Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Design and Monitoring of the Rural Research and Development for Profit Programme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design process for the Rural Research and Development for Profit Programme, including performance measurement and reporting arrangements.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Rural Research and Development (R&D) for Profit Programme is a competitive grants programme administered by the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources. The programme implements a 2013 federal election commitment from the then Opposition, and was initially funded for $100 million over four years (from 2014–15 to 2017–18). In July 2015, as part of the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper, the Government announced an extension of the programme by four years (through to 2021–22) and an additional $100 million in programme funding.1 The programme aims to realise productivity and profitability improvements for primary producers by:

- generating knowledge, technologies, products or processes that benefit primary producers;

- strengthening pathways to extend the results of rural R&D, including understanding the barriers to adoption; and

- establishing and fostering industry and research collaborations that form the basis of ongoing innovation and growth of Australian agriculture.

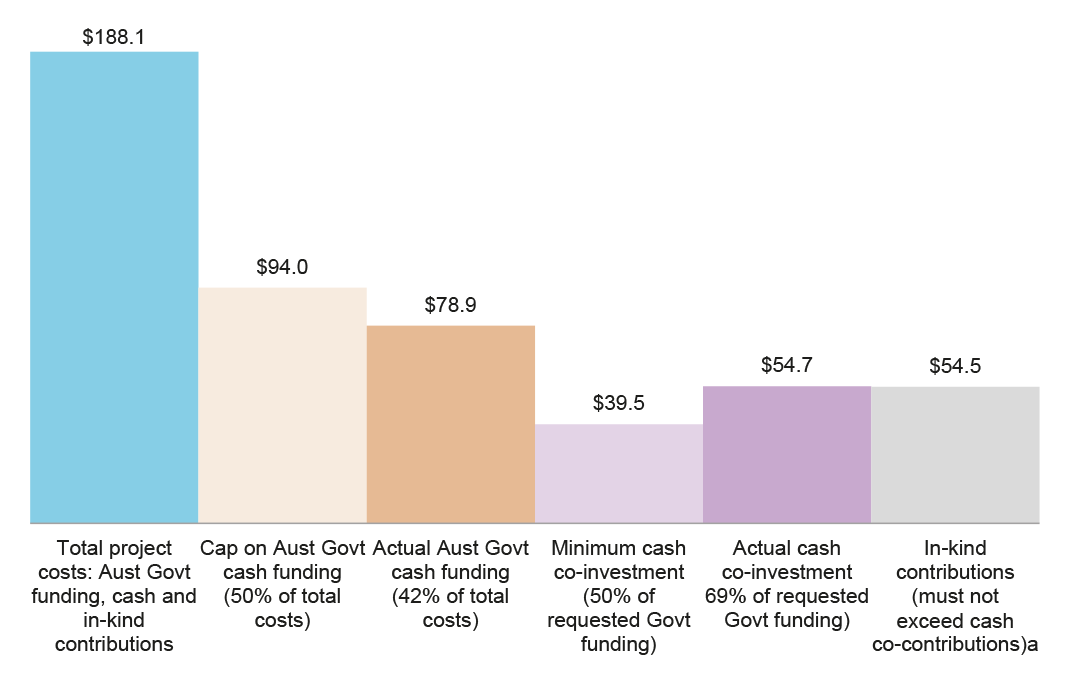

2. The Rural R&D for Profit Programme is open to the 15 Australian Rural Research and Development Corporations (RDCs).2 A condition of funding is that the RDCs must partner with other researchers, and the RDCs and/or partners must provide cash co-contributions to their project. As at September 2016, two rounds of the programme had been completed, with a total of $78.9 million in Australian Government funding approved for 29 R&D projects. The RDCs and their partners have committed to provide $54.7 million cash and $54.5 million in-kind contributions to the funded projects.

Audit approach

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design process for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, including performance measurement and reporting arrangements. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Did the department establish an appropriate design process to support the achievement of the Government’s policy objectives?

- Did the department establish sound performance measurement, reporting and evaluation arrangements?

Conclusion

4. The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ selection of a competitive grants delivery model for the Rural Research and Development (R&D) for Profit Programme—in favour of existing mature funding arrangements—was not informed by an appropriately structured and documented assessment of alternative delivery models. The absence of such an assessment limited the department’s ability to demonstrate that the most appropriate model was selected. There was also limited evidence to demonstrate the basis on which an additional $100 million in funding (to be provided under the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper) was allocated to the programme. Further, the performance monitoring and reporting framework established for the programme does not provide sufficient information about progress towards achievement of the programme objectives. As a result, the department is not well positioned to determine the extent to which the programme’s objectives have been met and to inform stakeholders, including the Parliament, of programme achievements.

Supporting findings

5. Agriculture did not appropriately consider a range of delivery models for the programme, particularly in light of its decision to recommend an alternative delivery model to the established mature funding arrangements in place for the delivery of Australian-Government funded rural R&D. A more robust assessment and documentation of the options for programme delivery would have better assisted the Government to determine the advantages, risks and costs of the proposed delivery model.

6. The department established a sound process to develop the more specific aspects of the programme’s design and implementation, such as the research priorities and the eligibility and assessment criteria. There was, however, scope for the department to have given greater consideration to the impact of the programme’s co-contribution requirements.

7. The department did not consult external stakeholders regarding the development of a delivery model for the programme. Once the delivery model had been determined, the department conducted a range of engagement activities to develop the detailed design parameters for the programme, particularly in relation to the research priorities and grant guidelines. In response to the feedback obtained from stakeholder engagement activities, a number of changes were made to elements of the programme design.

8. To date, the department has conducted two internal reviews and made a number of adjustments to the programme’s implementation in response to review findings.

9. In the absence of data on the achievement of programme objectives, the department and the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper Taskforce drew on a range of available information to support the recommendation to government to extend the Rural R&D for Profit Programme. However, the basis on which key parameters for extension were determined—including the additional funding of $100 million and four year extension—was not documented.

10. The project funding agreements established under the programme provide a sound basis for the collection of data to inform performance measurement, reporting and evaluation activities. To better position the department to monitor implementation and to undertake the planned evaluations, there would be benefit in strengthening quality assurance processes to ensure that the data provided by funding recipients is accurate, fit-for-purpose and comparable.

11. The current performance measurement and reporting arrangements for the programme do not provide internal and external stakeholders with sufficient information about the extent to which programme objectives are being achieved. The development of performance measures that more clearly report on the progress towards the achievement of programme outcomes would better inform stakeholders, including the Parliament, on the success (or otherwise) of the programme.

12. The department developed an evaluation strategy early in the programme’s implementation, with an evaluation of programme achievements planned for year four (2018) and year eight (2022) of the programme. There is scope for the department to more clearly outline its approach to measuring performance against all programme objectives.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.6 |

The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should ensure that the design of new programmes is informed by an appropriate assessment of costs, risks and benefits of alternative delivery models. Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.18 |

The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should expand the existing performance measures for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, and/or develop additional measurement tools, to better inform an assessment of the achievement of (or progress towards) programme objectives. Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

13. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor‐General Act 1997 was provided to the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources and an extract of the proposed report was provided to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s summary responses are provided below, while their full responses are provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (the department) considers the ANAO’s findings provide a basis for further improvements in developing new programmes and in managing existing programmes.

The department is committed to improving the delivery of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme and has already implemented a number of procedures to strengthen delivery.

The department will consider the ANAO’s suggestions for improvements to future rounds, such as:

- improving documentation of the assessment process

- strengthening the performance measurement and evaluation of the programme

- improving the communication of programme and project outcomes.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) considers that the proposed report provides an accurate account of the Department’s involvement in the Rural R&D for Profit Programme.

PM&C notes the audit finding and acknowledges the importance of effective record keeping practices when short-term Taskforces are hosted in PM&C.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Successive Australian governments have recognised that a key driver of agricultural growth and improved productivity and competitiveness is the generation of new knowledge and technology through rural research and development (R&D) activities. One of the primary mechanisms through which rural R&D is funded and delivered in Australia is through the work of Rural Research and Development Corporations (RDCs).3

Rural Research and Development Corporations

1.2 There are 15 rural RDCs in Australia, covering the agriculture, fisheries and forestry industries. RDCs were established in the late 1980s to commission and manage R&D activities aimed at improving productivity, profitability and long-term sustainability of Australia’s primary industries.

1.3 The RDCs were initially established as government bodies. Since their establishment as statutory entities in the late 1980s, a number of RDCs have become industry-owned companies. The transformation to industry-owned companies was primarily undertaken to streamline existing industry bodies and to provide flexibility for the provision of additional services to industry, such as market development, access and promotion.4 This has resulted in RDCs operating under different legislative underpinnings.5 Of the 15 RDCs, 10 are industry-owned companies and five remain Commonwealth statutory entities (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Australian Rural Research and Development Corporations

|

Commonwealth Statutory RDCs |

|

Australian Grape and Wine Authority (Wine Australia) |

|

Cotton Research and Development Corporation |

|

Fisheries Research and Development Corporation |

|

Grains Research and Development Corporation |

|

Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation |

|

Industry RDCs |

|

Australian Egg Corporation Limited |

|

Australian Livestock Export Corporation Limited (LiveCorp) |

|

Australian Meat Processor Corporation |

|

Australian Pork Limited |

|

Australian Wool Innovation Limited |

|

Dairy Australia Limited |

|

Forest and Wood Products Australia |

|

Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited |

|

Meat and Livestock Australia |

|

Sugar Research Australia Limited |

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

1.4 The RDCs are funded through industry levies, with matched funding provided by the Australian Government (generally up to a limit of 0.5 per cent of each industry’s Gross Value of Production). Agricultural levies and charges are imposed on primary producers by government, at the request of industry, to collectively fund R&D, marketing, biosecurity and residue testing programs. The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (Agriculture) is responsible for the collection, administration and disbursement of levies and charges on behalf of Australian agricultural industries. Over recent years, the matched Australian Government funding for RDCs has been around $250 million per annum.

1.5 The 15 RDCs are established in legislation and are also subject to either the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (statutory RDCs) or the Corporations Act 2001 (industry-owned RDCs).6

1.6 Under the establishing legislation, there is a statutory funding agreement (generally covering a four-year period) between each RDC and the Commonwealth (represented by Agriculture) that outlines requirements for:

- corporate governance and reporting;

- strategic and operational planning, including identification of key research investment priorities (statutory RDCs and five of the ten industry-owned RDCs must seek the Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources’ endorsement of their strategic/research plan, while the remaining industry-owned RDCs are required to consult with the Minister on their strategic/research priorities7); and

- implementation of levy arrangements.

1.7 The requirements established under the statutory funding agreements, in particular the requirement for RDCs to regularly engage with Agriculture and to seek the Minister’s endorsement of their strategic plans, provide an important mechanism through which the Australian Government can influence the rural R&D agenda, including the role of cross-sectoral and public-good research.

1.8 The 15 RDCs are members of the Council of Rural RDCs, which was established to provide a forum for the organisations to discuss and work collaboratively on issues relevant to rural R&D. The Council also aims to, among other things: support, encourage and facilitate continual improvement in the delivery of efficient and effective services to rural industries and the community, particularly with regard to research, development, technology transfer and adoption; and represent and position the RDCs as participants in the rural innovation system.8

Establishment of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme

1.9 The establishment of a programme to provide $100 million in additional funding for RDCs (above their levy and matched Australian Government income) was foreshadowed in the then Opposition’s agriculture election policy in August 2013, as outlined below:

|

The Coalition’s Policy for a Competitive Agriculture Sector, August 2013 [extract] |

|

Research and Development for Profit The Coalition will invest $100 million in additional funding for Rural Research and Development Corporations. The Coalition’s funding boost will enable Rural Research and Development Corporations to better deliver cutting edge technology, continue applied research, and focus on collaborative innovation and extension. Funding will be allocated to specific projects that openly enhance agricultural profitability, level out competition and better leverage coordination and cooperation between stakeholders. In conjunction with increased investment, the Coalition will work with research and development organisations and levy payers to improve the collaboration on research and to provide even better returns on investment. |

Source: The Coalition’s Policy for a Competitive Agriculture Sector, August 2013, pp. 4–5.

Establishment and extension of the programme

1.10 Following the 2013 federal election (September 2013), the Government announced the establishment of the Rural Research and Development (R&D) for Profit Programme, with $100 million to be delivered over four years (2014–15 to 2017–18).9 The programme is administered by Agriculture.

1.11 In July 2015, an additional $100 million for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme and an extension through to 2021–22 was announced in the Government’s Agricultural Competiveness White Paper.10

Programme objective

1.12 The objective of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme is to realise productivity and profitability improvements for primary producers through:

- generating knowledge, technologies, products or processes that benefit primary producers;

- strengthening pathways to extend the results of rural R&D, including understanding the barriers to adoption; and

- establishing and fostering industry and research collaborations that form the basis for ongoing innovation and growth of Australian agriculture.11

Funding and delivery arrangements

Programme funding

1.13 The initial $100 million in programme funding to be delivered over four years (from 2014–15 to 2017–18) was announced in the 2014–15 Budget. Following the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper announcement regarding the extension of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, the 2015–1612 and 2016–17 Budgets included additional funding for the programme.13 The Government also announced as part of the 2016–17 Budget a reduction in programme funding of $9.5 million in the 2016–17 financial year to direct funding to the National Water Infrastructure Fund.

1.14 The department’s administrative costs to deliver the programme were included in the initial $100 million allocation. The department was allocated $2.9 million for administrative expenses over the first four years of the programme (2014–15 to 2017–18). These expenses primarily comprise programme staff salaries (4.75 full-time equivalent staff) and a planned evaluation in 2017–18.14 In addition to the department’s administrative expenses, the fees and travel costs for Expert Panel members (totalling around $40 000 for each funding round) are also sourced from the $100 million in programme funding.15

1.15 When the funding reduction that was announced in the 2016–17 Budget and the department’s administrative costs are taken into account, the funding that is available for grants to RDCs and their partners over the life of the programme is around $187 million.

Competitive grants

1.16 The Rural R&D for Profit Programme is being delivered through a competitive grants process. As at September 2016, two funding rounds had been completed. Grant funding under the programme is only available to the 15 RDCs, with a condition of funding that the applicant RDC must partner with one or more researchers, research agencies, other RDCs, businesses, producer groups or not-for-profit organisations, to deliver a collaborative research project.

1.17 Under the programme, co-investment from the applicant RDCs and/or partner organisations is also required. In the two funding rounds conducted to date, Australian Government funding from the Rural R&D for Profit Programme was capped at 50 per cent of the total project costs (grant, cash and in-kind contributions), and RDCs/partners were required to provide a cash contribution, with the option of also providing in-kind contributions (as outlined in Figure 1.1).16

Figure 1.1: Co-investment requirements for the programme (cash and in-kind)

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Funding outcomes

1.18 As at September 2016, 29 projects had been approved for funding under the two completed funding rounds, with a total commitment of $78.9 million in Australian Government funding (42 per cent of the available programme funding).17 An overview of the funding rounds and the levels of Australian Government funding and cash and in-kind18 co-investment for funded projects is provided in Table 1.2 and Figure 1.2.

Table 1.2: Grant funding rounds—applications and outcomes

|

Funding round |

Applications received |

Applications assessed |

Approved projects |

Funding outcomes |

|

|

|

|

Ineligible |

Merit assessed |

|

|

|

1 |

52 |

18a |

34 |

12 |

|

|

2 |

38 |

1 |

37 |

17 |

|

Note a: Fourteen of the applications were assessed as ineligible because the proposed in-kind contributions did not comply with the requirements outlined in the grant guidelines. This requirement was changed for Round 2.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Figure 1.2: Australian Government funding and co-investment, Rounds 1 and 2 ($m)

Note a: As outlined earlier, the cap on in-kind contributions was removed for Round 2.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental data.

1.19 Over the two funding rounds conducted to date, the selected projects’ cash co-contributions have exceeded the minimum requirements established for the programme. This indicates a capacity by RDCs and the broader R&D sector to contribute funding and in-kind support.19 It should, however, be recognised that funding contributed by RDCs to the Rural R&D for Profit Programme incorporates a percentage of Australian Government funding (under the RDCs’ matched funding arrangements). The funding that has been directed by RDCs to the programme is, therefore, diverted from the key research investment priorities identified by RDCs in their strategic/research plans.

1.20 An outline of the key stages in the announcement and implementation of the R&D for Profit Programme is provided in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Programme implementation timeline, August 2013 to July 2016

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Audit approach

Objective, criteria, and methodology

1.21 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design process for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, including performance measurement and reporting arrangements. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Did the department establish an appropriate design process to support the achievement of the Government’s policy objectives?

- Did the department establish sound performance measurement, reporting and evaluation arrangements?

1.22 The ANAO examined departmental records and conducted interviews with departmental officers. All RDCs and a number of other stakeholders were invited to contribute to the audit, with five RDCs, the Council of Rural RDCs and two other stakeholders electing to do so.

Scope

1.23 The performance audit focused on the design of the programme and its performance measurement, reporting and evaluation arrangements. The audit did not include a detailed examination of the department’s arrangements for managing funded projects.

Performance review

1.24 The ANAO also completed a performance review of the grant assessment and selection processes established for Round 1 of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme.

|

Performance Review of the Grant Assessment and Selection Process |

|

The ANAO’s Auditing Standards provide for the conduct of performance reviews. A review of this nature provides less assurance than is provided under a performance audit.a The performance review focussed on the oversight, planning and conduct of the grants application assessment and selection process for Round 1 of the programme. In conducting the review, the ANAO examined whether the records retained by the department indicated that:

Based on the procedures performed and the evidence obtained, nothing came to the ANAO’s attention to cause it to believe that the assessment and selection process for Round 1 of the programme had been materially affected by: weaknesses in the framework established to conduct the process; variations in the planned approach; or the lack of required approvals at key stages. |

Note a: A performance review provides limited assurance. In this type of review, the objective is a reduction in performance engagement risk to a level that is acceptable in the circumstances of the engagement, as the basis for a negative form of expression of the review conclusion. The acceptable performance engagement risk in a limited assurance engagement is greater than for a reasonable assurance engagement. The Standard on Assurance Engagements ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements, issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

1.25 The audit and performance review were conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $225 000.

2. Programme design

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the design of the Rural Research and Development (R&D) for Profit Programme, including: the department’s initial consideration of options for delivery; detailed programme design; advice to government; and the evidence underpinning the additional funding to, and extension of, the programme.

Conclusion

The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ selection of a competitive grants delivery model for the Rural Research and Development (R&D) for Profit Programme—in favour of existing mature funding arrangements—was not informed by an appropriately structured and documented assessment of alternative delivery models. The absence of such an assessment limited the department’s ability to demonstrate that the most appropriate model was selected. There was also limited evidence to demonstrate the basis on which an additional $100 million in funding (to be provided under the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper) was allocated to the programme.

Areas for improvement

One recommendation has been made for the department to ensure that the design of new programmes is informed by an appropriate assessment of costs, risks and benefits of proposed delivery models, and any credible alternatives.

Did the department establish an appropriate programme design process?

Agriculture did not appropriately consider a range of delivery models for the programme, particularly in light of its decision to recommend an alternative delivery model to the established mature funding arrangements in place for the delivery of Australian-Government funded rural R&D. A more robust assessment and documentation of the options for programme delivery would have better assisted the Government to determine the advantages, risks and costs of the proposed delivery model.

The department established a sound process to develop the more specific aspects of the programme’s design and implementation, such as the research priorities and the eligibility and assessment criteria. There was, however, scope for the department to have given greater consideration to the impact of the programme’s co-contribution requirements.

Delivery model considerations

2.1 The then-Opposition’s election policy announcement in August 2013 stated that an additional $100 million would be provided to RDCs for allocation to specific projects. The programme’s initial four-year time frame and its funding profile were also outlined in policy documents20. The election policy did not outline in further detail the then-Opposition’s expectations about how the programme was to be delivered.

2.2 As outlined in Chapter 1, there are mature arrangements in place to deliver funding (both industry-sourced levy payments and matching Australian Government contributions) to the RDCs for rural R&D and extension activities. These arrangements are underpinned by a statutory funding agreement, which identifies key research investment priorities. It would generally be expected that, where existing mature funding arrangements are in place, these would be used to deliver additional funding for like purposes. In those circumstances where it is determined that existing funding arrangements would not effectively support the policy outcomes sought from new funding, then the basis of this determination should be documented and provided to government along with the costs and benefits of alternative approaches.

2.3 Agriculture decided to use a competitive grants process administered by the department instead of tailoring the existing, mature funding arrangements that were in place to provide levy and matching funding to RDCs and to determine key research investment priorities. The department informed the ANAO that while the relative merits of different funding delivery models were canvassed in internal departmental discussions, these discussions were not recorded and the department did not document any research and analysis that had underpinned the deliberations. The department advised that a detailed analysis would have been difficult to undertake given the timing constraints for the new policy development process. Within the context of the Australian Government’s budget preparation processes and associated decisions, the department had around five months to determine the delivery model and design parameters for the programme.

2.4 In a briefing to its Minister in January 2014, the department outlined its views on the delivery arrangements for the $100 million Rural R&D for Profit Programme. The briefing did not sufficiently demonstrate why the department considered that the existing RDC funding arrangements were not considered suitable to deliver the new programme. The briefing outlined two alternative delivery models (see Table 2.1), but indicated that the competitive grants process would be the most effective method of delivering the programme, taking into account factors such as project selection processes used by RDCs, Ministerial oversight and the need for streamlined delivery.

Table 2.1: Programme delivery options outlined in Ministerial briefing

|

Delivery Options Outlined in the Department’s Briefing to the Minister |

||

|

Delivery Option |

Identified Benefits |

Identified Risks |

|

Allocate funds to individual RDCs in proportion to their annual appropriations, with additional guidance from the Government on priority areas of research. |

Lower delivery costs. [ANAO: the quantum of cost savings was not detailed in the briefing] |

Funding more likely to be expended on a ‘business-as-usual’ basis as project selection would occur through existing processes, with lost opportunity for strategic investment. |

|

Contract the Rural Industries RDC (RIRDC) to deliver the programme using its existing project selection processes, with additional guidance from the Government on priority areas of research. |

None identified. |

Potential conflicts of interest Other stakeholders may be concerned about limitations in sector-specific expertise within the RIRDC. |

|

[Preferred option]: Deliver funds through a competitive grants programme with priority areas of research outlined in programme guidelines. |

Detailed grant guidelines could ensure targeting of funds to meet the programme’s objectives. Scope for the Minister to be involved in approving projects (on the advice of an Expert Panel). Delivery costs were estimated at approximately $3 million over four years. |

None identified. |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

2.5 Overall, the department’s advice to the Minister on the broad programme design contained limited detail on the alternative delivery models. The brief did not sufficiently outline the expected benefits or risks associated with the recommended competitive grants model, or compare the three delivery models in terms of:

- delivery costs;

- the administrative burden for RDCs and their partners;

- alignment with RDCs’ existing strategic research agenda; and

- the knowledge and expertise required to determine research priorities and assess R&D outcomes.

Recommendation No.1

2.6 The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should ensure that the design of new programmes is informed by an appropriate assessment of costs, risks and benefits of alternative delivery models.

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ response: Agreed.

2.7 The department will ensure that assessments of delivery options are appropriately documented and reflected in briefings to ministers on new programmes, including consideration of the costs, risks and benefits of alternative delivery models whenever possible.

Detailed programme design

2.8 Once the Minister had been advised of the proposed approach to deliver the programme through a competitive grants process, the department was responsible for developing the programme’s detailed design parameters.

Programme objective and selection criteria

2.9 A key consideration when developing the detailed design parameters was the requirement for the programme to deliver on the election commitment, that is to better deliver cutting edge technology, continue applied research, and focus on collaborative innovation and extension. Specifically, funding was to be allocated to projects that openly enhance agricultural profitability, level out competition and better leverage coordination and cooperation between stakeholders.21 The department was responsible for developing an appropriately aligned objective and a set of eligibility and merit assessment criteria to ensure that funding was directed to those projects that best supported the policy intent.

2.10 The objective developed by the department (outlined in Chapter 1) was appropriately aligned to the initial election commitment, with an emphasis on: generating knowledge, technologies, products or processes that benefit primary producers; extension and adoption of R&D results and establishing and fostering industry and research collaborations.

2.11 The competitive grants eligibility and selection criteria and ‘programme priorities’22 also reflected the election commitment and programme objective, by requiring project proponents to demonstrate how the proposed R&D and extension project would:

- deliver against the programme objective and at least one of the programme priorities;

- have benefits for more than one industry;

- form new collaborations;

- result in quantifiable returns on investment; and

- would not have otherwise been undertaken.23

2.12 The programme objective, priorities and the eligibility and selection criteria were approved by the Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources through the established processes for developing and approving Commonwealth grant guidelines.

Co-investment requirements

2.13 Under the co-investment requirements developed by the department and included as an eligibility criterion in the competitive grants rounds, project proponents and/or their partners were required to provide cash funding for their proposed projects (of at least 50 per cent of the requested Australian Government funding). They could also provide in-kind contributions. The department considered that seeking co-contributions would leverage the Government’s funding by generating larger, multi-year research projects, which may deliver results in a shorter timeframe or on a larger scale than could be achieved through one proponent.

2.14 The Rural R&D for Profit Programme differs from a number of other government programmes that seek a co-investment by project proponents, because in this case the project proponents (the RDCs) are government-funded bodies.24 While the programme guidelines stated that cash co-contributions could be sourced from the RDCs and/or their partners, in the rounds conducted to date 62 per cent of the cash contributions (nearly $34 million out of the total $54.7 million) have been sourced from the RDCs. As outlined in Chapter 1, these RDC resources would otherwise have been directed to R&D projects that aligned with their strategic research investment priorities and plans.25 The potential for this outcome was not outlined by the department in its briefings to the Minister.

Advice on programme implementation

2.15 The department provided regular advice to the Minister during programme implementation, including in relation to the conduct of the first assessment round and revisions to the guidelines and priorities for Round 2 arising from stakeholder feedback (as discussed in paragraph 2.20).

Did the department consider the views of relevant stakeholders when designing the programme?

The department did not consult external stakeholders regarding the development of a delivery model for the programme. Once the delivery model had been determined, the department conducted a range of engagement activities to develop the detailed design parameters for the programme, particularly in relation to the research priorities and grant guidelines. In response to the feedback obtained from stakeholder engagement activities, a number of changes were made to elements of the programme design.

2.16 The department did not consult external stakeholders regarding a delivery model for the programme. The department advised that, as the delivery model was developed as part of the 2014 Budget process, consultation with external stakeholders was limited due to confidentiality requirements. Notwithstanding these requirements, the broad parameters of the program were announced as part of the election commitment and would have provided the basis on which initial engagement with stakeholders could have occurred.

2.17 The department informed the ANAO that RDCs had raised the implementation of the election commitment in a number of routine meetings with the department held after the election commitment had been announced. Following the announcement of the programme funding in the 2014–15 Budget, the department engaged with stakeholders, primarily the RDCs, on the detailed design parameters for the programme.

Programme priorities and Round 1 application materials

2.18 As outlined earlier, the programme priorities were developed to target Australian Government funding towards specific areas of research. Each proposed project was required to address one or more of these priorities. The department sought views from the RDCs on the programme priorities and later, the detailed grant guidelines for Round 1 of the programme, through engagement activities such as round-table meetings and by circulating the draft programme guidelines for comment.

2.19 A key outcome of the consultation with stakeholders prior to the launch of the first funding round was the amendment of the grant guidelines to allow for the recognition of in-kind contributions. RDCs had advised the department that the proposed requirement for matched cash co-contributions would limit the ability of research partners to participate, as they may not be able to raise sufficient cash contributions and their non-cash contribution to the project would not be recognised. In response to these concerns, the revised guidelines stated that the department would accept in-kind contributions valued at up to 50 per cent of the total applicant/partner co-contribution amount (see Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1).26

Round 2 application materials

2.20 Following the completion of Round 1 in May 2015, the department met with RDCs and invited comment from a range of other stakeholders (primarily potential research partners in the programme), to obtain feedback on the conduct of the funding round. The matters raised by stakeholders are outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Feedback received on the implementation of Round 1

|

Feedback from RDCs |

Departmental response |

|

Limit on in-kind contributions had constrained participation by prospective research partners and reduced the potential leverage of government funds. |

Removed the cap on in-kind contributions for Round 2. |

|

The four-year timeframe for the programme would limit the types of projects that could be proposed for Round 2. |

In July 2015, the Government announced that the programme would be extended through to 2021.a |

|

The application form should be modified, to seek additional information to demonstrate why the proposed project would not be considered ‘business as usual’.b |

The application form for Round 2 included two additional questions requiring applicants to demonstrate how the proposed research would differ from RDCs’ usual research and why it would not otherwise be funded. |

Note a: Departmental records did not indicate that the feedback from the RDCs was a factor in this decision.

Note b: This concern was also raised by Expert Panel members in the post-implementation review conducted for Round 1.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Stakeholder feedback to the ANAO

2.21 As outlined in Chapter 1, a number of RDCs, the Council of Rural RDCs, and other stakeholders provided feedback to the ANAO on the implementation of the programme. Overall, this feedback indicated that the additional funding for rural R&D was welcomed by RDCs and stakeholders and that new partnerships between RDCs and in the broader Australian rural research community have been established.

2.22 The feedback provided in relation to the collaborative aspects of the programme was mixed. Specifically, it was considered that the potential for effective collaboration was constrained by: the competitive nature of the programme; the relatively short application period; and/or the incentive to select research partners on the basis of their ability to provide co-contributions rather than the suitability of their research capabilities to the proposed project.

2.23 Feedback also highlighted potential issues associated with the eligibility conditions that only allow individual RDCs to apply.27 While this was seen by one stakeholder to present advantages for streamlined and cost-effective delivery, others suggested that RDCs had received large numbers of unsolicited proposals from interested research partners, resulting in a significant administrative burden during the application period. An RDC also suggested that restricting applicants to RDCs had limited the potential for large-scale, cross-sectoral research.

2.24 RDCs also outlined their view that given their experience in delivering rural R&D, they would have been well placed to be more directly involved in the delivery of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, for example:

For nearly three decades now the RDCs have been actively working with industries to prioritise R&D needs, procure and manage R&D that responds to these needs and communicate the outcomes. As a result, each RDC has significant experience and systems in administering R&D for primary industries and has invested significantly in systems and processes to support this role. Given this considerable experience, which the Australian Government has already invested significant resources in, there are options to better draw on this experience and systems for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme.28

Has the department reviewed the programme design and made adjustments where appropriate?

To date, the department has conducted two internal reviews and made a number of adjustments to the programme’s implementation in response to review findings.

Internal audit and post-implementation review of Round 1

2.25 There have been two internal reviews of the programme since its establishment:

- an internal audit (completed in March 2015), which found that the programme had sound governance, management and reporting arrangements; and

- a post-implementation review of Round 1 (completed in July 2015), which drew on feedback from applicant RDCs, members of the Expert Panel and departmental staff. The review made a number of recommendations aimed at improving the conduct of future funding rounds.

2.26 The conduct of these internal reviews provided the department with the opportunity to consider lessons learned early in the programme’s implementation, and make appropriate adjustments. In response to review findings, the department made a range of changes to the implementation of funding Round 2, such as removing the cap on in-kind contributions to proposed projects.

Was the decision to extend the programme based on appropriate advice?

In the absence of data on the achievement of programme objectives, the department and the Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper Taskforce drew on a range of available information to support the recommendation to government to extend the Rural R&D for Profit Programme. However, the basis on which key parameters for extension were determined—including the additional funding of $100 million and four year extension—was not documented.

White Paper on Agricultural Competitiveness

2.27 In December 2013, the Minister for Agriculture announced the terms of reference for a White Paper on agricultural competitiveness, with consultations occurring throughout 2014. A taskforce established within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, comprising officers from a range of departments, including Agriculture, supported the development of the White Paper.29

2.28 The Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper was released on 5 July 2015. It included the announcement of a further $100 million in funding over four years (2018–19 to 2021–22) for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme.

|

Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper: Rural R&D for Profit extension [extract] |

|

The issues facing agriculture often go beyond single commodities and require collaboration, cross-sectoral and transformational research, and more extension and adoption. The Government’s $100 million Rural R&D for Profit Programme enables such solutions, but it expires in 2017–18. The Government will invest a further $100 million to continue the Rural R&D for Profit Programme between 2018–19 and 2021–22. The programme will emphasise collaboration and adoption. |

Source: Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper: Stronger Farmers Stronger Economy, Commonwealth of Australia, July 2015, p. 93. Available from: <http://agwhitepaper.agriculture.gov.au/> [accessed 14 July 2016].

Evidence underpinning the proposal to extend the programme

2.29 Agriculture informed the ANAO that the need for a measure to support research addressing cross-sectoral issues (such as weed and pest control, water, climate change and technology improvements) had been highlighted in submissions to the White Paper Taskforce and in discussions held across Australia with a broad range of stakeholders. The ANAO’s review of the 383 publicly available submissions30 found that 67 (17.5 per cent) of the submissions were broadly supportive of improving rural research, development and extension activities. A smaller sub-set of these submissions (19 submissions out of the 383 reviewed—five per cent) mentioned the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, and 11 of those (2.8 per cent of the total public submissions) recommended extending it.

2.30 The Green Paper (published in October 2014)31 included a ‘policy idea’ titled ‘Strengthening the RD&E system’. This idea included the option of establishing a new body, or tasking existing research bodies, to coordinate cross-sectoral research. This could be supported by (inter alia) using part of the $100 million allocated to the Rural R&D for Profit Programme to fund cross-industry and transformational R&D, according to the Green Paper.32

2.31 Following the release of the Green Paper, the White Paper Taskforce developed a range of options to implement each of the proposed policy ideas, including ‘Strengthening the RD&E system’. Agriculture provided feedback to the taskforce on this option, commenting that ‘we consider it best to allow the Rural R&D for Profit Programme to run its course and to assess its outcomes. A key question is “does cross-sectoral research generate greater value?” This could then inform future policy options around collaborative and cross-sectoral research.’

2.32 A proposal to extend the Rural R&D for Profit Programme was progressed by the White Paper Taskforce. Agriculture supported the proposal that was developed by the Taskforce and prepared briefings for its Minister and the Government, seeking agreement to extend the programme for four years. The documentation relating to the work of the White Paper Taskforce, which was not easily locatable, did not indicate the basis on which it was considered appropriate to double the programme’s funding and timeframe—from $100 million to $200 million and four years to eight years’ duration.

Advice to government

2.33 Given the early phase of the Rural R&D for Profit Programme’s implementation, the department and the White Paper Taskforce were not able to draw on the outcomes (or substantial progress towards outcomes) to inform the Government’s consideration of a proposed extension and additional funding for the programme. In the absence of outcomes data, the department and the taskforce drew on alternative information that was available, such as the results from the Round 1 application process (for example, the number of new research collaborations to be formed and the level of demand for funding), issues raised in submissions to the White Paper, and taskforce research.

2.34 The advice outlined the views of the department and of the taskforce on the advantages of extending the programme, including that it would:

- address current gaps in cross-sectoral research and adoption of research and development;

- provide a better focus of R&D expenditure on farmers’ needs, driving productivity and profitability;

- be ‘scalable’—that is, an existing programme had been established and extending/expanding it would not cause significant administrative burden;

- enable funding of longer-term, ‘transformational’ research projects; and

- recognise that the first funding round of the programme had been heavily over-subscribed, indicating a strong demand for the programme, including a capacity for RDCs and their research partners to co-invest both cash and in-kind contributions.

2.35 The Government was also advised of the risks associated with extending the programme, in particular, that it was too early to determine whether the programme was delivering its expected outcomes. The Government was not advised of the basis upon which the proposed sum of $100 million (with an immediate funding impact of $25 million) had been determined.

2.36 Given that the decision to extend the programme and to double its funding was not based on evidence demonstrating its success in meeting the Governments’ objectives for the programme, it will be important for the department to undertake a comprehensive programme evaluation to inform the implementation of the second tranche of funding. Programme evaluation is discussed further in Chapter 3.

3. Performance measurement, reporting and evaluation

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the department had established sound performance measurement, reporting and evaluation arrangements for the Rural Research and Development (R&D) for Profit Programme.

Conclusion

The performance monitoring and reporting framework established for the programme does not provide sufficient information about progress towards achievement of the programme objectives. As a result, the department is not well positioned to determine the extent to which the programme’s objectives have been met and to inform stakeholders, including the Parliament, of programme achievements.

Areas for improvement

One recommendation has been made aimed at improving the department’s performance measurement and reporting arrangements for the programme. Suggestions have also been made for the department to:

- strengthen its quality assurance mechanisms to support the planned use of project-level data for programme monitoring and evaluation;

- ensure that the planned programme evaluations sufficiently address all programme objectives; and

- engage with RDCs about programme monitoring and evaluations.

Is the department collecting appropriate data to inform performance measurement, reporting and evaluation?

The project funding agreements established under the programme provide a sound basis for the collection of data to inform performance measurement, reporting and evaluation activities. To better position the department to monitor implementation and to undertake the planned evaluations, there would be benefit in strengthening quality assurance processes to ensure that the data provided by funding recipients is accurate, fit-for-purpose and comparable.

Project-level reporting and evaluation

3.1 The funding agreements executed between the Australian Government and the programme’s funding recipients enable the department to collect project data (primarily through milestone reports) and monitor project delivery.33 The funding agreements also require funding recipients to produce a monitoring and evaluation plan outlining how funding recipients plan to monitor project progress, and the intended outcomes and impact of projects. At the conclusion of each project, the funding agreement also requires the completion of a project evaluation, which must report on ‘the project’s outcomes against the programme objective, including quantitative information on the outcomes achieved and independent expert analysis of expected and/or demonstrated quantifiable returns on investment’.34

3.2 The project-level data provided through milestone reports and the end-of-project evaluations will play an important role in the planned programme-level evaluations to be conducted in 2018 and 2022 (discussed further from paragraph 3.22). The use of this data to inform later evaluations underlines the importance of ensuring the information is accurate, fit-for-purpose and comparable (to the extent possible, given the wide variety in research being undertaken by funding recipients).

Quality assurance

3.3 The six-monthly milestone reports submitted by the funding recipients outline completion of, or progress towards, project activities and outputs. For example, milestone reports reviewed by the ANAO included information on project staffing, signing of partner agreements, plans for extension activities, and laboratory reports containing technical information on tests conducted and results achieved.

3.4 The funding agreements established under Round 1 of the programme state that grant payments will only be made upon completion of the agreed milestones to the ‘reasonable satisfaction of the Commonwealth’.35 The department informed the ANAO that its review of milestone reports includes an assessment of the quality of the information provided by the funding recipient. The key programme documents36 do not, however, sufficiently outline the quality assurance review mechanisms that will be implemented by the department in relation to project-level data.

3.5 In the case of projects funded under Round 1, the project outputs (such as research or technical papers) are not required to be peer reviewed, and the department does not have an established approach to conduct its own expert and/or independent review of technical project information. The department advised that, for project information submitted to date, it has sought assistance to verify technical information, where required, from internal staff members that it considered were appropriately qualified/experienced.

3.6 The department advised that projects funded under Round 2 will not be required to submit technical research reports to the department. Under this round, funding recipients will be required to produce research that is to be published in peer-reviewed journals, conference papers, industry publications and websites. RDCs will be required to provide the department with a list of the prepared, submitted and published research. This new requirement provides an increased level of quality assurance for project data and outputs.

3.7 The consideration and documentation of quality assurance approaches, including the use of a risk-based strategy to target those funding recipients or projects that present greater risk, would provide greater assurance over the quality of project data and outputs.

Project-level evaluation

3.8 As outlined in paragraph 3.1, funding recipients are required to produce and submit a project monitoring and evaluation plan. The department did not specify the required content or detail to be included in monitoring and evaluation plans (for example, by providing a template), but did provide general guidance, such as examples from other grant programmes. The Council of Rural RDCs also advised the ANAO that guidelines and procedures that it has developed will be used by RDCs as the basis for the evaluations required from projects funded under the Rural R&D for Profit Programme.37 The extent to which existing guidelines are being used appears limited, with the project monitoring and evaluation plans reviewed by the ANAO varying in their approaches to project evaluation, the level of detail included, and presentation. The department advised that it will consider the Council of Rural RDC evaluation materials in preparation for the year four programme evaluation.

3.9 The provision of additional guidance on monitoring and evaluation requirements to funding recipients in future rounds would help to ensure that project-level data and outcomes usefully informs the monitoring and evaluation of achievements against the overall programme objectives.

Has the department reported to stakeholders on progress towards the achievement of programme outcomes?

The current performance measurement and reporting arrangements for the programme do not provide internal and external stakeholders with sufficient information about the extent to which programme objectives are being achieved. The development of performance measures that more clearly report on the progress towards the achievement of programme outcomes would better inform stakeholders, including the Parliament, on the success (or otherwise) of the programme.

3.10 The performance measurement and reporting requirements for Commonwealth entities are established under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (the PGPA Act). Since 2015–16, entities have been required to develop a corporate plan, setting out the entity’s strategies for achieving its purposes and determining how success will be measured. Entities are also to prepare annual performance statements, which are to be included in their annual reports. These statements are to provide an assessment of the extent to which the entity has succeeded in achieving its purposes.38

3.11 Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS), which are published as part of the budget each year, are to describe at a strategic level the outcomes intended to be achieved with the funding appropriated by the Parliament. The performance information published in the PBS is to have a strategic focus, aligned with the entity’s corporate plan.39

Performance measurement and reporting

3.12 The department is collecting a range of project-level data—at this stage primarily relating to the completion of project activities and outputs such as technical papers. The data is not currently being analysed by the department to determine programme progress or to inform public reporting on the achievement of (or progress towards) the programme’s objectives. As at September 2016, the performance measures for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme have focused on the achievement of programme delivery activities, as outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Programme performance measures

|

Financial year |

Source |

Published performance measure and target |

Reported performance |

|

2014–15 |

PBS |

Delivery of allocated funding under the Rural R&D for Profit Programme Target: 100 per cent |

Target met (Annual Report 2014–15) |

|

2015–16 |

PBS |

PBS did not include specific measures or targets for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme |

N/a |

|

Corporate Plan

|

Investment in Rural RDC programmes demonstrates positive returns Target: not specified Allocated funding under the Rural R&D for Profit Programme is expended in accordance with the agreed timetable Target: 100 per cent Rural research and development corporations are compliant with statutory and contractual requirements Target: 100 per cent |

Not yet available Due to be reported in the department’s Annual Performance Statement, as part of the Annual Report 2015–16 |

|

|

2016–17 |

PBS |

As for previous year, none specified |

N/a |

|

Corporate Plan |

Investment in Rural RDC programmes demonstrates positive returns Target for 2019–20: Evaluation of investment in agricultural research, development and extension shows positive returnsa Allocated funding under the Rural R&D for Profit Programme is expended in accordance with the agreed timetable Target: 100 per cent Rural research and development corporations are compliant with statutory and contractual requirements Target: 100 per cent |

Not yet available |

Note a: The Corporate Plan stated that ‘Given the long-term relationship between research and development and productivity, we will not report against this performance indicator every year’.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

3.13 The department’s Corporate Plan 2015–19 provided further information on the manner in which the department intends to deliver ‘Building Successful Primary Industries’, including short-term success indicators (such as those for the Rural R&D for Profit programme as outlined in Table 3.1). These indicators are to be used in the interim as the department works towards measuring success under its strategic-level indicators.

3.14 The performance measures established for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme to date are activity-based (primarily focussed on ‘getting money out the door’). The department advised that this approach reflected the programme’s establishment phase (particularly in 2014–15). The department also identified that the long-term outcomes of the research being funded via the programme may not be realised for many years beyond each project’s completion (and the programme’s eight-year timeframe).

3.15 While the current performance measures provide some useful insights into programme delivery, they do not inform departmental management and external stakeholders about the effectiveness of the programme or the department’s progress towards meeting the Government’s programme objectives.

3.16 The programme’s Evaluation Plan (discussed further at paragraph 3.22) identifies a range of measures that could be used to provide more meaningful performance information in the interim period before the first planned evaluation is undertaken (after four years), including:

- Is the programme generating knowledge, technologies, products or processes that benefit primary producers?

- How do the knowledge, technologies, products or processes generated, contribute to improving the productivity and/or profitability of primary producers?

- Is the programme improving the department’s understanding of the barriers to adoption, and is it strengthening pathways to extend the results of rural R&D to producers? and

- Is the programme establishing new research collaborations?

3.17 These measures, if refined including by setting targets for success, would provide stakeholders (including the Parliament) with further useful performance information on programme progress.

Recommendation No.2

3.18 The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources should expand the existing performance measures for the Rural R&D for Profit Programme, and/or develop additional measurement tools, to better inform an assessment of the achievement of (or progress towards) programme objectives.

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources’ response: Agreed.

3.19 The department will consider, and implement where appropriate, the ANAO’s suggestions for improving the programme’s evaluation plan and performance measurement activities.

External reporting

3.20 The department reports publicly on the Rural R&D for Profit Programme via its annual report and website.40 As the programme was established in 2014–15, there has only been one annual report covering the programme’s performance to date (the 2014–15 Annual Report—published in October 2015). In this report, the department stated that it had successfully implemented Round 1 of the programme, having allocated $26.7 million in funding to 12 projects over four years. There was no additional performance information provided. The programme website includes: background information on the programme; outlines of funded projects; application materials; and information regarding the grant assessment process.

3.21 As the programme progresses, there would be merit in the department publishing regular updates on the outputs and outcomes of the programme, including information on individual projects. The department should also explore opportunities to use its website (or other channels such as social media) to assist in the achievement of the programme objective of ‘strengthening pathways to extend the results of rural R&D’, for example by publishing case studies to communicate project results or to publicise extension activities being undertaken by individual projects.

Has the department established a sound approach to programme evaluation?

The department developed an evaluation strategy early in the programme’s implementation, with an evaluation of programme achievements planned for year four (2018) and year eight (2022) of the programme. There is scope for the department to more clearly outline its approach to measuring performance against all programme objectives.

3.22 The department developed a programme Evaluation Plan early in programme’s implementation, with programme evaluations planned for year four (2017–18) and year eight (2021–22) of the programme.41 Funding has been set aside in the programme budget to conduct the first evaluation. The Evaluation Plan provides a sound basis for the department to implement evaluation activities. It outlines:

- planned evaluation activities;

- key evaluation questions—How well is the Rural R&D for Profit Programme meeting its objective? and How well is the Rural R&D for Profit Programme being implemented?; and

- the proposed evaluation methodology.

3.23 There is, however, scope for Agriculture to more clearly outline how the department intends to quantify the achievement of productivity and profitability improvements for primary producers. Further, there would be merit in the department addressing how it will measure the extent to which the programme has resulted in the delivery of ‘additional’ research, development and extension activities, which is one of the objectives established for the programme in the initial election policy commitment and which was subsequently reflected in the programme’s eligibility and assessment criteria.42

3.24 When developing the Evaluation Plan, Agriculture did not consult with the funding recipients (the RDCs). In addition, the department did not provide information to the RDCs about how their project data and project outcomes (to be self-evaluated by the funding recipients) are intended to inform the programme evaluations. There would be benefit in the department providing information to the programme’s funding recipients regarding planned programme evaluation activities, and the funded projects’ expected contributions towards these activities.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Entity responses

Appendix 2 Projects funded under the Rural R&D for Profit Programme (as at September 2016)

ROUND 1

|

Applicant |

Project |

Commonwealth grant funding (GST excl.) |

Applicant/partner contributions (GST excl.) |

|

Australian Pork Limited (APL) |

Waste to revenue: Novel fertilisers and feeds |

$862 693 |

$569 376 cash $569 000 in-kind |

|

Cotton Research and Development Corporation (CRDC) |

Smarter irrigation for profit |

$4 000 000 |

$3 435 000 cash $2 906 949 in-kind |

|

Dairy Australia Limited (DAL) |

Stimulating private sector extension in Australian agriculture to increase returns from R&D |

$1 595 000 |

$810 000 cash $785 000 in-kind |

|

Dairy Australia Limited (DAL) |

MIR for profit: integrating very large genomic and milk mid-infrared data to improve profitability of dairy cows |

$927 273 |

$518 182 cash $510 000 in-kind |

|

Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) |

Growing a profitable, innovative and collaborative Australian Yellowtail Kingfish aquaculture industry: Bringing ‘white’ fish to the market |

$3 000 000 |

$1 650 000 cash $1 400 000 in-kind |

|

Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (HIAL) |

Adaptive area-wide management of QFly using SIT: Guidelines for efficient and effective pest suppression and stakeholder adoption |

$2 350 000 |

$1 175 000 cash $1 175 000 in-kind |

|

Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (HIAL) |

Multi-scale monitoring tools for managing Australian tree crops—Industry meets innovation |

$3 428 248 |

$1 890 000 cash $1 538 248 in-kind |

|

Meat and Livestock Australia Limited (MLA) |

Fast-tracking and maximising the long-lasting benefits of weed biological control for farm productivity |

$1 897 918 |

$948 959 cash $948 959 in-kind |

|

Meat and Livestock Australia Limited (MLA) |

Market and consumer insights to drive food value chain innovation and growth |

$2 873 500 |

$3 440 000 cash $2 237 000 in-kind |

|

Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) |

Improved use of seasonal forecasting to increase farmer profitability |

$1 829 249 |

$900 973 cash $829 226 in-kind |

|

Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) |

Consolidating targeted and practical extension services for Australian Farmers and Fishers (The foundation to address Priority 4a) |

$815 000 |

$600 000 cash $300 000 in-kind |

|

Sugar Research Australia (SRA) |

A profitable future for Australian agriculture: Biorefineries for higher-value animal feeds, chemicals, and fuels |

$3 090 564 |

$1 545 282 cash $1 544 030 in-kind |

|

Total |

|

$26 669 445 |

$17 482 772 cash $14 743 412 in-kind $32 226 184 total applicant/partner contributions |

Source: Agriculture information. Further information on the projects can be found on the department’s website: <http://www.agriculture.gov.au/ag-farm-food/innovation/rural-research-development-for-profit> [accessed 18 August 2016].

ROUND 2

|

Applicant |

Project |

Commonwealth grant funding (GST excl.) |

Applicant/partner contributions (GST excl.) |

|

Australian Grape and Wine Authority (AGWA) |

Digital technologies for dynamic management of disease, stress and yield |

$2 987 635 |

$4 804 082 cash $5 721 593 in-kind |

|

Australian Grape and Wine Authority (AGWA) |

Mitigation of climate change impacts on the national wine industry by reduction in losses from controlled burns and wildfires and improvement in public land management |

$1 466 000 |

$1 466 000 cash $723 156 in-kind |

|

Australian Pork Limited (APL) |

Enhancing supply chain profitability through reporting and utilization of peri-mortem information by livestock producers |

$711 668 |

$754 905 cash $259 021 in-kind |

|

Cotton Research and Development Corporation (CRDC) |

More profit from nitrogen: Enhancing the nutrient use efficiency of intensive cropping and pasture systems |

$5 889 286 |

$4 170 652 cash $5 626 295 in-kind |

|

Cotton Research and Development Corporation (CRDC) |

Accelerating precision agriculture to decision agriculture |

$1 397 561 |

$750 000 cash $1 410 415 in-kind |

|

Dairy Australia Limited (DAL) |

Enhancing the profitability and productivity of livestock farming through virtual herding technology |

$2 600 000 |

$1 365 000 cash $1 871 805 in-kind |

|

Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) |

Easy-open oysters |

$236 275 |

$193 325 cash $57 950 in-kind |

|

Forest and Wood Products Australia (FWPA) |

Lifting farm gate profit through high value modular agroforestry |

$520 000 |

$260 000 cash $638 674 in-kind |

|

Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (HIAL) |

Advanced production systems for the temperate nut crop industries |

$5 000 000 |

$4 450 000 cash $808 470 in-kind |

|

Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (HIAL) |

National centre for post-harvest disinfestation research on Mediterranean fruit fly (Australian Medfly R&D Centre) |

$1 647 636 |

$1 655 746 cash $1 763 455 in-kind |

|

Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA) |

Phosphorus efficient pastures: delivering high nitrogen and water use efficiency, and reducing cost of production across Southern Australia |

$3 460 000 |

$1 730 000 cash $3 247 829 in-kind |

|

Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA) |

Advanced measurement technologies for globally competitive Australian meat |

$4 850 000 |

$4 255 000 cash $2 842 000 in-kind |

|

Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA) |

Improved surveillance, preparedness and return to trade for emergency animal disease incursions using FMD as model |

$5 869 968 |

$2 934 984 cash $2 934 984 in-kind |

|

Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) |

New biocontrol solutions for sustainable management of weed impacts to agricultural profitability |

$6 230 437 |

$3 179 818 cash $3 603 635 in-kind |

|

Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) |

Taking the Q (query) out of Q fever: Developing a better understanding of the drivers of Q fever spread in farmed ruminants |

$514 500 |

$735 000 cash $367 800 in-kind |

|

Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) |

Securing pollination for more productive agriculture: Guidelines for effective pollinator management and stakeholder adoption |

$5 255 000 |

$2 627 714 cash $5 227 563 in-kind |

|

Sugar Research Australia (SRA) |

Enhancing the sugar industry value chain by addressing mechanical harvest losses through research, technology and adoption |

$3 551 000 |

$1 925 000 cash $2 649 643 in-kind |

|

Total |

|

$ 52 186 966 |

$ 37 257 226 cash $ 39 754 288 in-kind $ 77 011 514 total applicant/partner contributions |

Source: Agriculture information. Further information on the projects can be found on the department’s website: <http://www.agriculture.gov.au/ag-farm-food/innovation/rural-research-development-for-profit> [accessed 18 August 2016].

Footnotes

1 The Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper was prepared by a Taskforce within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

2 RDCs were established to commission and manage R&D activities aimed at improving productivity, profitability and long‐term sustainability for Australia’s primary industries. The 15 RDCs cover the agriculture, fisheries and forestry industries. Five of these RDCs are Commonwealth statutory entities with boards of directors appointed by the Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources. The remaining 10 RDCs are industry-owned companies.

3 Other providers of rural R&D in Australia include the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Cooperative Research Centres; universities, Australian Government and state/territory government funded research programs, and private/industry researchers.

4 Since 2013, statutory RDCs have also been able to undertake marketing activities where industry requests such services and raises a marketing levy.

5 Productivity Commission, Rural Research and Development Corporations, February 2011, Commonwealth of Australia, pp. 23–26. Available from: <www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/rural-research/report/rural-research.pdf> [accessed 18 August 2016].

6 The enabling legislation for the statutory RDCs is the Primary Industries Research and Development Act 1989—with the exception of Wine Australia, which is established in separate legislation as it also performs a regulatory function. Each of the industry-owned RDCs is established under separate legislation.

7 As statutory funding agreements expire and are re-negotiated and agreed, the requirement for the Minister’s or Commonwealth’s endorsement of the RDC’s strategic plan is being introduced.

8 Further information on the Council is available from its website at: <http://www.ruralrdc.com.au/> [accessed 18 August 2016].

9 Hon. Barnaby Joyce MP, Minister for Agriculture, Media Release: $100 million in agricultural R&D keeps Aussie farmers at cutting edge, 13 May 2014.

10 Australian Government, Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper, July 2015, p. 12. Available from: <http://agwhitepaper.agriculture.gov.au/> [accessed 18 August 2016].

11 Rural R&D for Profit Programme website: <http://www.agriculture.gov.au/ag-farm-food/innovation/rural-research-development-for-profit> [accessed 18 August 2016].

12 The additional funding was included in the Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2015–16 (published in February 2016), as the White Paper announcement had occurred after the release of the 2015–16 Budget.

13 The 2015–16 Budget foreshadowed the expenditure of $25 million in 2018–19, and the 2016–17 Budget foreshadowed the expenditure of a further $25 million in 2019–20.

14 Agriculture advised that the administrative expenses for the second tranche of the programme ($100 million from 2018–19 to 2021–22) are yet to be determined.

15 For the two funding rounds conducted to September 2016, the department appointed an Independent Expert Panel to undertake the merit assessment of grant applications. Information on the membership of the panel is available on the programme website.

16 Department of Agriculture, Rural Research and Development for Profit programme: Round one applicant guidelines, October 2014, p. 4.

17 A list of the funded projects is provided at Appendix 2.