Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Fraud Control in Australian Government Agencies

The objective of this audit was to assess key aspects of Australian Government agencies' fraud control arrangements to effectively prevent, detect and respond to fraud, as outlined in the Guidelines. The scope of the audit included 173 agencies subject to the FMA Act or the CAC Act.

Summary

Background

1. Australian Government agencies are responsible for administering significant levels of revenue and expenditure including: collecting taxes; purchasing physical assets; providing assistance via grants and subsidies; and delivering payments and services to Australian citizens. These activities involve contact with a broad range of clients and citizens and, increasingly, involve the extensive use of information and communication technologies. In this environment, the prevention and management of fraud is an important component of public sector governance.

2. Fraud against the Commonwealth includes fraud perpetrated by: an employee against an Australian Government agency or its programs; an agency client or external individual against such an agency or its programs; or by a contractor or service provider against an agency or its programs. Behaviours that may be defined as fraud include: theft, providing false and misleading information to the Commonwealth, failing to provide information when there is an obligation to do so, bribery, and corruption or abuse of office. The benefit obtained may be tangible or intangible.1

3. According to the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) fraud is estimated to have cost the Australian community $8.5 billion in 2005.2 The total value of fraud reported in KPMG's 2008 survey of a broad cross-section of public and private sector organisations in Australia and New Zealand was $301.1 million, with an average value for each organisation of $1.5 million.3

4. However, because varying definitions of fraud are used across Australian Government agencies, this data should be used with care. In essence, the measurement of the actual level of fraud is difficult, if not impossible. As well, the nature of fraud is changing as agencies adopt new approaches to deliver government services and make greater use of e-commerce, including the Internet.

5. Fraud is an ongoing risk to the Commonwealth, and the increasing focus on responsive and flexible programs to meet community expectations can expose the Commonwealth to new areas of fraudulent activity that need to be managed. For instance, desired aspects of a policy or program, such as flexibility in service delivery, affect the inherent integrity of the program. These risks, including the proposed method of delivery, reinforce the imperative for agencies to consider program integrity and fraud control measures during the program design phase.

Governance structures and effective fraud control

6. Fundamental to sound fraud management is an overall governance structure that appropriately reflects the operating environment of an agency. In broad terms, governance refers to the processes by which organisations are directed, controlled and held to account. It encompasses authority, accountability, stewardship, leadership, direction and control exercised in the organisation. Establishing an ethical culture is a key element of sound governance and is an important factor in preventing fraud and helping to detect it once it occurs. An effective agency control structure, which includes fraud control, will assist an agency to: promote ethical and professional business practices; improve accountability; and contribute to quality outcomes.

Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines

7. To combat fraud, the Australian Government first released its fraud control policy in 1987. As a result of a review undertaken in 1999, the then Minister for Justice and Customs issued new Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines) in May 2002 under Regulation 19 of the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997.

8. The Guidelines apply to:

- all agencies covered by the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act); and

- bodies covered by the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) that receive at least 50 per cent of funding for their operating costs from the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency.4

9. The Guidelines clearly define the Government's requirement that all FMA Act agencies, and relevant CAC Act bodies, put in place practices and procedures for effective fraud control.5

The role of central agencies

10. The Attorney-General's Department (AGD) is responsible for providing high-level policy advice to the Government about fraud control arrangements within the Commonwealth. This includes developing and reviewing general policies of Government with respect to fraud control, currently embodied in the Guidelines, and advising Commonwealth agencies about the content and application of those policies. The AGD advised the ANAO that work was underway to review the current fraud control policy and subsequently revise the Guidelines.

11. Under the Guidelines, the AIC is responsible for conducting an annual fraud survey of Australian Government agencies.6 The Guidelines mandate that FMA Act and relevant CAC Act agencies are required to collect information on fraud and provide it to the AIC on an annual basis. The AIC is also responsible for producing a report each year on fraud against the Commonwealth, and fraud control arrangements within Australian Government agencies. This report is known as the Annual report to government: Fraud against the Commonwealth, and, as mandated by the Guidelines, is to be provided to the Minister for Home Affairs.7

Previous audit coverage

12. In 2002, the ANAO conducted a survey of fraud control arrangements in Australian Government agencies to establish the extent to which the then new Guidelines had been incorporated into agency fraud control arrangements. Based on the 2002 survey, the ANAO tabled an audit on fraud control arrangements in Australian Government agencies.8 This audit concluded that most agencies did not fully comply with the Guidelines. Particular issues identified were in the areas of: defining and measuring fraud; performing risk assessments; fraud control planning; and fraud control operations and reporting.

Audit approach

Objective and scope

13. The objective of this audit was to assess key aspects of Australian Government agencies' fraud control arrangements to effectively prevent, detect and respond to fraud, as outlined in the Guidelines. The scope of the audit included 173 agencies subject to the FMA Act or the CAC Act.

14. Reported progress in fraud control arrangements made by agencies since the ANAO's 2002 fraud control survey was also tracked. In addition, the ANAO examined how the AGD and the AIC fulfilled their roles as assigned in the Guidelines.

Methodology

15. The audit methodology involved a survey supported by targeted assurance. The ANAO requested 173 FMA and CAC Act agencies to complete the fraud control survey. Responses were received from 160 agencies, representing a response rate of 92 per cent.

16. Agencies were required to provide supporting evidence to substantiate claims made in the survey. For ten per cent of the responses, the ANAO assessed the claims made in the survey against the supporting documentation that the agencies had provided. This provided a level of assurance as to the quality of the survey responses.

17. The ANAO also supplemented its high-level analysis of documents submitted by agencies with targeted assurance work. This involved a small number of agencies and focussed on how they implemented key aspects of their fraud control plans, including the treatment and monitoring of current and emerging fraud risks identified by the relevant agency.9

18. In conducting this audit, the ANAO was mindful of the effort, in terms of time and cost, required for agencies to collate responses to surveys. For this reason, the ANAO obtained access to relevant data held by the AIC and did not request agencies to provide certain fraud information already provided to the AIC.

Conclusion

19. The prevention, detection and management of fraud are matters of ongoing importance for the public sector. Australian Government agencies administer significant levels of revenue and expenditure and officials engage with a wide range of stakeholders, clients and citizens. Accordingly, agencies need to consider program integrity and fraud control measures as an integral part of program design and operation.

20. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines) define the Government's requirement that all Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) agencies, and relevant Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) bodies, put in place practices and procedures for effective fraud control. The Guidelines emphasise that sound corporate governance for fraud control is assisted by having an overall policy and planning regime to prevent fraud, detect fraud when it occurs, and to deal with new and emerging fraud risks.

21. To gauge the reported level of compliance with the current Guidelines over time, the ANAO has undertaken two cross-agency fraud surveys (in 2002 and 2009) involving FMA Act and CAC Act agencies. Since the ANAO's 2002 survey, the reported level of compliance with the Guidelines has improved, particularly the oversight arrangements put in place by agencies to prevent fraud.

22. Overall, agencies reported that they have: established governance structures and allocated staff with responsibilities for fraud control; a specific policy on fraud control; undertaken a fraud risk assessment in the past two years to underpin fraud control planning; developed a fraud control plan, based on their fraud risk assessment; and provided fraud awareness raising and training for staff. In addition, targeted assurance conducted by the ANAO in a small number of agencies indicated that these agencies had made significant progress in implementing and monitoring the key fraud risk treatment strategies outlined in their fraud control plans.

23. Notwithstanding this indication of improvement, a key area of fraud management requiring greater attention by agencies is the evaluation of specific fraud control strategies.

24. In the ANAO's 2009 fraud survey, 54 per cent of agencies indicated that they had conducted an evaluation into the effectiveness of their fraud prevention and/or detection strategies. Most agencies indicated to the ANAO that the process of reviewing their most recent fraud control plan included an assessment of the effectiveness of the strategies and controls in place. However, only 12 per cent of agencies provided examples of evaluations of specific fraud control strategies, and only one of these evaluations considered the cost-effectiveness of fraud controls implemented.

25. In situations where, for example, an agency has: undergone changes to its structure or function; introduced a new program; changed the means of delivery of an existing program; or observed through the analysis of its fraud performance information that fraud levels have changed (such as an increase in the number of fraud allegations made through ‘tip-off' mechanisms); then it would be beneficial for the agency to evaluate its fraud control strategies to determine if they are still effective.

26. At the broader whole-of-government level, the Attorney-General's Department (AGD) is responsible for administering the Australian Government's fraud control policy, and at the time of the audit, was reviewing the Guidelines. To ensure that revised guidance takes into account the matters being raised by agencies, the following known issues could be considered during the review: the definition of fraud as provided in the Guidelines; the applicability of the Guidelines to CAC Act bodies; and the opportunities available to Australian Government agencies to exchange practical experience on fraud control.

27. The Guidelines mandate that specific Australian Government agencies are required to collect information on fraud and provide it to the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) on an annual basis. The AIC, through its conduct of the annual fraud survey, has identified that ‘the definition of fraud as provided in the Guidelines is more inclusive and general than used in practice by agencies'.

28. The AIC also reported in its Annual report to government 2007–08:

Fraud against the Commonwealth, that not all agencies are classifying fraud incidents in the same way. The use of common definitions for fraud and categories of fraud activities would improve reporting on fraud trends. Of particular interest would be improved time series information with a focus on: has the amount of fraud against the Commonwealth increased or decreased; trends in categories of fraud such as identity fraud; and which controls are proving more effective in the treatment of fraud. The ANAO has made a recommendation that the AGD, as part of its review of the Guidelines, consider approaches that will allow the AIC to collect, analyse and disseminate fraud trend data on a more consistent basis.

29. The Guidelines state that they apply to: all agencies covered by the FMA Act; and bodies covered by the CAC Act that receive at least 50 per cent of funding for their operating costs from the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency. However, the Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) advised that CAC Act bodies are only legally obliged to comply with the Guidelines when they are subject to notification by their responsible Minister, under the CAC Act, that the Guidelines apply to them as a general policy of the Australian Government. Accordingly, the ANAO has made a recommendation that the AGD continue to work with Finance to clarify which CAC Act bodies are subject to the Guidelines.

30. A trend in the ANAO's 2009 survey data was that small agencies (those with less than 249 employees) generally comprised the largest percentage of agencies that indicated they were not meeting the mandatory fraud external reporting requirements and were less likely to have fraud prevention oversight arrangements in place. While exposure to internal and external fraud risks will vary according to agency size and role (for example, policy, procurement, payment, or service delivery), the mandatory requirements as outlined in the Guidelines, should be adopted so that specific fraud risks are addressed. As the potential for fraud increases, fraud control arrangements should reflect the fraud risk profile of an agency or particular program. For these reasons, there is scope for the AGD in its review of the Guidelines to consider the merits of establishing an approach to the provision and exchange of practical fraud control advice to smaller Australian Government agencies in particular.

Key findings by chapter

Defining and measuring fraud (Chapter 2)

31. The Australian Government has an interest in trend information regarding the level and type of fraud being committed against the Commonwealth, at the agency and whole-of-government level. The integrity of such trend information is contingent upon common definitions for fraud. In the ANAO's 2009 fraud survey, 97 per cent of agencies reported that they used the definition of fraud as specified in the Guidelines. This represents an improvement in reported levels since the ANAO's 2002 fraud survey, where only 50 per cent of agencies reported using the definition.

32. While most surveyed agencies indicated that they did not experience difficulties in applying the Guideline's definition of fraud, the AIC, through its conduct of the annual fraud survey, identified that the definition of fraud as provided in the Guidelines is more inclusive and general than used in practice by agencies, and that not all agencies are classifying fraud incidents in the same way. Owing to agencies' differing applications of the definition of fraud, Australian Government agencies are reporting incomplete and inconsistent data on the extent of fraud to the AIC in its Annual Reporting Questionnaire.

33. Australian Government agencies commenced annual reporting on fraud in 1995–96.10 The AIC advised that since this date there has not been an opportunity to produce fraud trend information owing to the poor quality of data reported by agencies, and the inconsistencies present in the use of units of measurement and categories.11 The AIC indicated that a major revision of the reporting requirements would be required in order for sufficient accuracy to be obtained from reporting so that trends could be identified from year-to-year in the future.

Agency roles and responsibilities (Chapter 3)

34. The AGD is responsible for providing high-level policy advice to the Government about fraud control arrangements within the Commonwealth. This includes developing and reviewing the general policies of Government with respect to fraud control, currently embodied in the Guidelines, and advising Commonwealth agencies about the content and application of those policies.

35. The Guidelines outline the Government's requirement that all agencies covered by the FMA Act, and those bodies covered by the CAC Act that receive at least 50 per cent of funding for their operating costs from the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency, comply with the Guidelines.

36. However, relevant CAC Act bodies are only legally obliged to comply with the Guidelines when they are subject to notification by their responsible Minister that the Guidelines apply to them as a general policy of the Australian Government.12 The AGD indicated that it does not maintain a record of those CAC Act bodies directed by Ministers to comply with the Guidelines. As a result, there is a lack of visibility as to which CAC Act bodies have (or have not) received a notification (from their responsible Minister) to apply the Guidelines. Given the review of the Guidelines, the AGD is working with Finance to address the issues surrounding the applicability of the Guidelines to CAC Act bodies.

37. While the overall trend in the ANAO's 2009 survey was a reported improvement in the use of fraud controls, a theme was that smaller agencies (those with fewer than 249 employees) were less likely to have the oversight arrangements in place to prevent fraud and were less likely to meet mandatory fraud external reporting requirements. Recent reports on fraud trends across both the public and private sectors indicate that fraud remains a prevalent and serious problem.13 With the revision of the Guidelines currently in process, there is an opportunity for the AGD to consider the merits of establishing an approach for the provision of fraud control advice and information to Australian Government agencies, particularly to smaller sized agencies. Such an approach would facilitate a better understanding of the type and scale of fraudulent activities occurring across Commonwealth agencies and provide a vehicle for the exchange of information on operational fraud control practices that have proven to be successful over time and/ or in a significant number of cases.

Fraud prevention (Chapter 4)

38. A central objective in fraud control is to minimise the risk of fraud occurring. Ongoing and emerging fraud risks identified by agencies completing the ANAO's 2009 fraud survey included: unauthorised or inappropriate use of information technology; the unauthorised access and release of information; the forgery or falsification of records; identity fraud; and opportunities for fraud arising from the way in which government conducts business such as the outsourcing of service delivery to external service providers, the introduction of new policy initiatives and programs, the introduction of internet-based transactions, and electronic information exchange.

39. The Guidelines state that CEOs are responsible for developing an overall fraud control strategy for the agency, including operational arrangements for dealing with fraud. As part of this strategy, agencies are required to have: established governance structures and allocated staff with responsibility for fraud issues; established a specific policy on fraud; undertaken a fraud risk assessment in the past two years (or as necessitated by changing conditions); and developed a fraud control plan based on the fraud risk assessment. It is also good practice for agencies to have procedures and guidelines that assist employees to deal with fraud matters.

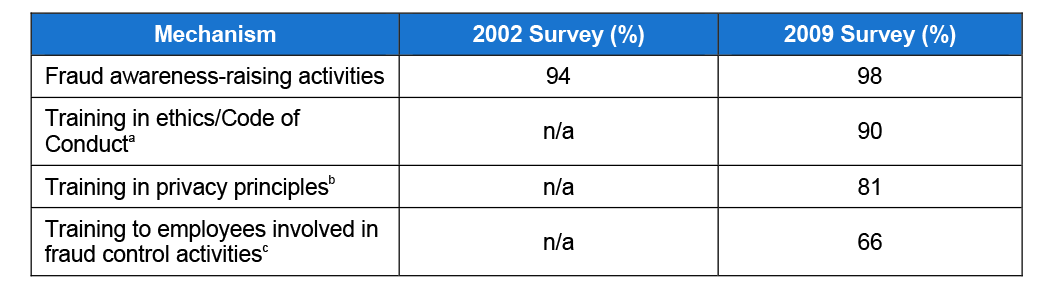

40. Since the ANAO's 2002 survey, agencies' reported compliance with the Guidelines' requirements for fraud prevention has improved. The ANAO's fraud survey results for 2009 and 2002 are compared in Table S.1.

Table S.1: Agencies that answered ‘YES' to having implemented oversight fraud prevention mechanisms

Note a: Not a mandatory requirement of the Guidelines.

41. The Guidelines require agencies to devise (and document in their fraud control plans) fraud risk treatment strategies that will address the fraud risks identified. To ensure the strategies are acted upon, agencies need to allocate responsibility and set timeframes for implementation. The ANAO undertook additional targeted assurance in three agencies: the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service; the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism; and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Overall, these agencies had made significant progress in implementing and monitoring the key fraud risk treatment strategies outlined in their fraud control plans.

42. The Guidelines also state that an agency must review its fraud risk assessment if it has undergone a substantial change in structure or function. A new assessment of fraud risk would, for instance, be required when an agency introduces a new program, undergoes changes to its structure, loses or inherits functions, or changes the means of delivery of an existing program.

43. When considering the features of a new government policy or program, the design characteristics will influence the inherent capacity of the initiative to be delivered with a high level of integrity. Factors that affect the potential for fraudulent activity include the degree of flexibility in the eligibility rules and schedule of services to be provided. The method of delivery of a government policy or program can also affect the risk of fraud. For example, approaches to deliver government services increasingly use third party providers and make greater use of e-commerce, including the Internet. While these arrangements provide for ease of access to government services, they may also increase the Government's exposure to fraud.

Fraud awareness and training (Chapter 5)

44. When managing the risk of fraud within an agency, it is important to create an ethical workplace and support this culture through fraud awareness-raising and training. The Guidelines require that all agency employees and contractors take into account the need to prevent and detect fraud as part of their normal responsibilities. Ensuring that staff are aware of the standards of conduct expected of them, and are alert to the responsibilities they have in relation to fraud prevention and control, is achieved through agencies undertaking fraud awareness-raising initiatives.

45. The Guidelines also encourage the training of all employees in ethics and privacy principles, and promote the specialised training of employees involved in fraud control activities. Results of the ANAO's fraud survey for 2009 and 2002 are compared in Table S.2.

Table S.2: Agencies that answered ‘YES' to having undertaken fraud awareness and training activities

Source: 2009 ANAO Fraud Survey and 2002 ANAO Fraud Survey

Notes a, b, and c: Not a mandatory requirement of the Guidelines.

Notes a,b: Figures represent training provided to selected or all staff.

46. The survey results for 2009 show that agencies have given consideration to general fraud awareness-raising initiatives and training in ethics/Code of Conduct and privacy principles. However, only 66 per cent of agencies reported that they provided specific training to staff directly involved in fraud control activities. For an agency's managers and staff to be able to identify, and thereby, prevent and control fraud requires a high level of awareness of fraud related matters. Training is an effective way of ensuring that managers and staff, particularly those appointed direct responsibility for fraud control, are well equipped to deal with all fraud matters.

47. For those staff directly responsible for investigating fraud, the Guidelines outline mandatory fraud investigation training requirements. In the ANAO's 2009, fraud survey agencies were asked about the qualifications of their fraud investigation staff. Agencies reported that 923 of the 1119 fraud investigators have relevant qualifications, including a Diploma in Government (Investigation), Certificate IV in Government (Investigation) or another relevant qualification as outlined in the Guidelines.

Detection, investigation, and response (Chapter 6)

48. The Guidelines state that:

The Federal Government is determined to ensure that fraud against the Commonwealth is minimised and that, where it does occur, it is rapidly detected, effectively investigated, appropriately prosecuted and that losses are minimised.14

49. The Guidelines indicate that agencies are to implement a fraud control program that covers both prevention and detection. While the Guidelines do not specify the detection mechanisms to be used, it is good practice to implement mechanisms, such as fraud ‘tip-off' lines, to facilitate members of the public to report suspected fraudulent activity by an agency's customers, employees or contractors. Such initiatives are particularly valuable for agencies that deliver services and payments to the community. The Australian Government Services Fraud Tip-Off line is an example of a mechanism that provides members of the public with a place to report allegations of fraud against the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, the Child Support Agency, Centrelink, and Medicare.

50. In the ANAO's 2009 fraud survey, 95 per cent of agencies reported that they had a mechanism in place to deal with fraud allegations made by employees and contractors. Mechanisms to deal with fraud allegations made by members of the public were less common.

51. While for some time, large service delivery agencies have used fraud ‘tip-off' lines, a prominent result from the ANAO's survey was that only 45 per cent of agencies indicated that they had such mechanisms in place to facilitate reports from members of the public of alleged fraud. Mechanisms that allow the public to report fraud are particularly valuable for service delivery and ‘client-facing' agencies. Such mechanisms also provide an important conduit for detecting potential fraud during the roll-out of new programs or where service delivery arrangements have substantially changed.

52. Making formal fraud reporting mechanisms available to members of the public, during the implementation of new or revised programs, can assist agencies to monitor ‘spikes' in fraud allegations (including their characteristics and geographical spread) that serve to provide a useful early warning system about the design of the program and appropriate fraud controls. In cases where detection mechanisms, such as tip-off lines, indicate increased levels of fraud, it will be appropriate to evaluate the effectiveness of the existing fraud control strategies.

53. The Guidelines require that agencies' fraud investigators be appropriately trained, and conduct investigations in line with the Australian Government Investigation Standards (AGIS). In the ANAO's 2009 fraud survey, of those agencies to which the question was relevant, 89 per cent reported having procedures and guidelines in place for the conduct of fraud investigations that were in line with the AGIS.

Performance monitoring, reporting, and evaluation (Chapter 7)

54. Assessing the performance of fraud control activities is an important element of an agency's accountability to key stakeholders, such as the Portfolio Minister, the Attorney-General, clients, the Australian Parliament and the general public. An effective fraud monitoring, reporting and evaluation regime provides assurance that legislative responsibilities are being met as well as assisting agencies to better manage their fraud resources, monitor short and long-term outcomes and report their performance to stakeholders.

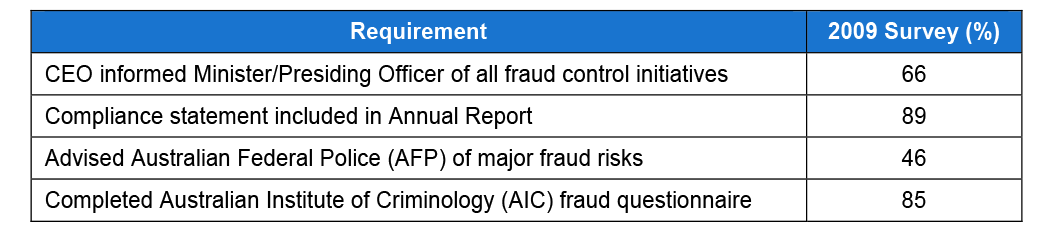

55. The Guidelines outline the responsibilities that CEOs and their agencies have in relation to fraud external reporting. In the ANAO's 2009 fraud survey, agencies indicated whether they had complied with the mandatory fraud external reporting requirements. The results are presented in Table S.3.

Table S.3: Agencies that answered ‘YES' to complying with the Guidelines' external reporting requirements

Source: ANAO 2009 fraud survey.

56. From a whole-of-government perspective, the ANAO's 2009 survey results indicate that a significant number of agencies did not meet the mandatory fraud external reporting requirements. If more agencies reported on their fraud control arrangements and fraud trends, additional information would be available to assist in providing a picture of the effectiveness of the management of fraud across Australian Government agencies.

Summary of agencies' responses

57. The AGD's full response to the audit is at Appendix 1. Its summary response is as follows:

The Attorney-General's Department welcomes the ANAO's performance audit of Fraud Control in Australian Government Agencies. AGD accepts the ANAO's recommendations, which reflect work which currently underway. The Government remains committed to protecting Commonwealth revenue, expenditure and property from any attempt to gain illegal financial or other benefits. The findings of the performance audit will assist Commonwealth agencies in minimizing their fraud risks and strengthening their organizational capacity to detect and respond to fraud.

58. The AIC's response is as follows:

The Australian Institute of Criminology is pleased to have had the opportunity to consult with your office throughout the course of this review and to be invited to offer specific comment in relation to Recommendation number 1. As a general comment, based on Institute research in the area of fraud, the ANAO's second recommendation as it applies to agencies of various type and function across the Commonwealth is appropriate.

As to recommendation No 1 specifically, the Australian Institute of Criminology agrees with this recommendation and notes that although larger agencies are less needy of fraud control advice given their internal expertise in this area, that given the nature of their programs, they are most likely to experience the most costly fraud incidents, particularly from sources external to their agencies.

Footnotes

1 Minister for Justice and Customs, Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines, Attorney-General's Department, 2002.

Australian Institute of Criminology, Counting the Costs of Crime in Australia: a 2005 update, p. 41.

2 KPMG, Fraud Survey 2008, p. 4.

3 Minister for Justice and Customs, Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines, Attorney-General's Department, 2002, para. 1.5.

4 The Department of Finance and Deregulation advised the ANAO that relevant CAC Act bodies are only legally obliged to comply with the Guidelines when they are subject to notification by their responsible Minister that the Guidelines apply to them as a general policy of the Australian Government.

5 The AIC has the primary role to conduct criminological research. It is a Commonwealth statutory authority within the Attorney-General's portfolio.

7 This report is not publicly released. It is classified ‘in-confidence' and distributed to the heads of Commonwealth agencies.

8 ANAO Audit Report No.14 2003–04, Survey of Fraud Control Arrangements in APS Agencies.

9 The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service; the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism; and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

10 The AGD was responsible for the collection and reporting of fraud data up until 2006–07, when the responsibility was transferred to the AIC.

11 The Australian Institute of Criminology's response to ANAO Issue Papers 4 February 2010.

12 Advice from the Department of Finance and Deregulation.

13 See Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, 2008 Report to the Nation on Occupational Fraud & Abuse, Austin, USA, 2008. KPMG, Fraud Survey 2008, 2009. PricewaterhouseCoopers, Economic Crime: People, Culture and Controls. The 4th biennial Global Economic Crime Survey, 2007.

14 Minister for Justice and Customs, Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines, Attorney-General's Department, 2002, p. iii.