Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of the Annual Performance Statements Requirements 2017-18

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to continue to examine the progress of the implementation of the annual performance statements requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) by selected entities.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) provides the basis for the Commonwealth performance framework (the framework). The framework consists of the PGPA Act, the accompanying Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) and guidance issued by the Department of Finance (Finance). It is principles-based and requires entities to publish planned performance information, to allow an assessment of entities’ progress against their purposes when reported at year-end.

2. The Independent review into the operation of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Rule (PGPA Review), commissioned by the Minister for Finance, notes:

Citizens have a right to know how their money is used and what difference that is making to their community and the nation - what outcomes are being achieved, how, and at what price.

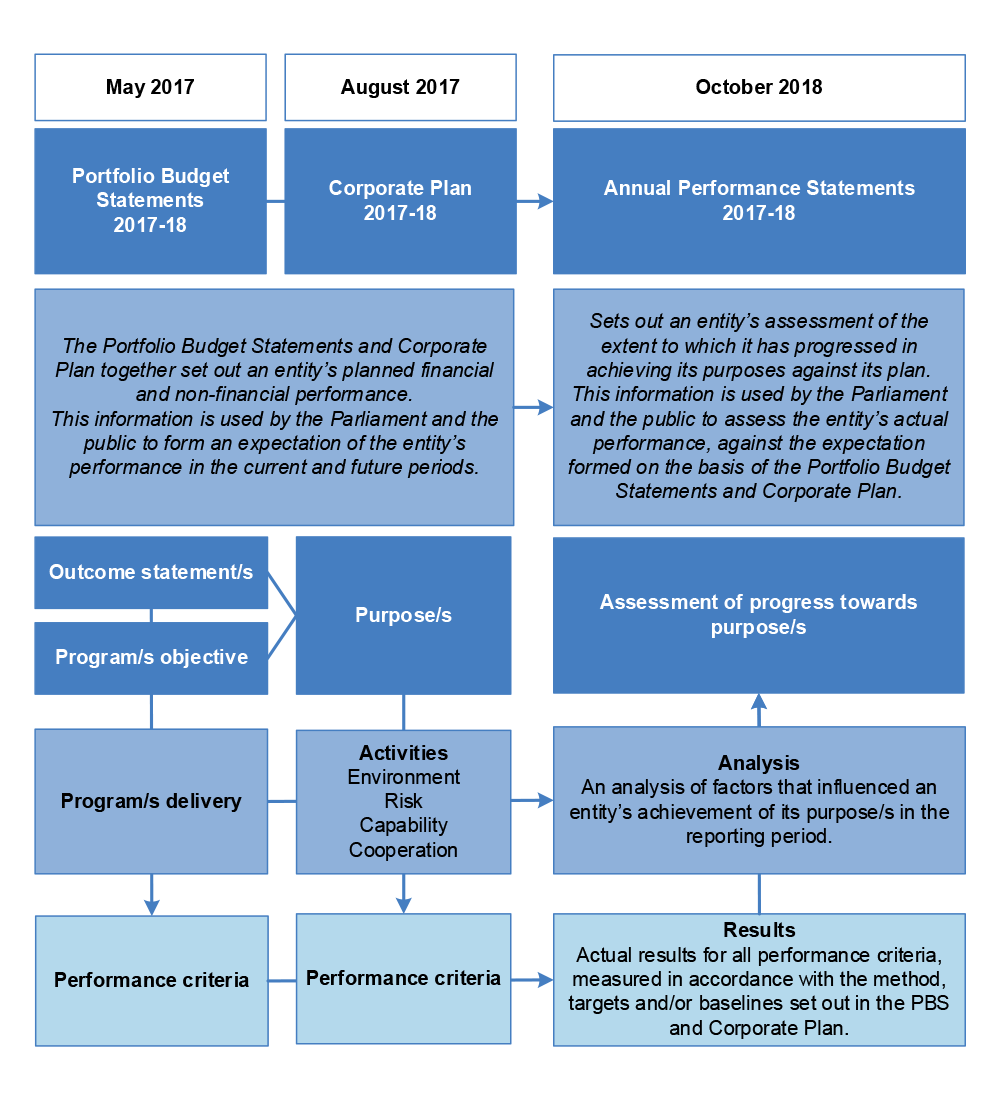

3. By requiring Commonwealth entities to publish planned financial and non-financial performance information, the framework aims to provide more transparent and meaningful information to the Parliament and the public. There are three key accountability documents produced by entities under the framework:

- Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) — the primary financial planning document;

- Corporate Plans — the primary non-financial planning document; and

- Annual Reports, incorporating financial statements and Annual Performance Statements (performance statements), which publish the financial and non-financial results achieved by entities.

4. The PBS and corporate plan set out an entity’s planned financial, and non-financial, performance. This information is used by the Parliament and the public to form an expectation of the entity’s performance in current and future reporting periods. Performance statements then set out an entity’s assessment of the extent to which it has progressed in achieving the purposes set out in the PBS and corporate plan. This enables the Parliament and the public to assess an entity’s actual performance, against the expectation formed from the information set out in the PBS and corporate plan.

5. Alignment between the information presented in all three documents is intended to improve the line of sight between the use of public resources and the results achieved by entities. The importance of establishing this ‘clear read’, to enhance the transparency and meaningfulness of information presented to the Parliament and the public, has been emphasised by Finance and the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).

6. The appropriateness of the performance criteria presented by entities in the PBSs1, corporate plans and performance statements2, is also critical to fulfilling the transparency and meaningfulness aims of the framework. Criteria that set a minimum standard for the quality of performance information are not defined in the PGPA Act or Rule, however Finance has provided guidance to entities on the characteristics of ‘good’ performance information — relevant, reliable and complete. The guidance also includes other issues entities may consider in developing ‘good’ performance information (refer to Appendix 4).3 The PGPA Review notes that ‘We believe entities should have clear criteria to guide the development of performance information’ and has recommended the PGPA Rule be amended to specify a minimum standard for entity performance reporting.4

7. In the absence of formal criteria in the PGPA Act or Rule, the ANAO drew on Finance’s guidance, and other relevant reference points5, in the development of an audit criteria for assessment of the appropriateness of performance information. This criteria can be found at Appendix 5 and has been used in the ANAO’s audits of entity performance statements to date.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

8. The PGPA Act commenced on 1 July 2014, and entities were required to present their first corporate plans and performance statements from 1 July 2015.6 July 2018 marked the commencement of the fourth year of Commonwealth entities’ implementation of the framework, and October 2018 the conclusion of the third performance measurement and reporting cycle.

9. As noted by the JCPAA, the framework ‘seeks to improve public sector performance information to strengthen accountability’.7 Observations from previous audits of entities’ performance statements, and recommendations from the JCPAA, indicate the need for sustained attention in this area to meet this aim, particularly with regard to:

- the development of performance measures that are relevant, reliable and complete;

- the provision of meaningful information to the Parliament to demonstrate progress against an entity’s purpose and meet the requirements, and the objects, of the PGPA Act;

- consideration of an entity’s efficiency in meeting its purpose; and

- review by audit committees of their accountable authority’s performance reporting.

10. This performance audit is the ANAO’s third audit of entities’ progress in the implementation of the framework. Given the time elapsed, entities should have fully embedded the principles into their organisational processes, to support the presentation of meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public.

11. The ANAO’s continuing focus in this area is expected to assist in keeping the Parliament, the government, and the public informed on implementation of the framework and to provide insights to entities to encourage improved performance.

12. To date, the ANAO’s audits of performance statements have considered entities who focus on program-delivery, and the use of quantitative measures was more prevalent. In contrast, the entities selected for this audit are more focused on policy development, coordination and leadership. These types of activities typically generate more qualitative, than quantitative, information.

Audit objective and criteria

13. The objective of the audit was to continue to examine the progress of the implementation of the performance statements requirements under the PGPA Act and the PGPA Rule by the:

- Attorney-General’s Department (AGD);

- Department of Education and Training (Education);

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT); and

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

14. The audit was also designed to:

- provide insights to entities more broadly, to encourage improved performance; and

- continue the development of the ANAO’s methodology to support the possible future implementation of annual audits of performance statements.

15. To form a view against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- entities complied with the requirements of the PGPA Act and PGPA Rule;

- the performance criteria presented in the selected entities’ PBSs, corporate plans and performance statements were appropriate; and

- entities had effective supporting frameworks to develop, gather, assess, monitor, assure and report performance information.

Conclusion

16. There has been improvement over time in the entities’ performance statements, and all largely comply with the requirements of the PGPA Act and accompanying PGPA Rule to publish performance information. However, the information presented in the performance statements continues to fall short of fully meeting the object8 of the PGPA Act — to provide the Parliament and the public with meaningful information.

17. In this report, all of the entities met the requirement to prepare, and table in Parliament, performance statements under section 39 of the PGPA Act. The entities’ performance statements also demonstrated the principles of ‘plain English and clear design’. However, the clear acquittal of results against performance criteria presented in the PBS, and the presentation of more meaningful analysis, are areas requiring improvement by entities.

18. The selected entities’ measurement and reporting of their performance through corporate plans and performance statements has generally improved. However, the reliability and completeness of performance criteria remain areas requiring improvement by all entities. While some improvements are already evident in the selected entities’ 2018–19 Corporate Plans, further work is necessary to establish the basis required to provide meaningful information to the Parliament and the public about the entities’ progress in achievement of their purposes.

19. Each of the entities’ processes to collect, assess, assure and report performance information were largely effective. However, there are opportunities for these processes to further mature. AGD, Education and PM&C’s performance statements accurately present their performance. However, the ANAO is unable to conclude whether, for Priority Functions 1 and 2, DFAT’s performance statements accurately present its performance. Notwithstanding, all of the selected entities retained sufficient records to support the results presented in the performance statements.

Supporting findings

Compliance with the PGPA Act

20. All of the entities met the requirement to prepare and table performance statements under section 39 of the PGPA Act. Each entity’s performance statements also contained the required elements (statements, results and analysis) set out in section 16F of the PGPA Rule. However, AGD and DFAT’s performance statements did not clearly present results against all of the performance criteria presented in their 2017–18 PBSs. In addition, the analysis presented by all four entities requires improvement to meet the Rule, and provide meaningful information to support the Parliament and the public’s assessment of the entities’ performance.

21. Each entity’s performance statements are structured to support a reader’s understanding of the content, demonstrating the characteristics of ‘plain English and clear design’ under the annual reporting requirements.9 However, as noted earlier, the need for clearer alignment between the results presented by entities in the performance statements and the original measures, and improving the quality of analysis remain areas for improvement.10

Measurement and reporting of performance

22. AGD’s corporate plan provides a clear basis to support its performance measurement and reporting by clearly expressing its purpose, and significant activities. DFAT, Education and PM&C could each improve their corporate plans by more clearly describing the activities to be undertaken to achieve their purpose/s. PM&C should relabel its mission as its purpose, and the stated purposes as objectives or priorities, to make clear to a user the impact intended to be measured. Establishing a ‘clear read’ between the PBS and corporate plan is also an area where AGD, DFAT and PM&C should improve, to support performance measurement and reporting in the performance statements.

23. Each of the entities’ performance criteria require improvement to fully meet the characteristics of appropriateness — relevant, reliable and complete. The majority of performance criteria were relevant, or mostly relevant, however the majority did not meet, or only partly met, the reliability criterion. The completeness of performance criteria also requires improvement by all entities through developing measures of efficiency, and demonstrating an entity’s intended progress across the life of the corporate plan and beyond.

24. PM&C’s 2018–19 Corporate Plan provides the Parliament and the public with limited insight into how the department intends to measure its performance compared to the 2017–18 Corporate Plan. The remaining entities have made changes to their 2018–19 corporate plans which provide an improved basis for performance measurement and reporting. However, Education would benefit from reintroducing activities to its 2018–19 Corporate Plan that describe what the department does, or intends to do.

Systems and processes to support measurement and reporting of performance

25. The entities’ processes to inform the coordination and collation of the performance statements were effective. There are opportunities for these processes to further mature, focusing in particular on the quality and meaningfulness of regular internal reporting and monitoring of performance information to support decision making.

26. AGD’s, Education’s and PM&C’s systems and methodologies to collect and report performance information were largely effective. DFAT’s sole reliance on case studies and reviews selected ex-post as its performance criteria impacted the department’s development and/or documentation of effective systems and methodologies to support its performance reporting for Priority Functions 1 and 2.

27. All four entities had processes to obtain assurance over their performance statements. The observations made in other sections of this report in regard to the entities’ compliance with the PGPA Rule, and the appropriateness of measures, systems and methodologies indicate that there is still some way to go in the maturity of these processes.

28. AGD, Education and PM&C’s 2017–18 Performance Statements accurately present their performance. The ANAO is unable to conclude whether, for Priority Functions 1 and 2, DFAT’s performance statements meets this requirement, as the department’s sole reliance on case studies does not provide a complete basis for this assessment. Notwithstanding, DFAT and the other selected entities retained sufficient records to support the results presented in the performance statements.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.31

Entities improve the analysis presented in their performance statements to ensure a reader understands the connection between the results presented, the internal or external environmental influences that affected those results, and how these informed the entities’ assessment of progress against their purpose.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

Department of Education and Training response: Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.60

Entities improve the reliability of performance measures presented in their PBSs and corporate plans, by providing the Parliament and the public with information on the information sources and methodologies intended to be used to measure their performance. This information should be sufficient to enable a reader to make an assessment of the reliability of those methods, and develop an understanding of the intended result.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

Department of Education and Training response: Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.86

Entities review their performance measurement and reporting frameworks to develop measures that also provide the Parliament and public with an understanding of their efficiency in delivering their purposes.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed with qualification.

Department of Education and Training response: Agreed.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed with qualification.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed with qualification.

Summary of entity responses

29. Summary responses from the selected entities are provided below, while the full responses are provided at Appendix 1.

Attorney-General’s Department

I welcome the report and acknowledge the recommendations made to support the presentation of meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public. Involvement in the Audit provided AGD with invaluable insights to enhance our 2018–22 Corporate Plan and future annual performance statements.

We generally support the findings of the report, but note there are challenges in addressing recommendation 3.

I would like to express the thanks of the Attorney-General’s Department to your staff for the professional and collegiate manner in which this audit was conducted. We are committed to ongoing improvement in this area.

Department of Education and Training

The Department of Education and Training welcomes the audit’s findings in relation to strength of its systems and processes for performance reporting. The department notes and agrees with the areas for improvement articulated in the three recommendations and will continue to strengthen its measurement and reporting of performance in line with the broader findings of the audit. The findings highlighted in the ANAO audit will help contribute to strengthening the department’s approach to its 2019–20 performance framework and 2018–19 annual performance statements.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) welcomes the majority of ANAO’s observations, which mirror our own self-assessments and represent areas we are working to strengthen.

DFAT continues to benefit from the principles-based approach of the PGPA Act and its emphasis on performance and utility over compliance. We have embarked on an ambitious reform program of performance planning and monitoring. We note that the ANAO acknowledged some of our early gains, including the enhanced 2018-2019 Corporate Plan, the new quarterly performance report process, and improvements to overall performance information. We will continue to work to align the portfolio budget statements and corporate plan.

DFAT notes the challenges the Australian Public Service – as well as state and international entities – face in designing measures and methodologies for policy performance. That said, the department is determined to make further progress and will work across government to identify improvements. We would welcome guidance and identification of good practice examples.

DFAT reiterates its support for the ANAO’s live audit process. We will separately provide the ANAO with suggestions on how to further improve the process, with a particular focus on the provision of timely guidance and feedback.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) welcomes the report’s findings that the results presented by PM&C against each measure are supported by appropriate records, and accurately present PM&C’s performance. I also appreciate the positive comments in relation to the structure of the performance statement meeting readers’ needs, and the use of internal audit to improve performance statement processes.

As part of continuous improvement, PM&C has already put improved processes in place for the selection and monitoring of the 2018–19 performance measures, involving Deputy Secretary sign-off and regular performance reporting to the Executive Board.

Department of Finance

The Department of Finance (Finance) notes the audit findings and supports the three recommendations of the report.

Finance is committed to continuing to work closely with the ANAO and the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit to help improve the quality of performance reporting. The audit’s findings and recommendations are an important input to this process.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

30. The key learnings summarised in Auditor-General’s Reports No.58 2016–17 Implementation of the Annual Performance Statements Requirements 2015–16 and No.33 2017–18 Implementation of the Annual Performance Statements Requirements 2016–17 remain valid reference points for entities seeking to improve their performance measurement and reporting.

31. Below is a summary of key messages, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Commonwealth entities.

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) provides the basis for the Commonwealth performance framework (the framework). The framework consists of the PGPA Act, the accompanying Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) and guidance issued by the Department of Finance (Finance). It is principles-based and requires entities to publish planned performance information, to allow an assessment of entities’ progress against their purposes when reported at year-end.

1.2 The Independent review into the operation of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Rule, commissioned by the Minister for Finance, notes:

Citizens have a right to know how their money is used and what difference that is making to their community and the nation - what outcomes are being achieved, how, and at what price. 11

1.3 By requiring Commonwealth entities to publish planned financial and non-financial performance information, the framework aims to provide more transparent and meaningful information to the Parliament and the public. The aim is to provide users with a greater understanding of how entities plan to, and have, utilised resources, not just in producing outputs, but also the entity’s impact and efficiency in delivering outcomes.

1.4 The PGPA Act commenced on 1 July 2014, and entities were required to present their first corporate plans and performance statements from 1 July 2015.12 July 2018 marked the commencement of the fourth year of Commonwealth entities’ implementation of the framework, and October 2018 the conclusion of the third performance measurement and reporting cycle.

Commonwealth performance framework

1.5 The Commonwealth performance framework came into effect with the commencement of the PGPA Act. It has three inter-dependent elements — purposes, operating context and performance information — used to demonstrate the achievement of purposes. Under the PGPA Act and Rule, an entity’s purpose/s may be their objectives, functions or role, which are undertaken to achieve their outcomes.

1.6 An important element of the framework is the clear alignment of the purpose/s to the planned outcomes of the entity13, and that the performance information provided by the entity provides the Parliament and the public with information to assess an entity’s progress towards achieving their purposes. Alignment of all of the elements of the framework is intended to improve the line of sight between the use of public resources and the results achieved by entities. The key accountability documents produced under the framework, including the expected alignment and/or information flows, are demonstrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Commonwealth performance framework — 2017–18

Source: ANAO analysis of the PGPA Act, PGPA Rule, and Department of Finance guidance.

1.7 PBSs set out planned financial performance, and are required to describe at a strategic level, the planned outcomes intended to be achieved with the funding appropriated by the Parliament. Entities are also required to clearly map the outcomes, programs and performance measures from their PBS to their corporate plan purposes, to ensure a clear read between the documents.14 The performance information in an entity’s PBS must be able to be read across to an entity’s corporate plan. Aligning the corporate plan and PBS provides readers an insight into the expenditure expected to achieve that performance and aligns planned financial and non-financial performance.

1.8 As the primary planning document, the corporate plan sets out planned non-financial performance and provides the reader with an understanding of how an entity intends to measure and assess its actual performance. This includes a description of the entity’s purposes, and the planned inputs, key activities, outputs and the outcomes or impacts to be achieved by the entity, against their purposes. To make this information meaningful, and allow users to form their own expectations, entities must include measurement methodologies and targets or baselines against which progress can be assessed.

1.9 The results the entity has achieved against the performance measures and targets set out in the entity’s PBS and corporate plan, and accompanying analysis, are presented in the subsequent performance statements.15 Performance statements, included in an entity’s annual report, provide the Parliament and the public with the entity’s assessment of the extent to which it has progressed in achieving its purposes, as set out in the corporate plan.16 This information can then be used by the Parliament and the public to assess whether the entity’s strategies and activities have been successful in delivering the expected outcome.

1.10 Since its inception, Finance has reinforced the framework’s intention to give entities the flexibility to apply a fit-for-purpose approach to their performance measurement and reporting.17 Resource Management Guide No. 130: Overview of the Enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework notes:

Each entity needs to consider how best, and by what method, to gather the necessary information to tell its performance story. The types of information needed will depend on the nature, size and complexity of the entity, its purposes and the characteristics of its activities – and may differ across different entities.

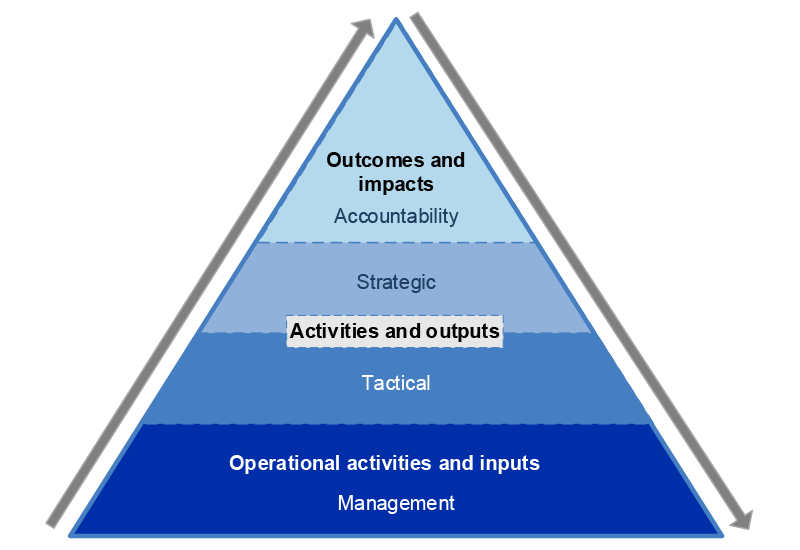

1.11 To support this aim, entities have been encouraged to broaden their performance measurement frameworks to generate better qualitative and quantitative information through tools such as benchmarking, peer reviews, and comprehensive evaluations.18 Guidance from Finance also advises that good performance information can be categorised by how it communicates accountability, strategic, tactical, or management related information, and how the information presented at these levels interact to inform decision-making19, as demonstrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Performance information hierarchy

Source: ANAO analysis of the Department of Finance, Resource Management Guide No.131: Developing Good Performance Information, April 2015, pp. 12–13, 30 & 45.

1.12 As noted earlier, the intended users of the PBS, corporate plan, and performance statements are the Parliament and the public. It is for this reason that entities should consider whether the level and volume of performance information presented meets users’ needs.

1.13 Accountability performance information demonstrates whether the use of public resources is making a difference and delivering on government objectives. This is the level of performance reporting that is the focus of the PGPA Act. Performance reporting for accountability purposes is of most interest to the Parliament and the public, and should be balanced with the other levels of the performance information hierarchy. 20

1.14 Well-presented and easily interpreted accountability information is essential to enable governments to coordinate policy, clarify objectives, enhance transparency and accountability, improve service delivery, and keep the wider community informed. While strategic, tactical, and management performance information are also important, they should be used to support and advance accountability information, rather than replace it. Performance measures that address these lower levels of information, without sufficient connection to accountability information, may not be appropriate to include in the corporate plan and performance statements. 21

1.15 As the key accountability documents in the performance framework, an entity’s PBS, corporate plan, and performance statements should provide the Parliament and the public with sufficient information to determine what level of performance is being planned and communicated for each measure, and the insights this might provide. If a user is required to rely on an in-depth understanding of an entity, the basic information needs of the Parliament and public are not being met. In this circumstance, the performance measures and the PBS, corporate plan and/or performance statements should be reviewed.

Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit review

1.16 Improving the Commonwealth performance framework has been a long-term focus of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). 22 On 6 December 2017 the JCPAA released Report 469: Commonwealth Performance Framework. The report included ten recommendations, five of which related to the committee’s consideration of ANAO Report No.58 2016–17 Implementation of the Annual Performance Statements Requirements 2015–16. Recommendation 6 was that ‘The Australian Government amend the PGPA Act, and the accompanying rules and guidance as required, as a matter of priority, to enable mandatory audits of performance statements by the Auditor-General …’.23 The Committee also referred this matter to the attention of the ‘Independent Review of the PGPA Act’, and is discussed further below.

1.17 The report also included observations in regard to entity performance measurement and reporting relevant to this audit, including the need:

- to use a mix of qualitative and quantitative performance information, along with relevant contextual information and analysis, to focus on entity impacts and outcomes (reflecting the move away from key performance indicators based solely on measuring inputs and outputs);

- for narrative utilised as part of qualitative performance information to be evidence-based, reliable and robust;

- for further work on measurement methodologies for qualitative performance information, drawing on local and international research and practice in this area;

- for further collaborative work on measuring and articulating performance outcomes, to build consistency and maximise reporting efficiencies; and

- for methodologically robust attribution of entity activities to outcomes that makes accountabilities clear.24

Review of the PGPA Act and Rule

1.18 In September 2017, the Minister for Finance appointed Mr David Thodey AO and Ms Elizabeth Alexander AM to undertake the review of the PGPA Act and Rule (PGPA Review) in accordance with section 112 of the PGPA Act. The review included consultation with the JCPAA, ANAO, Department of Finance, and other Commonwealth entities, with the following objective:

- To examine whether the operation of the PGPA Act and Rule is achieving the objects of the PGPA Act in a manner consistent with the guiding principles;

- To identify legislative, policy or other changes or initiatives, to enhance public sector productivity, governance, performance and accountability arrangements covered by the PGPA Act; and

- To examine whether policy owners’ implementation of the PGPA Act and Rule has appropriately supported their operation in Commonwealth entities.

1.19 The final report was released in September 201825, outlining 52 recommendations, fourteen of which relate to the performance framework.26 In response to the JCPAA’s recommendation (see paragraph 1.16 above), the reviewers supported the ‘Auditor-General getting legislative power to conduct mandatory assurance audits of annual performance statements’. However, they considered that it is ‘too early to put this arrangement in place’, and that ‘practice across the Commonwealth is not mature enough to support systematic assurance audits of annual performance statements’.27 Consequently, the reviewers directed the following recommendation to the Finance Minister [and the government]:

8. The Finance Minister, in consultation with the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, should request that the Auditor-General pilot assurance audits of annual performance statements to trial an appropriate methodology for these audits. The Committee should monitor the implementation of the pilot on behalf of the Parliament.

1.20 The Government is yet to respond to the report and accompanying recommendations. Until a request as outlined in Recommendation 8 is made, the Auditor-General will continue to position the ANAO to transition to a program of mandated annual audits of entity performance statements, as previously flagged to the JCPAA28. Such a program would provide a similar level of assurance to the Parliament and the public as provided by mandatory annual audits of financial statements. This ongoing focus on performance statements is reflected in the Auditor-General’s Annual Audit Work Program 2018–19, which includes proposed audits of the Implementation of annual performance statements requirements in 2018–19, and Commonwealth performance reporting and the ‘clear read’ principle.29

Roles and responsibilities

Minister for Finance and the Department of Finance

1.21 The Minister for Finance is the Minister responsible for administering the PGPA Act, and is supported by the Department of Finance (Finance). Finance is responsible for the whole-of-government administration of the Commonwealth performance framework and related legislation.

1.22 To assist entities in implementing the performance framework, Finance has published written guidance, including Resource Management Guides (RMG) and lessons learned papers. During 2017–18 Finance re-issued the following RMGs relevant to the framework:

- RMG No. 134 Annual performance statements for Commonwealth entities, July 2017;

- RMG No. 202 Guide for non-corporate commonwealth entities on the role of audit committees, and an accompanying model audit committee charter, May 2018; and

- RMG Nos. 135; 136; and 137 Annual reports for non-corporate, corporate, and Commonwealth companies, May 2018.

1.23 Finance also released the 2017–18 Corporate Plans Lessons Learned paper in November 2017, and the 2016–17 Annual Performance Statements Lessons Learned paper in April 2018. Finance also hosts Performance Community of Practice forums to facilitate the sharing of expertise and better practice. Forums were held during 2017–18 in December 2017, at multiple locations, to discuss the 2017–18 Corporate Plans Lessons Learned paper. Further forums were held in November and December 2018 focussed on recommendations arising from the PGPA Review, and Finance’s proposed approach to addressing Recommendation 4 of the JCPAA’s Report 469: Commonwealth Performance Framework30.

1.24 In considering the quality of performance reporting as part of the PGPA Review, the reviewers directed the following recommendation to Finance:

The Department of Finance should continue to develop guidance on performance reporting to assist Commonwealth entities to meet the requirements of the PGPA Act and Rule and develop high-quality performance reports. This will also assist audit committees to review performance reporting.

1.25 The ANAO noted that each of the selected entities had engaged with Finance to seek feedback and/or guidance during 2017–18. This was through direct contact with representatives of the department, and/or participation in Finance’s Community of Practice forum. In discussion with the ANAO, the selected entities noted that an increased focus on the development and use of qualitative performance measurement methods was a particular area where there would be value in enhancing existing guidance.

Responsible Ministers

1.26 Under the PGPA Act, a responsible Minister may:

- access the records kept about the performance of the entities within their portfolio (section 37); and

- request that the Auditor-General examine and report on the performance statements of entities within their portfolio (section 40).

Accountable authorities

1.27 Accountable authorities are responsible for the implementation of the requirements of the performance framework in their entities. Part 2-3 of the PGPA Act — relating to planning, performance and accountability — sets out the requirements of accountable authorities. The requirements relevant to this audit include:

- preparing a corporate plan each reporting period that complies, is published, and is provided to the responsible Minister and Finance Minister in accordance with any requirements prescribed by the PGPA Rule;

- keeping records about the entity’s performance in accordance with any requirements prescribed by the Rule;

- measuring and assessing the entity’s performance and complying with any requirements prescribed by the Rule; and

- preparing performance statements about the entity’s performance that comply with any requirements prescribed by the Rule, and including these statements in the annual report. 31

Audit committees

1.28 Audit committees are appointed by the accountable authority of an entity. The functions of an audit committee are prescribed by section 17 of the PGPA Rule, and must be set out by the accountable authority in a written charter. The required functions of an audit committee are detailed in the box below.

|

Box 1: Functions of the audit committee |

|

PGPA Rule subsection 17(2) outlines the functions of the audit committee: The functions must include reviewing the appropriateness of the accountable authority’s:

|

1.29 In May 2018, Finance released its Resource Management Guide No. 202: A guide for non-corporate Commonwealth entities on the role of audit committees, accompanied by a Model audit committee charter. The guide is intended to inform accountable authorities of the requirements and expectations of audit committees, as set out by the PGPA Rule, and provides guidance on the skills and knowledge required of members.

1.30 While the following excerpt relates to performance reporting, the guide establishes equivalent expectations across an audit committee’s four functions set out by the Rule:

Consistent with the requirements on accountable authorities under the PGPA Act regarding records about performance (section 37), advice to the accountable authority from the audit committee should be documented in the form of a written statement of its view on the appropriateness of the accountable authority’s performance reporting. An audit committee’s charter should specify the content and level of detail expected in a written advice.

The audit committee should communicate their view to the accountable authority and not merely state that it does not know of anything that would indicate the accountable authority’s performance reporting for the entity is not appropriate. The statement adds value by providing comfort to the accountable authority that their performance reporting is appropriate, and by providing references and suggestions for systems and process improvement.

1.31 On the basis of the above, there is an expectation that audit committees document their conclusion in relation to the appropriateness of the accountable authority’s performance reporting. Such a statement would be strengthened by also documenting the steps taken to reach this conclusion, for example with reference to the types of activities suggested by the guidance from Finance.32

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.32 The PGPA Act commenced on 1 July 2014, and entities were required to present their first corporate plans and performance statements from 1 July 2015. July 2018 marked the commencement of the fourth year of Commonwealth entities’ implementation of the framework, and October 2018 the conclusion of the third performance measurement and reporting cycle.

1.33 As noted by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), the framework ‘seeks to improve public sector performance information to strengthen accountability’.33 Observations from previous audits of entities’ performance statements, and recommendations from the JCPAA, indicate the need for sustained attention in this area to meet this aim, particularly with regard to:

- the development of performance measures that are relevant, reliable and complete;

- the provision of meaningful information to the Parliament to demonstrate progress against an entity’s purpose and meet the requirements, and the objects, of the PGPA Act;

- consideration of an entity’s efficiency in meeting its purpose; and

- review by audit committees of their accountable authority’s performance reporting.

1.34 This performance audit is the ANAO’s third audit of entities’ progress in the implementation of the performance statements requirements under the PGPA Act. Given the time elapsed, entities should have fully embedded the principles of the framework into their organisational processes, to support the presentation of meaningful performance information to the Parliament and the public.

1.35 The ANAO’s continuing focus in this area is expected to assist in keeping the Parliament, the government, and the public informed on implementation of the framework and to provide insights to entities to encourage improved performance.

1.36 To date, the ANAO’s audits of performance statements have considered entities where the achievement of purposes were driven by a focus on program-delivery, and the use of quantitative measures was more prevalent. In contrast, the entities selected for this audit are intended to provide an opportunity to consider the performance measurement and reporting frameworks of entities whose activities are more focused on policy development, coordination and leadership. These types of activities typically generate more qualitative, than quantitative, information, and entities may, or may not be, taking advantage of the flexibility encouraged by the framework in the development of their own performance measurement and reporting frameworks in response.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.37 The objective of the audit was to continue to examine the progress of the implementation of the performance statements requirements under the PGPA Act and the PGPA Rule by the selected entities. The audit was also designed to:

- provide insights to entities more broadly, to encourage improved performance; and

- continue the development of the ANAO’s methodology to support the possible future implementation of annual audits of performance statements.

1.38 To form a view against the audit objective, the following high level criteria were adopted:

- entities complied with the requirements of the PGPA Act and PGPA Rule and, in doing so, met the objects of the PGPA Act;

- the performance criteria presented in the selected entities’ budget statements, corporate plans and performance statements were appropriate; and

- entities had effective supporting frameworks to develop, gather, assess, monitor, assure and report performance information.

1.39 The audit involved assessment of the appropriateness (relevance, reliability and completeness) of the performance criteria, and the completeness and accuracy (fair presentation) of reporting. This was completed for a subset, or all of the performance criteria presented by the selected entities in their 2017–18 Performance Statements.

1.40 The audit considered the performance criteria established by each of the selected entities to demonstrate progress against the following elements of their corporate plans:

- Attorney-General’s Department’s performance criteria for ‘Strategic Priority 3 — Justice’ and ‘Strategic Priority 5 — Rights’;

- Department of Education and Training’s performance criteria for ‘Outcome 1 — Quality early learning and schooling’;

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s performance criteria for ‘Priority Function 1: Promoting a stable and prosperous regional and global environment’ and ‘Priority Function 2: Improving market access for Australian goods and services, attracting foreign investment and supporting business’; and

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s performance criteria for all purposes.

1.41 The performance criteria considered for each entity are presented in Appendix 2.

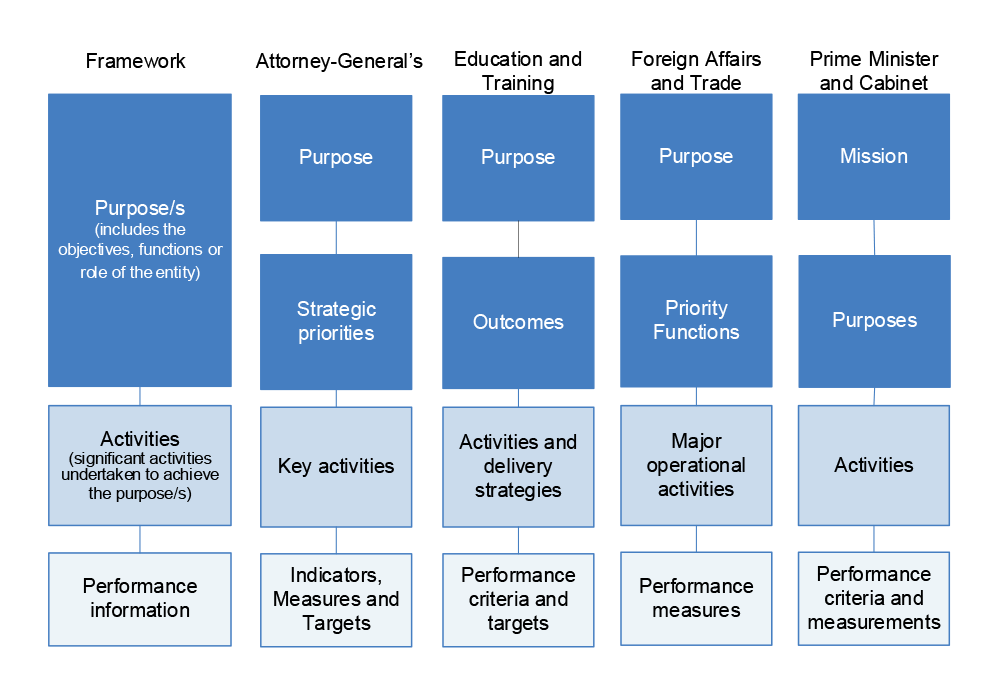

1.42 Under the PGPA Act and Rule, an entity’s purpose may be their objectives, functions or role. This has led to variability in the language used by entities when labelling elements of their corporate plans, as demonstrated in Figure 1.3, and reduces inter-entity comparability for readers. This may be an area where further consideration or guidance by Finance may assist in providing additional clarity across entity performance reporting.

Figure 1.3: Comparison of corporate plan elements

Source: ANAO analysis.

Audit methodology

1.43 The audit included reviewing:

- the selected entities’ 2017–18 PBS, Corporate Plans and Performance Statements;

- internal systems, processes, and procedures, including the governance and oversight put in place by the selected entities to support their development of the performance statements;

- records, and interviews of staff of the selected entities; and

- the selected entities’ 2018–19 PBS and Corporate Plans to identify any further opportunities for improvements to performance measurement and reporting that may be addressed in the 2018–19 Corporate Plans and/or Performance Statements.

1.44 The audit also included reviewing Finance’s role in whole-of-government administration of the framework.

1.45 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $585,000.

1.46 The team members for this audit were Jennifer Hutchinson, Kara Ball, Jillian Blow, Alicia Vaughan and Michael White.

2. Compliance with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013

Areas examined

This chapter considers whether the selected entities complied with the requirements of the PGPA Act, and accompanying PGPA Rule, in regard to the preparation and tabling of annual performance statements.

Conclusion

All of the entities met the requirement to prepare, and table in Parliament, performance statements under section 39 of the PGPA Act. The entities’ performance statements also demonstrated the principles of Plain English and clear design. However, the clear acquittal of results against performance criteria presented in the PBS, and the presentation of more meaningful analysis, are areas requiring improvement by the entities.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at entities improving the analysis presented in their performance statements to provide the Parliament and the public with more meaningful information.

The ANAO has also highlighted the importance of establishing a ‘clear read’ through the alignment of results in the performance statements, and the performance measures originally presented in an entity’s PBS and Corporate Plan. This includes drawing the users’ attention to, or clearly explaining, any instances where measures overlap and/or present the same or similar results.

Have the selected entities complied with the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and accompanying Rule?

All of the entities met the requirement to prepare and table performance statements under section 39 of the PGPA Act. Each entity’s performance statements also contained the required elements (statements, results and analysis) set out in section 16F of the PGPA Rule. However, AGD and DFAT’s performance statements did not clearly present results against all of the performance criteria presented in their 2017–18 PBSs. In addition, the analysis presented by all four entities requires improvement to meet the Rule, and provide meaningful information to support the Parliament and the public’s assessment of the entities’ performance.

2.1 Table 2.1 outlines the PGPA Act and Rule requirements for the presentation of annual performance statements. To determine whether entities met the requirements of the PGPA Act and Rule, the ANAO reviewed whether:

- the entities had prepared, and tabled in Parliament, performance statements in accordance with the PGPA Act and Rule; and

- the statements, results and analysis presented in those performance statements met the requirements of the PGPA Act and Rule.

2.2 The results of this assessment is summarised in Table 2.1, and the following sections.

Table 2.1: Compliance with PGPA Act and PGPA Rule requirements

|

Requirement |

AGD |

DFAT |

Education |

PM&C |

|

Section 39 of the PGPA Act |

||||

|

Subsection (1) |

||||

|

Prepare annual performance statements for the entity as soon as practicable after the end of each reporting period for the entity. Include a copy of the annual performance statements in the entity’s annual report that is tabled in the Parliament. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Subsection (2) |

||||

|

The annual performance statements must:

|

Requires improvement — refer to compliance with Section 16F of the PGPA Rule below. |

Requires improvement — refer to compliance with Section 16F of the PGPA Rule below. |

Requires improvement — refer to compliance with Section 16F of the PGPA Rule below. |

Requires improvement — refer to compliance with Section 16F of the PGPA Rule below. |

|

Section 16F of the PGPA Rule |

||||

|

Subsection (1) — Measuring and assessing entity’s performance |

||||

|

The accountable authority of the entity must measure and assess the entity’s performance in achieving the entity’s purposes in the reporting period in accordance with the method of measuring and assessing the entity’s performance in the reporting period that was set out in the entity’s corporate plan, and in any Portfolio Budget Statement, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statement or other portfolio estimates statement, that were prepared for the reporting period. |

Requires improvement — refer to Items 2 and 3 below. |

Requires improvement — refer to Items 2 and 3 below. |

Requires improvement — refer to Item 3 below. |

Requires improvement — refer to Item 3 below. |

|

Item 1: Statements A statement specifying the performance statements were prepared for subsection 39(1)(a) of the PGPA Act. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

A statement specifying the reporting period for which the performance statements are prepared. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

A statement that, in the opinion of the accountable authority of the entity, the performance statements: (i) accurately present the entity’s performance in the reporting period; and (ii) comply with subsection 39(2) of the Act. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Item 2: Results The results of the measurement and assessment referred to in subsection 16F(1) of PGPA Rule of the entity’s performance in the reporting period in achieving its purposes. |

Requires improvement |

Requires improvement |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Item 3: Analysis An analysis of the factors that may have contributed to the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes in the reporting period, including any changes to:

that may have had a significant impact on the entity’s performance in the reporting period. |

Requires improvement |

Requires improvement |

Requires improvement |

Requires improvement |

Source: ANAO analysis against PGPA Act and Rule requirements.

Preparation and tabling

2.3 Each of the selected entities complied with subsection 39(1) of the PGPA Act to prepare performance statements and include a copy in their tabled 2017–18 Annual Reports. Table 2.2 below presents a summary for each entity of the date the performance statements were approved by the accountable authority, and subsequently tabled in the Parliament.

Table 2.2: Approval and tabling of the selected entities’ performance statements

|

Entity |

Performance statements approved |

Annual report tabled in Parliament |

|

AGD |

23 August 2018 |

19 October 2018 |

|

DFAT |

15 September 2018 |

17 October 2018 |

|

Education |

20 September 2018 |

18 October 2018 |

|

PM&C |

3 September 2018 |

3 October 2018 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.4 Across the four entities, the time elapsed between the end of the reporting period (30 June 2018) and the approval of the performance statements by the accountable authority varied between two and three months. The entities’ annual reports, including the performance statements, were all tabled within five weeks of the accountable authority’s approval of the performance statements.

2.5 The PGPA Review included consideration of the timeliness of entity annual reporting and noted ‘Current arrangements for presenting annual reports to the Parliament do not ensure they receive adequate scrutiny by the Parliament.’ Three recommendations were made intended to improve the timeliness and scrutiny of annual reports, including Recommendation 30:

[Subject to the implementation of Recommendation 31] Annual reports should be presented to the Parliament on or before 30 September. This would ensure the Parliament has annual reports available before the Senate Supplementary Budget Estimates hearings. Annual reports should be presented to the responsible minister no later than seven days before this date.34

2.6 As demonstrated above, none of the selected entities tabled its annual report before 30 September 2018. Entities would benefit from considering how existing processes supporting the preparation of performance statements may be adapted to facilitate timelier reporting in the future. The processes supporting each entities’ preparation of the performance statements are discussed further in Chapter 4 of this report.

Statements

2.7 Each of the selected entities’ 2017–18 Performance Statements included the required statements by the accountable authority under subsection 16F(1) of the PGPA Rule. The selected entities also included an additional statement that the performance statements were ‘based on properly maintained records’. This reflects the requirement under section 37 of the PGPA Act for Commonwealth entities to keep records that properly record and explain the entity’s non-financial performance.

Results

2.8 As set out in Table 2.1, under subsection 16F(1) of the PGPA Rule, an entity must:

measure and assess the entity’s performance in achieving the entity’s purposes in the reporting period in accordance with the method of measuring and assessing the entity’s performance in the reporting period that was set out in the entity’s corporate plan, and in any Portfolio Budget Statement, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statement or other portfolio estimates statement, that were prepared for the reporting period.

2.9 The following section assesses whether the selected entities’ met this requirement by acquitting, or presenting results against, all of the performance measures originally presented in the PBS and corporate plan.35 Entities’ are also required to report in accordance with the methods set out in PBS and corporate plan. An assessment of these methods forms part of the assessment of the appropriateness of the selected entities’ performance criteria in Chapter 3.

2.10 The performance measures presented in the selected entities’ 2017–18 corporate plans were all reported in the 2017–18 performance statements. Education’s and PM&C’s performance statements also reported results against all of the performance measures presented in their 2017–18 PBS, in accordance with the PGPA Rule. In reviewing AGD’s and DFAT’s performance statements, it was unclear how the results presented addressed certain PBS measures36.

2.11 For example, two performance measures and accompanying targets37 were presented in AGD’s 2017–18 PBS (under Program 1.9: Royal Commissions) that were aligned to Strategic Priorities 1 and 3 in the corporate plan. These measures and targets were not presented in AGD’s performance statements. There was information related to Royal Commissions presented in a section of the performance statements, however there was no clear connection to the original measures and/or targets, affecting a user’s assessment of AGD’s performance in this instance.

2.12 The consistency and completeness of the presentation of performance criteria and targets across the PBS, corporate plan and performance statements is important to establish a clear read. Finance guidance notes that the Finance Secretary’s Direction ‘does not necessarily require entities to publish a line-by-line acquittal, however, the reader should be able to clearly discern the entity’s performance against all of the proposed measures.’38 It is important for entities to ensure the performance statements make clear how the results presented relate to measures originally presented in the corporate plan and PBS.

2.13 The accuracy of results presented against the measures in the entities’ performance statements were also reviewed and concluded to be materially correct, and supported by appropriate records. This aligns with the statements made by each accountable authority under subsection 39(1) of the PGPA Act that the performance statements ‘accurately present the entity’s performance in the reporting period’. Chapter 4 discusses the systems and processes supporting the entities’ performance statements, including an assessment of the results and accompanying records in more detail.

Analysis

2.14 Subsection 16F(1), Item 3: Analysis requires an entity to provide an analysis of factors that may have contributed to the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes. To fulfil this requirement, and the object of the PGPA Act to provide meaningful information, an entity’s analysis should establish for a reader the connection between:

- the results from individual performance measures;

- the internal or external environmental influences that affected those results; and

- how these form the basis for the entity’s assessment of its progress against the overarching purpose.

While each of the selected entities presented a form of analysis in their performance statements, there are opportunities for improvement by each to fully meet the PGPA Rule.

Attorney-General’s Department

2.15 AGD presents an analysis section in the performance statements under each strategic priority (the level below its purpose — see Figure 1.3). These sections provide an assessment of the department’s progress towards completing key activities set out in the corporate plan relevant to each strategic priority. This is supported by expanded discussion of the outputs and actions arising from those activities, however, there is no assessment by the department of how these contribute to an assessment of achievement of the strategic priority, or the overarching purpose.

2.16 Similarly, the analysis does not provide the reader with an understanding of how the different elements presented in the performance statements (KPIs, key activities, results and analysis) should be interpreted together to determine AGD’s overall performance. There is also an opportunity for the department to expand its analysis of specific results in the performance statements to assist a reader in understanding the factors affecting the department’s performance, and what is being done in response.

2.17 For example, under Strategic Priority, Australia’s ranking under Factor 4 of the Word Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index remained at position 13 of 113 countries. The performance statements include the following statement ‘The 2017 Index noted the greatest decline globally over the past 12 months is in Factor 4, with 71 of the 113 countries that are included having a lower rating. Australia’s ranking remains at 13 of 113 countries.’ However, it does not explain why the target (position 10) was not met, or provide the department’s view of what might have contributed to it. Expanding this analysis would improve the meaningfulness of the information being presented.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

2.18 DFAT presents an overview and analysis section in the performance statements for each priority function (the level below its purpose — see Figure 1.3). This section provides discussion and analysis of the department’s operating context and key risks, including outlining significant international issues and activities undertaken by the department. This type of analysis assists the reader to understand the rationale behind, and importance of, DFAT’s activities.

2.19 This could be improved by including analysis of how these issues impacted on DFAT’s performance, and outlining actions taken to address them. That is, rather than presenting information on circumstances and events that could impact performance, the reader would benefit from an explanation of if, and how, these did impact performance and how DFAT responded.

2.20 In addition, the analysis does not establish a sufficient connection between the results presented against each measure of ‘met’ or ‘partially met’, and the accompanying case studies. For example, under Priority Function 1 the performance criterion ‘Our ability to shape outcomes which reflect Australia’s interests, including through coalition building with international partners’ was rated as partially met. The case study notes that ‘Australia and Timor-Leste successfully concluded an agreement on maritime boundaries and resources development’, and ‘despite best efforts, the conciliation process was not able to secure an agreement between Australia, Timor-Leste and relevant companies on the best model for developing the Greater Sunrise Gas Fields’. In the absence of further discussion or analysis of what other activities or actions of the department undertook during the reporting period, beyond the Timor-Leste case study, the reader is left with limited information to determine whether the partially met rating is appropriate for the performance criterion.

2.21 Further, DFAT does not provide an overarching assessment of its progress against the priority function, or the department’s purpose. DFAT would benefit from making clear to a reader how the different sections of the performance statements (overview and analysis, and results) collectively demonstrate achievement of the department’s priority functions and overarching purpose.

Department of Education and Training

2.22 Education’s performance statements are structured to reflect its purpose ‘Maximising opportunity and prosperity through national leadership on education and training’, and two outcomes: ‘Outcome 1 Quality early learning and schooling’; and ‘Outcome 2 World-class tertiary education training and research’. Analysis, key performance results (corporate plan performance measures) and additional results (PBS measures) are presented for each Outcome in the performance statements.

2.23 The analysis presented for Outcome 1 is largely a summary of activities and positive results presented in the key performance results section, rather than an assessment of the department’s progress against the outcome itself. The analysis also does not address the only key performance result under Outcome 1 that was reported as less than ‘Achieved’ — ‘Greater proportion of students achieve at or above minimum standards for reading, writing and numeracy under the National Assessment Program.’39

2.24 The analysis presented in the performance statements also does not provide an assessment of the department’s overall progress against its purpose, on the basis of the measures and results presented across the two outcomes. Presenting this overarching assessment in the performance statements, in compliance with the PGPA Rule, would assist users to assess Education’s progress towards its purpose.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

2.25 PM&C’s performance statements are structured to reflect its three purposes, which the department notes ‘help to achieve our mission of advancing the wellbeing of all Australians’:

- Purpose 1: Supporting the Prime Minister, as the head of the Australian Government, the Cabinet and portfolio minsters;

- Purpose 2: Providing advice on major domestic policy, national security and international matters; and

- Purpose 3: Improving the lives of Indigenous Australians.

2.26 Corporate plan activities, KPIs, performance measurements and key results, including case studies, are presented under a combined section for Purposes 1 and 2 and labelled ‘Supporting and advising’. This is then followed by a section for PBS performance criteria and results relevant to the two purposes. The same structure is adopted for Purpose 3.

2.27 Preceding the purposes, PM&C also presents an ‘Analysis of performance against our purposes’ section which contains the following statement:

During 2017–18 PM&C generally performed effectively in delivering our three purposes. Independent surveys of stakeholders found that we provided quality advice across a broad range of policy areas; that we collaborated effectively with public and non-government stakeholders; and we provided effective services to the Cabinet.

2.28 This is accompanied by a section on the operating environment, highlighting the climate in which the department operated during the year, its response and the impact this had. An additional ‘Areas for improvement’ section outlines, for those activities or areas where the department’s survey results were less than expected, how the department intends to respond in the future. Establishing a more direct link between these two sections would enhance a users’ understanding of the factors influencing the department’s performance during the period. For example, the department notes a ‘spike’ in official visits and events stretched the department’s resourcing and capacity, however it doesn’t point to specific activities or results that were affected by this.

2.29 In addition, where PM&C relied on case studies as a form of measurement, there is no analysis in the performance statements to establish a connection to the results presented against each measure of ‘Achieved’. As noted above for DFAT, without this, a reader is unable to assess whether the reported result is appropriate.

2.30 The analysis presented in the performance statements also does not provide an assessment of the department’s overall progress against its mission, on the basis of the measures and results presented across the purposes. Presenting this overarching assessment in the performance statements, in compliance with the PGPA Rule, would assist users to form a judgement on PM&C’s overall progress.

Recommendation no.1

2.31 Entities improve the analysis presented in their performance statements to ensure a reader understands the connection between the results presented, the internal or external environmental influences that affected those results, and how these informed the entities’ assessment of progress against their purpose.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

2.32 Following feedback from the ANAO during this audit, proposed performance measures for inclusion in our 2018–22 Corporate Plan were reviewed to ensure clarity in the connection between our PBS and Corporate Plan. The department will continue to seek to improve the analysis presented in our annual performance statements as suggested.

Department of Education and Training response: Agreed.

2.33 The Department of Education and Training will address this recommendation in its 2018–19 annual performance statements.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

Did the selected entities’ annual performance statements fulfil other annual reporting requirements?

Each entity’s performance statements are structured to support a reader’s understanding of the content, demonstrating the characteristics of ‘plain English and clear design’ under the annual reporting requirements. However, as noted earlier, the need for clearer alignment between the results presented by entities in the performance statements and the original measures, and improving the quality of analysis remain areas for improvement.

2.34 The purpose of the performance framework is to enhance the transparency and accountability of the public sector.40 Finance guidance highlights the aim of the PGPA Act is to improve the line of sight between what is intended and what is delivered.41 To support this aim, sections 17AC, 17BD and 28D of the PGPA Act include provisions for ‘Plain English and clear design’, in relation to commonwealth entities’ and companies’ annual reports, including:

- annual reports must be prepared having regard to the interests of the Parliament and any other persons who are interested in the annual report; and

- requiring information in the annual report to be relevant, reliable, concise, understandable and balanced, including through clear design and defining technical terms.

These requirements provide for clear interpretation of the annual report, including the performance statements, by users.

2.35 Overall, all four entities’ performance statements were structured to support a reader’s understanding of the content. In particular, Education’s presentation of its results within the performance statements provides readers with a clear understanding of a measure’s information source, limitations and the relevant PBS program alignment to assist informed decision-making. However, as noted earlier, the need for clearer alignment between the results presented by entities in the performance statements and the original measures, and improving the quality of analysis remain areas for improvement.42

2.36 As noted by Finance guidance, it is important to reinforce the connection between the corporate plan, PBS and performance statements to enable a ‘clear read’ of the three documents. Each entity adopted a slightly different approach in meeting this aim. Commonly, each of the four entities set out their performance statements in the same structure as the corporate plan, reinforcing the connection between the documents. The effectiveness of the entities’ approaches to establishing this same connection between the performance statements and the PBS varied.

2.37 As discussed in paragraph 2.10, it was not clear how some of the performance criteria presented in AGD and DFAT’s 2017–18 PBS were addressed in the performance statements. This is despite both entities providing mapping demonstrating the alignment between the PBS programs and corporate plan strategic priorities/priority functions in the performance statements. This highlights the importance of an entity providing clear signs to a reader of how specific measures have been transposed from the PBS and corporate plan to the performance statements.

2.38 PM&C and Education both present the performance measures and accompanying results from their PBSs separately in the performance statements to those in the corporate plans. This assists a reader confirm the completeness of the actual results in the performance statements compared to the expectations set by the PBS and corporate plan measures. However, there are opportunities for both departments to better integrate the PBS performance measure results with those from the corporate plan, particularly where the PBS performance measures appeared to overlap with the results already presented against the corporate plan measures.

2.39 For example, the following results were repeated in two different sections of Education’s performance statements due to the similarity of the PBS and Corporate Plan measures:

The Child Care Subsidy System (CCSS) went live on 2 July 2018. 1.02 million families completed their Child Care Subsidy assessment. Of 6,053 existing child care providers, 6,040(12,732 of 12,745) successfully transition to the new arrangements.43

2.40 Neither department drew attention to, nor attempted to explain, where an overlap occurred. Given the framework intention is for a clear read across the PBS, corporate plan and performance statements, where measures overlap or present the same, or similar, results, introducing and/or explaining this to a reader would assist in meeting this aim.

3. Measurement and reporting of performance

Areas examined

This chapter considers whether the selected entities’ 2017–18 Corporate Plans supported appropriate performance measurement and reporting in the annual performance statements. It also summarises improvements made by the entities to their planned 2018–19 performance measurement and reporting.

Conclusion

The selected entities’ measurement and reporting of their performance through corporate plans and performance statements has generally improved. However, the reliability and completeness of performance criteria remain areas requiring improvement by all entities. While some improvements are already evident in the selected entities’ 2018–19 Corporate Plans, further work is necessary to establish the basis required to provide meaningful information to the Parliament and the public about the entities’ progress in achievement of their purposes.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at entities improving the reliability of performance measures and developing measures that provide the Parliament and public with an understanding of the entities’ efficiency in delivering their purpose/s.

The ANAO has also suggested improvements to:

- activities presented in corporate plans, through the use of more specific language to clearly describe the actions to be undertaken by the entity, and focus on those most relevant to the Parliament and the public;

- entities’ alignment of information presented in the PBSs, corporate plans and performance statements to establish a clear read between each; and

- the Finance Secretary’s Direction, to provide an improved basis to establish the line of sight between financial and non-financial performance as set out in entities’ PBS and corporate plans.

Did the selected entities’ corporate plans support performance measurement and reporting in the annual performance statements?

AGD’s corporate plan provides a clear basis to support its performance measurement and reporting by clearly expressing its purpose, and significant activities. DFAT, Education and PM&C could each improve their corporate plans by more clearly describing the activities to be undertaken to achieve their purpose/s. PM&C should relabel its mission as its purpose, and the stated purposes as objectives or priorities, to make clear to a user the impact intended to be measured. Establishing a ‘clear read’ between the PBS and corporate plan is also an area where AGD, DFAT and PM&C should improve, to support performance measurement and reporting in the performance statements.

3.1 As demonstrated in Figure 1.1, an entity’s corporate plan, alongside the PBS, sets out an entity’s planned performance through the description of purposes, activities and performance criteria. The corporate plan is intended to be an entity’s primary planning document, and the key source of information for the Parliament and the public to form an expectation of an entity’s performance.

3.2 This expectation may then be compared to the actual performance set out by an entity in its performance statements through results and accompanying analysis. The Parliament and the public use this comparison to assess the extent to which the entity has met that expectation. As a result, it is important for an entity’s corporate plan to provide a clear basis to not only support an entity’s assessment of its performance, but also the Parliament’s and the public’s.

Purpose

3.3 Section 16E of the PGPA Rule requires an entity’s corporate plan to state the entity’s purpose/s over the next four years. The PGPA Act defines purpose/s as including the objectives, functions or role of an entity. The aim of the purpose/s statement is to give context to the significant activities that the entity will pursue over that period, and should be stated in a relevant and concise manner. Finance guidance notes that:

Well-expressed purpose statements make it clear who benefits from an entity’s activities, how they benefit and what is achieved when an entity successfully delivers its purposes. Essentially, purposes describe the value an entity seeks to create or preserve.

3.4 The purpose presented in the corporate plans of AGD, Education and DFAT demonstrate the required elements of a ‘well-expressed’ purpose statement. Each purpose was readily identifiable, makes clear who will benefit from the entities’ respective activities, how the entities will deliver that benefit and the impact intended to be achieved in delivery against their purposes. PM&C’s purposes require improvement to meet the characteristics set out by Finance guidance, as described below.

3.5 Education and PM&C’s 2016–17 Corporate Plans were both included in Auditor-General Report No.54 2016–17 Corporate Planning in the Australian Public Sector 2016–17. As part of this audit, the ANAO observed that Education’s purpose could be made more readily identifiable, and PM&C’s purposes were expressed as actions or activities rather than as an outcome or result to be achieved.44

3.6 When comparing Education’s 2016–17 and 2017–18 corporate plans, the department replaced its vision and mission with a purpose statement. By removing the vision and mission, the purpose statement can be easily identified by a user as the definitive expression of the department’s intended purpose. This was also supported by an explanatory statement which assists to further describe who will benefit, and how the benefit is intended to be delivered by the department through achievement of its purpose. It also expands on the department’s intended impact, leading to an improved purpose statement, and addressing the observations made in the report.