Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Policing at Australian International Airports

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the Australian Federal Police's (AFP’s) management of policing services at Australian international airports. In order to form a conclusion against this audit objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examined if:

- the transition to the 'All In' model of policing at airports (Project Macer) had been delivered effectively;

- appropriate processes are in place for managing risk and operational planning;

- effective stakeholder engagement, relationship management and information sharing arrangements are in place;

- facilities at the airports are adequate and appropriate; and

- appropriate mechanisms for measuring the effectiveness of policing at airports have been developed and implemented.

Summary

Introduction

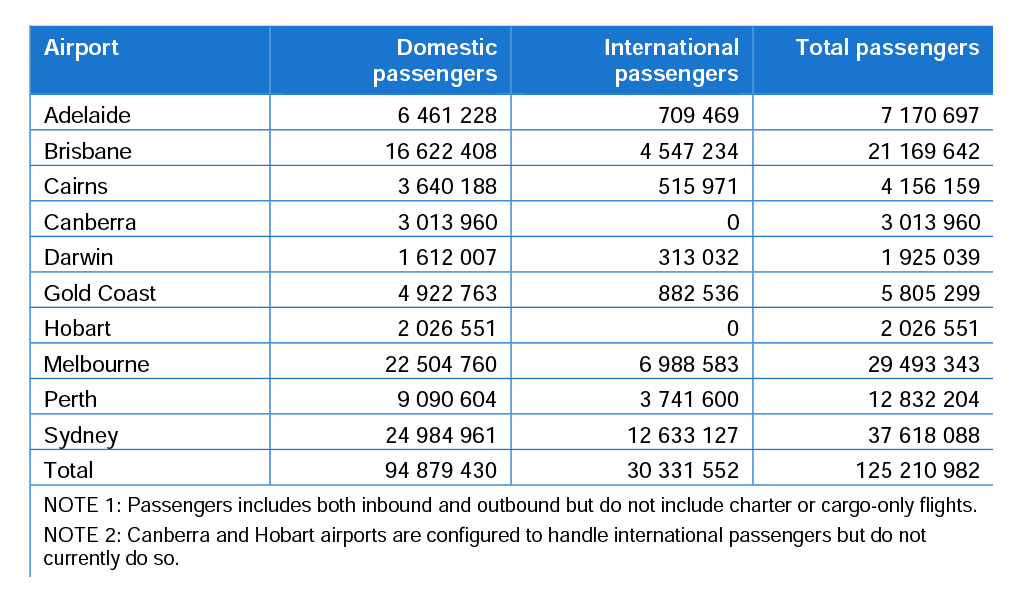

1. Australia’s international airports are important transport hubs and commercial centres, through which millions of Australians and foreign nationals pass every year. It has been estimated that in 2011, Australia’s airports generated a total economic contribution to Australia of around $17.3 billion.1 There are 177 ‘security controlled’ airports in Australia2, with the highest level of security controlled airports known as ‘designated airports’. Currently, there are 10 designated airports. Table S 1 lists these airports, and the number of passengers using them in 2012−13.

Table S.1: Current designated airports and passenger numbers, 2012−13

Source: Monthly Airport Traffic Data, Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics.

2. The Aviation Transport Security Regulations 2004 (ATSRs) require designated airports to have a counter terrorist first response (CTFR) capability3 and provide that members of a counter terrorist first response force must be either members of the Australian Federal Police (AFP) or the police force in the state or territory in which the airport is located. This requirement recognises that the response to a terrorist attack or incident may require the use of weapons and the power of arrest, which are only available to police officers.

3. In law enforcement terms, international airports represent a complex and evolving challenge. As the events of 11 September 2001 in the United States demonstrated, they can be the source or focus of major terrorist attacks. Airports are the point of entry into Australia for criminals, potential terrorists, illicit drugs and other prohibited imports with consequential links to serious and organised crime both internationally and domestically. Aside from their role as transport hubs, the trend towards the development of airports as major retail centres provides a vulnerability for lower-level crime such as shoplifting and theft. They may also involve the local criminal milieu, as the murder of a motorcycle gang member at Sydney Airport in March 2009 demonstrated.

4. Policing at airports is currently delivered through the AFP’s Aviation function4 which is headed by the National Manager Aviation (NMA), an officer of Assistant Commissioner rank. At 15 November 2013, there were 618 sworn officers5 at the 10 designated airports and the Aviation function’s 2012−13 budgeted expenses were $74.1 million.

History of policing at airports

5. Until 2005, policing of airports was undertaken by Australian government agencies (the Commonwealth Police, the AFP and the Australian Protective Services), with the community policing elements undertaken by state and territory police forces. Following a review of airport security and policing in 2005, a ‘Unified Policing Model’ (UPM) was introduced. Under the UPM, the Australian Government, through the AFP, met the cost of policing, but the actual workforce comprised approximately 450 AFP Protective Service Officers6 (PSOs) to deal with Counter Terrorist First Response and a notional 328 officers seconded7 from state and territory police forces to deal with community policing.

6. Policing at the designated airports was reviewed again in 2009. This review (known as the Beale review) concluded that the UPM was flawed and recommended that all airport police officers should be sworn employees of the AFP and capable of undertaking both counter terrorism and community policing functions. This approach was termed the 'All In' model. The then Government accepted this recommendation and the process of moving from the ‘unified’ model to the 'All In' model was completed in June 2013.

7. Under the National Counter Terrorism Plan, agreed between the Australian and state and territory governments, state and territory governments have responsibility for the operational response to a terrorist incident in their jurisdiction. Under the 'All In' model, this responsibility is acknowledged in Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) between the AFP and the state and territory police forces, with the AFP providing CTFR until the relevant police force is able to take control of the response. The MOUs also allow for state and territory police forces to provide operational support for non-terrorist incidents, to be determined on a case by case basis. In addition, should the need arise, the AFP could draw upon its own resources located in its main office in the state or territory. These arrangements provide a ‘surge’ capacity for the AFP airport police when responding to major incidents, whether or not they are terrorist-related.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the AFP’s management of policing services at Australian international airports. In order to form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO examined if:

- the transition to the 'All In' model of policing at airports (Project Macer) had been delivered effectively;

- appropriate processes are in place for managing risk and operational planning;

- effective stakeholder engagement, relationship management and information sharing arrangements are in place;

- facilities at the airports are adequate and appropriate; and

- appropriate mechanisms for measuring the effectiveness of policing at airports have been developed and implemented.

Overall conclusion

9. Australia’s 10 designated airports cater to more than 125 million domestic and international passengers annually. As both transport hubs and major commercial centres, the airports present a complex and evolving law enforcement environment. Through its Aviation function, the AFP is responsible for delivering a full range of counter terrorism and community policing services at these airports. As at November 2013, 618 AFP officers were employed across the airports.

10. Following the transition from the previous ‘hybrid’ model to the 'All In' model, the AFP is effectively managing the delivery of policing services at Australia’s international airports. The transition process (known as Project Macer) was well managed and met its objectives.8 As a result of the Project, 274 PSOs and 71 former state/territory police officers successfully became sworn AFP officers.9 The Project was completed in less than the estimated five years and at a cost of $16 million, significantly less than the anticipated $32 million. The 'All In' model has delivered resource efficiencies resulting in annual savings of the order of $10 million (from $84 million in 2009−10 to $74.1 million in 2012−13).

11. The organisational arrangements in place at airports are sound, with a clear command structure at each airport headed by an Airport Police Commander. Internal reporting mechanisms are in place and there is a clear alignment between the AFP’s strategic and functional plans and individual airport action plans. However, there is no clear linkage between the AFP’s planning for its Aviation function and external assessments of the threat and risk environments across Australia’s aviation sector. Although the AFP advised that a number of factors have been taken into account in determining the agency’s resourcing levels at individual airports, increases or decreases in staffing levels have been largely historical and based on the funds available to the Aviation function. An explicit assessment of the inherent security risks presented by each airport and the nature and level of criminality have not formed part of that determination. The AFP advised that it is now developing a resourcing model that will take into account all relevant factors in determining staffing levels at each airport. Completion and implementation of such a model would provide the AFP with a more rigorous and transparent approach to resource allocation across airports.

12. The AFP’s Aviation function maintains a high operational tempo. On average, in each year over the last three financial years, the AFP has dealt with 21 146 incidents and made 2621 apprehensions and 312 arrests across the 10 airports. The number of arrests has increased by 42.6 per cent over the three year period from July 2010 to June 2013.10 The offences ranged from offensive and disorderly behaviour to matters relating to aviation and aircraft security.

13. The legislative framework applying at airports is complex, with officers required to use and apply both Commonwealth and state and territory legislation. Across the 10 airports, there are some 300 relevant pieces of state or territory legislation and more than 400 relevant provisions of Commonwealth legislation. Although state and territory police forces provide training in their respective legislation, the duration of this training varies considerably from state to state, and from zero to 10 days. There would be benefit in greater consistency in training both in terms of duration and content following an assessment of the training requirements.

14. The Aviation function has developed and maintains good relationships with a wide range of stakeholders and the AFP is appropriately represented on a number of local and national government and aviation industry bodies. The effectiveness of these relationships was supported by the responses to annual surveys commissioned by the AFP, as well as the ANAO’s consultations with state and territory police forces and airport operators. However, some airport operators stated that they did not have a clear understanding of the Aviation function’s strategy for policing. The AFP has now agreed that it will disseminate its Aviation Doctrine11 to provide stakeholders with a clearer understanding of the AFP’s overall aviation policing strategy.

15. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at securing greater consistency, both in terms of content and duration, of the training in state and territory legislation provided to AFP officers by the respective state and territory police forces.

Key findings by chapter

Transition to a new workforce model (Chapter 2)

16. At the time of the Beale review in 2009, there were 225 Airport Uniformed Police (AUP) officers (that is, officers seconded from state and territory police forces)12 and 445 PSOs at the 10 designated airports. Under the new model, all airport police were required to be sworn police officers. The 670 officers were given three options. They could:

- transition to sworn status and remain in their current positions;

- return to their ‘home’ police jurisdiction (for seconded officers) or move to an available position elsewhere in the AFP (for PSOs); or

- leave the AFP through voluntary redundancy or resignation.

The AFP managed this transition through a project which was named Project Macer. The project and the related sub‑project, Project Guild13 were managed using the PRINCE2 project management methodology.

17. A major component of these projects was providing training to those officers who wanted to make the transition to fully sworn AFP officers. AFP training is undertaken at the AFP College in Barton, ACT. In recognition of the fact that officers already had experience working in the airport environment or as officers of state or territory police forces, the AFP modified its standard recruit training program to recognise this prior learning.

18. In total, 274 PSOs and 71 AUP officers successfully transitioned to sworn status, 115 PSOs were redeployed elsewhere in the AFP and 100 PSOs resigned, retired or took voluntary redundancy.

19. Projects Macer and Guild had originally been expected to take between three to five years and cost an estimated $32.7 million. They were completed in a little under four years at a reported cost of $16.1 million. The projects have delivered substantial savings to the AFP with the total cost of AFP staff at the 10 designated airports falling by almost 12 per cent from $84 million in 2009−10 to $74.1 million in 2012−13.14 Other benefits include a single command structure, improved stakeholder engagement, resource efficiencies and development of policing skills.

20. AFP officers at airports use and apply both Commonwealth and state and territory legislation and powers. Across the 10 airports, there are more than 400 relevant provisions of Commonwealth legislation and some 300 relevant pieces of state or territory legislation. While Commonwealth legislation contains provisions to deal with the most serious types of offences (such as murder and terrorism related offences), most ‘community policing’ powers and offences are found in state and territory legislation.

21. The AFP provides its officers with training in relation to Commonwealth legislation. Training in relevant state and territory legislation is provided by the police force in each jurisdiction in accordance with agreements between the AFP and each state and territory police force. There was significant variation in the duration of this training, varying from none in Queensland to 10 days in Western Australia. The duration and content of the training provided is ultimately a matter for the respective police forces. However, there is scope for the AFP to approach state and territory police forces with a view to jointly reviewing the training provided by each jurisdiction in order to achieve greater consistency and better support for airport officers.

Management of AFP Airport Operations (Chapter 3)

22. At each of the 10 designated airports, AFP officers are commanded by an Airport Police Commander (APC). There are a range of internal and external committees at both the local and national levels in which the AFP is a regular participant. There are clear linkages between the national AFP Strategic Plan, the Aviation function’s functional business plan and individual airport action plans, although six airports plans were incomplete15 at the time of the audit. Similarly, the Aviation function’s Risk Assessment Treatment Plan (RATP) is aligned with the overall AFP Strategic Risk Profile.16 While there is alignment between internal AFP planning documents, there is little consideration of the assessment of broader risks and threats to Australia’s aviation sector prepared every two years by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD).17 The AFP advised that while the decision to locate the AFP at the 10 designated airports was taken by government, the AFP is responsible for resourcing each airport. Currently, there is no explicit model for determining the AFP’s overall resource allocation to the Aviation function nor relative resourcing levels at the individual airports, based on an assessment of risks.

23. In the past, factors such as the need to meet specified response times, airport opening hours and the working arrangements provided for in the AFP Enterprise Agreement have been taken into account but increases or decreases in staffing levels were largely historical and based on the funding available to the Aviation function. In response to the audit, the AFP advised that it is developing a resourcing model that will also take into account risks, threats, levels of criminality, passenger and aircraft movements and airport geospatial data.18 The completion and implementation of this model would provide a more rigorous and transparent approach to resource allocation across airports. In this context, there would be value in the AFP drawing upon work undertaken in 2010 by DIRD to assess the threat and risk environment at each of the 10 designated airports

24. Under the terms of the 2005 Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreement, state and territory police forces agreed to provide police officers to participate in Joint Airport Intelligence Groups (JAIGs) and Joint Airport Investigation Teams (JAITs).19 In practice, state and territory police forces have not consistently provided these resources: in 2012−13, only four of 10 state/territory police forces fully met the commitment with the equivalent number for JAITs being two of five. Given the agreements between governments on these matters, there would be benefit in the AFP continuing to work with state and territory police forces to address these shortfalls in resource commitments.

25. The AFP’s Intelligence function has intelligence analysts embedded in JAIGs at each airport and these arrangements are well established. The Intelligence function produces a range of useful strategic, operational and tactical intelligence products which relate to the AFP’s counter terrorist, serious and organised crime and community policing roles at the airports. ANAO examination of the Intelligence function’s fortnightly aviation significant operations reports for 2012−13 demonstrated that the work of the JAIGs leads to practical outcomes, including arrests, summonses and cautions.

The Aviation Function’s Performance (Chapter 4)

26. The AFP collects workload statistics relating to the incidents it responds to at airports and the outcome of these incidents (which may include no further action, apprehension or arrest). Over the three years between 2010−11 and 2012−13, AFP statistics show that officers attended 63 437 incidents and made 7864 apprehensions and 935 arrests at the 10 designated airports. The number of arrests made at the 10 designated airports increased by 42.6 per cent over the three year period from July 2010 to June 2013.20 Dealing with unattended items was the most common type of incident, accounting for almost 16 per cent of all incidents attended.

27. All Australian government agencies are required to have key performance indicators (KPIs) which are intended to allow an assessment of how the agency is delivering the outcomes required of it by government. The Aviation function has three KPIs covering the level of community and business confidence, the proportion of time spent in high-visibility policing and its ability to meet specified response times. Whilst the KPIs relating to community and business confidence and response times are relevant to the AFP’s role at airports, the KPIs do not, however, cover all key areas of the Aviation function (such as crime prevention). The AFP advised that it is conducting an AFP-wide Performance Framework Reform project. This project provides an opportunity for the AFP to consider the introduction of measures which better assess the Aviation function’s performance.

28. Measurement of the effectiveness of the AFP’s aviation function is inherently difficult.21 However, each year, the AFP conducts a survey of the Aviation function’s clients (the Business Satisfaction Survey (BSS)) and a survey of airport users (the Airport Consumer Confidence Survey (ACCS)).22 Both surveys show consistently high levels of satisfaction with the Aviation function. The 2013 BSS found that 96 per cent of respondents were satisfied (or very satisfied) with their most recent dealings with the Aviation function. Of the respondents to the ACCS, 86 per cent said that they were satisfied (or very satisfied) with the contribution that the Aviation function makes to aviation law enforcement.

29. Among the AFP’s stakeholders, two of the most important in relation to day to day operations are the airport operators and the state/territory police forces. The ANAO wrote to all 10 airport operators and to the seven state/territory police forces and met with representatives of airport operators and police forces in New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory. All seven state/territory police forces stated that they had good working relationships and did not identify any significant operational, jurisdictional, legislative or other impediments to effective policing at airports.

30. Representatives of the six airport operators who replied to the ANAO’s letter (or met with the audit team) reported that they had effective working relationships with the AFP. However, representatives of three operators (50 per cent) stated that they did not have a clear understanding of the Aviation function’s strategy for airport policing. In response to this feedback, the AFP has agreed to disseminate its Aviation Doctrine. Among other things, the Doctrine identifies types of criminal threats and critical points at airports and details a number of prevention, response and special operations that may be conducted.

31. During the period 2010−11 to 2012−13, a total of 140 complaints were reported as being made about AFP officers at airports.23 The number of complaints decreased by 37 per cent from 57 in 2010−11 to 36 in 2012−13. In 2012−13, a total of 69 ‘conduct issues’ were ‘established’ or substantiated. Although discourtesy accounted for seven of the established conduct issues, the largest single type of conduct issues was ‘fail to comply with direction or procedure’ (18 issues), where the ‘complainant’ was in fact another AFP officer. In 2012−13, the overall number of complaints and associated conduct issues arising at airports (36 and 62 respectively) compared favourably with ACT policing which had 229 complaints and 419 conduct issues in the same period.

32. The Commonwealth Ombudsman is empowered to conduct an annual inspection of the AFP’s complaint handling procedures, including whether the AFP has adequately investigated complaints it has received. In his most recent report to Parliament covering 2012−13, the Ombudsman concluded that, of the sample of 183 investigations across the AFP that he examined, with one exception, complaint investigations had been reasonably conducted and that the outcomes of complaints were also reasonable.

Summary of agency responses

33. The AFP provided the following summary comment to the audit report:

The AFP welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the ANAO Performance Audit, Policing at Australian International Airports and acknowledges the commentary provided within the report. The AFP agrees with the recommendation contained therein.

34. The AFP’s full response is included at Appendix 1.

35. The ANAO provided the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development with an extract of those parts of the report which were relevant to it. The department’s full response is also included at Appendix 1.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.62 |

To enable AFP officers to maintain appropriate knowledge of state and territory legislative requirements, the ANAO recommends that the AFP, in consultation with the relevant state and territory police force, reviews the content, duration and frequency of the legislative training courses. AFP Response: Agreed. |

Footnotes

[1] Connecting Australia: the economic and social contribution of Australia’s airports, Deloitte Access Economics, May 2012.

[2] The Secretary of the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development may designate an airport to be a security controlled airport which requires certain specified levels of security requirements. This may include screening and explosive trace detection.

[3] The ATSRs define counter terrorist first response as providing ‘deterrence measures designed to deny information to terrorists and deter acts of terrorism, and if an act is threatened or prospective, to deter or prevent it’.

[4] The Aviation function forms part of the National Security – Policing program.

[5] Appointees to uniformed components of the AFP are required to swear an oath (or make an affirmation) in terms prescribed by the AFP Regulations 1979 before they can exercise powers conferred on them by law.

[6] The role of PSOs is to keep individuals and interests identified by the Commonwealth as being at risk safe from acts of terrorism, violent protest and issues motivated violence. Their powers are more limited than those of sworn AFP officers.

[7] These officers were known as Airport Uniformed Police.

[8] The project’s objectives were (a) transitioning the Counter Terrorist First Response workforce from PSOs to sworn AFP members to provide a highly responsive, capable and homogeneous Aviation workforce and (b) transitioning from a hybrid Commonwealth/State and Territory model of Airport Uniformed Police (AUP) officers to a sworn AFP member workforce.

[9] A further 115 PSOs were redeployed to elsewhere in the AFP and 100 PSOs retired, resigned or accepted voluntary redundancy.

[10] The AFP advised that while it was not aware of any specific reason for the increase in the number of arrests, it was possibly due to its change of focus from counter terrorist first response to the whole policing continuum.

[11] The stated intent of the Aviation Doctrine is ‘to clearly outline the processes by which the AFP Aviation function focuses on anticipating and preventing unlawful acts or interference to aviation safety as well as preventing and defeating crime involving elements of the air stream’.

[12] As noted, states and territories had committed to providing 328 seconded officers. However, the Beale review noted that in practice, ‘some States have been unwilling or unable to provide agreed policing numbers’.

[13] Project Guild was used to manage the transition of protective service officers who were Air Security Officers (ASOs). ASOs are armed police officers who travel anonymously on selected domestic and international flights to provide security against any person or group who attempts to take control of an aircraft or to cause death or serious injuries to passengers or crew.

[14] Notwithstanding this reduction, the Aviation function has consistently met its targets for its Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) (see paragraph 4.21)

[15] Brisbane, Cairns, Canberra, Darwin, Gold Coast and Perth.

[16] Examples of the major risks to the airports include: reduced capacity to deliver CTFR and community policing functions, failure to deliver competent and qualified sworn members with the requisite knowledge, both Commonwealth and state and territory, to perform the policing at airport function and a failure to adequately deal with state-based offences.

[17] The relevant division in the Department of Industry and Regional Development is the Office of Transport Security.

[18] For example, Perth airport has four terminals some distance apart. The staffing required to respond to incidents at any or all of the terminals is commensurately greater than for an airport with fewer terminals.

[19] JAIGs are located at all of the designated airports: JAITs are located at Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney airports.

[20] The AFP advised that while it was not aware of any specific reason for the increase in the number of arrests, it was possibly due to its change of focus from counter terrorist first response to the whole policing continuum.

[21] The Australian Institute of Criminology has commented that ‘…there neither exists nor can there exist a single measure of police performance. Rather, it is appropriate to select from a variety of measures those which focus upon that specific element of police activity one wishes to evaluate’. (Australian Institute of Criminology, Efficiency and Effectiveness in Australian Policing, Canberra, December 1988.) In the Australian Capital Territory, ACT Policing uses 33 Key Performance Indicators to report to the ACT Government on its performance. (See ANAO Audit Report No.13 2012–13, The Provision of Policing Services to the Australian Capital Territory.)

[22] The 2013 ACCS involved a face-to-face survey of almost 2 000 domestic and international travelers. Less than 0.5 per cent of respondents refused to participate. The 2013 BCS involved a survey by email of 261 people who had had dealings with the Aviation function. The response rate was 49.4 per cent.

[23] Complaints received are categorised into four categories with Category One being the least serious and Category Four being allegation of corruption. Category One and Two complaints are referred to a Complaint Management Team in the functional area for investigation and reporting back to the central Professional Standards unit. Category Three complaints are investigated by the Professional Standards unit and Category Four complaints are referred to the Australian Commissioner for Law Enforcement Integrity. A complaint may raise more than one issue: the 140 complaints made in the period 2010–11 to 2012–13 included 263 ‘conduct issues’.