Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Management of the Australian Broadband Guarantee Program

The objective of the audit was to assess if DBCDE had effectively managed the ABG program, and the extent to which the program was achieving its stated objectives. The audit examined DBCDE's activities supporting the planning, implementation, monitoring and performance reporting for the ABG program from its commencement in April 2007 to June 2010.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Government is seeking to achieve maximum participation of Australian households and businesses in the digital economy.[1] The adoption of broadband in Australia has not been as widespread and has not offered the level of quality and speed available in other developed markets, while being simultaneously subject to high prices and data caps.[2] The high price of broadband compared to most other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development economies has also hampered Australia's performance as a successful digital economy.[3] Over the past four years, with the roll-out of new technology, there has been a marked improvement in commercial broadband services. However, non-metropolitan take-up of broadband was 53 per cent in June 2009 (the latest available data) and has consistently lagged metropolitan areas by up to 15 percentage points.[4]

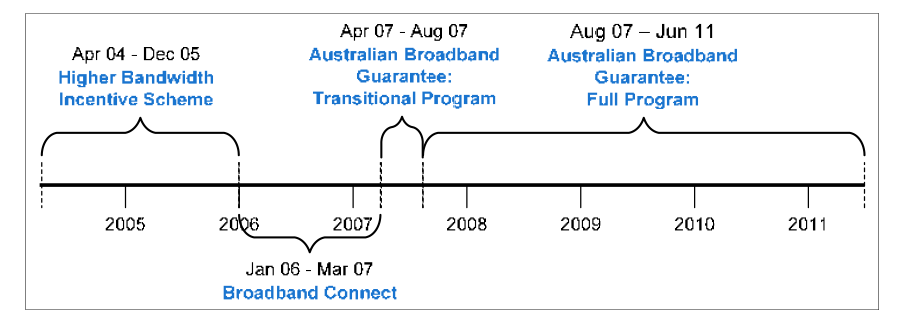

2. In 2002, the Regional Telecommunications Inquiry (RTI) identified that a major impediment to regional, rural and remote Australia having equitable access to higher bandwidth services was the higher prices that users pay.[5] In response to the RTI, the then Government established the Higher Bandwidth Incentive Scheme (HiBIS) in April 2004. This was replaced by the Broadband Connect (BC) program which was, in turn, replaced by the Australian Broadband Guarantee (ABG) program in April 2007 (see Figure S1).[6] The ABG program is administered by the Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy (DBCDE).

Figure S1 Timeline of ABG and predecessor programs

Source: ANAO analysis of DBCDE data.

3. The primary objective of the HiBIS and BC programs was to achieve prices for higher bandwidth services in regional Australia that were comparable to metropolitan services.[7] The objective for the ABG program has been revised a number of times and, from August 2008 to June 2010, was to provide all Australian residential and small business premises with access to metrocomparable broadband services. From July 2010, the objective is to provide Australian residential and small business premises with access to high quality, reasonably priced broadband services in locations where such services are not commercially available.

4. Eligible premises are restricted to those areas that are unable to access a metro-comparable broadband service as defined in the program guidelines.A metro-comparable broadband service is defined as one that provides data download/upload speeds of at least 512/128 kilobits per second and a data allowance of three gigabytes per month, at a total cost to the customer of no more than $2500 (including GST) over three years (equivalent to a maximum of $69.44 per month). The program guidelines are approved by the Minister for Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy (the Minister).

5. Under the ABG program, a one-off incentive payment (subsidy)[8] is offered to registered internet service providers to connect and supply broadband services to eligible household and small business premises in regional, rural and remote areas of Australia.[9] Providers are required to offer at least one ‘threshold' service and one ‘added value' service. They may also offer cheaper, lower capacity ‘entry level' services and additional added value services.[10] Typically, providers register several plans under each of the entry level and added value categories.

6. The department approves all service plans (including pricing structures) as part of the process of registering providers.[11] Eligible customers can choose to connect to any entry level, threshold or added value service plan registered by their provider under the program. From the beginning of the program to 30 June 2010, the ABG threshold service met the requirements of a metro-comparable broadband service.

7. Over 925 000 premises were eligible to receive ABG broadband services at the start of the program. Claims totalling some $258 million have been paid to 34 providers for connecting over 103 000 ABG customers from the start of the program on 2 April 2007 to 30 June 2010. Almost 95 per cent of the subsidies paid under the program were for satellite broadband connections. During 2009–10 there were 18 registered providers (including two inactive providers). 2010–11 ABG program

8. As previously stated, the objective of the ABG program in 2010–11 is to provide Australian residential and small business premises with access to high quality, reasonably priced broadband services in locations where such services are not commercially available. These locations continue to be in rural and remote areas where commercial infrastructure has not been deployed. The program also aims to provide a measured and seamless transition to the high speed broadband services that will be made available under the National Broadband Network (NBN), by providing access to subsidised program services while the NBN is being rolled out.[12]

9. The incentive payments offered to providers and the metro-comparable eligibility criteria defined in the program guidelines have not changed under the 2010–11 program. While the standards for entry level services have not been revised, the minimum requirements for a threshold service have effectively doubled, with speeds now one megabit per second download and 256 kilobits per second upload and the monthly data allowance six gigabytes (with at least three gigabytes at peak times). Added value services must continue to exceed the requirements of a threshold service. The department advised that the ABG program will terminate at the end of 2010–11.

Audit objectives and scope

10. The objective of the audit was to assess if DBCDE had effectively managed the ABG program, and the extent to which the program was achieving its stated objectives. The audit examined DBCDE's activities supporting the planning, implementation, monitoring and performance reporting for the ABG program from its commencement in April 2007 to June 2010.

Overall conclusion

11. The ABG program operates in an environment where broadband technologies have significantly improved and commercial broadband infrastructure has been expanding. The progressive implementation of the Australian Government's NBN has also commenced and will continue over the next several years. The ABG program is seen as complementing the roll out of these services.

12. The ABG is a mature program that has built on the experience gained through its predecessor broadband subsidy programs HiBIS and BC. These programs were designed to provide equitable access to broadband services in target areas, in terms of price and functionality. Underpinning the objective of these programs is the concept of the metro-comparable service standard, which is the eligibility benchmark for the program. Incentive payments are offered to registered internet service providers to connect and supply broadband services to eligible premises.

13. The ABG program has provided subsidised access to broadband services for more than 103 000 residences and small businesses in regional, rural and remote areas of Australia pending the roll out of major infrastructure initiatives, including the NBN. The number of underserved premises in Australia has fallen from over 925 000 at the start of the program to 160 000 in July 2010. In part, this reduction can be attributed to the ABG program, but has primarily resulted from the roll out of commercial broadband services into previously underserved areas. Some 70 per cent of the premises that received an ABG connection between 2 April 2007 and 30 June 2010 were in areas where a commercial broadband service had become available by 1 July 2010.

14. The policy settings for the ABG program are matters for the Australian Government to determine, based on advice from its department and any other sources. In this context, there has been a six-fold increase in the minimum data allowance[13] for the ABG threshold service over the life of the program, but little improvement in the minimum download speed. Since 1 July 2010, the monthly data allowance for the threshold service is now more closely aligned with the Australian average data downloaded per month. However, the entry level service, which accounts for about 77 per cent of ABG connections, has not changed over the three years of the program. The ABG base subsidy rate of $2750 set at the start of the program and which has been paid for about 95 per cent of ABG connections has also not changed. On average, prices paid by ABG customers, while lower than would have been paid without the subsidy, have exceeded the prices paid for equivalent broadband services (in terms of speed and data allowances) in metropolitan areas.

15. Following the Regional Telecommunications Independent Review in September 2008, the Government agreed to monitor the broadband services offered under the program so that they continued to provide a metrocomparable option for regional Australians. The department advised that its metro-comparable ABG threshold service is determined on the basis of a comparison with metropolitan broadband services most commonly taken up, and other relevant factors, including the program budget and commercial service developments (such as Telstra Next G). Nevertheless, for the reviews of the service levels and subsidies completed in 2008, 2009 and 2010, there was a lack of documentation to support the department's recommendations to the Minister, and the underlying rationale for changing (or retaining) program elements was not readily apparent.

16. To administer the program and its interface with customers and providers, the department has established an effective management framework. There are generally sound processes for registering providers, assessing customer and claim eligibility, and maintaining compliance with program requirements. The department also has adequate governance arrangements in place to support the program, which have improved as the program has evolved. Risk assessments are now more strategically focused and the department's record keeping practices supporting management reporting have been enhanced. However, the audit identified a number of shortcomings in the department's technical testing regime of the ongoing quality of broadband services delivered by providers, the conduct of telephone audits of ABG customers, and site audits of ABG providers. The department has taken steps to address these matters.

17. The department has not reported against the program's key performance indicators and performance targets outlined in its Portfolio Budget Statements, whether program objectives have been achieved and what outcomes can be attributed to the program's intervention. Performance reporting has largely been activitybased and does not include key program elements, their results and impacts, or trends over time. This type of information would give greater transparency to the operation of the program, better inform management and policy decision-making, and provide context about the environment in which the program is operating.

18. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving performance measurement and the transparency of reporting for the ABG program (and any future broadband programs).

Key findings

Program governance arrangements (Chapter 2)

19. The department has established sound governance arrangements to support the ABG program. Over time, generally adequate business planning, risk management, internal reporting and demand forecasting processes have been implemented and improved. However, the usefulness of some of these measures was reduced by a number of factors, such as: the delayed implementation of a demand forecasting model; the timeliness of management reports; and until recently, the currency and quality of the program's risk register.

20. At times, there have been inconsistencies or anomalies in the program metrics reported in internal management reports—an issue compounded by the practice of not keeping records of how the data reported was derived. Similarly, by not keeping copies of the outputs of the demand forecasting model, the department has impaired its ability to effectively review and adapt the model. The department has now implemented procedures to retain appropriate records.

Provider registration (Chapter 3)

21. The department has implemented structured and transparent processes for the assessment and registration of providers in the ABG program. The program guidelines contain comprehensive information about the program, including the application, assessment and registration process. The guidelines have been regularly reviewed, approved by the Minister, and made publicly available on the department's website. The ABG operations manual details the procedures for provider assessment and registration, including benchmark timeframes. The department also consults with expert advisors to assess applicants' financial and technical capacity prior to registration.

22. The ANAO examined the registration process for eight of the 18 ABG providers. All providers in this sample had a deed in place signed by the delegate that set out the terms and conditions for providing their services under the ABG program. With the exception of three instances,[14] applications for registration, or requests for variation to the deed, were duly processed, approved by the chair of the assessment panel, and executed. 23. During the audit, the ANAO raised concerns that the department's practices resulted in providers being advised that their applications had been either accepted or rejected before submitting any details to the delegate for decision. After taking legal advice on this matter, DBCDE advised that it would, in future, ensure that funding deeds are not forwarded to providers for execution until after the delegate has approved the allocation of funds for the Commonwealth to enter into a financial arrangement.

Assessing customer and claim eligibility (Chapter 4)

24. Under the ABG program guidelines, a person is only eligible for a subsidised broadband service if he/she is an eligible customer type; their premises is an eligible premises type; and their premises does not have access to a metro-comparable broadband service (as defined by the program guidelines).

25. A registered provider is entitled to receive an incentive payment for connecting and supplying an ABG service to a customer, located within their registered service area, who has been determined as eligible by the department. DBCDE assesses eligibility at two stages: when a customer registers for the ABG program (pre-claim); and when the provider claims an incentive payment (post-claim). The ANAO examined the processes the department has implemented for pre- and post-claims. Pre-claim assessment of customer eligibility

26. Potential customers seeking an ABG service, must register with DBCDE using a webbased tool known as the Broadband Service Locator (BSL), which is hosted on the department's website.[15] Based on the premises address information provided by the customer, the BSL assesses if a customer is eligible for a subsidised service. The ANAO selected a random sample of 61 customers[16], registered during the calendar year 2009, to assess if the premises location had been correctly plotted. The locations plotted for customer premises by the BSL were compared with those plotted for the same address information on a third-party mapping application.

27. In most cases (74 per cent), the BSL plotted a premises location that correlated with the premises visible in the satellite image from the third-party mapping software. In 21 per cent of cases, both mapping platforms were only able to provide approximations of premises location, reflecting the regional and remote nature of these locations. For the remaining five per cent of cases, neither mapping platform was able to provide a reasonable location match.[17] Overall, the BSL accurately and reliably plotted the location of customer premises where adequate information was supplied.

28. The ANAO also identified that some customers who should have had access to a commercial service had been incorrectly classified as being eligible for a satellite service. Over a six-month period (August 2008 to February 2009), the department had inadvertently omitted 211 ADSLenabled exchanges from the BSL.[18] Customers in these areas who registered during this period were directed by the BSL to a subsidised service, rather than to available commercial services. The department determined that 351 customers received a subsidised connection at a total cost of more than $875 000; and an additional 245 customers held unlodged declaration forms on 30 April 2010 referring them to a subsidised service, representing potential claims totalling over $540 000.

29. The department amended the BSL registration status of the 245 customers that had not lodged declaration forms. These customers were required to re-register on the BSL if they wanted to claim a service, at which time they would be provided with updated information about the services they may access. In June 2010, the department also wrote to the 351 customers that had received a subsidised connection, informing them that a wider range of commercial broadband services, including ADSL, may be available than was previously indicated when they registered on the BSL.[19] The department also decided not to pursue recovery action in respect of the payments made to providers arising from this error. Post-claim assessment of customer and claim eligibility.

30. The BSL enables customers to move their premises ‘pin' during the registration process to allow for and correct possible mapping inaccuracies. However, this facility also creates a risk of illegitimate pin movements in order to become eligible for a subsidised service. In July 2009, the department developed an automated method of extracting pin movement data from the BSL and viewing both the original geocoded location and subsequent pin movement on a third-party mapping application. Departmental staff could then examine the two locations and form an opinion as to whether the pin movement was legitimate or potentially invalid. Potentially invalid pin movements

31. In August 2009, the department initiated a series of audits of potentially invalid pin movements made since the commencement of the program. These audits identified claims worth over $1.1 million, that appeared to be invalid as a result of illegitimate pin movements. The claims had been lodged predominantly by two providers. A small number of similar claims were also lodged by five other providers. In September 2009, the matter was referred to the Australian Federal Police in accordance with the department's fraud control procedures.

32. Subsequently, $864 000 was recovered from providers for over 400 paid claims that were deemed ineligible. As well, DBCDE declined to pay more than 100 other claims lodged by two providers totalling approximately $262 000.

Monitoring and compliance (Chapter 5)

33. The ABG compliance framework aims to ensure that payments to registered providers are accurate, accountable and justified. The ANAO reviewed the compliance activities undertaken by or on behalf of the department.

Telephone audits

34. Telephone audits commenced in April 2008 and the process was subsequently refined in September 2009. Although the primary reason for introducing the audits was to address concerns that claims were lodged by providers prior to a service being connected for the customer, the telephone audits did not seek to obtain details of the actual date of connection.[20] The procedures also required that up to 15 customers for each provider be contacted each month. However, the number of telephone audits conducted fell well short of the number intended.[21] In addition, the results of the telephone audits were not consistently collated and regularly reported.

35. Where spreadsheets recording details of the telephone audits were available, many of the audits indicated that the customer was not able to be contacted (even after three or more attempts).[22] However, it was not apparent that any follow-up action had been taken to verify the existence of the customer and that they had received the subsidised broadband service. About one-fifth of the telephone audits undertaken in late 2009 and early 2010 had also not been recorded in the relevant database.[23]

36. During the audit, DBCDE revised its framework for conducting telephone audits of ABG customers. The changes were designed to improve rates of contact with customers, compliance outcomes, and the recording and reporting of outcomes, including by telephoning customers during non-business hours.

Contracted testing of broadband services

37. Ensuring that customers continue to receive quality broadband services after providers receive the incentive payment is an important part of compliance monitoring under the ABG program. The program guidelines require that ABG services must meet minimum data speed and network availability standards for a period of three years from the date of connection. The department monitors the quality of these services through an outsourced testing regime and publishes summary results on the ABG website.

38. The contractual arrangements with the testing contractor regarding the coverage and methodology of the data speed testing regime are not prescriptive. The agreed work is variously described as testing of ‘the full range of the Program's Services', or measurement of data speeds on a ‘diverse range of broadband technology platforms (wireline, wireless and satellite) for ABG eligible broadband services'. The department advised that the testing carried out meant that one of each provider's popular plans for any of their registered platforms is tested each month. However, DBCDE had not conducted any analysis to identify popular plans for the purposes of determining the appropriate services to be tested. In practice, the department did not instruct the testing consultant regarding the specific service(s) to be tested, rather the consultant contacted the provider to set up a test service of a registered service plan nominated by the provider.[24]

39. The ANAO analysed monthly data speed test reports, the results summaries posted on the ABG website and information extracted from the department's Broadband Customer Online Management System (BCOMS)[25] relating to customer uptake of registered services. The analysis sought to confirm that appropriate testing was carried out, follow-up actions were taken where necessary and the testing was accurately reported to the department and the public (though the website).

40. The analysis revealed that most providers passed the data speed testing requirements most of the time.[26] Although there were prolonged periods of consecutive failed tests (up to nine months for one provider), these were typically associated with issues with providing the test service, rather than providing services to customers. In all cases where a provider had failed one or more tests, the provider passed a subsequent test, indicating that remedial action had been taken.[27] However, the ANAO also identified a number of inconsistencies and errors, including:

- six instances where the service delivery platform reported as tested was not the platform actually tested (the duration of these errors ranged from one month to two and a half years); and

- an additional seven instances where a registered provider was not being tested for a service delivery platform that it provided.

41. The department accepted that insufficient monitoring of data speed testing was the primary cause of errors in the testing of the quality of services and reporting on its website, which it was moving to rectify promptly. The department has ceased the practice of allowing providers to nominate their most popular service for testing and, for the 2010–11 program, requires that each provider's registered threshold service on each registered platform be tested. The testing contractor has been advised of the providers, platforms and service plan speeds to be tested.

Compliance audit activities

42. DCBDE conducts a range of in-house compliance audit activities, in addition to on-site audits of providers performed by a contracted auditing firm. Programmed audits are supplemented by ad hoc reviews and special investigations, as necessary, in response to specific concerns of provider noncompliance with program requirements.

43. The 2007–08 provider audit program was approved late in the year (in May 2008) and listed five audits. The explanation for not conducting the audits earlier in the year was that there had been a ‘greater focus on addressing outstanding compliance issues, primarily related to the end of Broadband Connect.' There was no audit program for 2008–09 and no audits were conducted during that year. All except two of the 2009–10 scheduled audits and compliance activities were completed during that year. The department advised that these audits were replaced by compliance activities related to pin movements. Report finalisation timeframes had generally shortened compared with those for the 2008 audits (up to eight months).

Internal reporting on compliance

44. As part of the ABG compliance framework, DBCDE maintains provider compliance profiles, which are intended to provide a ‘snapshot' of each provider for quick reference by ABG compliance staff. Although provider information is kept in various formats in a number of places[28], provider profiles have not been updated in a timely manner, which reduces their usefulness as a compliance monitoring mechanism. The department accepted that revising its profiles to provide an up-to-date summary of providers' operational and compliance history under the ABG program would be a useful compliance tool.

Review, measurement and reporting of the ABG program (Chapter 6)

Reviews of service levels and subsidy rates

45. ABG service levels and subsidies are reviewed by the department as part of the process of revising the program guidelines. The department advised that the metro-comparable ABG threshold service is determined on the basis of a comparison with metropolitan broadband services most commonly taken up. Other relevant factors, including the program budget and commercial service developments (such as Telstra Next G) are also taken into consideration.

46. For the reviews undertaken in May 2008, February 2009, August 2009 and February 2010, the department provided various discussion papers and spreadsheets that it used to assist in the preparation of the program guidelines in relation to commercial metro-comparable service levels. However, these documents did not include conclusions or recommendations drawn from any analysis of the market and ABG data, or comparisons with services commonly taken up. It was not clear if any other factors were considered and how these internal working documents informed the advice provided to the Minister in relation to proposals to change or retain existing program arrangements. The department was also unable to provide documentation to support its review of subsidy rates. The review process does not reflect an evidence-based approach to the provision of policy advice. There is also room for improvement in the analysis that underpins the ministerial advice for this program.

Measuring and reporting the performance of the program

47. Measuring and accurately reporting program performance is important for good management and public accountability. A department's Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and annual reports should provide the Parliament with sufficient information about the actual performance of programs.

Key performance indicators and targets for the program

48. A different set of key performance indicators (KPIs) has been used for each year of the program. In mid-2008, the department developed a new set of metrics based on the KPIs in the 2008–09 PBS. These were intended to apply for the life of the program (that is, to 30 June 2012) but were replaced with a single KPI in the 2009–10 PBS. This KPI was replaced by two new KPIs in the 2010–11 PBS.

49. KPIs may evolve over the life of a program. They may be broadened or refined to better reflect the extent to which a program is achieving its objectives. However, to be useful, KPIs need to maintain at least a core consistency and continuity. When KPIs are continually changed, the program's performance over time is not easily assessed. The department acknowledged that frequent changes to the program's KPIs was not desirable.

50. Ideally, the performance information set out in the department's PBS would also have included targets for the program, which may be quantitative (numerical) or qualitative (descriptive), but must be verifiable. The KPIs in the PBS did not include any numerics for the quantitative targets identified for the ABG program until 2009–10, when the target number of ABG connections for that year was reported.

Reporting program performance

51. The department has not clearly reported against its performance targets on the broadband services offered, and taken up, under the program and how they compare with services offered in metropolitan areas. The minimum data allowance for ABG threshold services has been increased twice, bringing it into closer alignment with the Australian average data downloaded per month, but there has been little improvement in the minimum download speed. Added value services have also increased to remain above threshold services. The minimum standards for entry level services, which are taken up by three out of every four ABG customers, have not changed over the life of the program.

52. The department's 2008–09 annual report stated that, based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Internet Activity Survey for the December 2008 quarter, the speed and download standards for ABG services were broadly comparable to the most widely taken up broadband services across Australia. The ANAO's analysis of ABG, ABS and industry data for the three years of the program suggests that, in general, ABG services have not kept pace with the services available in metropolitan areas. On average, prices paid by ABG customers, while lower than would have been paid without the subsidy, have exceeded the prices paid for equivalent broadband services (in terms of speed and data allowances) in metropolitan areas. The ANAO recognises that the policy settings for the ABG program are matters for the Australian Government to determine, based on advice from its department and any other sources.

53. The program performance information reported for the period 2007–08 to 2009–10 provided limited or no information on, amongst other things, the: number of underserved premises; type of services taken up; and quality and cost of services. There is little information on trends over time. This type of information would give transparency to the operation of the program, better inform management and policy decision-making, and provide context about the environment in which the program is operating.

54. In addition, some aspects of the performance information reported could not be reconciled with information held by the department and ABS data. The 2008–09 performance report also does not sufficiently acknowledge the limitations of the survey data used to assess some aspects of the program's performance.

Summary of agency response

55. The Australian Broadband Guarantee (ABG) is a demand driven yet budget capped program, with the objective of providing a service to Australians who cannot access via normal commercial sources reasonablypriced broadband at a standard comparable to metropolitan Australians.

56. Each element of the statement above is important in the framing of the ABG service. Because broadband is a growing service generally supplied in Australia by commercial providers, the ABG program also needs to be conscious of the need not to provide a disincentive to continued expansion of provision of reasonably-priced broadband to Australians in rural and remote areas. Thus it is a complementary program, carefully targeting Government financial support to premises where adequate commercial broadband services are not available. As commercial services expand into more remote areas, the target areas for ABG support are and have been reduced. More recently, the ABG has also been conscious that the rollout of the National Broadband Network, including both satellite and wireless services in rural and remote Australia, has been Government policy. As such, ABG has always had a judgement element inherent in its standards, reflected in the judgement of the Government about when a metro-comparable service, which sets the benchmark for determining eligible premises under the ABG program, is available.

57. The Department considers that the first five chapters of the report represent a fair and constructive assessment of performance but believes that elements of Chapter 6 suffer to a degree from a misapprehension about the program, in relation to ANAO expectations of continuous improvement in the provision by the ABG of metro-comparable services.

ANAO comment

58. In its response to the report, the department has raised concerns about Chapter 6, particularly in relation to references to the policy parameters of the program and the data used by the ANAO to analyse the program's performance. Chapter 6 examines the periodic review of ABG services and subsidy payments as well as how the department measured and reported the performance of the program against the KPIs and performance targets set out in its PBS and annual report. Where performance information was not reported against these KPIs and performance targets, the ANAO analysed available ABG and ABS data to comment on the program's performance.

59. This report appropriately recognises, in paragraph 14, that the policy settings for the program are matters for the Australian Government to determine; accordingly, it makes no comment on the merits of the Government's policy position. Table 1.1 in the report sets out the minimum standards and the price cap for the metro-comparable ABG threshold service; and relationship to the pricing of entry level services and added value services. The report (paragraph 6.51) also presents as a statement of fact that, over the life of the program, the minimum standards for the ABG threshold service and added value services have been increased twice and the minimum standards for entry level services have not changed.

60. Further, in its detailed response (Appendix 1), the department makes a distinction between the average speed and data allowances of the broadband services published by the ABS in its Internet Activity Survey and the speed and data allowances of the broadband services most commonly taken up. However, the department was unable to provide its analysis identifying the broadband services ‘most commonly taken up' even though it advised that this data was used when setting and reviewing subsidy rates and service levels (paragraph 6.4). In the absence of this departmental data, the ANAO analysed the ABS Internet Activity Survey data for those KPIs and performance targets which the department had not reported against (Figures 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3). The ABS Internet Activity Survey is based on subscribers who have accessed the internet or paid for access to the internet.

Footnotes

[1] Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy, 2009, Australia's Digital Economy: Future Directions Final Report, pp.i-1. The benefits of increasing the engagement of both businesses and consumers in the digital economy include: realising productivity gains; achieving more efficient and sustainable use of natural, physical and human resources; more effective health and education outcomes; and enhanced social inclusion.

[2] Parliamentary Library Briefing Book: Key Issues for the 43rd Parliament, Population and Infrastructure, September 2010, p.44.

[3] Australia's Digital Economy, op cit, p.9.

[4] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Internet Activity Survey, Australia, Publication No.8153.0.

[5] Regional Telecommunications Inquiry 2002, Connecting Regional Australia: The Report of the Regional Telecommunications Inquiry, p.xxiii., Finding 6.4.

[6] A performance audit of the management of the HiBIS and BC Stage 1 programs was completed in May 2007. See ANAO Audit Report No.36, 2006–07 Management of the Higher Bandwidth Incentive Scheme and Broadband Connect Stage 1.

[7] There were also two supporting objectives: to promote competition among higher bandwidth service providers; and to ensure efficient use of public funds by effectively targeting support to areas of need in regional Australia.

[8] The program has five payment levels associated with the different technology platforms and installation circumstances. Almost all payments made under the program were for $2750 (including Goods and Services Tax), with most being for satellite services. Payments of up to $6600 can be made for difficult and costly installations, such as in cyclone prone areas.

[9] Providers are required to offer to provide the ABG service to the customer for three years.

[10] From April 2007 to June 2010: threshold services provided peak data download/upload speeds of at least 512/128 kilobits per second and a data allowance of three gigabytes per month; entry level services provided a peak speed of at least 256/64 kilobits per second and 500 megabytes per month data allowance; and added value services had to exceed the minimum functionality requirements for threshold services.

[11] Providers may apply at any time to vary their plans and these must be approved by the department.

[12] The NBN is intended to provide speeds of 100 megabits per second to 93 per cent of Australian premises. Next generation wireless and satellite technologies are expected to be used to cover the remaining seven per cent. However, these next generation services are not expected to become available until at least 2014.

[13] Including the recent doubling of the data allowance from 1 July 2010.

[14] In these instances, there was either: no submission for approval of a variation; the submission for approval of a funding deed was not approved by the chair of the assessment panel as further information was required; and although the submission for approval of an extension to a funding deed was signed, it was not notated as being agreed to by the chair of the assessment panel.

[15] Potential customers unable to access the internet can call the department's ABG helpline or have a registered service provider fill in the BSL registration on their behalf. Following registration, a customer declaration form is sent to the customer that must be given to the provider if a customer proceeds to connect to a subsidised broadband service.

[16] The sample was designed to provide a confidence level of 95 per cent (± 2.5 per cent).

[17] Of these cases, only one customer proceeded to connect an ABG service, after moving the locator ‘pin' on the map shown on the BSL to the customer's correct location.

[18] The issue was rectified when the ADSL mapping layer was replaced with an updated, complete set of data.

[19] Customers were advised that they did not need to do anything if they were satisfied with their current broadband service, but were also advised about their options and the steps to take if they wished to explore the availability of commercial services or change to a new broadband provider.

[20] The date that the customer requested the service was also not verified. This information would have enabled DBCDE to verify that the customer was connected within the required 30 days, or that an extension had been approved by DCBDE prior to claim lodgement date if the connection took more than 30 days. It would also enable the department to verify that the provider's claim for payment was lodged within the required 45 days of connecting the customer to the broadband service.

[21] Although the procedures specified that 130 customers per month would be surveyed (a total of about 3000 for the period up to March 2010) the available records indicated that only a few hundred surveys were undertaken (representing less than 0.25 per cent of claims paid under the program).

[22] For example, 80 per cent of one provider's customers could not be contacted in October 2009 after several attempts.

[23] The department's procedures require that all contact with customers be recorded in the Known Individuals Management System (KIMS) database.

[24] The test service required a dedicated computer be set up in the provider's premises that was remotely accessed by the testing contractor.

[25] BCOMS records all details of service providers and claimed customers, along with information about declined and queried claims.

[26] Up to April 2010, approximately 89 per cent of tests were awarded a PASS. One–half of the FAIL results were for unsatisfactory performance. In the remaining cases, the test service was offline and could not be tested.

[27] The only action taken by the department for failed data speed tests was to remind providers of their obligations under their funding deeds.

[28] Including various databases, emails, spreadsheets, hardcopy files and the department's Information Management System.