Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Mental Health in the Australian Federal Police

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Australian Federal Police in managing employee mental health.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Managing employee mental health effectively is a challenge faced by policing and first responder organisations around the world. This includes the Australian Federal Police (AFP) as the Australian Government’s primary policing agency responsible for the enforcement of Commonwealth laws and the protection of Australian interests from criminal activity, both domestically and overseas. To fulfil this role the AFP is responsible for a diverse range of functions, the delivery of which place a range of unique demands and stressors on AFP employees.

2. Safe Work Australia’s Work-Related Mental Disorders Profile 2015 concluded that first responders—police, emergency and health services—were the combined occupational group most likely to make a workplace compensation claim based on mental health injury, with incidence rates and costs substantially exceeding other occupational groups.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Australian Federal Police in managing employee mental health.

4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Has the AFP implemented sound governance and risk management practices to manage employee mental health?

- Is the AFP effectively managing employee mental health throughout their career lifecycle?

- Are sound monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements in place to assess the effectiveness of the AFP’s management of mental health?

Conclusion

5. The AFP lacks a comprehensive and consolidated organisational health and wellbeing framework to enable effective management and support of employee mental health. While the AFP offers a variety of mental health support services, there is no evidence that these services are effective and they are not supported by sound governance, risk management, evaluation or an articulated business rationale. Any reform of the portfolio of services available should be made in the context of available data on employee access, areas of high stress and risk, gap analysis, organisational culture and employee preferences.

6. The AFP has identified gaps in its management of employee mental health across the organisation and has commenced processes, within existing organisational constraints, to improve the management of employee mental health, which is a complex and sensitive challenge for the AFP and other first responder organisations. Since the end of 2016, eight initiatives have commenced to improve mental health management across the AFP, including a review of AFP’s mental health support services, the establishment of a Mental Health Strategy Board, the launch of an expanded Welfare Officer Network and a wellbeing application (app)—Equipt.

7. While currently developing a mental health framework, the AFP has not established a clear governance structure for decision-making, information sharing and oversight in relation to employee mental health arrangements. Reporting into the governance structure is not comprehensive or risk-based, making it difficult to identify emerging mental health related risks and to utilise this reporting to inform decision making in resource prioritisation to address increasing mental health risks.

8. The AFP formally included mental health as a strategic risk to the organisation in October 2016, however this risk identification has not led to substantive engagement and coordinated identification of mental health risks faced by all of the AFP’s functional areas.

9. The AFP does not currently have in place mechanisms or sufficient data to appropriately align resources with key mental health risks.

10. Screening processes are in place to assess the suitability of employees’ psychological readiness for sworn roles. These are undertaken consistently as part of the recruitment process into the AFP. Required screening processes are not always taking place prior to an existing employee commencing in a high risk / specialist role with the AFP. Therefore the AFP is not provided with the assurance that all employees in these roles have been assessed as suitable for high risk roles.

11. Individual training courses have been developed by the Psychological Services team in response to operational requests in specific areas, however the AFP does not have a specific mental health training framework that identifies the competencies and resilience levels required by employees at different stages in their AFP career to inform delivery and prioritisation of training.

12. Current mechanisms used for identifying employees at risk of psychological injury are limited in effectiveness and do not occur routinely.

13. There are weaknesses with the AFP’s rehabilitation and return to work arrangements for employees suffering from a psychological injury sustained during their employment with the AFP. These relate to the lack of mental-health specific rehabilitation policies, procedures and training.

14. The AFP has a range of mental health support services available for employees to access. Recent employee feedback has indicated that the availability and effectiveness of these services is varied, and that there are no systemic arrangements to evaluate support service effectiveness on an ongoing basis. Feedback also indicated that cultural barriers to accessing support and assistance reduces the potential impact of these services.

15. Information on employee mental health is held across a range of disconnected information systems and multiple hardcopy records which make it difficult for the AFP to monitor and respond to emerging issues.

16. The AFP undertakes a range of internal reporting on mental health metrics and performance for internal oversight committees.

17. The external review currently being conducted of the AFP mental health support services, commenced in 2017, provides the AFP with the opportunity to inform the selection and resourcing of the most effective mix of support services to support the mental health needs of AFP employees.

Supporting findings

Governance and risk management

18. The AFP does not have in place an organisational health and wellbeing strategy which incorporates policies, programs and practices to address mental health risks. The AFP is developing a draft Mental Health Framework and Mental Health Strategic Action Plan, and finalisation of these is dependent upon the outcome of a review of AFP mental health services that was not yet finalised at the time of drafting this report.

19. The AFP has defined the roles and responsibilities of individual employees and managers at different organisational levels for supporting employee mental health. However, the AFP has not established a clear governance structure for decision-making, information sharing and oversight in relation to employee mental health arrangements. This includes both organisational and committee arrangements.

20. The AFP formally recognised mental health as a strategic risk to the organisation and began developing treatment actions in October 2016. This strategic risk identification has not led to substantive engagement by all functional areas. Employee mental health has not been consistently identified as a risk in the AFP’s functional risk assessments and it is not evident that the AFP is co-ordinating the management of mental health as a shared risk (that is, between Organisational Health and functional areas).

21. The AFP does not have arrangements to ensure resources and funding are aligned to key mental health risks.

22. AFP allocates centralised funding to the Organisational Health function to resource mental health support activities. Each functional / geographical area may choose to allocate a portion of its annual operating budget to employee mental health but there is no information or assurance that funding is being spent in line with risk.

Prevention, identification and return to work of psychological injury

23. The AFP has established employment screening processes for mental health but these are not fully effective. The AFP has in place structures for undertaking assessments to ensure that employees possess the physical and psychological competencies required for AFP work. ANAO analysis indicates that required psychological assessments are being undertaken consistently at the pre-employment stage, however are not being undertaken in all instances prior to internal staff movements into specialist roles with higher mental health risk profiles.

24. The AFP has arrangements in place for preventing psychological injury but these are not fully effective as the AFP does not have a specific mental health training framework as a pre-emptive measure to improve employee resilience.

25. The AFP relies on three key mechanisms for identifying employees at risk of psychological injury: employee self-reporting; supervisor observation; and mental health assessments and psychological debriefs following deployment. There are limitations that reduce the effectiveness of these mechanisms, specifically:

- cultural barriers that reduce the likelihood of AFP employees self-reporting psychological injury;

- limited training and support for supervisors in identifying and supporting employees at risk of psychological injury; and

- inconsistent delivery and tracking of mandatory mental health assessments and psychological debriefs.

26. There are weaknesses with the AFP’s rehabilitation and return to work arrangements for employees suffering from a psychological injury sustained during their employment with the AFP. In particular, the draft 2017 AFP Mental Health review identified the lack of mental health-specific rehabilitation policies and the absence of mental health training for rehabilitation case managers to allow them to inform, assess or guide appropriate return to work for staff with psychological injury. Improving return to work arrangements to support better outcomes for injured employees remains a challenge for all organisations.

Mental health support services

27. The services offered by the AFP are not fully effective in supporting employee mental health. The AFP has seven support services available to employees that have mental health support elements, in addition to a range of related initiatives. Feedback from the draft 2017 AFP Mental Health Review and audit interviews with AFP personnel indicates that the availability and effectiveness of these services is varied. There are no systemic arrangements to evaluate the effectiveness of support services on a regular basis.

28. The AFP does not have a framework in place to evaluate the effectiveness of mental health support services and management arrangements. In 2017 the AFP commenced an external review of mental health support services for employees. The review is examining the AFP support services. In 2017, AFP also undertook an internal review of the Confidant Network.

29. In developing the strategy for managing AFP employees’ health and wellbeing, the AFP should incorporate regular reviews of the effectiveness of the mental health support services, as well as evaluating the appropriateness of the overall mix of services in terms of coverage, use by employees and value for money.

30. The AFP’s information on employee mental health is held across a range of disconnected information systems and multiple hardcopy records which make it difficult for the AFP to monitor and respond to emerging issues in employee mental health.

31. The AFP holds data in areas such as workplace health and safety incident reporting, Comcare claims, unscheduled leave, exposure to critical incidents and explicit material and information on deceased personnel which, if linked and analysed appropriately, could assist in identifying known psychological injury risk factors. There is an opportunity for the AFP to conduct such analysis and inform more targeted monitoring and support services.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.21

The AFP develop a comprehensive organisational health and wellbeing strategy and governance arrangements based on an integrated approach to staff mental health and wellbeing which incorporates policies, programs and practices that address the AFP’s specific risk profile.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.34

The AFP analyse, define and report on mental health risks across the organisation in a consistent manner and develop arrangements to align employee mental health and wellbeing resources to areas assessed as highest risk. During this process the AFP should also assess the effectiveness of the existing controls and treatments used to mitigate mental health risks.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.22

The AFP implement a mandatory mental health training framework for all AFP employees, tailored to the various capability requirements throughout their career lifecycle that provides information on identifying signs and symptoms of mental health injury (in self and others) as well as guidance on how to conduct meaningful conversations with staff and colleagues about their mental health.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 3.46

The AFP develop formal processes to monitor and provide assurance that:

- employees in specialist roles have their psychological clearance in place before commencing in the role; and

- mandatory mental health assessments and psychological debriefs are undertaken for all those who require them, in a timely manner.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 4.40

The AFP, in reviewing available support service options, uses a risk-based approach to determine the optimal mix of services to target identified organisational mental health risks, including:

- linking the outcomes of that review with the development of an organisational health and wellbeing strategy;

- ensuring the health and wellbeing strategy also addresses the cultural change required to support and encourage employees to access mental health services when required, particularly after involvement in critical incidents or prolonged exposure to high-stress roles; and

- establishing performance measures for the selected support services, and implementing monitoring and evaluation arrangements to ensure those services are systematically assessed.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 4.64

The AFP:

- consolidate disparate systems and hard copy records in order to establish an electronic health records management system that allows a single point of access to high level health information for each AFP employee; and

- establish a strategy for analysing employee health information against data in areas such as workplace incident reporting, Comcare claims, unscheduled leave, exposure to explicit material and information on deceased personnel in order to assist in identifying and addressing known psychological injury risk factors.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

32. The proposed audit report was provided to the AFP. An extract of the proposed report was provided to Davidson Trahaire Corpsych.

33. Formal responses to the proposed audit report were received from the AFP and Davidson Trahaire Corpsych. If the entity provided a summary response, these are below, with full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Australian Federal Police

Thank you for the opportunity to consider and provide comment to the proposed report to Parliament on Managing Mental Health in the Australian Federal Police. The high risk nature of the operational work undertaken by AFP employees carries an inherent risk of psychological harm and/or injury. To that end, I [the AFP Commissioner] welcome your report to assist myself and the AFP to continue to improve the support and services we provide to our staff to provide the highest level of safety and wellbeing for them. The AFP has provided a full response to the Australian National Audit Office addressing each recommendation, in addition to this summary response.

As your report highlights, there are unique considerations in the delivery of health and wellbeing services for high-risk organisations such as the AFP. The dynamic and evolving nature of crime means our support areas must be as agile, responsive and adaptable as possible. The AFP recognised the need for enhanced mental health support and in 2016 engaged Phoenix Australia to undertake a review of mental health in the AFP.

We acknowledge that the AFP needs to change in order to meet the growing demand and complexity of the environment in which the AFP operates. Even within current staffing levels, the AFP is working under immense pressure and ongoing activity at current operational tempo will increase health risks for its staff.

We have invested significant resourcing over many years in employee health however know we have some way to go in this journey. I thank the Australian National Audit Office for prioritising the mental health of AFP employees in producing this report. The senior leadership group and I are committed to prioritising and protecting the mental health of all our employees.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings and areas for improvement identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Commonwealth entities in managing the mental health of employees.

Governance and risk management

Contract management

Records management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Managing employee mental health effectively is a challenge faced by policing and first responder organisations around the world. This includes the Australian Federal Police (AFP) as the Australian Government’s primary policing agency responsible for the enforcement of Commonwealth laws and the protection of Australian interests from criminal activity, both domestically and overseas. To fulfil this role the AFP is responsible for a diverse range of functions, the delivery of which place a range of unique demands and stressors on AFP employees.

1.2 Safe Work Australia’s Work-Related Mental Disorders Profile 2015 concluded that first responders—police, emergency and health services—were the combined occupational group most likely to make a workplace compensation claim based on mental health injury, with incidence rates and costs substantially exceeding other occupational groups.

1.3 The AFP employed 6540 staff, both sworn officers and professional staff1, as at 30 June 2017.

Defining mental health

1.4 Good mental health is defined by the World Health Organization as:

a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community’.2

1.5 Mental illness refers to a health condition, diagnosed to standardised criteria, that significantly affects how a person feels, thinks, behaves, and interacts with others. Mental health problems interfere with a person’s thinking, feeling and behaviour but to a lesser extent than mental illness. Mental health problems are less severe, but left untreated can develop into mental illness. Mental health problems can be an individual’s temporary responses to external stressors.3

1.6 In this report the term ‘mental health’ is used to reflect a spectrum of conditions, rather than focusing solely on acute presentations of injury. The term ‘psychological injury’ is used consistently with Comcare4 terminology, which defines it as ‘a range of conditions relating to the functioning of people’s minds. While often prompted by workplace stressors, these conditions can be caused by physical injuries, disease, exposure to toxins or underlying psychiatric issues’.5

Mental health in the workplace

1.7 Employee mental health is closely linked to a range of factors that are both individual and organisational. In particular, an entity’s organisational culture, which consists of leadership and management practices as well as organisational structures and processes (such as appraisal and recognition processes, decision-making styles, clarity of roles, and goal alignment), has a strong influence on employee wellbeing and mental health. An individual’s physical health, personal situation and cultural environment all interact with and shape overall wellbeing.6 The term ‘organisational health’ in this report therefore refers to both the organisational and individual factors that contribute to employee wellbeing and organisational performance, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Factors influencing employee wellbeing and performance

Source: ANAO analysis based on World Health Organisation and academic research.

1.8 Studies have investigated the relative contributions of organisational culture, employment experiences, personality and coping strategies to levels of wellbeing among police officers. These studies indicated that organisational culture exerted the strongest influence on overall levels of wellbeing for police officers. The interaction between exposure to traumatic incidents and negative organisational experiences has been described in academia as the ‘erosive stress pathway’, which can accelerate mental health injury.7

1.9 The 2016 Victoria Police Mental Health Review identified that mental health risks were associated with operational incident exposure levels, personal stressors and organisational stressors, ‘particularly leadership behaviours, co-worker interactions, tolerance level for bad (counter-productive) behaviours and workload pressures’. In contrast, ‘supportive leadership styles and a positive high quality team climate serve[d] as protective factors’.8 The Queensland Audit Office report, Managing the mental health of Queensland Police employees, noted that the nature of first responders’ work, ‘both the tasks (situational stressors) and conditions (organisational stressors, such as shift work and work culture)—can pose a significant threat to mental health’.9

1.10 These review findings were consistent with concerns raised by current and former AFP employees that organisational stressors were also a contributor to their mental health, or compounded situational stressors.10

Mental health and the AFP

1.11 The AFP operates in a high risk environment for employee mental health given the diverse range of functions it is responsible for delivering—as outlined in Table 1.1. These functions place a varied range of demands and stressors on AFP employees, which are unique compared to the majority of other Australian Government entities.

Table 1.1: Summary of AFP functions

|

AFP functionsa |

|

|

Operations |

|

|

Protection and security |

|

|

Operational/specialist support |

|

|

International operations |

|

|

Other support services |

|

Note a: Table 1.1 lists AFP functions in generalised categories and does not reflect the AFP’s organisational or reporting structure.

Note b: This includes Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Norfolk Island and Jervis Bay.

Note c: Personal protection in Australia and overseas for Australian high-office holders, Commonwealth public officials and foreign dignitaries in Australia.

Note d: Physical security for Commonwealth facilities such as Australian Parliament House, defence facilities and for diplomatic missions in Australia.

Note e: Planning and provision of security for designated special events, such as the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Note f: Includes: tactical response; search and rescue disaster response; detection dogs; police negotiation; bomb response; maritime (water and dive) response; communications response; and air security officers.

Note g: AFP maintains a network of liaison officers located across 29 countries.

Source: ANAO analysis of AFP documentation.

1.12 The nature of the AFP’s functions result in staff being exposed to traumatic events such as:

- crime scenes and deceased persons;

- child exploitation material;

- terrorism material;

- victims of crime and their families;

- disaster and accident scenes;

- violence against police;

- extreme violence with limited powers to respond (overseas); and

- remote and isolated work environments in Australia and overseas.11

1.13 Exposure to traumatic events can occur repetitively over an AFP employee’s working life, which can then be associated with an increased vulnerability to the cumulative effects of such incidents both during the employee’s career and post career.12

1.14 The wide geographical distribution of AFP staff across both Australia and overseas, and the differing stressors and traumas to which they may be exposed, present a unique challenge for the AFP in providing appropriate mental health support services to its staff and identifying when and where these support services are required.

Work health and safety framework

1.15 Under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011, the AFP has the primary duty of care to ensure, so far as is reasonably practical, the health and safety of its workers while they are at work, including both physical and psychological health. Comcare and the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission are established under the Safety Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1988 (SRC Act), and jointly administer the statutory framework for rehabilitation and workers’ compensation for all Commonwealth entities, including the AFP.13

1.16 Where an AFP employee has a work-related injury or illness, they may seek support to recover from the injury or illness by making a claim to Comcare. The Comcare benefits and entitlements may include: medical expenses, travel costs, household and attendant care, assistance aids or modifications, incapacity benefits, permanent impairment and death benefits. Comcare makes a determination under the SRC Act as to whether an injury claim is accepted or rejected. In 2016–17 Comcare took an average of 54 days to reach a determination for accepted psychological injury claims made by AFP employees—down from 125 days in 2007–08. If an injury claim is rejected, Comcare has a process for reviewing determinations.

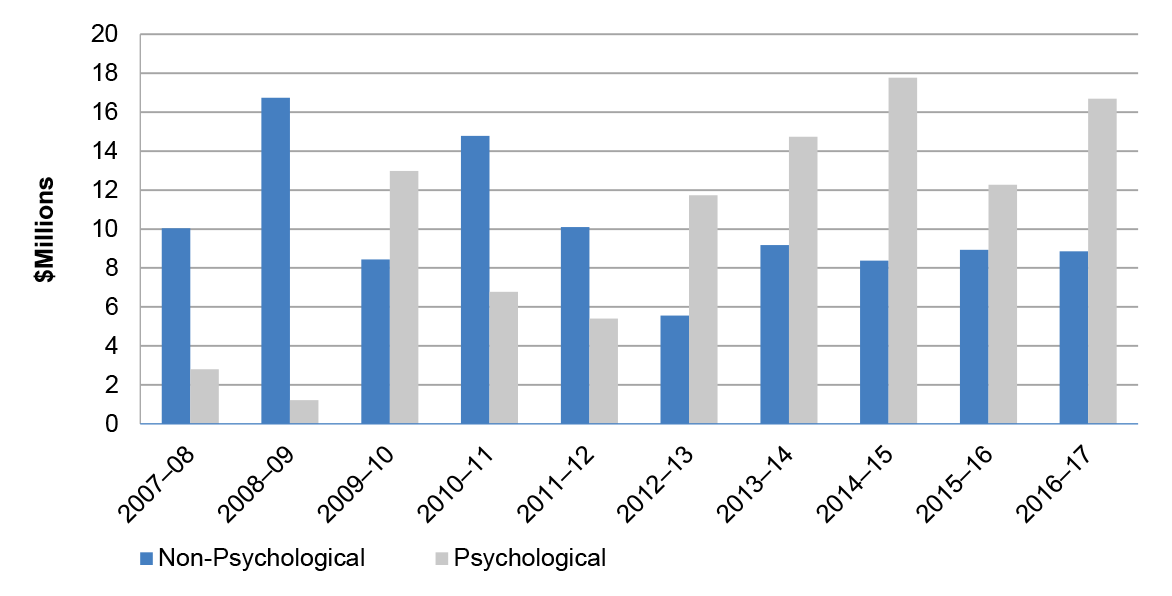

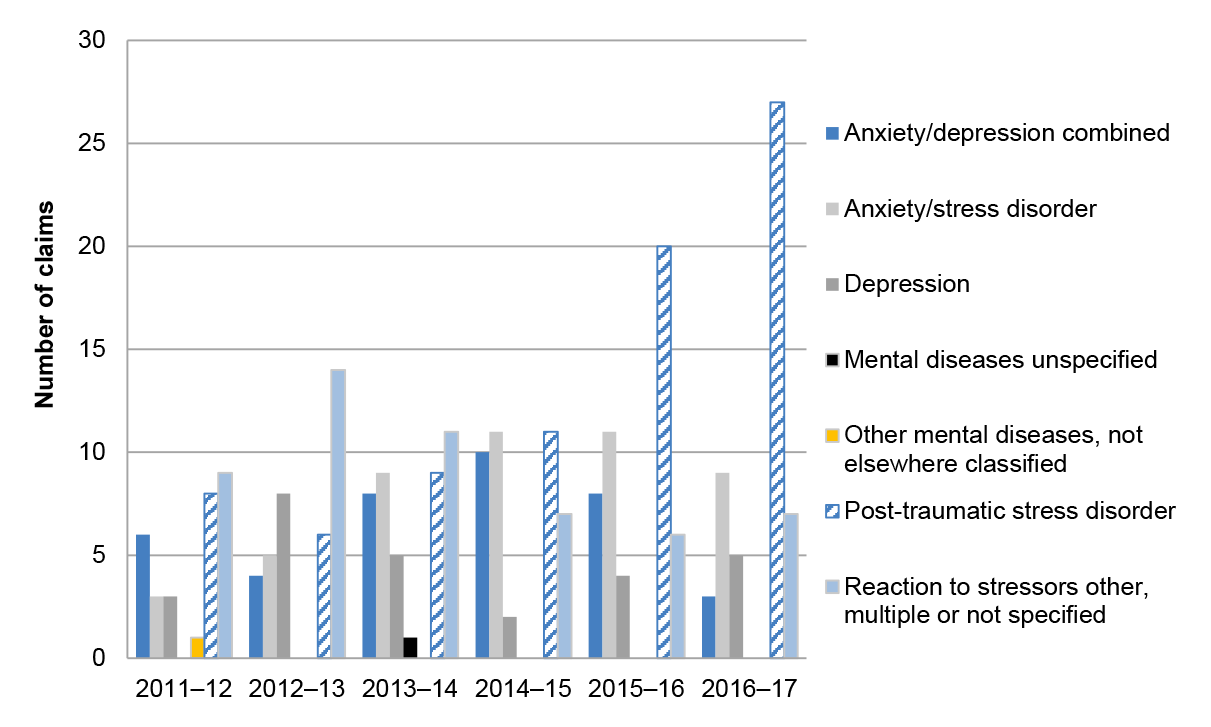

1.17 The AFP has experienced an increase in the number of Comcare claims for psychological injury, and in the costs claimed by employees that are related to psychological injury—as shown in Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3. In 2007–08 there were 11 AFP claims related to psychological injury that were approved by Comcare at a cost of $2.8 million. By 2016–17 this had increased to 35 claims approved with an associated cost of $16.7 million.14 Figure 1.3 illustrates the variability in claim costs between years.

Figure 1.2: AFP injury claims accepted by Comcare by injury type, 2007–17

Source: ANAO analysis of AFP Comcare data.

Figure 1.3: Total cost of AFP Comcare claims, 2007–17

Source: ANAO analysis of AFP Comcare data.

1.18 As the above Comcare data only includes accepted claims from AFP employees, it may not reflect the actual number of AFP employees experiencing psychological injury, or the associated costs to those employees. AFP employees not reporting psychological injury to Comcare may be a result of barriers to employees seeking help, as discussed in paragraph 3.25. The number of AFP employees that have or are seeking support externally to the AFP, or not seeking assistance at all, is unknown.

AFP reviews

Cultural change review

1.19 In August 2016 the AFP undertook a review, Cultural Change: Gender Diversity and Inclusion in the Australian Federal Police, which examined AFP culture and diversity. The scope of the review did not examine employee mental health, although some of the findings relate to employee mental health. The review findings included:

- a ‘trust deficit’ between members and leaders, particularly with senior leaders;

- the need for change to the AFP’s recruitment, promotion and training process to emphasise the importance of people management and leadership skills;

- noting that the majority of female employees interviewed feel they are not able to thrive equally with male colleagues;

- high level of female employees—46 per cent of female survey respondents—reporting experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace in the last five years—a result which is higher than the broader Australian workforce;

- a culture that makes reporting incidents, including sexual harassment, unsafe. In addition, internal integrity investigations can be protracted, which can be a disincentive for members to report incidents;

- poor performers not being appropriately managed;

- structural and cultural obstacles, including a strong stigma, that limit employees’ (all genders) ability to access flexible work arrangements; and

- three in five staff having experienced bullying in the workplace.

1.20 The AFP Commissioner has accepted all 24 recommendations in the report and committed to ensuring that each is implemented. The AFP has set out an implementation plan, and is regularly reporting on progress. As at July 2017, 8 recommendations had been implemented, with the remainder pending or in progress.

AFP activities to improve employee mental health

1.21 In February 2017, AFP Commissioner Colvin noted that it is ‘widely acknowledged that police are at a higher risk of trauma-caused mental injury than almost any other profession’ and that the health and wellbeing of AFP staff is of the highest priority.15 In recognising that it faces a significant challenge in managing the mental health of its employees, the AFP has commenced a range of activities intended to improve how it supports employee health and wellbeing. In September 2016, the AFP began developing a draft Mental Health Framework and associated Mental Health Strategic Action Plan based on Beyond Blue’s Good practice framework for mental health and wellbeing in first responder organisations.

1.22 To inform the design of the Framework and Strategic Action Plan, in March 2017 the AFP engaged a contractor to review the quality and employee perceptions of its mental health support services.16 The review included an examination of the literature associated with mental health in policing; review of AFP documentation; face to face consultations with senior AFP leaders; focus groups with AFP employees and an online survey seeking AFP employees’ views of support services, with the report not yet completed at the time of drafting this audit.17 Finalisation of the framework and associated action plan is pending the outcome of this review; as such the AFP executive has not been in a position to consider its approval and implementation.

1.23 In February 2017, the AFP established a Mental Health Strategy Board intended to ‘direct all aspects of the AFP Mental Health Strategy including an independent review’ and to ‘oversight the implementation of the review recommendations’.18

1.24 In June 2017, the AFP commenced an informal pilot project to track employee exposure to critical or potentially traumatic incidents. The project involved AFP’s Organisational Performance and Organisational Health areas. The project was prompted by academic research indicating that cumulative exposure to traumatic events increases the risk of psychological injury, with rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and depression increasing with each additional traumatic exposure. AFP employees conducted an exercise to combine data from its policing case management system with time charging records to see how many hours AFP members are charging to particular types of cases, and attendance at critical incidents. The purpose was to use this information to improve the targeting and timeliness of intervention support to members who may be at risk from cumulative exposure to traumatic events and/or material.

1.25 Recognising the need for better identification of physical and mental health risks across the AFP, in mid-2017, the AFP’s Organisational Health area:

- seconded a staff member from the Strategic Risk section to develop Organisational Health’s capacity to assess needs for services; and

- commenced development of an informal pilot program to assess work stresses in a given operational area, in order to target future interventions. The pilot is taking place in the Forensics area, Telephone Intercept and ACT Policing areas, as these have been identified by AFP psychologists as potential high risk areas.

1.26 In July 2017, the AFP officially launched an expanded Welfare Officer Network (the network previously comprised two officers supporting ACT Policing employees). The network now comprises 22 Welfare Officers across the ACT, NSW, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia, Cairns and Brisbane. Services from Welfare Officers extend to Darwin, Geraldton, Exmouth and international posts.

1.27 In October 2017, the AFP made available a free wellbeing app, Equipt, for current and former AFP employees and their families. The app is a self-help tool to assist individuals with tracking their physical, emotional and social wellbeing.19 The AFP in partnership with the Australian Federal Police Association, have licenced the app from Victoria Police and The Police Association of Victoria, tailoring aspects to meet AFP needs.

Audit approach

1.28 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the AFP in managing the mental health of its employees. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Has the AFP implemented sound governance and risk management practices to manage employee mental health?

- Is the AFP effectively managing employee mental health throughout their career lifecycle?

- Are sound monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements in place to assess the effectiveness of the AFP’s management of mental health?

1.29 The scope of this audit is the management of employee mental health by the AFP. It addresses high-level management and coordination of programs explicitly supporting mental health. The ANAO did not evaluate or form conclusions against organisational stressors within the AFP. The ANAO did not review Comcare services or claims processes, as these are not directly within the control of the AFP.

1.30 The ANAO conducted this audit to contribute to work being undertaken in other audit jurisdictions relating to the mental health of first responders, including the Queensland Audit Office, and the Audit Office of New South Wales.20 The Office of the Auditor-General of Canada was also conducting work in this area. The selection of this audit also reflects the significant risks and costs faced by the AFP in managing employee mental health, as evidenced by increasing rates of Comcare psychological injury claims in recent years.

1.31 In conducting this audit, the ANAO reviewed AFP documentation, interviewed key AFP personnel and relevant stakeholders at AFP national headquarters in Canberra and regional AFP sites in Adelaide, Alice Springs, Darwin, Melbourne, and Sydney. The audit team conducted 102 interviews with AFP personnel and received 66 public submissions to the audit.

1.32 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards, at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $705,268.00.

1.33 The team members for this audit were Anna Peterson, Jess Scully, Lachlan Fraser, Jerry Liao and Paul Bryant.

2. Governance and risk management

Areas examined

The ANAO assessed the AFP’s governance arrangements for managing employee mental health, and its management of mental health risks.

Conclusion

While currently developing a mental health framework, the AFP has not established a clear governance structure for decision-making, information sharing and oversight in relation to employee mental health arrangements. Reporting into the governance structure is not comprehensive or risk-based, making it difficult to identify emerging mental health related risks and to utilise this reporting to inform decision making in resource prioritisation to address increasing mental health risks.

The AFP formally included mental health as a strategic risk to the organisation in October 2016, however this risk identification has not led to substantive engagement and coordinated identification of mental health risks faced by all of the AFP’s functional areas.

The AFP does not currently have in place mechanisms or sufficient data to appropriately align resources with key mental health risks.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving AFP’s strategic and governance arrangements for managing employee mental health, as well as for enhancing its management of mental health risks.

Does the AFP have an organisational health and wellbeing strategy in place that incorporates mental health?

The AFP does not have in place an organisational health and wellbeing strategy which incorporates policies, programs and practices to address mental health risks. The AFP is developing a draft Mental Health Framework and Mental Health Strategic Action Plan, and finalisation of these is dependent upon the outcome of a review of AFP mental health services that was not yet finalised at the time of drafting this report.

Draft Mental Health Framework and Strategic Action Plan

2.1 In September 2016 the AFP developed a draft Mental Health Framework and associated Mental Health Strategic Action Plan based on Beyond Blue’s Good practice framework for mental health and wellbeing in first responder organisations. The purpose of the draft framework was to ‘reset the direction in the AFP for mental health’, and the action plan outlined initiatives intended to strengthen the AFP’s commitment to mental health.

2.2 The draft framework and action plan were presented to the AFP’s Executive Leadership Committee on 13 September 2016. The documents were discussed but not approved, with the rationale for this decision not clear from the meeting minutes.

2.3 In March 2017 the AFP commenced a review of the quality and perceptions of its mental health support services. The review included an examination of the literature associated with mental health in policing; review of AFP documentation; face-to-face consultations with senior AFP leaders; focus groups with AFP employees and an online survey seeking AFP employees’ views of support services.21 Once finalised, the review will inform the design of the draft framework and action plan. In revising the framework and action plan, the AFP should consider how these documents could fit within an overarching organisational health and wellbeing strategy (as discussed below).

2.4 In September 2017, the AFP provided a status update to the ANAO regarding progress against each of the activities listed in the draft plan. However, as the framework and plan have not yet been finalised or approved—pending the outcome of the review, this progress reporting is not currently being monitored or reviewed through any formal mechanisms.

Organisational health and wellbeing strategy

2.5 The AFP does not have in place a formal organisational health and wellbeing strategy, which incorporates policies, programs and practices to address the AFP’s mental health risks.

2.6 In early 2017, the AFP developed a draft concept paper called ‘Road2Ready – Physical Health Concept Paper 2017 – 2020’. This concept paper proposes an ‘AFP physical health model’ and acknowledges the interaction of physical, psychological and community health. However, the paper is primarily focused on physical health and has limited information on psychological health or broader elements of organisational health. Although the paper does reference the mental health framework, it is unclear how the draft mental health framework and the ‘Road2Ready’ concept paper are linked.

2.7 The AFP would benefit from developing a strategy which recognises that mental health is a component of overall employee wellbeing, and that mental health is impacted by a range of factors including organisational climate, physical health and personal circumstances. The strategy should capture the reforms and activities already underway to ensure that desired improvements to employee wellbeing are achieved over the long term.

Are clear governance arrangements in place to manage responsibilities in relation to mental health?

The AFP has defined the roles and responsibilities of individual employees and managers at different organisational levels for supporting employee mental health. However, the AFP has not established a clear governance structure for decision-making, information sharing and oversight in relation to employee mental health arrangements. This includes both organisational and committee arrangements.

Responsibilities

2.8 The AFP is required to protect workers and other persons against harm to their health, safety and welfare through the elimination or minimisation of risks arising in the course of their employment under the Workplace Health and Safety Act 2011 (WHS Act).

2.9 The AFP has guidelines in place that articulate the roles and responsibilities of workers, managers, team leaders and coordinators in relation to supporting the physical and psychological health of employees. Examples include the National Guideline on AFP Health and Safety Management Arrangements.

Governance arrangements

Organisational level

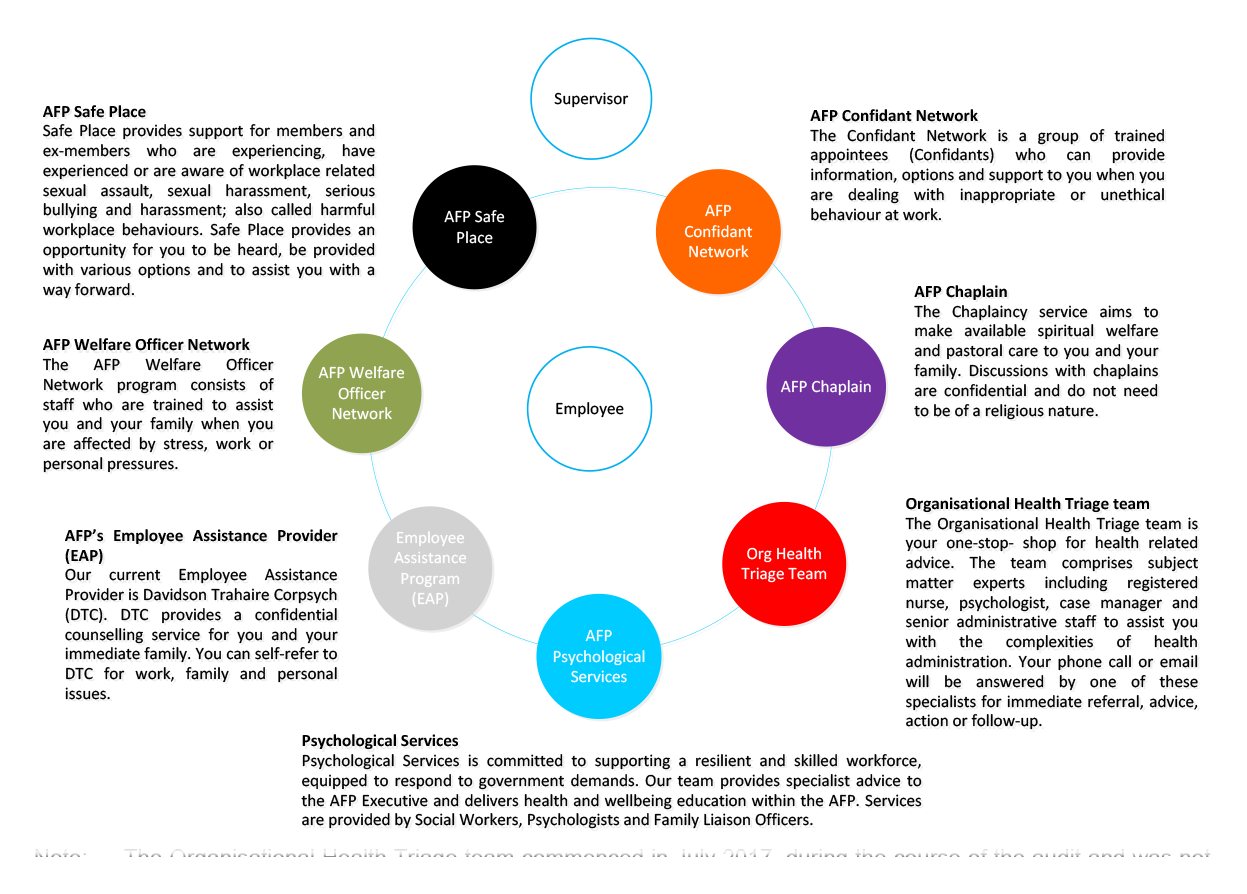

2.10 There are a number of distinct teams that contribute to the AFP’s management of employee wellbeing and mental health. As discussed in Chapter 4 and outlined in Figure 2.1, these include Psychological Services, the Welfare Officer Network, Employee Assistance Program, Chaplaincy, Safe Place, the Confidant Network and the recently established (in August 2017) Organisational Health Triage team.

Figure 2.1: Organisational structure for the management of employee wellbeing and mental health

Source: ANAO analysis of AFP documentation.

2.11 As outlined in Figure 2.1, many of the health and wellbeing components are managed by Organisational Health and the Chief Medical Officer, under the National Manager People Safety and Security, while Safe Place and the Confidant Network are managed by the National Manager Reform, Culture and Standards who reports directly to the Commissioner. There is no formalised governance mechanism in place to support co-ordination, information sharing and reporting between the two interrelated business areas. Having two separate business areas that focus on employee wellbeing and mental health may reduce the ability to co-ordinate the AFP’s activities to address employee wellbeing, including mental health, but also to identify employees at risk. There would be benefit in the AFP reviewing the organisational structure and co-ordination of these business areas.

Committee level

2.12 The AFP’s governance structure is characterised by a range of committees at the national and regional level. The committees with functions relevant to organisational and mental health are outlined in Appendix 2. The ANAO’s analysis of these committees’ Terms of Reference, meeting minutes and agenda papers between August 2016 and September 2017 found that their decision-making responsibilities and reporting arrangements in relation to employee mental health and wellbeing have not been clearly documented.

2.13 The ANAO’s analysis found that it is not clear which committee has the primary responsibility for the governance of employee mental health and wellbeing. The AFP advised that the National Safety Committee (NSC) has oversight of all employee health matters under WHS legislation. The committee Terms of Reference do not mention employee mental health or wellbeing.22 The committee focuses on reviewing reported work health and safety incident statistics, compensation claim statistics and physical injury risks presented by operational equipment. While there is some discussion of mental health matters, these are not undertaken in line with a long-term perspective and established priorities for action.

2.14 The AFP also advised that Regional Safety Committees (RSCs) report to the NSC. There was no evidence from the agenda papers or minutes that the NSC considered matters raised at RSCs.

2.15 Review of committee agenda papers and minutes further identified that there is no committee which receives a complete reporting picture on employee mental health matters, and that reporting on the performance of support services is not consistently shared between the committees.

2.16 The Functional and Efficiency Review of the AFP, finalised in November 2016, identified similar concerns in relation to the AFP’s governance and committee arrangements, in particular with the clarity of committee accountabilities, responsibilities and discipline. The AFP is currently preparing a fully costed response to the review for government consideration by the end of 2017.

2.17 An internal review of the AFP’s committee structure is currently underway but has not yet been finalised. As part of the broader review, the AFP should incorporate opportunities to improve its governance arrangements for organisational health including employee mental health and wellbeing.

Functional and Geographic level

2.18 AFP functional areas and regional offices hold responsibilities for the physical and psychological health of AFP employees.

2.19 AFP functional areas, such as Counter Terrorism or Protection Operations, are led by a National Manager (SES Band 2) who, along with the AFP Commissioner and Deputy Commissioners, are considered to be Officers (Senior Executive) under the WHS Act 2011. Officers are required to take reasonable steps to gain an understanding of the hazards and risks associated with the business and ensure that the business has and uses appropriate resources and processes to eliminate or minimise risks to health and safety (that is both risks to physical and psychological health).

2.20 Regional offices are run by State Managers (SES Band 1). Under the WHS Act 2011, Managers are considered to be Workplace Supervisors and are similarly required to eliminate health and safety risks from the workplace, and where this is not reasonably practicable, take all reasonably practicable steps to effectively minimise the risks.

Recommendation no.1

2.21 The AFP develop a comprehensive organisational health and wellbeing strategy and governance arrangements based on an integrated approach to staff mental health and wellbeing which incorporates policies, programs and practices that address the AFP’s specific risk profile.

Entity response: Agreed.

2.22 I [AFP Commissioner] wish to highlight the progress AFP had made prior to the commencement of the 2017 audit. In 2016, we developed a Mental Health Strategy and engaged Phoenix Australia to undertake a review of mental health in AFP. Concurrently, KPMG was engaged to conduct a review of the AFP governance framework. The formal engagement of Phoenix Australia predates this audit and demonstrates my commitment to mental health reform.

2.23 The AFP will finalise the mental health strategy and associated policies, programs and practices incorporating the relevant recommendations of the Phoenix Australia review, lessons drawn from other policing and first responder agencies both nationally and internationally and this audit.

2.24 We acknowledge that the current governance arrangements are complex and do not clearly identify lines of accountabilities in the area of mental wellness. KPMG was engaged in 2017 to conduct a review of the AFP governance framework and this review will inform the mental health strategy to ensure clear lines of accountability.

Does the AFP identify, assess and prioritise key risks relating to mental health?

The AFP formally recognised mental health as a strategic risk to the organisation and began developing treatment actions in October 2016. This strategic risk identification has not led to substantive engagement by all functional areas. Employee mental health has not been consistently identified as a risk in the AFP’s functional risk assessments and it is not evident that the AFP is co-ordinating the management of mental health as a shared risk (that is, between Organisational Health and functional areas).

Risk management framework

2.25 The AFP’s risk management framework comprises four levels of assessment: entity; functional; program; and specific operations. The Enterprise Risk Profile outlines the AFP’s risk exposure at an entity level, with four categories of strategic risk identified.23 Each functional and program area is to undertake a risk assessment and develop a risk assessment and treatment plan (risk register), based on the template provided as part of the guidance material. In line with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy the AFP has defined its risk appetite and tolerance, with risks rated above ‘medium’ expected to have a specific treatment plan in accordance with the AFP’s Risk Assessment Tool. The AFP targeted an ‘integrated’ level of risk management maturity in the Comcover Risk Management Benchmarking Survey 2017, and was assessed as meeting this standard based on its survey responses.

Identifying and monitoring mental health risks

Entity level

2.26 Risks to employee mental health were formally identified at an entity level in October 2016 following the increasing number and cost of accepted Comcare psychological injury claims and a growing Comcare premium.

2.27 As at August 2017, the AFP’s Enterprise Risk Profile identifies mental health injury as one of 22 entity level risks.24 Risk controls have been documented, and further treatments are proposed. The identified treatments primarily involve changes to the delivery of training and support networks, and the integration of organisational and mental health considerations in policies and processes. Despite the risk of mental health injury being considered ‘High’, only two of the planned risk treatments are expected to be implemented in 2017–18. Five of the nine identified treatments are not due until 2022.

Functional level

2.28 The entity level recognition of mental health is not consistently reflected in functional risk assessment and treatment plans. Comcare mental health injury claims data shows that of the 20 functional areas within the AFP, ACT Policing, Protection Operations, Specialist Operations, and International Operations were among the functional areas with the highest number and cost of compensation claims for mental health injuries. Despite this, these four functional areas did not specifically identify mental health as an area of risk in their risk assessment and treatment plans. Crime Operations, also identified as an area with a high number and cost of compensation claims for mental health injury, did identify staff mental health as a specific area of risk and had identified specific controls and treatments for this risk.

2.29 Where employee mental health has been identified as a concern within functional risk assessments, there remains scope to improve the specificity of controls and treatments.25 Examples were identified where the listed treatment control referenced existing procedures or policies, and did not clearly illustrate how the control mitigated the identified risk. For example, existing controls identified in the risk assessment for Organised Crime and Cyber include ‘adhere to AFP Reform – Safe Place Initiative … Adhere to policy and procedures’.26 On the positive side, many new treatments identified were more specific and listed actions or interventions with clear correlations to the mitigation of the identified risk. For example, Crime Operations identified the risk that exposure to certain work types could have negative mental health impacts, and proposed assessments for exposed staff and the introduction of software and systems to limit staff exposure. The AFP is not assessing whether the functional risk plans are being implemented, and whether identified mitigations are effective.

2.30 Further, there is a lack of clarity as to which aspects of risk treatments the functional areas are responsible for. For example, ACT Policing’s risk treatment plan for risks to employee physical and mental health states that ‘Risk Treatment initiatives being undertaken through enterprise wide Organisational Health projects […] will contribute to covering this risk for ACTP’, but does not specify how the initiatives that will specifically reduce ACT Policing’s risks.27

Organisational Health’s management of mental health risk

2.31 The ANAO’s review of AFP functional risk assessments identified that engagement with the Organisational Health team does not appear to have been formally prioritised in the functional areas of greatest risk within the AFP. Organisational Health has recognised the need for better identification of physical and mental health risks across the AFP. To achieve this, the Organisational Health area:

- has seconded a staff member from the AFP’s Strategic Risk section to develop the section’s capacity to assess needs for services; and

- is developing an informal pilot program to assess work stresses in a given operational area, in order to target future interventions. The pilot is taking place in the Forensics, Telephone Intercept and ACT Policing areas, as these has been identified by AFP psychologists as a potential high risk areas.

Does the AFP have an effective framework to align resources with key mental health risks?

The AFP does not have arrangements to ensure resources and funding are aligned to key mental health risks.

AFP allocates centralised funding to the Organisational Health function to resource mental health support activities. Each functional / geographical area may choose to allocate a portion of its annual operating budget to employee mental health but there is no information or assurance that funding is being spent in line with risk.

2.32 AFP provides centralised funding through a reccurring allocation to the Organisational Health function in order to resource core activities related to employee mental health across the AFP.

2.33 Separately, each functional or geographical area is allocated an annual operating budget, and each area is then responsible for determining what proportion of this funding to allocate to employee mental health at the operational level. No specific funding amounts are allocated for functional or geographical areas to spend on employee mental health. There is no available information on the extent to which each functional / geographical area allocates any of its annual operating budget to employee mental health. There is no assurance that appropriate funding is spent on employee mental health in functional / geographical areas and prioritised in alignment with the areas’ different mental health related risk profiles.

Recommendation no.2

2.34 The AFP analyse, define and report on mental health risks across the organisation in a consistent manner and develop arrangements to align employee mental health and wellbeing resources to areas assessed as highest risk. During this process the AFP should also assess the effectiveness of the existing controls and treatments used to mitigate mental health risks.

Entity response: Agreed.

2.35 The AFP continues to strengthen its governance and risk framework following the KPMG review of governance. I [AFP Commissioner] am committed to better management of mental health as a strategic risk and will adopt a risk-based approach to the delivery of services.

2.36 We continue to refine the mental health services, support and policies for our employees and I am committed to enhancing that support further to counter new and emerging mental health challenges. The development of the Mental Health Strategy and the engagement of Phoenix Australia to undertake a review of mental health in AFP assist me to realise my commitment to my workforce and to their safety and wellbeing.

3. Prevention, identification and return to work of psychological injury

Areas examined

This chapter assesses the effectiveness of the AFP’s arrangements for preventing and identifying psychological injury among employees through an examination of employment screening processes, mental health prevention and identification activities, and return to work processes for employees who have experienced a psychological injury.

Conclusion

Screening processes are in place to assess the suitability of employees’ psychological readiness for sworn roles. These are undertaken consistently as part of the recruitment process into the AFP. Required screening processes are not always taking place prior to an existing employee commencing in a high risk / specialist role with the AFP. Therefore the AFP is not provided with the assurance that all employees in these roles have been assessed as suitable for high risk roles.

Individual training courses have been developed by the Psychological Services team in response to operational requests in specific areas, however the AFP does not have a specific mental health training framework that identifies the competencies and resilience levels required by employees at different stages in their AFP career to inform delivery and prioritisation of training.

Current mechanisms used for identifying employees at risk of psychological injury are limited in effectiveness and do not occur routinely.

There are weaknesses with the AFP’s rehabilitation and return to work arrangements for employees suffering from a psychological injury sustained during their employment with the AFP. These relate to the lack of mental-health specific rehabilitation policies, procedures and training.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving mental health training for AFP employees and developing processes for providing assurance that mandatory psychological clearances, mental health assessments and psychological debriefs are undertaken in a timely manner.

The ANAO also suggests that the AFP monitor the long-term exposure of its employees and implement workforce planning for specialist roles. Additionally, the ANAO suggests that the AFP work closely with other policing jurisdictions to identify mechanisms for ongoing monitoring of the psychological health of general duties officers.

Does the AFP have effective and integrated employment screening for mental health?

The AFP has established employment screening processes for mental health but these are not fully effective. The AFP has in place structures for undertaking assessments to ensure that employees possess the physical and psychological competencies required for AFP work. ANAO analysis indicates that required psychological assessments are being undertaken consistently at the pre-employment stage, however are not being undertaken in all instances prior to internal staff movements into specialist roles with higher mental health risk profiles.

3.1 All AFP employees are required to possess and maintain a standard of health, wellbeing and physical fitness that enables them to fulfil their job requirements competently and safely. The Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth)28 enables the AFP to establish various conditions and competency requirements for employment, including: a medical assessment, a physical competency assessment and a psychological assessment.

3.2 The ANAO’s examination focused on the psychological assessment element of the employment screening process, which aims to assess an employees’ psychological readiness for policing roles.

Psychological assessments / clearances

3.3 The AFP National Guideline on medical, psychological and physical competency assessments requires that psychological assessments (also known as psychological clearances) must be conducted:

- prior to an applicant joining the AFP (pre-employment); and

- prior to an AFP employee being assigned to designated specialist operational roles, and designated non-operational support roles (an internal clearance).29

3.4 The nature of the psychological assessment varies depending on whether it is for pre-employment or as part of an internal clearance to a specialist role:

- For all recruitment in relation to sworn positions—candidates who are found suitable at the AFP Assessment Centre proceed to a psychological assessment. This assessment consists of two, short psychometric tests and a face-to-face interview with a psychologist from an external Health Provider. All candidates must undertake this psychological assessment and be assessed as suitable prior to being offered a new recruit role. This arrangement has been in place since 2009.

- For recruitment in relation to non-sworn / professional positions—there is no psychological assessment process for external applicants for non-sworn / professional positions. Once a non-sworn employee has joined the AFP, if they wish to transfer to certain specialist roles, they go through the process for an internal psychological clearance (see below).

3.5 For an internal clearance to transfer to certain specialist roles (see Box 1 below)—AFP Recruitment or the AFP Business Area advises the Psychological Services team that a psychological clearance is required. An initial check is undertaken by Psychological Services of the employee’s psychological data stored in the Clearance database, the PLANES database, Comcare’s Customer Information System (CIS) and on hard copy files.30 The employee is then required to complete a Psychological Services Assessment Form31 which is reviewed by Psychological Services and an assessment interview32 may be undertaken.

3.6 For certain specialist roles such as child protection there is an additional online test33, a face-to-face assessment interview by an AFP registered psychologist (which is mandatory) and graduated exposure to explicit materials. There is a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) on Graduated Exposure to Child Exploitation Material.

3.7 The clearance process for Child Protection Operation (CPO) members, including the Joint Anti-Child Exploitation Taskforce (JACET), has three steps. The employee may choose to withdraw from the process at any point:

- Step 1: Organisational Health clears the employee to commence the graduated exposure exercise. A determination to proceed is made based on the results of the online tests, such as those outlined in paragraph 3.6, and a face-to-face interview with an AFP psychologist;

- Step 2: The business area commences part one of the graduated exposure program with the employee. This should be conducted by a senior or experienced member of the CPO team in the relevant office. The employee is debriefed by an AFP psychologist; and

- Step 3: The business area commences part two of the graduated exposure program with the employee. The employee is debriefed by an AFP psychologist and, if appropriate, has their clearance signed off. The AFP’s SOP states ‘everyone undergoes the graduated exposure exercise before they commence in child protection operations work. The member is not to be exposed to explicit material before they have been psychologically cleared or completed the graduated exposure exercise. Furthermore, the clearance has to have been received by the CPO member conducting the process in writing’.

|

Box 1: AFP business areas requiring a psychological assessment and clearance |

|

|

|

3.8 The ANAO’s analysis of the AFP’s PLANES database, which holds information on the use of psychological services and related consultations for AFP employees, showed that in 2016–17, Psychological Services undertook 530 psychological clearances. The majority were for employees working in International Operations (381), followed by ACT Policing (43), Specialist Operations (36) and Crime Operations (32).

3.9 Psychological assessment occurs consistently as part of the pre-employment recruitment process for sworn positions. However, psychological assessments are not occurring consistently for internal staff movements into specialist roles. ANAO analysis showed that 34 per cent (13 of 38) of current JACET employees34 did not have a recorded psychological clearance registered against their name in the PLANES database. The AFP reviewed the relevant files for those 13 employees and advised the current status of the clearances as follows:

- four employees had been cleared but due to practitioner oversight or system error, the clearance had not been recorded in PLANES;

- four employees had been cleared prior to establishment of PLANES and so there was no record in the database;

- one employee was not cleared to work in JACET but the business area did not accept the AFP psychologist’s recommendation;

- three employees had completed one or two of the clearance steps but had not had final sign off on their clearance from an AFP psychologist; and

- one employee withdrew from the clearance process after step 2 but it was not clear whether that individual was still working in JACET.

3.10 As recently as October 2017, the AFP Mental Health report made to the National Safety Committee, states that:

On several occasions Psychological Services have been requested to clear members after they have commenced in Child Protection Operations roles. This potentially places members at risk of exposure associated with this type. Psychological Services have reminded Coordinators of the importance of clearance prior to exposure.35

3.11 Further, in 2015 the AFP noted36 that there were identified instances where business areas, in trying to meet their outcomes, decided to progress with an individual for a task who had not cleared employment gateways. The minute paper states that the non-compliance arises for one of two primary reasons:

- insufficient lead time to clear selected staff prior to the requirement; and

- during the clearance process, delays occur because of follow-up Organisational Health activities.

3.12 The minute also notes that where deployment or internal recruitment has been made without appropriate clearance:

Getting the decision wrong can be very costly and impact on the AFP in many dimensions: reputation, costs to recover and remedy, Comcare premium, and negative employee confidence.37

3.13 The minute recommended that the governance arrangements for clearances be reinforced across AFP business areas, and that the mandatory requirement for medical and psychological clearances be met before postings, deployments, recruitments, training and secondments.

3.14 Non-compliance with the psychological clearance process reduces AFP business areas’ assurance that their employees can meet the psychological demands of certain specialist roles. Additionally, without conducting psychological assessments and undertaking adequate role preparation, the AFP may be exposing its employees to mental health risks38, impacting on the future health of its employees and may expose AFP to additional future Comcare claims.

Does the AFP have effective arrangements for preventing psychological injury, including through appropriate training?

The AFP has arrangements in place for preventing psychological injury but these are not fully effective as the AFP does not have a specific mental health training framework as a pre-emptive measure to improve employee resilience.

3.15 Psychological injury prevention involves understanding and minimising factors which heighten risk39, and enhancing factors40 which improve resistance.41 Psychological injury prevention can be undertaken through initiatives that target whole populations, such as all AFP employees, with the aim of promoting resilience in individuals or positively impacting on some aspect of the social environment. Alternatively, prevention can be undertaken through selective interventions that target people who have not yet acquired a psychological injury but who exhibit or are exposed to risk factors that may predispose them to injury in the future, such as AFP staff in specialist roles.42

3.16 The main universal prevention initiatives implemented by the AFP are the use of employment screening and psychological assessments discussed above. Such controls function to increase the likelihood that mentally fit employees are engaged by the organisation and perform specialist roles.

Mental health training

3.17 In addition to the employment screening arrangements outlined earlier, another key universal prevention activity is to undertake training to improve employee awareness and resilience. The 2016 NSW Government report Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy for First Responder Organisations in NSW notes that:

Mental health and resilience training should begin from the first stages of emergency work training and should initially provide mental health awareness training, help-seeking advice and evidence-based resilience training. Mental health training and promotion strategies should then progress as first responders move into different stages of their career, including strategies on transitioning into retirement.43

3.18 The 2016 Victorian Police Mental Health Review made the following recommendation:

Mental health literacy content should also be embedded and examinable as a mandatory component in all leadership development programs, especially sergeant and senior sergeant levels, as well as training in undertaking supportive conversations. Attendance at a minimum number of such programs (e.g., at least one per year) could be included in Professional and Development Assessments for accountability purposes.44

3.19 The purpose of mental health literacy programs are to, among other things, increase recognition of early warning signs; provide accurate information about mental health issues including risk and recovery prospects; detail the benefits of and encourage early help seeking behaviour; provide information about evidence-based treatment options; and clarify appropriate ways to engage with and support a person in the workplace who may be experiencing mental health-related difficulties.45

3.20 Currently, the extent of mental health training focussed on enhancing the mental health of AFP employees is limited to:

- the Psychological Services team delivering a Wellbeing Services course to the AFP College as part of recruit training. This training involves informing cadets of the AFP support services available; and

- if requested by a business area, Psychological Services can provide training to support specific operational requirements or as part of preparation for overseas deployment. The training delivered by Psychological Services is operationally focused and delivered as skills training, however, AFP advises that the purpose of the training is to minimise the risk of psychological harm to AFP employees. A series of 31 courses were developed and delivered between 2010 and 2017 on an ad-hoc basis. The AFP was unable to advise how many individuals attended these courses. Examples of training provided under this heading include mindfulness, stress management, self-care, vicarious trauma, interacting with people who are suicidal, exposure to explicit material and respectful workplaces.

3.21 The AFP does not have a specific mental health training framework aimed as a pre-emptive measure to improve employee resilience. Further, there is no mandated mental health literacy content in AFP leadership programs. Whilst the draft AFP Mental Health Strategic Action Plan 2016–2022 indicates that mental health training is to be prioritised into learning and development activities covering induction to exiting the organisation, this document has yet to be formally approved, and there is no evidence that the articulated measures have been put into practice.

Recommendation no.3

3.22 The AFP implement a mandatory mental health training framework for all AFP employees, tailored to the various capability requirements throughout their career lifecycle that provides information on identifying signs and symptoms of mental health injury (in self and others) as well as guidance on how to conduct meaningful conversations with staff and colleagues about their mental health.

Australian Federal Police response: Agreed.

3.23 In late 2017, the AFP endorsed the delivery of a suite of mental health first aid training across the whole of the AFP. The delivery of this training, across the organisation, will be a tailored package to ensure the right training is delivered at the right time. The AFP agrees that a mental health training framework must be developed to afford access to diverse and relevant training for all areas.

3.24 We have also delivered an Early Access program where all members of the AFP can seek financial assistance for work related injuries both physical and psychological. This early intervention program is designed to link with the early recognition of mental health injury in self and others.

Does the AFP have effective arrangements in place for identifying psychological injury?

The AFP relies on three key mechanisms for identifying employees at risk of psychological injury: employee self-reporting; supervisor observation; and mental health assessments and psychological debriefs following deployment. There are limitations that reduce the effectiveness of these mechanisms, specifically:

- cultural barriers that reduce the likelihood of AFP employees self-reporting psychological injury;

- limited training and support for supervisors in identifying and supporting employees at risk of psychological injury; and

- inconsistent delivery and tracking of mandatory mental health assessments and psychological debriefs.

3.25 Whilst all AFP employees have a responsibility under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (WHS Act 2011) to report any negative psychological experiences to their Supervisor or Psychological Services, and to engage in actions to limit further harm, self-reporting is a mechanism of limited effectiveness. Interviews with AFP personnel noted that there are a number of barriers to self-reporting, such as the perception that firearms will be removed (resulting in reduced remunerative allowances and financial distress), or the perception of risk to career prospects. Results from the draft 2017 AFP Mental Health Review noted that the top three barriers to seeking support for mental health concerns were:

- putting one’s career at risk (32 per cent rated as a definite concern);

- fears that confidentiality will not be respected (31 per cent rated as a definite concern); and

- concerns that people will have less confidence in me (24 per cent rated as a definite concern).

3.26 In the AFP Strategic Leadership Group’s October 2016 meeting it was reported that stigma associated with mental illness, and a culture where employees with psychological injury have been referred to as ‘broken biscuits’, reduces the likelihood of employees seeking treatment.

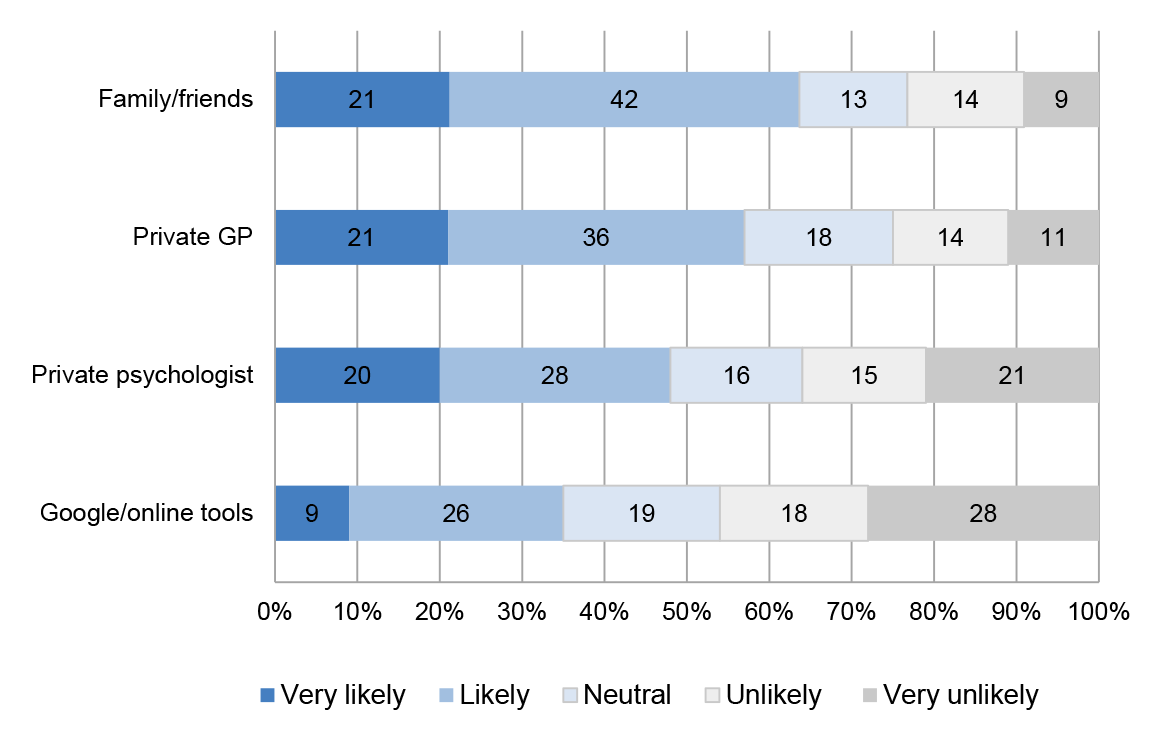

3.27 The AFP’s other two mechanisms for identifying psychological injury are through:

- Supervisors—who may request a psychological assessment of an employee who they consider to be at risk. Supervisors are expected to continue to support the employee, however, as previously noted, supervisors do not receive any training on how to recognise or support employees at risk of psychological injury. In addition, as discussed in Figure 4.3, 76 per cent of AFP employees stated they were unlikely to seek support from their supervisor or manager; and

- Psychological Services—mental health professionals identify psychological injury through mandatory mental health assessments undertaken of employees in specialist roles (or who are exposed to explicit materials) and/or in the debriefing process following overseas deployments (discussed below).

Exposure to explicit material and mandatory mental health assessments

3.28 The AFP recognises that exposure to explicit material is a psychological health and safety workplace hazard. As such, under the WHS Act 2011, the AFP has an obligation to manage the potential psychological health impacts of exposure to such material. The 2017 AFP Handbook: Managing the Psychological Health Impact on Staff from Explicit Material46 (the Handbook) sets out the AFP policy and protocol for business areas to identify the risks and mitigation strategies for managing the potential psychological and health impacts from staff dealing with explicit material. The Handbook recognises however that the risks associated with exposure to explicit material cannot be fully mitigated.

3.29 The Handbook requires that employees working with explicit material should be cleared through a psychological assessment, including graduated exposure to materials, before undertaking their role. The key mechanism to manage an employee’s risk of psychological injury once they are in the role is to undertake mandatory mental health assessments. As per AFP policy, mental health assessments are to be conducted annually (at a minimum). For those staff who have been in the role for less than two years, mental health assessments are supposed to occur annually, and a mental health assessment screening test takes place at the six month point between annual mental health assessments. If there is a need for early intervention from these screening tests, the policy is for a follow-up discussion with an AFP psychologist. Mental health assessments are also mandatory on exit or re-entry into the role. Unlike psychological clearances and debriefs (discussed below), Psychological Services has a role in instigating and monitoring the occurrence of mandatory mental health assessments.