Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

myGov Digital Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Human Services’ implementation of myGov as at November 2016.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The myGov digital service (myGov) is an entry portal for individuals to access the services of participating government entities. It was launched in May 2013 to provide individuals with secure online access to a range of Australian Government services in one place. It was expected to provide a whole-of-government digital service delivery capability and to improve the experience for individuals who choose to self-manage their interactions with government services. The four year myGov project (2012–13 to 2015–16) was to provide:

- a single username to access member services1;

- search ability to identify available government services;

- the ability to notify multiple services about changes of personal contact details;

- the ability to submit data online to validate facts, including for proof of identity; and

- lower costs and more timely communications from services via a digital mailbox.

2. The Digital Transformation Agency is responsible for myGov service strategy, policy and user experience.2 The Department of Human Services (Human Services) is responsible for administering and hosting myGov, including processes and procedures for system development and testing, security and operational performance.

3. By November 2016, myGov supported nearly 11 million active accounts and ten member services.3

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Human Services’ implementation of myGov as at November 2016. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- suitable governance arrangements were in place;

- myGov delivered a whole-of-government online service delivery capability;

- myGov improved service delivery for individuals;

- myGov provided an adequate level of performance, security and privacy; and

- myGov delivered value for money.

Conclusion

5. The Department of Human Services’ implementation of myGov as a platform to deliver whole-of-government online services has been largely effective.

6. Fit-for-purpose strategic and operational governance arrangements operated for the first three years of the myGov project, followed by a one year gap in strategic governance when interim arrangements had a largely operational focus. This gap was addressed in July 2016 with the

re-establishment of a strategic governance board.

7. There were 9.5 million user accounts registered in myGov by the end of the four year project—nearly double the business case forecast of 5.1 million. myGov has contributed to improved delivery of government services for individuals by providing three key functionalities—single digital credential, Update Your Details and Inbox—to reduce the time spent transacting with government. Several requirements to improve usability have only recently been implemented and a small number of requirements are yet to be delivered. As at November 2016, there were ten government services available through myGov. While it is not mandatory for member services to participate in myGov, the effectiveness of myGov as a whole-of-government capability has been hampered by government services not joining myGov and not fully adopting the myGov functionalities.

8. Since late 2015, the myGov platform has been hosted on high-availability infrastructure, which has improved performance, especially during peak demand periods, with performance targets consistently met. Suitable security and privacy measures were in place to control access and protect sensitive data stored in myGov.

9. In 2012, the Government approved a budget for the myGov project of $29.7 million for 2012–13 to 2015–16 based on the functionalities set out in the business case. The myGov project was not delivered within this original agreed funding, with actual expenditure to June 2016 totalling $86.7 million. Over the four years of the project an additional $37.8 million in funding was approved by Government, and Human Services funded the remaining $19.2 million from a pre-approved ICT contingency fund. Departmental records indicate that the increase in operating expenses over the four years of the project—from $8.5 million in 2012–13 to $37.3 million in 2015–16—was primarily driven by the costs associated with supporting the large number of user accounts (nearly double the forecast) and the improved high-availability infrastructure.

10. Performance metrics to enable the quantification of actual savings in the six areas identified in the business case were not developed. In the absence of such metrics, it is not possible to determine whether the expected savings have been realised in all six areas.

Supporting findings

Governance

11. Fit-for-purpose governance arrangements and sound planning processes were in place between 2012 and June 2015 to support the implementation of myGov. The governance framework had both a strategic and operational focus and featured: clearly defined roles and responsibilities; policies and processes that enabled consistent reporting on project implementation status, risks and issues, and performance; and arrangements to engage with government stakeholders.

12. In June 2015, these governance arrangements ceased and interim arrangements were established. The interim governance arrangements had a largely operational focus resulting in limited strategic oversight for myGov as a whole-of-government capability until July 2016. Revised governance arrangements were introduced in July 2016 which featured a new board to provide strategic direction and the retention of key operational committees.

Delivering expected outcomes

13. By June 2016, myGov had exceeded the expected uptake with over 9.5 million user accounts registered compared to the business case forecast of 5.1 million. myGov had almost 11 million accounts by November 2016.

14. Of the five functionalities expected to be delivered in myGov:

- Human Services delivered three key functionalities in myGov that enable individuals to: access government services online using a single digital credential; notify changes of personal contact details; and receive digital correspondence securely. A small number of requirements within these functionalities, which were considered mandatory for go-live, have not yet been implemented.

- The expected search functionality was partly delivered through an interim solution which enables individuals to perform structured searches of government services; however the expected free text searches envisaged by this functionality are not able to be performed in myGov.

- The data validation functionality was designed, but not delivered in myGov. Human Services advised the ANAO that this functionality was available via the Centrelink member service and that the use of this existing functionality was considered more efficient. As a consequence, a myGov user must link their account to Centrelink and access that service to use the data validation capability.

15. myGov was built using open standards, is scalable and is an authentication platform which can be integrated with member services. Centrelink, Medicare and the ATO member services are using all the available myGov functionalities, the adoption of which was expected to streamline business processes and improve the user experience. Three government services identified in the business case elected not to participate in myGov. Of the ten member services that decided to participate in myGov, six use some but not all of the available functionalities.

16. The myGov platform has provided a basis for improved service delivery, including a reduction in the time spent by individuals interacting with government. This benefit accrues where individuals use the myGov functionalities to receive correspondence or update their details, and in particular, where individuals link their account to at least two member services. Where individuals already had multiple online credentials, they incur a one-off time cost to join myGov. Individuals who do not have their account linked to multiple services do not receive the potential time saving benefits to the same extent.

Project implementation

17. In December 2015, Human Services introduced high-availability infrastructure to support the increased demand for myGov during peak periods. Since this time, Human Services has reported that myGov’s performance has met or exceeded the monthly availability target of 99.5 per cent.

18. Suitable security and privacy measures were adopted for myGov, leveraging existing Human Services arrangements to control access and protect data. In addition, myGov stored only limited sensitive personal data and did not facilitate data sharing between member services.

19. Human Services and participating entities captured feedback through surveys and usability testing to inform myGov’s roll-out. The feedback was used to correct faults and enhance myGov functionalities, but some resolutions were not delivered in a timely manner. From July 2016, the Digital Transformation Agency has had responsibility for the myGov user experience and, with Human Services, has developed and progressed a program of work based on a prioritised backlog list of fixes and enhancements.

20. A Closure Report has been prepared identifying lessons learned from the project, and two post-implementation reviews were conducted on specific aspects of the project as they were delivered. A post-implementation review for the project as a whole has not been completed.

Value for money

21. The total cost of the four year myGov project was $86.7 million. The Government:

- initially approved a budget of $29.7 million and authorised Human Services to fund any shortfall on the project from a pre-approved ICT contingency fund; and

- approved an additional $37.8 million in funding during the project.

22. Departmental records indicate that the increase in project expenditure was primarily the result of higher expenses associated with supporting the large number of user accounts—nearly double the forecast—and the improved high-availability infrastructure.

23. Six areas of savings for government, accruing to the member services, were identified in the business case. It is not possible to determine whether all the expected savings were realised as Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office did not define performance metrics to enable the quantification of actual savings. Human Services has calculated actual savings for one measure—avoided postage costs. The department estimated that the myGov Inbox saved government $109.2 million, a figure that may be overstated as there were existing email capabilities provided by member services although not with the same level of security as myGov’s Inbox.

Recommendations

Recommendation No.1

Paragraph 3.17

The ANAO recommends that the:

- Digital Transformation Agency implement a strategy to target ‘service delivery’ Australian Government entities to provide services through myGov; and

- Department of Human Services review existing transition support and guidance materials for entities to ensure that they effectively support targeted government entities to interface their systems with myGov functionalities.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation No.2

Paragraph 3.27

The ANAO recommends that the Digital Transformation Agency, in consultation with the member services, establish a performance framework, including key performance indicators focussing on outcomes, to enable an assessment of the extent to which myGov is delivering expected outcomes for users and member services.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entities’ responses

24. The Department of Human Services’, the Digital Transformation Agency’s and the Australian Taxation Office’s summary responses to the report are provided below, with the full responses at Appendix 1.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report, and considers that implementation of its recommendations as they relate to the department will enhance the department’s management and implementation of myGov.

We are pleased to note that the ANAO found that the department’s implementation of myGov as a platform to deliver whole-of-government services has been largely effective and has contributed to improved service delivery of government services for individuals. Currently, myGov has over 10 million active accounts and supports 10 member services compared to the original forecast of 5.1 million users and six member services.

Digital Transformation Agency

The DTA agrees with the ANAO’s proposed recommendations and will continue to work closely with the Department of Human Services and member services to expand myGov’s take-up among Australian Government services, and develop a performance framework for the service.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO welcomes this review into the effectiveness of the Department of Human Services’ implementation of myGov. Of the ten member services, the ATO has the highest number of clients using myGov. By the end of April 2017, six million ATO clients had linked their myGov account to their ATO client record. As a key stakeholder throughout the design and implementation of myGov, and as one of the primary users of the service, the ATO appreciates the opportunity to have provided input into the review.

The report recognises that the implementation of the myGov platform was largely effective, with higher than projected take-up of the service by the community but lower than projected take-up of the service by government agencies.

The ATO supports the finding that some features of the service are yet to be delivered and also supports the view that undelivered requirements should be considered as part of ongoing prioritisation and monitoring processes.

The report acknowledges the ATO’s successful implementation of each of the services introduced within the myGov platform. The ATO has successfully leveraged myGov services including the digital mailbox, the update your details service and the myGov profile. Additionally, the myGov credential is now used as an alternative to AUSkey for access to online government services for business through Manage ABN Connections; a joint initiative led by the ATO in collaboration with the Department of Human Services and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science. There are currently over 138,000 myGov accounts linked to one or more ABNs. Between June 2016 and May 2017, there have been more than 500,000 authentications to online government services for business with an ABN-connected myGov account.

The ATO supports the two recommendations outlined in the report and looks forward to working with the Digital Transformation Agency to develop a myGov performance framework as outlined in Recommendation Two.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 In the 2010 report, Ahead of the Game: Blueprint for Reform of Australian Government Administration, it was recommended that the Government simplify its service delivery and make access to government services more convenient for Australians through automation, integration and better information sharing.4

Business case

1.2 In 2011, the Department of Finance (Finance) commissioned the development of the Reliance Framework5 business case (the business case).6 The Reliance Framework was intended to encompass a set of policies, standards and infrastructure to enable more convenient access to government services while enhancing whole-of-government capabilities to deliver online services.

1.3 In August 2012, the Government agreed to the business case to improve individuals’ access to online government services through the development of a whole-of-government ICT architecture.7 The Department of Human Services (Human Services) was designated as the lead delivery entity, supported by six stakeholder entities: the Australian Taxation Office (ATO); the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations; the Australian Electoral Commission; the then Department of Immigration and Citizenship; the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA); and the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD).

1.4 To deliver on this whole-of-government reform, Human Services was expected to leverage its ICT capabilities as an extension of its existing Service Delivery Reform program. Human Services was also responsible for administering and hosting this new government digital service platform, including establishing relevant processes and procedures for development and testing, security, and operational performance.

1.5 In October 2012, the Reliance Framework platform was branded ‘myGov’.

1.6 Figure 1.1 illustrates myGov as the entry portal for individuals to access participating government services, referred to as member services.

Figure 1.1: Illustration of myGov as the portal to member services

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

Expected outcomes

1.7 myGov was expected to deliver two major outcomes as outlined in the business case (discussed further in Chapter 3):

- improved service delivery for individuals supported by five key functionalities—single digital credential, Update Your Details, Inbox, discoverability, and data validation; and

- improved whole-of-government online service delivery capability supported by a governance framework, standardised business processes, and common standards.8

Benefits

Savings for government

1.8 Six drivers of savings for government, accruing to the member services, were identified in the business case. Savings were primarily expected from a reduction in contacts by individuals through traditional channels, such as face-to-face contacts at government shopfronts and through telephone calls. Table 1.1 lists these savings drivers and estimated annual savings expected from 2015–16.

Table 1.1: Business case—expected annual savings for myGov member services from 2015–16

|

Areas of savings for member services |

Expected annual savings from 2015–16 |

|

$2.0 million |

|

$16.0 million |

|

$0.5 million

|

|

$0.5 million |

|

$1.6 million |

|

Savings not estimated |

|

Total expected annual savings from 2015–16 |

$20.6 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of the Reliance Framework business case.

1.9 Table 1.2 shows the expected annual savings during the four year project as presented in the business case. Savings for member services were expected to increase during the four year project and be fully realised in the fourth year of the project (that is, 2015–16). Savings totalling $47.6 million were expected over the four years (2012–13 to 2015–16). By 2015–16 a target of 5.1 million user accounts was expected to be reached, and six government entities were to have joined myGov. A constant level of annual savings, $20.6 million, were expected each year thereafter.

Table 1.2: Business case—expected savings for myGov member services by year

|

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Project Total |

|

Savings |

$0 |

$10.2 million |

$16.8 million |

$20.6 million |

$47.6 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of the Reliance Framework business case.

Additional benefits

1.10 myGov was expected to deliver additional benefits for member services and individuals that could not be quantified but which the business case identified should still be considered. Table 1.3 summarises these additional benefits.

Table 1.3: Additional benefits considered in the business case

|

Additional benefits |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of the Reliance Framework business case.

Funding

1.11 The 2012 business case estimated that the total cost to design, build and deploy myGov over the four years would be $35.9 million—comprising $16.4 million for capital costs and $19.5 million for operational costs.

1.12 Based on Human Services’ leveraging its existing ICT infrastructure and programs, the Government agreed to total funding for myGov of $29.7 million over the four year project (2012–13 to 2015–16), comprising $10.3 million for capital costs and $19.4 million for operating costs. Under this funding approach, Human Services would contribute $26.1 million and the six stakeholder entities9 would contribute a total of $3.6 million to support the delivery of myGov. The Government also agreed at that time that Human Services could access a departmental ICT contingency fund, available for its Service Delivery Reform Program, to provide the myGov project with funding flexibility.

1.13 Table 1.4 provides a summary of the original approved funding to implement myGov.

Table 1.4: myGov funding approved in 2012

|

myGov funding |

2012–13 $m |

2013–14 $m |

2014–15 $m |

2015–16 $m |

Total $m |

|

Capital cost funding |

5.1 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

1.1 |

10.3 |

|

Operating cost funding |

7.2 |

4.7 |

3.8 |

3.7 |

19.4 |

|

Total myGov funding |

12.3 |

6.9 |

5.7 |

4.8 |

29.7 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

Roles and responsibilities

1.14 In 2012, the Government agreed a multi-tiered governance structure. Table 1.5 summarises the roles, responsibilities and membership of the initial myGov governance arrangements (discussed further in Chapter 2).

Table 1.5: 2012 roles and responsibilities

|

Role |

Responsibilities |

Membership |

|

Lead Minister |

|

Minister for Human Services |

|

Secretaries’ ICT Governance Board (SIGB) |

|

Secretaries of the ICT Governance Boarda |

|

Reliance Framework Board |

|

Human Services (Chair)b Finance ATO AGD |

|

Reliance Framework Reference Group |

|

ATO (chair); AGD; Finance; Human Services; Prime Minister and Cabinet; Treasury; the then Department of Health & Ageing; the then Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs; the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations; the then Department of Broadband, Communication and the Digital Economy; Foreign Affairs and Trade; the then Department of Immigration and Citizenship; DVA; the then Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education; and the then Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. |

|

Working Group |

|

Human Services (internal membership) |

Note a: SIGB membership comprised: Finance (Chair); Department of Communications; Department of Defence; Department of Social Services; Human Services; the then Department of Immigration and Citizenship; Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet; Attorney-General’s Department (AGD); and National Archives of Australia.

Note b: From 2013 the membership of the Reliance Framework Board was extended to include: Department of Health; Department of Communications; and Department of Social Services.

Source: ANAO analysis of the Reliance Framework business case.

myGov launch and statistics

1.15 In May 2013, myGov was launched with 1.3 million user accounts—transitioned from australia.gov.au—and three Australian Government entities providing five member services.10

1.16 By June 2016, there were over 9.5 million user accounts11 and seven Australian Government entities providing nine member services through myGov.12 Three government entities identified in the business case did not join myGov.13

1.17 In August 2016, the first state government member service joined myGov,14 and five myGov shopfronts were operating in Brisbane, Sydney, Adelaide, Perth and Albury. By November 2016, myGov had almost 11 million user accounts.

1.18 From its launch to June 2016, myGov has supported:

- 160 000 daily log-ins to myGov15;

- 15.4 million links16 created to member services;

- 4.1 million user accounts linked to two or more member services;

- 163 million navigations17 to linked member services, with Centrelink and ATO the most accessed member services; and

- 67.9 million correspondence items sent to the myGov Inbox in 2015–16.

1.19 Figure 1.2 illustrates when member services became available through myGov and example activities.

Figure 1.2: Timeline when member services (and example activities) became available through myGov

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

International efforts

1.20 Governments around the world have implemented initiatives with similarities to myGov, generally as part of a wider e-government strategy. Table 1.6 summarises some comparative functionalities and services.

Table 1.6: International efforts

|

Country |

Statistics |

Functionalities within the platform |

Member services |

|

United Kingdom – Tell Us Once (online in 2012) |

14.6 million unique visitors, as at 29 January 2017; and 2.45 billion completed transactions per year. |

‘Tell Us Once’ functionality for births, deaths and bereavement |

One service delivered over many UK authorities, including Country Council and Districts |

|

New Zealand – igovt logon and RealMe |

3.01 million users, as at December 2016; and 56.6 million completed transactions, as at 30 January 2017. |

igovt logon service identity verification service (RealMe) |

Department of Internal Affairs and New Zealand Post, on behalf of 88 services, as at Dec 2016 |

|

Canada – Service Canada |

Number of users and transactions unknown. |

An integration of agency front-ends, leaving agencies and their back-ends unintegrated. |

Consolidates service delivery into a single government website that contains 90 per cent of the most popular information and forms. |

|

Singapore – Singapore Personal Access (SingPass) |

Over 3 million users as at July 2016; and 60 million transactions per annum. |

Online authentication system and ‘Tell Us Once’ functionality. |

Used by citizens to access over 60 government agencies and 270 e-services. |

Source: ANAO analysis of: UK’s Tell Us Once; New Zealand’s igovt and RealMe; Canada’s Service Canada; and Singapore’s SingPass.

Audit approach

1.21 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Human Services’ implementation of myGov as at November 2016. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- suitable governance arrangements were in place;

- myGov delivered a whole-of-government online service delivery capability;

- myGov improved service delivery for individuals;

- myGov provided an adequate level of performance, security and privacy; and

- myGov delivered value for money.

1.22 The ANAO examined the design, build and deployment phases of the myGov project. In particular the ANAO:

- reviewed project documentation, including approved funding and actual costs;

- reviewed the implementation of the agreed key functionalities in myGov;

- examined myGov research, surveys and usability testing conducted to assess individuals’ experiences, feedback and issues with myGov;

- examined Human Services’ monitoring and reporting of myGov performance, IT security and privacy measures; and

- interviewed Human Services, ATO and Digital Transformation Agency staff.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $620 000.

1.24 The team members for this audit were Judy Jensen, Alex Doyle, Lisa Elkner, Donna Burton and Elenore Karpfen.

2. Governance

Areas examined

This chapter examines the governance arrangements and planning processes established for myGov at a whole-of-government and operational level.

Conclusion

Fit-for-purpose strategic and operational governance arrangements operated for the first three years of the myGov project, followed by a one year gap in strategic governance when interim arrangements had a largely operational focus. This gap was addressed in July 2016 with the

re-establishment of a strategic governance board.

Areas for improvement

There would be benefit in identifying undelivered requirements from the original myGov specifications for member service consultation and securing a decision by the myGov Governance Board on whether they are still required. The Board can then incorporate the agreed undelivered requirements into its prioritisation and monitoring processes.

Were fit-for-purpose governance arrangements established?

Fit-for-purpose governance arrangements and sound planning processes were in place between 2012 and June 2015 to support the implementation of myGov. The governance framework had both a strategic and operational focus and featured: clearly defined roles and responsibilities; policies and processes that enabled consistent reporting on project implementation status, risks and issues, and performance; and arrangements to engage with government stakeholders.

In June 2015, these governance arrangements ceased and interim arrangements were established. The interim governance arrangements had a largely operational focus resulting in limited strategic oversight for myGov as a whole-of-government capability until July 2016. Revised governance arrangements were introduced in July 2016 which featured a new board to provide strategic direction and the retention of key operational committees.

2.1 The business case identified governance as one of the highest risks to the success of the proposed whole-of-government digital reforms. In this context, suitable governance arrangements were expected to be established to support the implementation and ongoing operations of myGov.

2.2 Over the course of the myGov project, the governance arrangements were significantly altered. Figure 2.1 depicts the governance arrangements over the four year project.

Figure 2.1: Governance arrangements for myGov 2012 to 2016

Note a: The Secretaries’ ICT Governance Board (SIGB) was dissolved in December 2014.

Note b: Assistant Minister for Cities and Digital Transformation.

Note c: Human Services’ Chief Digital Officer.

Note d: The Digital Transformation Agency’s Chief Executive Officer.

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ Reliance Framework and Authentication Project Management Plan pages 16–17, Implementation Committee Minutes, Reliance Framework Board terms of reference, Reliance Framework Reference Group terms of reference, Member Service Forum terms of reference, and myGov Governance Board terms of reference.

2012 to June 2015

2.3 The agreed governance framework established in 2012 included oversight by the Minister for Human Services18, a Secretaries’ ICT Governance Board, a Reliance Framework Board (the Board), a Reference Group, and a Working Group. The roles and responsibilities of these groups were clearly defined (see paragraph 1.14 and Table 1.5).

2.4 The Board, with members at the Deputy Secretary level from relevant entities, met monthly and provided direction on strategic matters and priorities, including cost sharing arrangements and issues with program delivery such as the intended design of key myGov functionalities. The Board also set out technical principles that made reference to common architecture standards. These technical principles were used to support the design and build of the myGov platform.

2.5 The Reliance Framework Reference Group (Reference Group), chaired by the ATO, drew its membership from 15 entities19, and enabled regular engagement with key government stakeholders.

2.6 The Working Group was an internal Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) forum that aimed to provide direction and leadership to project teams responsible for the delivery of myGov functionalities (discussed further in Chapter 3).

2.7 Human Services advised the ANAO that as myGov was hosted on its enterprise ICT systems the project was also subject to Human Services’ internal ICT project governance policies and processes. Relevant planning documentation was developed to support the implementation of myGov, including: a project management plan; a risk management plan; and other documentation such as detailed requirements documents, implementation schedules and work programs.

2.8 The Board received regular updates on myGov implementation, risks and issues, and performance, to facilitate strategic planning, issue resolution and reporting.

2.9 These original governance arrangements and planning processes were fit-for-purpose and supported effective monitoring and decision making of the design and implementation of myGov until June 2015.

July 2015 to June 2016

2.10 In January 2015, the Government announced that the Digital Transformation Office (DTO) would commence operations from 1 July 2015.20 In March 2015, the Government outlined the functions of the DTO, including to ‘provide leadership on government service delivery’ and ‘govern the implementation and enhancement of whole-of-government service delivery platforms’.21

2.11 The Reliance Framework Board expected myGov governance arrangements to transition to the DTO. The Board agreed at its June 2015 meeting that both the Board and the Reference Group would cease to operate.

2.12 In September 2015, as governance arrangements had not transitioned to the DTO, Human Services tasked its Implementation Committee with providing oversight for myGov until new whole-of-government arrangements were established. The Implementation Committee provided an interim governance solution for operational decision making for myGov.

2.13 In June 2015, a myGov Member Services Forum, chaired by Human Services, was established, enabling existing member services to continue to exchange operational information and discuss myGov strategy.

2.14 From July 2015 to June 2016, Human Services continued to deploy enhancements to the system in response to individuals’ feedback and reported issues—supported by its internal Implementation Committee. While the Member Services Forum enabled stakeholder engagement, there was no cross-government body to provide strategic direction and oversight to progress myGov as a whole-of-government capability.

From July 2016

2.15 In May 2016, the Government defined the respective roles and responsibilities of the DTO and Human Services with regard to myGov. From 1 July 2016, the DTO was made responsible for myGov service strategy, policy and user experience including: any changes to the current myGov service capabilities that related to policy objectives or user needs; and the on-boarding of new member services. Human Services continued to be responsible for myGov’s operational design, development, build, operation and performance and the operation of the myGov shopfronts.

2.16 In July 2016, new governance arrangements were established with the myGov Governance Board (myGov Board), chaired by the (now) Digital Transformation Agency (DTA)22, with membership drawn from 12 entities.23 The Working Group included representation from the DTA. The myGov Board reported to both the DTA’s Chief Executive Officer and Human Services’ Chief Digital Officer. Ministerial oversight was provided by the Minister for Human Services and the Assistant Minister for Cities and Digital Transformation.

2.17 The myGov Board has been tasked to provide strategic direction and oversight, including: improving the alignment of myGov with the Digital Service Standard; discussing future system needs and service delivery requirements with stakeholders; and pursuing opportunities with other government entities. The myGov Board’s terms of reference also include a responsibility to ensure member services’ requirements are taken into account in the delivery of the myGov service.

2.18 Since July 2016, the myGov Board has overseen policies and processes to progress the implementation of outstanding myGov fixes and enhancements, including a prioritisation process to address proposed changes to myGov. At present, a complete list of undelivered requirements is not reported to the Board. There would be benefit in identifying undelivered requirements from the original myGov specifications for member service consultation and securing a decision by the myGov Governance Board on whether they are still required. The Board can then incorporate the agreed undelivered requirements into its prioritisation and monitoring processes.

3. Delivering expected outcomes

Areas examined

This chapter examines the uptake of myGov by individuals; the delivery of key myGov functionalities, more streamlined business processes and agreed common standards; and progress towards delivering the expected benefits for individuals.

Conclusion

There were 9.5 million user accounts registered in myGov by the end of the four year project—nearly double the business case forecast of 5.1 million. myGov has contributed to improved delivery of government services for individuals by providing three key functionalities—single digital credential, Update Your Details and Inbox—to reduce the time spent transacting with government. Several requirements to improve usability have only recently been implemented and a small number of requirements are yet to be delivered. As at November 2016, there were ten government services available through myGov. While it is not mandatory for member services to participate in myGov, the effectiveness of myGov as a whole-of-government capability has been hampered by government services not joining myGov and not fully adopting the myGov functionalities.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the Digital Transformation Agency implement a targeted strategy to enlist Australian Government services to join myGov, and for Human Services to review existing transition support and guidance materials to ensure that they effectively support targeted government entities to interface their systems with myGov functionalities. The ANAO has also recommended that the Digital Transformation Agency establish a performance framework, including key performance indicators, to help assess if myGov is delivering expected outcomes.

3.1 The business case forecast that over the four year project (2012–13 to 2015–16) 5.1 million individuals would register with myGov and two major outcomes would be delivered:

- the first outcome was improved service delivery for individuals following the implementation of the five key functionalities—single digital credential, Update Your Details, Inbox, discoverability, and data validation; and

- the second outcome was improved online service delivery capability for government, including: a governance framework (discussed in Chapter 2); streamlined business processes; and common standards.

Was the expected uptake achieved and key functionalities delivered?

By June 2016, myGov had exceeded the expected uptake with over 9.5 million user accounts registered compared to the business case forecast of 5.1 million. myGov had almost 11 million accounts by November 2016.

Of the five functionalities expected to be delivered in myGov:

- Human Services delivered three key functionalities in myGov that enable individuals to: access government services online using a single digital credential; notify changes of personal contact details; and receive digital correspondence securely. A small number of requirements within these functionalities, which were considered mandatory for go-live, have not yet been implemented.

- The expected search functionality was partly delivered through an interim solution which enables individuals to perform structured searches of government services; however the expected free text searches envisaged by this functionality are not able to be performed in myGov.

- The data validation functionality was designed, but not delivered in myGov. Human Services advised the ANAO that this functionality was available via the Centrelink member service and that the use of this existing functionality was considered more efficient. As a consequence, a myGov user must link their account to Centrelink and access that service to use the data validation capability.

3.2 By June 2016, there were over 9.5 million user accounts registered in myGov compared to the business case forecast of 5.1 million for the four year project. By November 2016, myGov had almost 11 million user accounts.

3.3 myGov was expected to improve service delivery for individuals through five functionalities. The Department of Human Services (Human Services) commenced work on the design and build of these functionalities in late 2012. The Government had originally agreed that these key functionalities would be delivered within a two year timeframe, that is, by June 2014. Table 3.1 provides the ANAO’s assessment of the implementation and deployment of the key myGov functionalities.

Table 3.1: ANAO’s assessment of Human Services’ deployment of key functionalities

|

Single digital credential |

|

|

Proposal |

Ability to create an account and transact with government services using a single digital credential. An individual could use the same credential across all services they interact with, and chose a username and password that they are likely to remember. |

|

Approach |

Human Services proposed to repurpose its digital credential capability, built as part of its Connected Authentication project. In August 2012, Human Services designed and built the common credential capability. User names comprised two-alpha and six-numeric system generated identifiers (for example, AB123456). This project was transferred and completed under the myGov project in May 2013 when myGov was launched. In April 2014, the functionality was enhanced to enable individuals to create a profile to link to services and perform Update Your Details transactions. In June 2016, the ability to log in with an email address as the username was enabled. In December 2016, the option to use a mobile phone number as the username was enabled. |

|

Result |

Deployed – April 2014 Functionality met the base level requirements for the single digital credential. |

|

Update Your Details |

|

|

Proposal |

Originally titled Tell Us Once (TUO), this referred to the concept where an individual can notify multiple government entities about a change in their contact details in a single transaction, subject to consent, rather than having to notify each government service separately. |

|

Approach |

Human Services took a phased approach to implementing Update Your Details functionality. Phase 1: The ability to update personal addresses and notify Centrelink, ATO and Medicare was released in December 2014. Phase 2: The ability to update personal email and phone numbers, and notify Centrelink, ATO and Medicare was released in June 2015. Phase 3: The ability to notify other services was released in April 2016. There are some requirements categorised as mandatory—that were expected to be delivered prior to TUO going live—that are yet to be implemented.a |

|

Result |

Deployed – April 2016 Functionality met the agreed intent. |

|

Inbox |

|

|

Proposal |

Inbox is a digital inbox and a central location for receiving official correspondence from government services. Individuals will be able to opt in to the option of receiving government communication from member services into their Inbox instead of by regular paper mail. |

|

Approach |

Inbox was released in March 2014 as a secure location for individuals to receive official correspondence. myGov does not store the correspondence issued by member services; instead, it holds a link to the message stored on the member services’ own IT system. Since August 2014, individuals have the option of automatically forwarding myGov correspondence to their Australia Post MyPost Digital Mailbox. In June 2016, the ability to add and customise folders to group correspondence was introduced. There are some requirements categorised as mandatory— that were expected to be delivered prior to Inbox going live—that are yet to be implemented.b |

|

Result |

Deployed – March 2014 Functionality met the agreed intent. |

|

Discoverability |

|

|

Proposal |

Enhanced discoverability to easily find information and navigate to government services, via a search wizard where the individual can manually enter free text information. |

|

Approach |

In July 2014, the Minister for Human Services approved using Service Finder as an interim solution which was then deployed in myGov. Service Finder is directory listing of government services with grouped content boxes to assist individuals to navigate through to Australian, state, and territory government services. Service Finder does not support ‘passive’ discoverability or free-text searching. Service Finder is available after an individual has logged in to myGov. As at November 2016, the interim Service Finder search tool is still in place. |

|

Result |

Interim solution - July 2014 The deployed interim functionality partly met the agreed intent as it provided an improved search capability; however, it did not allow free text searching and it required users to be logged into myGov. |

|

Data validation |

|

|

Proposal |

The capability to validate facts submitted online, using the Document Lodgement System (DLS), reducing the need for documentation, includes validation of both identity and non-identity data. Data can be validated by an authoritative source such as the Attorney-General’s Department’s Document Verification Service (DVS).c |

|

Approach |

The capability to upload electronic files through DLS and have data validated through DVS was designed but not built in myGov. Human Services advised the ANAO that this functionality was available via the Centrelink member service and that the use of this existing functionality was considered more efficient. As a consequence, a myGov user must link their account to Centrelink and access that service to use the data validation capability. |

|

Result |

Not deployed in myGov This functionality is not available within myGov. The DLS and DVS capabilities previously existed for Centrelink and can be accessed by myGov users linked to Centrelink. |

Note a: The Tell Us Once Baseline Business Requirements v1.0 3/9/2013 page 7, requirement TUO01 ‘The customer will have the ability to provide changes to profile information to the myGov service which will result in all participating linked member services being provided the new/changed information.’ This is a mandatory requirement that had not been implemented as at November 2016.

Note b: The Inbox Baseline Business Requirements v1.0 3/9/2013 page 9, requirement MIB15 ‘Where a notification (email or SMS) is undelivered (bounces back) the Inbox will notify the member service/s … of the delivery failure.’ This is a mandatory requirement from September 2013 and scheduled for delivery in April 2017.

Note c: The Document Verification Service (DVS) is a national online system that allows organisations to take information from a person’s identity documents (such as a driver’s licence or passport number), with their consent, and compare against the corresponding record of the document issuing agency (such as the relevant Transport Authority in the state of issue or the Australian Passport Office).

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

Did myGov deliver more streamlined business processes and agreed common standards?

myGov was built using open standards, is scalable and is an authentication platform which can be integrated with member services. Centrelink, Medicare and the ATO member services are using all the available myGov functionalities, the adoption of which was expected to streamline business processes and improve the user experience. Three government services identified in the business case elected not to participate in myGov. Of the ten member services that decided to participate in myGov, six use some but not all of the available functionalities.

3.4 The business case outlined that myGov, as a whole-of-government capability, was expected to deliver: a governance framework (discussed in Chapter 2); streamlined business processes and agreed common standards.

Streamlining business processes

3.5 As myGov was expected to be a whole-of-government initiative, the business case recognised that successful implementation would require substantial involvement from participating entities and the adoption of relevant functionalities. Six Australian Government entities were identified in the business case as ‘service delivery’ entities, as they delivered services within the scope of myGov. Further, it was acknowledged that these entities would need to streamline their business processes and supporting ICT to accommodate myGov, including to: recognise the myGov digital credential; receive and process Update Your Details transactions; and amend mailing workflows to send correspondence electronically to the Inbox.

3.6 The six service delivery entities, representing eight member services, identified in the business case are listed in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Entities identified in the business case as ‘service delivery’ entities

|

Entities identified in the business case |

Joined myGov |

|

Human Services:

|

May 2013 (myGov launch) |

|

Department of Veterans’ Affairs:

|

May 2013 (myGov launch) |

|

Australian Taxation Office |

May 2014 |

|

Australian Electoral Commission |

did not join myGov |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

did not join myGov |

|

(then called) Department of Immigration and Citizenship |

did not join myGov |

Source: ANAO analysis of Reliance Framework business case.

3.7 Entities were not mandated or required to join myGov. The three Australian Government entities identified in the business case that elected not to join myGov24 (see Table 3.2) provide services such as passport renewals, update contact details to the electoral roll, and visa and immigration applications. The absence of these services in myGov impacts on the ability of myGov to deliver a whole-of-government capability and requires individuals to continue to use other channels to interact with Australian Government.

3.8 Other service delivery government entities did join myGov. By November 2016, there were an additional four Australian Government services and one state government member service operating through myGov, as listed in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Other entities that joined myGov

|

Additional entities |

Joined myGov |

|

Australian Digital Health Agency’s My Health Record |

May 2013 (myGov launch) |

|

Department of Employment’s Australian JobSearch |

December 2014 |

|

National Disability Insurance Scheme |

March 2015 |

|

Department of Health’s My Aged Care |

July 2015 |

|

Victorian Housing Register Application |

August 2016 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

3.9 Even with these additional services, the public advertising stating that myGov delivers online government services ‘All in one place’, (see Figure 3.1), remains aspirational.

Figure 3.1: Cover of a 2015 myGov information brochure

Source: Department of Human Services’ Information brochure, July 2015.

3.10 In respect to the services that did join myGov, not all have elected to use all of the available functionalities to streamline their business processes. Table 3.4 lists the Australian Government member services25 and the functionalities they are using to support their online service delivery (as at November 2016).

Table 3.4: myGov Australian Government member services and the functionalitiesa used as at November 2016

|

myGov member services |

Single digital credential |

Update Your Details |

Inbox |

Discoverability |

|

Human Services’ Centrelink |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Human Services’ Medicare |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Human Services’ Child Support |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Australian Taxation Office |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Department of Veterans’ Affairs My Account |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

National Disability Insurance Scheme |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Department of Employment’s Australian JobSearch |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

Australian Digital Health Agency’s My Health Record |

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

|

Department of Health’s My Aged Care |

✔ |

|

|

✔ |

Note a: Data validation is excluded from this table as it is not being provided directly within myGov.

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

3.11 As at November 2016, Centrelink, Medicare and the Australian Taxation Office were the only member services using all of the key functionalities within myGov. For the other six services: five services did not use Update Your Details and three services did not use the Inbox.

3.12 Human Services advised the ANAO that, at the time of joining myGov, member services made a commitment to use all key functionalities. Human Services further advised that the lower-than-expected take up of Update Your Details and Inbox resulted from a combination of member services’ decisions regarding:

- business processes—to capture and store individuals’ personal information submitted through Update Your Details;

- business systems—to issue letters in a digital format (such as PDF) to an Inbox; and

- business priorities—to adequately fund and resource activities needed to revise existing business processes, and enhance and/or interface ICT systems with myGov.

3.13 The Digital Transformation Agency advised the ANAO that member services’ use of myGov functionalities is also driven by their users’ needs and this may result in services opting to not use all functionalities.

3.14 As a whole-of-government capability, myGov was intended to be the preferred channel for users to access government services using the myGov single digital credential. In March 2014, the ATO joined myGov offering its e-tax, myTax and mobile services. To ensure ATO users used myGov—with a myGov digital credential—the ATO removed direct access to its online services through the ATO web site and instead linked to myGov.

3.15 Other member services did not adopt the same approach; instead they allowed users to continue to directly access their services using other credentials—in particular, Centrelink and DVA’s My Account. Individuals do not access the full benefits of myGov functionality while they continue to use alternative online channels to transact with government.

3.16 For myGov to realise its full potential as a whole-of-government online service delivery capability: a strategy should be developed to make more government services available through myGov; and member services should be encouraged to use the functionalities available, where aligned with business and user needs. The government services that provide the greatest benefits for individuals and government should be proactively targeted as part of future myGov on-boarding efforts.

Recommendation No.1

3.17 The ANAO recommends that the:

- Digital Transformation Agency implement a strategy to target ‘service delivery’ Australian Government entities to provide services through myGov; and

- Department of Human Services review existing transition support and guidance materials for entities to ensure that they effectively support targeted government entities to interface their systems with myGov functionalities.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

3.18 The department has commenced work to simplify the current onboarding process to assist government entities to interface their systems with myGov functionalities.

Common standards

3.19 The business case outlined that entities could retain their own online offerings but would establish common standards so that entities could ‘rely’ on each other.26 These standards, for example authentication levels and common taxonomy, would streamline future changes to online service offerings and enable government to engage more quickly and more systematically with third-parties and emerging digital opportunities.

3.20 The Reliance Framework Board (the Board) had responsibility for developing and documenting the relevant open technical standards, as agreed by government. The Board established a set of technical principles that referenced common architecture standards. These technical principles were then used in supporting the design and build of the myGov platform. myGov has delivered this outcome, as it was built using open standards, is scalable and is an authentication platform which can be integrated with member services.

3.21 In May 2016, the Digital Service Standard was released by the Digital Transformation Agency27 (DTA) to define the service design and delivery standard for ICT projects across the Australian Government.28

3.22 myGov was the first existing high volume service to be examined for alignment with the 2016 Digital Service Standard. A review performed by the DTA identified a number of areas where steps could be taken to better align the system with the Digital Service Standard. This review also noted that myGov is the entry portal and does not control the service design and delivery standard of its member services.

Does myGov provide a basis for improved service delivery for individuals?

The myGov platform has provided a basis for improved service delivery, including a reduction in the time spent by individuals interacting with government. This benefit accrues where individuals use the myGov functionalities to receive correspondence or update their details, and in particular, where individuals link their account to at least two member services. Where individuals already had multiple online credentials, they incur a one-off time cost to join myGov. Individuals who do not have their account linked to multiple services do not receive the potential time saving benefits to the same extent.

3.23 According to the business case, myGov was expected to improve service delivery for individuals who choose to self-manage their interactions with government, as they could spend less time transacting by using the myGov functionalities.

3.24 Table 3.5 summarises the circumstances in which individuals could expect to receive improved services. Individuals could expect to realise the full extent of the time-saving benefits where they had multiple member services linked to a single account, and where they were able to complete their transaction completely online without having to resort to an alternative service channel. Human Services reported in its November 2016 Performance Report that 46 per cent of myGov accounts were linked to two or more services.

Table 3.5 Expected service delivery improvements derived from myGov functionalities

|

Functionality |

Expected service improvement |

Expected to be realised by |

Not realised by |

|

Single digital credential |

Individuals can create one account to access all services offered through myGov with one set of credentials. |

Individuals who previously did not have online accounts with member services. Individuals who link their myGov account to more than one member service should derive greater time saving benefits through not having to create multiple credentials. |

Individuals who previously held on-line credentials with the ATO, Centrelink and/or Medicarea were required to incur a one-off time cost to create new credentials with myGov. Individuals who have experienced a locked myGov account and have had to recreate myGov credentials and re-link to each of their member services. |

|

Update Your Details |

Individuals are able to update their contact details once and request to have this information shared with other participating services—Centrelink, Medicare, ATO and Jobsearch. |

Individuals with an account linked to more than one participating member service and use this functionality to update their details should derive time saving benefits compared to using traditional channels. |

Individuals who choose to link to only one member service would not realise the time saving benefit. |

|

Inbox |

Individuals are able to securely receive electronic correspondence from participating services—Centrelink, Medicare, ATO and NDIS—with improved timeliness than traditional mail. |

Individuals with accounts linked to one or more of the participating services. This includes ATO, Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support. Some of these services did not previously have an inbox service and the myGov Inbox provides improved security allowing a greater range of communications to be sent electronically. |

Individuals who do not have links with the participating services would not realise the improved service. |

|

Service Finder |

Individuals are able to more easily find information regarding government services. |

All myGov account holders can access the Service Finder tool once they have logged in. Individuals are not able to perform free text searches using Service Finder. |

|

|

Data validation |

Individuals able to provide documentation online to validate identity and facts, rather than having to use other channels. |

Not applicable, as this functionality was not delivered in myGov. |

|

Note a: Some individuals were interacting directly with Medicare, Centrelink, ATO and other member services online prior to myGov.

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ information.

3.25 Performance monitoring conducted by Human Services has identified that less than one per cent of people signing on to myGov call the myGov Help Desk. There are no specific measures in place to quantify the transactions completed without reference to another channel, or to identify the reasons why a transaction may have been abandoned before it was completed. However, research sponsored by DTA and Human Services29 identified the following as particular issues for people accessing member services via myGov:

- difficulties in remembering user credentials and passwords, leading to accounts being locked;

- difficulties in understanding the error messages or other feedback given by the system, leading users to seek assistance via another channel (call centre or shopfront); and

- a lack of feedback from the system about the status of the transaction, again leading to individuals seeking assistance via another channel.

3.26 While some data is publicly available on myGov performance30, it does not extend to measuring user outcomes. The DTA has recognised the need to continually evaluate how the myGov service delivers on the expected user outcomes, by establishing and monitoring a set of key performance indicators (KPIs). Further, the DTA identified that KPIs should include an emphasis on the user experience, with both qualitative and quantitative sources to help highlight gaps in delivering the expected user outcomes. It is important to identify key performance indicators that are relevant, reliable and complete31 to demonstrate progress towards meeting outcome objectives.

Recommendation No.2

3.27 The ANAO recommends that the Digital Transformation Agency, in consultation with the member services, establish a performance framework, including key performance indicators focussing on outcomes, to enable an assessment of the extent to which myGov is delivering expected outcomes for users and member services.

Digital Transformation Agency’s response: Agreed.

4. Project implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines implementation of the myGov project with a focus on system performance, security and privacy, and whether feedback was monitored and used to inform system changes.

Conclusion

Since late 2015, the myGov platform has been hosted on high-availability infrastructure, which has improved performance, especially during peak demand periods, with performance targets consistently met. Suitable security and privacy measures were in place to control access and protect sensitive data stored in myGov.

4.1 In August 2012, the Government agreed that the Department of Human Services (Human Services) would be the lead entity for the myGov project implementation. Human Services administers and hosts myGov, including processes and procedures for system development and testing, security, and operational performance.

Did system performance meet targets and were suitable security and privacy measures in place?

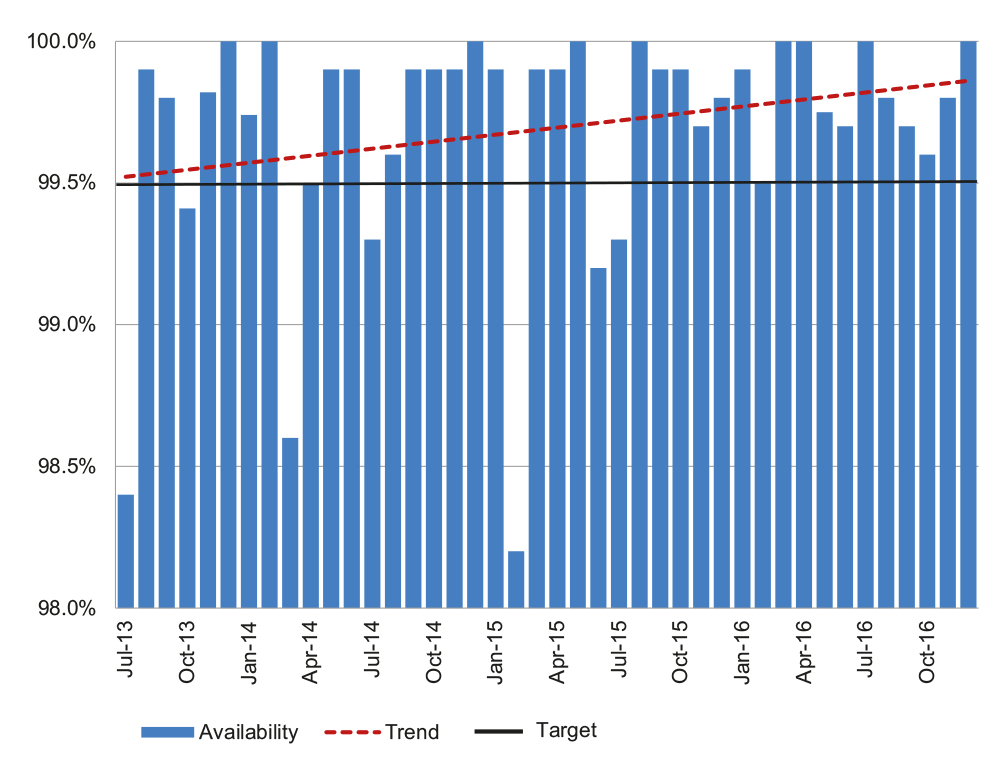

In December 2015, Human Services introduced high-availability infrastructure to support the increased demand for myGov during peak periods. Since this time, Human Services has reported that myGov’s performance has met or exceeded the monthly availability target of 99.5 per cent.

Suitable security and privacy measures were adopted for myGov, leveraging existing Human Services arrangements to control access and protect data. In addition, myGov stored only limited sensitive personal data and did not facilitate data sharing between member services.

System performance

4.2 The business case did not define system performance standards for myGov. According to international best practice proposed by ISACA32, maintaining IT system performance requires the implementation of processes that include:

- regularly reviewing the current performance and capacity of systems;

- achieving response time to the agreed availability target level, including reducing the downtime of the system; and

- delivering continuous improvements through monitoring and measurement.

4.3 Throughout the project Human Services regularly reviewed myGov operations, performance and capacity as part of its broader ICT operations, through the Human Services’ Enterprise Network Operations Centre. Key aspects of these reviews were documented in monthly myGov Performance Reports, including IT incidents, actions taken and system availability. There was also real time performance monitoring and additional reporting of performance and system availability during peak demand times.

4.4 In July 2015, during the taxation lodgement period, performance and availability issues with myGov were reported. During this month, myGov’s availability was 99.3%, falling somewhat below the availability target of at least 99.5 per cent—or less than 3.60 hours of downtime per month—set out in the relevant Service Level Agreements with member services.

4.5 In December 2015, Human Services moved myGov to new high-availability infrastructure and established processes to scale the system and accommodate increases in users and services. For the following year’s peak taxation lodgement period between July and October 2016, Human Services increased myGov’s system capacity to over 120 per cent of the average year capacity.33 From August 2015 to November 2016, Human Services reported in its monthly Performance Reports that myGov achieved or exceeded the monthly average availability target. Figure 4.1 illustrates myGov system availability from July 2013 to December 2016.

Figure 4.1: myGov system availability 2013–2016

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ reporting.

Security

4.6 Government entities must comply with security requirements as outlined in the Australian Government Information Security Manual. In ANAO Audit Report No. 42 2016–17 Cybersecurity Follow-up Audit, Human Services’ ICT environment was assessed as a having a high level of protection from: external cyber attacks; internal security breaches; and unauthorised information disclosures.

4.7 As myGov is hosted within Human Services’ ICT environment, it is subject to Human Services’ ICT security measures. Security measures in place for myGov have included:

- an endorsed System Security Plan that covers security management procedures for myGov;

- penetration testing and gateway vulnerability assessments. These were performed;

- Threat Risk Assessments and Risk Treatment Plans. These were in place;

- authentication controls to reduce the risk of unauthorised access and disclosure of personal data—sign-in to myGov requires a username and password, and answers to several security questions or a one-time verification code that is sent via email or SMS; and

- restricting the amount of personal data stored within myGov to key data required for identification purposes. A myGov profile is created only once an individual has successfully linked to Centrelink, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) or Medicare. The following data is stored in the myGov profile: individual’s legal first name; surname; and date of birth. Data provided during the member service linking process is not recorded in myGov.

4.8 Under the Service Schedule, it is the responsibility of the member service, rather than Human Services, to ensure that an individual’s data held by the member service is secure from unauthorised access and disclosure. This audit did not assess the security measures implemented by other member services or their compliance with the Information Security Manual.

Privacy

4.9 Maintaining individuals’ privacy was both a key aim of myGov and a key risk. It was recognised in the business case that the success of myGov depended, in part, on building trust and convincing individuals their personal information was secure.

4.10 myGov’s release in May 2013 was subject to a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) to assess the privacy impacts of its design and operation. Human Services addressed all the PIA’s recommendations prior to implementation. Human Services also adopted the ‘privacy by design’ approach for myGov whereby:

- individuals would be able to opt in and out of using myGov at any time;

- any flow of information would be controlled by the individual and not member services; and

- there would be no merger or linking of member services’ databases, and no centralised national identity database.

4.11 The ability for an individual to hold multiple myGov accounts was a deliberate design feature of the system, to address privacy concerns.

4.12 Human Services commissioned a series of PIA reviews during the course of the myGov project. The findings from the January 2015 PIA confirmed the ‘privacy by design’ principles continued to be met. The findings included:

- design principles minimise the collection of personal information;

- collection of personal information was relatively limited, and was considered reasonable because it was voluntary and with consent as part of agreeing to mandatory terms of use;

- profile data—such as name and date of birth—was held separately and access was restricted;

- use of different names in different contexts was no longer possible due to the use of the profile. Failure to use the same name meant that the authentication process may fail; and

- myGov was not a central database and did not capture interactions between government services.

4.13 Human Services advised the ANAO that its staff are expected to comply with the Privacy Act 1988 and are also expected to comply with thedepartment’s internal Operational Privacy Policy requiring, for example, reading and signing the Privacy and Confidentiality Responsibilities document, and undertaking privacy training.

4.14 Data matching is conducted between defined government entities—under the Data-matching Program (Assistance and Tax) Act 1990—but is not facilitated by myGov. In addition, relevant service delivery transactions are performed within the member services’ own systems and not in myGov.

Did Human Services have processes to monitor feedback and inform myGov’s roll-out?

Human Services and participating entities captured feedback through surveys and usability testing to inform myGov’s roll-out. The feedback was used to correct faults and enhance myGov functionalities, but some resolutions were not delivered in a timely manner. From July 2016, the Digital Transformation Agency has had responsibility for the myGov user experience and, with Human Services, has developed and progressed a program of work based on a prioritised backlog list of fixes and enhancements.

A Closure Report has been prepared identifying lessons learned from the project, and two post-implementation reviews were conducted on specific aspects of the project as they were delivered. A post-implementation review for the project as a whole has not been completed.

4.15 Human Services was responsible for capturing, monitoring and addressing myGov feedback until June 2016. As noted in Chapter 2, the Government decided that from July 2016 the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) would assume responsibility for the myGov user experience.

4.16 There were many channels for individuals to provide feedback or make complaints, including through myGov online, through the Human Services website, by calling the myGov Help Desk, at shopfronts, or through social media. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) advised the ANAO that member services also provided feedback through an interagency change request process to request future enhancements.

4.17 Since January 2013, Human Services, ATO and the DTA have conducted multiple surveys and usability testing, to gather input on proposed functionalities, obtain feedback on ease of use and level of satisfaction, and to identify areas for improvement (see Appendix 2). Human Services advised the ANAO that this information was also incorporated into the feedback process.

4.18 Feedback, complaints and issues were also captured by Human Services in the Customer Feedback Tool. This data was used to inform future work activities, including correcting faults and enhancing myGov functionalities, and the identification of a Top Ten list of reported issues with myGov. The Top Ten issues list was periodically reported in the monthly myGov performance reports to the Reliance Framework Board and updated as issues were addressed and new issues arose. There were also issues reported about myGov’s performance and usability that related to a member service, rather than directly to myGov.

4.19 While Human Services had procedures in place to capture, analyse and prioritise individuals’ and member services’ feedback and reported issues, some resolutions and corrective actions were not delivered in a timely manner. For example, Human Services was aware of the reported issues with the myGov sign-in process since September 2014. Resolving this issue was reportedly Human Services’ top priority, as set out in its Top Ten list of reported issues. However, a resolution was not implemented until June 2016—more than 21 months later. Human Services advised the ANAO that the delay resulted from the need to apply to government for additional funding to deliver this requirement.

4.20 In March 2016, the Prime Minister directed Human Services and the DTA to deliver a high-level plan of work for myGov spanning the next 12 months and a future vision for myGov services.

4.21 In April 2016, the DTA conducted a research survey which included myGov user experiences and identified user issue themes. These themes were grouped into five categories:

- sign-in was an entry hurdle particularly in recalling complex usernames and passwords, and there was a dependency on email addresses and mobile numbers for authentication;

- users created workarounds to avoid regularly using myGov;

- lack of feedback on what is going wrong made users anxious due to their inability to resolve issues themselves;

- language was too complex and users struggled to understand instructions and self-serve; and

- accessing services through myGov required a level of government knowledge and users believed they received a better level of services through non-digital channels.

4.22 The DTA findings also concluded that there needed to be a stronger focus on user outcomes, rather than specific myGov functionalities to provide the most value to users and government.

4.23 The ANAO invited members of the public to contribute information to this audit and received over 200 submissions. Over one-third of the submissions were complaints relating to a specific member service, and were not directly related to myGov. Some submissions related to member services’ interactions with myGov. For example, the ANAO received a submission regarding how the myGov Inbox has changed the way tax agents receive correspondence; resolution of this issue would require a change to the ATO’s business processes rather than a technical fix to myGov.

4.24 Of the remaining feedback received by the ANAO, the top three issues identified were: login difficulties; problems with setting up an account or linking to a member service; and myGov being ‘not user friendly’. These issues are consistent with user issue themes discussed in paragraph 4.21.