Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Operational Efficiency of the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to examine the efficiency of the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The role of the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) is to support the Integrity Commissioner to provide independent assurance to the Australian Government about the integrity of prescribed law enforcement agencies and their staff. The office of the Integrity Commissioner, and ACLEI, are established by the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006 (LEIC Act).

2. ACLEI’s stated purpose is to make it more difficult for corruption in law enforcement agencies to occur or to remain undetected.1 ACLEI undertakes a range of detection, investigation and prevention activities to deliver on its purpose and fulfil requirements under the LEIC Act.

3. Since its establishment in 2006, ACLEI’s jurisdiction and resources have expanded considerably. There are currently five prescribed law enforcement agencies within the jurisdiction of the Integrity Commissioner. In 2016–17 ACLEI’s total funding from government was $10.8 million and ACLEI’s average staffing level was 46.8.

4. A key requirement on the Integrity Commissioner, as the accountable authority of ACLEI under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, is to promote the proper management and use of public resources for which the Commissioner is responsible.2 This entails managing and using ACLEI’s resources efficiently as well as effectively, ethically and economically.

5. The Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity was established under the LEIC Act to oversight ACLEI.3

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. This topic was selected for audit as part of a series of performance audits focussing on the efficiency of entities. ACLEI plays an important role in the Australian Government’s law enforcement framework and has undergone various changes to its funding and jurisdiction over the past 10 years. ACLEI has not previously been the subject of an ANAO performance audit.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of this audit was to examine the efficiency of ACLEI in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Has ACLEI established appropriate arrangements to assess its efficient use of resources?

- How well does ACLEI’s efficiency compare with comparable entities and its own previous performance?

8. The audit objective and scope does not include assessing ACLEI’s operational effectiveness and no conclusions are made on this issue. The audit also did not seek to form a conclusion on the adequacy of ACLEI’s resourcing.

Conclusion

9. As ACLEI has not measured, benchmarked or reported on its efficiency in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct the ANAO has not been able to conclude whether ACLEI has been operating efficiently. The ANAO’s analysis and work that is underway within ACLEI indicates that improving case management and prioritisation practices is key to improving ACLEI’s operational efficiency as well as aligning its resource allocation with the legislative obligation to focus on serious and systemic corruption.

10. ACLEI has not established appropriate arrangements to enable an assessment of its operational efficiency to support the risk-based prioritisation of resources. While ACLEI measures the timeliness of assessments completed, a wider focus on the final outputs to be produced from its operational activities would provide a more robust indicator of performance.

11. ACLEI does not assess its operational efficiency against its own past performance or other organisations. The ANAO’s analysis indicates that the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities requires particular improvement, including to address growth in the number of investigations commenced compared to the number of investigations completed.

Supporting findings

Measuring and supporting operational efficiency

12. ACLEI has not established appropriate performance measures to inform itself, the Parliament and stakeholders (including law enforcement agencies) of how efficient its activities are in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct.

13. ACLEI has implemented systems and processes to capture some input and output data which can be used to calculate basic measures of its efficiency, including proxy measures. There is scope for ACLEI to improve its data collection and analysis to support a wider range of efficiency indicators.

14. ACLEI’s case selection and prioritisation decisions have not fully supported the efficient use of resources. Case selection decisions have resulted in significant growth in investigations commenced, but prioritisation of cases and resources have not led to a commensurate increase in the number of investigations being concluded.

15. ACLEI has implemented and sought to extend information sharing and shared services arrangements to support the efficiency of its operations. The impact of these arrangements is not clear due to a lack of relevant performance information.

Comparing operational efficiency

16. ACLEI does not measure changes in the efficiency of its detection, investigation and prevention activities over time. The ANAO’s analysis indicates that the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities may have deteriorated over time, while the timeliness of its assessment process has improved. When investigations have been concluded and resulted in the preparation of a brief of evidence, a high proportion of briefs have been accepted by the prosecuting authority with convictions then secured in the significant majority of cases.

17. ACLEI has not benchmarked its operational efficiency against other organisations, including State-based anti-corruption agencies. The ANAO’s analysis of ACLEI’s operational efficiency against four anti-corruption agencies in Australia indicated that the efficiency of assessments completed by ACLEI has improved and is comparable to other agencies, while ACLEI is relatively less efficient in concluding investigations.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.21

ACLEI develop performance measures focussed on the efficiency of its operations and collect additional data to report on its performance against those measures.

ACLEI’s response: Agreed with qualifications.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.41

ACLEI investigate whether it could introduce a more structured review process to support the prioritisation of available resources on a risk basis to the highest value investigations, including time or milestone based intervals to trigger decisions on the ongoing allocation of resources.

ACLEI’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.38

ACLEI periodically compare and benchmark its operational efficiency against comparable organisations including other anti-corruption bodies, and with its own performance over time, to determine whether changes to its current processes are required.

ACLEI’s response: Agreed.

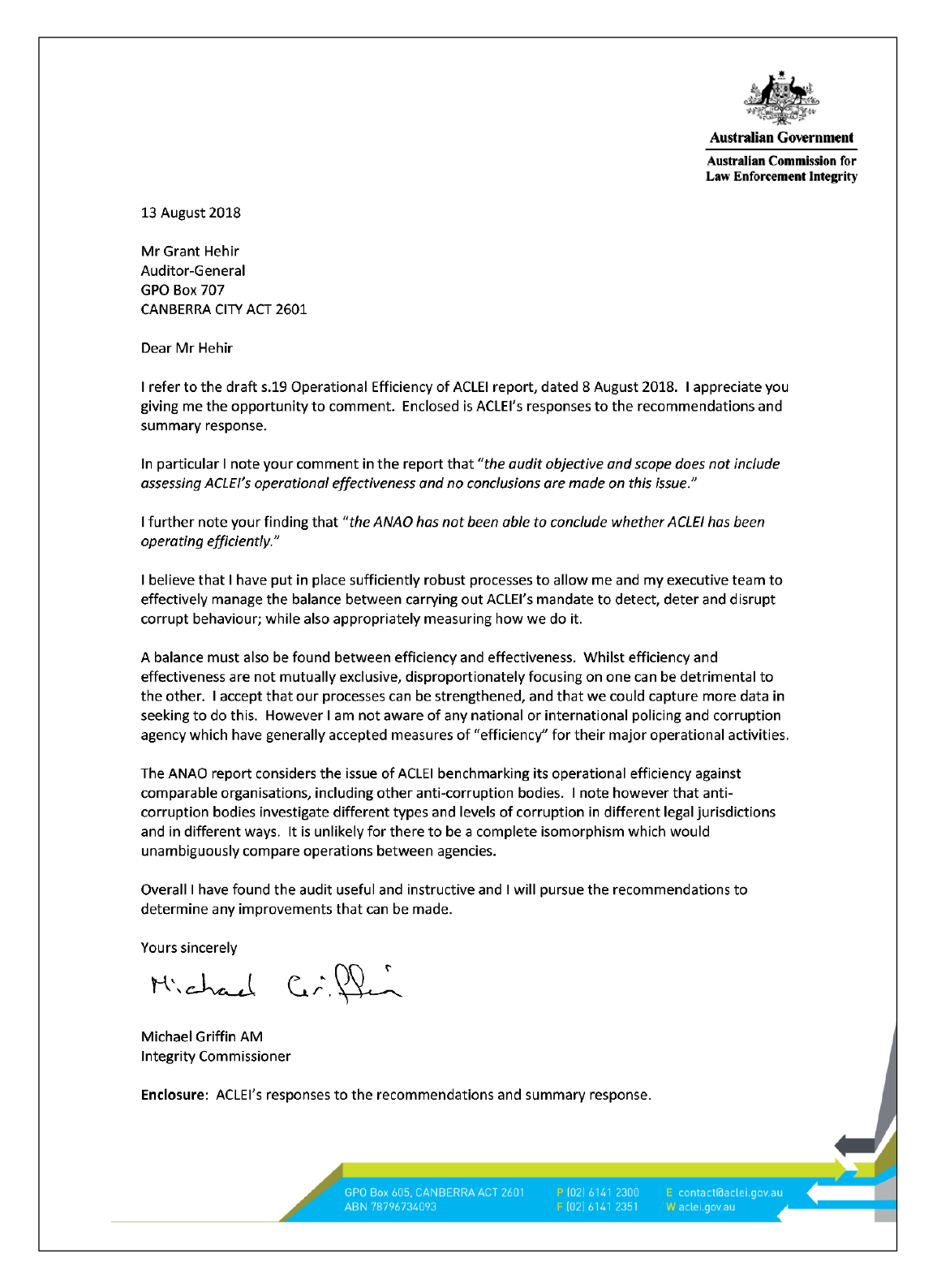

Summary of entity responses

18. ACLEI’s summary response is reproduced below. ACLEI’s full response is provided at Appendix 1. The four State agencies whose data was used as part of the benchmarking analysis for this audit elected not to provide a formal response.

Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

The Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity notes the results and thanks the Australian National Audit Office for the opportunity to respond.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Commonwealth entities.

Measuring and comparing efficiency

1. Background

ACLEI’s role, operating context and key activities

1.1 The role of the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) is to support the Integrity Commissioner to provide independent assurance to the Australian Government about the integrity of prescribed law enforcement agencies and their staff. The office of the Integrity Commissioner, and ACLEI, are established by the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006 (LEIC Act). The objects of the LEIC Act are to:

- facilitate the detection of corrupt conduct in law enforcement agencies and the investigation of corruption issues that relate to law enforcement agencies;

- enable criminal offences to be prosecuted, and civil penalty proceedings to be brought, following those investigations;

- prevent corrupt conduct in law enforcement agencies; and

- maintain and improve the integrity of staff members of law enforcement agencies.4

1.2 These objectives are reflected in ACLEI’s stated purpose in its Corporate Plan: to make it more difficult for corruption in law enforcement agencies to occur or to remain undetected.5

1.3 A key requirement on the Integrity Commissioner, as the accountable authority of ACLEI under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, is to promote the proper management and use of public resources for which the Commissioner is responsible.6 This entails managing and using ACLEI’s resources efficiently as well as effectively, ethically and economically.

1.4 The efficient management and use of resources supports entities to: maximise outcomes to government and the community; reduce the demands on the Australian Government Budget; and promote financial sustainability. For ACLEI, arrangements to enable the efficient and risk-based allocation of resources also align with the requirement in the LEIC Act for the Integrity Commissioner to give priority to serious and systemic corruption.7

1.5 The Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity was established under the LEIC Act to oversight ACLEI.8 The Committee’s responsibilities include monitoring and reviewing the performance of the Integrity Commissioner’s functions and examining each Annual Report and any special reports produced by the Commissioner.

Operational context

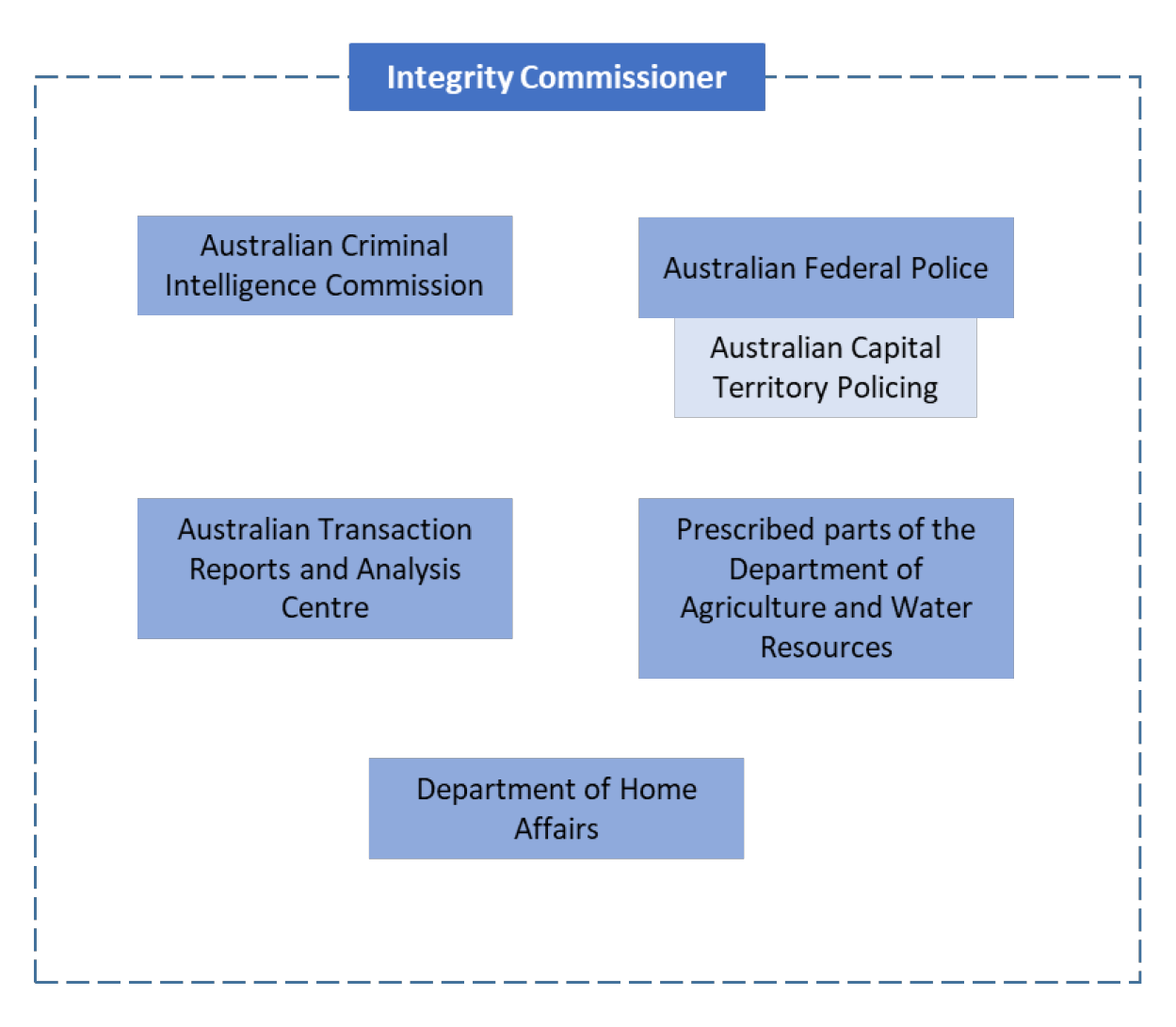

1.6 Since its establishment in 2006, ACLEI’s jurisdiction and resources have expanded considerably. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, there are currently five prescribed law enforcement agencies within the jurisdiction of the Integrity Commissioner. In addition, in the course of this audit ACLEI advised the ANAO that the complexity of investigations and sophistication of corrupt officers has increased.

Figure 1.1: Prescribed law enforcement entities within the jurisdiction of the Integrity Commissioner, April 2018

Source: ANAO presentation of information provided by ACLEI.

1.7 In 2016–17 ACLEI’s total funding from government was $10.8 million and ACLEI’s average staffing level (ASL) was 46.8. Although still a small entity, ACLEI’s annual funding and ASL have increased over the past 10 years (Figure 1.2). ACLEI’s organisational structure is comprised of an Operations branch focussed on activities to detect, investigate and prevent corrupt conduct, and a Secretariat branch which manages governance, corporate capability and policy advice to the Integrity Commissioner. Within the Operations branch, the majority of staff undertake investigations, intelligence gathering and analysis, with other operational staff responsible for assessments, corruption prevention and operational support.

Figure 1.2: ACLEI’s annual funding and average staffing level

Note: ACLEI was exempted from the requirement to provide separate financial statements for the reporting period ended 30 June 2007.

Source: ANAO analysis of data from ACLEI’s Annual Reports covering the financial years 2006–07 to 2016–17 and human resources data.

Detection, investigation and prevention activities

1.8 ACLEI undertakes a range of detection, investigation and prevention activities to deliver on its purpose and fulfil requirements under the LEIC Act. The overarching processes undertaken by ACLEI in receiving and dealing with potential corruption matters under its jurisdiction are illustrated in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Overview of ACLEI’s processes for receiving and dealing with potential corruption issues

Source: ANAO presentation of information provided by ACLEI.

1.9 Under the LEIC Act, the Integrity Commissioner is not required to investigate all instances of corrupt conduct that are identified or brought to the Commissioner’s attention.9 Also, upon notifying the Integrity Commissioner of a significant corruption issue, prescribed law enforcement agencies must cease any investigation into the issue and may only recommence if the Integrity Commissioner refers the matter back to the agency.10 If the Integrity Commissioner chooses to investigate a significant corruption issue alone, the notifying agency cannot investigate further unless the matter has been referred to the agency by the Integrity Commissioner.11

1.10 The number of potential corruption matters received and dealt with by ACLEI or other relevant law enforcement entities varies from year to year. During 2016–17, there were 242 corruption issues being investigated by ACLEI, and 183 corruption issues being investigated by other LEIC Act agencies.

1.11 In relation to corruption prevention, ACLEI performs a range of activities including disseminating insights on vulnerabilities and risks and delivering presentations and submissions to forums and inquiries. These activities are undertaken on an ad hoc basis using insights identified from detection and investigation activities.

Audit rationale and approach

1.12 This topic was selected for audit as part of a series of performance audits focussing on the efficiency of entities. ACLEI plays an important role in the Australian Government’s law enforcement framework and has undergone various changes to its funding and jurisdiction over the past 10 years. ACLEI has not previously been the subject of an ANAO performance audit.

Objective, criteria and scope

1.13 The objective of this audit was to examine the efficiency of ACLEI in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Has ACLEI established appropriate arrangements to assess its efficient use of resources?

- How well does ACLEI’s efficiency compare with comparable entities and its own previous performance?

1.14 The scope of the audit included an examination of ACLEI’s key detection, investigation and prevention activities as well as the systems and processes supporting these activities. The audit did not examine operational decisions or cases in progress.

1.15 The audit objective and scope does not include assessing ACLEI’s operational effectiveness and no conclusions are made on this issue. The audit also did not seek to form a conclusion on the adequacy of ACLEI’s resourcing.

Methodology

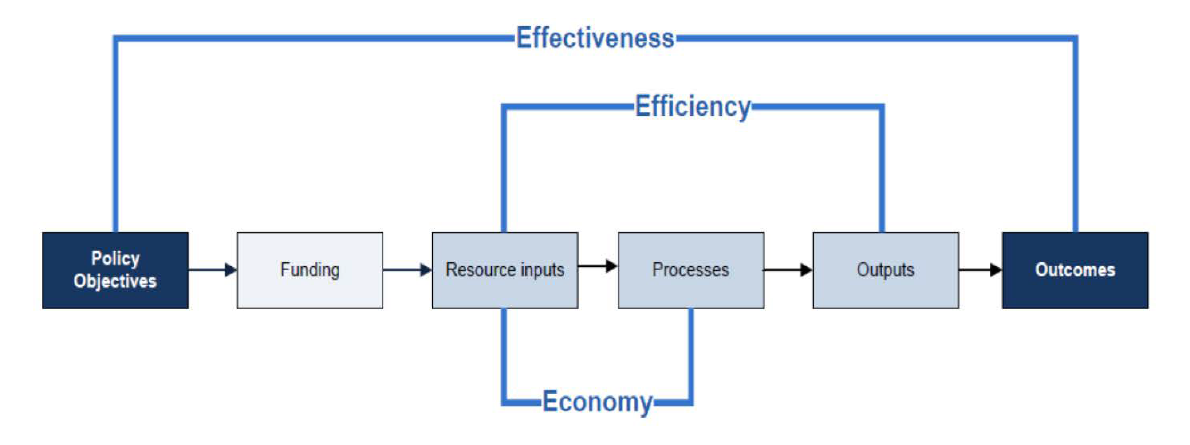

1.16 This audit applied the ANAO’s methodology for auditing efficiency12, which is based on a general model for assessing public sector performance (Figure 1.4). Efficiency is defined as ‘The performance principle relating to the minimisation of inputs employed to deliver the intended outputs in terms of quality, quantity and timing’.13

1.17 The methodology recognises that an examination of efficiency needs to be fit-for-purpose for each entity or subject matter being audited. In most cases, this is likely to include:

- identifying the relevant input and outputs, as well as the policy outcome(s) being sought;

- determining appropriate performance measures, drawing on data for inputs and outputs;

- identifying suitable comparators to benchmark against, to identify relative efficiency;

- identifying the key operational processes that are used to transform inputs into outputs (or outcomes) and the linkages between these elements; and

- undertaking appropriate audit procedures to understand and account for any material differences in the comparison of measured efficiency.

Figure 1.4: A general model for assessing public sector performance

Source: ANAO.

1.18 Specific audit procedures undertaken include:

- review and assessment of relevant operational procedures and performance data;

- interviews of management and key stakeholders to gain an understanding of ACLEI’s systems and processes;

- review of the arrangements for the prioritisation and allocation of resources;

- walk throughs of key processes within ACLEI’s detection, investigation, prevention and operations support functions;

- analysis of available data to understand ACLEI’s financial and operational performance;

- assessment of ACLEI’s Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and performance framework measures; and

- review and assessment of the models used to decide how to deal with corruption issues and prioritise investigations of corruption issues.

1.19 In addition, the ANAO benchmarked some of ACLEI’s operational activities against four Australian State anti-corruption entities — Victoria’s Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC), Western Australia’s Corruption and Crime Commission (CCC), New South Wales’ Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) and New South Wales’ Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC).

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $380 000.

1.21 The audit team was Stephen Cull, Brian Boyd and Callida Consulting.

2. Measuring and supporting operational efficiency

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether ACLEI has established appropriate arrangements to assess its efficient use of resources in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct.

Conclusion

ACLEI has not established appropriate arrangements to enable an assessment of its operational efficiency to support the risk-based prioritisation of resources. While ACLEI measures the timeliness of assessments completed, a wider focus on the final outputs to be produced from its operational activities would provide a more robust indicator of performance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations. The first is that ACLEI develop efficiency-focussed performance measures and collect appropriate data to report against these measures. The second is that ACLEI introduce a more structured review process to support the prioritisation of available resources on a risk basis to the highest value investigations, including time or milestone based intervals to trigger decisions on the ongoing allocation of resources.

Does ACLEI have appropriate performance measures to enable an assessment of its efficiency?

ACLEI has not established appropriate performance measures to inform itself, the Parliament and stakeholders (including law enforcement agencies) of how efficient its activities are in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct.

2.1 Since 1 July 2015 ACLEI has measured and reported on its performance through the use of five key performance indicators (KPIs), with each KPI supported by more detailed sub-criteria (Box 1).

|

Box 1: ACLEI’s key performance indicators |

|

Source: ACLEI 2017–18 Corporate Plan.

2.2 Only the second KPI explicitly considers the efficiency of an activity performed by ACLEI, the conduct of investigations. The performance information reported against KPI 2 does not provide a sufficient basis for assessing the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities. In ACLEI’s 2016–17 Annual Performance Statement, the number of investigations commenced, active and concluded over the past five years was reported against KPI 2. ACLEI did not detail the amount of time taken or resources used in conducting investigations or present qualitative analysis which explained how and why changes in the numbers of investigations commenced, active and concluded occurred. While some qualitative analysis is presented, details of time taken or resources used to conclude investigations are not regularly reported in internal performance information provided to the Integrity Commissioner or senior management.

2.3 ACLEI also reports statistics on the age and number of corruption issues carried forward each period, which remain under investigation. This data is relevant to understanding the efficiency of investigations, but it is not linked to any KPIs in the Annual Performance Statement and is not supported by qualitative analysis.

2.4 While KPI 1 is primarily focussed on effectiveness, ACLEI does present a measure of the efficiency of its assessment process under this KPI. The assessment process is used to determine whether corruption issues fall within the jurisdiction of the Integrity Commissioner and provide support and information to the Integrity Commissioner or delegate, about how to deal with such matters. The total number of assessments completed and the percentage completed within 90 days, against a target of 75 per cent is presented for the past five years. The ANAO has presented this data in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Percentage of assessments completed within 90 days

Source: ANAO analysis of data from ACLEI’s 2016–17 Annual Performance Statement.

2.5 Guidance material issued by the Department of Finance advises that targets should reflect the expectations of management, stakeholders and parliament and can be informed by performance from prior periods.14 ACLEI has reduced the average timeframe to complete assessments from 97 days in 2012–13, to 15 days during 2017–18. During 2017–18, 100 per cent of assessments have been completed within the target timeframe. In 2015–16, the Victorian Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) reduced its target timeframe for assessments from 60 to 45 days, to reflect changes in processes and performance since its establishment in 2012. ACLEI may benefit from reviewing its target to ensure it is aligned with the expectations of internal and external stakeholders, and baselined against recent performance. Also, as discussed further in Chapter 3, ACLEI should consider using a broader set of efficiency measures, which focus on the final outputs being pursued rather than the existing focus only on the timeliness of assessments.

2.6 ACLEI does not use efficiency measures to assess its performance against KPIs 3, 4 and 5. Some inherent challenges exist in applying efficiency measures to the activities examined by these KPIs, such as corruption prevention, governance and risk management. ACLEI describes initiatives delivered and reports the volume of some outputs produced to demonstrate performance against these KPIs. The initiatives and outputs reported are not linked to the volume of inputs used, the amount of time taken, or performance against a defined target, which would enable the efficiency of these activities to be assessed.

2.7 In August 2018, ACLEI advised the ANAO that it:

has sought the views of the international organisation McKinsey and Company, global management consultants, on how to undertake performance measurement and reporting. The advice was that measuring performance in policing and corruption agencies is problematic and that there is no accepted international or domestic standard performance measure.

Does ACLEI collect relevant and reliable information on its efficiency?

ACLEI has implemented systems and processes to capture some input and output data which can be used to calculate basic measures of its efficiency, including proxy measures. There is scope for ACLEI to improve its data collection and analysis to support a wider range of efficiency indicators.

2.8 An examination of efficiency is fundamentally about the relationship between inputs and outputs. For ACLEI, this has involved examination of the resources used to produce outputs through its activities to detect, investigate and prevent corruption. The availability of relevant and reliable entity data supports the measurement of efficiency. If more granular data is not available or is not cost-effective to obtain, proxy measures using aggregated data may be adequate.

2.9 The information systems used by ACLEI to collect key input and output data include:

- Financial Management Information System (FMIS);

- Case Management Information System (CMIS);

- Human Resource Management Information System (HRMIS); and

- Records Management System (RMS).

Collection of input data

2.10 ACLEI’s FMIS records details of all expenditure incurred and is a key source of input data. From 1 April 2017 cost centres aligned to ACLEI’s organisational structure were implemented within the FMIS. Expenditure which directly relates to the activities of a particular team is allocated to their relevant cost centre, while whole-of-agency overheads are recorded in a separate cost centre. A methodology to allocate overheads to teams or activities performed is yet to be implemented. At the time of audit fieldwork, arrangements for cost centre reporting were under development but had not yet been implemented.

2.11 The input data within the FMIS was sufficient to support examination of ACLEI’s operational efficiency at an aggregate level, using whole-of-agency costs. Costing data captured by ACLEI had not been disaggregated and allocated to detection, investigation and prevention activities. Similarly, total average staffing level (ASL) had been calculated by ACLEI using HRMIS data, but had not been disaggregated across teams or activities, meaning ASL can only be examined at the whole-of-agency level. As a result, the ANAO was unable to link the inputs used in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct with the outputs produced from these activities.

2.12 If the costs incurred by ACLEI in performing detection, investigation and prevention activities were broadly measured or estimated, input data for each activity could then be linked with the outputs produced to calculate proxy measures of efficiency. The benefits of increasing data collection would need to be considered against the related costs, including the cost of any system enhancements and redirection of staff resources.

2.13 ACLEI has recently commenced a project to develop a cost allocation model which will assist in estimating and monitoring the resource utilisation of investigations.

Collection of output data

2.14 ACLEI collects a range of data on outputs produced from its detection, investigation and prevention activities, some of which must be reported in its Annual Report.15 Table 2.1 below provides examples of output data collected by ACLEI.

Table 2.1: Examples of output data recorded by ACLEI

|

Activity |

Output data collected |

|

Detection |

|

|

Investigation |

|

|

Prevention |

|

Note a: Compiled by ACLEI in accordance with section 54 of the LEIC Act.

Note b: If the Integrity Commissioner decides to deal with a corruption issue by referring the corruption issue to a law enforcement agency for investigation, or managing or overseeing an investigation of the corruption issue by a law enforcement agency, the head of the agency must prepare a report after completion of the investigation in accordance with section 66 of the LEIC Act.

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI’s 2016–17 Annual Report and RMS data.

2.15 Information recorded in the CMIS allows the amount of time taken to complete individual assessments and investigations to be calculated. Similarly, the timeliness of preliminary investigations can be calculated using data collected by ACLEI in its RMS. The amount of time taken to perform these activities provides an indication of ACLEI’s efficiency.

2.16 Further data on the timeliness of ACLEI’s operational activities could be collected. Prior to concluding an investigation ACLEI may need to prepare a brief of evidence, wait for court proceedings to be finalised and prepare an investigation report. The start and completion dates of these milestones are not recorded in the CMIS. Systematically recording this milestone information would allow ACLEI to further analyse the timeliness of investigations and identify periods where ACLEI did not have control over the process. Additional date information could also be recorded for activities such as preparation of vulnerability briefs, preparation of information reports and reviews of section 66 reports from other agencies to enable their timeliness to be measured.

2.17 In preparing its 2015–16 Annual Performance Statement, ACLEI obtained feedback from jurisdictional agencies through a performance review commissioned by the Integrity Commissioner. The review identified timeliness of assessments as an area of concern amongst jurisdictional agencies. ACLEI has subsequently taken steps to address this and improved the timeliness of assessments (as discussed further in Chapter 3). The review provided an example of how stakeholder feedback can be collected to support an assessment of efficiency. There may be merit in ACLEI periodically collecting feedback from agencies within its jurisdiction to supplement its own internal performance information.

Reliability of information

2.18 ACLEI’s CMIS has suitable functionality for registering details of corruption issues dealt with by ACLEI. Limitations on the functionality of the CMIS present challenges for ACLEI in collecting and reporting performance information. Registration details of corruption issues recorded in the CMIS can be extracted only as raw data. Manual workarounds are required to produce the performance information and statistics included in the Annual Report, such as the percentage of assessments completed within 90 days.

2.19 The use of manual workarounds increases the risk that performance information produced and reported is not reliable. During 2016–17, ACLEI identified a number of errors in the performance data presented in its 2015–16 Annual Report after its publication. This information had been extracted from the CMIS and manipulated prior to being included.

2.20 Where information cannot be recorded in the CMIS, documents or spreadsheets are used and maintained in the RMS to record information such as the status of assessments, details of preliminary intelligence reviews conducted and vulnerability briefs prepared. Manual workarounds are also required to collate relevant performance information from the RMS, increasing the risk of errors.

Recommendation no.1

2.21 ACLEI develop performance measures focussed on the efficiency of its operations and collect additional data to report on its performance against those measures.

ACLEI’s response: Agreed with qualifications.

2.22 Developing efficiency measures which can be universally agreed in a law enforcement context will be challenging. ACLEI has been advised by the international organisation McKinsey and Company, global management consultants, that measuring performance in policing and corruption agencies is problematic and that there is no accepted international or domestic standard performance measure. However ACLEI will seek to gather additional performance data if this proves to be an effective and efficient use of our limited resources.

Do ACLEI’s arrangements for case selection and prioritisation support efficient use of resources?

ACLEI’s case selection and prioritisation decisions have not fully supported the efficient use of resources. Case selection decisions have resulted in significant growth in investigations commenced, but prioritisation of cases and resources have not led to a commensurate increase in the number of investigations being concluded.

2.23 Under the LEIC Act, the Integrity Commissioner must give priority to, but is not required to investigate all instances of, serious and systemic corruption. The Integrity Commissioner must have regard to several criteria in determining how to deal with corruption issues including the resources available to investigate a corruption issue. These requirements are reflected in ACLEI’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan which states: ‘operational resources are matched to the task and targeted for maximum public value’. ACLEI’s strategy involves considerations of both efficiency and effectiveness. Decisions on how to deal with corruption issues and prioritisation of investigations are key processes through which ACLEI’s operational resources are targeted, influencing its efficiency.

2.24 Figure 2.2 details the proportion of corruption issues notified and referred to the Integrity Commissioner which resulted in an investigation by ACLEI, either alone or as a joint investigation.

Figure 2.2: Proportion of corruption issues investigated by ACLEI

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Annual Report data for the financial years 2012–13 to 2016–17.

2.25 Figure 2.2 indicates that the proportion of notifications and referrals resulting in ACLEI investigations has grown over time. In 2016–17, 56 per cent of notifications and referrals progressed to an ACLEI investigation, compared to 31 per cent in 2015–16. In total, ACLEI commenced investigations into 107 corruption issues in 2016–17.

2.26 The size of ACLEI’s investigative workload has been subject to scrutiny in the past. In June 2015, the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (the Committee) noted with concern that there were 26 more corruption issues carried forward at 30 June 2014 than 30 June 2013. In response, the Integrity Commissioner stated that measures would be implemented to reduce the number of open corruption issues, including discontinuing investigations that were no longer warranted. Since 30 June 2014, the number of investigations carried forward increased from 118 to 336 as at 30 June 2017.

2.27 Figure 2.3 shows the number of investigations commenced and concluded by ACLEI from 2012–13 to 2016–17.

Figure 2.3: Number of ACLEI investigations commenced and concluded

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI 2016–17 Annual Performance Statement data.

2.28 Figure 2.3 demonstrates that over the five year period ACLEI has commenced more investigations than it has concluded, with ACLEI increasingly commencing more investigations than it has concluded. In 2016–17 ACLEI commenced investigations into 107 corruption issues but concluded only 14.

2.29 ACLEI acknowledges that case selection involves an opportunity cost as: ‘allocation of resources to one investigation means that they may not be available to another investigation’. The impact of such a rapid increase in the number of investigations undertaken has been a reduction in the amount of resources available per investigation.

2.30 A review of ACLEI’s staff profile conducted in 2014 stated that, at the time, ACLEI had capacity to undertake up to three substantial or complex investigations at any one time. Since 2014, the growth in numbers of investigations commenced has exceeded growth in ACLEI’s resources, impacting ACLEI’s capacity to thoroughly and promptly conclude investigations. In addition, in the course of this audit ACLEI advised the ANAO that the complexity of investigations and sophistication of corrupt officers has increased.

2.31 ACLEI has not documented the overarching framework used to manage individual investigations and ACLEI’s overall caseload of investigations. A draft framework was documented, but not finalised, with the most recent update made in November 2014. ACLEI has recently introduced updated investigation planning, debrief and risk assessment templates. The status of investigations is monitored weekly through reference to CMIS data, with further details manually added, including the relative priority of investigations (low, medium, or high). The limited reporting functionality of the CMIS presents challenges for ACLEI in monitoring the status of active investigations.

2.32 ACLEI’s arrangements for managing investigations do not incorporate any time or milestone based ‘gates’ where the decision to conduct an investigation must be periodically re-evaluated. If more investigations are commenced than ACLEI has the operational resources to complete there is a risk that some investigations may not be progressed. Given law enforcement agency heads cannot investigate corruption issues while they are subject to an ACLEI investigation, it is important that the resources allocated to ACLEI investigations are commensurate with the seriousness of the corruption issue under investigation.

2.33 Implementing a requirement whereby the decision to investigate a corruption issue must be re-evaluated after defined periods of time have elapsed, or as phases of investigative activity are completed, may assist in the identification of cases where investigation by ACLEI no longer represents the best use of ACLEI’s resources. In such cases, the Integrity Commissioner may decide to discontinue an investigation on the basis that it is no longer warranted in all the circumstances or refer the corruption issue to another law enforcement agency for investigation.

2.34 Where investigations have not progressed for lengthy periods, the ability of ACLEI, or other agencies to effectively and efficiently investigate a corruption issue may be reduced. ACLEI’s Notifications and Referrals – Guidelines on making decisions acknowledges that matters may no longer warrant investigation where significant time has elapsed as reliable evidence may not exist or be more difficult to obtain and the impact of corrective action may be reduced.

Improvements made by ACLEI

2.35 ACLEI commenced a review of its investigations workload in July 2017 to identify cases where investigation is no longer warranted given all the circumstances. In the ten months to 30 April 2018, the decision to conduct an ACLEI investigation was reconsidered for 29 corruption issues compared to 10 in all of 2016–17. The spike in the number of discontinued investigations suggests that ACLEI’s business as usual processes may not have been effective in identifying investigations which were no longer warranted in all of the circumstances or lower priority matters that could be concluded. ACLEI also closed one investigation via a report to the Minister and commenced investigation into an additional 45 corruption issues in the ten months to April 2018. Overall this represents a net increase to ACLEI’s investigative workload of 15 corruption issues.

2.36 As noted previously, ACLEI is developing a cost allocation model to provide an indication of the resource demands of individual investigations and ACLEI’s overall caseload. ACLEI has also recently implemented a Targeted Risk Assessment Matrix which is used to triage corruption issues which ACLEI is to investigate. These tools will provide estimates of the level of risk and complexity associated with corruption issues which can be considered by the Integrity Commissioner and ACLEI’s management in making decisions on case prioritisation.

2.37 From November 2016 ACLEI has introduced a preliminary intelligence review (PIR) process where additional intelligence gathering is performed to evaluate a corruption issue, rather than proceeding directly to an investigation. Similar arrangements are used by other anti-corruption agencies to reduce the level of uncertainty in allegations received. Seventeen PIRs covering 20 corruption issues have been completed to date, with the decision to investigate being reconsidered in ten instances.

2.38 Under section 17 of the LEIC Act, the Integrity Commissioner is able to enter into agreements with the head of law enforcement agencies which outline:

- issues in relation to agency staff which constitute significant corruption issues;

- the level of detail required to notify the Integrity Commissioner of a corruption issue;

- the way in which information in relation to a corruption issue can be communicated; and

- the level of detail required in final investigation reports from the agency.

2.39 A report to the Minister for Justice completed in September 2014 recommended that ACLEI make the maximum use possible of such agreements so that ACLEI’s involvement in corruption issues in those agencies is focused on serious or systemic corruption in law enforcement functions.

2.40 In May 2016 an agreement with the Australian Federal Police (AFP) was enacted, which allows the AFP to investigate less significant allegations of corrupt conduct, whilst notifying the Integrity Commissioner of the allegations. A similar agreement with the Department of Home Affairs was implemented as of March 2018. The section 17 agreements contribute to more efficient case handling by allowing the law enforcement agencies to continue investigations under specified circumstances, rather than suspending investigations until the Integrity Commissioner has made a decision.

Recommendation no.2

2.41 ACLEI investigate whether it could introduce a more structured review process to support the prioritisation of available resources on a risk basis to the highest value investigations, including time or milestone based intervals to trigger decisions on the ongoing allocation of resources.

ACLEI’s response: Agreed.

2.42 ACLEI will continue to implement and further investigate structured review processes which will assist in the prioritisation of available resources on a risk basis.

Do ACLEI’s information sharing and shared services arrangements support efficient operations?

ACLEI has implemented and sought to extend information sharing and shared services arrangements to support the efficiency of its operations. The impact of these arrangements is not clear due to a lack of relevant performance information.

Information sharing

2.43 In the course of its detection, investigation and prevention activities, there are numerous points where ACLEI seeks to obtain information from other entities. These activities involve significant intelligence gathering efforts by ACLEI staff where information is sought from sources external to ACLEI’s information holdings. Means used by ACLEI to obtain information include notifications and referrals, written requests for information, searches of external databases and verbal interviews or requests.

2.44 ACLEI shares and disseminates information with other agencies in the course of its detection, investigation and prevention activities in writing through briefs and reports and verbally through meetings, presentations and discussions.

2.45 ACLEI has included KPIs in its Corporate Plan which are relevant to its arrangements for sharing information with other agencies. These have been summarised in Box 2.

|

Box 2: Key performance indicators relevant to information sharing |

|

Criterion One – The corruption notification and referral system is effective 1.1 Law enforcement agencies notify ACLEI of corruption issues and related information in a timely way. 1.2 Other agencies or individuals provide information about corruption issues, risks and vulnerabilities to ACLEI. 1.3 Partner agencies indicate confidence in sharing information or intelligence with ACLEI. Criterion Three – ACLEI monitors corruption investigations conducted by law enforcement agencies 3.2 ACLEI liaises regularly with the agencies’ professional standards units about the progress of agency investigations. |

Source: ACLEI 2017–18 Corporate Plan.

2.46 In the 2016–17 Annual Performance Statement, the information presented by ACLEI against these KPIs does not enable the efficiency of information sharing to be assessed. Feedback from jurisdictional agencies was not obtained by ACLEI and data measuring the timeliness of notifications and communication with professional standards units was not collected.

2.47 Data which would enable measurement of the timeliness and efficiency of information sharing is not systematically recorded across ACLEI. Given the significant volume of information requests and differing approaches to obtaining and disseminating information, collecting data to measure the efficiency of ACLEI’s information sharing activities may not be cost-effective.

2.48 Gaining access to information held by entities outside of ACLEI’s jurisdiction can be complex due to legislation governing privacy, access and use of information, and compliance requirements imposed by record holders. Delays in obtaining information can impact the efficiency and effectiveness of operational activities.

2.49 ACLEI has sought to implement arrangements with other entities to improve information gathering by arranging access to external databases maintained by other law enforcement agencies and other information sharing mechanisms. These arrangements, especially those providing system and database access to ACLEI staff, have the potential to reduce the amount of time and resources used by ACLEI to obtain information from other entities.

2.50 Efficient information sharing assists in fostering confidence and trust between ACLEI and its jurisdictional agencies. A performance review undertaken in 2016 found that ACLEI’s jurisdictional agencies highly value timely communication from ACLEI on:

- the outcomes of its assessment of notifications; and

- insights identified through its operations, including vulnerabilities, emerging integrity risks, methodologies and assessments.

2.51 Since completion of the performance review, ACLEI has improved the timeliness of its assessment of notifications. ACLEI has also restructured its corruption prevention function to increase interaction and information sharing between prevention staff and other operational staff. ACLEI has indicated that this integration has resulted in more timely strategic intelligence reporting, both internally and externally, and the ability to increase targeted prevention activities. Suitable data has not been collected to measure and demonstrate the impact of these changes on the efficiency of prevention activities.

Shared services

2.52 As a small agency, ACLEI has obtained shared services since its inception in 2006 from external agencies and suppliers. Key shared services obtained by ACLEI include provision of:

- Surveillance capabilities — obtained predominantly from the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC);

- ICT related services — obtained from the Attorney-General’s Department; and

- Human resources and payroll related services — obtained from Aurion Corporation Pty Ltd.

2.53 Evidence was provided to demonstrate that value for money assessments had been performed by ACLEI prior to entering into these arrangements.

2.54 Figure 2.4 outlines the proportion of ACLEI’s total expenditure which was incurred in relation to surveillance capabilities, ICT related services and human resources and payroll related services over the past three years.

Figure 2.4: Shared services16 as a proportion of total expenditure

Source: ANAO analysis of data obtained from ACLEI’s FMIS.

2.55 From 2014–15 to 2016–17 these shared services have comprised a decreasing proportion of total expenditure.

2.56 Each of these services has been obtained under multi-year contractual arrangements which include fixed fee components. For surveillance capabilities, ACLEI has paid a fixed fee to ACIC of approximately $1.43 million for the past four years. Between 2014–15 and 2016–17, ACLEI’s utilisation of the capability increased meaning the services received by ACLEI were obtained at a lower cost per hour of surveillance.

2.57 On two occasions during 2017–18, ACIC’s surveillance capability was not available to ACLEI and surveillance services were purchased from a different agency, at additional cost. While this spending was in addition to the fixed fee to ACIC, ACLEI would not otherwise have been able to use surveillance capabilities in these instances. ACLEI is now seeking to implement arrangements with agencies in addition to ACIC to provide additional capacity and greater flexibility for its operations.

2.58 The size of ACLEI’s support and corporate services functions, as a proportion of total staff, has decreased over time. Headcount within ACLEI’s Secretariat (non-operational) division reduced from 51 per cent of ACLEI’s total staff in August 2014 to 38 per cent in June 2017. This was partly due to restructuring as part of ACLEI’s ‘operationalisation’ of certain roles. Over this same period headcount within Corporate Services decreased from 17 per cent of ACLEI’s total staff to 16 per cent.

2.59 The size of ACLEI’s corporate service function is comparable to that of other anti-corruption agencies. During 2016–17, corporate services staff comprised 19 per cent of the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption’s total staff. For the New South Wales Law Enforcement Conduct Commission, corporate services staff comprised 18 per cent of staff positions established as at 1 July 2017.

3. Comparing operational efficiency

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether ACLEI compares its operational efficiency with comparable organisations and with its own performance over time. The ANAO also compared aspects of ACLEI’s operational efficiency against four anti-corruption bodies in Australia.

Conclusion

ACLEI does not assess its operational efficiency against its own past performance or other organisations. The ANAO’s analysis indicates that the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities requires particular improvement, including to address growth in the number of investigations commenced compared to the number of investigations completed.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that ACLEI periodically compare and benchmark the efficiency of its operations against comparable organisations including other anti-corruption bodies, and with its own performance over time.

Has ACLEI become more efficient over time?

ACLEI does not measure changes in the efficiency of its detection, investigation and prevention activities over time. The ANAO’s analysis indicates that the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities may have deteriorated over time, while the timeliness of its assessment process has improved. When investigations have been concluded and have resulted in the preparation of a brief of evidence, a high proportion of briefs have been accepted by the prosecuting authority with convictions then secured in the significant majority of cases.

Identifying suitable comparators

3.1 Efficiency is generally relative to some standard, not absolute. Identifying suitable comparators is a key step in examining relative efficiency. Comparators may include: previous performance, which can indicate whether performance has improved over time; and performance against targets or benchmarks, which can indicate opportunities for improving operational processes and refining resource allocations.

3.2 As concluded in Chapter 2, ACLEI has not established suitable performance measures to enable an assessment of its efficiency across its operational activities. Consequently, with the exception of measuring and reporting on its performance against a target for the assessment process, ACLEI has not used any other targets or benchmarks to examine the relative efficiency of its resource use. Focussing on one indicator can impede a fuller understanding of efficiency across all relevant operational activities. ACLEI has also not compared its operational performance against relevant organisations, including other anti-corruption bodies.

3.3 In the absence of a broader range of efficiency measures being used by ACLEI, the ANAO has identified potential efficiency measures in relation to ACELI’s detection, investigation and prevention activities (Table 3.1), which can be calculated using available data on ACLEI’s performance. As discussed in the table, there are limitations with particular measures, and all measures are intended to be indicative rather than conclusive of performance. Using a set of measures such as these provides information which the Integrity Commissioner and senior management of ACLEI can consider when determining how to allocate and prioritise use of ACLEI’s available resources to deliver outcomes to government.

Table 3.1: Potential operational efficiency measures

|

Operational activity |

Operational efficiency measure |

Rationale |

|

Detection |

|

ACLEI has limited influence over the number of notifications and referrals received, and therefore the number of assessments it must complete. Examining the volume of assessments completed per staff member as well as the timeliness of assessments allows for greater insight into the efficiency of ACLEI’s arrangements. |

|

||

|

Investigation |

|

This measure provides an indication of how efficiently ACLEI uses its resources to conclude investigations. ACLEI’s total expenditure has been used as a proxy input as individual investigations are not costed by ACLEI. |

|

The timeliness of investigations concluded by ACLEI is an indicator of its efficiency. As this measure examines past performance it does not provide an indication of ACLEI’s efficiency in investigating its current caseload. Examining the age of open investigations is a lead indicator of the timeliness of investigations. |

|

|

||

|

This measure provides an indication of ACLEI’s efficiency and effectiveness in enabling offences to be prosecuted and civil proceedings to be brought. |

|

|

Prevention |

|

There is a lack of suitable input data and a significant degree of variability in the scale and nature of outputs produced from prevention activities. Therefore proxy efficiency measures utilising input and output data have not been calculated. Trends in the volume of outputs produced have been reviewed. |

Source: ANAO.

Detection activities

3.4 The majority of corruption issues dealt with by ACLEI are detected through the system of notifications and referrals established by the LEIC Act; therefore, the efficiency of ACLEI’s processes for evaluation and assessment of corruption issues are relevant to the efficient detection of corrupt conduct. In Figure 3.1 the average number of days to complete an assessment and the number of assessments completed per assessments team member17 have been compared.

Figure 3.1: Number of assessments completed per assessments team member and average number of days to complete assessments

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Case Management Information System data as at 30 April 2018 and Human Resources data.

3.5 Figure 3.1 indicates that the timeliness of assessments has been correlated with the volume of assessments completed per team member from 2013–14 to 2016–17. In the ten months to 30 April 2018, the volume of assessments completed per team member has decreased by 39 per cent, while the average number of days to complete an assessment has decreased by 70 per cent. This indicates an improvement in the efficiency of the assessments process.

3.6 For other detection activities performed by ACLEI, it is difficult to examine efficiency over time. ACLEI performs a range of intelligence gathering activities but often does not have visibility of the inputs used, outputs produced or the impact of these activities, limiting the extent to which performance can be measured. While ACLEI has sought to increase its detection capabilities through its own intelligence gathering, ACLEI has not collected performance information to enable the impact of this initiative to be measured.

3.7 Own-initiative investigations are an output from ACLEI’s detection activities which is measured but they represent a small fraction of total investigations. Four per cent of all investigations commenced in 2016–17 were own-initiative investigations, while across the five years from 2012–13 to 2016–17, they comprised five per cent of all investigations commenced. A lack of suitable performance information on detection activities has limited the extent to which their efficiency can be compared over time.

Investigation activities

3.8 As a measure of ACLEI’s efficiency in performing investigations, ACLEI’s average expenditure per concluded investigation has been calculated in Figure 3.2. The measure has been calculated as a three-year rolling average.18

Figure 3.2: Average expenditure incurred per concluded investigation

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Annual Performance Statement and Financial Statement data for the financial years 2010–11 to 2016–17.

3.9 Figure 3.2 indicates that the average expenditure incurred by ACLEI to conclude an investigation has increased over time. For the data examined by the ANAO, ACLEI has not categorised the relative complexity of the investigation. If the complexity of investigations remained constant over time, this would indicate a decrease in efficiency. ACLEI advised the ANAO that the complexity, sophistication and seriousness associated with corruption issues under investigation has increased over time and has been reflected in the increased use of powers under the LEIC Act by the Integrity Commissioner.

3.10 Figure 3.3 outlines the average duration19 of investigations concluded by ACLEI.

Figure 3.3: Average duration of concluded investigations

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Case Management Information System data.

3.11 Figure 3.3 indicates that the average duration of investigations concluded by ACLEI has varied over time. Examining the average duration of investigations does not provide a complete picture of the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities as the duration can only be calculated once an investigation has been concluded. The number of open investigations and the age of open investigations are also relevant to understanding the efficiency of ACLEI’s investigation activities.

3.12 Figure 3.4 shows the number of ACLEI investigations which remained open and were carried forward into the following financial year over the past five years.

Figure 3.4: Number of ACLEI investigations carried forward at year end

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Annual Report data for the financial years 2012–13 to 2016–17.

3.13 For the past five years, the number of corruption issues carried forward has increased. This has been driven by significant growth in the number of investigations commenced when compared to the number of investigations concluded.

3.14 In 2016–17, investigations into 14 corruption issues (5.8 per cent) were concluded out of a total of 242 that were open at the time. If no new investigations were to be commenced and this rate of completion continued, it would take a further 16 years for the remaining 228 investigations to be concluded.

3.15 Figure 3.5 shows the number of investigations at financial year end which had been open for more than 12 months.

Figure 3.5: Number of investigations aged greater than 12 months at year end

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Annual Report data for the financial years 2012–13 to 2016–17.

3.16 Figure 3.5 indicates that the ageing profile of ACLEI’s open investigations has deteriorated over time. It is important that ACLEI investigations are conducted and concluded in a timely manner to mitigate the risk of ongoing corrupt conduct (paragraph 1.9 explains the circumstances in which notifying agencies are unable to investigate the reported corruption issue).

Prosecutions and convictions

3.17 Briefs of evidence are a key output from ACLEI’s investigative activities which enable criminal offences to be prosecuted, and civil penalty proceedings to be brought. Where evidence of an offence or contravention of a law is obtained during an investigation, ACLEI must assemble the evidence and give it to a prosecuting authority.20 The proportion of briefs of evidence which are accepted by prosecuting authorities provides an indication of ACLEI’s effectiveness. ACLEI aims to achieve a high rate of acceptance on briefs of evidence submitted.

3.18 Given the resources allocated to prepare briefs of evidence, the rate of acceptance also indicates how efficiently these resources have been utilised. From 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2017, ACLEI prepared and submitted briefs of evidence in relation to 40 individuals. Of the 40 briefs of evidence submitted, a total of 39, or 98 per cent, were accepted by the prosecuting authority and subsequently pursued. Convictions were subsequently recorded in 3121 of the 39 matters that were put forward for prosecution by ACLEI.

Prevention activities

3.19 ACLEI performs a wide range of activities to prevent corrupt conduct, including:

- preparation and dissemination of intelligence reports and vulnerability briefs;

- review and analysis of investigation reports prepared by other agencies to identify corruption prevention insights;

- making recommendations to mitigate corruption risks and vulnerabilities as a result of ACLEI investigations;

- publication of educational guidance and other materials;

- submissions to parliamentary committees and inquiries;

- presentations and seminars delivered to jurisdictional agencies, and other entities; and

- attendance and involvement in anti-corruption forums.

3.20 In its Annual Performance Statements ACLEI reports outputs from its prevention activities over time. A summary of this output data has been provided in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Summary of outputs from ACLEI’s prevention activities

|

Prevention output |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|

Presentations to LEIC Act and other government agencies |

18 |

21 |

18 |

|

Presentations to audiences |

9 |

10 |

3 |

|

Public submissions to inquiries |

6 |

3 |

5 |

|

Agency reports reviewed |

51 |

14 |

62 |

|

Vulnerability briefs disseminateda |

NA |

NA |

6 |

Note a: Dissemination of vulnerability briefs commenced in November 2016, therefore figures are not available for years prior to 2016–17.

Source: ANAO analysis of ACLEI Annual Report data for the financial years ended 2014–15 to 2016–17 and RMS data.

3.21 Table 3.2 indicates that the level of outputs delivered from ACLEI’s prevention activities have remained relatively consistent over time, with vulnerability briefs being introduced as a new activity in 2016–17. The absence of timesheet or costing data for each output and prevention activities as a whole means that inputs cannot be linked to outputs delivered. Given the significant variability in the scale and nature of the activities performed, an increase in the number delivered may not represent increased efficiency. As such, the efficiency of ACLEI’s prevention activities cannot be adequately assessed using available data.

Is ACLEI efficient compared to other relevant organisations?

ACLEI has not benchmarked its operational efficiency against other organisations, including State-based anti-corruption agencies. The ANAO’s analysis of ACLEI’s operational efficiency against four anti-corruption agencies in Australia indicated that the efficiency of assessments completed by ACLEI has improved and is comparable to other agencies, while ACLEI is relatively less efficient in concluding investigations.

3.22 ACLEI does not benchmark its operational efficiency against other organisations, including State-based anti-corruption agencies.

3.23 In the absence of ACLEI taking steps to benchmark its efficiency, the ANAO sought to benchmark elements of ACLEI’s detection, investigation and prevention activities against four State anti-corruption agencies within Australia.

3.24 ACLEI has a unique role as the only agency solely dedicated to the detection, investigation and prevention of corrupt conduct within Commonwealth law enforcement agencies. Although there is no single entity within either Commonwealth or State Government that has identical responsibilities to ACLEI, there are several agencies within Australia that perform anti-corruption functions. The entities identified by the ANAO as suitable comparators to ACLEI given their role in detecting, investigating and preventing corrupt conduct are set out in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Entities identified as suitable comparators for ACLEI

|

Entity |

Purpose |

Jurisdiction |

|

Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC), Victoria |

To prevent and expose public sector corruption and police misconduct. |

Whole-of Victorian public sector, including Victoria Police. |

|

Corruption and Crime Commission (CCC), Western Australia |

To maintain and enhance the integrity of the Western Australian public sector, and to work with public authorities to reduce serious misconduct, including police misconduct. |

Whole-of Western Australian public sector, including Western Australian Police Force. |

|

Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), New South Wales |

To investigate and expose corrupt conduct in the NSW public sector, to actively prevent corruption through advice and assistance, and to educate the NSW community and public sector about corruption and its effects. |

Whole-of New South Wales public sector, local councils, members of Parliament, ministers, the judiciary and the governor. Does not extend to the NSW Police Force and NSW Crime Commission. |

|

Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC), New South Wales |

To detect, oversight, investigate and expose misconduct and maladministration within the NSW Police Force and the NSW Crime Commission. |

NSW Police Force and NSW Crime Commission. |

Source: IBAC, CCC, LECC and ICAC 2016–17 Annual Reports and websites.

3.25 To enable meaningful comparisons to be performed between the selected entities, data was obtained on the size of each entity’s annual funding, staffing and jurisdiction. For each entity, data relevant to the performance of detection, investigation and prevention activities was also obtained.

3.26 The Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC) in New South Wales is the agency most similar to ACLEI given its focus on law enforcement agencies. LECC was established following a review of law enforcement oversight in NSW and took on the functions formerly conducted by the Police Integrity Commission (PIC) from 1 July 2017.22 Historical performance data for LECC does not exist prior to this date. Given the transition being undertaken by PIC during 2016–17, its performance data has not been used for the purposes of benchmarking, as it does not represent a steady operational state and differences in performance could not be substantiated with PIC.

3.27 The benchmarking analysis undertaken incorporates measures of efficiency for performing assessments and investigations. Due to a lack of comparable data, the efficiency of detection activities, other than assessments, and prevention activities were not compared between agencies.

Assessments

3.28 Figure 3.6 indicates ACLEI has taken longer than other agencies to complete assessments in each of the three years examined. Although the nature and complexity of each allegation may vary considerably, the overall trend and size of the difference in time taken suggests that ACLEI was relatively less efficient over this period. It is noted that ACLEI has increased the efficiency of its assessments process during 2017–18 and reduced the average number of days to complete an assessment to approximately 15 days.

3.29 ACLEI has set a target of completing 75 per cent of assessments within 90 days or less, whereas the target timeframes set by comparators include:

- 28 days for ‘straightforward’ matters and 42 days for ‘complex’ matters set by ICAC;

- 28 days set by CCC; and

- 45 days set by IBAC.

3.30 There would be merit in ACLEI considering whether to apply additional targets of this kind to cover its processes for assessing potential corruption issues.

Figure 3.6: Average number of days to complete an assessment

Source: ANAO analysis of Annual Report data from each agency for the financial years 2014–15 to 2016–17 and ACLEI CMIS data as at 30 April 2018.

Investigations

3.31 Figure 3.7 indicates that, on average, ACLEI takes longer to conclude investigations than the comparator agencies. ICAC is ACLEI’s most suitable comparator against this measure, as both agencies’ investigations are solely focussed on corrupt conduct.23 From 2014–15 to 2016–17 ACLEI took an average of 478 days to conclude an investigation, while ICAC took an average of 461 days. While ACLEI’s average timeframe was comparable to that of ICAC during this period, in the ten months to 30 April 2018 the average number of days taken by ACLEI to conclude an investigation was 912 days. This timeframe is substantially longer than those recorded by ACLEI and each of the comparator agencies in the previous three years.

Figure 3.7: Average duration of concluded investigations

Source: ANAO analysis of Annual Report data from each agency for the financial years 2014–15 to 2016–17 and ACLEI CMIS data as at 30 April 2018.

3.32 The limitation of this measure is that the duration of an investigation can only be calculated once it has been concluded. It does not provide any indication of the number or age of open investigations. Accordingly, Figure 3.8 below shows the number of investigations concluded as a ratio of the number of investigations commenced for each agency over time. Figure 3.8 indicates that ACLEI’s ratio of concluded investigations to commenced investigations is much lower than that of the other agencies.

Figure 3.8: Number of investigations concluded as a ratio of investigations commenced

Source: ANAO analysis of Annual Report data from each agency for the financial years 2014–15 to 2016–17 and ACLEI CMIS data as at 30 April 2018.

3.33 Between 2014–15 and 2016–17, the comparator agencies concluded 120 investigations and commenced 126, a ratio of 0.95. In contrast, ACLEI concluded 31 investigations and commenced 225 (that is, ACLEI commenced more investigations than the other three agencies combined), a ratio of 0.14. Over this period, ACLEI commenced investigations at more than five times the rate that it concluded investigations.

3.34 The analysis suggests that ACLEI is less efficient in concluding investigations than the other agencies. In the ten months to 30 April 2018, ACLEI’s ratio increased to 0.67. While this is a substantial increase upon the ratio of the preceding three years, it nevertheless indicates that the number of open ACLEI investigations has continued to grow during 2017–18. For ACLEI to reduce the substantial number of corruption issues under investigation, a ratio of investigations concluded to investigations commenced above 1.0 must be achieved.

3.35 Given the requirement to give priority to serious and systemic corruption under the LEIC Act, ACLEI should ensure that its resources are appropriately targeted to maximise their impact. ACLEI’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan acknowledges this as a key strategy to deliver its purpose. If ACLEI’s available resources continue to be spread over an ever increasing caseload, ACLEI’s ability to thoroughly and promptly investigate corruption issues will be reduced.

Prevention activities

3.36 The nature of prevention activities performed by ACLEI presents challenges for measuring efficiency over time. Due to a lack of suitable input data and significant variability in the outputs produced, the efficiency of ACLEI’s prevention activities over time has not been assessed.

3.37 Similar challenges exist in relation to measuring and comparing the efficiency of other anti-corruption agencies in performing prevention activities. The specific activities performed vary between agencies, the timeliness of outputs produced is often not measured and specific input costs are not linked with outputs produced. Therefore, the ANAO has not benchmarked the efficiency of ACLEI’s prevention activities against the efficiency of other anti-corruption agencies.

Recommendation no.3

3.38 ACLEI periodically compare and benchmark its operational efficiency against comparable organisations including other anti-corruption bodies, and with its own performance over time, to determine whether changes to its current processes are required.

ACLEI’s response: Agreed.

3.39 ACLEI will periodically compare and benchmark its operational efficiency against comparable organisations, and with its own performance over time. It is noted however, that other anti-corruption bodies investigate different types and levels of corruption in different legal jurisdictions and in different ways. It is unlikely for there to be a complete isomorphism which would unambiguously compare operations between agencies.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Entity response

Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

Footnotes

1 See ACLEI’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan at https://www.aclei.gov.au/corporate-plan-2017-18.

2 See sub-section 15(2) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

3 See section 213 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

4 See section 3 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

5 See ACLEI’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan at https://www.aclei.gov.au/corporate-plan-2017-18.

6 See sub-section 15(2) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

7 See section 16 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

8 See section 213 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

9 See Part 4, Division 2 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

10 See section 20 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

11 See paragraph 26(1)(a) and sub-section 20(2) of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

12 The methodology is part of the ANAO’s Audit Manual. It provides requirements and guidance on steps to be followed throughout the planning, fieldwork and reporting phase of a performance audit.

13 This definition is provided in the Standard on Assurance Engagements ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements issued by the Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. This Standard is applied by the ANAO in its performance audit work.

14 See page 29 of Department of Finance, Resource Management Guide No. 131: Developing good performance information, Commonwealth of Australia, April 2015.

15 See section 201 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006 and Part 4 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Regulations 2017.

16 Shared services in Figure 2.4 include surveillance capabilities, ICT related services, human resources and payroll related services.

17 The number of assessment team members has been identified from review of organisational charts provided by ACLEI for each of the five years. The figures used are based on headcount at a point-in-time, rather than average staffing level for each of the years.

18 The average expenditure incurred has been calculated using a rolling three year average (for example, the 2012–13 figure is calculated using data from 2010–11, 2011–12 and 2012–13). The average has been calculated as total funding during the three year period divided by total investigations closed within that period.

19 Using CMIS data, the duration of a concluded investigation has been calculated as the number of calendar days between the date upon which the Integrity Commissioner decided to commence an investigation into the corruption issue and the date of conclusion recorded in the CMIS. The date a corruption issue was concluded is either the date of a Report to the Minister, or the date of a decision to discontinue by the Integrity Commissioner.

20 See Part 10 of the Law Enforcement Integrity Commissioner Act 2006.

21 In a further three instances, charges were proven but convictions were not recorded against the defendants.

22 LECC also took on the functions of the Police Division of the New South Wales Ombudsman’s Office and the Office of the Inspector of the New South Wales Crime Commission.

23 The enabling legislation of ACLEI and ICAC do not use identical definitions of corrupt conduct. ‘Engages in corrupt conduct’ is defined in section 6 of the LEIC Act, while ‘corrupt conduct’ is defined in Part 3 of the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 (NSW).