Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Identifying and Reducing the Tax Gap for Individuals Not in Business

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- In its 2021–22 annual report, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) estimated that the overall net tax gap for the Australian tax and superannuation system was $33.4 billion for 2019–20.

- The individuals not in business tax gap is the second largest gap in dollar terms calculated by the ATO behind the small business tax gap.

Key facts

- The population of taxpayers considered individuals not in business is over 11.5 million.

- The ATO conducts a Random Enquiry Program on a representative sample of this population and extrapolates the results to calculate the tax gap estimate.

- Work related expense claims are the biggest contributor to the individuals tax gap.

- Compliance strategies are used by the ATO to maintain or reduce the tax gap.

What did we find?

- The ATO is largely effective at identifying and reducing the tax gap for individuals not in business.

- The ATO is largely effective at identifying and measuring the tax gap for individuals not in business.

- The ATO implements risk-based compliance strategies to reduce the individuals not in business tax gap.

- The ATO assesses the effectiveness of its compliance strategies to reduce the tax gap in an effective manner.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations to the ATO relating to: transparency of its tax gap methodology, transparency and confidence in reliability assessments, and the use of targets and benchmarks to better understand the performance of compliance strategies.

- The ATO agreed to the recommendations.

$9.03bn

The estimated tax gap for individuals not in business for 2019–20. The ATO estimates that it collects 94.4 per cent of theoretical tax owing.

545

Number of random audits undertaken annually. These are collated into two or three year rolling bundles of up to 1635 random audits.

9 out of 10

Number of taxpayers with rental property income determined by the ATO to be claiming incorrect deductions in income tax returns.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is responsible for the effective management of Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems. This includes responsibility for achieving confidence in these systems by ‘helping people understand their rights and obligations, improving ease of compliance and access to benefits, and managing non-compliance with the law.’1

2. The ATO’s purpose is to contribute to the economic and social wellbeing of Australians by fostering willing participation in the tax, superannuation and registry systems. The ATO’s Corporate Plan 2022–23 identifies the tax gap as part of a strategic objective: ‘We build community confidence by sustainably reducing the tax gap and providing assurance across the tax, superannuation and registry systems.’2

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. In its 2021–22 annual report, the ATO estimated that the overall net tax gap3 for the Australian tax and superannuation system was $33.4 billion for 2019–20. Within this total, the estimated net tax gap for the taxpayer population of ‘individuals not in business’ was the second largest gap in dollar terms — $9 billion for 2019–204 meaning that for this gap, the ATO collected around 94.4 per cent of the tax revenue it would have collected if all taxpayers were fully compliant with tax law. This audit will provide Parliament with assurance that the ATO is appropriately managing the tax gap for individuals not in business.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s arrangements for identifying and reducing the income tax gap for individuals not in business.

5. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Does the ATO use appropriate methods for identifying the tax gap?

- Has the ATO implemented risk-based compliance strategies for reducing the tax gap?

- Does the ATO assess the effectiveness of its compliance strategies for reducing the tax gap?

Conclusion

6. The ATO is largely effective at identifying and reducing the tax gap for individuals not in business.

7. The ATO is largely effective at developing, implementing, and communicating the tax gap methodology for individuals not in business. The ATO undertook an appropriate process to develop a fit-for-purpose methodology, though it did not fully integrate expert advice on sample size and does not have a mechanism to review whether the sample size remains sufficient over time. The ATO has effectively implemented its methodology. The ATO communicates information on its tax gap methodology through its website, though transparency on the methodology could be improved. The ATO publishes a reliability assessment along with the tax gap estimate, though it does not document the process undertaken to develop this assessment. Doing this will help to drive continuous improvement.

8. The ATO has sound processes for identifying and developing compliance strategies to address risks to the individuals not in business tax gap, though inconsistent application of ATO guidance undermines the effective implementation of these strategies. The tax gap measurement process and estimate inform business and enterprise level risks to the individuals not in business tax gap. Performance of the tax system for individuals not in business is monitored, and compliance strategies are developed if necessary. ATO guidance to implement compliance strategies is applied inconsistently, and as compliance strategies do not contain specific targets, the ATO is unable to determine the extent to which compliance strategies contribute to reducing the tax gap for individuals not in business.

9. The ATO is largely effective in assessing compliance strategies for reducing the tax gap. Data and intelligence used to assess effectiveness is relevant, and the use of data for review purposes is embedded during compliance strategy planning via the use of randomised control trials. ATO guidelines encourage timelines for assessment to be developed. While this generally occurs, testing of selected compliance strategies indicates that the ATO has been inconsistent in meeting the timelines set. The ATO internally reports on the effectiveness of individual compliance strategies through Evaluation and Review reports and provides overviews of these meetings upwards. Actionable insights are shared within the ATO.

Supporting findings

Identifying and measuring the tax gap

10. In designing its methodology, the ATO took into account best practice and the methodologies of other jurisdictions, and sought and incorporated expert advice across all areas except sample size. The methodology was assessed and endorsed by an Expert Panel. Procedures to monitor developments in the field of tax gap estimation for individuals not in business are in place. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.30)

11. The ATO has implemented its methodology to measure the tax gap for individuals not in business as set out in its guidance. Review and quality assurance processes are fit-for-purpose, and the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business is appropriately endorsed. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.68)

12. The tax gap methodology is generally well communicated. A summarised version of the methodology for the individuals not in business tax gap is published on the ATO website, though the ATO could improve transparency by publishing its Technical Guide in full. The ATO publishes an assessment of the reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business to indicate the ATO’s level of confidence in the accuracy of the estimate. The ATO has not recorded the processes or outcomes of meetings held to establish reliability assessments since estimation of the tax gap for individuals not in business commenced. (See paragraphs 2.69 to 2.88)

Implementing risk-based compliance strategies to reduce the tax gap

13. The ATO has sound processes for identifying and prioritising risks to the individuals not in business tax gap at the business and enterprise level. Procedures governing the operation of the ATO’s risk management framework are comprehensive and well-articulated. The findings from the tax gap measurement process and the estimate inform the risks that relate to the tax gap for individuals not in business. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.22)

14. The ATO develops compliance strategies that target specific groups of taxpayers to address business and enterprise level risks to the tax gap for individuals not in business. Data from lodged tax returns are assessed against established tolerances, and when performance moves out of tolerance, the ATO is prompted to consider whether a compliance strategy is required. (See paragraphs 3.23 to 3.31)

15. If a compliance strategy is required, the ATO develops a program logic which identifies the key elements of the compliance strategy. Guidance to prepare a compliance strategy is comprehensive, and they are largely developed in accordance with ATO guidance. (See paragraphs 3.32 to 3.47)

16. While the ATO has guidance to implement compliance strategies, this guidance is applied inconsistently. ATO guidance also requires the intended outcomes of a program logic to be reflected in a compliance strategy’s Measurement and Evaluation Plan. An examination of selected compliance strategies found that this occurred inconsistently. While the ATO is able to assess the results of a compliance strategy, it is unable to determine the extent to which a compliance strategy is successful. Targets and benchmarks are not articulated in Measurement and Evaluation Plans. (See paragraphs 3.48 to 3.77)

Assessing compliance strategies for reducing the tax gap

17. The ATO conducts randomised control trials to analyse the effectiveness of compliance strategies where appropriate. These are supported by a range of relevant data and intelligence sources to allow for comparison of target populations and control groups. (See paragraphs 4.4 to 4.11)

18. ATO guidance does not mandate specific timeframes for the assessment of individual compliance strategies for individuals not in business, but staff are encouraged to consider how often an assessment will need to be conducted when designing a Measurement and Evaluation Plan. An examination of selected compliance strategies indicated that where a Measurement and Evaluation Plan had been developed, timeframes for assessment had been established, but were inconsistently met. (See paragraphs 4.12 to 4.31)

19. The ATO monitors the performance of compliance strategies via a dashboard, reporting, and fortnightly meetings. The outcomes of fortnightly meetings are not documented, meaning the ATO may not be able to monitor the progress of agenda items outlined in reporting. (See paragraphs 4.32 to 4.43)

20. The ATO reports on the effectiveness of individual compliance strategies to reduce or maintain the individuals tax gap through evaluation and review reports. While endorsement of these documents is required, evidence of endorsement is not always included in or attached to the reports. The findings of evaluation and review reports are communicated through a risk call-over process, and the outcomes of this are then transmitted internally. The ATO also includes corporate revenue measures in its Annual Report. (See paragraphs 4.44 to 4.60)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.76

The Australian Taxation Office publish the Individuals Not In Business Tax Gap Technical Guide in full to enable transparency as to how the tax gap for individuals not in business is estimated.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.85

The Australian Taxation Office document the process of assessing reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business to support transparency and confidence in the accuracy of the estimate.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.77

The Australian Taxation Office set specific measurable targets and develop benchmarks for use in Measurement and Evaluation Plans. Associated guidance should reflect the need to set targets and use benchmarks to enhance the ATO’s understanding of the effects of compliance strategies intended to reduce the tax gap for individuals not in business.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

Summary of Australian Taxation Office response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to the ATO. The full response is included at Appendix 1. The summary response is reproduced below.

We are extremely proud of our individuals not in business tax gap methodology and random enquiry program, which is recognised internationally as best practice. The estimate is published in the Commissioner’s Annual Report, and our experience shared through the OECD Tax Gap Community of Practice. Our methodology has been effectively applied to administered programs including JobKeeper. We believe there is significant value in other agencies adopting a similar approach, particularly if performance metrics are based on compliance yield which is a good proxy for short term activity, but not necessarily for sustained system health. By contrast, ‘gap’ style methodologies attempt to estimate system health and support a longer-term stewardship approach.

The individuals not in business market is a focus for us given its size and complexity. Tax gap analysis is an evidence-based measure of the risk behaviours driving the gap. Understanding those drivers is an important input to strategy development, as are other measures such as total revenue effects, and evaluation of preventative actions.

As we move beyond tax gap thinking, our focus is shifting to preventative activities that support compliance upfront. Our new evaluation framework provides better measures of these strategies and their sustained effect on future willing participation.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is responsible for the effective management of Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems. This includes responsibility for achieving confidence in these systems by ‘helping people understand their rights and obligations, improving ease of compliance and access to benefits, and managing non-compliance with the law.’5

1.2 One of the ATO’s strategic objectives is to provide the community with confidence in its administration of the tax and superannuation systems that support the collection of the right tax at the right time, for the wellbeing of all Australians.6 The ATO’s Corporate Plan 2022–23 identifies the tax gap as part of a strategic objective: ‘We build community confidence by sustainably reducing the tax gap and providing assurance across the tax, superannuation and registry systems.’7

The tax gap

1.3 The ATO defines the tax gap as ‘an estimate of the difference between the amount of tax the ATO collects and what we would have collected if every taxpayer was fully compliant with tax law.’8

1.4 The purpose of tax gap estimation is to measure what is ‘not directly observable’9 — revenue not collected due to taxpayers misreporting their true tax position:

- Due to misunderstanding their obligations;

- by choice; or

- by taking a tax position that differs from the ATO’s view of the law.10

1.5 Prior to 2012, there was no systematic program of tax gap estimation for any of the taxes administered by the ATO other than for the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the Luxury Car Tax. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit11 and the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue12 encouraged the ATO to publish its tax gap analysis on GST collections, and to continue to examine potential methodologies for tax gap estimates. The ATO published its first gap estimates (for the GST and Luxury Car Tax) in 2012.

1.6 The ATO currently calculates 21 tax gaps across three different groups: six transaction-based tax gaps (such as the GST or fuel excise); six administered program gaps (such as fuel tax credits or JobKeeper); and nine income-based tax gaps (such as those for individuals not in business, and large corporate groups).13 Figure 1.1 depicts the estimated total tax gap for 2019–20.

Figure 1.1: Estimated total tax gap for 2019–20

Source: ATO documentation.

1.7 The ATO defines individuals not in business as ‘Individuals with no business connections (including Wealthy Australians) but may have passive income (such as interest, dividends) and are not connected to a high wealth group with over $50 million in net assets.’

1.8 Figure 1.2 illustrates the way the ATO defines key elements of the tax gap estimate.

Figure 1.2: The tax gap frameworka

Note a: This graph is intended to explain concepts, not report results, and is not to scale.

Note b: Accounts for errors on tax returns that are not identified through the Random Enquiry Program (see paragraph 2.62).

Note c: Represents the unreported tax liability estimated through the Random Enquiry Program plus an estimate for people outside the system, after subtracting the value of amendments.

Note d: Tax liabilities that the Commissioner has assessed to be not legally recoverable or not economical to pursue.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

1.9 The tax gap estimate for individuals not in business has been calculated from the 2013–14 to the 2019–20 tax years. Table 1.1 outlines the ATO’s tax gap estimate for individuals not in business from 2014–15 to 2019–20. The ATO has an internal target of a net tax gap of 4.5 per cent. The ATO advised that this target was an aspirational internal target, and that reaching this target would depend on technological advances, environmental and economic factors, and policy changes.

Table 1.1: Tax gap estimates for individuals not in business

|

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|

Population |

10,551,187 |

10,844,682 |

11,122,167 |

11,306,048 |

11,447,818 |

11,552,468 |

|

|

$m |

$m |

$m |

$m |

$m |

$m |

|

Tax paid voluntarily |

118,375 |

125,343 |

129,531 |

140,138 |

143,758 |

150,855 |

|

+ Amendmentsa |

809 |

751 |

895 |

711 |

575 |

643 |

|

= Total tax paid |

119,184 |

126,095 |

130,426 |

140,849 |

144,360 |

151,498 |

|

+ Non-pursuable debtb |

161 |

177 |

194 |

220 |

202 |

202 |

|

= Tax reported |

119,345 |

126,272 |

130,621 |

141,069 |

144,562 |

151,700 |

|

+ Unreported taxc |

6,165 |

6,651 |

6,625 |

6,950 |

6,306 |

6,319 |

|

+ Non-detectiond |

1,845 |

1,960 |

2,165 |

2,485 |

2,529 |

2,509 |

|

= Theoretical tax |

127,355 |

134,883 |

139,411 |

150,504 |

153,396 |

160,528 |

|

Gross tax gape |

8,980 |

9,539 |

9,880 |

10,366 |

9,611 |

9,673 |

|

Net tax gapf |

8,171 |

8,788 |

8,984 |

9,655 |

9,036 |

9,030 |

|

Gross tax gap (%) |

7.1% |

7.1% |

7.1% |

6.9% |

6.3% |

6.0% |

|

Net tax gap (%) |

6.4% |

6.5% |

6.4% |

6.4% |

5.9% |

5.6% |

Note a: Amounts attributable to ATO compliance work.

Note b: Tax liabilities that the Commissioner has assessed to be not legally recoverable or not economical to pursue.

Note c: Represents the unreported tax liability estimated through the Random Enquiry Program plus an estimate for people outside the system, after subtracting the value of amendments.

Note d: Accounts for errors on tax returns that are not identified through the Random Enquiry Program (see paragraph 2.62).

Note e: Theoretical tax minus tax paid voluntarily.

Note f: Theoretical tax minus total tax paid.

Source: ATO documentation.

Previous audits and review

1.10 Auditor-General Report No. 36 1998–99 Pay As You Earn Taxation – Administration of Employer Responsibilities14 observed that the ATO had identified an area for improvement that, ‘sound methods are required to estimate the potential PAYE tax gap.’ (For more information on how this matter has been addressed see from paragraph 2.33)

1.11 Auditor-General Report No. 30 2005–06 The ATO’s Strategies to Address the Cash Economy15 noted that, at the time, the ATO did not attempt to calculate the tax gap attributed to undeclared cash transactions. (For more information on how this matter has been addressed see from paragraph 2.63)

1.12 Auditor-General Report No. 39 2013–14 Compliance Effectiveness Methodology16 examined the ATO’s Compliance Effectiveness Methodology, a measure that sought to optimise voluntary compliance. The audit report suggested top-down measurement of the effectiveness of collection of payable revenue could be accompanied by a bottom-up approach to form a high-level view of ATO effectiveness. The ATO’s approach to measuring the entire tax gap estimate combines both top-down17 and bottom-up18 approaches19, with the individuals tax gap being calculated by a bottom-up methodology.

1.13 Auditor-General Report No. 27 2015–16 Strategies and Activities to Address the Cash and Hidden Economy20 noted that the ATO did not have a robust estimate of the taxation revenue foregone from the cash economy population and that publication of a robust estimate of the revenue at risk from the cash economy would contribute to increased transparency and enable the estimate to become a performance indicator for management of the cash economy risk over time. Further, the report stated that tax gap analysis could be used to measure the impact of activities on the cash economy, and to establish strategies and activities to address the cash economy. (For more information on how this matter has been addressed see from paragraph 2.63)

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.14 In its 2021–22 annual report, the ATO estimated that the overall net tax gap21 for the Australian tax and superannuation system was $33.4 billion for 2019–20. Within this total, the estimated net tax gap for the taxpayer population of ‘Individuals not in business’ was the second largest gap in dollar terms — $9 billion for 2019–2022, meaning that for this gap, the ATO collected around 94.4 per cent of the tax revenue it would have collected if all taxpayers were fully compliant with tax law. This audit will provide Parliament with assurance that the ATO is appropriately managing the tax gap for individuals not in business.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.15 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s arrangements for identifying and reducing the income tax gap for individuals not in business.

1.16 The audit focused on the ATO’s calculation of the 2018–19 income tax gap for individuals not in business estimate. On 31 October 2022, the ATO released its income tax gap for individuals not in business estimate for 2019–20. Further comment on the 2019–20 estimate process is in paragraph 2.38.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Does the ATO use appropriate methods for identifying the tax gap?

- Has the ATO implemented risk-based compliance strategies for reducing the tax gap?

- Does the ATO assess the effectiveness of its compliance strategies for reducing the tax gap?

Audit methodology

1.18 The audit methodology included:

- review of ATO documentation such as strategies, plans, risk documents, meeting papers and minutes, reporting and internal briefings;

- meetings with ATO officers; and

- detailed technical walkthroughs of processes and procedures with ATO officers.

1.19 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $609,949.

1.20 The team members for this audit were Shane Armstrong, Connor McGlynn, Ella Young, Ben Thomson, Amanda Reynolds, Molly Wu, Nathan Singlachar, and David Tellis.

2. Identifying and measuring the tax gap

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) developed, implements and communicates its methodology for identifying the tax gap for individuals not in business.

Conclusion

The ATO is largely effective at developing, implementing, and communicating the tax gap methodology for individuals not in business. The ATO undertook an appropriate process to develop a fit-for-purpose methodology, though it did not fully integrate expert advice on sample size and does not have a mechanism to review whether the sample size remains sufficient over time. The ATO has effectively implemented its methodology. The ATO communicates information on its tax gap methodology through its website, though transparency on the methodology could be improved. The ATO publishes a reliability assessment along with the tax gap estimate, though it does not document the process undertaken to develop this assessment. Doing this will help to drive continuous improvement.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations: that the ATO publish the Individuals Not In Business Tax Gap Technical Guide in full to enable transparency as to how the tax gap for individuals not in business is measured, and that the ATO document the process of assessing reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business to support transparency and confidence in the accuracy of the estimate.

The ANAO also made two suggestions to the ATO: that it consider whether the sample size for the Random Enquiry Program remains fit-for-purpose given increases in the population of individuals not in business, and that the ATO consider if its tax gap methodology could be enhanced by considering elements of a 2021 International Monetary Fund guide on personal income tax gap estimation.

2.1 The ATO’s Corporate Plan 2022–23 identifies the tax gap as part of a strategic objective: ‘We build community confidence by sustainably reducing the tax gap and providing assurance across the tax, superannuation and registry systems.’23 To achieve this, the ATO sought to design and implement a methodology to reliably and accurately estimate the tax gap for individuals not in business. An effective methodology should be well communicated to increase transparency24 and improve perceived reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business.

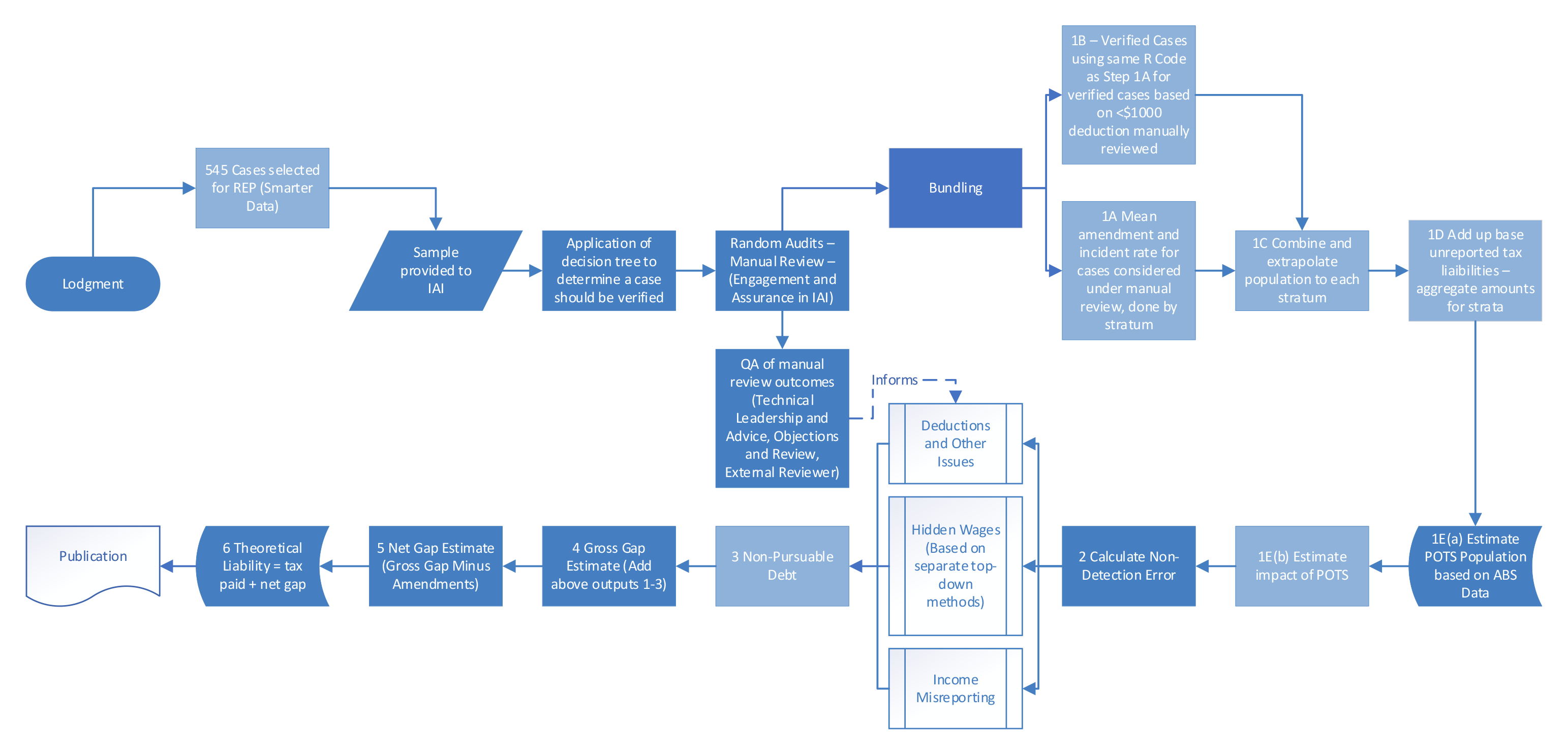

2.2 The ATO describes its overall methodology for estimating the individuals not in business tax gap in the Individuals Not in Business Tax Gap Technical Guide (the Technical Guide), an internal document developed and updated annually by the ATO’s Client Engagement Group Services business line. A summary of the ATO’s full methodology is at Appendix 3. In brief, it involves:

- a Random Enquiry Program (REP), which entails selecting a random sample of tax returns from individuals not in business, verifying the returns through a data driven process or manually reviewing them to identify and adjust errors, and extrapolating the incidence of non-compliance and the mean value of adjustments across the wider individuals not in business population;

- processes to estimate the impact of factors not measurable through the REP, namely the impact of non-pursuable debt, of non-registrants or long-term non-lodgers, and of non-detection due to income misreporting, hidden wages and other issues; and

- calculations using the outputs of the above steps and other figures to arrive at the tax gap estimate (gross and net) and theoretical tax liability.

Is the ATO’s tax gap methodology well designed?

In designing its methodology, the ATO took into account best practice and the methodologies of other jurisdictions, and sought and incorporated expert advice across all areas except sample size. The methodology was assessed and endorsed by an Expert Panel. Procedures to monitor developments in the field of tax gap estimation for individuals not in business are in place.

Expert advice and methodology coverage

2.3 To establish a methodology to calculate the tax gap for individuals not in business (the individuals tax gap), the ATO conducted external consultation between July 2014 and September 2015 (see Table 2.1) which addressed the measurement of multiple tax gaps. Examining the individuals tax gap as part of a broader process enabled the ATO to engage with a range of international experts in the field.

2.4 At this time, there was no single standard or better practice guide provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for the ATO to use as a model to develop its tax gap methodology.

2.5 An IMF report, United Kingdom: Technical Assistance Report – Assessment of HMRC’s Tax Gap Analysis25, published in 2013 informed the ATO’s thinking during the design process. In 2021, six years after the ATO had developed and implemented its methodology, the IMF published The Revenue Administration Gap Analysis Program – An Analytical Framework for Personal Income Tax Gap Estimation, a technical manual which constituted a better practice guide. The ANAO analysed whether the ATO’s methodology was consistent with this guide. Further information on this analysis is available at paragraph 2.27.

Table 2.1: External consultation process

|

External group |

Number of meetings |

Individuals tax gap discussed |

|

Tax Gap Advisory Panel |

5 |

4 |

|

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) |

4 |

4 |

|

US-based expert |

2 |

1 |

|

Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) (UK revenue agency) |

1 |

1 |

|

Internal Revenue Service (IRS) (US revenue agency) |

1 |

1 |

|

The Treasury |

1 |

0a |

|

Intra-Government Group (ABS, ANAO, Inspector-General of Taxation, Department of Human Services) |

1 |

1 |

Note a: The ATO advised that its meeting with Treasury covered only the large corporate tax gap.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

2.6 The ATO also established a Tax Gap Advisory Panel (the Advisory Panel) in March 2014 consisting of three experts in the field.26 The Advisory Panel’s purpose was to consider whether methodologies could be relied upon to produce a robust tax gap estimate, and were likely to be broadly accepted.

2.7 The members of the Advisory Panel later became members of the Tax Gap Expert Panel (the Expert Panel), which first met in its new capacity in November 2016 to provide further support to the ATO once the methodology had been established.27 The role and continued function of the Expert Panel are considered from paragraph 2.65.

2.8 Between April and May 2015, the ATO engaged ‘the services of the ABS to advise on sample design’. The purpose of the procurement was to obtain ‘advice on sampling plan design – stratification dimensions (assumptions), extrapolation advice and calculation. Advice on sample size options and trade-offs. Explanation of reasons for any variation with international experience.’

2.9 The ATO also engaged the services of a US-based economics and statistics consultant, to conduct external peer review during the consultation process.

2.10 Table 2.2 outlines the aspects of the tax gap methodology about which the ATO engaged with external experts. The ATO covered each of the elements, ensuring adequate coverage of potential areas of contention.

Table 2.2: External consultation analysis

|

External Group |

Sampling |

Stratification |

Sample Size |

Reporting as point or range |

Public reporting |

|

Tax Gap Advisory Panel |

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Australian Bureau of Statistics |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

|

US-based expert |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

HMRC (UK revenue agency) |

|

|

|

|

✔ |

|

Intra-Government Group (ABS, ANAO, Inspector-General of Taxation, Department of Human Services) |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.11 The ATO initially considered a potential sample size of 5000 random audits (covering both individuals and small business) over a period of four years.

2.12 Three of the four meetings with the ABS considered the issue. The ABS stated that 1250 audits annually for a total of 5000 over four years ‘sounded too low a number’. The ATO advised that a sample size of 2500 would constitute a snapshot of the overall health of the system, with a sample size of 5000 constituting an indicator of broad compliance movements over time. The US-based expert advised that a sample of 1250 random audits per year would not provide a good precision dollar point range, but would provide a reasonable estimate of rates of non-compliance.

2.13 At its meeting on 30 September 2015, the ATO Executive endorsed a pilot random enquiry program to review individual and small and medium business income tax returns.

2.14 The ATO settled on a three-year bundled sample of 1635 random audits (545 per year) as its methodology to form the basis of the annual tax gap estimate. The ATO stated in October 2022 that its sample size ‘[enables] the ATO to conduct a statistically reasonable sample size while balancing the broader Individuals compliance program’, and that ‘this was based on the original intended target of over 2000 random audits over a four year observation window.’ The purpose of bundling was to ‘increase the sample size’, and ‘assist in reducing the confidence interval on the estimate without the need for a larger annual sample.’

2.15 The ATO stated in its Technical Guide that the Expert Panel had:

highlighted that this bundling also causes an averaging effect creating a tension between how much is bundled and the need for insights on the trend. Given this advice, we have arrived at a three year bundling approach to try and minimise the averaging effect.

2.16 Expert Panel Minutes indicate that the Expert Panel was comfortable with this approach, with an action item generated to directly address the terminology around bundling. There is no evidence that sample size has been revaluated by the ATO since the methodology was established.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.17 The ATO may wish to consider developing a mechanism to review whether the sample size for the Random Enquiry Program remains fit-for-purpose given increases in the population of individuals not in business. |

2.18 Stratification28 of a sample was also recommended by the US-based expert, who stated that the ATO needed to consider how it sampled and areas to oversample, recommending that it would be best for the ATO to oversample in higher risk and higher impact areas using stratified sampling techniques.

2.19 In opting to oversample the rental tax strata by 10 per cent and undersample the zero tax strata by 10 per cent, the ATO stated in June 2022 that this: ‘was a judgement call based on the principle of over/undersampling based on where the tax gap is likely to manifest.’

2.20 The Expert Panel was briefed on sample design including the oversampling and undersampling of certain strata at meetings in September and November 2016. While the Expert Panel endorsed the individuals not in business tax gap estimate in February 2018 (which included sample size information), there is no evidence that the Expert Panel explicitly endorsed the ATO’s sampling approach in any of its meetings.

2.21 Analysis was performed on the minutes and meeting papers of meetings with experts to determine whether the ATO absorbed feedback into a single document. Feedback from all external meetings was incorporated with the exception of one meeting with the ABS, however the feedback from this meeting was similar to that provided in a previous meeting with the ABS on 10 March 2015.

Endorsement of the methodology

2.22 On 30 August 2016, the Advisory Panel provided its endorsement of the methodology to determine the tax gap for individuals not in business, endorsing it as ‘defensible and fit for publication’, noting ‘as with all tax gap estimates, we note that as further information becomes available and the approach matures, the estimates are likely to be subject to restatement and/or revision.’

Monitoring best practice and updating methodology

2.23 The ATO’s primary method of remaining up to date on developments in the field is its membership of the Advanced Tax Gap Analysis Community of Practice (known as the OECD Community of Practice). The OECD Community of Practice’s objectives are to share methodologies and best practice to estimate tax gaps more accurately, to share communication strategies for releasing gap estimates to the public, to provide opportunities for cross-border collaboration, and to consult with other relevant groups.

2.24 The ATO advised in May 2022, that to keep up to date on developments in tax gap methodology in academia that it subscribed to various tax research and policy distribution groups, attended academic conferences, and had attended and presented at an international tax gap conference. The ATO also advised in May 2022 that the ‘Expert Panel is also able to assist with staying current with relevant literature.’ There is no standing agenda item in the Expert Panel meeting papers to discuss developments in the field.

2.25 The ATO advised in August 2022 that the team responsible for the tax gap worked with business line leads to improve the tax gap estimate process, with the tax gap team meeting annually to discuss whether any improvements or additional work are required. The ATO provided one example of this occurring. The ATO considered how things had gone over the year, the role played by the Expert Panel, what to expect in the future, and identified the need to improve the reliability of the estimate by working more on ‘[People outside the system], non-detection uplift factors, non-pursuable debt.’

2.26 The ATO advised in May 2022 that the Expert Panel was ‘the avenue for revisions/changes to the tax gap methodology’ with any proposed changes to the methodology submitted as part of the process undertaken to obtain endorsement from the Expert Panel, but that the methodology ‘has remained essentially the same since the first publication’.

IMF best practice

2.27 As mentioned in paragraph 2.5, in 2021, the IMF published The Revenue Administration Gap Analysis Program – An Analytical Framework for Personal Income Tax Gap Estimation (the IMF guide) a technical manual which constituted a better practice guide.

2.28 To attain further assurance over the ATO’s methodology, ATO procedures were analysed against the IMF guide. The ATO’s procedures are largely aligned with the IMF guide, taking into account all components identified by the IMF as significant, reviewing and stratifying the sample selected, calculating net and gross gaps, analysing, reporting and using gap results, conducting regular monitoring and quality assurance of REP work, and fully articulating how sampling should be performed.

2.29 The following elements of the IMF guide have not been considered by the ATO in revising its methodology:

- The IMF suggests using a supplementary estimate or adjustment to cover low frequency but high value risk that a random audit program is unlikely to reliably capture. The ATO does not employ such a measure.

- The IMF also suggests having a clear policy on how and when statistics such as population data and uplifts are revised. The ATO does not have a policy on this matter.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.30 The ATO may wish to consider whether its methodology could be enhanced by considering these elements of the IMF guide. |

Has the ATO’s tax gap methodology been well implemented?

The ATO has implemented its methodology to measure the tax gap for individuals not in business as set out in its guidance. Review and quality assurance processes are fit-for-purpose, and the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business is appropriately endorsed.

2.31 To determine whether the ATO’s methodology has been well implemented, the ANAO focused upon the processes below, each of which plays a material role in producing the gap estimate.

2.32 The ATO’s process for generating the tax gap estimate for 2018–19 formed the basis of the audit team’s analysis. During the audit, the ATO published the tax gap estimate for 2019–20. There was no material change in the ATO’s procedures between the two years.

Extracting the sample for the Random Enquiry Program (REP)

2.33 The ATO’s methodology for estimating the individuals tax gap necessitates the carrying out of a range of steps depicted in Appendix 3.

2.34 The initial step in the ATO’s individuals tax gap methodology is to randomly select a sample of taxpayers whose returns will be reviewed as part of the REP. Responsibility for obtaining this selection is assigned to Smarter Data, the ATO’s specialist data and analytics team.

2.35 Smarter Data’s work in extracting the REP sample is guided by a Target Selection Rationale (TSR) produced annually. This document describes the process for drawing the sample and contains instructions on how to define, stratify29 and exclude certain taxpayers30 from the individuals not in business population.

2.36 A preliminary random sample is obtained, and tax return data for each taxpayer in the sample is provided to the relevant business line for quality assurance.

2.37 The final random sample of 545 taxpayers is extracted, and tax return data for each taxpayer in the sample is provided to the relevant business line. A reserve sample is also generated in case any taxpayer needs to be replaced during manual reviews for the REP.31

2.38 Smarter Data performs the extraction of the sample through the application of Structured Query Language (SQL) code. To assure that the extraction procedure matches the ATO’s documented process, the ANAO analysed the generation of the sample data for the 2018–19 tax gap estimate. The ANAO conducted an SQL code review, examined sampling results, inspected error rates and the use of reserve cases, and reviewed emails between Smarter Data and other business lines. The analysis found that, overall, the ATO produced credible sample data in accordance with TSR specifications. There were no methodological changes between the processes used to extract the sample for the 2018–19 and the most recent (2019–20) tax gap for individuals not in business.

Verifying taxpayers through data driven review

2.39 After obtaining the random sample, the ATO subjects the selected individuals to internal profiling, identifying those who have:

- simple tax affairs;

- a clear residency status;

- income that matches third party data on ATO systems; and

- only small amounts on their tax return that cannot be verified using data.

2.40 The ATO regards any taxpayer who fits these criteria to have an immaterial tax gap and refers to their tax return as ‘data verified’. To minimise compliance costs for taxpayers, the ATO excludes these individuals from having their returns investigated any further. The average number of cases ‘data verified’ is around 21 per cent.

Conducting REP manual reviews

2.41 Sampled individuals whose tax returns are not data verified are progressed to manual review. In the context of the REP, the purpose of a manual review is to determine the difference between a taxpayer’s actual tax liability under the law and the amount originally assessed. It involves the ATO:

- assessing all items of an individual’s return, including the correctness of their income reporting and their entitlement to deductions and offsets; and

- contacting the taxpayer or their agent to obtain substantiation of items on the return — where appropriate, third parties (banks, employers and rental property managers) are also contacted to verify claims.

2.42 The work of conducting the manual reviews is carried out by Case Actioning Officers (CAOs). The ATO advised in August 2022 that CAOs working on the REP are ‘experienced auditors selected from our workforce who are … usually skilled in either rental or work related expenses risks’ (two significant drivers of the individuals tax gap — see Figure 2.1). CAOs receive training on the procedural approach required for the REP.

2.43 The work of CAOs is supported by guidance documentation and templates. Guidance Notes for CAOs detail the steps for actioning cases and refer the reader to other guidance documentation and templates.

2.44 Manual reviews are conducted with the use of Siebel, the ATO’s Client Relationship Management system. The process of carrying out the REP case work as a review versus an audit is similar. The key differences between the two are that:

- in an audit, the ATO can amend a return without the taxpayer’s consent;

- penalties are not imposed for REP review cases; and

- audit cases are subject to formal objection rights, while review cases are not.

2.45 The work of CAOs is supervised by Team Leaders and Tax Technical Assessors (TTAs).

2.46 CAOs record their observations during manual reviews in the form of notes on Siebel and in template documents attached to Siebel. CAOs also capture all REP case results in an Access Database. Data extracted from this database underpins the calculation of the tax gap. Entries in the Access Database are reviewed by Team Leaders at the completion of a case.

2.47 The results of the REP and analysis of these outcomes are collated in a document known as a Close Out Report.

Quality assurance of REP manual reviews

2.48 The IMF Guide notes that ‘regular monitoring and quality assurance reviews can … facilitate higher standards of data recording’, and identifies ‘quality assurance audits, and especially data recording’ as important elements of a REP.

2.49 As mentioned at paragraphs 2.45 and 2.46, the manual reviews for the REP are supervised by Team Leaders and TTAs, who conduct quality control processes at various stages as CAOs carry out their work. In addition, there are quality control checks performed by staff from two separate technical areas within the ATO.

2.50 Since the 2014–15 individuals tax gap estimate, the ATO has also engaged a former Deputy President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal to ‘review, and assess the correctness and consistency of, specified case work undertaken by case officers for the REP’. This external reviewer has analysed an average of 68 cases per year. Reports published by the reviewer have tracked the performance of the case work that underpins the REP year-to-year, with his report on the ATO’s manual reviews of 2017–18 tax returns observing that:

I have previously reviewed the program for the 2015, 2016 and 2017 income years and had seen marked improvement from one year to the next — not so much in the quality of the work I was reviewing (which was already of a high standard) but in the way it was being recorded.

2.51 The reviewer concluded:

I am also comfortably satisfied that, across the 70 cases reviewed, there has been consistency in the method of calculating the tax adjustments decided upon, and correct recording of those adjustments in the tax gap database.

2.52 The ATO’s employment of three levels of internal review, and having an external reviewer track the performance of case work, provides a fit-for-purpose framework to provide quality assurance over the conduct of the REP.

Methodological process to determine the final tax gap

2.53 Both the verified cases and the findings from the REP case work are ‘fed into’ a ‘methodological process … to determine the final tax gap’. This methodological process is laid out in the Technical Guide and has the steps described in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Methodological process for calculating individuals not in business tax gap

|

Step |

Description |

|

|

1a |

Estimate unreported amounts for reviewed sample in each stratum. |

Across the returns from the random sample that were manually reviewed by CAOs, identify the mean amendment for taxpayers with an amendment as well as the incidence rate of amendment for the whole sample. |

|

1b |

Estimate unreported amounts for verified sample in each stratum. |

See from paragraph 2.57 below. |

|

1c |

Combine results and extrapolate to population in each stratum. |

Combine the incidence rates and means from steps 1a–1b to estimate the unreported tax liability for each stratum. |

|

1d |

Add up base unreported tax liabilities. |

Aggregate the unreported amounts for all strata. |

|

1e |

Apply estimate for people outside the system. |

See from paragraph 2.59 below. |

|

2 |

Estimate for errors not detected. |

See from paragraph 2.62 below. |

|

3 |

Estimate for non-pursuable debt. |

Add the figure for non-pursuable debt.a |

|

4 |

Estimate the gross gap. |

Add together the results of steps 1–3. |

|

5 |

Estimate the net gap. |

Subtract the figure for amendments from the gross gap.b |

|

6 |

Estimate theoretical liability. |

Add the net gap to the amount of tax paid.c |

Note a: Non-pursuable debt refers to tax liabilities that the Commissioner of Taxation has assessed to be not legally recoverable or not economical to pursue.

Note b: The figure for amendments represents the amount recovered through the ATO’s broader compliance activities. It is generated early in the estimation process. To ascertain the figure, the ATO employs a ‘minimum client initiated’ approach that compares what a taxpayer would have voluntarily paid with their ultimate assessment.

Note c: Tax paid is the equivalent of tax reported minus the value of non-pursuable debt. Tax reported uses the ‘net tax’ definition in line with Taxation Statistics and other publications.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

2.54 Prior to putting the data from the sampled cases through the methodological process, the ATO applies its bundling approach. As discussed at paragraph 2.13, when working out the individuals tax gap for a given year, the ATO’s chosen method is to combine the random sample of 545 tax returns for that year with the random samples for two previous years, producing an overall sample of 1635 cases.

2.55 Notwithstanding the ATO’s chosen bundling approach, when a particular year’s tax gap estimate is first published, it is based only on the random samples for the two previous years (1090 cases). This is due to the timing of the REP manual reviews: when a gap estimate is being endorsed and prepared for initial publication, there are usually numerous REP cases from the latest year that have not yet been finalised. It is only when the ATO comes to calculate the individuals tax gap for a subsequent year — at which point it also refreshes previously published estimates — that it incorporates data from a full three-year sample.32

2.56 Additionally, certain figures involved in estimating the individuals tax gap take substantial time to become final.33 Accordingly, when the ATO initially estimates a gap, it uplifts or uses projections for these figures. The ATO then replaces these uplifts and projections with gradually more complete data through its process of refreshing earlier estimates.

Estimating unreported amounts for the verified sample (step 1b)

2.57 The purpose of step 1b is to establish a mean amendment and incidence rate of amendments for those individuals who were sampled as part of the REP but did not have their tax returns manually investigated because they were verified through data driven review (see from paragraph 2.39). The ATO advised in June 2022 that it carries out this step because even if such individuals have had their returns data verified, the ATO cannot confidently conclude that they have completely complied with their tax obligations. One reason for this is that the criteria for verifying tax returns means that verified taxpayers may still be entitled to and/or have claimed deductions.

2.58 To identify the mean amendment and incidence rate of amendments for the verified group, the ATO applies data from manually reviewed taxpayers who claimed less than $1000 in deductions.34 The ATO considers these manually reviewed individuals to be representative of the verified group, and expects them to have similar errors in their tax returns.

Estimating for people outside the system (step 1e)

2.59 The ATO’s estimate for people outside the system (POTS) is intended to account for the impact of ‘non-registrants or long-term non-lodgers on the gap’. The estimate uses ABS population data and income tax returns lodged by individuals, and makes assumptions regarding people who may not need to lodge. The ATO combines this estimate with the results from the REP to identify the number of POTS who have potential tax obligations and the theoretical amounts owing, and apportions the population and amounts between individuals in and not in business.

2.60 In estimating the impact of POTS, the ATO assumes that ‘the incidence and relative magnitude of income non-compliance in the [REP] is representative of the incidence and magnitude of income non-compliance outside the system’. The ATO acknowledged in June 2022 that the nature of the assumptions used for the POTS estimate are subjective.

2.61 Along with the assumptions made in steps 1b and 1e, the ATO makes a series of other assumptions (see Appendix 4). The ATO’s Reliability Assessment requires the ‘sensitivity to underlying model, assumptions, judgement or expertise’, and ‘assessment of assumptions, judgement or expertise’ to be considered when deriving a Reliability Assessment (see from paragraph 2.79).

Estimating for errors not detected (step 2)

2.62 The Technical Guide states that ‘to derive a credible gap estimate’, the ATO must add estimates for non-detection to the base unreported tax liability ascertained through steps 1a–1e above. The ATO has identified ‘three factors that contribute to non-detection’ in the context of the individuals not in business gap:

- income misreporting;

- deductions and other issues; and

- the impact of hidden wages.

2.63 The ATO’s processes for estimating each of the above factors differs. To account for income misreporting, the ATO uses a standard uplift based on international research. For deductions and other issues, the ATO applies an uplift based on the findings from the external review of the REP manual reviews (see from paragraph 2.50), which it applies to the part of the unreported tax liability that can be attributed to non-income issues. The estimation of the impact of hidden wages draws upon data from the ATO’s pay as you go withholding gap estimate about the base tax impact of hidden wages. By making allowances for refunds, the ATO converts this base impact to the effective impact of hidden wages on individuals income tax, and then apportions this between the individuals not in business and other tax gaps.

ANAO verification of methodological process

2.64 The ATO provided the ANAO with input and output data for each step of the methodological process as conducted for the estimation of the 2018–19 individuals not in business tax gap. Following the ATO’s procedures as outlined in the Technical Guide and other relevant guidance, the ANAO replicated the process. It was found that that the ATO’s methodological process was repeatable and a result materially the same as the ATO’s was achieved.

Endorsement of the tax gap estimate

2.65 The Tax Gap Expert Panel Charter outlines the ATO’s expectations from the Expert Panel regarding endorsement of the tax gap estimate:

The Tax Gap program team will look to the Expert Panel for:

- Assessment and, as appropriate, endorsement of results for presentation to the ATO Executive.

- Support in terms of the ATO communications of the gap program credibility and reliability as well as contextualising the methodologies and results on an international basis.

2.66 While the Expert Panel Charter has been amended several times since its inception in 2016, these portions have remained consistent throughout.

2.67 The Expert Panel endorsed the 2018–19 tax gap estimate on 27 May 2021. When asked to provide evidence of the Expert Panel endorsing the latest technical guide, the ATO stated: ‘As there were no methodological changes between 2021 and 2022, and no changes to the reliability rating, the 2022 technical guide was not submitted for endorsement’.

2.68 The tax gap for individuals not in business is also reported in the ATO’s Annual Report. The ATO Executive approves the estimate as part of its process of approving the broader ATO Annual Report.

Has the ATO’s tax gap methodology been well-communicated?

The tax gap methodology is generally well communicated. A summarised version of the methodology for the individuals not in business tax gap is published on the ATO website, though the ATO could improve transparency by publishing its Technical Guide in full. The ATO publishes an assessment of the reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business to indicate the ATO’s level of confidence in the accuracy of the estimate. The ATO has not recorded the processes or outcomes of meetings held to establish reliability assessments since estimation of the tax gap for individuals not in business commenced.

Public reporting

2.69 The ATO publishes a summary version of the methodology used to measure the individuals tax gap on its website35, the individuals tax gap estimate36, and the most recent reliability estimate on both its website37 and in its Annual Report.38 This has taken place since 2018. The ATO started using the methodology detailed above in 2016 and started publishing these findings in 2018.

2.70 While the Technical Guide is not publicly available, the ATO publishes a summarised version of the Technical Guide online.39 The ATO has a public-facing focus on; describing what the gap is, communicating what drives the gap, and the reliability of its work.

2.71 The ATO describes the tax gap on its website by providing an overview from the 2014–15 estimate to the 2019–20 estimate. The website summary is less descriptive than the Technical Guide and consolidates some steps, but is accurate in describing the methodology.

2.72 Key drivers for the individuals not in business tax gap are communicated as work related expenses, rentals, hidden (which includes hidden or undeclared income) and ‘other’, depicted in Figure 2.1. The ‘other’ category is not described.40 The ATO caveats its work through the reliability assessment and support of the Expert Panel.

Figure 2.1: Drivers of the Individuals Not in Business Tax Gap, 2019–20

Source: ATO documentation.

2.73 The ATO applies reliability assessments to its tax gap estimates to support internal scrutiny of the methodology and of the level of confidence in the accuracy of the estimates themselves (see from paragraph 2.78). Beyond publishing a reliability score of up to 30 and the rating scale ranging from very low to very high, the assessment process and the Expert Panel review process are not communicated to the public. The reliability assessment criteria are not available through the individuals not in business tax gap webpage, though it is discoverable on the ATO website when the search function is used. The ATO publishes information on previous estimates.41 Tax gap data for the five years prior to the reporting year is published on the ATO website (see, for example Table 1.1). Reliability scores for prior tax gap releases are not available on the same webpage to enable the reader to determine the reliability of previous years estimates.42

2.74 HMRC’s tax gap is an official statistic and the estimate is produced in line with the UK Code of Practice for Statistics, which states: ‘there is no point in publishing statistics that do not command confidence.’43 The ATO did not publish the tax gap until it was considered ‘highly reliable’ in the 2015–16 tax year. This estimate was published in 2018. However, the data for earlier years, where the reliability of the estimate was assessed by the ATO to be lower, is available to the public without any context to explain its lower reliability. Publication of previous reliability assessments would increase understanding of how reliability has changed as the measurement process has developed.

2.75 The ATO’s 2021–22 Annual Report outlines its intent to improve transparency as a part of the strategic objective.44 The publication of the tax gap estimate is important for transparency. The information which has been excluded, particularly relating to the trustworthiness of the estimate, may result in the public not having a full understanding of the reliability of the gap estimate.

Recommendation no.1

2.76 The Australian Taxation Office publish the Individuals Not In Business Tax Gap Technical Guide in full to enable transparency as to how the tax gap for individuals not in business is estimated.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.77 The ATO agrees with the recommendation to publish the Technical Guide for Individuals not in Business, noting some challenges around accessibility and the sensitivity of the information contained within it.

Reliability Assessments

2.78 The reliability assessment process is a self-assessment framework used by ATO to examine its framework, methodology and internal processes, and to determine and communicate the credibility of its gap estimate to the public. In 2016, the ATO implemented ten measures which form the reliability assessment criteria.

2.79 The 10 criteria used in the current reliability assessment are depicted in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Reliability assessment criteria

|

Step |

Description |

|

Evaluation of the estimation framework |

|

|

1 |

Captures the appropriate tax base |

|

2 |

Covers all potential taxpayers |

|

3 |

Accounts for all potential forms of non-compliance |

|

4 |

No overlap within or between any components of the framework |

|

Evaluation of the methodology |

|

|

5 |

Evaluate the approach used against the assessment criteria for that methodology |

|

6 |

Most appropriate method used and results validated against supporting information |

|

7 |

Sensitivity to underlying model, assumptions and structure |

|

8 |

Assessment of assumptions, judgement or expertise |

|

Evaluation of the internal process and delivery |

|

|

9 |

Evaluate the reliability of the documentation and the repeatability of the data |

|

10 |

The estimate analysis provides a meaningful explanation of the outcomes and drivers of a gap estimate |

Source: ATO documentation.

2.80 The reliability assessment criteria were established by the ATO, drawing on its own expertise and the IMF’s Assessment of HMRC’s Tax Gap Analysis. The ATO sought the Expert Panel’s feedback45 on the reliability assessment criteria.

2.81 Criteria one to four have been specifically sourced from the criteria developed by the IMF for its review of HRMC Tax Gap Analysis. Criteria five reflects a condensed version of the IMF criteria while maintaining its intention. Criteria six to ten were designed by the ATO and reviewed by the Expert Panel. Based on feedback from the Expert Panel in September of 2018, changes were made to the reliability assessment criteria.

2.82 The rating scale for the ATO’s assessment reflects the assessment used in the IMF’s review. The IMF review focused on communicating effectiveness and reliability while the ATOs objective is to rate and track its reliability. To do this, the ATO represents its reliability on a zero to thirty scale.

2.83 The ATO’s Reliability Assessment Guide explains: ‘the assignment of scores against criterion is carried out in a thorough and collaborative approach between business lines, the Tax Gap Expert Panel, and the ATO Executive.’ The ATO advised in May 2022, ‘[t]he reliability ratings are a judgment based assessment, conducted by the tax gap team and recorded in the Technical Guide. Typically it is a conversation held with the EL1 stream lead, supporting Analysts and the Director.’

2.84 Meetings where the reliability assessment score is assigned are not minuted, no agendas are prepared and, as a result, there is no evidence of meetings occurring. While there is a methodology in place, as a consequence of this lack of documentation, there is no evidence to demonstrate how a reliability assessment score has been determined, or whether key assumptions (see paragraph 2.61) have been properly reviewed.

Recommendation no.2

2.85 The Australian Taxation Office document the process of assessing reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business to support transparency and confidence in the accuracy of the estimate.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.86 The ATO agrees to document the process of assessing reliability of the tax gap estimate for individuals not in business.

2.87 The Tax Gap Expert Panel Charter states the ‘program team will look to the expert panel for assessment and, as appropriate, endorsement.’ Endorsements should be recorded in the relevant meeting minutes and the technical guide. Endorsements are recorded in Table 2.5. The panel does not have any role in the allocation of ratings.

Table 2.5: Reliability ratings, allocation and endorsement 2013–14 to 2019–20

|

Tax year |

Reliability rating |

Reliability allocation |

Expert Panel endorsement |

|

2013–14 |

3/30 |

Very Low |

Endorsed |

|

2014–15 |

20/30 |

Medium |

Endorsed |

|

2015–16 |

21/30 |

High |

Endorsed |

|

2016–17 |

21/30 |

High |

Endorsed |

|

2017–18 |

22/30 (revised from 21/30) |

High |

Endorsed |

|

2018–19 |

22/30 |

High |

Endorsed |

|

2019–20 |

22/30 |

High |

Not sought |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.88 There is no evidence of the ATO executive explicitly endorsing the outcome of the reliability assessment process, however, the reliability assessment is included in the ATO Annual Report, which is signed off by the ATO Executive.

3. Implementing risk-based compliance strategies to reduce the tax gap

Areas examined

This chapter examined whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) identifies and prioritises risks to the individuals not in business tax gap at the business and enterprise level, develops compliance strategies to address these risks, and implements these compliance strategies as intended.

Conclusion

The ATO has sound processes for identifying and developing compliance strategies to address risks to the individuals not in business tax gap, though inconsistent application of ATO guidance undermines the effective implementation of these strategies. The tax gap measurement process and estimate inform business and enterprise level risks to the individuals not in business tax gap. Performance of the tax system for individuals not in business is monitored, and compliance strategies are developed if necessary. ATO guidance to implement compliance strategies is applied inconsistently, and as compliance strategies do not contain specific targets, the ATO is unable to determine the extent to which compliance strategies contribute to reducing the tax gap for individuals not in business.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation relating to the ATO setting specific measurable targets and developing benchmarks for use in Measurement and Evaluation Plans.

The ANAO also suggested that that the ATO ensure that program logic documents are endorsed in accordance with the Measurement and Evaluation Guidelines.

3.1 The ATO’s Corporate Plan 2022–23 identifies the tax gap as part of a strategic objective: ‘We build community confidence by sustainably reducing the tax gap and providing assurance across the tax, superannuation and registry systems.’46 This requires the ATO to develop and implement compliance strategies to address identified tax risks to reducing the tax gap.

Does the ATO have sound processes for identifying and prioritising tax risks?

The ATO has sound processes for identifying and prioritising risks to the individuals not in business tax gap at the business and enterprise level. Procedures governing the operation of the ATO’s risk management framework are comprehensive and well-articulated. The findings from the tax gap measurement process and the estimate inform the risks that relate to the tax gap for individuals not in business.

Processes for identifying and prioritising tax risks at the enterprise level

3.2 The two documents that govern the operation of the ATO’s risk management framework are the ATO’s Risk Management Guide, and the ATO’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework (ERMF). They constitute the basis for the way ATO staff should seek to identify and address risks.

3.3 The ATO’s Risk Management Guide states that the ‘[ERMF] and risk management processes apply to all levels of risk across the ATO.’ The ATO’s Risk Management Process is based on ISO 31000:201847, outlining the cyclical nature of the process, and is depicted in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: The ATO’s Risk Management Process

Source: ATO documentation.

3.4 This framework states that the risk methodology is ‘the practical tool that should be used in all planning activities to ensure a positive and proactive approach to risk management is applied.’ The Risk Management Guide also notes that prioritisation of risk is an integral part of the risk assessment process.

3.5 The ATO’s Risk Management Guide requires staff to enter enterprise level risks (and business level risks where appropriate) on its Enterprise Risk Register (ERR). Further, the ERMF states: ‘The ATO will regularly monitor risk and adjust its strategies, goals and activities to reflect changing priorities resulting from emerging risks and the changing environment.’

3.6 When a newly developing or changing risk that may have a major impact on the ATO is identified, the ATO’s Risk Management Guide says that new or evolving risks ‘…can be entered into the enterprise risk register as emerging risks and updated over time…’ Four emerging risk assessments relating to individuals not in business were conducted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.7 The ATO’s Risk Management Guide notes:

The purpose of monitoring and review is to assure and improve the quality and effectiveness of process, design, implementation and outcomes. In monitoring and reviewing, it is necessary to:

- review risk ratings whenever there are changes in the environment

- monitor risks through evaluation of the effectiveness of existing controls and treatment plans and ongoing observations of the risk environment.

3.8 Further information on monitoring and review is available from paragraph 4.12.

3.9 Guidance on risk management is made available to staff through internal risk management training courses, and risk management templates are provided on the ATO Intranet.

Oversight of enterprise level risks

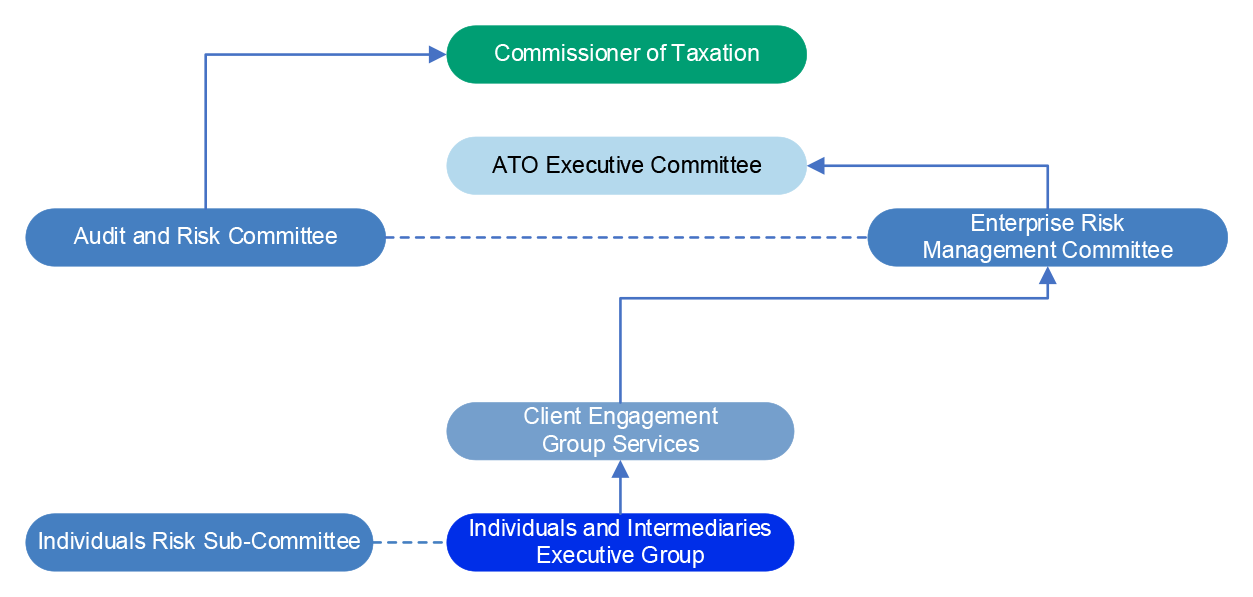

3.10 Figure 3.2 illustrates the ATO’s governance structure around risk. Client Engagement Group Services is the group relevant to Individuals and Intermediaries.

Figure 3.2: Risk Governance Structure

Source: ATO’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework.

3.11 The ERMF outlines the ATO’s hierarchy of risks, those with primary involvement in the risk management process, and identifies risk owners:

- Strategic Risk — Accountability for strategic risks may be assigned to individual ATO Executive members;

- Enterprise Risk — Owned and managed at the SES level and overseen by the Enterprise Risk Management Committee; and

- Business Risk — ‘Owned and managed by a Band 1, EL2 or EL1 level staff member’.

3.12 The ATO’s Risk Management Guide addresses the issue of endorsement of risks: ‘The date of endorsement entered on the ERR is the date that the risk was endorsed by the risk owner. Evidence of risk endorsement may be attached to the ERR or retained within the business area.’ The ATO advised in September 2022 that its practice is to endorse risks through the approval of risk assessment documents.

3.13 Analysis of the six risk assessment documents prepared in respect of individuals not in business since 2018 indicated that all six were not endorsed by the risk owner, though five were endorsed instead by the risk manager or the risk steward, with the ATO considering the sixth to be ‘treated as endorsed’ by the Individuals Risk Sub-Committee. ATO documentation occasionally displayed confusion about who the owner of a risk actually was, incorrectly listing the person who was the risk manager or the risk steward in the owner’s place.

3.14 The Risk Management Guide also states that ‘Enterprise risks should be reviewed every twelve months as a minimum. Enterprise risks that are not within tolerance may need to be reviewed more frequently’. Analysis of risk review documents related to individuals not in business since 2018 indicated that the ATO reviewed risks in accordance with these required timeframes, and reviews were signed off by a risk manager or risk steward.

3.15 The ATO has also established an Individuals Risk Sub-Committee (the Sub-Committee), chaired by an Assistant Commissioner. The Sub-Committee is a strategic decision-making body for all work programs in the area of Individuals Client Experience. Its purpose is to ensure risks are effectively managed, and governance requirements are met.

3.16 The Sub-Committee can also make resource recommendations to ensure ATO investments appropriately target taxpayer behaviour risks that contribute to the individuals not in business tax gap, which are then sent to the Individuals and Intermediaries Executive Group for consideration and approval.

3.17 Analysis on the operation of the Individuals Risk Sub-Committee is available from paragraph 4.53.

Enterprise level risks relating to Individuals not in business

3.18 There are three business or enterprise level risks relating to individuals not in business that are managed by the Individuals and Intermediaries business line. These are depicted in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Individuals not in business risks and sub-risks

|

Risk |

Sub-risks |

Risk assessment |

Treatment plan required and developed |

|

Individuals fail to correctly report all their income |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Individuals incorrectly claim deductions |

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

Individuals incorrectly claim credits, exemptions and/or tax offsets |

|

✔ |

N/Aa |

|

Key: ✔ The document has been completed N/A The document is not required |

|||

Note a: A treatment plan was not required as the risk was within tolerance.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

3.19 Each of the Individuals not in business risk assessments align to the ATO’s corporate plan objective to build community confidence by sustainably reducing the tax gap.

3.20 The tax gap estimate and findings from the REP are used to inform decision making around risk. The ATO stated that ‘outputs from the Tax Gap estimate include insights from the [REP] that provides opportunities to deepen our understanding of the behavioural drivers and errors that lead to adjustments made to returns’, and that ‘[t]he tax gap estimate is helpful in confirming that we have prioritised the management of certain risks such as work related expenses and net rental income as they continue to be the main risk drivers of the gap.’

3.21 For example, for the risk assessment for individuals fail to correctly report all their income, the strategy to achieve the objective to build community confidence by sustainably reducing the gap, seeks to reduce the tax gap by being streamlined, integrated, and data driven, and by improving the client experience. The insights contained in Close Out Reports (see paragraph 2.47) from previous REPs (specifically compliance behaviour, and revenue impacts) inform the content of the risk assessment.

3.22 To address the tax gap, the ATO employs compliance strategies.48

Have compliance strategies been developed for identified tax risks?

The ATO develops compliance strategies that target specific groups of taxpayers to address business and enterprise level risks to the tax gap for individuals not in business. Data from lodged tax returns are assessed against established tolerances, and when performance moves out of tolerance, the ATO is prompted to consider whether a compliance strategy is required.