRs with higher value procurements also required to meet additional conditions. The exemptions agreed in the CPRs allow, in certain circumstances, procurements over the relevant financial threshold, ($80 000 generally and $7.5 million for construction) to be conducted without requiring the additional conditions to be met and, in effect, allow these procurements to be undertaken under the more streamlined conditions that apply to procurements below the financial thresholds. This can include entities approaching one or more suppliers of their choice to tender without the need to make an open approach to market.

1.19 The IBE is not limited by any regional geographical boundaries, and, accordingly, provides a mechanism for entities to use procurement to deliver outcomes for Indigenous Australians for any procurement above the $80 000 threshold. As Division 2 of the CPRs does not apply to procurements below $80 000, the exemption in effect, allows for the limited tender contracting of Indigenous owned Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) for procurements at any value.

1.20 At the time of its introduction, the objective of the IBE was described as being to:

- provide increased opportunities for greater access to the Australian Government procurement market for all Indigenous SMEs;

- raise awareness among officers undertaking procurement of the (then) Government’s commitment to the Closing the Gap strategy on Indigenous disadvantage; and

- complement implementation of the enhanced IOP administered by the then DEEWR.25

Roles and responsibilities for the Indigenous Opportunities Policy and Indigenous Business Exemption

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

1.21 Responsibility for the overall administration of the IOP initially rested with the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) but was transferred to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) as part of machinery of government changes in September 2013. As a result of these changes PM&C became responsible for Indigenous policy advice and program implementation. In relation to the IOP, PM&C was responsible for:

- determining the IOP regions;

- development of the IOP website and IOP guidelines;

- promotion of the IOP, and responding to requests relating to the IOP;

- reviewing IOP Plans and Implementation and Outcomes Reports;

- monitoring implementation of the IOP by entities and by businesses, including conducting audits of the implementation of a sample of IOP Plans; and

- reporting annually to the government on the outcomes achieved under the policy.

Department of Finance

1.22 Finance’s core functions include: maintaining the financial framework, providing advice on the Australian Government’s procurement policy framework, and improving procurement outcomes through whole of Australian Government arrangements. While Finance is responsible for the operation of the overall procurement framework it does not have an explicit role in relation to specific PCPs, or targeted exemptions, or their use, other than in relation to procurement directly managed by Finance.

Role of procuring entities

1.23 Non-corporate Australian Government entities are required to adhere to the CPRs, including the requirements to conduct non-discriminatory, and where possible, competitive procurement. Entities are also expected to contribute to broader policy outcomes by appropriately applying procurement connected policies and in the appropriate use of relevant CPR exemptions in their procurement activities.

Supply Nation

1.24 Supply Nation (formerly known as the Australian Indigenous Minority Supply Council) is a not-for-profit organisation which seeks to:

- facilitate the integration of Indigenous businesses into the supply chain of private sector corporations and government entities; and

- foster business to business transactions and commercial partnerships between corporate Australia, government entities and Indigenous business.

1.25 Supply Nation receives some funding from the Australian Government as well as generating membership fees from corporate and government entities. As at April 2015, 336 businesses were certified as Indigenous suppliers and 35 Australian Government entities were registered with Supply Nation as members. A further 137 businesses were corporate members and 4 were state or local government entities.

Indigenous Procurement Policy implementation

1.26 In May 2015, in part as a response to the Creating Parity26 report and its recommendations, the Australian Government released guidelines for the new Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) which commenced 1 July 2015.

1.27 The key changes introduced by the IPP include:

- the adoption of a target of 3 per cent27 of all new procurement by Australian Government portfolios from Indigenous owned businesses, and for achievement against the targets to be reported publicly;

- for the purpose of contributing to the portfolio targets, contracts with Indigenous businesses, sub-contracts entered into with an Indigenous business by a supplier to government, and Joint Ventures where 25 percent equity is held by Indigenous Australians, are included. Additionally Indigenous suppliers with multi-year contracts contribute to the target in each year of the contract and purchases made by credit cards also can be counted towards the target.

- an obligation for procuring entities to:

- set aside some contracts, for which the first option to tender goes to Indigenous businesses; and

- include a range of ‘minimum Indigenous participation requirements’ in the procurements they undertake;

- a requirement for suppliers to report against the minimum Indigenous participation requirements to the procuring entity as a component of their contract, rather than to PM&C; and

- Supply Nation developing a new, publicly available listing of Indigenous businesses that include 50 per cent owned businesses.

1.28 These changes have the effect of replacing the IOP but not the IBE which will continue to be in place. A transitional period requires entities to monitor commitments made by businesses under previously approved IOP plans and which are required to be implemented under contracts which continue beyond 1 July 2015. PM&C anticipates that the IPP will increase the volume of opportunities created for Indigenous Australians and support improved monitoring of the extent to which Indigenous owned businesses are included in the supply chains of the Australian Government. PM&C also anticipates that use of the IBE will increase as a result of the IPP. As the IPP took effect from 1 July 2015 the ANAO has not examined its proposed operation in detail, but has considered aspects of it insofar as the experience of the IOP and IBE is relevant to the implementation arrangements of the IPP.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.29 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of procurement initiatives to support opportunities for Indigenous Australians.

1.30 To conclude against this objective the ANAO adopted the following broad criteria:

- the Indigenous Opportunities Policy, (IOP) was effectively administered and monitored by PM&C and used appropriately by entities;

- the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE) under Division 2 of the CPRs is appropriately used by entities and supported by relevant guidance, monitoring and reporting; and

- the effectiveness of the IOP and the IBE in terms of supporting Indigenous economic participation was periodically analysed by PM&C and Finance and the government provided with this analysis.

1.31 The scope of the audit included:

- the application of the IOP between July 2011 and March 2015 by selected Australian Government entities and its overall administration by PM&C, and formerly by DEEWR; and

- the use of the IBE in the CPRs by selected Australian Government entities and support for the use of the exemption by Finance since 2011.

1.32 The main audited entities were the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Department of Finance. In order to assess the practical application of the policies, the ANAO also examined relevant procurement activities of the following entities:

- Department of Defence (Defence);

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO);

- Department of Human Services (DHS);

- Department of Employment (Employment);

- Department of Industry and Science (Industry); and

- Department of Education and Training.

Audit methodology

1.33 The audit methodology included an examination of the relevant policy and operational documents held by PM&C relating to the IOP and the IPP, and those held by Finance relating to the IBE; an analysis of procurements and procurement related approaches and communication made by a range of entities including in relation to the IOP and the IBE; analysis of AusTender data and IOP outcomes reports; and interviews with a number of Indigenous businesses and Australian Government entities.

1.34 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $384,900.

Structure of the report:

1.35 The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

Table 1.1: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Application of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy |

This chapter outlines the key elements of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP), the roles and responsibilities allocated between procuring entities and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), the guidelines developed and the issues relating to the application of the IOP by selected entities. |

|

3. Use of the Indigenous Business Exemption. |

This chapter outlines the key elements of the Indigenous Business Exemption (IBE), the roles the Department of Finance (Finance), and the extent to which the exemption has been used by entities. |

|

4. Monitoring outcomes |

This chapter examines how activity under the IOP and the IBE has been monitored, assessed and reported to government. |

2. Application of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy

This chapter outlines the key elements of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP), the roles and responsibilities allocated between procuring entities and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), the guidelines developed and the issues relating to the application of the IOP by selected entities.

Introduction

2.1 In 2013–14 the Australian Government conducted 66 047 procurements to purchase goods and services worth approximately $48.9 billion.28 The Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP) sought to leverage this procurement activity to create greater opportunities for Indigenous people where government procurement occurred in regions which have Indigenous populations above the national average.29 Expected broad outcomes from the IOP related to improved training and employment opportunities for local Indigenous populations and increased participation by Indigenous businesses in supplying goods and services to government contractors. In developing the framework for the implementation of the IOP, a range of factors were considered which shaped the nature of implementation arrangements. This chapter examines the development of the IOP framework, the roles and responsibilities of Australian Government entities and the application of the IOP. While the IOP has largely been replaced by new policy arrangements that commenced from 1 July 2015, some aspects of the IOP have carried through and the overall experience of its implementation is relevant to informing the implementation of the new Indigenous Procurement Policy.

The Indigenous Opportunities Policy

2.2 The IOP initiative sought to create indirect opportunities by requiring suppliers (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) to government entities to employ and train Indigenous people and to contract with Indigenous owned businesses as commercial suppliers in contracts worth over $5 million ($6 million in relation to construction). Suppliers that won government contracts to which the IOP applied were to have approved Indigenous Training, Employment and Supplier Plans (IOP Plans) in place, which outlined how they intended to provide opportunities for Indigenous Australians during the period of the contract.

The framework for implementing the Indigenous Opportunities Policy

2.3 As noted in Chapter One, the IOP was implemented from 1998 with revisions made at various points to further refine it. Overall the design of the IOP, as it operated from 2011, required the balancing of a number of competing tensions. These included the:

- aspiration that tangible opportunities were generated for Indigenous Australians in the locations where government contracts occurred, and as a direct result of government procurement and contract terms;

- aspiration that contracted suppliers implemented strategies relevant to local circumstances so that Indigenous opportunities were maximised;

- policy imperative to reduce red tape, and/or not add red tape unless the benefits outweighed the cost;

- need for procurement processes to be time efficient (that is, limit any delays arising from any additional procurement processes);

- desire to limit any additional burden placed on procuring entities and, in particular, on procurement staff; and

- requirements derived from the Singapore–Australia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA).30

2.4 Key features of the final IOP model, agreed by the Australian Government, included the allocation of the majority of all implementation and monitoring responsibility to a single entity known as the IOP Administrator, with fewer responsibilities placed on the Australian Government entities undertaking procurement activities. Initially the IOP Administrator was the former Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) but since September 2013 the role was fulfilled by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C). The responsibility placed on entities conducting procurements to which the IOP applied was limited to taking steps that ensured suppliers awarded contracts had approved IOP plans in place where applicable.

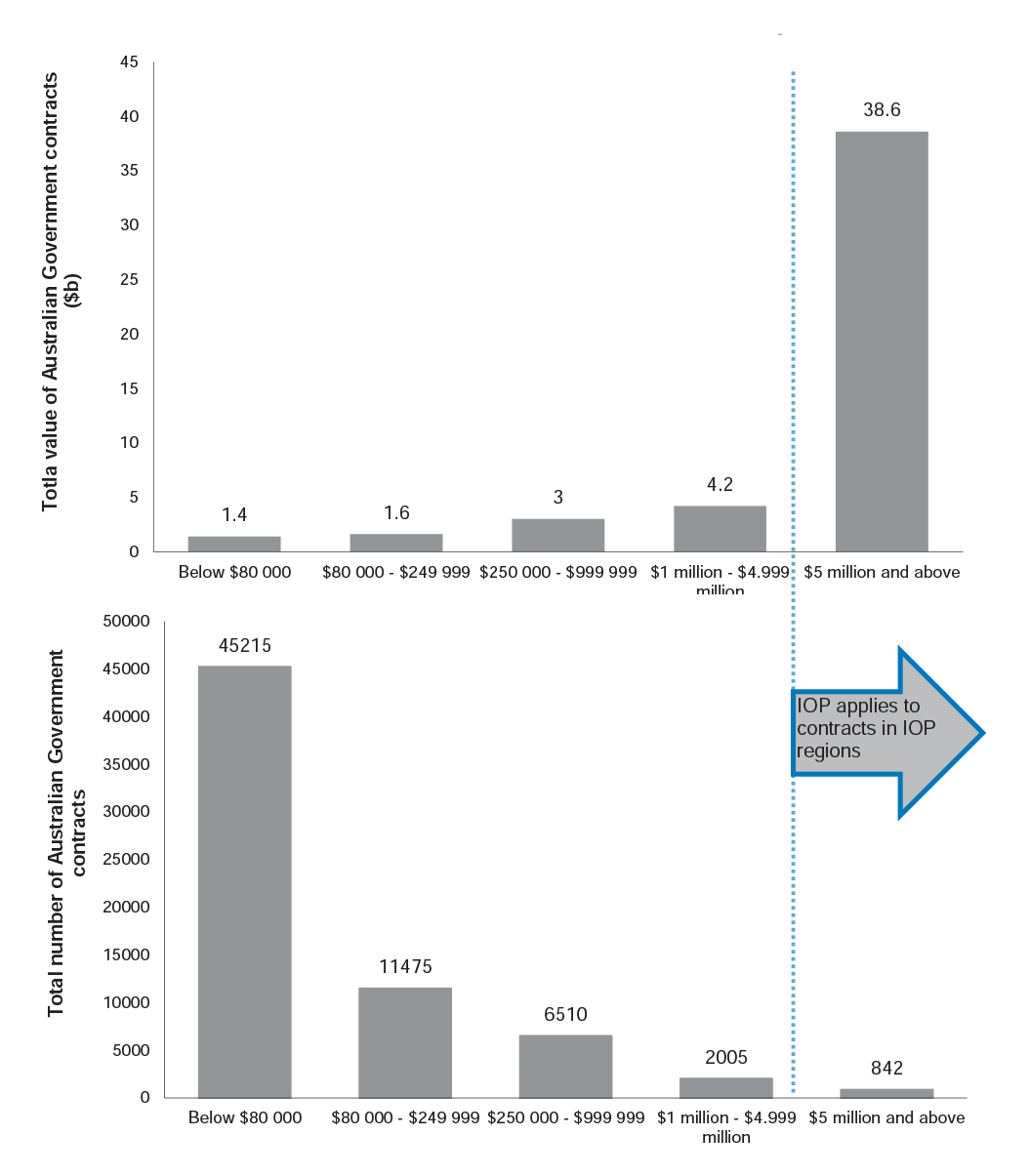

2.5 Other key features included the application of a financial threshold of $5 million ($6 million for construction contracts) above which IOP requirements applied and the limiting of the IOP to certain geographic regions. By establishing these relatively high financial thresholds, the IOP sought to target larger businesses potentially more able to accommodate the IOP obligations. However, this threshold also had the effect of limiting the IOP to relatively few potential contracts. Of the 66 047 procurements undertaken by Australian Government entities in 2013–14, only 842 were for amounts above the financial threshold for the IOP, across all regions, as shown in Figure 2.1. Available data does not allow the ready identification of how many of these 842 contracts were in IOP regions, but as there were only 197 IOP Plans approved31 since 2011, it is reasonable to assume that only a minority of these contracts related to the IOP regions.

Figure 2.1: Australian Government contracts by value and volume in 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.6 Additionally, the geographic approach of the IOP restricted the contracts to which the IOP was applicable to those areas where the contracted activity occurred in regions with higher than average Indigenous populations. This feature further reduced the number of contracts to which the IOP applied. The IOP regions are shown in Chapter 1 (Figure 1.1).

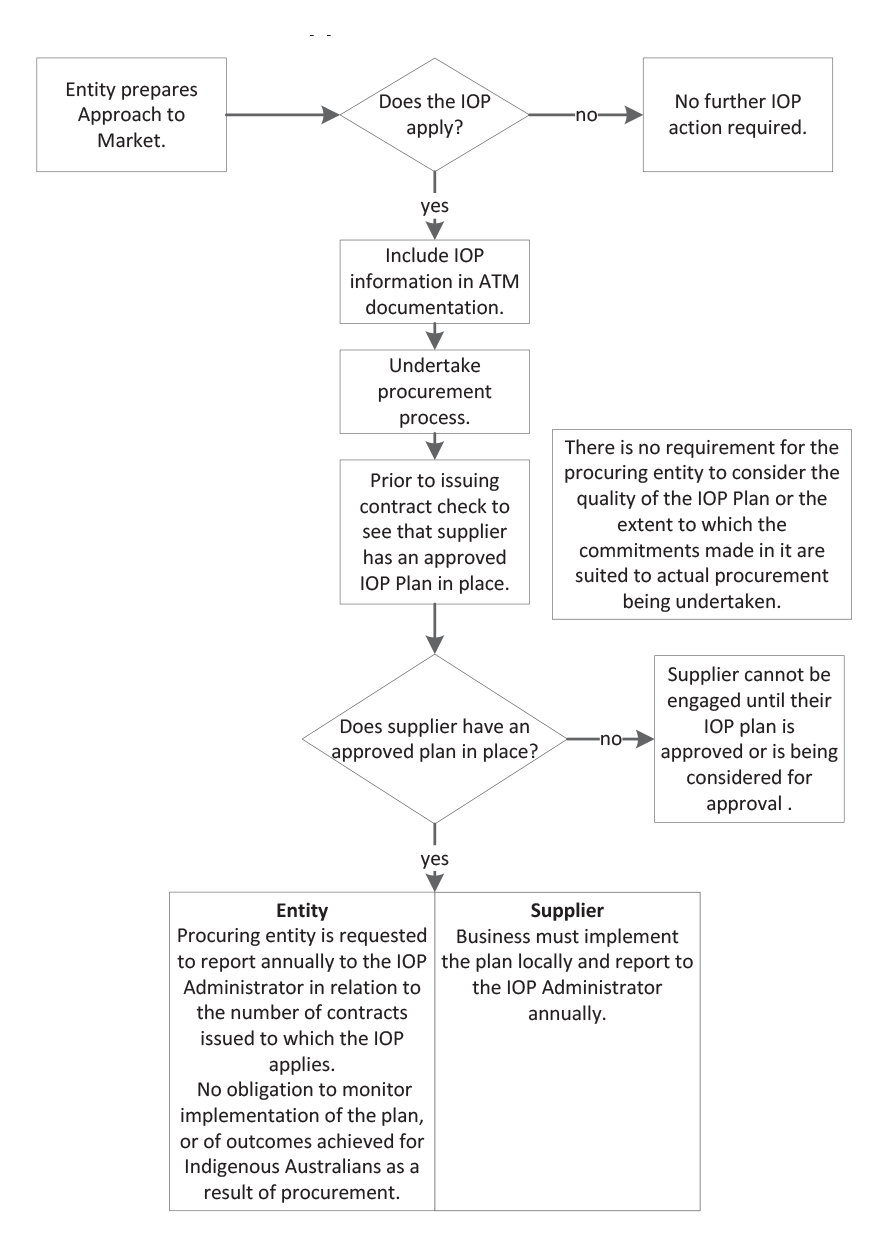

2.7 Entities undertaking procurement, PM&C and businesses tendering for and executing government contracts each played roles in the IOP. The IOP related processes which were required to be followed by procuring entities and their suppliers are shown in Figure 2.2. The IOP related processes which were required to be followed by PM&C and the businesses seeking to tender or supply services to procuring entities are shown in Figure 2.3. Some of the steps in the IOP processes could occur concurrently or precede others. For example, businesses could submit their IOP plans to PM&C at any time and did not need to wait for an Approach to Market (ATM) to be issued.

Figure 2.2: Indigenous Opportunities Policy Flow Chart for procuring entities and suppliers

Source: ANAO based on the IOP Guidelines.

Figure 2.3: Indigenous Opportunities Policy flow chart for the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and suppliers

Source: ANAO based on the IOP Guidelines.

2.8 Suppliers were able to submit their proposed plans to PM&C either prior to or during a tender process or, in some cases, once they had been advised they were the successful tenderer. Businesses contracted under IOP contracts were to implement their IOP Plans locally and report on the outcomes achieved to PM&C annually. The design of the IOP noted that businesses which failed to implement or report on their plans would be deemed ‘non-compliant’, have their IOP Plans suspended by PM&C, and would not be permitted to win future Australian Government contracts to which the IOP applied.

2.9 PM&C maintained the list of suppliers with approved IOP Plans but the onus was on procuring entities to check the list of businesses with approved plans in place prior to issuing a contract. However there was no other mechanism in place to alert an entity that a previously approved plan had been suspended or had expired, other than by contacting PM&C on a case by case basis. Similarly, where a supplier had been deemed to be no longer eligible for future contracts, as a result of non-compliance, entities relied on being advised of this by PM&C. Procuring entities were not required to incorporate the commitments made in the IOP Plan into the contract with the supplier, nor to monitor the outcomes generated for Indigenous Australians through their procurement activities. Under the Indigenous Procurement Police (IPP), entities are now required to include minimum Indigenous participation requirements as a component of some contracts32, to monitor compliance with those agreed terms, and to record the contractor performance in a central database.

Geographic application of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy

2.10 The decision to restrict the IOP’s application to some regions and not others was originally based on an exemption in the Singapore Australia Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA). International free trade agreements generally require that government procurement practices do not unreasonably restrict the ability of overseas businesses from tendering competitively for contracts, but can include various exemptions to this principle. As outlined in paragraph 1.15, the SAFTA included an exemption allowing the Australian government to use measures to promote ‘employment and training opportunities for its Indigenous people in regions where significant Indigenous populations exist’. As a result, the implementation of the IOP was restricted to geographic regions where the Indigenous population is equal to or above the national average.

2.11 A 2014 study into the geographic spread of economic activity in Australia33 showed that the vast majority of economic activity occurred in urban areas, and that within urban areas there was a further concentration of activity in Central Business District (CBD) areas. While there were some areas within major urban areas which had been designated as IOP regions, generally most urban areas were not included in the IOP.

2.12 Furthermore, 2011 census data indicates that 27 per cent of Indigenous Australians resided outside of the regions in which the IOP applied. Similarly, Indigenous businesses were distributed both inside and outside IOP regions. For example, Indigenous Business Australia data reflects that 29 per cent of its current business loan clients were located in major cities34 as at May 2015, and may therefore have been located outside the IOP.

2.13 The SAFTA exemption specifically refers to procurement efforts to promote employment and training for Indigenous people in some regions. Advice provided to DEEWR in 2009 advised that the SAFTA does not prevent the Australian Government from using procurement to promote the development of an Indigenous business sector by targeted preferential use of Indigenous businesses, so long as they were SMEs. In this respect there is a specific clause in the SAFTA that allows Australian Government procurement policies to promote industry development including through measures to assist Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs) (without specifying any particular type) to gain access to the government procurement market. However, the option to ‘un-couple’ the employment component from the business support component of the IOP, in order to maximise opportunities for Indigenous businesses, was not canvassed amongst entities in developing the IOP model, nor was an ‘un-coupled’ proposal taken to the Australian Government for consideration.

2.14 In view of the experience of entities to date, there would be merit in PM&C further reviewing the regional approach to determine the conditions under which the mandatory Indigenous participation requirements are most effectively applied under the Indigenous Procurement Policy.

Recommendation No.1

2.15 In order to inform implementation arrangements for the Indigenous Procurement Policy the ANAO recommends that PM&C, in consultation with other government entities, review the regional approach of the IOP and, as appropriate, provide advice to the Australian Government on potential alternative models by which the proposed minimum Indigenous participation requirements may be most effectively applied.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet:

2.16 PM&C agrees with this recommendation. On 25 May 2015, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs and the Minister for Finance, released policy guidelines for a new Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP). The IPP will take effect on 1 July 2015 and will replace the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP). The IPP was developed through extensive engagement with government entities and the regional approach that applied under the IOP was carefully reviewed. As a result of this review, the IPP takes a new approach to achieve better procurement outcomes for Indigenous businesses and simpler administration for government entities. Under the new approach, all contracts in remote Australia will be set aside for Indigenous businesses, together with all contracts valued between $80,000 and $200,000. The detailed IPP guidelines include clear guidance for agencies to assist them to determine whether a contract is in remote Australia.

Department of Finance:

2.17 Supported. The new Indigenous Procurement Policy, released on 25 May 2015, was developed by PM&C in close consultation with Finance and other key procuring entities. The regional focus of the previous policy has been replaced with minimum Indigenous participation requirements for high value contracts in eight key industry sectors known to have high Indigenous employment. Additionally, the new policy recognises an opportunity for additional Indigenous employment in remote areas, and includes additional requirements for suppliers delivering contracts in those areas.

2.18 The IPP, implemented on 1 July 2015, includes35 minimum requirements for Indigenous participation (to be negotiated relating to either Indigenous employment or Indigenous supplier volumes, or both) for high value contracts (over $7.5 million) where:

- more than half of the contract activity relates to industries identified by the policy;36 or

- where the contracted activity occurs in a designated ‘Remote Area’37.

2.19 Additionally the IPP states that all other contracts (below $7.5 million) ‘should include a requirement for the contractor to use reasonable endeavours to increase their employment of Indigenous Australians and their use of Indigenous suppliers in their supply chains in the delivery of the contract’. Although there are some differences to the previous IOP requirements, other aspects are broadly similar and periodic assessment of entities’ experience in implementation of the IPP requirements will be beneficial.

Administration of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

2.20 The role of IOP Administrator was performed by PM&C between September 2013 and 30 June 2015. The main responsibilities of the IOP Administrator were to:

- determine the IOP regions;

- develop the IOP website and IOP guidelines;

- promote the IOP, and respond to requests relating to the IOP;

- review IOP Plans and Implementation and Outcomes Reports;

- monitor implementation of the IOP by entities and by businesses, including conducting audits of the implementation of a sample of IOP Plans; and

- report annually to the government on the outcomes achieved under the policy.

2.21 While the IPP effectively replaced the IOP from 1 July 2015, PM&C has continued to undertake similar roles in relation to the IPP, with the exception of the review of IOP Plans and related outcomes reports.

2.22 The ANAO considered the effectiveness of some of the key responsibilities of PM&C in the role of IOP Administrator, including:

- developing the IOP website and IOP guidelines;

- promoting the IOP, and responding to requests relating to the IOP;

- reviewing IOP Plans and Implementation and Outcomes Reports; and

- monitoring implementation of the IOP by entities and by businesses.

2.23 PM&C’s reporting to government is examined in Chapter 4.

Developing the Indigenous Opportunities Policy website

2.24 To support entities, PM&C (and previously the then DEEWR) developed information that outlined how to apply the policy and made this publicly available on the Department of Employment38 (Employment) website. This website had a dedicated Indigenous Opportunities Policy section which, in addition to providing the IOP guidelines, presented information for both entities and suppliers to assist in determining IOP eligibility and in applying the policy. Most notably, the website provided the following supporting information:

- maps showing IOP regions; (see Chapter 1 Figure 1.1 for a copy of the national IOP map. Additional maps are available for each major urban area, showing localised areas within which the IOP applied, some of which are included in Appendix 6 of this report)

- a list of potential resources for developing an IOP Plan;

- a MyPlan (the IOP’s online information system) user guide;

- guidelines on the IOP for entities; and

- guidelines on the IOP for potential suppliers.

2.25 Until November 2014 a list of organisations with approved IOP Plans was available on the IOP website, although this was removed by PM&C in order to encourage procuring entities to contact the department and request a current IOP compliance check for specific businesses to be provided to them. Overall the website provided relevant information about the IOP.

Promoting the Indigenous Opportunities Policy

2.26 PM&C was responsible for promoting awareness and understanding of the IOP. This promotion occurred through the provision of information on the IOP website for businesses and entities. In addition, PM&C (and DEEWR before it) conducted the following activities to promote the policy, including:

- public information sessions, jointly presented with Supply Nation;

- one-on-one presentations to entities and inter-departmental committees;

- development of content on the IOP for inclusion in Department of Finance procurement newsletters;

- distribution of IOP brochures;

- responding to questions and request from entities and businesses received through the IOP mailbox; and,

- correspondence to all portfolio secretaries in March 2012 to inform them of reporting requirements under the IOP.

Indigenous Opportunities Policy Guidelines

2.27 In addition to the website and other information, a key source of advice to entities was the IOP guidelines initially developed by DEEWR and maintained by PM&C. The IOP guidelines provided key information, including:

- requiring implementation of the policy by Australian Government entities for all relevant Approaches to Market (ATMs) after 1 July 2011;

- defining the regions across Australia to which the IOP applied (IOP regions) as those where the proportion of Indigenous Australians was equal to or higher than three per cent (the national average);

- clarifying that a review of information provided on the IOP website by non-corporate Commonwealth entities was sufficient to meet the requirement to consult with PM&C (minimising the administrative load placed on the entities);

- requiring businesses responding to Australian Government ATMs, to which the IOP applied, to have, or to develop, an IOP Plan approved by PM&C;

- requiring businesses to implement their IOP Plans locally should they have won such a contract and report on outcomes achieved to PM&C annually; and

- indicating that businesses not meeting the requirements of the IOP were not eligible from tendering for future IOP contracts.

2.28 Ideally, program guidelines should impart consistent advice and information so that entities are able to interpret and apply the policy correctly and consistently. In this regard the IOP guidelines could have been improved by adopting a more consistent approach to describing how contracted activity related to the geographic regions, as discussed in the following section.

Clarification of the geographic applicability of the Indigenous Opportunities Policy in the guidelines

2.29 As noted in paragraph 2.10, the IOP only applied in certain geographic regions where significant Indigenous populations resided. The regional approach to the IOP added a level of complexity to its implementation and reduced the visibility of entity compliance. Accordingly, the guidelines needed to provide clarity so that businesses and entities could easily determine if the IOP ought to be applied. The ANAO observed that the guidelines provided a number of possible interpretations regarding the regions where the IOP was to be applied. In particular the guidelines variously indicated that the IOP applied:

- where projects involved expenditure over $5 million ($6 million for construction) in regions where there were significant Indigenous populations; (emphasis added)

- to a contract or contracts each valued at over $5 million ($6 million in construction) for which the resulting activities or services took place in a region or regions with a significant Indigenous population; (emphasis added)

- where an approach to market was likely to result in a contract or contracts each valued at over $5 million (or $6 million for construction) where the main location of the activity or service under the contract/s would take place in a region with a significant Indigenous Australian population; (emphasis added)

- where a project was undertaken in a number of regions, some with and some without a significant Indigenous Australian population, a business was only obligated to implement its Plan in the region(s) with a significant Indigenous Australian population. Generally, however, the Policy should have applied to contracts where the dominant purpose was to commission work in relevant regions. (emphasis added)

2.30 The ANAO observed several cases where the application of the policy varied according to the adoption of one or other of the possible interpretations of the above approaches. In one case determining the ‘main location’, and the ‘dominant purpose’ was not straightforward because the services were provided by phone from call centres. The call centres were physically located outside the IOP regions, but many recipients of the services, and therefore the location where the services were delivered to, were inside the IOP regions. In this respect while the ‘dominant purpose’ of the contract could be readily interpreted as being to provide services to clients within IOP regions, the ‘main location’ where the employment and training opportunities were predominantly created, was outside an IOP region. In this example, the IOP was not applied.

2.31 In another case a supplier was contracted by an entity to deliver services in multiple locations, some of which were in IOP regions. In this case, the majority of the value of the contract was allocated to non-IOP locations, and therefore the ‘main location(s)’ were considered to be outside the IOP regions. However, the value of services delivered in IOP regions, although being a minority part of the contract value, was still over $5 million. In this case the IOP was not applied by the entity and the supplier did not have an approved IOP plan. In general, application of the IOP by entities was variable as discussed in more detail in paragraph 2.41.

Consistency of definitions in reported outcomes