Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Managing Australian Aid to Vanuatu

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s management of Australian aid to Vanuatu.

Summary

Introduction

1. The purpose of the Australian Government’s overseas aid program is to promote Australia’s national interests through contributing to economic growth and poverty reduction.1 Australia’s aid program focuses on the Indian Ocean Asia Pacific region, while also providing assistance to countries in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for administering the Australian aid program. Australia’s total Official Development Assistance (ODA) is budgeted at $5.32 billion in 2014–15.

2. The aid program is delivered within the context of a new aid framework, released in June 2014. Australian aid: promoting prosperity, reducing poverty, enhancing stability outlines Australia’s aid policy, describing the purpose of the aid program and Australia’s aid investment priorities. Making Performance Count: enhancing the accountability and effectiveness of Australian Aid provides the framework against which the performance of the aid program is assessed.

Context and development challenges

3. Delivering aid programs in any developing country is challenging, with inherent risks. The development environment exists within the context of often competing political and implementation objectives. It may also take considerable time for the benefits from aid programs to be realised and the number of variables affecting the programs and the environment within which they are delivered may make the assessment of impact difficult. Often Australia’s role is limited to influencing and encouraging change rather than direct program management.

4. While Vanuatu is viewed by many Australians as a holiday destination, it is a developing country and implementing successful development initiatives can be challenging. Vanuatu was ranked 131 (of 187 countries; with a value of 0.616) on the Human Development Index in 20132, its progress towards the Millennium Development Goals3 is mixed and it is unlikely to meet most of the targets by 2015. One of the country’s challenges is maintaining political stability, and one third of its population lack access to multiple basic services, such as education, health services and safe water.

5. Vanuatu is a culturally diverse country. The geography of Vanuatu means that the small population of approximately 250 000 ni-Vanuatu (people from Vanuatu) is dispersed over 65 of the country’s 83 islands and speak 113 distinct languages and numerous dialects. Vanuatu lacks natural resources that could contribute to revenue generation, except for tourism, and the formal economy is small. Infrastructure on many of the islands is very limited, resulting in difficulties in travel, communication and disbursement of funds. Political instability and the operational and management capacity of the Government of the Republic of Vanuatu (GoV) contribute to a difficult delivery environment. In addition, the state has limited reach outside of the capital, Port Vila. Vanuatu has a strong kastom system4 and chiefs, as well as island and family allegiances, play an important role in all aspects of society.

Tropical Cyclone Pam

6. On 13 and 14 March 2015, Tropical Cyclone Pam passed over Vanuatu. The category five cyclone is the most powerful on record to have impacted Vanuatu and is considered to be the worst natural disaster in the country’s history. It claimed lives and caused extensive damage across the country. In response, Australia provided a package of assistance that included: funding to Australian non-government organisations, the Australian Red Cross and United Nations organisations; deployment of humanitarian supplies and specialist equipment; and deployment of specialist personnel. The cyclone will result in changes to the development environment and, consequently, will impact on Australia’s investment in aid programs in Vanuatu.

Australian aid investment in Vanuatu

7. Australia is the largest donor of aid to Vanuatu, providing around half of total aid. In 2014–15, the budget for Australian ODA to Vanuatu is $60.4 million, the majority of which ($41.9 million) is bilateral aid managed by DFAT.5 The remaining ODA to Vanuatu is managed by other government departments or is delivered through DFAT’s regional or global programs. In 2014–15 bilateral aid is allocated across the program’s strategic objectives as follows:

- education—$11.2 million (26.8 per cent of bilateral ODA);

- health—$4.1 million (9.8 per cent);

- economic governance—$4.7 million (11.3 per cent);

- infrastructure—$13.0 million (31.1 per cent);

- law and justice—$5.6 million (13.3 per cent); and

- disaster response—$10 000 (0.0 per cent).6

8. In 2013–14, Australia had 15 aid investments operating in these six areas. The four largest investments are: Education Support Program ($39.3 million over five years to June 2017), Transport Sector Support Program ($27.0 million over four years to June 2016), Port Vila Urban Development Project ($26.5 million over five years to June 2017) and Health Sector Support Program ($26.0 million over six years to March 2016).

Audit objective and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s management of Australian aid to Vanuatu.

10. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- a sound strategic approach to planning Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu has been developed and effectively implemented;

- Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu are effectively managed, monitored and evaluated; and

- administrative arrangements facilitate the cohesive delivery of Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu.

11. When undertaking this audit, the ANAO carried out fieldwork in Canberra and three islands in Vanuatu (Efate, Malekula and Tanna). The audit focused on Australia’s bilateral program in Vanuatu. The audit team examined the following five initiatives in detail:

- Vanuatu Education Support Program (VESP);

- Vanuatu Transport Sector Support Program (VTSSP) Phase 2;

- Port Vila Urban Development Project (PVUDP);

- Vanuatu Health Sector Program (Health); and

- Vanuatu Women’s Centre (VWC) Phase 6.

12. The audit examined Australia’s investment in aid programs in Vanuatu before Tropical Cyclone Pam. The audit did not assess Australia’s aid program in Vanuatu following the cyclone or Australia’s response to the cyclone.

Overall conclusion

13. The Republic of Vanuatu, a tropical holiday destination for many Australians, is a developing country struggling with poverty and a lack of access to many basic services, including education and health services. Australia has been providing development assistance to Vanuatu for 40 years, including $60.4 million in 2013–14.7 Managing development programs is challenging, with inherent risks. Aid delivery may be impacted by competing political and implementation objectives, it may take a long time for benefits to be realised, and those benefits may be difficult to quantify. In 2013–14, DFAT assessed the performance of the Vanuatu aid program against the five strategic objectives that were current at the time8, and reported that progress was as expected in three areas but was somewhat less than expected in two areas. The strategic objectives of the program are presently being reconsidered. Against this background, DFAT’s management of the Australian aid program in Vanuatu has been generally effective.

14. DFAT’s new Aid Investment Plan for Vanuatu, currently in draft, is consistent with Australia’s aid policy and the priorities of the Government of Vanuatu as well as being sufficiently detailed to provide an understanding of the key elements of the program. DFAT has a well-defined process for designing individual aid initiatives, and investment designs are generally comprehensive. Also, DFAT has developed and maintained good relationships with key stakeholders, including representatives of the Vanuatu Government but acknowledges that mapping the large number of stakeholders and development programs being undertaken in Vanuatu would assist it to identify program gaps and overlaps, and guide the development and maintenance of key stakeholder relationships. There is, however, scope to strengthen DFAT’s approach to planning and managing the program in some areas, principally its management of risk, and the monitoring and oversight of individual initiatives.

15. The management of risks would be improved if the assessment of significant risks, as well as risk treatments, responsibilities and timeframes, were appropriately documented. In relation to the oversight of individual initiatives, DFAT currently adopts a variety of monitoring and evaluating approaches, including visits, progress reporting and mid-term reviews. Documenting its approach in a monitoring and evaluation plan specific to each aid initiative would assist DFAT to improve its monitoring of the performance of delivery partners, as well as the progress of each initiative. There would also be benefit in DFAT developing, as part of the Aid Investment Plan process, performance indicators that allow it to measure and publicly report on the extent to which its objectives are being achieved.

16. To assist DFAT to improve its management of the Australian aid program in Vanuatu, the ANAO has made two recommendations relating to DFAT’s strategic approach to aid investment planning and management, and its monitoring and oversight of individual initiatives.

17. The ANAO recognises that, following Tropical Cyclone Pam, Australia’s aid program in Vanuatu will change in response to the needs of the Government of Vanuatu and the population as they rebuild after the cyclone. The findings and recommendations from this audit remain relevant for DFAT’s ongoing management of Australia’s aid investments and, specifically, to the Vanuatu program as it develops and changes in the post-cyclone environment.

Key findings by chapter

Planning the Vanuatu Aid Program (Chapter 2)

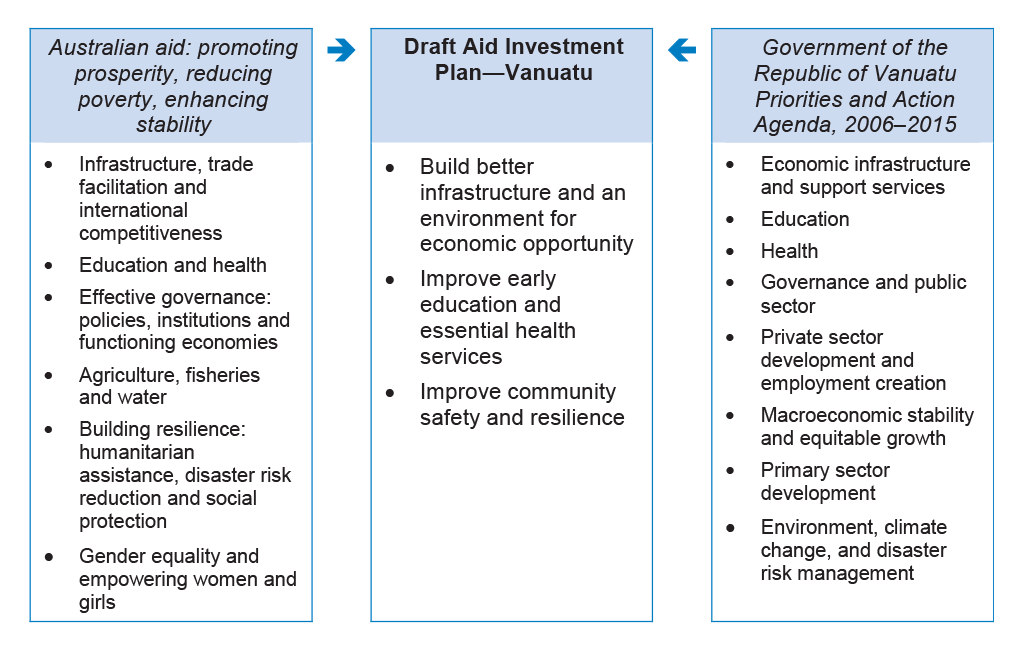

18. DFAT is currently drafting an Aid Investment Plan (AIP) for Vanuatu that covers the period 2014–15 to 2017–18 and describes the strategic priorities and rationale for aid investment in Vanuatu, and the mutual obligations of the Australian and Vanuatu Governments. The strategic direction embodied in the draft AIP for the Vanuatu aid program is consistent with the Australian Government’s new aid policy. Australia’s development priorities in Vanuatu are also generally consistent with Vanuatu’s policy agenda. At the level of individual aid initiatives, the objectives and priorities of the five initiatives examined, while more narrowly focused, are in line with the broader priorities of Australia’s aid program and the Government of Vanuatu (GoV).

19. The draft AIP meets the requirements of DFAT’s Aid Programming Guide, and is sufficiently detailed to provide an understanding of the key elements of Australia’s aid program in Vanuatu. However, the program’s performance indicators, described as performance benchmarks in the Aid Program Performance Report, measure only a small portion of the Vanuatu aid program for a period of one year. DFAT has an opportunity to create a broader framework for measuring the success of the Vanuatu aid program by developing performance indicators and targets, to be included in the AIP, that better reflect the Vanuatu aid program’s objectives and provide a firm basis for assessing progress against those objectives.

20. DFAT staff have developed good individual relationships with external stakeholders, including within the GoV, and actively participate at key meetings, such as program steering committees. Stakeholders advised the ANAO that DFAT staff were open, accessible and responsive. However, at present, stakeholder management is largely the responsibility of the DFAT officer managing an initiative. As such, there is a risk that relationships with stakeholders will be adversely impacted by changes in staff within DFAT, the GoV or other stakeholders. Developing a more structured approach to stakeholder management, in the context of finalising the AIP, including mapping the large number of stakeholders and development programs being undertaken in Vanuatu, would help to mitigate this risk and guide the development and maintenance of key stakeholder relationships. It would also allow DFAT to identify program gaps and overlaps.

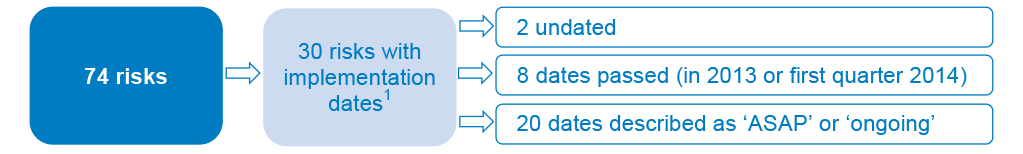

21. The Vanuatu aid program risk register, including the individual risk registers relevant to the five initiatives reviewed, was updated in April 2015. Despite a requirement to update risk registers bi-annually, prior to the recent update the register not been reviewed since November 2013. The latest iteration of the register includes 74 risks. However, the majority of implementation dates for risk treatments are not specific. Of the 30 risks with risk treatment implementation dates, 20 are described as ‘ASAP’ or ‘ongoing’. Moreover, the risk treatment implementation dates for eight risks have passed and the treatments for two of the risks do not have implementation dates. In addition, 10 of the 14 whole-of-program risks do not include an assessment of the acceptability of the current risk rating, despite a risk rating of high or very high for seven of the 10 risks, or identified possible risk treatments for these risks. The registers do not include risks to aid management, such as the impact of changes in aid policy, budget or resourcing. In some cases responsibility for implementing risk mitigation strategies is not specific and there is also inconsistency across the registers with respect to assigning responsibilities.

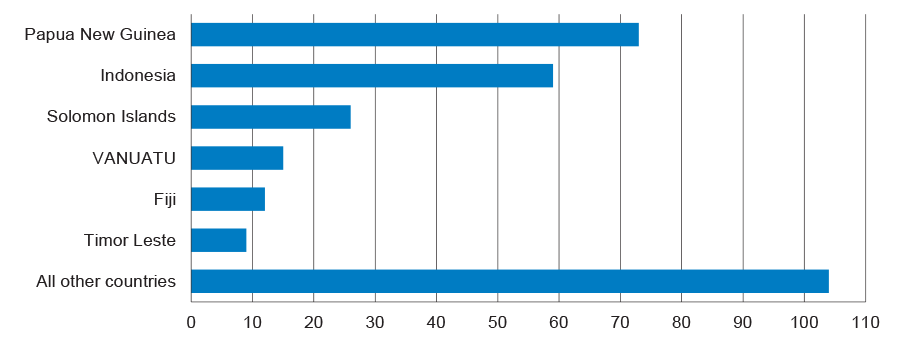

22. The post and sector/investment risk registers include fraud as a key risk. In terms of potential financial loss, DFAT reports that external fraud in the Vanuatu aid program is low, but the number of new cases reported in Vanuatu regularly places the program in the top six country programs with the highest incidence of reported fraud. Of the total 1280 fraud cases recorded by DFAT since 2009, 48 (3.75 per cent) were in Vanuatu. DFAT estimates the value (actual or potential financial loss) of the 48 cases is $102 831.

Designing Aid Initiatives (Chapter 3)

23. DFAT has a well-defined process for designing aid initiatives that includes concept notes, design documents, peer reviews and consultation with a range of stakeholders. The design and strategy documents resulting from the design process are comprehensive, include a rationale for the project and a consideration of value-for-money, and comply with the intention of DFAT’s guidance and Investment Design Quality Criteria. However, the design of the Port Vila Urban Development Project (PVUDP) did not follow the standard process. A concept document was not developed, and the technical design is ongoing, three years after commencing the project.

24. More than 50 per cent of bilateral aid to Vanuatu was channelled through GoV systems, including the majority of aid funding in the education and health sectors, by the end of 2012. In 2013, DFAT undertook assessments of public financial management systems at the national and sector levels in Vanuatu to inform the extent to which aid might be provided through partner government systems in the future.9

25. In response to the assessments in the education and health sectors, which resulted in similar findings, different aid management models have been implemented in each of the sectors. A managing contractor has been engaged to manage the majority of Australian aid funds in the education sector, while, in the health sector, DFAT continues to deliver a significant portion of the program through government systems. A mixed approach has been adopted for the Vanuatu Transport Sector Support Program (VTSSP) Phase 2, with 58 per cent of Australian funding provided through government systems and 42 per cent paid to the contractor. Nevertheless, the Vanuatu Education Support Program (VESP) and VTSSP Phase 2 agreement and contracts, which were signed after the public financial management assessments were undertaken, do incorporate increased fiduciary controls, including arrangements to oversight the management of donor funds.

26. While the design process is reasonably comprehensive and DFAT adhered to the required process for developing designs, there are limitations to the process as it relates to monitoring and evaluation frameworks and risk management plans. For example, frameworks against which investments will be monitored and evaluated are developed after an investment has been approved, are usually a contract deliverable for the delivery partners, and are not always timely. The monitoring and evaluation plan for VESP, for instance, was due in February 2014, but was not completed until December 2014.

27. In addition, poor design can impact on the successful implementation of a project. The design of the Vanuatu Education Road Map (VERM) program was overly ambitious and placed too much reliance on the GoV to effectively implement the program. Consequently, the results of VERM were not commensurate with expectations and the level of investment, that is, the program was not considered by DFAT to be value-for-money. With respect to VTSSP, the Phase 2 design was predicated on assumptions and baseline information concerning road quality and lengths achieved in Phase 1 that were subsequently found to be inaccurate. The VTSSP Phase 2 tender documents and contract were based on the flawed assumptions and data inaccuracies contained in the design document. As a result, after one and a half phases of the project, there is ongoing discussion between the stakeholders, including the GoV, DFAT and the contractor, about the required quality of roads to be rehabilitated under the program.

28. In 2014, DFAT streamlined the design process to some extent. There are opportunities, however, to further improve the process, particularly for established, mature or straightforward initiatives. The Vanuatu Women’s Centre, for example, is a successful program that Australia has been supporting since 1994 and is now in the sixth phase of funding. Future designs for such a mature program could be simplified, reducing the time and resources dedicated to the process.

Monitoring Progress and Evaluating Performance (Chapter 4)

29. DFAT adopts a variety of methods to monitor the performance of delivery partners, including: conducting monitoring visits; requiring reports on performance; undertaking annual Aid Quality Checks; and conducting periodic evaluations. Some of these approaches are incorporated into agreements with delivery partners, and include requirements for accountability and reporting. However, DFAT has not documented its approach to monitoring and evaluation in a plan (for each initiative) as part of its ongoing management of the initiatives. Developing initiative plans that focus on DFAT’s management and monitoring of the performance of delivery partners, as well as the progress of the initiative, would assist DFAT to take a more risk-based approach to monitoring.

30. While DFAT staff in Vanuatu are now encouraged to undertake monitoring visits, and have been provided with training and tools to assist with these visits, only a limited number of visits have been undertaken to date. Progress reporting is a feature of four of the five initiatives. Generally, the progress reports were of a satisfactory quality, provided an appropriate level of detail about progress and issues, and met DFAT’s monitoring and evaluation requirements. Each of the initiatives is also subject to an annual financial audit. Audits have been completed in each of the five programs, but have not always been completed in a timely manner.

31. DFAT assessed annually the quality of the implementation of each investment (now referred to as Aid Quality Checks) as required. The resulting reports provided a sound overview of the status of each initiative and included actions that DFAT intended to take to address issues. The actions covered a continuum from high to low priority and from simple to complex requirements. However, DFAT has not addressed or completed many of the actions identified.10 DFAT also requires the performance of advisors and contractors to be assessed annually. In 2013–14, only one of the five required contractor performance assessments for the Vanuatu bilateral program was completed.

32. DFAT has responded to issues identified as a result of its monitoring of aid investments. For example, DFAT and its donor partners were sufficiently informed to be concerned about the implementation and progress of VERM, implementing actions to minimise the risk to donor funds while redesigning the program. With respect to PVUDP, by January 2015 the initiative was reported to be 26 months behind schedule. DFAT raised its concerns about the progress of PVUDP with its delivery partner, the Asian Development Bank, on several occasions, encouraging the Bank to increase its presence in Vanuatu in order to more effectively monitor progress. However, issues have not always been highlighted through monitoring processes. Weaknesses in DFAT’s monitoring of VTSSP Phase 1 were not known until Phase 2, and DFAT was not aware of these discrepancies until notified by the contractor.

Administrative Arrangements (Chapter 5)

33. Responsibility for the Vanuatu bilateral aid program is shared between DFAT staff in Canberra, Australia, and at the Australian High Commission in Port Vila, Vanuatu. The roles of the Canberra and Vanuatu teams are well understood by all parties and there is frequent communication between the two teams about upcoming activities and the status of current projects.

34. The majority of Australian-based aid officers located in Vanuatu did not feel that they were adequately prepared for their posting to Vanuatu, particularly with respect to establishing, negotiating and managing large contracts. While one branch within DFAT’s head office is responsible for coordinating and managing learning and development, delivery of the program is decentralised and multiple areas within DFAT provide their own training courses. However, DFAT has not maintained accurate and complete records, for its Australian-based or locally engaged staff, of all training provided by each area within DFAT. Without reliable training records, it is difficult for DFAT to assess the adequacy, currency or completeness of the training undertaken by each officer.

35. DFAT’s internal reporting for management purposes is not specific to the Vanuatu bilateral aid program. Vanuatu is generally referred to on an exception basis. Nevertheless, internal reporting is sufficient to provide DFAT executive with reasonable oversight of the program. Externally, DFAT reports on the progress and performance of the Australian aid program via several channels. Aside from a section on DFAT’s website and occasional references in the Annual Report and Performance of Australian Aid, external reporting about the Vanuatu program centres on the annual Vanuatu Aid Program Performance Report. The 2013–14 report rates the Vanuatu program’s performance against its five strategic objectives as ‘amber’ for two objectives and ‘green’ for three objectives.11 The details provided in the report were soundly based, but provided without context. Additionally, the report does not provide a consolidated view of the effectiveness of the program overall. There would be benefit in DFAT developing, as part of the AIP process, performance indicators and targets that allow it to measure and publicly report on the extent to which its strategic objectives and the objective for the Vanuatu bilateral program as a whole are being achieved.

Summary of entity response

36. DFAT’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the full response at Appendix 1.

DFAT welcomes the ANAO’s findings that the Vanuatu aid program is generally effective and is consistent with Australia’s aid policy and the Vanuatu Government’s priorities. The report’s recognition of the complex and challenging operating environment in which Australia delivers aid in Vanuatu is also welcome. We are pleased that the ANAO has recognised the program’s relationship management strengths, its awareness of and compliance with DFAT’s fraud policy, the well-defined processes for designing aid initiatives and the range of methods adopted to monitor and manage performance. The ANAO has highlighted some areas requiring improvement, particularly in documenting risk and planning of monitoring and evaluation. DFAT welcomes the ANAO’s recommendations in support of these improvements and has commenced addressing the issues raised.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.41 |

To strengthen its strategic approach to aid investment planning and management, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reflects, in the Vanuatu country and investment risk register, an assessment of all significant risks and identifies and documents appropriate risk treatments, responsibilities and timeframes. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 4.53 |

To better monitor and evaluate the Vanuatu bilateral aid program, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade develops and implements a risk-based monitoring and evaluation plan for each initiative. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s response: Agreed |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides the background to Australia’s bilateral aid program in Vanuatu, including the context within which the aid program is delivered, and the audit objective and approach.

Australia’s overseas aid program

1.1 The purpose of the Australian Government’s overseas aid program is to promote Australia’s national interests through contributing to economic growth and poverty reduction.12 Australia’s aid program focuses on the Indian Ocean Asia Pacific region, while also providing assistance to countries in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) has been responsible for administering the aid program since the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) was abolished on 1 November 2013 and its functions integrated with DFAT.13 DFAT administers the program under Outcome 1:

The advancement of Australia’s international strategic, security and economic interests including through bilateral, regional and multilateral engagement on Australian Government foreign, trade and international development policy priorities.14

1.2 In 2014–15, the total budget for Outcome 1 is $5.57 billion—$4.66 billion in administered expenses and $0.91 billion in departmental expenses.15 Australia’s total Official Development Assistance (ODA)16 is budgeted at $5.32 billion in 2014–15.

1.3 The aid program is delivered within the context of a new aid framework, released in June 2014. Australian aid: promoting prosperity, reducing poverty, enhancing stability outlines Australia’s new aid policy. The policy describes the purpose of the aid program and Australia’s aid investment priorities, which are:

- infrastructure, trade facilitation and international competitiveness;

- agriculture, fisheries and water;

- effective governance: policies, institutions and functioning economies;

- education and health;

- building resilience: humanitarian assistance, disaster risk reduction and social protection; and

- gender equality and empowering women and girls.

1.4 Making Performance Count: enhancing the accountability and effectiveness of Australian Aid provides the framework against which the performance of the aid program is assessed. The framework includes 10 strategic targets, as well as requiring performance benchmarks at the country, regional and partner program level and quality systems at the project level. The 10 strategic targets are listed in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Ten strategic targets for the aid program

|

1. Promoting prosperity |

6. Delivering on commitments |

|

2. Engaging the private sector |

7. Working with the most effective partners |

|

3. Reducing poverty |

8. Ensuring value-for-money |

|

4. Empowering women and girls |

9. Increasing consolidation |

|

5. Focusing on the Indo-Pacific region |

10. Combatting corruption |

Source: ANAO representation of Commonwealth of Australia, Making Performance Count: enhancing the accountability and effectiveness of Australian, DFAT, June 2014.

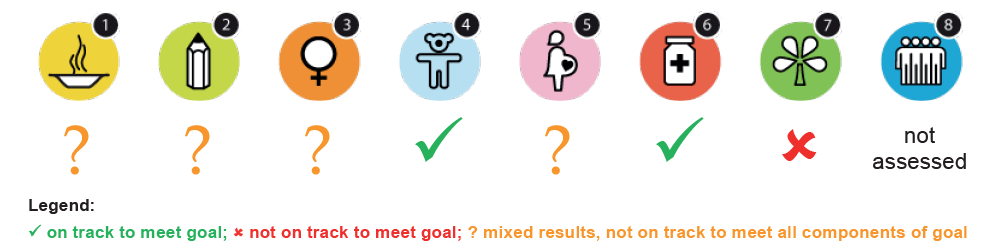

1.5 More broadly, Australia’s aid program is guided by the Millennium Development Goals. The goals are agreed targets set by the signatories to the Millennium Declaration 2000, including Australia, to reduce extreme poverty and disadvantage by 2015 (see Figure 1.2). The United Nations is currently facilitating the post-2015 development agenda, including the development of sustainable development goals for the future.

Figure 1.2: Millennium Development Goals

Source: <http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/> [accessed 16 June 2014].

1.6 The aid program is also informed by the Government’s commitment to the:

- 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness—commits donor governments and developing countries to work together to improve aid effectiveness and outlines five core principles for making aid more effective17;

- 2008 Accra Agenda for Action—seeks to strengthen and deepen implementation of the Paris Declaration; and

- 2011 Busan Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation—building on the 2005 and 2008 documents, the Busan Partnership sets out principles, commitments and actions that offer a foundation for effective co-operation in support of international development.

Australian aid to Vanuatu

Context and development challenges

1.7 The Republic of Vanuatu is an independent archipelagic nation covering over 12 000 square kilometres in the Pacific Ocean.18 The three official languages are English, French and Bislama. The population of approximately 250 000 live across 65 of the country’s 83 islands. Around 70 per cent of Ni-Vanuatu (people from Vanuatu) live in rural areas, where subsistence farming and fishing are the main sources of livelihood. However, the country is rapidly urbanising, with larger cities such as the capital Port Vila, on the island of Efate, and Luganville, on the island of Espiritu Santo, attracting people seeking education and employment opportunities.

1.8 Vanuatu has a 52-member Parliament elected for a four-year term. The head of the Government is the Prime Minister and the Constitutional Head of State is the President of the Republic. Vanuatu has a history of frequent changes of government, often as the result of no-confidence motions. Since the last national elections on 30 October 2012, the country has had three Prime Ministers. The state, however, has limited reach outside Port Vila; at the provincial and rural level customary and informal institutions exercise a greater level of influence.

1.9 The country has a stable economy, however Tropical Cyclone Pam has caused significant disruption to economic activity. In April 2015, the International Monetary Fund projected that real GDP would decline by two per cent in 2015, in contrast to the pre-cyclone forecast of about 3.5 per cent grown, and then increase to around 5 per cent in 2016.19 Vanuatu’s economic growth is driven largely by tourism and construction. Tourism and tourism-related services account for approximately 40 per cent of gross domestic product and one third of people in formal employment. Australians account for around two thirds of long-stay tourist arrivals.

1.10 Generally, designing and delivering aid programs in a developing country is challenging, with inherent risks. The development environment exists within the context of often competing political and implementation objectives. It may also take considerable time for the benefits from aid programs to realised and the number of variables affecting the programs and the environment within which they are delivered may make the assessment of impact difficult. Often Australia’s role is limited to influencing and encouraging change rather than direct program management.

1.11 While Vanuatu is viewed by many Australians as a holiday destination, it is a developing country struggling with high levels of poverty, and one third of its population lack access to multiple basic services, such as education, health services and safe water. Vanuatu was ranked 131 (of 187 countries; with a value of 0.616) on the Human Development Index20 in 2013, its progress towards the Millennium Development Goals is mixed and it is unlikely to meet most of the targets by 2015 (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3: Vanuatu’s progress towards the Millennium Development Goals

Source: Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2013 Pacific Regional MDGs Tracking Report, August 2013, p. 26.

1.12 Implementing successful development initiatives in Vanuatu can be challenging. It is a culturally diverse country. The geography of Vanuatu means that the small population are dispersed over a large number of islands and speak 113 distinct languages and numerous dialects. Vanuatu lacks natural resources that could contribute to revenue generation, except for tourism, and the formal economy is small. Infrastructure (including transport, electrical and financial) on many of the islands is very limited, resulting in difficulties in travel, communication and disbursement of funds. Political instability and the operational and management capacity of the Government of Vanuatu (GoV) contribute to a difficult delivery environment. In addition, there is a strong kastom system21 and chiefs, as well as island and family allegiances, play an important role in all aspects of society.

Australian aid investment in Vanuatu

1.13 In 2014–15, the budget for Australian ODA to Vanuatu is $60.4 million, the majority of which ($41.9 million) is bilateral aid managed by DFAT.22 The remaining ODA to Vanuatu is managed by other government departments or is delivered through DFAT’s regional or global programs. Bilateral aid is allocated across the program’s strategic objectives, as shown in Table 1.1. Appendix 3 lists Australia’s bilateral aid investments in Vanuatu in 2013–14.

Table 1.1: Allocation of bilateral aid to Vanuatu, 2013–14 and 2014–15

|

|

2013–14 allocation ($ million) |

% of country program |

2014–15 allocation ($ million) |

% of country program |

|

Education |

12.8 |

31.4 |

11.2 |

26.8 |

|

Health |

4.6 |

11.2 |

4.1 |

9.8 |

|

Economic governance |

8.8 |

21.6 |

4.7 |

11.3 |

|

Infrastructure |

8.7 |

21.4 |

13.0 |

31.1 |

|

Law and justice |

5.7 |

14.1 |

5.6 |

13.3 |

|

Disaster response |

0.04 |

0.1 |

0.01 |

0.0 |

|

Other1 |

|

|

3.3 |

7.8 |

|

|

40.6 |

100.0 |

41.9 |

100.0 |

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Aid Program Performance Report 2013–14, Vanuatu, September 2014, p. 3, and correspondence from DFAT, 10 April 2015.

Note 1: Other includes: Vanuatu Churches Partnership Program; Pacific Women’s Initiative; Vanuatu Land Program; and Won Smolbag Theatre Partnership.

1.14 Australia is the largest donor of aid to Vanuatu, providing around half of total aid to the country. Table 1.2 shows the top six donors of gross ODA to Vanuatu in 2012–13.

Table 1.2: Top six donors of aid to Vanuatu, 2012–13 average

|

|

(USD million) |

|

Australia |

59.7 |

|

New Zealand |

15.1 |

|

Japan |

11.8 |

|

EU institutions |

5.1 |

|

France |

3.8 |

|

United States |

2.4 |

Source: Vanuatu: Aid at a Glance, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

1.15 Like in many developing countries, China is an emerging donor to Vanuatu. Historically, there has been a lack of reliable data on the level or distribution of Chinese aid. However, the Lowy Institute for International Policy recently undertook a survey of Chinese-funded aid projects in the Pacific Islands, which noted that Vanuatu is attracting increased interest from Chinese companies and total Chinese aid to Vanuatu since 2006 amounts to over $200 million.23

Managing the Vanuatu aid program

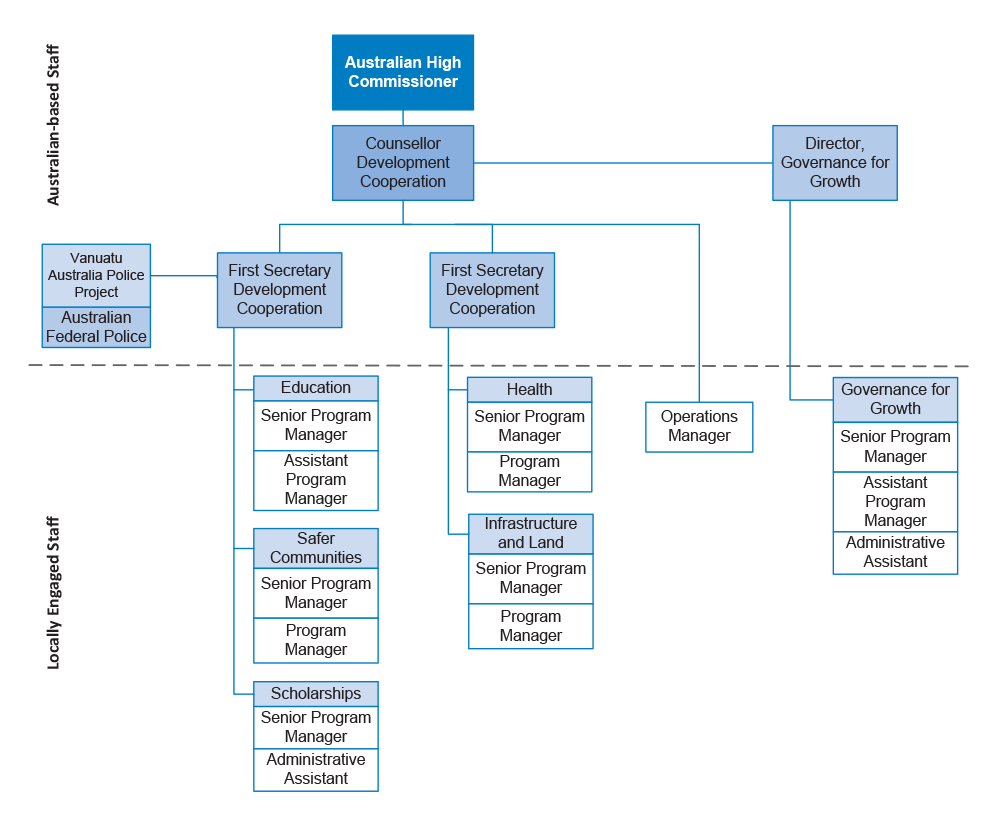

1.16 DFAT manages the aid program on behalf of the Australian Government. Responsibility for the Vanuatu bilateral aid program is shared between DFAT staff in Canberra, Australia, and at the Australian High Commission in Port Vila, Vanuatu. Generally, Canberra-based officers (collectively referred to as ‘desk’) are responsible for policy development, operational coordination with the Australian High Commission and coordination with other Australian agencies. DFAT officers in Vanuatu (collectively referred to as ‘post’) are either Australian-based or locally engaged staff and are responsible for operational delivery of the aid program.

Tropical Cyclone Pam

1.17 On 13 and 14 March 2015, Tropical Cyclone Pam passed over Vanuatu. The category five cyclone is the most powerful on record to have impacted Vanuatu and is considered to be the worst natural disaster in the country’s history. It claimed lives and caused extensive damage across the country. Reports suggest that around 70 to 80 per cent of the population was displaced, over 80 per cent of structures in the worst affected areas were damaged or destroyed, and essential infrastructure, including hospitals, roads, bridges, communications, and water and sewerage systems, sustained damage.

1.18 In response, Australia initially provided a package of assistance that included:

- funding to Australian non-government organisations, the Australian Red Cross and United Nations organisations;

- deployment of humanitarian supplies and specialist equipment; and

- deployment of personnel, including DFAT officers, medical assistance teams, and urban search and rescue assessment teams.

1.19 The cyclone will result in significant changes to the development environment in Vanuatu and, consequently will impact on Australia’s investment in aid programs. Following the cyclone it will be necessary for DFAT to evaluate the impact on the aid program and initiate the necessary changes to Australia’s investments in Vanuatu.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s management of Australian aid to Vanuatu.

1.21 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- a sound strategic approach to planning Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu has been developed and effectively implemented;

- Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu are effectively managed, monitored and evaluated; and

- administrative arrangements facilitate the cohesive delivery of Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu.

1.22 The audit focused on Australia’s bilateral program in Vanuatu. The audit team examined five initiatives in detail (see Table 1.3 and Appendix 4 for more detail about each of the initiatives). While the audit focused on DFAT’s current investments in the five areas, where necessary it also examined previous phases, including the Vanuatu Transport Sector Support Program Phase 1 and the Vanuatu Education Road Map (VERM)24, as well as requirements under the previous Direct Funding Agreement for the Health Sector Program (Health).

Table 1.3: Five initiatives examined by the ANAO

|

Investment |

Value ($ million) |

|

Vanuatu Education Support Program (VESP) |

39.3 |

|

Vanuatu Transport Sector Support Program (VTSSP) Phase 2 |

27.0 |

|

Port Vila Urban Development Project (PVUDP) |

26.5 |

|

Vanuatu Health Sector Program (Health) |

26.0 |

|

Vanuatu Women’s Centre (VWC) Phase 6 |

5.6 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT documents.

1.23 The audit examined Australia’s investment in aid programs in Vanuatu before Tropical Cyclone Pam. The audit did not assess Australia’s aid program in Vanuatu following the cyclone or Australia’s response to the cyclone. However, the findings and recommendations from this audit remain relevant for DFAT’s ongoing management of Australia’s aid investments and, specifically, to the Vanuatu program as it develops and changes in the post-cyclone environment.

Audit methodology

1.24 The audit team conducted fieldwork in Canberra and Vanuatu. The ANAO reviewed DFAT files and documentation and interviewed key DFAT personnel and relevant stakeholders, including representatives of the GoV, other donor countries, contractors, and multilateral and non-government organisations (NGOs). During its visits to Vanuatu, the audit team visited three islands (Efate, Malekula and Tanna) conducting site visits to initiatives receiving Australian aid. The fieldwork assisted the audit team to gain an appreciation of the issues facing DFAT and the impact of the environment on aid delivery, including the complexity of the relationships between all stakeholders.

1.25 This audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $472 000.

Report structure

1.26 This report comprises five chapters, as follows:

|

Background and Context |

Provided the background to Australia’s bilateral aid program in Vanuatu, including the context within which the aid program is delivered, and the audit objective and approach |

|

Planning the Vanuatu Aid Program |

Examines DFAT’s strategic approach to planning Australia’s bilateral aid investment in Vanuatu. |

|

Designing Aid Initiatives |

Examines DFAT’s approach to designing individual aid investments in Vanuatu, including the extent to which partner government systems are used to deliver aid. |

|

Monitoring Progress and Evaluating Performance |

Examines DFAT’s approach to monitoring the progress of aid investments and evaluating their outcomes. |

|

Administrative Arrangements |

Examines the administrative arrangements supporting DFAT’s management of bilateral aid to Vanuatu. |

2. Planning the Vanuatu Aid Program

This chapter examines DFAT’s strategic approach to planning Australia’s bilateral aid investment in Vanuatu.

Introduction

2.1 Australian aid to Vanuatu is delivered within the context of a complex policy and operational environment, and under the auspices of Australian government policy and agreements with the GoV. Therefore, to maximise the impact of Australian investments, a sound strategic approach is required when planning aid initiatives in Vanuatu.

2.2 To assess whether DFAT has a sound strategic approach to planning Australia’s aid investment in Vanuatu, the ANAO examined:

- the relevant policies and priorities of the Australian and Vanuatu Governments and the extent to which priorities are aligned;

- the development and content of Australia’s Aid Investment Plan for Vanuatu, including DFAT’s management of key stakeholders; and

- DFAT’s management of risk, including the risk of fraud to the aid program in Vanuatu.

Aid policies and priorities

2.3 Australia’s aid investment in Vanuatu is delivered within a complex and changing policy environment. The relationship between the Australian and Vanuatu Governments is supported by a Memorandum of Understanding and a Partnership for Development (PFD). The Memorandum of Understanding was enacted in December 2005 and outlines arrangements with respect to protocols and facilitation of Australia’s development assistance to Vanuatu. The PFD establishes the shared vision, principles and commitments of the two governments as they relate to aid and development, and provides detail about how development would be focused and measured in five specified priority areas—education, health, infrastructure, economic governance, and law and justice.

2.4 The PFD was signed in May 2009 and is out-of-date in some areas. At the March 2013 Partnership for Development Talks between the Australian and Vanuatu Governments it was agreed that the PFD would be updated, with a new version of the agreement signed by the end of 2013. As a result of the 2013 Federal Election in Australia and changes implemented by the new Government, including integration of AusAID and DFAT, this did not occur.

2.5 The Government has introduced a new approach to framing Australia’s aid program and its relationships with partner governments. Under the new approach, Aid Investment Plans (AIPs) will be developed in consultation with partner governments and will set out the direction for a country or regional program. They will be supported by a framing paper that outlines Australia’s national interest in the country or region.

2.6 DFAT has prepared the framing paper and is currently drafting the AIP for Vanuatu. The draft AIP describes the Australian Government’s initial position regarding the aid program in Vanuatu and is subject to discussion and confirmation with the GoV. The draft AIP covers the period 2014–15 to 2017–18 and describes the proposed strategic priorities and rationale for Australia’s aid investments in Vanuatu, and the proposed mutual obligations of the Australian and Vanuatu Governments.

2.7 The strategic direction embodied in the draft AIP for the Vanuatu aid program is consistent with the Australian Government’s new aid policy; that is, the draft AIP identifies three priority areas that are consistent with Australia’s investment priorities, as outlined in the aid policy (see Figure 2.1). Australia’s development priorities in Vanuatu are also generally consistent with Vanuatu’s policy agenda, as communicated in Government of the Republic of Vanuatu Priorities and Action Agenda.25

Figure 2.1: Australia’s proposed strategic priorities for the Vanuatu aid program—comparing the draft Aid Investment Plan with Australia’s aid policy and Vanuatu’s strategic priorities

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT and GoV documents.

2.8 At the level of individual aid initiatives, there should also be a clear alignment between an aid initiative and Australia’s aid policies and strategies, and the priorities of the GoV. The ANAO examined, for five initiatives, the relevant Australian and Vanuatu government policy documents and strategies, design documents, and agreements between the Australian and Vanuatu Governments and with relevant third parties. In all cases the objectives and priorities of the aid initiatives, while more narrowly focused, are in line with the broader priorities of Australia’s aid program and the GoV.

2.9 The Australian aid policy states that the aid program will invest in better quality education and that Australia’s investments in education will primarily focus on supporting changes to the systems and policies that deliver these services. The GoV’s mission, outlined in its education strategy, includes providing good quality student-centred education and a well-managed and accountable education system. Australia’s current education strategy in Vanuatu, VESP, is consistent with these goals, but is more narrowly focused on early education, specifically kindergarten to school year three. This focus is outlined in the Vanuatu AIP and is reiterated in the program design documents for VESP and relevant agreements.

2.10 With respect to infrastructure, one of GoV’s strategic priorities addresses economic infrastructure and support services, and includes objectives to ‘ensure the provision of competitively priced, quality infrastructure, utilities and services…’ and ‘ensure economic infrastructure and support services are available to other sectors’. The Australian aid policy includes a commitment to tackling infrastructure bottlenecks in the region to help create the right conditions for the private sector and to expand trade by, among other things:

- investing in infrastructure that enables private sector and human development, such as transport infrastructure and water systems; and

- working with multilateral organisations that have significant expertise in innovative solutions to deliver enabling infrastructure.

Therefore, Australia’s two infrastructure projects in Vanuatu, VTSSP and PVUDP, which focus on road transport infrastructure and urban development (including road networks, drainage and sanitation systems) are consistent with the GoV’s priorities and broader Australian policy.

Developing the Vanuatu Aid Investment Plan

2.11 The Vanuatu program is the first bilateral program to develop an AIP. The drafting process commenced in early 2014 and has been lengthy. In April 2015, DFAT advised the ANAO that it expects to commence formal consultations with the GoV in mid-2015. Following consultations, DFAT anticipates finalising the AIP and a successor partnership to the PFD by the end of 2015.

2.12 DFAT’s Aid Programming Guide (the Guide)26, issued in July 2014, contains direction for the development of AIPs, including the required contents and the approval process. As noted above, DFAT commenced drafting the Vanuatu AIP in early 2014, prior to issuing the Guide. DFAT staff working on the Vanuatu program did well to develop a draft AIP in the absence of guidance and clarity about the purpose or status of the AIP, or the process to be followed in its development.

2.13 Consistent with the Guide, the draft AIP includes commentary about Australia’s strategic priorities, proposed approaches for implementing aid investments, the mutual obligations agreed to by the Australian and Vanuatu Governments, program management and monitoring arrangements, and the performance indicators and targets (described as ‘performance benchmarks’), that will be used to assess progress against the strategic objectives. The appendices to the final AIP are expected to include an outline of program funding, future investment evaluations, a risk register and a performance assessment framework. Generally, the draft AIP (as at November 2014) meets the requirements of the Guide, and is sufficiently detailed to provide an understanding of the key elements of Australian’s aid program in Vanuatu.

2.14 The final AIP is expected to also include performance indicators (or benchmarks), to be developed in consultation with the GoV, and is anticipated to include targets for a five year period. When developing the performance benchmarks, it will be important that they reflect the Vanuatu aid program’s objectives and provide a firm basis for assessing progress against those objectives. As mentioned above, the current partnership agreement between Australia and Vanuatu, the PFD, is out-of-date in some areas, including the performance benchmarks and targets. For example, the PFD pre-dates a key infrastructure project, the PVUDP, and includes targets for infrastructure projects until June 2012. Agreed outcomes for the future are discussed during annual PFD talks between the Australian and Vanuatu Governments and benchmarks are included in the annual Aid Program Performance Report (APPR), but these focus on targets for the following year only (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: 2014–15 performance benchmarks

|

Objective |

2014–15 Benchmark |

|

Develop essential infrastructure |

100 kilometres of maintenance and rehabilitation works completed on target rural roads |

|

Progress reform on economic governance |

3000 bank accounts opened |

|

Support increased access to skills and knowledge |

80 per cent (of 800 participants) report higher income |

|

Support improved quality education |

Monitoring tool for literacy and numeracy developed and trialled |

|

Strengthen health services |

30 nurses and midwives trained |

|

More effective legal institutions and improved police services |

4000 women provided counselling and legal support |

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Aid Program Performance Report 2013–14, Vanuatu, September 2014, p. 20.

2.15 While relevant, the benchmarks in the APPR measure only a small portion of the Vanuatu aid program for a limited period of time. For example, the only benchmark addressing education relates to the development of a monitoring tool. Assessing performance against this benchmark will not provide a complete picture of progress towards the achievement of the objective to ‘support increased access to and quality of education for all boys and girls, and equip them with skills and knowledge’.27 Similarly, the health objective is to ‘strengthen health services and accelerate progress towards health MDGs’.28 The only health benchmark is limited to measuring the number of nurses and midwives trained annually.

2.16 DFAT has informed the ANAO that performance benchmarks are not intended to capture the entire aid program. However, when developing performance indicators and targets to be included in the AIP, DFAT’s has an opportunity to develop a broader framework for measuring the success of the Vanuatu aid program. Comprehensive and up-to-date performance indicators that reflect the program’s objectives would provide a firm basis for assessing progress against the objectives, and should be consistent with the benchmarks and targets approved in investment design documents and agreements with GoV and other contractors.

Strategic stakeholder management

2.17 Effective stakeholder management is an essential element in the strategic planning and management of an aid program. In practice, building and maintaining relationships and networks is largely the responsibility of the DFAT officer managing an initiative and the effectiveness of relationships is reliant on the skills, knowledge and attitude of that individual.

2.18 Generally, DFAT staff have developed productive relationships with stakeholders, including the GoV and its donor and delivery partners, and actively participate at key meetings, such as program steering committees. Stakeholders advised the ANAO that DFAT staff were open, accessible and responsive.29 However, as stakeholder management is dependent upon the individual, there is a risk that relationships with stakeholders will be adversely impacted by changes in staff within DFAT, GoV or other stakeholders. When an experienced DFAT program manager, who has invested time building relationships with GoV or other agency representatives, changes role or leaves the office, maintenance of those relationships is dependent upon effective personnel transition arrangements. However, this does not always occur.30 For an officer new to a sector, it takes time to build relationships, networks and the depth of knowledge necessary to effectively manage Australia’s aid investments. Changes in DFAT staff in Vanuatu can also change the dynamics between DFAT and partner governments.

2.19 As the largest donor in Vanuatu, Australia also has a responsibility to take a leading role with fellow donors and delivery partners. DFAT participates in, and at times leads, donor coordination meetings within relevant sectors, including health and education and is in regular, even daily, contact with delivery partners. Also, in October 2014 DFAT reinstated meetings with team leaders implementing Australian aid programs (such as NGOs and private contractors). These meetings, held quarterly until late 2013, provided a forum for development partners to discuss current programs, challenges and successes, and future directions. The October 2014 meeting was the first in a year. DFAT used the meeting to inform participants about Australia’s new aid policy and performance framework—four months after the current approach was announced.

2.20 The decreasing Australian aid budget has resulted in tension with some donors on specific projects. For example, DFAT was involved in early discussions about the refurbishment of the Lepatasi International Multipurpose Wharf in Port Vila. With the refocusing of the aid program, DFAT does not have the available funds to contribute to the project and, as such, Australia’s involvement in, and funding to, the project has decreased.31 The project is being undertaken with the assistance of the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

2.21 At a sector and initiative level, aspects of stakeholder management are captured in various documents. For example, the Aid Program Risk and Fraud Management Plan 2013–14 for Vanuatu included, for each sector, an overview of key stakeholders and/or partners and how DFAT Vanuatu will engage with them about risks and risk management. The design documents for current phases of VTSSP and VWC covered the proposed programs’ consistency with existing Australian and other donor programs, and relevant key stakeholders. Similarly, the Delivery Strategy for the Vanuatu Health Sector included a table of the main agencies involved in the health sector and the programs those agencies are funding. However, relationships and the role of key stakeholders are not features of all design documents. The VESP design document, for example, does not include a similar analysis, only referencing development partners as necessary throughout the document.

2.22 In summary, on an individual basis, relationship management is a strength of the bilateral Vanuatu program. Nevertheless, a more structured approach to stakeholder management (that is periodically reviewed) would be useful for aid program management, and is particularly important in a country like Vanuatu where Australia is the lead donor and there are a large number of stakeholders, including other DFAT-managed regional and global programs. In April 2015, DFAT advised the ANAO that:

Stakeholder engagement is at the heart of the Vanuatu program’s work, and is crucial to the success of the initiatives and our broader bilateral relationship. … We agree … that capturing and documenting key relationships is important for efficient and effective delivery of any aid program. Although not required by the Aid Programming Guide, the Vanuatu aid program is taking steps to map stakeholders ahead of our AIP consultations with the Vanuatu Government and other key players.

2.23 Mapping stakeholders, including partner governments, other donors, delivery partners and internal stakeholders, as well as other aid programs operating in Vanuatu, in the context of finalising the AIP, would help to guide DFAT’s development and maintenance of effective and productive relationships with stakeholders and would inform its approach to planning and managing aid investments within Vanuatu. It would also assist DFAT to identify program gaps and overlaps and contribute to continuity in the aid program in the event of staff changes.

Strategic risk management

2.24 Effective risk management is another important factor in the successful management of an aid program. DFAT manages risk at several levels, including at the division, country and initiative level. At each of these levels, DFAT has risk management plans and/or registers that are intended to capture key risks and mitigation treatments.

Pacific Division risk management

2.25 DFAT’s Pacific Division, within which management of the Vanuatu program sits, maintains a risk register that is reviewed and updated regularly. The current register identifies 11 risks in four categories. Six of the risks apply across the division, three risks are specific to the Papua New Guinea program and two address a specific risk in each of the Nauru and Tonga programs. The risk register does not include any risks specific to Vanuatu, but does include general risks that are relevant to the Vanuatu program, including:

- delays to programming and expenditure resulting in under-expenditure;

- reduced use of evidence to inform decisions on aid management;

- failure to ensure compliance with Australian Aid’s Child Protection policy and implement controls;

- monies paid through trust accounts or partner systems not spent effectively or accountably; and

- financial loss and reputational damage due to fraud.

Vanuatu program and initiative risk management

2.26 At the country level, the Guide prescribes the minimum risk management documentation required. These are post (for example, DFAT Vanuatu) risk and fraud management plans, and country risk registers and initiative or sectoral registers.32 For individual initiatives, registers should be developed as part of the design process and identify the risks to achieving the objectives of the investment. The Guide advises that reliance on partner risk documentation is not sufficient, as partners are not in a position to assess important or relevant risks from DFAT’s perspective.

2.27 For the Vanuatu aid program, the Aid Program Risk and Fraud Management Plan 2013–14 was signed in November 2013. It covers internal and external factors that might impact on risks, key stakeholders and partners and provides a brief description of how DFAT will engage with those stakeholders on risks and risk management, and how DFAT Vanuatu will monitor risks. The plan specifically identifies fraud risks, against a standard template, and provides an indicative risk rating for each of the 16 risks.33

2.28 DFAT Vanuatu also maintains a Vanuatu risk register. In April 2015, in response to the ANAO’s preliminary audit findings, DFAT updated the risk register and addressed a number of shortcomings in the previous version. The new Vanuatu risk register includes risk registers for each of the key sectors in which the Australian aid program is operating34, as well as a new whole-of-program risk section that addresses:

- contextual risks—such as risks relating to political instability and natural disasters;

- programmatic risks— such as risks relating to financial management capacity and the non-performance of managing contactors; and

- institutional risks—such as risks relating to fraud, theft and conflict of interests.

Table 2.2 shows the distribution of the 74 risks across the individual registers.

Table 2.2: Distribution of risks in the Vanuatu risk register, as at April 2015

|

Section |

Number of risks |

|

Whole-of-program risks |

14 |

|

Education risks |

12 |

|

Law and justice risks |

14 |

|

Health risks |

5 |

|

Infrastructure risks |

24 |

|

Governance for growth risks |

5 |

|

Total |

74 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT data.

2.29 The Aid Program Risk and Fraud Management Plan states that the risk register should be updated bi-annually. However, prior to the April 2015 update, the risk register had not been reviewed since November 2013.

2.30 Weaknesses remain in the new version of the risk register. For example, the register does not consider the impact on the aid program of several strategic aid management risks, including changes in aid policy, adjustments in the bilateral aid budget, or resourcing changes. It is important that these risks are considered at the bilateral program level given their potential to impact on the effective delivery of the aid program. Furthermore, for 10 of the 14 whole-of-program risks, an assessment has not been made regarding the acceptability of the current risk rating, despite a risk rating of high or very high for seven of the 10 risks and moderate for the remaining three risks, or identified possible risk treatments for these risks. A further risk in one of the sectoral registers (education) notes that the risk is unacceptable, but the suggested risk treatment is incomplete.

2.31 As illustrated in Figure 2.2, two of the 74 risks rated as requiring treatment do not have implementation dates, the implementation dates for some risks are out-of-date and the majority of implementation dates for risk treatments are not specific.

Figure 2.2: Vanuatu risk register implementation dates

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT documents.

Note 1: The 30 risks with implementation dates include 18 risks that were described as acceptable but also included additional risk treatments.

2.32 In some cases responsibility for implementing risk mitigation strategies is not specific35 and there is also inconsistency across the registers with respect to assigning responsibilities. For example, responsibility for all the risks in the Health register are assigned to DFAT, while the majority of infrastructure risks are assigned to entities external to DFAT. While, in the latter initiative, there are contactors in place to share the responsibility for risk, DFAT is accountable for Australian aid funding and, as such, is ultimately responsible for documenting and managing risk to the aid program.

2.33 DFAT is in the process of changing its approach to risk management at the country program level. In future, post risk and fraud management plans are expected to be phased out once AIPs, which are to include consideration of risk, are in place. The Vanuatu risk register is included, as an appendix, in the draft AIP for Vanuatu.

2.34 Overall, while the April 2015 version of the Vanuatu risk register addresses a number of shortcomings identified by the ANAO in the previous iteration, weaknesses remain. There would be benefit in DFAT continuing to enhance its documentation of risk in the Vanuatu aid program by assessing all significant risks, as well as identifying and documenting risk treatments, responsibilities and timeframes.

Fraud risk

2.35 One of the key risks to the aid program is the risk of fraud, which is the subject of one of the 10 strategic performance targets identified in Making Performance Count: enhancing the accountability and effectiveness of Australian aid (Target 10: Combatting corruption). DFAT has a policy of zero tolerance of fraud or corruption and DFAT’s guidance states that all instances of suspected fraud are to be investigated. Fraud policy and the management of cases is overseen centrally by DFAT’s Audit Risk Management and Fraud Control Branch. The Guide outlines the processes for detecting, managing and reporting fraud, as well as links to additional information, including DFAT’s Fraud Policy Statement and relevant administrative circulars.

2.36 Within the Vanuatu bilateral aid program, fraud is recognised as a key risk and is incorporated into the post and sector/investment risk registers. The ANAO observed that there was a high level of awareness of fraud management procedures and responsibilities among the DFAT staff in Vanuatu. In terms of potential financial loss, known external fraud in the Vanuatu program is low, but the number of new cases reported in Vanuatu regularly places the program in the top six country programs with the highest incidence of reported fraud. Vanuatu accounted for five per cent of the 298 cases recorded by DFAT in 2013–14 (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3: Number of fraud cases, 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT documents.

2.37 During the six months to December 2014, five new cases of external fraud were reported in Vanuatu, compared with 23 cases in Indonesia, 15 in Papua New Guinea, nine in Solomon Islands, six in Cambodia, and five in Timor Leste.36 Of the total 1280 fraud cases recorded by DFAT since 2009, 48 (3.75 per cent) were in Vanuatu. DFAT estimates the value (actual or potential financial loss) of the 48 cases is $102 831. As at 31 December 2014, eight fraud cases were classified as active in the Vanuatu program, with an actual or potential value totalling $40 549.

2.38 To address the high levels of fraud in certain Pacific country programs, in September 2013 the (then) AusAID Director General issued a direction to increase fiduciary controls on funds administered through partner government systems in such countries. The direction required that Australian funds were not to be exposed to sole authority by partner government officials in these countries; that is, that all funding through partner government systems must include ex-ante review and sign off by an Australian Government delegate. In terms of the Vanuatu bilateral program, the directive was implemented in each of the five initiatives reviewed by the ANAO (if similar fiduciary controls were not already in place). For example, additional fiduciary controls regarding spending proposals and school grants were embedded in the agreement between the Australian and Vanuatu Governments for VESP and the contract with the managing contractor. During 2013, DFAT also conducted an assessment of the Vanuatu Government’s national systems and public financial management reviews in several sectors. These reviews are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 and DFAT’s response to concerns about, among other things, partner government financial management is described in Chapter 4.

Conclusion

2.39 DFAT’s development of a new Aid Investment Plan for Vanuatu is timely given the limited currency of the Partnership for Development. The draft Aid Investment Plan is consistent with the new Australian aid policy, as well as the priorities of the GoV. It was one of the first drafted and is sufficiently detailed to provide an understanding of key elements of Australia’s aid program in Vanuatu. Generally, DFAT has developed and maintained good relationships with stakeholders, participating in a variety of formal and informal meetings, and relationship management is a strength of the Vanuatu program on an individual basis. However, while risk management registers exist at several levels, including at the country and investment level, in a number respects they could be improved substantially.

2.40 The development of a new Aid Investment Plan for the Vanuatu bilateral program provides an opportunity for DFAT strengthen its strategic approach to planning Australia’s aid investment by developing performance indicators and targets for measuring progress that more completely reflect the Vanuatu aid program’s objectives. In addition, developing a more structured approach to stakeholder management, in the context of finalising the AIP, would help to guide the development and maintenance of key stakeholder relationships and identify program gaps and overlaps. While it is impossible to eliminate risk, it is important that DFAT documents how it identifies, evaluates and determines the appropriate treatment of the risks to the Vanuatu bilateral program. The management of risks would be improved if risk registers included an assessment of all significant risks, as well as appropriate risk treatments, responsibilities and timeframes.

Recommendation No.1

2.41 To strengthen its strategic approach to aid investment planning and management, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reflects, in the Vanuatu country and investment risk register, an assessment of all significant risks and identifies and documents appropriate risk treatments, responsibilities and timeframes.

DFAT’s response: Agreed.

2.42 DFAT is updating the Vanuatu country and sector risk registers; is finalising the risk matrix annex of the draft Aid Investment Plan (which, as per the Aid Programming Guide, replaces the Risk and Fraud Management Plan); has included risk as a formal standing agenda item at regular aid program staff meetings; and has nominated a staff member as ‘risk champion’ to oversee these processes and report to management on their implementation.

3. Designing Aid Initiatives

This chapter examines DFAT’s approach to designing individual aid investments in Vanuatu, including the extent to which partner government systems are used to deliver aid.

Introduction

3.1 Effective design should provide a sound basis upon which an aid investment is approved and implemented. It includes the development of appropriate design documents that set out the rationale for selecting the aid activity and whether it is considered value-for-money, the extent to which aid might be provided through partner government systems, and the basic elements for implementing the proposed activity.

3.2 The ANAO reviewed:

- DFAT’s processes for designing aid initiatives;

- key considerations such as stakeholder engagement, value-for-money, and the use of partner government systems to deliver aid;

- the limitations in the design process, including the impact of poor design; and

- potential improvements to the design process.

The design process

3.3 Aid initiatives are expected to be designed in accordance with DFAT guidance and standards.37 The key outputs of the design process are:

- investment concept—considers the development issue and rationale for investment, proposes outcomes and alternative approaches and options for delivering the intended outcomes, and provides a justification for the recommended investment; and

- investment design document—describes the purpose of the aid investment, what the investment will achieve and how it will be implemented, and forms the basis for financial approval to implement the investment initiative.

3.4 The design document must comply with the principles outlined in DFAT’s Investment Design Quality Criteria, meeting eight criteria: relevance; effectiveness; efficiency; monitoring and evaluation (M&E); sustainability; gender equality; risk management and safeguards; and innovation and private sector.38 Investment designs are expected to be subject to internal and, where relevant, external quality assurance. The form of the quality assurance may differ between investments, but should usually involve a peer review and independent appraisal of the design document. The concept may also be subject to peer review. At the time the five investments reviewed by the ANAO were designed, a Quality at Entry report was also mandatory for the majority of aid investments. This report focused on the key design quality issues and was reviewed at the design peer review meetings. Quality at Entry ratings were assigned against seven criteria.39

3.5 Of the five initiatives examined, DFAT undertook a design process and produced a design document for three—VESP, VTSSP, and VWC. For Health, DFAT produced a design strategy, which is similar to a design document and its development followed a similar process. The key stages and dates in the design of the four initiatives are shown in Table 3.1. The ongoing design of PVUDP is discussed separately in Figure 3.2.

Table 3.1: Key design stages and dates

|

Stage |

VESP1 |

VTSSP Phase 2 |

Health |

VWC Phase 6 |

|

Concept Note |

undated |

June 2011 |

|

October 2011 |

|

Concept peer review |

February 2012 |

August 2011 |

|

October 2011 |

|

Design peer review |

August 2012 |

August 2012 |

May 2010 (appraisal) |

May 2012 |

|

Quality at Entry report |

August 2012 |

September 2012 |

June 2010 |

April 2012 |

|

Investment Design Document finalised |

October 2012 |

September 2012 |

June 2010 (delivery strategy) |

June 2012 |

|

Design approved |

October 2012 |

November 2012 |

June 2010 |

June 2012 |

|

Agreement signed |

August 2013 (managing contractor) June 2014 (GoV) |

July 2013 (contractor) January 2014 (GoV) |

May 2014 (GoV) |

October 2012 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT documents.

Note 1: A design process was also undertaken for the Strengthening Early Childhood Care and Education portion of the education investment in mid-2013. The design was finalised in September 2013.

Figure 3.1: Investment Design Documents

Figure 3.2: Designing the Port Vila Urban Development Project

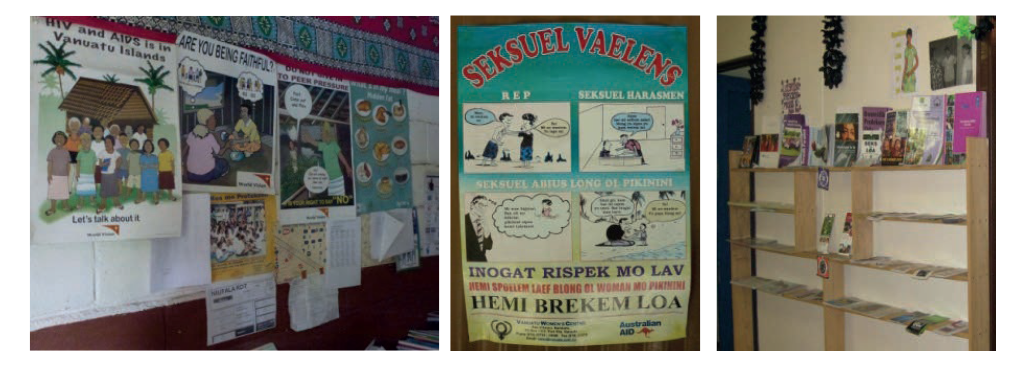

The design of PVUDP, a partner-led design, did not follow the standard process. While DFAT did not develop a concept document as required, it did prepare a Design Summary and Implementation Document, which is a requirement for partner-led aid investments designs. The document summarises the proposed project, including the outputs to be achieved and funding arrangements, as proposed in design documents drafted by Australia’s delivery partner (investment manager), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), in November 2011. This was followed by preliminary and interim design reports in April and June 2012 respectively.

As a result of the delayed signing of the financing agreements (funding agreements in relation to the project were signed in December 2012) and difficulty recruiting and positioning consultants, physical work on the road and sanitation projects had not commenced by late 2013. GoV engaged a design, supervision and capacity development consultant in September 2013. The consultant was tasked to review the technical engineering design documents, formulate quality criteria for the design and construction of road and drainage works, and prepare bid documentation and cost estimates for the rehabilitation works. The consultants have produced a number of technical design reports (a Preliminary Design Report in April 2014 and a 70% Design Review Report in August 2014) to provide stakeholders with updates about the progress of the design stage, which describe progress, key events and issues to date.

Following a review mission in January 2015, the ADB reported that the overall progress of the project is delayed by approximately 26 months and estimates that project progress remains at 13 per cent against an overall elapsed project period of 51 per cent. The delays have caused DFAT to rephase the funding. Australian investment in the PVUDP was originally $31 million—a project specific grant of $26.5m and an additional $4.5 million to be sourced from remaining monies held in an ADB managed trust fund. However, the delays and consequent rephasing mean that outlays to date have been less than anticipated.

|

|

2012–13 ($ million) |

2013–14 ($ million) |

2014–15 ($ million) |