Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Funding and Management of the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the arrangements established by the Department of the Environment for the funding and management of the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Murray–Darling Basin (the Basin) is an area of national environmental, economic and social significance. The Basin comprises Australia’s three longest rivers—the Darling, the Murray and the Murrumbidgee—and nationally and internationally significant wetlands, billabongs and floodplains. The Basin as a whole covers one‐seventh of Australia’s land mass and extends across four states—Queensland, New South Wales (NSW), Victoria and South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory (the Basin states). Thirty‐nine per cent of Australia’s national income derived from agricultural production is generated in the Basin, and it is home to over two million people.1

2. Throughout much of the twentieth century, the natural flows of the river systems in the Murray–Darling Basin were disrupted by the construction of infrastructure and the allocation of water resources for irrigation, livestock and domestic supply. It is now recognised that irrigation infrastructure and an over‐allocation of water for consumptive use are having unintended environmental consequences.2 Over time, reduced flows have caused a range of significant environmental problems, including: increased salinity and algal blooms; diminished native fish and bird populations; and poor wetland health.3

Water reform

3. Over a number of years there have been significant reforms aimed at improving the management of water resources and addressing the imbalance between consumptive and environmental water use in the Basin, including the: Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG’s) agreement to the National Water Initiative (NWI) in 2004—Australia’s blueprint for water reform, and the commencement of the Water Act 2007 in March 2008.

4. On 3 July 2008, the Australian Government and the Basin states signed an Inter-governmental Agreement on Murray–Darling Basin Reform (the IGA). The IGA aimed to increase the productivity and efficiency of Australia’s water use, to service rural and urban communities, and to ensure the health of river and groundwater systems. The IGA provides for the Basin states and the Australian Government to enter into Water Management Partnership Agreements (WMPAs) to ‘give effect to the urgent need to undertake water reforms in the Basin, to deliver a sustainable cap on surface water and groundwater diversions across the Murray–Darling Basin and to ensure the future of communities, industry and enhanced environmental outcomes’.4

5. The Australian Government’s portfolio of water entitlements is intended to meet environmental needs, with diversions and extractions from the

Murray–Darling Basin to be reduced to sustainable levels by 2019 under the Basin Plan. To implement the required level of reductions in diversions and extractions, successive governments have committed to ‘bridging the gap’ by securing water entitlements for environmental use. The target for surface water recovery under the Basin Plan, or the volume of the ‘gap’, is 2750 GL.5

6. As part of the IGA on Murray–Darling Basin Reform, Australian, state and territory governments agreed to develop State Priority Projects (SPPs). The SPPs were to deliver substantial and lasting returns of water to the environment, secure the long term future for irrigation communities, and deliver value for money outcomes. The funding for SPPs has been provided under the Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program (SRWUIP). To date, SPPs have been funded in each of the Basin states with project funding ranging from $7 million to $953 million, with individual water entitlements purchased from these funds ranging from 0.5 GL to 133 GL.6 The largest acquisition by the Australian Government of water entitlements under an SPP was the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project (Nimmie-Caira project).

Nimmie-Caira project

7. In July 2012, the NSW Government submitted a business case to the Australian Government seeking funding for the Nimmie-Caira project as an SPP.7 The business case identified around 32 000 hectares of water-dependent vegetation on the Nimmie-Caira site, including red gum and black box communities and sensitive wetlands. The business case also identified the potential to restore cleared land and floodways to re-connect and re-integrate areas of water-dependent vegetation. It was recognised that the site had extensive irrigation infrastructure that could, with some modification, be utilised for watering high priority environmental sites within the local district, as well as downstream. The NSW Government proposed that 381 GL of supplementary water entitlements8, which equated to 173 GL of long-term average annual yield (LTAAY), would be transferred to the Australian Government to make a contribution towards ‘bridging the gap’ to the sustainable diversion limits (SDL) under the Basin Plan.9

8. The then Australian Government agreed to fund the Nimmie-Caira project in June 2013. Under a Heads of Agreement (HoA), the Australian Government agreed to provide up to $180.1 million to the NSW Government to purchase the land and water entitlements from 11 property owners in the Nimmie-Caira area, and for the NSW Government to undertake extensive infrastructure works and develop long term land management arrangements on the site. Under this agreement, the Australian Government would own the water entitlements previously held by the landholders while the NSW Government would own the land.

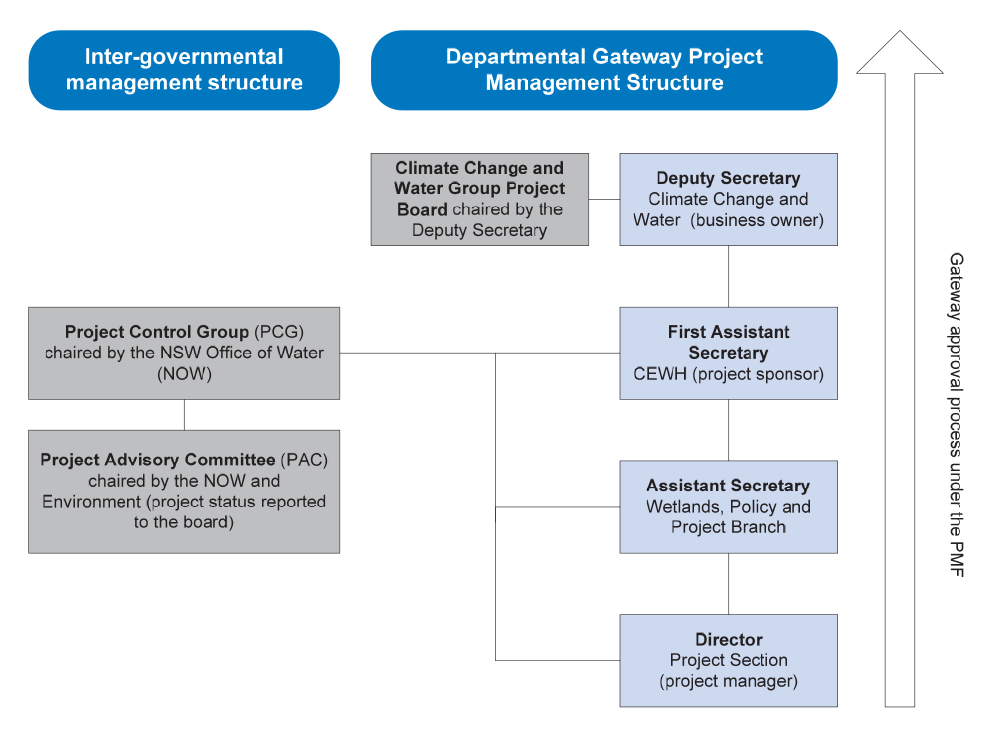

9. The Department of the Environment (Environment) is responsible for monitoring and funding the project, with Executive oversight provided through the department’s Climate Change and Water Group Project Board, chaired by a departmental Deputy Secretary. The New South Wales Office of Water (NOW) is responsible for the day-to-day project delivery. The implementation of the project is informed by a Project Control Group (PCG, involving representatives from Environment and the NOW) and a Project Advisory Committee (PAC, involving local community representatives as well as PCG members).

10. The achievement of the overall objectives for the Nimmie-Caira project is dependent on the NSW Government meeting the milestones established in the HoA and project schedule. As at December 2014, the Australian Government had provided $120 million to the NSW Government for the purchase price of land and water entitlements, with an additional $4.5 million provided following the completion of three project milestones.

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the arrangements established by the Department of the Environment for the funding and management of the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project.

12. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- appropriate arrangements to assess the merits of funding the proposed project were implemented; and

- sound arrangements for the management and delivery of the project were established.

13. In March 2013, the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport completed a report into the Management of the Murray-Darling Basin. In its report, the Committee recommended that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) review the Nimmie-Caira buyback proposal prior to its approval. In response to the recommendation, the Auditor-General advised the Chair of the Committee that an audit would not be undertaken at that time as the due diligence process was being completed by Environment and an audit had the potential to delay negotiations between the Australian and the NSW governments. Once the agreement between the Australian and NSW Governments was endorsed in 2013 and the transfer of water entitlements to the Australian Government was finalised in June 2014, an audit was scheduled to commence in the second half of 2014.

Overall conclusion

14. The Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project (Nimmie-Caira project) is a State Priority Project funded by the Australian Government to ‘bridge the gap’ between business-as-usual and more sustainable water diversions in the Murray−Darling Basin. The Australian Government approved $180.1 million in funding for the Nimmie-Caira project in June 2013. The project is to be completed in mid-2018. The 133 GL of water entitlements acquired by the Australian Government under the project represents the largest parcel of entitlements obtained across a range of programs and projects established to ‘bridge the gap’.10

15. The proposal to fund the Nimmie-Caira project as an SPP was outlined in a business case submitted to the Australian Government by the NSW Government in July 2012. The NSW Government initially sought funding of $185 million for the project, which incorporated $120 million sought by landowners for land and water entitlements, as well as funding for infrastructure works, land management arrangements and project management costs.11 The funding requested for the land and water entitlements ($120 million) was presented by the NSW Government on an ‘all or nothing’ basis—that is, the price was not negotiable.

16. Environment ‘market tested’ the $120 million asking price for the land and water entitlements using two independent valuers. The independent valuations obtained were subsequently subjected to a review by the then Australian Valuation Office (AVO). On the basis of this review, the fair market value for the land and water assets in current use was determined by Environment to be $103.1 million—meaning that the asking price included a price premium of $16.9 million.

17. Environment considered that, in the circumstances, an additional price premium was justified. The acquisition of water entitlements through the project avoided the higher costs of purchasing entitlements elsewhere in the Basin12 and provided a long term public benefit and value through the opportunity to create the largest wetland restoration project in the Murray−Darling Basin. The project also had the potential to provide less restricted13 environmental watering opportunities for priority sites in the local area with limited access and the opportunity to re-credit water after it had passed through the site to meet environmental watering priorities further downstream (the latter value was estimated by Environment at $11 million).14 A contribution from the NSW Government to the project of 10 per cent (in the form of an increase in water entitlements transferred to the Australian Government from another SPP) further offset the premium paid by the Australian Government for the land and water entitlements.15 In sum, Environment considered that the additional benefits exceeded the premium of $16.9 million over the estimated fair market value.

18. Overall, Environment established a reasonable basis on which to assess the fair market value of the land and water entitlements. The department initially obtained modelling from the Murray–Darling Basin Authority to confirm the reliability of the water supply over time (in the form of the long term average annual yield from the entitlement). Subsequently, advice was obtained from two private sector valuation firms, with additional scrutiny of this advice provided by the then Australian Valuation Office, to arrive at a fair market value of $103.1 million (comprising $44 million for the land and $59.1 million for the water entitlements). The department did not, however, seek an independent assessment of the premium ($16.9 million) to be paid over and above the assessed fair market value to meet the fixed asking price of $120 million for the land and water assets. Obtaining an independent opinion in relation to the value of the additional benefits would have provided greater assurance to the department and the Minister in relation to the merits of paying an additional premium over the assessed fair market value. Further, there was scope for the department to have subjected the remaining elements of the proposed project relating to offsets, project planning and management, and infrastructure configuration (valued at $60.1 million) to greater scrutiny as part of the due diligence process.

19. Environment’s advice to the decision-maker (the then Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities) was clear in terms of the price premium and the basis on which the department considered that it was justified. Over the course of the due diligence process, the department was also able to negotiate a modest reduction in the total funding initially sought for the project ($185 million), with $180.1 million ultimately approved. The funding decision by the Minister was appropriately documented and was made in accordance with the requirements for approving expenditure under the financial management framework. The decision to fund the project was made on the basis that the NSW Government was required to meet 31 conditions that were considered necesssary by Environment to manage the inherent risks identified for the project.16

20. The Heads of Agreement (HoA) between the Commonwealth and the NSW Government (incorporating the 31 conditions of approval) and separate project schedule of milestones, timeframes and payments provided an appropriate framework within which to deliver the project. The large upfront payment for the land and water entitlements did, however, reduce the leverage available to Environment to encourage timely performance by the NSW Government. Further, there has been limited information provided to stakeholders, including the local community, in relation to the delivery of the project and the anticipated outcomes from the substantial investment by the Australian Government.

21. To date, progress has been considerably slower than envisaged, with project implementation being pushed back by at least seven months, and critical project initiatives are now overdue. A key contributing factor to the delays was the difficulty experienced by the NSW Government in building its staffing resources to meet the expected workload and milestones in the Heads of Agreement. In advice to Environment in February 2014, the NOW indicated that the required staffing resources to plan and deliver its project commitments were yet to be fully established. Departmental oversight to effectively manage progress was also adversely affected by a 12 month delay to the approval of the project plan by Environment’s Climate Change and Water Board. As a result, the Board was not well placed to provide direction during the early implementation phase of the project.17

22. In August 2014, Environment elevated the overall risk rating for the project to Tier 1 (the highest risk category). Senior government officials from Environment and the NSW Government are now meeting more regularly with the aim of getting the project ‘back on track’. To realise the expected benefits from the project, including value for money from the acquisition of the land and water entitlements, close cooperation will be required between Environment and the NSW Office of Water (NOW)—particularly in relation to managing the higher residual risks that remain. These include potential delays to the completion of the Water Infrastructure Management and Operation Plan and the land management plan for the site.

23. The difficulties experienced in the early implementation stages of the Nimmie-Caira project (including the delays to the commencement of the ecological survey and the cultural heritage survey) highlight the importance of clearly articulating project management arrangements in the design phase of inter-governmental projects supporting Water Management Partnership Agreements, particularly those involving significant risk exposure and complexity, and including agreed arrangements in project schedules.

24. The ANAO has made two recommendations designed to improve engagement with stakeholders for the remainder of the Nimmie-Caira project and to strengthen project management arrangements in future intergovernmental projects of this nature.

Key findings by chapter

Project Assessment (Chapter 2)

25. The business case prepared by the NSW Government for the

Nimmie-Caira project formed part of an agreed COAG process designed to ‘bridge the gap’ in terms of water diversions in the Murray−Darling Basin. The business case outlined the scope of the project, the significant project elements and the overall benefits from the proposal.18

26. Commonwealth water purchases have generally focused on water entitlements that are held separately from land. NSW undertook a separation of the Nimmie-Caira entitlement in 2012, through the promulgation of the Water Sharing Plan for the Murrumbidgee Regulated River Water Source19, which was initiated prior to the lodgement of the Nimmie-Caira business case in July 2012. This formed part of a broader process of reform within the Murray−Darling Basin that has been supported by COAG since 1994 and recommitted to under the National Water Initiative in 2004. The conversion of licences for the

Nimmie-Caira site in 2012 was based on the maximum historical level of diversion and in proportion to the area of land owned by each landholder. There was no indication that the conversion of the Nimmie-Caira entitlements was inconsistent with the agreed national water reform agenda.20

27. As for all SPPs, the Australian Government was required to undertake a due diligence assessment in accordance with the three criteria established under the IGA: economic and social; environmental; and value for money. While the assessment of the economic and social criterion by Environment was limited, additional studies that had been completed at the time indicated that the net social and economic impacts of the Nimmie-Caira project would most likely be positive in the longer term. However, the extent of any impact will not be known until the options for site management are agreed and finalised in the land management plan, which is scheduled for completion in mid-2015.

28. In assessing the environmental criteria, Environment identified the site as supporting significant rookery and breeding sites for birds protected under international migratory bird agreements. The Lower Murrumbidgee area (Lowbidgee) was also registered in the directory of important wetlands for Australia and was recognised in the Basin Plan as being a key environmental asset. The site was also recognised as having cultural significance for local Indigenous communities.

29. A key consideration in Environment’s assessment of the value for money of the proposed project was the reliability of the water allocated against the entitlements over time. This assessment was particularly important as the proposal involved supplementary water entitlements rather than general or high security water. Environment’s assessment was based on the LTAAY to be derived from the supplementary entitlement as this was considered to provide greater certainty as to the reliability of water allocated against the entitlements. Historically, there has often been a significant variation between entitlement and actual allocation for water users, particularly in NSW. While the LTAAY from the 381 GL to be obtained under the project equated to 173 GL, only 133 GL was assessed by Environment as counting towards ‘bridging the gap’ targets as it considered that 40 GL was already committed to pre-existing environmental watering purposes. This assessment has been contested by the NSW Government and is subject to further consideration in 2016.

30. Environment also tested the assumptions and claims in the business case to establish the fair market value of the proposed acquisition. The assessment of fair market value was challenging because of limited market data on land and water transactions in the Lowbidgee and the lack of any alternative sites or projects of an equivalent scale. To inform its assessment, the department sought the expertise of two independent valuers with their valuations then being assessed by the then Australian Valuation Office.

31. The department’s assessment indicated a premium of $16.9 million (comprising a 10 per cent premium that had been considered acceptable by the Australian Government for large water acquisitions plus an additional premium) over and above the estimate of fair market value. This premium was justified by Environment on the basis of the scale of the purchase against the targets in the Basin Plan, the ability to re-credit water once it was returned to the river and the potential to provide better environmental watering capability for assets in the Murrumbidgee and Murray Rivers. Obtaining an independent opinion on the merits of the additional premium over and above the assessed fair value for the land and water entitlements would have provided greater assurance to the department and the Minister. While acknowledging the premium paid above fair market value, the overall project proposal provided significantly lower cost than buying water in the open market from upstream irrigators, which was estimated to cost an additional $53.6 million. In addition, the acquisition of Nimmie-Caira water entitlements was achieved at less than a quarter of the average cost of other funded ‘bridging the gap’ projects.

Project Advice and Approval (Chapter 3)

32. In the broader water recovery policy context, the Nimmie-Caira project proposal coincided with the then Government’s focus on achieving an agreement among the Basin states to the Murray–Darling Basin plan. A precondition for the NSW Government to commit to the Basin Plan was an agreement to fund the Nimmie-Caira project. While the Minister was made aware of the pre-condition, it was not explicitly referenced in the advice from the department regarding approval.

33. Environment provided a number of briefings to the Minister highlighting the emerging issues and risks that would need to be managed through conditions to the HoA if the project was to be approved. In particular, the briefings emphasised the importance of water shepherding21 arrangements, the re-crediting of return flows to the Lowbidgee system for utilisation downstream and the long term management plan that covered land use and management in perpetuity to protect key environmental assets.

34. The final briefing in June 2013 provided the Minister with the basis for making a decision on the project. The brief included proposed conditions of funding based on the due diligence report22, with a recommendation of funding up to $180.1 million (with $120 million being for the purchase by the NSW Government of the Nimmie-Caira land and water assets from the 11 landowners as a single transaction). As part of its briefing to the Minister, the department enclosed both a cost benefit framework and a risk assessment for the project.

35. The cost benefit framework appropriately addressed the costs and benefits of the proposal for the purchase price of land and water assets. However, the analysis did not include coverage of the costs and benefits of the remaining $60.1 million relating to the offsets, project planning and management23 and infrastructure reconfiguration. While the allowed contingency of $9.9 million provided some capacity to absorb any cost escalations, it would have been prudent to have advised the Minister more fully of the risks of purchasing the site without a comprehensive register of assets.

36. The department’s risk assessment, which was aligned with the findings of the due diligence report, had a strong emphasis on managing project delays—two of the nine risks specifically focussed on possible delays relating to critical implementation steps. The measures proposed to reduce the risks were specifically highlighted for the Minister’s consideration. Nevertheless, seven of the nine residual risks (following treatment) remained high (one) or medium (six). The Minister approved up to $180.1 million in funding for the

Nimmie-Caira project on 24 June 2013 subject to the 31 conditions of funding determined by the department during the due diligence process.

Project Establishment and Implementation (Chapter 4)

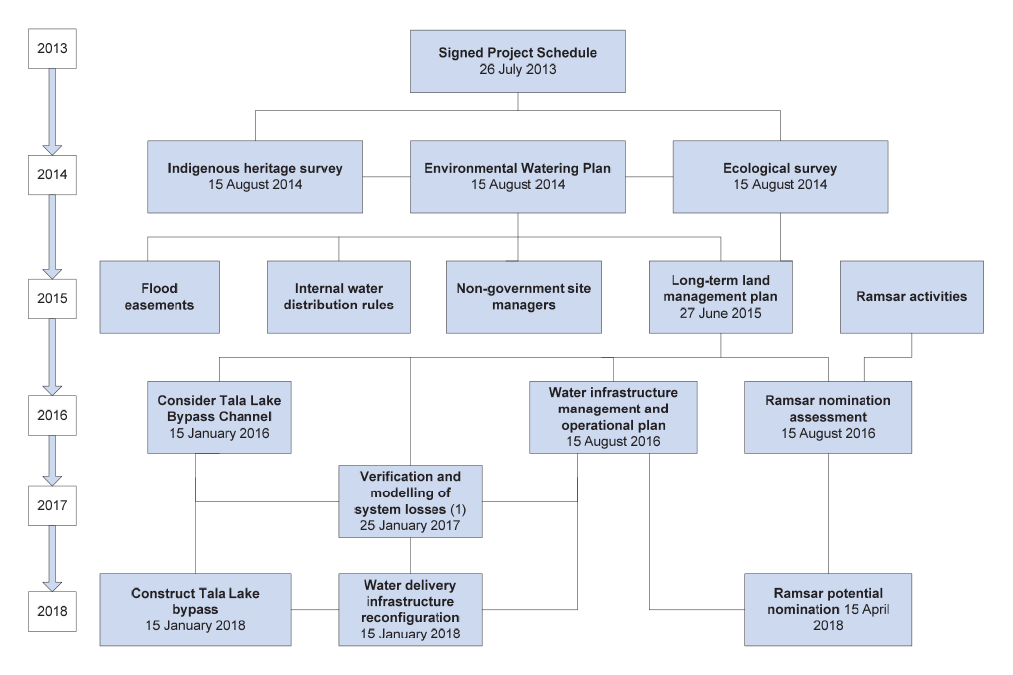

37. Since the approval of the Nimmie-Caira project and the endorsement of the HoA, a number of important implementation actions have been undertaken. The NSW government purchased both the land and water entitlements from the private owners and has been responsible for the development and maintenance of the infrastructure and ongoing management to ensure that environmental flows are being delivered as agreed. Project governance arrangements have been established, defining the roles and responsibilities, timeframes, and the management of risks. In addition, the transfer of water access entitlements to the Australian Government was completed in June 2014.

38. Although progress has been made on implementing some aspects of the project, communication about project developments with stakeholders, including the local community, has been limited in relation to the delivery of the project. Sound stakeholder engagement will help to manage expectations, inform the community of the project’s progress, and enable greater community input. This will be particularly important as key project milestones and actions anticipated in 2015, such as the ecological and cultural heritage surveys and land management plan, will have a high level of community interest and impact. The development of a communication and engagement strategy will better place both governments to more effectively engage with stakeholders and communicate project developments.

39. To date, the progress of the project overall has been affected by ongoing delays. It took some eight months after the Heads of Agreement was endorsed by Commonwealth and State Ministers, for the NOW to consider that it was in a position to properly plan and deliver on its commitments. Early project milestones were not delivered as stipulated in the project schedule and key milestones are overdue. In approving its project plan in August 2014, Environment elevated the project from a Tier 2 to a Tier 1 risk category (the highest risk category) signalling its uncertainty as to whether NSW would meet its obligations based on progress at that point. Environment’s Executive was advised that the project had been ‘significantly delayed with little or no progress made against agreed milestones’ and that, if it was not rectified, the consequence would be that ‘the project will not achieve agreed long term outcomes’. The level of project oversight was, however, hindered by the delayed endorsement of the Nimmie-Caira project plan—some twelve months after the project was approved.

40. Delays in delivering the project are having a cumulative impact that is affecting the sequencing of project elements and is putting at risk the delivery of the project within the agreed timeframe.24 The full benefits of the project, including from environmental water use, will only be realised by implementing the water delivery infrastructure changes and the long-term land and water management arrangements. If these are not completed, there is a significant risk that the project will not achieve established objectives. As such, ongoing senior management collaboration and oversight by the Australian and NSW governments will be necessary to successfully deliver the project.

41. Given the specific provision of administrative funding ($5 million) to NSW for project management capability, there was scope for Environment to have more clearly articulated its expectations in relation to the management arrangements for a project of this complexity. 25 In particular, the linking of administrative funding to the achievement of project management milestones (such as the early assignment of sufficient staff resources) in the project schedule would have helped to encourage timely performance and helped to mitigate some of the risks to the achievement of project objectives. Environment should consider such approaches for any future projects where significant risks to the achievement of program objectives arise from delayed implementation.

Summary of entity response

42. Environment’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the full response provided at Appendix 1.

The Department welcomes the report’s overall findings regarding the effectiveness of the arrangements established by the Department for the funding and management of the Nimmie-Caira project. It is pleasing to note the report considers the project the most cost effective water recovery project administered by the Department. The Department agrees with both audit recommendations and considers that overall the report provides a balanced assessment of the implementation of the Nimmie-Caira project.

The Department notes the Audit Office’s assessment that there would have been merit in obtaining additional independent advice on the value of the premium paid over and above estimates of fair market value of the land and water entitlements for agricultural use. While the Department acknowledges the importance of independent assessment of public expenditure, in this instance the Department judged that further independent advice was not required given the large environmental and administrative benefits associated with the purchase and the avoided higher cost of acquiring the water from alternative sources.

43. The NSW Office of Water’s response to an extract of the proposed report is also provided at Appendix 1.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 4.36 |

To improve communication and engagement with stakeholders, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.66 |

To support the effective delivery of any State Priority Projects delivered in support of Water Management Partnership Agreements, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment, on a risk basis:

Environment’s response: Agreed |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides background information and context for the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project and its implementation by the Department of the Environment. It also outlines the audit approach.

The Murray–Darling Basin

1.1 The Murray–Darling Basin (the Basin) is an area of national environmental, economic and social significance. The Basin comprises Australia’s three longest rivers—the Darling, the Murray and the Murrumbidgee—and nationally and internationally significant wetlands, billabongs and floodplains. The Basin covers one‐seventh of Australia’s land mass and extends across four states—Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia, and the Australian Capital Territory (the Basin states). Thirty‐nine per cent of the national income derived from agricultural production is generated in the Basin, and it is home to over two million people.26

1.2 Throughout much of the twentieth century, infrastructure was constructed and water resources were allocated within the Murray–Darling Basin for irrigation, livestock and domestic supply that disrupted the natural flows of the river system. Around 40 per cent of the Basin’s natural river flow is diverted for human use, including for irrigated agriculture, in an average non-drought year. It is now recognised that irrigation infrastructure and an

over–allocation of water for consumptive use are having unintended environmental consequences. Over time reduced flows have caused a range of significant environmental problems, including:

- increased salinity;

- increased algal blooms;

- diminished native fish and bird populations; and

- poor wetland health.27

Water reform

1.3 Over a number of years there have been significant reforms aimed at improving the management of water resources and addressing the imbalance between consumptive and environmental water use in the Basin. Major reforms have included the:

- National Water Initiative (NWI)—Australia’s blueprint for water reform. As part of this initiative, governments across Australia have agreed on actions to achieve a more cohesive national approach to the manner in which water resources are managed in Australia, including, measuring, pricing and trading water. The NWI was signed at the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) meeting on 25 June 2004;

- commencement of the Water Act 2007 on 3 March 2008, which established the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH) and the Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA);

- production, implementation and enforcement of the first Basin‐wide water sharing and management plan (the Basin Plan) by the then Government in November 201228; and

- progressive acquisition of water entitlements by the Commonwealth for use by the CEWH to water environmental assets in the Basin. As at 30 June 2014, the CEWH held 2126 gigalitres (GL), equating to 1454 GL of long term average yield.29 These entitlements were valued by the Department of the Environment at around $2 billion.30

1.4 The Australian Government’s portfolio of water entitlements is intended to meet environmental needs31, with diversions and extractions from the Murray–Darling Basin to be reduced to sustainable levels by 2019 under the Basin plan. To implement the required level of reductions in diversions and extractions, the Government has committed to ‘bridge the gap’ by securing water entitlements for environmental use. The target for surface water recovery under the Basin Plan, or the volume of the ‘gap’, is 2750 GL. However, there is flexibility built into the Basin Plan to account for actions that enable environmental outcomes to be achieved with less environmental water or without economic detriment. This is called the sustainable diversion limit (SDL)32 adjustment mechanism, which will be triggered by 2016, with works to be completed by 2024.33 The Basin Plan and the SDL are designed to operate in conjunction with the inter-governmental agreement (IGA) on water reform that preceded these initiatives.

Inter-governmental agreement

1.5 On 3 July 2008, the Australian Government and the Basin states—being the states of New South Wales (NSW), Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory—signed an Inter-governmental Agreement on Murray–Darling Basin Reform (the IGA). The IGA aimed to increase the productivity and efficiency of Australia’s water use, to service rural and urban communities and to ensure the health of river and groundwater systems. The IGA (part 4) provides for the Basin states and the Australian Government to enter into Water Management Partnership Agreements (WMPAs) to:

give effect to the urgent need to undertake water reforms in the Basin, to deliver a sustainable cap on surface water and groundwater diversions across the Murray–Darling Basin and to ensure the future of communities, industry and enhanced environmental outcomes.34

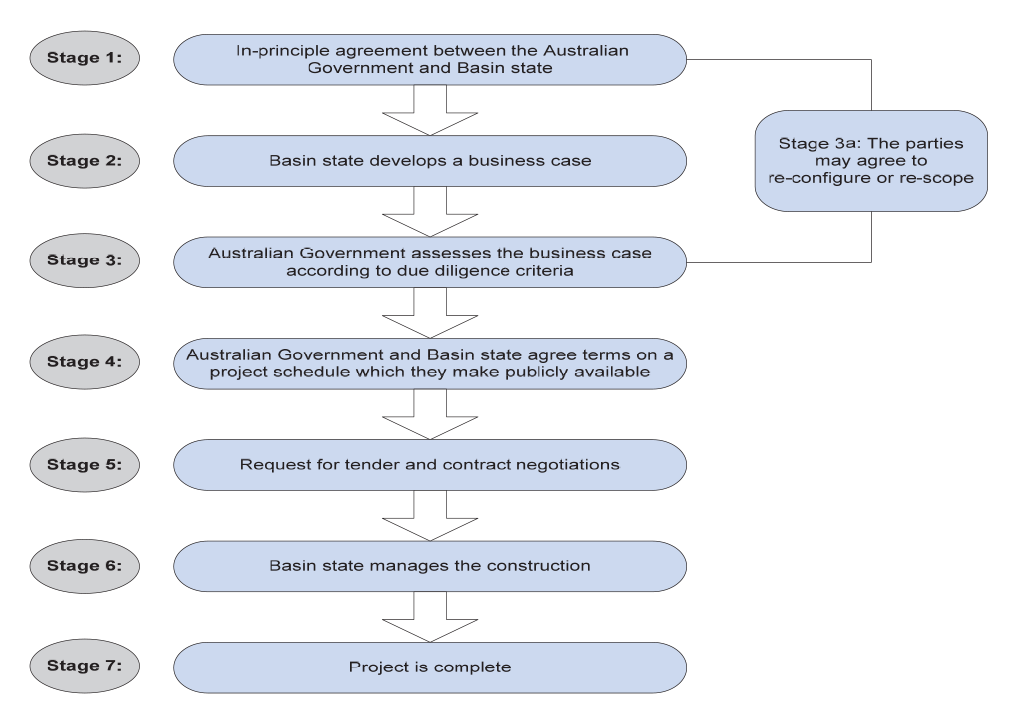

1.6 As part of the IGA, Australian, state and territory governments agreed to develop seventeen priority projects for final approval by the Australian Government. Thirteen of these projects were to be led by Basin states, with the remaining four to be led by the Commonwealth. These State Priority Projects (SPPs) were to deliver substantial and lasting returns of water to the environment, secure the long term future for irrigation communities, and deliver value for money outcomes. Initially, the Australian Government was expected to provide total funding for the projects put forward by Basin states, however, a 10 per cent co-contribution was subsequently required from the states by the Australian Government. The agreed project development process for SPPs is outlined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Indicative SPP development process

Source: COAG Reform Council, available from <http://www.environment.gov.au/resource/water-`management -partnership-agreement-commonwealth-australia-and-state-new-south-wales> [accessed 1 August 2014] p. 36.

Note: The Australian Government provides funding for the business case, as well as for project implementation.

Funding arrangements

1.7 The $5.8 billion Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program (SRWUIP), which is the largest component of the Water for the Future initiative, includes funding for water purchasing, irrigation modernisation, desalination, recycling and storm water capture. The funding for SPPs (both Australian Government-led and state-led) is sourced from SRWUIP.35 To date, SPPs have been funded in each of the Basin states with project funding ranging from $7 million to $953 million.

1.8 The largest acquisition by the Australian Government of water entitlements under an SPP funded by SRWUIP was the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project (Nimmie-Caira project).

Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project

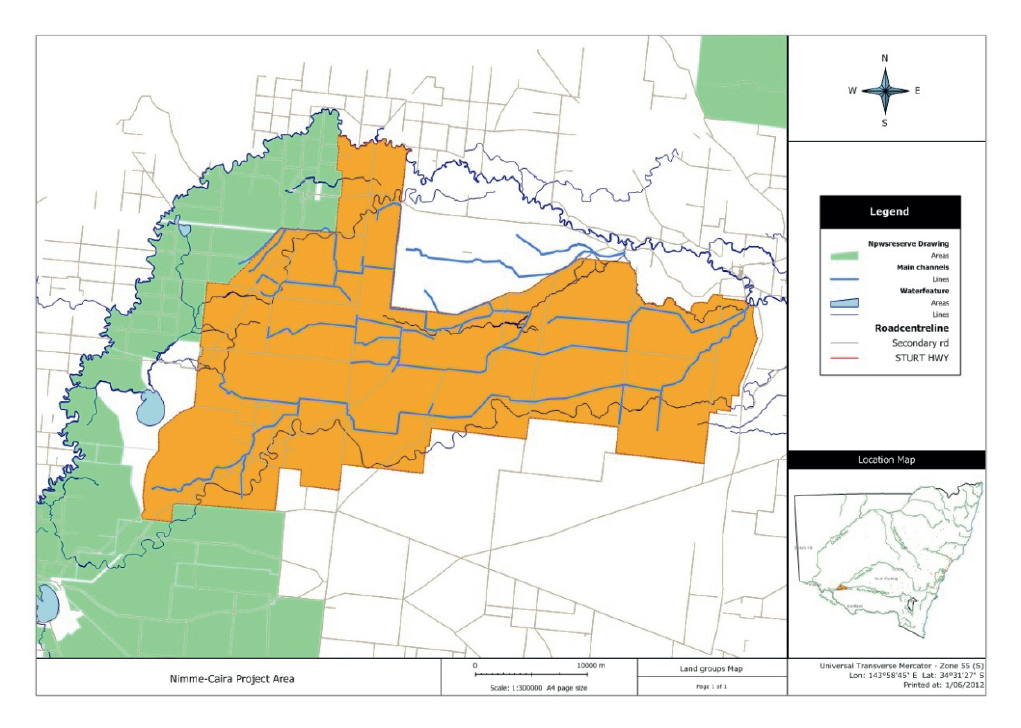

1.9 In July 2012, the NSW Government submitted a business case to the Australian Government (represented by the Department of the Environment) for the Nimmie-Caira project.36 The business case identified around 32 000 hectares of water-dependent vegetation on the Nimmie-Caira site, including red gum and black box communities and sensitive wetlands. The business case also identified the potential to restore cleared land and flood ways to re-connect and re-integrate areas of water-dependent vegetation. The site had extensive irrigation infrastructure that could, with some modification, be utilised for watering high priority environmental sites within the local district, as well as downstream. It was proposed that 381 GL of supplementary water entitlement, which equated to 173 GL of LTAAY, would be transferred to the Australian Government. The Heads of Agreement (HoA) enabled the NSW Government to own the land until long-term land management arrangements were settled and a non-government entity was selected to manage the site. A map of the Nimmie-Caira site is provided in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Nimmie-Caira project site

Source: New South Wales Office of Water.

Note: The orange area defines the Nimmie-Caira project site. The green area defines the adjoining Yanga National Park.

Project assessment and approval

1.10 In March 2013, the Department of the Environment (Environment) completed its due diligence37 assessment of the project, as required under Schedule E of the IGA. The requirements established under this schedule included the investigation of the economic and social, environmental, value for money and water reform aspects of any submitted project, prior to consideration by the Minister for the Environment.

1.11 On the basis of the department’s due diligence assessment, the then Australian Government announced its agreement in June 2013 to fund the Nimmie–Caira project. The HoA, established specifically for the

Nimmie–Caira project, was signed in June 2013. Under the agreement, the Australian Government agreed to provide $180 million to the NSW Government to purchase the land and water entitlements from 11 property owners in the Nimmie-Caira area, and for the NSW Government to undertake extensive infrastructure works and develop long term land management arrangements on the site. The HoA also enabled the water entitlements, previously used for flood irrigation, to be transferred to the Commonwealth for environmental use, making a contribution towards ‘bridging the gap’ to the SDL under the Basin Plan. The Australian Government’s funding was subject to conditions set out in the final due diligence report and subsequently incorporated into a HoA.

Administrative arrangements

1.12 The HoA defines the outcomes, timeframes, and responsibilities for implementing the project and oversight arrangements. Environment is responsible for the oversight and funding of the project, with Executive oversight provided through the Climate Change and Water Group Project Board, Chaired by a departmental Deputy Secretary. The New South Wales Office of Water (NOW) is responsible for day-to-day project delivery. The implementation of the project is informed by the Project Control Group (PCG) and a Project Advisory Committee (PAC). The PCG comprises Environment and NSW Government representatives38, and is the primary intergovernmental forum for managing the implementation in line with the agreed milestones and outcomes. The PAC involves local community and stakeholder representation and was established to advise the PCG on activities required to meet the project objectives.

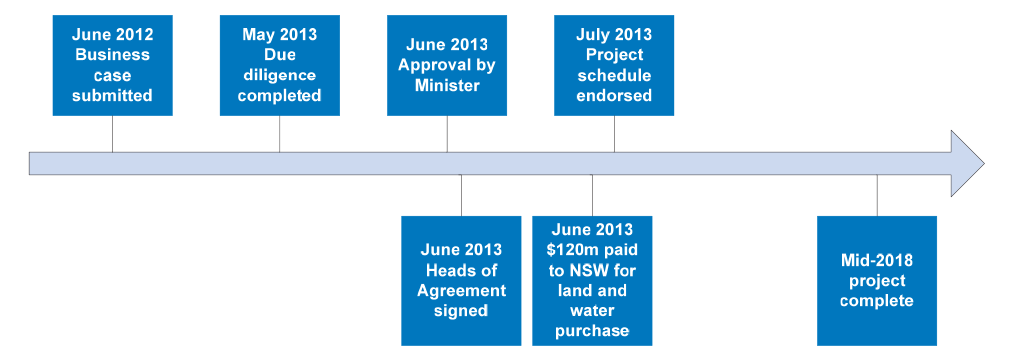

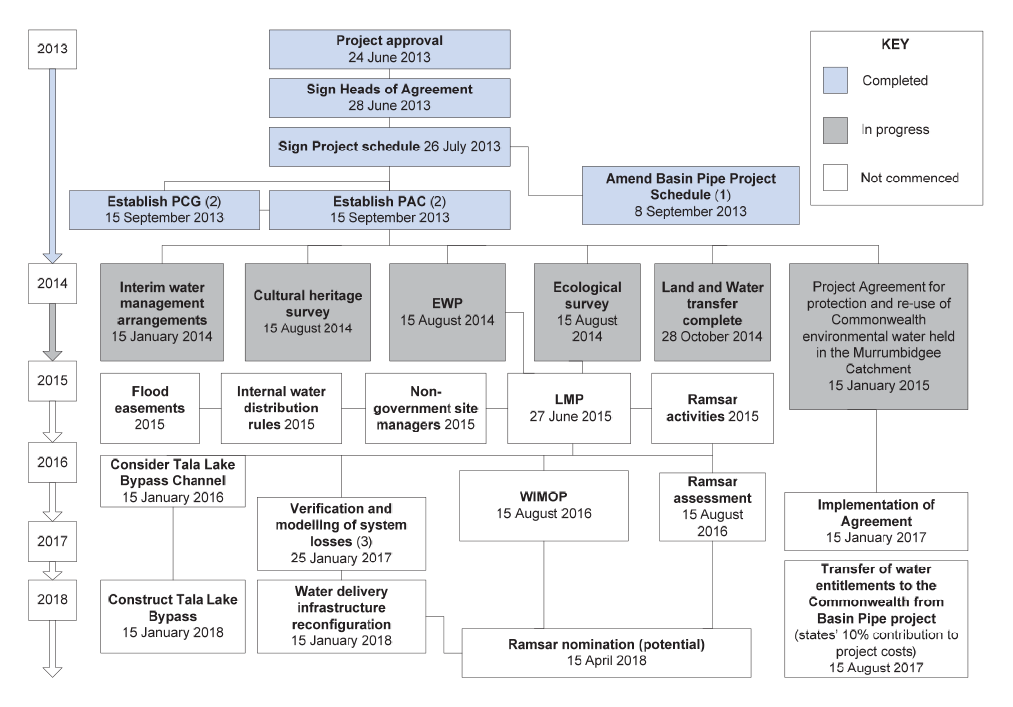

1.13 Progress on the Nimmie-Caira project is subject to the NSW Government achieving the milestones established in the HoA and the project schedule. As at December 2014, $120 million has been paid to NSW for the purchase price of land and water entitlements. An additional $4.5 million has been paid following the completion of three project milestones. A timeline of the key milestones and events for the Nimmie-Caira project is set out in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Timeline and key milestones (as at December 2014)

Source: ANAO analysis of Environment information.

Note: The project schedule specified four purchase milestones and twelve operational milestones through to the completion of the project in mid-2018.

Scrutiny of State Priority Projects

1.14 The Nimmie-Caira project was approved after the majority of other SPPs, which had been agreed and were being implemented from 2008–09. In October 2010, the COAG Reform Council (the Council) reported that progress across the SPPs that had been funded at that time had not been in line with the expectations of governments. The Council expected that:

after two and a half years that the Commonwealth and relevant Basin States would have at least formally agreed the terms of the projects, and to have published project schedules as required by the partnership agreements. However, this was only the case for four of the thirteen projects.39 While a handful of projects demonstrated progress through relatively small sub-projects, overall the projects were still in the planning stages.

1.15 The Council noted that jurisdictions agreed to carry out their responsibilities in a ‘timely manner’, and considered—in most part—that this had not occurred.40

Previous audit coverage

1.16 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has undertaken a number of audits relating to water management reform since the National Plan for Water Security was announced in 2007, with audits including:

- Restoring the Balance (Audit Report No.27 2010–11): The report noted that the purchase and use of water entitlements by the Australian Government through the Restoring the Balance in the Murray−Darling Basin (Restoring the Balance) Program advanced the program’s objectives of reducing consumptive water use, providing water for the environment and easing the transition to the then proposed Basin Plan. Of particular relevance to the current audit of the Nimmie-Caira project were the audit findings in relation to future purchases of water entitlements, with the report stating that:

... in the future, more explicit consideration should be given to quantifying administrative savings and demonstrating claimed ‘immediate’ environmental benefits to justify paying a price premium above established price benchmarks.

- Administration of the Private Irrigation Infrastructure Operators Program in New South Wales (Audit Report No.38 2011–12): The report concluded that while Environment had implemented the program in NSW and allocated available funding, weaknesses in program governance and in the management of a number of implementation issues had an adverse impact on the overall effectiveness of the program’s administration. In this regard, shortcomings were evident in the department’s design of the program, the assessment of applications and the development of measures to inform an assessment of whether the program was achieving its objectives.

- Commonwealth Environmental Watering Activities (Audit Report No.36 2012–13): The report concluded that the strategies for managing environmental water were generally sound. However, a number of suggestions were made to enhance the approach to administering the environmental watering function. In particular, a strong focus on the establishment of the monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement process would position the department to report on the extent to which its use of environmental water had contributed to protecting and restoring the environmental assets of the Murray–Darling Basin.

- Administration of the Strengthening Basin Communities Program (Audit Report No.17 2013–14): The report concluded that there were significant shortcomings in some key aspects of the program’s implementation that detracted from the effectiveness of Environment’s administration. These included the design of the program guidelines, the subsequent assessment of grant applications, and the management of funding. Of relevance to the current audit of the Nimmie-Caira project, were the findings in relation to the management of funding agreements, with the audit concluding that the department had not established a sound and consistent process to manage the scope of funded projects.

Parliamentary interest and media coverage

1.17 The Nimmie-Caira project has been subject to Parliamentary interest since it was first proposed as an SPP by the NSW State Government. Concerns were initially raised by Senator Heffernan in July 2012. Senator Heffernan called for an urgent inquiry before the proposed water buyback was finalised and commented that the landholders selling their assets did not have a licensed water allocation. Prior to the sale he commented that ‘the buy-back of water was some two and a half times the real commercial value and with the infrastructure costs etc that are in the package, it will be four times the real value’. In his view, this was ‘a serious fraud of the public purse and a classic example of a government not knowing what it’s doing’.41

1.18 In March 2013, the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport completed a report into the Management of the

Murray–Darling Basin. The Committee was particularly concerned about the value for money from the Australian Government acquiring supplementary entitlements because of the ‘low level of reliability of the water’. In relation to the Nimmie-Caira project the Committee commented:

the lack of reliability of flows undermines the value for money that the proposal provides for taxpayers and leads to uncertain environmental outcomes. The Committee is also concerned that there has been limited public transparency about the Nimmie-Caira buyback proposal.

The Committee also has concerns that the proposed purchase of water entitlements as part of the Nimmie-Caira project stems from the creation of a new license entitlement recently granted to the landholders. This combined with the concerns about different types of water entitlements and the $168 million total cost of the proposal, raises further questions about the value for money the proposal represents for Australian taxpayers.42

1.19 In its report, the Committee recommended that the ANAO review the Nimmie-Caira buyback proposal. On 26 March 2013, the Auditor-General advised Senator Heffernan, the Chair of the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport, that an audit would not be undertaken at that time as a due diligence process was being completed by Environment and an audit had the potential to delay the Nimmie-Caira negotiations between the Australian and NSW governments. Once the agreement between the Australian and NSW governments was endorsed in 2013 and the transfer of water entitlements to the Australian Government was finalised in June 2014, an audit was scheduled to commence in the second half of 2014.

Media coverage

1.20 Media interest in the Nimmie-Caira project has reflected much of the debate over water buy-backs and the impact on local communities. Local media articles43 have provided extensive coverage of the project and local tensions over the price of the water entitlements being purchased by the Australian Government. Alternative coverage has focused on the different sides of the debate including the environmental benefits of the project and the support from peak industry groups.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Objective

1.21 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the arrangements established by the Department of the Environment for the funding and management of the Nimmie-Caira System Enhanced Environmental Water Delivery Project.

Criteria

1.22 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- appropriate arrangements to assess the merits of funding the proposed project were implemented; and

- sound arrangements for the management and delivery of the project were established.

Scope

1.23 The audit examined the due diligence processes undertaken by Environment to assess the merits of funding the Nimmie-Caira project, including the basis of value for money established by the department in its advice to the decision-maker (the Minister). The appropriateness of arrangements to manage the funded project, including the extent of progress to date was also examined.

Audit methodology

1.24 The audit team reviewed planning and consultative arrangements, relevant documentation, probity and due diligence processes, as well assessments, advice, guidelines and decisions taken to fund the project. In addition, departmental staff and key stakeholders were interviewed and the governance and performance measurement framework established to guide implementation, monitor progress and inform advice to the Government were examined. The audit team also undertook a visit to the Nimmie-Caira site in September 2014.

1.25 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $421 500.44

Report structure

1.26 The structure of the report is set out in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Chapter Overview |

|

Chapter 2–Project Assessment |

Examines the application for funding through the business case prepared by the NSW State Government and submitted to Environment for the Nimmie-Caira project. It also examines the due diligence process that was conducted by Environment in assessing the project. |

|

Chapter 3−Project Advice and Approval |

Examines the briefings and advice provided to the Minister by Environment in relation to approving Australian Government funding for the Nimmie-Caira project. |

|

Chapter 4–Project Establishment and Implementation |

Examines the implementation of the Nimmie-Caira project from the establishment of the Heads of Agreement and the completion of the project schedule. The oversight and administrative arrangements supporting the project were also examined, along with the performance monitoring and reporting arrangements. |

2. Project Assessment

This chapter examines the application for funding through the business case prepared by the NSW State Government and submitted to Environment for the Nimmie-Caira project. It also examines the due diligence process that was conducted by Environment in assessing the project.

Introduction

2.1 The process for developing, assessing and approving SPPs, such as the Nimmie-Caira project, was agreed between the Australian and state/territory governments as part of the Water Management Partnership Agreements (WMPAs) that were established in 2008. The agreed process emphasised the following three stages:

- State/territory agencies develop and submit a business case for each project;

- Environment assesses the project against due diligence criteria established under Schedule E of the IGA; and

- each project is considered by the Minister for the Environment, with approval of funding subject to the agreed terms included in a project schedule.

2.2 Under such arrangements, Environment is responsible for assessing the business case and conducting the due diligence process to comprehensively appraise the project in terms of establishing the potential benefits and costs involved, identifying the risks and developing appropriate mitigation strategies and determining fair value.

Nimmie-Caira business case

2.3 In July 2012, the NSW Government, through the NOW, submitted the initial business case to the Australian Government for financial support for the Nimmie-Caira project.45 In response to matters raised by Environment during the due diligence assessment, the NOW submitted a revised business case in April 2013.46 In summary, the proposal outlined in the business case requested $185.1 million, of which $120 million related to the acquisition of the Nimmie-Caira land and water entitlements.47 The proposal submitted by the NSW Government indicated that the Nimmie-Caira project would deliver the following:

- the provision of 381 GL of Lowbidgee48 Supplementary Entitlement (the equivalent of 173 GL of LTAAY) to meet the water recovery targets within the Murrumbidgee River under the Basin Plan49;

- a flow of up to 3000 ML/day around the Murrumbidgee river choke at Chaston’s Cutting50 through the modification of existing water infrastructure;

- the potential for further SDL offsets through more efficient watering of environmental assets within the Nimmie-Caira site and other areas of the Lowbidgee using the Nimmie-Caira infrastructure, compared with the volumes identified in the then draft Basin Plan;

- the flexibility of using Nimmie-Caira water to provide flows to the Southern Redbank System and Yanga National Park, the Fiddler’s−Uara Creek System or shepherding the flows downstream to other Basin assets, as well as directing flows to important environmental assets within the Nimmie-Caira site;

- enhanced environmental outcomes within the Nimmie-Caira site through the protection of existing areas of lignum vegetation51, wetlands, bird breeding sites and habitat for endangered frog species, as well as the potential for rehabilitation of currently cleared areas of lignum52;

- the benefits accruing from a large, diverse and actively managed wetland from its position adjoining the existing Yanga National Park;

- a reduction in compensation to land owners for flood damage as a result of overbank environmental flows; and

- offset projects endorsed by affected local councils to reduce any negative impacts on local communities.

2.4 While the business plan outlined a range of positive outcomes from the implementation of the Nimmie-Caira project, it also outlined some adverse outcomes. These outcomes included the loss of rate payments to local councils, loss of agricultural production and an associated loss of local expenditure and jobs. However, these outcomes were to be offset through specific local adjustment projects and, overall, the NSW Government considered that the regional and national benefits of the project would far outweigh any negative impacts.

Proposed project budget

2.5 The proposed budget encompassed the cost of acquisition of land and water entitlements, improvements to the site to facilitate environmental watering, structural adjustment projects to assist local councils with the loss of rateable land and a contribution to the NOW for project management and governance. A summary of the project budget outlined in the proposal is set out in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Summary of Nimmie-Caira project elements

|

Project Component |

Description |

Cost ($m) |

|

Purchase of land and water entitlements |

Purchase of 381 000 shares of Lowbidgee supplementary water entitlements. Purchase of 84 000 hectares (ha) of land across 19 properties with water delivery infrastructure. |

120.00 |

|

Conveyance/legal fees |

Legal services associated with the purchase. |

0.10 |

|

Water delivery infrastructure reconfiguration |

Upgrade of system capacity to deliver up to 3000 ML/day through the modernisation and rationalisation of the delivery system’s operation. |

16.26 |

|

Land transition |

Easements, decommissioning of fence lines, establishment of boundary fences. Water supply pipeline, provision of utilities, environmental water management services. |

25.55 |

|

Water planning and modelling |

Environmental watering plan. Verification and modelling of system losses, system operational plan. |

0.50 |

|

Local community offset projects |

Road upgrades for Waugorah and Loorica Roads to maintain access, Community Development Coordinator for Hay Shire, Community Interpretive Centre in Balranald, National/regional tourism marketing. |

4.55 |

|

Project management and governance |

Project manager, project steering committee, monitoring and reporting. |

1.30 |

|

Contingency |

n/a |

16.83 |

|

Total |

|

185.09 |

Source: NSW business case 2012, p. 22.

Land and water acquisition

2.6 One of the key concerns of the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport related to the creation of new licence entitlements granted to the Nimmie-Caira landholders in advance of the proposed purchase under the project. The committee considered that the granting of the licences, combined with the total cost of the proposal, raised questions about the value for money from the Nimmie-Caira project.

2.7 The Lowbidgee Flood Control District, the area in which the Nimmie-Caira project is located, was constituted on 24 January 1945 under Part 7 of the then Water Act 1912 (NSW).53 A key consideration in approving funding for the Nimmie-Caira project was that the water access entitlements had not yet been separated from land titles. That is, the original proclamation establishing the Lowbidgee Flood Control District was still in place at the time the proposal was submitted to the Australian Government by the NSW Government. Consequently, the water access entitlements could not be traded or held separately from the land.54

2.8 A key water reform initiative agreed by COAG in 1994 and subsequently reinforced by the National Water Initiative (NWI) in 2004 was that all water access entitlements be changed from area based licences to volumetric entitlements separated from the land.55 Since the mid-1980’s, NSW has been converting area-based licences into volumetric entitlements, with an initial focus on regulated river valleys. NSW has reported that, in recent years, unregulated river and groundwater systems have been progressively converted into volumetric entitlements including within the Lowbidgee Flood Control and Irrigation District. The volumes determined for the entitlement reflected the historical nature of the diversions.56 The conversion of the irrigation rights to volumetric entitlements in the Lowbidgee were reflected in the amended water sharing plan and were issued to landowners in proportion to their area of land that historically benefited from the water diversion.57 The basis of the charges levied over the licences was to cover the costs of water management and infrastructure owned by the NSW State Water Corporation.

2.9 The conversion of existing area-based licences to volumetric entitlements in the Nimmie-Caira area formed part of a broader process of reform within the Murray−Darling Basin, with conversions being undertaken across different catchments within the Basin. The conversion of licences in the Nimmie-Caira area in 2012 was based on the maximum historical level of diversion and in proportion to the area of land owned by each landholder. There was no indication that the conversion of the Nimmie-Caira entitlements, which was necessary to facilitate water trading by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder, was inconsistent with national water reforms in the Murray−Darling Basin.

2.10 In undertaking its due diligence assessment of the project, the LTAAY from the purchase was a critical consideration for the Australian Government in its calculation of value for money as it informed an assessment of the reliability of water access over time. This was also necessary as there has often been significant variation between the entitlement and actual allocation for water users in NSW.

Risk assessment in the proposal

2.11 The business case prepared by the NOW included a risk assessment for the Nimmie-Caira project, prepared in accordance with the Australian and New Zealand Standard for risk management 2009.58 The risk categories identified by the NOW included: stakeholders; the environment; commercial; technical; safety; and operational risks. In total, fourteen risks were identified along with associated mitigation measures. After mitigation measures were applied, one risk remained at high59, eight of the risks remained at medium and five were classified as low. The highest residual risks (that is, risk after mitigation measures were applied) were:

- stakeholders (ensuring the participation of all landowners in the sale process and the acceptance of the project by the local community);

- operational matters (such as timely amendments to the water sharing plan and approval for required works on creeks to allow the efficient flow of environmental water); and

- the environment (in particular the potential for increased carp breeding60 through increased water flows in the Nimmie-Caira).

Due diligence assessment

2.12 Given the high value of the project and its potential contribution to achieving Australian Government water reform policy objectives, it was critical for the department to examine and test the fundamental elements of the business case to provide an assurance to the Minister and the Government that the project would achieve the stated expectations outlined in the business case. The completion of a due diligence assessment against established criteria was also a requirement of the IGA.

2.13 In addition to the project level risk assessment by the NSW Government provided in the business case, Environment conducted its own strategic risk assessment in line with departmental risk management guidelines. This assessment was prepared to assist the department to identify and manage those risks that could impact on the ability of the Australian Government to achieve its investment objectives for the project. The assessment also assisted the department to better understand aspects of the business case and address a number of concerns. In particular, the department considered that more information was required on the value of water entitlements and operational considerations, such as the movement of water to important environmental assets in the local district and downstream of the Nimmie-Caira site.

2.14 The risk assessment provided Environment with a reasonable basis for managing the range of risks that were intrinsic to major projects funded through inter-governmental arrangements. It also provided the department with a framework within which to consider the application of the due diligence criteria agreed by COAG, which focused on the following three primary criteria:

- economic and social;

- environmental (such as through water shepherding arrangements and re-crediting return flows)61; and

- value for money.62

Economic and social criteria

2.15 Under schedule E of the IGA, SPPs were expected to:

- secure a long term sustainable future for irrigation communities in the context of climate change and reduced water availability in the future;

- contribute towards regional investment and development, secure regional economies and support the local community; and

- demonstrate long term economic and environmental benefit that can be sustained over a 20 year horizon, preferably supported by an irrigation modernisation plan consistent with the Australian Government’s guidelines for irrigation, modernisation and planning assistance.

2.16 The business case contained high level information on the economic and social impacts of the Nimmie-Caira project, highlighting the loss to local councils of $82 000 per annum in rates, the loss of agricultural production of $8.4 million per annum63, a loss of expenditure in Balranald and Hay of some $1.3 million per annum, as well as a loss of employment in the local area.

2.17 The key anticipated benefits identified in the assessment were:

- contributing significantly to ‘bridging the gap’ to SDL’s under the Basin Plan;

- removing the need to obtain the anticipated volume of water from other users in the Murrumbidgee64; and

- contributing to the Basin Plan and the efficiency of water use for the environment.

2.18 To address the identified economic and social costs associated with the project, the NSW Government proposed local council ‘offset’ projects valued at $4.5 million. These projects included: the upgrading of local roads and infrastructure; an interpretative centre at Balranald and regional tourism marketing; and a regional economic development officer located at Hay. The department accepted the cost estimates and all listed project elements with the exception of one.65 As a consequence, the accepted value of the offsets was reduced to $4 million. The basis on which proposed projects were funded was appropriately documented by Environment.

2.19 The business case included limited coverage of the longer term economic and social costs or benefits of the project in the region. The absence of this information made the assessment process more difficult for Environment. The department noted that ‘the level of economic and social activity from the project will be contingent on the implementation of the long term land management plan for the site’. This plan is not, however, expected to be in place until August 2015.

2.20 While undertaking specific modelling to more comprehensively address the socio-economic criteria would have been costly and, to an extent, pre-empted the long term land management plan, there was the opportunity for the department to have considered other relevant research to inform its assessment. For example, research commissioned by the MDBA in 2011 highlighted that, in relation to the Basin Plan:

At the Basin level, the costs are expected to be relatively small. Models have estimated that the level of total production in the Basin (gross regional product) will be reduced by less than one per cent and that this is expected to be more than offset by broader economic growth over the transition period to 2019−20.66

2.21 The MDBA commissioned a further study in 2012 of the benefits of the Basin Plan for primary producers on floodplains in the Murray−Darling Basin. The resulting report in August 2012 showed that the estimated value of production for floodplain producers in the Lower Balonne, Barwon Darling, Lower Lachlan and Lower Murrumbidgee would increase by 10 per cent. The report suggested that the ‘long-run benefits of the Basin Plan are likely to outweigh the

long–run costs’.67 While studies completed to date indicate that the net social and economic impacts of the Nimmie-Caira project are most likely to be positive in the longer term, the extent of any impact will not be known until the options for site management are agreed and finalised in the land management plan scheduled for completion in 2015.

Environmental criteria

2.22 Schedule E of the IGA indicated that SPPs must deliver substantial and lasting returns of water to the environment to secure real improvements in river health. To receive approval, projects were required to:

- be based on technically valid calculations of net water savings, with projections to take into account the impacts of climate change; and

- be able to deliver water in the form of a secure and transferable water entitlement to the Australian Government. The Australian Government’s share of water savings was expected to be capable of being used for purposes that reflected the Government’s environmental watering priorities.

2.23 The due diligence report prepared by Environment noted that, while the Nimmie-Caira project had significant and well documented environmental values, it did not contain any areas designated under the Ramsar Convention for wetlands of international importance.68 Notwithstanding the absence of Ramsar Convention designated areas, the Nimmie-Caira site was identified by Environment as supporting significant rookery and breeding sites for birds protected under international migratory bird agreements.69 The Lowbidgee was also registered in the Directory of Important Wetlands of Australia by meeting five of the six criteria used to determine nationally important wetlands. In addition, the ecological significance of the Lowbidgee was discussed in the Basin Plan, with the MDBA commenting that:

The Lower Murrumbidgee Floodplain is a key environmental asset within the Basin and is an important site for the determination of the environmental water requirements of the Basin.70

2.24 The report also noted the negative impacts from past land use changes in the Nimmie-Caira district, referencing a NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Report in 2001. The report commented that the change in land use from grazing to irrigated cropping from the 1980s resulted in ‘one of the world’s largest wetland destructions in recent times with the area of wetland reduced by 60 per cent’.71

2.25 In addition to preserving the environmental features of the Nimmie-Caira site, a further benefit from the project was the potential to deliver environmental water to local environmental sites of importance in the local area. The CEWO had historically experienced difficulty in delivering water to important environmental assets in South Yanga and Yanga Nature Reserve.72 The value of providing watering capacity through the Nimmie-Caira project illustrates its potential to address a gap in pre-existing environmental watering capability.

2.26 Further, the due diligence report recognised important cultural values within the Nimmie-Caira site, with numerous observations of Indigenous burial sites, campfire ovens and artefacts across the Lowbidgee floodplain. Local Aboriginal Land Council members that were interviewed by the ANAO highlighted the cultural significance of the site to local Indigenous communities.

2.27 Environment did not, however, give explicit consideration to the impact of climate change despite it being an element of the required COAG environmental criteria. Environment informed the ANAO that the impact of climate change is inherent in the project proposal and the business case information requirements that were used to write and assess the proposal for funding. Nevertheless, while climate change impacts were not separately addressed, the evidence was sufficient for Environment to conclude that the environmental values were significant and appropriately aligned with the Government’s water policies at the time—particularly in relation to the contribution to ‘bridging the gap’ and the environmental objectives of the Basin Plan. Furthermore, these values were enhanced through the potentially significant cultural values of the site for local Indigenous communities.

Value for money criteria

2.28 The value of the land and water within the Nimmie-Caira project proposal—$120 million—represented two thirds of the proposed project cost and was the most material component of the project. Consequently, assessing fair value was critical to any assessment of value for money. In addition, the project costs for site works, community offset projects, project management and contingencies were substantial at $60.1 million.

Value for money of land and water

2.29 The business case prepared by the NSW Government noted that $120 million for the land and water assets was being sought by existing landholders. This asking price was recorded in a legally binding and time-limited joint agreement amongst the 11 landholders, which was to expire on 30 June 2013. The offer was presented on an ‘all or nothing’ basis as a single transaction, with the NSW Government supporting the price to the Australian Government through the business case.

2.30 To determine the fair value of the land and water entitlements, Environment engaged two independent firms in 2012 to conduct a market-based comparison to assess the value of the proposed land and water entitlements. The two valuation reports produced a range of values that reflected variations in methodologies73, as well as the ‘uncertainties given the complexity for cropping and livestock systems and the risks associated with these systems’. The challenges in valuing the land and water assets were noted by both firms in their respective reports, as well as in their comments to the ANAO during the audit. The due diligence report noted that, while both firms provided defensible water valuations, both recognised the uncertainty in the water valuations due to:

- the amended Murrumbidgee Water Sharing Plan (WSP)74 not being finalised at the time of the valuations;

- a lack of information about actual farm production costs and profits;

- uncertainty around the reliability of the Lowbidgee supplementary water entitlement (the reliability was subsequently confirmed by the MDBA in February 2013 as 0.45475); and

- uncertainty about how water is used and when the entitlement is available throughout the year.76

2.31 Environment recognised that it required assurance as to the reliability of Nimmie-Caira’s supplementary water over time. Supplementary water entitlements are of lower value than general or high security water entitlements, as the diversion of water is only allowed during periods of supplementary flow—that is, where flow is greater than that required to meet downstream consumptive needs.77 The uncertainty of supplementary access means that any calculation of value must be considered on the basis of the LTAAY and an appropriate discount rate applied.

2.32 The LTAAY for the Nimmie-Caira site was calculated by NSW and included in the business case at 173 GL per annum from the 381 GL of entitlements available through the proposed purchase.78 Modelling by the MDBA that was undertaken as part of Environment’s due diligence process, indicated that, while these figures were accepted79, only 132.6 GL of LTAAY could be counted as ‘bridging the gap’ because an amount of 40 GL of LTAAY was already being utilised on local environmental assets and benefiting the environment. This matter was strongly contested by the NOW and remains an issue of disagreement between Environment and the NOW. However, the due diligence report noted that ‘it was not a matter that should put Australian Government investment at risk’ as 132.6 GL was regarded as a substantial amount of water to ‘bridge the gap’.80 A planned review of sustainable diversion limits in the Murray−Darling Basin is expected to resolve this issue. The department has informed the ANAO that agreement on this matter is expected by mid-2016.

2.33 Once the LTAAY was calculated, Environment then sought to determine the fair value of the water entitlements to be acquired under the project (on a per ML basis81). The two valuations obtained through the due diligence process were used by the department to initially determine that a price of $130 per ML represented a fair market value. However, the NOW strongly disputed the department’s initial determination, arguing that it was based on flawed assumptions—particularly as it preceded amendments to the Murrumbidgee WSP that could reasonably be expected to have a material impact on any water purchase.82

2.34 Accurately determining assumptions and subsequently fair value for water can be difficult for a number of reasons. The price of water fluctuates with rainfall and available supply in storage dams and weirs, and the water market in some areas, including the Lowbidgee, has not been subject to extensive trading. Environment noted that, from August 2008 to May 2013, there were only 12 trades of Murrumbidgee supplementary water entitlements recorded on the NSW Water Register. These trades ranged in price from $158 per ML to $490 per ML and reflected the changing price because of flood and drought conditions over this period. The department recognised that average trading prices had declined at the time by 20–30 per cent in the southern basin since 2009. However, as outlined earlier, the initial valuations were prepared prior to the completion of the WSP for the Murrumbidgee River.

2.35 To obtain additional assurance, and to respond to concerns from the NOW, Environment engaged the then Australian Valuation Office (AVO) in April 2013 to review the two independent valuation reports and the draft due diligence assessment report in the context of the amended WSP (endorsed in October 2012). The AVO concluded that a price of $140 per ML to $170 per ML represented fair value for the water entitlements. The mid-point of this price range produced a total cost of $59.1 million for the water entitlements.83