Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Government Advertising: March 2013 to June 2015

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objectives of the audit were to:

- assess the effectiveness of the ongoing administration of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework; and

- assess the effectiveness of the selected entities’ administration in developing advertising campaigns and implementing key processes against the requirements of the campaign advertising framework applying at the time, and relevant legal and government policy requirements.

Summary and recommendations

Background

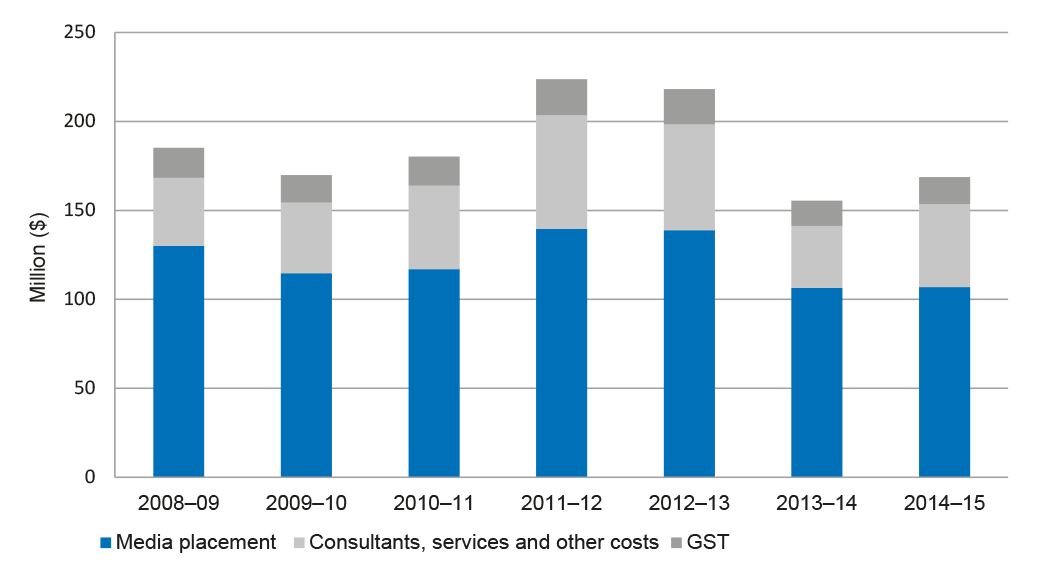

1. Governments conduct advertising campaigns to: inform the community about government policies, programs and services; inform individuals of their obligations, rights and entitlements; or to encourage informed consideration of issues or to change behaviour. Between 2008–09 and 2014–15, average Australian Government expenditure each financial year on advertising campaigns was $186 million. This expenditure included media placement, communications suppliers and GST, but did not include administrative costs.

2. Successive governments have maintained a framework to regulate the use of campaign advertising. The overarching aim of the framework is to provide the Parliament and the community with confidence that public funds are used to meet the genuine information needs of the community. Since 2008, key features of the framework have included principles-based guidelines, and a process for entity chief executives to certify the compliance of campaigns against the guidelines. In certifying campaigns, chief executives have also been supported by third-party advice for most of the period since 2008. The Special Minister of State is responsible for the administration of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework, and is supported by the Department of Finance. Finance publishes the guidelines and provides further guidance and advice to entities through its website and Communications Advice Branch.

3. The key principles contained in the guidelines have remained broadly consistent since 2008. The five information and advertising principles included in the most recent iteration of the guidelines are:

Principle 1: Campaigns should be relevant to government responsibilities.

Principle 2: Campaign materials should be presented in an objective, fair and accessible manner and be designed to meet the objectives of the campaign.

Principle 3: Campaign materials should be objective and not directed at promoting party political interests.

Principle 4: Campaigns should be justified and undertaken in an efficient, effective and relevant manner.

Principle 5: Campaigns must comply with legal requirements and procurement policies and procedures.

Audit approach

4. The objectives of the audit were to:

- assess the effectiveness of the ongoing administration of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework; and

- assess the effectiveness of the selected entities’ administration in developing advertising campaigns and implementing key processes against the requirements of the campaign advertising framework applying at the time, and relevant legal and government policy requirements.

5. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the effectiveness of Finance’s overall administration of the campaign advertising framework, including its advice to entities on framework developments;

- progress made towards addressing any outstanding recommendations from previous ANAO audit reports on government advertising;

- compliance of the specified campaigns with the campaign advertising framework and applicable guidelines, and compliance with relevant procurement and legal requirements; and

- where the campaign advertising guidelines did not apply, entity processes applying to specified campaigns promoted the achievement of value for money.

6. The audit reviewed the evolution and administration of the campaign advertising framework from the end of the period examined by the ANAO’s previous performance audit (March 2013). In addition, three campaigns were selected for review, specifically the:

- Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign conducted in 2015, and administered by the Department of the Treasury;

- Higher Education Reforms Communication campaign conducted in late 2014 and early 2015, and administered by the Department of Education and Training; and

- anti-people smuggling advertising campaigns conducted both within Australia and overseas since 2013, and administered by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

7. The selection of campaigns for inclusion in the audit took account of a number of requests from members of Parliament that the Auditor-General examine specific campaigns.

Conclusion

8. Between November 2013 and February 2015, the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework was weaker than it could be, due to the suspension of the third-party advisory process. The process was re-established in early 2015 with the appointment of a reconstituted Independent Communications Committee, but the early timing of the committee’s review of campaigns means that it is not in a position to provide a high level of confidence to entity chief executives—and by extension the Parliament and community—regarding a campaign’s compliance with the guidelines. At present, the committee reports on whether a campaign is ‘capable’ of complying with the guidelines, as it does not review final campaign materials and other relevant information. The committee’s terms of reference should be amended to enable its review at any stage of a campaign’s development.

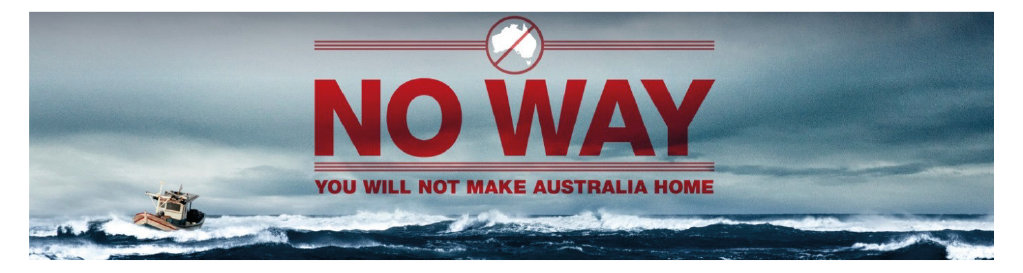

9. All of the campaigns selected for review in this audit were certified at key stages by the responsible chief executives as complying with the applicable guidelines. One element of one of the campaigns was exempted from the guidelines on the basis of extreme urgency relating to a change in government policy, as provided for in the guidelines. The chief executive certifications were supported by detailed advice from their respective departments. The ANAO’s review of the information supporting that advice indicated that there were some shortcomings in advice and departmental processes relating to:

- the Department of the Treasury’s Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign—compliance with procurement policies and procedures;

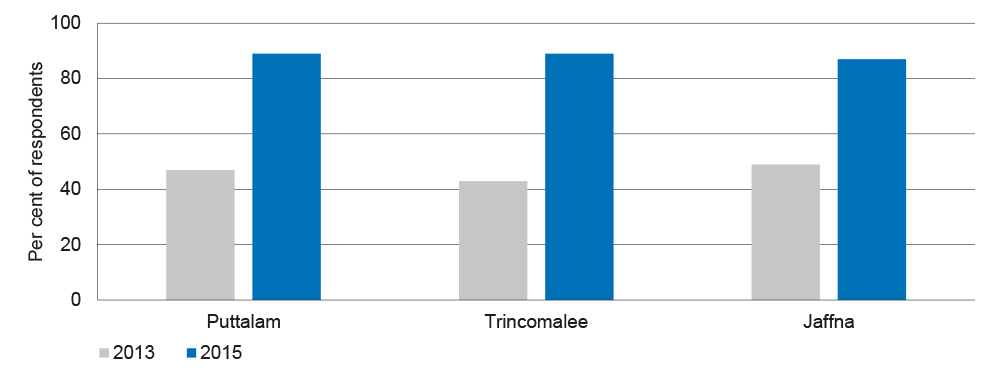

- the Department of Education and Training’s Higher Education Reforms Communication campaign—presenting campaign materials in an objective and fair manner; compliance with procurement policies and procedures; and not advising the Secretary of concerns raised in relation to compliance with relevant legal requirements; and

- the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s anti-people smuggling advertising campaigns—compliance with procurement policies and procedures.

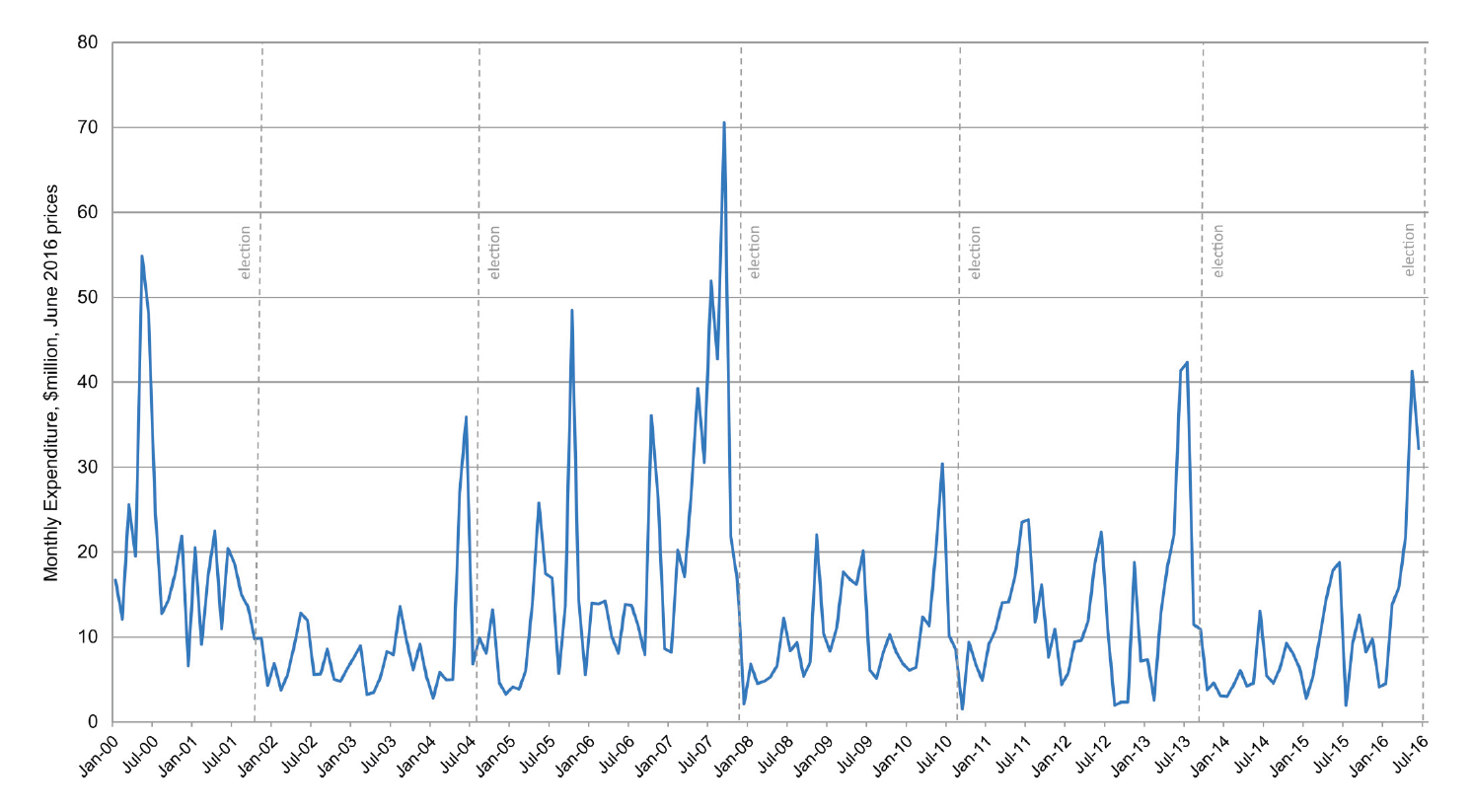

10. Campaign expenditure increased in the periods prior to the 2013 and 2016 federal elections, continuing a long-term trend. Average Australian Government expenditure each financial year since 2008–09 on advertising campaigns has been $186 million.1 In 2013 and 2016 approximately $100 million and $95 million respectively, was spent on media placement alone in the three months leading up to the caretaker period.

Supporting findings

The Australian Government campaign advertising framework (Chapter 2)

11. The ANAO’s review of developments since 2013 indicates that:

- roles and responsibilities under the campaign advertising framework could be made clearer by amending the chief executive certification template to reflect instances where Ministers provide financial approvals; and

- the compliance advice provided by the current Independent Communications Committee is limited compared to what has been provided in the past.

12. In mid-2014, the government established a Service Delivery and Coordination Committee to oversee and review campaigns. The Committee took on a decision-making role in the development and approval of large campaigns, including the selection of communications suppliers and refining and approving final advertisements and media buys. The chief executive certification template should be amended to reflect instances where Ministers provide financial approvals.

13. Short-term interim arrangements for campaign advertising were in place between November 2013 and February 2015, applying to 17 campaigns. The interim arrangements did not include third-party review of campaigns’ compliance against the guidelines. Campaigns were endorsed in writing by the Special Minister of State. In contrast with the Independent Communications Committee process, which involved the public release of its advice to entities, the Special Minister of State’s endorsements were not released publicly.

14. The 2014 Guidelines reintroduced the Independent Communications Committee as a third-party adviser, however it provides more limited compliance advice than its predecessors. Under its terms of reference, the current committee reviews campaigns once and at an early stage of campaign development, and reports on whether campaigns are ‘capable of complying with Principles 1 to 4 of the Guidelines’. The committee does not review final campaign materials. The committee had previously been required to form a view and advise entity chief executives about a campaigns’ compliance. The current committee has raised these limitations with the Department of Finance, and the ANAO has made a recommendation on this matter.

15. A previous (2011–12) ANAO recommendation to clarify which parts of the guidelines are mandatory has not been fully addressed. Finance released explanatory guidance in early 2015 which went some way towards providing clarification, however numerous provisions of the advertising guidelines contain the word ‘should’ despite Finance’s general advice to entities that the word ‘should’ is best avoided in regulatory and guidance documents. By failing to fully address the recommendation, there remains a lack of clarity around which parts of the advertising guidelines are mandatory. Four of the five information and advertising principles contain the word ‘should’, including Principle 3 which provides that ‘campaigns should be objective and not directed at promoting party political interests’.

16. Two further recommendations were directed towards Finance in the ANAO’s 2012–13 audit of government advertising. One recommendation related to the development of guidance for entities in the event that they propose to undertake campaigns relating to the views, policies or actions of other parties. Finance has prepared relevant guidance for provision on an ad hoc basis. It has not been published.2

17. The ANAO’s comparison of the current Australian Government framework with arrangements applying in other jurisdictions indicates that while there is a common approach in some key respects (for example, in seeking to prohibit party political content and ensure factual accuracy), a number of key differences exist. A number of jurisdictions have adopted restrictions on: Ministerial direction of entities; the subject matter of campaigns; and conducting campaigns during caretaker periods. Some frameworks also had requirements intended to avoid ‘excessive’ or ‘extravagant’ advertising.

18. Between 2008–09 and 2014–15, Australian Government expenditure on advertising campaigns averaged $186 million each financial year. This expenditure included media placement, communications suppliers and GST, but not departmental costs incurred in campaign development or the cost of the Independent Communications Committee. ANAO analysis shows a tendency for campaign expenditure to increase significantly in the lead up to a federal election. Increased expenditure has been observed prior to the last five elections. In 2013 and 2016 around $100 million and $95 million respectively, was spent on media placement alone in the three months leading up to the caretaker period.

Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign (Chapter 3)

19. The Treasury Secretary certified that the campaign complied with the 2014 Guidelines. The ANAO’s review of the information supporting the certification indicated that there were some shortcomings in advice and departmental processes relating to compliance with procurement policies and procedures.

20. The Treasury Secretary’s certification that the campaign complied with the 2014 Guidelines was underpinned by detailed advice from the department. It was also supported by a number of other inputs such as research and legal advice. As the Independent Communications Committee had not yet started to operate, the first phase of the campaign was not subject to third party review against the 2014 Guidelines.

21. The initial campaign budget was informed by Master Media Agency3 advice, without campaign objectives having been specified. The campaign was designed in a manner that provided flexibility in the subject matter and timing of different phases of campaign activity. Some campaign materials were developed, at a cost of more than $1.7 million, which were not used. Treasury advised the ANAO that the materials were developed:

- in accordance with decisions of the Service Delivery and Coordination Committee; and

- having regard to the advice of the Independent Communications Committee.

22. Treasury further advised that as soon as relevant decisions of the Service Delivery and Coordination Committee were communicated it stopped work to minimise any additional spending.

23. In relation to Principle 5 (compliance with relevant procurement and legal requirements), Treasury’s procurement documentation did not reflect the Service Delivery and Coordination Committee’s substantive role in making key campaign decisions and providing financial approvals. The ANAO also identified areas in which Treasury did not follow procurement policies. Contracts for research services were not varied in a timely manner, and AusTender reporting was not always accurate.

24. The campaign was monitored and evaluated, but insight into the campaign’s overall effectiveness was hampered by a lack of specific performance targets. Tracking research was conducted during the course of the campaign, and an evaluation was conducted during September 2015. The evaluation concluded that the ‘campaign achieved strong reach among its target audiences, especially during phase 1’. While Phase 1 had achieved good cut through and had raised awareness of the IGR, the advertisements had not raised awareness of key IGR challenges. The evaluation recommended that any future communications activity should focus on explaining specific reforms and should disassociate from the IGR due to: the lack of awareness and understanding of specific IGR content; and the IGR’s perceived focus on difficulties rather than opportunities. While the evaluation compared a number of performance measures against relevant pre-campaign benchmarks or tracked changes in measures throughout the campaign, specific targets had not been set by Treasury. As a result, it was not possible to gain insight into the campaign’s overall effectiveness and relative value for money. Treasury acknowledged that the campaign strategy did not include specific measures against the campaign objectives.

The Higher Education Reforms Communication campaign (Chapter 4)

25. The Education Secretary certified that the campaign complied with the Interim 2013 Guidelines. The ANAO’s review of the information supporting the certification indicated that there were some shortcomings in advice and departmental processes relating to: presenting campaign materials in an objective and fair manner; compliance with procurement policies and procedures; and not advising the Secretary of concerns raised in relation to compliance with relevant legal requirements.

26. In relation to Principle 2 of the guidelines (that campaign materials should be presented in an objective, fair and accessible manner and designed to meet the campaign objectives), the campaign’s objectives were to counter myths and misconceptions about higher education, raise awareness of government support, and to raise awareness of the proposed policy changes. Campaign research highlighted that potential students and their families wanted to learn more about the changes and in particular their impacts on student fees. The campaign materials did not directly address the issue of student fees, and did not provide information on how key policy settings would impact on the cost of undergraduate degrees.

27. A sub-principle of the guidelines provides that facts should be accurate and verifiable. A central campaign statement was that ‘The Australian Government will continue to pay around half of your undergraduate degree’. The department’s data indicated that in 2014 the government was contributing, on average, almost 60 per cent towards the cost of undergraduate degrees. The department’s modelling indicated that the proposed policy changes were expected to result in an average Commonwealth contribution of almost 43 per cent in 2018. In calculating this average Commonwealth contribution level Education included a number of students subject to existing arrangements. Education advised the ANAO that if only those students subject to the reforms were included, the average Australian Government contribution to undergraduate degrees was estimated to be 39.5 per cent by 2018. Education further advised the ANAO that its ‘fee assumptions indicated that the proposed changes were expected to result in roughly equal government and student contributions across all subsidised students in 2016, the year in which the changes would commence and which was of primary interest to students’. The department’s data and modelling supports the campaign statement for the first year (2016), with students subject to the existing arrangements taken into account. However, the statement is not as strongly supported in the subsequent years, and for all new students to whom the reforms were to apply. The statement could also have been misinterpreted by potential students and their families because, at the individual level, the government’s contribution to different courses varies considerably.

28. In relation to Principle 5 (compliance with legal and procurement requirements), Education sought advice on the campaign’s compliance with relevant laws. Two key issues raised in legal advice were the possible outcome of any constitutional challenge to the campaign (if the campaign preceded the passage of the relevant legislation) and the potential for two statements to mislead target audiences (including the central statement discussed above). Education’s statements of compliance, which were prepared to inform the Secretary’s certification of the campaign, advised that legal advice had confirmed the campaign’s compliance, without noting these concerns. Education advised the ANAO that it was satisfied with internal legal advice and made the judgement that, on balance, the two statements were not misleading to the target audience. Education also did not maintain full records of its procurement activities or report all relevant contracts on AusTender in a timely fashion.

29. The campaign was monitored and evaluated, but insight into the campaign’s overall effectiveness was hampered by a lack of specific performance targets. Benchmark, tracking and evaluation research was conducted for Phases 1a and 1b of the campaign. The evaluation concluded that the campaign had ‘efficiently and effectively reached target audiences and achieved measurable changes in awareness, perceptions and behaviours’. The evaluation reported that: around half the research participants had seen or heard something about higher education during the relevant time period; but more participants had heard about higher education in the general media rather than the campaign. The evaluation also reported modest but positive improvements in respondents’ understanding of elements of the Australian higher education system. While the evaluation compared a number of performance measures against relevant pre-campaign benchmarks or tracked changes in measures throughout the campaign, specific targets had not been set by Education. As a result, it was not possible to gain insight into the campaign’s overall effectiveness and relative value for money.

Anti-people smuggling advertising campaigns (Chapter 5)

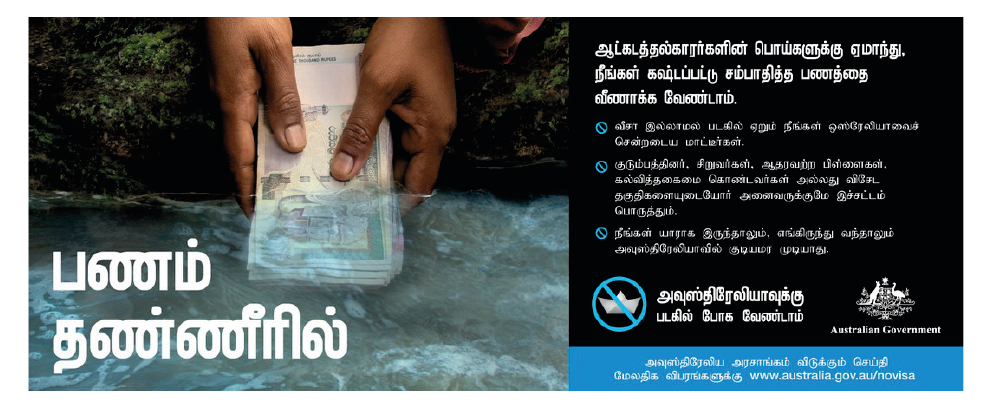

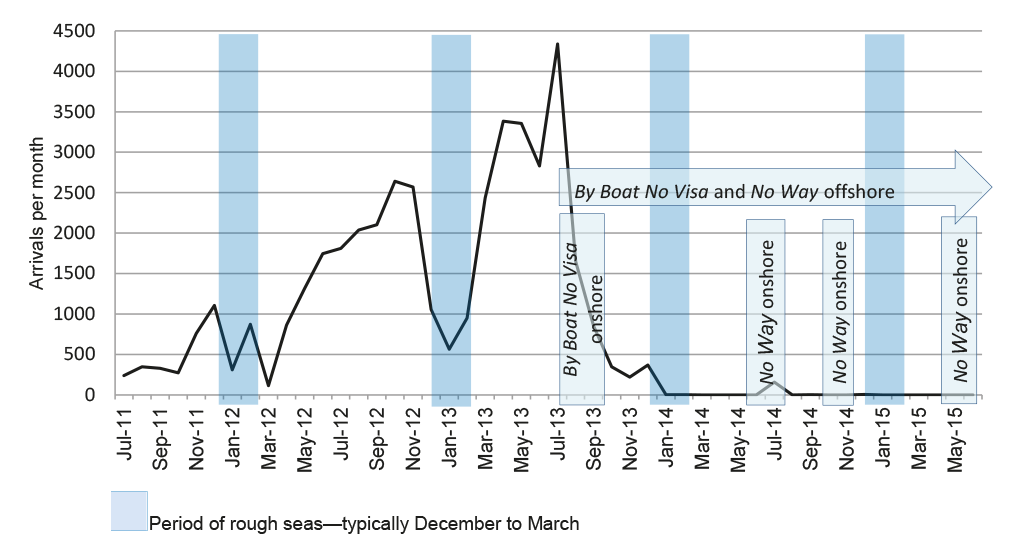

30. The department did not comply with all of the Special Minister of State’s conditions for exempting the By Boat, No Visa campaign from the guidelines. The campaign was granted an exemption from the 2010 Guidelines on the basis of extreme urgency, but was expected to: comply with the underlying principles of the Guidelines; place all advertising through the Central Advertising System; use suppliers from the Communications Multi Use List; and follow sound procurement and administrative processes. Conditions regarding the placement of advertising and the use of suppliers were complied with. The usual order of expenditure approval, contracting and service delivery was not observed in the procurement of media placement and research services.

31. The campaign was intended to communicate significant changes in migration policy primarily to diaspora communities within Australia, providing information which could then be passed on to families and friends back home. The onshore element of the campaign continued through much of the caretaker period for the 2013 federal election. While the Australian general public was a secondary audience for the campaign, almost 90 per cent of the campaign’s media placement was used for mainstream advertising (around $6.75 million of the $7.5 million expenditure). Both the onshore anti-people smuggling campaigns that preceded and followed the By Boat, No Visa campaign were targeted solely to specific diaspora communities. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection advised the ANAO that arranging advertising in culturally and linguistically diverse media had longer lead times and limited availability, therefore the department considered that mainstream advertising was necessary to immediately inform the target audiences and their influencers of the recently changed policy. Research completed just prior to the campaign found that mainstream media was a less preferred source of information for diaspora communities, behind: their family and friends; Internet sources, in-language television and radio, social media and community organisations.

32. Key elements of the guidelines, including the certification of the campaign’s compliance with the guidelines by the agency chief executive, were applied to the onshore elements of the No Way campaign. The chief executive certification for phase 3 was not signed prior to the launch of the campaign. The ANAO was advised that the non-compliance was due to an administrative oversight.

33. The offshore campaign elements reviewed by the ANAO delivered factual messages about Australian Government policy, and targeted potential illegal immigrants in source and transit countries. Spending decisions were well documented, except for activities organised for the offshore elements of the By Boat, No Visa campaign.

34. Evaluations were conducted for both onshore and offshore campaigns. Onshore, awareness of Australia’s policy on asylum seekers that arrive by boat, including those that professed to know something about the policy, remained reasonably constant at around 70 per cent, although confidence in the specific details of the policy softened over time. Almost half of those that had been in Australia less than five years had spoken to friends or family overseas about Australia’s migration policy. Offshore, surveys showed moderate to high awareness of Australian asylum seeker policy in regions with high numbers of potential illegal immigrants. The research also informed the department’s understanding of a range of issues relevant to irregular migration and assessed the quality of the services provided by communications contractors.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.15 |

That the Independent Communications Committee’s terms of reference be amended to provide the committee with the discretion to review advertising campaigns at any stage of development. Department of Finance response: Noted. |

Summary of entities’ responses

35. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor‐General Act 1997 was provided to the Department of Finance. Extracts of the proposed report were also provided to the Department of the Treasury, the Department of Education and Training and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Summary responses are provided below, with full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Finance

The Department of Finance (Finance) notes the ANAO’s audit report on Government advertising: March 2013 to June 2015.

The Government sets the governance arrangements for campaign advertising which are administered by Finance. The recommendation to amend the terms of reference of the Independent Communications Committee (ICC) is not a matter of administration, but is instead a policy matter for Government.

Department of the Treasury

The Treasury acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office’s draft report on Government Advertising: March 2013–June 2015 and welcomes the opportunity to review and provide comment in relation to the Intergenerational Report 2015 campaign extract.

In reviewing the extract the Treasury identified three key areas the ANAO highlighted in regards to compliance with the Guidelines on Information and Advertising campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities (Guidelines).

Campaign planning

The challenging timeframes for campaign development meant that Treasury had to develop a flexible campaign strategy to accommodate changing requirements. To implement the strategy, the department acted in accordance with decisions made by the Service Delivery and Co-ordination Committee (SDCC) as part of their regular review of campaign materials.

Procurement

Comments have been provided against your concerns in relation to our procurement processes in the response letter, in particular reflection of SDCC decisions in documentation and AusTender listings. The department will look at where improvements can be made for any future campaigns.

Evaluation

The Treasury would welcome the inclusion of specific targets to measure campaign effectiveness across all government communication strategies and more robust work being done on the evaluation of government campaigns and how these campaigns are evaluated by review committees.

Department of Education and Training

The Department of Education and Training (‘the department’) acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) report on the Government Advertising: March 2013 to June 2015.

The campaign’s objectives were to:

- counter myths and misconceptions about the current higher education system

- raise awareness of government support for higher education and the mechanisms that will remain in place into the future

- set the scene for the reforms, and

- encourage audiences to seek further information about current government resources, assistance and financial support for Australian higher education.

The responsible officials set these campaign objectives as they were appropriate for the policy nature of the campaign focus. The objectives related to awareness−raising or ‘attitudinal’ outcomes, as distinct from behavioural outcomes.

Evaluation of such campaigns relies on measuring pre and post campaign awareness levels in target audience (per campaign messaging) and the performance of campaign communication channels. This approach accords with best practice in the communication-marketing sector.

The department also notes the campaign research evaluation found that:

- Phase 1A of the campaign reached about 41 per cent of the population at a cost of about $0.47 per person reached

- Phase 1B of the campaign reached about 36 per cent of the population at a cost of about $0.43 per person reached, and

- that these per person cost figures place the campaign in the “high efficiency” category.

Performance of the campaign’s digital channels is another indicator of the success of the campaign. The ANAO noted this performance on page 224 of the report.

The department further notes that full disclosure of the evidence provided to the ANAO does not appear to be reflected in the final audit report.5 The department took into consideration a number of information sources alongside departmental estimates when certifying the statements of the campaign. This included consideration of current arrangements where differential government contributions occur; public statements of proposed fees in a deregulated market made by some universities and private provider peak bodies; and analysis of current fees charged by non−university higher education providers.

The department also notes that the ANAO’s compliance finding in relation to procurement policies and procedures and adds the following detail to accurately convey the degree of the infringement. Out of the campaign’s six procurement activities (comprising some 3,000 plus pages of documentation), the department was only unable to source:

- one email to the successful tenderer for developmental research, and

- two emails relating to notification to the PR companies that quoted for work (noting this work did not proceed).6

Further, of the six campaign−related contracts, two were reported within the required 42 days with the remaining four were reported within 50 days after commencement, eight days later than stipulated by the APS procurement guidelines.

The department accepts the ANAO’s findings in relation to its record−keeping practices. Significant work has been undertaken by the department to address these findings and was the focus in advertising campaigns developed since this one.

The findings highlighted in the ANAO audit will help contribute to strengthening the administration of campaign advertising in the future.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection acknowledges and appreciates the efforts of the ANAO staff who conducted the audit. Thank you for providing the Department with the opportunity to review and respond to this report.

The Australian Government’s anti-people smuggling communication campaign has been a key element in the success of Operation Sovereign Borders in significantly reducing the number of illegal maritime ventures to Australia.

The Department acknowledges that there was some non-compliance with procurement policies and procedures in relation to media placement and research services for the By Boat, No Visa campaign that ran from July to September 2013.

This campaign ran through much of the caretaker period for the 2013 Federal election and as such was granted an exemption from the 2010 advertising guidelines based on the extreme urgency to inform diaspora communities regarding the change in government policy. Mainstream media was used because booking advertising in culturally and linguistically diverse media had longer lead times and limited availability.

The Department has improved procedures since 2013 which is supported by the findings of the report which did not identify any further non-compliance.

1. Background

The Australian Government campaign advertising framework

1.1 The Special Minister of State (SMOS) is responsible for the administration of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework, and is supported by the Department of Finance (Finance).

1.2 The Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework was amended in 2008 with the introduction of new principles-based guidelines. Entity chief executives were responsible for certifying that advertising campaigns complied with the guidelines. The chief executive certification was also informed by third-party review of a campaign’s compliance with the guidelines by the Auditor‐General, based on a limited assurance approach. Further changes were made in 2010 following a review of the arrangements.7 The changes included new guidelines and the introduction of an Independent Communications Committee (ICC), which replaced the Auditor-General as the third-party reviewer.

1.3 In late 2013 the government introduced short-term interim guidelines, while it considered its long-term approach to information and campaign advertising. The ICC was disbanded and chief executives were to provide their certifications to the relevant Minister, who would seek endorsement from the SMOS prior to the launch of a campaign. In late 2014, the government reintroduced the ICC as a third-party reviewer, and released revised Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities (the 2014 Guidelines). The 2014 Guidelines were modelled on the 2010 Guidelines, and include three underlying principles and five sets of more specific principles.

|

Box 1: The underlying principles governing the use of public funds for all government campaigns, and the five information and advertising campaign principles. |

|

The underlying principles are that:

The following five principles set out the context in which Commonwealth Government campaigns should be conducted:

|

Note a: Australian Government, Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by non-corporate Commonwealth entities, Department of Finance, 2014. Available from <http://www.finance.gov.au/advertising/campaign-advertising/guidelines/> [accessed 11 May 2015]. Each of the five information and advertising principles has supporting explanatory notes.

1.4 Finance publishes the guidelines and provides further guidance and advice to entities through its website and Communications Advice Branch.8 Finance also administers the Central Advertising System (CAS), which is a coordinated procurement arrangement to consolidate government advertising expenditure and buying power to secure media discounts. Under the CAS, Non-Corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 are required to contact the government’s Master Media Agency to place their advertising.

Previous audits

1.5 Campaign advertising has been the subject of a series of ANAO performance audit reports since 1995.9 In 2010, the Australian Government requested that the Auditor-General undertake an annual performance audit of at least one campaign or the administration of the campaign advertising framework. Key findings of the ANAO’s reports have included:

- departments faced significant challenges prior to 2008 in effectively developing campaigns, as a result of responsibilities for key decisions being fragmented between the Ministerial Committee on Government Communications and departments;

- a ‘general softening’ in 2010 of the application of requirements on entities; and

- a number of areas of non-compliance in selected campaigns, including in: the recording of approvals; the accuracy of campaign statements; the presentation of campaign materials in an objective manner; the assessment of the cost-effectiveness of media buys; and adherence to relevant procurement policies.

1.6 ANAO Audit Report No. 54, 2012–13 observed that the certification process and third party review applying since 2008 had promoted compliance with the campaign advertising framework, although there remained scope to further refine and strengthen the framework. The audit also observed that the campaigns examined tended to push the boundaries of the guidelines in some areas. The audit drew attention to the emerging risk of campaign advertising not clearly meeting the enhanced expectations and arrangements established in 2008, and highlighted that the arrangements needed to be supported by Ministers so that advertising campaigns were meeting the genuine information needs of citizens.

Audit approach

1.7 The objectives of the audit were to:

- assess the effectiveness of the ongoing administration of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework; and

- assess the effectiveness of the selected entities’ administration in developing advertising campaigns and implementing key processes against the requirements of the campaign advertising framework applying at the time, and relevant legal and government policy requirements.

1.8 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- the effectiveness of Finance’s overall administration of the campaign advertising framework, including its advice to entities on framework developments;

- progress made towards addressing any outstanding recommendations from previous ANAO audit reports on government advertising;

- compliance of the specified campaigns with the relevant campaign advertising framework, including the 2010, 2013 (interim) or 2014 guidelines where they apply, and compliance with relevant procurement and legal requirements; and

- where the campaign advertising guidelines do not apply, whether entity processes applying to specified campaigns have promoted the achievement of value for money10 in respect of the campaigns.

1.9 The audit examined developments in the administration of the government campaign advertising framework from the end of the period examined by the previous audit (March 2013). In addition, three campaigns were selected for review, specifically the:

- Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign conducted in 2015, and administered by the Department of the Treasury (Treasury);

- Higher Education Reforms Communication campaign conducted in late 2014 and early 2015, and administered by the Department of Education and Training (Education)11; and

- anti-people smuggling advertising campaigns conducted both within Australia and overseas since 2013, and administered by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP).

1.10 The audit methodology included:

- interviews of relevant entity staff and review of campaign documentation, including: briefs to the relevant Ministers and departmental secretaries; campaign materials and supporting compliance documentation; research and evaluation reports; and procurement and legal documentation;

- review of relevant Cabinet records; and

- review of Finance’s correspondence and briefings with the SMOS, and examination of Finance’s actions in response to previous ANAO recommendations.

1.11 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $511 380.

2. The Australian Government campaign advertising framework

Areas examined

This chapter examines the evolution of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework, and the implementation of the recommendations of previous audits of government advertising. A comparison of the current framework with those applying in other jurisdictions is also considered, along with a summary of campaign advertising expenditure over time.

Conclusion

Between November 2013 and February 2015, the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework was weaker than it could be, due to the suspension of the third-party advisory process. The process was re-established in early 2015 with the appointment of a reconstituted Independent Communications Committee, but the early timing of the committee’s review of campaigns means that it is not in a position to provide a high level of confidence to entity chief executives—and by extension the Parliament and community—regarding a campaign’s compliance with the guidelines. At present, the committee reports on whether a campaign is ‘capable’ of complying with the guidelines, as it does not review final campaign materials and other relevant information. The committee’s terms of reference should be amended to enable its review at any stage of a campaign’s development.

Campaign expenditure increased in the periods prior to the 2013 and 2016 federal elections, continuing a long-term trend. Average Australian Government expenditure each financial year since 2008–09 on advertising campaigns has been $186 million.a In 2013 and 2016 approximately $100 million and $95 million respectively, was spent on media placement alone in the three months leading up to the caretaker period.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the Independent Communications Committee’s terms of reference should be amended to enable its review at any stage of a campaign’s development. There would also be benefit in the chief executive certification template being amended to reflect instances where Ministers provide financial approvals.

Note a: This expenditure included media placement, communications suppliers and GST, but not departmental costs incurred in campaign development or the cost of the Independent Communications Committee.

In the context of an evolving campaign advertising framework since 2013, are roles and responsibilities clear, and do review processes provide assurance to decision-makers?

The ANAO’s review of developments since 2013 indicates that:

- roles and responsibilities under the campaign advertising framework could be made clearer by amending the chief executive certification template to reflect instances where Ministers provide financial approvals; and

- the compliance advice provided by the current Independent Communications Committee is limited compared to what has been provided in the past.

In mid-2014, the government established a Service Delivery and Coordination Committee to oversee and review campaigns. The Committee took on a decision-making role in the development and approval of large campaigns, including the selection of communications suppliers and refining and approving final advertisements and media buys. The chief executive certification template should be amended to reflect instances where Ministers provide financial approvals.

Short-term interim arrangements for campaign advertising were in place between November 2013 and February 2015, applying to 17 campaigns. The interim arrangements did not include third-party review of campaigns’ compliance against the guidelines. Campaigns were endorsed in writing by the Special Minister of State. In contrast with the Independent Communications Committee process, which involved the public release of its advice to entities, the Special Minister of State’s endorsements were not released publicly.

The 2014 Guidelines reintroduced the Independent Communications Committee as a third-party adviser, however it provides more limited compliance advice than its predecessors. Under its terms of reference, the current committee reviews campaigns once and at an early stage of campaign development, and reports on whether campaigns are ‘capable of complying with Principles 1 to 4 of the Guidelines’. The committee does not review final campaign materials. The committee had previously been required to form a view and advise entity chief executives about a campaigns’ compliance. The current committee has raised these limitations with the Department of Finance, and the ANAO has made a recommendation on this matter.

November 2013—Short-term Interim Guidelines

2.1 The Special Minister of State (SMOS) introduced Short-term Interim Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by Australian Government Departments and Agencies in November 2013, while the incoming government considered its long-term approach to information and campaign advertising.12 The interim guidelines maintained the five information and advertising principles, and the certification of campaigns (of $250 000 or more) by the responsible chief executive against those principles.13

2.2 The interim guidelines did not continue the role of an Independent Communications Committee (ICC) to provide third-party advice on campaigns’ compliance with principles 1 through 4, as had occurred since 2010. Instead, chief executives were to provide their certification to the relevant Minister, who would seek endorsement from the SMOS prior to the launch of a campaign.

2.3 The SMOS, or his representative14, provided 35 endorsements across 17 campaigns in the period from November 2013 to the end of January 2015. The specifics of the SMOS’s role in endorsing advertising campaigns were not formally defined or documented, but each endorsement seen by the ANAO followed a consistent process. Entities provided the Department of Finance (Finance) and the SMOS with a media plan, final creative materials, relevant research, and the entity CEO’s certification. Finance then prepared a brief for the SMOS outlining any key issues. Finance’s advice commonly focussed on whether the campaign was appropriately supported by the research.

2.4 On occasion, the SMOS endorsed campaigns on the basis that certain conditions were to be met. Examples included: that final advertisements be provided to Finance with minor amendments made; and that planned media spends be reduced in the case of the Defence recruitment campaigns.15 On average, the time between a Minister seeking and receiving endorsement from the SMOS was 11 days. The SMOS communicated his endorsements confidentially and in writing. ICC review letters had been released publicly.

October 2014—Government review and approval of campaigns

2.5 In July 2014, the government agreed that the Service Delivery and Coordination Committee (SDCC) would oversee and review government advertising campaigns. In October 2014, the government agreed the specific processes for campaign review and approvals, involving the four stages summarised in Table 2.1. Where new funding was required for a campaign, approval was first sought from the Expenditure Review Committee.

Table 2.1: Summary of the government review and approval process—2014

|

Stage |

Process |

|

One |

Campaign proposal and research options. The responsible minister brings forward a campaign proposal including objectives, key messages, proposed media channels and budget. The minister also brings forward a market research brief and list of potential suppliers (potential suppliers are to be drawn from the Communications Multi-Use List (CMUL) and informed by advice from Finance). If the SDCC agrees that the campaign proceed, the responsible entity issues the brief to research suppliers, and selects a supplier. Developmental research is then undertaken to inform a communications strategy. |

|

Two |

Approval of campaign communications strategy by the SDCC and agreement to commence the procurement of creative agencies and other suppliers (such as public relations). The SDCC considers the communications strategy, research findings and a proposed list of suppliers for advertising and public relations (potential suppliers are again drawn from the CMUL and informed by advice from Finance). If there is agreement by the SDCC to proceed to the next stage, the entity issues briefs to suppliers. For advertising, the research supplier tests all of the submitted advertising concepts. The entity identifies a shortlist of advertising agencies who offer value for money, informed by the testing. |

|

Three |

Creative agency selection. The SDCC considers creative concepts of shortlisted agencies. If there is SDCC agreement to proceed, the entity proceeds to develop the preferred concept and conducts further testing research on the proposed campaign material. |

|

Four |

Refinement of pre-production advertising materials and media plans. The SDCC considers refined campaign materials and a final media plan. If the SDCC agrees to proceed, the entity finalises materials, books media and tests materials to check their effectiveness. Any subsequent changes to materials or media plans may require additional review by the SDCC. |

Note: The ICC’s review of a campaign occurs between stages one and two.

Source: ANAO summary Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet documentation.

2.6 The government’s campaign review process was refined in March 2015. The SDCC would review only campaigns considered to be ‘complex/sensitive’, with ‘operational/routine’ campaigns to be considered by the SMOS.16 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet provided information to entities in July 2015 to formally advise them of the campaign review process.

2.7 In late January 2015 Finance advised the SMOS that ministers (or groups of ministers) can make procurement decisions, but it was important that the responsibility for approving campaign expenditure was clear.17 Finance advised the SMOS that if the SDCC chose suppliers, and approved the media buy, then the SDCC would be considered the approver under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act). Finance further advised that if responsibilities were not clear, legal uncertainty around the process could result in incorrect decisions being taken forward or outcomes not achieved. Finance also noted that the ANAO had previously been critical of spending decisions where it was not clear who the approver was. In the brief to the SMOS, Finance suggested that if the SDCC wished to undertake the role of approver, an amendment could be made to the chief executive certification template to ensure there was no ambiguity. Finance advised the ANAO that the SMOS had not returned the brief to the department, and no change had been made to the chief executive certification template. There would be benefit in Finance resolving this matter with the SMOS.

2.8 Section 71 of the PGPA Act provides for the approval of proposed expenditure by a Minister. Section 71 requires Ministers to: be satisfied, after making reasonable inquiries, that the proposed expenditure would be a proper use of the money; and record the terms of the approval in writing. The relevant SDCC minutes (and supporting documentation) for the selected campaigns fulfil these requirements. Finance has developed procurement guidance to entities undertaking campaigns. The guidance includes the following advice for procurements of communications suppliers undertaken by ministers:

Where a Cabinet committee or ministers take procurement decisions relating to campaigns, entities should document the process that was followed and keep a record of any advice it provided that was intended to assist the SDCC and/or its minister to make inquiries as to whether the proposed expenditure (i.e. procurement) constituted a proper use of resources. Entity officials will ultimately enter into the agreements with suppliers on behalf of the Commonwealth. In doing so, an official must also comply with their obligations under the PGPA Act and PGPA Rules and proper documentation will support them to do so.18

2.9 Finance advised the ANAO that it considers that entity chief executives remain capable of certifying against Principle 5 of the guidelines, provided that their entities have followed prevailing procurement policies and procedures.

February 2015—New guidelines and the reintroduction of an Independent Communications Committee

2.10 The SMOS announced revised arrangements for the oversight of information and advertising campaigns in December 2014, including that ‘proposed campaigns with expenditure in excess of $250 000 will continue to be considered by an Independent Communications Committee’. The changes were to take effect from 1 February 2015, with appointments to the ICC to be ‘made in due course’.19

2.11 ICC appointments were not finalised until 2 March 2015 and the ICC reviewed its first campaign on 31 March 2015. In the period between the end of the interim arrangements and the commencement of the ICC, six campaigns launched which were not subject to third-party review.20 Finance advised the ANAO that: five of these campaigns had progressed to the point of launch before the ICC was convened; and one campaign (anti-people smuggling) involved the reuse of materials previously endorsed by the SMOS under the interim guidelines.

The role of the Independent Communications Committee

2.12 The 2014 Guidelines provide that, for campaigns of $250 000 or more, the ICC will consider the proposed campaign and provide a report to the responsible chief executive on compliance with Principles 1, 2, 3 and 4 of the Guidelines. Entities are responsible for providing a report to the chief executive on compliance with Principle 5.

2.13 The ANAO reviewed the minutes and supporting documentation for ICC meetings from March to mid-August 2015 (spanning the ICC’s first 13 meetings). During that period, the ICC finalised 15 review reports with all campaigns considered ‘capable’ of complying with the guidelines. In a few cases, the ICC sought revision of materials or further specific information from departments, which were considered out of session, and before the finalisation of the relevant review report. Of the campaigns selected for this audit, only Phase 2 of the IGR 2015 campaign was reviewed by the current ICC (see discussion from paragraph 3.8). The ICC meeting minutes indicate that the review process involved discussion of a range of potential compliance issues with entities. For example, for a number of campaigns the ICC explored the legislative and policy underpinnings of the subject matter (Principle 1), and examined the alignment of the campaign strategy and any developmental or other research (Principle 4).

2.14 The revised arrangements involve fewer meetings of the ICC. The current ICC reviews campaigns once, and at an early stage of campaign development.21 The committee does not review final campaign materials, and reports only on whether campaigns are ‘capable of complying with Principles 1 to 4 of the Guidelines’ [ANAO emphasis added].22 In previous audits of government advertising arrangements, the ANAO observed that the former ICC: had reviewed campaigns at multiple stages; had considered final campaign materials; and had formed a view and advised on a campaign’s compliance with Principles 1 to 4. The current ICC has advised Finance that there are ‘limitations to providing compliance advice, particularly in relation to Principles 2 and 4, given the early point in time that they were reviewing campaigns, when media strategies and materials are still in development, and without reviewing campaign advertisements.’23 The ICC’s current advice—whether a campaign is ‘capable’ of compliance—provides limited value as campaigns will undergo further development following ICC review.

Recommendation No.1

2.15 That the Independent Communications Committee’s terms of reference be amended to provide the committee with the discretion to review advertising campaigns at any stage of development.

Finance response: Noted.

2.16 The Department of Finance (Finance) notes that the governance of campaign advertising, including the terms of reference set for the Independent Communications Committee, is a matter for the Government.

Have the recommendations of previous performance audits been acted upon?

A previous (2011–12) ANAO recommendation to clarify which parts of the guidelines are mandatory has not been fully addressed. Finance released explanatory guidance in early 2015 which went some way towards providing clarification, however numerous provisions of the advertising guidelines contain the word ‘should’ despite Finance’s general advice to entities that the word ‘should’ is best avoided in regulatory and guidance documents. By failing to fully address the recommendation, there remains a lack of clarity around which parts of the advertising guidelines are mandatory. Four of the five information and advertising principles contain the word ‘should’, including Principle 3 which provides that ‘campaigns should be objective and not directed at promoting party political interests’.

Two further recommendations were directed towards Finance in the ANAO’s 2012–13 audit of government advertising. One recommendation related to the development of guidance for entities in the event that they propose to undertake campaigns relating to the views, policies or actions of other parties. Finance has prepared relevant guidance for provision on an ad hoc basis. It has not been published.a

Note a: Finance did not agree to the second ANAO recommendation to improve transparency through consolidated reporting of the full costs of campaigns. Finance advised the ANAO that it has not accepted this recommendation, on the basis that consolidated totals of media and other expenditure on campaigns can be derived from information published in Finance’s annual reports on campaign advertising.

2.17 A recommendation from ANAO Report No 24, 2011–12, Administration of Government Advertising Arrangements: March 2010 to August 2011 was directed towards Finance clarifying which parts of the guidelines were mandatory. In early 2015, Finance published the following explanatory guidance on its website along with the 2014 Guidelines:

Within the Guidelines, where the word ‘must’ is used, it signals that there is a mandatory requirement. Where the phrase ‘must not’ is used, it signals that certain actions or practices are not to be undertaken by entities or officials. Actions or practices that relate to the sound administration of campaigns in order to demonstrate compliance with the Guidelines are denoted by the word ‘should’.24

2.18 This guidance is helpful at a high level, but does not directly address the issue raised: the overarching principle states that ‘campaigns should be objective and not directed at promoting party political interests’, while the three sub-principles use the word must. In a further and related development, the 2015 Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation25 recommended that Finance ‘develop, in consultation with key regulators, a short guide to promote clarity and consistency in language used in regulatory and guidance documents’. Finance’s guide, released in late 2015, advises that the word ‘should’ is best avoided, as it has been incorrectly interpreted to imply mandatory requirements, even where the use of the term has been defined in the document as meaning good practice and not mandatory.26 This advice is in contrast with the advice on government advertising, as the word ‘should’ is used extensively throughout the current advertising guidelines. By failing to fully address the recommendation, there remains a lack of clarity around which parts of the guidelines are mandatory. Four of the five information and advertising principles contain the word ‘should’. Principle 3 provides that ‘campaigns should be objective and not directed at promoting party political interests’, but its three sub-principles each contain the word ‘must’. Finance advised the ANAO that no entity has ever sought Finance’s advice or assistance to clarify the meaning of the terms ‘should’, ‘must’ and ‘must not’ within the Guidelines.

2.19 Audit Report No. 54, 2012–13, Administration of Government Advertising Arrangements: August 2011 to March 2013 made two recommendations, both directed towards Finance. Finance did not agree to a recommendation to improve transparency through consolidated reporting of the full costs of campaigns.27 Finance did agree to a recommendation to clarify the application of paragraph 28(b) of the 2010 Guidelines (which relates to campaigns not directly attacking or scorning the views, policies or actions of others).

2.20 Finance advised the ANAO that it has developed guidance to provide to entities in the event that they propose to undertake campaigns relating to the views, policies or actions of other parties. In summary, the advice is that the guidelines do not prevent the use of campaigns to address information issued by others; but such campaigns may face an increased risk of being perceived not to fully comply with the guidelines and accordingly, entities should take care to ensure that advertisements avoid references to other parties and the emphasis should be on communicating about matters for which the Australian Government is responsible. Publishing such guidance on Finance’s website would promote transparency. Finance advised the ANAO that:

- it will continue to provide this guidance to entities where it is relevant, reflecting that campaigns dealing with the views, policies or actions of other parties have been undertaken extremely infrequently; and

- it considers that publishing such advice could have the unintended consequence of normalising this type of campaign.

How does the current Australian Government campaign advertising framework compare with similar international and state frameworks?

The ANAO’s comparison of the current Australian Government framework with arrangements applying in other jurisdictions indicates that while there is a common approach in some key respects (for example, in seeking to prohibit party political content and ensure factual accuracy), a number of key differences exist. A number of jurisdictions have adopted restrictions on: Ministerial direction of entities; the subject matter of campaigns; and conducting campaigns during caretaker periods. Some frameworks also had requirements intended to avoid ‘excessive’ or ‘extravagant’ advertising.

2.21 The comparison28 identified that while there was consistency in some key respects (for example, in seeking to prohibit party political content and ensure factual accuracy), there were five key differences. These included:

- accountability arrangements—in some frameworks, government entities are primarily tasked with developing campaigns in compliance with the relevant standards, and heads of entities are not subject to the direction of Ministers. While the involvement of committees in campaign development was also reasonably common, these tended to consist of communications experts and were more advisory in nature;

- restrictions on campaign subject matter—under some frameworks, the subject matter was limited to communicating on public health and safety matters, maximising compliance with laws, and/or encouraging the use of government products and services. Other frameworks required a clear purpose for a campaign, such as where governments have a legal duty to provide people with information, or where advertising is critical to the effective running of the government. One framework does not allow for the promotion of government initiatives that have yet to gain Parliamentary approval;

- explicit focus on cost-effectiveness and efficiency—some frameworks had requirements that advertising not be ‘excessive’ or ‘extravagant’; mandated the conduct of cost benefit analyses29; or required that entities allow for reasonable and realistic timeframes to develop campaigns;

- role of research in developing campaigns—some frameworks require the use of research (such as developmental research and/or creative concept testing) in the development of campaigns (noting that most frameworks encourage the use of evaluation to assess campaign performance); and

- restricting campaigns during election caretaker periods—some frameworks prohibited the continuation of campaigns during caretaker periods, unless they related to public health and safety issues.30

How much is spent on campaign advertising?

Between 2008–09 and 2014–15, Australian Government expenditure on advertising campaigns averaged $186 million each financial year. This expenditure included media placement, communications suppliers and GST, but not departmental costs incurred in campaign development or the cost of the Independent Communications Committee. ANAO analysis shows a tendency for campaign expenditure to increase significantly in the lead up to a federal election. Increased expenditure has been observed prior to the last five elections. In 2013 and 2016 around $100 million and $95 million respectively, was spent on media placement alone in the three months leading up to the caretaker period.

2.22 Figure 2.1 shows campaign advertising expenditure from 2008–09 to 2014–15 for: media placement; ‘consultants, services and other costs’; and GST. In total, over $1.3 billion was spent on these components of campaign advertising over seven financial years, an average of $186 million per financial year. These figures do not include departmental costs incurred in the development of campaigns or the cost of the ICC.

Figure 2.1: Campaign advertising expenditure, 2008–09 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO, collated from information in Finance’s campaign advertising reports, see: <http://www.finance.gov.au/advertising/campaign-advertising-reports.html>.

2.23 Figure 2.2 provides information on monthly media expenditure from January 2000 to June 2016. The analysis indicates that campaign media expenditure increased in the lead up to the last four federal elections.

2.24 The ANAO also collated the amounts paid to communications suppliers for advertising campaigns conducted from 2012–13 to 2014–15. The ten suppliers who were paid the highest amounts for their work on campaigns are shown in Appendix 2.

Figure 2.2: Monthly campaign expenditure on media placement—June 2016 prices

Notes: Data for the period 2000 to 2012 is sourced from ANAO Audit Report No. 54, 2012–13 and is based on data from Finance. Data for the period 2013 to 2016 was also provided by Finance. Data from 2000 to 2003 aggregates media placement expenditure by Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) agencies, Commonwealth Authorities and sCompanies Act 1997 bodies, and Territory Governments. Data from 2004 to June 2014 is the campaign advertising media expenditure by FMA Act agencies only; data since July 2014 relates to spending by non-corporate Commonwealth entities under the PGPA Act

Source: ANAO, drawing on Finance data and Australian Bureau of Statistics Catalogue 6401.0.

3. Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign

Areas examined

This chapter provides an overview of the Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign, and examines the operation of the review, certification and publication processes and the tracking and evaluation of the campaign’s effectiveness.

Conclusion

The Treasury Secretary’s certification that the campaign complied with the 2014 Guidelines was underpinned by detailed advice from the department. The ANAO’s review of the information supporting that advice indicated that there were some shortcomings in advice and departmental processes relating to compliance with procurement policies and procedures.

Areas for improvement

There would be benefit in Treasury reviewing its procurement processes to ensure that future campaigns comply with relevant procurement policies. For future campaigns Treasury should also develop specific targets to measure achievement of campaign objectives.

Campaign Overview

3.1 The Australian Government is required to produce an Intergenerational Report (IGR) every five years under the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998. IGRs assess how changes to Australia’s population size and age profile may impact economic growth, workforce and public finances over the next 40 years. The 2015 IGR, released on 5 March 2015, was the fourth intergenerational report to be produced. Previous reports were released in 2002, 2007 and 2010. The 2015–16 Commonwealth Budget was announced on 12 May 2015.

3.2 The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) was responsible for administering the Intergenerational Report 2015 Community Engagement campaign. The campaign launched in March 2015 and aimed to engage with and inform the community on the issues and challenges identified in the 2015 IGR. The campaign also sought to communicate how measures included in the 2015–16 Budget were linked to the IGR challenges. The campaign was subject to the 2014 Guidelines.

3.3 The key elements of the IGR 2015 campaign are summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Summary of the IGR 2015 Community Engagement Campaign

|

Campaign summary |

|

|

Objective/s |

Overarching objective: to engage with and inform the community on the issues and challenges identified in the Intergenerational Report. Further, the campaign was to provide an overarching narrative on the need to plan for the future. |

|

Timing |

Phase 1: 8 March to 28 March 2015 (Note: NSW/ACT from 29 March to 18 April 2015, due to the NSW state election). Phase 1(b): from 19 April to 2 May 2015. Phase 2: from 26 May to 27 June 2015. |

|

Target audiences |

All Australians. Small businesses were also a specific target audience for Phase 2. |

|

Media channels |

The campaign employed television, radio, newspapers, search engine marketing, online television, digital display and mobile, cinema, Out of Home (for example Billboards), as well as channels to reach Indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse Australians. |

|

Total campaign budget and expenditure (inc. GST) |

The campaign had an original budget allocation of $36.2 million, which was later adjusted to $35.1 million. $1.1 million was redirected by the Government for a campaign in South Australia on Age Pensions and Pensioner Concessions. Expenditure: $31.5 million, as at 31 December 2015. |

|

Media and other expenditure (inc. GST) |

Media placement: $23.6 million. (Phase 1: $8.5m, Phase 1b: $4.5m and Phase 2: $10.5m). Creative agency: $6.4 million; Research and evaluation: $1.2 million; and Public relations: $0.4 million. |

Source: ANAO, from Treasury documentation.

Campaign development and approval

3.4 In late November 2014, Treasury procured developmental market research to ‘gauge community understanding of how economic choices and trade-offs affect the Australian community’. The department advised the Treasurer in late December 2014 that the research had found, ‘that framed in the right way, all segments of the community are keen to engage in a discussion on the future of the Australian Economy’. The Treasurer agreed to Treasury’s recommendation to proceed with the development of an advertising campaign.

3.5 The Service Delivery and Coordination Committee (SDCC) reviewed the campaign on 14 occasions. The committee approved the campaign communication strategy, selected the creative and public relations agencies, and approved the finalisation of the creative materials and media plan.

3.6 The campaign communication strategy, approved by the SDCC, outlined a plan to deliver the campaign in four phases. The first phase would coincide with the release of the 2015 IGR, the second and third phases would bookend the 2015–16 Commonwealth Budget, and a fourth phase would follow some months after the Budget. The first phase sought to use the IGR as a platform to raise public awareness and understanding of economic and social challenges. The focus of the phases bookending the Budget was not articulated and the subject matter and timing of the fourth phase were not defined.

3.7 The Treasurer approved the launch of the campaign’s first phase on 8 March 2015, after the release of the IGR on 5 March 2015. Instead of conducting a second and third phase to bookend the Budget, the SDCC approved the extension of the first phase in mid-April 2015, for a further three weeks (‘Phase 1b’). The Treasurer approved the launch of Phase 2 on 26 May 2015, two weeks after the release of the 2015–16 Commonwealth Budget. The campaign was originally planned to communicate information on small business, jobs and childcare measures included in the Budget (and how those measures linked to the IGR challenges). Only advertisements concerning the small business measures were approved for launch.

Were the guidelines applied?

The Treasury Secretary certified that the campaign complied with the 2014 Guidelines. The ANAO’s review of the information supporting the certification indicated that there were some shortcomings in advice and departmental processes relating to compliance with procurement policies and procedures.

The Treasury Secretary’s certification that the campaign complied with the 2014 Guidelines was underpinned by detailed advice from the department. It was also supported by a number of other inputs such as research and legal advice. As the Independent Communications Committee had not yet started to operate the first phase of the campaign was not subject to third party review against the 2014 Guidelines.

The initial campaign budget was informed by Master Media Agencya advice, without campaign objectives having been specified. The campaign was designed in a manner that provided flexibility in the subject matter and timing of different phases of campaign activity. Some campaign materials were developed, at a cost of more than $1.7 million, which were not used. Treasury advised the ANAO that the materials were developed:

- in accordance with decisions of the Service Delivery and Coordination Committee; and

- having regard to the advice of the Independent Communications Committee.

Treasury further advised that as soon as relevant decisions were communicated it stopped work to minimise any additional spending.

In relation to Principle 5 (compliance with relevant procurement and legal requirements), Treasury’s procurement documentation did not reflect the Service Delivery and Coordination Committee’s substantive role in making key campaign decisions and providing financial approvals. The ANAO also identified areas in which Treasury did not follow procurement policies. Contracts for research services were not varied in a timely manner, and AusTender reporting was not always accurate.

Note a: The Master Media Agency is part of the Australian Government’s Central Advertising System, which consolidates government advertising expenditure to secure optimal media discounts. Under the system, the Master Media Agency assists in media planning, placement and rates negotiations with media outlets.

Campaign review, certification and publication processes

3.8 The Treasury Secretary signed the chief executive certification for the first phase of the campaign on 6 March 2015. The first phase of the campaign was not subject to SMOS or third party review against the Guidelines. Phase 1 was launched around five weeks after the 2014 Guidelines took effect, but the new Independent Communications Committee (ICC) had not yet started to operate. Finance had agreed that Phase 1 would not be reviewed by the ICC, as the campaign was well progressed at the time.

3.9 For the second phase, Treasury completed the ICC review, chief executive certification and publication requirements. The ICC was in place and on 20 May 2015 reviewed the campaign strategy, developmental research, draft media strategy, indicative media plan and the statement of compliance. The ICC concluded that the proposed second phase (small business component) was capable of complying with Principles 1 through to 4 of the Guidelines. On 3 June 2015, the ICC also reviewed materials for a planned ‘jobs’ component of Phase 2 of the campaign, but this component did not proceed. On the basis of the ICC’s advice, and the advice of Treasury officers, the Treasury Secretary certified the second phase of the campaign on 22 May 2015.

Basis for the chief executive’s certification against the five information and advertising campaign principles

Principle 1—was the campaign relevant to government responsibilities?

3.10 The subject matter of the campaign’s first phase was underpinned by legislative authority. Under the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998, the Australian Government is required to produce an IGR every five years. The subject matter of the second phase—the small business measures, were decisions of Cabinet announced as part of the Budget, and were intended to be implemented during the current Parliament (some of the measures were to take effect from 12 May 2015).

3.11 During the meetings held to consider components of Phase 2 of the campaign, the ICC suggested that Treasury ensure that the campaign website clarify that measures were subject to the passage of legislation. Treasury was supportive of this suggestion. Ultimately, the small business measures received bipartisan support and received royal assent on 22 June 2015. Treasury advised the ANAO that the risk that the jobs and childcare measures might not pass the Parliament (which was also raised by the ICC) had informed its decision to not proceed with those Phase 2 components.

Principle 2—was the campaign presented in an objective, fair and accessible manner, and designed to meet the objectives of the campaign?

3.12 Treasury’s relevant policy area reviewed the Phase 1 and 2 campaign materials. It advised that the materials were accurate and relevant sources could be cited for the information provided in the advertisements.

3.13 The campaign objective was to engage with and inform the community on the issues and challenges identified in the Intergenerational Report; as well as to provide an overarching narrative on the need to plan for the future. Nine rounds of concept testing were conducted to measure and refine the various campaign materials. Before the release of Phase 1 the researcher concluded that the campaign had transitioned well from concept to execution; with the creative approach, providing ‘a unique and engaging platform with almost universal appeal’. The researcher noted that ‘such big issues creates expectations that this is the start of a conversation that will play out over many months. Absence of further engagement or update would risk the campaign being dismissed as “window dressing”.’

3.14 In relation to Phase 2 (small business only) campaign materials, testing was less positive overall. Testing indicated that the materials were working adequately, typically with only minor refinements required. Testing was also conducted for campaign materials for the jobs and childcare elements of Phase 2 (which were work in progress at the time).

Principle 3—were the campaign materials objective and not directed at promoting party political interests?