Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Machinery of Government Changes

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the management of Machinery of Government (MoG) changes by the selected Australian Government entities.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Machinery of Government (MoG) changes are a major driver of organisational change within the Australian Public Service (APS). They occur relatively frequently, often with little or no notice, and are used by the Australian Government to express policy priorities and meet policy challenges. Effective management of MoG changes to minimise transitional risks and associated costs presents an important challenge to public service leaders.

2. Over the past 20 years, the APS has undergone more than 200 MoG changes—an average of more than 10 per year. MoG changes vary greatly in scope and complexity and can involve: the abolition or creation of new government entities; the merger or absorption of entities; and small or large transfers of policy, program or service delivery responsibilities to other entities.

3. It is the responsibility of affected entities to implement MoG changes. The Department of Finance (Finance) and the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) assist entities by providing guidance on MoG change processes and requirements and facilitating the resolution of disputes that may prevent the timely transfer of funding and resources. Finance also effects the adjustment of entity funding as necessary, while the APSC effects the transfer of APS staff.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the management of MoG changes. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- central agencies provided effective guidance and support for Australian Government entities’ implementation of MoG changes, drawing on relevant experience to inform guidance material;

- affected entities established appropriate change management processes to support the implementation of MoG changes, complied with relevant legal and policy requirements, and had regard to relevant guidance; and

- expected outcomes were achieved, including timely and effective integration of new responsibilities and functions.

5. The scope of the audit was limited to an examination of the implementation of the post-2013 election and 2014 MoG changes by the 14 affected departments. The audit methodology included an on-line survey issued to the 14 departments, analysis of the additional costs of MoG changes advised by entities and a detailed examination of implementation of MoG changes in two case studies (relating to the Aged Care and Arts functions).

Conclusion

6. The Australian Public Service (APS) managed large scale Machinery of Government (MoG) changes in 2013, followed by additional changes in 2014. The ANAO’s survey and case studies indicate that the actions taken by the affected departments and central agencies helped to maintain delivery of services and payments to the public, and to manage transitional risks and associated costs. There is, however, scope to improve the timely transfer of financial appropriations and staff resources for large scale MoG changes such as those announced in 2013.

7. A September 2015 decision by the Secretaries Board, informed by central agencies’ assessments of lessons learned from the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes, endorsed the more active involvement by the Department of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission in coordinating and monitoring MoG changes. A formal review of the implementation of major MoG changes would consolidate recent practice and assist in identifying systemic improvements, and is the basis of the recommendation in this report.

Supporting findings

Impact of Machinery of Government changes

8. The 2013 MoG changes were complex, with 11 of the 14 affected departments managing multiple transfers simultaneously. The reported impact on service delivery of the 2013 MoG changes was minimal. Affected departments surveyed by the ANAO advised that they had worked cooperatively to maintain relevant government services. There were no reported impacts on service delivery for the smaller scale MoG changes of 2014.

9. The Government achieved $397 million in savings through the merger of the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. An additional $534 million in savings is to be achieved over five years through the integration of Indigenous functions within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

10. Responsibility for managing the costs of implementing MoG changes rests with the affected entities. Nine departments provided the ANAO with estimates of the additional costs of implementing the 2013 MoG changes. These costs varied markedly depending on the type and scale of the MoG change. The principal costs reported by departments related to staff redundancies, accommodation fit-outs and Information and Communications Technology (ICT) integration.

11. The financial reporting obligations of government and entities were met in 2013–14 and 2014–15. A small number of entities experienced delays in finalising their financial statements for 2013–14 and MoG changes were one of the factors behind these delays.

Central agency guidance and support

12. Finance and the APSC play a key role in providing advice and support to entities on the implementation of MoG changes. The Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Good Practice Guide (the Guide), developed by Finance and the APSC, is a valuable resource which was used by affected departments during their implementation of the 2013 MoG changes. The Secretaries Board has recently agreed to remodel the Guide, with a focus on key principles supported by links to information and other guidance material.1

13. The Secretaries Board considered lessons learned from the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes at its September 2015 meeting. Its consideration was informed by a lessons learned paper prepared by Finance, PM&C and the APSC. The paper drew on the outcomes of internal review activity, including Finance’s assessment of mechanisms to adjust appropriations and resolve disputes between departments.

14. The role of central agencies in coordinating and monitoring the implementation of MoG changes has strengthened over time. To facilitate implementation of the 2014 MoG changes within two months, Finance established milestones for the adjustment of appropriations. In September 2015, the Secretaries Board agreed to the more active involvement by Finance and the APSC in setting timeframes and monitoring implementation of future MoG changes. There would also be merit in continuing the recent practice of conducting a post implementation review to identify further opportunities for system-level improvements, particularly following a large scale MoG change such as that announced in 2013.

15. The Guide provided for an arms-length dispute resolution mechanism with escalation points for the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes. A number of disputes were resolved using this mechanism. In September 2015, the Secretaries Board agreed to changes to the dispute resolution protocol to improve the dispute resolution process.

Implementing Machinery of Government changes

16. The ANAO’s survey and case studies indicated that the affected departments developed fit-for-purpose governance and planning arrangements that were tailored to the size and complexity of the MoG changes affecting them. Most entities surveyed by the ANAO reported that they established steering committees, undertook due diligence, developed appropriate strategies and plans, and considered legal requirements in line with the guidance material provided by Finance and the APSC.

17. The Guide notes that agency heads are expected to undertake MoG changes ‘as soon as possible’. The transfer of staff and appropriation adjustments relating to the 2013 MoG changes took several months to complete. This was due to a number of factors, including:

- a new process for adjusting appropriations which was subsequently discontinued by Finance;

- significant delays in undertaking due diligence; and

- difficult negotiations on the transfer of resources, including corporate staff, partly caused by a lack of open and honest engagement.

18. In a June 2014 paper on lessons learned from the 2013 MoG changes, Finance indicated that good faith negotiations had stalled at times due to some agencies not being prepared to share accurate and coherent information. The Guide explicitly directs entities to openly and honestly identify the resources to be transferred in a MoG change. Departments of State are part of a single legal entity—the Commonwealth—and the Australian Government’s resource management framework places a positive duty on entities to cooperate with others to achieve common objectives.

19. The ANAO’s survey and case studies indicated that affected entities worked collaboratively to maintain business continuity, by sharing ICT resources while ICT systems were adapted and integrated over the longer term. The transfer of records was one of the last projects to be completed as part of the 2013 MoG changes. In one case it took 16 months to transfer records. The ANAO identified a range of issues which impeded the efficient transfer of records during the 2013 MoG changes, including differing systems architecture and system classification levels between transferring and gaining entities, and the accuracy of information about record holdings.

20. The ANAO’s survey and case studies indicated that affected departments worked together to use existing office leases where possible, rather than entering into new lease arrangements. For example, affected departments shared information about available property space through a website, GovDex, established by Finance for secure, online collaboration and cross-entity working groups.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 3.18 |

That the Department of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission conduct a post-implementation review following major Machinery of Government changes. This report should be presented to the Secretaries Board and disseminated more widely. Department of Finance response: Agreed. Australian Public Service Commission response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

21. The Department of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission provided formal comment on the proposed audit report. The summary responses are provided below, with the full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Finance

The Department of Finance (Finance) notes and welcomes the ANAO report findings.

Since the 2013 Machinery of Government (MoG) changes, Finance has reformed and strengthened MoG-related processes. This includes improvements to the transfer of appropriations, establishment of timeframes, and coordination. The Good Practice Guide prepared by Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission has been updated to reflect these lessons.

Australian Public Service Commission

The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) welcomes the report’s conclusion that the Australian Public Service managed major Machinery of Government changes effectively in 2013 and 2014. Services to the public were maintained while associated risks and costs were minimised.

The APSC supports continuous improvements to the implementation of Machinery of Government changes. Recommendation No. 1 is agreed.

22. The ANAO also provided the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), the Department of Social Services (DSS) and the Department of Health (Health) with the report. AGD, DSS and Health advised that they had no formal comment to make on the report.

1. Introduction

1.1 Machinery of Government (MoG) changes are a regular feature of the public sector landscape. These changes provide the opportunity for the Government to express priorities and meet policy challenges with new administrative arrangements. The election of a new government often triggers significant MoG changes, with a new ministry and revised ministerial responsibilities resulting in changes to the Administrative Arrangements Order (AAO).2

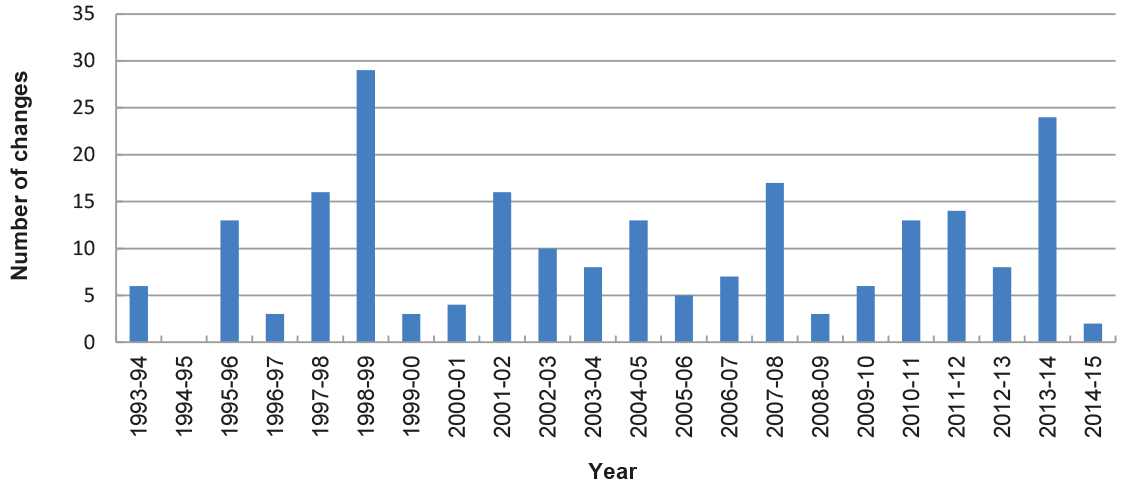

1.2 There have been 55 changes to the AAO since 1993–94, which have resulted in more than 200 changes to entity structures in the Australian Public Service (APS)—an average of more than 10 per year. For the purposes of this audit, a MoG change is defined as a change to a department’s functions, arising from a change to the AAO. Figure 1.1 shows the number and frequency of recent MoG changes.

Figure 1.1: Machinery of Government changes since 1993–94

Source: ANAO analysis of APS Employment Database (APSED) data.

1.3 MoG changes vary greatly in scope and complexity and can involve: the abolition or creation of new government entities; the merger or absorption of entities; and small or large transfers of policy, program or service delivery responsibilities to other entities. Implementation of MoG changes may require major restructuring of functions with little or no notice. Capturing the potential benefits of such re-prioritisation, while minimising transitional challenges and associated costs, presents a challenge to public sector leaders.

1.4 At a practical level, MoG changes entail substantial work in identifying and transitioning functions and staff between affected entities including integrating systems and transferring budgetary appropriations, assets and physical records. Throughout the change process entities must also continue to effectively support the Australian Government and seamlessly deliver programs and services.

2013 and 2014 Machinery of Government changes

1.5 The MoG changes following the September 2013 federal election (hereafter the 2013 MoG changes) were wide-ranging, affecting most portfolio departments and over 12 000 APS staff. The scale and scope of the changes contributed to the complexity of the process.3 Appendix 3 provides a complete list of the changes. The principal changes included:

- responsibility for Indigenous policy, programs and service delivery transferring from multiple entities to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C);

- the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) being absorbed into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT);

- three departments being abolished4 and their functions transferred to other departments; and

- two new departments being created to replace the abolished Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR).5

1.6 Figure 1.2 compares the magnitude and complexity of the 2013 MoG changes among the affected departments. It shows that the Department of Social Services (DSS), the (then) Department of Industry (Industry) and PM&C experienced the most complex MoG changes.

Figure 1.2: Complexity of the 2013 MoG changes

Note: The same data point appears for both Finance and Treasury as their MoG changes were very close in size.

Source: ANAO analysis of APSED data.

1.7 Further changes to the AAO were made in December 2014 that affected nearly 900 staff. The changes were smaller than those triggered in September 2013. Key changes included: transferring responsibility for vocational education and training (VET) from Industry to the now Department of Education and Training (DET); transferring responsibility for small business programs from Industry to the Department of the Treasury; and transferring responsibility for childcare from DET to DSS.

Roles and responsibilities

1.8 MoG changes are initiated by the Prime Minister. PM&C is responsible for providing advice to the Prime Minister on a proposed MoG change and, if required, preparing documentation necessary to give effect to the change, including the revised AAO. PM&C also advises the Department of Finance (Finance) and the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) of the changed administrative arrangements.

1.9 It is the responsibility of affected entities to implement MoG changes. PM&C, Finance, the APSC and the National Archives of Australia (Archives)6 provide support and advice to facilitate the changes:

- PM&C informs affected entities of the Prime Minister’s decision;

- APSC transfers staff under section 72 of the Public Service Act 1999 and advises on the policy framework for determining remuneration, terms and conditions of employment and workplace arrangements;

- Finance advises on appropriations, superannuation, accounting, reporting, banking, legal and governance issues, Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and accommodation. Finance also operationalises the transfer of funding arrangements once agreement has been reached between entities; and

- Archives advises on policy, standards and mechanisms for the transfer of information, records and data between entities.

1.10 Finance and the APSC have jointly developed a guide, Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Good Practice Guide (the Guide),7 to assist entities implementing MoG changes. The Guide sets out, among other things, key principles and strategies for managing MoG changes. This document is the primary source of guidance for affected entities, although it is supplemented by other guidance material developed by Finance.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.11 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the management of MoG changes. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- central agencies provided effective guidance and support for Australian Government entities’ implementation of MoG changes, drawing on relevant experience to inform guidance material;

- affected entities established appropriate change management processes to support the implementation of MoG changes, complied with relevant legal and policy requirements, and had regard to relevant guidance; and

- expected outcomes were achieved, including timely and effective integration of new responsibilities and functions.

Scope of the audit

1.12 The ANAO examined the implementation of the 2013 and December 2014 MoG changes (as specified by revisions to the AAO) by the 14 affected Commonwealth departments of state. MoG changes in 2013 and 2014 that affected other Commonwealth entities were excluded from the scope of the audit.

Audit methodology

1.13 The audit methodology included:

- a survey of various aspects of the implementation of the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes;

- review of the costs incurred from MoG changes from the nine departments that tracked and reported on these costs;

- detailed examination of two case studies: the transfer of Aged Care functions from the Department of Health (Health) to DSS; and the transfer of Arts functions from the then Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport to the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD);8 9

- review of available guidance material, including the Guide;

- interviews with relevant staff from central agencies (Finance, APSC, PM&C, Archives), staff involved in implementing the Arts and Aged Care MoG changes, and key external stakeholders; and

- analysis of data provided by the APSC from the APS Employment Database.

1.14 Appendix 4 lists the entities included in the audit.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $530 000.

2. Impact of Machinery of Government changes

Areas examined

This chapter examines the reported impact of the 2013 and 2014 Machinery of Government (MoG) changes on the delivery of government payments/services and key departmental reporting obligations. It also examines the reported costs and efficiency gains associated with MoG changes.

Conclusion

The 2013 MoG changes were wide-ranging, with 11 of the 14 affected departments managing multiple transfers simultaneously. In terms of service delivery, departments advised that the impact of the 2013 MoG changes was minimal as affected departments worked cooperatively to maintain essential government services and payments. The financial reporting obligations of government and entities were met in 2013–14 and 2014–15. A small number of entities experienced delays in finalising their financial statements for 2013–14 and MoG changes were one of the factors behind these delays.

Budget savings have been achieved through the 2013 MoG changes from the consolidation of functions. The ANAO was also advised of a range of short-term implementation costs. Responsibility for managing the costs of implementing MoG changes rests with the affected entities. Implementation costs varied depending on the type and scale of the MoG change. The principal costs reported by departments related to staff redundancies, accommodation fit-outs and Information and Communications Technology (ICT) integration.

2.1 The MoG changes following the September 2013 federal election affected 14 out of 18 departments10, with most of the affected departments having to manage multiple transfers. In announcing the changes, the Prime Minister noted that, in recent years, the structure of Australian Government departments and agencies had created confused responsibilities, duplication and waste. He further stated that the changes were designed to ‘simplify the management of government business, create clear lines of accountability and ensure that departments deliver on the Government’s key priorities’.11

Were there any reported impacts on service delivery?

The 2013 MoG changes were complex, with 11 of the 14 affected departments managing multiple transfers simultaneously. The reported impact on service delivery of the 2013 MoG changes was minimal. Affected departments surveyed by the ANAO advised that they had worked cooperatively to maintain relevant government services. There were no reported impacts on service delivery for the smaller scale MoG changes of 2014.

2.2 Australian Public Service (APS) agencies affected by MoG changes are expected to maintain services while implementing required changes. Affected departments surveyed by the ANAO advised that their responsibilities for the delivery of government services and payments had not been adversely affected by the 2013 MoG changes. Affected departments further advised that agreement between entities on the continued use of systems and staff by the ‘gaining’ department helped to minimise impact on delivery of services and payments. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) noted in its response to the ANAO’s survey that:

Transferring agencies acted with goodwill throughout the MoG transition, by continuing to host staff in their premises or on their ICT systems. Without these arrangements there would have been an unacceptable loss of business continuity and productivity.

2.3 PM&C also advised that there was minimal business disruption during the co-location of over 2000 staff across Australia into its premises. PM&C further advised that acting early to arrange relevant financial delegations and drawing rights12 allowed payments to service providers to continue, accurately and on time.13 The Department of Social Services (DSS) advised that there was minimal impact on the delivery of a major program of aged care reforms while transferring the Aged Care function from the Department of Health (Health). COTA Australia14 supported this view, advising the ANAO that the only discernible impact had been a delay in the development of quality indicators to measure the impact of aged care reforms.

Were there any financial impacts arising from the Machinery of Government changes?

The Government achieved $397 million in savings through the merger of the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), and an additional $534 million in savings is to be achieved over five years through the integration of Indigenous functions within PM&C.

Responsibility for managing the costs of implementing MoG changes rests with the affected entities. Nine departments provided the ANAO with estimates of the additional costs of implementing the 2013 MoG changes. These costs varied markedly depending on the type and scale of the MoG change. The principal costs reported by departments related to staff redundancies, accommodation fit-outs and ICT integration.

Savings

2.4 In addition to aligning entity functions with government policy directions and priorities, MoG changes can provide an opportunity to consolidate functions, reduce duplication and generate savings. The 2013 MoG changes allowed the Government to achieve $397 million in savings through the merger of AusAID with DFAT, with an additional $534 million in savings to be achieved over the five years following the integration of Indigenous functions within PM&C.

Costs

2.5 When a MoG change is announced, the challenge for the affected leaders is to capture the potential benefits of the change, while minimising transitional risks and associated costs. The implementation costs can be significant, may vary markedly and generally have to be funded from the entity’s operating budget.15 While there are no established rules for which entity pays the implementation costs when there is a transfer of function, the Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Good Practice Guide (the Guide), outlines that as a general principle entities should bear their own re-location costs.16 For example:

- entities transferring functions should bear the costs for relocating employees, furniture, equipment and files; and

- gaining entities should bear the costs of establishing the transferred employees in their new premises, including re-loading information, setting up access to the network, security arrangements and updating internal records.

2.6 The ANAO was provided with estimates of the costs associated with implementing the 2013 MoG changes by nine departments that tracked their additional costs. The additional costs reported by these departments averaged $14.5 million per department.17 Figure 2.1 illustrates the key drivers for the additional MoG implementation costs reported by entities:

- direct staffing costs made up 37 per cent of the implementation costs, with 34 per cent of these comprising redundancy costs;

- ICT changes such as hardware purchases, integration of ICT systems, inter-operability issues, and website development comprised 35 per cent of all additional costs; and

- additional accommodation costs (21 per cent) largely stemmed from property/lease acquisitions and refurbishment/fit-out of offices to accommodate essential staffing changes and needs.

Figure 2.1: Cost drivers in Machinery of Government changes

Note: Some 34 per cent of reported direct staffing costs were redundancy costs.

Source: ANAO analysis based on estimates provided by the nine departments that tracked the additional costs associated with implementing 2013 MoG changes.

2.7 The ANAO’s review also indicates that the cost of implementing MoG changes can vary and is affected by the scale and complexity of the change. Of the nine departments that reported additional MoG change costs, the average cost of $200 000 for the simplest transfers is significantly less than the average cost of $19.4 million for larger, more complex program transfers.18 A further consideration is whether the affected entity is gaining or losing functions. Typically, losing entities tend to bear a smaller proportion of the implementation costs.

2.8 Table 2.1 indicates significant variation in the types of implementation costs reported by departments. For instance, when departments merge or functions are consolidated, staff redundancies are a major component of the costs in the short term, notwithstanding the major savings that can be achieved in the longer term through reduced staffing. In comparison, when entities split or significant functions are transferred, resource gaps may emerge. In these circumstances ICT costs and accommodation refurbishment/fit-out costs emerge as the more significant costs.

Table 2.1: Estimated internal costs of implementing the 2013 MoG changes

|

Category |

Number of affected entities |

Minimum cost |

Maximum cost |

|

Direct staff costs |

|||

|

Redundanciesa |

2 |

$17 000 000 |

$28 100 000 |

|

Alignment of Enterprise Agreements |

3 |

$500 000 |

$1 000 000 |

|

Other |

1 |

$1 500 000 |

$1 500 000 |

|

Accommodation costs |

|||

|

Property/lease acquisition |

2 |

$500 000 |

$1 200 000 |

|

Refurbishment/fit-out |

4 |

$300 000 |

$14 000 000 |

|

Additional contract fees |

1 |

$900 000 |

$900 000 |

|

Removals |

4 |

$47 000 |

$1 100 000 |

|

Other (e.g. security upgrades) |

2 |

$27 000 |

$200 000 |

|

ICT costs |

|||

|

ICT purchases/hardware |

3 |

$200 000 |

$14 600 000 |

|

Service contracts—additional fees |

3 |

$14 000 |

$3 300 000 |

|

Integration of ICT systems and platforms |

4 |

$200 000 |

$17 100 000 |

|

Website development |

1 |

$700 000 |

$700 000 |

|

Other costs |

|||

|

Branding/advertising |

3 |

$11 000 |

$23 000 |

|

Records retrieval/transfer |

2 |

$8 000 |

$4 000 000 |

|

Consultancy services |

1 |

$1 600 000 |

$1 600 000 |

Note a: Reported redundancy costs may include some planned redundancies and therefore may not solely be due to MoG changes; redundancies may also result in longer-term savings.

Source: ANAO analysis based on estimates provided by nine entities that tracked costs associated with implementing 2013 MoG changes.

2.9 The ANAO identified a number of decisions by the leadership of affected entities that minimised transitional risks and costs, including:

- DSS, with the agreement of Health, continued to accommodate Aged Care staff in Health’s premises in Woden through a sub-leasing arrangement;

- PM&C’s property footprint increased from one Canberra based property to over 230 properties across the country as a result of the 2013 MoG changes. PM&C sought to avoid new Commonwealth leases by retaining staff in existing buildings, or co-locating them with other departments where possible; and

- the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) consolidated ICT service provider arrangements for the Arts function (which had become fragmented due to a succession of MoG changes), to allow for a more seamless transfer of functions in the event of a future MoG change.

2.10 Broader ICT developments across the APS are providing opportunities to standardise and streamline some processes, and may help reduce the level of ICT adjustment required by entities affected by MoG changes. For example, a web-based Parliamentary Workflow System now used by more than 50 APS entities, provides a single system for a range of interactions with ministers and Parliament, including ministerial correspondence and briefings. The Secretaries Committee on Transformation19 is also examining opportunities for increasing the common use of operating systems within the public sector.

2.11 The progressive consolidation of the delivery of APS corporate services and sharing of transactional functions (such as accounts processing, procurement, payroll and human resource management) through shared services arrangements may help to reduce the costs and transitional risks associated with future MoG changes. The Department of Employment advised the ANAO that establishing the Shared Services Centre as a result of the 2013 MoG changes reduced duplication and associated costs:

The Department [Employment] partnered with the Department of Education to establish the Shared Services Centre (SSC) to deliver corporate and enabling services to both departments following the abolition of DEEWR. This avoided the costs that would have been incurred in establishing separate corporate functions within each Department.

Were there any impacts on financial reporting?

The financial reporting obligations of government and entities were met in 2013–14 and 2014–15. A small number of entities experienced delays in finalising their financial statements for 2013–14 and MoG changes were one of the factors behind these delays.

2.12 A fundamental aspect of external accountability is the legal requirement for public sector entities to publish audited financial statements in annual reports.20 In this context, the financial appropriations associated with functions transferred through a MoG change are to be reflected in an entity’s annual financial statements:

The Accountable Authority of a receiving entity must ensure that the financial records of the functions transferred are sufficient to present fairly the entity’s financial position, financial performance and cash flows and can contribute to the timely and accurate completion of the entity’s financial statements.21

2.13 The Australian Government’s Final Budget Outcome is to be released publicly and tabled no later than three months after the end of the financial year. To enable the preparation of the Final Budget Outcome and Consolidated Financial Statements for the Australian Government, each entity’s audit cleared financial information is to be provided to the Department of Finance (Finance) by 15 August each year. The entity’s financial statements and the auditor’s report are then included in the entity’s annual report to Parliament.22 23

2.14 Figure 2.2 indicates that the more complex of the 2013 MoG changes required extensive time to finalise the adjustment of financial appropriations. In some cases, this impacted the timeframes for finalising the relevant entity’s financial statements. PM&C and DSS experienced the longest delays in finalising the adjustment of appropriations. Some 371 days passed from the time the AAO was made in September 2013 until the transfer of residual financial appropriations was finalised in late September 2014.24 For PM&C and DSS, the finalisation of these 2013 transfers was also dependent on other entities finalising their appropriation transfers.25

Figure 2.2: Days taken to finalise adjustments to appropriations—2013

Source: ANAO analysis of relevant section 32 transfers under the Financial Management and Accountability (FMA) Act 1997 and section 75 transfers under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act 2013.

2.15 The significant delays encountered in finalising the 2013 MoG changes, as a result of difficulties in reaching agreement on the staff and appropriations to be transferred, especially in relation to corporate functions, is discussed in Chapter Four of this report.

2.16 The ANAO has previously reported that the 2013 MoG changes adversely affected the preparation of the 2013–14 financial statements of a small number of entities. Matters identified by the ANAO that contributed to delays included: difficulties in consolidating information from multiple systems; difficulties in reconciling different accounting approaches; and weaknesses in controls over the transfer of employee data between departments.26 The ANAO reported that:

There was … a noticeable slippage in overall timeframes in which the financial statements were completed, with less entities meeting the deadline for audit cleared statements and 15 per cent more statements being signed in the period September to November 2014, compared with 2013. This contributed to late adjustments being made to the 2013–14 Final Budget Outcome, and to a compressed timeframe for the preparation and audit of the 2013–14 Consolidated Financial Statements.27 28

There was also deterioration in the 2013–14 financial statements preparation processes in a small number of entities. Areas that required improvement included quality assurance processes, adherence to timetables and the quality of supporting working papers. The 2013 MoG changes also affected the timetable for the preparation of the 2013–14 financial statements in a small number of entities.

2.17 In contrast, the December 2014 MoG changes were completed in a relatively short timeframe—prompted in part by the Prime Minister setting a two-month timeframe for implementation and Finance’s supporting timetable. The 2014 MoG changes were significantly less complex, affecting only four departments. Only the Department of Education and Training managed multiple transfers, while DSS, the (then) Department of Industry and Science and the Department of the Treasury managed single changes. The 2014 MoG changes were completed within a few months—key changes were negotiated within two months and funding transfers were finalised within three months. As previously reported, the financial statement processes of entities affected by MoG changes improved in 2014–15.29

3. Central agency guidance and support

Areas examined

This chapter examines the guidance and support provided by central agencies to departments implementing the 2013 and 2014 Machinery of Government (MoG) changes, and the review of lessons learned.

Conclusion

The central agencies have issued a useful guide, Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Good Practice Guide (the Guide), since 2007. The Guide was updated in 2013 and 2015.a The role of central agencies in providing guidance and support has also strengthened over time, informed by the outcomes of internal review activity including the Department of Finance’s (Finance’s) assessment of lessons learned from the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes. A September 2015 decision by the Secretaries Board, informed by central agency advice on lessons learned, supports the more active involvement by Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) in setting implementation timeframes and monitoring progress.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation to help identify system-level process improvements through the continued use of post implementation reviews after major MoG changes.

Note a: A further revision of the Guide was published in July 2016: APSC and Finance, Machinery of Government Changes: A Guide for Agencies [Internet].

Did the central agencies provide useful guidance and support to entities on Machinery of Government changes, and review lessons learned?

The Department of Finance (Finance) and the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) play a key role in providing advice and support to entities on the implementation of MoG changes. The Guide developed by Finance and the APSC is a valuable resource which was used by affected departments during their implementation of the 2013 MoG changes. The Secretaries Board has recently agreed to remodel the Guide, with a focus on key principles supported by links to information and other guidance material.

The Secretaries Board considered lessons learned from the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes at its September 2015 meeting. Its consideration was informed by a lessons learned paper prepared by Finance, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the APSC. The paper drew on the outcomes of internal review activity, including Finance’s assessment of mechanisms to adjust appropriations and resolve disputes between departments.

3.1 Finance and the APSC play a central role in the MoG change process. They provide guidance on MoG change processes and requirements, and provide affected entities with support and advice regarding the implementation of the changes. Finance and the APSC also have a role in facilitating the resolution of disputes that may prevent the timely transfer of funding and resources and, more recently, have begun establishing milestones to assist agencies in meeting designated timeframes. Finance also effects the adjustment of entity funding as necessary, while the APSC effects the transfer of APS staff.

Guidance

3.2 The Guide, developed by APSC and Finance, is the key MoG change guidance document for the Australian Public Service.30 The Guide provides:

- an overview of the MoG process;

- protocols for resolving the transfer of resources;

- principles and approaches for planning and implementing MoG changes; and

- guidance on financial management and people management.

3.3 The Guide provides both high-level strategic information and more detailed information on planning, taxation, financial management, people management and records management. The Guide was updated at the time of the September 2013 MoG changes and was again updated in September 2015.31 It is publicly available from the APSC’s website and is also linked from Finance’s website.

3.4 The 14 departments surveyed by the ANAO advised that they were aware of the 2013 Guide and used it during their implementation of the 2013 MoG changes. Most departments found the Guide ‘somewhat useful’ with two departments reporting that it was ‘very helpful’. Departments also identified a number of areas where improvements to the Guide could be made, including:

- more guidance on the transfer of corporate resources through, for example, developing standard methodologies for calculating transfer balances32;

- emphasising the importance of a well-developed transition plan that has realistic timeframes; and

- returning to the more conventional approach of adjusting entities’ funding appropriations through section 75 determinations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act 2013 rather than transferring appropriations through the Budget Additional Estimates process.33

3.5 In addition to the Guide, a range of templates and checklists were used by entities implementing the 2013 MoG changes. Some of these resources were available on Finance’s website, while others such as the ‘Financial Management Checklist for Chief Financial Officers’ (CFO Checklist) and ‘Common Tasks Tool’ had been circulated by Finance to Chief Financial Officers (CFOs). Other tools, such as the ‘Property Manager’s Checklist’, were available from Finance on request.

Review of the Guidance

3.6 In September 2015, the Secretaries Board agreed that APSC and Finance update MoG guidance material, in consultation with PM&C, to link detailed information and checklists to assist practitioners. This decision was informed by a lessons learned paper and recommendations prepared by Finance, PM&C and the APSC drawing on internal review activity relating to implementation of the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes. Finance, for example, had consulted with a number of entities on key lessons learned from the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes such as costings, accommodation, property and appropriations.

3.7 The combined paper drew on an earlier Finance paper on lessons learned from the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes, which assessed mechanisms used to adjust appropriations and resolve disputes between entities.

Support by central agencies

3.8 All departments surveyed by the ANAO reported receiving some level of support from the central agencies during the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes. The responsibilities of PM&C and APSC to advise on the MoG changes and on staff movements, respectively, are usually concluded at a relatively early stage of the implementation process. Finance has a more protracted involvement and provides advice on a range of issues including the transfer of appropriations, delegations, banking arrangements and reporting requirements. During the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes, Finance took a lead role in facilitating the exchange of information between affected departments. For instance, Finance convened a forum for CFOs immediately following the announcement of the 2013 MoG changes, which was the first of a number of forums held over eighteen months. Other key actions undertaken by Finance in the first 48 hours following the 2013 MoG announcement are outlined in Box 2 in Chapter Four.

3.9 Figure 3.1 shows the overall results from the ANAO’s survey of departmental satisfaction with relevant central agencies’ support during the 2013 MoG changes.

Figure 3.1: Satisfaction with central agency support

Note: PM&C has not been included in the chart due data limitations.

Source: ANAO survey results.

3.10 A number of departments reported dissatisfaction with the support received from Finance, primarily related to the uncertainty they experienced over the transfer of appropriations, which was effected through the Budget and Additional Estimates processes rather than the more conventional process of making determinations under the financial management legislation.34 In addition, one department commented that: ‘Finance lacked an account manager approach to the MoG change meaning that the department had to engage with and at times coordinate multiple contact points within Finance to resolve integrated MoG issues (for example, MoG rules, section 32 instruments, outcomes, financial reporting).’ Finance advised the ANAO that it has since changed arrangements for those seeking to contact the department, which now includes senior management and subject matter experts being identified in central guidance, such as the CFO Checklist.

3.11 The APSC is responsible for transferring staff under section 72 of the Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act) and advising on the policy framework for determining remuneration, terms and conditions of employment and workplace arrangements. Departments were satisfied with the majority of the support they received from the APSC on:

- the transfer of staff (satisfied with 66 per cent of the support); and

- remuneration and employment conditions (satisfied with 62 per cent of the support).

3.12 In exceptional circumstances, section 24(3) of the PS Act can be used by the Public Service Minister to determine the terms and conditions of APS employees. Determinations were made by the Minister to manage a range of issues relating to the 2013 MoG changes, including:

- the immediate abolition of the Department of Employment, Education and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). APSC advised the ANAO that section 24(3) determinations were made by the Minister to preserve the terms and conditions that applied to employees under the DEEWR enterprise agreement until the Departments of Education and Employment could negotiate new enterprise agreements to cover their non-SES workforces;

- extensive staff transfers. PM&C received employees from nine other entities while DSS received employees from six. The APSC advised that section 24(3) determinations were considered necessary to combine the workforces in a way that was fair and fiscally responsible. The determinations remain in place until new enterprise agreements are negotiated to cover the departments’ non-SES workforces; and

- a number of employees experiencing more than one move before their location was finalised. For example, the immediate abolition of the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism led to all employees being moved to the Department of Industry. Tourism employees were subsequently moved to Austrade, and some were moved to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

3.13 The section 24(3) determinations came into effect on 18 September 2013—the day the MOG changes were announced. APSC advised the ANAO that there was limited opportunity to consult with affected entities prior to the decision by the Minister. The APSC did, however, advise Heads of Corporate on the day before the 2013 MoG changes were announced, of the intention to make section 24(3) determinations. The APSC also consulted with the Deputy Secretaries of affected entities on 23 September 2013. Following this meeting, the APSC convened meetings with seven entities to discuss the impact of the determinations and provide the opportunity to opt out of the arrangements specified in the determinations. Notwithstanding these consultations, a few departments indicated a level of dissatisfaction with the timeliness of APSC’s advice on the section 24(3) determination process.

3.14 The National Archives of Australia (Archives) provides entities with advice about the transfer and ownership of information, records and data.35 The only negative comment received by the ANAO concerned the timely update of Archives’ online database (RecordSearch).

Did central agencies coordinate and monitor the implementation of the Machinery of Government changes?

The role of central agencies in coordinating and monitoring the implementation of MoG changes has strengthened over time. To facilitate implementation of the 2014 MoG changes within two months, Finance established milestones for the adjustment of appropriations. In September 2015, the Secretaries Board agreed to the more active involvement by Finance and APSC in setting timeframes and monitoring implementation of future MoG changes.

There would also be merit in continuing the recent practice of conducting a post implementation review to identify further opportunities for system-level improvements, particularly following a large scale MoG change such as that announced in 2013.

3.15 The 2013 MoG changes were large scale, with 11 of the 14 affected departments managing multiple transfers. Although a timeframe was not set for implementation, the Guide noted that funding and staff transfers should be finalised ‘as soon as possible’. The departments managing larger scale changes took from seven to 12 months to finalise staff and funding transfers. Implementation monitoring was limited. In line with their broader responsibilities, Finance monitored the transfer of financial appropriations while the APSC monitored staffing transfers.

3.16 To avoid the implementation delays experienced as part of the 2013 MoG changes, the Prime Minister wrote to affected entities advising them of his expectation that the 2014 MoG changes would be finalised within two months. Finance developed a schedule of milestones and timeframes which provided the basis for monitoring the timely adjustment of appropriations. Affected departments advised the ANAO that it was helpful to have clear timeframes for the 2014 MoG changes.

3.17 In September 2015, the Secretaries Board agreed that Finance and the APSC were to continue to set timeframes, monitor progress and mediate disputes, where necessary. As discussed, their decisions were informed by a paper prepared by Finance, PM&C and the APSC drawing on lessons learned from the implementation of the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes.36 This approach is expected to facilitate the more efficient implementation of future MoG changes.37 There would also be merit in continuing the recent practice of conducting a post implementation review to identify further opportunities for system-level improvements, particularly following a large scale MoG change such as that announced in 2013. A post implementation review would involve the collection and analysis of feedback and insights from a range of stakeholders, including all entities involved in implementing the changes.

Recommendation No.1

3.18 That the Department of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission conduct a post-implementation review following major Machinery of Government changes. This report should be presented to the Secretaries Board and disseminated more widely.

Entity responses:

Department of Finance: Agreed.

3.19 Finance will continue to undertake reviews of the implementation of future MoG changes, in consultation with the Australian Public Service Commission, reporting to the Secretaries Board as appropriate.

Australian Public Service Commission: Agreed.

3.20 Reviews are conducted as a matter of current practice. The Australian Public Service Commission will work with the Department of Finance on post-implementation reviews. Such reviews will be reported to the Secretaries Board following major Machinery of Government changes and disseminated as appropriate.

Was there a mechanism to help resolve disputes?

The Guide provided for an arms-length dispute resolution mechanism with escalation points for the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes. A number of disputes were resolved using this mechanism. In September 2015, the Secretaries Board agreed to changes to the dispute resolution protocol to improve the dispute resolution process.

3.21 In the majority of cases, transferring and gaining agencies directly negotiate and agree to the final arrangements for the transfer of resources following a MoG change. However, there may be occasions where the affected agencies cannot resolve their differences and a third party process is needed to settle the matter quickly and effectively.

3.22 At the time of the 2013 and 2014 MoG changes, the Guide outlined the following dispute resolution mechanism:

When complex MoG changes occur, a committee may be set up comprising a Deputy Secretary from Finance and the Deputy Australian Public Service Commissioner, chaired by a Deputy Secretary from PM&C. The committee will play an ‘honest broker’ role to assist agencies to resolve issues, and to help ensure that MoG changes are implemented in a timely manner. If significant roadblocks emerge that cannot be quickly resolved, or there are unresolved issues outstanding at the expiration of a reasonable time, the matter will be escalated to a committee comprising the Secretaries of Finance and PM&C and the Commissioner, with the Secretary of PM&C chairing discussions. This committee will arbitrate if necessary and, ultimately, it is open to Finance to transfer funds and the Commissioner to transfer staff, without agreement if necessary. 38

3.23 Ten of the departments surveyed by the ANAO reported a significant disagreement with another entity arising from the 2013 MoG changes. Five departments reported seeking central agency help in resolving the dispute. One matter was considered and resolved by the Secretaries committee. Finance advised the ANAO that it resolved the remaining four disputes. The disputes included one protracted dispute which turned on a disagreement over $4 million.

3.24 In its June 2014 lessons learned paper on implementation of the 2013 MoG changes, Finance assessed that the average time spent working through each dispute was some five weeks, and that in all four disputes it was involved in, Finance had to make difficult arbitration decisions using inadequate information provided by entities.

3.25 A new dispute resolution protocol was agreed by the Secretaries Board in September 2015 and has been included in a new version of the Guide, published in July 2016.39 The new protocol is outlined in Box 1.

|

Box 1: New dispute resolution protocol |

|

9. It is expected that agency heads and Secretaries of the respective portfolio Departments will step in to reach a decision where agencies cannot resolve a matter at the working level. 10. It is important to advise PM&C, Finance and the APSC of any delays in finalising negotiations. They must be advised if established timeframes may not be met. If appropriate, Finance and the APSC will manage milestones and mediate between the affected entities. 11. Finance will mediate in relation to financial matters and the APSC will mediate on the staffing matters if agencies are unable to reach agreement within the established timeframe. 12. If a matter still remains unresolved and timeframes look in doubt, the matter must be escalated to a committee chaired by the Secretary of PM&C and comprising the Secretary of Finance and the Australian Public Service Commissioner. 13. Affected agencies will be informed of the protocols for taking matters to the Committee once it is clear that escalation is likely. 14. If necessary, Finance may transfer funds and the Australian Public Service Commissioner may transfer staff without the agreement of agencies. |

4. Implementing Machinery of Government changes

Areas examined

This chapter examines the overall speed and effectiveness of Machinery of Government (MoG) change implementation by affected entities, particularly the transfer of staff and appropriations, Information and Communications Technology (ICT), records and accommodation arrangements.

Conclusion

The implementation of 2013 MoG changes involved a lengthy process—ranging from four months to more than one year to complete implementation. This timeframe reflected the scale and complexity of the 2013 MoG changes, including multiple cross-entity dependencies. At times, there were contested negotiations over resources, which contributed to the length of the process.

In a June 2014 paper on lessons learned from the 2013 MoG changes, the Department of Finance (Finance) indicated that good faith negotiations had stalled at times due to some agencies not being prepared to share accurate and coherent information.

Area for improvement

The Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Good Practice Guide (the Guide) explicitly directs entities to openly and honestly identify the resources to be transferred in a MoG change. Departments of State are part of a single legal entity—the Commonwealth—and the Australian Government’s resource management framework places a positive duty on entities to cooperate with others to achieve common objectives. Information should be shared and discussed as openly as possible to expedite implementation.

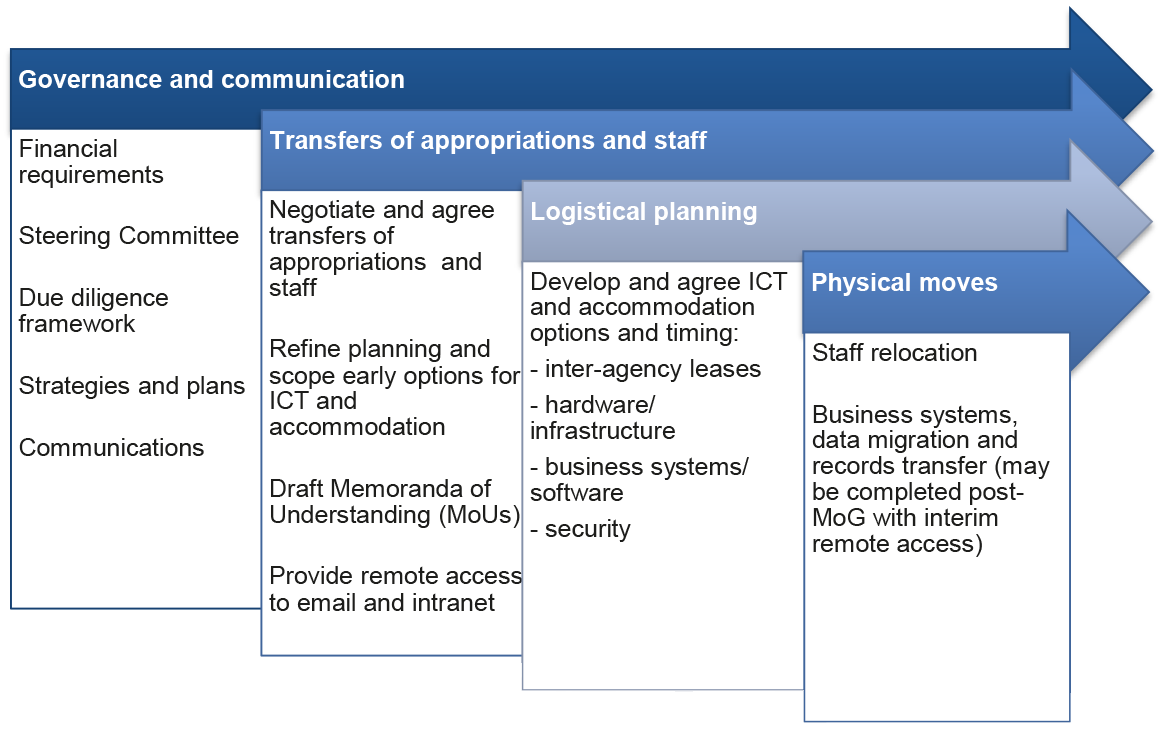

4.1 The early decisions made by an entities’ leadership are pivotal in ensuring that the benefits of MoG changes are captured, while minimising transitional risks and maintaining the delivery of programs and services. There are tangible benefits in implementing MoG changes as quickly as possible, including: providing a level of certainty for staff; clarity for external stakeholders; reliable program and budget reporting; and providing a level of assurance that government entities are focused on progressing the government’s priorities and policy agenda. Figure 4.1 summarises some of the key issues to be considered when implementing a MoG change.

Figure 4.1: Phases of implementation

Source: ANAO.

Did affected entities implement sound governance arrangements for implementing Machinery of Government changes?

ANAO’s survey and case studies indicated that the affected departments developed fit-for-purpose governance and planning arrangements that were tailored to the size and complexity of the MoG changes affecting them. Most entities surveyed by the ANAO reported that they established steering committees, undertook due diligence, developed appropriate strategies and plans, and considered legal requirements in line with the guidance material provided by Finance and the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC).

Financial requirements and early actions

4.2 Central agencies (Finance, APSC and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet—PM&C) play an important role within the first 48 hours of a MoG change announcement, both in communicating the Prime Minister’s expectations and in supporting the continued operation of government services. Finance, in particular, takes a lead role by effecting the adjustment of relevant appropriations to reflect changed entity responsibilities and communicating tasks and issues requiring immediate attention.40 Box 2 outlines early work undertaken by Finance in response to the 2013 MoG changes.

|

Box 2: Key actions by Finance within first 48 hours of 2013 MoG announcement |

|

Within the first 48 hours of the 2013 MoG changes being announced, Finance advised that it had:

Finance had also prepared additional guidance material for the 2013 MoG changes based on the lessons learned from the complex MoG changes of 2007 and 2010. This material included the updated Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Good Practice Guide (the Guide), developed with the APSC and a related guide—Implementing Machinery of Government Changes: A Financial Management Checklist for Chief Financial Officers. The checklist was first released in September 2013 and updated in December 2014. |

4.3 Departments surveyed by the ANAO indicated that establishing the correct legal and financial arrangements was critical in the early phases of implementation. For example, when Arts joined the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), AGD had to promptly:

- review the internal financial rule set (known as Chief Executive’s Instructions—CEIs—under the FMA Act and as Accountable Authority Instructions under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act 2013);

- review spending delegation limits;

- issue drawing rights to Arts staff; and

- consider the specific requirements for Arts entities that were corporate bodies.

4.4 Similarly, the Department of Social Services (DSS) advised that the transfer of the Aged Care function necessitated the review and updating of drawing rights, delegations and CEIs. DSS also provided PM&C with information on delegations, drawing rights and CEIs to facilitate the transfer of the Indigenous function to PM&C.

Governance

4.5 All affected departments reported establishing some formal governance arrangement to support the implementation of the 2013 MoG changes. Two departments—Finance and the (then) Department of Communications (Communications)—did not establish overarching steering committees for their MoG changes. These departments experienced small scale changes—Finance transferred 49 staff and Communications transferred 10 staff. In comparison, the (then) Department of Industry established a formal governance framework to implement a complex set of MoG changes involving the transfer of 1700 staff across 11 partner entities.

4.6 Table 4.1 indicates the types of governance structures established by departments affected by the 2013 MoG changes.

Table 4.1: Governance arrangements of affected departments for 2013 MoG changes

|

Type of arrangement |

Percentage of departments |

|

Steering Committee |

86 |

|

Formal Project |

71 |

|

Working group(s) |

93 |

|

Cross-agency task force |

43 |

|

Sponsor or Senior Responsible Officer identified |

79 |

|

Line/operational areas took direct responsibility |

43 |

Source: ANAO survey results.

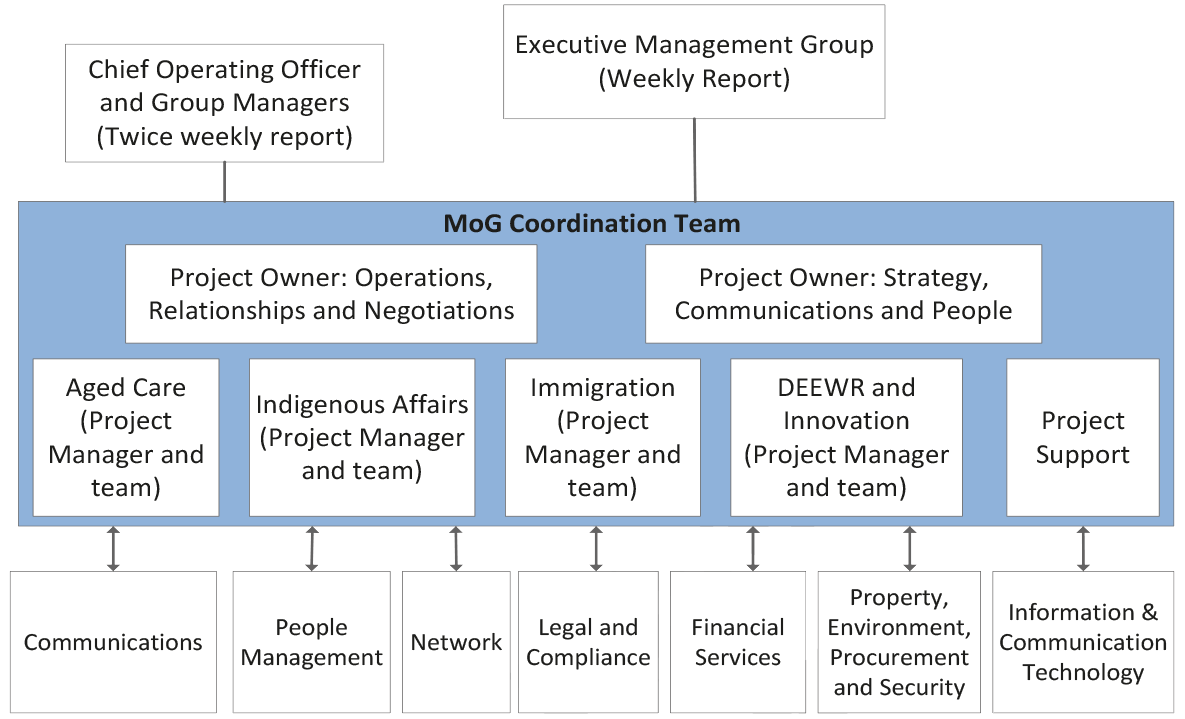

4.7 Figure 4.2 outlines the committee structure that DSS developed to support a relatively large MoG change involving the transfer of over 3000 staff across six partner entities. These governance arrangements were comprehensive and enabled the departmental executive to monitor implementation. A MoG Coordination Team reported weekly to the Executive Management Group, drawing on reports from various corporate enabling areas. Managerial staff were also taken ‘off-line’ from their business-as-usual tasks to complete the MoG changes.

Figure 4.2: DSS committee structure for the 2013 MoG changes

Source: Adapted by the ANAO from a DSS governance diagram.

4.8 AGD managed a relatively small scale MoG change—223 staff were transferred and three partner entities were involved. Its governance arrangements were smaller in scale than those used by DSS. A steering committee was established, to which ICT and corporate working groups reported. AGD also informed the ANAO that some managerial staff were taken ‘off-line’ from business-as-usual tasks to perform MoG change tasks, while other managerial staff performed MoG change tasks in addition to their business-as-usual responsibilities.

4.9 The ANAO assessed the effectiveness of the DSS and AGD steering committee arrangements against established good practices outlined in the Guide released by Finance and the APSC. Both the DSS and AGD steering committees operated effectively by making key decisions in a timely way, identifying and managing risks, monitoring and reporting on the implementation of key decisions and communicating with key stakeholders. While DSS and AGD did not include representatives from partner entities on their steering committees, both departments participated in other cross-entity committees at some level. DSS representatives were part of a cross-entity property and security working group that included the Department of Health (Health) and PM&C. AGD participated in the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s (DIRD) initial joint steering committee meetings.

Due diligence framework

4.10 The Guide emphasises that all entities gaining functions as a result of MoG changes should undertake a due diligence review of incoming functions as early as possible.41 The due diligence process should include the following:

- identifying assets and liabilities;

- registering contractual arrangements and funding agreements, including property or equipment leases and arrangements for the provision of goods and services;

- identifying whether specific programs have a statutory basis or are administrative schemes without specific legislation; and

- identifying outstanding legal action, Freedom of Information requests and audits (both internal and external).42

4.11 Eight of the 14 departments surveyed by the ANAO reported developing due diligence strategies. Each of the departments which implemented large scale changes developed due diligence strategies. The entities that did not develop a due diligence strategy typically managed smaller scale MoG changes and conducted due diligence less formally.

Strategy and planning

4.12 Table 4.2 provides an overview of the plans used by affected departments. Developing an overarching project plan allows the department to identify priorities and resources, consider risks and establish performance measures across a number of strategies and plans. Departments developed plans for key implementation activities at different stages. A number of departments noted the importance of developing a communications strategy soon after MoG changes were announced, to help engage departmental staff as part of the change management process. Typically, specific strategies for ICT, property and records management were developed at a later stage, when the staff and resources to be transferred were known.

Table 4.2: Proportion of departments that used various MoG change plans

|

MoG change plans |

Percentage of departments |

|

Overarching project plan |

71 |

|

Due diligence |

57 |

|

Communication plan |

57 |

|

Financial management plan |

86 |

|

People management plan |

86 |

|

Property |

64 |

|

Records management strategy |

57 |

|

Information and Communications Technology (ICT) plan |

71 |

Source: ANAO survey.

4.13 DSS developed fit-for-purpose transition plans and communication strategies. Overarching timeframes with specific milestones were established and responsibilities were typically allocated.. DSS established a communications working group, which reported to the steering committees established by the entities that were party to the DSS MoG changes. This helped ensure that internal communication activities within the affected agencies were consistent, targeted and timely. The communications working group developed a plan of internal activities including timing, key messages and the communication channels to be used.

4.14 AGD developed formal ICT, records management and accommodation plans. Overall, AGD’s up-front planning was less formalised than that of DSS, reflecting the smaller scale of change, with work largely directed through regular steering committee and working group meetings.

4.15 Most of the surveyed departments (86 per cent) reported having communicated to external stakeholders about the changes. In relation to the Aged Care and Arts transfers:

- DSS reported communicating with external stakeholders through website notices and physical mail-outs. DSS also reported that it arranged for key stakeholders to meet the new Minister shortly after the MoG change was announced; and

- AGD reported that it communicated with Arts stakeholders through established communication channels, and noted that its Secretary and the Attorney-General met and briefed portfolio agency heads early in the MoG change process.

Did affected entities negotiate the transfer of appropriations and staff in a timely way?

The Guide notes that agency heads are expected to undertake MoG changes ‘as soon as possible’. The transfer of staff and appropriation adjustments relating to the 2013 MoG changes took several months to complete. This was due to a number of factors, including:

a new process for adjusting appropriations which was subsequently discontinued by Finance;

significant delays in undertaking due diligence; and

difficult negotiations on the transfer of resources, including corporate staff, partly caused by a lack of open and honest engagement.

In a June 2014 paper on lessons learned from the 2013 MoG changes, Finance indicated that good faith negotiations had stalled at times due to some agencies not being prepared to share accurate and coherent information. The Guide explicitly directs entities to openly and honestly identify the resources to be transferred in a MoG change. Departments of state are part of a single legal entity—the Commonwealth—and the Australian Government’s resource management framework places a positive duty on entities to cooperate with others to achieve common objectives.

4.16 Entities are under pressure to implement MoG changes as soon as possible without jeopardising the delivery of government programs and services. Implementing the changes promptly provides a level of certainty for staff and external stakeholders, enables reliable reporting of program and budget outcomes and allows focussed implementation of the government’s priorities and policy agenda.

4.17 Figure 4.3 indicates the time taken to finalise the transfer of staff and adjust appropriations for departments that gained functions in the context of the 2013 MoG changes. Overall, appropriation adjustments took a median of 29 weeks (over six months) to finalise, and staff transfers took a median of 21 weeks (nearly five months). The shortest time taken by an affected entity to fully resolve these issues was 19 weeks (over four months); while the longest time taken was just over a year, for two entities—PM&C and DSS. In comparison, the smaller scale 2014 MoG changes were implemented relatively quickly. Over 95 per cent of annual appropriations were adjusted within six weeks, with the remainder finalised within three months.

Figure 4.3: Days to finalise incoming staff and funding transfers—2013 MoG changes

Note: Although not included in this figure, a small adjustment of appropriation in Education’s favour, of nearly $3 million, occurred on 28 March 2015.

Source: ANAO analysis of APS Employment Database (APSED) data and relevant section 32 determinations (FMA Act) and section 75 determinations (PGPA Act).

4.18 Delays in implementing the 2013 MoG changes can be attributed to a number of factors including:

- a new process of effecting appropriation adjustments through Appropriation Bills rather than section 32 instruments under the FMA Act;

- significant time taken to conduct due diligence; and

- protracted negotiations between some entities over the transfer of resources, including corporate services staff.

Transfer of funding

4.19 Finance employed a new approach for the adjustment of appropriations in the context of the 2013 MoG changes, as discussed in paragraphs 3.4 and 3.10. Many of the affected departments reported that this approach resulted in a level of confusion and delay for them. Adjustments were effected through the Budget and Additional Estimates processes rather than the more conventional process of making determinations under the financial management legislation. Finance discontinued this approach following the 2013 MoG changes, as its internal review process highlighted a number of difficulties:

The transfer of funds through Appropriation Bills rather than formal section 32 instruments proved problematic. A section 32 transfer has the effect of formally extinguishing an appropriation and creating a new appropriation providing for certainty, transparency and clear lines of responsibility and reporting. The use of Appropriation Bills did not and could not serve the same purpose as a section 32 instrument.

Due diligence investigations

4.20 A number of affected departments attributed the delays they experienced to a lack of transparency and consistency of information between gaining and losing entities. Surveyed departments indicated that the due diligence process took more time and effort than initially anticipated, with each entity approaching the process differently in relation to the scope and quality of information needed. Surveyed entities advised the ANAO that some gaining entities required more detailed information than transferring entities were able to easily provide, largely due to the different reporting structure of their corporate information systems.

4.21 This was a particular issue for PM&C, which negotiated with nine departments on the transfer of staff and resources. PM&C advised that it spent time developing a due diligence template to collect this information for various functional areas (such as ICT, finance and human resources). The ANAO was advised that once the template was developed, a number of transferring entities had difficulty responding to the questions, and in many cases entities had to manually collect the relevant data as reports were not easily extracted and separated from corporate information systems.

4.22 Surveyed departments suggested there would be merit in a more standardised approach to due diligence, for example, by providing a link to a due diligence template in the Guide. Entities also suggested better aligning the date of effect of AAO changes with routine financial reporting dates (for example, the end of a month) to lessen the administrative burden on affected entities and help streamline the change process. Finance advised that due diligence templates are now provided to entities as a standard practice.

4.23 The Guide outlines a number of key principles that should be adopted by Australian Government entities responsible for implementing MoG changes. A number of these principles relate to adopting a co-operative approach to negotiations, with a view to achieving the best outcome from a whole-of-government perspective rather than the best outcome for individual entities. Achieving this outcome involves good faith negotiations, based on open and honest identification of resources, and the timely and accurate exchange of information.

4.24 Figure 4.4 shows that while surveyed departments reported that a collaborative and collegiate approach was usually taken by other departments to support implementation of the 2013 MoG changes, nearly 50 per cent of departments were of the opinion that other departments had only ‘sometimes’ or ‘rarely’ prioritised whole-of-government goals or outcomes over their own positions and interests.

Figure 4.4: Application of whole-of-government principles by other departments

Note: Figure 4.4 aggregates surveyed departments’ assessments of the conduct of their primary partner department in the MoG change.

Source: ANAO analysis of survey results.

4.25 In its June 2014 lessons learned document on the 2013 MoG changes, Finance observed that:

- good faith negotiations had stalled at times due to some entities not being prepared to share accurate and coherent information; and

- the transparency of some entities’ financial position became problematic, especially when gaining entities believed that good faith negotiations were no longer achievable. This caused disputes to arise.

4.26 The Guide explicitly directs entities to openly and honestly identify the resources to be transferred in a MoG change. The ANAO observed that where the leadership of affected entities encouraged open and honest disclosure, negotiations were more productive and changes were implemented more efficiently. Departments of State are part of a single legal entity—the Commonwealth—and the Australian Government’s resource management framework places a positive duty on entities to cooperate with others to achieve common objectives.43 Information should be shared and discussed as openly as possible to expedite implementation.

Corporate staff transfer negotiations

4.27 The Guide notes that as a general rule, unless exceptional circumstances apply, the number of corporate services staff transferred will generally be in proportion to the number of program staff leaving the transferring agency. Gaining agreement to the transfer of corporate services staff was reported by affected departments as being more difficult than the transfer of more clearly defined program and policy elements. In particular, surveyed departments identified difficulties in negotiating corporate overheads as the principal reason for delay in progressing the 2013 MoG changes. In its June 2014 paper on lessons learned from the 2013 MoG changes, Finance also observed that the ‘staff follow function’ principle is harder to apply for corporate activities such as Human Resources, ICT and the CFO unit.44 A number of affected departments suggested that the use of a standard methodology to identify the cost of resources to be transferred may assist this process. The ANAO observed that affected entities typically used Finance’s New Policy Proposal template—which is a standard methodology—to help cost the resources to be transferred, including corporate resources.

4.28 Table 4.3 summarises the key issues relating to staff transfers reported by departments. A number of the responses suggest that difficulties encountered in negotiating the transfer of resources were partly caused by a lack of open and honest engagement.

Table 4.3: Staff transfer issues reported by affected departments

|

Issue |

Reported causes |

|