Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Human Services’ Compliance Strategies

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess whether Human Services has an effective high-level compliance strategy for administered payments made under the Centrelink and Medicare programs.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Human Services (Human Services or the department) delivers Centrelink and Medicare payments to the community on behalf of the Australian Government and in accordance with legislation, government and entity policies. The Minister for Human Services, through the department, administers the Human Services (Centrelink) Act 1997 and the Human Services (Medicare) Act 1973, except to the extent the Medicare Act is administered by the Minister for Health.

2. In 2017–18, the department administered $171.9 billion in social and health related payments. Human Services is responsible for managing fraud and compliance programs to protect the integrity of those government outlays. The department’s annual compliance strategies include identifying potential risks to payment accuracy and educating people about their obligations.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) selected Human Services’ compliance strategies for audit because Human Services allocates significant resources each year to its compliance programs and activities for the Centrelink and Medicare programs. In 2017–18, the cost to the department of undertaking some 1.1 million fraud and compliance activities for both programs was about $267 million. This audit assessed whether Human Services had effective high-level strategies in place to support compliance activities for the Centrelink program and the Medicare program for the three years from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to assess whether Human Services has an effective high-level compliance strategy for administered payments made under the Centrelink and Medicare programs.

5. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted two high-level criteria:

- Does a high-level strategy guide a coordinated program of compliance activities?

- Does a high-level strategy support the conduct of compliance activities?

Conclusion

6. Human Services had an effective high-level compliance strategy for administered payments made under the Centrelink program, from 2015–16 to 2017–18, and for the Medicare program in 2016–17 and 2017–18.

7. A high-level strategy provided clear guidance for the department to implement a coordinated program of compliance activities for the Centrelink program from 2015 to 2018. The design of the strategy was well-informed by evidence, risk based, and adequately referenced the entity level risk management and fraud control frameworks. The strategy contained sufficient details about planned resourcing and governance arrangements to support the annual programs of compliance activities that were conducted. The department’s monitoring and reporting on the strategy’s progress each year was adequate at the operational level in the business areas.

8. The design and refinement of a high-level strategy for the Medicare program provided clear guidance for Human Services to undertake a coordinated program of fraud control activities in 2016–17 and 2017–18. Medicare customer compliance activities undertaken by Human Services in 2015–16 were not included in the strategy. After 2015–16, the conduct of the strategy was supported in the next two years by adequate risk management and fraud control frameworks. The strategy in those two years also adequately identified the resourcing required to undertake fraud control activities and regularly monitored and reported on the outcomes from those activities.

Supporting findings

Compliance strategy for Centrelink payments

9. Human Services’ design of the strategy provided clear guidance for the Centrelink program from 2015–16 to 2017–18. The strategy documented a high-level goal, related objectives and risk based activities to support their achievement. The strategy consistently identified the planned business as usual activities and determined that future strategies would also include the planned volumes of activities to be completed for Budget measures.

10. Human Services’ development of the strategy during 2015–16 to 2017–18 was well-informed. Annual reviews of the strategy were based on identifying risks, assessing the controls in place to mitigate the risks, and determining the necessary volumes of activities. The reviews took into account evidence relevant to each step. Human Services consulted with a wide range of internal and external stakeholders to develop the strategy. The consultations were used to inform the department about current and emerging issues, potential treatments, and strategies for conducting compliance activities.

11. The strategy, combined with its supporting documents, contained adequate but high-level references to the department’s risk management and fraud control frameworks. Future strategies could be improved by:

- explicitly stating the connection between the strategy and the department’s risk management and fraud control frameworks; and

- explaining how the planned work, for both compliance and fraud control activities, would contribute to mitigating the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity.

12. Human Services’ strategy for the Centrelink program supports the conduct of and identified the resources required to conduct compliance interventions and fraud control activities from 2015–16 to 2017–18. The delivery of the strategy was supported by other key documents, such as more detailed risk management plans, governance and monitoring frameworks, guidelines and policies.

13. The department’s monitoring and reporting on the strategy’s progress from 2015–16 to 2017–18 was adequate at an operational level. The original and revised compliance activity targets were not achieved in any year indicating that the department would benefit from reviewing its performance targets annually. Aside from fraud control activities, departmental governance committees at the entity level were not provided with dedicated compliance performance reports from 2015–16 to 2017–18. Future public reporting should be expanded for Centrelink compliance activities, which would increase the transparency and accountability of compliance activities and outcomes.

Compliance strategy for Medicare payments

14. The 2015–16 strategy was not updated to include activities for Medicare customer compliance after machinery of government changes were made in 2015.1 In 2016–17 and 2017–18, the strategy was updated and provided clear guidance for the conduct of fraud control activities for Medicare customer compliance. From 2015–16 to 2017–18, no activities were undertaken by Human Services for any of the 17 health and aged care programs that interacted with third party providers, as departmental responsibility was not resolved between Human Services and the Department of Health.

15. Human Services’ development of a strategy for the Medicare program for 2016–17 was well-informed by reviews of past compliance activity, risk assessments and consulting with key stakeholders about fraud control. The strategy included activities for Medicare customer compliance that were developed in 2015–16. The 2016–17 strategy was then continued for 2017–18.

16. The strategy, in 2016–17 and 2017–18, adequately identified Human Services’ enterprise risk management and fraud control frameworks as being relevant to the strategy. Similar to the compliance strategy for the Centrelink program, the strategy for the Medicare program could also have included a more explicit statement connecting the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity and the fraud control activities that were completed in the two-year period.

17. Human Services’ strategy for the Medicare program adequately identified the resources required to conduct fraud control activities for the program in 2016–17 and 2017–18 for customer compliance cases. In 2015–16, activities were not included for customer compliance cases and third party providers were not included in any of the three years.

18. After 2015–16, and the strategy was updated to include customer compliance activities, Human Services adequately monitored and reported on outcomes from the strategy for the next two years. Although, the monitoring and reporting requirements described in the strategy were not fully implemented in practice. The governance arrangements included management and operational level committees that held meetings only some of the time from 2016–17 to 2017–18, and not consistently through both years. The implementation of the strategy was supported by sufficiently detailed monitoring reports that were circulated regularly to the operational areas. The department regularly reported on fraud control activities conducted for the Medicare program to its strategic management committees and in its annual reports.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.61

That Human Services increase its public reporting, starting from 2018–19, of the compliance activities completed each year for the Centrelink program of administered payments.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.16

That, in 2018–19, Human Services:

- finalise its negotiations with the Department of Health about the responsibility for third party provider compliance under the Medicare program;

- confirm the risk profile and adequacy of existing controls for each health and aged care program for which it has responsibility, as part of the planned joint review with the Department of Health; and

- complete sufficient compliance activities to support Human Services’ compliance strategy for Medicare payments for which it has responsibility.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

19. The proposed report was provided to Human Services, which provided a summary response that is set out below. The response from Human Services is provided at Appendix 1. An extract from the proposed report was provided to the Department of Health and the response is provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes the report, and notes the ANAO’s conclusion that an effective high-level compliance strategy for administered payments is already in place. The department considers that implementation of both recommendations will further enhance the department’s overall compliance strategies.

The department agrees with the ANAO’s recommendations, and is committed to providing its partner agencies, the Australian Parliament and the community with transparent information about the department’s performance in delivering its compliance outcomes. The department will review its public reporting on compliance outcomes and based on the review, make any changes to its external reporting on compliance.

The department also acknowledges the ANAO’s finding regarding third party compliance activities for Medicare programmes. The departments of Health and Human Services have convened a working group to review third party compliance arrangements, and has made progress in resolving this issue.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program design

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Human Services is responsible for delivering a range of payments and services to support individuals, families and communities, as well as providers and businesses. Payments and services are delivered by about 33,000 departmental staff.2 In 2017–18, the department administered $171.9 billion in social and health related payments that were delivered on behalf of other Australian Government entities. If a person is not eligible for a payment they have received, the money must be paid back to the Government. In 2017–18, the department raised 2.49 million social welfare debts to the value of $3.17 billion.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.2 The ANAO selected Human Services’ compliance strategies for audit because Human Services allocates significant resources each year to its compliance programs and activities for the Centrelink and Medicare programs. This audit assessed whether Human Services had effective high-level strategies in place to support compliance activities for the Centrelink program and the Medicare program for the three years from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Administered payments for the Centrelink and Medicare programs

1.3 Human Services makes Centrelink payments for seniors, job seekers, families, carers, parents, students, people with disability, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. The department also makes Centrelink payments for people living overseas, and people who need support at times of major change, including following natural disasters.

1.4 The Medicare program includes both health and aged care payments. The payment of health benefits only occurs after a service has been rendered by a registered medical practitioner (provider) to a customer (patient) who is eligible for Medicare benefits. Aged care payments are made to service providers that provide residential care, home care, short term restorative care and transition care.3

1.5 The payments and services delivered by Human Services on behalf of other entities are administered items, which are a component of an administered program with funding that cannot be used at the discretion of the entity for another purpose. Table 1.1 shows the administered payments made by Human Services under the Centrelink (social security and welfare) and Medicare (health and aged care) programs from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Table 1.1: Administered payments, Centrelink and Medicare programs, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

Financial year |

Centrelink program ($billion) |

Medicare program ($billion)a |

|

2015–16 |

115.73 |

55.01 |

|

2016–17 |

114.28 |

58.59 |

|

2017–18 |

112.33 |

59.62 |

|

Total payments |

342.34 |

173.22 |

Note a: The Medicare program includes health and aged care payments made on behalf of the Department of Health and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ annual financial statements.

Payment integrity and compliance activities

1.6 Corporate plans are intended to be the primary planning documents of Commonwealth entities and companies.4 Human Services’ Corporate Plans (2015–16 to 2017–18) outline the strategies the department intended to follow to achieve its objectives and measure success. The high-level corporate plans refer to the department’s activities to protect the integrity and accuracy of the payments it makes by addressing non-compliance and fraud.

1.7 To protect the integrity of the welfare system by minimising risk, Human Services conducts activities to make sure it: ‘pays the right person the right amount through the right program and at the right time’.5 Human Services identifies risks to payment accuracy, educates people about their obligations and applies compliance measures to confirm that the amounts paid are correct. Centrelink customers are obligated to advise Human Services of changes in their circumstances (for example, employment, financial and relationship status) that may affect their payment entitlements. Medicare payments are made after a patient has received a service and payments can be made at the point of service in a medical practice. Human Services collects, collates and organises information to detect and identify possible fraud. Investigations can identify the potential for payment fraud for Medicare claims, for example, online and under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

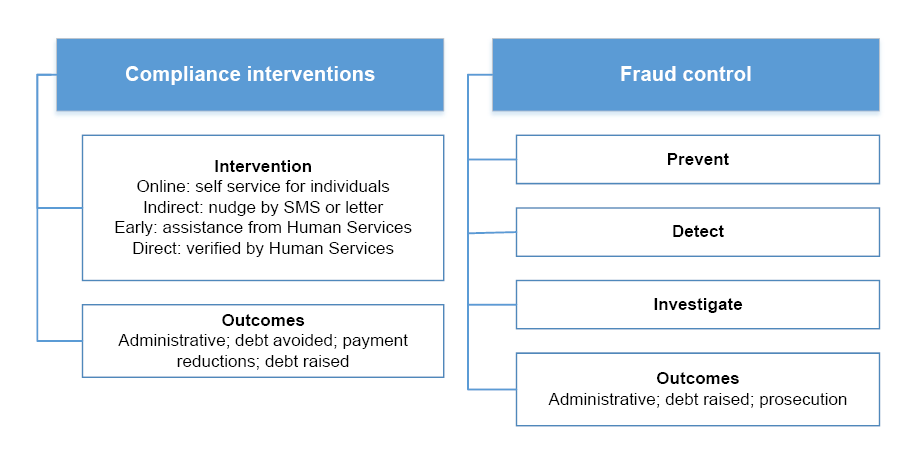

1.8 Human Services investigates non-compliance and potential fraud for payments made under the Centrelink and Medicare programs. Figure 1.1 provides an overview of Human Services’ approach to addressing non-compliance for administered payments. The approach includes: helping people to meet their obligations through educational and behaviour change or ‘nudge’ activities to prevent overpayments or reduce debt, and by investigating potentially fraudulent claims for payments.6 Debts can be raised for overpayments and prosecutions made for fraud.

Figure 1.1: Human Services’ approach to addressing payment non-compliance, 2015–16 to 2017–18

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ documents.

1.9 During 2015–16 to 2017–18 there were separate, high-level strategies to guide the department’s compliance activities for the Centrelink program and for the Medicare program. The strategy for Centrelink included compliance interventions and fraud control activities, while the strategy for Medicare focused solely on the risk of fraud.

1.10 Table 1.2 shows the total number of compliance activities, for Budget measures and business as usual, completed by Human Services for the Centrelink and Medicare programs from 2015–16 to 2017–18. The total number of activities completed for the Centrelink program was about 3.2 million and for the Medicare program was about 2,500. The volumes of activities shows the difference in the potential risk of inaccurate payments through self-reporting of circumstances to receive Centrelink payments compared to claiming for medical costs that have already been paid or billed. Activities to deter fraudulent claims were undertaken for both programs.

Table 1.2: Centrelink and Medicare program compliance activities and departmental direct costs, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

Financial year |

Centrelink program |

Medicare program |

||

|

|

Number of activitiesa |

Departmental direct costs ($million)b |

Number of activitiesa |

Departmental direct costs ($million)b |

|

2015–16 |

990,672c |

171.02 |

1,693 |

27.61d |

|

2016–17 |

1,081,204 |

206.38 |

499 |

9.19 |

|

2017–18 |

1,104,339e |

256.75e |

330 |

9.83e |

|

Total |

3,176,215 |

634.15 |

2,522 |

46.63 |

Note a: The types of activities included preventative and compliance review interventions.

Note b: The direct costs included: compliance review activities; payment review activities; strategic management; project management; and divisional support.

Note c: The total number of activities is different to that reported in Auditor-General Report No.41 2016–17 Management of Selected Fraud Prevention and Compliance Budget Measures (Table 1.1, p. 16). The total in Table 1.2 also includes all Business Integrity business as usual and Budget measure activities, including Taskforce Integrity activities.

Note d: The reduction in costs in later years resulted from a restructuring of administrative arrangements on 30 September 2015, when the department relinquished responsibility for the Medicare provider compliance responsibilities for the Medicare Benefits Scheme, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Allied Health Services to the Department of Health.

Note e: Estimated to 30 June 2018.

Source: Department of Human Services.

1.11 Starting in 2012–13, Human Services implemented a range of fraud prevention and compliance Budget measures related to the Centrelink program.7 The Budget measures that collectively form the department’s Compliance Modernisation Programme are to address new and existing fraud and compliance risks that affect the integrity of the social security system. The Welfare Payment Infrastructure Transformation Programme, being delivered by the department from 2015 to 2022, has the potential to enhance the efficiency of the welfare payment systems and improve the experience of people in the community who interact with government. The planned reforms to payment systems and business processes will also change the future approach to compliance and fraud control activities.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.12 The audit objective was to assess whether Human Services has an effective high-level compliance strategy for administered payments made under the Centrelink and Medicare programs.

1.13 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted two high-level criteria:

- Does a high-level strategy guide a coordinated program of compliance activities?

- Does a high-level strategy support the conduct of compliance activities?

1.14 The audit did not examine:

- debt recovery activities; and

- compliance activities undertaken by other entities for payments made by Human Services, for example, the Department of Health has responsibility for managing health professionals’ compliance and Human Services makes payments to eligible providers.

Audit methodology

1.15 The ANAO examined Human Services’ records for the design and operation of compliance activities, including fraud control activities, for payments made under the Centrelink and Medicare programs from 2015–16 to 2017–18. The ANAO interviewed staff from the department. The ANAO also reviewed meeting papers from Human Services’ strategic governance committees and the Audit Committee for the same period.

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $255,000. The team member for this audit was David Brunoro.

2. Compliance strategy for Centrelink payments

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the design and operation of Human Services’ high-level strategy for conducting compliance activities for the Centrelink program from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Conclusion

A high-level strategy provided clear guidance for the department to implement a coordinated program of compliance activities for the Centrelink program from 2015 to 2018. The design of the strategy was well-informed by evidence, risk based, and adequately referenced the entity level risk management and fraud control frameworks. The strategy contained sufficient details about planned resourcing and governance arrangements to support the annual programs of compliance activities that were conducted. The department’s monitoring and reporting on the strategy’s progress each year was adequate at the operational level in the business areas.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at Human Services increasing the transparency and accountability of its compliance activities for the Centrelink program by increasing public reporting on the annual compliance activities undertaken for the Centrelink program.

The ANAO also suggested the following improvements:

- including measurable quantitative and qualitative indicators of performance in the strategy to support end of year reporting within the department;

- setting realistic annual activity targets; and

- providing dedicated reports about compliance activities undertaken for the Centrelink program to the Audit Committee.

Does the design of the strategy provide clear guidance for the Centrelink program?

Human Services’ design of the strategy provided clear guidance for the Centrelink program from 2015–16 to 2017–18. The strategy documented a high-level goal, related objectives and risk based activities to support their achievement. The strategy consistently identified the planned business as usual activities and determined that future strategies would also include the planned volumes of activities to be completed for Budget measures.

2.1 Human Services’ approach to Centrelink payment recipient compliance from 2015–16 to 2017–18 complemented the department’s broader external fraud control activities.

2.2 The approach was recorded in versions of a Compliance Programme document and an external fraud control Intelligence Plan produced in the period (‘the strategy’). The strategy was supported by other key documents, including governance and monitoring frameworks, guidelines and policies.

2.3 The strategy applied to income support payments made under the following Centrelink benefit programs: Jobseekers; Families; Carers; Disability; Emergency Management; Multicultural Services; Older Australians; and Students. The eight programs are comprised of 36 types of benefits, for example, Age Pension, Family Tax Benefit and Newstart Allowance.

2.4 The overarching goal documented in the strategy was to manage the risks to payment integrity effectively and efficiently. To achieve this goal each year Human Services focused on:

- providing assurance to key external and internal stakeholders that risks to payment integrity and accuracy are being effectively managed;

- ensuring that appropriate types and levels of activity were undertaken to focus on the areas of highest non-compliance and customer error while providing good coverage for all risks;

- identifying and disrupting fraud associated with social and welfare payments; and

- meeting Budget measure requirements and other Government priorities.

2.5 The strategy adequately documented the key features of Human Services’ approach to Centrelink compliance, including: the scope of activity; the strategy development process; specific risks to be addressed; and broader Government and department priorities. The strategy also stated the types of activity that were to be implemented in pursuit of the strategy’s goal and objectives.

2.6 The strategy prescribed targeting planned activities at cross-cutting risks to payment integrity rather than at particular benefit programs or payments. The strategy consistently targeted activities at the following six key risks to payment accuracy, which are customers providing inaccurate personal circumstances information about their:

- earned income;

- unearned income and assets;

- identity, qualification and participation;

- location;

- relationship status; and

- study load.8

2.7 Limited exceptions to the risk based approach to targeting activities occurred where Human Services targeted compliance activity to a specific benefit type. Human Services advised that this approach was applied to: medical eligibility reviews for the Disability Support Pension; and Child Care Benefit linked to the delivery of the former Jobs, Education and Training Child Care Fee Assistance scheme, which ceased on midnight 1 July 2018.

2.8 From 2015–16 to 2017–18, the key Government and departmental influences on the strategy included implementing: the Government’s shift toward digital service delivery; and the department’s Welfare Payment Infrastructure Transformation project. The project was Human Services’ primary business transformation activity over the period.

2.9 Reflecting these influences, the strategy targeted a large majority of planned compliance activities each year at earned income risk.9 Activities were also focused on prompting customers to use digital channels to confirm or correct their information rather than direct staff verification of that information. As part of this approach, in July 2016, Human Services launched an online compliance intervention system. The system matched the earnings recorded on a customer’s Centrelink record with income data from the Australian Taxation Office. The system’s operation attracted significant public attention including the Commonwealth Ombudsman investigating complaints and publishing a report in April 2017: Centrelink’s automated debt raising and recovery system.10

2.10 The Commonwealth Ombudsman concluded as follows:

In February 2017, DHS made changes to the OCI [online compliance intervention] process, partly in response to feedback from this office and complaints made to DHS itself. The changes have been positive and have improved the usability and accessibility of the system … In our view, these changes go some way to addressing the problems identified in this report that occurred in the initial rollout of the OCI. However, we consider there are several areas where further improvements could be made and we have made a number of recommendations to address these. We consider it is important for DHS to address these issues before the OCI is rolled out further, particularly to vulnerable customers.11

2.11 The Commonwealth Ombudsman made eight recommendations. Human Services agreed with all of the recommendations that were made to the department.

Planned activities

2.12 The strategy partially documented activity targets that Human Services could use to track planned versus actual implementation. The strategy documented planned types and levels of activities for the compliance program element of the approach from 2015–16 to 2017–18, and for the fraud control element of the approach in 2015–16. The strategy documented planned types, but not levels, of fraud control activities for 2016–17 and 2017–18.

2.13 Planned activity volumes identified the business as usual activities throughout the three-year period. In June 2018, Human Services determined that the next year’s strategy (2018–19) should also incorporate Budget measure activity volumes, to ensure all compliance activity was represented under each risk category.

2.14 During 2015–16 to 2017–18, the key indicator of success for the strategy was the total number of activities completed (see paragraph 2.35). Associated annual reporting, within the department, also identified outcomes such as savings realised, debt raised and successful prosecutions with the strategy’s activities. The ANAO suggests that future strategies could be improved by identifying measurable indicators of performance in the strategy at the beginning of each year that can be used to report, within the department as well as to the Minister for Human Services and Digital Transformation, on the strategy’s overall effectiveness at the end of the year. The potential indicators could be:

- quantitative indicators for the total number of activities to be completed throughout the year (and for the individual categories of Budget measures and business as usual activities); and

- a qualitative indicator for feedback from key stakeholders about whether the strategy’s performance provides adequate assurance that payment risk is being managed effectively. Feedback could be sought from: key internal stakeholders; the Audit Committee; Australian Government entities on behalf of whom Human Services is making payments; and the Minister for Human Services and Digital Transformation.

2.15 The indicators, which could be for departmental use only, would be best determined by Human Services in consultation with stakeholders.

Was the development of the strategy well-informed?

Human Services’ development of the strategy during 2015–16 to 2017–18 was well-informed. Annual reviews of the strategy were based on identifying risks, assessing the controls in place to mitigate the risks, and determining the necessary volumes of activities. The reviews took into account evidence relevant to each step. Human Services consulted with a wide range of internal and external stakeholders to develop the strategy. The consultations were used to inform the department about current and emerging issues, potential treatments, and strategies for conducting compliance activities.

2.16 During 2015–16 to 2017–18, the strategy employed a development process centred on identifying risks, assessing potential mitigating actions (controls), and determining activity volumes. Human Services reviewed the strategy annually during the development process. New versions of the compliance program element were produced each year. New versions of the fraud control element were produced in 2015–16 and 2016–17, with the latter initially extended to cover part of 2017–18 to allow strategic work to be undertaken to inform future versions, and ultimately operating until 30 June 2018.

2.17 To identify point-in-time and trend risks under each of the six core payment risk categories used across the period, Human Services drew on relevant data and information, particularly:

- the results of annual random sample surveys of payment accuracy12;

- risk analysis in payment accuracy risk management plans relating to individual payments13; and

- trends in compliance debt.

2.18 To assess the effectiveness of the controls, Human Services qualitatively analysed the impact of its previous activities, and considered the availability of key information sources to feed into or trigger compliance activities:

- internal and external data matches;

- risk profiles, drawing on risk indicators populated by underlying customer data; and

- tip-offs provided by the public or by staff.

2.19 For the compliance program element of the strategy, the risk identification and controls assessment steps could additionally draw on analysis from end of financial year reports produced for governance purposes. The reports made recommendations for the following year about the types or balance of activities under each risk category.

2.20 To determine the activity volumes, Human Services considered the available resources. Human Services determined the activity types and levels by considering factors such as:

- internal capability (for example, staff numbers and skill profiles);

- the seriousness of the identified risks;

- assessments of the effectiveness of the available controls; and

- Government or department priorities.

2.21 From 2015–16 to 2017–18, Human Services consulted with a wide range of Australian Government stakeholders and regularly participated in compliance and fraud control forums.14 The organisations in Table 2.1 contributed to Human Services’ annual review of the strategy. The consultations also supported the ongoing identification of current and emerging issues, better practice treatments and strategic approaches.

Table 2.1: Human Services’ strategy related consultation and participation in forums, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

Australian Government stakeholders |

Compliance and fraud control forums |

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of advice and documents provided by Human Services.

2.22 Internationally, Human Services also monitored and periodically discussed compliance and fraud control strategies with peer agencies in five nations. The department confirmed that those agencies had identified and targeted benefit payment risk categories very similar to those used in the strategy.

2.23 Human Services advised that it also regularly discussed or corresponded about Centrelink compliance policy and implementation — particularly income data matching activity — with key customer representative bodies including the Australian Council of Social Service, the National Social Security Rights Network and the Welfare Rights Centre.

Does the strategy contain adequate risk management and fraud control frameworks?

The strategy, combined with its supporting documents, contained adequate but high-level references to the department’s risk management and fraud control frameworks. Future strategies could be improved by:

- explicitly stating the connection between the strategy and the department’s risk management and fraud control frameworks; and

- explaining how the planned work, for both compliance and fraud control activities, would contribute to mitigating the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity.

2.24 Human Services’ governance arrangements support the department to deliver its outcomes. Those arrangements include a departmental risk management framework, as a major element, and a related framework for fraud risk management. The department is required to establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight and management so that it can comply with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.15 The department is also required under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014, section 10, to manage fraud risks.

2.25 The following sections discuss the extent to which the strategy (for compliance activities for Centrelink payments) contains adequate risk management and fraud control frameworks. The scope of this audit does not include an assessment of Human Services’ compliance with the legislative and Australian Government guidance requirements for risk management and fraud control.16

Risk management framework in the strategy

2.26 Over the past three years, Human Services has identified up to 10 strategic risks that affected the department at an enterprise level, which were reduced to six in 2017–18. The ongoing risk that was most relevant to the strategy related to payment integrity and was expressed in 2017–18 as: ‘there is a risk the department does not maintain the integrity of payments, including paying the right amount to the right person’.17

2.27 The strategic risks were owned by the Secretary of the department. The Secretary delegated the management of the payment integrity risk to a Senior Responsible Official. The official’s role was to ensure that the risk was effectively managed.

2.28 From 2015–16 to 2017–18, with one exception, high-level references to key elements of the department’s risk management framework were contained in separate risk management plans that were associated with the strategy. The strategy did not make any direct reference to addressing the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity.

Fraud control framework in the strategy

2.29 The department’s Fraud Risk Management Strategy is designed to be consistent with the department’s risk management framework. The department takes an entity-wide rather than program specific approach to managing fraud risk, with details set out annually in a Fraud Control Plan.

2.30 In 2017–18, Human Services’ Fraud Control Plan identified 16 enterprise fraud risks (previously 14 enterprise fraud risks in 2015–16). Part of the plan’s purpose was to explain how the department proposed to mitigate two of the department’s strategic risks:

- failure to manage the integrity of government outlays; and

- failure to protect customer privacy and personal information.

2.31 From 2015 to 2018, the strategy acknowledges the requirement to meet departmental and Australian Government legislation and policies for managing fraud.

2.32 Overall, the strategy could have more clearly stated the relationship between the compliance and fraud control activities that were undertaken and the departments’ fraud control and risk management frameworks. A clear explanation would have included recognising the strategy’s role in mitigating the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity.

Does the strategy support the conduct of and guide the allocation of resources for compliance activities, including fraud control?

Human Services’ strategy for the Centrelink program supports the conduct of and identified the resources required to conduct compliance interventions and fraud control activities from 2015–16 to 2017–18. The delivery of the strategy was supported by other key documents, such as more detailed risk management plans, governance and monitoring frameworks, guidelines and policies.

2.33 Over the three years, from 2015–16 to 2017–18, the operational aims of the strategy have included:

- identifying the priority areas of activity;

- identifying the type of compliance activity and effort required to effectively manage the risks to making accurate payments; and

- effectively managing the available resources to deliver compliance activities.

2.34 In short, the strategy broadly defined the scope of activities that were to be conducted each financial year to address the risk of customer non-compliance for the Centrelink program.

2.35 Table 2.2 sets out the level of direct staffing and number of compliance activities completed annually for the Centrelink program from 2015 to 2018. Human Services calculated that the average return on investment for all Centrelink compliance and fraud activity was: $4.76 (2015–16); $4.80 (2016–17); and $2.54 (as at 31 May 2018).18 The average return on investment was expressed as a dollar figure that indicated the amount of money returned to the Government for every dollar spent on compliance and fraud activities. The return on investment did not take into account any deterrent or educative effect of the activities.

Table 2.2: Centrelink program: direct staffing and compliance activities completed, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

|

Business as usual compliance activities |

|||

|

Direct staffing levelsa |

1,146 |

1,103 |

688 |

|

Number of compliance activities completedb |

888,323 |

864,689 |

825,867 |

|

Budget measure compliance activities |

|||

|

Direct staffing levelsa |

536 |

977 |

1,852 |

|

Number of compliance activities completedb |

102,349 |

216,515 |

262,707 |

Note a: For 2015–16 and 2016–17, the department provided the average staffing levels. In 2017–18, the department provided the average workforce levels, including labour hire, and estimated to 30 June 2018.

Note b: The types of activities included compliance review interventions and preventions.

Source: Data provided by Human Services.

2.36 The ANAO examined the details of the compliance strategy for Centrelink payments from 2015 to 2018 to assess the extent that the following matters were addressed:

- conduct (of the year’s planned activities);

- resourcing (in general terms);

- staffing (numbers);

- number of compliance activities (specified); and

- planned reviews (of resourcing requirements).

2.37 In all three years, the strategy made references to the number of compliance activities to be undertaken annually (see Table 2.3 for details).

2.38 With the exception of 2015–16, the strategy addressed the conduct and general resourcing required each year. With the exception of 2015–16, the strategy recognised the potential that reviews of planned activities and resourcing could be required and any changes would need to be reflected in the strategy. These reviews were in addition to the annual development of the strategy.

2.39 Only the 2017–18 strategy contained details of the planned volume of business as usual activities and the associated staffing numbers. The details for the Budget measures were not included. Otherwise, the detailed allocation and movement of staff between activities within the compliance program was managed at an operational level. The operational level details include moving staff to accommodate changes in priorities (see paragraph 2.48).

2.40 In all three years, the strategy was supported by a number of key documents, such as risk management plans, governance and monitoring frameworks, guidelines and policies. The supporting documents contain additional details to the strategy.

2.41 In 2018–19, Human Services started implementing a Programme Prioritisation Framework for Fraud Intelligence and Investigations for the Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support programs. The Framework, which has both strategic and operational aims, is to be used as an objective methodology to determine the focus of the department’s fraud intelligence and investigation activity. Human Services expects that the Framework will change the planning for, and delivery of, the strategy in the future.

Are outcomes from the strategy adequately monitored and reported?

The department’s monitoring and reporting on the strategy’s progress from 2015–16 to 2017–18 was adequate at an operational level. The original and revised compliance activity targets were not achieved in any year indicating that the department would benefit from reviewing its performance targets annually. Aside from fraud control activities, departmental governance committees at the entity level were not provided with dedicated compliance performance reports from 2015–16 to 2017–18. Future public reporting should be expanded for Centrelink compliance activities, which would increase the transparency and accountability of compliance activities and outcomes.

2.42 Senior managers were provided with adequate oversight of delivery of the strategy using management and operational level committees that were scheduled to meet fortnightly and monthly. The ANAO reviewed examples of the meeting minutes that were produced after meetings were held.

2.43 The governance committees monitored the delivery of the strategy including changes to the planned number of activities and resourcing requirements. The fortnightly, monthly and annual monitoring reports for the strategy included details of the following key indicators of compliance activity:

- performance by the type of intervention (online; indirect; early; direct)19;

- planned and revised compliance activity numbers;

- completions against forecast by the type of risk being treated;

- debts raised and savings realised;

- cases completed;

- cases of alleged fraud referred to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions; and

- totals (progressive and end of year).

2.44 The monitoring reports used a consistent format and had similar content from year to year.20 A monthly report on compliance and debt was circulated within the business group and sent to the Minister’s office. Human Services advised that, in 2018, the Senior Responsible Official for the departmental risk of payment integrity also received a copy of the monthly report as the role is located within the business group.

2.45 In addition, the end of year review reports contained recommendations to improve the strategy’s effectiveness for the following year. The recommendations included suggesting improvements to the governance framework and reporting arrangements. For example, a recommendation to develop a fully automated reporting function to reduce the effort spent on reporting (for non-fraud control activities) was made in 2015–16 and 2016–17. The implementation or other action taken to address the recommendations was not reported against in any of the end of year review reports.

2.46 The end of year report for 2017–18 recommended that future reports should include the following information:

- some historical analysis, to enable an assessment of the compliance strategies that had been applied;

- outcomes from the strategies; and

- an assessment of the cost benefit of the activity overall.

Compliance activity targets and outcomes

2.47 Table 2.3 contains the end of year outcomes reported for the planned compliance activities, not including fraud control as there were no comparable targets in that element of the strategy. The original and revised targets were not achieved in any of the three years.

Table 2.3: Compliance activity targets (not including fraud control) and outcomes, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

Year |

Original target of activity volumesa |

Revised target |

Outcome |

Percentage of original target achieved |

Percentage of revised target achieved |

|

2015–16 |

1,104,132 |

– |

987,895 |

89.5% |

– |

|

2016–17 |

1,803,074 |

1,711,840 |

1,064,651 |

59% |

62.2% |

|

2017–18 |

2,489,146 |

1,145,406b |

1,014,754 |

40.8% |

88.6% |

Note a: The activity numbers in the end of year reports do not include Business Integrity and Taskforce Integrity compliance activities.

Note b: Human Services advised that the activity volumes were revised as a result of the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2017–18 and changes made during the preparation of the Budget for 2018–19.

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ end of year reports and advice from Human Services.

2.48 The strategy is based on planned volumes of activity and is designed to be flexible and to accommodate changes in priorities. Explanations are provided for variations in review reports produced at the end of each year. For example, in 2016–17, changes were made to the program for multiple reasons including: limitations with data matching; limitations with system or ICT updates; and staff being reallocated to priority activities. In April 2017, Human Services made significant changes to the strategy to focus on improving self-service (online) compliance interventions. Human Services advised that, at the same time, many customers had a preference for staff assistance during a compliance check associated with Budget savings measures. The changes resulted in additional staff being allocated to Budget measure activities to deliver the planned number of interventions.

2.49 The outcomes reported in Table 2.3 are against a combination of targets set by the department and the Government, neither of which are reported against externally. Decisions about tolerance levels for not achieving those targets are determined by the entity’s managers. The average percentage of the target achieved in Table 2.3 was 63.1 per cent of the original target (over three years). An annual target may not be achieved in one year, but not achieving the target in any of the three years suggests that the performance targets may warrant review. The ANAO suggests that Human Services could better demonstrate the effective performance of its compliance activities by setting realistic annual targets that are:

- informed by an assessment of the achievement of its compliance activity targets over a multi-year period and in line with the risk tolerance for those activities; and

- combined with the known Budget measure and estimated business as usual future levels of compliance activity.

2.50 In addition, the performance assessment of Centrelink compliance activities would be improved if the end of year activity results were reported against the original unadjusted annual targets.

Reporting to departmental governance committees

2.51 At the entity level, the department has a governance committee structure to support its operation and service delivery functions.

2.52 From 2015–16 to 2017–18, regular reporting on fraud control activities undertaken for the strategy was considered by a number of the governance committees, including the Executive Committee. Chaired by the Secretary, the Executive Committee was responsible for monitoring risk and compliance standards. The reporting included an annual Fraud Control Certification that reported broadly on non-compliance and fraud outcomes from the strategy.21 The same reports were sent to the department’s Audit Committee, as an advisory committee.

2.53 The committees largely ‘noted’ the contents of the reports. Committee action items that requested changes to the format or content of the reports did not require changes to the design or operation of the strategy.

2.54 Reports to the committees focused on the fraud control activities of the strategy, which were underpinned by the mandatory reporting requirements for fraud control activities.22

2.55 Human Services advised that, starting in 2018–19, a ‘comprehensive snapshot’ of the compliance program for Centrelink payments is being provided to the Service Delivery Committee. The committee is a strategic governance committee and a sub-committee of the Executive Committee. The ANAO considers that this new initiative could improve the transparency of reporting within the department about the compliance activities for the Centrelink program. The report could also facilitate a greater level of senior management engagement and scrutiny, including over activity target revisions and resource reallocation decisions.

2.56 The department’s current Audit Committee Charter (November 2017), as determined by the Secretary, states that the functions of the Audit Committee are to review and give independent advice and assurance about specified matters including the appropriateness of the department’s system of risk oversight and management. As described in paragraph 2.26, the department has identified payment integrity as a strategic risk that affects the department at an enterprise level. The Audit Committee’s Charter also sets out a function for performance reporting that includes reviewing, advising and assuring the appropriateness of Human Services’ framework for developing and reporting key performance indicators and the department’s annual performance statement. An annual performance statement is published in the department’s annual report.

2.57 The ANAO suggests that Human Services assist its Audit Committee to fulfil its Charter functions in relation to the department’s system of risk oversight and management, and performance reporting, by providing dedicated reports to the Committee about compliance activities undertaken for the Centrelink program.

Public reporting

2.58 The current performance measurement and reporting requirements for Commonwealth entities (corporate and non-corporate) are established under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the accompanying Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014. Human Services is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity and publishes an annual report that describes the department’s activities during the financial year, reports on its performance, and presents financial information.

2.59 The department reported on its compliance and business integrity (fraud control) activities in its annual reports from 2015–16 to 2017–18.23 The department provided qualitative descriptions of the compliance work undertaken for the Centrelink program, including serious non-compliance (fraud). In 2015–16, a table of compliance activity for social welfare payments was included that reported the number of compliance activities (interventions) completed in a time series from 2013–14 to 2015–16. A similar table was not included in the department’s annual reports for 2016–17 and 2017–18 and the number of compliance activities completed in each of those two years was not published.

2.60 The loss of year-on-year data about Centrelink compliance activities, in annual reports after 2015–16, has reduced the transparency and accountability for the department’s compliance activities. Human Services should review how it can increase the availability and transparency of its public reporting on compliance activities for the Centrelink program.

Recommendation no.1

2.61 That Human Services increase its public reporting, starting from 2018–19, of the compliance activities completed each year for the Centrelink program of administered payments.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

2.62 The department agrees with the ANAO’s recommendations, and is committed to providing its partner agencies, the Australian Parliament and the community with transparent information about the department’s performance in delivering its compliance outcomes. The department will review its public reporting on compliance outcomes in order to determine appropriate changes to its external reporting on compliance.

2.63 Successful prosecution outcomes are a major component of the department’s fraud control activities and are reported in its annual report. Human Services reported that 1,354 fraud investigations were completed for the Centrelink program (social security and welfare program) in 2015–16 and 1,104 fraud investigations were completed in 2016–17. In 2017–18, the number of investigations completed for the program was 686. In 2015–16, a total of 980 alleged cases of fraud (for Centrelink payments) were reported as having been referred to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions to decide whether to prosecute matters. The following year, in 2016–17, 703 alleged cases were referred for a decision. In 2017–18, 560 cases were referred for a decision.

3. Compliance strategy for Medicare payments

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the design and operation of Human Services’ high-level strategy for conducting compliance activities for the Medicare program from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Conclusion

The design and refinement of a high-level strategy for the Medicare program provided clear guidance for Human Services to undertake a coordinated program of fraud control activities in 2016–17 and 2017–18. Medicare customer compliance activities undertaken by Human Services in 2015–16 were not included in the strategy. After 2015–16, the conduct of the strategy was supported in the next two years by adequate risk management and fraud control frameworks. The strategy in those two years also adequately identified the resourcing required to undertake fraud control activities and regularly monitored and reported on the outcomes from those activities.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at Human Services completing, in 2018–19, a negotiation process with the Department of Health, and any resulting compliance activities, for payments being made to third party providers under Medicare health and aged care programs.

The ANAO also suggested that the Programme Prioritisation Framework for Fraud Intelligence and Investigations be updated to include those health and aged care programs once a decision has been made by Human Services and the Department of Health regarding departmental responsibility.

Does the design of the strategy provide clear guidance for the Medicare program?

The 2015–16 strategy was not updated to include activities for Medicare customer compliance after machinery of government changes were made in 2015.24 In 2016–17 and 2017–18, the strategy was updated and provided clear guidance for the conduct of fraud control activities for Medicare customer compliance. From 2015–16 to 2017–18, no activities were undertaken by Human Services for any of the 17 health and aged care programs that interacted with third party providers, as departmental responsibility was not resolved between Human Services and the Department of Health.

3.1 In 2015–16, machinery of government changes transferred Medicare provider compliance to the Department of Health (see paragraph 3.5 for details). Some targeted fraud activities for health payments made under the Medicare program to customers (patients) were continued by Human Services.25 An existing Intelligence Plan (2015–16) for external fraud was not updated to include all of the activities undertaken by Human Services for Medicare customer compliance.

The strategy in 2016–17 and 2017–18

3.2 From 2016–17 to 2017–18, Human Services more completely documented its approach to managing non-compliance for payments made under the Medicare program in an Intelligence Plan for external fraud (‘the strategy’). The strategy was applied to 54 health programs or payments and six aged care programs.26 The exception was that the strategy did not include 17 health and aged care programs that interacted with third party providers (see Table 3.1).

3.3 The strategy’s aim was operational, to set out the priority areas for Human Services’ intelligence focus and related activities for external fraud control. The four key objectives of the strategy were to:

- detect — new, emerging and ongoing risks;

- prevent — implement intelligence led projects and target responses;

- engage — with internal and external stakeholders to promote a whole of government response to fraud; and

- respond — to fraud issues.

3.4 The strategy clearly documented the key features of Human Services’ approach to Medicare compliance including: the scope of activity; the approach to fraud control activity; groups of risks to be addressed; and planned types of activity to address the risk groups. The strategy set out its governance arrangements, which are discussed in more detail later in the chapter. Among the planned intelligence activities in the strategy, the department aimed to address potential non-compliance with Claiming Medicare Benefits Online and other Medicare Benefits Schedule claims. The strategy also identified potential activities for other Medicare customer compliance occurring within the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme that, subject to further analysis, could be undertaken.

Machinery of government changes in 2015

3.5 Machinery of government changes are a major driver of organisational change within the Australian Public Service. The changes occur relatively frequently and are used by the Australian Government to express policy priorities and meet policy challenges.27 An Administrative Arrangements Order, made on 30 September 2015, transferred responsibility for Medicare provider compliance28 from Human Services to the Department of Health. The responsibility for Medicare customer compliance remained with Human Services.

3.6 The responsibilities for compliance activities for 17 health and aged care programs that interacted with third parties29 remained unresolved between the two departments after the implementation of the machinery of government changes in 2015. This audit focused on Human Services’ compliance strategy for the Medicare program from 2015–16 to 2017–18, which potentially could have included activities for some or all of the 17 health and aged care programs if there had been a decision on Human Services’ responsibility for these programs.

3.7 Table 3.1 shows the Medicare customer compliance activities included in Human Services’ strategy from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Table 3.1: Medicare customer compliance activities in the strategy, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

Medicare customer compliance in the strategy |

Health and aged care programs with third party interactions |

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services’ documents.

3.8 In Table 3.1, the largest number of third party providers are associated with the Continence Aids Payment Scheme (1894) and the largest total amount paid to third parties, for a single program, was $17.7 billion for the Private Health Insurance Rebate program over three years. The total amount of administered payments made by Human Services for the Medicare program from 2015–16 to 2017–18 was $170.22 billion.

3.9 Historically, there had been limited compliance activity by the department for Medicare customer compliance, including for third party providers. Compliance activity was not a priority and some third party programs were considered a low risk. After the machinery of government changes, Human Services’ risk management activities for fraud control were focused at the program level, for example, the broader Medicare Benefits Schedule, and not at individual third party providers.

3.10 In 2016, Human Services reviewed its existing customer compliance activities and risks relating to health and aged care programs. The review identified a number of low and medium risks for nine programs, of which six programs had interactions with third party providers. The review highlighted a need for the department to clarify the extent of its compliance responsibilities, with the Department of Health, for third party providers that were receiving payments under the Medicare program.

3.11 The department’s Enterprise Fraud Risk Register that collates all division level fraud risks contains an entry from February 2017 for a treatment to address the risk of fraudulent claims against health and aged care programs. As at July 2018, the entry described ongoing discussions between Human Services and the Department of Health about the future responsibility for compliance activities for health programs with third party providers. Human Services expected, at that time, that the risk treatment would be implemented by the end of 2018, which would complete the 2015 machinery of government changes.

Arrangements for third party compliance, August 2018 onwards

3.12 In August 2018, Human Services and the Department of Health agreed to review the scope of, and arrangements for, third party compliance to determine the ongoing responsibility for those functions by each department. Until the review is finalised, the two departments also agreed to be jointly accountable and responsible for third party compliance for all of the health and aged care programs.

3.13 The review was to include a risk assessment for each health and aged care program that interacts with third party providers. The risk of non-compliance, for the 17 programs previously identified, was stated by the departments as: a medium risk for three of the programs; and low risk for the other 14 programs. The departments considered that effective controls and compliance activities were in place for the broader health and aged care programs, which includes the 17 programs.

3.14 A working group for the review was scheduled to report to the Health and Human Services Deputy Secretaries Committee before the end of November 2018. One outcome from the review is to determine if additional compliance controls or activities are required and, if so, when they should be conducted.

3.15 Human Services advised the ANAO that, as at 29 October 2018, each department had separately completed a review of the risk profile of the programs and identified additional compliance controls. A consolidated report was being prepared and it was expected that the recommendations contained in the report would be considered and finalised by Deputy Secretaries from Human Services and the Department of Health in 2018–19.

Recommendation no.2

3.16 That, in 2018–19, Human Services:

- finalise its negotiations with the Department of Health about the responsibility for third party provider compliance under the Medicare program;

- confirm the risk profile and adequacy of existing controls for each health and aged care program for which it has responsibility, as part of the planned joint review with the Department of Health; and

- complete sufficient compliance activities to support Human Services’ compliance strategy for Medicare payments for which it has responsibility.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

3.17 The department agrees with the recommendation noting that the issue of third party compliance activities for Medicare programmes remained unresolved with the Department of Health following the 2015 machinery of government changes, which saw responsibility for Medicare provider compliance transferred from Human Services to the Department of Health.

3.18 The department is committed to resolving these responsibilities, and has convened a working group with the Department of Health to jointly review the scope of, and the arrangements for, third party compliance, with a priority of resolving the ongoing responsibility for these functions by department.

3.19 Pending agreement with the Department of Health over the division of responsibilities, and on the basis of overall compliance risk, the department will review its Medicare compliance activities to include third party payments and services where appropriate.

3.20 After the compliance responsibilities are jointly agreed for each department, Human Services should seek to implement the recommendation in a timely way including addressing any legislative and resourcing requirements. This will finalise an unresolved responsibility from the machinery of government changes made in 2015.

Was the development of the strategy well-informed?

Human Services’ development of a strategy for the Medicare program for 2016–17 was well-informed by reviews of past compliance activity, risk assessments and consulting with key stakeholders about fraud control. The strategy included activities for Medicare customer compliance that were developed in 2015–16. The 2016–17 strategy was then continued for 2017–18.

3.21 Human Services drafted the strategy in September 2016 following an annual development process. To develop the strategy, Human Services analysed key fraud control risks and identified planned and potential activities to mitigate those risks.

3.22 General fraud control risks were identified by analysing information sources including:

- environmental scans of developments in technology, public interest and political focus;

- point-in-time and trend data on payment inaccuracy, debts raised and tip-offs received, by risk and payment type; and

- reviews of past compliance activity targeted at specific risks.

3.23 In analysing risks and identifying mitigating activities specific to the Medicare program when developing the strategy for 2016–17, Human Services also drew on activities performed from late 2015 to late 2016 to transition the remaining Medicare compliance functions into the fraud control program. The department’s activities included:

- undertaking payment integrity and fraud risk assessments and developing payment integrity risk management plans30;

- analysing the legislative authority and limitations on possible compliance activities; and

- planning new fraud control actions to address the payment integrity risks for the Medicare Benefits Schedule, which were incorporated in the strategy.

3.24 Planned and actual activity volumes were determined on an ongoing basis through processes documented separately, such as the associated case selection and prioritisation guidelines, intelligence distribution plans and investigation work plans.

3.25 As discussed in Chapter 2, when developing and implementing the strategy, Human Services consulted with a wide range of external stakeholders. The department participated in compliance and fraud control forums with Australian Government law enforcement agencies and overseas government agencies with fraud control functions for benefit payments.

3.26 The strategy was endorsed by Human Services’ senior management in November 2016, and any changes were to be authorised by the National Manager. The 2016–17 strategy was extended, with the agreement of senior management, to 30 June 2018.

Does the strategy contain adequate risk management and fraud control frameworks?

The strategy, in 2016–17 and 2017–18, adequately identified Human Services’ enterprise risk management and fraud control frameworks as being relevant to the strategy. Similar to the compliance strategy for the Centrelink program, the strategy for the Medicare program could also have included a more explicit statement connecting the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity and the fraud control activities that were completed in the two-year period.

3.27 In Chapter 2, Human Services’ departmental risk management framework, as a major element of its governance framework, and a related framework for fraud risk management, were described. The chapter also identified the legislative and policy requirements for the department’s risk oversight and management, and the management of fraud risks including the requirements for mandatory reporting about fraud.

3.28 The scope of this audit does not include an assessment of Human Services’ compliance with the legislative and Australian Government guidance requirements for risk management and fraud control.31 The following section discusses the extent to which the strategy (fraud control for payments made under the Medicare program) contains adequate risk management and fraud control frameworks.

Risk management and fraud control frameworks in the strategy

3.29 Human Services’ Fraud Control Plan, 2017–18, described how the department proposed to mitigate two of its strategic risks: failure to manage the integrity of government outlays; and failure to protect customer privacy and personal information. This is important because the Medicare program’s strategy focused on fraud control to manage non-compliance for the recipients of health payments. A potential example of non-compliance would be a patient making a claim for a payment (under the Medicare Benefits Schedule) for a major surgical procedure where there are no complementary items such as a specialist consultation before the procedure.

3.30 The department’s Fraud Risk Management Strategy is designed to be consistent with the department’s risk management framework. The strategy for the Medicare program, from 2016–17 to 2017–18, included the following links to the department’s risk management framework:

- identifying Human Services’ Enterprise Risk Management Policy as a related document;

- a reference to applying the departmental risk management process to identify and analyse issues and risks; and

- acknowledging a requirement to meet departmental and Australian Government legislation and policies for managing fraud.

3.31 The strategy did not make any direct mention of addressing the department’s strategic risk for payment integrity. In future, the strategy could also more clearly document the relationship between conducting fraud control activities and mitigating specific strategic risks for the department.

Does the strategy support the conduct of and guide the allocation of resources for fraud control activities?

Human Services’ strategy for the Medicare program adequately identified the resources required to conduct fraud control activities for the program in 2016–17 and 2017–18 for customer compliance cases. In 2015–16, activities were not included for customer compliance cases and third party providers were not included in any of the three years.

3.32 Following the machinery of government changes in late 2015, a Medicare customer component was not immediately included in the annual strategy for external fraud. In the next two years, 2016–17 and 2017–18, Human Services’ strategy included specific fraud control activities for Medicare customers.

3.33 In 2016–17, the strategy specifically focused on external fraud carried out by the department’s customers or members of the general public. The strategy included awareness raising programs, prevention strategies, investigations, and debt raising in the context of fraud control. The 2016–17 strategy was initially extended to cover part of 2017–18 and remained in operation until 30 June 2018.

3.34 The operational aim of the strategy was to:

- set out the priority areas and activities for the Medicare program; and

- focus resources and capability on addressing the priority risks.

3.35 The strategy also aimed to support Human Services’ broader obligations under legislation, policy and guidance for fraud control.

3.36 Table 3.2 sets out the average direct staffing level and number of compliance activities completed annually for the Medicare program from 2015 to 2018.

Table 3.2: Medicare program: average direct staffing and compliance activities completed, 2015–16 to 2017–18

|

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18a |

|

Business as usual compliance activities |

|||

|

Direct staffing levelsb |

227.02 |

86.29 |

70.31 |

|

Number of compliance activities completedc |

1,693 |

499 |

317 |

|

Budget measure compliance activities |

|||

|

Direct staffing levelsb |

0 |

0 |

13d |

|

Number of compliance activities completedc |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Note a: Estimated to 30 June 2018.

Note b: Average staffing levels.

Note c: The types of activities included compliance review interventions and preventions.

Note d: Staff funded under a Budget measure in 2017–18, ‘Guaranteeing Medicare — Medicare Benefits Schedule — improved compliance’, did not undertake any compliance activities.

Source: Data and descriptions provided by Human Services.

3.37 The department evaluates and investigates potential instances of Medicare fraud involving claiming for services that were not received. Specialist staff assess fraud claims. As shown in Table 3.2, focusing on the most serious cases that may involve more than one person is more resource and time intensive than other compliance activities such as sending reminder letters or emails to Centrelink customers and the number of activities that can be completed each year is lower. The ANAO examined the compliance strategy for Medicare payments from 2016 to 2018 to assess the extent that the following matters were addressed:

- conduct (of the year’s planned activities);

- resourcing (in general terms);

- staffing (numbers);

- number of compliance activities (specified); and

- planned reviews (of resourcing requirements).

3.38 The two-year strategy, for 2016–17 to 2017–18, made reference to all of the matters in paragraph 3.37 except for staffing. Similar to the strategy for the Centrelink program (in Chapter 2), the strategy for the Medicare program was supported by a range of policies, guidance and more detailed operational level plans. Provision was made in the strategy for making changes to the priorities and resourcing.

3.39 As discussed in Chapter 2, Human Services started implementing a Programme Prioritisation Framework for Fraud Intelligence and Investigations for the Centrelink, Medicare and Child Support programs in 2018–19. Human Services expects that the Framework will change the planning for and delivery of the Medicare compliance strategy in future years. The ANAO suggests that the framework be updated to include all of the health and aged care programs that interact with third party providers and that Human Services is responsible for providing compliance activities.

Are outcomes from the strategy adequately monitored and reported?