Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of the Biosecurity Legislative Framework

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources' implementation of the new biosecurity legislative framework.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australia is one of the few countries in the world to remain free from some of the world’s most damaging pests and diseases.1 This status means that Australia and its agriculture industries have a comparative advantage in export markets around the world. The increasing volumes of international travellers and trade from a growing number of countries have the potential to impact on Australia’s ability to protect its economy, environment and human health from exotic pests and diseases.

2. In June 2016, the Australian Government introduced a new biosecurity legislative framework—comprising the Biosecurity Act 2015 (the Act)2, four related Acts and delegated legislation (including regulations, declarations and determinations)—to manage the risk of pests and diseases entering Australian territory and causing harm to animal, plant and human health, the environment and the economy. The new framework, which replaced the arrangements established under the century-old Quarantine Act 1908, is being implemented in three stages over five years, with Stage 1 relating to the period leading up to commencement of the framework on 16 June 2016.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ implementation of the new biosecurity legislative framework.

4. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Was a robust governance and project management framework in place to support implementation of the new framework?

- Was the development of delegated legislation, administrative practice and business processes, effective and timely?

- Did the engagement with internal and external stakeholders support the transition to the new framework?

Conclusion

5. The arrangements established by the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources effectively supported the implementation of the new biosecurity legislative framework in accordance with legislated timeframes.

6. A sound planning approach, governance structure and assurance review program was established by the department to support the implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework. Nevertheless, issues relating to the delayed establishment of the Board and weaknesses in performance reporting adversely impacted on oversight and monitoring arrangements. While the framework commenced operating on 16 June 2016 as required by legislation, more effective oversight and monitoring would have better positioned the department to deliver framework elements as originally planned. Further, there is scope for the department to review its approach to assessing the benefits to be derived from the new legislative framework.

7. The arrangements established by the department to support the operation of the new biosecurity legislative framework from 16 June 2016, including the development of policy and delegated legislation, creation of instructional material and the delivery of training for staff, implementation of IT system modifications and engagement with stakeholders, were, in the main, effective. There were, however, delays encountered in finalising a number of key activities, which ultimately reduced the time available to deliver important elements of the program, such as aspects of stakeholder engagement and IT system modifications. These delays also led to the reprioritisation of some implementation activities, including instructional material and IT changes, with delivery to occur in latter stages.

Supporting findings

Program planning and oversight

8. The approach adopted by the department to plan the implementation of the new framework was appropriate, with extensive planning documentation developed that outlined timeframes and roadmaps, roles and responsibilities, risk management approaches, assurance arrangements, and monitoring and reporting requirements. A robust governance structure was also designed, which provided a sound framework in which to coordinate the divisional level projects and integrate the delivery of enabling functions, such as stakeholder engagement and IT changes.

9. Notwithstanding the establishment of an appropriate planning approach and governance structure, issues relating to the delayed establishment of the Board and weaknesses in performance reporting adversely impacted on oversight and monitoring arrangements. Ultimately, weaknesses in oversight and monitoring arrangements put at risk the department’s ability to implement the new legislative framework in accordance with fixed timelines. More effective oversight and monitoring arrangements could have better mitigated this risk.

10. The series of assurance reviews that was conducted in the latter period of Stage 1 program implementation played a key role in highlighting to senior management the emerging risks to successful implementation of the new legislative framework. The department’s responsiveness to the reviews and the actions subsequently taken to prioritise implementation activities enabled the department to meet the set deadline of 16 June 2016 for the commencement of the new framework. Earlier commencement of these reviews—the first review was not undertaken until December 2015—would have provided more timely assurance and allowed more time for corrective actions to be taken.

11. The department adopted a sound approach to post implementation monitoring and evaluation for the implementation program, including an external post implementation review and a range of mechanisms designed to provide assurance in relation to Stage 1 implementation’s achievements and remaining activities to be prioritised for Stage 2. In addition, the department endorsed a Benefits Realisation Framework in December 2016, which is still to be finalised. In finalising the Framework, the department should ensure that the measures inform an assessment of those benefits that are directly attributable to the new legislative framework and of the expected cost savings (estimated by the department to be $6.9 million each year averaged over 10 years).

12. The department has appropriately captured the lessons learned from the program of work undertaken to implement the new biosecurity legislative framework. The successful implementation of latter stages of the biosecurity legislative framework will be heavily dependent on the department applying the lessons that it has learned from the initial stage of program implementation.

Program delivery

13. The department finalised the required delegated legislation in order to meet the timeframe for the commencement of the new framework. Delays encountered in the development process reduced the time available to undertake subsequent implementation activities, such as the development of instructional material and the delivery of training, and stakeholder consultation.

14. The arrangements established by the department to amend and develop instructional material and to deliver training to assist staff to fulfil their requirements under the new legislation were appropriate.

15. The department effectively engaged with stakeholders, including relevant government entities and key industry bodies. The majority of stakeholders indicated that they were, overall, satisfied with the level and quality of the department’s engagement in relation to the introduction of the new framework.

16. The relevant departmental IT systems affected by the new framework were modified to accommodate new requirements by 16 June 2016, but the timeframe available to undertake the modifications was condensed due to delays in finalising policy positions. As a consequence, the scope of some planned changes was reduced and there were deficiencies identified in the documentation of scope changes and testing.

Recommendations

Recommendation No. 1

Paragraph 2.29

The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should:

- finalise and implement the Benefits Realisation Framework as a priority; and

- ensure that the Benefits Realisation Framework is effective in assessing the impact of the introduction of the new biosecurity legislative framework and the value of the reduction in costs and regulatory burden for external stakeholders.

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

17. The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ summary response to the report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

Implementation of the Biosecurity Legislative Framework was successful. The Biosecurity Act 2015 (the Biosecurity Act) took effect on 16 June 2016 with trade unimpeded, biosecurity risk mitigated and our clients and staff well-positioned to understand and comply with the new legislation.

The department agrees with the ANAO’s assessment that it effectively engaged with stakeholders. The department undertook extensive engagement with stakeholders, other government agencies, clients and staff in the lead up to 16 June 2016 to ensure readiness to operate under the new framework. The department also agrees with the ANAO’s finding that staff were appropriately supported and trained to operate under the new framework.

The department acknowledges there were challenges in the early stages of implementation which hindered the establishment of a formal programme structure prior to the initiation of projects. It also impacted the early establishment of robust programme level reporting to support effective monitoring and oversight. However, the Programme Assurance Activities completed during the course of the implementation were successful in identifying the risks. This allowed mitigation activities to be put in place that effectively managed the risks and supported the department’s successful implementation of the Biosecurity Legislative Framework. The department is continuing this robust programme and governance approach in the ongoing implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework as well as other departmental programmes of work.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australia is one of the few countries in the world to remain free from some of the world’s most damaging pests and diseases.3 This status means that Australia and its agricultural industries have a comparative advantage in export markets around the world. The increasing volumes of international travellers and trade from a growing number of countries have the potential to impact on Australia’s ability to protect its economy, environment and human health from exotic pests and diseases.

1.2 Until June 2016, the Quarantine Act 1908 (Quarantine Act) was the key piece of legislation to manage biosecurity4 in Australia. Since the introduction of the Quarantine Act over a century ago, it has been amended more than 50 times to cater for changing demands on the biosecurity system. These amendments resulted in complex legislation that contained overlapping provisions and powers.

1.3 To address issues relating to the complexity of biosecurity legislation, the Australian Government has commissioned a number of reviews over time aimed at reforming the biosecurity system, including a comprehensive review of Australia’s quarantine and biosecurity arrangements in 2008 (the Beale Review).5 The Beale Review recommended significant reforms to strengthen the biosecurity system, including the development of new biosecurity legislation.

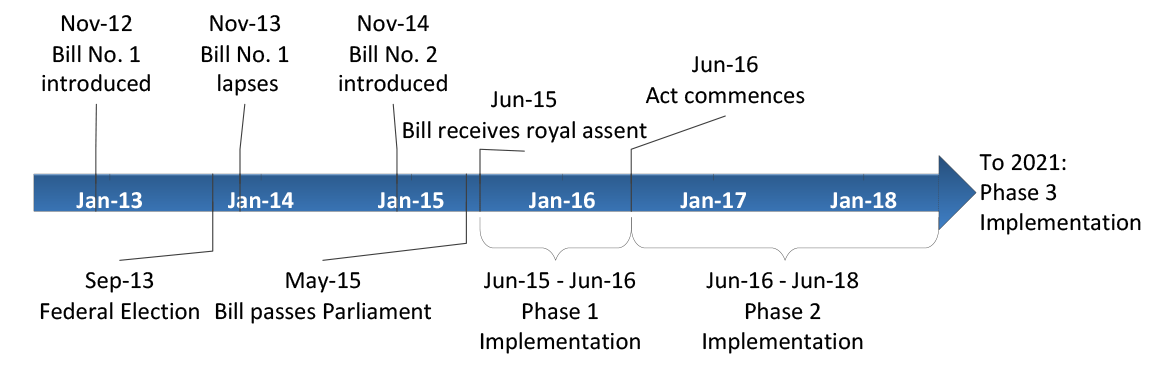

1.4 In response to the wide-ranging recommendations arising from the Beale review, the Australian Government introduced the Biosecurity Bill into the Parliament in 2012. The 2012 Bill lapsed as a result of the 2013 federal election when the Parliament was prorogued. A second revised Biosecurity Bill was later introduced in 2014, which was passed by the Parliament in May 2015 and received royal assent on 16 June 2015. The Act commenced 12 months after the date of royal assent, on 16 June 2016.

New legislative framework

1.5 The Biosecurity Act 2015 (the Act) establishes the regulatory framework for the management of the risk of pests and diseases entering Australian territory and causing harm to animal, plant and human health, the environment and the economy. The Act was designed to better support Australia’s agricultural productivity and marine industries, while also helping to protect Australia’s environment and human, animal and plant health. While the Act does not substantially change the operational functions under the previous Quarantine Act, it establishes a move towards a principle-based approach to regulation and supports the department’s risk-based approach to biosecurity intervention. It also includes substantive change relating to compliance and enforcement powers (see Box 1).

|

Box 1: Key principles underpinning the Act |

|

The Act establishes new requirements and regulatory powers to manage biosecurity risks associated with goods, people and conveyancesa entering Australian territory. It is underpinned by the following six key principles:

|

Note a: Conveyances are aircraft, vessels, vehicles, trains and any other means of transport.

Source: ANAO based on Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Biosecurity Bill 2014–Explanatory Memorandum, pp. 8–11.

1.6 The Act operates in conjunction with three Biosecurity Charging Imposition Acts.6 In addition, where significant changes are anticipated under the Act, the Biosecurity (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Act 2015 includes provisions to facilitate the transition to new requirements. In particular, it allows for all existing notices, directions, permits and permissions issued under the Quarantine Act to remain in force after 16 June 2016. It also provides for additional periods to ensure that stakeholders and clients comply with new requirements. For example, most sea ports and airports that were declared as ‘first port’ under the Quarantine Act have three years from commencement to ensure that they comply with the new requirements for first points of entry under the Act.

1.7 The Act, the four related Acts and the delegated legislation7 constitute the biosecurity legislative framework. The framework is administered jointly by the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources and the Department of Health.8

Arrangements for the introduction of the new legislative framework

1.8 In recognition of the extent of the changes arising from the introduction of the new framework9, the Act included the provision for the delayed implementation of framework requirements (12 months after the Act received royal assent on 16 June 2015). This provision was included in the Act to allow the department time to communicate the new requirements to stakeholders, industry participants and the general public. It was also included to allow the department to provide relevant information and training to departmental staff and for consultation to occur with industry and state and territory governments regarding shared responsibilities and obligations.

1.9 The biosecurity legislative framework provides flexibility for the department to adopt the most appropriate systems to manage biosecurity risks. As indicated previously, some of the changes and new powers included must be implemented from the date of commencement on 16 June 2016, while others can be implemented over time as business capacity allows. Some powers also have additional delayed commencement arrangements prescribed under the Act.

1.10 Accordingly, the department has adopted a staged approach to the implementation process over five years:

- Stage 1—related to the period leading up to commencement of the legislative framework on 16 June 2016. The focus of this stage was on the development and implementation of priority changes to administrative practices to enable core biosecurity operations to continue without regulatory failure, and to support staff, clients and stakeholders to comply upon commencement of the new legislation;

- Stage 2—relates to the period from 17 June 2016 to 30 June 2018. The focus of this stage is on the continued rollout of delayed, transitional or phased implementation provisions of the Act. It will also deliver activities determined by the department as not critical for core biosecurity operations under the Act as at 16 June 2016; and

- Stage 3—commencing in July 2018, the focus of this stage is to be determined by the department prior to the completion of Stage 2.

1.11 An overview of the timeline for the development and implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework is provided in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Biosecurity legislative framework development and implementation timeline

Source: ANAO based on departmental information.

1.12 The costs associated with the implementation of the new biosecurity legislative framework are to be sourced from the department’s existing budget. A program brief endorsed by the department in October 2014 estimated these costs at $10.8 million over four years (2014–15 to 2017–18).

Audit approach

Objective, criteria and methodology

1.13 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ implementation of the new biosecurity legislative framework.

1.14 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Was a robust governance and project management framework in place to support implementation of the new framework?

- Was the development of delegated legislation, administrative practice and business processes, effective and timely?

- Did the engagement with internal and external stakeholders support the transition to the new framework?

1.15 The ANAO examined documentation held by the department, interviewed relevant staff, and visited a selection of premises where biosecurity activities are conducted. The ANAO also conducted two separate consultation processes in August-September 2016. Forty-eight industry bodies were invited to contribute their views on the effectiveness of the department’s implementation of the new framework, with 10 either providing a written submission or participating in a telephone interview. Three additional industry submissions were also received through the ANAO website’s public contribution facility. The ANAO also invited representatives from relevant Commonwealth, state and territory government entities to provide comments. All, but one, participated in a telephone interview.

Scope

1.16 The scope of the audit included an examination of the activities conducted by the department to prepare for the commencement of the legislation on 16 June 2016. The audit also considered the impact of the department’s implementation strategies on external stakeholders (industry and Commonwealth, state and territory government entities) and departmental staff. The preparedness of the key IT systems impacted by the legislative changes was also examined.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $267 000.

2. Program planning and oversight

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the governance and project management arrangements established by the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (the department) to support the implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework, including planning processes and oversight, monitoring and assurance arrangements. The ANAO also examined the arrangements established by the department to determine whether program objectives were achieved and whether the lessons learned were captured to inform the delivery of latter stages of program implementation.

Conclusion

A sound planning approach, governance structure and assurance review program was established by the department to support the implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework. Nevertheless, issues relating to the delayed establishment of the Board and weaknesses in performance reporting adversely impacted on oversight and monitoring arrangements. While the framework commenced operating on 16 June 2016 as required by legislation, more effective oversight and monitoring would have better positioned the department to deliver framework elements as originally planned. Further, there is scope for the department to review its approach to assessing the benefits to be derived from the new legislative framework.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at better positioning the department to determine the impact of the introduction of the new biosecurity legislative framework. The department should also continue to embed enhanced oversight and management arrangements adopted for the latter part of Stage 1 implementation.

Were planning processes appropriate?

The approach adopted by the department to plan the implementation of the new framework was appropriate, with extensive planning documentation developed that outlined timeframes and roadmaps, roles and responsibilities, risk management approaches, assurance arrangements, and monitoring and reporting requirements. A robust governance structure was also designed, which provided a sound framework in which to coordinate the divisional level projects and integrate the delivery of enabling functions, such as stakeholder engagement and IT changes.

2.1 In anticipation of the passage of the 2012 Bill, the department commenced planning activities for the implementation of the proposed legislative framework for biosecurity. These activities were ceased when the 2012 Bill lapsed as a result of the 2013 federal election. When the Biosecurity Bill was re-introduced into the Parliament in November 2014, the department identified the need for a sound implementation approach given the anticipated scale of the proposed legislative changes. To underpin such an approach, the department developed:

- a change assessment, which was completed in May 2014. A change assessment is used by the department to assist in determining the level of controls required to manage change activities. The 2014 change assessment received the highest rating (‘high’) and identified that the program would have a significant impact on all aspects of the department’s business;

- a business case to help ensure that the department was sufficiently prepared for the implementation of the new legislative framework. The business case: set out the scope and expected business benefits of the implementation program; outlined the risks, costs and resources for four alternative implementation options; and presented the arguments in support of the recommended option. The recommended option, which received senior management endorsement in May 2014, required approval of a program brief by October 2014 and an implementation plan by November 2014;

- a program brief, which was approved by the Deputy Secretary in October 2014. This brief further developed the option recommended in the business case, based on the assumption that the legislation would receive royal assent in March 2015. It outlined the overall approach to implementation, based on the identification of a suite of projects on subject matter areas of the legislation (for instance, ballast water and sediment; conditions and permits for goods). The projects were prioritised, depending on the level of change that the new legislation would impose. The brief also specified the governance structure, the program risks, revised budget and high level schedule;

- a Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Framework, which was endorsed by senior management in July 2015 (discussed in the next paragraph); and

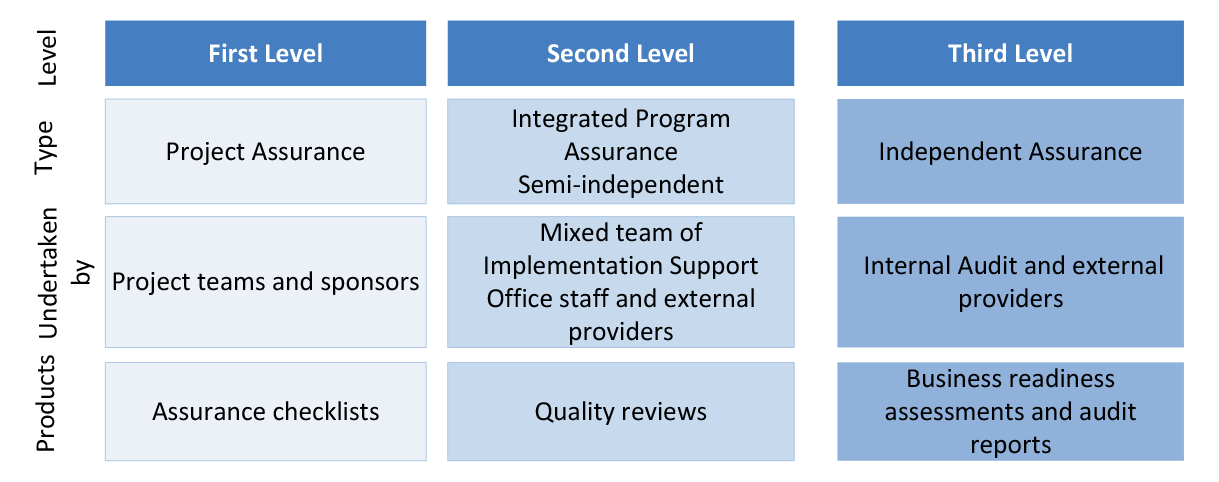

- a program assurance framework for the first stage of implementation (discussed later from paragraph 2.10) in October 2015 to provide assurance that risks were being appropriately mitigated and that relevant legislative requirements for commencement would be implemented. The framework detailed three levels of assurance, at project and program levels, combining reviews and audits.

2.2 The structures established to provide governance over the implementation program (see Figure 2.1), which were described in the implementation framework, comprised:

- a Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Board (the Board) established as the primary governance body responsible for overseeing the implementation program. The Board, which was chaired by the Deputy Secretary responsible for biosecurity10, reported to the department’s Executive Management Committee.11 Other members of the Board included: the First Assistant Secretaries of the five divisions involved in program implementation; the Chief Information Officer; the Chief Financial Officer; and the General Counsel;

- an Implementation Office, which was led by an Assistant Secretary and was responsible for reporting on program-level implementation progress to the Board. The Implementation Office was responsible for managing the day-to-day aspects of program implementation, including monitoring the program schedule, managing program risk and assurance arrangements and integrating the program’s diverse functions; and

- Project Sponsors (at the First Assistant Secretary level) and Project Managers for each of the 23 projects to be delivered across five divisions.

Figure 2.1: Implementation program governance structure

Source: ANAO based on departmental information.

2.3 The Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Framework also included provision for the establishment of a reporting and tolerance threshold framework, which was intended to identify—in a timely manner—risks to project and program schedules, scope and resources (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Reporting framework

Source: ANAO based on departmental information.

Were effective oversight and monitoring arrangements implemented?

Notwithstanding the establishment of an appropriate planning approach and governance structure, issues relating to the delayed establishment of the Board and weaknesses in performance reporting adversely impacted on oversight and monitoring arrangements. Ultimately, weaknesses in oversight and monitoring arrangements put at risk the department’s ability to implement the new legislative framework in accordance with fixed timelines. More effective oversight and monitoring arrangements could have better mitigated this risk.

2.4 The department initially planned to finalise an implementation plan for the biosecurity legislative framework by December 2014. An initial plan was prepared in May 2015, but did not receive senior management endorsement. A subsequent Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Framework was not finalised until July 2015—which was after several of the 23 projects had commenced. Further, the establishment of the Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Board was not completed until July 2015 (the Board’s revised Terms of Reference were not endorsed until July 2015 and no meeting minutes were taken between February and May 2015).

2.5 In addition to delayed implementation of elements of the planning framework, there were also issues affecting the timeliness and quality of performance reporting. In framing its performance reporting requirements, the Board requested that reports only include deliverable and milestone information where the overall project status was at risk. Further, the Board required that a single program overview report be provided to the Board and the Executive Management Committee, with the timing of the report to align with the Executive Management Committee meeting schedule.

2.6 These decisions contributed to the Board receiving information in the Program Status Reports (which consolidated the information provided in each individual Project Monthly Status Report) that was often delayed and was generally out-of-date. For example, the first Program Status Report that was presented to the Board was provided on 18 September 2015 and reported on the period July–August 2015. On 9 December 2015, the Board was provided with a Program Status Report that covered the period from October–November 2015, but did not receive further updated information until February 2016.

2.7 The effectiveness of performance reporting was also questionable. While the Program Status Reports documented delays and concerns in relation to meeting timeframes as early as October 2015, the overall risk rating of the program was maintained at ‘green’ and ‘on track’ until the March 2016 Board meeting—three months before the commencement of the new legislative framework. Further, the status reports submitted to the department’s Executive Management Committee after reviews had been conducted under the program assurance framework (discussed later in this chapter) did not sufficiently highlight the extent of emerging risks to meeting the deadline for implementation of the new framework.

2.8 The quality of program reporting was also questioned in two internal audits undertaken to review the processes and practices relating to the implementation of the new legislative framework (the resulting reports were finalised in March and May 2016). These audits found that a lack of information from some divisions limited the Implementation Office’s ability to effectively monitor progress and report on program and project level activities. They also found that the Board had insufficient visibility and scrutiny over the operations of individual projects, which ultimately impacted on its capacity to ensure that the projects were fit-for-purpose in underpinning the achievement of higher level program objectives.

2.9 Further, some projects were found to have been implemented in isolation, with dependencies (between projects or between business areas and projects) not fully appreciated across the program of work being undertaken. In particular, delays in the development of policy positions and delegated legislation had a significant impact on the identification of training needs, the development of instructional material12, the implementation of a program of communication and engagement, and the updating of IT systems (discussed further in Chapter 3).

Was a sound assurance framework established for program implementation?

The series of assurance reviews that was conducted in the latter period of Stage 1 program implementation played a key role in highlighting to senior management the emerging risks to successful implementation of the new legislative framework. The department’s responsiveness to the reviews and the actions subsequently taken to prioritise implementation activities enabled the department to meet the set deadline of 16 June 2016 for the commencement of the new framework. Earlier commencement of these reviews—the first review was not undertaken until December 2015—would have provided more timely assurance and allowed more time for corrective actions to be taken.

2.10 The Program Assurance Framework that was developed for the program of work to implement the new legislative framework is provided at Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Assurance framework

Source: ANAO based on departmental information.

2.11 Over the course of Stage 1 program implementation, the department conducted six assurance activities between December 2015 and June 2016 (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Assurance reviews, December 2015 to June 2016

|

Short title |

Objective |

Date |

|

Quality Review 1 |

To verify that there were no significant gaps in the program of work underway to implement the requirements of the Act. |

December 2015 |

|

Quality Review 2 |

To assess whether program products that provide staff and clients with the tools and knowledge to operate under the Act were in place or would be delivered according to the agreed delivery schedules, and were in line with the department’s compliance posture and legislative requirements for commencement. |

March 2016 |

|

Internal Audit Interim Status Paper |

To assess whether the department had established appropriate project management and monitoring arrangements to support the successful implementation of the biosecurity legislation—Initial Assessment. |

March 2016 |

|

Business Readiness Assessment |

To identify whether the department was ready for commencement: it was compliant with legislation; staff had the right capabilities; implementation risks were mitigated; and clients and stakeholders had received appropriate support. |

March 2016 |

|

Internal Audit Final Report |

To assess whether the department had established appropriate project management and monitoring arrangements to support the successful implementation of the biosecurity legislation—Key Learnings. |

May 2016 |

|

Quality Review 3 |

To identify whether: staff and clients understood the impact of the new legislation and their roles and responsibilities; and there were any gaps in staff and client awareness. |

3 June 2016 |

Source: ANAO from departmental information.

2.12 The first review, which was conducted in December 2015, was undertaken to verify that there were no significant gaps in the program of work underway to implement the new legislative framework. The review identified that insufficient information was available to enable the comprehensive tracking of the implementation of legislation clauses at the project level. The review, using selective walkthroughs and testing, identified a risk that gaps between projects could affect the implementation of some legislative clauses. The review report included six recommendations for improvement.

2.13 In response to the review’s recommendations, the department modified a legislation implementation risk matrix that had previously been developed to support implementation. The modifications included identifying, for each subclause of the Act: a primary owner; whether the subclause needed to be implemented on or after 16 June 2016; and a risk rating for not implementing the subclause. The matrix was maintained throughout the implementation process, and assisted the department to mitigate the risk of non-compliance because of a failure to implement relevant legislative clauses. As at 3 June 2016, the Implementation Office reported to the Board that there were no subclauses that had a residual risk rating of high or extreme.

2.14 The Quality Review 2, the Internal Audit Interim Status Paper and the Business Readiness Assessment were completed in March 2016. These assurance activities clearly indicated that there was a significant risk that the department would not be ready for the commencement of the new legislative framework on 16 June 2016. In particular, the reports resulting from these activities variously stated that:

[There is no evidence that] staff and clients will have the full suite of tools and knowledge to operate under the Biosecurity Act at commencement. … No assurance can be provided that program products reflect the [department’s] compliance posture, agreed policy positions and legislative requirements. … We have identified a number of gaps [in the program of work].13

There is a heightened risk that implementation of required activities will not be completed to the required standard by 16 June 2016.14

[The department is] not ready for implementation. There is a high risk or certainty of multiple aspects of readiness not yet addressed.15

2.15 These assurance activities also provided an overview of the issues that had been encountered by the department during the implementation process for the new legislative framework, with this information instrumental in prompting the department to undertake urgent remedial action to address the identified imminent risk of failure of the program. In response to the issues raised, the department:

- undertook a risk-based analysis of activities that were required to be completed before commencement (‘must-haves’) and activities that could be postponed and included in Stage 2 of the implementation process (17 June 2016 to 30 June 2018);

- conducted a ‘re-baselining’ of the commencement roadmap and critical path to ensure that all projects and business area deliverables were aligned against the same schedule;

- reviewed the format and content of the program status report; and

- established a working group with representation at the Assistant Secretary level from the key areas of the department involved in the implementation (the ‘AS Working Group’). This group met daily and then three-times a week from March 2016 until the commencement of the legislation.

2.16 The internal audit work undertaken in May 2016, which followed up on the previous internal audit work conducted in March 2016, was designed to identify the key learnings for current and future programs across the department. It confirmed that the range of issues experienced during Stage 1 implementation had put the program at ‘serious risk of not achieving implementation targets’. However, the report concluded that, as a result of the corrective actions undertaken from March 2016, the department was well positioned to ‘deliver core capabilities to enable primary biosecurity operations to continue upon legislative commencement’.

2.17 The Quality Review 3, which was completed on 3 June 2016, incorporated surveys and interviews to determine whether staff and stakeholders were aware of their roles and responsibilities and whether they were ready for the commencement of the legislation. The review concluded that there were no significant gaps in understanding and awareness of the legislative requirements, but made three recommendations designed to improve understanding among staff and stakeholders regarding their roles, responsibilities and obligations prior to commencement. The review also recommended a follow-up staff survey three weeks after the commencement of the new legislative framework, and a formal review of lessons learned from the implementation project (discussed at paragraph 2.20). A status update was provided to the Board on 16 June 2016 confirming that all recommendations had been addressed.

2.18 Notwithstanding the appropriateness of the framework established to provide assurance regarding implementation progress, there was scope for the department to have given further consideration to the timing of assurance activities. Given that Stage 1 implementation had a clearly defined and limited timeframe (12 months from the endorsement of the framework by the Board in July 2015 to the commencement of the legislation on 16 June 2016), there would have been benefit in the department conducting an earlier progress review, focused on verifying the conformity of project deliverables with the implementation schedule.

Did the department establish a sound approach to post implementation monitoring and evaluation?

The department adopted a sound approach to post implementation monitoring and evaluation for the implementation program, including an external post implementation review and a range of mechanisms designed to provide assurance in relation to Stage 1 implementation’s achievements and remaining activities to be prioritised for Stage 2. In addition, the department endorsed a Benefits Realisation Framework in December 2016, which is still to be finalised. In finalising the Framework, the department should ensure that the measures inform an assessment of those benefits that are directly attributable to the new legislative framework and of the expected cost savings (estimated by the department to be $6.9 million each year averaged over 10 years).

Post-implementation review

2.19 At the program level, the assurance framework included the provision for a post implementation review, which was completed in August 2016 by an external provider. While recognising that the implementation process had faced significant challenges, the review concluded:

The commencement deadline of 16 June 2016 was met, with trade unimpeded, biosecurity risk mitigated and the department positioned to execute lawful decisions in accordance with the new legislation.16

2.20 The review adopted a forward-looking focus and made ten recommendations to guide Stage 2 and Stage 3 of implementation. The recommendations outlined the importance of robust and early planning, the collaborative development of a program blueprint and adherence to the planned schedule and implementation processes.

Project and program levels assurance activities

2.21 At project and program levels, assurance mechanisms included:

- a register to capture those activities that were not completed at Stage 1 and that were required to be prioritised for the next stage of the implementation;

- a survey of biosecurity staff to assess their level of understanding of the legislation and of their responsibilities. The survey was undertaken from August–September 2016. The results from this survey were compared with a similar survey conducted in early June 2016 as part of Quality Review 3 (the results of the surveys are discussed further in Chapter 3);

- a risk matrix, discussed earlier at paragraph 2.13, which was used to determine legislative conformity;

- project closure reports at the divisional level and for the program. These closure reports identify the lessons learned from Stage 1 implementation, remedial activities for Stage 2, outstanding risks and opportunities for improvement; and

- a series of mechanisms, including issues registers, verification plans and evaluations, that aim to: identify issues encountered by service delivery staff post 16 June 2016; determine service delivery gaps and areas for further improvement; monitor biosecurity staff’s use of the new enforcement powers; evaluate the impact of the communication activities; and assess the quality of new and updated instructional material.

Benefits realisation

2.22 The department expects that the introduction of the new legislative framework will generate a range of benefits to the department, as well as industry, individuals and the wider agricultural community, including:

- reduced compliance costs, administrative burden and greater regulatory certainty for businesses and individuals;

- greater flexibility and certainty in administering biosecurity regulation for the department; and

- reduced impact of biosecurity incursions and improved safeguards for plant and animal health status.

2.23 The reduction in the costs and regulatory burden for external stakeholders and government is estimated by the department at $6.9 million a year averaged over ten years.17

2.24 To assess whether the department is well placed to realise the expected benefits, the department is developing a Benefits Realisation Framework. The draft Framework was initially presented to the Board for its endorsement in February 2016, with the revised version of the Framework endorsed at its December 2016 meeting, six months after the commencement of the legislation. The endorsed version was incomplete with baseline data and some other elements still to be finalised. The delayed finalisation and deployment of the Framework has the potential to diminish its usefulness, particularly where baseline data has not been collected to measure the impact of legislative changes from commencement. The deployment of the Benefits Realisation Framework should be a key focus for the department to provide an appropriate basis on which anticipated benefits from the new biosecurity legislative framework can be monitored and reported to departmental management and to relevant stakeholders.

2.25 The ANAO reviewed the 12 qualitative and quantitative measures included in the final version of the Framework and examined the underpinning rationale and assumptions developed by the department (see Box 2).

|

Box 2: Benefit Realisation Framework measures (as at December 2016) |

|

Ability to deal with biosecurity risks using appropriate tools

Staff confidence to apply the legislation

Interpretation issues and associated legal costs

Confidence from stakeholders and clients about decisions that affect them

Time and effort to deal with non-compliance

Regulatory overheads from participation in the biosecurity system

|

Note a: The Act enables the Director of Biosecurity (Secretary of the department) to require people seeking to import goods under permit, or entities wishing to enter an approved arrangement, to answer questions relating to their (and their associates’) fitness and propriety. This is subject to verification by the department.

Note b: ‘Approved arrangements’ are voluntary arrangements between industry stakeholders (operators) and the department that allow operators to manage imported goods’ biosecurity risks in accordance with departmental requirements, using their own premises, facilities, equipment and people. Approved arrangements were introduced by the Act and replace the previous ‘quarantine approved premises’ and ‘compliance agreements’.

Note c: ‘First points of entry’ are designated landing places or ports that ensure overseas aircrafts and vessels (and any goods on board) must arrive at a place that has the appropriate facilities to effectively manage biosecurity risk.

Note d: ‘Standing permissions’ were introduced with the Act to enable multiple entries to a non-first point of entry over a specified time period.

Source: ANAO based on departmental information.

2.26 Overall, the measures established under the Benefits Realisation Framework target those areas of the new legislative framework expected to have the most significant impact. For some measures, however, variations over time may be the result of changes in the operating environment, rather than reflecting the impact of the legislative changes. Also, the measures assessing the reduction in costs and regulatory burden aim to assess whether a variation is observed, but are not designed to quantify the value of these variations.

2.27 As part of the finalisation process for the Framework, there would be benefit in the department:

- ensuring that the measures are designed to determine changes directly related to the introduction of the new legislative framework as opposed to changes in the broader operating environment; and

- quantifying the value of changes in regulator costs, in addition to whether there has been any change observed.

2.28 The department advised the ANAO that it has commenced reviewing the assumptions in the 2014 Regulatory Impact Assessment to identify whether substantive change in costs or benefits had resulted from the implementation of the Act on 16 June 2016. The department expects that this review will be completed in 2017. As the reduction in costs and regulatory burden for external stakeholders was one of the key benefits expected from the transition to the new framework, the department should ensure that the Benefits Realisation Framework includes appropriate measures to quantify the costs and benefits that can be measured and analyse the material impacts of the regulation on industry.

Recommendation No.1

2.29 The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should:

- finalise and implement the Benefits Realisation Framework as a priority; and

- ensure that the Benefits Realisation Framework is effective in assessing the impact of the introduction of the new biosecurity legislative framework and the value of the reduction in costs and regulatory burden for external stakeholders.

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ response: Agreed.

2.30 The department agrees with the ANAO recommendation regarding the Benefits Realisation Framework (Framework). The implementation of the Framework is a priority for the department. The Framework was endorsed by the Programme Board and the measures are being implemented using baseline data that has been collected since commencement of the new legislation. The department is measuring the benefits that have been identified as flowing to clients, stakeholders and staff as a result of implementing the new legislation. As originally planned, the department is also reviewing the costings in the Regulatory Impact Statement for the biosecurity legislation looking for any variation in either the costs or savings with implementation.

Did the department capture the lessons learned from program implementation?

The department has appropriately captured the lessons learned from the program of work undertaken to implement the new biosecurity legislative framework. The successful implementation of latter stages of the biosecurity legislative framework will be heavily dependent on the department applying the lessons that it has learned from the initial stage of program implementation.

2.31 The internal audit final report on the Implementation of the Biosecurity Legislation Readiness Assessment, which was completed in May 2016 (discussed earlier at paragraph 2.16), focused on the identification of key learnings from Stage 1 implementation that could be used to inform the design and execution of current and future programs across the department. A summary of these key learnings was subsequently presented to the department’s Executive Management Committee in August 2016 and to the department’s Audit Committee in September 2016 (see Box 3).

|

Box 3: Implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework—Key learnings |

|

1. A defined program approach, and associated structures, should be mandated by the Executive and established early for future programs of work within the department. 2. The department should be mindful of the need for resources to support a program and enable the continuity of program activity, particularly for senior leadership roles. Key positions should be established early, with clear accountabilities, authority and visibility over the program. 3. The department should continue to promote the importance of good program management, particularly at the executive level, with the view to building the maturity of a program management culture. The department should invest in program management capabilities to support the growing number of programs of work being undertaken. 4. The program Board should be focused towards, and actively maintain, a program level view, and as appropriate, apply scrutiny at the project level, to ensure overall that activities are aligned. This could be coordinated through a centralised program office. 5. Programs should maintain well-defined progress reporting as a useful control to manage and communicate risks and issues. 6. Clearly establish and mandate the role of the program management office/program manager in aggregating and monitoring program progress, including projects. 7. A strong risk management strategy and plan should be established and communicated early. This should clearly articulate the program’s (and projects’) approach to managing risk. 8. Future programs should establish a schedule that integrates project schedules and key dependencies. Progress against this schedule should be continually monitored and reported. 9. Where projects have dependencies to, and are relied on by, other projects or business areas, clear acceptance criteria for project deliverables/products should be developed by the dependant areas. This includes providing clarity around the required output, quality and schedule. Any departures from the agreed scope and schedule should be agreed by dependant areas and at the program level. 10. The department should be aware of, and document dependencies within the program but also those external to it. Interaction with other initiatives, programs and key operational activities should be understood and documented. 11. A collaborative approach to program delivery will assist in ensuring there is the necessary discussion and information sharing between stakeholders around scope, schedule dependencies, risk and deliverables. 12. Robust assurance mechanisms should be put in place for future projects and programs. 13. Benefits management should start as early as possible to ensure that program and project activity is appropriately aligned to benefits. Once defined, accountability around the deliverable of benefits should be assigned, to ensure appropriate focus. |

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

2.32 A Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Framework for Stage 2 (June 2016–June 2018) and Stage 3 (July 2018–June 2021) has been developed and was endorsed by the Board in June and July 2016 respectively. The framework includes the documentation of lessons learned from Stage 1 as part of the first step in the Stage 2 implementation process.

2.33 The framework established for the implementation of Stage 2 incorporates many of the governance and program management controls that were adopted for Stage 1. In particular, the governance structure includes a Board chaired by a Deputy Secretary. An Implementation Office has continued to provide support, oversight, coordination and performance monitoring. In addition, the Assistant Secretary Working Group (AS Working Group), which was formed in March 2016 to manage Stage 1 risks, issues and dependencies, has been formally established as the Assistant Secretary Biosecurity Legislation Working Group and identified as a key element of the governance structure for Stage 2. It will be important for the Board to adopt a ‘whole-of-program’ view of implementation and to ensure that it is provided with high quality and timely performance reporting to underpin its oversight responsibilities.

2.34 A program plan, including the description of the program of work (objectives, scope, risk and dependencies) was endorsed by the Board in October 2016. The program and project schedules were, however, yet to be developed as at January 2017—six months into the two-year program. While Stage 2 implementation has a longer timeframe than Stage 1, it will be important for the department to finalise key governance documents in a timely manner and to subsequently control the risk of delays by adhering closely to the implementation schedule. The assurance plan, in particular, should include early point-in-time reviews to ensure that the implementation program is being delivered in accordance with established plans. In January 2017, the department advised that a program assurance framework, project briefs and a reporting approach (including templates) were endorsed at the Board meeting of December 2016. The department also advised that work was underway to develop blue prints and change impact assessments.

2.35 In the context of lessons learned from the initial implementation activities, the department should continue to embed enhanced oversight and management arrangements adopted for the latter part of Stage 1 implementation. This should include ensuring that roles, accountabilities and governance structures are clearly defined and effectively operating for future stages of the implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework and in relation to other key departmental-wide implementation programs. A key focus should be the early establishment of governance structures, underpinned by fit-for-purpose performance reporting that clearly outlines in a timely manner: progress against planned performance at both the project and program levels; and emerging risks and their impacts.

3. Program delivery

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ (the department’s) development of delegated legislation, creation of guidance materials and training programs, engagement with stakeholders and modification of relevant IT systems necessary for the implementation of the new biosecurity legislative framework.

Conclusion

The arrangements established by the department to support the operation of the new biosecurity legislative framework from 16 June 2016, including the development of policy and delegated legislation, creation of instructional material and the delivery of training for staff, implementation of IT system modifications and engagement with stakeholders, were, in the main, effective. There were, however, delays encountered in finalising a number of key activities, which ultimately reduced the time available to deliver important elements of the program, such as aspects of stakeholder engagement and IT system modifications. These delays also led to the reprioritisation of some implementation activities, including instructional material and IT changes, with delivery to occur in latter stages.

Introduction

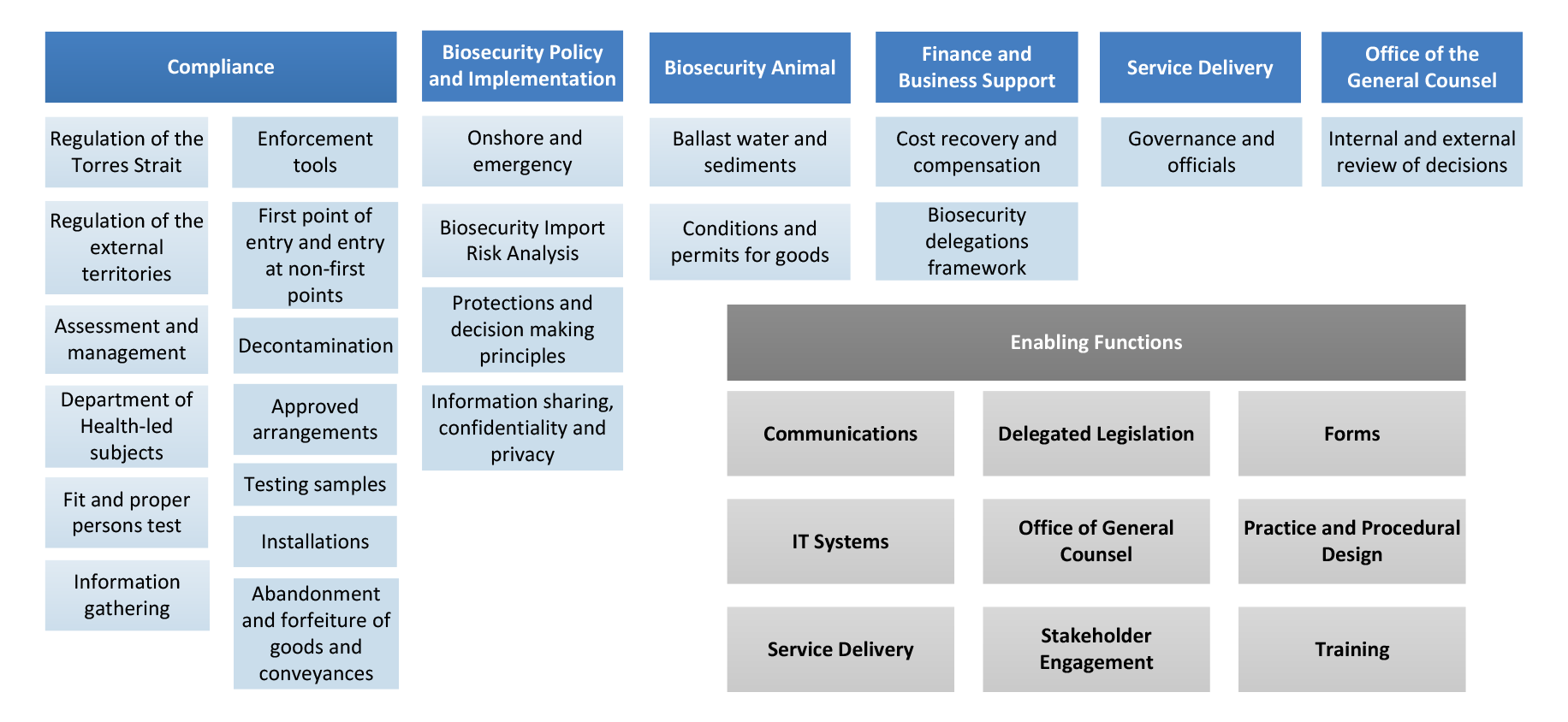

3.1 The implementation of Stage 1 of the biosecurity legislative framework involved the department delivering a range of interdependent activities over a 12-month period, including, for each specific legislative function, the development of detailed policy approaches, delegated legislation, and administrative practice (see Figure 3.1).18

Figure 3.1: Legislative and administrative framework

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

3.2 As outlined earlier, the implementation of the biosecurity legislative framework affected most areas of the department. The program delivery model selected by the department was underpinned by 23 projects that were to be delivered across five departmental divisions, each covering a specific legislative function. The key deliverables under the program included:

- policy to underpin the legislative changes;

- delegated legislation, including regulations, determinations and declarations (17 out of the 23 projects had regulations relating to their legislative function); and

- instructional and training material.

3.3 The department also identified the need for supporting functions (‘enablers’) to be in place to underpin the achievement of project objectives. The enabling functions included training, legal, instructional material, communications, stakeholder engagement and IT. The projects and the enabling functions are outlined in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Biosecurity legislation implementation projects and enabling functions

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Was the delegated legislation developed in a timely manner?

The department finalised the required delegated legislation in order to meet the timeframe for the commencement of the new framework. Delays encountered in the development process reduced the time available to undertake subsequent implementation activities, such as the development of instructional material and the delivery of training, and stakeholder consultation.

3.4 The department was responsible for coordinating the development and drafting of the required delegated legislation, including the provision of drafting instructions to the Office of Parliamentary Council (OPC)19 to ensure instructions reflected the relevant policy positions. Once the draft delegated legislation had been cleared for public release, it was to be published on the department’s website, with relevant notifications to occur and a process for submissions to be established.

3.5 In total, 26 pieces of delegated legislation were developed to support the operation of the new biosecurity legislative framework.20 Of these, 17 were released for public consultation and nine were subject to targeted consultation with relevant stakeholders.

3.6 A Regulation Development and Finalisation Strategy was presented to the Board on 10 July 2015 outlining the constraints and dependencies surrounding the development of delegated legislation. Regular updates (September 2015 and February 2016) were also provided to the Board on the development status of the regulations. The key constraints and dependencies that were identified included:

- drafting of the delegated legislation was dependent on the policy positions being finalised or close to finalisation;

- access to OPC drafting resources and time needed by OPC to develop legislation prior to public release (eight to ten weeks); and

- the World Trade Organization Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures includes guidelines that recommend releasing regulations for public consultation for at least 60 days. While adherence to the guidelines is not mandatory, the department aims to follow the guidelines where possible.

3.7 The Biosecurity Legislation Implementation Framework, which was endorsed by the Board in July 2015, indicated that delegated legislation would be finalised for public release in early October 2015. To meet this timeline, drafting needed to occur in the period up to September 2015.

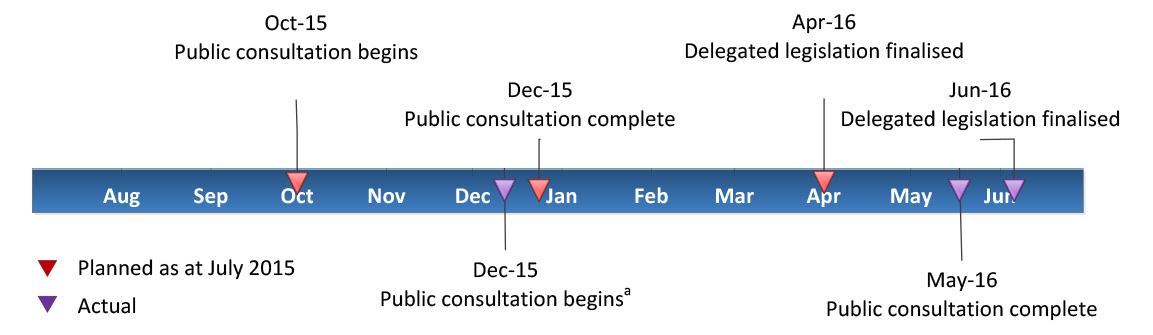

Development of delegated legislation

3.8 The development of all but one of the pieces of delegated legislation required to underpin the new framework was delayed, with their release for public consultation occurring between December 2015 and March 2016. Twelve of the 17 pieces of delegated legislation were not released for public consultation until February 2016, four months later than initially planned. These delays led to the finalisation and publishing of most of the regulations occurring in May and June 2016 (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3: Timeline for the finalisation of delegated legislation–planned vs actual

Note a: One piece of delegated legislation—the Biosecurity Import Risk Analysis (BIRA) regulation and guidelines—was released for public comment on 31 August 2015 and closed in December 2015. All other pieces of delegated legislation were released between December 2015 and March 2016.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

3.9 As a result of the delays in the release of delegated legislation for public consultation, 10 regulations were subject to consultation periods of less than the 60 days recommended by the World Trade Organization Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (between 14 and 48 days).

3.10 Over 100 submissions were received during the consultation period across all pieces of delegated legislation, with non-confidential submissions published on the department’s website. The department advised that all submissions were examined and all substantial issues addressed. Some of the key stakeholders, such as industry peak bodies or state and territory governments, were able to access drafts of the delegated legislation before public release, or had been able to discuss the implications of the legislation through broad and targeted engagement with the department.

Impact of delays on program implementation

3.11 Delays, risks and mitigation strategies were identified and reported to the Board on several occasions (including Board meetings of 18 September 2015 and 16 February 2016). The late release and finalisation of delegated legislation had a flow-on effect to other program deliverables, including the provision of staff training and the development of instructional material. The training and instructional material was not able to be developed against the finalised delegated legislation, with project areas outlining to the Board the difficulties encountered when developing instructional material on the basis of policy and procedures that had not been finalised in the delegated legislation (training requirements and the development of instructional material are discussed later in this chapter).

3.12 The feedback received by the ANAO from industry stakeholders and state and territory government representatives in relation to the level of engagement and the timeliness of this engagement during the development of the delegated legislation was generally positive. Several stakeholders commented, however, that earlier finalisation of the delegated legislation would have reduced industry uncertainty regarding specific operational changes (stakeholder engagement activities are discussed later in this chapter). The delays in finalisation of delegated legislation also resulted in reduced periods for public consultation and the time available for the department to consider feedback received.

Were departmental staff appropriately supported and trained to operate under the new framework?

The arrangements established by the department to amend and develop instructional material and to deliver training to assist staff to fulfil their requirements under the new legislation were appropriate.

Instructional material

3.13 As a result of the introduction of the new biosecurity legislative framework, a large amount of instructional material required to implement the new policies, processes and procedures needed to either be developed or amended. A spreadsheet developed by the department that listed all relevant instructional material affected by the introduction of the new framework contained over 1000 biosecurity-related documents that required review. The department estimated in August 2015 that:

- the amendment or renewal of all instructional material affected by the biosecurity legislative framework, if started in July 2015, would be completed by February 2018; and

- by the deadline for the introduction of the new framework in June 2016, 40 per cent of all relevant instructional material would have been completed.

3.14 Given the volume of material that was required to be updated or developed, the department decided to prioritise those materials that were essential for the commencement of the legislation on 16 June 2016, with the remaining materials to be reviewed during subsequent stages of the implementation program.

3.15 The relevant officers across the department with responsibility for the implementation of each of the 23 individual projects were required to identify and prepare instructional material that was necessary to underpin the operation of the new framework from 16 June 2016. The department’s Practice and Procedural Design Team supported project teams by providing advice, quality assurance and publication services, and for reporting on the status of instructional material development at the program level.

3.16 A Corporate Instructional Material Strategy and a Corporate Instructional Material Plan were developed in August 2015 and included guidance on how project teams should prioritise the amendment or development of instructional material. Specifically, priority was to be given to instructional material where:

- a new process was being created with the introduction of the new framework;

- an existing process had changed considerably; and/or

- current instructional material did not exist or was not clear and could result in non-compliance with the legislation.

3.17 The strategy also outlined that other instructional material, which was not required for the commencement of the new biosecurity legislation in June 2016, would be amended or developed during subsequent stages of the implementation.

Reduction in the number of instructional material pieces updated and late finalisation

3.18 The July 2015 program implementation plan indicated that all instructional material essential for the operation of the new system from 16 June 2016 was to be completed by December 2015. This timeframe was not met by the department. At its February 2016 meeting, the Board was advised that, while project teams had ‘narrowed down’ the list of instructional material to be amended or developed to 464 documents, work had commenced on only 72 of these.

3.19 Given the limited time remaining before commencement of the new framework and the slower than planned progress in amending or developing instructional material, the Board agreed in February 2016 to review the strategy underpinning the prioritisation of the documents with a view to identifying only those materials that posed a high change risk.21 The amendment or development of instructional material presenting a ‘Moderate’ to ‘Low’ change risk was deferred to Stage 2 implementation. This reprioritisation was conducted in early March 2016 under the leadership of the AS Working Group (discussed earlier at paragraph 2.15). The department advised that, in order to gain assurance that critical instructional material had not been overlooked, additional workshops were conducted internally with project teams, policy owners and subject matter experts. The department developed two matrices that were used to capture progress on the instructional material deemed critical for commencement of the new framework.

3.20 As a result of this reprioritisation, 160 pieces of instructional material were amended (148 documents) or developed (12 new documents) and uploaded to the Instructional Material Library before 16 June 2016. Around 75 per cent of the documents were made available to staff in the period from 1 May 2016 to 15 June 2016, which was five to six months later than the planned finalisation date. Further, in contrast to the department’s initial estimate that 40 per cent of the 1000 documents requiring amendment or development would be finalised by 16 June 2016, 160 (16 per cent) were finalised by the deadline.

3.21 The delays in finalising the amendment and development of instructional material meant that the material was not always available for the training sessions conducted for staff. In practice, training and instructional material was being developed in parallel with training activities. As a consequence, staff had limited opportunity to familiarise themselves with the instructional material in the lead up to and during the course of training. There was also an increased risk that the training being delivered was not sufficiently aligned with the instructional material. This risk was identified by the department. The department advised that, to manage this increased risk, it used scenario-based training to ensure that their staff understood the changes in work practices under the new legislative framework.

3.22 A post implementation issues register was also developed for staff to report any operational issue identified following the commencement of the new framework. As at 1 August 2016, 108 issues had been lodged by biosecurity officers. The department advised that as at 16 August 2016, all but 10 non-critical issues had been resolved. The department also advised the ANAO in November 2016 that an external review of the development and publication process for instructional material was underway.

Training

3.23 The new biosecurity legislative framework establishes minimum training requirements for new biosecurity officers and new biosecurity enforcement officers, with these officers to be authorised under the Act.22 Those officers appointed as quarantine officers under the previous Quarantine Act that were transitioning to the role of biosecurity officers under the new framework on 16 June 2016 were not required to undertake the minimum training requirements, on the basis of their existing training as quarantine officers.23 Nevertheless, the department encouraged these officers to undertake the appropriate level of training for their role.

3.24 The department developed the following three categories of training to deliver the required staffing capability to support the introduction of the new framework:

- Category A: Introduction to the Biosecurity Act 2016. An introductory e-learning course that was required for all biosecurity officers and biosecurity enforcement officers. Other staff members were also encouraged to complete the course.

- Category B: Biosecurity Legislation Training. A classroom delivered course that included four learning modules, outlining the changes to the legislation. The training was required for all biosecurity officers and biosecurity enforcement officers.

- Category C: Specialist Training. Role specific training developed by the department and an external provider. A number of role specific training courses were included: infringement, enforcement and ballast water courses; and scenario-based training such as courses aimed at cargo and airport inspectors. This training was required for officers undertaking specific roles.

Training delivery process

3.25 The department used system data to record staff attendance at training sessions and the completion of e-learning modules to ensure required training had been completed. As at 14 June 2016, 87 per cent of staff or more had completed the required training (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Training completion rate (14 June 2016)

|

Training category |

Required (No. of staff) |

Completed (No. of staff) |

Completed (%) |

Delivery period |

|

Category A |

3320 |

3132 |

94 |

From February 2016 |

|

Category B |

2446 |

2424 |

99 |

From April 2016 |

|

Category C |

1779 |

1543 |

87 |

From May 2016 |

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

3.26 A number of additional e-learning courses were updated to support the implementation of the new framework, including Good Decision Making, Evidence Handling and Regulatory Officer Note-taking. All departmental staff were encouraged to complete these courses, and staff with specific functions were required to complete courses relevant to their duties (for instance, biosecurity enforcement officers were required to complete Good Decision Making and officers delegated to issue infringement notices were required to complete Evidence Handling and Regulatory Officer Note-taking). Departmental data indicates that, as at 14 June 2016, 51 per cent of staff or more had completed the additional e-learning courses.

3.27 In addition to the three categories of training, the department also conducted 14 workshops in February and March 2016 to assess the impact of change on service delivery areas. The aim of the workshops was to familiarise subject matter experts (officers identified as having a detailed understanding of work processes, training and instructional material) with the changes being introduced to support the operation of the new framework and establish a network of ‘champions’ to support frontline staff through the legislative change.

3.28 The department also established a dedicated 24-hour telephone line and email address to manage all staff, client and stakeholder enquiries relating to the legislation. The Implementation Office managed the telephone line and email address. Departmental records indicate that, during June and July 2016, the telephone line and email address received over 200 external and 37 internal enquiries, with the most common queries relating to approved arrangements and import permits and conditions.

Effectiveness of support provided to staff

3.29 The department initially planned for staff training to be conducted between February and early June 2016. The delays in finalising other elements of the implementation program (in particular instructional material) impacted on some of the training courses, in particular specialist training (Category C) with timelines required to be compressed for the development of relevant training content. The courses were, however, delivered in line with the planned timeframe.

3.30 To assess the effectiveness of training and the level of preparedness of departmental officers for the implementation of the new framework, the department conducted two evaluations.

- The first evaluation was conducted in May 2016 as part of Quality Review 3 (discussed earlier at paragraph 2.17). This evaluation included a survey and a series of 12 interviews with staff aimed at gaining a qualitative understanding of the survey responses. The staff survey was emailed to 850 staff that had completed all three training categories, with 357 responses provided (42 per cent). The survey results indicated that a majority of respondents (over 80 per cent) considered that they: understood their new responsibilities and the impact of the biosecurity legislative framework on their role; and were confident that they had the necessary tools to enable them to perform their work under the new framework.

- The second evaluation was conducted in September 2016 and consisted of a follow-up staff survey, using the same questions as the May 2016 survey.24 The survey was emailed to 2015 biosecurity officers, including those officers who had previously been invited to complete the May 2016 survey and another 1200 officers who had completed the required training after May 2016. A total of 641 responses were provided (32 per cent). As was the case with the earlier survey, the survey results indicated positive results (over 80 per cent) from staff in relation to role clarity and the adequacy of tools and materials. A comparison of results between the May and September 2016 surveys also shows an overall improvement in the responses received.

3.31 Notwithstanding the positive survey results, around 20 per cent of respondents did not consider that work instructions, systems and training developed or updated for the biosecurity legislation provided adequate support. The department advised the ANAO that further training, system updates and improvements to instructional materials are being progressed as business-as-usual divisional activities and as part of Stage 2 of implementation.

Did the department engage effectively with stakeholders during the implementation process?

The department effectively engaged with stakeholders, including relevant government entities and key industry bodies. The majority of stakeholders indicated that they were, overall, satisfied with the level and quality of the department’s engagement in relation to the introduction of the new framework.

3.32 Given the extent of the changes introduced by the new biosecurity legislative framework, early and effective engagement with stakeholders—including Commonwealth and state government entities, industry and the general public—was a key requirement for successful implementation.

Delivery of engagement activities

3.33 An External Media Communication Strategy was developed by the department and endorsed by the Board in September 2015. The purpose of the strategy was to ensure that stakeholders would be aware of, and involved in, the changes to be introduced by the new biosecurity legislative framework, and also that they were well positioned to comply with relevant requirements from commencement. The strategy identified two key target groups: