Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Effectiveness of the Governance of the Northern Land Council

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the governance of the Northern Land Council in fulfilling its responsibilities and obligations under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, Native Title Act 1993 and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Northern Land Council (NLC) was established in 1974, to represent the views of Aboriginal people to the Federal Government’s Aboriginal Land Rights Commission inquiry into the recognition of Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory. Some two years later, recommendations in the second report of the Commission were enacted through passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (the Aboriginal Land Rights Act) that, among other things: delivered statutory powers and responsibilities to the NLC to assist Aboriginal people to acquire and manage their traditional land and seas; established the Aboriginals Benefit Account1; and provided for the creation of Land Trusts.2 The NLC is also a native title representative body, pursuant to the Native Title Act 1993 (Native Title Act).

2. In March 2013, the report of an external review of the NLC’s governance framework identified a ‘fundamental breakdown in the governance framework at the NLC’, resulting in serious failings in almost all aspects of the council’s administration. On 27 February 2015, the NLC’s Chief Executive Officer and senior officials appeared before the Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee, following the Australian National Audit Office’s financial statements audits that found weaknesses in the NLC’s financial management and reporting. The committee was highly critical of the NLC’s progress in improving internal management systems.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the governance of the Northern Land Council in fulfilling its responsibilities and obligations under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, Native Title Act 1993 and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted high level criteria that the Northern Land Council’s:

- operations, through the Full Council, Regional Councils and Executive Council are effective in representing the interests of Aboriginal people in the region;

- administrative arrangements and systems—including documents management, human resources management and information and communications technology systems—support the council’s functions and delivery of services; and

- corporate planning and performance reporting are effective and meet legislative requirements.3

Conclusion

4. The Northern Land Council is some two years into a wide-ranging reform agenda covering almost all aspects of the governance and administration of the council. While tangible improvements have been made to date to raise the standard of administration from a very low base, considerable work remains for the council to be administratively effective. Throughout the conduct of this audit, there was a notable energy and commitment from staff and managers to achieve the aims of the reforms over the longer term.

5. The NLC is improving its processes for representing the interests of Aboriginal people in the region, but more remains to be done to demonstrate that these processes are effective. The NLC has yet to implement measures to assess the performance of the Full Council, Regional Councils and Executive Council and of council members, in engaging with NLC constituents and representing their rights and interests. A review and restructure of the Secretariat branch aims to streamline and improve its support for the operation of the council, with a branch plan and performance indicators recently developed.

6. Subsequent to substantial criticisms about failed administrative processes, practices and controls, the NLC has commenced a range of initiatives to better support its functions and the delivery of services. These initiatives have included enhanced financial reporting capability and records management, and the establishment of a competent Audit Committee to oversee reforms across key corporate functions and policies. Some progress has been made in modernising the NLC’s dysfunctional information and communications technology systems, with further improvements subject to available funding. Improvements in service delivery are supported by management and budget information that was not previously available to managers. The NLC could more effectively manage its reform agenda given the extent of the changes underway.

7. The NLC is improving its planning in line with requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, but it is still some way from developing a robust set of qualitative and quantitative performance indicators. The NLC’s planning and performance reporting cycle could be better supported by an update of the funding process administered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, to align it with the Commonwealth Performance Framework. In engaging with the department and government, the lack of a shared understanding of the extent of the use of powers, and the roles and responsibilities of the NLC, the department and the responsible Minister has not supported a strong and productive relationship between the various parties.

Supporting findings

Operation of the Council

8. The NLC is improving its representation processes but has collected insufficient information to demonstrate how effective representation has been in practice. In this regard, the council has commenced initiatives to monitor and assess councillors’ performance, manage complaints and conduct stakeholder surveys that will potentially provide useful information on the effectiveness of its performance in representing the interests of the Aboriginal people in the region. However, the NLC has yet to implement an internal audit function to provide assurance that administrative processes and procedures are being followed. The council has been assessed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet as satisfactorily performing its functions as a native title representative body. The NLC has complied with some requirements under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 for nominating councillors and conducting council meetings and is working towards full compliance.

9. The NLC has reviewed and restructured the Secretariat branch to streamline services to councillors and the Chief Executive Officer. Most recently, the outcome of a workshop held in late March 2017 renamed the branch (to the Executive branch), better defined the responsibilities of each function within the branch, identified branch priorities, and developed a business plan and performance measures to assess the effectiveness of the branch in supporting the operations of the council. There was no business plan and few procedural documents from previous years upon which to base the work of the branch, going forward.

Administration and service delivery

10. The NLC’s administrative arrangements do not yet effectively support the work of the council. Prior to 2015, the management and maintenance of core enabling functions, including information and communications technology systems, human resource management and records management was poor, with serious weaknesses in financial management, fraud control and the management of risk. Commencing in 2015, the council is implementing an extensive reform agenda across all administrative functions, with progress having been achieved in corporate planning and reporting, financial reporting and in internal governance through the operations of an Audit Committee. Other reforms, including in human resource and records management, are well underway with an overhaul of the council’s information and communications technology systems in the early stages.

11. Commencing in 2015, the NLC is also implementing numerous reforms aimed at improving the delivery of services. Some reforms are weighted towards improving the efficiency and standard of services provided to stakeholders, particularly improvements in the administration of royalty payments, while others reflect specific goals set out in the NLC’s Strategic Plan 2016–20. The NLC’s leadership group is developing key result areas and associated performance measures for the services, to be incorporated in the 2017–18 planning and reporting cycle. Prior to the reforms now being implemented there was little by way of planning or coordination of service delivery, and no evidence of measures against which services could be assessed.

12. The NLC is achieving progress in implementing its reform agenda, but the pace and extent of the changes could be better supported by improved monitoring and coordination of the reform activities, and communication with staff.

Planning, performance and engagement

13. The NLC is working towards effective planning and reporting of performance. The NLC’s planning framework consists of a strategic plan, corporate plan and branch business plans. While not fully refined, including to incorporate business plans and performance indicators at branch level, the NLC aims to complete the planning and reporting cycle at all levels of the organisation in 2017–18. The NLC has mostly met planning and reporting requirements in the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and enhanced Commonwealth Reporting Framework (2015), not meeting timeliness requirements to publish the plan. The NLC’s planning, development and reporting of performance could be better supported by an update of the funding process for operational and capital expenditure, so that it aligns with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and Commonwealth Performance Framework.

14. Some 40 years on from the Royal Commission, the NLC remains wary of government intent and of the bureaucracy, with respect to its independence in representing the views of its constituents. The relationship between the department, the responsible Minister and the NLC Executive is complex (given the statutory independence and the advocacy role of Northern Territory Land Councils) but it has not been defined, irrespective of recommendations that it should be. The establishment of biannual strategic forums in 2016, involving representatives from the Australian Government, Northern Territory Government and the Land Councils presents an opportunity to establish a more productive and collaborative relationship with the NLC.

Recommendations

Recommendation No. 1

Paragraph 3.68

To support the administrative and strategic reforms underway, the Northern Land Council:

- develops and maintains an action plan to monitor the progress of reform initiatives and projects; and

- develops a communication strategy to inform staff of the changes.

Northern Land Council’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 2

Paragraph 4.28

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, in consultation with the Northern Land Council, reviews the process for the provision of operational and capital expenditure under s.64(1) of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, to develop a funding framework that:

- supports the council in achieving outcomes linked to its strategic and corporate plans, and is aligned with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act, 2013;

- provides for appropriate guidance on what is required in the council’s funding submissions, transparency as to how bids are assessed, and an explanation as to funding decisions; and

- allows for certainty, where results are achieved, for funding certain activities beyond the current year.

Northern Land Council’s response: Agreed.

Prime Minister and Cabinet’s response: Agreed.

Entity responses

15. The summary response of the Northern Land Council is provided below. The formal responses of the Northern Land Council and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet are at Appendix 1.

Northern Land Council

The Northern Land Council (NLC) welcomes the Australian National Audit Office’s report on the ‘Effectiveness of the governance of the NLC’. Further, we accept the report’s two formal recommendations.

The NLC has willingly co-operated with the audit, and the audit team has dealt with the NLC fairly throughout.

The council is pleased that the ANAO report acknowledges the extensive reforms that are being implemented across the whole organisation. The process of reform began with the arrival of Mr Joe Morrison as Chief Executive Officer in February 2014, and was on foot at the time of the Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee hearing in February 2015, which the audit report refers to at paragraphs 1.18 and 1.19.

The development and implementation of the reforms are still a work in progress, but the NLC feels proud that it is already a much more efficient and accountable organisation, and much better placed to serve its Aboriginal membership and constituents.

The ANAO’s performance audit has been a worthwhile exercise; it has, in fact, proved to have been an aid to the NLC’s reform process. We will continue to monitor the progress of the reform initiatives and the benefits which will flow from them.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Northern Land Council (NLC) and Central Land Council (CLC) were established in 1974, as part of the Federal Government’s Aboriginal Land Rights Commission 1973 (also known as the Woodward Royal Commission) to inquire into the appropriate way to recognise Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory. The function of the Land Councils at that time was to represent the views of Aboriginal people to the commission.

1.2 Some two years later, recommendations in the second report of the commission were enacted through passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (the Aboriginal Land Rights Act) that, among other things: established the NLC and CLC as independent statutory authorities with powers and responsibilities to assist Aboriginal people to acquire and manage their traditional land and seas; provided for the establishment of other Land Councils in the Northern Territory4; established the Aboriginals Benefit Account5; and provided for the creation of Land Trusts.6

1.3 The Aboriginal Land Rights Act also makes provision for Land Councils to administer and distribute payments received on behalf of Traditional Aboriginal Owners for activities undertaken on Aboriginal land under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. Land access and use payments (commonly referred to as royalty payments) are to be distributed in accordance with the Land Councils’ statutory duty under s.35 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

1.4 The NLC and CLC are also Native Title Representative Bodies, pursuant to the Native Title Act 1993 (Native Title Act) that provides for claimants to apply to the Federal Court to have their native title recognised by Australian law. Native title is the recognition (in Australian law) that some Aboriginal people continue to hold rights to their land and waters that come from traditional laws and customs. The NLC is the representative body for Aboriginal people living in the northern region of the Northern Territory (including the Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt), and the CLC represents those within the territory’s central region.

1.5 An overview of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act and the Native Title Act is at Appendix 2. Key legislated functions of a Land Council under section 23 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, and of a native title representative body under section 203B of the Native Title Act are at Appendix 3. In general terms, under both Acts, the NLC is responsible for consulting with and representing the views of Aboriginal people living in the region, and assisting them to acquire and to manage their traditional lands and seas.

1.6 As at February 2017, Aboriginal people held freehold title (under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act) to approximately 50 per cent of the Northern Territory land mass and to 85 per cent of its coastline, and approximately 17 per cent of Northern Territory land and waters was subject to Native Title.7

1.7 The four Land Councils also deliver a range of land and sea management services funded under the Australian Government’s Working for Country program8 (also referred to as the Caring for Country program), and other environmental and or liaison functions for Australian Government and Northern Territory Government departments. Land Councils’ delivery of these services is authorised by the functions specified in s.23(1) of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

1.8 Land Councils are Corporate Commonwealth Entities9 under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The Chairman and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of each Land Council is the Accountable Authority under this Act, with a range of duties, responsibilities and obligations to meet in discharging their responsibilities.10 Land Councils are in the portfolio of the Minister for Indigenous Affairs, within the broader portfolio of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Table 1.1 outlines the core legislative framework for Northern Territory Land Councils.11

Table 1.1: Legislative framework for Northern Territory Land Councils

|

Legislation |

|

|

Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 |

Enabling legislation of the Northern Territory Land Councils. |

|

Native Title Act 1993 |

Provides for responsibilities of native title representative bodies. |

|

Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 |

Requirements of Land Councils as Corporate Commonwealth entities. |

Source: ANAO.

Northern Land Council

1.9 The NLC covers an area of approximately 605 800 square kilometres that includes the four major (predominantly non-Aboriginal) centres of Darwin, Nhulunbuy, Katherine and Jabiru, and some 200 Indigenous communities (including homelands and outstations).12 Many of these communities are in remote parts of the region, and are accessible only by four wheel drive vehicles across unsealed roads (that are subject to flooding in the wet season) or by air, and the standards of telecommunication services vary. Approximately 36 000 Aboriginal people live in the area (some 80 per cent of them in remote locations) the majority of whom are multi-lingual and speak an Aboriginal language as their first language. Customary law continues to be practiced in many communities.

1.10 The NLC is divided into seven regions: Darwin-Daly-Wagait, West Arnhem, East Arnhem, Katherine, Victoria River District, Ngukurr and Borroloola-Barkly. As at 1 May 2017, the NLC had 288 staff13 located in the head office in Darwin and in regional offices in Katherine, Jabiru, Maningrida, Nhulunbuy, Timber Creek, Tennant Creek, Ngukurr, Borroloola and Wadeye (Figure 1.1). A new office is planned to be opened at Galiwinku on Elcho Island in July 2017.

Figure 1.1: Northern Land Council regions and offices, 1 May 2017

Note: The southern parts of the Borroloola Barkly region are serviced by an NLC regional office located in Tennant Creek, situated within the CLC region. Tennant Creek is the centre for the Borroloola Barkly region.

Source: Northern Land Council.

1.11 In 2015–16, the NLC’s operational expenditure was $39.1 million, funded by revenue of $20.2 million from the Aboriginals Benefit Account (under section s.64(1) of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act); $4.9 million from consolidated revenue for functions under the Native Title program; $11.3 million from the Australian and Northern Territory governments for a range of grants and programs, including the Caring for Country program, and own source income of $2.7 million.

Organisational structure and functions

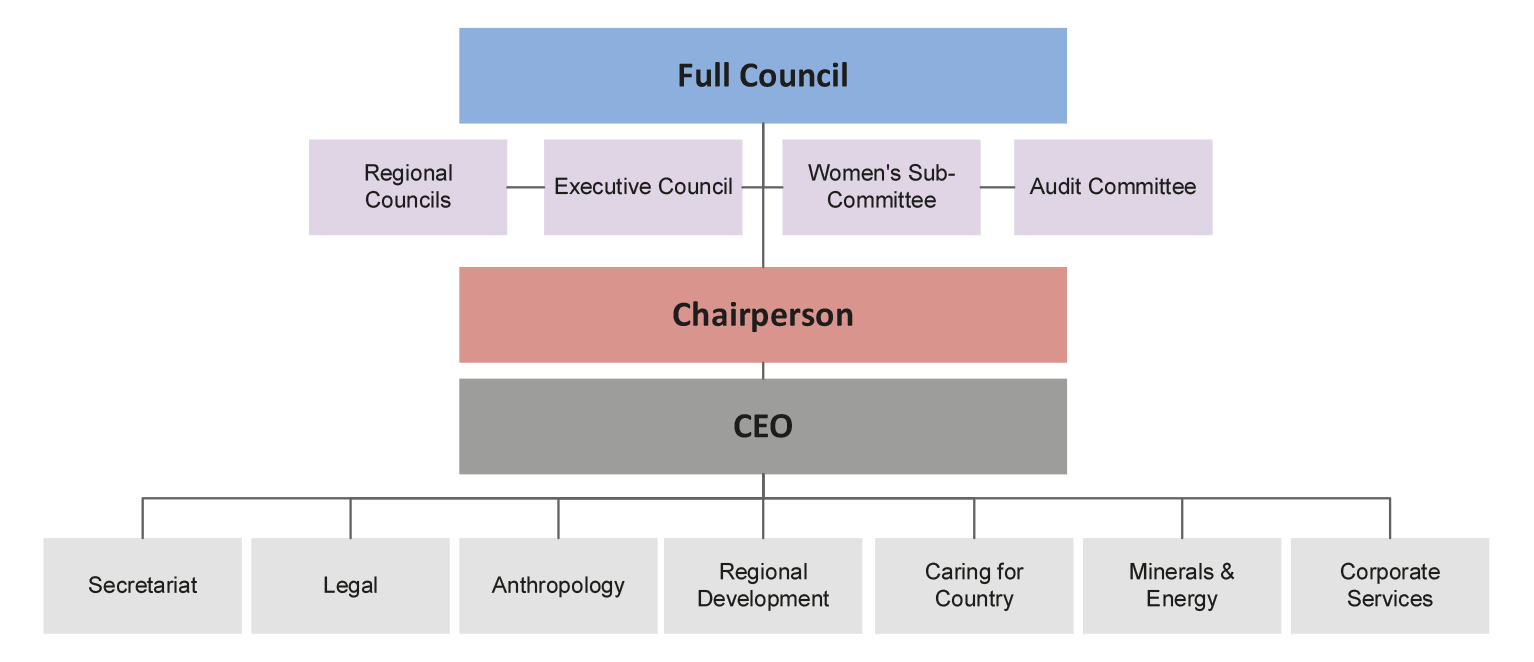

1.12 The NLC consists of elected representatives of Aboriginal people living in the region, referred to as members of the Full Council, and an administrative arm managed by the NLC’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The NLC combines its functions under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act and as a native title representative body under the Native Title Act, and the council’s corporate functions support the administration of the Caring for Country program. The NLC’s organisational structure as at 1 March 2017 is shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Northern Land Council organisational structure, 1 March 2017

Source: ANAO review of NLC documents.

Full Council

1.13 The Full Council represents the rights of the Aboriginal people within the NLC region, shapes the policy and strategic direction of the council, and approves agreements regarding the use of Aboriginal land under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. The NLC has 83 members: 78 are elected by their communities, outstations or an incorporated body within the region for a three-year term, and there are five positions for women, co-opted to serve on the Full Council to promote women’s participation.

1.14 The Chairman and Deputy Chairman of the Full Council are elected from and by members of the Full Council. The Chairman is an employee of the NLC and his salary is determined by the Remuneration Tribunal.14 The three-year term of the current Full Council commenced in November 2016 at the 114th meeting of the Northern Land Council. At this meeting the Chairman was returned for a second term.15 Meetings of the Full Council are convened twice a year.

1.15 Members of the Full Council also serve on seven Regional Councils and on an Executive Council, under s.29A of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act that allows for the appointment of committee(s) of members to assist the Full Council to perform its functions or exercise its powers. The role of the:

- Regional Councils includes to: consult communities in their region about issues directly relevant to the Land Council; communicate important issues back to their communities; and communicate with the Executive Council any issues affecting their local community. Regional Councils meet twice a year; and

- Executive Council is to manage business between Full Council meetings and exercise powers delegated by the Full Council. The Executive Council comprises the Chairs of the seven Regional Councils, and the Chairman and Deputy Chairman of the Full Council. The Executive Council meets six times a year, and has the delegated authority to approve agreements (up to a term of 40 years) under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

Chief Executive Officer

1.16 The Executive Council appoints the CEO16 who has day-to-day responsibility for the administration and operation of the council. He is supported by a team of eight managers of the NLC’s seven branches (the Regional Development branch has two managers) who deliver the NLC’s services and form the Leadership Group for the council’s administration.

Administrative and strategic reform

1.17 In March 2013, the report of an external review of the NLC’s governance framework (undertaken shortly after the resignation of the NLC’s CEO) identified a ‘fundamental breakdown in the governance framework at the NLC’, resulting in serious failings in almost all aspects of the council’s administration.17 (The position of CEO was not permanently filled between the resignation of the former CEO in October 2012 and the appointment of the current CEO). On 10 December 2014, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs wrote to the NLC expressing his concern about issues of the council’s financial management, and requested a financial management strategy for the council’s operating budget.

1.18 On 27 February 2015, the NLC’s CEO and senior officials appeared before the Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee, following the Australian National Audit Office’s financial statements audits that had found weaknesses in the NLC’s financial management and reporting. The committee was highly critical of the NLC’s progress in improving its internal management systems, and raised concerns about the operation of the NLC’s Audit Committee. Two months later, on 30 April 2015, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs wrote to the NLC Chairman expressing his concern with aspects of the council’s internal governance, compliance with financial reporting requirements and financial sustainability.18

1.19 In the Northern Land Council Annual Report 2014–1519, the CEO refers to the NLC’s appearance before the Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee as a ‘serious wake-up call’ about the operation, culture and efficiency of the council, and outlined a reform agenda:

In the months since, with assistance from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, we have worked tirelessly to implement significant improvements to our governance, financial, administrative and other systems. The Leadership Group has met several times to deal with those matters; a new audit committee has been appointed; BDO Financial Services have been hired to prepare the annual accounts; new staff, including a Chief Financial Officer, will be appointed by the end of the 2015 calendar year.

Within this short period, we have focused on much tighter financial management and budgetary control and I am proud to report that we have made significant improvements in our financial position. There are continuing reviews of all facets of operations across all NLC branches. Efficiencies and needs are being identified, and that information will be fed into future budget preparations.

1.20 The NLC is also undergoing review and reform of its strategic direction. In his introduction to the NLC Strategic Plan 2016–20, the Chairman notes that the functions of the NLC (as set out in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act and Native Title Act) continue to make up most of the council’s workload, but the NLC ‘must look forward to this era of post-determination’20, and the strategic plan can be read as the blueprint for how the NLC proposes to realise that vision.

We want to be an integral force in the growing push to develop Northern Australia…the NLC must position itself to have a primary role on behalf of Aboriginal people in the planning for northern development, so that our constituents can enjoy the economic benefits on their own terms, without any adverse impact on their culture.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

1.21 The Indigenous Affairs Group within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) is responsible for the department’s strategic priority to ‘enhance the ability of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to improve their lives’ (primarily through administration of the Australian Government’s Indigenous Advancement Strategy21), and provides advice and support to the Minister for Indigenous Affairs, including in relation to Land Councils and the exercise of his powers under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act and Native Title Act.

1.22 The Indigenous Affairs Group operates through six divisions22 divided into 28 branches, with staff located in PM&C’s Canberra offices and in a network of 39 regional offices across Australia (five in the Northern Territory). For 2016–17, the Indigenous Affairs Group within PM&C had a budgeted average staffing level of 1520 staff, with a departmental budget for program support of $280 million.

1.23 Land Councils engage with departmental staff in Canberra and in the regional network subject to their various responsibilities, including the administration of funds for operational and capital expenses (from the Aboriginals Benefit Account), the Native Title program and the Indigenous land management programs. There is also a Portfolio Bodies section (within PM&C’s Financial Accounting branch of the Financial Services Division) that engages with Land Councils primarily about their annual reporting obligations.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.24 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the governance of the Northern Land Council in fulfilling its responsibilities and obligations under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, Native Title Act 1993 and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

1.25 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted high level criteria that the Northern Land Council’s:

- operations, through the Full Council, Regional Councils and Executive Council are effective in representing the interests of Aboriginal people in the region;

- administrative arrangements and systems—including documents management, human resources management and information and communications technology systems—support the council’s functions and delivery of services; and

- corporate planning and performance reporting are effective and meet legislative requirements.

1.26 While focussing on the Northern Land Council, findings in this audit report may be useful and / or relevant to other Land Councils.

Audit approach

1.27 The ANAO:

- examined records and interviewed staff in the NLC’s head office in Darwin and in the Katherine regional office, and held a phone conference with staff in the Tennant Creek regional office;

- attended a meeting of the NLC Executive Council;

- attended two meetings of the NLC Leadership Group and one meeting of the Audit Committee;

- examined records and interviewed staff from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, located in Canberra and in Darwin; and

- met with staff from the Northern Territory Government.

1.28 The Audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $410 000.

2. Operation of the Council

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the operation of the Northern Land Council (NLC) in representing the interests of the Aboriginal people in the region, and of the secretariat in supporting the work of the council.

Conclusion

The NLC is improving its processes for representing the interests of Aboriginal people in the region, but more remains to be done to demonstrate that these processes are effective. The NLC has yet to implement measures to assess the performance of the Full Council, Regional Councils and Executive Council and of council members, in engaging with NLC constituents and representing their rights and interests. A review and restructure of the Secretariat branch aims to streamline and improve its support for the operation of the council, with a branch plan and performance indicators recently developed.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO suggests that both the NLC and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet improve the management of complaints about the NLC’s performance (paragraphs 2.39 to 2.43).

Does the Northern Land Council effectively represent the interests of the Aboriginal people in its region?

The NLC is improving its representation processes but has collected insufficient information to demonstrate how effective representation has been in practice. In this regard, the council has commenced initiatives to monitor and assess councillors’ performance, manage complaints and conduct stakeholder surveys that will potentially provide useful information on the effectiveness of its performance in representing the interests of the Aboriginal people in the region. However, the NLC has yet to implement an internal audit function to provide assurance that administrative processes and procedures are being followed. The council has been assessed by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet as satisfactorily performing its functions as a native title representative body. The NLC has complied with some requirements under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 for nominating councillors and conducting council meetings and is working towards full compliance.

2.1 The NLC’s annual reports from 2004–05 provide performance information on a range of services and functions delivered by the council including the number of: permits (to access Aboriginal land) processed; consultations held with Traditional Owners relating to mining activities on Aboriginal land; and land use agreements finalised.

2.2 The information provides quantitative data on the NLC’s workload (including that services continued to be delivered irrespective of the governance and financial reporting concerns in recent years), but gives little insight into how well the NLC performs against its undertaking to: consult with and act with the informed consent of Traditional Owners in accordance with the Aboriginal Land Rights Act; communicate clearly with Aboriginal people taking into account the linguistic diversity of the region; be responsive to Aboriginal people’s needs and effectively advocate for their interests; be accountable to the people we [the NLC] represents; and treat our stakeholders with respect.23

2.3 To assess the NLC’s performance in representing the interests of the Aboriginal people in its region, the ANAO examined:

- the extent to which the NLC is compliant with legislative requirements in Part III of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, that underpin transparency and accountability in the operations of the council;

- how the council performs its functions as a native title representative body;

- the development and publication of a corporate plan and annual report (including from 2015–16, an annual performance statement) as required under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, to set and communicate the council’s directions and priorities;

- the monitoring and oversight of councillors’ conduct and performance in undertaking their roles and responsibilities;

- the management of complaints; and

- mechanisms, such as the conduct of stakeholder surveys and internal audit and quality assurance functions, that provide independent assessment of performance.

2.4 The NLC’s Accountable Authority has an important role in ensuring that the council complies with its legislative requirements and delivers on its commitments. The appointment of two positions (the NLC Chairman and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) as the Accountable Authority under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 reflects the complex legislative and cultural environment in which Land Councils operate. Established by government as independent statutory authorities to represent Northern Territory Aboriginal people regarding the ownership and use of their lands, the councils must be accountable to their constituents and also to the broader community, via Parliament, for their use of government resources.

Legislated requirements under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act

2.5 The NLC’s compliance with legislative requirements under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act pertaining to the nomination and appointment of council members, and to the conduct of council meetings, is summarised in Table 2.1. It shows a mixed performance in complying with these requirements, many of which had been neglected for a number of years. In discussion with the ANAO in late 2016 and early 2017, the NLC revealed a number of initiatives to progress the compliance matters, discussed below.

Table 2.1: Northern Land Council compliance with selected requirements of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act

|

Legislative requirement pertaining to the nomination and appointment of council members, and conduct of council meetings |

NLC compliant |

|

Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 |

|

|

Section 29(1): Methods of Choice for Membership of a Land Council |

Yes |

|

Section 29AA: Register of interests of members of Land Council |

Yes |

|

Section 31(7A-D): Written Rules |

Yes |

|

Section 31(10-11): Minutes of Meetings |

partial |

|

Section 29A: Establishment of Committees |

partial |

|

Section 28: Delegations |

partial |

Source: ANAO.

2.6 With regard to compliance, advice from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) is that the Aboriginal Lands Rights Act has compliance requirements relevant to the powers, functions and responsibilities of several parties24, and that:

- it appears that many compliance provisions in the [Aboriginal Land Rights Act] effectively operate as guidance and specific provisions for the treatment of instances of non-compliance are limited. In many instances the relevant treatment is implicit by reference to related provisions;

- instances of non-compliance by both Land Councils and the Minister are not unknown, but may have little or no material effect on dealing with the particular matter at hand; and

- the Minister appears to have substantial discretionary latitude in responding to instances of non-compliance by a Land Council.

2.7 While it is the responsibility of the NLC’s Accountable Authority to ensure the council’s compliance with legislative provisions, there may be benefit in engaging with other Land Councils and with PM&C (perhaps through the bi-annual strategic forums, discussed in Chapter 4) on the management and monitoring of compliance requirements in the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

Method(s) of choice for membership of a Land Council

2.8 Section 29 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act deals with the membership of Land Councils. Specifically, section 29(1) includes that members shall be Aboriginal people living in the area of the Land Council, chosen by the Aboriginal people in the area in accordance with a method(s) of choice approved by the Minister from time to time.

2.9 The ANAO reviewed the documentation relating to nominations to the NLC’s Full Council in November 2016. Based on this limited work, there was nothing to indicate that the process had not been conducted in line with the NLC’s method(s) of choice approved by the responsible Minister in 2001. There were extensive files that included nominations from the 54 Aboriginal communities or outstations within the NLC region from which members can be elected, documentation of processes to appoint the appropriate number of members from each community, and kits that combined all the necessary information for potential members.25 However, the process is complicated and lengthy, and would need to be subject to an internal audit or quality assurance process to provide confidence that it was properly carried out.

2.10 The NLC had submitted a revised method(s) of choice to the Minister for Indigenous Affairs on 27 June 2016, but approval was not received until November, too late to be applied to nominations for the new Full Council. The revised method(s) of choice detail the Terms and Conditions for Membership (not in the earlier version) providing clarity on how a member continues to hold office, or is removed by the NLC or nominating organisation or community.

2.11 The NLC advised in November 2016 that a comprehensive review of council membership (endorsed at the 112th meeting of the Full Council held in May 2016) will be undertaken over the following two years and will examine whether the present geographical spread and membership numbers (as set out in the method(s) of choice 2001) provide adequate representation for NLC constituents, some 15 years on.

Register of interests of members

2.12 Section 29AA of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act provides for the keeping of a register of interests of members of a Land Council, in accordance with a determination of the Minister.26 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet advised that in 2015 the Minister for Indigenous Affairs declined to agree to the Department engaging with the Northern Territory Land Councils about the drafting of such a determination.

2.13 In the absence of a determination, council members are currently expected to comply with NLC policy and declare a conflict of interest as items arise during council meetings, and either remove themselves from, or not participate in, the subsequent discussion and voting. The declarations are recorded in council meeting minutes. In this regard, the minutes of seven meetings of the Full Council (May 2014 to November 2016) and four meetings of the Executive Council (May 2016 to December 2016) recorded members declaring conflicts of interest and removing themselves from the meetings on 20 occasions.

2.14 The NLC is, however, developing registers of members’ interests to assist with compliance for agreements and for reporting and auditing purposes. As at January 2017, the NLC has produced books for each of the NLC’s seven regions to be developed as registers of members’ interests and conflicts of interests, as they are declared at meetings and / or are brought to the attention of the council.

Written rules

2.15 Section 31 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act deals with meetings of Land Councils. Specifically, section 31(7A-D) requires that a Land Council must make written rules in relation to the convening and conduct of council meetings and make them available to the Traditional Owners and other Aboriginal people living in the region for inspection. The rules must be approved by the Minister.

2.16 The NLC has developed a handbook, the 2016 Rules for Councillors (October 2016), to assist elected members fulfil their roles.27 The handbook was approved by the Minister for Indigenous Affairs on 11 November 2016 as the NLC’s ‘written rules’ for the conduct of council meetings. The 2016 Rules for Councillors handbooks have been professionally printed, distributed to all council members, with copies freely available through NLC offices.28

Minutes of Land Council meetings

2.17 Section 31(10-11) of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act requires Land Councils to keep minutes of their meetings and make them available (other than the parts of the minutes that relate to an excludable matter29) to the Traditional Owners of land in the area of the council, and to any Aboriginal people living in the region. Minutes of council meetings are included in Agenda Books (prepared for council meetings) for endorsement and resolution, but, for reasons of confidentiality, they are not distributed outside of the meetings. The minutes are recorded on digital files and stored securely, with access limited to the CEO and his executive assistant, but available on request from Aboriginal people living in the area.

2.18 In April 2017, the NLC advised that work is underway to rewrite and republish the handbook, 2016 Rules for Councillors — some of the content needs to be more explicit and new matters will be added, including the rights of councillors to access minutes and how they can go about that. The information is also to be provided orally at all council meetings. The NLC further advised that councillors are responsible for keeping their constituents informed, but the NLC will further review the process of circulating minutes of council meetings.

Committees and delegations

2.19 Section 29A of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act allows for the appointment of committees of members to assist the Council in relation to the performance of its functions or exercise of its powers. As at December 2016, the NLC’s s.29A committees are the NLC’s Regional Councils, the Executive Council and the Women’s Sub-Committee. The resolution establishing the Regional Councils and Executive Council was made at the Full Council meeting of 1 October 1996, and remains in place.

2.20 The Act includes the requirement that the appointment of a committee is by a notice in writing and the Land Council must make written rules relating to the convening and conduct of meetings. The ‘written rules’, in the form of the NLC’s handbook, 2016 Rules for Councillors (referred to above), also applies to the Regional Councils and Executive Council. The NLC advised that it has not met the requirement to issue notices in relation to committees, but will include this in an update to the procedure for council nominations and elections.

2.21 Section 28 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act allows a Land Council to delegate some of its functions or powers, including to the Chairman, a committee of the Council, or to an NLC staff member. The NLC maintains an Instrument of Delegation that records the delegations of the Full Council, including the meeting at which the delegation was endorsed. In March and April 2017, the NLC advised:

In 1996 the Full Council resolved to delegate its delegable function and powers to various levels of the council and staff. The Instrument of Delegation came into effect on 10 March 2000 when the document was executed under seal and still stands. Since then a number of amendments have been made to the delegations considered desirable to align with legislation and management changes, they have been similarly executed under seal.

The various amendments are yet to be consolidated into a single document. The CEO has established an internal working group to comprehensively review all delegations within the organisation with a view to consolidate the delegations into a single instrument. The single instrument (and any proposed changes to delegations) will be presented to the Full Council for approval.

2.22 As at 11 May 2017, the NLC advised that the review had been completed and the various amendments consolidated into a single document, and that the document was approved by the Executive Council at the council meeting of 20 April 2017 (and recorded in the minutes of the meeting).

Conduct of functions as a native title representative body

2.23 The NLC combines its functions as a representative body under the Native Title Act with its statutory functions under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act to improve administrative efficiency and reduce management costs, but is required to report on them separately.30

2.24 Section 203BA of the Native Title Act 1993 deals with how functions of native title representative bodies are to be performed (refer Appendix 3Appendix 1). Specifically, section 203BA(2) deals with the entity’s organisational structures and processes that must (among other things): promote the satisfactory representation of the body of native title holders; promote the effective consultation with Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders living in the area; and operate in a fair manner, particularly with regard to opportunities for Aboriginal peoples’ and Torres Strait Islanders’ participation, consultation, and decision making.

2.25 Under the Native Title Act, eligible bodies can apply to become a native title representative body at the invitation of the responsible Minister.31 On 5 May 2016, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs wrote to the NLC that, based on the NLC application and advice from PM&C, he was ‘satisfied that the NLC satisfactorily performs its existing functions as a representative body under the Act and would be able to continue to do so’, and recognised the NLC as the native title representative body for the prescribed area, for the period 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2018.32

Development and publication of a corporate plan and annual report

2.26 Under sections 35, 39 and 42 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, Accountable Authorities of Commonwealth entities are required to: develop and publish (on the entity website) a corporate plan annually for the entity; and report annually on its operations and finance. Commencing in 2015–16, with implementation of the enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework, the annual report must include an entity’s (non-financial) performance statement. Both documents should be provided to the responsible Minister and the Finance Minister.

2.27 The NLC has developed and published a strategic plan and corporate plans.33 The:

- Northern Land Council Strategic Plan 2016–2020 sets out the council’s strategic direction and describes ‘the way we intend to carry out our statutory responsibilities, the goals we set to achieve and our vision for the future’34; and

- Northern Land Council Corporate Plan 2015/16–2018/19 and Northern Land Council Corporate Plan 2016–17 to 2019–20 set out the activities and strategies to achieve the strategic goals.

2.28 The NLC has published its corporate plans and included the publication of the required performance statement in its annual report, Northern Land Council Annual Report 2015–16. The annual report was provided to the Minister within the required time frame. (The NLC’s planning and performance reporting is further discussed in Chapter 4).

Performance of council members

2.29 The NLC handbook 2016 Rules for Councillors sets out the roles of the members and functions of the various parties (the Full Council, Regional Councils, Executive Council, Chairman, Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive Officer) and provides a mix of quantitative and qualitative measures against which their respective performance will be assessed.

2.30 The measures align with the NLC’s goal of good governance articulated in the strategic plan and corporate plans. The roles and performance measures for the Full Council, Regional Councils and Executive Council are shown in Appendix 4. The previous version of the written rules, Draft Full Councils Members Induction Handbook 2013–16, also set out roles and responsibilities, but did not provide performance measures.

2.31 As at December 2016, several of the quantitative measures are recorded by the NLC (for example, councillors’ attendance at meetings is noted for the payment of sitting fees, and the number of agreements passed is included in the NLC’s annual reports). However, more needs to be done to be able to assess the qualitative measures, for example, ‘respect other council members, staff and visitors to council meetings’ and ‘manage conflicts of interest’.35

2.32 If fully implemented—that is, performance targets are established, performance is monitored and recorded, and results are provided to and reviewed by council members—the performance measures will provide insight into the effectiveness of the operations of the council, and the standards of governance provided by council members.

Governance training

2.33 Governance training for members of the Full Council was delivered on the first day of the Full Council meeting held in November 2016, and involved the active participation of all members. A report compiled after the meeting collated members’ opinions about the training. Feedback was generally very positive, with the training well received and considered beneficial.

2.34 Minutes of the Executive Council meeting, 13–14 December 2016, record that the CEO has engaged Deloitte to assist with on-going governance training, and to deliver tailored governance training for members of the Executive Council. A letter of engagement from Deloitte, 7 March 2017, sets out the terms of reference for the training, to be delivered over five two-hour sessions throughout the year.

Managing complaints

2.35 Complaints about the operation of the NLC may be lodged with the council, PM&C or the Minister’s office, as well as other Commonwealth agencies including the Commonwealth Ombudsman and Fair Work Ombudsman.

Complaints lodged with the NLC

2.36 The NLC’s External Complaints Policy and Procedures, August 2015, sets out the process for managing and reporting complaints, with the NLC’s risk management framework referencing the importance of effective complaints handling. While comprehensive, as at 1 March 2017 the document has not been formally endorsed by the NLC executive and implemented across the organisation. An online form for lodging a complaint is included in the re-design of the NLC’s website (the contract has been finalised for the development of the new website, and work commenced in March 2017).

2.37 Since February 2015, the NLC has allocated a staff member to manage external complaints and maintain a register to record and track them. The register is manually maintained on an Excel spreadsheet. As at 31 March 2017, 55 complaints had been registered, of which 45 were closed. The complaints relate mostly to matters of traditional ownership and royalty payments (or a lack of progress in resolving the issues). The NLC’s responses are approved and signed by the CEO. Of the 55 complaints, one involving the Fair Work Ombudsman and eight raised by the Commonwealth Ombudsman were resolved.

2.38 The External Complaints Policy and Procedures, August 2015 includes that a consolidated report on complaints should be provided annually to the Audit Committee. There is no evidence of such a report being made to the Audit Committee, in minutes of the 10 committee meetings convened between April 2015 and November 2016.

2.39 To support the full implementation of the complaints management process, the NLC should consider providing training in complaints handling for selected staff, and, more broadly, make staff aware of how to respond when people refer to lodging a complaint. For example, could the matter be dealt with appropriately without escalation to a formal complaint, or by the provision of information?

2.40 The NLC should also consider how complaints are reported, in addition to the report to the Audit Committee. Senior managers have visibility of complaints relevant to their branch, but regular reporting, perhaps every six months, to the Leadership Group would ensure managers are aware of all matters raised through complaints.

Complaints lodged with PM&C and / or the Minister for Indigenous Affairs

2.41 PM&C maintains a dedicated email address and hotline for the lodgement of complaints, and manages correspondence addressed to the Minister for Indigenous Affairs through the department’s Ministerial Correspondence Unit. Advice from the department’s Governance Audit and Reporting Branch (21 December 2016) is that: ‘searches of PM&C’s data holdings managed by the Governance Audit and Reporting Branch (Fraud and Complaints), the Portfolios Section and the Ministerial Correspondence Unit for complaints made to the Department about the NLC, resulted in a nil find.’

2.42 With regard to the Ministerial Correspondence Unit, there is no specific procedure set out in the Guide to preparing and handling Ministerial Correspondence, 23 April 2015 for the management of complaints—complaints are not categorised as such in the database used to manage the correspondence. For the purpose of this audit, PM&C manually reviewed the Ministerial Correspondence Unit database and identified complaints about the NLC lodged with the Minister’s office from 2013. The list of complaints provided did not support analysis of the nature and / or volume of complaints lodged, and provided no information as to how they were resolved.

2.43 PM&C does not have procedures to comprehensively monitor or undertake any routine analysis of these complaints that would provide insight into aspects of the NLC’s operations and performance. The department could consider tracking and analysing complaints processed by the Ministerial Correspondence Unit, and engaging more closely with the NLC as to their content.

Stakeholder surveys, internal audit and quality assurance

2.44 As at March 2017, the NLC has no internal mechanisms to provide independent assessment of council members’ performance, or assurance that the NLC’s processes are being properly implemented. Going forward, the NLC: intends to conduct council and stakeholders’ satisfaction surveys across the NLC region36; and agreed at the November 2016 Audit Committee meeting to consider establishing an internal audit function within the financial year (further discussed in Chapter 3). In the longer term, the NLC could also consider implementing some form of quality assurance function, such as the conduct of a peer review, of the council’s legal and anthropology services.

Does the Secretariat branch effectively support the operation of the Northern Land Council?

The NLC has reviewed and restructured the Secretariat branch to streamline services to councillors and the Chief Executive Officer. Most recently, the outcome of a workshop held in late March 2017 renamed the branch (to the Executive branch), better defined the responsibilities of each function within the branch, identified branch priorities, and developed a business plan and performance measures to assess the effectiveness of the branch in supporting the operations of the council. There was no business plan and few procedural documents from previous years upon which to base the work of the branch, going forward.

Secretariat branch structure

2.45 The structure and functions of the Secretariat branch have been subject to change in recent years, illustrated in the NLC’s annual reports from 2014–15 and in the council’s corporate plans over the same period. The most recent re-structure of the branch, taking effect in October 2016, resulted from an internal review of position descriptions and the functions of the branch, and the need to fill positions that had been vacant for some time.

2.46 In an email to all staff, 3 October 2016, the NLC’s CEO informed staff that the re-structure aimed ‘to streamline the functions around support for the Council, Chairman and CEO by utilizing a flat structure with a view to efficient delivery of the branch’s functions and delivery of the strategic plan as set by the Council’.37 Changes included:

- abolishing the Communications branch and amalgamating the media and publications / communications functions with policy functions in the Secretariat branch, to reflect the outwards focus of policy development deriving from the council;

- the transfer of corporate compliance functions to the Corporate Services branch; and

- the sharing of logistics—contacting council members and arranging their travel to meetings—with the NLC’s Regional Development branch38 (this arrangement applied for the 114th meeting of the Full Council held in November 2016), as well as responsibility for the management of permits (to access Aboriginal Land).

2.47 At the meeting of the Executive Council held on 13–14 December 2016 the new branch manager provided an overview of the functions of the re-structured Secretariat branch.39 While the NLC had provided secretariat services to the council, there was no business plan from previous years on which to build, and few documented procedures for the secretariat functions in the branch. For example, there was no documented information about the activities that comprise ‘council services’, and more complex processes, such as organising the nominations for a new three-year term of the Full Council, relied on the experience of staff in the branch rather than documented guidance or procedures.

2.48 The NLC subsequently held a workshop on 24 March 2017 (convened by an external consultant) to define the responsibilities of each function within the branch, identify priorities, and develop a business plan and performance measures for the branch. The outcomes of the workshop included a proposal to rename the branch to the Executive branch (to more clearly define the role of the branch) and the identification of five core activities.40

Payment of sitting fees and other entitlements

2.49 In August 2016, in a joint initiative, the Secretariat branch and Finance section issued a new procedure for the payment of sitting fees to council members. Section 77 of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act provides for the payment of sitting fees and allowances to members of Land Councils, with rates determined by the Remuneration Tribunal.41 Sitting fees are currently $293 per sitting day (also allows for half day attendance), and members are entitled to travel allowance, currently $28 per day.

2.50 Taking effect at the meeting of the Full Council held in November 2016, the NLC advised that it had stopped providing any cash payments at council meetings, and that at the November meeting: sitting fees were paid by electronic bank transfer the following week42; and travel allowances were also paid daily (from the first day of the meeting) by electronic bank transfer.

3. Administration and Service Delivery

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Northern Land Council’s (NLC’s) administrative arrangements to support its functions and the delivery of services. The chapter also examines the NLC’s progress in implementing administrative reforms.

Conclusion

Subsequent to substantial criticisms about failed administrative processes, practices and controls, the NLC has commenced a range of initiatives to better support its functions and the delivery of services. These initiatives have included enhanced financial reporting capability and records management, and the establishment of a competent Audit Committee to oversee reforms across key corporate functions and policies. Some progress has been made in modernising the NLC’s dysfunctional information and communications technology systems, with further improvements subject to available funding. Improvements in service delivery are supported by management and budget information that was not previously available to managers. The NLC could more effectively manage its reform agenda given the extent of the changes underway.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO suggests that the NLC improve its procurement processes (paragraph 3.15) and the format for internal management reports (paragraph 3.60). The ANAO recommends that the NLC better manage and monitor its reform agenda and communication with staff about the changes (paragraph 3.68).

Do administrative arrangements effectively support the work of the Northern Land Council?

The NLC’s administrative arrangements do not yet effectively support the work of the council. Prior to 2015, the management and maintenance of core enabling functions, including information and communications technology systems, human resource management and records management was poor, with serious weaknesses in financial management, fraud control and the management of risk. Commencing in 2015, the council is implementing an extensive reform agenda across all administrative functions, with progress having been achieved in corporate planning and reporting, financial reporting and in internal governance through the operations of an Audit Committee. Other reforms, including in human resource and records management, are well underway with an overhaul of the council’s information and communications technology systems in the early stages.

3.1 In early 2015 the NLC’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) commenced a ‘complex change management initiative where it is not simply about changing systems and procedures—as large a task as that already is—but also about changing the way we work and aligning our day-to-day corporate culture to our vision and mission’.43

3.2 As at March 2017, extensive reforms were underway at the NLC. Almost all aspects of the council’s administration and service delivery, including governance functions and corporate services, are subject to review and reform. There is little ‘business as usual’ activity in the organisation, with new and recent appointments to most of the council’s senior management positions and specialist positions.

Information and communications technology systems

3.3 An external review of the NLC’s information and communications technology (ICT) systems completed in October 201644 found the NLC’s ICT environment to be ‘dysfunctional, reliant on numerous manual processes and exposes the NLC to significant operational and security risk’. The review identified over 20 serious weaknesses in the ICT systems that undermined the council’s capacity to carry out core activities, with the ‘current ICT team consumed by keeping the lights on and reacting to issues as they arise’.

3.4 Weaknesses identified in the review impact across the organisation and included: no functioning intranet; duplication of client and project databases45; security vulnerabilities leading to significant data loss; inconsistent core ICT practices (including document management and the resulting reliance on manual processes); lack of visibility and inability to share information between branches; and no appropriate backup or disaster recovery strategies.

3.5 The review outlined seven ICT initiatives encompassing 30 individual projects to be undertaken over a two-year period, including the immediate need to establish a project management office and recruit staff with the necessary expertise.

3.6 Advice from the NLC as at 1 March 2017 was that it intended to establish a project management office while undertaking, where possible, urgent projects that could be managed within existing capabilities or that were already funded, including an upgrade of the email system and installation of a new human resource management system. In the longer term, other projects will depend on available funding.

3.7 The NLC has developed an ICT project plan that lists the various projects to be implemented over a two-year period (to December 2018), with associated timelines, costs and staff responsibilities. As at April 2017, work underway includes consolidating the NLC’s various databases, and improving video conferencing and technical capabilities in the regional offices and for staff working in remote locations.

3.8 From February 2017, NLC staff also have access to a new intranet site. While still being populated, the NLC advised that the new features include: a centralised calendar showing all the activities across the organisation to facilitate better coordination and planning of remote meetings and consultations across the region; project management and reporting tools (initially for processing land use agreements); and messaging services.

Financial management and reporting

3.9 The NLC budget comprises several funding sources (shown for 2015–16 in Table 3.1) administered through the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), as well as specific purpose grants from various Australian and Northern Territory Government agencies, and own source income.

Table 3.1: NLC funding sources, 2015–16

|

Activity/function |

Funding source |

Value 2015–16 |

|

Operational and capital expenditure |

Aboriginals Benefit Account, administered through PM&C |

$20.2 million |

|

Native title representative body |

Appropriation, administered through PM&C |

$4.9 million |

|

Indigenous Ranger Program |

Appropriation, administered through PM&C Aboriginals Benefit Account: administered through PM&C1 |

$2.1 million $2.3 million |

|

Environmental and liaison functions |

Special purpose grants |

$6.9 million |

|

Own source income |

Rendering of services2 and interest from deposits. |

$2.7 million |

Note 1: Additional critical operational funding for the NLC Ranger Program was provided from the Aboriginals Benefit Account (subsection 64(1) of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act) as a one-off allocation for 2015–16 only.

Note 2: Operating on a cost-recovery basis, including from the processing of applications for minerals-based exploration licences and petroleum-based exploration permits.

Source: ANAO, from NLC Annual Report 2015–16.

3.10 Prior to November 2015 and the appointment of a new Chief Financial Officer, the NLC’s financial management and internal reporting capabilities were poor, including not meeting reporting requirements for the various funding sources. The NLC used only the basic transactional capacity of their financial system (SAGE), and rudimentary reports were generated using a combination of custom built add-ons to the financial system and Excel spreadsheets. They did not easily provide a consolidated picture of the NLC’s finances, and contained minimal budgetary information against which actual expenditure could be monitored.

3.11 The situation improved in 2016, through: enhanced reporting capabilities (albeit manually using Excel spreadsheets); and upgrading the financial system in readiness to implement, in early 2017, automated reporting together with Project Job Costing and Asset Management modules. The NLC advised that further planned upgrades will make the system more stable, and expand the reporting capability.

3.12 Prior to February 2016, the NLC executive and senior staff had no visibility of the organisation’s allocation of resources and internal budgets. Throughout the year, the NLC finance team developed and refined its management information reports, and by December 2016, monthly reports were being provided to the:

- Leadership Group, Executive Committee and Audit Committee. Consolidated reports provide comprehensive information on total budgeted and actual income and expenditure for the NLC, including breakdowns by funding source, branch and project. They also provide a balance sheet and cash flow summary and specific information on consultancy expenditure and debtors; and

- branch managers and project managers. Branch reports detail budgeted and actual branch level income and expenditure by funding source as well as by individual project.

3.13 Improvements in the financial systems also support the NLC’s implementation of recommendations in the ANAO’s audit of its financial statements 2015–16, which identified weaknesses in expenditure controls including in the processing of purchase orders. From early 2016, online processing of purchase orders (with the exception of travel) has been gradually implemented, with a slow phasing out of paper purchase order books.46 From February 2017, procurement is linked to budgets, and system controls introduced to help ensure that purchase orders are correctly approved prior to a liability for goods and services being incurred and invoices raised.

3.14 With regard to the procurement of goods and services, as at 1 March 2017, the NLC did not have a procurement policy, and procurement practice did not meet requirements set out in the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. The NLC is not a prescribed corporate Commonwealth entity as listed in section 30 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014, and is not required to comply with Commonwealth Procurement Rules. However, to do so voluntarily would promote better practice by encouraging: value for money; competition; efficient, effective and ethical procurement; and accountability and transparency in procurement.

3.15 Supplies of goods and/or services may be sourced or contracted by the NLC on the basis of a list of providers previously engaged, and there is limited evidence of competitive tendering or value for money consideration.47 The NLC should improve its procurement process across the organisation.

Travel

3.16 Travel is a significant expense for the NLC. The ANAO’s 2015–16 financial statements audit examined the NLC’s internal controls for the approval of individual staff travel, and found them to be appropriate: staff must have their travel approved by their line manager, and for senior staff, by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO).48 The consolidated monthly reports provide the total expenditure on travel for the organisation. The amount spent on travel (excluding use of the NLC’s fleet vehicles) as a percentage of staff costs reduced over the period 2013–14 to 2015–16 (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2: NLC travel costs and staff costs, 2013–14 to 2015–16

|

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

Total staff costs1 |

20 851 |

18 233 |

21 563 |

|

Travel costs |

4 198 |

2 283 |

2 693 |

|

Travel costs as a percentage of staff costs |

20.1% |

12.5% |

12.5% |

Note 1: Total staff costs include wages and salaries, superannuation, and leave and other entitlements.

Source: ANAO, from NLC annual reports.

3.17 For 2014–15, the NLC’s travel agency provided a comprehensive report on the NLC’s expenditure by air travel, car hire and accommodation, and the destinations and hotels used by staff. From December 2016, the NLC has requested the report to be provided monthly. This report, and improved internal budget reporting, allows the NLC executive to analyse travel costs and consider if they are providing a good return to the council. Further reduction in travel costs may be possible, for example, through greater use of the video conferencing facilities.

Fleet management

3.18 The NLC owns and manages a fleet of some 100 vehicles that includes quad bikes, four wheel drive vehicles and sedans. Issues with the road worthiness and safety of the fleet and NLC’s fleet management procedures have been reported since 2011–1249, but remain outstanding as at March 2017 (referenced in Chapter 4).

Human resource management

3.19 Staff in the NLC’s Human Resource (HR) Management team have been primarily engaged in processing paper-based payroll functions—manually calculating wages and salaries, leave entitlements and various allowances—with little capacity for other HR functions. Managers largely worked independently to recruit staff and to manage performance, and there was little by way of a framework for staff training and development. A new HR manager, appointed in December 2016, is tasked with reforming the NLC’s HR functions.

3.20 For the purpose of this audit, the new HR manager provided an overview of actions, as at 31 January 2017, to be implemented through the year. Two ‘urgent’ actions are the: implementation (commenced) of a new payroll and human resource management system, scheduled to ‘go live’ on 1 July (allowing HR staff to move away from processing functions); and finalisation of a new Enterprise Agreement (staff are employed under the NLC Enterprise Agreement 2011, which nominally expired in June 2014).

3.21 Actions with a ‘high’ priority include: a review of remuneration and job classifications (to align with the new Enterprise Agreement); an update of all HR policies and procedures, including all aspects of performance, performance management and staff development (HR policies and procedures are in a manual, the Northern Land Council Human Resource Manual, approved 14 April 2009, and are out of date); and design of a leadership development program. Actions rated as a ‘medium’ priority include an overhaul of the induction process for new staff to the NLC. To implement these actions, the HR manager is meeting with senior managers and staff, to engage them in the new processes.

Record keeping and document management

3.22 The NLC maintains an electronic document management system (HP-TRIM50) that has been poorly utilised, with the organisation relying heavily on paper based files (maintaining a contract with an external provider for the off-site storage of these files), and in breach of the Australian Government Digital Transition Policy.51 The sheer volume of paper files created by the NLC and the requirement to scan, log and index the files and subsequently transport them off-site, was resource intensive and put record keeping at risk.

3.23 In October 2016, the NLC appointed a new information management coordinator tasked with improving all aspects of the NLC’s record keeping and document management. Activities to January 2017 included: a presentation in November 2016 to senior NLC staff on all aspects of records management; a request to the National Archives to review the NLC’s Check-up Digital assessment (with the NLC assessed as level 1 on all measures52); a review and redraft of the NLC’s records keeping policies and procedures; and re-negotiation of the off-site storage contract and clearing the backlog of paper files throughout the office.

3.24 An upgrade of the NLC’s electronic document management system is underway, scheduled to be implemented in May 2017. The initiative will upgrade the version (from version 7 to version 9.1) of the HP-TRIM system currently used by the NLC (that is outdated and no longer supported by the developer) and provide a massive increase in the system’s file storage capacity. The NLC advised that the new version is compliant with the National Archives of Australia standard for the digitalisation of records (VERS: the Victorian Electronic Records Strategy).

3.25 Advice from the NLC’s information management coordinator as at 1 March 2017 was that all managers were engaged and committed to using TRIM. The NLC has employed an accredited TRIM administrator for some five years, but the position was never properly utilised given the reliance on paper based documents. Going forward, the NLC could consider developing a quality assurance process to ensure that staff are compliant with the NLC’s business rules and protocols for electronic filing.

Internal policies

3.26 The NLC had not maintained a central register of its internal policies, or a process to review and update them. As at October 2016, of 44 policy documents provided by the NLC and reviewed by the ANAO, only five were current (that is, the policy had been reviewed and updated as required, and any changes had been approved).

3.27 As at 1 March 2017, policy documents were being filed in TRIM with any copies on share drives deleted. The NLC then had 49 policy documents in the TRIM file, with permissions attached to the electronic files to restrict edit rights and to track when the policy is accessed. The NLC also developed a standard template for all policies, with all existing policies transferred to the template format.

3.28 As at April 2017, the NLC has established a policy and procedures register recording 87 documents and their status (for example, approved or due for revision) with version control. Of the 87 documents shown on the register as at 19 April, 30 documents had been reviewed, updated and approved, with 16 ready for review.

Internal committees

Work Health and Safety Committee

3.29 The NLC has a Work Health and Safety (WHS) Committee of nine members convened under the authority of the CEO. The WHS Committee is governed by a Charter (approved by the Committee in April 2015) that outlines the functions and membership of the committee.