Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation Partnership

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Reef Trust Partnership (RTP) was established by a grant awarded through a non-competitive process. The ability to leverage the $443.3 million grant to raise funds from the private and philanthropic sectors was a key reason the foundation was given the grant. After receiving the grant, a fundraising target of $357 million was set, including $157 million in cash.

Key facts

- The foundation, along with contracted research and delivery partners, is to spend at least $822 million to improve the health of the Great Barrier Reef.

- As at 31 December 2020, the foundation had spent or committed $154.8 million and research and delivery partners had been contracted to contribute a further $46.5 million. The foundation reported fundraising was impacted by the 2018–19 external environment and COVID-19.

- The $157 million cash fundraising target does not have to be received or spent by the end of the RTP.

What did we find?

- The design and early delivery of the RTP has been partially effective.

- The Australian Government grant has been appropriately invested.

- The foundation reports having raised $53.6 million to December 2020, of which the majority is from in-kind contributions.

- While competitive selection processes have been employed most of the time when awarding grant funding, there has been insufficient use of open and competitive approaches for procurements.

- As the grant agreement does not define what constitutes RTP administration costs, the foundation has applied its own internal business rules.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made seven recommendations addressing bank deeds, fundraising, subcontracting the delivery of reef protection projects and administration costs.

- The foundation agreed to all seven recommendations.

$684,100

reported cash raised to December 2020 through individual giving, corporate donors and philanthropists against a $157 million target.

$285.7m

of Australian Government grant funding still to be spent by the foundation on improving the health of the reef.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. On 28 June 2018, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE1 or the department) paid a $443.3 million grant to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation (the foundation). To be delivered over six years, the objective of the ‘Reef Trust Partnership’ (RTP or the partnership) grant is to ‘achieve significant, measureable improvement in the health of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area’.

2. The total value of the partnership over its six years is estimated to be $822 million. This comprises:

- the Australian Government grant funding of $443.3 million, with funding allocated to six components: administration of the partnership by the foundation; water quality improvement; crown-of-thorns starfish control; reef restoration and adaptation science; Indigenous and community engagement; and integrated monitoring and reporting;

- interest earned by the foundation on the grant funds, of which the first $21.8 million may be applied to the foundation’s administration costs with any interest above that amount applied to one of the project delivery components of the partnership; and

- $357 million the foundation has targeted to raise by leveraging the Australian Government grant funds. This comprises $200 million by way of in-kind contributions from delivery partners the foundation contracts with and $157 million in cash fundraising.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. This is the second audit examining the Australian Government’s $443.3 million partnership with the foundation. The first audit, Auditor-General Report No. 22 2018–192, focused on the assessment and decision making processes that led to the award of an ad hoc grant to the foundation through a non-competitive process.

4. As of March 2021, the $443.3 million grant to the foundation is the largest Australian Government grant that has been reported on the Department of Finance’s GrantConnect website. In responding to the first audit, DAWE identified that the partnership with the foundation was an innovative model that could be adopted to address other policy priorities for Australia. In addition, the department stated that the foundation had ‘established an ambitious fundraising target of $300-400 million’ (the ability to leverage Australian Government funding to raise funds from the private and philanthropic sectors was a key reason the foundation was awarded the grant funding).

5. Given the strong parliamentary and public interest in the partnership, this audit was undertaken to examine the implementation of the partnership.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to examine whether the design and early delivery of the Australian Government’s $443.3 million partnership with the foundation has been effective.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- Has the grant funding been appropriately invested by the foundation since the commencement of the partnership?

- How successful has the foundation been in using the grant to attract co-investment?

- Is an appropriate approach being taken to the delivery of the partnership, including through subcontractors?

- Is the amount being spend on administration and fundraising costs under control?

Conclusion

8. The design and early delivery of the Australian Government’s $443.3 million partnership with the foundation has been partially effective.

9. The $443.3 million Australian Government grant has been appropriately invested. The majority of the funds have been held in various term deposits with six banks, with 81 per cent of the grant amount still in term deposits as at 31 December 2020. The department and the foundation did not ensure that bank deeds were always in place to protect the Australian Government’s interests for each of the term deposits. Interest earnings are expected to be sufficient to provide at least $21.825 million in funding towards the foundation’s costs of administering the partnership.

10. While the foundation has established an overarching target of leveraging the Australian Government grant to raise $357 million, there are no interim targets which would enable it to track its progress and measure its success to date. The foundation reports having raised $53.6 million to December 2020, of which the majority (99 per cent) is from in-kind contributions.

11. The foundation’s use of grants and procurements is an appropriate approach to delivering the partnership. While competitive selection processes have been employed most of the time when awarding grant funding, there has been insufficient use of open and competitive approaches for procurements. For grants awarded through non-competitive processes and for the majority of procurements (both competitive and non-competitive), it has been common for selection criteria to not be specified. In addition, written contracts have not always been put in place by the foundation.

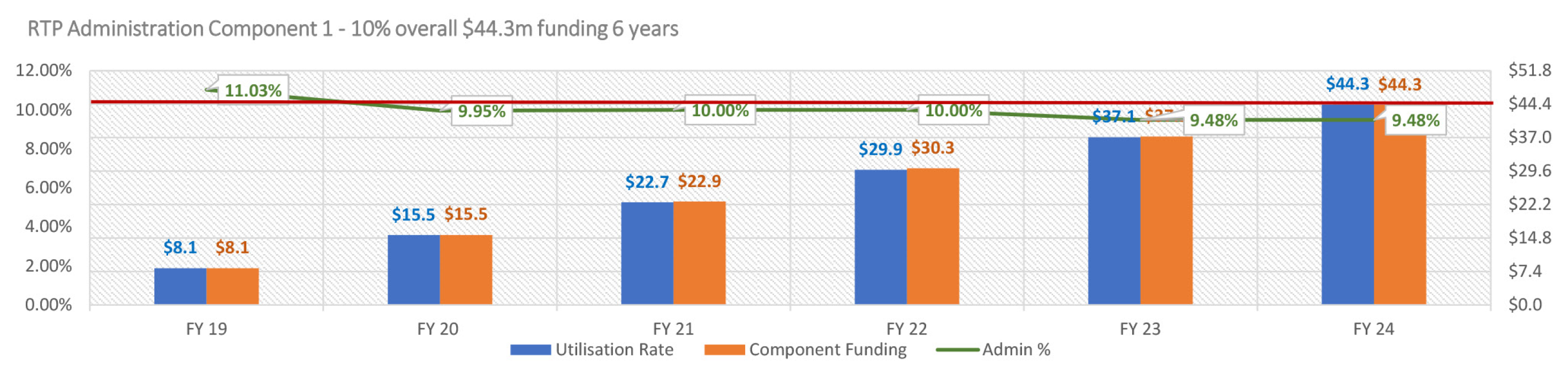

12. The foundation has reported to the department that it had spent or has committed to spend $19.7 million on administration and fundraising to 31 December 2020, and budgets that it will not exceed the capped provision of $44.3 million for its administration and fundraising costs over the remaining three and a half years of the partnership. As the grant agreement does not define what constitutes partnership administration costs, the foundation has applied its own internal business rules to decide which costs are allocated against the capped provision, and which it can allocate to the project delivery components of the partnership. The foundation has not consistently implemented arrangements to cap the administration costs of its subcontractors.

Supporting findings

Investment of grant funds

13. On 25 July 2018, the foundation invested $434.33 million (98 per cent of the upfront grant) into a portfolio of nine term deposits with six Australian banks. The remainder of the grant was retained in the foundation’s RTP operating account, with further funds transferred to the operating account over time as they have been required to meet costs. As of 31 December 2020, $358.7 million (81 per cent of the grant amount) was invested in various term deposits.

14. The approach to selecting banks for term deposits was appropriate. The approach to selecting investment advisers was not open or sufficiently competitive.

15. In accordance with the grant agreement, investment in term deposits with six Australian banks has been ‘conservative and not speculative’. The security of the investments has been undermined by bank deeds not always being in place to cover term deposits with two of the six banks.

16. Investments are on track to generate more than the $21.8 million income needed to fund the foundation’s administration costs. Interest above that amount is required to be applied to project delivery components of the partnership.

Using the grant to leverage other funding

17. Co-investment targets were set by the foundation in September 2018, agreed to by the department on 10 October 2018 and published on the foundation’s website two days later. Across four fundraising streams, the overall target is to raise $357 million by June 2024 comprising $200 million of in-kind contributions from research and delivery partners and $157 million in cash contributions. While the published co-investment strategy states that the fundraising campaign would increase RTP investment by $300 million to $400 million over the six years to 30 June 2024, the grant agreement does not require that leveraged funds be received or spent during the term of the partnership.

18. As at December 2020, 70 delivery partners had identified that they would make in-kind contributions totalling $53.1 million towards projects that, combined with others, were to receive Australian Government funding of $134.3 million (a contribution rate of 39 cents for each dollar granted). In total, 30 per cent of the promised in-kind contributions were not included in the grant agreements and contracts signed by the foundation meaning funding recipients were not obligated to deliver their promised contribution. In addition, for the small number of projects that have been completed and acquitted, it has been common for partner contributions to be less than promised, with 23 per cent of the expected in-kind contributions not reported as having been provided by the partner, with inconsistent follow-up action being taken by the foundation in respect to the shortfalls in contributions.

19. The foundation has secured a total of $684,100 in cash contributions. This comprises $504,099 secured from individuals against the $7 million individual giving target over the life of the partnership. One commitment of $180,000 has been secured from a corporate donor, compared with a target from corporate donors of $50 million by 30 June 2024, and no commitments have yet been secured against the June 2024 $100 million target that is focused on philanthropists.

20. As interim fundraising targets have not been set, it is difficult to assess whether appropriate progress is being made towards the fundraising targets. By 31 December 2020, $5.5 million has been reported as raised through cash contributions and acquitted in-kind contributions from research and delivery partners against the overall target of $357 million. In addition to the acquitted in-kind contributions, a further $46.5 million of in-kind contributions has been contracted to be received.

Project delivery

21. The major delivery methods used by the foundation, being subcontracting through grants and procurement, are appropriate. Subcontracting is provided for in the head agreement between the foundation and the Australian Government. That agreement requires the foundation to generally apply the principles of open, transparent and effective competition, value for money and fair dealing and to use rigorous and robust assessment criteria.

22. The majority of grants awarded and grant funding has involved competitive processes. There has been insufficient use of open and competitive processes when undertaking procurements. Despite the foundation’s procurement policy advocating the use of competitive processes, in practice the most common procurement approach employed has been to sole source providers, with 71 per cent of the 171 procurements analysed by the ANAO having no competition and the foundation often exempting itself from employing a competitive approach. The foundation has undertaken seven open tender processes for its higher value procurements, notwithstanding the expectation outlined in its policy for open tenders for all procurements with a value above $250,001 (of which there have been 14).

23. The foundation has not consistently adopted and applied appropriate selection criteria. While appropriate criteria have been developed and applied when awarding grants through competitive processes (more than 90 per cent of grants contracted) this has not been consistently the case with grants awarded through non-competitive processes. Only 22 per cent of procurement processes had clearly identified criteria.

24. Written contracts have not been put in place for all expenditure that has occurred under the partnership. It has been common for appropriate contractual arrangements to be in place for project delivery arrangements, which has been largely undertaken through grant agreements. The absence of written contracts largely involved procurements relating to the administration of the partnership.

Administration costs

25. Up to 31 December 2020, the foundation had reported total expenditure on administration and fundraising costs of $18.5 million with a further $1.2 million in commitments. This leaves $24.6 million available to spend on administration and fundraising over the remaining three and a half years of the partnership.

26. An appropriate methodology is in place to calculate, and benchmark, administration and fundraising efficiency of the partnership for the purposes of public reporting. The foundation has obtained consultancy advice on its approach, and this included a comparison to a sample of three Australian-based major environmental conservation focused not-for-profit entities. Reporting by the foundation is that its spending on partnership administration over the six years to 30 June 2024 will not exceed the capped provision of $44.3 million.

27. The head agreement between the Australian Government and the foundation does not define what is considered an administration cost (and is therefore subject to the cost cap). The foundation has applied its own internal business rules to decide which costs are to be counted against the capped provision for administration of the partnership, and which costs can be allocated against the five non-administration components of the partnership.

28. Fully effective arrangements are not in place to limit the administration cost of subcontractors to the contracted cap of 10 per cent.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.23

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation and the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment ensure a bank deed protecting the Australian Government is in place before any Reef Trust Partnership funds are invested with a financial institution.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.21

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation:

- include the extent to which funding candidates will provide a cash or in-kind contribution as a selection criterion for all project delivery grants and procurements; and

- follow up with partners where acquittals do not demonstrate that contracted contributions have been provided in full.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.38

In consultation with the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation develop, agree and report against interim fundraising targets for each stream of the approved co-investment strategy so as to provide a better indication of how much of the fundraising target will be received by the end of the Reef Trust Partnership on 30 June 2024.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.28

To ensure compliance with the Reef Trust Partnership agreement, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation increase the extent to which it uses open and competitive selection processes to undertake procurements.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.42

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation:

- specify clear selection criteria for all granting opportunities and procurement processes, including those that do not involve a competitive selection process; and

- record an assessment against those criteria in advance of taking any decisions to commit to spending Reef Trust Partnership funding.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.52

To ensure compliance with the Reef Trust Partnership agreement, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation strengthen its subcontracting controls to ensure a written contract that contains all of the applicable provisions required by the head agreement with the Australian Government is in place before any subcontractor commences work.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 5.24

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation in consultation with the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, strengthen its approach to implementing the cap on administration costs of subcontractors.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

29. The proposed audit report was provided to the foundation. The foundation’s summary response is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

30. Extracts of the proposed audit report were provided to DAWE. The department’s summary response is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation

The Foundation welcomes the Auditor-General’s findings in the report, and is pleased to note comments in relation to the appropriateness of:

- Investment of grant money.

- Major delivery models.

- The Foundation’s methodology for calculating and benchmarking administration and fundraising efficiency.

These are significant milestone achievements that reflect the hard work of our team, our volunteer Board of Directors and Committee members, and the many dedicated and passionate partners the Foundation works with to deliver projects that are vital to the survival of the Great Barrier Reef.

The Foundation notes the Auditor-General has identified improvement opportunities in some aspects of the delivery of the RTP. The Great Barrier Reef Foundation agrees to, and has commenced the implementation of, all seven recommendations in the report. We are committed to the continuous improvement of our processes and procedures and will establish (where required) and strengthen (where already in place) arrangements to ensure successful implementation of improvements.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment

The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (the department) is committed to appropriate and timely implementation of agreed recommendations to both ANAO and parliamentary committee reports. The department welcomes the report’s findings that will help strengthen the implementation of the Australian Government’s signature investment in the Great Barrier Reef.

There have been seven recommendations made in this report, three of which the department will be responding to directly. All recommendations for the department relate to strengthening our existing controls for the administration of this very important grant. We welcome the opportunity to continue to work in partnership with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation to improve these controls and apply those learnings to our grant management practices more broadly.

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation are midway through delivering the grant aimed at protecting the Great Barrier Reef. We look forward to reporting the outcomes of their on-ground projects in the coming years.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Procurement

Grants

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 On 28 June 2018, the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE or the department)3 paid a $443.3 million grant to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation (the foundation). To be delivered over six years, the objective of the ‘Reef Trust Partnership’ (RTP, or the partnership) grant is to ‘achieve significant, measureable improvement in the health of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area’. The partnership funding is divided into six ‘components’ (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Summary of the six components of the Reef Trust Partnership

|

Component name |

Component objective |

Funding |

|

|

1 |

Administration |

Ensure good governance is in place, including systems and processes, and that effective project management and scaling-up activities are being undertaken. |

$22,505,000a |

|

2 |

Water Quality |

Address water quality improvement targets impacting the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (the reef) through activities such as improved farming practices, reduced fertiliser user and uptake of new technology and land management practices. |

$200,649,000 |

|

3 |

COTS Control |

Expand efforts to control Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS) to reduce coral mortality from COTS outbreaks in order to protect high ecological and economic value coral reefs in line with Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority’s COTS Control Strategy. |

$57,800,000 |

|

4 |

Reef Restoration and Adaptation Science |

Conduct and implement science activities to deliver and support reef restoration and adaptation for the reef. |

$100,000,000 |

|

5 |

Indigenous and Community Reef Protection |

Improve the engagement of traditional owners and the broader community in the protection of the reef including, but not limited to, increasing compliance and enforcement action against poaching, as well as greater involvement of traditional owners in sea country management through improved and expanded use of traditional marine resource agreements. |

$22,349,000 |

|

6 |

Integrated Monitoring and Reporting |

Support the implementation of the Reef 2050 Plan Reef Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program including eReefs and the Paddock to Reef monitoring and reporting programs, to improve health monitoring and reporting of the reef to ensure that monitoring and our reporting to UNESCO is scientifically robust and investment outcomes are measurable. |

$40,000,000 |

Note a: In addition to this amount, the funding agreement allows for the foundation to use the interest that it earns on the upfront grant to cover the costs it incurs in performing component one, so long as the total amount of RTP funding used for administration activities does not exceed ten per cent of the total grant amount (that is, no more than $44.33 million).

Source: ANAO analysis of RTP funding agreement.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.2 This is the second audit examining the Australian Government’s $443.3 million partnership with the foundation. The first audit, Auditor-General Report No. 22 2018–194, focused on the assessment and decision-making processes that led to the award of an ad hoc grant to the foundation through a non-competitive process.

1.3 As of March 2021, the $443.3 million grant to the foundation is the largest Australian Government grant that has been reported on the Department of Finance’s GrantConnect website. In responding to the first audit, DAWE identified that the partnership with the foundation was an innovative model that could be adopted to address other policy priorities for Australia. In addition, the department stated that the foundation had ‘established an ambitious fundraising target of $300-400 million’ (the ability to leverage Australian Government funding to raise funds from the private and philanthropic sectors was a key reason the foundation was awarded the grant funding).

1.4 Given the strong parliamentary and public interest in the partnership, this audit was undertaken to examine the implementation of the partnership.

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.5 The objective of the audit was to examine whether the design and early delivery of the Australian Government’s $443.3 million partnership with the foundation has been effective.

1.6 To form a conclusion against the objective the following high level criteria were applied:

- Has the grant funding been appropriately invested by the foundation since the commencement of the partnership?

- How successful has the foundation been in using the grant to attract co-investment?

- Is an appropriate approach being taken to the delivery of the partnership, including through subcontractors?

- Is the amount being spent on administration and fundraising costs under control?

Audit scope and methodology

1.7 The audit was conducted under paragraph 18B(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 which enables the Auditor-General to audit Commonwealth partners such as the foundation. The audit scope included the planning, design and implementation activities undertaken by the foundation for the delivery of the partnership. DAWE was included in the scope due to its role as the Australian Government administering entity of the partnership.

1.8 The audit methodology included examination of foundation and DAWE records and engagement with key staff.

1.9 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $785,500.

1.10 The team members for this audit were Amy Willmott, Kai Swoboda, Tessa Osborne, Jessica Carroll, Swatilekha Ahmed and Brian Boyd.

2. Investment of grant funds

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the $443.3 million grant had been appropriately invested by the foundation since the commencement of the Reef Trust Partnership (RTP or the partnership).

Conclusion

The $443.3 million Australian Government grant has been appropriately invested. The majority of the funds have been held in various term deposits with six banks, with 81 per cent of the grant amount still in term deposits as at 31 December 2020. The Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE or the department) and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation (the foundation) did not ensure that bank deeds were always in place to protect the Australian Government’s interests for each of the term deposits. Interest earnings are expected to be sufficient to provide at least $21.825 million in funding towards the foundation’s costs of administering the partnership.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the management of bank deeds be improved.

2.1 To enable the grant to the foundation to be accounted for in 2017–18, it was paid in full on 28 June 2018 and some key process-related and governance controls were not able to be included in the funding agreement.5 The agreement requires that the investment of the grant by the foundation be conservative and not speculative. It also permits the foundation to use up to $21.825 million of the interest earned on grant funds on administration with any interest earned above this amount to be used on non-administration components of the RTP.

2.2 The ANAO examined whether the foundation has invested the grant funds to earn sufficient interest to assist paying for the administration of the RTP; and ensured adequate security for the Australian Government over the grant funding.

Where has the grant funding been invested?

On 25 July 2018, the foundation invested $434.33 million (98 per cent of the upfront grant) into a portfolio of nine term deposits with six Australian banks. The remainder of the grant was retained in the foundation’s RTP operating account, with further funds transferred to the operating account over time as they have been required to meet costs. As of 31 December 2020, $358.7 million (81 per cent of the grant amount) was invested in various term deposits.

2.3 The partnership agreement was signed on 28 June 2018 and $443.3 million was paid into the foundation’s RTP operating account6 on 29 June 2018.

2.4 Funds could not be invested elsewhere until the foundation had finalised a written investment policy. The grant agreement required that DAWE be consulted prior to the policy’s finalisation. The policy was approved by the foundation board on 4 July 2018 and endorsed by DAWE on 12 July 2018.

2.5 Under the policy, $434.3 million was placed into nine fixed-interest term deposits across six Australian banks on 25 July 2018. For scaling-up activities, $9 million was retained in the operating account.

2.6 The foundation’s investment approach has remained largely unchanged over time, with funds being invested in up to 17 concurrent term deposits with between four and six of the same banks at any one time. As of 31 December 2020, $358.7 million (81 per cent of the grant amount) remains invested in term deposits.

Have the investments and investment advisers been selected through appropriate processes?

The approach to selecting banks for term deposits was appropriate. The approach to selecting investment advisers was not open or sufficiently competitive.

2.7 The investment committee of the foundation’s board was responsible for overseeing the investment of the grant; the appointment of advisers; and developing the investment policy required by the grant agreement.

2.8 The committee agreed at a 19 June 2018 meeting that potential advisers would be contacted directly by committee members. Two separate advisers were engaged in July 2018 to:

- advise on the short-term investment policy and assist in developing its longer term strategy; and

- arrange the initial three month tranche of term deposits while the longer-term policy was refined.

2.9 Mercer Investments (Australia) Limited (Mercer) was engaged through a sole source arrangement for $25,000 after being selected by the investment committee and approved by the chair of the board. The committee identified Mercer at its 19 June 2018 meeting as the most appropriate adviser for investment instruments in the short and long term.

2.10 A proposal from Mercer was provided directly to two Investment Committee members (who were also foundation directors) on 13 July 2018, and while it was noted that it was ‘not cheap’, directors considered it would ‘help address board concerns and assure government’; and it was considered prudent to have a ‘best in class’ adviser due to the expected scrutiny of investment decisions.

2.11 Laminar Capital (Laminar) was engaged initially for four months to coordinate the short-term investments after being identified in mid-June 2018 by a committee member as one of two firms to quote through a limited tender process. While Laminar’s proposal represented the most competitive option between the two responses7, it has since been retained on an ongoing basis at a 40 per cent higher rate of $3,500 per month (for the same services under a new client services agreement).8 Payments to 31 December 2020 totalled $114,950. The increased rate was approved in March 2019 and retrospectively applied to monthly services provided since November 2018.

2.12 The partnership agreement requires the foundation to ‘generally award’ each subcontract in accordance with principles of open, transparent and effective competition, value for money and fair dealing. Where the foundation elects to engage subcontractors other than as a result of an open, competitive process, it is required to report to DAWE the reasons and justifications for the approach taken.

2.13 In its July to December 2018 six-monthly report to DAWE, the foundation reported that it had engaged Mercer through a non-competitive process so as to ‘comply with a direction of the board’. It did not report that Laminar was not engaged through an open and competitive process.

Investments selection

2.14 Recommendations for the investment portfolio composition were provided by Laminar, after seeking quotes from banks on a pre-approved list. The list was from the foundation’s short-term investment policy and included 10 banks9 (four of which were subsidiaries of other banks on the list). The foundation provided Laminar with the approved list on 12 July 2018 and had previously indicated having ‘existing banking relationships with CBA and BOQ’.

2.15 Rates were obtained from all six parent banks.10 An initial recommendation was provided to the investment committee on 23 July 2018 for a portfolio of eight terms deposits with an average duration of less than four months and weighted average yield of 2.70 per cent. The investment committee requested a modified portfolio, for reasons including:

- BOQ carrying 24.5%11 of the portfolio may be a bad optic considering Board composition12, despite offering the best rates

- Reticence to lock the funds away for 3-6 months, suggesting some funds are tied up for a lesser period ie more laddered portfolio

- ANZ inflexibility with regards to term deposit breaks, with CBA offering almost identical returns with more flexibility.

2.16 After some adjustments within the following 24 hours, approval was provided to Laminar on 24 July 2018 to execute its revised recommendation reflecting a ‘laddered portfolio’ with:

- a reduced concentration in both ANZ (from 11.5 to six per cent) and BOQ (from 34.5 to 17 per cent); and

- an average yield of 2.60 per cent (down from 2.70 per cent) and a reduced average duration from four down to three months.

2.17 The term deposits were executed on 25 July 2018.

Are the investments that have been made with the grant funding appropriately secure?

In accordance with the grant agreement, investment in term deposits with six Australian banks has been ‘conservative and not speculative’. The security of the investments has been undermined by bank deeds not always being in place to cover term deposits with two of the six banks.

2.18 The grant agreement allows the foundation to invest the portion of funding not yet needed to deliver projects. While it allowed the foundation to decide these investments, they were to be in a manner ‘consistent with sound commercial practice’ and other requirements in the grant agreement. Those other requirements included:

- investment of the grant to be conservative and not speculative;

- investment of the grant in ‘investment grade financial products with a long-term rating of BBB or higher by Standard and Poor’s or Moody’s’;

- not investing in any ‘related body corporate’ or ‘related entity’13 of the foundation, unless the entity is listed on the Australian Securities Exchange; and

- no part of the grant being invested in derivative financial products except for hedging risk.

2.19 The foundation’s investments to date have been in term deposits with six Australian banks, which has been consistent with these requirements.

Bank deeds

2.20 The drafting of the grant agreement signed in June 2018 did not contemplate the placement of the grant into bank accounts other than the foundation’s RTP operating account, for which a bank deed was to be executed. Following the investment into term deposits, it was considered necessary to execute individual bank deeds with each bank. The deeds provide the department with control over the unspent funds in certain circumstances, including in the event the grant agreement is terminated.

2.21 The grant agreement was varied in March 2019 to ensure, among other things, that term deposits are explicitly considered to be a ‘bank account’ for the purposes of the partnership head agreement. This was to secure the Australian Government’s interests in the unspent funds and was in addition to the bank deeds executed between August and October 2018 for the term deposits.

2.22 Relevant accounts are specified in appendices to the deeds with each bank and should be amended each time a new account is opened. Deeds were revised in early 2019 to accommodate term deposits rolling over into new accounts and executed by three banks. Action was taken with respect to the other three banks within the course of the audit. Specifically:

- although a variation to the deed with Westpac was signed in July 2020, the 2018 Westpac deed already accommodated the rolling over of term deposits by referencing a suspense account for the foundation’s current term deposits;14

- a new deed was signed with CBA on 18 December 2020. Apart from a period between January to April 2019, term deposits have been held with CBA; and

- a new deed was signed with ANZ on 24 February 2021. While the foundation confirmed with DAWE in July 2020 that it did not currently hold any funds with ANZ, a new term deposit was placed with ANZ on 7 August 2020.

Recommendation no.1

2.23 The Great Barrier Reef Foundation and the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment ensure a bank deed protecting the Australian Government is in place before any Reef Trust Partnership funds are invested with a financial institution.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment response: Agreed.

2.24 The department puts a high priority on the security of the funds granted to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and notes that bank deeds are now in place for all the financial institutions where funds are held. The department agrees to work with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation to continue to strengthen the management of bank deeds.

Is the investment approach and performance on track to generate sufficient income to help fund the administration costs of the foundation?

Investments are on track to generate more than the $21.8 million income needed to fund the foundation’s administration costs. Interest above that amount is required to be applied to project delivery components of the partnership.

2.25 Since the initial July 2018 investment, term deposits have been rolled over into new investments based on the interest rates being offered by the portfolio banks at the time of maturity. The foundation’s November 2020 forecasting indicated that it is on track to generate $5.3 million in excess of the $21.8 million capped interest amount that can be used to help pay for its administration of the RTP.

Term deposit durations

2.26 The July 2018 investment policy was envisaged to be short-term, with a longer-term policy to be developed later to cover longer duration investments. The short-term policy required that funds be invested in term deposits with a maximum four-month average duration and concentration of no more than 51 per cent in any one bank.

2.27 In September 2020 the foundation advised the ANAO that finalisation of the longer-term policy was placed on hold in October 2018 until after the 18 May 2019 Federal Election. This decision was taken following a September 2018 announcement by the opposition that should it win the May 2019 Federal Election it would require the foundation to return the unspent portion of the grant. The need to revise the policy was recognised throughout 2019, for reasons including the:

- likelihood that future interest rates would decline, rather than increase; and

- inability ‘to take advantage of current interest rates and invest funds for a longer period of time’ due to the policy’s four-month average duration constraint.

2.28 Although this work was progressed in 2019, the policy was not updated in time to remove the four month average duration restriction before this was exceeded in September 2019. The updated policy was approved in May 2020 and no longer includes this restriction. The first term deposit to be rolled over following the election matured on 21 May 2019 (one term deposit with a value of $51 million) with the remainder between 13 and 28 June 2019.15 By mid-March 2020, the average weighted duration had increased to over 17 months. This situation is illustrated by Figure 2.1. In April 2021, the foundation advised the ANAO that:

The Foundation’s Investment Committee was able to confidently consider longer duration term deposits once management had completed a drawdown schedule for forward program funding requirements. This work was completed in February 2020 and facilitated the finalisation of the updated policy in March 2020.

Figure 2.1: Term deposit interest rates and duration over time

Note a: Until the July 2018 investment policy was amended in May 2020, the maximum average duration of the portfolio of term deposits could not exceed four months.

Source: ANAO analysis of foundation records.

3. Using the grant to leverage other funding

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Great Barrier Reef Foundation (the foundation) has been successful in using the grant to attract co-investment from other sources.

Conclusion

While the foundation has established an overarching target of leveraging the Australian Government grant to raise $357 million, there are no interim targets which would enable it to track its progress and measure its success to date. The foundation reports having raised $53.6 million to December 2020, of which the majority (99 per cent) is from in-kind contributions.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations relating to the foundation:

- improving its approach to securing contributions from research and delivery partners; and

- adopting interim fundraising targets so as to provide a better indication of whether the foundation is likely to achieve the overall target of raising $357 million and, if so, by what date.

3.1 The ability to leverage Australian Government funding to raise funds from the private and philanthropic sectors for improving the health of the Great Barrier Reef was a key reason the foundation was awarded the grant funding through a non-competitive granting process.16 The ANAO examined the performance of the foundation in targeting and attracting co-investment since the $443.3 million grant was paid in June 2018.

Have co-investment targets been set?

Co-investment targets were set by the foundation in September 2018, agreed to by the department on 10 October 2018 and published on the foundation’s website two days later. Across four fundraising streams, the overall target is to raise $357 million by June 2024 comprising $200 million of in-kind contributions from research and delivery partners and $157 million in cash contributions. While the published co-investment strategy states that the fundraising campaign would increase Reef Trust Partnership (RTP or the partnership) investment by $300 million to $400 million over the six years to 30 June 2024, the grant agreement does not require that leveraged funds be received or spent during the term of the partnership.

3.2 The grant agreement signed in June 2018 did not specify the amount of financial and/or in-kind contributions that the foundation would raise from other parties. Rather, the funding agreement required that the foundation develop and finalise a ‘Co-Financing Strategy Plan’ by 30 September 2018, that would:

- outline the foundation’s principles and approach to co-financing for the five financial years commencing from 2019–20; and

- set out how the foundation would leverage the up-front payment of the grant to raise ‘other contributions’ as defined in the funding agreement.

3.3 In developing the strategy, the foundation undertook some desktop research, consulted with two organisations17 it identified as having comparable fundraising campaigns and commissioned an external peer review focussed on the philanthropic-related elements of the strategy. After a short process of consultation with the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE or the department)18 and some resulting editorial adjustments, the foundation provided the final co-financing strategy to the department on 30 September 2018.

3.4 The department advised the foundation on 10 October 2018 that the contractual requirements for the strategy had been met and it was publicly released on 12 October 2018.19 Across four streams each with a five year campaign, the strategy established an overarching fundraising target of $357 million.

3.5 As illustrated by Table 3.1, the majority ($200 million) of the target relates to in-kind contributions from research and delivery partners. The foundation forecast that it would raise those contributions by leveraging the $420.8 million in RTP funding allocated across the five non-administration components of the partnership. This represents an overall leverage percentage of 48 cents in the dollar.20

Table 3.1: Fundraising component summary

|

Stream |

Description |

Targeta |

|

Raised Funds |

||

|

Capital campaign |

The largest marine science fundraising campaign in Australia – an intensive fundraising campaign with a focus on philanthropy and individual giving tied to the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP). |

$100m |

|

Corporate giving |

Developing corporate partnerships with iconic Australian businesses that deliver impact and enable planned programs, specific initiatives and activities. |

$50m |

|

Individual giving |

Five-year strategy developed to build awareness of GBRF and acquire new individual donors through regular giving, planned giving, bequests and community fundraising. |

$7m |

|

Contributed Funds |

||

|

Research and delivery partners |

Formal agreements with collaborators on projects across the RTP portfolio with an initial focus on RRAP that accurately capture the cash and resource investment made by research and delivery partners. |

$200mb |

Note a: The co-financing strategy states that these targets are the ‘median within a forecast target range’. This was not the case. Rather, a decision was taken by the board on 24 September 2018 to report a range of $300 million to $400 million, rather than the sum of the individual targets ($357 million).

Note b: The foundation advised the ANAO in November 2020 that $100 million of the $200 million contributed funds target is associated with delivery partner contributions that were already built into the pre-RTP investment case being prepared for the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP or RTP component 4) and that discussions at the October 2018 International Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC) meeting confirmed the foundation’s logic and approach to the co-investment target. The remaining $100 million was based on the assumption that, for every dollar granted across the remaining RTP components, 30 cents in leveraged support would be generated from delivery partners. This was later expanded in May 2020 by the draft acquisition strategy (see paragraph 3.8), which included a specific breakdown of where the remaining $100 million is expected to be achieved by RTP funding component.

Source: ANAO analysis of foundation records, including the June 2020 six-monthly progress report.

Feasibility studies

3.6 The deliverables for each stream were introduced in individual phased five-year ‘stage plans’. While each plan comprised tailored activities, all streams were to commence with one-year planning phases. As part of the planning phases, campaign work plans were to be completed and feasibility studies undertaken for each stream. Each target was to be tested, then confirmed or adjusted, during the feasibility studies. Implementation was to commence in the second year, with this second phase having a two year timeframe in most cases.21

3.7 Consultants were engaged to conduct feasibility studies for the capital campaign and individual giving in May and July 2019, respectively. No changes were made to the respective targets as a result of those studies. The feasibility studies had identified that between $10 million and $15 million in fundraising administration costs would be required over the five year capital campaign period. This level of fundraising administration costs was not anticipated, with the resourcing profile set out in the co-financing strategy allocating less funding ($2.64 million over the five year capital campaign and $7.3 million in total across all four fundraising streams). The resourcing profile has not been updated following the feasibility study to reflect the larger budget the feasibility studies identified as being required.

3.8 Feasibility studies were not undertaken for the remaining two streams (corporate giving and contributed funds).22 A draft ‘Corporate and Contributed Funds Acquisition Strategy’ was developed internally in February 2020 to address the remaining two streams. It did not seek to test the feasibility of the targets previously set. Instead, it expanded on the detail provided within the co-financing strategy and set out the range of potential partnership opportunities and benefits available to current and potential corporate partners.

Timeframe over which leveraged funds are to be raised and spent

3.9 In a 12 October 2018 media release announcing the release of the Collaborative Investment Strategy, the foundation stated that it would:

create the nation’s biggest environmental fundraising campaign to grow a $443 million government contribution to the Reef by an additional $300 million to $400 million over the next six years.

3.10 Similarly, the strategy stated that:

The GBRF will amplify the impact of the investment by the Australian Government in the Reef through the continued application of a collaborative investment model, increasing RTP investment from $443.3 million by $300 million to $400 million over the next six years.

3.11 The foundation’s six monthly reporting to DAWE has identified that it budgets to spend $465 million over the six year life of the partnership. This comprises the $443 million Australian Government grant plus expected interest on the investment of the Australian Government grant. In this reporting, the foundation does not budget to spend the cash it has targeted to raise under the partnership (see Table 3.2). While the Australian Government grant funding is to be spent by 30 June 2024, in February 2021 the foundation advised the ANAO that it is not required to receive or spend the leveraged funds over the six year period of the partnership:

The foundation, as per the Collaborative Investment Strategy (CIS) and Head Agreement (Clause 8), seeks to leverage the Grant. The CIS aims to secure pledges up to the target by 30 June 2024 and outlines the key activities required to reach targets but there is no obligation to realise the entirety of the gift nor spend them by the end of the Agreement.

The nature of major gifts and corporate partnerships are such that these donors will commit over multiple years via pledge and contracts respectively over multiple years. The details and duration of each contribution is negotiated with the donors. Only at this stage in a donor gift agreement is the foundation in a position to forecast with certainty into a project budget.

The foundation will announce a gift’s full value even if it is pledged across multiple years. This is a common approach for charities raising money and has been the approach of the foundation with its flagship projects.

Table 3.2: Foundation reporting of partnership budget, expenditure and commitments as at 31 December 2020

|

|

Life-to-date RTP grant funding ($m) |

|||

|

|

Full budget |

Expenditure |

Future commitments |

Not yet committed |

|

|

A |

B |

E |

G G = A - B - E |

|

Component 1 — Administrative activities (grant funding) |

22,505,000 |

18,458,204 |

1,263,475 |

2,783,320 |

|

Component 1 — Administrative activities (interest on grant) |

21,795,000 |

– |

– |

– |

|

Component 2 — Water quality activities |

180,649,000 |

27,502,170 |

64,091,860 |

89,054,970 |

|

Component 3 — Crown-of-thorns starfish control activities |

52,000,000 |

15,395,895 |

14,940,318 |

21,663,787 |

|

Component 4 — Reef restoration and adaptation science activities |

90,000,000 |

1,831,394 |

1,192,403 |

86,976,203 |

|

Component 5 — Communities |

10,000,000 |

1,924,179 |

1,039,579 |

7,036,243 |

|

Component 5 — Traditional ownerᵃ |

52,149,000 |

1,854,351 |

287,836 |

50,006,813 |

|

Component 6 — Integrated monitoring and reporting activities |

36,000,000 |

1,864,204 |

3,146,241 |

30,989,555 |

|

Total of all components |

465,098,000 |

68,830,397 |

85,961,712 |

288,510,892 |

Note a: $10 million Future Fund that is not yet contracted is included in the $50 million ‘Not Yet Committed’.

Source: ANAO reproduction of an extract taken from Appendix 3 of the six-monthly report for July to December 2020 submitted by the foundation to DAWE, as required by the RTP head agreement.

Use of other contributions for administration costs of the foundation

3.12 The grant agreement with the Australian Government requires that cash and in-kind contributions that are raised be allocated by the foundation to the non-administration components, and that this allocation be identified in the six-monthly progress reports the foundation is required to provide to the department. Those obligations will end when the term of the partnership grant agreement ends on 30 June 2024.

3.13 Advice from the foundation to the ANAO in February 202123 set out that the framework established by the grant agreement entered into with DAWE allows funds received after 30 June 2024 to be spent on the foundation’s administration costs. In addition, the foundation advised the ANAO in February and April 2021 that:

The Agreement does not require the Foundation to have spent the cash raised through fundraising by the end of 2024. Furthermore, cash funding raised will have its own administration allocation in accordance with the Foundation’s standard business practices and those of the charity sector as a whole, as guided by the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission.

To ensure continuity in fundraising effort post 2024, the Foundation has embedded the four RTP fundraising streams into a 10-year campaign, Reef Recovery 2030, which seeks to raise $1 billion for the Reef by 2030. This fundraising campaign has been endorsed as a flagship action in the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science.

For clarity, monies raised by fundraising will be tied to RTP projects by way of gift, grant agreements and contracts for donors, trusts and foundations and corporate partners, respectively. These agreements bind the Foundation to direct these funds in accordance with the donor’s intentions.

Under the terms of the Head Agreement, during the RTP, the Foundation must direct monies raised by fundraising to Components 2-6, excluding Component 1 – Administration costs. Post 30 June 2024, the Foundation will revert to a standard charity operating model whereby income from funds raised and operations is applied to both administrative and direct project costs. As a sole cause charity, the Foundation will continue its mission of raising funds to support the long-term health of the Great Barrier Reef.

Government versus non-government sources of contributed funds

3.14 While the process by which the grant was awarded focused on the foundation’s ability to raise funds from non-government sources, the target of raising $200 million in contributed funds from research and delivery partners does not distinguish between non-government and government sources (including other Australian Government entities). In December 2020, DAWE advised the ANAO that:

The Department considers that the inclusion of in-kind and cash contributions from other Australian Government sources in the Foundation’s reports was not unintended in the development of the grant agreement.

The Department acknowledges that the Grant Agreement with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation refers to sources other than the Commonwealth, as you have quoted below.24 However, in the design of the grant agreement, the Department did not act to preclude other sources of Australian Government funding from being leveraged by the Foundation and included in their reporting.

Reef Recovery 2030

3.15 In May 2020, a ‘Capital Campaign overview’ was provided to the foundation board. It proposed to ‘present the capital campaign with an expanded scope, fundraising target and timeframe’. This involved embedding the four RTP fundraising streams into a new 10-year campaign called ‘Reef Recovery 2030’. The suggested timeframe for the new campaign was from 2020 to 2030, and would promote raising $1 billion for the reef over that period (funding sources specified in Table 3.3). The board endorsed this approach on 7 May 2020.

Table 3.3: Reef Recovery 2030 expansion on RTP funds and targets

|

Source of funds |

Original RTP amounts |

New 2030 target amounts |

|

Australian Government Grant |

$443.5 million |

$443.5 million |

|

Principal and Major Donors |

$100 million |

$200 million |

|

Corporates |

$50 million |

$100 million |

|

Individual Giving |

$7 million |

$17 million |

|

Impact Investments/Environmental Markets |

N/A |

$39.5 million |

|

Contributed Funds |

$200 million |

$200 million |

|

Total |

$800.5 million |

$1 billion |

Source: ANAO analysis of foundation records.

What quantum of in-kind contributions has been secured to date?

As at December 2020, 70 delivery partners had identified that they would make in-kind contributions totalling $53.1 million towards projects that, combined with others, were to receive Australian Government funding of $134.3 million (a contribution rate of 39 cents for each dollar granted). In total, 30 per cent of the promised in-kind contributions were not included in the grant agreements and contracts signed by the foundation meaning funding recipients were not obligated to deliver their promised contribution. In addition, for the small number of projects that have been completed and acquitted, it has been common for partner contributions to be less than promised, with 23 per cent of the expected in-kind contributions not reported as having been provided by the partner, with inconsistent follow-up action being taken by the foundation in respect to the shortfalls in contributions.

3.16 The foundation has a contractual obligation to seek cash and in-kind contributions for each RTP component.25

3.17 The foundation did not consistently seek to clearly preference in its selection processes those candidates that would make a co-contribution (either cash or in-kind) towards their own projects. This was particularly the case for the larger programs where the main funding recipients have been the natural resource management groups. More specifically in relation to the eight grant program guidelines examined by the ANAO (which covered 71 per cent of the 126 grants and 50 per cent of the $134.3 million grant funding contracted to 31 December 2020):

- the earliest three programs, with closing dates between December 2018 and March 2019 and total funding available of $20.9 million, had included an assessment criterion focussed on the extent of any co-contributions, with this criterion weighted at 10 per cent (in each case, there were a total of six criteria);

- the next program (with a closing date in March 2019 and $1.5 million in funding available) mentioned co-investment as an element of one of the five criteria (with this criterion weighted at 25 per cent);

- the next three programs (with closing dates between November 2019 and June 2020 and total funding available of $64.9 million) did not include co-investment as a separate criterion or element of any of the criteria; and

- one of the four criteria for the most recent program (with a closing date in July 2020 and $850,000 in total funding available) addressed co-investment (‘project demonstrates value for investment and integrates other funding or co-investment opportunities, including quantifiable in-kind and volunteer support’) with that criterion weighted at 20 per cent.

3.18 In February 2021, the foundation advised the ANAO26 that the ‘value for money’ criterion covered both co-contributions and the cost effectiveness of projects competing for funding. The ANAO’s analysis of the relevant program guidelines did not support this. For example, the guidelines for the $10 million Innovation and System Change Water Quality Program that closed to applications in February 2020 did not identify that co-contributions were to be considered as part of the value for money criterion. Rather, the criterion was described as: ‘Value for money, having regard to the total cost, the likelihood of the project being successful, and the potential benefit if the project is successful’.

3.19 While the ‘contributed funds’ can include cash, to date it has only been achieved through in-kind contributions. In-kind contributions are non-cash contributions expressed as a dollar value. These can include pro-bono services, labour contributions, facilities, equipment and services provided by project partners to the project.

3.20 By December 2020, the foundation had entered into 126 grant agreements and 38 consultancy contracts for the delivery of project components.27 As illustrated by Table 3.4:

- while the majority of partners had identified that they would make an in-kind contribution to the project (89 per cent of grant recipients and 14 per cent of consultants), the quantum of those contributions was considerably lower than the total amount of Australian Government funding being contributed (39 cents from partners for every Australian Government dollar). In addition, the contributions nominated by partners in their applications/submissions were rarely scrutinised by the foundation, for example:

- a December 2019 contract with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) providing $1.41 million of RTP funding for the Crown-of-Thorns-Starfish (COTS) Control Program included $12.4 million of in-kind contributions. This amount was adjusted down (to $211,350) following advice from DAWE in May 202028; and

- an October 2020 contract with the University of Technology Sydney for $496,945 for the ‘Coral Nurture Program’ included an in-kind contribution of $5,806,996. At least 93 per cent ($5,428,860) of this in-kind contribution related to third party staff and tourism vessel operating costs (across five separate tourism operators). Although the foundation had several discussions with the applicant, it did not seek any supporting documentation from the applicant or the third parties to test or confirm this value was accurate or achievable29;

- initially the foundation was not including the promised partner contributions in grant agreements or contracts, which meant that 30 per cent of partners who had identified they would be making a contribution were not required by the relevant agreement or contract to provide this contribution. The foundation’s updated practice since July 2020 is to now include a clause in the grant agreement template requiring funding recipients to provide the specified co-contributions in the schedule to the agreement or contract;

- twenty grants were due to be acquitted by the end of December 2020, and the foundation recorded that those partners were expected to contribute $7.2 million to the project in addition to the $10.8 million in grant funding they were to receive. Of those 20 grants, 18 have been acquitted with the acquittals accepted by the foundation including:

- three grants where the acquittal included no partner contribution, compared with the $239,600 the foundation recorded in its contract management system they should have contributed. In response to the audit findings, the foundation advised the ANAO in February 2021 that it would seek to follow-up as soon as possible with the grant recipients as to why they had not reported a contribution to the project in the final acquittals;

- ten grants where the acquittal included contributions (totalling $2.5 million) that were 46 per cent less than the $4.6 million the foundation recorded in its contract management system that should have been provided. The follow-up action undertaken by the foundation was inconsistent across the delivery partners in respect to the shortfall in partner contributions; and

- five grants where the acquittal included partner contributions (totalling $2.2 million) that were greater than that recorded by the foundation as expected ($1.3 million).

Table 3.4: Contributions from research and delivery partners as at December 2020

|

|

Grants |

Consultants |

||

|

|

Number of |

Value ($m) |

Number of |

Value ($m) |

|

Agreements/contracts entered into by foundation |

126 |

134.28 |

38 |

8.63 |

|

Contribution included by the partner in its application/proposal provided to foundation |

112 (89%) |

66.10a (49%) |

5 (14%) |

0.25 (3%) |

|

Contributions contracted by foundation |

68b (61%) |

46.49 (70%) |

2 (40%) |

0.21 (84%) |

|

Contributions recorded by foundation in its contract management systemc |

112 |

49.41 |

5 |

0.25 |

|

Contributions from Australian Government entitiesd |

10 (9%) |

7.28 (15%) |

2 (40%) |

0.23 (90%) |

|

Projects completed and acquitted (expected contributions recorded in the contract management system in August 2020) |

18 |

6.16 |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Contributions included in acquittals accepted by foundation |

15 (83%) |

4.76 (77%) |

Nil |

Nil |

Note a: This includes $12.4 million of in-kind contributions for the COTS Control Program that was later adjusted down to $211,350 (detailed at paragraph 3.20).

Note b: This consists of 47 contracts executed from August 2020 where a new standard clause was included at 3.1 (e) of the grant agreement template requiring funding recipients to provide the co-contributions specified at Item 6 of Schedule 1. The other 21 were executed prior to this and do not contain an equivalent clause. While the application forms (including nominated co-contributions) were appended to the back of the executed funding agreements, there is not a contractual requirement for these to be provided. Further, the foundation has amended the value of these co-contributions for six of these in its contract management system after the respective execution dates.

Note c: Amounts the foundation expects to be contributed by funding recipients and subcontractors are manually entered into the foundation’s contract management system (Integrum). During the course of the audit, the ANAO identified several entries where some of these figures: were not consistent with respective applications and contract documentation; could not be reconciled back to any formal documentation; or had been changed by the foundation after the initial entry and after the respective contract execution dates.

Note d: Specifically: Australian Institute of Marine Science; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation; and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

Source: ANAO analysis of foundation records.

Recommendation no.2

3.21 The Great Barrier Reef Foundation:

- include the extent to which funding candidates will provide a cash or in-kind contribution as a selection criterion for all project delivery grants and procurements; and

- follow up with partners where acquittals do not demonstrate that contracted contributions have been provided in full.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation response: Agreed.

What quantum of cash contributions has been secured to date?

The foundation has secured a total of $684,100 in cash contributions. This comprises $504,099 secured from individuals against the $7 million individual giving target over the life of the partnership. One commitment of $180,000 has been secured from a corporate donor, compared with a target from corporate donors of $50 million by 30 June 2024, and no commitments have yet been secured against the June 2024 $100 million target that is focused on philanthropists.

3.22 The largest cash component of the $357 million fundraising target (see Table 3.1) is the $100 million capital campaign that has a focus on philanthropy and individual giving tied to the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program. In November 2020, the foundation advised the ANAO that:

- ‘recruitment for key staff commenced in August 2018 with an eventual resource of nine staff with staff allocated across corporate partnerships, capital campaign, individual giving and a dedicated supporter services team’; and

- it had moved into the implementation phase for its fundraising activities in accordance with the following planned timeframes:

- donor acquisition and retention for the $7 million individual giving component had commenced in the September 2019 quarter;

- acquisition of contributions under the $50 million corporate giving component had also commenced in the September 2019 quarter; and

- the ‘quiet phase’ of $100 million capital campaign, during which the foundation expected to raise 60 per cent of the target, commenced in the March 2020 quarter.

3.23 As at 31 December 2020 the foundation had not secured a financial contribution to the capital campaign. In April 2021, the foundation advised the ANAO that:

The Foundation is following standard best practice capital campaign methodology and is advised by external campaign consultants. Capital campaigns typically commence with a quiet phase, in which research is conducted to identify if the campaign targets and ambitions will feasibly attract philanthropic support, and research into who those supporters might be. A case for support is developed and tested with prospective donors. During the quiet phase it is typical for campaigns to raise 60 per cent of their gifts before a public phase is announced.

The Foundation has developed a pool of prospective donors with the capacity to provide financial support with an existing interest in funding ocean science initiatives. Modelling supports that the campaign goals are achievable and the Foundation reports to the Board on progress to campaign targets in dashboard reporting and provides regular updates to the Department in its progress reporting.

As has been identified to Board and the Department, the impacts of travel restrictions and global uncertainty has delayed the Foundation’s ability to meet and connect with donors which will impact timeframes.

3.24 February 2021 reporting to the foundation board in terms of the capital campaign identified that there was $39.9 million30 in planning from ‘400 fully qualified and ranked prospects’. This reporting further identified:

- no contributions had been submitted;

- no contributions has been committed either verbally or in writing; and

- $30 million in potential commitments had been rejected by potential donors.

3.25 In addition to focussing heavily on United States of America (USA) prospects for its philanthropic donations, the foundation has also established mechanisms to encourage the receipt of US-based donations through individual giving mechanisms. As of October 2020, the foundation’s US charitable entity, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation USA Inc. (GBRF USA) had received US$69,440 into its bank account from USA citizens and small businesses. The foundation advised the ANAO in February 2021 that:

GBRF USA is structured in accordance with US requirements to be approved by the IRS as a tax-exempt charitable organisation. As such GBRF Australia will periodically apply for a grant of funds from GBRF USA Board of Directors. Once this application is approved these donations are transferred to GBRF Australia and will be recorded as gifts and counted towards RTP targets. In agreement with the GBRF USA Board, an application for funding will be submitted in early 2021 and then quarterly thereafter.

3.26 The corporate giving target is $50 million. While October 2020 reporting to the foundation board against the corporate giving target identified that there was $10.95 million in planning and $31 million in submitted proposals (by the foundation to potential donors), as of February 2021 the only commitment that had been secured was $180,00031 from an existing corporate donor to support research into chemical strategies to improve settlement and survival (part of the Enhanced Treatment and Aquaculture subprograms). In February 2021, the foundation advised the ANAO that:

Business profitability is a precondition to corporate support of charities but factors such as businesses indicating they wish to: improve employee engagement, strengthen social licence to operate and achieve social impacts are a better indicator of propensity to support, alongside an assessment of capacity to support.

Additionally, evidence from past economic downturns indicates that corporate investment in non-profits contracts sharply but recovers in line with market recovery. This is evidenced in the partnership negotiations that the foundation was engaged in that were paused at the height of the health crisis in Australia that have restarted as stock market and business confidence recovered towards the latter half of 2020. This has been reported in RTP progress report and to Board.

3.27 Through its individual giving stream, the foundation has recorded receiving a total of $504,099 in cash contributions. It consists of cash donations from individual citizens from 1 July 2018 through mechanisms including workplace and regular giving; one-off donations and third party website donations. The ANAO’s analysis was that the foundation’s six monthly report for the period ending 30 June 2020 overstated the amount raised (the foundation reported, on page 85, that it had raised $1.098 million). The foundation advised the ANAO in February 2021 that:

- this was reported because it represented the total of co-contributions identified as cash by two funding recipients in their final acquittals; and

- one of these (with a value of $897,971) should have been recorded as in-kind, whereas the other (with a value of $200,000) was correctly identified as cash.

3.28 The latter cash contribution was identified by the funding recipient (Greening Australia) in its application by way of letter of support from the Queensland Department of Environment and Science.32 This contribution was not provided to the foundation, nor was it identified as cash in the foundation’s contract management system. Rather, all co-contributions, including this $200,000, have been recorded and reported as in-kind.

Is appropriate progress being made towards achievement of the targets?

As interim fundraising targets have not been set, it is difficult to assess whether appropriate progress is being made towards the fundraising targets. By 31 December 2020, $5.5 million has been reported as raised through cash contributions and acquitted in-kind contributions from research and delivery partners against the overall target of $357 million. In addition to the acquitted in-kind contributions, a further $46.5 million of in-kind contributions has been contracted to be received.

3.29 One of the risks listed in the foundation’s RTP risk management plan was the risk that it might not meet its fundraising targets. Among the mitigating controls identified (to address the consequence if the risk occurred) was to review and update the co-financing strategy.

3.30 By 31 December 2020, more than 40 per cent through the grant period, $5.5 million (1.5 per cent of the target) has been reported as raised through cash contributions and acquitted in-kind contributions from research and delivery partners against the overall target of $357 million. Between December 2019 and October 2020, the foundation board received updates on the delays experienced to date in implementing parts of the co-financing strategy, with specific attention drawn to:

- fundraising efforts being impacted in 2019, including an unquantified delay to corporate partnerships and a six month delay to the implementation of the capital campaign, due to funding uncertainty associated with the federal election and negative media commentary relating to the grant process; and

- the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, including anticipated delays to the capital campaign of 18 to 24 months.33