Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the FFG Capability Upgrade

The audit follows on from Audit Report No. 45 2004-2005, Management of Selected Defence Systems Program Offices, May 2005. That report is being considered by the JCPAA, as part of its current inquiry into Defence Financial Management and Equipment Acquisition at the Department of Defence and DMO.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Defence Materiel Organisation's (DMO's) management of the $2.097 billion SEA 1390 Programme seeks to regain the original relative capability of four of the Royal Australian Navy's remaining five Guided Missile Frigates (FFGs). It is also to ensure the FFGs' associated facilities and logistics support remain effective until the FFGs are withdrawn from service between 2015 and 2021. The audit focuses on SEA 1390's Phase 2.1 - FFG Upgrade Implementation Project and Phase 4B - SM-1 Missile Replacement Project. In July 2007, these projects had approved budgets of $1.497 billion and $600 million respectively.

2. Phase 2.1's $1.497 billion budget includes an allowance for annual labour and materials price variations of $191 million and for foreign exchange variations of $194 million. These allowances reflect major Defence multi-year contract policy, which allows for variations in labour and/or material costs and foreign currency exchange rates in accordance with agreed price variation formula and indices.

3. Phase 2.1 commenced in June 1999 and its cumulative expenditure reached $1.064 billion in June 2007. Of that amount, $1.005 billion was for a variable priced Prime Contract signed on 1 June 1999 covering the design, development and integration of the FFGs' upgraded systems, and the service life extension (see Table 1). The total remaining Prime Contract budget was $208.4 million as at mid June 2007. On that basis 83 per cent of the Prime Contract Budget had been spent.

4. A Prime Contract change in mid 2006 included a six ship to four ship scope reduction flowing from the Government's decision in November 2003 to withdraw from service the oldest two FFGs, prior to their planned upgrade and life extension. This contract change also included the settlement of Prime Contractor delay claims; changes to the Project's Contract Master Schedule and milestones, and changes to the Upgraded FFGs' Provisional Acceptance from the Prime Contractor by DMO. The overall financial impact was a $54.4 million (2006 prices) reduction in the Prime Contract price.

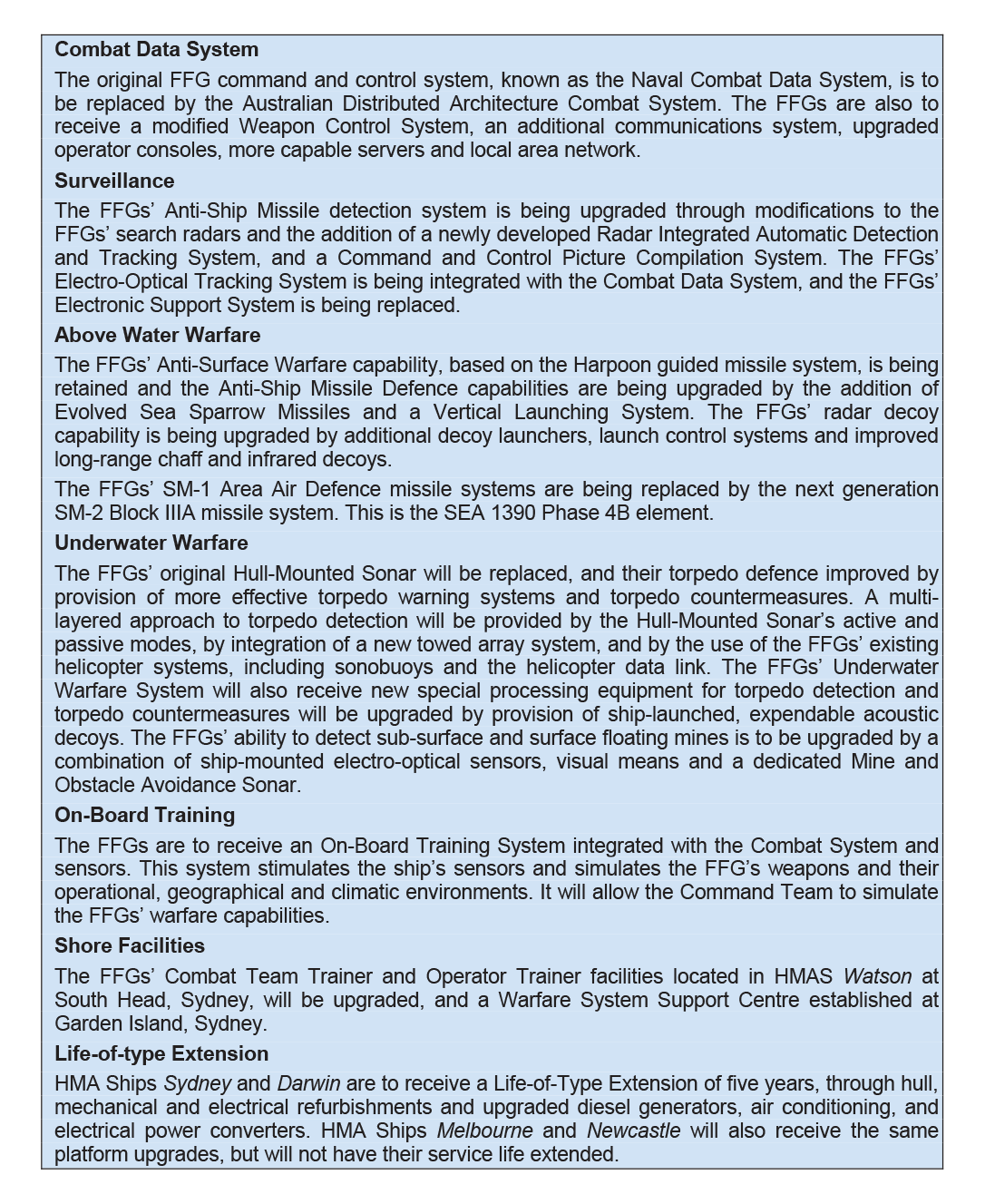

Table 1 Project SEA 1390 Phase 2.1 and Phase 4B Elements

Source: ANAO, adapted from Defence Materiel Organisation, FFG System Program Office records.

5. SEA 1390 Phase 4B has an approved budget of $600 million and is to replace the FFGs' SM-1 Area Air Defence missile system with the next generation SM-2 Block IIIA missile system. Unlike Phase 2.1, which has a Prime Contractor responsible for all systems integration tasks, Phase 4B's systems integration is being managed by DMO's FFG System Program Office (FFGSPO) with DMO's Guided Weapons Acquisition Branch responsible for acquiring the SM-2 missiles. Phase 4B's expenditure reached $85.45 million or 14 per cent of its approved budget by mid June 2007, and it was three to 18 months behind schedule on some milestones by June 2007. Phase 4B is linked to Phase 2.1, and in some respects Phase 2.1 is a precursor to the system integration and software development necessary for the delivery of Phase 4B.

SEA 1390 Phase 2.1 Prime Contract Arrangements1

6. Phase 2.1's Prime Contract (the Contract) was entered into by the parties on 1 June 1999, and it provides for the Prime Contractor to have Total Contract Performance Responsibility. Consistent with that responsibility, the Contract is structured in such a way that the Prime Contractor effectively has sole responsibility for the upgrade of each FFG from the time of each FFG's ‘Handover' until the Prime Contractor offers the FFG for Provisional Acceptance by DMO. During that period, the role of the Project Authority (FFGSPO Director) in relation to the technical aspects of the upgrade is generally limited to reviewing and commenting upon activities proposed to be conducted by the contractor.2

7. This limited role of the Project Authority relates to the original contract drafters' aim of preventing the contractor's Total Contract Performance Responsibility being diluted by more direct input from the Project Authority. In practice, this has created difficulties for the Project Authority in maintaining a sufficient degree of technical involvement, control and understanding of what is being done by the contractor so as to be satisfied, on an ongoing basis, that the FFGs and software are being upgraded in accordance with the Contract's provisions and so as to meet the Contract requirements and Navy's technical regulations.3

8. The Contract required a comprehensive inspection, test and trials programme to be implemented and maintained by the contractor. It was intended that the Project Authority would assess compliance of the supplies with the requirements of the Contract by reference to the results of the tests conducted. The Contract did not deal with the situation where (as occurred) the Project Authority was not satisfied as to the sufficiency of the test procedures proposed by the contractor to produce results that demonstrate compliance.

9. Disagreements between the parties as to the degree of testing required to demonstrate contractual compliance and a lack of design disclosure on the part of the contractor has led to the DMO refusing to approve or agree upon test procedures. Rather than these disputes being resolved through the dispute resolution mechanism provided in the Contract at that time, the contractor elected to proceed (at its own risk) with a test and trial regime outside of the Contract. By mid 2006, this had led to the situation where the upgrade of HMAS Sydney was substantially complete, and both parties required return of HMAS Sydney to the DMO, but there was a material lack of contractually compliant test data to demonstrate that Contract requirements and Navy technical regulations had been met. Instead, the DMO was being requested by the contractor to assess Contract compliance on the basis of the test results derived by the contractor by its testing outside of the Contract provisions.4

10. In October 2007 the Prime Contractor advised the ANAO that it had elected to proceed ‘at his own risk' because the Project Authority representatives were urging cessation of all activities until 100 per cent compliance was achieved across all aspects of what is a complex and confusing contract. The Prime Contractor further advised that it should be recognised for opting for such an onerous approach as the alternate would not have delivered any capability to the ADF within a reasonable timeframe. It is the Prime Contractor's opinion that its ‘pragmatic' proceed at own risk approach, was the only feasible approach in order for the Project to proceed and be completed.

11. The absence of any provisions in the Contract allowing the Project Authority to stop the contractor from proceeding down this route is at the centre of the difficulties now being faced with the return of HMAS Sydney to Initial Operational Release.5 The Contract did not adequately provide for the Project Authority to exercise the necessary degree of control required. The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that Initial Operational Release was not a concept in existence at the time of contract signature. As stated previously, the lack of alignment of the Phase 2.1 contract with Navy regulatory framework is, in part, one of the difficulties the Project Authority has regarding HMAS Sydney's Initial Operational Release.

12. In addition to these difficulties with the acceptance regime under the Contract, DMO was also required to manage the contractor's performance against the Contracted schedule. The contractor took substantially longer than the original schedule, which was re-baselined in April 2004 and May 2006. Again, the Contract did not adequately provide for the Project Authority to exercise control over the contractor's inability to meet the schedule. Other than via milestone payments, the only schedule control mechanisms available are claiming liquidated damages or terminating the Contract. DMO's legal advice was that in the circumstances that have prevailed since major delays on the part of the contractor first became apparent, neither option has really been feasible for the Project Authority.

Project delays and recent improvements

13. Overall, the April 2004 and May 2006 schedule re-baselines have deferred the delivery of all FFGs to be upgraded, with the delivery of the last ship to be upgraded delayed by four and a half years. The Department of Defence advised the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) in February 2007 that:

The effects of the upgrade delays on capability have been mitigated to an extent by the extension of HMAS Adelaide to the end of 2007 (originally planned to decommission in September 2006). Furthermore, some operational tasking that might have been undertaken by FFGs has been transferred to other classes of ship. This has remained manageable, causing minimal overall impact on Navy capability and the Surface Combatant Force Element Group (SCFEG) has met all Directed Level of Capability (DLOC) requirements. Moreover, the commissioning of new ANZAC Frigates Toowoomba and Perth in late 2005 and 2006 respectively has assisted Navy to manage capability requirements.

These aspects have attracted very careful management attention by Navy and, consequently, the FFG upgrade has not had a significant impact on fleet activity, training and personnel leave management. This close management will continue throughout the Upgrade process.

14. The Commander of Navy's Surface Combatant Force Element Group advised the ANAO in September 2007 that:

HMAS Sydney was 'Handed back' to Navy in April 2006. The hand back process allowed Navy to employ the ship in a range of activities. Navy used the ship for specialised training periods, progression of Navy continuation training, familiarisation of personnel with upgraded systems and continuation of contractor Sea Trials which enabled an improved understanding of upgraded capabilities. Of note is the availability of the platform to progress dedicated at sea Marine Technician training, which proved most valuable to the Capability Manager in managing the critical shortfalls in this personnel category.

The performance of the upgraded systems has varied. The Australian Distributed Architecture Combat System (ADACS) has shown gradual improvement, which culminated in a successful Evolved Sea Sparrow (ESSM) firing in August 2007 with Baseline Build 2 software. This has provided Navy with sufficient confidence in the system to continue with Operational Test and Evaluation trials with further ESSM firings at the Pacific Missile Range Facility near Hawaii in October 2007, subject to authorisation of a Safety Case for the evolution. Navy is confident that ADACS is on track to meet its requirements.

Performance of the C-PEARL Electronic Support System and the Underwater Warfare System has been disappointing. Performance of the Electronic Support System during sea trials has not provided Navy with the confidence that the system will meet operational requirements in the short/medium term. Electronic Support System deficiencies are the most significant barrier to Navy using HMAS Sydney in an operational environment. While Underwater Warfare System trial results have been disappointing there are some encouraging aspects. Additional Underwater Warfare System trials are planned using a sophisticated underwater range in Canada. Navy expects that the data gathered from these trials will allow ongoing development leading to an operational system in the medium term.

15. The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that it has been working collaboratively with the FFGSPO to address the operational performance issues noted during the Initial Operational Release process. It further advised that the underwater trials planned for the Lead Ship in Canada are additional trials that are outside the scope of the contract, and that the development of the Underwater Warfare System is complete. The Prime Contractor also advised that the entire upgraded Underwater Warfare System was deemed functionally compliant within the TI-338 for the delivery of HMAS Melbourne at Provisional Acceptance [8 October 2007], and accordingly, all underwater system trials on HMAS Melbourne achieved a 'Pass'.

Audit approach

16. The audit follows on from Audit Report No. 45 2004-2005, Management of Selected Defence Systems Program Offices, May 2005. That report is being considered by the JCPAA, as part of its current inquiry into Defence Financial Management and Equipment Acquisition at the Department of Defence and DMO.

17. The audit scope was a review of the performance of FFGSPO's management of the FFG Capability Upgrade Project. It focused on the delivery and acceptance of HMAS Sydney and the arrangements in place for upgrading the remaining three FFGs. The audit also included an examination of the implementation of the SM-1 Missile Replacement Project and the delays in the FFG Upgrade Project.

Conclusions

18. The FFG Upgrade Project has experienced extensive delays in meeting the contracted capability upgrade requirements specified in the late 1990s. The number of FFGs to be upgraded has been reduced from six to four, and the scheduled acceptance of the fourth and final ship has been delayed by four and a half years to June 2009. Since the last ANAO audit in 2005, the project delays are attributable to a range of Underwater Warfare System and Electronic Support System performance deficiencies. Considerable risk remains to the delivery of contractually compliant capability to Navy, given the maturity of these systems.6

19. The FFG Upgrade Prime Contract is less robust than more recent Defence contracts in terms of providing DMO with adequate opportunity to exercise suitable management authority over the project's acceptance test and evaluation programme. Nevertheless, FFGSPO has monitored the Prime Contractor's performance and provided extensive feedback aimed at achieving improved visibility into the project's engineering development, testing procedures and test results. But the overall result has been long-running design review, test programme and requirements completion verification difficulties.7

20. The DMO exercised discretion in Provisionally Accepting HMAS Sydney in December 2006 in accordance with the contract as amended by the May 2006 Deed of Settlement and Release.8 Consequently, at the time of its Provisional Acceptance in December 2006 HMAS Sydney had not achieved important Provisional Acceptance milestone precursors,9 which are now required to be resolved before the ship's Acceptance in November 2008. As at September 2007, HMAS Sydney was experiencing continuing delays in obtaining Initial Operational Release by Navy. This is attributed to limitations in the maturity of Underwater Warfare and Electronic Support Systems and supporting documentation required to satisfy Navy's technical regulations.10

21. The DMO is not well placed to exert influence over the Prime Contractor performance at this time due to the nature of the original contract, and the extent of funds already advanced. The project's liquidated damages provisions for delayed delivery are capped at less than one per cent of the contract price, and so are unlikely to provide an effective deterrent measure. The May 2006 Deed released both parties from all legal claims including liquidated damages prior to that date. DMO's election not to exercise its preserved right to seek remedies for the Prime Contractor's inability to achieve Provisional Acceptance of HMAS Sydney by 27 August 2005, has resulted in no liquidated damages being claimed by DMO as at September 2007.

22. The FFG Upgrade Project's Earned Value Management System (EVMS), which controlled some 70 per cent of payments, has been subjected to 10 revisions of the project's Contract Master Schedule by the Prime Contractor.11 The May 2006 Deed required a new Integrated Baseline Review to be undertaken by DMO to validate the most recent Contract Master Schedule change. DMO expects the Integrated Baseline Review to be completed in October 2007. The magnitude of the schedule slippage has led to DMO experiencing difficulty in determining if earned value payments were accurately tracking work performed on the project. By October 2006, the Prime Contractor had received earned value payments that exceeded actual value earned by $24 million. DMO progressively recovered these overpayments.

23. There are relatively small milestone payments remaining for the major capability deliveries ahead in the project. The milestone payments for the Acceptance of all four FFGs and the Acceptance of FFG Upgrade Software total $11 million (February 1998 prices). This is 1.1 per cent of the Prime Contract price. The milestone payment due at Contract Final Acceptance in December 2009 is $3.36 million (February 1998 prices), which is 0.34 per cent of the Prime Contract price.

24. This audit highlights some of the challenges Defence faces in acquiring advanced capabilities for the Australian Defence Force (ADF). DMO relies on industry to deliver Defence's major capital equipment acquisition programme outcomes. If industry and DMO fail to deliver the specified capability to schedule, then invariably the ADF experiences delays in achieving the anticipated capability. In the FFG Upgrade Project's case, there is a four and a half year delay in the delivery of the final upgraded ship and an over five year delay in the delivery of the upgraded Combat Team Training facility. Project delays also result in DMO, the ADF and DMO's Technical Support Agencies carrying additional costs associated with maintaining and supporting DMO's project teams for longer, and at greater skill levels, than originally anticipated.12

25. Another challenge highlighted by this audit is the need for DMO to establish contractual frameworks that encourage and require contractor performance through appropriate contractual performance management and progress payment regimes. In the case of the FFG Upgrade Project, the contract did not provide DMO with sufficient contractual leverage over the contractor, in terms of approval rights over the project's test and evaluation programme, nor did its liquidated damage provisions effectively discourage variations to contracted delivery schedules. The FFG Upgrade Project demonstrates that once major Defence capital equipment contracts are entered into, the prospects for DMO overcoming inadequate provisions are fairly limited. Since the FFG Upgrade Prime Contract was signed in June 1999, DMO has taken steps to achieve better contract provisions for test and evaluation and requirements verification.13

Key findings by chapter

Payments and schedule progress (Chapter 2)

26. The FFG Upgrade Prime contract specifies that the contract price shall be payable progressively by earned value method payments and by milestone payments. The earned value method requires the Prime Contractor to use a DMO certified EVMS, which was achieved in November 2001, that is capable of objectively measuring how much work has been accomplished on the project. By July 2007, the EVMS was reporting the project as actually costing some $39 million more than the budgeted cost of work scheduled to be completed at that time. This cost overrun does not flow on to Defence because the FFG Upgrade Prime Contract is a variable priced contract, which allows only for price variations based on agreed price variation formula and indices for labour, material and foreign currencies.

27. From the April 2004 Deed to the May 2006 Deed, the Upgrade Project experienced an average schedule extension of 22 months for each ship and this represents an in-year schedule slippage of 85 per cent. Overall, the schedule extensions have delayed the delivery of the last ship to be upgraded by four and a half years. The ANAO has calculated that as a result of schedule extensions the availability of Upgraded FFGs for Navy tasking has been reduced by an average of 20 per cent, assuming the Contract Master Schedule of mid 2006 is maintained. This Contract Master Schedule had not been verified by DMO through an Integrated Baseline Review, as at September 2007.

28. SEA 1390 Phase 4B SM-1 Missile Replacement Project has also experienced schedule slippage. As at September 2007, the slippages ranged from three to 18 months for a number of key project milestones. DMO is not predicting schedule slippage for future Phase 4B milestones.14

Upgraded capability development (Chapter 3)

29. The FFG Upgrade contract for Phase 2.1 assigns Total Contract Performance Responsibility to the Prime Contractor, thus making the Prime Contractor solely responsible for all design and construction aspects of the project, from contract signature until each upgraded FFG and all associated project elements are finally accepted by Defence. Consistent with that responsibility, the contract generally limits FFGSPO's engineering role to reviewing, commenting or, in limited instances, agreeing to the Prime Contractor' activities. It is only at Provisional Acceptance, Acceptance and Contract Final Acceptance that the FFGSPO may reject delivery of the contracted supplies.

30. Audit evidence shows FFGSPO monitored the Prime Contractor's performance and provided extensive feedback to the Prime Contractor which generally sought improvements and visibility into the project's engineering development and testing procedures and results. The feedback was aimed at allowing the SPO to gain an adequate level of confidence that the upgrade contract's function and performance requirements would be met. FFGSPO was assisted with advice from Defence resources including Defence Science and Technology Organisation, Navy personnel from HMAS Sydney, the Royal Australian Navy's Test, Evaluation and Analysis Authority, and the Royal Australian Navy's Ranges Assessing Unit.

31. Despite the efforts made, FFGSPO was only able to verify that less than half (591) of the 1221 Baseline Build 1 requirements had satisfied the contracted function and performance specifications by August 2007.15 At that time, FFGSPO referred 285 requirements back to the Prime Contractor with requests for additional information. The Prime Contractor had not offered 217 requirements to FFGSPO for acceptance, given that the contractor had elected to utilise the Prime Contract's provisions for multiple Baseline Builds of software.

32. The FFGSPO through Configuration Control Audits and Logistics Documentation Reviews identified that the information needed to operate, maintain and support the upgraded equipment is available from the Prime Contractor. However, FFGSPO records of August 2007 show the Prime Contractor had not delivered all final editions of the Ship Selected Records and Systems Manuals, which need to be aligned with Navy's equipment operator and maintainer requirements.

HMAS Sydney's Provisional Acceptance (Chapter 4)

33. HMAS Sydney's Initial Operational Release was rescheduled to occur in May 2007, however, this has not been achieved by October 2007. An FFG Upgrade Board of Review, jointly headed by DMO's Head Maritime Systems Division and Navy's Fleet Commander, was reviewing the situation at the time of this report's completion.

34. The FFGSPO is required by Navy Regulations to produce a Safety Case for the FFG Upgrade, that demonstrates due diligence has been given to the Occupational Health and Safety implications of the introduction into service of new equipment and systems. Navy Systems Command reviewed HMAS Sydney's Safety Case revisions of November 2006 and April 2007, and could not endorse them due to concerns regarding software development, safety management, Integrated Logistics Support and Hazard Management. The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that it has not been advised of the reasons for "rejection" of the FFGSPO TI-338. Therefore it is not aware of any deficiency related to a non-conformance on its part.

35. FFGSPO is also required to produce a Report of Materiel and Equipment Performance State (TI-338) for each upgraded FFG. Navy Systems Command reviewed HMAS Sydney's TI-338 revisions of February 2007 and April 2007, and raised concerns regarding the large number of function and performance requirements not conforming to the Contract.

Recommendations

36. The ANAO made three recommendations. The first recommendation aims to achieve improved performance in the Information Technology system used by FFGSPO. The second recommendation seeks improvements in the FFG Upgrade Project's software development progress measurements. This recommendation aligns with the Project's need to ultimately measure software system development progress in terms of contractual requirements completion. The final recommendation is for DMO to assist FFGSPO by providing the SPO with additional requirements verification and validation expertise. The aim would be to assist FFGSPO expedite the resolution of the FFG Upgrade Project's increasingly complex requirements verification and associated systems engineering issues.

Agency response

37. The Department of Defence provided a response to this report on behalf of the DMO and Defence. Defence agreed to the recommendations and provided the following overall comment:

Defence and DMO notes that the report provides an in depth assessment of the key events that have occurred over the life of the project, particularly since the 2005 ANAO Report Audit Report No.45 2004-2005, Management of Selected Defence System Program Offices.

The Guided Missile Frigate (FFG) Capability Upgrade is a highly technical project which involves the development and integration of complex systems (for example; combat system software scope and size exceeds two million source lines of code, notwithstanding the fact that electronic system hardware development and integration is occurring in conjunction with software development). By working collaboratively with the contractor, DMO continues to observe numerous improvements that are enabling the project to progress in an effective manner in efforts to realise delivery of the full upgraded FFG capability. These include increased production efficiencies and detailed risk assessments stemming from lessons learned from HMAS Sydney, and improvements in test and engineering review processes. These improvements also contribute to greater schedule certainty for the remainder of the upgrade program between now and delivery of the final FFG in 2009.

Underpinning the DMO's confidence in this project was HMAS Sydney successfully conducting the First-of-Class firing of the Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) against an unmanned airborne target on 20 August 2007. The outcome provides additional confidence in the Australian Distributed Architecture Combat System (ADACS) software used to support this First-of-Class firing of the ESSM from the newly installed Vertical Launch System (VLS).

Since 1999 when the Prime Contract was awarded the DMO has implemented numerous procurement reform initiatives. Since the formation of DMO in 2000, the suite of ASDEFCON contracting templates have continually evolved and now provide the DMO with much improved requirements verification safeguards, previously lacking under the previous DEFPUR suite of templates. Further procurement reforms initiated under Kinnaird have strengthened the two pass system, which requires Defence to expend a greater proportion of it project budget in pre-acquisition planning activities, including more rigorous requirements development processes.

Capability delays are also being effectively mitigated to minimise impact on fleet activities, including; extension of HMAS Adelaide, transfer of some operational tasking to other classes of ship and commissioning of ANZAC Frigates Toowoomba and Perth.

Footnotes

1 The information provided in this section was drawn from legal advice provided to the DMO in August 2007, in response to an ANAO Discussion Paper.

2 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that it relies heavily on constructive feedback from FFGSPO to ensure that what is delivered meets the customer's expectations.

3 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that both parties have experienced great difficulty reconciling the Contract's "Total Contract Performance Responsibility" provisions with the Project Authority's interest in maintaining a sufficient degree of technical involvement, control and understanding. The contractor advised that the full meaning of both phrases has eluded many working on the project. The Prime Contractor also advised that it is important to note that Navy's Technical Regulations (and other regulatory frameworks) were not in existence at the time of Contract signature in 1999. Despite the Prime Contractor raising concerns over the lack of Technical Regulatory requirements in the contract (Problem Identification Report 143, November 2004 refers), the Project Authority has chosen not to incorporate requirements for Technical Regulation into the Contract. The Prime Contractor believes this has lead to a dichotomy between compliant contract deliverables (form and content) and the requirements of the current Regulators. This in turn has resulted in re-work within the FFGSPO's own organisation to convert or generate regulatory framework compliant products.

4 In May 2006 the parties agreed to amend the contract (CCP255) to incorporate an improved test and acceptance process known as the B-TAP process (see paragraph 3.32). The B-TAP process aims to address issues of concern and provide confidence that correct processes had delivered the contracted outcome. This process allows the Project Authority to address issues where it is not satisfied with the sufficiency of test procedures to produce results that demonstrate compliance. The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that the statement ‘material lack of compliant test data' is not borne out by the results recorded thus far from the B-TAP process. The contractor advised that of the Baseline Build 1 requirements offered at Provisional Acceptance, none required additional testing to establish acceptable objective quality evidence for the purpose of establishing the requirement that was satisfactorily demonstrated at some point in the test program. The contractor further advised in October 2007 that the key issue is that the B-TAP process has not yet been completed by the Project Authority for the Baseline Build 1 capability.

5 Initial Operational Release of a Navy capability is the milestone at which Chief of Navy is satisfied that the capability can proceed to the Naval Operational Test and Evaluation period. This is based on the advice from Navy's Fleet and Systems Commanders that the operational and materiel state of the Capability and associated deliverables are sufficiently safe, fit-for-service and environmentally compliant. At this milestone any delivery deficiencies with agreed contractual remedies are appropriately mitigated for the Naval Operational Test and Evaluation period. Initial Operational Release also marks the change in management from the DMO to Navy. Despite this change in ownership, DMO's Project Manager and the Prime Contractor retain respective project management and warranty obligations.

6 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that considerable work has been undertaken throughout July - October 2007 to demonstrate a contractually compliant Electronic Support System, and that independent tests are to be conducted in Hawaii during the Lead Ship deployment to provide comprehensive data noting the complexity of the Electronic Support System test environment.

7 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that the complexity of the test programme is acknowledged and it was necessary to introduce a contractual change (B-TAP) to address the inadequacies of the original contract. As a consequence the DMO now has an appropriate vehicle to address previously perceived difficulties within the Verification and Validation process.

8 Achieving Provisional Acceptance does not relieve the Prime Contractor of any obligations in regard to rectifying contractual non-conformance prior to the Acceptance of each Upgraded FFG and the Contract Final Acceptance in December 2009.

9 The precursors include satisfactory completion of Combat System Stress Test, training courses for ship's company completed, and Category 5 testing [Sea Acceptance Trials] successfully completed. Also, HMAS Sydney's combat system Baseline Build 1 was experiencing 16 high, 102 medium and 218 low severity System Integration Problem Reports. The Contract's Provisional Acceptance criteria, detailed in Attachment AG is zero High Severity, 25 Medium and 685 Low Severity Problem Reports. See Tables 4.2 and 4.3 for Problem Report criteria and severity definitions. The number of Medium and Low Severity Problem Reports stated in paragraph 101 of Attachment AG are the maximum unless otherwise agreed with the Project Authority. This was the clause exercised in the Provisional Acceptance process. As such, the Contractor complied with the Contract as stipulated at Attachment AG and agreed by the Project Authority.

10 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that the discretion exercised by the FFGSPO in accepting Provisional Acceptance of the Lead and First Follow On FFGs was within the specifications of the contract. The Prime Contractor further advised that it would welcome the opportunity to present the objective quality evidence that supports a higher level of maturity of the systems delivered, including the Underwater Warfare System and Electronic Support System, than has been credited in the report.

11 The Prime Contractor's Contract Master Schedule is an important component of the Earned Value Management System. It establishes the FFG Upgrade Project's key dates and hence is required to be completely compatible with and traceable to the Contract's Milestone Schedule, and be meaningful in terms of the Contract's technical requirements and key activities.

12 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that the reference to the DMO requiring "greater skill levels than originally anticipated" is a reflection of the fact that the complexity of the contract was not well understood at the outset. This was exacerbated by the necessity to expend additional effort to comply with operational, technical and training regulatory frameworks introduced after contract signature.

13 Verification is defined as the process of determining whether or not the products of a given development phase fulfil the requirements established during the previous phase. Verification confirms that the products properly reflect the requirements specified for them.

14 The Prime Contractor advised the ANAO in October 2007 that the success of Phase 4B is predominantly due to the exposure and experience derived by the engaged US Vendors that were also responsible for key elements of the systems delivered in Phase 2.1.

15 Baseline Build 1 includes the upgrade of the Combat System Sensors, the Combat Data System and the Missile Fire Control System.