Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Design and Monitoring of the National Innovation and Science Agenda

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the design process and monitoring arrangements for the National Innovation and Science Agenda by the relevant entities.

Summary and recommendations

Background

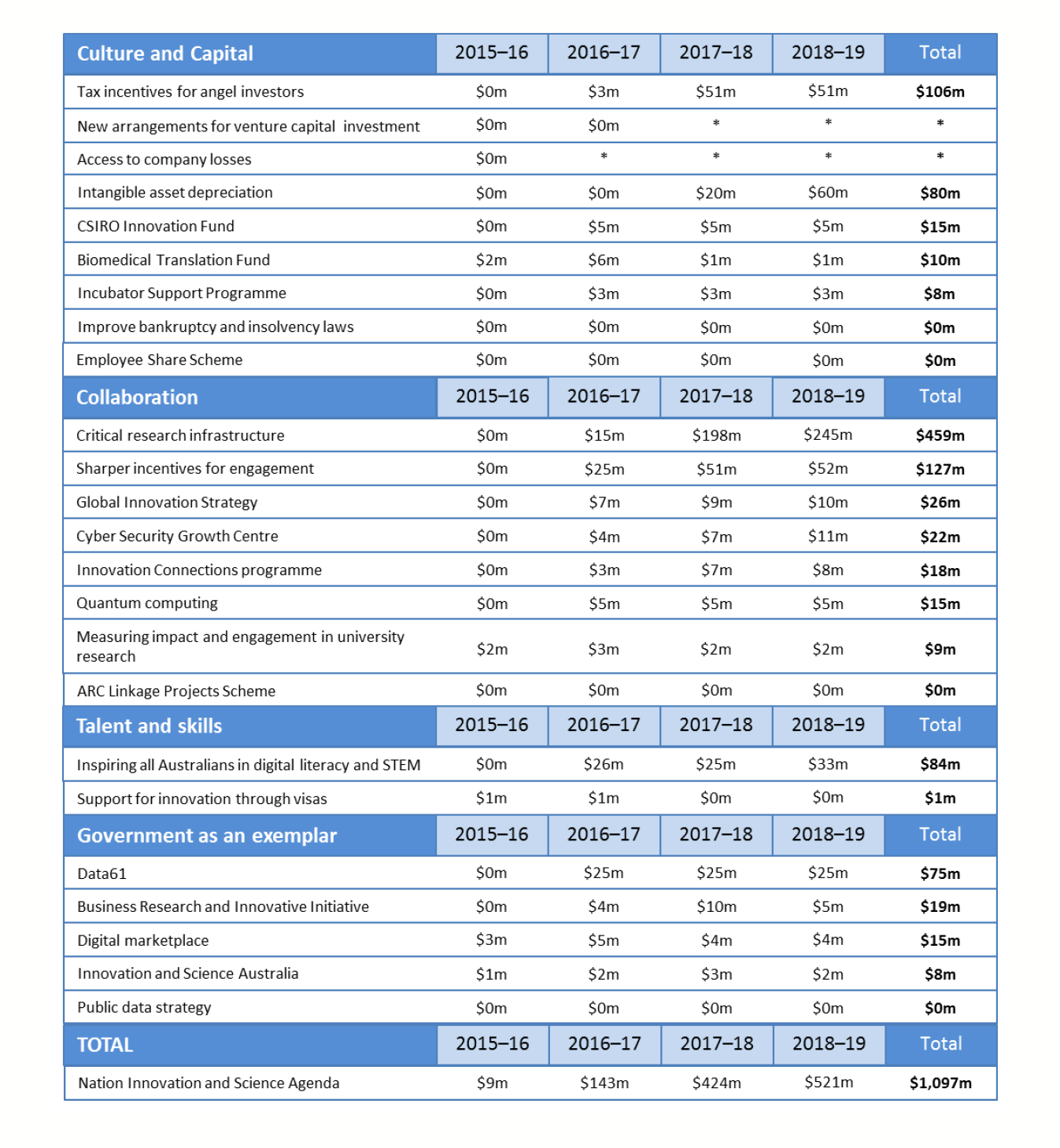

1. On 7 December 2015, the Prime Minister and the Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science announced the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA)—a policy statement on innovation and science, and a package of 24 measures costed at $1.1 billion over four years.1

2. The announcement of the NISA included the statement that:

Innovation and science are critical for Australia to deliver new sources of growth, maintain high-wage jobs and seize the next wave of economic prosperity.2

3. The 24 measures, which include grant programs, tax incentives, funding for research infrastructure, and initiatives to promote science, technology, engineering and mathematics, were framed around four main 'pillars': Culture and capital; Collaboration; Talent and skills; and Government as an exemplar.

4. The development of the Agenda was assisted by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and a Taskforce set up within PM&C, which received input from other entities. Nine portfolios are involved in implementing the Agenda, supported by a governance framework that includes central oversight by a Delivery Unit operating in the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (Industry) and an interdepartmental implementation committee. An independent body, Innovation and Science Australia (ISA), was established under the NISA to provide strategic advice to government on the broader innovation system.3

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design process and monitoring arrangements for the NISA by the relevant entities.

6. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted three high-level criteria:

- Was sound and timely policy advice provided to government to help inform the development of the Agenda?

- Were appropriate planning and governance arrangements established to support the implementation of the Agenda?

- Is the implementation of the Agenda, and are outcomes to date, being effectively monitored and reported on?

Conclusion

7. The design process for the National Innovation and Science Agenda allowed the Government to make decisions within short timeframes, and the monitoring arrangements have, in most respects, been effective. The quality of advice to government could have been improved by a better articulation of the evidence base and likely impacts of the proposals, including the likely net benefits of the overall $1.1. billion in proposed expenditure.

8. The design process for the NISA was timely in supporting a government decision-making process. It was aided by active management by PM&C and the Taskforce, and drew on previous reviews and input from a range of entities. In addition to sector level material, some guidance on the development of policy advice was available within PM&C and Industry, but it was not evident how this material was applied to the work of the Taskforce or to the input provided by entities. The ANAO observed variability in the quality of the advice provided. The better developed proposals included a clear articulation of the evidence base and likely impacts of the proposals and also indicated when the proposal would be reviewed or evaluated. However, much of the advice was general in nature and did not present quantitative or in-depth analysis of problems, expected impacts or how outcomes would be measured.

9. Suitable planning and governance arrangements for the Agenda were established early in the post-announcement period to support most aspects of implementation. Some elements of the evaluation framework were delayed, including confirmation that entities had identified baseline data and robust evidence collection systems. Current indications are that impact assessment will be affected by variability in the quality of entities' performance measures and data collection systems. Assessing the impact of the package as a whole is also likely to be challenging.

10. Monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Agenda have, in most respects, been effective. Regular progress reports covering all measures and all responsible entities have been provided to government and other relevant stakeholders. The advice provided drew attention to various implementation risks, including not meeting the publicly announced timeframes. However, in a number of cases, the accompanying 'traffic light' ratings provided a more optimistic view of progress than was supported by the evidence. This included seven measures that did not meet the publicly announced timeframe but were not rated appropriately.

Supporting findings

Effectiveness of the policy design process

11. In response to the Prime Minister indicating the importance of innovation to the Government's agenda, PM&C provided policy advice on a new innovation agenda. PM&C was responsive in meeting the timeframes agreed with government for providing advice on the package of proposed measures. In the time available, a number of important matters were not addressed in the advice to government, including implementation risks, governance, and evaluation arrangements.

12. The better developed proposals articulated: the evidence base; the likely impacts of the proposals; and when the proposal would be reviewed or evaluated. The ANAO observed that much of the advice was general in nature and did not present quantitative or in-depth analysis of problems, expected impacts or how outcomes would be measured. A number of the proposals that involved significant expenditure aimed at transforming parts of the innovation system relied on assertions rather than evidence. There was no specific guidance on the standard of evidence required to support individual measures or the package as whole.

13. Consultation in the design phase was adequate given the short timeframes involved and given that a number of the proposed measures had been canvassed in earlier consultation processes.

Planning and governance arrangements

14. An implementation plan was developed for the NISA in the months following the launch of the Agenda. The implementation plan addressed relevant implementation principles, and was prepared in the timeframe set by government (1 March 2016), some four months before the first measures were due to be implemented.

15. Suitable governance arrangements were established to support implementation of the Agenda. Specific oversight bodies were established promptly, and operated within a governance framework for the Government's broader innovation agenda.

16. Oversight arrangements for stakeholder consultation were appropriate. Under the NISA Implementation Plan, the primary responsibility for stakeholder consultation was assigned to the lead entity for each measure. The Delivery Unit explored whether joint consultation sessions would be beneficial, but no specific need for structured consultation was identified. Lead entities have reported measure-specific consultation to the Delivery Unit.

17. An evaluation framework was developed but not in a timely or fully effective manner. Limited advice was provided to government during the design process about the specific impacts of the Agenda, and how or when they were to be measured. While evaluation arrangements were progressively developed post-announcement, there were delays and issues associated with the identification of suitable performance measures and data sources.

Monitoring and reporting on progress

18. Effective monitoring arrangements were established, which covered all relevant entities and all measures agreed by government. The arrangements centred on regular progress reports to government and other stakeholders. The reports were compiled by the Delivery Unit and underpinned by information provided by lead entities for each measure.

19. Progress reporting has been timely and, in most respects, accurate. The oversight bodies provided regular and generally clear advice to government on the status of measures and the risks of not meeting milestones or announced timeframes. In some cases, the 'traffic light' ratings used to signal progress did not appropriately match the level of progress. This included seven measures that did not meet the announced timeframe but were rated as either 'on track with emerging issues' or 'on track'.

20. Efforts have been made by Industry to identify early outcomes for measures that have been implemented. The key finding of the post-commencement review is that it is too early to assess whether intended outcomes are being achieved.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.26

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science review and update their policy development guidance and training materials so that they:

- are fit-for-purpose for the range of activities undertaken, including cross-entity taskforces;

- clearly articulate an acceptable standard of analysis and evidence; and

- include mechanisms to provide assurance that the guidelines are consistently applied.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet's response: Agreed.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science's response: Agreed in part.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.34

The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science finalise the evaluation strategy for the National Innovation and Science Agenda, and establish formal monitoring arrangements with relevant entities, so that the results of evaluation activities can be used to inform advice to government on future measures and the continuation of existing measures.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science's response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

The summary response from each entity is provided below, with full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) welcomes the ANAO's willingness to examine the NISA and finding that the NISA design process was timely in supporting the Government's decision-making process and that monitoring and reporting arrangements have, in most respects, been effective.

PM&C strives to provide a consistently high standard of advice to the Government, and has a range of frameworks to assist officials within PM&C and across the Australian Public Service (APS), including, but not limited to: the Cabinet Handbook, the Australian Government Guide to Regulation, the Legislation Handbook and a range of internal PM&C guidance for policy officers, including a disciplined policy design methodology.

While the framework materials managed by PM&C are periodically reviewed and updated to ensure they remain fit for purpose, the ANAO's findings are a valuable reinforcement of the position the Secretary of PM&C has been advancing. There is an ongoing need to test and refine our policy frameworks to ensure they clearly articulate an acceptable standard of analysis and evidence, and we need to continually work to promote good policy development practice within PM&C and across the APS. There is also an opportunity for PM&C to better draw together framework materials and improve their visibility and accessibility across the APS.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science notes the ANAO's audit of the design and monitoring arrangements for the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA). We note the audit's findings that departments responded in a timely manner to support decision-making on an area of priority for the Government.

The development of the NISA package built upon a substantial body of advice that had been assembled by agencies and provided to ministers over a substantial period of time in the lead up to the Government's consideration of NISA. The policy development process coordinated by the NISA Taskforce (established within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) built upon that work and drew on further evidence as necessary to support the Government to launch a package of initiatives to stimulate innovation, invest further in Australia's science capabilities, increase skills in Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths, and foster innovation in government procurement and service delivery. Ministers were closely involved throughout the development of the package and the performance of the public service was publicly commended by the Government. However, noting the audit's findings, we will examine opportunities to further improve our policy guidance and associated training material.

The monitoring and reporting arrangements put in place to support implementation represented a novel and highly effective method of driving implementation across portfolios while also providing assurance to the Government. This approach was strengthened by the establishment of a senior interdepartmental committee led by an Independent Chair, and the formation of a dedicated delivery unit within the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science.

We welcome the audit's acknowledgement that monitoring arrangements were effective and that regular progress reports provided to the Government drew attention to areas of implementation risk. Notwithstanding the ANAO's view that the traffic light ratings were not sufficiently defined, the process supported ministerial consideration of areas warranting attention and the reports included detailed information through which the Government could satisfy itself of implementation progress. Advice was provided regularly through progress reports, correspondence from the Independent Chair and departmental briefing. Verbal briefing was also a substantial element of reporting arrangements over the first six months. These oversight arrangements also resulted in a coordinated approach to the evaluation of NISA measures.

Office of Innovation and Science Australia

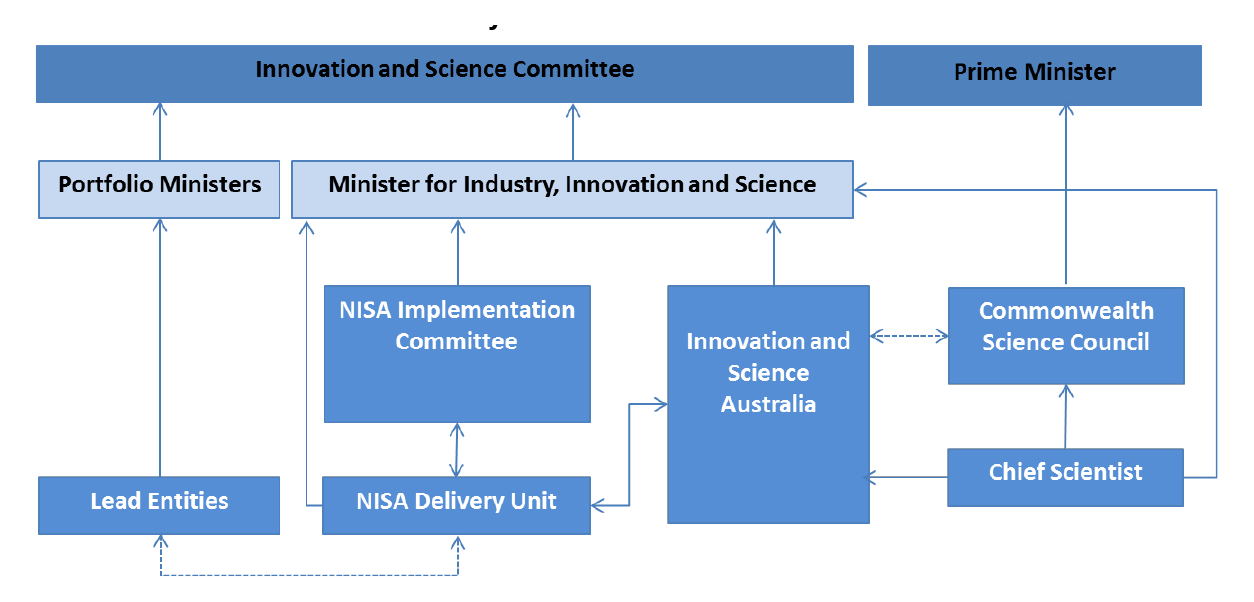

The Office of Innovation and Science Australia provided comments on an extract of the proposed report and requested adjustments to Figure 1.2 Overview of the governance arrangements for the NISA and Australia's broader innovation system. The suggested changes included an adjustment to more accurately show the relationship between the Chief Scientist and the Innovation and Science Australia (ISA), as well as removing a reference to the Office of Innovation and Science.

Key learnings and opportunities for improvement for Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Commonwealth entities when designing, or monitoring the implementation of, a major policy or initiative.

Advice to government

Review and evaluation

Reporting on progress

1. Background

The National Innovation and Science Agenda

1.1 On 7 December 2015, the Prime Minister and the Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science announced the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA)—a policy statement on innovation and science, and a package of 24 measures costed at $1.1 billion over four years.4 Some $459 million of this funding was allocated towards research infrastructure.5

1.2 The announcement of the Agenda included the following statement:

Innovation and science are critical for Australia to deliver new sources of growth, maintain high-wage jobs and seize the next wave of economic prosperity. Innovation is about new and existing businesses creating new products, processes and business models. It is also about creating a culture that backs good ideas and learns from taking risks and making mistakes.6

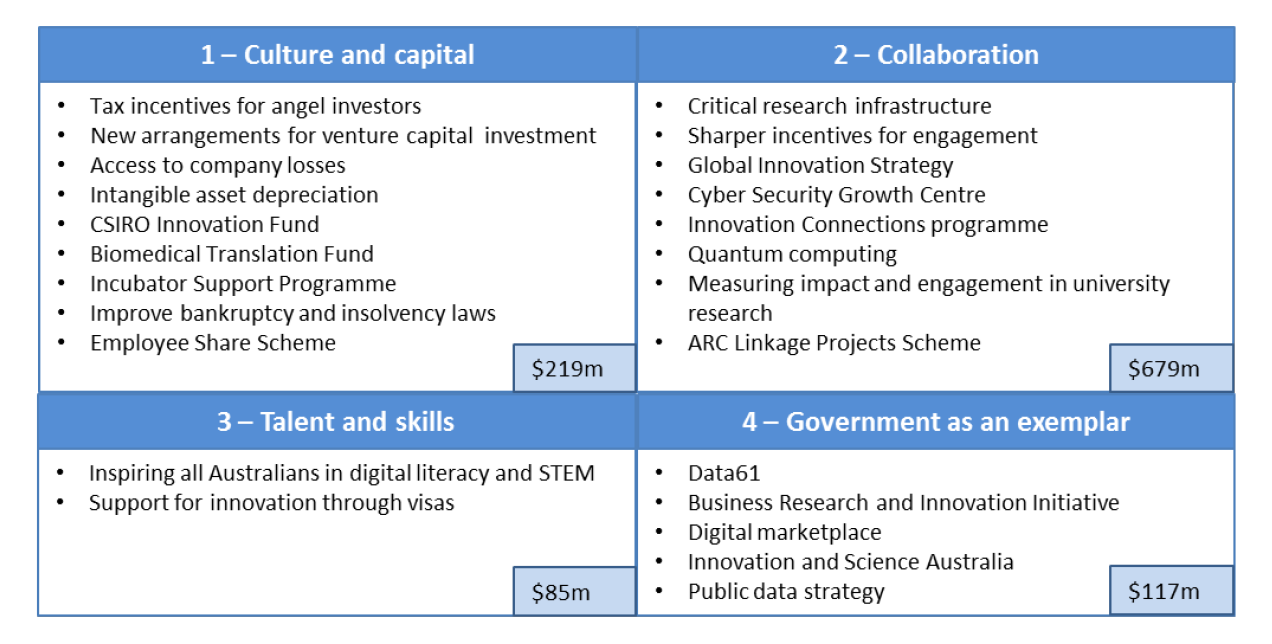

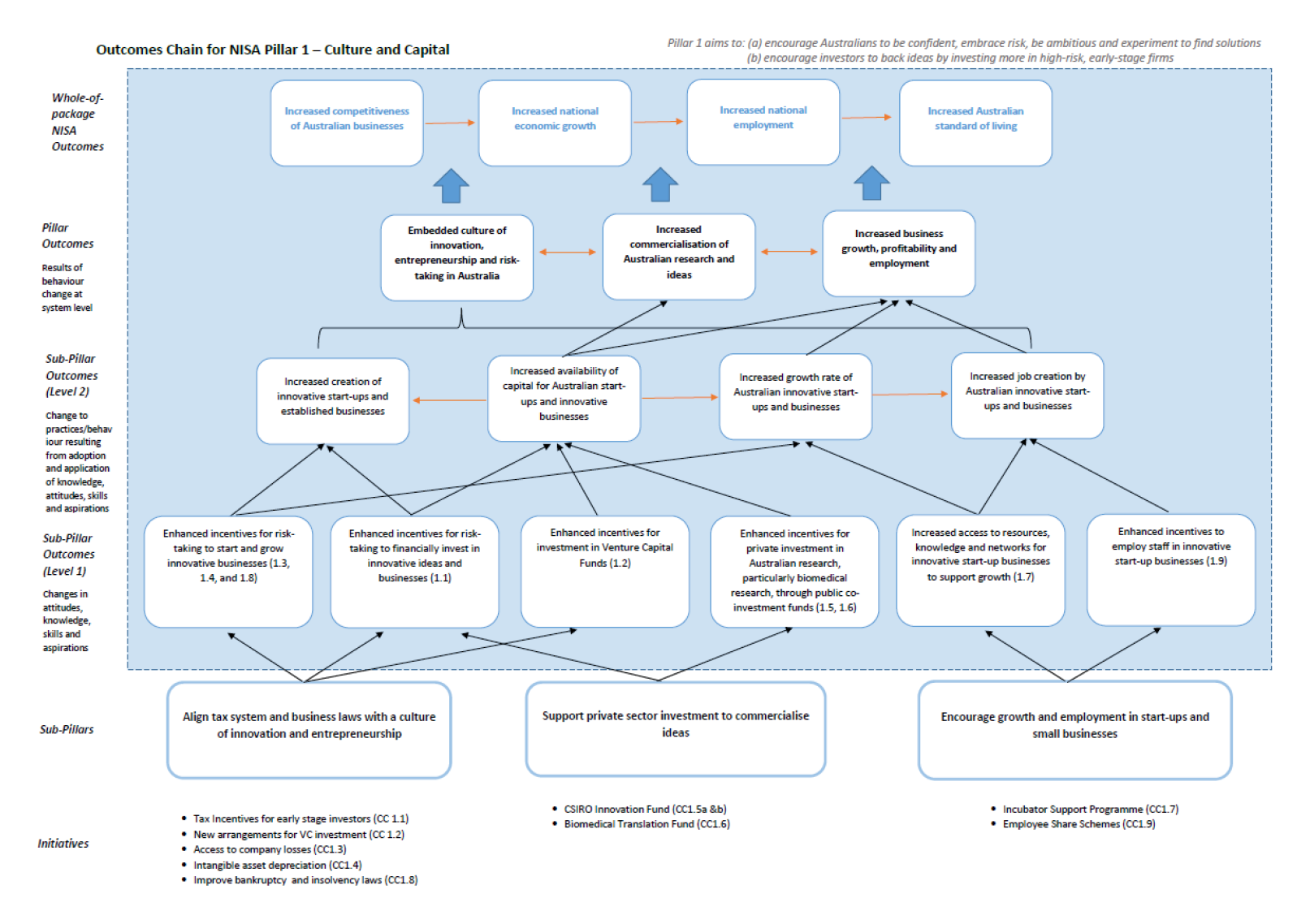

1.3 The NISA measures—which include grant programs, tax incentives, education initiatives, and data and digital changes—were framed around four main focus areas or ‘pillars’: Culture and capital; Collaboration; Talent and skills; and Government as an exemplar (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: NISA measures and funding by pillar

Source: ANAO adaption of information from the National Innovation and Science Agenda, available from www.innovation.gov.au.

1.4 The announcement of the NISA, which had the tag line ‘Welcome to the ideas boom’, was followed by a communications campaign, which ran from 7 December 2015 until 9 May 2016.7 The campaign aimed to create awareness of the NISA, and drive cultural change.

Design, monitoring and implementation arrangements

1.5 The process to design, monitor and implement the NISA involved multiple Australian Government entities and other stakeholders. At the design stage, advice was provided to government by:

- the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) in its capacity as advisor to the Prime Minister;

- a Taskforce established within PM&C, which operated from September to December 2015; and

- a range of other entities that provided proposals for consideration in the NISA package.

1.6 Nine portfolios, with 16 different entities, are involved in implementing the 24 NISA measures8—as the ‘lead’, ‘partner’ or ‘engaged’ entity (as listed at Appendix 3). A governance framework was established to oversee implementation of the NISA and Australia’s broader innovation system (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Overview of the governance arrangements for the NISA and Australia’s broader innovation system

Source: ANAO analysis of documents provided by Industry.

1.7 The governance framework includes specific oversight bodies for the NISA—an interdepartmental implementation committee (NISAIC) and a Delivery Unit, which report to the Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science (Industry Minister).9 Broader oversight is provided by:

- an independent statutory board, Innovation and Science Australia (ISA)10; and

- the Commonwealth Science Council, which is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes Australia’s Chief Scientist.

Related Australian Government initiatives

1.8 The NISA follows on from the 2014 Industry Innovation and Competitiveness Agenda11, and builds on a number of existing measures and programs including:

- the establishment of Industry Growth Centres to drive innovation, productivity and competitiveness in certain sectors, such as advanced manufacturing; and

- the Entrepreneurs’ Programme, which offers businesses a range of support (such as advice and facilitation services) to improve competitiveness and productivity.

1.9 In 2016–17, Australian Government spending on research and development related to innovation and science was expected to exceed $10.1 billion.12

Reviews of innovation and science programs

1.10 At the time the NISA was developed, there were a number of reviews, inquiries and discussion papers completed or underway on aspects of Australia’s innovation system, examining:

- the role of science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) in boosting productivity, creating jobs, enhancing competitiveness and growing the economy13;

- how to boost the commercial returns from research14;

- collaboration between business and researchers in the Cooperative Research Centres Programme15;

- funding for National Research Infrastructure;16;

- research policy and funding arrangements17; and

- the challenges to Australian industries and jobs posed by increasing global competition.18

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.11 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the design process and monitoring arrangements for the NISA by the relevant entities.

1.12 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted three high-level criteria:

- Was sound and timely policy advice provided to government to help inform the development of the Agenda?

- Were appropriate planning and governance arrangements established to support the implementation of the Agenda?

- Is the implementation of the Agenda, and are outcomes to date, being effectively monitored and reported on?

Scope

1.13 The scope of the audit covered the centralised design and monitoring arrangements for the NISA; that is:

- the role of PM&C and the Taskforce in providing advice to government on the design of the NISA in the period from September to December 2015; and

- the establishment and operation of the specific oversight bodies for the NISA—Interdepartmental Implementation Committee and the Delivery Unit—in relation to monitoring, oversight and reporting arrangements in the period from December 2015 to June 2017.

1.14 The audit also examined the role of Innovation and Science Australia and the Commonwealth Science Council where either of these bodies provided input to the design of the NISA or had a role in monitoring arrangements.

1.15 In relation to the design process, the audit did not examine the policy advice provided to government by other entities, unless such advice was included in the overarching decision-making process for the NISA in the period from September to December 2015.

1.16 The audit examined implementation planning and governance arrangements as well as implementation monitoring and reporting by the oversight bodies. It did not examine the implementation of NISA measures by the relevant entities.

Methodology

1.17 The methodology applied a clear distinction between the role of government and the role of Australian Public Service entities. Establishing policy is the responsibility of government, and entities provide advice on it. While policy advising is an important function of entities, governments can seek advice from other sources.

1.18 Entities provide policy advice to Ministers to help ensure that government decisions are appropriately supported and informed. Policy advising outputs include briefing documents and submissions provided to government. This audit focused on policy advice outputs and the processes to deliver them. The audit did not include examination of the merits of a particular policy position or the decisions made by Ministers or the Government.

1.19 Three principal methods were used to collect and analyse audit evidence:

- review of key documents against: requirements set by entities; relevant Commonwealth policies and guidance materials; and recognised best practices;

- testing entity assertions through analysis of primary documents and other relevant material; and

- interviewing key personnel, including on matters involving judgement or where entity records were inadequate.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $319,000.

1.21 The team members for this audit were Stephen Cull, Emily Drown, Ruth Cully and Brian Boyd.

2. Effectiveness of the policy design process

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the Taskforce set up within PM&C provided sound and timely advice to government to help inform the design of the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA). The audit does not comment on the policy decisions made by government.

Conclusion

The design process for the NISA was timely in supporting a government decision-making process. It was aided by active management by PM&C and the Taskforce, and drew on previous reviews and input from a range of entities. In addition to sector level material, some guidance on the development of policy advice was available within PM&C and Industry, but it was not evident how this material was applied to the work of the Taskforce or to the input provided by entities. The ANAO observed variability in the quality of the advice provided. The better developed proposals included a clear articulation of the evidence base and likely impacts of the proposals and also indicated when the proposal would be reviewed or evaluated. However, much of the advice was general in nature and did not present quantitative or in-depth analysis of problems, expected impacts or how outcomes would be measured.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that PM&C and Industry review and update their policy development guidance and training materials so that they: are fit-for-purpose for the range of activities undertaken, including cross-entity taskforces; clearly articulate an acceptable standard of analysis and evidence; and include mechanisms to provide assurance that the guidelines are consistently applied.

Were officers responsive in providing initial advice and options?

In response to the Prime Minister indicating the importance of innovation to the Government’s agenda, PM&C provided policy advice on a new innovation agenda. PM&C was responsive in meeting the timeframes agreed with government for providing advice on the package of proposed measures. In the time available, a number of important matters were not addressed in the advice to government, including implementation risks, governance, and evaluation arrangements.

The origin of the National Innovation and Science Agenda

2.1 The Prime Minister had made statements that innovation was at the centre of the Government’s agenda.19 In response, PM&C proposed the development of a Prime Ministerial statement and a specific innovation package.

2.2 PM&C recommended that an innovation package be developed for consideration by the end of 2015, stating that such a package could be fundamental in transforming the economy and for addressing risk aversion and business culture. This timeframe was subsequently agreed by government. The Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science (Industry Minister) was tasked by the Prime Minister with developing an innovation statement and package by the end of 2015.

2.3 The rationale for delivering a new innovation agenda in this timeframe was not provided in PM&C’s initial advice or in subsequent advice to government. Limited or no advice was provided to government during the design process on a range of implementation matters for the Agenda as a whole including: implementation risks, governance, and evaluation arrangements. It was unclear how the timeframe proposed by PM&C took account of the department’s own better practice guidance on the successful implementation of policy initiatives, which emphasises that implementation should be considered at every stage of policy development.20 Providing advice on these matters during the main decision-making process, before funding was determined, would have aided the management of risks associated with implementing a sizable cross-portfolio program.

2.4 The initial advice provided by PM&C noted that there were several reviews and reports that could be synthesized down to a package of a few key high-impact, pro-growth initiatives. The advice highlighted the four areas PM&C considered to have the biggest problems and where actions could have the biggest impacts, which were broadly endorsed by government and reflected in the four pillars in the NISA. Other than drawing attention to existing information, reports and reviews, the initial advice did not indicate the evidence base to support the changes proposed or provide any further elaboration on how a new agenda would ‘transform’ the economy, having regard to, for example:

- the effectiveness of existing government expenditure in support of science, research and innovation—which included around $3 billion in funding21 to the private sector to encourage investment in new products, services and processes;

- the effectiveness of the 2014 Industry Innovation and Competitiveness Agenda, which included a number of measures intended to foster innovation and entrepreneurship; and

- the broader role of tax and regulatory systems in encouraging or distorting the investment environment for innovation.

An iterative process to design the package

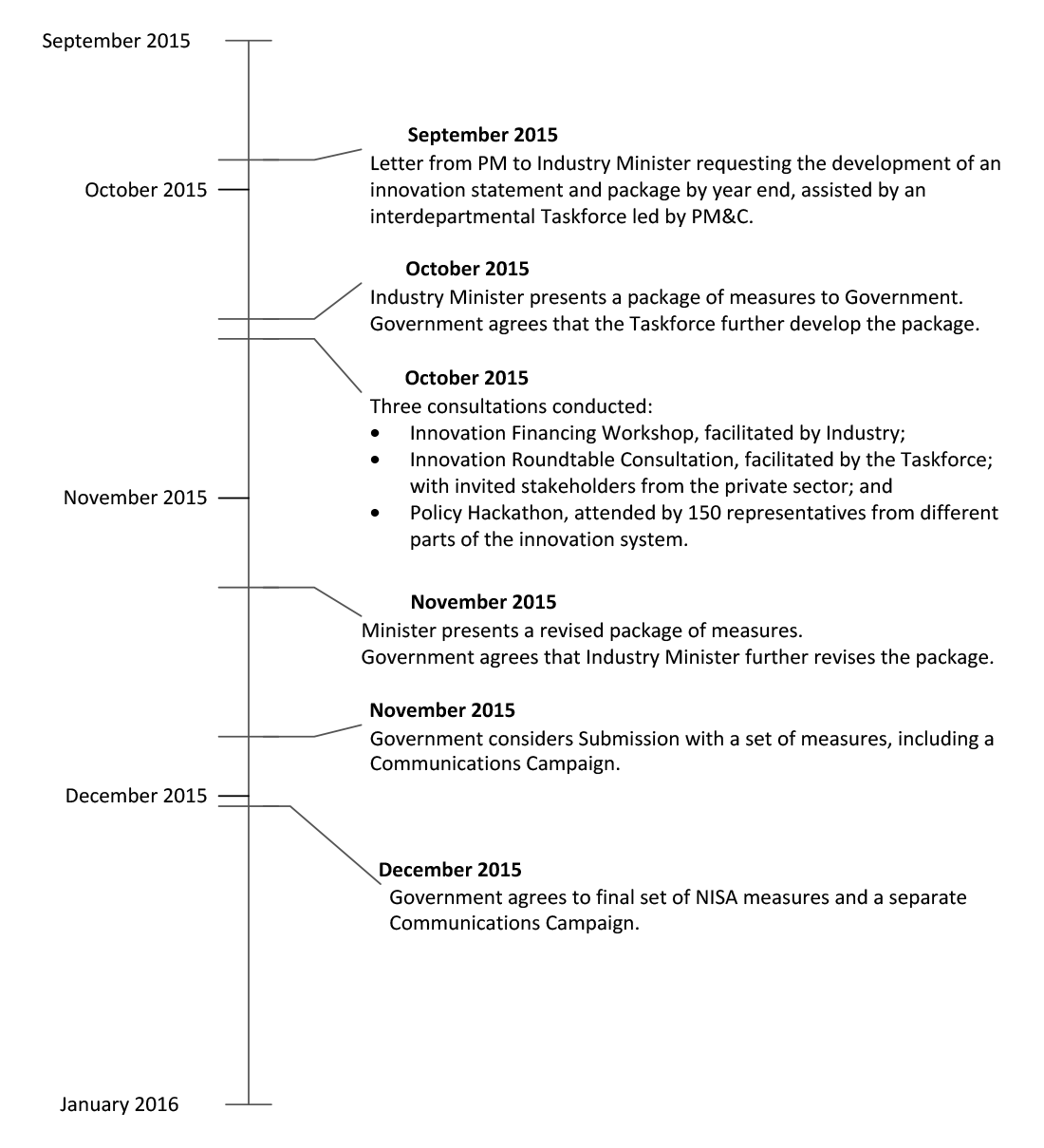

2.5 Following the establishment of the Taskforce to support the Industry Minister to develop a new innovation agenda and help to coordinate efforts across relevant portfolios, options for the Government’s consideration were identified, assessed and compared through an iterative process (Figure 2.1). Some targeted consultation was also undertaken during this period. A threshold question asked early in this process was whether the agenda should include science or be limited to innovation. PM&C’s advice was that science should be confirmed as part of the agenda, which was accepted.

Figure 2.1: Timeline of the development process for the NISA

Source: ANAO analysis of information provided by PM&C.

2.6 The Taskforce sought the Government’s approval for a package of measures on three separate occasions prior to the final decision on the NISA. Over a three month period, the Taskforce worked actively with Government to develop the final package of 24 measures.22 The process established by PM&C to assist the Industry Minister to develop the agenda resulted in the agreed timeframe being met.

Were policy problems and expected impacts clearly identified and supported by sufficient analysis and evidence?

The better developed proposals articulated: the evidence base; the likely impacts of the proposals; and when the proposal would be reviewed or evaluated. The ANAO observed that much of the advice was general in nature and did not present quantitative or in-depth analysis of problems, expected impacts or how outcomes would be measured. A number of the proposals that involved significant expenditure aimed at transforming parts of the innovation system relied on assertions rather than evidence. There was no specific guidance on the standard of evidence required to support individual measures or the package as whole.

Framework for providing advice

2.7 The framework that was in place to support the development of policy advice on the NISA included some general requirements and guidance on working with government, as set out in: the APS Values23 and Directions issued by the APS Commissioner24; and in policy manuals, handbooks and circulars.25 For instance, the APS Value of ‘Impartial’ requires that advice to government is ‘frank, honest, timely and based on the best available evidence’.26

2.8 There was also some general guidance (in templates) on the matters to be focussed on by entities in developing policy proposals for government consideration. This included addressing:

- what the policy problem is and why the Commonwealth should intervene;

- what the expected outcome(s) are and how the proposal will achieve them; and

- how the proposal’s progress and success in delivering the outcomes will be measured.27

2.9 PM&C and Industry have also developed guidance and/or training materials on the development of policy advice. It was not evident, however, how this guidance and training material was applied to the work of the Taskforce or to the policy proposals submitted by the contributing entities.

2.10 The available guidance material did not articulate the standard of analysis and evidence that would be appropriate, having regard to the scale of the expenditure and expected economic impacts.28 The evidence base was largely a matter of judgement by the responsible entities, as mediated through the iterative decision-making process with government. As well, the roles and responsibilities of PM&C, the Taskforce and entities in respect to the quality of the advice provided to government were not documented.29

2.11 The importance of providing quality advice has been highlighted in Professor Peter Shergold’s independent review of government processes for implementing large programs and projects.30 The report observes that ‘Good advice is factually accurate and backed by evidence. It presents proposals based upon considered interpretation of alternative viewpoints and often reflects multiple perspectives.’31 The report concludes that ‘Public service advice is vital to good government and, to this end, Secretaries should be held accountable for the quality of advice provided to ministers by their departments’.32 Effective accountability would usually require an assessment/guidance framework being established setting clear expectations of performance, in this case as to what good quality advice looks like. Such frameworks are the norm in most areas of government activity33 where sector wide guidance is typically supported by agency specific frameworks.

2.12 An example of a specific framework is that produced by the New Zealand Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (see https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project/policy-improveme…). Its Policy Quality Framework is one of three improvement frameworks co-designed for and by the policy community in New Zealand to help government agencies improve their policy quality and capability. It seeks to help decision makers decide what to do by providing them with advice that is clear about the problem or opportunity, setting out all the available evidence, and presenting options that balance what is desirable, possible and cost-effective. The New Zealand framework describes the key characteristics of quality policy advice, as well as the ‘enablers’ of great advice. It includes a range of tools to assist practitioners to review and improve policy quality.

2.13 The ANAO examined whether individual proposals addressed the three matters outlined above in paragraph 2.8. The ANAO also examined whether the evidence base presented to government was appropriate and sufficient, taking into account the materiality of the expenditure and the recognised importance of ‘evidence-based’ approaches to policy development.34

Evidence base for the package and the four pillars

2.14 The Taskforce used a model to depict the policy case for change, which showed the relationship between four elements:

- Context—the broad imperatives for change and opportunities across the economy;

- Vision—how Australia would look after positive change in each of the four identified pillars of the innovation system;

- Barriers—to the achievement of the vision (see Box 1); and

- Initial actions—that can be taken to address the barriers and achieve the vision.

|

Box 1: Barriers identified by the Taskforce (September–October 2015) |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of information provided by PM&C.

2.15 The model did not identify the overarching outcomes being sought for the broader economy. These were outlined in the final advice to government and included increasing productivity and diversifying the economy.

2.16 The policy logic that can be inferred from this model is that: if the proposed actions are taken, they will reduce the barriers, which will move Australia towards the vision, which in turn will help achieve the objective of increasing productivity and diversifying the economy.

Evidence that the four pillars were the major barriers to innovation

2.17 The Taskforce’s advice to government provided limited evidence as to why these four areas were the major barriers in Australia’s innovation system. For instance, for ‘Culture and capital’, there was no further evidence presented to support the statement that there is currently a low appetite for risk in Australia.35 There was also no further analysis on where any specific gaps or problems were across the economy in respect to ‘Talent and skills’.

2.18 Without direct evidence of the nature and size of these barriers, and a defined baseline, it is not clear how success would be measured. For the ‘Collaboration’ barrier, the direction of change was clear: an improvement in Australia’s OECD ranking for research/industry collaboration. Nevertheless, there was no indication of what higher ranking was being sought or the practical implications of a higher ranking on the economy.

2.19 Industry advised the ANAO that the barriers identified in the innovation system at the time the NISA was being considered were the summation of extensive research and consultations. PM&C and Industry also advised the ANAO that there had been a long policy development process on innovation and consequently the Government did not come to the development of the NISA without any knowledge. Elaborating on this point, PM&C advised the ANAO that, in some cases over many years, Ministers would have formed views from previous reviews and from discussions with a wide range of stakeholders; and, in addition, departments would have briefed Ministers in more detail over an extended period.

Analysis of expected impacts

2.20 In June 2017, PM&C advised the ANAO that the size of the NISA package was too small, even in aggregate, for an economy-wide modelling or analytical framework to register an economic impact beyond the materiality thresholds used by the Treasury (which is rounded to the nearest quarter percentage point of Gross Domestic Product). PM&C further advised the ANAO that it is Treasury’s advice that it would be hard to come up with an authoritative way of modelling many of the measures given the disparate nature of the measures in the package. The Taskforce’s advice to government at the time the NISA was being developed therefore did not include any modelling, forecasting or other analysis on the expected impacts of the NISA with respect to its ultimate purposes of improving the economy, for example, by increasing productivity.

2.21 No advice on the measurement difficulties was provided to government when NISA was being designed. Had this been done, it may have assisted in setting expectations about the NISA’s likely impacts.

Evidence base for the measures

2.22 In the final advice to government, each measure was presented in the prescribed format, which comprised:

- a description of the proposal;

- a policy case;

- implementation and delivery considerations; and

- regulatory impact (where relevant).

2.23 The format did not require explicit identification of the policy problem, expected outcomes, or how they would be measured. Entities had discretion on how to address these matters in the relevant sections of the proposal; and as previously noted (paragraph 2.10) there was no specific guidance on the standard of evidence that would be appropriate. These limitations made it difficult to determine whether policy problems and expected impacts were clearly identified and supported by sufficient analysis and evidence.

2.24 The ANAO observed variability in the quality and depth of the advice provided across the final set of proposals presented to government. The better developed proposals:

- contextualised the nature and extent of the problem, or acknowledged the limitations of the evidence base;

- included specific evidence rather than relying on assertions, including references to previous reviews or inquiries that had been undertaken36;

- proposed measures to mitigate identified risks, including ex ante and ex post reviews;

- provided a rationale for government intervention;

- described the linkage to the relevant pillar and high-level outcomes;

- indicated when the proposal would be reviewed or evaluated.

2.25 However, much of the advice provided was general in nature and did not present quantitative or in-depth analysis of problems, expected impacts or how outcomes would be measured. A number of the proposals that involved significant expenditure aimed at transforming parts of the innovation system relied on assertions rather than evidence. In many cases, there was also a lack of specificity in the outcomes or expected impacts being sought, making it difficult to determine how success would be measured.

Recommendation no.1

2.26 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science review and update their policy development guidance and training materials so that they:

- are fit-for-purpose for the range of activities undertaken, including cross-entity taskforces;

- clearly articulate an acceptable standard of analysis and evidence; and

- include mechanisms to provide assurance that the guidelines are consistently applied.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet response: Agreed.

2.27 The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) supports the recommendation and agrees with the need for policy to be based on robust evidence and analysis. There is an ongoing need to test and refine our policy frameworks to ensure they clearly articulate an acceptable standard of analysis and evidence, and we need to continually work to promote good policy development practice within PM&C and across the APS. There is also an opportunity for PM&C to better draw together framework materials and improve their visibility and accessibility across the Australian Public Service.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science response: Agreed in part.

2.28 The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science agrees in part with the recommendation. The Department has well-established policy frameworks that provide consistently high quality advice to its ministers and the Government more broadly within robust accountability frameworks. We note that the development of the NISA was undertaken consistent with established policy development practices and built upon and complemented other advice. This process was consistent with many others in that proposals were iterated over the policy development lifecycle, taking into account views of key stakeholders and government decisions.

2.29 The Department’s contribution properly reflected expert advice from within this portfolio and drew upon available evidence as necessary to support the Government’s decision-making within the required timeframes and process agreed by ministers. The policy process was subject to close ministerial scrutiny, consistent with Cabinet decision-making, and the performance of the public service was publicly commended by the Government. Wherever there are opportunities to improve our processes we seek to do so, and the Department will examine its policy development guidance and associated training materials in the light of the ANAO’s findings.

Was adequate consultation undertaken?

Consultation in the design phase was adequate given the short timeframes involved and given that a number of the proposed measures had been canvassed in earlier consultation processes.

Targeted consultation

2.30 In PM&C’s initial advice to the Prime Minister in September 2015, officers suggested that stakeholder consultation would be important but needed to be well-targeted. This approach was endorsed by government.

2.31 In the period from September to December 2015, when the NISA was being developed, some targeted consultation was undertaken. Three consultations occurred in October 2015:

- an innovation financing workshop facilitated by Industry, in which participants from government and industry discussed a range of topics including: equity co-investment initiatives; encouraging angel investment; encouraging corporate support and investment; and encouraging institutional finance investment, particularly superannuation;

- an Innovation Roundtable held in Sydney involving business groups and the tertiary education sector, its purpose to hear the views and concerns of invitees about improving innovation in Australia; and

- a ‘Policy Hackathon’ in which around 150 representatives from different parts of the innovation system developed ideas in 10 policy areas (for example, Corporate Innovation), which were made publicly available on the PolicyHack website (www.policyhack.com.au).

2.32 The views of the Commonwealth Science Council were also sought on the NISA at its meeting on 21 October 2015. The Prime Minister and Industry Minister outlined the Government’s position on innovation and science, and described key themes being examined in the proposed innovation and science agenda. The Chief Scientist was invited to outline potential elements in that agenda. The Council agreed that the themes described by the Industry Minister were consistent with the elements presented by the Chief Scientist and recommended that the Government urgently develop a comprehensive and whole-of-government National Innovation and Science Agenda.37

2.33 The final decision-making material prepared for government outlined a range of stakeholder views, including key issues raised during the Innovation Roundtable.38 The advice stated that there had been a positive reaction across the community and industry to the Government’s focus on innovation and science.

2.34 The need for further stakeholder consultation during the implementation process was identified in a number of the proposed NISA measures. Some additional consultation occurred for specific measures, including several tax measures.39 In some cases, these consultation processes indicate that earlier engagement of particular stakeholder groups may have been beneficial in identifying sector-specific implementation issues and setting more appropriate timeframes for implementation.

Previous consultation processes

2.35 Some of the NISA measures had been canvassed in previous consultation processes led by the relevant entities. These included: the Business Tax Working Group 2012 review; Boosting the Commercial Returns from Research, October 2014; the Tax Discussion Paper, Re:think, March 2015; the Research Infrastructure Review 2015; and STEM–Vision for a Science Nation consultation in June 2015.

2.36 In addition, PM&C advised the ANAO that the three NISA education measures were developed in response to the Review of Research Policy and Funding Arrangements (November 2015), which consulted widely with the university and business sector. PM&C also advised the ANAO that the head of the Taskforce40 had indicated that she and a senior taskforce official had met with a wide range of stakeholders during the course of the Taskforce process.

2.37 Drawing on previous and relevant consultation processes is appropriate and consistent with consultation principles aimed at reducing the burden on stakeholder groups. In providing advice it is also important to transparently link the views provided by stakeholders and the proposed measures—noting that several of the proposed NISA measures were not those that had been recommended through earlier review processes.

3. Planning and governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether appropriate planning and governance arrangements were established to support the timely and effective implementation of the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA). This included an examination of the evaluation framework for the Agenda.

Conclusion

Suitable planning and governance arrangements for the Agenda were established early in the post-announcement period to support most aspects of implementation. Some elements of the evaluation framework were delayed, including confirmation that entities had identified baseline data and robust evidence collection systems. Current indications are that impact assessment will be affected by variability in the quality of entities’ performance measures and data collection systems. Assessing the impact of the package as a whole is also likely to be challenging.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that Industry finalise the NISA evaluation strategy and establish formal monitoring arrangements with relevant entities so that the results of evaluation activities can be used to inform advice to government on future measures and the continuation of existing measures.

Was implementation planned effectively?

An implementation plan was developed for the NISA in the months following the launch of the Agenda. The implementation plan addressed relevant implementation principles and was prepared in the timeframe set by government (1 March 2016), some four months before the first measures were due to be implemented.

Implementation planning

3.1 Successful implementation of government policy initiatives is one of the key responsibilities of public sector entities. Effective implementation planning helps to support the delivery of initiatives on time, within budget and to an acceptable level of quality.41

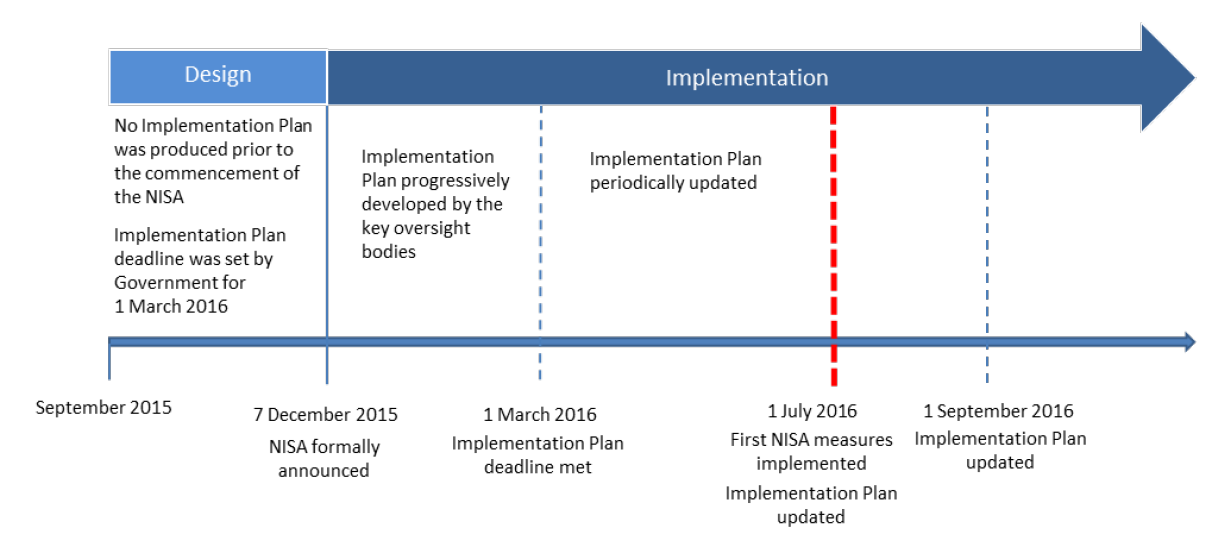

3.2 During the development of the NISA and in the final advice provided to government, officers from PM&C or the Taskforce did not prepare an implementation plan for the Agenda or provide advice on the challenges and risks of implementing a sizeable cross-portfolio package. Some implementation details were included for the individual measures that were proposed for the NISA, but this information did not provide a ‘whole-of-Agenda’ perspective on matters that would typically be included in an implementation plan: an implementation schedule; governance arrangements; monitoring, review and evaluation; and risk management.

3.3 As part of its decision on the NISA in December 2015, the Government required that an implementation plan be prepared by 1 March 2016, for approval by the Prime Minister.

3.4 The timeframe and requirements set by government were met (Figure 3.1). An implementation plan for the NISA was provided to the Prime Minister in late February 2016, via the Industry Minister.

Figure 3.1: Timeline for the development of the Implementation Plan for the NISA

Source: ANAO analysis of information provided by Industry.

3.5 The Implementation Plan was developed by the Delivery Unit in consultation with appropriate stakeholders and was underpinned by measure-specific implementation plans prepared by the lead entities. Members of the interdepartmental implementation committee (NISAIC) were provided an opportunity to comment and provide input on the draft plan.

3.6 The March 2016 Implementation Plan addressed key areas, including:

- governance arrangements—and an overview of the roles and responsibilities of the various oversight bodies and the participating entities;

- the implementation schedule for the 24 measures (which reflected the timeframes publicly announced on 7 December 2015);

- the approach to engaging stakeholders, along with detail of proposed consultation arrangements for each measure;

- the risk management framework; and

- review and evaluation arrangements—including a proposed evaluation strategy.

3.7 The Implementation Plan was reviewed as implementation of the NISA progressed. Although the Plan itself was not publicly released, the progress of initiatives has been reported on the innovation website (www.innovation.gov.au).

Were suitable governance arrangements established?

Suitable governance arrangements were established to support implementation of the Agenda. Specific oversight bodies were established promptly, and operated within a governance framework for the Government’s broader innovation agenda.

Specific oversight bodies for the NISA

3.8 Although the Taskforce’s advice to government did not address proposed governance arrangements for the NISA, specific oversight bodies began operating in December 2015 following the announcement of the Agenda, namely:

- an interdepartmental implementation committee (known as NISAIC), headed by an independent chair42 who reported directly to the Industry Minister; and

- a NISA Delivery Unit, operating out of Industry.

3.9 The establishment of both bodies was foreshadowed by the Industry Minister during the official launch of the NISA, in which he outlined the governance framework to support the innovation agenda and its importance to government.43 Industry advised the ANAO that advice had been provided to the Industry Minister at senior levels within the department on proposed arrangements, although no documentation was provided to demonstrate the nature and timing of the advice provided.

3.10 The NISAIC held its first meeting on 18 December 2015. The meetings were attended by representatives (at Deputy Secretary or equivalent level) from 11 entities, and were initially held on a monthly basis.44 The Delivery Unit also started operating in December 2015, initially through the secondment of a senior public servant (division head level) to Industry, with other staff recruited as needed.45 The respective roles of the NISAIC and Delivery Unit were formalised in the NISA Implementation Plan that was provided to the Prime Minister in late February 2016. Both bodies had complementary roles to drive implementation of the Agenda (as described in Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Roles of the specific oversight bodies for the NISA

|

Interdepartmental committee (NISAIC) |

NISA Delivery Unit |

|

|

Source: ANAO presentation of information provided by Industry.

3.11 The documentation examined by the ANAO indicated that the Delivery Unit has met its assigned roles and responsibilities. In supporting the NISAIC to drive implementation of the Agenda, the Delivery Unit’s work centred around two main tasks:

- working with the participating entities on a range of implementation matters: input to the overarching Implementation Plans; progress updates; planned review and evaluation activities and timeframe; and

- preparing reports to government, via the NISAIC.46

3.12 One of the Delivery Unit’s specific tasks was to develop and implement a risk management framework for the Agenda. A framework was developed based on Industry’s existing model and outlined in the Implementation Plan. A number of risks were identified to the successful implementation of the Plan, and one of these risks was highlighted in the Implementation Plan: ‘…NISA measures fail to be seen as part of a positive agenda to achieve economic reform’. No other risks were included in the Plan.

3.13 Most aspects of the governance arrangements for the NISA were favourably reviewed by the Delivery Unit in a ‘lesson learned’ paper provided to the NISAIC in March 2017. In particular, the interaction of the oversight bodies with policy leads across different entities was considered to have provided a ‘whole-of-government’ perspective that would not otherwise have been available.

Oversight of the broader innovation and science system

3.14 While the NISAIC and Delivery Unit are responsible for monitoring and reporting on the NISA, two advisory bodies have a wider remit over the innovation and science system:

- Innovation and Science Australia (ISA); and

- the Commonwealth Science Council.47

3.15 The establishment of ISA was one of the 24 measures in the NISA. Legislation to establish ISA was originally scheduled to be in place by 1 July 2016 but was delayed due to the caretaker period for the 2016 federal election. The legislation was passed by the Parliament on 20 October 2016. ISA and the Commonwealth Science Council were established to provide strategic advice to government, and to consider issues from a system-wide perspective. ISA is also responsible for oversight of a number of Australian Government programs, including the R&D Tax Incentive. ISA advised the ANAO that it is not responsible for evaluating individual NISA measures.

3.16 In February 2016, ISA published a Performance Review of Australia’s Innovation, Science and Research System.48 The review provided a baseline from which to develop a key deliverable, the 2030 Strategic Plan, which is expected to be provided to government in late 2017. The Performance Review concluded that: ‘The findings in the ISR System Review make one thing very clear: we need to significantly lift our game if we want to be a top tier innovation nation.’ 49 Key findings are listed in Box 2.

|

Box 2: Key findings of the Performance Review of the Australian Innovation, Science and Research System (2016) |

|

The review assessed performance against three activities—knowledge creation, knowledge transfer and knowledge application—as well as outputs and outcomes. Knowledge creation—Australia is above average, including good levels of collaboration among researchers and world-class research infrastructure assets. Knowledge transfer—needs to be improved, including limited collaboration between researchers and businesses. Knowledge application—Australia’s knowledge application does not currently match its strength in knowledge creation. Outputs—Australia has innovative small and medium-sized enterprises and some highly innovative sectors, however Australia’s innovations are not that novel. In many sectors innovations are new to the business only and reflect a low degree of novelty. Outcomes—Australia’s economic performance has been strong compared to other nations and Australia has performed well on a number of indices of social outcomes, however there has been a slowdown in productivity growth. The strengths and weaknesses of system-wide issues were also assessed. |

Source: ANAO presentation of Innovation and Science Australia’s published report, available at www.innovation.gov.au.

3.17 There was coordination between the specific oversight bodies for the NISA and with ISA (which is supported by the Office of Innovation and Science Australia). Representatives from these bodies attended some NISAIC meetings. Progress reports on the NISA were shared with the Chair and Deputy Chair of ISA, as was the evaluation strategy for the Agenda.

Was there appropriate oversight of stakeholder consultation?

Oversight arrangements for stakeholder consultation were appropriate. Under the NISA Implementation Plan, the primary responsibility for stakeholder consultation was assigned to the lead entity for each measure. The Delivery Unit explored whether joint consultation sessions would be beneficial, but no specific need for structured consultation was identified. Lead entities have reported measure-specific consultation to the Delivery Unit.

Engaging with stakeholders

3.18 In the NISA Implementation Plan, responsibility for stakeholder consultation was principally assigned to the lead entity for each measure. Details of stakeholder consultations, including planned dates, were required to be included in the Implementation Plan Overviews for each measure developed by the lead entity. In turn, key consultation milestones and events were listed against each measure in the NISA Implementation Plan.

3.19 The NISA Delivery Unit had a role to coordinate aspects of consultation. This included identifying and facilitating joint sessions for stakeholders involved in more than one measure. Though some initial efforts were made to deliver on this role, no specific opportunities were identified, and no structured consultation of this kind was undertaken. According to the Delivery Unit, this was largely due to the different implementation timeframes for the NISA measures.

Consultation on individual measures

3.20 The progress reports for the NISA indicate that consultation occurred for some individual measures, particularly those that required legislation. For instance, for the tax measures, some public and/or targeted consultation occurred, including discussion papers and draft legislation being exposed for comment. In one case (Tax incentives for angel investors), the announced implementation timeframe put pressure on the level of consultation that was undertaken.

Was an effective evaluation framework developed?

An evaluation framework was developed but not in a timely or fully effective manner. Limited advice was provided to government during the design process about the specific impacts of the Agenda, and how or when they were to be measured. While evaluation arrangements were progressively developed post-announcement, there were delays and issues associated with the identification of suitable performance measures and data sources.

Developing the framework

3.21 As indicated in Chapter 2 (paragraph 2.3), officers from PM&C or the Taskforce did not provide advice to government in the design phase to indicate how or when the impacts of the Agenda were to be reviewed and evaluated. An evaluation schedule considered by NISAIC in September 2016 indicated that much of the evaluation of outcomes will occur in the years after 2019. This timeframe is not unexpected; it reflects the time required for the measures to have an impact on business activity, as well as time lags in obtaining data on which to base an evaluation (especially for the tax measures).

3.22 Efforts to develop an evaluation framework for the NISA commenced shortly after the announcement of the Agenda. In late January 2016, the Chief Economist from Industry provided a paper to NISAIC on measuring the impact of NISA. The paper emphasised a number of key points including the need for:

- identification of meaningful and measurable outcomes, to be articulated and agreed in advance of measure launches and arrangements put in place to capture the necessary data;

- clear governance arrangements across agencies, with the establishment of a working group to represent all lead departments; and

- active collaboration between responsible parties.

3.23 Around the same time, the chair of NISAIC separately raised concerns in a letter to the Minister about the quality of the performance metrics being prepared for some measures—pointing to a widespread failure to indicate how they might be measured.

Implementation Plan

3.24 The process for developing the evaluation framework, including roles and responsibilities, were articulated in the NISA Implementation Plan (first developed in March 2016). The agreed approach was that lead entities would be responsible for their own evaluation activities, while the NISAIC would work collaboratively on NISA measures. As intended, a working group, chaired by the Chief Economist, was established to represent and assist in the evaluation of the individual measures. A stated goal of the cross-entity collaboration was to improve the collection and use of data to measure impact. To assist with this goal, a template was developed by Industry and provided to all participating entities.

3.25 The Implementation Plan set a requirement, agreed by lead entities, that each initiative would have a program logic50 in place and be ‘evaluation-ready’ prior to 1 July 2016. The Plan required lead entities to:

- clearly articulate what the measure is intended to achieve and how it will do this;

- identify appropriate performance measures;

- identify or initiate necessary data sources; and

- schedule evaluation activities into the future.

3.26 The 1 July 2016 evaluation-ready deadline was not met. It was initially extended to 1 August and then to 30 September 2016, where the NISAIC was advised that all lead entities had met the requirements and provided supporting documentation to Industry. This included a draft schedule of evaluation activities planned by the lead entities. The schedule indicates that much of the more substantial evaluation activity is planned three to five years post implementation.

3.27 The ANAO examined a sample of evaluation plans prepared by entities, and identified a number of common issues including:

- necessary data is not always available or reliable – for example, due to privacy constraints and limited access to measure specific data;

- reliance on anecdotal evidence, rather than better qualitative or quantitative evidence, for early indications of impact; and

- difficulties in attributing cause and effect—given other factors also contribute to the broader outcomes being sought, for instance job creation and economic growth.

In addition, few of the entities used the evaluation template developed by Industry to assist the lead entities to meet evaluation-ready requirements.

3.28 The adequacy of entities’ evaluation ready arrangements was subsequently followed up by Industry in early-mid 2017 through a scheduled post-commencement review, as discussed further in Chapter 4 (paragraphs 4.19 to 4.21).

Whole of Agenda outcomes framework

3.29 In September 2016, an approach to evaluating the NISA package as a whole was provided by Industry’s evaluation unit to the NISIAC. The framework shows the links from individual measures through pillar-level outcomes to whole-of-agenda outcomes. This included the development of detailed ‘outcome chains’ for each of the four pillars (see example in Figure 3.3). The outcome chains aim to show the expected links between the individual initiatives and the whole-of-package outcomes, moving through three intermediate layers:

- sub-pillar outcomes (Level 1)—changes in attitudes, knowledge, skills and aspirations;

- sub-pillar outcomes (Level 2)—changes to practices/behaviours resulting from adoption and application of knowledge, attitudes, skills and aspirations; and

- pillar outcomes—results of behaviour changes at system level.

Figure 3.3: Outcomes chain for Pillar One of the National Innovation and Science Agenda – Culture and Capital

Source: ANAO reproduction of information provided by Industry.

3.30 These complicated links are considerably more detailed than was considered during the design process for the NISA, where only broad statements were made about the intended outcomes to be achieved. For the Culture and Capital pillar, some possible metrics have been identified for each of the three intermediate layers and the whole-of-Agenda outcomes. However, these measures have not yet been formally approved by the NISAIC; nor have metrics yet been developed or agreed for the other three pillars.

3.31 Industry acknowledged to the ANAO in April 2017 that there are significant challenges in evaluating the contribution of the NISA to the broader innovation landscape and the changes sought by government. Industry has commented to the ANAO that many of the measures and effects are relatively small, and are unlikely to be captured at a whole-of-economy (macro) level. Moreover, there are many other activities that influence the broader outcomes being sought, and it will be difficult to isolate the contribution of particular measures of the Agenda as a whole.

3.32 In March 2017, the Delivery Unit identified and reported a ‘Lessons learned’ to the NISAIC, noting that, in relation to the design phase:

Implementation and evaluation readiness might have been improved if clearer descriptions of each measure’s objectives, particularly outcomes and outputs, had been developed as part of the NISA.

This would have enabled earlier development of evaluation material and in some case provided greater clarity on deliverables.

3.33 The importance of formalising evaluation strategies early has been raised in earlier ANAO reports.51

Recommendation no.2

3.34 The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science finalise the evaluation strategy for the National Innovation and Science Agenda, and establish formal monitoring arrangements with relevant entities, so that the results of evaluation activities can be used to inform advice to government on future measures and the continuation of existing measures.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science response: Agreed.

3.35 The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science agrees with the recommendation, noting that responsibility for evaluating programs rests with the agencies responsible for their implementation. The Department has already undertaken a coordination role of evaluation activities associated with the NISA. Subject to ministerial agreement, we will work with other agencies to establish formal monitoring arrangements to provide advice to the Government on the impact of NISA measures.

4. Monitoring and reporting on progress

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the implementation of the National Innovation and Science Agenda, and the outcomes to date, have been effectively monitored and reported on by the specific oversight bodies—the interdepartmental implementation committee (NISAIC) and the NISA Delivery Unit.

Conclusion

Monitoring and reporting arrangements for the Agenda have, in most respects, been effective. Regular progress reports covering all measures and all responsible entities have been provided to government and other relevant stakeholders. The advice provided drew attention to various implementation risks, including not meeting the publicly announced timeframes. However, in a number of cases, the accompanying ‘traffic light’ ratings provided a more optimistic view of progress than was supported by the evidence. This included seven measures that did not meet the publicly announced timeframe but were not rated appropriately.

Areas for improvement

Since the implementation of the NISA is substantially complete, the ANAO has not made a recommendation on the monitoring and reporting arrangements. A clear area for improvement would be to establish a better defined rating system to reduce ambiguity and provide stronger assurance to government on the state of implementation.

Were effective monitoring arrangements established?

Effective monitoring arrangements were established, which covered all relevant entities and all measures agreed by government. The arrangements centred on regular progress reports to government and other stakeholders. The reports were compiled by the Delivery Unit and underpinned by information provided by lead entities for each measure.

Implementation schedule

4.1 When the Agenda was announced planned implementation timeframes were provided on ‘fact sheets’ for individual measures. The fact sheets were initially posted on the NISA website (www.innovation.gov.au) on 7 December 2015. They were removed on 20 April 2016 and replaced by a webpage with updates for relevant measures.

4.2 For the 34 measures listed in the fact sheets52, implementation was spread over an approximately three-year period from December 2015 until the end of 2018. The bulk of measures were to be implemented, or to take effect, from 1 July 2016. The implementation schedule, as per the announced timeframes, is presented at Appendix 4. The timeframes generally fit into one of the following categories:

- defined start dates or months—for example, funding will commence on 1 July 2016 for Data61; or

- defined but broader time periods—for example, funding will commence in 2016–17 for Quantum computing; or

- expected start dates or periods, subject to the passage of legislation—for example, Tax incentives for angel investors will apply from the date of Royal Assent and is expected to commence from 1 July 2016.

4.3 From 5 February 2016, the announced implementation timeframes were included in progress reports to government.

Progress reports

4.4 Following their establishment in December 2015, the NISAIC and the Delivery Unit moved quickly to establish arrangements for monitoring and reporting on the progress of the Agenda. In the initial period, this involved developing a reporting template, based on information provided by the participating entities and vetted by the oversight bodies.

4.5 The reporting format evolved as the NISA progressed. The reports generally provided information on the key milestones achieved during the reporting period, potential issues for the implementation of specific measures and advised corresponding ministerial announcements.

4.6 The first progress report was provided to the Industry Minister on 8 January 2016. Progress reports were also provided to government and were shared with other internal stakeholders, including the Chair and Deputy Chair of Innovation and Science Australia. Progress reports were typically accompanied by a brief to the Industry Minister prepared by Industry as well as a letter to the Industry Minister prepared by the Independent Chair of NISAIC. These letters provided candid advice on a range of matters, including concerns with aspects of implementation.

4.7 Progress reports were initially provided on a fortnightly basis.53 From August 2016, progress was reported on a monthly basis, reflecting the Independent Chair’s view that good progress had been made in implementing the Agenda.

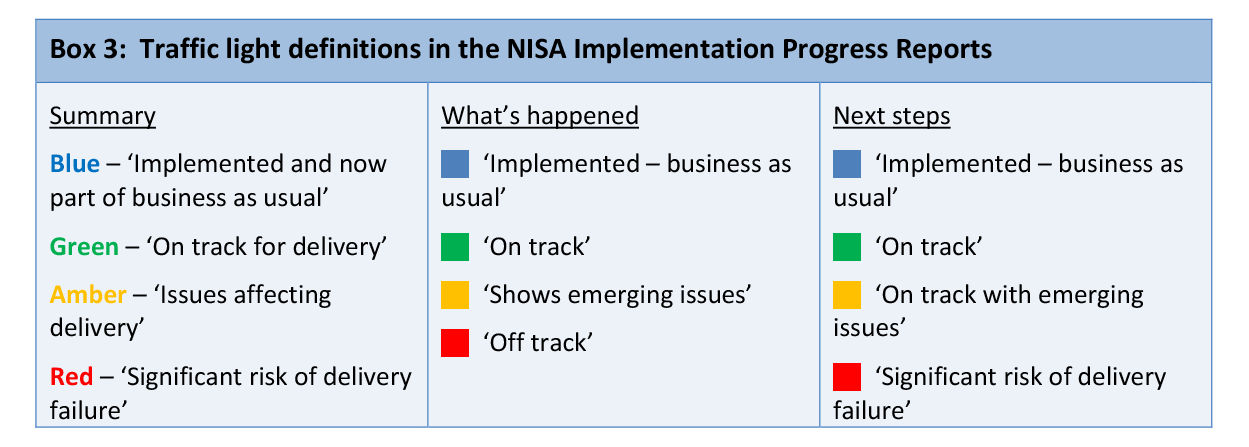

Traffic light ratings

4.8 The progress reports used ‘traffic light’ categories to indicate the implementation status of measures and to support the Delivery Unit’s comments on progress. Initially, the standard categories of Red, Amber and Green were used. In July 2016, when the first measures were due to be implemented, a fourth category of Blue was added. In the progress reports, traffic light categories were applied in three contexts:

- to indicate what had happened in the previous period (fortnight or month);

- to forecast the next steps; and

- to provide a summary of overall progress of the NISA.54

Across these three contexts, there was some variation in definition of the Amber rating (Box 3).

Source: ANAO presentation of information provided by Industry.

4.9 The definitions used to distinguish between the implementation categories were broad and were not further defined in the progress reports to aid judgement and reduce ambiguity. In particular, the progress reports did not indicate what circumstances would constitute ‘a significant risk of delivery failure’. The Blue category was further defined when it was introduced, but the expanded definition was not included in the progress reports:

A measure is rated blue when it forms part of business-as-usual administration on the basis that delivery:

- has commenced, with intended users having access;

- is underpinned by sustainable legal and administrative frameworks; and

- is subject to appropriate ongoing oversight, governance and adjustment.

Has progress reporting been timely and accurate?

Progress reporting has been timely and, in most respects, accurate. The oversight bodies provided regular and generally clear advice to government on the status of measures and the risks of not meeting milestones or announced timeframes. In some cases, the ‘traffic light’ ratings used to signal progress did not appropriately match the level of progress. This included seven measures that did not meet the announced timeframe but were rated as either ‘on track with emerging issues’ or ‘on track’.

Assessment of progress

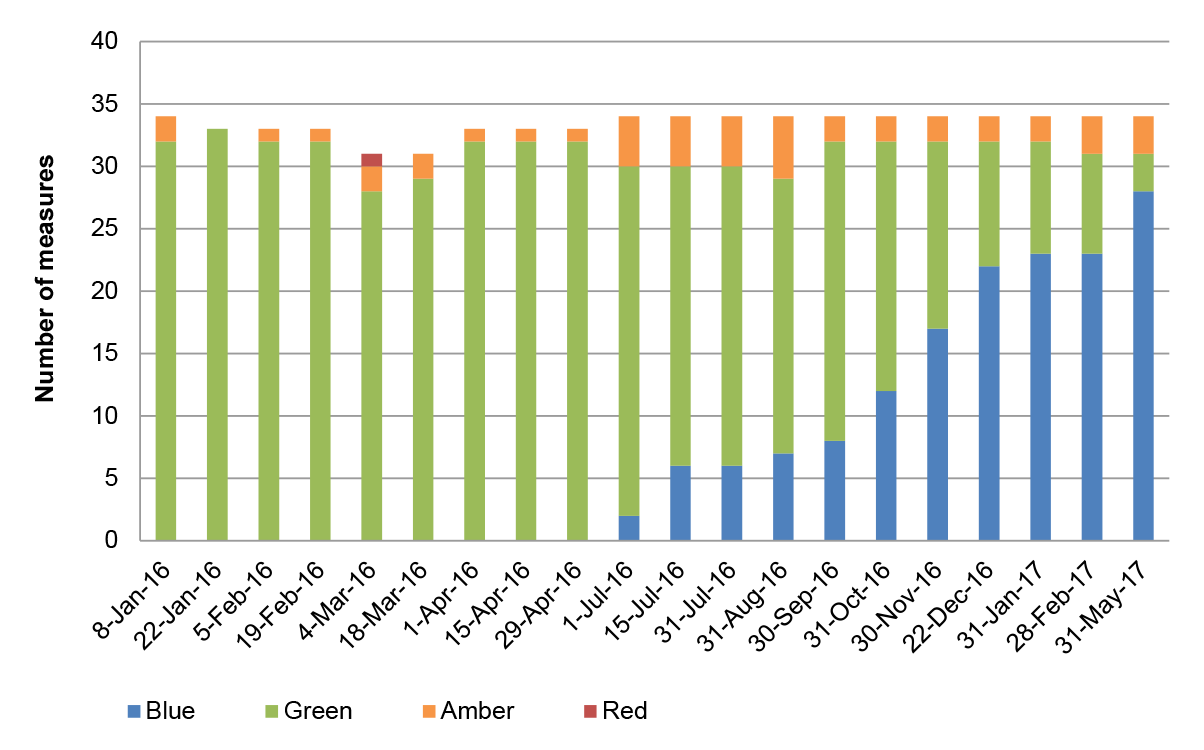

4.10 As shown in Figure 4.1, the overwhelming majority of measures were rated by the Delivery Unit as Green, signifying they were ‘on track’. Increasing Blue ratings occurred from July 2016 as measures were implemented.

Figure 4.1: Traffic light ratings in NISA Implementation Progress Reports

Note: The number of measures varies due to several factors including the addition or removal of measures as well as some measures not being rated for some reports.

Source: ANAO analysis of information provided by Industry.

4.11 Since monitoring began, some ten of the 34 measures have been rated Amber, with the majority of issues occurring in July and August 2016 following the caretaker period for the 2016 Federal election. Only one measure, Tax incentives for angel investors, was ever rated as Red, following concerns raised by the lead entity (Treasury) that limited consultation would affect the design of the measure. This measure was implemented by the announced timeframe.

Changes to the implementation schedule

4.12 The progress report considered by the NISAIC on 23 June 2017 (for the period to 31 May 2017) showed that 28 of the 34 sub-measures were implemented and part of business as usual activities. The progress report advised that delivery was ‘…overwhelmingly on track’ and ‘limited slippages do not impact on the integrity of the Agenda’.

4.13 Of the remaining six tracked items, three were categorised as ‘issues affecting delivery’ by the announced timeframe; and three were on track to meet the announced timeframe. The three measures with issues affecting delivery all involve legislation being passed in the Australian Parliament, namely:

- Access to company losses;

- Intangible asset depreciation; and

- Improve bankruptcy and insolvency laws.

Announced timeframes not met

4.14 Although the majority of NISA measures are categorised as ‘implemented’, some seven measures were not implemented by the publicly announced timeframe. The progress reports typically included a statement indicating that the timeframe was at risk or had passed. In all seven cases, measures were rated as ‘on track’ in the period leading up to the implementation deadline being exceeded. Following the deadlines being passed, four of the measures were rated ‘on track with delivery issues’. In two cases, the measures were continually rated as ‘on track’ following the timeframe being missed.

4.15 In addition, there were two broader limitations in the monitoring process:

- the progress reports did not include a category to signify that announced timeframes had not been met; and

- there is no evidence that the timeframes were reset, to guide ongoing monitoring of progress.

4.16 Four of the seven measures that did not meet their original timeframes have since been implemented. The other three measures—Access to company losses, Intangible asset depreciation, and Incubator Support Programme—are not yet implemented some twelve months later than their original implementation timeframe. In the first two cases, this was due the legislative process; and in the latter case no specific reason was provided in the progress reports. In the most recent progress report (May 2017) the first two measures (Access to company losses and Intangible asset depreciation) were rated as Amber reflecting the issues affecting delivery and Incubator Support Programme was rated as ‘on track’.

4.17 Arrangements to monitor the implementation of measures necessarily involve a degree of judgement about the stage of implementation, and the relative complexity and timing involved. To provide stronger assurance to stakeholders on progress and where progress may be at risk, there would be merit in including, and applying, more defined traffic light ratings. This would include defining what constitutes a ‘significant risk’ of delivery failure and whether this risk includes not meeting the publicly announced timeframe.

Some measures brought forward