Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA's management of the Australian Government's responsibilities under the NPARSD. In this respect the ANAO considered whether:

- planning processes enabled effective establishment of the remote service delivery model;

- implementation of the key elements of the remote service delivery model effectively addressed the quality and timing requirements of the NPARSD; and

- performance measurement systems were developed to enable the parties to the agreement to assess whether the NPARSD objectives are being met.

Summary

Introduction

1. The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (NPARSD) was entered into to establish a new model for delivering services in selected remote Indigenous locations. The model is based on a whole-of-government, place-based approach designed to both improve the range and standard of services delivered, and to improve community engagement and development in selected locations. It was intended that this new service delivery model will contribute to closing the gap in life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. While there is a large gap in life outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people generally, the level of disadvantage suffered in remote Indigenous communities is particularly significant.

2. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) identified that the lack of access to services, and the poor coordination of services and infrastructure in remote Indigenous communities, were key drivers of disadvantage, stating:

There is strong evidence that Indigenous people in remote communities experience significant levels of social and economic disadvantage due to lack of access to services. Historical approaches to service delivery for remote communities have resulted in a mixture of patchy service delivery, ad hoc and short-term programs, poor coordination, and confusion over roles and responsibilities. Complications have been exacerbated by Indigenous-specific programs being added in, often to replace missing mainstream services and/or without any relationship to community development priorities. This lack of collaborative [action] and inconsistent government policy on the funding and delivery of services has contributed to the disadvantage experienced by many communities.1

3. Both the Australian and state/territory government agencies fund the delivery of Indigenous-specific and mainstream government programs and services in remote communities. It is common for both levels of government to fund services in the same social sectors within a community, usually through contract arrangements with non-government organisations. In developing the remote service delivery model, governments recognised that better coordinated services alone would not address Indigenous disadvantage and that greater community engagement and governance was also required to complement improved services and infrastructure. Combining these two key elements: service and infrastructure delivery; and community engagement and governance, COAG developed the NPARSD to help address Indigenous disadvantage in 29 selected remote Indigenous communities. 2

The NPARSD

4. The NPARSD was signed in January 2009 and commits the Australian Government and the New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Northern Territory governments to implementing a new service delivery model aimed at contributing to the achievement of five objectives. These are to:

- improve the access of Indigenous families to a full range of suitable and culturally inclusive services;

- raise the standard and range of services delivered to Indigenous families to be broadly consistent with those provided to other Australians in similar sized and located communities;

- improve the level of governance and leadership within Indigenous communities and Indigenous community organisations;

- provide simpler access and better coordinated government services for Indigenous people in identified communities; and

- increase economic and social participation wherever possible, and promote personal responsibility, engagements and behaviours consistent with positive social norms.

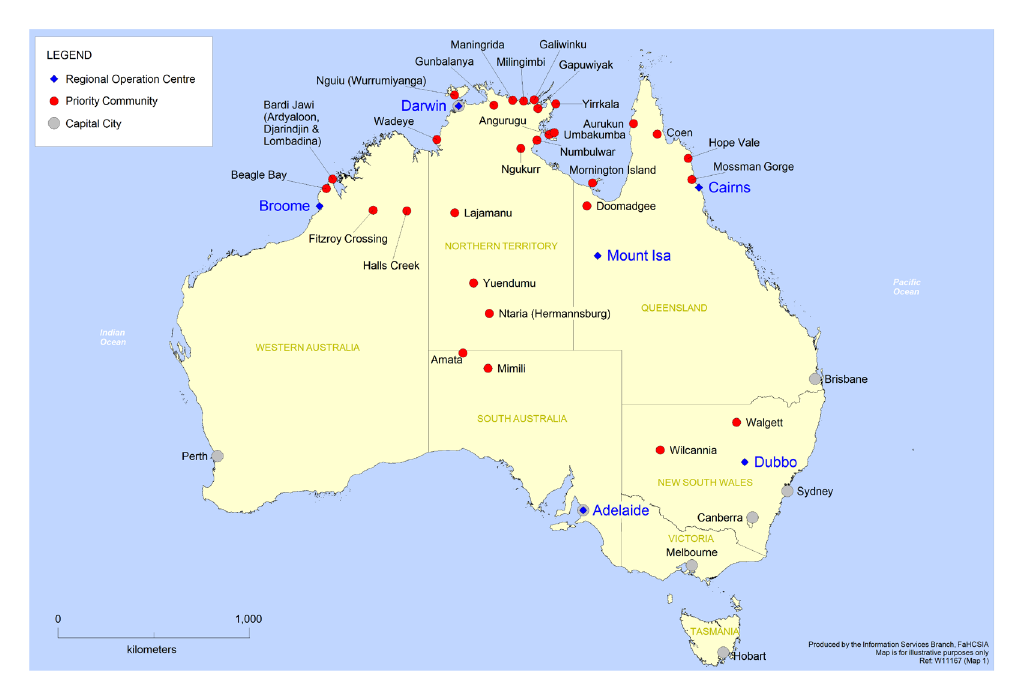

5. While not designated as a trial, the NPARSD focuses on implementing its remote service delivery model in 29 initial locations. The implementation of the remote service delivery model in the initial locations was to inform the ‘roll out’ of the measures to an additional ‘tranche of priority communities.’ 3 Initial locations were selected in consultation between the Australian Government and the relevant state/territory government. Priority locations are situated in New South Wales (two locations), Queensland (six locations), South Australia (two locations), Western Australia (four locations) and the Northern Territory (15 locations) and include a mix of discrete Indigenous communities and mainstream communities with large Indigenous populations. The 29 priority locations have a total population of approximately 28 000 people, with an Indigenous population of approximately 25 000. The Indigenous population of the 29 priority locations represents approximately 19 per cent of the remote Indigenous population and approximately 5 per cent of the total Indigenous population. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of priority locations across Australia.

Figure 1 Distribution of priority communities

Source: FaHCSIA.

6. The key elements of the NPARSD’s remote service delivery model include:

- bilateral plans between the Australian Government and each relevant state/territory which identify priority communities, milestones, performance benchmarks and indicators for services;

- baseline mapping of social and economic indicators, government investments, services and service gaps in each community;

- the establishment of a Single Government Interface to coordinate services and simplify community engagement with government representatives; and

- the development of Local Implementation Plans to identify the service delivery priorities agreed to by each community and governments.

7. The above elements are intended to work together as the basis for the remote service delivery model. The planned process for implementing the model commenced with the Australian Government agreeing a bilateral plan with each relevant state/territory. The bilateral plans were to outline how the objectives of the NPARSD would be achieved, identify locations involved and include milestones, performance benchmarks and indicators. Next, baseline mapping for the agreed locations was to be carried out to identify current government expenditure in each community, the current range of services and gaps in services. A key concept in the conduct of baseline mapping is the identification of a comparative non-Indigenous community, in order to establish a baseline for the standard and range of services to be delivered in a priority community.

8. The establishment of the Single Government Interface to guide engagement between communities and governments involved was a core element of the approach of the NPARSD. The Single Government Interface consists of six Regional Operations Centres, staffed by Australian and state/territory government officers, who support Government Business Managers (GBMs) and Indigenous Engagement Officers (IEOs), located in each of the 29 priority communities. GBMs are the key liaison for community members, representing the Australian and state/territory governments in the community. IEOs are Indigenous people recruited from within the local area to assist GBMs in their community engagement and liaison work.

9. In the initial stages of the NPARSD the main role of the Single Government Interface was to facilitate the negotiation of Local Implementation Plans based on the results of baseline mapping. Local Implementation Plans are an agreement between the various levels of government and community representatives and are intended to set out the services required, how they will be delivered and by whom. GBMs and IEOs are then responsible for coordinating the delivery of services committed by governments under the Local Implementation Plans. The delivery of NPARSD activities in communities is managed at a jurisdiction level by Boards of Management. Boards of Management are established in each participating state/territory and are comprised of senior representatives from Australian and state/territory government agencies responsible for the delivery of government services.

10. In addition to the elements directly related to the remote service delivery model, the NPARSD also includes a number of measures aimed at supporting community engagement and governance. Community support measures include:

- provision of cultural awareness training for all government employees involved with priority communities;

- programs to improve governance and leadership within communities;

- supply and use of interpreter and translator services, including the development of a national framework for the supply and use of Indigenous language interpreters and translators; and

- changes to land tenure to enable economic development.

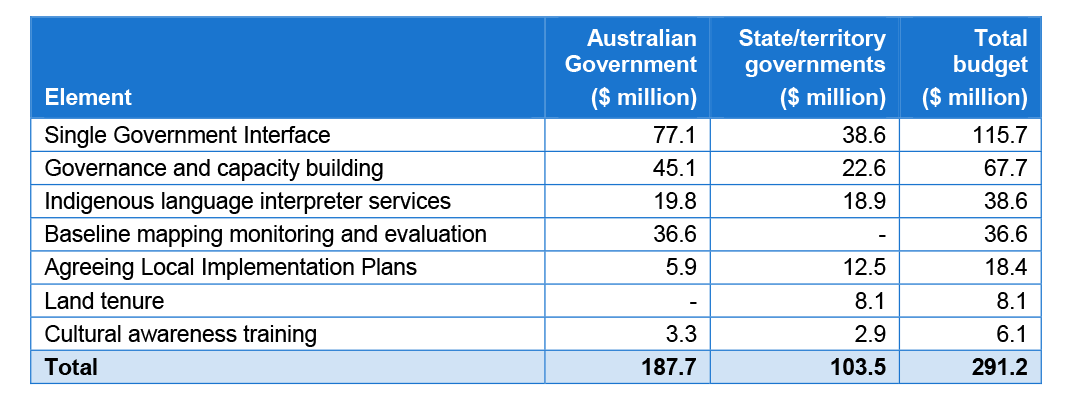

11. The NPARSD involves funding of $291.2 million over six financial years with the Australian Government contributing $187.7 million and the relevant states and the Northern Territory contributing a total of $103.5 million. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), as the lead Commonwealth agency, receives the full Australian Government contribution of $187.7 million, with most of the budget dedicated to the provision of the Single Government Interface, community governance capacity development, baseline mapping and interpreter services. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the budget for the NPARSD.

Table 1 Budget for the NPARSD

Source: ANAO, based on figures provided in the NPARSD.

Note: The Australian Government total, state/territory governments total, Indigenous language interpreter services total and cultural awareness training total vary due to rounding.

12. Most of the elements of the NPARSD are joint projects between the Australian Government and the respective states/territory. The key aspects that FaHCSIA is solely or jointly responsible for include:

- negotiating bilateral plans with the relevant states/territory (joint responsibility);

- undertaking baseline mapping (sole responsibility);

- establishing the Single Government Interface (joint responsibility);

- developing Local Implementation Plans (joint responsibility); and

- delivering community support measures (the Australian and state/territory governments both provide funding for these measures but deliver them separately).

Audit objective and criteria

13. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA’s management of the Australian Government’s responsibilities under the NPARSD. In this respect the ANAO considered whether:

- planning processes enabled effective establishment of the remote service delivery model;

- implementation of the key elements of the remote service delivery model effectively addressed the quality and timing requirements of the NPARSD; and

- performance measurement systems were developed to enable the parties to the agreement to assess whether the NPARSD objectives are being met.

Overall conclusion

14. Improving the delivery of government services has been identified by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) as a key priority in addressing Indigenous disadvantage. At the community level, the effectiveness of the delivery of services can be influenced by the extent to which different programs administered by different government agencies complement each other and support an integrated approach. Further, effective service delivery can also be influenced by the ability of governments and communities to collaborate in identifying needs and priorities. In establishing the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA), COAG emphasised the importance of governments ensuring that the services they deliver are coordinated effectively and that Indigenous communities are appropriately engaged by, and with, governments in the design and delivery of programs and services. The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (NPARSD) was developed and agreed by COAG to address the need for improved approaches to service delivery in remote Indigenous communities.

15. COAG agreed that the NPARSD’s approach to service delivery would ultimately contribute to the six targets for Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage established in the NIRA. More specifically, COAG agreed that the NPARSD would result in improved access to higher quality (and better coordinated) services and infrastructure, comparable with non-Indigenous communities. The NPARSD was also meant to contribute to improved governance and leadership within communities which would ensure community organisations met their legislative requirements and were accountable to their constituents and funding bodies.

16. The funding provided under the NPARSD does not in itself provide actual infrastructure or services to communities or individuals. Instead, the funding is for the establishment and staffing of administrative structures and supporting investments (community governance and leadership programs, cultural awareness training and interpreter services) which, taken together, are intended to better facilitate the delivery of infrastructure and services provided by government agencies through other programs.

17. The Australian Government has committed $187.7 million to implement the NPARSD initiative. Between 2008–09 and 2010–11, approximately $78.7 million has been spent by FaHCSIA against a budget of approximately $88 million for the same period. This funding has been used to establish a stronger government presence in the selected communities, overarching management arrangements and the mapping of services in communities.

18. Overall, FaHCSIA was effective in establishing a government presence in communities through the Single Government Interface and supporting administrative arrangements. This involved reaching agreement with each state/territory on joint staffing arrangements and contributions. The establishment of cross-jurisdictional governance arrangements through the establishment of Boards of Management in each participating state/territory was also effectively driven by FaHCSIA. As a result, a sizable government presence was established to service each of the 29 communities and arrangements to coordinate and set priorities at the jurisdictional level were also put in place. Baseline mapping, as a fundamental input to the development of Local Implementation Plans, was however not implemented in the timeframes envisaged by COAG. As a consequence, Local Implementation Plans were mostly negotiated utilising draft baseline information.

19. FaHCSIA has not developed structured arrangements to assess whether, as a result of the activities implemented through the NPARSD, government services have increased in number, are of a higher standard, or are better coordinated and simpler to access. Commitments made by governments in the Local Implementation Plans identified that more than half of all action items were ‘process’ related deliverables, whereas only a third were for ‘concrete deliverables’ related to the provision of new services and infrastructure. Other supporting measures that FaHCSIA was responsible for delivering, such as cultural awareness training, community governance and leadership development and the national interpreter framework, have not yet been implemented as COAG envisaged.

20. Measuring the contribution that the NPARSD was expected to make toward the Closing the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantage targets remains problematic. The NIRA established performance indicators for measuring progress against the Closing the Gap targets nationally. As part of the baseline mapping process, FaHCSIA developed a list of 81 social and economic indicators, some of which relate to the NIRA indicators. However, FaHCSIA advised that it is not possible to measure many of the NIRA indicators at the community level and has informed their Minister that even ‘significant gains across the 29 priority locations will not have any significant effect on the progress towards the [Closing the Gap] targets nationally.’ 4

21. The NPARSD was designed to make significant improvements in the way Indigenous people receive and participate in government services. Measuring changes in service delivery would be a relevant and practical way to assess the performance of the NPARSD. Accordingly, current performance measurement approaches could be improved by having a more explicit focus on whether services and access to services in each NPARSD priority community is improving as a result of NPARSD activities. More broadly, good implementation should seek to turn a program’s objectives into reality, which highlights the need for the objectives to be reasonable, considering timeframes and resources, and that planned outputs should have a clear and measurable impact on outcomes. As the NPARSD currently stands, the objectives and outcomes of the agreement will be challenging to meet, particularly those related to the comparable standards of services and infrastructure, improved community governance and leadership, and increased economic and social participation. In light of experience, any further expansion of the program would benefit from greater consideration of how these more aspirational objectives could be more directly addressed, or alternatively, whether there is a case for some revision to the program objectives.

22. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the monitoring of changes in service provision.

Key findings by chapter

Governance and coordination arrangements for cross-jurisdictional implementation

23. The NPARSD is a complex cross-jurisdictional undertaking requiring the development of clear structures and arrangements to support its implementation. This includes within FaHCSIA, across jurisdictional boundaries, and in the communities involved. FaHCSIA gave early attention to the establishment of program arrangements within communities to support the Single Government Interface. This involved establishing jointly staffed Regional Operations Centres, as well as recruiting and deploying staff into communities. To support coordination and decision-making with the states/territory, the establishment of joint Boards of Management was also an early priority.

24. Most responsibilities within the NPARSD have been classified as joint responsibilities, which emphasises the importance of developing a collaborative approach as FaHCSIA does not have explicit authority to direct other Australian and state/territory government agencies in their activities. Boards of Management and Regional Operations Centres are the key mechanisms for working through cross-jurisdictional issues and making decisions about priorities in jurisdictions. While there have been some difficulties in establishing these arrangements, overall they have been effectively established and FaHCSIA has developed solutions to address operational issues that have arisen.

Cross-jurisdictional and local level implementation planning and priority setting

25. The delivery of initiatives across multiple jurisdictions requires a high level of planning to effectively deliver on complex implementation commitments. While FaHCSIA gave early attention to implementing cross-jurisdictional arrangements such as the Single Governance Interface, it was slow to develop its own internal management arrangements. Initially, responsibility (and funding) for implementing the elements of the NPARSD was delegated to a range of functional areas in the department with limited oversight or coordination. It was almost a year after the commencement of the partnership that FaHCSIA created a dedicated branch focused on overseeing the delivery of the Australian Government’s responsibilities under the NPARSD. FaHCSIA did not finalise much of its program management documentation until November 2011, almost halfway through the initiative’s life span. The department has also experienced difficulty in readily compiling accurate financial data in relation to program expenditure. Timely implementation of core program elements is a relevant focus, however appropriate implementation guidance should ideally be established as quickly as possible to facilitate consistent implementation.

26. The development of bilateral plans, negotiated between the Australian Government and the individual states and the Northern Territory, was an important mechanism to formulate and agree priorities for action under the NPARSD. In agreeing the NPARSD, COAG established several requirements for the bilateral plans. The plans were required to identify the priority locations for RSD sites in each jurisdiction, identify proposed new expenditure by the states and the Northern Territory, include relevant performance information and be completed by April 2009. The plans were accepted by FaHCSIA and met the requirements of identifying priority locations, but no plan identified any new proposed expenditure. Generally, performance information was not well developed and all plans were finalised between four and eleven months after the original deadline.

27. Local Implementation Plans are a core element of the remote service delivery model proposed under the NPARSD. These were to be based on community needs and negotiated with communities. Local Implementation Plans were also developed as a way of prioritising and coordinating government activity in communities so as to reduce duplication and fill gaps in service delivery, and in this respect were to identify priorities, targets, resources and timeframes for the delivery of agreed action items. Action items can be commitments to provide services(for example, drivers’ licence training or specialist health services), infrastructure (for example, a child care centre or staff housing), or to undertake some kind of planning, research or review activity (for example, a community safety plan or a feasibility study into establishing a birthing centre). Action items can also relate to commitments made by the relevant community, such as encouraging children to attend school.

28. As at March 2012, 24 out of 29 Local Implementation Plans had been agreed and various consultation structures had been developed in different jurisdictions. Local Implementation Plans are being used to identify services being provided, or committed to, by government agencies at both the Australian Government and state/territory government level, but the plans generally contain limited details on timing and funding for implementing the action items. In total, over 3800 action items have been identified across all plans, many of which are similar across communities within jurisdictions. More than half (51 per cent) of all action items were focused on processes such as developing plans or testing the viability of services. Commitments to provide ‘concrete deliverables’, such as new services or infrastructure, made up 31 per cent of action items. Stakeholders generally attributed the lower number of service and infrastructure action items to tight budgetary conditions. Given the fact that fewer new services were committed to in Local Implementation Plans than originally intended, achieving the NPARSD’s objective of contributing to increasing the range of services delivered to Indigenous families will be difficult under the current timeframes of the NPARSD.

Developing service delivery in communities

29. Delivering the remote service delivery model required the implementation of a series of elements within a set of interrelated timeframes. Central to the concept of improving the service delivery model in remote communities was the need to develop a clear evidence base identifying existing services and service gaps in each community. Under the sequential model proposed by the NPARSD, the level of existing services in any given community would be compared to an identified comparator community and governments would negotiate with communities to identify service improvement priorities, having regard to the baseline mapping and the level of services available in comparator communities. In this respect, the robustness of the Local Implementation Plans was dependent on the prior completion of baseline mapping and the identification of appropriate service standards and existing expenditure.

30. Baseline mapping took longer than expected and while it generated a significant level of information about services in each of the priority communities, the baseline mapping reports did not provide the level of detail needed to fully compare the standard and range of services between priority and comparison communities, except in the case of municipal services. Although the Australian and relevant state/territory governments agreed to the design of the NPARSD, including the benchmarking of services and infrastructure against comparable non-Indigenous communities, FaHCSIA advised that the states/territory governments later raised concerns about utilising comparisons with non-Indigenous communities as the primary means of identifying service issues in priority communities. Accordingly, more limited attention was given to this aspect of baseline mapping. Having invested time and resources into the development of the baseline mapping reports, it is important that the information collected is used as a baseline to assess any future improvements in service delivery.

Performance assessment and reporting

31. As a result of the implementation of the NPARSD, access to a full range of suitable services was to be achieved, and further, these services were to be broadly consistent with services provided for other Australians in similarly sized and located communities. At an overall level, COAG identified that as a result of these improved services, the NPARSD would, along with other initiatives that supported the NIRA, contribute to Closing the Gap in Indigenous disadvantage. FaHCSIA has monitored the delivery of the partnership’s outputs and reported to COAG on these. FaHCSIA has also developed an online tool to monitor progress in delivering on action items identified in Local Implementation Plans. Difficulties in identifying service standards and comparator communities, and measuring change at the community level have left FaHCSIA with limited opportunity to objectively measure the changes effected as a result of the implementation of the remote service delivery model.

32. The current annual cost of providing the NPARSD initiative is approximately $2.1 million per community, with the provision of the Single Government Interface making the largest proportion of that expense. While limited quantitative assessment can be made of progress towards the partnership’s objectives and outcomes, FaHCSIA has made use of qualitative information collected within communities and advises that communities are observing positive changes in engagement with government as a result of the NPARSD.

Summary of agency response

33. A summary of FaHCSIA’s response to the report, dated 31 May 2012, is as follows.

I am pleased that the report acknowledges the work that has been done to date to establish and implement the NPARSD across government. The NPARSD is an important initiative that is working to improve and streamline government services delivery in 29 remote locations around Australia.

FaHCSIA accepts the recommendation made in the report and will work to implement the recommendation as quickly as possible. I do acknowledge however, that to fully implement the recommendation will require the partnership of other Commonwealth agencies as well as that of the State and Northern Territory Governments.

I would like to acknowledge the professional and thorough nature in which officers from the ANAO conducted the audit of the RSDNPA. I look forward to advising you of our progress against the recommendation in due course.

Footnotes

[1] COAG Fact Sheet: Remote Service Delivery National Partnership Agreement, p.4.

[2] The selected communities, known as ‘priority locations’ or ‘priority communities’ are generally a single community, however in some instances the priority location encompasses a primary community and the smaller communities or outstations close by.

[3] Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, The Hon Jenny Macklin MP, John Curtin Institute of Public Policy address, Perth, 21 April 2009.

[4] FaHCSIA brief, 19 August 2011, Remote Service Delivery Implementation Mini Stock-take August 2011.