Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of the Sydney Airport Demand Management Act 1997

The objective of the audit was to assess the implementation and administration of the movement limit and the Slot Management Scheme at Sydney Airport.

The scope of the audit included the development and administration of the SADM Act. The scope also included the development and administration of the relevant legislative instruments and determinations, particularly those which put in place the monitoring and compliance frameworks that support the legislation.

Summary

Background

Sydney Airport is a major international gateway and cargo airport and a key element of Australia's economic and transport infrastructure. It is set amid densely populated urban areas, relatively close to the city centre.

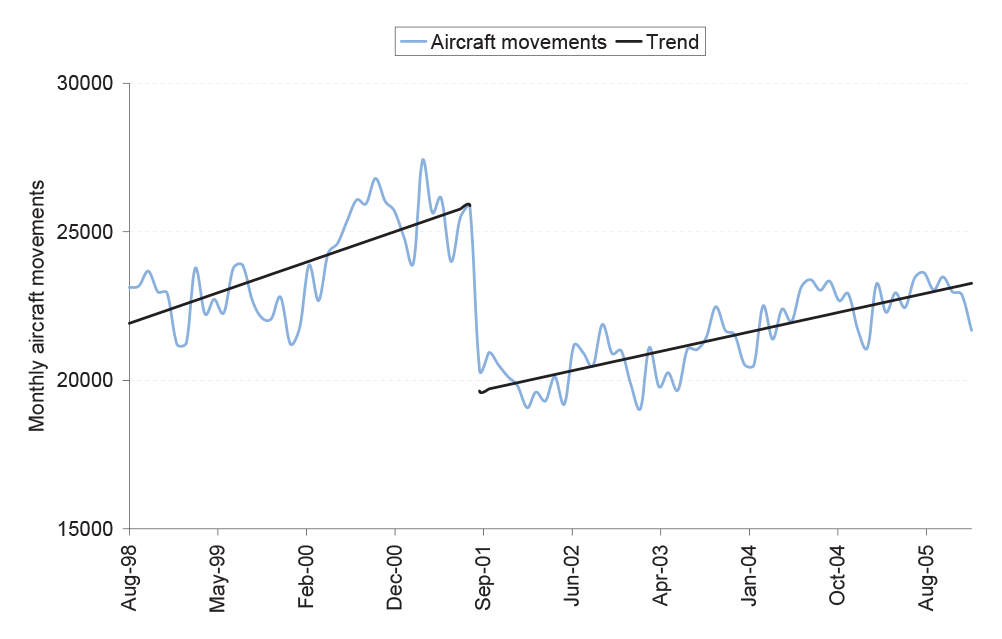

The following figure outlines monthly aircraft movements at Sydney Airport since 1998. It highlights the volatile nature of aviation demand, with the effects of the September 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States exacerbated in Australia by the collapse of Ansett Airlines. While aircraft movement growth at Sydney Airport has resumed, it is at a slower rate than prior to the events of September 2001 such that monthly movements have only recently returned to the levels observed before the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games.

Figure 1: Monthly aircraft movements at Sydney airport since 1998

Within the civil aviation industry, approaches to managing airport demand have evolved to improve the use of tightly constrained airport facilities. In this context, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) has developed procedures (called the Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines) to provide guidance on the allocation of available capacity and coordination of airline schedules. However, IATA has acknowledged that, where sovereign nations have in place legislation to govern the management of demand, this legislation takes precedence over the Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines.

The Sydney Airport Demand Management Act 1997 (SADM Act) provides the framework for the long-term management of demand at Sydney Airport. The SADM Act is intended to meet the commitment made by the Government prior to the March 1996 Federal election that aircraft movements at Sydney Airport would be capped at 80 per hour. In this respect, the requirements of the SADM Act take precedence over voluntary coordination practices advocated by IATA, and in place at other major Australian airports.1

In the second reading speech for the legislation, Parliament was advised that the demand management arrangements would:

- help alleviate delays caused by congestion at Sydney Airport;

- spread aircraft movements more evenly within hours;

- safeguard the levels of access that regional New South Wales has to Sydney Airport;

- provide for any potential new entrants to have equal access with their established competitors to slots at Sydney Airport; and

- ensure a workable and effective means of administering the movement limit.

The demand management scheme for Sydney Airport comprises the SADM Act and legislative instruments made under the Act. The SADM Act limits aircraft movements at Sydney Airport to a maximum of 80 per hour. Each arm of the operational requirements created by the SADM Act is put into effect by legislative instruments made under the Act. The two most important are:

- the Slot Management Scheme, under which aircraft operators are required to seek a slot (a permission to undertake an aircraft movement) from the Slot Manager;2 and

- the Compliance Scheme, which requires operators to carry out authorised aircraft movements within a prescribed tolerance period before or after the scheduled slot time. The Compliance Scheme also deals with certain matters concerning the application of penalties to aircraft operators who operate aircraft without a slot or outside of the prescribed tolerances.

The combined action of these two instruments is intended to implement the movement limit, by controlling the scheduling of aircraft movements under the Slot Management Scheme and requiring timely performance through the Compliance Scheme.

The SADM Act commenced on 17 November 1997, with the movement limit and penalties for unauthorised aircraft movements coming into effect on 17 May 1998. Both the Slot Management and Compliance Schemes were made by determination of the then Minister for Transport and Regional Services during 1998. The Slot Management Scheme commenced operation on 25 March 1998, and the Compliance Scheme on 25 October 1998. Since the commencement of the scheme, there have been over 190 000 regulated hours and approximately two million aircraft movements.

The Department of Transport and Regional Services (DOTARS)3 is responsible for the implementation and administration of the SADM Act. Airservices Australia is responsible for monitoring and reporting on compliance with the aircraft movement limit.

Audit Objective

The objective of the audit was to assess the implementation and administration of the movement limit and the Slot Management Scheme at Sydney Airport.

The scope of the audit included the development and administration of the SADM Act. The scope also included the development and administration of the relevant legislative instruments and determinations, particularly those which put in place the monitoring and compliance frameworks that support the legislation.

Overall Audit Conclusions

The primary purpose of the SADM Act was to give effect to the Government's commitment to limit aircraft movements at Sydney Airport to 80 per hour. DOTARS had primary responsibility for the development of the delegated legislation that gives effect to the SADM Act. In doing so, the Department consulted with a range of parties, including airlines and representative groups. This approach was necessary to meet the underlying policy goals that the slot management arrangements be workable in the industry's interests and be developed and implemented by the industry in a cooperative manner. In this respect, DOTARS has advised ANAO that the scheme is held in high regard by industry and that there is a high degree of voluntary cooperation. However, ANAO's analysis is that elements of the legislative scheme are unclear, do not operate in the way intended or are ineffective.

Slot allocation is a complex process that, for international airports, has to fit within a world-wide structure. Slots at Sydney Airport are currently allocated and managed in a manner that aligns closely with the Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines issued by IATA. The Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines acknowledge that, where sovereign nations have in place legislation to govern the management of demand, this legislation takes precedence over the Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines. However, the allocation and management of slots at Sydney Airport does not accord with the SADM Act and its subordinate legislative instruments.

Under the SADM Act, almost all aircraft operators who wish to land at, or take off from, Sydney Airport must apply for and be granted a slot under the Slot Management Scheme. Slot allocation has the capacity to ensure that movement limit breaches do not occur, depending on the number of slots allocated in any given period, and the timeliness of the subsequent aircraft operations. However, the Slot Management Scheme does not include an express limit on the number of slots that can be allocated, and there has been at least one occasion on which more than 80 slots were allocated in a regulated hour. In an environment of increasing aircraft movements, there is also a risk to future compliance with the movement limit in circumstances where slot allocations are made at or near 80 movements per regulated hour.

The intent of the Sydney Airport Compliance Scheme is that aircraft operators comply with the requirement to obtain a slot for a proposed aircraft movement and, having done so, take reasonable measures to ensure the proposed movement occurs as planned. The SADM Act established a system of penalties for unauthorised aircraft movements so as to protect the integrity of the movement limit, and establish clear guides for airport users as to the range of sanctions that may be levied in the form of an infringement notice or civil prosecution.4

There is evidence of a high number of unauthorised aircraft movements (movements without a slot and movements outside the slot tolerances) having occurred at Sydney Airport. However, since the scheme commenced in 1998, no infringement notices have been issued to operators or other penalties applied.

In addition, there are other factors which indicate that the demand management scheme is not being administered as intended. These include:

- the Compliance Committee chaired by DOTARS has not effectively applied the Compliance Scheme's provisions for identifying unauthorised aircraft movements; and

- some operators that have not been exempted by the legislation are, nevertheless, not required to submit data on their aircraft movements thereby enabling them to operate outside the jurisdiction of the scheme.

Further, the SADM Act requires Airservices Australia to monitor and report breaches of the movement limit to the Parliament through its Minister. However, reliable and accurate records do not exist to evidence past monitoring of compliance with the movement limit, and support the reports made to the Parliament. The available data indicates that some of the 61 reported breaches may not, in fact, have occurred. This data also indicates that there may have been many other, unreported, breaches of the movement limit. This position should be considered in the context of approximately two million aircraft movements since the commencement of the scheme. The available data shows that breaches occurred prior to September 2001 when there were higher overall numbers of aircraft movements at Sydney Airport. The risk of future breaches will increase when the scheduled numbers of aircraft movements at Sydney Airport return to pre-September 2001 levels.

Against this background, the management of aircraft demand at Sydney Airport needs to give more emphasis to the legislative requirements put in place specifically to manage aircraft movements. In this respect, Airservices Australia and DOTARS have already taken steps in a number of areas to improve administration of the demand management scheme. These steps include:

- Airservices Australia is planning to introduce new technology to enhance its ability to meet its obligations to monitor aircraft movements at Sydney Airport. This is at least three years away and, in the meantime, other steps are underway to improve data collection, processing and reporting; and

- DOTARS has written to the Slot Manager and Airservices Australia reinforcing the primacy of the legislation over industry guidelines, emphasising the importance of delays being managed through the Compliance Scheme and stressing the need for operators to obtain a new slot where they are unable to use a slot on the day for which it was allocated.

Having regard to the improvement initiatives already underway, ANAO has made six recommendations relating to:

- the development and implementation of performance information and performance reporting that addresses the demand management scheme's objectives;

- addressing deficiencies in the legislative framework, including the fundamental issue of clear and effective aircraft movement definitions;

- implementation of slot allocation and management processes that comply with legislative requirements (rather than industry-preferred procedures) and promote adherence to the movement limit; and

- effective and equitable compliance arrangements that address all unauthorised aircraft movements.

Key Findings

Performance information and reporting (Chapter 2)

The demand management scheme was introduced more than eight years ago. DOTARS has advised ANAO that it considers the broad policy objectives for the demand management scheme have been largely met. However, the Department has not established performance measures for any of the objectives for the scheme that were advised to the Parliament. In addition, since 2001–02, there has been an absence of any performance reporting on the management of the scheme and the extent to which its objectives have been achieved.

In this context, the extent to which the demand management scheme objectives have been achieved is not well demonstrated by supporting information. Indeed, in some key areas nominated as important in the second reading speech for the legislation, the available data indicates that administration of the demand management scheme has yet to deliver the intended outcomes. In particular, ANAO found that:

- after the introduction of the Slot Management Scheme, aircraft movement timeliness at first deteriorated, returning to 1998 levels by 2004;

- in terms of improving the distribution of scheduled aircraft movements, there has been little, if any, significant change in the overall distribution of allocated slots within the day; and

- there has been a significant reduction in the number and share of slots allocated to regional operators. In this respect, ANAO was advised by DOTARS that the decline in the regional airline share of the total traffic at Sydney Airport has been in line with market changes and conditions and that there has been a move to larger aircraft.

The legislative framework (Chapter 3)

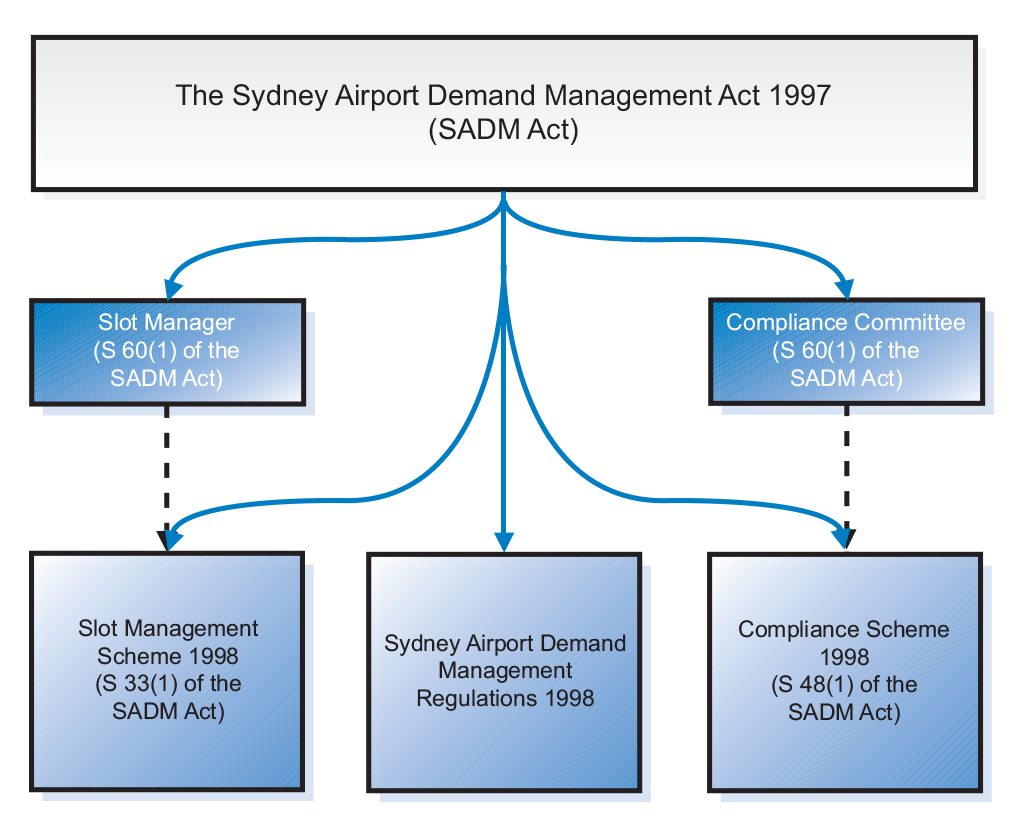

The SADM Act prescribes Parliament's intention to limit aircraft movements through a Slot Management Scheme, in combination with penalties to encourage compliance. This intention is then given effect by determinations and regulations made under the SADM Act. The operation of the SADM Act is outlined primarily in legislative instruments. The most significant of these are:

- the Sydney Airport Slot Management Scheme, which outlines the processes for the allocation and management of aircraft movement slots; and

- the Sydney Airport Compliance Scheme, which sets out how compliance with the slot management arrangements under the SADM Act and the Slot Management Scheme are to be enforced.

The following figure summarises the delegated legislation that was intended to give effect to the demand management scheme.

Procedural issues

The SADM Act sets out requirements for the development of the Slot Management Scheme and the Compliance Scheme, including the processes to be followed. ANAO found that in neither case did the available records demonstrate that the procedural requirements have been met. Specifically:

- rather than the Slot Manager being appointed and then developing a draft Scheme for submission to the Minister as required under the SADM Act, the available records show that the Scheme was both developed and submitted for Ministerial approval prior to the appointment of a Slot Manager; and

- the SADM Act assigns to the Compliance Committee the responsibility for developing, administering and amending the Compliance Scheme. However, at the time that members of the Compliance Committee were being appointed, development of the Compliance Scheme was largely complete and the Compliance Committee did not meet until after the Compliance Scheme was made into law.

Adherence to the procedural requirements when the Schemes are amended, or re-made, will provide greater assurance about their validity.

Definition of aircraft movement

The concept of ‘aircraft movement' underpins the operation of the demand management scheme. In this respect, valid and effective definitions of aircraft movement are necessary to underpin:

- the allocation of slots;

- the enforcement of compliance with the requirement to have a slot and operate in accordance with the allocated slot time; and

- incumbent aircraft operators retaining historical precedence to slots they have previously operated.

The definition of aircraft movement in the SADM Act relates to movements of aircraft on and off runways. Airservices Australia's monitoring of the movement limit accords with this definition.

A different definition is used to administer the Slot Management Scheme and the Compliance Scheme. This definition relates to movements from gates, and was adopted for ease of administration by the industry. During the course of the audit, ANAO drew attention to this inconsistency in the definition/interpretation of aircraft movement, which is fundamental to the effective operation of the demand management scheme. Legal advice subsequently obtained by DOTARS was that:

In so far as the definitions in the Compliance Scheme are inconsistent with the Act, they are invalid and of no effect. However, while this invalidity has important consequences for the administration of the SADM Act, the Slot Management Scheme and the Compliance Scheme, I do not think that it necessarily makes the Act unworkable or the Schemes as a whole invalid or otherwise unworkable.

DOTARS advised ANAO in February 2007 that the Slot Management Scheme and the Compliance scheme are premised on definitions of ‘take off' and ‘land' consistent with worldwide practice.

Slot allocation (Chapter 4)

The Slot Management and Compliance Schemes were to give effect to the government's commitment to cap aircraft movements at Sydney Airport at 80 movements per hour through the implementation of a slot system.7 This system was to require an aircraft operator to both have a slot and conduct their authorised aircraft movement within a certain period of time before or after the scheduled slot time. Hence, the movement limit would be implemented by controlling the scheduling of aircraft movements and by encouraging timely performance.

Under the SADM Act, almost all aircraft operators who wish to land at, or take off from, Sydney Airport must apply for and be granted a slot under the Slot Management Scheme. Slots may be allocated singly, as a group for a special event, or as a series for a regular scheduled service. The slot gives permission for a specified aircraft movement at Sydney Airport at a specified time on a specified day. Accordingly, an effective Slot Management Scheme is a prerequisite for:

- operators to obtain a slot to take off or land at Sydney Airport; and

- action to be possible against operators that land or take off without a slot, or outside their slot.

The Slot Manager

The allocation of slots is undertaken by a Slot Manager, who is to receive applications for slots, assess applications against the priorities set out in the Scheme and allocate slots accordingly. The Slot Manager is a proprietary company registered in New South Wales whose shares are owned by the lessee of Sydney Airport and the airline industry.8 ANAO found that DOTARS' ability to oversight the allocation and management of aircraft movement slots at Sydney Airport has been adversely affected by the absence of appropriate arrangements for the Commonwealth to access the records of the Slot Manager.

Slot allocation practices

ANAO found that the allocation and management of aircraft movement slots at Sydney Airport has not complied with the requirements of the demand management scheme. During the course of the audit, action was taken to address most of these issues, as outlined below.

Authorisation of Airservices Australia to allocate and manage slots

Outside of the Slot Manager's business hours, Airservices Australia allocates and manages slots on behalf of the Slot Manager. However, Airservices Australia had not been effectively authorised to undertake these functions.

Airservices Australia and the Slot Manager entered into a new deed of agreement on 22 August 2006. The new deed runs until terminated by the parties. Airservices Australia advised ANAO on 24 August 2006 that the new deed now allowed Airservices Australia to manage slots already allocated by the Slot Manager, as well as those allocated by Airservices Australia for short notice, unscheduled flights on the day of operation. However, Airservices Australia recognises that there is scope to remove some remaining ambiguity in this new authorisation to make the extent of the authorisation clear.

Cancelling slots and requesting a new slot when aircraft are in transit

A practice has been adopted of allowing operators to cancel a slot and request a new slot for an aircraft delayed in transit or delayed on the ground at Sydney Airport. In December 2006, DOTARS wrote to the Slot Manager9 in the following terms:

The practice of some operators to request a new slot while the aircraft is in transit is inappropriate and may circumvent accountability under the compliance scheme. I would appreciate the assistance of ACA in reminding operators that it is not in the spirit of the slot management regime to change the on-time compliance requirements for an aircraft already in transit by requesting a new slot. Any delay in the arrival time at Sydney Airport needs to be managed through the compliance regime.

Reinforcing the primacy of the SADM Act over industry guidelines

Slots have been allocated in the manner advocated by the IATA Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines rather than in accordance with the priorities and processes set out in the Slot Management Scheme. DOTARS' December 2006 correspondence with the Slot Manager reinforced the principle that, where there is inconsistency between the slot management regime established by the SADM Act and the IATA Worldwide Scheduling Guidelines, the legislative arrangements are to prevail.

Historical precedence

One intention of the Slot Management Scheme was that an aircraft operator that operates a scheduled aircraft movement using a slot gains historical precedence to being allocated this slot in future scheduling seasons (so long as allocation of the slot does not conflict with the movement limit or lead to an unacceptable degree of clustering of aircraft movements). However:

- the historical precedence provisions of the Slot Management Scheme are unclear; and

- the historical precedence provisions are not being fully applied in the slot allocation process. In particular:

- a ‘use-it-or-lose-it' test exists to ensure that operators that have been allocated slots operate aircraft movements using those slots. However, there was no evidence of this test being applied in the allocation of slots. Further, some movements that did not occur have been deemed to have occurred so that the operator retained historical precedence to the slot; and

- a ‘size of the aircraft' test exists to produce efficiency gains at Sydney Airport by addressing whether the size of aircraft being used accords with the size of the aircraft which the operator stated it would be using in its application for a slot. However, there was no evidence of this test being applied in the allocation of slots.10

DOTARS has obtained legal advice that agrees there is room for clarifying the operation of the historical precedence provisions in the Slot Management Scheme. ANAO Recommendation No.3 proposes that these provisions be clarified and that DOTARS take steps to oversight the slot allocation process in order that the statutory rules governing historical precedence are applied in full.

Compliance and enforcement (Chapter 5)

The intent of the Compliance Scheme is that aircraft operators comply with the requirement to obtain a slot for a proposed aircraft movement and, having done so, take reasonable measures to ensure the proposed movement occurs as planned. Accordingly, the Compliance Scheme prohibits an aircraft operator knowingly or recklessly operating:

-

without a slot (referred to as a no-slot movement); or

-

outside the set tolerances for the allocated slot (referred to as an off-slot movement).

In the second reading speech for the legislation, Parliament was informed that:

Under the compliance system airlines will be liable to fines and other penalties for poor on-time performance. This is a crucial element of the slots system which will provide airlines with an additional incentive to perform on-time. Because off-slot movements may involve fines unless an acceptable reason exists, the system will also bring transparency and accountability to a process of explaining why delays occur into and out of Sydney Airport.11

Revenue from penalties is to be used to offset the costs of administering the slot management scheme. To achieve this, fines are to be paid to Slot Manager on behalf of the Commonwealth. An equivalent amount is then appropriated (through a Special Appropriation at section 27(4) of the SADM Act) from the Consolidated Revenue Fund back to the Slot Manager for the purposes of the Slot Manager carrying out its functions under the SADM Act.

DOTARS advised ANAO in February 2007 that anecdotal advice from airlines suggests that internal airline practices have been improved as a result of the compliance provisions of the slot management arrangements.

Compliance Committee

The enforcement of the demand management system is undertaken by a Compliance Committee that is chaired by DOTARS and includes representatives from Airservices Australia, the Sydney Airport lessee and the airline industry. The Slot Manager attends as an observer.

During the course of the audit, DOTARS advised ANAO that it would take action to address concerns raised by ANAO about records of the Compliance Committee's operations and decisions. In addition, ANAO found there are opportunities to enhance the quality of decision making by improving the quality and relevance of information referred to the Committee for assessment.

Identifying, assessing and responding to unauthorised movements

Neither the SADM Act nor the Compliance Scheme compel aircraft operators to provide the relevant movement data to support the current Compliance Scheme. ANAO found that this data was missing for some 18 per cent of all aircraft movements. The Slot Manager advised ANAO that it seeks to follow up with aircraft operators to obtain missing data. Nonetheless, infrequent or irregular visitors to Sydney Airport (referred to as ‘itinerant' aircraft) often do not provide movement data. These operators, who have been responsible for many thousands of aircraft movements over the life of the demand management scheme, effectively avoid being assessed in terms of their compliance with the demand management scheme.

Penalties for unauthorised aircraft movements were included in the SADM Act so as to protect the integrity of the movement limit and establish clear guides as to the range of sanctions that may be levied if an infringement occurred. Specifically, the second reading speech informed the Parliament that:

- The most serious breaches relate to no-slot movements, where an aircraft lands or takes off without having permission to do so. This was viewed as a fundamental breach of the slot system which jeopardises the movement limit and disrupts other airport users who have applied for a slot. No-slot movements were to be punishable by a maximum penalty of $220 000 per infringement.

- The maximum penalty for an off-slot movement is $110 000 for a corporation or

$22 000 for an individual. It was proposed that the Compliance Scheme would provide initially for relatively small fines, but persistent offenders would find an exponential increase in the level of fines for the second and third offences, up to the maximum. It was noted that fines would not be triggered unless a flight was outside tolerance,12 and off-slot movements that are outside the control of the operator would not count.

The data that is available shows that since the scheme commenced, there have been at least 600 no-slot movements and at least 8 000 off-slot movements at Sydney Airport. However, there have been no infringement notices issued to operators or other penalties applied since the scheme commenced.

The SADM Act defines a no-slot movement as a movement occurring on a day for which the operator has not had a slot permitting the movement allocated. In this respect, operators need to be aware that unless a new slot is obtained where a slot is not able to be used on the day for which it has been allocated (while the aircraft is on the ground), the operator may be prosecuted for a no-slot movement. However, 600 of these no-slot movements were mistakenly identified as off-slot movements.

The 8 000 off-slot movements which occurred (according to the terms of the Compliance Scheme) were also not identified. The Compliance Committee's practice has been to apply alternative rules based on IATA procedures. Consequently, the Committee has identified few of the off-slot movements which occurred under the terms of the Compliance Scheme.

Effectively responding to unauthorised aircraft movements requires:

- closer adherence by the Compliance Committee to the legislated requirements for identifying and assessing unauthorised aircraft movements;

- examination of options for verifying, on a risk management basis, the veracity of reasons given by operators for movements occurring outside their slot tolerances;

- more equitable and effective treatment of slots that are allocated as part of a slot group or series;

- an assessment of the merits of extending the infringement regime to no-slot movements;13

- the introduction of procedures to assess and document operators' compliance with the requirement that they use their allocated slots as a prerequisite to retaining historical precedence to such slots in subsequent scheduling seasons; and

- an assessment of the merits of seeking to obtain the investigatory powers that would be necessary to establish whether offences have been committed by operators.

The movement limit (Chapter 6)

Whether the movement limit might be breached is affected by the number of slots allocated in any regulated hour (the higher the number allocated, the greater the likelihood of a potential breach) and the timeliness of aircraft movements. For total actual aircraft movements to remain below the movement limit, slot allocations should allow for unforeseen circumstances which might otherwise increase aircraft movements above the limit.

In this context, ANAO found there has been at least one instance in which the Slot Manager has allocated more than 80 slots in a regulated hour. In an environment of increasing aircraft movements, there is also a risk of future non-compliance with the movement limit in circumstances where slot allocations are made at or near 80 movements per regulated hour.14

Breaches of the movement limit

Section 9 of the SADM Act requires Airservices Australia to monitor compliance with the movement limit and provide quarterly reports to the Minister on the extent of infringements (if any) of the limit in the quarter. The Minister must table any report received in each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after the day on which the Minister received the report.

A total of 61 breaches of the movement limit have been reported to the Minister and tabled in Parliament as having occurred between March 1998 and March 2006. The last reported breached occurred in May 2001.

In aggregate, 64 per cent of all reported breaches involved the movement limit being breached by one or two movements. However, accurate and reliable records do not exist to support past monitoring of compliance with the movement limit on which the reports made to the Parliament were based. The available records indicate both that some of the reported breaches may not have occurred, and that there may have been as many as 357 additional breaches of the movement limit that were not reported to the Minister and Parliament. This position should be considered in the context of approximately two million aircraft movements since the commencement of the scheme.

Airservices Australia has commenced action to improve the accuracy of its monitoring and reporting of breaches of the movement cap

Agency Responses

Detailed responses to the audit report were provided by DOTARS and by the Slot Manager and are included in Appendices 3 and 4 respectively. DOTARS and Airservices also provided summary responses as follows:

DOTARS' response

The ANAO findings highlight the complex nature of aircraft operations and the need for flexibility in order to maintain certainty for airline schedules, maximise operational efficiency and avoid unnecessary disruption of scheduled passenger services, while implementing arrangements designed to alleviate the impact of aircraft noise on the community.

The Department acknowledges the ANAO's finding that working definitions for key terms in both the Sydney Airport Demand Management Act 1997 and the slot and compliance schemes associated with the Act are inconsistent and that criteria for the allocation of slots are not sufficiently clear. The Department has advanced its consideration of the issues raised by the audit and has, amongst other things, initiated action to seek agreement to the passage of legislative amendments to address this. Amendments to the slot and compliance schemes as a consequence of the ANAO Report will be progressed in accordance with the procedures set out in the Act.

Sydney Airport is Australia's major international and domestic airport and the efficiency of its airport operations at Sydney Airport are critical to national economic performance. There have been more than 2 million aircraft movements over approximately 190,000 regulated hours since the commencement of the demand management scheme at Sydney Airport in 1998. Within this context, and in the absence of any breach of the maximum movement limit since 2001, the Department considers that airport slots should continue to be allocated up to the current statutory maximum movement limit.

Finally, the ANAO report estimates that there may have been some 357 unreported breaches of the movement limit. The Department considers that the requirement for Airservices Australia to report on the maximum movement limit provides an independent validation of the actual aircraft movements. As the potential unreported breaches are not able to be verified, the Department has no basis for taking the matter further.

In addition, the Department advised ANAO in February 2007 that it is preparing a Discussion Paper to present, in broad terms, its response to the audit recommendations and outline a range of proposals (including possible legislative and procedural changes) intended to clarify elements of the SADM Act and the slot and compliance regimes. The Department further advised ANAO that, to ensure that the appropriate process improvements are discussed and agreed early thereby taking advantage of the momentum generated by the audit, it would be discussing these issues with the Slot Coordinator, Airservices Australia, Sydney Airport Corporation Limited and representatives of airlines and airline groups that use Sydney Airport at the next quarterly meeting of the Sydney Airport Compliance Committee.

Airservices Australia's response

Airservices Australia takes its responsibilities in relation to the Sydney Airport Demand Management Act 1997 very seriously. Considerable effort has been directed at meeting those obligations as well as improving the ways in which Airservices records and reports on aircraft movements at Sydney Airport.

These efforts will continue and Airservices Australia has a high degree of confidence in our ability to provide accurate movement cap reports to the Minister and through him, the Parliament.

Airservices Australia does not accept that there have been more cap breaches at Sydney Airport than the 61 already reported to the Parliament, although we do acknowledge that our past administrative practices have resulted in an absence of documentary evidence to support our processes. That is, whilst data analysed by the ANAO indicates a higher number of instances where more then 80 movements were recorded, this data was legitimately verified and modified by reference to the tower flight strips (that were not retained by Airservices). The absence of contemporaneous flight strips therefore makes it impossible to determine the final status of those instances.

In response to this audit, Airservices now retains strips indefinitely even though International Civil Aviation Organisation regulations still do not require flight strips to be retained beyond 30 days.

This audit represents the first time this legislation has received external scrutiny since it received Royal Assent a decade ago. As the Audit Office has found, the issues and processes the legislation covers are complex and involve several organisations.

For its part, Airservices Australia welcomes any initiatives taken as a result of this audit to ensure that the legislation meets the Government's objectives and enables agencies to better meet their stated accountabilities.

Footnotes

1 The voluntary coordination of scheduled movements between Australian Airports is a long-standing practice. International terminal coordination commenced at Sydney and Melbourne in 1971. Brisbane, Perth and Darwin airports followed suit, as have Adelaide, Townsville and Cairns as their international arrivals have grown.

2 The Slot Manager, Airport Coordination Australia Pty Ltd (ACA), was appointed by the Minister and is a proprietary company registered in New South Wales. At June 2006, the holders of its 1 000 issued shares were the Sydney Airport Corporation Limited (10 per cent), Qantas Airways Limited (41 per cent), Virgin Blue Airlines Pty Ltd (35 per cent) and the Regional Aviation Association of Australia (14 per cent).

3 The Transport and Regional Services Portfolio was formerly the Transport and Regional Development Portfolio. The name change occurred as part of revised administrative arrangements in 1998. For consistency, all references in this report are to the Minister for Transport and Regional Services (the Minister) and the Department of Transport and Regional Services (DOTARS).

4 Sydney Airport Demand Management Bill 1997, second reading speech, House Hansard, 25 September 1997, p. 8536.

5 Sydney Airport Demand Management Act 1997 – Slot Management Scheme 1998, Explanatory Statement issued by the authority of the Minister for Transport and Regional Development, pp. 1 & 2.

6 Sydney Airport Demand Management Act 1997 – Compliance Scheme 1998, Explanatory Statement issued by the authority of the Minister for Transport and Regional Development, p. 1.

7 A slot is not required for movements during the curfew period. Nor is a slot required for a movement for which the Slot Coordinator gives a dispensation (in exceptional circumstances), nor for emergency aircraft or for state aircraft.

8 In addition to administering the slot allocation arrangements legislated for Sydney Airport, the Slot Manager provides airport coordination services for all major Australian airports.

9 As Airservices Australia is authorised to perform certain of the Slot Manager's duties, DOTARS provided Airservices Australia with a copy of its correspondence to the Slot Manager.

10 The ‘size of the aircraft test' applies to those slots for which the size of aircraft was decisive in granting the application for the slot.

11 House Hansard, Sydney Airport Demand Management Bill 1997, second reading speech, 25 September 1997, pp. 8536 and 8537.

12 The Compliance Scheme specifies a rate of fine for off-slot movements, at section 5. However, there is no provision setting fines for no-slot movements. While infringement notices may be issued for no-slot movements, no fine can apply, effectively negating the intention of section 20 of the SADM Act in respect of no-slot movements. See further at paragraph 6.7.

13 The Compliance Scheme specifies a rate of fine for off-slot movements, at section 5. However, there is no provision setting fines for no-slot movements. While infringement notices may be issued for no-slot movements, no fine can apply, effectively negating the intention of section 20 of the SADM Act in respect of no-slot movements.

14 See further at paragraph 6.7.