Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Compliance with Fair Trading Obligations

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in managing compliance with fair trading obligations.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australians buy goods and services as part of their everyday activities—in 2014–15, Australian households consumed over $900 billion in goods and services.1

2. Consumers are provided with rights, and obligations imposed on traders, by the Australian Consumer Law. Responsibility for enforcing this legislation—and managing compliance with fair trading obligations—is shared between the federal and state and territory governments. The federal regulator responsible for managing compliance with fair trading obligations is the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

Audit objective and criteria

3. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in managing compliance with fair trading obligations.

4. To conclude against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- appropriate governance arrangements are in place to support the effective management of compliance with fair trading obligations;

- compliance risks are identified, and a strategy is in place to guide the ACCC’s fair trading regulatory activities;

- appropriate actions are taken to encourage voluntary compliance with fair trading obligations; and

- responses to non-compliance are timely, effective and proportionate to the risks presented by the non-compliance.

Conclusion

5. The ACCC effectively carries out many of its regulatory activities relating to managing compliance with fair trading obligations. It has a sound compliance and enforcement strategy, based on an extensive consultative process for determining strategic priorities. The strategy has been implemented by providing relevant and well targeted information and advice about fair trading rights and obligations to encourage voluntary compliance, and through proportionate and graduated responses to non-compliance, where investigations and enforcement activities have led to identifiable improvements in trader behaviour.

6. In the context of sound management, there are meaningful opportunities for the ACCC to improve its performance in managing compliance with fair trading obligations. Of particular importance, the ACCC has made inadequate use of intelligence for targeting compliance and enforcement activities, focuses too narrowly on individual complaints (rather than trends and patterns) in case selection activities and does not have adequate arrangements for ensuring that complaints involving high levels of widespread consumer detriment are considered by appropriate senior officers. Improvements in these areas would provide greater assurance that the ACCC is targeting its regulatory activities at conduct involving the greatest level of widespread consumer detriment. Doing more to extend its suite of performance measures from the current focus on outputs or deliverables to outcomes would also enable the ACCC to better gauge the extent to which fair trading objectives are being achieved and the extent of its contributions to higher levels of compliance by traders with fair trading obligations.

Supporting findings

Assessing regulatory risks

7. The ACCC’s arrangements for managing risks only partially accord with the Commonwealth’s Risk Management Policy, and the ACCC does not apply the policy to its priorities. While the annual strategic review process has been effective in identifying the ACCC’s key strategic compliance risks, these priorities have not been managed through a consistent risk-based approach, including arrangements for evaluating outcomes. Addressing these gaps would facilitate more consistent risk management across the ACCC.

8. The ACCC has a sound compliance and enforcement strategy that outlines a set of proportionate and graduated approaches to encouraging voluntary compliance and addressing non-compliance.

9. The ACCC has access to a wide range of information sources, which it uses to identify systemic compliance risks, target compliance activities and support investigations into non-compliance with fair trading obligations. However, in undertaking these activities the ACCC relies too heavily on its own complaints data, and could make greater use of other sources of information, including public data and the complaints data of other regulators (see Recommendation No. 1). In analysing information, the ACCC’s Intelligence and Reporting team prepares a range of useful reports for intelligence purposes. To support better targeting of compliance and enforcement activities, these reports could focus more on identifying higher risk traders, industries and issues.

10. In accordance with current Commonwealth guidance, the ACCC uses a number of measures, including performance indicators, case studies and survey results, to monitor and report on its performance. While they have improved over time, most of these measures are output-based, and developing measures of outcomes would enable the ACCC to report in ways that better illustrate its effectiveness in improving trader compliance with fair trading obligations.

Promoting voluntary compliance

11. The ACCC’s information and advice about fair trading rights and obligations is clear and targeted to the main areas of consumer and business concern. This information is disseminated through traditional channels and social media such as Facebook and Twitter. Of primary importance is the ACCC website, which is clearly organised and easy-to-use. Consumer and business stakeholders contacted by the ANAO consistently commented positively on the ACCC’s engagement with them.

12. The ACCC’s fair trading compliance projects, which generally contain elements of education and enforcement, are targeted to priority areas and often achieve good results. Of eight projects that it had evaluated, six had positive results and two had mixed results. However, more frequent evaluation and better risk management would provide greater assurance that these projects are well managed, effective and achieve value for money.

13. In the ACCC’s most recent Consumer and Small Business Perceptions Survey, most consumers and many businesses felt that they did not need to know what the ACCC was doing until there was a problem that affected them personally, at which time they expected to be able to find out more about the ACCC’s roles. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of respondents wanted to know more about the work of the ACCC, indicating scope for the ACCC to increase the awareness of consumers and traders about where to get advice about their fair trading rights and obligations.

Managing complaints

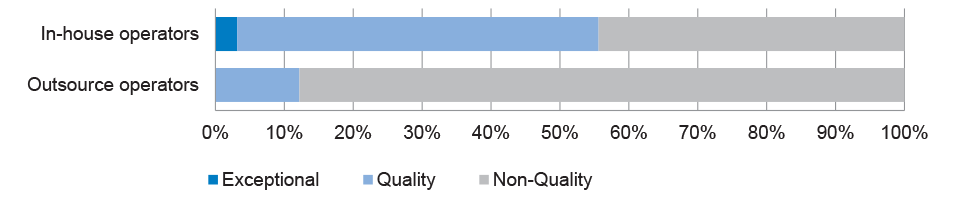

14. The ACCC does not have fully effective arrangements to receive and respond to complaints as it has not consistently met the service standards outlined in its Service Charter, and quality assurance checks indicate low levels of quality in answering calls. Only 48 per cent of recent calls were answered within 60 seconds (against a target of 60 per cent) and 56 per cent of web forms were responded to within the target of 15 business days.

15. There are also shortcomings in the ACCC’s quality assurance processes, as assessments have not been conducted in line with internal guidelines, outsource staff are subject to different call quality criteria to in-house staff, and results from the quality assessments are at odds with largely positive responses to the most recent customer service satisfaction survey.

16. The ACCC records complaints in its client relationship management systems. The ANAO identified issues with the way complaints were recorded in this system, including duplicate trader entries and a low level of identification of vulnerable and disadvantaged consumers. These issues reduce the usefulness of complaints data for the purposes of strategic planning, case selection and targeting of voluntary compliance activities. To increase the usefulness of complaints data for these purposes, the ACCC should introduce processes for assuring data quality, and better identifying vulnerable and disadvantaged consumers at the point of contact.

Case selection and escalation

17. The ACCC has appropriate arrangements for consideration and selection of matters at its internal case selection meetings. However, these meetings only consider approximately one per cent of the 10 000 fair trading complaints that the ACCC receives each quarter and there are limitations in the arrangements for escalating complaints beyond the Infocentre, which is the initial response centre for all inquiries and complaints to the ACCC on competition and consumer issues in Australia. These limitations relate to the extent of assurance arrangements regarding the escalation of cases to the case selection meetings, which raise the possibility that the ACCC may ‘miss’ complaints and consequently not address instances of widespread consumer detriment.

18. More broadly, the ACCC’s case selection activities focus too heavily on individual complaints and instances of non-compliance. Greater use of intelligence in the case selection process, aimed at identifying trends and patterns of conduct suggesting widespread consumer detriment, would enable the ACCC to more effectively target its investigative and enforcement activities.

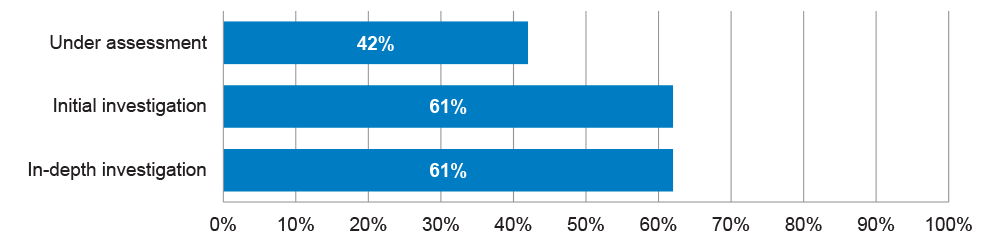

19. The ACCC’s processes for escalating cases for detailed investigation and enforcement action were effective in filtering cases to those falling within an ACCC priority. However, there were issues with the way that case progressions and escalations were recorded that have implications for the accuracy of reporting about the number of cases at various stages of investigation.

Managing investigations

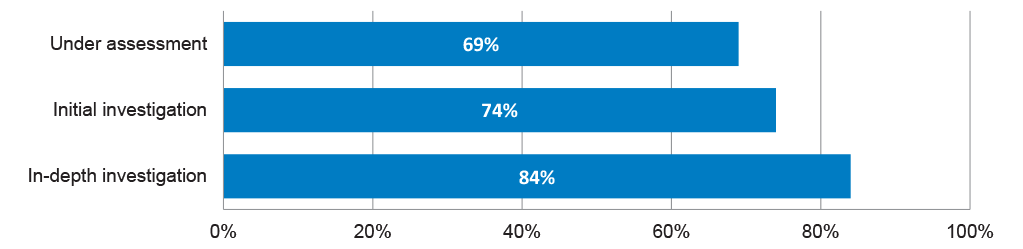

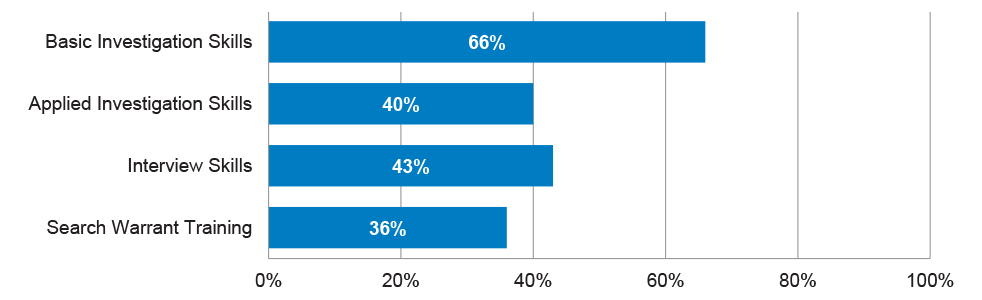

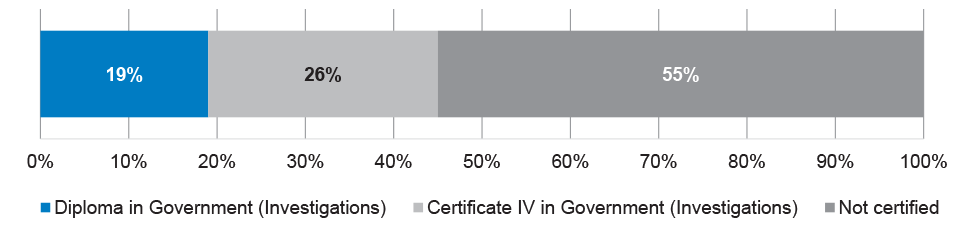

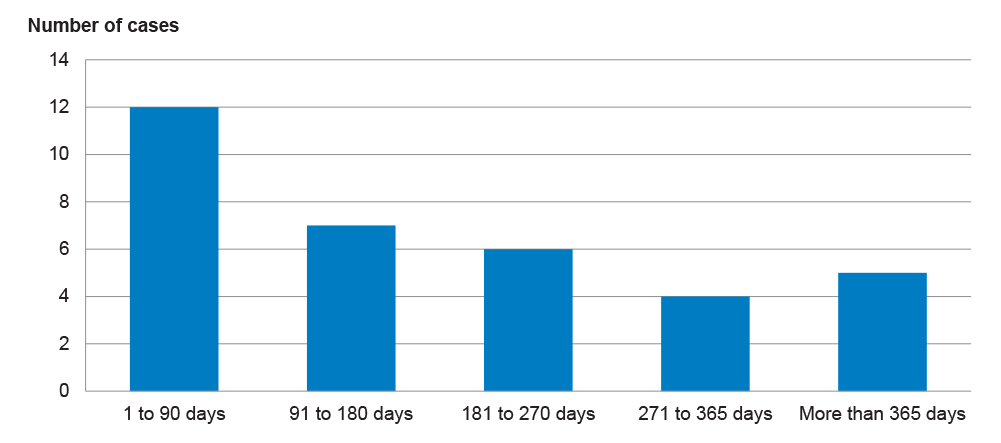

20. Investigations were largely carried out in accordance with the Australian Government Investigation Standards. The ACCC has clear policies on its intranet, well-qualified staff and effective arrangements for the oversight of investigations. There was room for the ACCC to improve its practices in relation to the planning of investigations, as no investigation plan was in place for 14 of 50 investigations reviewed (28 per cent) and risks were not appropriately identified as part of investigation planning.

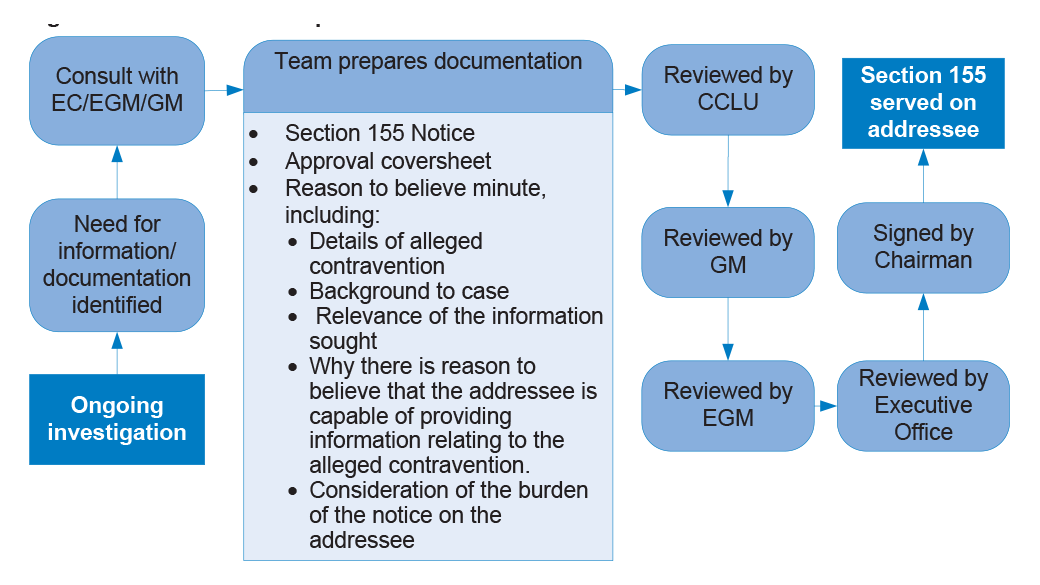

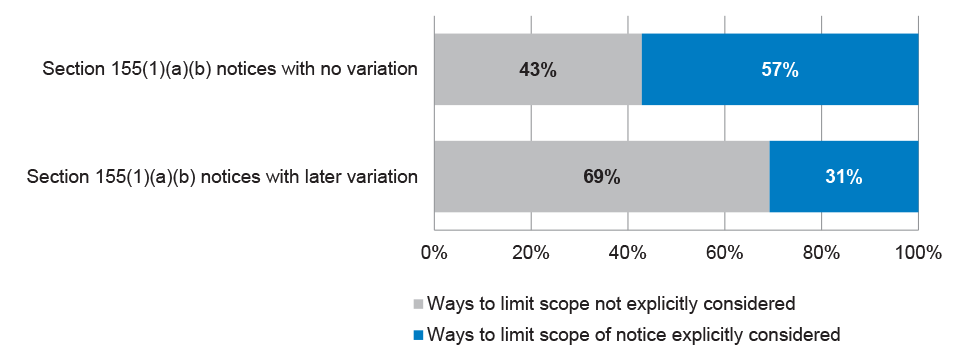

21. The ACCC has extensive processes to ensure that its investigative powers are used in a way that is proportionate to the risk presented by non-compliance, and also having regard to the burden and cost of compliance for a recipient. There was a high level of compliance with these processes and the ACCC exercised its powers in a proportionate way. However, there is room for the ACCC to ensure it more systematically considers ways to narrow the scope of information gathering notices that it issues.

Enforcement actions

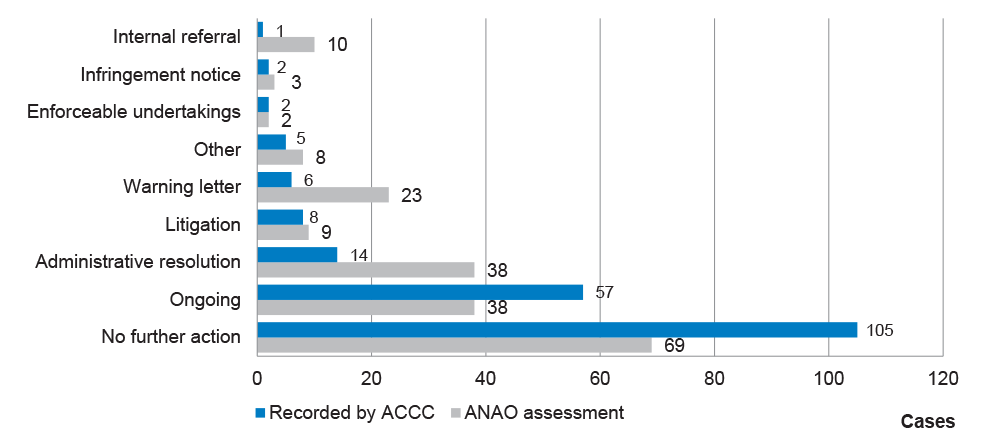

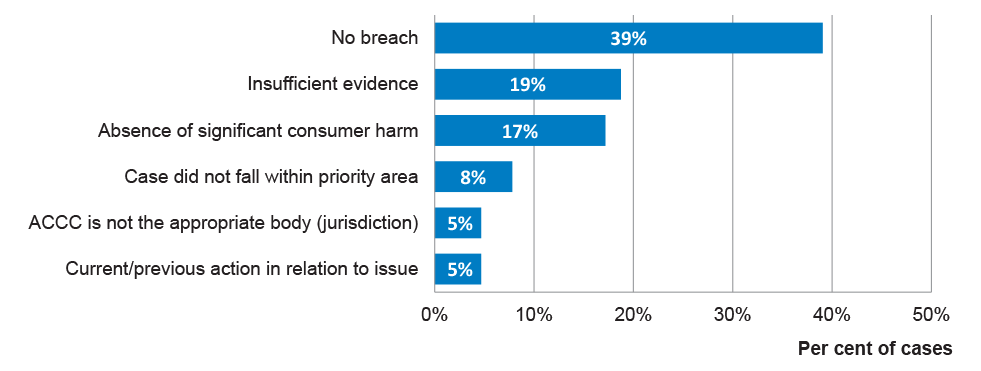

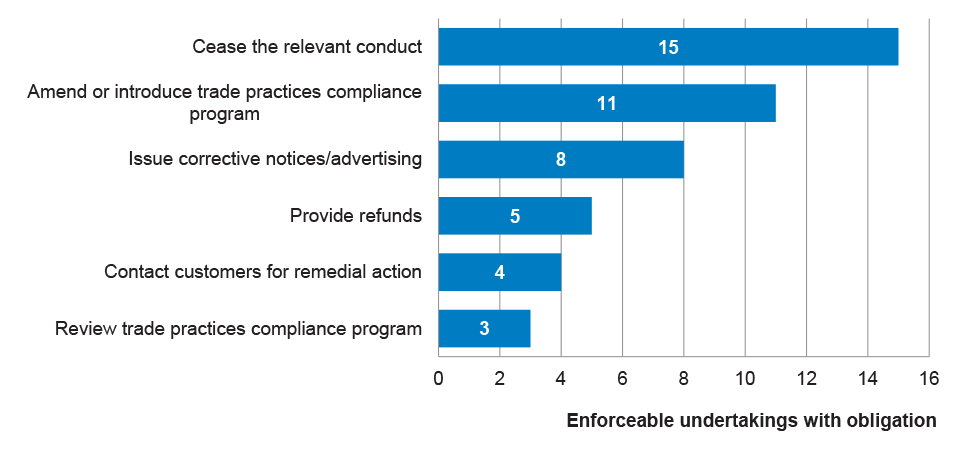

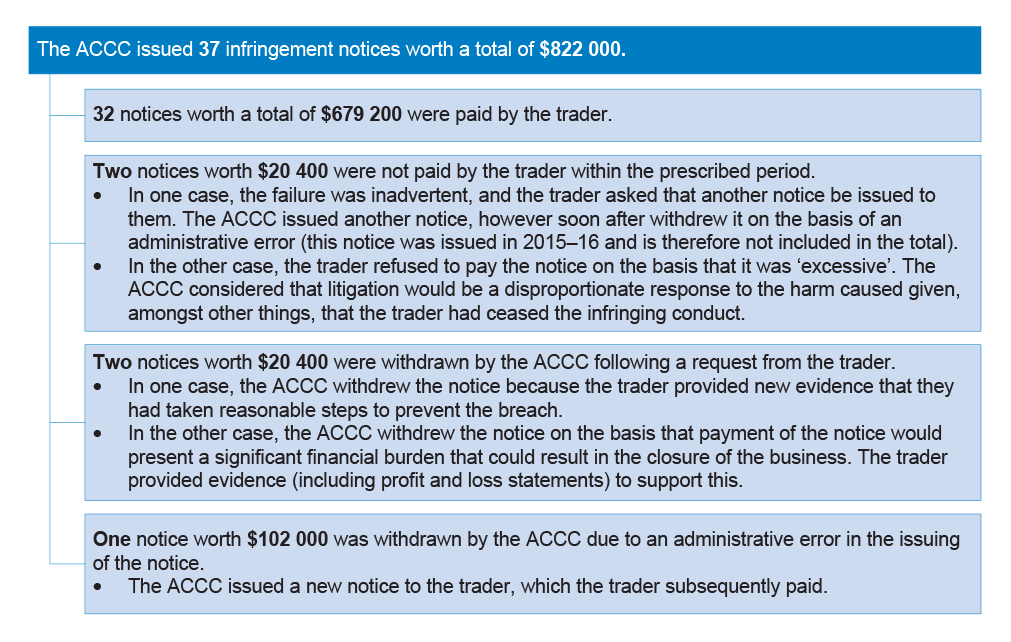

22. The ACCC consistently made decisions about the appropriate enforcement action in particular cases in accordance with its Compliance and Enforcement Policy, proportionate to the identified non-compliance, and having regard to the objectives of specific and general deterrence. The ACCC makes use of a range of actions to respond to non-compliance. The most common action taken by the ACCC was accepting an administrative resolution (23 per cent of finalised cases in the ANAO’s sample).

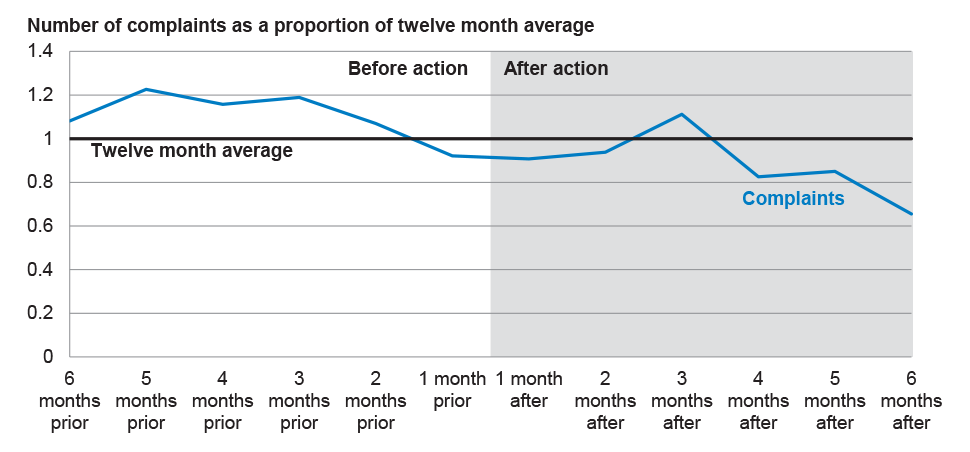

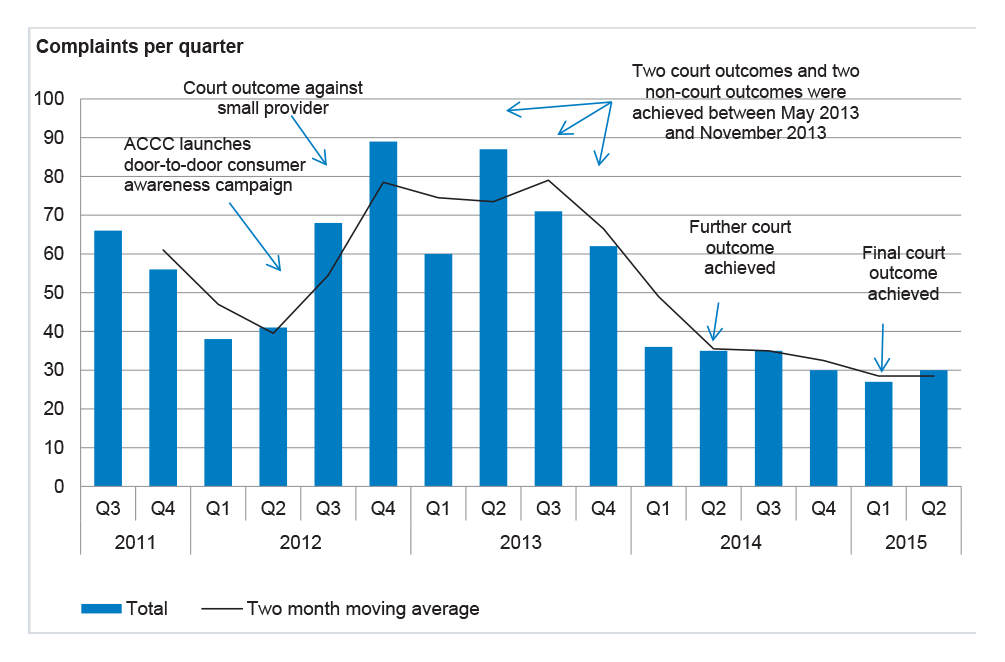

23. Enforcement actions taken by the ACCC were effective in responding to and managing non-compliance. The ANAO identified a decline in the number of complaints about a trader in the period following an action being taken against that trader, suggesting that enforcement actions were effective in achieving specific deterrence.

24. The effect in terms of general deterrence is more difficult to measure, although particularly where the ACCC adopted an industry-wide approach, it appeared that enforcement actions did have an impact on compliance in the broader industry.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.28 |

To improve the extent and usefulness of information obtained for intelligence purposes, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission examines the merit of regularly obtaining complaints data feeds from other Australian Consumer Law regulators. The ACCC’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.18 |

To better support the use of complaints from consumers as a source of intelligence for strategic planning and targeting of compliance and enforcement activities, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission improves the quality of complaints data, including by:

The ACCC’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 5.13 |

To improve the selection of cases for investigation and enforcement, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission:

The ACCC’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

25. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s summary response to the report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

The ACCC welcomes the report and its findings that the ACCC has a sound compliance and enforcement strategy.

The ACCC notes the ANAO’s comments that there are opportunities for the ACCC to improve its use and gathering of intelligence to provide greater assurance that the ACCC is targeting its regulatory activities at conduct involving the greatest level of widespread consumer detriment.

The ACCC agrees with the three recommendations made in the report, which focus on intelligence and improvement of quality of complaints data. The ACCC response notes recent, current and possible future actions that might address the recommendations.

Audit Findings

1. Background

Regulation of fair trading

1.1 The agency responsible for consumer protection at the national level is the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The ACCC is an independent agency within the Treasury portfolio, established in 1995 by the merger of the former Trade Practices Commission and Prices Surveillance Authority. The ACCC has three main responsibilities:

- promoting competition—by educating traders about their responsibilities, assessing proposed mergers as part of the merger review process and taking action against anti-competitive conduct;

- protecting consumers (and small businesses)—by educating consumers and traders about their rights and responsibilities, taking action against conduct that contravenes the fair trading obligations in the Australian Consumer Law and administering, in conjunction with state and territory agencies, product safety laws (state and territory consumer affairs agencies administer mirror legislation in their jurisdictions); and

- regulating national infrastructure markets—by determining the prices and access arrangements for some nationally significant infrastructure services (such as telecommunications, rail and bulk water).

The Australian Consumer Law

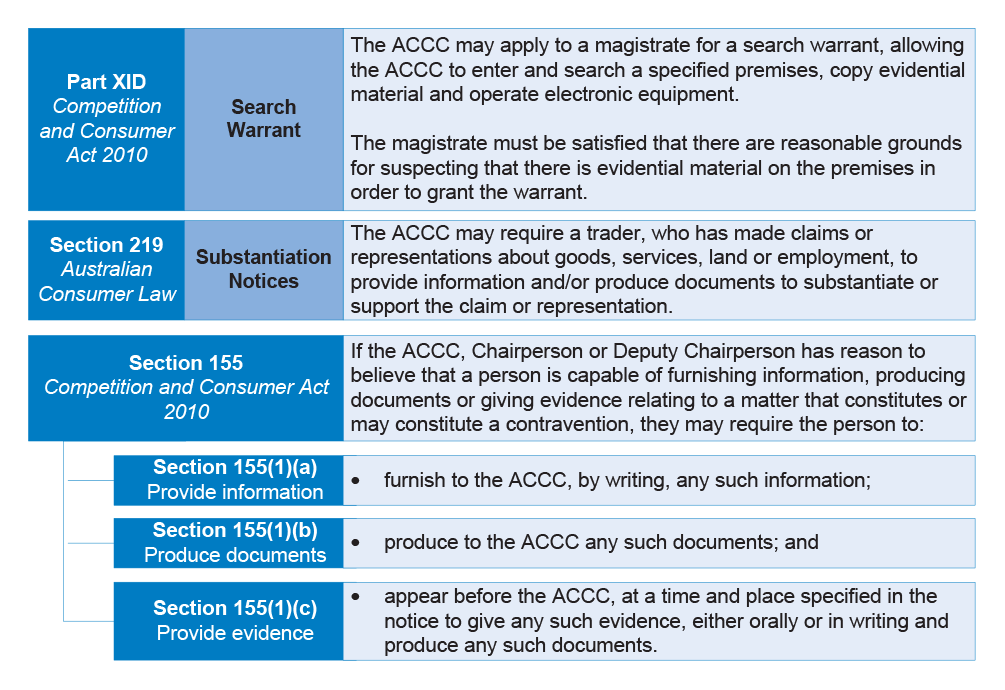

1.2 Australian consumers are provided with rights and obligations are imposed on businesses by the Australian Consumer Law. The Australian Consumer Law is enacted as Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010, and is a single, national law relating to consumer protection and fair trading. Key provisions of the Australian Consumer Law are shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Key provisions of the Australian Consumer Law

Note: The Australian Consumer Law does not cover the provision of financial products and services. Consumer protection in relation to these matters is dealt with by identical provisions (relating to misleading or deceptive conduct, unconscionable conduct and unfair practices) in the Australian Securities and Investments Act 2001, administered by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Source: ANAO, based on Schedule 2, Competition and Consumer Act 2010.

Multiple regulator model

1.3 The Australian Consumer Law, when introduced in 2011, replaced a range of existing Commonwealth and state and territory fair trading laws. The Australian Consumer Law was the result of an Intergovernmental Agreement that was one of the regulatory reform programs of the Council of Australian Governments that aimed to deliver a seamless national economy.

1.4 To create a national consumer protection framework (shown in Figure 1.2), each state and territory has passed legislation applying the Australian Consumer Law as a law of its jurisdiction. The Australian Consumer Law, as passed by the Commonwealth, applies to the conduct of corporations as suppliers of goods and services, and to all transactions that occur across state borders. The legislative scheme in each state and territory governs the way in which consumers can access state courts and tribunals (for example, providing access to the state and territory-based small claims tribunals for breaches of the Australian Consumer Law). The state and territory laws also deal with specific enforcement issues and procedures (for example, providing powers to the various state and territory fair trading agencies).

Figure 1.2: Consumer protection framework

Source: ANAO analysis of the consumer protection framework.

1.5 Under the Intergovernmental Agreement, responsibility for enforcement and administration of the Australian Consumer Law is shared between the ACCC and the state and territory fair trading agencies, under an arrangement that has been referred to as a ‘multiple regulator model’. To support administration and enforcement of the Australian Consumer Law under this model, the ACCC, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the state and territory fair trading agencies entered into a Memorandum of Understanding in 2010. The ACCC also engages regularly with the other regulators individually, and through a range of committees of the Council of Australian Governments’ Legislative and Governance Forum on Consumer Affairs.

1.6 In practice, the ACCC is responsible for administering and enforcing the Australian Consumer Law in relation to conduct that is of a national character—that is, where the conduct is affecting, or has the potential to affect, consumers in multiple states. By contrast, the state and territory regulators have a greater focus on conduct occurring wholly within the state or territory, and especially in industries where there are specific state or territory laws applying (for example, in relation to residential tenancies). However, the nature of the consumer protection framework means that the state and territory regulators retain jurisdiction in relation to all conduct occurring within their geographic borders.

The ACCC’s regulatory approach

1.7 In its 2015–16 Corporate Plan, the ACCC stated that its budget for fair trading activities was $51.8 million and its average staffing level was 218.1 for these activities.2

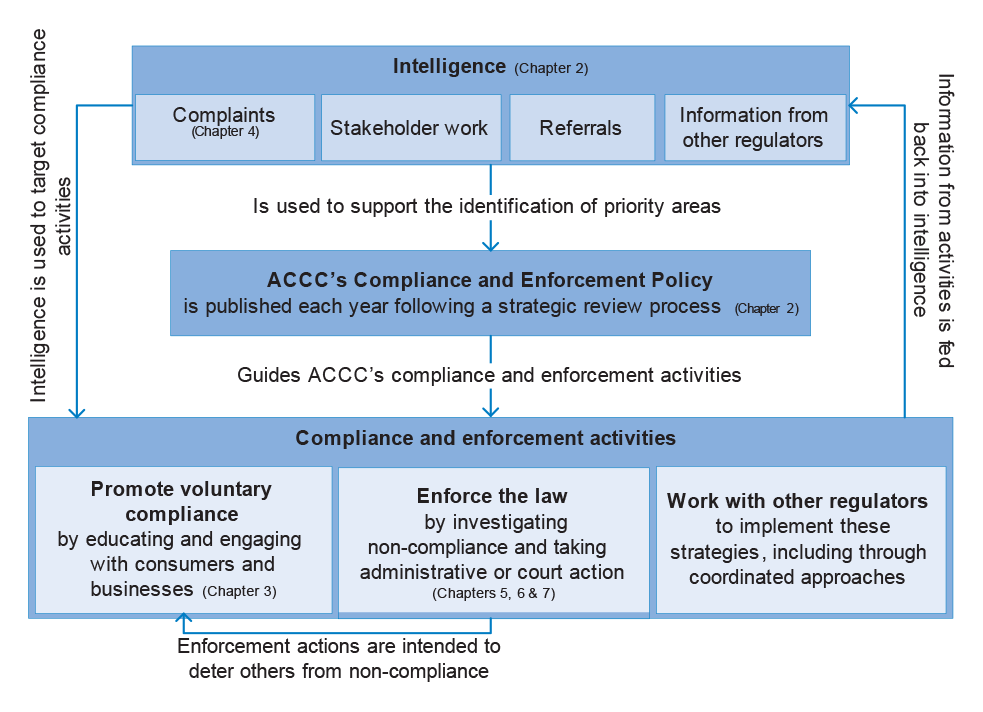

1.8 The ACCC’s approach to administering and enforcing the Australian Consumer Law (including compliance with fair trading obligations) is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: The ACCC’s fair trading regulatory approach

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

1.9 Each year, the ACCC undertakes a strategic review in which it considers information and intelligence available to identify the issues that pose the greatest risk of widespread consumer detriment, including new and emerging issues. Following the strategic review, the ACCC publishes its Compliance and Enforcement Policy, which sets out the principles adopted to achieve compliance with the law and outlines the ACCC’s enforcement powers, functions, priorities, strategies and regime.3 Importantly, the Policy identifies priority areas for a given year, which are areas where the ACCC considers there is the greatest risk of widespread consumer detriment.

1.10 In managing compliance with fair trading obligations, the Compliance and Enforcement Policy states that the ACCC takes action to stop unlawful conduct and deter future offending conduct. It does this by: enforcing the law (including by investigation and taking administrative and court action in relation to non-compliance); encouraging voluntary compliance through educating and engaging with consumers and businesses; and working with other regulators. In deciding what actions to take, the ACCC assesses non-compliance or the risk of non-compliance (as identified through information and intelligence4, including complaints) against the priority areas in its Compliance and Enforcement Policy.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.11 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in managing compliance with fair trading obligations.

1.12 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO has adopted the following high-level criteria:

- appropriate governance arrangements are in place to support the effective management of compliance with fair trading obligations;

- compliance risks are identified, and a strategy is in place to guide the ACCC’s fair trading regulatory activities;

- appropriate actions are taken to encourage voluntary compliance with fair trading obligations; and

- responses to non-compliance are timely, effective and proportionate to the risks presented by the non-compliance.

1.13 The scope of the audit was the ACCC’s activities in relation to fair trading. The ACCC’s activities in relation to product safety, competition and infrastructure regulation were not considered as part of the audit.

Audit methodology

1.14 The ANAO considered the ACCC’s processes to assess compliance risk, activities to promote voluntary compliance and its actions in responding to non-compliance.

1.15 The audit methodology included: examining relevant policy documents, guidelines and procedures; reviewing minutes of internal governance meetings; interviewing relevant ACCC staff and key stakeholders; and reviewing samples of projects, cases and enforcement outcomes from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2015.

1.16 The audit has been conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $340 000.

2. Managing fair trading compliance risks

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the ACCC’s management of risk; compliance and enforcement strategy; and processes for gathering, analysing and using information and intelligence, to assess whether its approach to managing compliance with fair trading obligations is supported by sound risk management and intelligence processes.

Conclusion

The ACCC has a sound compliance and enforcement strategy and established processes for identifying and managing risks, including an extensive consultative strategic review process to determine key strategic compliance risks. However, it could improve the management of these risks by more fully evaluating their mitigation strategies, and by applying a systematic risk management approach to all of its key strategic compliance risks. The ACCC is also not systematically analysing its complaints data, and could explore the benefit of obtaining comprehensive complaints data held by state and territory fair trading regulators.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at the ACCC improving the extent and use of information for intelligence purposes.

Does the ACCC’s risk management framework support the effective management of fair trading compliance risks?

The ACCC’s arrangements for managing risks only partially accord with the Commonwealth’s Risk Management Policy. While the annual strategic review process has been effective in identifying the ACCC’s key strategic compliance risks, these priorities have not been managed through a consistent risk-based approach, including arrangements for evaluating outcomes. Addressing these gaps would facilitate more consistent risk management across the ACCC.

2.1 Under the Commonwealth’s Regulator Audit Framework, the ACCC is expected to have a risk-based and proportionate approach to ensuring that traders comply with their fair trading obligations.5 As the ACCC is an ‘entity’ for the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, it is also required to apply the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy (Commonwealth Policy).6

2.2 As a Comcare fund member, the ACCC is required to participate in the annual Comcover Risk Management Benchmarking Programme. The Programme measures the risk management capability of entities using a risk maturity model, and involves completion of an online self-assessment survey. In responding to the survey in early 2015, the ACCC assessed that:

- its three greatest strengths (in descending order of importance) were establishing a risk management policy, communicating and consulting about risk and defining responsibility for managing risk; and

- its three areas requiring greatest development were developing a positive risk culture, maintaining risk management capability and understanding and managing shared risk.

2.3 The Commonwealth Policy requires an entity to define its risk appetite (the amount of risk it is willing to accept or retain in order to achieve its objectives) and risk tolerance (the levels of risk taking that are acceptable to achieve a specific objective or manage a category of risk). The ACCC risk appetite is low to medium (that is, it does not accept risks that are high following risk treatments). However, the ACCC does not have a formal risk tolerance policy.

2.4 Each year, the ACCC updates its ‘risk profile’, which sets out its strategic, enterprise wide and divisional risks. At all risk levels, risk owners are designated, and risks are evaluated based on likelihood and consequence. The ACCC’s strategic risk profile is extensively considered by senior management committees and the Chairman prior to final endorsement by the Corporate Governance Board. The profile lists the divisional risks rated as high, enterprise-wide operational risks and strategic risks, and identifies the impact of the risk occurring, the initial risk level, any mitigation strategies, and the residual risk level. The risk registers for other risks record their likelihood, consequence and initial risk level. A comparison of the ACCC’s strategic risks for 2013–14 and 2014–15 indicated that the ACCC reviewed and revised many of its risks.

2.5 The ANAO examined the minutes of the ACCC’s Corporate Governance Board, which has a role to review and approve the ACCC’s annual risk management plan. According to the minutes, in 2014 the Board was extensively involved in setting the ACCC’s strategic risks and risk mitigation strategies. Also, the Board received briefings from the audit committee, demonstrating the committee’s close involvement in oversighting the ACCC’s risks. Further, divisions put significant effort into identifying their risks.

2.6 The nine essential elements of the Commonwealth Policy, and the ANAO’s assessment of the ACCC’s compliance with these elements, in respect of its responsibilities for fair trading, are set out in Table 2.1. As indicated in the table, the ACCC needs to undertake further work to comply with the Commonwealth Policy.

Table 2.1: The ACCC’s compliance with the essential elements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy

|

Element |

Level of compliance |

Assessment |

|

Establishing a risk management policy |

Partially |

Has a policy which is based on AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines, but which has not been fully updated in line with the Commonwealth Policy. |

|

Establishing a risk management framework |

Partially |

The ACCC intranet has a ‘Risk management’ page with links to risk policies, tools and templates. The ACCC’s key strategic compliance risks (priorities) for fair trading are not explicitly covered in the framework. |

|

Defining responsibility for managing risk |

Fully |

The risk profile identifies a risk owner and manager for each level of risk. |

|

Embedding systematic risk management into business processes |

Partially |

The ACCC is not systematically applying risk management approaches to its priorities. Only some priorities have had formal risk mitigation approaches by having projects created for them. |

|

Developing a positive risk culture |

Partially |

The ACCC self-assessed this element as requiring development. |

|

Communicating and consulting about risk |

Fully |

The ACCC consults widely with key stakeholders on its strategic compliance risks. |

|

Understanding and managing shared risk |

Partially |

Shared risks arise in cross-entity arrangements. To help manage these risks, the ACCC has Memoranda of Understanding with other relevant agencies and Ombudsmen arrangements. However there is scope for improvement, for example by highlighting specific shared risks in the ACCC’s risk profile. |

|

Maintaining risk management capability |

Partially |

While the ACCC has structures for managing risk, including a Chief Risk Officer and an Audit Committee, it could build risk management awareness and knowledge through greater internal communication and specific training. |

|

Reviewing and continuously improving the management of risk |

Fully |

The risk management policy is currently being updated. The risk management framework was last updated in December 2014. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

Identification of the ACCC’s priorities

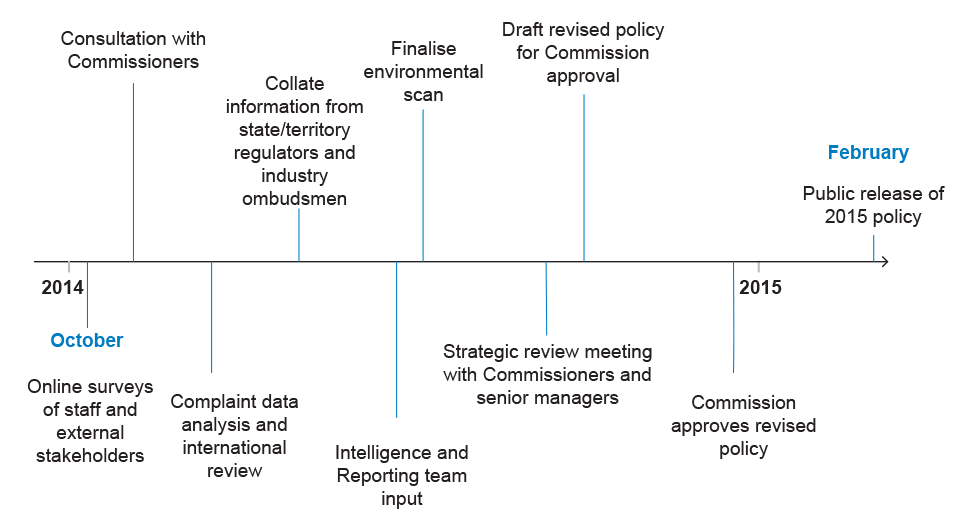

2.7 The ACCC undertakes an annual process, called the strategic review, to determine its priorities for the following year and the risks to achieving its objectives. The result of this process is the publication of the ACCC’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy, which contains a list of priority areas for the year. Figure 2.1 outlines the timeline of the strategic review process for developing the 2015 Compliance and Enforcement Policy.

Figure 2.1: Strategic review process for developing the ACCC’s 2015 Compliance and Enforcement Policy

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

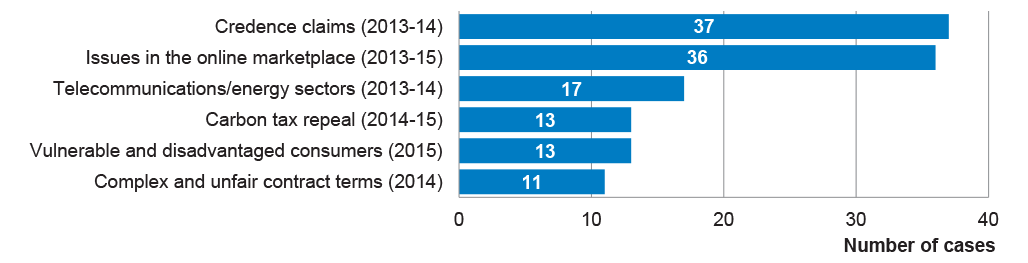

2.8 As part of the strategic review, to identify emerging issues the ACCC relies on information from a wide range of sources, including: internal complaints data; views of Commissioners; a survey of staff; a survey of, and meetings with, key stakeholders; and an assessment of media, research and other sources. In 2014, the ACCC sent a survey to 150 stakeholders, and received 21 responses. Stakeholders that were surveyed as part of this process included state/territory regulators, industry ombudsmen, consumer groups and business groups. A key aim of the strategic review process is to identify issues that should no longer be a priority, and new or emerging issues that warrant inclusion as a priority. Table 2.2 shows the ACCC’s fair trading priorities as outlined in the Compliance and Enforcement Policy documents for 2014 and 2015. The changes to the priorities between 2014 and 2015 were more significant than the changes between other years, with the removal of four priority areas, addition of four new priority areas and refocusing of three priority areas.

Table 2.2: The ACCC’s fair trading priorities, 2014 and 2015

|

Priority |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Truth in advertising |

No |

Yes |

|

Consumer issues in the health and medical sectors |

No |

Yes |

|

Ensuring compliance with new or amended industry codes of conduct |

No |

Yes |

|

Emerging systemic consumer issues in the online marketplacea |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Consumer issues in highly concentrated sectorsb |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Disruption of scams that rely on building deceptive relationships and cause severe and widespread consumer or small business detriment |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Misleading carbon pricing representationsc |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Consumer protection issues impacting on Indigenous consumers |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Consumer protection issues impacting on vulnerable and disadvantaged consumers |

No |

Yes |

|

Consumer protection in the telecommunications sector and in the energy sector, focusing on savings representations |

Yes |

No |

|

Complexity and unfairness in consumer or small business contracts |

Yes |

No |

|

Credence claimsd |

Yes |

No |

|

The Australian Consumer Law consumer guarantees regime |

Yes |

No |

Note a: Refocussed in 2015 from ‘drip pricing’ to include issues ‘associated with systemic failures by online retailers or retail sectors’.

Note b: Refocussed in 2015 to include ‘issues identified through the ACCC’s monitoring of the fuel sector’.

Note c: Refocussed in 2015 to ‘finalising its role in ensuring that carbon tax cost savings are being passed through to consumers’.

Note d: Credence claims arise where the consumer cannot independently verify the claims themselves and must trust the seller. An example of a credence claim is a claim that a product is ‘environmentally friendly’.

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

2.9 While the strategic review process provides a sound approach for identifying priorities, the ACCC does not have a systematic, risk-based approach for addressing these priorities7, or a clear basis for evaluating its performance in addressing existing priorities.8 As a result, when each subsequent strategic review is conducted, there is not as firm a basis as possible for retaining some priorities, and relegating others. To better address strategic priorities, the ACCC should more systematically apply a risk-based approach to managing mitigation treatments, and determine a basis for evaluating performance in addressing existing priorities.

Is there an effective compliance and enforcement strategy?

The ACCC has a sound compliance and enforcement strategy that outlines a set of proportionate and graduated approaches to encouraging voluntary compliance and addressing non-compliance.

2.10 A risk-based and proportionate compliance and enforcement approach assists regulators to target their limited resources appropriately. As noted previously, the result of the ACCC’s strategic review process is a Compliance and Enforcement Policy, which outlines the ACCC’s annual priorities and its strategies and powers to achieve compliance with the law.

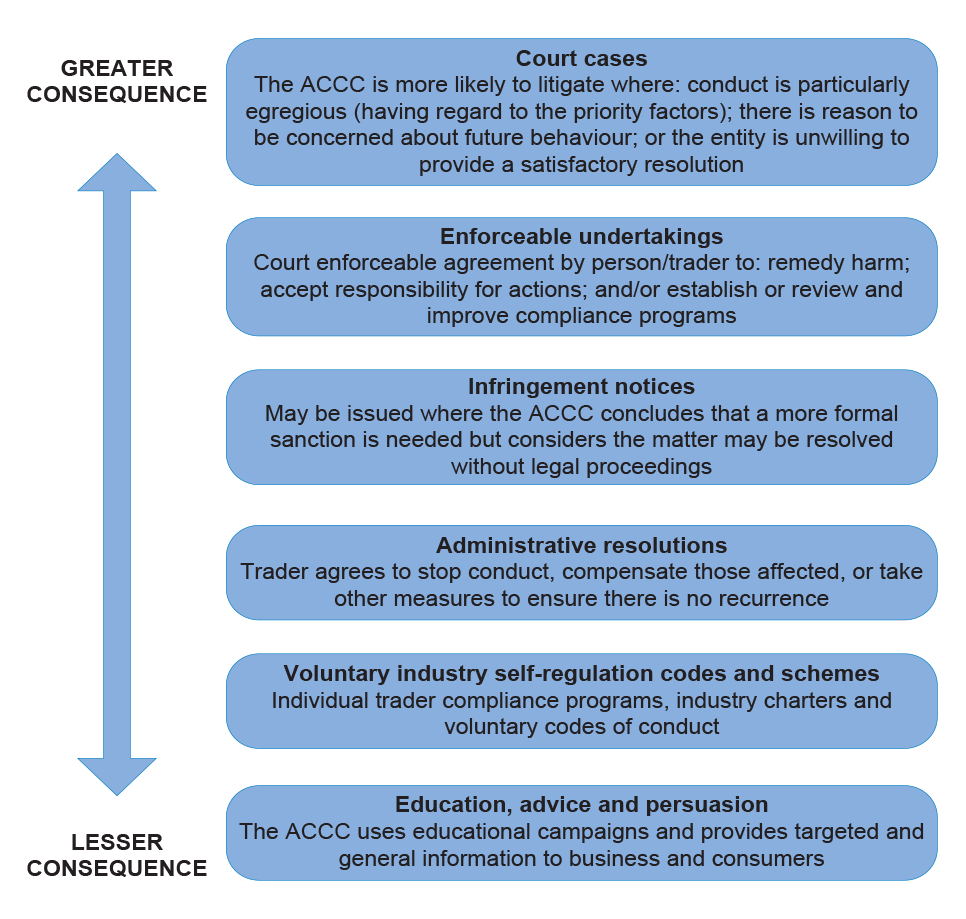

2.11 As set out in the Compliance and Enforcement Policy, to achieve its compliance objectives, the ACCC employs ‘three flexible and integrated strategies’: enforcement of the law; encouraging compliance with the law; and working with other regulators to implement these strategies. These strategies are employed using a range of compliance and enforcement tools, outlined in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: The ACCC’s approach to compliance and enforcement

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

2.12 In deciding which compliance or enforcement tool to use, the ACCC states that its first priority is ‘always to achieve the best possible outcome for the community.’ The Compliance and Enforcement Policy makes clear that risk—in terms of detriment to consumers—is taken into account when making decisions about the appropriate compliance or enforcement action. The Policy says that an administrative resolution may be appropriate ‘for example, where the ACCC assesses potential risk flowing from conduct as low’. By contrast, court action is more likely where ‘the conduct is particularly egregious, where there is reason to be concerned about future behaviour, or the party involved is unwilling to provide a satisfactory resolution’.

2.13 The Compliance and Enforcement Policy is supported by other guidance, including its cooperation policy and guidance on the use of infringement notices and enforceable undertakings. The guidance on infringement notices and enforceable undertakings sets out instances where the ACCC is relatively more or less likely to use one of these regulatory tools. Many of these factors relate to the risk to consumers posed by a particular conduct—for example, the ACCC states it is less likely to issue infringement notices where: it considers the concerns are more serious in nature; there has been significant detriment; it has concerns that the conduct may be continuing; or it has previously taken action against the person involved in the contravention.9

2.14 The ACCC’s compliance and enforcement strategy is risk based, with lighter-touch, more persuasion-oriented actions more likely for those willing to comply and heavier-touch, enforcement-oriented actions for entities unwilling to comply, or where there is a significant level of consumer detriment or impact to competition. This approach is sound and provides a framework for the ACCC to direct its resources to those cases where the risk to consumers is greatest. The extent to which the ACCC undertakes its fair trading enforcement activities in accordance with the strategy is considered in Chapter 7.

Are there robust processes for gathering information and analysing and using it for intelligence purposes?

The ACCC has access to a wide range of information sources, which it uses to identify systemic compliance risks, target compliance activities and support investigations into non-compliance with fair trading obligations. However, in undertaking these activities the ACCC relies too heavily on its own complaints data, and could make greater use of other sources of information, including public data and the complaints data of other regulators (see Recommendation No. 1). In analysing information, the ACCC’s Intelligence and Reporting team prepares a range of useful reports for intelligence purposes. To support better targeting of compliance and enforcement activities, these reports could focus more on identifying higher risk traders, industries and issues.

2.15 To enable the ACCC to appropriately identify regulatory risks and target compliance and enforcement activities, it is important that it has effective arrangements for gathering regulatory information, and analysing and using it for intelligence purposes. Regulatory intelligence can be used for three main purposes—identifying systemic compliance risks, targeting compliance and enforcement activities, and supporting investigations into non-compliance (for example, by providing leads to evidence). Chapter 4 considers the use of intelligence in case selection.

Gathering regulatory information

2.16 The ACCC makes use of a range of internal and external information sources to inform its intelligence and compliance activities. The more important of these are outlined in Table 2.3. Most of the information sources are primarily used in investigating instances of non-compliance with fair trading obligations.

Table 2.3: The ACCC’s main sources of regulatory information

|

Source |

Information gathering and recording |

|

Complaints from the public |

Allegations of non-compliance (contacts) are received by the ACCC Infocentre, mainly from members of the public. Information is retained in the contact management system. |

|

Investigations |

ACCC staff record the actions they undertake in their investigations. Information is retained in the case management system. |

|

Cooperation with other regulators and industry ombudsmena |

The ACCC frequently communicates, and exchanges information, with the other Australian Consumer Law (ACL) regulators and industry ombudsmen. The ACLink database facilitates discussion and information sharing amongst ACL regulators (as discussed at paragraph 2.19). |

|

Media and other public commentary |

The ACCC monitors print, radio and internet news articles relevant to the ACCC’s operations. |

|

Stakeholders |

The ACCC receives stakeholder complaints and input to ACCC consultative committees. |

|

Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre |

Database of financial transaction information. Includes data from reports of significant cash transactions, suspect transactions and international currency transfers. |

|

Australian Securities and Investments Commission company database |

Allows users to: obtain company names, business names, key personnel and documents; and search for banned and disqualified persons. |

|

International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network |

Shares information about cross-border commercial activities that may affect consumer interests. |

Note a: Examples of industry ombudsmen are: the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, the NSW Energy and Water Ombudsman, the Financial Ombudsman Service and the Health Complaints Commissioner Tasmania.

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

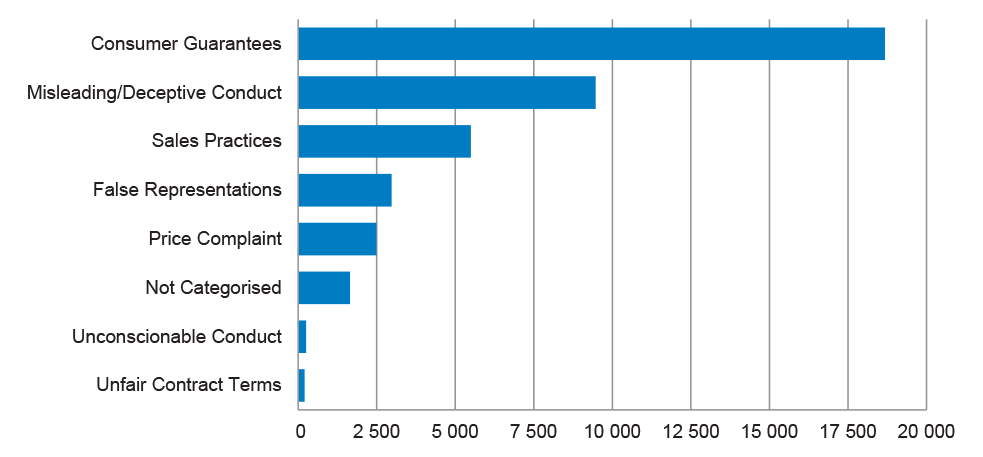

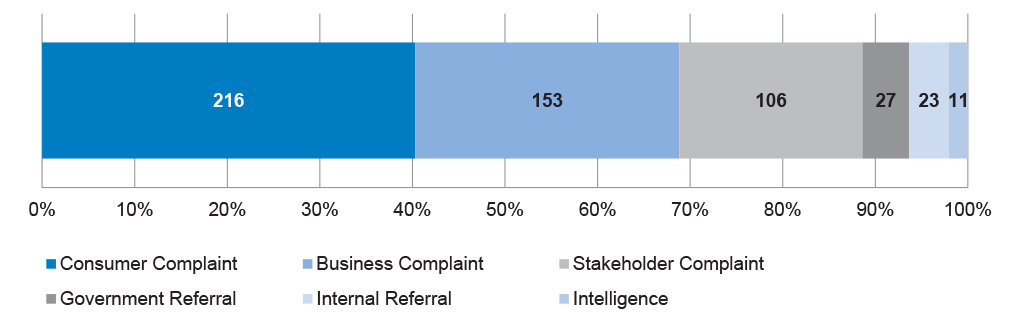

2.17 The main source of information for the ACCC in targeting its compliance and enforcement activities (and a significant source for identifying systemic risks) is the contacts it receives from consumers. In 2014–15, approximately 165 000 contacts were recorded in the ACCC’s database, of which over 41 000 were related to consumer protection. Figure 2.3 shows the number of fair trading contacts the ACCC received in 2014–15, broken down by the issue to which the contact related.

Figure 2.3: ACCC fair trading contacts by category, 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC data.

2.18 Despite these many contacts, the ACCC receives only a small proportion of the total number of consumer contacts relating to potential instances of non-compliance with fair trading obligations throughout Australia. Like the ACCC, other Australian Consumer Law regulators and industry ombudsmen also receive complaints from members of the public raising instances of potential non-compliance with fair trading obligations. Figure 2.4 indicates that the ACCC only received around six per cent of the approximately 720 000 fair trading related complaints received by Australian Consumer Law regulators and industry ombudsmen in 2013–14.

Figure 2.4: Fair trading contacts received by fair trading regulators and industry ombudsmen, 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of regulator and ombudsman data.

2.19 Notwithstanding the importance of complaints information in selecting and conducting compliance activities, the ACCC receives complaints information from the states, territories and ombudsmen only on an ad-hoc basis, and usually in an aggregated form. Information sharing between the Australian Consumer Law regulators, for example, mainly occurs through ACLink, an online collaboration website. ACLink allows Australian Consumer Law regulators to request and post information about topics of interest—such as traders, industries and conduct. While this is useful in the context of individual investigations (such as in reducing duplication of investigative efforts), it is significantly less useful than complete disaggregated complaints data for the purposes of identifying trends, patterns and issues of concern.

2.20 Recognising the potential for better targeting of compliance activities, in 2005 the ACCC proposed the establishment of a National Consumer Complaints Database, which was not progressed due to lack of available funding. In view of advancements in processes to record and share information since that time, there is scope for the ACCC to re-examine opportunities to work with other regulators to obtain complaints data on a regular and disaggregated basis. This information could potentially be stored in a data warehouse to allow easy analysis by analysts and investigators, to support a greater understanding of non-compliance with fair trading obligations.

2.21 There is also scope for the ACCC to gather other publicly available information about potential consumer detriment in the market. Increasingly, consumers are using the internet—through social media and online review sites—to communicate and publicise difficulties they have had with traders. The ACCC could make use of this, and other information, in a systematic way to increase its understanding of issues facing consumers.

Analysis and use of information for intelligence purposes

2.22 As noted previously, the information that the ACCC collects, including from the sources listed in Table 2.3, is used for a number of intelligence purposes. These purposes include identifying priorities as part of the strategic review process and identifying potential non-compliance to target compliance and enforcement activities. At present, the main analysis and use of information to assess compliance risk is through regular and ad-hoc reports prepared by the ACCC’s Intelligence and Reporting team. The main types of intelligence reports are provided at Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Main types of ACCC intelligence reports

|

Type of report |

Description |

|

Brief for strategic review |

Identifies emerging competition and consumer issues based on environmental scanning and external online sources. |

|

Contact and intelligence report |

Monthly report to the Enforcement Committee mainly focusing on contacts/complaints. |

|

Trader brief |

Sets out information about a particular trader, such as those that had been trending in complaints. |

|

Industry profile |

Examines an industry to identify issues of concern. |

|

Trend analysis report |

Uses a variety of filters to identify new issues, trends and matters of concern. May identify several traders across industries. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

2.23 The reports serve a number of useful functions. For example, the brief for the strategic review helps to identify potential priorities and developments in the external environment, while the trend analysis reports identify emerging issues. The trader briefs and industry profiles are valuable in identifying traders not complying with fair trading obligations, and support the ACCC’s project work.

2.24 As part of these reports, however, the ACCC does not identify traders, industries or issues of relatively greater or lesser risk. The Intelligence and Reporting team’s monthly report to the Commission, for example, is mainly limited to the number of complaints received about particular traders. It does not go further to identify the level of risk (in terms of consumer detriment) associated with those complaints. Also, while the team’s reports expressly refer to ACCC complaints, they less often refer to other relevant sources, such as environmental scans.

2.25 Importantly, the ACCC does not systematically assess and analyse the information that it receives to help target compliance and enforcement activities, instead relying on these to be identified through manual work of the Intelligence and Reporting team. It is noted that a number of other Commonwealth regulators have adopted a quantitative and systematic risk differentiation approach, including the Australian Taxation Office, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority and the Australian Fisheries Management Authority. There would be value in the ACCC also adopting a quantitative and systematic approach to risk differentiation and prioritisation in order to better target its compliance and enforcement activities. There is scope for the ACCC to undertake risk scoring of information that it receives—particularly complaints.

2.26 In relation to complaints, risk scoring could work in two ways:

- matters could be scored by Infocentre staff at the time a contact is logged; and/or

- a computer-based risk scoring algorithm could be developed to provide assurance that staff are identifying and scoring matters correctly.

2.27 A computer-based risk scoring algorithm, in particular, would support a better understanding of the ACCC’s risk population. As part of such an algorithm, risk scores for complaints could reflect, for example: whether the complainant was vulnerable or disadvantaged; the type of non-compliance; whether the complaint relates to an ACCC priority area; and the trader and industry involved. These risk scores could also be used to generate a risk score and profile for traders, which could be monitored over time and could prove especially helpful for targeting compliance and enforcement activities towards the areas of greatest need.

Recommendation No.1

2.28 To improve the extent and usefulness of information obtained for intelligence purposes, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission examines the merit of regularly obtaining complaints data feeds from other Australian Consumer Law regulators.

The ACCC’s response: Agreed.

Does the ACCC effectively monitor and report on its performance in managing fair trading compliance?

In accordance with current Commonwealth guidance, the ACCC uses a number of measures, including performance indicators, case studies and survey results, to monitor and report on its performance. While they have improved over time, most of these measures are output-based, and developing measures of outcomes would enable the ACCC to report in ways that better illustrate its effectiveness in improving trader compliance with fair trading obligations.

2.29 As an entity subject to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the ACCC is required to measure, assess and report on its performance in accordance with the Commonwealth performance framework. As a regulator, it is also required to measure and report on its performance in accordance with the Regulator Performance Framework.10

2.30 The ACCC’s approach to performance measurement comprises:

- a suite of performance indicators linked to its key organisational strategies and deliverables that it will measure and report against in its annual performance statement—to be supplemented with specific examples of actions and outcomes11;

- in relation to the Regulator Performance Framework, the ACCC has adopted a self-assessment methodology to assess its performance against the six Regulator Performance Framework performance indicators—with external validation to be provided by the ACCC Performance Consultative Committee12; and

- a biennial consumer and small business survey that aims to gauge the level of consumer understanding of the ACCC’s roles and functions—and a proposed comprehensive biennial business-focussed survey measuring business views of the ACCC’s performance.

2.31 A selection of the ACCC’s key performance indicators for its fair trading activities, and the ANAO’s assessment of these indicators, is set out in Table 2.5.13

Table 2.5: Analysis of selected ACCC key performance indicators for fair trading

|

Performance indicator |

ANAO assessment |

|

Number of in-depth ACL investigations completed |

Measurable, but an output indicator or deliverable. The indicator does not address whether and how the completed investigations achieved the ACCC’s objectives. |

|

Percentage of ACL enforcement interventions in the priority areas outlined in the Compliance and Enforcement Policy |

Measurable. The link to the Compliance and Enforcement Policy helps to show that the ACCC is directing its enforcement intervention towards its strategic priorities. |

|

Number of new or revised business compliance resources (published guidance) |

Measurable as a deliverable. The indicator does not address whether and how the resources were effective in promoting voluntary compliance. |

|

Number of times online business education resources have been accessed |

Measurable. Although an output indicator, can indirectly help measure effectiveness as it suggests online resources are being widely accessed. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

2.32 As shown in Table 2.5, the ACCC’s performance indicators are largely focused on measuring outputs and not on the extent to which the ACCC’s activities were effective, as may be shown, for example, by improved trader conduct following a compliance or enforcement action. The performance indicators taken together are not currently complete, as they do not provide an overall picture of the impact of the ACCC’s activities. It is noted, however, that the ACCC has been improving its key performance indicators over time (previously, they were more general and were less qualitative), and that the inclusion of specific examples of actions and outcomes that show the impact of the ACCC’s activities may go some way to presenting a more complete picture of the ACCC’s performance.14

2.33 In relation to its Regulator Performance Framework self-assessment methodology, the ACCC has developed a range of measures and examples of evidence to support its key performance indicators. Several of the evidence examples are useful, as they aim to demonstrate that the ACCC has: been timely in its enforcement actions; undertaken good practice consultation; or been effective. However, some other examples involve simply confirming that the ACCC has published a document or followed a process.15 It would be more meaningful if the ACCC included evidence of business awareness and satisfaction, or data such as the number of revisions of compulsory information-gathering notices.

2.34 The ACCC reports externally on its fair trading activities through its annual report and quarterly publication, ACCCount. In its 2014–15 annual report, the ACCC provides performance information, including about successful enforcement outcomes, case studies, and survey results. While helpful, the ACCC could give greater emphasis to instances where its interventions have led to changes in compliance behaviour, and to presenting both positive and negative survey results. The ACCCount publication is also focused on deliverables, such as the number of ACCC enforcement activities undertaken, its other fair trading outputs (such as publications) and stakeholder engagement and government liaison activities in the quarter.

2.35 Overall, there is scope for the ACCC to improve its performance measurement and reporting, to better demonstrate how its activities lead to an improvement in trader compliance with fair trading obligations. The surveys that the ACCC undertakes (and is planning to undertake) of consumers and businesses position it well to do this, as survey results can be proxies for the effectiveness of regulatory activities. There is also an opportunity for the ACCC to make greater use of data, ranging from complaints data to stakeholder feedback, to gain a better understanding of how its activities are influencing the level of consumer detriment within Australia. This variety of data, when used in systematic evaluations, would provide the basis for case studies and other examples of actions and outcomes in annual performance statements.

3. Promoting voluntary compliance

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the ACCC’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance with fair trading obligations, including guidance and engagement activities and specific projects that have addressed priority compliance issues.

Conclusion

The ACCC’s voluntary compliance activities are well targeted, have often achieved good results, and are viewed positively by key stakeholders. However, its projects are infrequently evaluated, so there is limited evidence of their effectiveness. There is also scope for the ACCC to increase the awareness of consumers and traders about where to get advice about their fair trading rights and obligations.

Area for improvement

The ANAO suggested that the ACCC better manage risks in conducting compliance projects (paragraph 3.18).

Do the ACCC’s guidance and engagement activities effectively support voluntary compliance?

The ACCC’s information and advice about fair trading rights and obligations is clear and targeted to the main areas of consumer and business concern. This information is disseminated through traditional channels and social media such as Facebook and Twitter. Of primary importance is the ACCC website, which is clearly organised and easy-to-use. Consumer and business stakeholders contacted by the ANAO consistently commented positively on the ACCC’s engagement with them.

3.1 Effective promotion of voluntary compliance, such as by informing consumers and traders about their fair trading rights and obligations, is an important component of regulators’ compliance strategies, as it minimises the need to apply more costly enforcement measures.

3.2 The ACCC’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy states that the ACCC seeks to strike the right balance between voluntary compliance and enforcement.16 The ACCC provides a range of information and advice to encourage compliance with fair trading obligations, which is disseminated through the ACCC’s website and other channels, including social media.

Providing guidance through the ACCC’s website and social media

The ACCC’s website

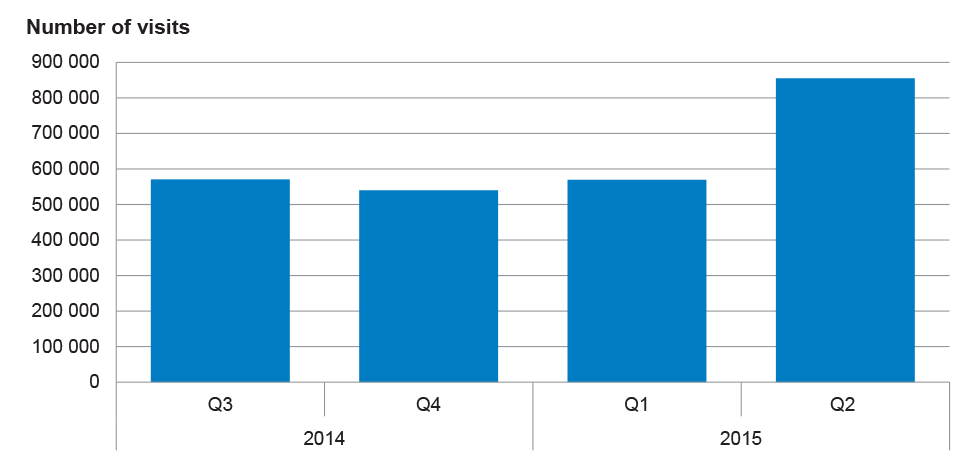

3.3 Between June 2014 and June 2015, the ACCC’s website had 2.5 million recorded visits. The website typically received around 550 000 visits per quarter over this period, as indicated in Figure 3.1.17

Figure 3.1: Visits to the ACCC’s website by quarter, June 2014 to June 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC data.

3.4 The ACCC’s website is clearly organised and easy-to-use, being structured around three main sections—consumers, business and regulated infrastructure. Relevant to fair trading, the business section provides information for traders on their rights in relation to business-to-business transactions and on their obligations to consumers under sections titled ‘treating customers fairly’, ‘advertising and promoting your business’ and ‘pricing’.

3.5 The consumer section provides information on a range of issues (such as consumer guarantees and misleading advertising) and industries (such as motor vehicles and telecommunications). There was a clear alignment between the topics listed in the consumer section of the ACCC’s website and the issues and industries that are an ACCC priority, and/or the subject of a large volume of consumer complaints (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Information on fair trading issues provided in the consumer section of the ACCC’s website

|

Topics listed |

Relation to ACCC priority or source of contacts |

|

Consumer rights and guarantees |

Consumer guarantees are the ACCC’s single largest source of fair trading complaints and were recently an ACCC priority. |

|

Consumer protection |

Provides information on product safety (an ACCC priority), scams (an ACCC priority) and how consumers can seek help. |

|

Misleading claims and advertising |

Misleading and deceptive conduct is the ACCC’s second largest source of fair trading complaints. Truth in advertising is also an ACCC priority. |

|

Prices and receipts |

Drip pricinga was recently an ACCC priority and a compliance project. |

|

Sales and delivery |

Door-to-door sales were recently an ACCC priority and an ACCC compliance project. |

|

Contracts and agreements |

Complexity and unfairness in consumer contracts were recently an ACCC priority and the subject of a compliance project. |

|

Debt and debt collection |

Debt collection has been an ACCC compliance project. |

|

Groceries |

The ACCC has an ongoing project regarding claims that eggs are ‘free range’. Grocery items generate a large number of complaints concerning credence claims (which was recently an ACCC priority) and truth in advertising (a current priority). |

|

Health, home and car |

Consumer issues in the health and medical sectors are an ACCC priority. |

|

Online shopping |

Emerging systemic consumer issues in the online marketplace are an ACCC priority. |

|

Internet and phone; National Broadband Network |

Consumer protection in the telecommunications sector was recently an ACCC priority and conduct involving essential services is a current priority factor. Mobile networks and in-app purchasesb have been ACCC projects. |

|

Petrol, diesel and liquid petroleum gas |

Consumer issues in highly concentrated industry sectors are an ACCC priority. |

Note a: Drip pricing is where a headline price is advertised at the beginning of an online purchasing process and additional fees and charges that may be unavoidable are then incrementally disclosed.

Note b: The purchase of goods and services from an application on a mobile device, such as a smartphone or tablet.

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

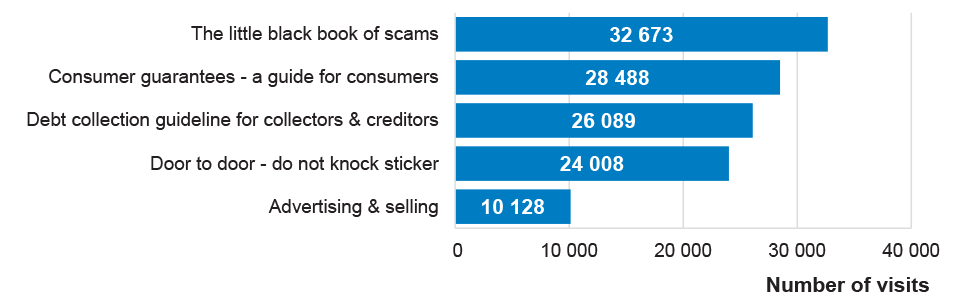

3.6 In addition to the information available on web pages on its website, the ACCC makes a range of publications available via its website and in hard copy. In relation to fair trading, these cover a number of issues including providing detailed guidance to businesses on how they can comply with their obligations and to consumers on their rights. The publications that had the most web visits between January 2014 and June 2015 are set out in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Top five accessed publications relating to fair trading, 1 January 2014 to 30 June 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC data.

3.7 The ANAO examined the ACCC’s five most popular publications relating to fair trading for consumers and business. The consumer publications were accessible, easy to understand and sufficiently detailed. In line with the Government’s Regulator Audit Framework, the business publications were written in plain language, included pertinent examples, and contained consistent information.18 The ACCC’s publications were also well targeted, as shown in Table 3.2, which outlines that guidance was in place for issues that prompted the greatest number of consumer contacts.

Table 3.2: Targeting of ACCC publications

|

Issues with greatest number of contacts |

Publications |

Webpages |

|

Consumer guarantees |

For consumers: Consumer guarantees—a guide for consumers; Repair, replace, refund. For business: Consumer guarantees: a guide for businesses and legal practitioners; business snapshot, training videos. |

Consumer rights and guarantees; Consumers’ rights and obligations |

|

Misleading and deceptive conduct |

Advertising and selling guide. |

For consumers: Misleading claims & advertising. For business: False or misleading statements. |

|

Sales practices |

Fair sales practices (business snapshot). |

For business: Unfair business practices. |

|

Price complaints |

Carbon tax price reduction obligation. |

For consumers: Prices & receipts. For business: Pricing. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

Social media

3.8 Social media provides regulators with the opportunity to communicate with a large audience quickly and at a low cost.19 While consumers still prefer to obtain their information about fair trading from the traditional media and the ACCC’s website, social media is becoming more important.

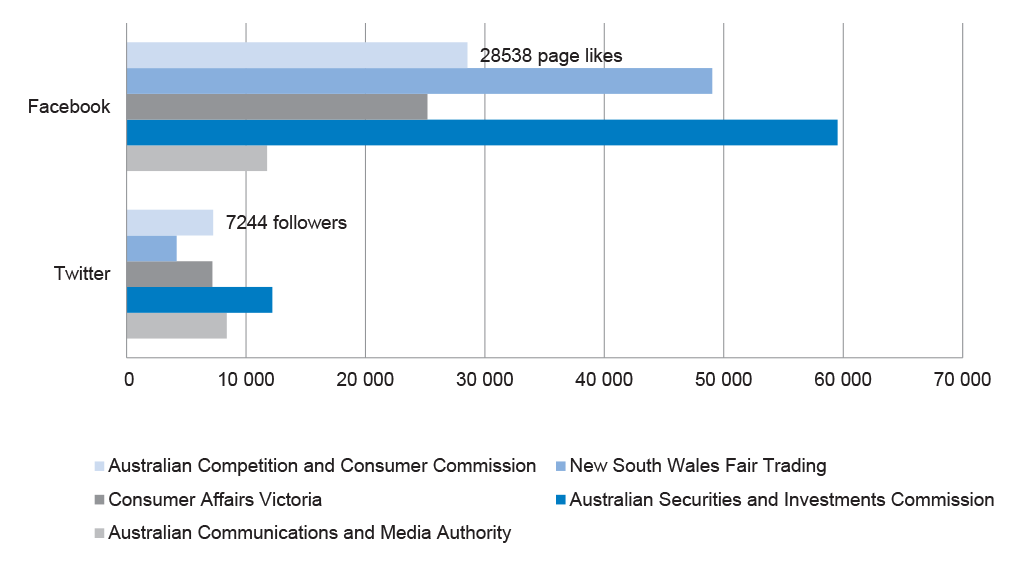

3.9 The ACCC has a social media strategy and currently manages three Facebook pages, three Twitter accounts and two YouTube channels.20 Figure 3.3 shows the number of page likes/followers to the ACCC’s main fair trading (Consumer Rights) Facebook page and Twitter account in comparison to other selected regulators. The figure shows that the ACCC’s social media reach is comparable to the other regulators and that the ACCC’s most popular media channel is its main fair trading Facebook page, with 28 500 page likes as at September 2015.

Figure 3.3: Number of page likes/followers on the ACCC’s Twitter account and main Facebook page, compared to selected regulators, as at September 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of data from the ACCC’s and comparator regulators’ Twitter accounts and Facebook page.

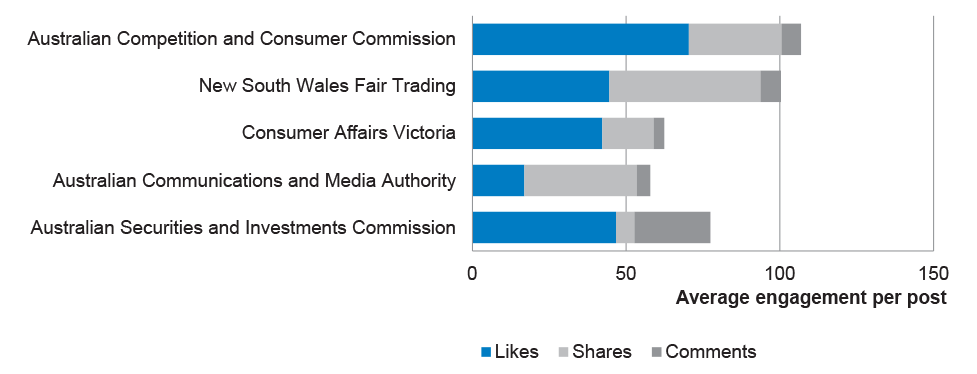

3.10 The ACCC uses its Facebook pages and Twitter accounts for a variety of purposes, including to: build awareness of consumer rights; disseminate media releases and speeches; and promote ACCC activities and events. At 15 September 2015, the ACCC had made 559 posts to its Facebook page and sent 1696 tweets from its Twitter account.

3.11 Overall, there was a relatively high level of engagement with content posted on the ACCC’s social media channels—and the ACCC was a leader compared to the other selected regulators in terms of engagement with its Facebook page. This is shown in Figure 3.54, which presents the average number of times that posts were liked, shared and commented on at the ACCC’s Consumer Rights Facebook page compared to the other regulators. This high level of engagement (particularly shares and likes) makes it more likely that the ACCC’s posts are seen by a wider audience.

Figure 3.4: User engagement with the ACCC’s Facebook page, compared to other selected regulators

Source: ANAO analysis of posts from the ACCC’s and comparator regulators’ Facebook pages.

Stakeholder engagement

3.12 It is important for regulators to have a coordinated approach to engaging with regulated entities, consumers and other regulators with complementary responsibilities. When regulated entities have a clear understanding of their compliance requirements they are better able, and may be more willing, to comply. Also, coordinated engagement can help regulators to gain valuable insights into the behaviour of regulated entities that can be used to guide future compliance activity.

3.13 To support effective consultation with regulated entities and consumers, the ACCC has established a number of consultative forums21 with key stakeholder groups, particularly consumer and industry peak bodies. The ACCC also engages in other ways: for example, it has a team of Education and Engagement Managers who educate the small business sector across Australia about its rights and obligations.

3.14 As part of the audit, the ANAO met with a range of consumer, business and regulatory agency stakeholders. During these meetings, stakeholders mainly commented positively on the ACCC’s engagement with them. A selection of the more representative comments is set out in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Stakeholder views about the ACCC

|

Stakeholder category |

Typical views expressed in interviews |

|

Consumer peak bodies |

The ACCC is highly consultative, both through the Consumer Consultative Committee and on an individual basis. The publication of the ACCC’s enforcement priorities has been very effective in encouraging compliance. The ACCC plays an important role in testing the law. |

|

Industry peak bodies |

The ACCC has shown itself to be a body prepared to take action especially with larger businesses. With smaller businesses it is more light-handed. The ACCC has improved its communication and performance over the last four or five years. |

|

Other Australian Consumer Law regulators |

ACCC cooperates well with other Australian Consumer Law regulators on joint projects. Where the ACCC has lead regulator responsibility, including in emergency situations, it acts promptly. |

Source: ANAO interviews with ACCC stakeholders.

Does the ACCC appropriately manage its compliance projects?

The ACCC’s fair trading compliance projects, which generally contain elements of education and enforcement, are targeted to priority areas and often achieve good results. Of eight projects that it had evaluated, six had positive results and two had mixed results. However, more frequent evaluation and better risk management would provide greater assurance that these projects are well managed, effective and achieved value for money.

3.15 In industries or areas where the ACCC identifies a particular fair trading risk, it often initiates a compliance project aimed at reducing the level of consumer detriment. The most common type of activity undertaken as part of the projects was consumer education. Other activities undertaken included enforcement, media campaigns (including social media), engaging other regulators and strategies involving trader engagement and disadvantaged or vulnerable consumers.

3.16 The following case study provides an example of a project where the main activities were trader engagement and consumer education.

|

Case study 1. Mobile networks coverage and performance issues |

|

This project was initiated in late 2012 in light of growing evidence of consumer detriment arising from network performance related issues, to ensure that providers made accurate representations about mobile coverage and congestion. The Consumer, Small Business and Product Safety Division developed a strategy that included: escalating Australian Consumer Law issues; putting industry on notice; engaging with the Australian Communications and Media Authority about broader network performance issues; and exploring opportunities for consumer education. For example, on World Consumer Rights Day 2014, the ACCC issued a media release and social media posts to remind consumers of their consumer rights in relation to mobile phones and hints and tips for selecting a mobile plan.a The evaluation measures for the project included:

As at April 2014, the ACCC’s evaluations had indicated that:

In September 2013, the ACCC wrote to the three major Australian providers outlining its concerns about the industry. The ACCC received responses from all three providers outlining their activities and improvements relating to mobile network performance and complaints handling. Two of the networks now refer to mobile coverage in their critical information summaries and one network advised that it is committed to additional staff training to emphasise the importance of coverage representations at the point of sale. In October 2014, the ACCC undertook a project debrief that identified key outcomes and lessons learned. |

Note a: ACCC, Get to know your phone rights: World Consumer Rights Day 2014 [Internet], available from <https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/get-to-know-your-phone-rights-world-consumer-rights-day-2014> [accessed 7 October 2015].

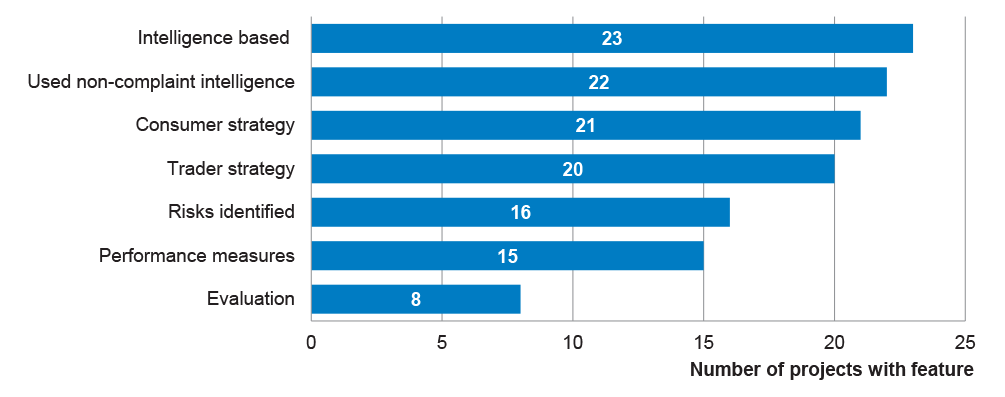

3.17 The ANAO examined all 26 projects that the ACCC commenced in 2012–13, 2013–14 and 2014–15. The ANAO examined whether they contained features that would be expected in such compliance projects, including if the projects: were based on information and intelligence (including from sources other than complaints); contained consumer and trader strategies; identified risks; contained performance indicators; and were subject to formal evaluation. The results are set out in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5: Key features of ACCC compliance projects, 2012–13 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC data regarding 26 compliance projects.

3.18 Figure 3.5 indicates that project teams were consistent in: outlining what intelligence was used (88 per cent), drawing on information sources other than ACCC complaints (85 per cent), and proposing a consumer strategy (81 per cent). However, only 62 per cent of projects identified risks. To better manage project risks, the project teams should identify risks more consistently, and also advise management whether or not risks had materialised and if so how they were addressed.

3.19 It was less common for projects to specify performance measures (58 per cent) or to be subject to formal evaluation (31 per cent). Including performance measures and undertaking evaluations are important for determining whether projects have achieved their objectives. The results of the eight evaluations undertaken for compliance projects are outlined in Table 3.4 and show that six projects had positive results and two projects had mixed results. While some projects and strategies, such as the mobile networks project, contributed to a reduction in complaints and an improvement in information provided by traders to consumers, others had outcomes that were more difficult to measure, although providing some ‘lessons learnt’ for ACCC staff.

Table 3.4: Projects subject to evaluation, 2012–13 to 2014–15

|

Project |

Results |

Evaluation findings |

|

Consumer guarantees |

Mixed |

|

|

Door-to-door energy |

Positive |

|

|

Fake online reviews |

Positive |

|

|

Mobile networks: coverage and performance issues |

Positive |

|

|

Carbon tax repeal |

Positive |

|

|

Indigenous consumers |

Mixed |

|

|

Fraud Week 2014 and 2015 |

Positive |

|

|

Small business education campaign |

Positive |

|

Note: The first six projects were a combination of education and enforcement, while the last two projects were solely educational campaigns.

Source: ANAO analysis of ACCC information.

3.20 In April 2015, the Consumer, Small Business and Product Safety Division undertook a Program Evaluation Model Project. The Division noted that it had identified an emerging business need to have objective tools for better understanding the effectiveness and impact of its business compliance and consumer education work, and to evaluate and report on its programs. While evaluations can be resource intensive, the development of evaluation tools and their regular use should help the ACCC better understand the impact of its activities.

Are consumers and businesses sufficiently aware of the ACCC’s fair trading responsibilities and activities?

In the ACCC’s most recent Consumer and Small Business Perceptions Survey, most consumers and many businesses felt that they did not need to know what the ACCC was doing until there was a problem that affected them personally, at which time they expected to be able to find out more about the ACCC’s roles. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of respondents wanted to know more about the work of the ACCC, indicating scope for the ACCC to increase the awareness of consumers and traders about where to get advice about their fair trading rights and obligations.

3.21 For the ACCC to effectively promote voluntary compliance, it is important that consumers and businesses: are aware of the ACCC and its role; know where to access detailed information about their fair trading rights and obligations; and have a general understanding of those rights and obligations.

3.22 To inform understanding of its performance, the ACCC commissions periodic surveys of the perceptions of consumers and small businesses. The most recent survey was conducted in 2014–15, with results relating to overall knowledge of the ACCC’s responsibilities. The survey indicated that 86 per cent of consumers surveyed had some knowledge of the ACCC, with 69 per cent knowing a little and 17 per cent knowing a lot. In this regard, most consumers and many businesses felt that they did not have an in-depth understanding of the ACCC’s roles. However, for many participants, this was not of particular concern, so long as the ACCC was operating and doing as it should ‘in the background’. That is, participants felt that they largely did not need to know what the ACCC was doing, until there was a problem that affected them personally. Then, there was an expectation that they would be able to find out more about the ACCC’s roles should they require it.

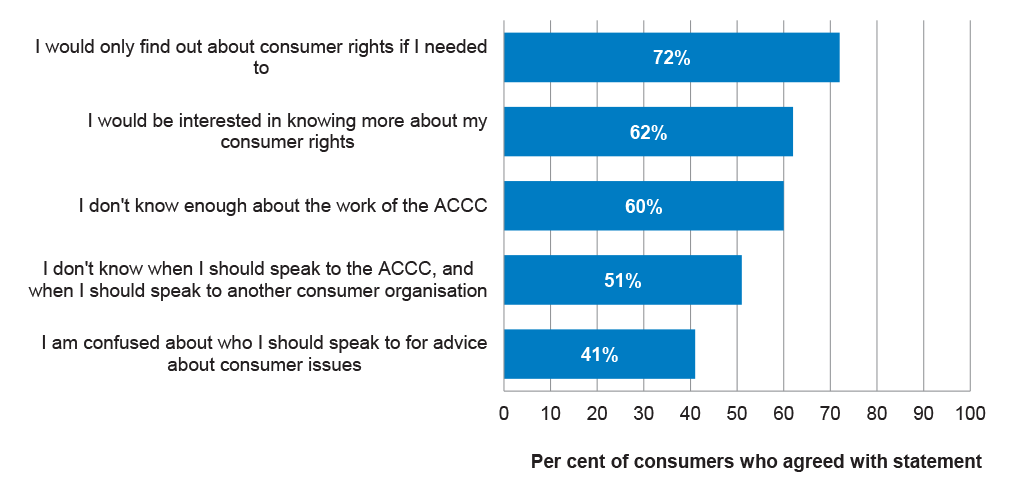

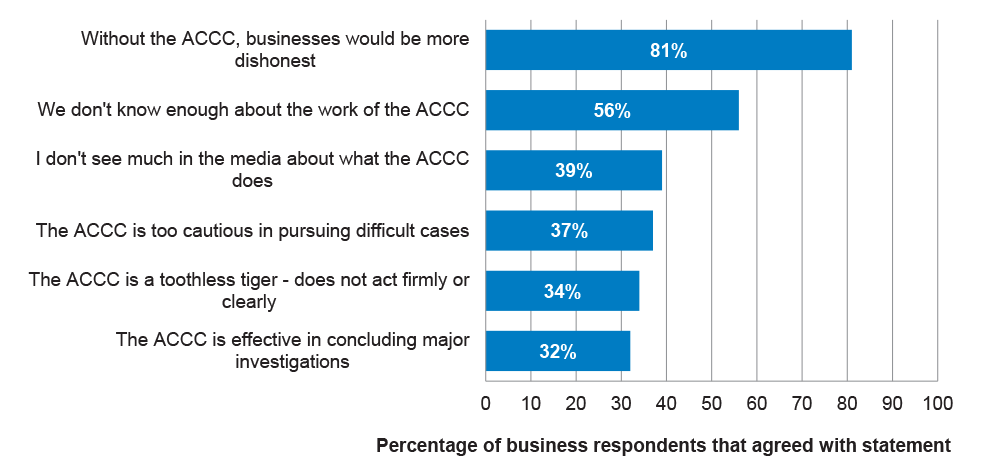

3.23 Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 3.6, a significant proportion of respondents either wanted to know more about their consumer rights, did not know enough about the work of the ACCC, or were unsure when they should speak to the ACCC or to another consumer organisation.

Figure 3.6: Awareness of consumer rights and how to get help with consumer issues

Source: ACCC Consumer and Small Business Perceptions Survey 2014–15: Full Report, June 2015.

3.24 Consistent with these latter findings, the survey report made 12 recommendations aimed at improving perceptions of the ACCC. These included further promoting its roles and responsibilities (and its enforcement ‘wins’), and providing clearer guidance to businesses and consumers about which organisation to approach in particular circumstances (in conjunction with other state and territory regulators). Implementing these recommendations may help to increase the awareness of consumers and traders about where to get advice about their rights and obligations.

4. Managing complaints of non-compliance

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the ACCC’s arrangements for managing complaints from consumers about non-compliance by traders with fair trading obligations. As part of this assessment the ANAO reviewed data and records from the ACCC’s Infocentre and the ACCC’s complaints database.

Conclusion

Although consumer complaints are one of the ACCC’s main sources of information for the purpose of planning and targeting regulatory activities, there is scope to improve the speed and quality of receiving and responding to complaints, and the accuracy of recording the subject and nature of the complaint. There is also considerable scope to improve call handling quality assurance processes, including the consistency of their application to in-house and outsource staff.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving the quality of complaints data, including the identification of vulnerable and disadvantaged complainants. The ANAO has also suggested that the ACCC review the current practices for undertaking quality assurance assessments (paragraph 4.10).

Does the ACCC have effective arrangements for receiving and responding to complaints from consumers?

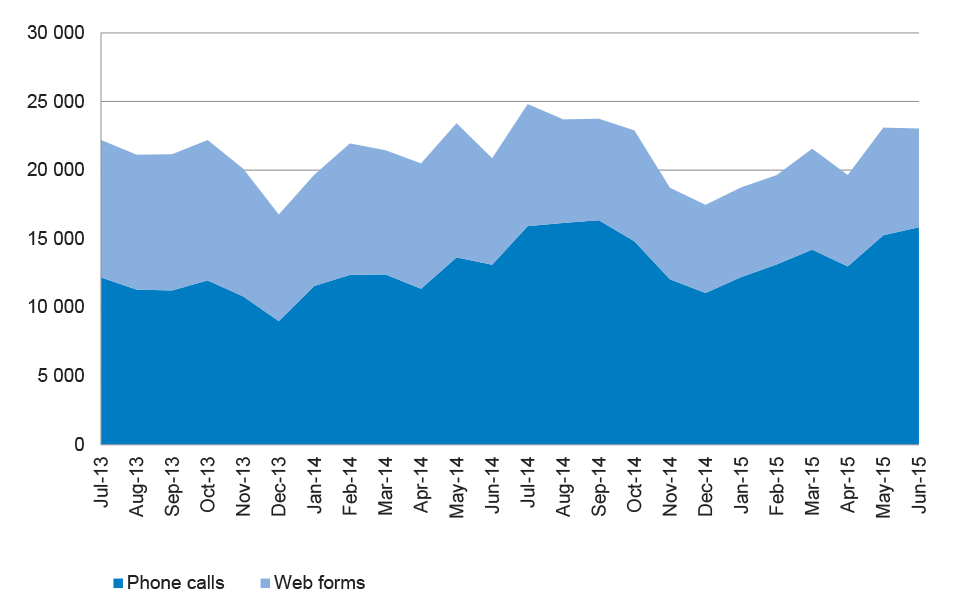

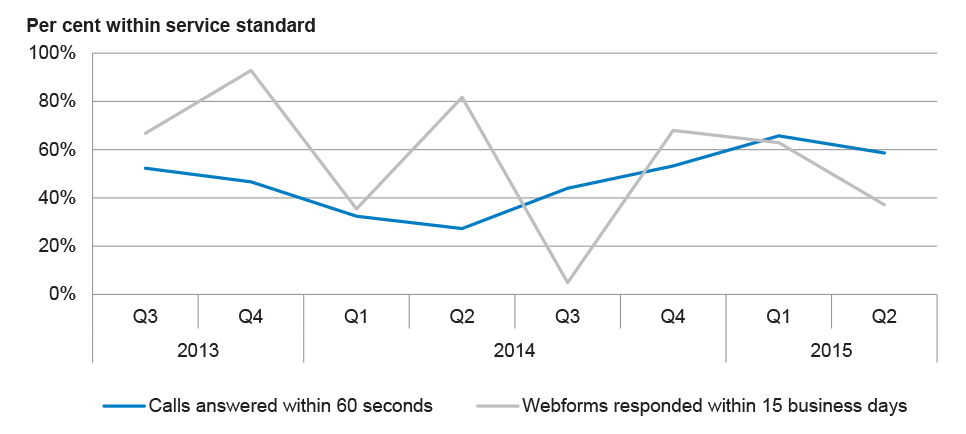

The ACCC does not have fully effective arrangements to receive and respond to complaints as it has not consistently met the service standards outlined in its Service Charter, and quality assurance checks indicate low levels of quality in answering calls. Only 48 per cent of recent calls were answered within 60 seconds (against a target of 60 per cent) and 56 per cent of web forms were responded to within the target of 15 business days.