Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Effectiveness of the Department of Health and Aged Care’s Performance Management of Primary Health Networks

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Primary Health Networks (PHNs) are a delivery model for primary health care with the main objectives of: improving the effectiveness and efficiency of health services, particularly for those at risk of poor health outcomes; improving the coordination of health services; and increasing access and quality support for people.

- The Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) is responsible for administering PHN grant agreements, including monitoring compliance and the performance of PHNs, and supporting PHNs to improve.

Key facts

- PHNs were established on 1 July 2015, replacing Medicare Locals.

- There are 29 PHN providers which are responsible for 31 PHN regions across Australia.

- Populations of PHN regions range from 64,000 to 1.7 million people.

What did we find?

- Health has been partly effective in its performance management of PHNs.

- Health has established largely fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model.

- Health’s performance measurement and reporting arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model are partly fit-for-purpose.

- Health has not demonstrated that the PHN delivery model is achieving its objectives.

What did we recommend?

- There were eight recommendations relating to: ensuring PHN compliance with grant agreement requirements; improved PHN performance measures; PHN data assurance; improved PHN performance reporting; IT systems for PHN monitoring and reporting; and evaluation of the PHN delivery model.

- Health agreed to seven recommendations and agreed in principle to one recommendation.

$11.6bn

grant commitments to fund PHNs from 2015–16 to 2022–23.

132

different PHN performance measures in grant agreements and a performance framework.

3

annual reports on PHN delivery model performance produced since 2015–16.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Primary Health Networks (PHNs) were established by the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) on 1 July 2015 as a delivery model for primary health care. PHNs have two key objectives: improving the efficiency and effectiveness of health services for people, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes; and improving the coordination of health services and increasing access and quality support for people. 1

2. PHNs are non-government organisations funded through Australian Government grants. PHNs work across seven priority health areas comprising mental health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, population health, the health workforce, digital health, aged care, and alcohol and other drug services.

3. Health awards and manages grant agreements with the PHNs and is responsible for: the provision of guidance materials; facilitating regular communications and information sharing with PHNs; provision of data to support PHN needs assessments; monitoring the compliance and performance of PHNs; and supporting PHNs to improve.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Since the establishment of PHNs in 2015–16, Health has committed $11.6 billion to PHNs in grants funding. The commissioned services and activities of PHNs contributed to seven programs across three outcomes in Health’s 2022–23 Corporate Plan. The audit was identified by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit as an audit priority of the Parliament in 2021–22 and 2022–23.

5. Auditor General Report No. 9 of 2019–20 National Ice Action Strategy Rollout examined the expansion of alcohol and other drug treatment services through PHNs. Health agreed with the ANAO’s recommendation to ‘finalise the PHN Quality and Assurance Framework, with appropriate actions to assess whether PHNs are operating appropriately across the commissioning cycle’.

6. The audit aims to provide assurance to the Parliament that Health is appropriately monitoring compliance and performance of individual PHNs, as well as the overall performance of the PHN delivery model.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The purpose of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Aged Care’s performance management of Primary Health Networks.

8. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO examined:

- Has Health established fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model?

- Has Health established fit-for-purpose program performance measurement and reporting arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model?

- Has Health effectively evaluated the PHN delivery model to demonstrate that it is meeting its objectives?

Conclusion

9. The Department of Health and Aged Care has been partly effective in its performance management of Primary Health Networks.

10. Health has established largely fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model, although these arrangements were first established in 2021, almost six years after the implementation of the PHN delivery model. As at December 2023, there is a compliance and assurance framework comprised of a strategy, risk management plan, requirements in grant agreements, schedule of assurance activities, clear roles and responsibilities and oversight arrangements. Risks are identified and assurance activities are planned over individual PHNs and the delivery model as a whole. However, the link between identified risks and assurance planning is unclear, and some planned activities are not undertaken. Assurance is also weakened by record keeping practices and a lack of public transparency.

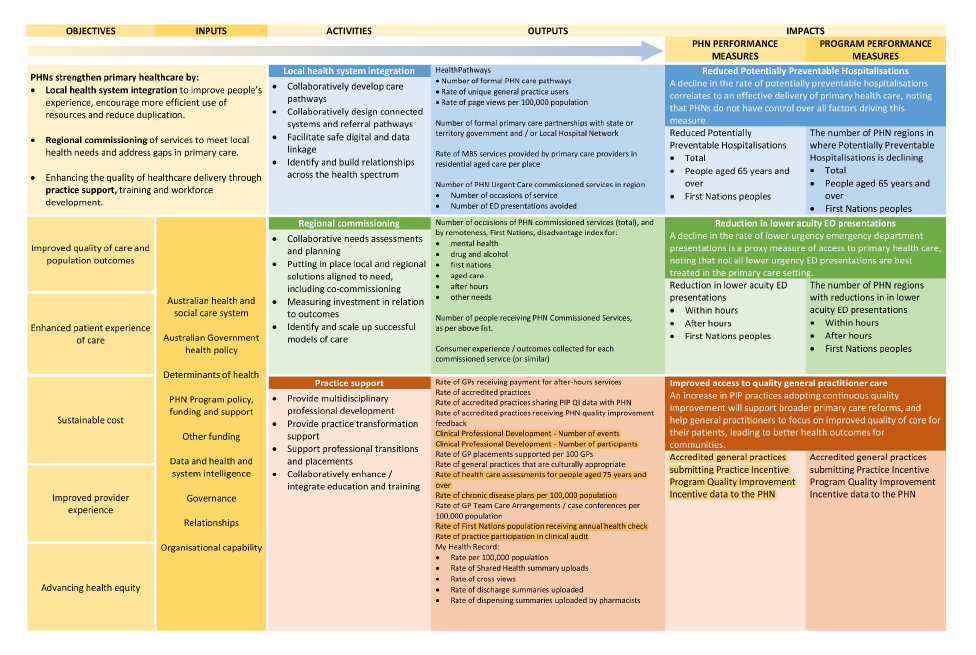

11. Health’s performance measurement and reporting arrangements for PHNs are partly fit-for-purpose. There is a PHN program logic to inform the development of outcomes-oriented performance measures, however it lacks clarity. There are a number of performance measures, however many assess PHNs’ compliance with grant agreements rather than providing information about the achievement of outputs and outcomes. The performance measures are largely aligned to Australian Government guidance for performance measurement, except that there are weaknesses in relation to relevance and data assurance. Public performance reporting is not timely or informative about overall PHN delivery model performance, and does not include information about individual PHN performance. IT systems for PHN performance reporting are partly fit-for-purpose.

12. Health has not demonstrated that the PHN delivery model is achieving its objectives. Health had no evaluation plans for the PHN delivery model after 2018. Health has not conducted a comprehensive delivery model evaluation. A 2018 early implementation evaluation was inconclusive about the achievement of objectives at that early stage in the delivery model’s implementation. A lack of baseline and relevant performance data impedes understanding of whether the delivery model has met its objectives.

Supporting findings

Assurance arrangements

13. The PHN delivery model was first implemented in 2015 and lacked an assurance framework until 2021, although specific guidance and tools to support assurance activity have been in place since 2016. An assurance strategy and schedule were established in 2022 and a risk management plan in 2023. The assurance framework establishes responsibilities for assurance activities including audits of individual PHNs. There are several oversight bodies, although an operational working group was disbanded in 2022. Grant agreements with PHNs appropriately establish governance, acquittal and performance reporting requirements. Health has not complied with Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines requirements to publish on GrantConnect approximately $10 billion in grants awarded to PHNs. (See paragraphs 2.1 to 2.15)

14. Health established an assurance plan for individual PHNs in 2022, which includes activities under three ‘lines of assurance’. Health’s assurance schedule does not include activities to monitor compliance with grant agreement requirements relating to the publication of needs assessments and activity work plans. Health took no action in response to PHN non-compliance with grant agreement requirements to provide financial information for a 2020 review of operational expenditure. Line one assurance activities (environmental scans, PHN risk assessments and assessments of PHN milestone reporting under grant agreements) were not always completed as planned or are difficult to assess due to poor record-keeping. Line two assurance activities (including assessment of PHN performance reporting and reviews by oversight bodies) were largely undertaken as planned. Line three assurance activities (risk-based audits of PHNs) were undertaken as planned. Health tracks PHNs’ implementation of recommendations from audits. The PHN Assurance Framework states that it takes a risk-based approach to conducting assurance, however risk assessments of PHNs are not undertaken as planned. (See paragraphs 2.16 to 2.26)

15. Health assesses risks and ‘hot issues’ for the PHN delivery model as a whole. Governance bodies have oversight of PHN risks, however consideration of risk by governance bodies has not been consistent with Health’s assurance planning and the terms of reference for these bodies. Health plans assurance activities over the delivery model as a whole, which are set out in an Assurance Framework or Schedule, however it is unclear how risk assessments inform assurance plans. The planned activities to provide assurance over the PHN delivery model have been partly carried out. In 2022–23 the Program Board did not meet as frequently as required. Six management reviews have been undertaken since 2018, including one in 2022–23. Health tracks its implementation of recommendations from these management reviews and assesses 76 per cent of agreed recommendations to have been implemented as at July 2023, with some 2018 recommendations related to performance monitoring still outstanding. Planned reviews of the PHN Assurance Framework and the Program Performance and Quality Framework in 2022–23 were not completed. (See paragraphs 2.27 to 2.35)

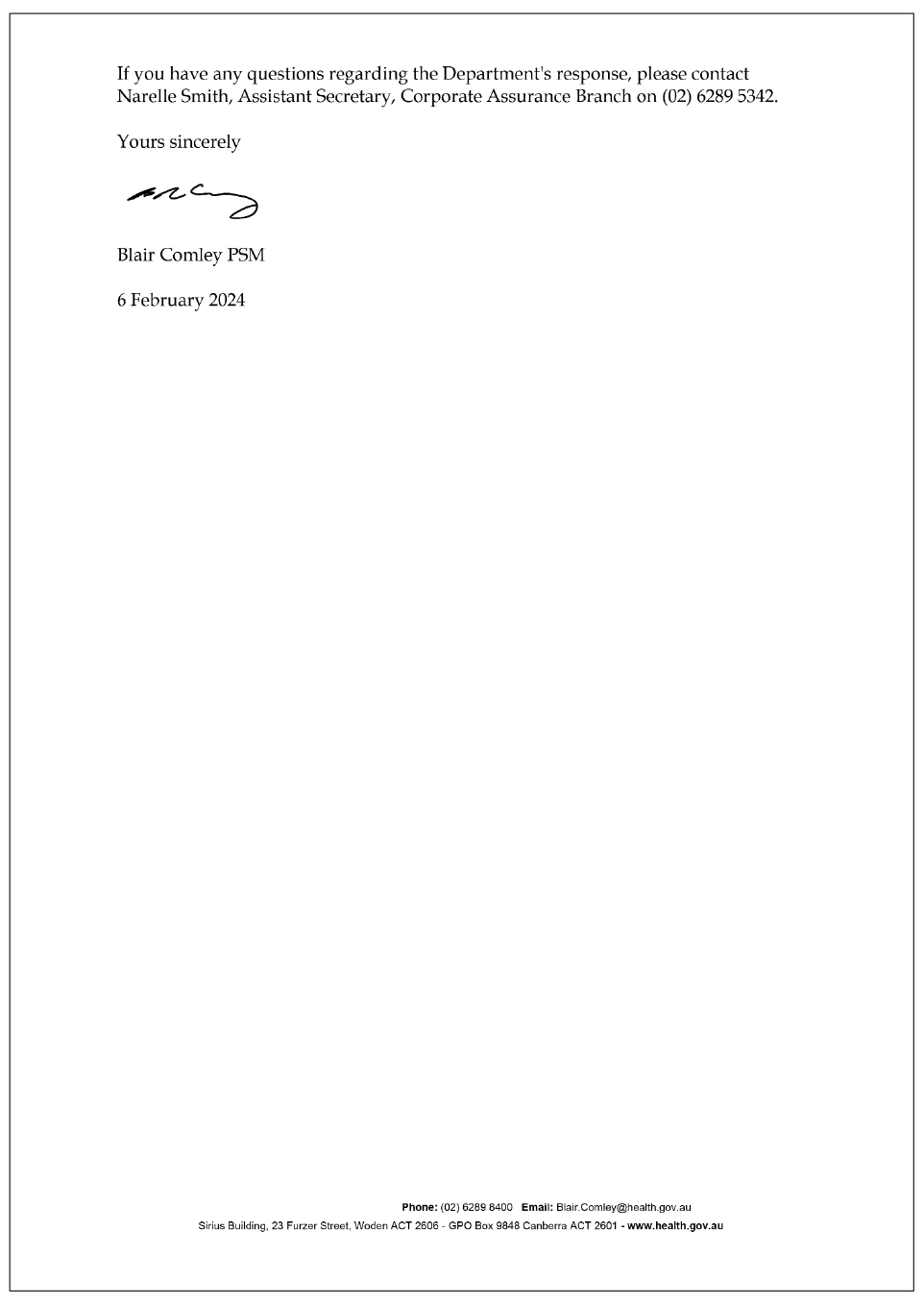

Performance reporting

16. Health established a program logic for the PHN delivery model in 2015, which was revised in 2018 and 2023. The 2018 program logic contains most of the expected elements of a program logic and provides information about how the PHN delivery model will achieve outcomes. The 2023 program logic introduces new objectives for the PHN delivery model, lacks clarity and is not aligned with guidance on developing program logics. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.9)

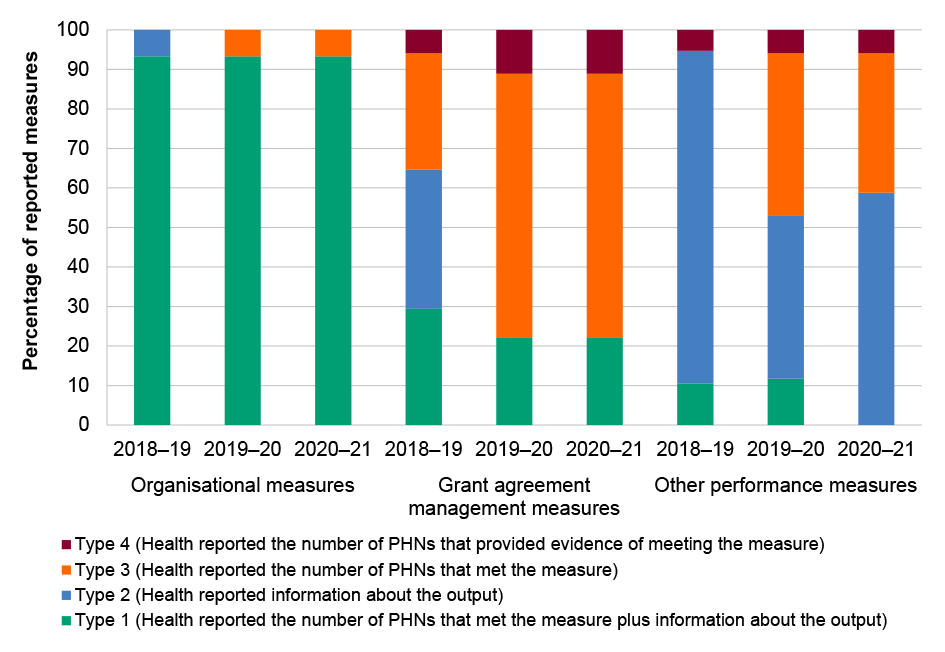

17. With the exception of measures related to the mental health priority area, the majority of performance measures included in PHN grant agreements check compliance with grant agreement reporting and other requirements, and do not assess the quality of outputs or the achievement of outcomes. Performance measures contained in mental health grant agreements are useful and support the adoption of an ‘outcomes orientation’, as recommended by the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines. In addition to measures in grant agreements, there is a performance framework which sets out 39 additional PHN ‘performance’ measures and 15 ‘organisational’ measures. These measures are used to monitor individual PHNs’ performance and, when aggregated, to conclude on the performance of the delivery model as a whole. Of the 39 performance measures, 20 measures are assessing something other than compliance with grant agreement requirements. These measures provide a basis for assessment over time; represent a mix of qualitative, quantitative, effectiveness and output measures; and mainly have targets. However, the relevance to stated PHN delivery model objectives is sometimes unclear, and there is a reliance on unverified PHN-supplied data for some measures. Health planned to improve PHN performance measures by July 2023, however this was delayed to June 2024. (See paragraphs 3.11 to 3.30)

18. Health’s PHN performance reporting is not timely, complete or consistently useful. A publicly available PHN annual report has been produced for three of the five years that the PHN delivery model has been operational and an annual report has been required. As at December 2023 there is no performance information publicly available about 2021–22 or 2022–23. Annual reports have been published years after the time period to which they apply. Health does not report against all the measures it has established, and published reports do not include analysis of financial information, the efficiency of PHNs, comparative analysis across PHNs or information on individual PHN performance. Some measures rely on secondary data that is unavailable. Annual reports partly rely on PHN self-reported performance information that is not always provided. (See paragraphs 3.31 to 3.54)

19. Health’s IT systems for managing PHN performance reporting are not fully fit-for-purpose. A system was developed in 2019 called the Primary Health Networks Program Electronic Reporting System (PPERS). Health has a range of guidance to support PPERS users. PPERS has limited capability to validate data inputs, analyse data and generate compliance and performance reporting. (See paragraphs 3.55 to 3.61)

Evaluation

20. A fit-for-purpose evaluation plan for the PHN delivery model was developed in 2015, which planned for evaluation activities up to December 2017. Despite a departmental evaluation strategy which indicates the importance of ongoing program monitoring and evaluation for new and high value policies or programs such as the PHN delivery model, there was no evaluation plan for the PHN delivery model after December 2017. A 2018 evaluation focused on the early implementation of the PHN delivery model. The PHN delivery model has not been comprehensively evaluated to determine whether it is meeting its objectives. There have been 23 evaluations of pilot programs and time limited grants provided through PHNs, however Health has not undertaken a consolidated review of findings from these evaluations to reach a conclusion about the effectiveness of the overall delivery model. (See paragraphs 4.1 to 4.9)

21. An early implementation evaluation reported in 2018 was inconclusive about whether the PHN delivery model was achieving its objectives but stated there were early indications of progress towards achieving objectives. Although there has been some improvement between 2018–19 and 2020–21 in PHNs’ average performance against some measures, no baseline data for these measures and the lack of relevant performance measures means that it is not possible to conclude if the PHN delivery model has met its objectives. (See paragraphs 4.12 to 4.17)

Recommendations

22. This report makes eight recommendations to Health.

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.24

The Department of Health and Aged Care ensure that PHNs fully comply with transparency and accountability requirements established in grant agreements, including requirements to participate in and provide data and information for the purposes of evaluation.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.25

The Department of Health and Aged Care establish performance measures that are clearly aligned to the Primary Health Networks’ and delivery model’s objectives.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.28

Where there is a reliance on Primary Health Network-supplied data, the Department of Health and Aged Care establish a risk-based methodology for obtaining assurance over the data.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.35

The Department of Health and Aged Care report on Primary Health Network performance as soon as practicable following the year to which the majority of the performance information relates.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.47

The Department of Health and Aged Care publish individual PHNs’ performance data and analysis in annual reports.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.52

The Department of Health and Aged Care publicly report on performance measures:

- in compliance with the Primary Health Network performance framework by reporting all performance measures; and

- in a way that is consistent with the intended purpose of conveying information about performance in addition to compliance with grant agreement requirements.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.59

The Department of Health and Aged Care implement a fit-for-purpose IT system for administering Primary Health Networks that supports the accurate capture and reporting of compliance and performance information.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed in principle.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.10

The Department of Health and Aged Care:

- develop an evaluation plan for the Primary Health Network delivery model; and

- evaluate the Primary Health Network delivery model to determine whether it is achieving its objectives.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

23. The proposed audit report was provided to Health. Health’s summary response to the audit is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

The Department of Health and Aged Care (the Department) welcomes the findings in this report and accepts the majority of recommendations. The Department is committed to implementing the recommendations and is taking steps to address the areas identified for improvement.

It is pleasing to note that compliance and assurance arrangements for the Primary Health Network (PHN) Program are fit for purpose. The audit identified opportunities to improve performance measurement and reporting for the PHN Program. These findings build on work already underway with PHNs through the Governance of PHN reporting framework, to redesign the Performance and Reporting Framework to include outcomes focused performance measures that align to the PHN delivery model objectives.

The Department is committed to demonstrating the performance of the PHN Program and will evaluate the PHN delivery model. The Department agrees in principle to recommendation seven noting investment in a bespoke system will be complex and will require funding decisions by Government.

The Department appreciates the report’s recognition that the Department is continuously engaging and consulting with its partners and key stakeholders to improve the effectiveness and operation of the PHN Program, and will continue this approach in developing and implementing our response.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Grants

1. Background

Introduction

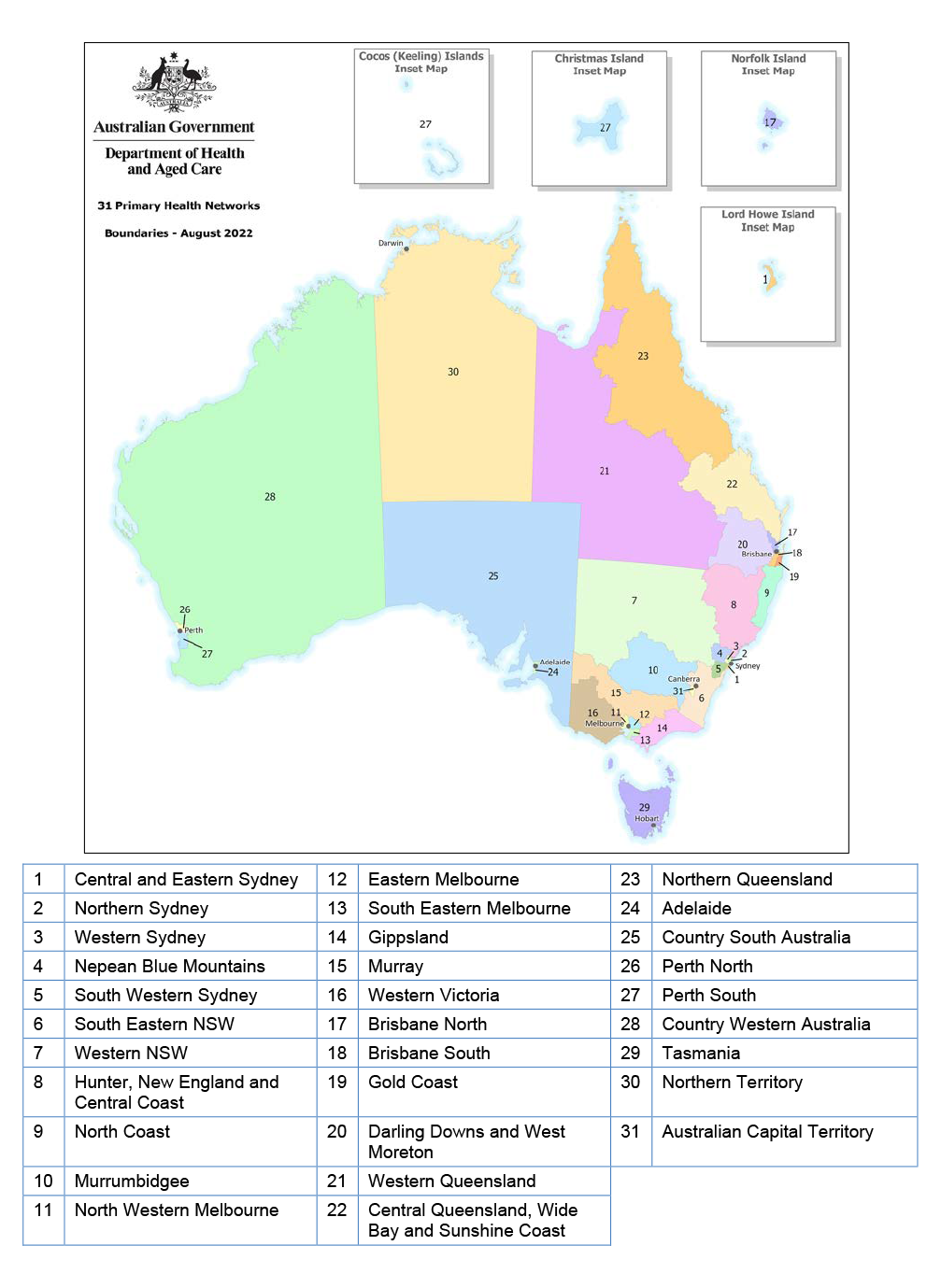

1.1 Primary Health Networks (PHNs) were established by the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) on 1 July 2015 as a delivery model for primary health care.2 There are 31 PHNs across all states and territories in Australia. Each PHN is responsible for the ongoing assessment of health needs in the PHN region, supporting health services and stakeholders, and commissioning and integrating health services at the local level 3, to ensure that people can receive ‘the right care, in the right place, at the right time’.4 PHNs have two key objectives:

- improving the efficiency and effectiveness of health services for people, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes; and

- improving the coordination of health services and increasing access and quality support for people.5

1.2 PHNs work across seven priority health areas comprising mental health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, population health, the health workforce, digital health, aged care, and alcohol and other drug services. PHNs contributed to seven programs in Health’s 2022–23 Corporate Plan.6

1.3 Health awards and manages grant funding agreements with the PHNs and is responsible for:

- the provision of guidance materials;

- facilitating regular communications and information sharing with PHNs;

- provision of data to support PHN needs assessments; and

- monitoring the compliance and performance of PHNs and supporting PHNs to improve.7

Funding of Primary Health Networks

1.4 PHNs are non-government organisations funded through Australian Government grants. PHNs are registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission.

1.5 Health provides four streams of funding to PHNs: operational funding (for the administration, governance and core functions of PHNs); flexible funding (for PHN priority areas); program funding (for programs previously managed by Medicare Locals (see paragraph 1.8) which remained in scope for PHNs after Medicare Locals were abolished); and innovation and incentive funding (for new models of primary health care delivery, that may be introduced across PHNs if successful). The amount of funding provided to each PHN is dependent on the population size of the PHN region, rurality and socio-economic characteristics, among other factors.

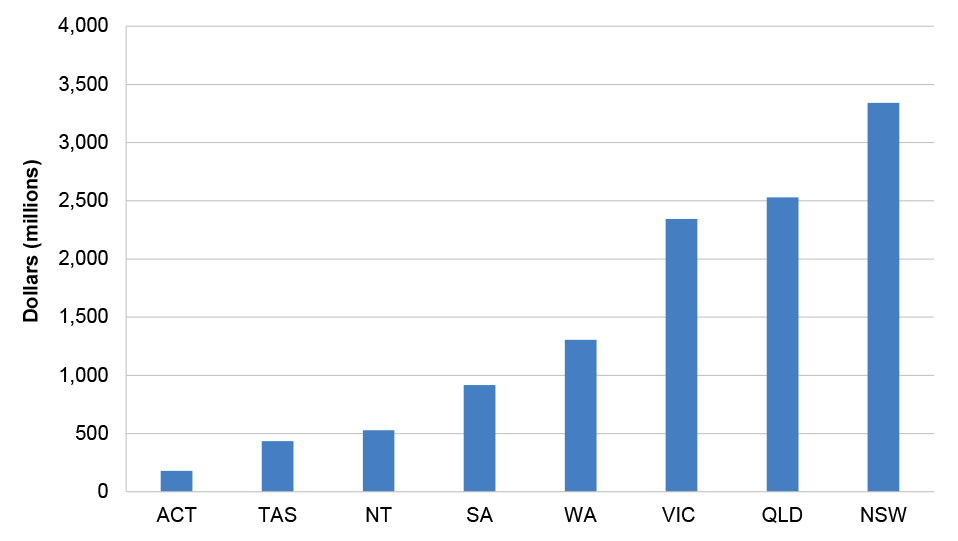

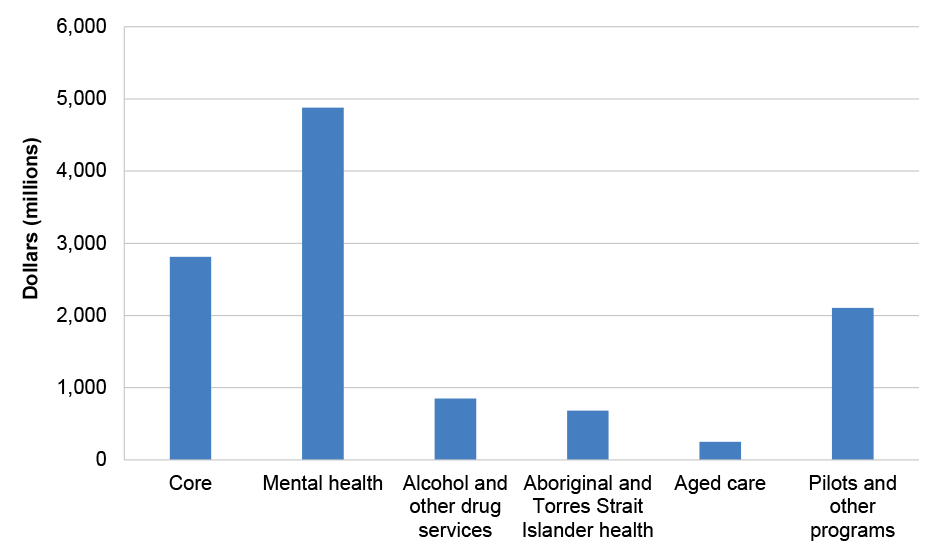

1.6 Between 2015–16 and 2023–24, $11.576 billion in grant funding commitments were made to PHNs (Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2).8 Of the total, $2.814 billion was committed to core funding agreements to fund PHN governance, operations, commissioning and coordinating activities, and $6.407 billion was committed to three of the seven PHN priority areas ($4.9 billion to mental health, $848 million for alcohol and other drugs and $682 million for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health). There was also $2.104 billion committed to PHNs for various pilot and other specific programs. Separate expenditure on the population health, health workforce and digital health priority areas cannot be separately quantified due to the structure of Health’s financial information. Appendix 3 shows grant commitments for each PHN.

Figure 1.1: Grant commitments to PHNs by state and territory, 2015–16 to 2023–24 (as at August 2023)

Source: ANAO analysis of Health’s master financial spreadsheet, as at August 2023.

Figure 1.2: Grant commitments to PHNs by core funding and priority area, 2015–16 to 2023–24 (as at August 2023)

Note: Pilots and other programs comprise: a range of targeted programs in addition to funding for the Community Health and Hospitals Program; after hours support; the Commonwealth Psychosocial Support Program; continuity of support; mental health – bushfire support; National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement and Bilateral PHN Program; National Psychosocial Support measure; Partners in Recovery, and urgent care clinics.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health’s master financial spreadsheet, as at August 2023.

1.7 Commonwealth grants provided to PHNs are subject to the requirements of the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines, issued by the Minister for Finance under section 105C of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. 9

Establishment of Primary Health Networks

1.8 Between 2011 and 2015, ‘Medicare Locals’ fulfilled a similar function to PHNs. A total of 61 Medicare Locals were created in three tranches in July 2011, January 2012 and July 2012 in response to the 2011 National Health Reform Agreement.10 Medicare Locals were created to identify the gaps in primary health care and improve service delivery at a local level.

1.9 In 2013 the Minister for Health commissioned Professor John Horvath AO to conduct a review into Medicare Locals, including all aspects of their structure, operation and functions. The Minister for Health stated that the purpose of the review was ‘reducing waste and spending on administration and bureaucracy, so that greater investment can be made in services that directly benefit patients and support health professionals who deliver those services to patients’.11 The review’s March 2014 report found that:

- the name ‘Medicare Local’ was confusing;

- general practitioners were not appropriately involved in Medicare Locals;

- a number of Medicare Locals were not fulfilling their intended role of integrating care for patients, who continued to experience ‘fragmented’ health care;

- there was variability between Medicare Locals in expenditure on administration, levels of funds allocated to frontline services, and accounting practices, and inconsistencies between planned and actual budgets;

- there was a lack of clarity in what Medicare Locals were trying to achieve, variability in scope and delivery and inconsistent outcomes;

- reporting requirements were burdensome for Medicare Locals; and

- performance measures were input and process driven rather than outcome focused.

1.10 The Medicare Local review made 10 recommendations, including that a network of ‘Primary Health Organisations’ (PHOs) be established through ‘contestable’ processes. The tenth recommendation was that ‘PHO performance indicators should reflect outcomes that are aligned with national priorities and contribute to a broader primary health care data strategy’.

1.11 In April 2014 the Minister for Health accepted the review’s recommendations. Health provided the Minister with two options for the establishment of PHOs: a new policy proposal outlining options for establishing PHOs by July 2016 (Approach 1), or providing funding in the May 2014 Budget to ‘fast track’ PHO establishment by 1 July 2015 (Approach 2). Health explained that Approach 1 had the advantage of consideration by Cabinet and the sector through consultation, a policy development process and the commissioning of design expertise, facilitating a ‘robust and viable PHO model’. Approach 2 had the advantage of reducing uncertainty for the sector. The Minister for Health chose Approach 2. The 2014–15 Budget indicated that PHNs would replace Medicare Locals on 1 July 2015 and cease Commonwealth funding to Medicare Locals.

1.12 Twenty nine providers received Australian Government grants on 1 June 2015 to establish 31 PHNs.12 PHNs were established to be closely aligned with state and territory Local Hospital Networks.13 PHNs represent populations ranging from approximately 64,000 people in Western Queensland to around 1.7 million people in North Western Melbourne.

Figure 1.3: Primary Health Network boundaries, 2022

Source: Health.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.13 Since the establishment of PHNs in 2015–16, Health has committed $11.6 billion to PHNs in grants funding. The commissioned services and activities of PHNs contributed to seven programs across three outcomes in Health’s 2022–23 Corporate Plan. The audit was identified by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit as an audit priority of the Parliament in 2021–22 and 2022–23.

1.14 Auditor General Report No. 9 of 2019–20 National Ice Action Strategy Rollout examined the expansion of alcohol and other drug treatment services through PHNs. Health agreed with the ANAO’s recommendation to ‘finalise the PHN Quality and Assurance Framework, with appropriate actions to assess whether PHNs are operating appropriately across the commissioning cycle’.

1.15 The audit aims to provide assurance to the Parliament that Health is appropriately monitoring compliance and performance of individual PHNs, as well as the overall performance of the PHN delivery model.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The purpose of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Aged Care’s performance management of Primary Health Networks.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO examined:

- Has Health established fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance arrangements for the PHNs and the PHN delivery model?

- Has Health established fit-for-purpose program performance measurement and reporting arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model?

- Has Health effectively evaluated the PHN delivery model to demonstrate that it is meeting its objectives?

Audit methodology

1.18 The methodology involved:

- examining Health records, including performance data and reporting;

- high-level examination of relevant record management systems;

- meetings with PHNs;

- meetings with Health personnel; and

- submissions to the audit from external stakeholders (31 submissions were received from individuals, primary health networks, industry groups, professional associations and health services providers).

1.19 Australian Government entities largely give the ANAO electronic access to records by consent, in a form useful for audit purposes. In April 2022 the Department of Health and Aged Care advised the ANAO that it would not voluntarily provide certain information requested by the ANAO due to concerns about its obligations under the Privacy Act 1988, secrecy provisions in Health portfolio legislation, confidentiality provisions in contracts and the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013. For the purposes of this audit, the Auditor-General therefore exercised powers under section 33 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 to enable authorised ANAO officers to attend premises, and examine and take copies of documents. Health facilitated authorised officers attending the Health’s premises to examine and copy documents, however the requirement was extended by Health to all documents, including those that did not relate to Health’s obligations under legislation. Health advised that this type of information largely was not segregated in Health’s record-keeping systems and Health could not be certain, in providing documents through electronic means, that documents containing this type of information were excluded. To provide comfort to the Secretary regarding Health’s obligations under portfolio legislation, on 9 August 2023 the Auditor-General issued the Secretary of Health with a notice to provide information and produce documents pursuant to section 32 of the Auditor-General Act 1997. Under this notice, Health agreed to provide the information and documents requested through electronic means.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $552,500.

1.21 The team members for this audit were Michael Commens, Lily Engelbrethsen, Katiloka Ata, Andrew Yam, Dale Todd, Alicia Vaughan, Elizabeth Robinson and Christine Chalmers.

2. Assurance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department for Health and Aged Care (Health) has established fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance arrangements for Primary Health Networks (PHNs) and the overall PHN delivery model.

Conclusion

Health has established largely fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance arrangements for PHNs and the PHN delivery model, although these arrangements were first established in 2021, almost six years after the implementation of the PHN delivery model. As at December 2023, there is a compliance and assurance framework comprised of a strategy, risk management plan, requirements in grant agreements, schedule of assurance activities, clear roles and responsibilities and oversight arrangements. Risks are identified and assurance activities are planned over individual PHNs and the delivery model as a whole. However, the link between identified risks and assurance planning is unclear, and some planned activities are not undertaken. Assurance is also weakened by record keeping practices and a lack of public transparency.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving compliance with a grant agreement requirement for PHNs to participate in reviews and evaluations through the provision of data and information. The ANAO suggested that Health strengthen its assurance arrangements over a grant agreement requirement for PHNs to publish needs assessments and activity work plans on websites.

2.1 PHNs receive Australian Government grant funding for their administration and operations under the core schedule to grant agreements. Funding for the priority health areas of mental health, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, population health, health workforce, digital health, aged care, and alcohol and other drug services is provided through different grant agreement schedules. Grant agreements may also cover specific projects.

2.2 The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) state that officials achieve value with relevant money in grants administration by ongoing monitoring and management and adopting an active risk identification and engagement approach.14 This requires fit-for-purpose planning of assurance processes, assurance over individual grantees against grant agreements, and assurance over the collective performance of the grants program.

Is there a fit-for-purpose compliance and assurance framework?

The PHN delivery model was first implemented in 2015 and lacked an assurance framework until 2021, although specific guidance and tools to support assurance activity have been in place since 2016. An assurance strategy and schedule were established in 2022 and a risk management plan in 2023. The assurance framework establishes responsibilities for assurance activities including audits of individual PHNs. There are several oversight bodies, although an operational working group was disbanded in 2022. Grant agreements with PHNs appropriately establish governance, acquittal and performance reporting requirements. Health has not complied with Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines requirements to publish on GrantConnect approximately $10 billion in grants awarded to PHNs.

Governance arrangements

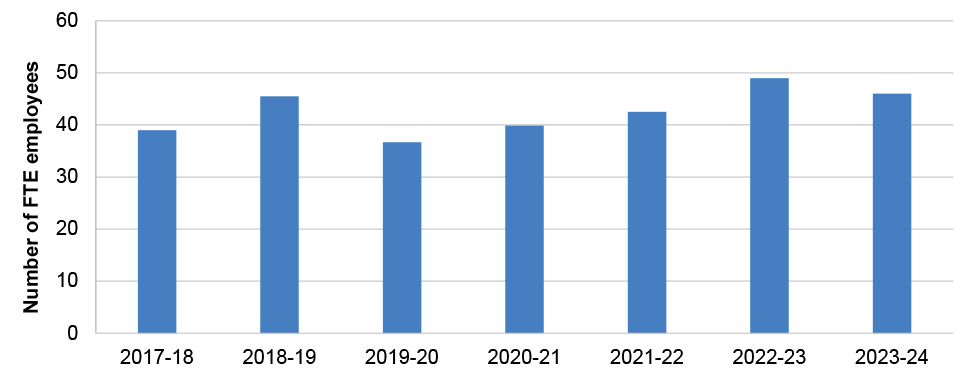

2.3 The PHN delivery model is managed by the Primary Health Networks Branch (PHN Branch) in the Primary Care Division of Health. Since 2017–18 the PHN Branch has had approximately 40 full time equivalent (FTE) employees (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Primary Health Networks Branch full-time equivalent (FTE), 2017–18 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of Health data.

2.4 In September 2023 the PHN Program Board (see paragraph 2.6) considered the growth of the PHN delivery model since its establishment, noting an annual funding increase from $0.8 billion per annum in 2015–16 to just under $2 billion in 2022–23. The Program Board further noted that PHNs originally involved four policy areas in Health and 14 funding streams, and in 2022–23 involved 43 policy areas across 10 Health divisions and 47 funding streams.

2.5 Between February 2018 and August 2023 Health commissioned external consultants to undertake assurance, performance management, and risk management design and delivery activities for the PHN delivery model. Health advised the ANAO that there were $4.3 million in outsourced advisory services for work specific to the PHN Program between February 2018 and August 2023. This figure does not include funding that was included as part of broader Departmental contracts.

2.6 Line management and oversight arrangements for the PHN delivery model include the following.

- Executive Committee15 — The role of Health’s Executive Committee is to provide strategic direction and leadership to ensure the achievement of outcomes documented in Health’s Corporate Plan and Portfolio Budget Statements. The Executive Committee met 145 times between 27 November 2018 and 5 December 2023, and discussed PHNs 10 times over this period. The most substantive examples are: in April 2019 the Executive Committee noted the status of recommendations from a July 2018 internal audit (see Appendix 4); in July 2019 the Executive Committee discussed the outsourcing of grant service delivery through PHNs; in November 2020 the Executive Committee discussed PHNs in the context of telehealth16; and in October and November 2022 the Executive Committee discussed a September 2022 presentation that had been made to the Program Assurance Committee (discussed at Table 2.1).

- Program Assurance Committee (PAC) — The PAC is a Health advisory body in place since 2018 that is intended to provide a strategic view of program design and delivery, guidance to assist business areas to improve program design and delivery, and assurance to the Secretary and Executive Committee on the effectiveness of program management. The PAC terms of reference state that it will meet approximately seven times each year. Membership of the PAC comprises Health senior executive officials, primarily at the Deputy Secretary and First Assistant Secretary level. The PAC discussed PHNs and programs involving PHNs five times between September 2018 and December 2023, including a September 2022 presentation discussed further at Table 2.1.

- PHN Program Board — Health established a PHN Program Board in July 2018 to ensure a ‘strategic and integrated’ approach to PHN delivery model management. The PHN Program Board was established to monitor PHN delivery model performance, promote best practice program management, oversee the delivery of priority projects and manage program risks. It is chaired by the Deputy Secretary Primary and Community Care Group and its membership comprises Health senior executive officials who have policy responsibility for PHN grant agreement schedules and program activities. The PHN Program Board is required to meet between two and four times each year. The Program Board met 15 times between 6 July 2018 and 23 March 2023 (three times annually, on average).

- PHN Operational Working Group — The first meeting of the PHN Operational Working Group took place in March 2018. Health established terms of reference in August 2019, which were last updated in December 2021. The terms of reference stated that the PHN Operational Working Group was the primary mechanism to progress the work program of the PHN Program Board. The PHN Operational Working Group was comprised of Health directors with responsibility for PHN grant agreement schedules. The terms of reference state that the group will meet every three weeks, or about 17 times each year. From 1 March 2018 to September 2022, the group met 41 times (once in 2018, five times in 2019, 17 times in 2020, 15 times in 2021 and three times in 2022), prior to being disbanded in September 2022.

- PHN Branch — The PHN Branch within the Primary Care Division has primary oversight of PHNs and the PHN delivery model, manages PHN grants, communicates with PHNs, undertakes reporting and undertakes assurance.

- Other groups and divisions within Health — Other policy areas within Health are involved in aspects of the management of PHNs. These include the Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Division, the Ageing and Aged Care Group, the Population Health Division and the First Nations Health Division. Responsibilities include policy decisions for relevant grant agreements, reviews of PHN deliverables after these are processed by the PHN Branch; and reporting on specific performance measures and engaging with PHNs on these measures.

2.7 Health advised the ANAO that the PHN Operational Working Group was replaced by an ‘informal’ committee of assistant secretaries that ‘meets as required to share information and collaborate on strategic priorities for the PHN Program’. Health developed a ‘PHN Service Offer’ in June – September 2023, which describes the roles and responsibilities relating to the PHN delivery model (including those set out in paragraph 2.6, except for the Executive Committee and PHN Operational Working Group, and including reference to a ‘PHN Program Assistant Secretary Committee’). The PHN Program Assistant Secretary Committee is described as Health’s ‘senior governance forum with oversight of program delivery, performance and assurance’.

Grant agreements with individual Primary Health Networks

2.8 In addition to the core grant agreements and priority activity schedules described in paragraph 2.1, grants are awarded to PHNs for specific projects, trials, commissioning of third-party service providers and other activities. Health maintains records of funding commitments and payments to PHNs, including a history of all funding allocations since 2015. Although Health maintains a consolidated record of funding commitments, it does not maintain consolidated information on grant award numbers (as would be listed on GrantConnect), and the types of grants awarded. When the ANAO requested this consolidated grant information from Health, Health was unable to provide it.

2.9 The CGRGs state that reliable and timely information on grants awarded is a precondition for public and parliamentary confidence in the quality and integrity of grants administration. The CGRGs require Commonwealth entities to publish individual grant awards within 21 days of the grant taking effect.17 Auditor-General report No. 31 of 2022–23 Administration of the Community Health and Hospitals Program identified non-compliance with mandatory GrantConnect reporting requirements and included a recommendation for Health to establish a quality assurance process to confirm and where necessary correct the accuracy of reporting on GrantConnect.

2.10 Health’s reporting on GrantConnect of PHN grants is inconsistent with Health’s records of funding commitments and payments to PHNs. As at May 2023 GrantConnect included 841 PHN grants valued at $2.4 billion. This compares with $11.6 billion in funding commitments and $10.3 billion in payments made to PHNs by Health as at August 2023. As information about each grant awarded to each PHN has not been reported accurately by Health on GrantConnect and is not maintained by Health in another consolidated form, the ANAO was unable to determine the total number of grants awarded, the number of grants awarded to each PHN and the types of selection processes followed in determining grants awarded to PHNs. The accurate reporting of grant awards on GrantConnect is a mandatory requirement of the CGRGs, which are legal requirements under finance law. Health advised the ANAO that it is aware of this issue and intends to correct GrantConnect reporting by May 2024.

2.11 The ANAO reviewed core grant agreements in detail for a targeted sample of six PHNs.18 Core grant agreements for the sampled PHNs appropriately established governance, acquittal and performance reporting requirements.

- Governance requirements — grant agreements for each of the six sampled PHNs included requirements for:

- maintaining appropriate governance structures, including a skills-based board, General Practitioner (GP)-led Clinical Councils and Community Advisory Committees;

- maintaining governance arrangements to appropriately manage conflicts and related party involvement;

- participating in and allowing access to premises, materials and documents, for the purpose of any audit as directed by Health;

- publishing key documents including needs assessments19 and activity work plans20 on PHN websites; and

- supporting the monitoring and evaluation of the PHN through the provision of documents and surveys when requested by Health.

- Acquittal and performance reporting requirements — grant agreements for each of the six sampled PHNs included requirements for:

- milestone reports21 to be submitted before payments are made, and which include annual needs assessments and annual activity work plans;

- annual performance reporting against the 2018 PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework (discussed further at paragraphs 3.19 to 3.21); and

- annual audited financial statements for core operations and activities, priority area activities, and pilots and other ad hoc projects (such as grants for mental health support for bushfire affected communities).

Assurance strategy, guidance and tools

2.12 Health first developed a documented strategy for assuring the performance of PHNs in 2021, five years after the PHN delivery model was implemented. The PHN Assurance Framework was developed in response to a recommendation from a 2018 internal audit which found that there were gaps in quality assurance processes. In 2021 Health engaged PwC to develop the assurance framework, which was to be operationalised from 2020–21 to 2023–24.

2.13 The PHN Assurance Framework states that it was developed to support the performance and operation of PHNs and provide greater assurance to the Australian Government over Health’s activities to ensure PHNs are operating appropriately, in accordance with their legal and financial obligations, and meeting objectives. The Assurance Framework states that it is designed to assure the performance of individual PHNs and the PHN delivery model as a whole, and that it takes a risk-based approach to conducting assurance over both. Assurance activities listed in the PHN Assurance Framework comprise: self-assessment checklists; desktop reviews; enquiries and walkthroughs; process reviews (including observation); deep dives and detailed reviews; risk based and random sampling; and independent assurance engagement.

2.14 The implementation of the PHN Assurance Framework is supported by two key documents developed in 2022 and 2023: an Assurance Strategy and a Risk Management Plan.

- PHN Assurance Strategy — This applies to 2022 to 2024. The PHN Assurance Strategy states that it will assist Health to identify key risks to the PHN delivery model, identify gaps in assurance and mitigation strategies, and target assurance activities to the areas of greatest risk. There is a timeline for the implementation of assurance activities.

- PHN Risk Management Plan — This was established in March 2023. It sets out the processes to identify, analyse, treat, monitor and manage risks and issues. Health maintains other guidance and templates to support risk owners and other officials to manage PHN risks, including a grant recipient risk tool for monitoring individual PHN risks.

2.15 Prior to and since the development of the 2021 PHN Assurance Framework and to support its implementation, Health has maintained guidance materials and tools for use by PHNs or Health officials tasked with assurance work. Forms of guidance materials have existed since 2016. Further development on materials was undertaken from 2019. Examples include the following.

- In 2019 Health commissioned KPMG to develop process maps for PHN grants management, reporting, assurance and compliance processes.

- In 2021 Health established guidance for the assessment of PHNs’ 12-month performance reports (discussed further at paragraphs 3.19 to 3.21) including an Assessment Process Guide; Compliance Checklist; Individual Performance Assessment template, PHN Program Electronic Reporting System ‘Indicator Guide’; and a ‘Performance Rubric’.22

- In 2021 and 2022 Health revised guidance for reviewing PHNs’ needs assessments and activity work plans, including a revised assessment template for the activity work plan.

Are assurance arrangements for individual Primary Health Networks fit-for-purpose?

Health established an assurance plan for individual PHNs in 2022, which includes activities under three ‘lines of assurance’. Health’s assurance schedule does not include activities to monitor compliance with grant agreement requirements relating to the publication of needs assessments and activity work plans. Health took no action in response to PHN non-compliance with grant agreement requirements to provide financial information for a 2020 review of operational expenditure. Line one assurance activities (environmental scans, PHN risk assessments and assessments of PHN milestone reporting under grant agreements) were not always completed as planned or are difficult to assess due to poor record keeping. Line two assurance activities (including assessment of PHN performance reporting and reviews by oversight bodies) were largely undertaken as planned. Line three assurance activities (risk-based audits of PHNs) were undertaken as planned. Health tracks PHNs’ implementation of recommendations from audits. The PHN Assurance Framework states that it takes a risk-based approach to conducting assurance, however risk assessments of PHNs are not undertaken as planned.

Assurance planning for individual Primary Health Networks

2.16 The PHN Risk Management Plan states that risks are identified and managed through day-to-day activities and policies, including annual individual PHN risk assessments (discussed at paragraph 2.18 and Table 2.1).

2.17 Separately to the annual individual PHN risk assessments, Health engaged PwC to undertake ‘baseline maturity assessments’ of the PHNs, with the final report provided to Health in April 2022.23 The objective was to evaluate each PHN’s effectiveness, efficiency and economy of operations; identify risks and issues that would not be picked up during business as usual assurance activities; and provide Health with confidence that individual PHNs are operating appropriately, in accordance with their legal and financial obligations. Overall baseline maturity risk assessments (which ranged from ‘very low’ to ‘very high’) were derived from a quantitative financial risk indicator24 and qualitative risk indicators. 25 The 31 PHNs were assessed as having an overall baseline maturity risk of ‘very low’ (2), ‘low’ (12), ‘medium’ (7) and ‘high’ (10). None were assessed as having a ‘very high’ overall risk. The baseline maturity assessments included recommendations relating to sharing best practice and implementing recommendations from previous PHN delivery model reviews, as well as the revision of both the qualitative and quantitative risk indicators. The baseline maturity assessment included some commentary on areas of improvement for individual PHNs but did not include recommendations for individual PHNs. The PHN Program Board agreed that from July 2024 Health will commence a second round of PHN maturity assessments, following a review of the baseline maturity assessment methodology (which is scheduled to commence in March 2024).

2.18 Annual individual PHN risk assessments are documented using a template that contains some of the same risk indicators captured in the baseline maturity assessments, including PHN issues management, governance and performance management. However, the results of annual PHN risk assessments are inconsistent with the baseline maturity assessment. For example, two PHNs in the ANAO’s sample of six PHNs were assessed as an overall low risk in the baseline maturity assessment but were assessed as high risk in the annual PHN risk assessment (last updated for one of the PHNs in September 2022).26 Health advised the ANAO that the baseline maturity risk assessments ‘utilised different criteria’ and had ‘lower tolerance levels’ than the annual PHN risk assessments.

2.19 Health first established a PHN Assurance Schedule for activities targeting the PHN delivery model and individual PHNs in 2022–23. The PHN Assurance Schedule outlines the assurance activities for the implementation of the PHN Assurance Framework. The one-page document sets out the timeframes (by month, over one year) for the achievement of milestones and assurance activities. ‘Next financial year’ activities are also summarised. The PHN Assurance Schedule categorises activities into three lines of assurance: first line (operational management), second line (oversight including risk management and compliance) and third line (internal audit).

2.20 The PHN Assurance Framework states that it takes a risk-based approach to conducting assurance. While the baseline maturity assessments have been used to inform the choice of PHNs to audit (a third line activity, see Table 2.1), there is no evidence that the annual PHN risk assessments or the baseline maturity assessments were used to inform the planning of Health’s first and second line assurance activities.

2.21 Grant agreements with PHNs require PHNs to publish annual needs assessments and activity work plans on PHN websites. Neither the Assurance Framework nor the Assurance Schedule includes compliance checks for these requirements. As at January 2024, out of 31 PHNs, the Northern Territory PHN website does not comply with relevant grant agreement requirements.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.22 Health could include checks of PHN websites in assurance planning to ensure that PHNs publish up to date needs assessments and activity work plans on websites. |

2.23 Grant agreements with PHNs state that PHNs are required to participate in and support evaluation including by providing financial and non-financial information and data to evaluators. A 2020 KPMG operational expenditure review (see Appendix 4), which was conducted in response to a recommendation of a 2018 evaluation, states that 26 per cent of PHNs did not respond to a survey seeking to quantify operational expenditure, and that other PHNs did not provide appropriate responses. The aim of the operational expenditure review was to identify the actual or ‘true’ operational expenditure of PHNs compared to what was reported, and identify unique and common cost drivers. As a consequence of PHN non-response, the review was unable to generalise findings across regional, remote and metropolitan regions, and comparative analysis included in the report was incomplete. Health advised the ANAO that it did not take any action in response to non-compliance with requirements to participate in the survey, including identifying which PHNs were non-compliant.

Recommendation no.1

2.24 The Department of Health and Aged Care ensure that PHNs fully comply with transparency and accountability requirements established in grant agreements, including requirements to participate in and provide data and information for the purposes of evaluation.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

2.25 The Department of Health and Aged Care requires Primary Health Networks (PHNs) to comply with the requirements of their grant agreements and will enhance existing assurance processes to further support compliance and follow-up where PHNs do not respond to requests for information.

Assurance activities over individual Primary Health Networks

2.26 The ANAO examined whether the individual PHN assurance activities planned for 2022–23 were undertaken in accordance with the line one, two and three activities listed in the PHN Assurance Schedule (see Table 2.1 and paragraph 2.19 for Health’s definition of the three lines).

Table 2.1: Assessment of Health’s implementation of individual PHN assurance activities against the PHN Assurance Schedule

|

Assurance category |

Planned assurance activity |

Completed? |

Analysis |

|

Line 1 — operational management |

Quarterly environmental scans |

■ |

Health did not undertake quarterly environmental scans in 2022–23. |

|

Line 1 — operational management |

Individual PHN risk assessments in August of each year |

■ |

The ANAO reviewed annual PHN provider risk assessments for the six PHNs included in the ANAO’s targeted sample (see paragraph 2.8). Risk assessments for five of six PHNs had not been updated in August 2023 as required. |

|

Line 1 — operational management |

Assessment of PHN milestone reporting (including needs assessments and activity work plans) |

Unable to fully assess |

The ANAO attempted to review Health’s assessment of PHN milestone reporting covering 2019–20 to 2021–22 for the six PHNs included in the ANAO’s targeted sample. There was evidence of submission and approval of milestones reports as required under grant agreements. The ANAO could see evidence of PHNs being required to submit multiple versions of needs assessments prior to approval from Health and Health approving activity work plans. For example, the ANAO observed that Health had identified incorrect funding allocations in a milestone report, requiring the PHN to resubmit. There was evidence of Health providing feedback to PHNs on other deficiencies in milestone reports. Information management standardsa and the CGRGsb require officials to maintain appropriate records. Although the ANAO found evidence that milestone reporting was being assessed, it was not possible to confirm whether this had been done appropriately due to difficulty in identifying the authoritative milestone documents (including the activity summaryc, budget summaryd and Health’s assessments of the activity work plan and budget), for each activity work plan in the ANAO’s targeted sample. This was due to inconsistent naming conventions, multiple versions of documents, inconsistent file types being used by PHNs (despite requirements for PHNs to submit reports in a standard file type) and document references in the PHN Program Electronic Reporting System (PPERS, see paragraph 3.55) linking to folders containing multiple copies of documents without appropriate version control. |

|

Line 2 — oversight |

Individual PHN performance assessments |

◆ |

PHNs are required to submit a 12-month performance report each year. Financial and non-financial performance information included in the 12-month report is to be assessed by Health and documented in its performance assessment for each PHN. The Assurance Schedule includes Health assessments of 12-month performance reporting for each PHN.e The ANAO reviewed annual performance assessments prepared by Health (and associated PPERS data extracts) for the six PHNs in the ANAO targeted sample for 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22.f Annual assessment reports were prepared by Health and completed in accordance with the Performance Rubric. Health’s performance assessments for each PHN in 2019–20 and 2020–21 included an assessment against 42 out of 54 performance measures (see paragraph 3.19). Health’s performance assessments in 2021–22 included an assessment against a reduced subset of 32 performance measures, as reporting requirements were reduced by Health.g All six sampled and examined PHNs were ‘on track’ or ‘progressing’ against each of four themes. In 2021–22, the number of indicators met ranged from 23 to 26 out of 32. Consistent with Health’s assessment guidance, Health’s draft performance assessments were provided to PHNs for comment, with PHN comments and Health’s response to the comments included in the final assessment reports. |

|

Line 2 — oversight |

Program reviews by the Program Assurance Committee and Audit and Risk Committee |

◆ |

A September 2022 ‘Health Check of the PHN Program’ conducted by Synergy (see Appendix 4) was noted by Health’s Audit and Risk Committee on 29 September 2022, largely consistent with the Assurance Schedule. Audit and Risk Committee papers do not include minutes on any discussion of findings, recommendations or underlying risks identified in the Synergy Health Check. The PHN delivery model was the subject of a scheduled review by the PAC on 15 September 2022. The PAC received updates on the implementation of the PHN Assurance Framework, compliance improvements, the ongoing development of the PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework and the revision of performance indicators. |

|

Line 2 — oversight |

PHN Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission self-assessments |

■ |

The Assurance Schedule includes requirements for Health to engage with PHNs around the completion of the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) self-assessment and checklist for conformance with ACNC governance standards. Health did not engage with PHNs on the completion of the ACNC self-assessment in accordance with the Assurance Schedule. |

|

Line 3 — Internal audit |

In June 2022, line three activities for 2022–23 comprised six commissioned audits of individual PHNs commencing or completed in 2022–23. |

◆ |

ANAO reviewed planning records for all six planned audits, draft and final reports for all six audits and final reports for two completed audits. All six audits were undertaken in accordance with Health’s PHN Assurance Schedule. Health’s choice of PHN to audit was based on the outcomes of baseline risk maturity assessments.h Five of six PHNs targeted for an audit were assessed as a high overall risk. One PHN was assessed as low overall risk but had below average qualitative assessments on governance, monitoring and reporting. The scope for all six audits included PHNs’ governance and decision-making processes; financial management, planning and reporting; organisational capacity and capability; and probity and commissioning practices. Health maintains a tracker for documenting the findings and implementation status of recommendations from PHN audits (see Appendix 5). |

Key: ◆ Largely or fully implemented as planned ▲ Partly implemented as planned ■ Not implemented

Note a: National Archives of Australia, Information Management Standard for Australian Government, available from https://www.naa.gov.au/information-management/standards/information-management-standard-australian-government [accessed 8 November 2023].

Note b: Department of Finance, Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines 2017, Finance, paragraph 12.6, p. 33.

Note c: The activity summary is a template report describing the various activities planned by PHNs and the alignment with assessed needs and government priorities. The summary includes planned expenditure and timelines for completion of each activity.

Note d: The budget summary has, for each priority area, the proposed expenditure and the anticipated variation between income and expenditure for the relevant activity.

Note e: The Performance Rubric contains three assessment standards: ‘On Track’ (‘PHN has met performance criteria for all indicators’), ‘Progressing’ (‘PHN has met performance criteria for half of the indicators and is working towards meeting the other indicators’) and ‘Initial’ (‘PHN has met performance criteria for one indicator’). Health assesses activities using a traffic light system where green is on track, amber is progressing, and red is not progressing.

Note f: The 2022–23 annual performance assessments were to be completed in December 2023.

Note g: Organisational capability indicators reported against in 2019–20 and 2020–21 were not required to be reported against in 2021–22.

Note h: North Queensland, Australian Capital Territory, South Eastern Melbourne, Adelaide, Northern Sydney and Northern Territory PHNs were subject to audits in 2022–23.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health documentation.

Are delivery model assurance arrangements fit-for-purpose?

Health assesses risks and ‘hot issues’ for the PHN delivery model as a whole. Governance bodies have oversight of PHN risks, however consideration of risk by governance bodies has not been consistent with Health’s assurance planning and the terms of reference for these bodies. Health plans assurance activities over the delivery model as a whole, which are set out in an Assurance Framework or Schedule, however it is unclear how risk assessments inform assurance plans. The planned activities to provide assurance over the PHN delivery model have been partly carried out. In 2022–23 the Program Board did not meet as frequently as required. Six management reviews have been undertaken since 2018, including one in 2022–23. Health tracks its implementation of recommendations from these management reviews and assesses 76 per cent of agreed recommendations to have been implemented as at July 2023, with some 2018 recommendations related to performance monitoring still outstanding. Planned reviews of the PHN Assurance Framework and the Program Performance and Quality Framework in 2022–23 were not completed.

Delivery model risk assessment

2.27 PHNs were established by Health on 1 July 2015 as a delivery model for primary health care. The PHN Risk Management Plan states that delivery model risks are identified and managed through an overarching delivery model risk register; a quarterly delivery model risk register review by PHN governance groups; and a quarterly review of risk by all program and policy areas. The ANAO did not review program and policy areas’ risk assessments as the focus of this performance audit was the management of the PHN delivery model, which is managed within the PHN Branch.

Delivery model risk register

2.28 Health maintains an overarching risk register for the PHN delivery model consistent with the Risk Management Plan. The ANAO reviewed risk registers, updated approximately every six months, covering the period October 2021 to September 2023. The September 2023 risk register documents eight risks (seven medium risks and one high risk relating to Health’s ability to manage the expansion of PHNs’ roles).

2.29 In the March 2023 and September 2023 risk registers, two moderate financial and fraud risks were accepted outside Health’s tolerance level, which is set at low for financial and fraud risks. Key controls for the fraud risk, such as audited financial statements and PHN internal controls, were described as fully effective. This is not consistent with analysis undertaken by the ANAO on financial reporting, or with financial governance and conflict of interest management findings and subsequent recommendations from PHN audits undertaken by Health (Appendix 5). The ANAO compared financial reporting in PHNs’ 12-month performance reports to audited financial statements required under grant agreements. For all six target sample PHNs, there were instances of 12-month performance reporting being inconsistent with the audited financial statements in 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22. Health advised that it undertakes analysis to better understand inconsistencies in financial reporting and that it has established a dedicated finance team to work directly with PHNs to improve the accuracy of financial reporting.

2.30 Since 2019–20 Health has maintained a ‘hot issues’ register, documenting a range of issues including the development of compliant grant opportunity guidelines and the accuracy of PHN financial reporting. Hot issues registers also include issues relating to individual PHNs’ leadership and governance.

Quarterly review of delivery model risk register by governance groups

2.31 The Program Board discussed ‘hot issues’ or the PHN risk register in eight of 15 meetings held between July 2018 and March 2023. Since March 2023, when the Risk Management Plan was implemented, the Program Board met in March and in September 2023. The risk register was reviewed in the March and September 2023 meetings.

2.32 The ANAO reviewed 41 PHN Operational Working Group meeting records covering the period 1 March 2018 to its final meeting on 21 September 2022. The group discussed ‘hot issues’ at 36 of 41 meetings, including all meetings held after 13 November 2019, and was scheduled to meet on 16 December 2021 to review the PHN risk register, however the meeting was cancelled.

Assurance planning and activities over the delivery model

Assurance planning

2.33 Updates to the delivery model risk register did not feed into the 2021 Assurance Framework and the 2022 Assurance Strategy, which have not been reviewed or amended since their establishment.

2.34 There are some inconsistencies between the PHN Assurance Framework and the Assurance Schedule regarding delivery model assurance activities. The PHN Assurance Framework sets out meetings of the Program Board, ‘deep dives’ and process reviews as delivery model assurance activities. The Assurance Schedule also sets out Program Board meetings. Thematic assurance activities or ‘deep dives’ as described in the PHN Assurance Framework were not included in the 2022–23 Assurance Schedule. The Assurance Schedule indicated that a revised PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework, as well as an annual review of the Assurance Framework, would be undertaken in July 2023. Health advised that completion of this work has been delayed until June 2024.

Assurance activities

2.35 The ANAO examined whether the delivery model assurance activities planned for 2022–23 were undertaken in accordance with the PHN Assurance Framework and PHN Assurance Schedule (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Assessment of Health’s implementation of PHN delivery model assurance activities

|

Planned assurance activity |

Completed? |

Analysis |

|

Meetings of the Program Board |

▲ |

The 2022–23 Assurance Schedule includes requirements to hold four meetings of the Program Board between July 2022 and June 2023. Health’s Program Board met three times between 1 July 2022 and 30 June 2023. ANAO analysis of Program Board meeting records between July 2018 and March 2023 found that it discussed findings and recommendations from thematic reviews and internal audits, including concerns with third party provider commissioning practices, PHN governance arrangements and data quality. For example, on 1 July 2022 the Program Board endorsed the Assurance Framework and Assurance Strategy, noted the baseline maturity assessment final report, and noted the maturity assessment ratings of individual PHNs. |

|

Deep dives and process reviews |

◆ |

Since 2018 Health has commissioned six thematic reviews and internal audits targeting PHN delivery model requirements and activities, one of which (a ‘health check’) was undertaken in 2022–23. Appendix 4 sets out the scope, key findings, and recommendations of delivery model reviews between July 2018 and December 2023, and Health’s assessment of implementation of recommendations as at July 2023 (as at December 2023, this was the last time implementation status was monitored). Health maintains a consolidated tracking spreadsheet to monitor the status of recommendations from delivery model assurance activities. The six thematic reviews made a total of 63 recommendations, of which 62 were agreed to by Health. Health assessed it had implemented 47 (76 per cent) of agreed recommendations as at July 2023. As at July 2023 the tracker indicated that four recommendations from the 2018 Evaluation of the PHN Program were still not complete. These relate to performance monitoring and PHN delivery model operations. Unimplemented recommendations from the 2020 Review of PHN Grants and Reporting also relate to performance management and performance data. |

|

Annual review of PHN Assurance Framework |

■ |

The Assurance Schedule indicated that an annual review of the Assurance Framework would be undertaken in July 2023. Health had not commenced this work as at December 2023. Health advised the ANAO that it is planning this review work and intends to include new programs introduced at the 2023–24 Budget. |

|

Revised Program Performance Quality Framework |

■ |

The Assurance Schedule indicated that a revised PHN Program Performance and Quality Framework was to be implemented from 1 July 2023. The revised due date, which was agreed by the Audit and Risk Committee, is 28 June 2024. |

Key: ◆ Largely or fully implemented as planned ▲ Partly implemented as planned ■ Not implemented

Source: ANAO analysis of Health documentation.

3. Performance measurement and reporting

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) has established fit-for-purpose performance measurement and reporting arrangements for the Primary Health Network (PHN) delivery model.

Conclusion

Health’s performance measurement and reporting arrangements for PHNs are partly fit-for-purpose. There is a PHN program logic to inform the development of outcomes-oriented performance measures, however it lacks clarity. There are a number of performance measures, however many assess PHNs’ compliance with grant agreements rather than providing information about the achievement of outputs and outcomes. The performance measures are largely aligned to Australian Government guidance for performance measurement, except that there are weaknesses in relation to relevance and data assurance. Public performance reporting is not timely or informative about overall PHN delivery model performance, and does not include information about individual PHN performance. IT systems for PHN performance reporting are partly fit-for-purpose.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made six recommendations aimed at establishing performance measures that are related to PHN delivery model objectives; developing a strategy to assure PHN-supplied performance data; releasing timely annual reporting; reporting on individual PHN performance; improving the usefulness and completeness of performance reporting; and implementing a fit-for-purpose IT system for capturing, validating and reporting on PHN compliance and performance.

The ANAO also suggested that Health could: improve a program logic for the PHN delivery model; consider the availability of secondary data when selecting performance measures and determining reporting timeframes; and include financial and efficiency analysis in annual reports.

3.1 Internal and external performance measurement and reporting facilitates good management, governance and decision-making. External reporting plays an important role in maintaining public trust.

- The Commonwealth Performance Framework sets out requirements for Australian Government entities for measuring, assessing and publicly reporting on activities.27

- The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) require that ‘grants administration should have a performance framework that is linked to an entity’s strategic direction and key performance indicators.’28

- The Commonwealth Evaluation Policy and Toolkit (which was established on 1 December 2021) emphasises the importance of a program logic model in developing performance information.29

- The Archives Act 1983 makes Commonwealth agencies responsible for following record keeping requirements set out in the Information Management Standards. Principle Seven of the Information Management Standards states that business information is to be saved in systems where it can be appropriately managed, protecting the integrity of the information and supporting trusted and reliable use.30

Is there a fit-for-purpose program logic?

Health established a program logic for the PHN delivery model in 2015, which was revised in 2018 and 2023. The 2018 program logic contains most of the expected elements of a program logic and provides information about how the PHN delivery model will achieve outcomes. The 2023 program logic introduces new objectives for the PHN delivery model, lacks clarity and is not aligned with guidance on developing program logics.

3.2 The Australian Institute of Family Studies states that the purpose of a program logic is to:

… show how a program works and to draw out the relationships between resources, activities and outcomes … The logic model is both a tool for program planning — helping you see if your program will lead to your desired outcomes — and also for evaluation — making it easier to see what evaluation question you should be asking at what stage of the program.31

3.3 The Commonwealth Evaluation Toolkit includes a program logic template and guide. The program logic template suggests considering program objectives, inputs, activities, outputs, and causally linked short-term, medium-term and long-term outcomes.32

3.4 Health first established guidance (the Performance Measurement and Reporting Framework) on developing a program logic model in 2021. The guidance includes contradictory information as it refers to two different sets of program logic elements, one of which is consistent with the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy and Toolkit. In March 2023 Health finalised a set of evaluation fact sheets, one of which contains guidance on developing a program logic and a template that is consistent with the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy and Toolkit.

3.5 Health has established a program logic for the PHN delivery model.

- The first model was developed in 2015 and was consistent with the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy and Toolkit.

- The 2015 program logic was replaced in 2018. The 2018 program logic model focused on the core function of PHNs (primary care) and included a separate program logic for each of the seven priority areas (see paragraph 1.2 and Appendix 6).

- Health established a new program logic in 2023 that consolidated the work PHNs do across core functions and all priority areas (see Appendix 6).

3.6 The 2018 program logic contains inputs, activities, outputs, and medium- and long-term outcomes that are consistent with the stated objectives (see paragraph 1.1) of the PHN delivery model. Longer-term outcomes are that ‘PHNs support local primary health care services to be efficient and effective, meeting the needs of patients at risk of poor health outcomes’ and ‘Patients in local region receive the right care in the right place at the right time’.33 There are five ‘intermediate’ outcomes.34

3.7 Although the 2018 core program logic contains most of the expected elements of a program logic, some of its characteristics reduce its effectiveness as a tool for program planning and evaluation. Outcomes are vague. For example, terms such as ‘quality care’ could be more defined. Three of the five ‘outcomes’ more closely resemble outputs.35 Anticipated outcomes are not supported by more specific timeframes for their achievement, other than being described as ‘intermediate’ and ‘longer-term’. Outcomes in the seven 2018 priority area program logics are more specific and describe changes in knowledge, skills and behaviour.36 On the basis of the program logics alone, the logical link between outputs and outcomes is not always clear.37 However, the 2018 program logic was supplemented by a ‘theory of change’, which provided context for the causal relationships between the elements.38