Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Indigenous Advancement Strategy — Children and Schooling Program and Safety and Wellbeing Program

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS), the Australian Government funds and delivers programs for Indigenous Australians.

- The Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs are two of six IAS grant programs, with the second and third largest administered budgets respectively.

- Shortcomings in the administration of Indigenous grants programs have been identified in previous ANAO audits and Parliamentary inquiries.

Key facts

- The IAS was established in 2014.

- On 1 July 2019 responsibility for Indigenous Affairs was transferred from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet to NIAA.

- The administered budget for the IAS is $5.2 billion from 2019–20 to 2022–23.

- Children and Schooling program activities include after-school care, school nutrition projects, mentoring programs and capital works projects.

- Safety and Wellbeing program activities aim to reduce violence and alcohol and substance abuse; and build support for individuals, families and communities.

What did we find?

- The National Indigenous Australians Agency’s (NIAA) administration of the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs has been largely effective.

- Administration of the programs is compliant with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) but not consistent with the principles underlying the CGRGs to achieve value with relevant money.

- The majority of grant funding is allocated, following assessment, through a non-competitive approach.

- NIAA has implemented changes that have the potential to improve its administration of the program.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made five recommendations to NIAA regarding communication about available funding; achieving value for money; data validation; the methodology for calculating performance information; and performance measures in the corporate plan.

- NIAA agreed to the five recommendations

$1.24 billion

allocated to the Children and Schooling program from 2019–20 to 2022–23.

$1.17 billion

allocated to the Safety and Wellbeing program from 2019–20 to 2022–23.

709 activities

funded through the Children and Schooling program as at 30 June 2020.

535 activities

funded through the Safety and Wellbeing program as at 30 June 2020.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) the Australian Government funds and delivers a range of programs specifically for Indigenous Australians. In the 2019–20 Budget, the Australian Government allocated $5.2 billion over four years from 2019–20 to 2022–23 to the IAS, for grant funding processes and administered procurement activities. The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) administers the IAS.1

2. The Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs are two of the six IAS grant programs, with administered budgets of $305.04 million and $279.88 million respectively in 2019–20.

3. The objectives of the Children and Schooling program are to:

Get children to school, particularly in remote Indigenous communities, improving education outcomes and supporting families to give children a good start in life. This program includes measures to improve access to further education.2

4. The objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing program are to:

Ensure that the ordinary law of the land applies in Indigenous communities, and ensure that Indigenous people enjoy similar levels of physical, emotional and social wellbeing enjoyed by other Australians.3

Rationale for undertaking the audits

5. The IAS is one of the means through which the Australian Government has been trying to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Among the six IAS programs, the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs have the second and third largest administered budgets respectively. ANAO performance audits4, as well as Parliamentary inquiries5 and departmental reviews, have shown that there have been shortcomings in the administration of the IAS. Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 Indigenous Advancement Strategy concluded that the ‘department’s grants administration processes fell short of the standard required to effectively manage a billion dollars of Commonwealth resources’. This report discusses NIAA’s progress in implementing relevant recommendations from Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 and provides assurance to Parliament and the public about the effectiveness of the administration of the IAS, focusing on the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs.

Objective and criteria of the audits

6. The ANAO conducted separate audits of the IAS Children and Schooling program and the IAS Safety and Wellbeing program, the findings and conclusions of which are presented in this report. The objective of the audits was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s (PM&C’s) and NIAA’s administration of the IAS Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective of the audits, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Have the programs been designed and implemented to support the Government’s objectives?

- Are grant assessments consistent with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) and program guidelines?

- Is the management of grants consistent with the CGRGs and program guidelines?

- Does the performance framework support the effective administration of grants and enable ongoing assessment of progress towards outcomes?

Conclusion

8. NIAA’s administration of the IAS Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs has been largely effective.

9. The Children and Schooling program was designed and implemented to support the Australian Government’s objectives for improved education. The Safety and Wellbeing program was largely designed and implemented to support the Australian Government’s objectives for healthier and safer homes and communities. For both programs, the IAS Grant Guidelines are compliant with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs), but are not consistent with Department of Finance’s guidance relating to communication about program funding availability.

10. Assessments are compliant with the CGRGs and the IAS Grant Guidelines for both programs, but are not consistent with the principles underlying the CGRGs to achieve value with relevant money — between July 2016 and June 2019 a large majority of Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing grant funding was allocated using a non-competitive approach and grants were reallocated to the same providers. NIAA has arrangements in place to ensure that regional priorities and potential gaps and duplications in service delivery are considered. Since 2018–19 NIAA has improved its timeliness in assessing applications.

11. The management of Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing grants is now largely consistent with the CGRGs and the IAS Grant Guidelines. Changes introduced since 2019, including a new grant risk management framework, have the potential to improve the effectiveness of NIAA’s management of grants. The redesigned key performance indicators (KPIs) have also improved NIAA’s ability to measure progress against outcomes for both programs, but NIAA does not sufficiently validate self-reported provider data. Prior to this, grant agreements were not always appropriate and risk-based. Record-keeping practices in some areas remain poor.

12. The performance framework partially supports program administration and ongoing assessment of progress towards outcomes. There is alignment between the Children and Schooling program objectives in the portfolio budget statements (PBS) and NIAA’s corporate plan. The Safety and Wellbeing program is described more broadly in the PBS than in NIAA’s corporate plan. Performance information for the two programs is not fully appropriate and comprehensive information generated from processes to collect lessons learnt is not yet sufficiently integrated to effectively inform administration of the two programs.

Supporting findings

Program Design and Implementation

13. The objectives of the Children and Schooling program align with Australian Government policy objectives for improved educational outcomes for Indigenous Australians. The objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing program broadly align with Australian Government policy objectives of healthy homes and safe communities for Indigenous Australians. The development of a Policy and Investment Framework in 2019 has the potential to strengthen the coordination and strategic direction of the IAS, including the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs.

14. Appropriate governance arrangements have been established. Although the two key governance boards did not meet as regularly as scheduled during 2018 and 2019, evidence exists that they provided strategic and operational direction to the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs.

15. Until 2019 there were weaknesses in systems to support staff to assess and manage grants that NIAA has worked to address. As a result, systems are now largely fit-for-purpose, although mandatory grants administration training was still in the pilot stage in April 2020.

16. The IAS Grant Guidelines are compliant with the CGRGs but NIAA’s communication about the programs’ funding availability is not transparent, which is inconsistent with Department of Finance guidance.

Grant Assessment

17. Selection processes are not applied in a manner that demonstrates that a value for money outcome has been achieved. Between July 2016 to June 2019, 90 per cent of the Children and Schooling program funding and 95 per cent of the Safety and Wellbeing program funding was allocated on a non-competitive basis. This is inconsistent with the principles of the CGRGs and with NIAA’s guidance. Also 80 per cent of the Children and Schooling program funding and 87 per cent of the Safety and Wellbeing program funding was reallocated to the same providers after assessment.

18. Assessments are compliant with the CGRGs and the IAS Grant Guidelines.

19. NIAA considers regional strategies and potential gaps and duplications when assessing grants.

20. Advice provided to the minister complied with the requirements of the CGRGs. Since 2018–19 NIAA has improved its timeliness in assessing applications and providing advice to the minister.

Grant Management

21. Grant agreements executed before 2019 were not always appropriate and risk-based. The new grant risk management framework introduced in early 2019 provides the basis for a better balance between risk and monitoring requirements in agreements. The revised KPIs have improved NIAA’s ability to measure activities’ achievements against grant objectives.

22. NIAA has mechanisms for monitoring the progress of grant activities, including provider performance reports and site visits. The effectiveness of these mechanisms is limited by poor record-keeping practices and insufficient validation of self-reported provider data. In early 2019 NIAA established a grant assurance function. The role of the function is being reconsidered to strengthen its ability to improve the quality and consistency of key grant processes.

23. NIAA has mechanisms in place to address situations where the purpose of the grant is not being fulfilled. Recent organisational and process changes have the potential to improve the detection and treatment of provider non-compliance with funding requirements.

Performance Assessment and Management

24. A performance framework has been implemented for the programs. There is alignment between the Children and Schooling program objectives in the PBS and the relevant activities in NIAA’s corporate plan. For the Safety and Wellbeing program, the scope of the program is broader in the PBS than in NIAA’s corporate plan and NIAA’s corporate plan does not explain why there are differences. Performance information for the two programs is not fully appropriate as it is only partially reliable and adequate. The programs’ measures in NIAA corporate plan could be improved by ensuring that they address outcomes and, for the Children and Schooling program, the complete purpose of the activities.

25. An online reporting solution now enables NIAA to generate reports that support executive consideration of program performance.

26. NIAA collects lessons learnt through a variety of processes. The considerable amount of valuable information generated is not yet sufficiently integrated to effectively inform program administration.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.55

The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensures that up-to-date information about grant funding available for the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs is publicly available.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agree.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.16

The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensures that its approaches to grants assessment:

- achieves value with relevant money; and

- is consistent with its policy and guidance and with the principles underlying the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agree.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 4.23

The National Indigenous Australians Agency implements mechanisms to validate the data reported by providers, including self-reported data.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agree.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 5.17

The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensures that:

- its methodology for calculating Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs’ performance information includes only KPIs relevant to the programs’ objectives; and

- the annual performance statement discloses all limitations associated with the reported results.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agree.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 5.24

The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensures that performance measures in its corporate plan are appropriate, including that the measures allow an assessment of outcomes.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agree.

Summary of entity response

National Indigenous Australians Agency

The National Indigenous Australians Agency (the Agency) welcomes the overall conclusion that the Agency’s administration of the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs has been largely effective. We also appreciate the key findings that the IAS Grant Guidelines, grant assessments, and grant management are compliant with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines 2017 (CGRGs). We also welcome the report highlighting some of the significant work the Agency has undertaken since the establishment of the IAS, to improve the way funding is delivered and outcomes are achieved, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Under the Children and Schooling program and Safety and Wellbeing program, the Agency funds over 1,200 activities across Australia. These services are aimed at addressing economic and geographic barriers while promoting early childhood development, school attendance and attainment, health and wellbeing and safe communities.

The Agency is proud of the work it undertakes and the commitment of its staff to improving the lives of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We will continue to work with communities to address their priorities. We will also continue working with service providers to minimise their administrative burden in line with the CGRGs and focus on achieving government policy objectives for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Agency has agreed to all of the report’s recommendations, noting that at the time of the audit a number of actions to address these were in place, had already been taken or were underway to make improvements consistent with the recommendations. In this regard, the Agency considers recommendations one and four are already completed. The Agency will continue to ensure the broader lessons are applied where applicable and we will retain our continuous improvement approach.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

27. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Grants

Policy/program design

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

The Indigenous Advancement Strategy

1.1 Through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) the Australian Government funds and delivers a range of programs specifically for Indigenous Australians. Initially, $4.8 billion was committed to the IAS over four years from 2014–15. In the 2019–20 Budget, the Australian Government allocated an additional $5.2 billion over four years from 2019–20 to 2022–23 to the IAS, for grant funding processes and administered procurement activities.

1.2 The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) administers the IAS. NIAA was established as an executive agency within the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio on 1 July 2019 and is the lead entity for Commonwealth policy development, program design, implementation and service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Between 2013 and 2019 the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) was the lead agency for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs within the Australian Government and administered the IAS.6

1.3 There are six IAS programs7:

- Program 1.1 — Jobs, Land and Economy;

- Program 1.2 — Children and Schooling;

- Program 1.3 — Safety and Wellbeing;

- Program 1.4 — Culture and Capability;

- Program 1.5 — Remote Australia Strategies; and

- Program 1.6 — Research and Evaluation.

1.4 The Children and Schooling program and the Safety and Wellbeing program are examined in this report. The objectives of the Children and Schooling program are to:

Get children to school, particularly in remote Indigenous communities, improving education outcomes and supporting families to give children a good start in life. This program includes measures to improve access to further education.8

1.5 The program’s focus is on increased school attendance and improved educational outcomes that lead to employment. A broad range of activities are funded under the program, including activities that aim to improve family and parenting support; early childhood development, care and education; school education; youth engagement and transition; and higher education.9 In 2019–20, the Children and Schooling program’s administered budget was $305.04 million.10 As at 30 June 2020, 709 grant activities were funded through the Children and Schooling program.

1.6 The objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing program are to:

Ensure that the ordinary law of the land applies in Indigenous communities, and ensure that Indigenous people enjoy similar levels of physical, emotional and social wellbeing enjoyed by other Australians.11

1.7 The program seeks to increase levels of community safety and individual wellbeing by funding initiatives that aim to: reduce all kinds of violence and provide support for victims; reduce alcohol and substance misuse; reduce the rates of offending or recidivism; and enhance connection to family and community and build the capacity of individuals to respond to life stressors.12 In 2019–20 the Safety and Wellbeing program’s administered budget was $279.88 million.13 As at 30 June 2020, 535 grant activities were funded through the Safety and Wellbeing program.

The National Indigenous Reform Agreement

1.8 The IAS Grant Guidelines note that Australia will only achieve its true potential when all Australians, including Indigenous Australians, have equal opportunity to participate in all aspects of society.14 Research has shown that Indigenous people have worse health, higher mortality, lower literacy and numeracy, and higher rates of child abuse and adult imprisonment than non-Indigenous Australians.15

1.9 In 2006 the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to an intergovernmental approach to ‘closing the gap in outcomes between Indigenous Australians and other Australians’16, which led to the establishment of the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (Closing the Gap) in 2008. Through the agreement, the parties committed to working together with Indigenous Australians to close the gap in Indigenous disadvantage. It committed the Australian, state and territory governments to a detailed framework of Closing the Gap objectives, outcomes, outputs, performance measures and targets. The National Indigenous Reform Agreement contained six targets, one of which one of which was reframed in 2015 after expiring in 2013, and COAG committed to another target in 2014. The seven Closing the Gap targets are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Closing the Gap targets

|

Closing the Gap targets |

Target year |

On track/not on track |

|

Close the life expectancy gap within a generation |

2031 |

Not on track |

|

Halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five within a decade |

2018 |

Not on track |

|

Halve the gap for Indigenous students in reading, writing and numeracy within a decade |

2018 |

Not on track |

|

Halve the gap in Indigenous employment outcomes within a decade |

2018 |

Not on track |

|

Halve the gap for Indigenous people aged 20–24 in Year 12 or equivalent attainment rates by 2020 |

2020 |

On track |

|

Close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous school attendance within five years |

2018 |

Not on track |

|

95 per cent of all Indigenous four-year-olds enrolled in early childhood education by 2025a |

2025 |

On track |

Note a: The target was reframed in 2015 following the expiry of the previous remote early childhood education target.

Source: COAG Communiques and Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2020.

1.10 The gap in outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Australia has been reported in twelve successive Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s reports. The Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2020 reported that, while there has been progress, only two of the seven Closing the Gap targets are on track to be met — early childhood education and Year 12 attainment.17 The other five targets are not on track.

1.11 In 2019 the ANAO examined the Closing the Gap framework. The audit concluded that: arrangements for monitoring, evaluating and reporting progress towards Closing the Gap had been partially effective; and reporting on the high-level Closing the Gap targets had been maintained, but little work had been undertaken to monitor and evaluate the contribution of Australian Government programs towards achieving these targets.18

1.12 In late 2016 COAG announced a refresh of the Closing the Gap framework. A partnership agreement between COAG and the National Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations came into effect in March 2019, creating a Joint Council on Closing the Gap. In July 2020 the Joint Council met to discuss the details of the draft National Agreement on Closing the Gap, which identifies priority reforms and includes new accountability measures. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap was released on 30 July 2020.

COVID-19 pandemic measures for Indigenous Advancement Strategy funded organisations

1.13 On 2 April 2020 the Minister for Indigenous Australians announced a number of targeted COVID-19 measures to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, including $38 million to enhance the delivery of critical social support programs delivered under the IAS (including alcohol and other drug services, social and emotional wellbeing projects, family support and youth engagement, community safety and school nutrition).

1.14 Modified arrangements for grants administered under the IAS were also established temporarily. These included adopting a flexible approach to ensure that funded organisations are supported and remain viable during the COVID-19 pandemic. To this effect, on 30 March 2020 NIAA wrote to IAS funded organisations offering the opportunity to discuss available options. For organisations concerned about their ability to deliver services consistent with their grant agreements, the options included a review of their funding agreement.

Rationale for undertaking the audits

1.15 The IAS is one of the means through which the Australian Government has been trying to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Among the six IAS programs, the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs have the second and third largest administered budgets respectively. ANAO performance audits19, as well as Parliamentary inquiries20 and departmental reviews, have shown that there have been shortcomings in the administration of the IAS. Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 Indigenous Advancement Strategy concluded that the ‘department’s grants administration processes fell short of the standard required to effectively manage a billion dollars of Commonwealth resources’. This report discusses NIAA’s progress in implementing relevant recommendations from Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 and provides assurance to Parliament and the public about the effectiveness of the administration of the IAS, focusing on the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The ANAO conducted separate audits of the IAS Children and Schooling program and the IAS Safety and Wellbeing program, the findings and conclusions of which are presented in this report. The objective of the audits was to assess the effectiveness of PM&C’s and NIAA’s administration of the IAS Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective of the audits, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Have the programs been designed and implemented to support the Government’s objectives?

- Are grant assessments consistent with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) and program guidelines?

- Is the management of grants consistent with the CGRGs and program guidelines?

- Does the performance framework support the effective administration of grants and enable ongoing assessment of progress towards outcomes?

Audit methodology

1.18 The audit methodology included:

- examination of PM&C and NIAA documentation about the design and implementation of the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs;

- analysis of system data for 257 Children and Schooling and 237 Safety and Wellbeing grant applications submitted between 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2019, excluding applications that were withdrawn or under assessment as at 16 September 2019;

- analysis of documentation relating to a sample of 67 Children and Schooling and 65 Safety and Wellbeing grant applications submitted and assessed between 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2019;

- interviews with:

- PM&C and NIAA personnel in National Office and in the Regional Network in Eastern New South Wales, Victoria/Tasmania, South Australia, Greater Western Australia, Kimberley, Central Australia, Top End and Tiwi Islands and Far North Queensland; and

- 38 grant recipients in all states and territories around Australia;

- analysis of feedback from 132 recipients of grants under the Children and Schooling program, the Safety and Wellbeing program, or both programs.

1.19 The audit of the IAS Children and Schooling was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $495,000. The audit of the IAS Safety and Wellbeing was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $656,000.

1.20 The team members for these audits were Dr Isabelle Favre, Natalie Maras, Hugh Balgarnie, Clarina Harding, Elizabeth Robinson and Deborah Jackson.

2. Program design and implementation

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs were designed and implemented to support the Australian Government’s objectives.

Conclusion

The Children and Schooling program was designed and implemented to support the Australian Government’s objectives for improved education. The Safety and Wellbeing program was largely designed and implemented to support the Australian Government’s objectives for healthier and safer homes and communities. For both programs, the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) Grant Guidelines are compliant with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs), but are not consistent with Department of Finance’s guidance relating to communication about program funding availability.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving communication about the availability of funding for each of the two programs.

2.1 The CGRGs establish the overarching Commonwealth grants policy framework and articulate expectations for all non-corporate Commonwealth entities in relation to grants administration. ‘Robust planning and design’ is one of the CGRG’s seven key principles for better practice grants administration that apply to all grant opportunities.21

2.2 To assess whether the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs were designed and implemented to support the Australian Government’s objectives, the ANAO examined whether:

- the objectives of the programs align with government objectives;

- effective governance arrangements have been established;

- fit-for-purpose systems support staff to assess and manage grants; and

- the IAS Grant Guidelines are consistent with the CGRGs.

Are the objectives of the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs aligned with government objectives?

The objectives of the Children and Schooling program align with Australian Government policy objectives for improved educational outcomes for Indigenous Australians. The objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing program broadly align with Australian Government policy objectives of healthy homes and safe communities for Indigenous Australians. The development of a policy and investment framework in 2019 has the potential to strengthen the coordination and strategic direction of the IAS, including the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs.

2.3 The CGRGs state that:

The objective of grants administration is to promote proper use and management of public resources through collaboration with government and non-government stakeholders to achieve government policy outcomes.22

2.4 The IAS is a key program for achieving the government’s three priorities to improve outcomes for Indigenous Australians:

- education;

- employment, economic participation and social participation; and

- a healthy and safe home and community.23

2.5 Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 Indigenous Advancement Strategy noted that the Australian Government’s areas for priority investment in Indigenous affairs broadly aligned with the IAS programs.24

Children and Schooling program

2.6 When established, the objectives of the Children and Schooling program, as outlined in the 2014 IAS Grant Guidelines, were:

To support families to give children a good start in life through improved early childhood development, care, education and school readiness; get children to school, improve literacy and numeracy, and support successful youth transition to further education and work.25

2.7 These objectives are consistent with the government’s priorities and the objectives of the program outlined in the 2014–15 Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s (PM&C’s) Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS). The 2014–15 PBS states that the objectives of the program are to: get children to school, improve education outcomes and support families to give children a good start in life. The objectives are described in the same way in PM&C’s 2015–19 corporate plan and have remained consistent in subsequent IAS guidelines and budget statements.

2.8 As discussed in paragraph 1.9, in 2006 the Australian Government agreed to an intergovernmental approach to closing the gap in Indigenous disadvantage. The agreement outlines seven building blocks to support closing the gap as measured by six (then seven) targets (see Table 1.1). The building blocks are: early childhood; schooling; health; economic participation; healthy homes; safe communities; and governance and leadership.

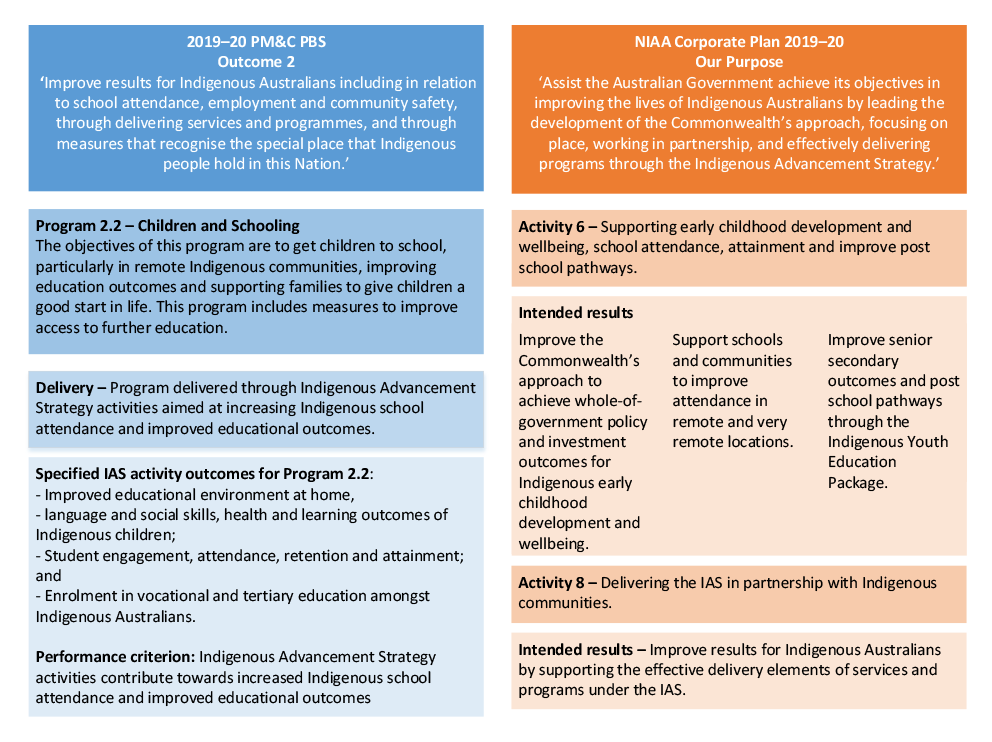

2.9 The objectives of the Children and Schooling program reflect the broader objective of the Closing the Gap framework and are aligned to two of the building blocks (early childhood and schooling). Five of the Closing the Gap targets are closely related to the Children and Schooling program outcomes and objectives. Figure 2.1 demonstrates this alignment, as articulated in the current guidelines and PBS.

Figure 2.1: Alignment of Children and Schooling program with government objectives

|

Relevant Closing the Gap targets |

|

|

Outcome 2: 2019–20 PBS |

Improve results for Indigenous Australians including in relation to school attendance, employment and community safety, through delivering services and programmes, and through measures that recognise the special place that Indigenous people hold in this Nation. |

|

Program objectives, 2019–20 PBS |

The objectives of this program are to get children to school, particularly in remote Indigenous communities, improving education outcomes and supporting families to give children a good start in life. This program includes measures to improve access to further education. |

|

Program objectives and outcomes, 2019 IAS Grant Guidelines |

The objective of the Children and Schooling Programme is to deliver activities to Indigenous children, youth and adults that:

Outcomes:

|

Note: When NIAA was established as an executive agency, Outcome 2 and its related programs transferred from PM&C to NIAA and are now presented as Outcome 1. There have been no other changes to the outcome or program structure since the publication of the 2019–20 PBS.

Source: ANAO analysis based on Closing the Gap targets, PM&C Portfolio Budget Statements 2019–20 and the IAS Grant Guidelines 2019.

2.10 The 2014 IAS Grant Guidelines stated that the strategy was designed to be broad in scope and flexible enough to support a wide range of activities. This has made it possible for NIAA to fund a broad range of activities under the Children and Schooling program, which align to the program objectives and the Closing the Gap targets.

Safety and Wellbeing program

2.11 When established, the objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing program, as outlined in the 2014 IAS Grant Guidelines, were:

To ensure the ordinary rule of law applies in Indigenous communities, and to ensure Indigenous people enjoy similar levels of physical, emotional and social wellbeing enjoyed by other Australians by fostering the ability of Indigenous Australians to engage in education, employment and other opportunities.26

2.12 These objectives are consistent with the objectives of the program outlined in the 2014–15 PM&C’s PBS. The 2014–15 PBS states that the objectives of the program are to: ensure that the ordinary law of the land applies in Indigenous communities; and ensure Indigenous people enjoy similar levels of physical, emotional and social wellbeing enjoyed by other Australians. The objectives are described in the same way in PM&C’s 2015–19 corporate plan, and have remained consistent in subsequent IAS Guidelines and budget statements.

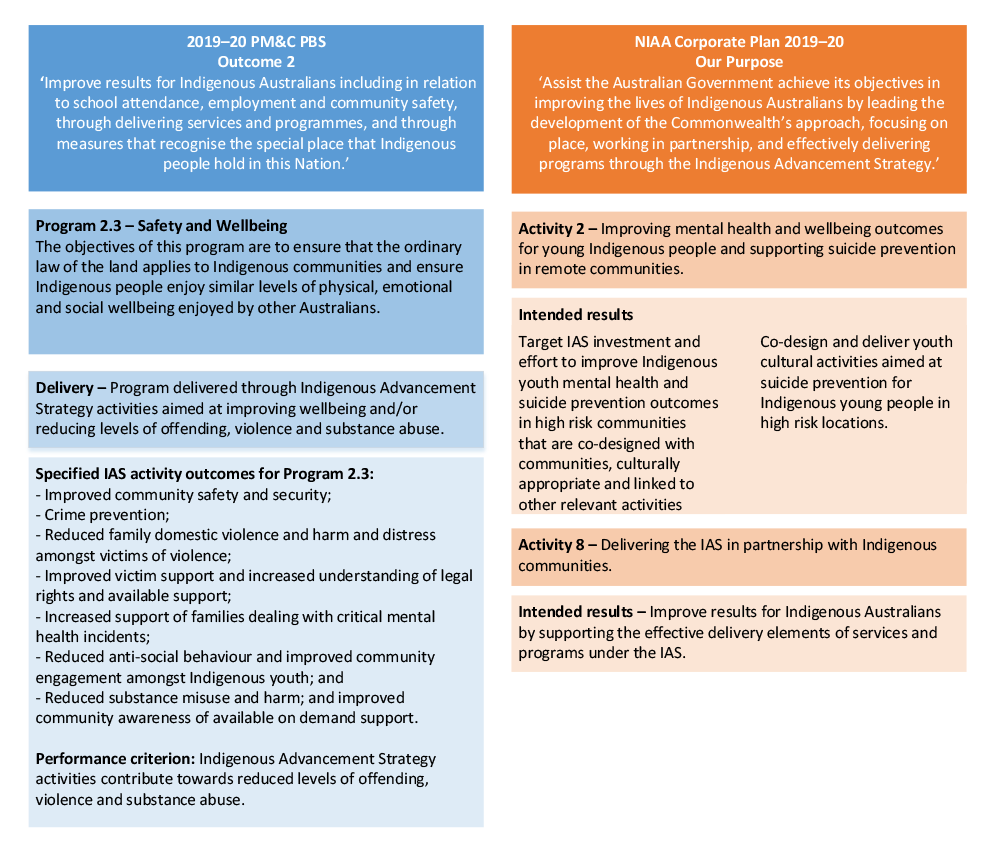

2.13 The objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing program reflect the broader objective of the Closing the Gap framework and are aligned to two of the building blocks referred to in paragraph 2.8 (healthy homes and safe communities). Two of the Closing the Gap targets are related to the program outcomes and objectives. Figure 2.2 demonstrates this alignment, as articulated in the current guidelines and PBS.

2.14 The Safety and Wellbeing program objectives also include elements that are broader than the Closing the Gap building blocks. For example, physical, emotional and social wellbeing (Safety and Wellbeing program) encompasses a broader range of issues than healthy homes and safe communities (Closing the Gap). This has resulted in the funding of a large range of activities.

Figure 2.2: Alignment of Safety and Wellbeing program with government objectives

|

Relevant Closing the Gap targets |

|

|

Outcome 2: Indigenous, 2019–20 PBS |

Improve results for Indigenous Australians including in relation to school attendance, employment and community safety, through delivering services and programmes, and through measures that recognise the special place that Indigenous people hold in this Nation. |

|

Program objectives, 2019–20 PBS |

The objectives of this program are to ensure that the ordinary law of the land applies to Indigenous communities and ensure Indigenous people enjoy similar levels of physical, emotional and social wellbeing enjoyed by other Australians |

|

Program objectives and outcomes, 2019 IAS Grant Guidelines |

The objectives of the Safety and Wellbeing Programme are to:

Outcomes:

|

Note: When NIAA was established, Outcome 2 and its related programs transferred from PM&C to NIAA and are now presented as Outcome 1. There have been no other changes to the outcome or program structure since the publication of the 2019–20 PBS.

Source: ANAO analysis based on Closing the Gap targets, PM&C PBS 2019–20 and the IAS Grant Guidelines 2019.

Recent changes to the Indigenous Advancement Strategy strategic direction: the Indigenous Policy and Investment Framework

2.15 In December 2018 PM&C commissioned a strategic review of the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs. The purpose of the review was to develop ‘policy architecture’ for the two programs that could guide future evidence-based program design and strategic decision-making. The review was completed in June 2019. It presents three theories of change for each program.27 The theories of change provide a map of where investment decisions, including grant allocation, should be made to increase assurance that policy objectives of a program are met and expected results achieved.

2.16 The ANAO found that there is alignment between the proposed theories of change for each program and the 2019–20 PM&C PBS objectives and activity outcomes, and to the relevant Closing the Gap targets.

2.17 The theories of change were tested in a subset of the Children and Schooling program in July–August 2019. In November 2019, NIAA advised the ANAO that the review had been expanded to encompass all IAS programs, including the Children and Schooling in its entirety and the Safety and Wellbeing program, with the aim of developing an entity-wide organising framework: the Indigenous Policy and Investment Framework. This framework comprises 12 evidence-based theories of change aligned to the Closing the Gap draft outcome areas. In February 2020, NIAA executive endorsed the following key implementation steps:

- gaining support across Commonwealth agencies to use the framework to coordinate and guide policy and investment priorities across government;

- implementing the framework at the regional level, with an initial focus on IAS investment, with a view to develop a regional approach to investment that is guided by national priorities and shaped by the local context, community-identified needs, and local solutions; and

- developing a performance, monitoring and evaluation framework to enable NIAA and Commonwealth agencies to assess the impact of investments and inform decision-making around investment.

2.18 The Indigenous Policy and Investment Framework aims to realign policies, investments and evaluations to better deliver on the Government’s Closing the Gap goals across NIAA and across government. It is presented by NIAA as ‘a critical mechanism for NIAA to deliver on its mandated role to lead, coordinate and advance a whole-of-government approach for Indigenous Australians and deliver on the Commonwealth’s commitments under Closing the Gap.’28 NIAA informed the ANAO that it expects to finalise the Indigenous Policy and Investment Framework in tandem with the refreshed Closing the Gap National Partnership Agreement and its implementation plans.

2.19 Five years after the start of the IAS, this foundational work has the potential to provide a stronger strategic direction to the programs’ investments. Using theories of change more clearly links activities to intended outcomes, which in turn better informs where investment should be directed.

Have appropriate governance arrangements been established?

Appropriate governance arrangements have been established. Although the two key governance boards did not meet as regularly as scheduled during 2018 and 2019, evidence exists that they provided strategic and operational direction to the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs.

2.20 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) an accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must govern the entity in a way that promotes the: proper use and management of public resources for which the authority is responsible; achievement of the purposes of the entity; and financial sustainability of the entity.29 To ensure compliance with the PGPA Act, it is important for entities to establish effective governance arrangements. The Commonwealth Governance Structures Policy supports creating and maintaining fit-for-purpose governance structures for government activities.30

2.21 The current IAS governance structure is illustrated in Figure 2.3. The structure, and the roles and responsibilities of NIAA’s bodies, are largely similar to PM&C’s governance arrangements when PM&C was responsible for the IAS.

Figure 2.3: NIAA internal governance structure

Note: Yellow shading indicates governance bodies with responsibility for IAS program performance.

Source: ANAO based on NIAA documents.

2.22 The Executive Board, which meets monthly, was ‘the primary executive decision-making body with a focus on strategic planning and policy, culture, organisational performance, resource allocation, risk management, staff management and workplace safety’.31

2.23 The Policy and Delivery Committee was created and met for the first time on 28 November 2019. Its role is helping to ‘drive and operationalise the strategic agenda of the NIAA through improved oversight of our policy, and implementation and delivery activities, ensuring they are aligned with government priorities.’32

2.24 The Program Performance Committee’s purpose is to enable senior management oversight of the IAS. Until March 2020 the Program Performance Committee was referred to as the Program Management Board. Prior to the establishment of the Policy and Delivery Committee, the Program Management Board was a sub-committee of the Executive Board.

2.25 The Program Management Board’s role included ‘making decisions and providing advice to programme owners and the Executive on the strategic directions and implementation of Indigenous-specific programmes, in particular the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS)’.33 The Program Management Board’s responsibilities also included providing oversight regarding funding decisions; ensuring that adequate planning and resources are in place to manage the IAS program workload; driving continuous improvement and innovation; ensuring that program design, implementation and delivery is consistent with NIAA policies; and providing updates to the Executive Board. Program Management Board meetings were intended to be conducted every three weeks since September 2017 (every four weeks before this date).

2.26 To assess the effectiveness of the Executive Board’s and the Program Management Board’s oversight of the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs, the ANAO examined the meeting minutes for the two boards between January 2017 and December 2019.

2.27 The Executive Board met quorum and meeting frequencies for the majority of 2017 (with one exception in December). The Board did not meet in February, March, May, June and December 2018; or in January or April 2019. When it did meet, the Executive Board discussed funding, reform, risk and policy priorities, consistent with its terms of reference.

2.28 The Program Management Board also did not meet as regularly as scheduled. The Board discussed the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs at almost all meetings until August 2018. Between September 2018 and December 2019 the programs were mentioned in only three meeting minutes and were not specifically mentioned between April to December 2019. ANAO analysis indicates that while the programs were not specifically named in all minutes, the PMB did discuss strategic and operational IAS issues that could directly affect programs, including the development of the Policy and Investment Framework, the new IAS Grant Guidelines and the IAS Evaluation and Performance Framework.

Are systems to support staff to assess and manage grants fit-for-purpose?

Until 2019 there were weaknesses in systems to support staff to assess and manage grants that NIAA has worked to address. As a result, systems are now largely fit-for-purpose, although mandatory grants administration training was still in the pilot stage in April 2020.

2.29 Technology, processes and people are key components underpinning successful program administration. The ANAO examined the grant assessment and management systems used to manage the grant programs, as well as guidance and training available to staff.

Grant assessment and management systems

2.30 The two main information technology (IT) systems that NIAA uses to assess and manage IAS grants are the Grants Processing System (GPS)34 and FUSION. GPS, the primary system used, is an online application that is administered by the Community Grants Hub.35 GPS functionality includes:

- standard grants functionality to support block funding and some individualised funding;

- grants rounds and application assessment;

- review functionality for reporting; and

- grant agreement creation and management including financial commitment recording and payment processing.36

2.31 There are three Community Grants Hub packages under which the Hub provides services to manage parts of the grant lifecycle. NIAA’s current service agreement is for a Basic Package, which gives NIAA access to the GPS Digital Platform, helpdesk support and limited reporting.37

2.32 To complement GPS, NIAA uses FUSION to record Indigeneity, record activity coding, create and assess ceasing activities38 and to generate reports. FUSION (previously known as the Indigenous Reporting Tool) was initially established to unify grant information from a number of grant management systems. One of the primary functions of FUSION is to provide end-to-end reporting of a single grant from initial proposal, application assessment, activity management, performance reporting and Ceasing Activity Assessments.

2.33 Figure 2.4 shows the systems used at different stages of the grant assessment and management process.

Figure 2.4: IAS grant administration systems

Note: PDMS is the Parliamentary Document Management System, which stores all parliamentary documentation and executive briefings for the agency. After NIAA was established, relevant PDMS records were migrated to NIAA and allocated a new PDMS identification number.

Source: ANAO analysis based on NIAA documents.

2.34 During the audit the ANAO identified a number of issues that resulted from NIAA’s use of two systems to assess and manage grants. While NIAA has recently worked to address these issues, they impacted on the administration of the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs between 2016 and 2019. The issues identified included interface issues between GPS and FUSION that required manual intervention to resolve.

2.35 Under the Partnership Agreement between NIAA and the Department of Social Services, NIAA has access to a standard suite of reports generated on data held in GPS. In addition, since January 2019 NIAA has started to implement reporting solutions specific to its grant administration business requirements, accessing data stored in FUSION (including GPS data uploaded regularly into FUSION) and additional datasets as required. NIAA’s reporting solutions have allowed the development of automated weekly grant administration reports that are delivered weekly to NIAA executives since December 2019 and regional summary reports delivered to regional mailboxes since March 2020. Reporting to NIAA’s executive is further considered in paragraphs 5.29 to 5.31.

Guidance

2.36 NIAA has developed policies, procedures and resources for the IAS based on the PM&C grants management framework and the Commonwealth Grants Policy Framework. Where there is not a specific NIAA policy, the relevant PM&C policies apply until they are replaced by an agreed NIAA policy. The main source of guidance provided to staff to assist them to assess and manage grants is the online Grants Administration Manual. Other sources of guidance include: GPS systems guidance and intranet resources available through a SharePoint. The IAS Grant Guidelines are also a key policy document and are examined in paragraphs 2.45 to 2.51.

Grants Administration Manual

2.37 NIAA maintains a Grants Administration Manual to guide staff in the administration of grants. Available on NIAA’s intranet, it steps staff through the five stages of the grant management cycle (design, select, establish, manage, and evaluate and improve). Links are provided to relevant guidance and templates supporting each stage. Specific sections address the key areas of risk outlined in the CGRGs. The resources available from the Grants Administration Manual are updated periodically. Overall, the manual is clear, detailed and comprehensive.

2.38 In five of the eight regional network offices visited by the ANAO, NIAA staff indicated that the manual is useful but that it can be difficult to navigate the abundance of material it contains and identify whether the material available is current. In November 2019 NIAA commenced a project to redesign the Grants Administration Manual to improve its useability, content and maintenance. The project is scheduled to be completed in the second half of 2020.

Grants Processing System guidance and the Grants Systems Support and Reporting SharePoint

2.39 GPS task cards help users understand and perform different functions and include business rules and data conventions. The 120 task cards, managed and maintained by the Community Grants Hub under the standard service offer, are in various stages of revision, with some (for example, task cards for the ‘Select’ stage) yet to be updated to reflect current processes in GPS.

2.40 NIAA has also implemented a Grants Systems Support and Reporting web-based collaborative platform (SharePoint) that is designed to achieve consistency in assessment and management and help new users navigate GPS and perform different functions. The Grants Systems Support and Reporting SharePoint has three main parts:

- Grants Systems Support — helps set up and change user profiles and escalate systems issues to the Community Grants Hub;

- Grants System Training — contains task cards, links to e-learning modules and access to instructor-led training (such as ‘bite-sized’ training and webinars); and

- Grants Reporting — provides access to a team assisting with development of custom data reports.

2.41 The platform is an effective way of providing users with technical support contacts and links to detailed operational guidance. As the same information is available in the Grants Administration Manual and the Sharepoint, there may be merit in linking the systems (so that each system refers to the other where relevant).

Training

2.42 Staff training is fundamental to an entity-wide culture of quality and consistency in the assessment and management of grants. Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 Indigenous Advancement Strategy reported that PM&C was unable to provide a training register or other documentation recording which staff had attended training. In 2017, following the Auditor-General’s report, Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit Report 464: Commonwealth Grants Administration recommended that PM&C measures the number of staff formally trained with regard to the CGRGs and quickly rectify skills gaps so as to ensure compliance with CGRGs.39 In response to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, PM&C advised that it had developed a ‘comprehensive staff training package aligned with the Grant Administration Manual’, including elements of core training mandatory for staff working in grants administration, and that improved records were being maintained of staff attendance at training sessions.40

2.43 Between August and September 2019 NIAA introduced a mandatory cloud-based Learning Management System, which can measure the number of staff completing training. Through the Learning Management System, NIAA piloted grants administration training consisting of five interactive modules explaining obligations under the PGPA Act and the CGRGs. The training also outlined the key steps of the grant lifecycle, including key grants administration processes and responsibilities. In April 2020 NIAA advised that of the 963 staff included in the initial pilot of the training, 86 per cent completed the training.41

2.44 NIAA also offers face-to-face and video conference training, provided annually or as needed, for example where staff in a region routinely omit information from one of the key fields in GPS. Training includes acquittals, organisation and activity risk management, grants advice, Working with Vulnerable People guidance, performance reporting, fraud awareness and the centralised briefing process. A helpdesk providing support with grant systems is also available to NIAA staff.

Are the IAS Grant Guidelines consistent with the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines?

The IAS Grant Guidelines are compliant with the CGRGs but NIAA’s communication about the programs’ funding availability is not transparent, which is inconsistent with Department of Finance guidance.

2.45 The CGRGs emphasise the importance of promoting open, transparent and equitable access to grants, including through ensuring that the rules of grant opportunity guidelines are clear in their intent.42 The CGRGs note that the rules of grant opportunities should be simply expressed, clear in their intent and effectively communicated to stakeholders.43

2.46 The IAS Grant Guidelines were published in 2014, revised in 2016 and updated in August 2019 to reflect the transfer from PM&C to NIAA. They include a description of program objectives, eligibility and assessment criteria, assessment process, grant agreement requirements and monitoring and evaluation approaches. The guidelines contain a comprehensive description of the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs, including activities that are in-scope and out-of-scope for funding. They also present the three approaches that NIAA uses to allocate funding under the IAS (summarised in Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Funding approaches in the IAS Grant Guidelines

|

Approach |

Method |

|

Agency invites applications |

Used when NIAA identifies a specific need. Opportunities are advertised. Applications are required (can be an application kit provided by NIAA, including in the form of a letter or an email). Assessed against the guidelines’ criteria. Can be competitive (applications compared against each other) or non-competitive (applications assessed on a case-by-case basis). Can be open to all applicants or targeted to a particular group of applicants, location or activities. |

|

Agency responds to community led proposals |

Used at any time when a community, individual or organisation is seeking funding to respond to an emerging community need or opportunity. Two steps to submit a proposal:

However, organisations may submit an application regardless of whether an initial proposal has been submitted; and whether NIAA’s advice was favourable. Assessed against the guidelines’ criteria. |

|

Agency approaches organisation |

Used when NIAA identifies a specific need. NIAA directly approaches organisations to negotiate delivery of an activity or service. Organisation may not have to complete an application form, but NIAA may request information needed to assess organisation against eligibility and assessment criteria. Assessed against the guidelines’ criteria. A simplified assessment process may be used, particularly where the organisation already receives IAS funding. Can include existing grant recipients approached to expand their services and new providers. |

Source: ANAO analysis, based on the IAS Grant Guidelines 2019.

2.47 As required by the CGRGs, the guidelines are available on NIAA’s website (previously on PM&C website) and are supplemented, when relevant, by an application kit. In accordance with the CGRGs, grant opportunities have been listed on GrantConnect since 2017, with links to the IAS Grant Guidelines and the responsible entity’s website.44 The information provided on GrantConnect is consistent with the information provided on the website(s).

2.48 The ANAO’s analysis found that the IAS Grant Guidelines, in conjunction with the application kits, include most of the information that the Department of Finance recommends should be present in grant guidelines45 and, to that extent, are compliant with the CGRGs. The CGRGs do not require entities to publish the amount of funding available. However guidance from the Department of Finance advises that grant guidelines should outline the total funding available over a period of time, how much funding is available for each grant and whether there are limitations on the amount that can be applied for.46

2.49 The IAS Grant Guidelines only indicate the overall IAS budget ($5.2 billion over four years to 2022–23), which does not provide sufficient information on the amount of funding available for a specific program, or whether there are limitations on the amount for which applicants can apply.47 As shown in Table 2.2, there is a material difference between the budget allocated to the IAS; the budget allocated to the Children and Schooling and the Safety and Wellbeing programs; and the uncommitted budget available for each program at any point in time.

Table 2.2: Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs’ budgets

|

|

Children and Schooling |

Safety and Wellbeing |

|

IAS budget over four years to 2022–23 ‘for grant funding processes and administered procurement activities that address the objectives of the IAS’a |

$5.2 billion |

|

|

2019–20 program budgetb |

$305.0 million |

$279.9 million |

|

Uncommitted budget available as at 31 March 2020c |

$8.6 million |

$3.4 million |

Note a: IAS Grant Guidelines 2019, p. 6.

Note b: PM&C 2019–20 Portfolio Budget Statements. The budgets for the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs are for administered expenses.

Note c: The uncommitted budget is the amount of funding available once legal commitments and planned allocations are subtracted.

Source: ANAO, based on NIAA documents.

2.50 Auditor-General Report No.35 2016–17 Indigenous Advancement Strategy also found that the IAS Grant Guidelines and the grant application process could have been improved by identifying the amount of funding available under the grant funding round.48

2.51 The ANAO has made a recommendation that, to assist applicants to appropriately scope activities relative to funding available and to increase transparency in relation to the limitations on the amounts that can be applied for, NIAA publicly communicate up-to-date information about funding available under the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs (Recommendation no. 1).

New IAS guidelines

2.52 NIAA advised that new guidelines were being developed, with an expected publication date of December 2020. Instead of one overarching set of IAS guidelines, two sets of ‘agency collaborates’ guidelines would be developed:

- ‘agency collaborates’ guidelines — non-competitive — to fund a proposal that has been developed with an eligible applicant (current community led approach) and to directly approach an organisation, where an approach to market cannot be undertaken;

- ‘agency collaborates’ guidelines — competitive — to approach a group of potential grantees to select the best provider, for example where a critical service gap exists but the most suitable provider needs to be identified.49

2.53 In addition, dedicated program-specific guidelines for each IAS grant opportunity would be issued.

2.54 Drafts reviewed by the ANAO indicate that the two sets of ‘agency collaborates’ guidelines include only the total funding envelope ($5.2 billion over four years to 2022–23). NIAA advised that guidelines developed for dedicated grant opportunities would provide increased transparency regarding funding available, by publishing the amount of uncommitted (available) funds for each opportunity.50

Recommendation no.1

2.55 The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensures that up-to-date information about grant funding available for the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs is publicly available.

National Indigenous Australians Agency’s response: Agree.

2.56 Consistent with the Department of Finance better practice checklist, the National Indigenous Australians Agency (the Agency) currently publishes:

- total funding allocated to the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) in the IAS Grant Guidelines;

- program level funding in the Agency’s Portfolio Budget Statements; and

- funding available under specific grant opportunities in the relevant application kits or program-specific grant opportunity guidelines.

2.57 The Agency recognises the effort involved in developing grant applications and encourages all applicants applying for funding under the community led stream to contact their local Regional Office to discuss funding proposals. This is a key part of the Agency’s approach to working in partnership with Indigenous communities to deliver local and culturally appropriate services.

2.58 Early engagement with applicants assists in the lodging of grant applications which are consistent with the IAS Grant Guidelines and align with the government’s priorities. The availability of funding is just one factor that may be considered as part of these conversations.

2.59 Going forward the Agency will continue to examine ways to publish further information about funding availability under each IAS program to optimise transparency. In light of this, the details of all grant opportunities will continue to be published on GrantConnect and the Agency’s website.

3. Grants assessment

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the National Indigenous Australians Agency’s (NIAA’s) processes to assess Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing grants are compliant with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) and the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) Grant Guidelines.

Conclusion

Assessments are compliant with the CGRGs and the IAS Grant Guidelines for both programs, but are not consistent with the principles underlying the CGRGs to achieve value with relevant money — between July 2016 and June 2019 a large majority of Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing grant funding was allocated using a non-competitive approach and grants were reallocated to the same providers. NIAA has arrangements in place to ensure that regional priorities and potential gaps and duplications in service delivery are considered. Since 2018–19 NIAA has improved its timeliness in assessing applications.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at ensuring grants assessments achieve value with relevant money and are consistent with the CGRGs. The ANAO also noted that there would be merit in documenting how additional factors considered during the assessment process impact the scoring against the four criteria published in the guidelines.

3.1 The concept of transparency in grants administration underpins the CGRGs. Transparency: provides assurance that grants administration is appropriate and that legislative obligations and policy commitments are met; minimises concerns about equitable treatment; and provides assurance that relevant money has been spent for the approved purposes and is achieving the best possible outcomes.51

3.2 The ANAO analysed whether:

- selection processes are applied in a manner that demonstrates the achievement of value for money outcomes;

- grant assessments are compliant with the CGRGs and the IAS Grant Guidelines;

- grant assessments consider regional strategies, and potential gaps and duplications; and

- advice provided to the minister complied with the requirements of the CGRGs.

Are selection processes applied in a manner that demonstrates the achievement of value for money outcomes?

Selection processes are not applied in a manner that demonstrates that a value for money outcome has been achieved. Between July 2016 to June 2019, 90 per cent of the Children and Schooling program funding and 95 per cent of the Safety and Wellbeing program funding was allocated on a non-competitive basis. This is inconsistent with the principles of the CGRGs and with NIAA’s guidance. Also 80 per cent of the Children and Schooling program funding and 87 per cent of the Safety and Wellbeing program funding was reallocated to the same providers after assessment.

3.3 The CGRGs allow for a range of approaches for grant selection, including competitive and non-competitive rounds, demand-driven processes and one-off grants to be determined on an ad hoc basis. The CGRGs specify that using a non-competitive approach to allocate grant funding may be appropriate, in particular when the number of service providers is very limited and these providers have a well-established record of delivering the grant activities. However, the CGRGs also state that competitive, merit-based processes can achieve better outcomes and value with relevant money and should be used to allocate grants (unless otherwise agreed).52

3.4 As summarised in Table 2.1, NIAA uses different approaches to allocate funding under the IAS:

- agency invites applications;

- agency responds to community led proposals; and

- agency approaches organisation (also called direct approach); under the direct approach, the IAS Grant Guidelines state that NIAA may also use a simplified assessment process.

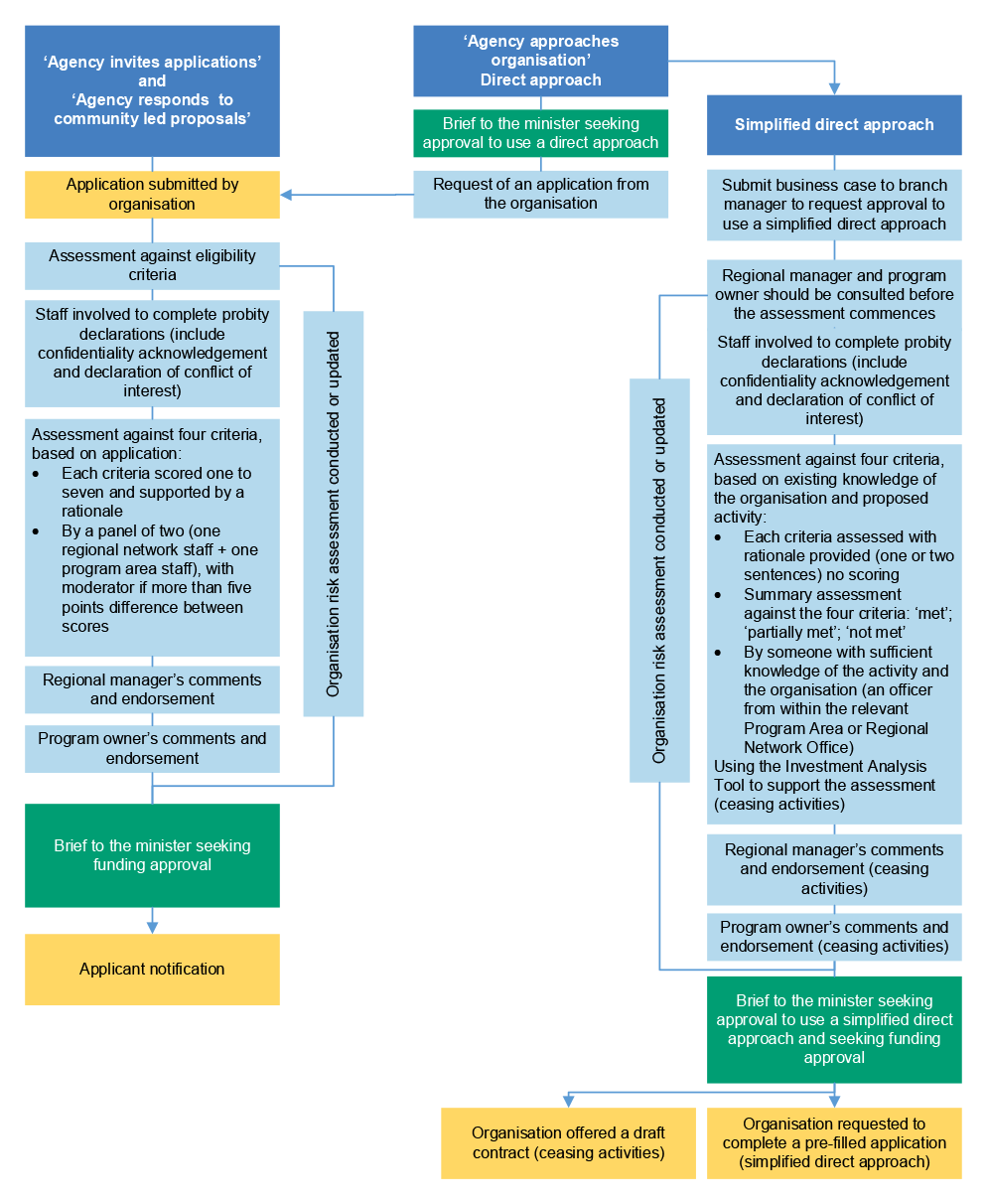

3.5 Figure 3.1 presents NIAA’s grant assessement processes under the three approaches.

Figure 3.1: Grant assessment processes, July 2016 to June 2019

Note: Before June 2019 the minister was the only delegate except for direct approaches under the Regional Managers Discretionary Fund, which allows Regional Managers to fund small scale, short-term, one-off projects.

Source: Based on NIAA documents.

3.6 As illustrated in Figure 3.1, assessments to inform a funding decision follow a similar process under the ‘agency invites applications’ and ‘agency responds to community led proposals’ approaches. Assessment processes differ when the direct approach is used.

3.7 As the direct approach is not competitive and does not assess the relative merits of the applicant, NIAA internal guidance requires that approval to use the approach is obtained from the delegate (the minister) before approaching the organisation. This is in accordance with the CGRGs, which state that where a method, other than a competitive merit-based selection process is to be used, this should be specifically agreed to by a minister or delegate.53 NIAA policy and internal guidance specify that the simplified process is to be used sparingly and as an exception:

[A simplified direct approach] should be used as an exception, as the standard approach in accordance with the CGRGs is to undertake a competitive approach to market…. You must provide a strong business justification to explain why you are not using a competitive approach.54

3.8 In the ministerial briefs seeking approval for the funding approach, the standard justifications PM&C used to support its recommendation for a non-competitive direct approach included that the provider: has extensive experience in effectively delivering activities; has established relationships with key stakeholders; has expressed interest in continuing service provision; does not have a high risk rating; and is the only known provider able to deliver the activities at the time.

3.9 Table 3.1 demonstrates that, between July 2016 and June 2019, PM&C used the non-competitive ‘agency approaches organisation’ direct approach to allocate 90 per cent of the Children and Schooling program funding and 95 per cent of the Safety and Wellbeing program funding.

Table 3.1: Funding distribution by funding approach, July 2016 to June 2019

|

|

Agency invites applications |

Agency responds to community led proposals |

Agency approaches organisation ‘Direct approach’ |

Total |

||||

|

|

$m |

% |

$m |

% |

$m |

% |

$m |

% |

|

Children and Schooling program |

||||||||

|

2016–17 |

– |

0 |

5.64 |

25 |

16.97 |

75 |

22.60 |

100 |

|

2017–18 |

10.00 |

7 |

7.04 |

5 |

122.50 |

88 |

139.54 |

100 |

|

2018–19 |

19.76 |

7 |

4.78 |

2 |

286.80 |

92 |

311.34 |

100 |

|

Total |

29.76 |

7 |

17.46 |

4 |

426.27 |

90 |

473.49 |

100 |

|

Safety and Wellbeing program |

||||||||

|

2016–17 |

– |

– |

3.91 |

4 |

86.06 |

96 |

89.96 |

100 |

|

2017–18 |

– |

– |

15.74 |

5 |

305.13 |

95 |

320.87 |

100 |

|

2018–19 |

– |

– |

14.88 |

5 |

256.03 |

95 |

270.91 |

100 |

|

Total |

– |

– |

34.53 |

5 |

647.22 |

95 |

681.74 |

100 |

Source: ANAO analysis of NIAA data. Some totals do not add up due to rounding.

3.10 As illustrated in Figure 3.1, NIAA also uses a simplified direct approach under the direct approach. NIAA guidance indicates that the simplified direct approach can be used in two circumstances:

- to address urgent needs, for instance to prevent an unexpected service delivery gap; and

- to assess whether to continue or cease activities already funded. These activities are described by NIAA as ‘ceasing activities’.

3.11 Ceasing activities are activities that are due to cease within the next six months and that NIAA assesses in order to decide whether to continue funding the activity beyond the current agreement’s expiry date. In most cases NIAA does not require an application as the organisations that are approached are receiving or have previously received IAS funding to deliver the same or similar activities. NIAA uses the information and knowledge it holds about the organisations’ experience and performance to conduct the assessment. The IAS Grant Guidelines also state that using the simplified assessment process minimises administrative workload on providers. This approach is consistent with the CGRGs.

3.12 Table 3.2 shows that, between 1 July 2016 and 30 June 2019, ceasing activities accounted for 84 per cent of all funding allocated under the Children and Schooling program, and 90 per cent of all funding allocated under the Safety and Wellbeing program.

Table 3.2: Funding allocated through the ‘agency approaches organisation’ approach, July 2016 to June 2019

|

|

Direct approacha |

Ceasing activities |

Total funding (all approaches) |

||

|

|

$m |

% |

$m |

% |

$m |

|

Children and Schooling program |

|||||

|

2016–17 |

4.12 |

18 |

12.85 |

57 |

22.60 |

|

2017–18 |

11.47 |

8 |

111.03 |

80 |

139.54 |

|

2018–19 |

13.14 |

4 |

273.67 |

88 |

311.34 |

|

Total |

28.73 |

6 |

397.54 |

84 |

473.49 |

|

Safety and Wellbeing program |

|||||

|

2016–17 |

2.85 |

3 |

83.21 |

92 |

89.96 |

|

2017–18 |

8.64 |

3 |

296.49 |

92 |

320.87 |

|

2018–19 |

21.77 |

8 |

234.26 |

86 |

270.91 |

|

Total |

33.25 |

5 |

613.96 |

90 |

681.74 |

Note a: The data for funding allocated through the direct approach includes a number of grants allocated using a simplified approach.

Source: ANAO analysis of NIAA data. Some totals do not add up due to rounding.

3.13 The ceasing activities assessment process can result in a range of outcomes:

- activity ceases: due to the activity being completed without expectation of further funding or capacity to continue (for instance, construction of a building or attendance to a conference); or due to changing community needs or poor performance, governance issues or other risk factors related to the provider;

- activity continues with the same provider: delivering the same activity without substantial change (under the same agreement and schedule); or with some changes to the nature or scope of the activity or key performance indicators (under the same agreement with a new schedule); and

- activities continue with a new provider: the same activity is transitioned to a new provider either as soon as the existing provider’s agreement is completed or over a specific period.

3.14 Between 1 July 2016 and 30 June 2019, the ceasing activities assessment process resulted in the activities being continued for 80 per cent of Children and Schooling and 87 per cent of Safety and Wellbeing funding (see Table 3.3). This means that the majority of program funding was reallocated to the same providers delivering mostly the same activities.

Table 3.3: Ceasing activities funding outcomes

|

|

Activity continues same provider |

Activity continues new provider |

||

|

|

$m |

% of total funding |

$m |

% of total funding |

|

Children and Schooling |

||||

|

2016–17 |

12.85 |

57 |

0 |

0 |

|

2017–18 |

105.25 |

75 |

5.78 |

4 |

|

2018–19 |

262.03 |

84 |

11.63 |

4 |

|

Total |

380.13 |

80 |

17.42 |

4 |

|

Safety and Wellbeing |

||||

|

2016–17 |

83.21 |

92 |

0 |

0 |

|

2017–18 |

293.74 |

92 |

2.76 |

1 |

|

2018–19 |

218.68 |

81 |

15.58 |

6 |

|

Total |

595.62 |

87 |

18.34 |

3 |

Source: ANAO analysis, based on NIAA data. Some totals do not add up due to rounding.

3.15 As mentioned at paragraph 3.3, competitive, merit-based selection processes can achieve better outcomes and value with relevant money.55 NIAA allocates the majority of the funding for the Children and Schooling and Safety and Wellbeing programs using a non-competitive approach. This is not consistent with the principles underlying the CGRGS and with NIAA’s policy and guidance (outlined at paragraph 3.7). The extensive use of a non-competitive approach, combined with the allocation of the majority of the programs’ funding to the same providers, restricts the opportunity for new providers to compete for funding and limits NIAA’s ability to demonstrate that value with relevant money is achieved.

Recommendation no.2

3.16 The National Indigenous Australians Agency ensures that its approaches to grants assessment:

- achieves value with relevant money; and

- is consistent with its policy and guidance and with the principles underlying the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines.

National Indigenous Australians Agency’s response: Agree.

3.17 The National Indigenous Australians Agency (the Agency) will continue to undertake grant assessments consistent with the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines 2017 (CGRGs), including an assessment of value for money.