Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Delivery of the Moorebank Intermodal Terminal

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether the contractual arrangements that have been put in place for the delivery of the Moorebank Intermodal Terminal (MIT) will provide value for money and achieve the Australian Government’s policy objectives for the project.

Summary

Background

1. The Moorebank Intermodal Terminal (MIT) is a 241 hectare intermodal freight precinct in the south-western Sydney suburb of Moorebank consisting of an import-export (IMEX) rail terminal, interstate terminal and up to 190 hectares1 of onsite warehousing. The Australian Government first announced its plan to relocate the School of Military Engineering (SME) to enable the construction of the MIT on its freehold land in September 2004. Following the Government’s consideration of various studies it had commissioned, the project’s implementation commenced in April 2012.

2. Within that timeframe, a private sector joint venture—the Sydney Intermodal Terminal Alliance (SIMTA)—was formed in 2007 to develop an IMEX-only terminal and onsite warehousing at Moorebank. SIMTA had planned to build this on its freehold land that was purchased from the Australian Government in 2003 (the original purchaser was Westpac). The original sale was on a leaseback arrangement, where Defence immediately signed a 10-year lease (with two five-year extensions at Defence’s sole discretion) for the Defence National Storage and Distribution Centre’s (DNSDC) operations to remain on the site.2 The SIMTA site is situated directly across Moorebank Avenue from the SME land.

3. The Moorebank Intermodal Company (MIC) is a Government Business Enterprise (GBE). It was established in December 2012 and assumed full responsibility from the Department of Finance for the delivery of the project. This governance framework was selected to enable the MIT to be delivered by an entity with ‘an appropriate commercial focus while maintaining effective Government oversight’. A large component of MIC’s first year was comprised of setting up its operations. This included establishing its Board; appointing a permanent Chief Executive Officer (CEO); engaging a range of key advisory firms to support a competitive procurement process to find a private sector delivery partner; and undertaking market interactions.

4. Following an expression of interest (EoI) process in early 2014, SIMTA was selected by MIC as the preferred private sector partner (from a total of five respondents) to be responsible for the delivery of the precinct. The parcels of developable land that make up the precinct are owned by the Australian Government (158 hectares) and SIMTA (83 hectares). The two entities entered into a formal direct negotiation process in May 2014 with contractual close occurring on 3 June 2015. Financial close was achieved on 24 January 2017, and the project is now in its delivery phase.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the contractual arrangements that have been put in place for the delivery of the MIT will provide value for money and achieve the Australian Government’s policy objectives for the project.

6. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Do the terms of the transaction represent value for money, including appropriate management of demand risk?

- Is non-discriminatory open access available within all aspects of the intermodal precinct?

- Does the project’s governance framework support achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives, including the planned future privatisation process?

Conclusion

7. Value for money progressively eroded during the negotiation of the contractual arrangements. The contractual arrangements support the achievement of all or part of each of the policy objectives for the project.

8. The procurement process has resulted in contractual arrangements being negotiated for the private sector to develop and operate an IMEX terminal, interstate terminal, and associated warehousing. Negotiating directly with one respondent, rather than the original plan of maintaining competition during the second stage of the procurement process, gave rise to a number of risks. Those risks were recognised and mitigation strategies identified but those strategies were not implemented. This situation makes it difficult to conclude that value for money has been achieved.

9. It is not possible to provide assurance that non-discriminatory open access is likely to be available within all aspects of the intermodal precinct given:

- the contractual framework does not apply to all elements of terminal operations, partially applies to the rail shuttle service between Port Botany and the MIT and internal transfers within the terminal precinct, and does not apply to warehouse operations;

- most of the key detailed documents that are required for implementation of effective open access arrangements have yet to be developed; and

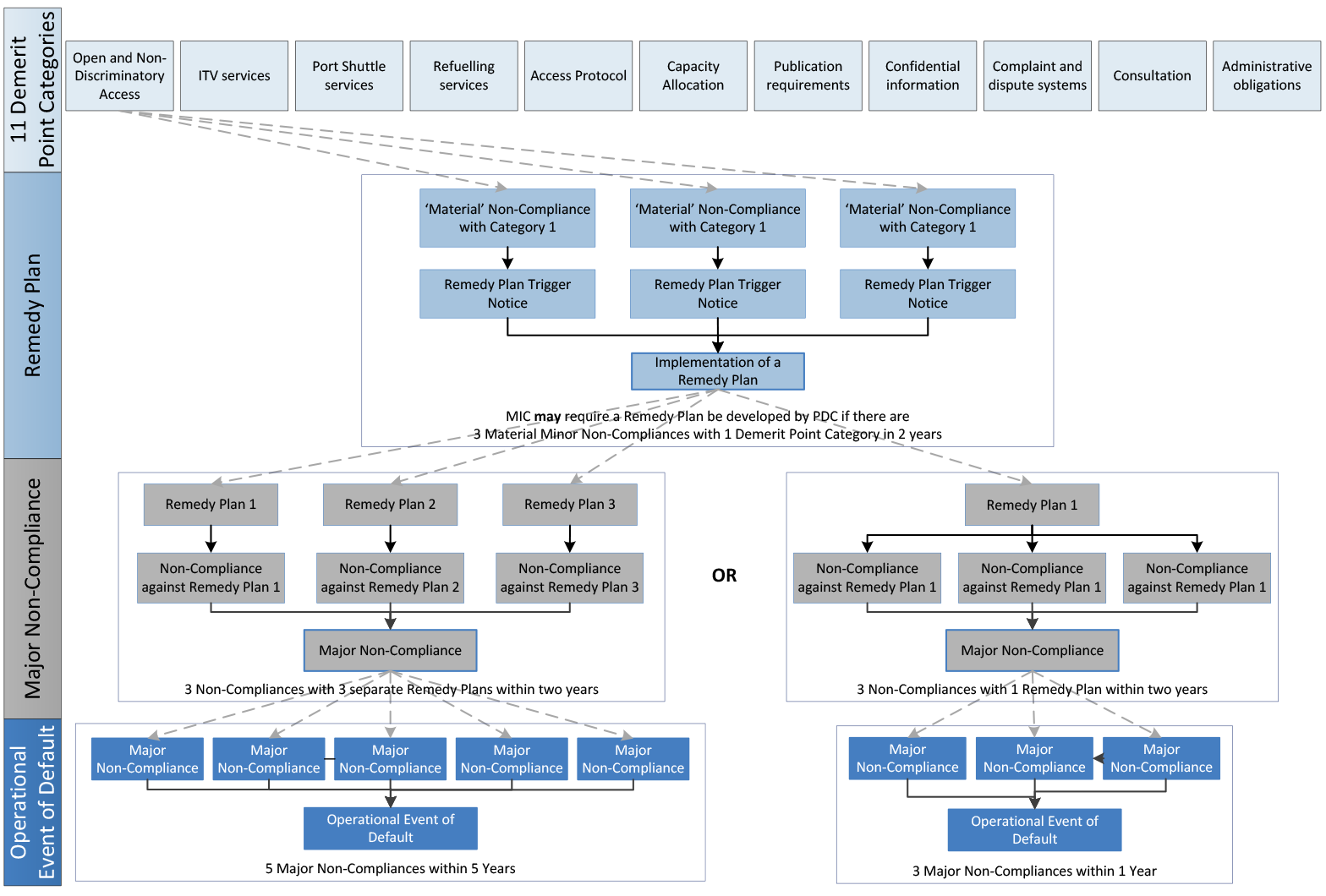

- significant non-compliance is permitted before enforcement action can be taken.

10. Clear policy objectives were established for the project. The contractual arrangements support the achievement of all or part of each of those objectives. This includes providing a level of assurance that a commercially viable intermodal precinct will be constructed and operated, and future privatisation will be able to occur.

Supporting findings

Value for money

11. The key policy rationale underpinning the development of the MIT was the significant national productivity improvements anticipated by a road to rail modal shift. Of particular importance was the placement of the terminals along the Southern Sydney Freight Line, which was considered to support existing strategies to substantially increase rail utilisation in the region.

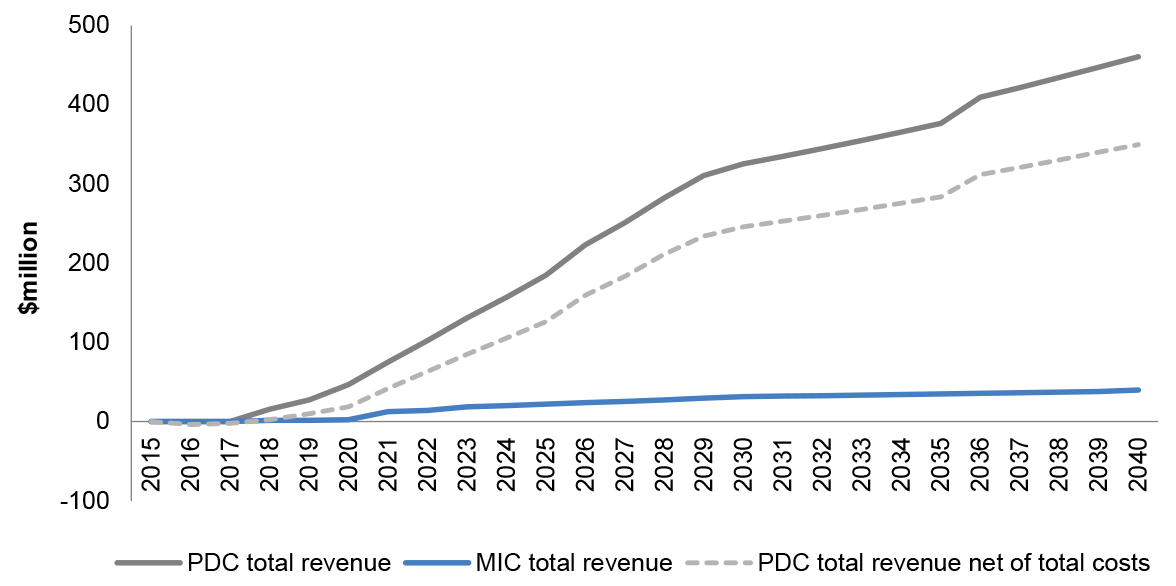

12. The procurement process was not sufficiently competitive. MIC suspended its planned procurement process at the end of the EoI stage to enter into direct negotiations with one respondent. This was on the basis that this respondent’s proposal was significantly stronger than those lodged by the other four respondents. The planned approach had been to select two or three EoI respondents from which to obtain detailed and committed proposals before proceeding to direct negotiations. Competitive pressure was also hindered by MIC not informing EoI participants of the eight criteria that it would apply in scoring responses, or that the criteria were weighted.

13. Risks to removing competition from the second stage of the procurement process were identified. Risk mitigations were also identified.

14. Negotiations took twice as long as had been planned. There was no evidence that MIC contemplated implementing the planned risk management strategy of terminating negotiations and re-engaging with other parties on ‘stand-by’ when it became evident that the negotiations were not proceeding in accordance with the planned timetable.

15. Negotiations were expected to commence after MIC had obtained a binding commitment to the key elements of the successful respondent’s EoI. No such commitment was obtained. There is no evidence that going to direct negotiations at an early stage produced a better outcome than was achievable under the original planned procurement approach of getting firm and binding offers from two or three competing parties to select from.

16. The direct negotiations secured contractual commitments to the development and operation of intermodal freight terminals and warehousing, as well as to an open access regime for the terminals. Between the commencement of direct negotiations and the final contracted outcome, MIC agreed to arrangements that have increased the Australian Government’s financial contributions and contingent liabilities (as compared with those proposed within the successful proponent’s EoI); mitigated private sector exposure to demand risk; reduced the coverage and effectiveness of the access regime; and reduced the revenue streams to the Australian Government.

17. There were shortcomings in the management of probity. For example, the probity plan did not apply to all stages of the procurement process. In addition, a probity adviser and a separate probity auditor were appointed later in the procurement process than is desirable through processes that did not involve open and effective competition for the roles. Further, MIC’s response to the probity audit of the EoI process did not adequately address each of the findings that underpinned the auditor’s recommendations.

18. Advice on the project’s progress and whether value for money was expected to be obtained was provided to Ministers at key milestones. At the conclusion of the negotiation process, MIC advised the Shareholder Ministers (the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development and the Minister for Finance) that the outcome represented ‘excellent value for money’. Ministers were separately advised by their departments that the negotiated outcome represented value for money.

Access arrangements

19. Notwithstanding that the preferred tenderer would gain exclusive access to a significant tract of Commonwealth land, MIC’s view was that an open access regime administered through contractual arrangements was the only mechanism that would attract private sector interest in the development of the project. The alternative approach preferred by the Shareholder Ministers’ departments was an access undertaking under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 which would then be administered by the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission. The 2013 approach to the market did not seek to test whether an access undertaking would deter private sector interest in the project.

20. The open access arrangements have been agreed at a framework level. Most of the key detailed documents that are required to complete and operationalise the regime have yet to be developed.

21. The open access arrangements apply to the IMEX and interstate terminals, but not the warehousing component of the Moorebank precinct. MIC’s approach to the market did not seek to include warehousing in the coverage of the open access arrangements. Only some parts of the open access regime apply to the port shuttle service between Port Botany and the terminal precinct, and internal transfers within the terminal precinct. These two partial exclusions are inconsistent with the coverage envisaged in the approach to the market, but reflect the result of the direct negotiations process.

22. A compliance regime is in place. There are shortcomings in its design that can be expected to limit its effectiveness. For example, it does not include a graduated regime of financial penalties in response to non-compliance, as was the stated preference in the request for expressions of interest. In addition, a significant number of non-compliance events can occur before there are any consequences.

23. MIC is contractually responsible for monitoring and enforcing adherence to the open access arrangements over the 99-year term of the leases. There are also other ongoing oversight responsibilities, including in relation to the capacity expansion arrangements. The resources required to undertake ongoing oversight have not yet been quantified.

Supporting the achievement of policy objectives

24. The Australian Government’s policy objectives for the MIT were clearly identified, including by MIC in its approach to the market.

25. The contractual arrangements provide for the private sector to construct and operate the intermodal freight terminals and associated warehousing at Moorebank. Specifically, SIMTA has a contractual obligation to build both an IMEX terminal and an interstate terminal, each with an initial capacity of up 250 000 Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEU) per annum. The contracts define the ultimate capacities for the IMEX and interstate terminals as 1.1 million and 500 000 TEU per annum, respectively. Expansion of the terminals to meet the ultimate capacities is set out within a heavily conditioned contractual regime, involving expansion following certain market demand signals. There is less certainty over the development timeframe for warehousing. This uncertainty is partially mitigated by warehouse ground rental payments being linked to the passage of time and MIC’s expectation that warehousing will be highly profitable for Precinct Developer Co (warehousing is not subject to the Open Access Regime).

26. The contractual arrangements enable the operation of flexible and commercially viable intermodal terminals. Until the open access arrangements are completed and shown to be operating effectively, it is not possible to provide assurance that the MIT is available on reasonably comparable terms to all rail operators and other terminal users and, as a consequence, that the desired national productivity benefits of the project will be realised.

27. The transaction was structured in a way that will enable a privatisation process through the creation of predictable income streams. Such a process is not expected to take place for some years as advice to the Department of Finance (Finance) is that sustainable positive cashflows are not expected for 15 years. There are also contractual restrictions on the entities to which the Australian Government can divest its interests.

Summary of entity responses

28. The proposed audit report was provided to MIC, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD) and Finance. Extracts from the proposed report were also provided to SIMTA, Macquarie Capital, Herbert Smith Freehills, Walter Partners and Risk Reward.

29. Formal responses to the proposed audit report were received from MIC, DIRD, Finance, SIMTA, Macquarie Capital and Herbert Smith Freehills. If entities provided a summary response, these are below, with the full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Moorebank Intermodal Company

The commercial and contractual arrangements agreed with SIMTA are complex and unique. MIC absolutely disagrees with the ANAO’s analysis that the direct negotiations did not secure a contractual commitment aligned to the Australian Government’s preferred approach. MIC has met the objectives that the Australian Government determined for MIC and has demonstrated how these objectives have been satisfied in the procurement of the intermodal facility.

Moorebank Intermodal Company’s response letter considers the government’s objectives, then comments on the audit’s high-level criteria. We have taken this approach because the ANAO appears to have not adequately understood this complex and unusual transaction and as a result has drawn several incorrect and misleading conclusions.

MIC is satisfied the arrangements represent very good value for money for the Commonwealth, provide a robust and commercially sensible open access regime, and leave the Commonwealth with a structure purpose built for divestment while maintaining full flexibility on what is sold and when.

ANAO comments on MIC’s summary response

30. The conclusion against the audit objective is outlined between paragraphs 7 and 10. In reaching a conclusion that value for money progressively eroded during the negotiation of the contractual arrangements, the ANAO analysed the outcome of the negotiations against both:

- the Australian Government’s preferred approach, as articulated in the Request for EoIs issued by MIC (noting that MIC suspended its planned procurement process at the end of the EoI stage to enter into direct negotiations with SIMTA on the basis that SIMTA’s proposal was significantly stronger than those lodged by the other four respondents); and

- key elements of SIMTA’s EoI response (given MIC’s analysis had been that the ‘commitments’ given by SIMTA justified not continuing with the planned competitive approach, and that a key risk management strategy for negotiations was to have been to bind SIMTA to those commitments prior to commencing negotiations).

Department of Finance

Finance notes the findings and key learnings of this audit report regarding the Delivery of the Moorebank lntermodal Terminal.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by other Commonwealth entities when engaging with the private sector to deliver major infrastructure projects.

Governance and risk management

Procurement

Records management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Moorebank Intermodal Terminal (MIT) is currently under construction in the south-western Sydney suburb of Moorebank. The intermodal freight precinct includes an import-export (IMEX) rail terminal, interstate terminal and a significant warehousing footprint.

1.2 The Moorebank site is in close proximity to major road and rail infrastructure (the Southern Sydney Freight Line and the M5 and M7 Motorways). The MIT will manage freight containers carried by rail to and from Port Botany as well as freight containers carried on the interstate rail network. It is intended to increase the proportion of containerised freight carried by rail, in comparison to containers carried by truck.

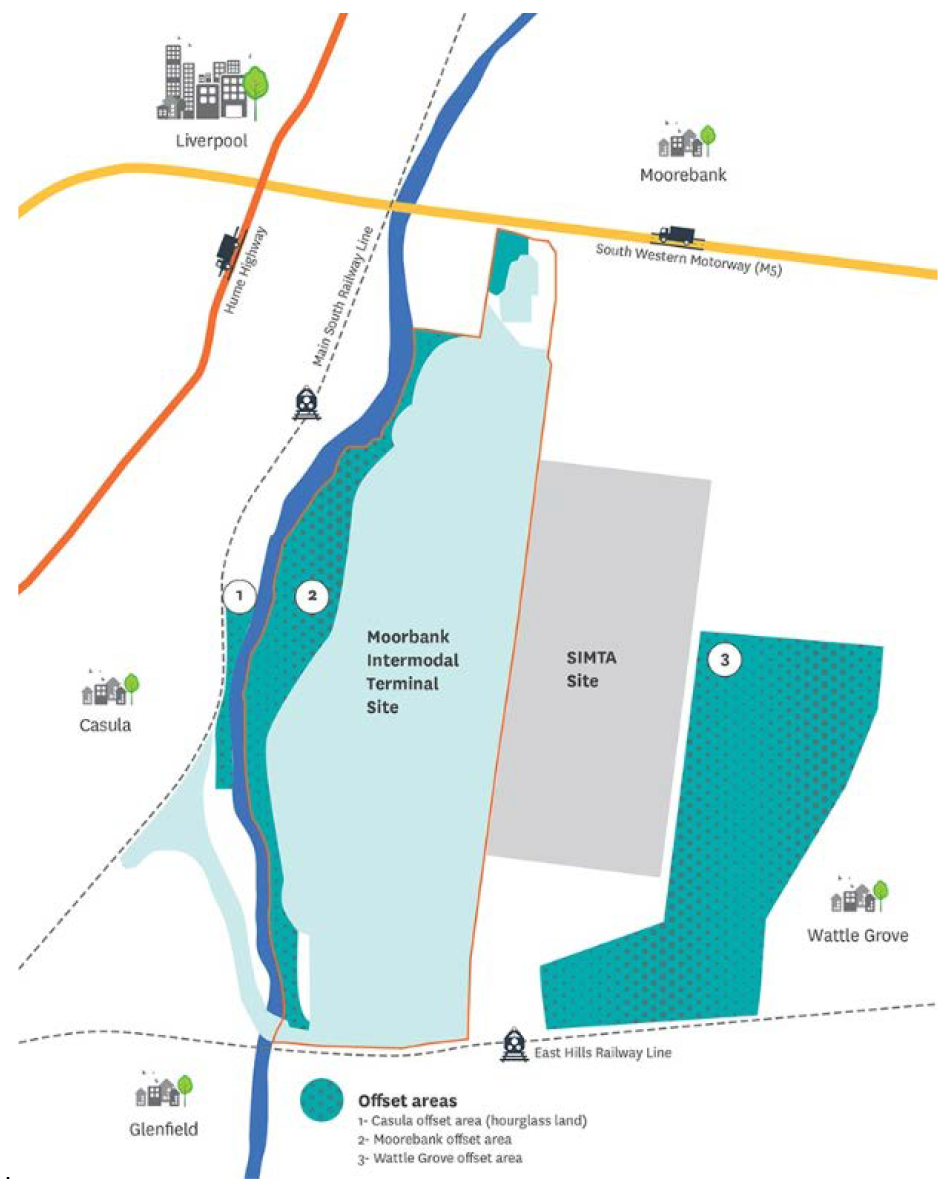

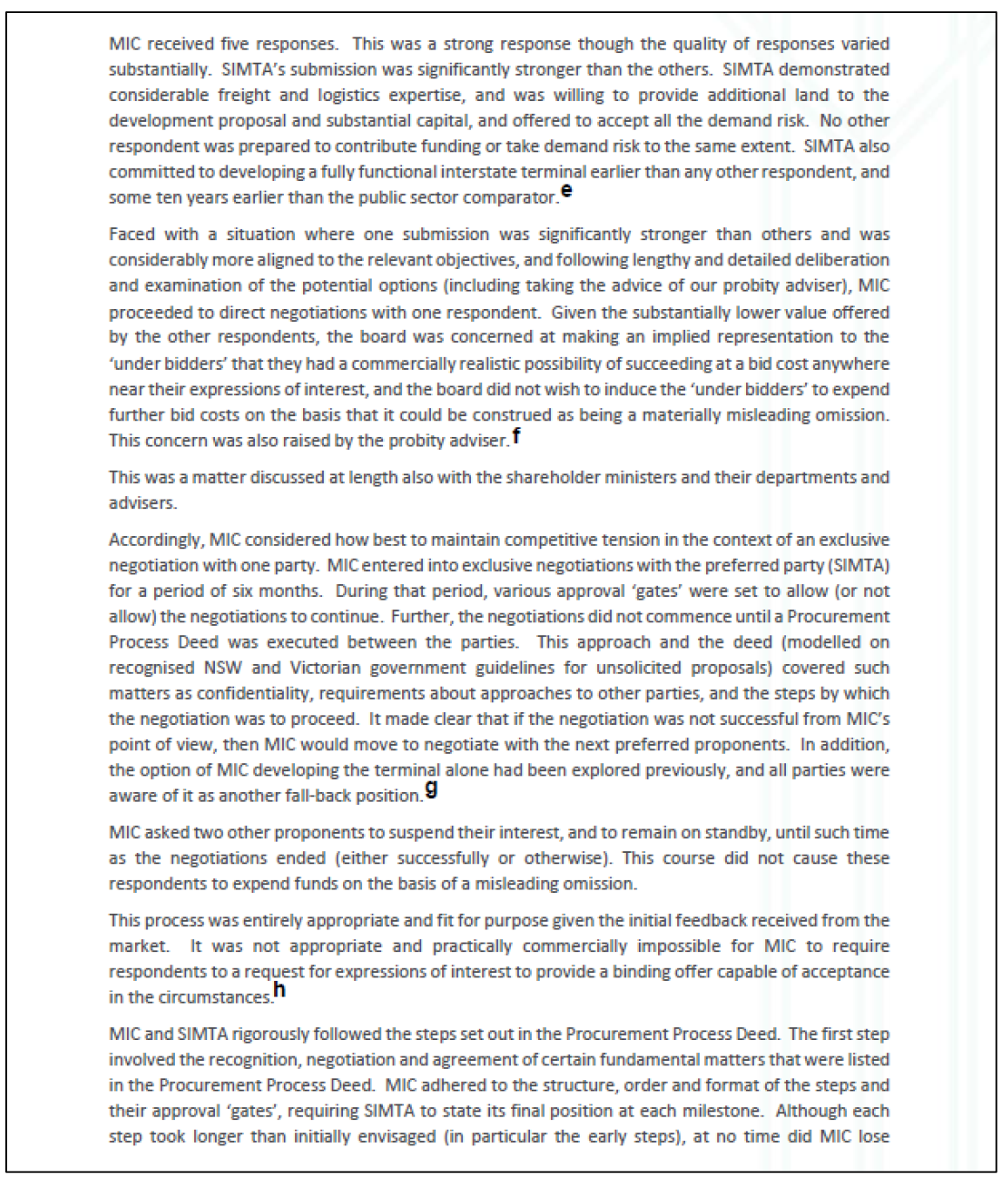

1.3 The parcels of land that make up the precinct are owned by the Australian Government and the Sydney Intermodal Terminal Alliance (SIMTA). Of the 383 hectares allocated to the precinct, 241 hectares is developable land. The parties own 65.63 (158 hectares) and 34.37 (83 hectares) per cent of the precinct’s developable land, respectively. The remaining land is associated with the biodiversity offsets required to meet the New South Wales and Australian Governments’ environmental requirements, and was also contributed by the Australian Government.3 The land ownership is reflected in the map at Figure 1.1.

Project history

1.4 The project and its location were first announced in 2004 by the Australian Government. In 2010, a detailed business case was commissioned to examine the project’s economic merits.4 The results and recommendations from this business case were presented to the Australian Government in April 2012. This formed the basis of a decision to provide $887 million5 for the delivery of the project via a new Government Business Enterprise (GBE)—the Moorebank Intermodal Company Limited (MIC).

1.5 The land on which the MIT was proposed to be built is owned by the Australian Government, but was occupied by a number of the Department of Defence (Defence) units, including the School of Military Engineering (SME). In order to develop the MIT, these Defence units were required to relocate. The activities undertaken on the land by Defence for in excess of 40 years meant that substantial remediation work was required to be undertaken before the land could be developed.

Figure 1.1: Moorebank Intermodal Precinct land parcels

Source: MIC records.

Moorebank Intermodal Company

1.6 MIC was established in December 2012 to ‘optimise private sector development of an open-access terminal’. A large component of MIC’s first year was comprised of setting up its operations and considering the means of procuring, delivering and operating the terminal. This included establishing its Board; appointing a permanent Chief Executive Officer (CEO); and engaging a range of key advisory firms to support and commence the procurement process to find a private sector delivery partner.

1.7 MIC’s sole shareholder is the Australian Government, which is represented by two Shareholder Ministers: the Minister for Infrastructure and Transport6 and the Minister for Finance. The Shareholder Ministers’ departments7 are responsible for supporting their Ministers in this role.

1.8 To facilitate the delivery of the MIT, the Australian Government provided a 99-year lease over the parcels of ex-Defence land to the Moorebank Intermodal Development Investment Trust (MIDIT), a subsidiary of MIC.

1.9 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), which are issued by the Finance Minister, apply to all non-corporate Commonwealth entities. The CPRs can be applied to corporate Commonwealth entities but have not been applied to MIC.8 Rather, as is the case with most corporate Commonwealth entities, MIC develops and implements its own procurement policies and procedures. These policies and procedures are required to meet general obligations on the organisation that it promote proper use of resources and employ effective internal controls. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit has recently commented that ‘corporate Commonwealth entities not subject to the CPRs should more closely model their procurement arrangements on the CPRs as a matter of best practice’.9

Sydney Intermodal Terminal Alliance

1.10 SIMTA was formed in 2007 to develop an IMEX-only terminal and onsite warehousing at Moorebank. SIMTA had planned to build this on its freehold land that was purchased from the Australian Government in 2003 (the original purchaser was Westpac). The original sale was on a leaseback arrangement, where Defence immediately signed a 10-year lease (with two five-year extensions at Defence’s sole discretion) for the Defence National Storage and Distribution Centre’s (DNSDC) operations to remain on the site. The SIMTA site is situated directly across Moorebank Avenue from MIC’s land.

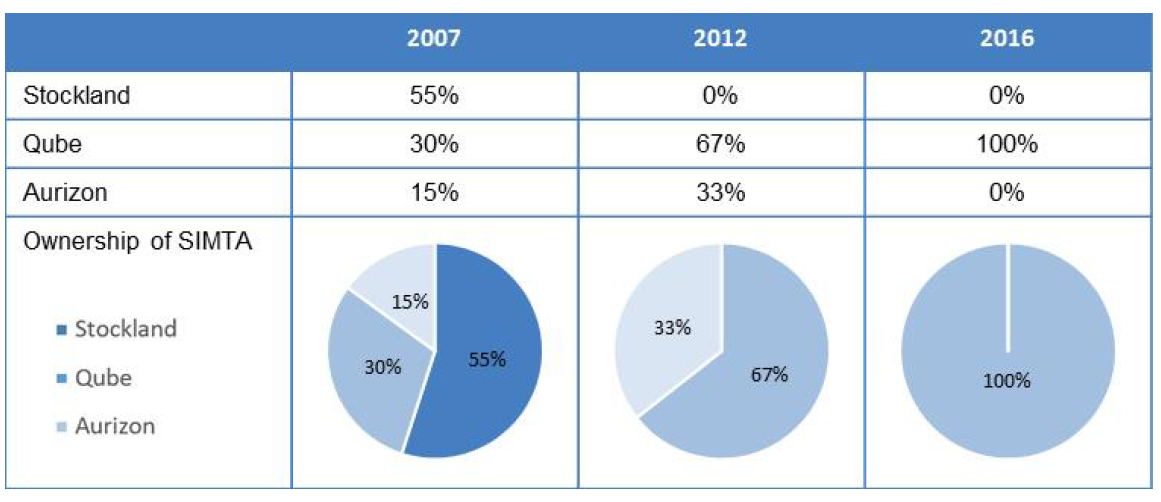

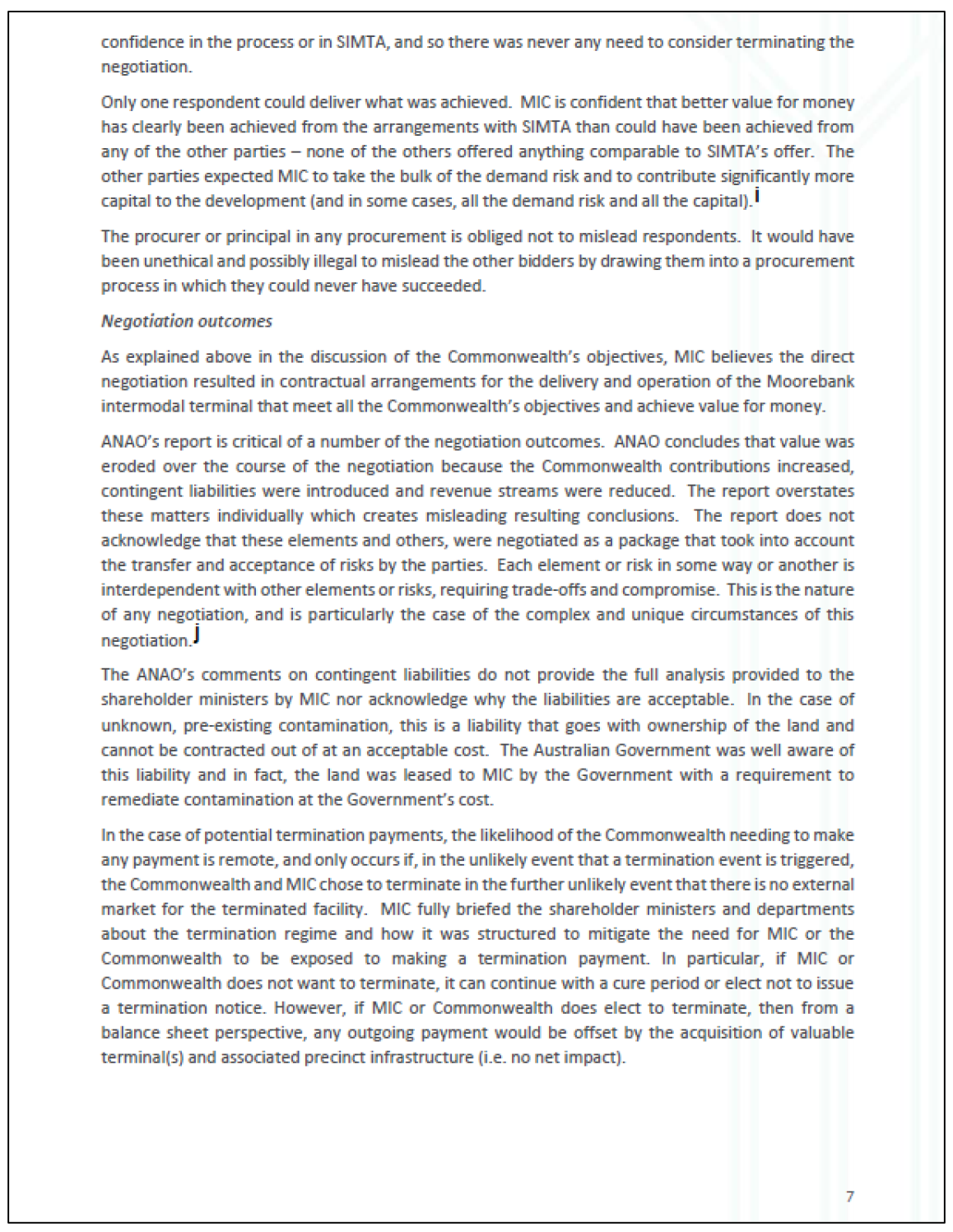

1.11 Initially formed as a joint venture, SIMTA’s owners were publicly listed companies: Stockland, Qube and QR National (rebranded as Aurizon in 2012). Since then, the ownership of SIMTA has changed twice, as shown by Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Changes in SIMTA ownership between 2007 and 2016

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.12 Between 2010 and 2012, SIMTA asserted on a number of occasions that the Australian Government was acting in direct competition with SIMTA. This was on the basis that SIMTA’s request to build rail access to its site over adjacent Australian Government land (to the south of the SIMTA site) was denied. SIMTA claimed that its proposal was fully self-funded and would be in operation up to three years ahead of the project being developed by the Australian Government.

1.13 Following MIC’s establishment and a change of Australian Government in September 2013, SIMTA commenced lobbying activities in order to achieve its desired outcome. It purported that a ‘combined’ whole of precinct approach would lead to a more efficient and valuable intermodal facility. This combined approach involved the use of both MIC and SIMTA’s sites and was said to deliver substantial budget benefits to the Australian Government. SIMTA made direct contact between late September and early October 2013 with at least three new Ministers’ offices to discuss the abandonment of MIC’s upcoming tender process. In this respect, MIC advised the ANAO in September 2017 that it:

had discussions with SIMTA in September 2013 during the market soundings and subsequently. SIMTA indicated that it wanted to develop an IMEX terminal on the SIMTA land and MIC could develop an interstate terminal on the Commonwealth land.

MIC had made it clear to SIMTA that the only way SIMTA could proceed with any development would be to participate in MIC’s procurement process, or wait until MIC’s procurement process was completed.

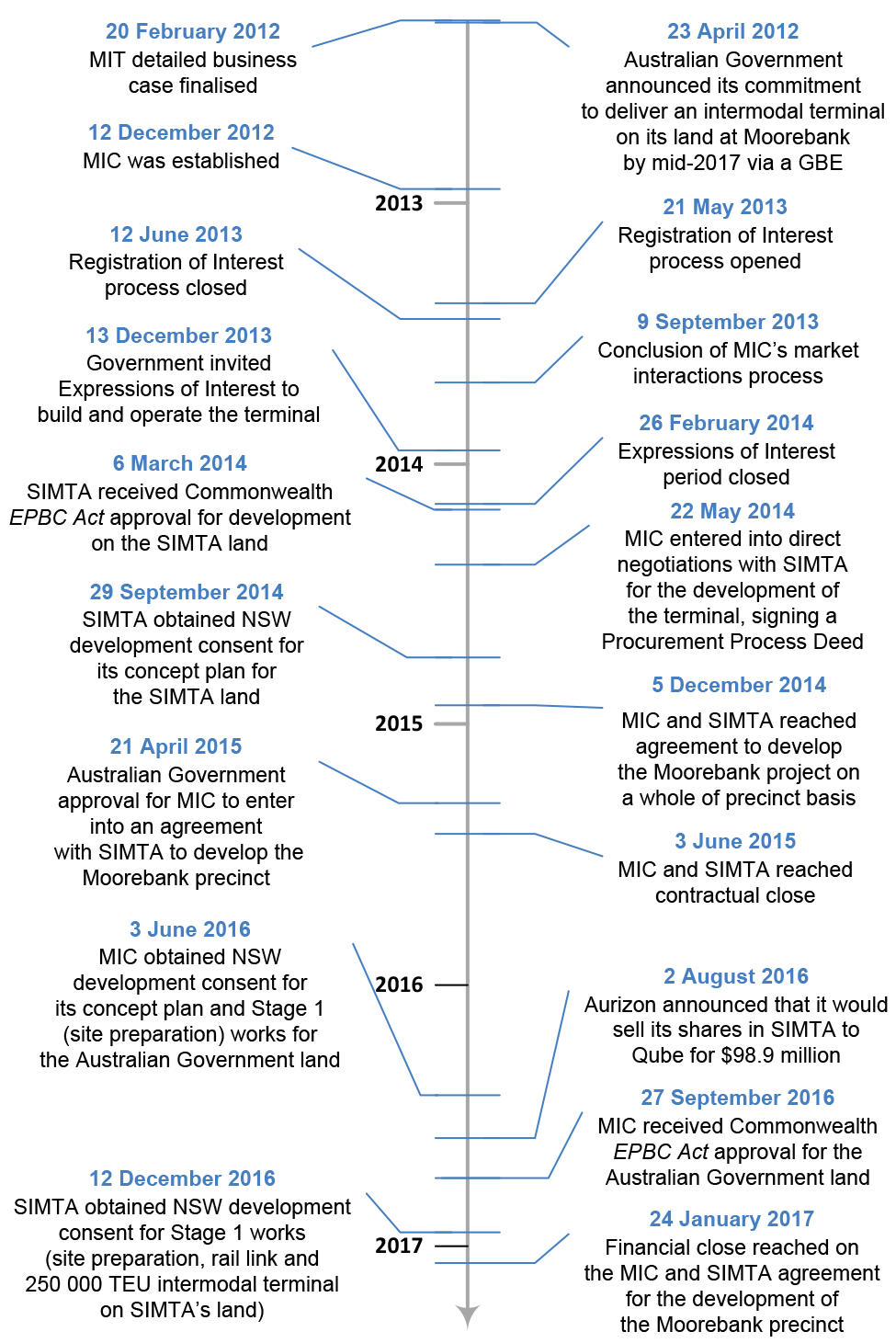

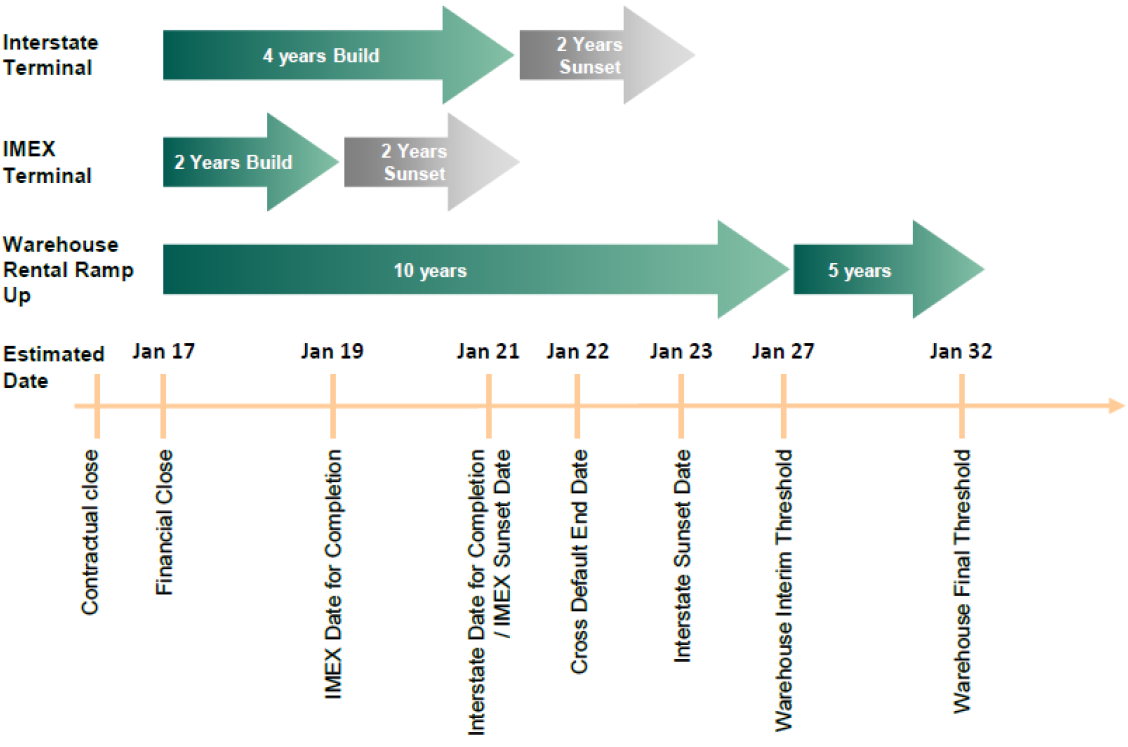

1.14 MIC’s tender process proceeded, with a request for expressions of interest (EoI) issued in December 2013 to select a private sector partner to build and operate a terminal precinct that would deliver on the Australian Government’s project objectives (see paragraph 4.1). SIMTA was the successful party, with contracts exchanged in June 2015. Financial close was reached in January 2017. Figure 1.3 provides an overview of key milestones to date for the project.

Figure 1.3: Timeline of the Moorebank Intermodal Terminal milestones

Source: ANAO analysis.

Audit approach

1.15 The objective of the audit was to assess whether the contractual arrangements that have been put in place for the delivery of the MIT will provide value for money and achieve the Australian Government’s policy objectives for the project.

1.16 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Do the terms of the transaction represent value for money, including appropriate management of demand risk?

- Is non-discriminatory open access available within all aspects of the intermodal precinct?

- Does the project’s governance framework support achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives, including the planned future privatisation process?

1.17 The audit focussed on the arrangements that were negotiated between MIC and SIMTA.

1.18 To inform the examination of the arrangements, the audit scope also included the Shareholder Minister’s departments (DIRD and Finance).

1.19 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $471,589.

1.20 The team members for this audit were Amy Willmott, Cherie Simpson, Joe Keshina Danielle Page, Emily Drown and Brian Boyd.

MIC use of non-government email services for official Australian Government business

1.21 Email communications are a widely used and accepted form of communication by and within the Australian Government. As such, they provide evidence of the conduct of government business and are important information assets. Guidance from the Australian Signals Directorate is that using non-agency-sanctioned webmail to conduct government business heightens the risk of the unauthorised disclosure of government information.10

1.22 In the course of this audit, the ANAO identified various instances of non-MIC corporate email services being used (including free web-based personal email accounts) for work purposes. This included instances where confidential documentation relating to the project was being transmitted (such as evaluation results, contracts, project valuation information, negotiation records including notes of meetings with SIMTA marked ‘confidential’ and a Shareholder Ministers’ letter). The security risks that come with using web-based email services are well known and have been publicised. These practices also represent a limitation on the scope of this ANAO performance audit as the ANAO is unable to be satisfied that all relevant email communications are captured in MIC records.11

1.23 Further detail on this matter can be found in Appendix 2.

2. Value for money

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the transaction represents value for money, including appropriate management of demand risk.

Conclusion

The procurement process has resulted in contractual arrangements being negotiated for the private sector to develop and operate an IMEX terminal, interstate terminal, and associated warehousing. Negotiating directly with one respondent, rather than the original plan of maintaining competition during the second stage of the procurement process, gave rise to a number of risks. Those risks were recognised and mitigation strategies identified but those strategies were not implemented. This situation makes it difficult to conclude that value for money has been achieved.

What was the policy rationale for the Australian Government’s development of the Moorebank Intermodal Terminal?

The key policy rationale underpinning the development of the Moorebank Intermodal Terminal (MIT) was the significant national productivity improvements anticipated by a road to rail modal shift. Of particular importance was the placement of the terminals along the Southern Sydney Freight Line, which was considered to support existing strategies to substantially increase rail utilisation in the region.

2.1 In 2012, the MIT was identified by Infrastructure Australia as one of the most important infrastructure projects in the country. This was primarily because the MIT was seen as the best way to substantially increase the proportion of Sydney’s container freight moved by rail—an important part of both Infrastructure Australia’s National Land Freight Strategy and the Australian Rail Track Corporation’s (ARTC) North-South strategy.

2.2 Supported by a detailed business case, an approach that involved a co-located import-export (IMEX) terminal, interstate terminal and onsite warehousing was considered the most efficient and commercially viable option for the delivery of the project.12 Specifically, the business case indicated that the:

- MIT was expected to generate approximately $10 billion in economic benefits through improved productivity, reduced business costs, reduced road congestion (by reducing the number of truck trips in Sydney by 3 300 per day) and provide positive environmental outcomes;

- Australian Government’s involvement in the project was considered necessary to ensure the delivery of additional interstate freight capacity that will enable efficient freight movement between port, rail and road—and in the future—across a network of intermodal terminals; and

- School of Military Engineering (SME) site was considered optimal for the development of an intermodal terminal with an interstate freight component, due to its unique proximity to key rail infrastructure and its capacity to accommodate interstate trains of 1 800 metres.

2.3 Due to the significant national productivity benefits expected to be realised, as well as the strategic size and the location of the MIT, a consistent (and current) Australian Government objective for the project has been to ensure that the terminal will be operated on an open access and non-discriminatory basis (that is, available for use by other operators on a reasonably equal basis).

Was a competitive procurement process adopted?

The procurement process was not sufficiently competitive. MIC suspended its planned procurement process at the end of the expression of interest (EoI) stage to enter into direct negotiations with one respondent. This was on the basis that this respondent’s proposal was significantly stronger than those lodged by the other four respondents. The planned approach had been to select two or three EoI respondents from which to obtain detailed and committed proposals before proceeding to direct negotiations. Competitive pressure was also hindered by MIC not informing EoI participants of the eight criteria that it would apply in scoring responses, or that the criteria were weighted.

2.4 Some 40 companies were consulted during the preparation of the detailed business case. It was concluded that their interest in participation in the project was ‘very strong’. The project’s business case considered that, to deliver value for money, it would be important to attract market interest through a competitive procurement process.

2.5 Consistent with the project’s business case, a competitive procurement process was designed by MIC.

Registration of interest

2.6 An open registration of interest (RoI) process was conducted between May 2013 and June 2013 to:

- encourage the development of a competitive field of tenderers with the required experience, capability and capacity; and

- establish a process for further interaction with select respondents, including market testing key commercial and design principles, processes and timing regarding project development and operations.

2.7 The RoI documentation noted that parties choosing not to participate in the RoI process (which included SIMTA) could participate in MIC’s later formal procurement processes commencing with expressions of interest.

2.8 In responding to the RoI process, parties were asked to provide information on their interest in and expectations of the project, comment on the concept design and identify factors likely to affect the successful delivery of the project. Nineteen parties responded, of which 16 were from the targeted group (of domestic and international organisations that operate within the freight and logistics industry; are involved in the development/management of warehousing and distribution centres; or own similar or related infrastructure).

2.9 MIC concluded from the RoI process that the number of serious bidders was likely to be limited to between two and four parties, and that the procurement process needed to recognise this and be effective at maintaining competitive tension.

Market sounding

2.10 Following the RoI process, in September 2013 MIC undertook some more targeted market sounding activities with selected parties. MIC’s Board was advised that this was to ‘seek input from selected market participants to inform the selection of a commercial structure and procurement process to meet the project objectives and maximise the commercial success of the project.’ The RoI documentation noted that MIC could, at its sole discretion, hold direct discussions with any party regardless of whether they had responded to the RoI.

2.11 MIC prepared a ‘Market Interaction Brief’ to provide to the selected parties. The brief outlined, amongst other things, a project description; proposed commercial principles; short listed IMEX terminal procurement models; and warehouse development options.

2.12 MIC wrote to three potential developers on 26 August 2013, inviting them to: review the brief after signing a confidentiality agreement; provide written responses to a set of 12 questions; and participate in a formal market sounding discussion with MIC and its commercial adviser. The brief was provided to each of the three developers (which included SIMTA). MIC and its commercial adviser also held an informal discussion with a container logistics company operating out of Port Botany on 2 September 2013.

2.13 In September 2017, MIC advised the ANAO that there were a further three parties that participated in market interactions with MIC regarding the project in August and September 2013. MIC further advised the ANAO that it provided the Market Interaction Brief ‘to all parties on 26 August 2013 with the same content’. The evidence did not support that all parties MIC engaged with as part of the market sounding received the same information. In particular:

- MIC’s records do not include any evidence of the brief being provided;

- there were no confidentiality agreements signed by four of the parties (the brief is identified as ‘MIC Confidential Information’ in the three agreements that were signed); and

- papers for one MIC Board meeting state that the container logistics company had not received the brief.

2.14 MIC’s approach in inviting a subset of potential developers to participate in the market sounding process gave rise to a risk of providing an unfair advantage to those parties that were invited to participate. This issue was raised with MIC by its probity adviser (Walter Partners) before it invited participants. MIC records did not include a response to the probity adviser or otherwise indicate that any action was taken by MIC in response to the concern that had been raised.

Expression of interest

2.15 MIC designed a competitive two-stage expression of interest (EoI) process. Responses to the first stage were to be used to shortlist at least two (but no more than three) respondents to proceed to the second (‘Project Development Request’ or PDR) stage. The second stage was to involve MIC working with shortlisted respondents to develop detailed and committed proposals from which a successful partner would be selected.

2.16 A public call for expressions of interest was made on 13 December 2013. The EoI document sought operators to lead the MIT development by establishing consortia with builders and financiers and submitting proposals to build and operate the terminal. The closing date for EoIs was 26 February 2014.

2.17 The first EoI stage was in two parts. The first part involved the public release of Part 1 of the Request for EoI document. The second part involved MIC admitting parties it assessed as qualified13 to a confidential data room with the information in the data room then to be used by admitted parties to develop their EoIs.

2.18 Admitted parties were also provided with the second part of the EoI document. This provided potential respondents with confidential information on various technical and business related aspects of the MIT including the:

- proposed allocation of risks;

- proposed approach to open access; and

- financial and other support MIC envisaged providing to the project.

2.19 A healthy level of market interest was generated by the EoI process. MIC admitted eleven parties to the data room. Five parties proceeded to submit EoIs.

Evaluation approach

2.20 The Request for EoI documentation outlined that MIC’s assessment process would involve:

- considering proposals as a group to first determine the optimal commercial structure for the project; followed by

- assessment of individual EoI responses and shortlisting of respondents based on MIC’s view of each respondent’s ability to satisfy the published project objectives, in the context of the selected commercial structure.

2.21 MIC’s approach allowed for it to select the best elements of the proposals put forward by EoI respondents for a commercial structure. But the approach also meant that MIC’s shortlisting of respondents would occur in the context of respondents not having had the opportunity to submit proposals directly responding to the commercial structure adopted by MIC. In this respect, a further stage of submissions addressing the optimal commercial structure was integral to maintaining competitive tension and achieving value for money. This was to occur as part of the planned second (Project Development Request) stage of the EoI process.

2.22 Consistent with good procurement practice, MIC prepared an EoI evaluation plan. Among other matters, the plan identified the assessment criteria that would be applied, the criteria weightings and the assessment scoring system to be employed. This plan was focused on the EoI process, with an additional evaluation plan to be prepared for the PDR phase prior to commencement of that phase of the procurement process.

2.23 The EoI Evaluation Panel was chaired by MIC’s Procurement Director with three other members (the MIC CEO, the MIC General Counsel/Company Secretary and MIC’s contracted Commercial Adviser from Macquarie Capital). The Panel was to assess EoI responses against each of the evaluation steps and report to an Implementation Committee (which was a committee of the MIC Board). The Implementation Committee’s recommendations would be considered by the full MIC Board.

Evaluation criteria and weightings

2.24 Part 1 of the EoI document outlined that MIC expected that the development of the MIT would be phased. It also set out five objectives for procuring the initial phase of the MIT. Those objectives were drawn from the Australian Government’s policy objectives for the project (outlined at paragraph 4.1).

2.25 Part 2 of the EoI document (provided to the parties admitted to the data room) included a section titled ‘Your response—what you need to tell us’. This identified 21 types of information that needed to be provided.

2.26 There were eight criteria used to evaluate the EoIs that were received. One of the criteria was described in MIC’s evaluation plan as being a ‘gateway objective’ and had a weighting of 25 per cent. To proceed to be evaluated against the other seven criteria a proposal was required to achieve a score of at least four out of ten against that criterion. The criterion was expressed as follows:

Provide certainty that those allocated with responsibility for development and operation of the IMEX Terminal and Interstate Terminal have the appropriate capacity, skills and industry knowledge to do so.

2.27 The other seven criteria were weighted at 7.5 per cent (one criterion), 10 per cent (four criteria), 12.5 per cent (one criterion) or 15 per cent (one criterion).

2.28 A shortcoming in MIC’s procurement process14 was that the EoI documentation provided to potential respondents did not identify the assessment criteria that MIC would apply in scoring the responses.15 The EoI documentation also did not identify that the criteria were weighted, or otherwise inform potential respondents as to those considerations that were of greatest importance to MIC.

Engagement with respondents and selecting the optimal commercial structure

2.29 As part of its assessment process, MIC engaged with each of the EoI respondents in respect to their proposals (see Table 2.1).

2.30 As noted at paragraph 2.20, the first assessment stage was to involve MIC considering proposals as a group to first determine the optimal commercial structure for the project. The optimal commercial structure for the project was identified by MIC taking into account a range of considerations. These included responses to the EoI and guidance from the Shareholder Ministers’ departments.

Table 2.1: Expressions of interest engagement with respondents and scoring of responses

|

|

SIMTA |

Respondent B |

Respondent C |

Respondent D |

Respondent E |

|

Total weighted scoreᵃ out of 10 |

7.7 |

4.9 |

4.5 |

3.9 |

N/A |

|

Number of tailored written questions asked by MIC |

25 |

23 |

14 |

16 |

8 |

|

Number of one-on-one interactions with MICᵇ |

5 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

Note a: Scores of four or higher were considered to have satisfactorily met the criteria. As Respondent E scored less than four on the ‘gateway’ criterion, it was not assessed against the remaining criteria and, as a result, there was no overall weighted score.

Note b: These interactions involved one interview for each respondent, with the remaining interactions via email.

Source: ANAO analysis of MIC records.

2.31 The commercial structure selected by MIC as optimal most closely resembled the EoI submitted by SIMTA. Therefore the SIMTA proposal scored significantly higher than the other proposals (see Table 2.1 above).

Assessment outcome

2.32 By April 2014, MIC had completed its assessment of the five EoIs received. After the results were presented to the MIC Board, MIC wrote to its Shareholder Ministers (the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development and the Minister for Finance) advising that it planned to change its approach to the next phase of its procurement process. In this latter respect, MIC’s advice to Ministers was that it:

[…] received five responses from potential operators. This was a strong response though the quality of responses varied substantially. One respondent’s submission was significantly stronger than the others, being willing to provide substantial capital and accept more risk.

Following lengthy and detailed deliberation (including taking the advice of our probity auditor), the board agreed to proceed to direct negotiations with one respondent.

2.33 The ANAO’s analysis is that MIC had not fully tested the extent to which respondents were ‘willing to provide substantial capital and accept more risk’, as the EoI process had only sought responses at a ‘conceptual level’. The EoI documentation had indicated that shortlisted respondents would be afforded a further opportunity through a subsequent Proposal Development Request (PDR) stage involving the development of fully detailed and committed proposals. The PDR process was to have outlined and sought direct responses to the key elements of the optimal commercial structure identified by MIC through the EOI process. In this respect, abandoning the PDR stage was inconsistent with maintaining competitive tension.

2.34 In late April 2014, the MIC Chair and CEO met with the Finance Minister and senior Finance officials to discuss MIC’s proposed approach. In May 2014, following receipt of additional details from MIC substantiating the proposed direct negotiations approach16, DIRD and Finance recommended that their Ministers provide MIC with the requested consent. This was based on advice from MIC that:

- the parties would enter into a Procurement Process Deed, which would set out:

- a negotiation timetable, including ‘approval hurdles’ that needed to be met at each stage;

- MIC’s plans to cease negotiations with SIMTA should it not be able to come to agreement on the commercial arrangements by 20 November 2014 (the deed’s termination date); and

- the ‘clear commitments’17 proposed by SIMTA in its EoI submission;

- it could sustain competitive tension by SIMTA knowing that MIC could terminate the negotiations if hurdles were not met;

- it was open to MIC to re-engage with two other qualified respondents, who would be kept on stand-by during the exclusive negotiation period; and

- based on probity advice, there was no legal or probity impediment to proceeding to direct negotiations.

2.35 MIC and SIMTA signed the Procurement Process Deed on 22 May 2014, entering them into a six month period of direct negotiations. During the direct negotiation period, the parties were to have progressed through five ‘stages’ of negotiations, with the final stage being contractual close.

Were risks from adopting a direct negotiation process identified?

Risks to removing competition from the second stage of the procurement process were identified. Risk mitigations were also identified.

2.36 MIC’s decision to proceed straight to direct negotiations at the conclusion of the EoI stage effectively afforded SIMTA the opportunity it had unsuccessfully sought in late 2013 (see paragraph 1.13).

2.37 In the context of achieving value for money, entering into direct negotiations with one proponent can significantly impact the level and balance of competitive tension between the parties to the transaction. MIC’s Negotiation Strategy identified various risks relating to moving away from a competitive procurement process, as well as a number of mitigation strategies for each of these risks.

2.38 The risks from adopting a direct negotiation process were also raised in advice to the Shareholder Ministers by their respective departments in mid-April 2014. The departmental advice was informed by commercial and legal advice, which was provided to Ministers in full, and outlined that:

- given the proposal [is] for 6 months of negotiations, this assumes that there are a significant number of matters of substance to be agreed;

- whilst granting “Preferred Proponent” status is not unusual in commercial negotiations per se, it usually occurs after intense competition and the lodging of final and binding bids—namely bids capable of acceptance and the timeframe for discussion is usually days, not months. This process design ensures that other Respondents do not disengage during the period of negotiation;

- there is no certainty that the period of exclusivity will not be extended once MIC has spent 6 months negotiating with [SIMTA] (which may further diminish competitive tension). Such extensions are common in commercial negotiations once exclusivity is granted; and

- there would be real merit in issuing a Proposal Development Request (PDR) document (in the form contemplated by the Request for EoI)18 and seeking a formal response from [SIMTA] before progressing to negotiations. This is because:

- a PDR document would establish a clear baseline of the Commonwealth’s objectives and preferences against which any final negotiated outcome with [SIMTA] could be objectively assessed (both by MICL and external stakeholders); and

- a formal response provided by [SIMTA] should represent a substantially developed offer capable of acceptance by MICL and, provided the PDR document is appropriately framed, should also reduce the risk of [SIMTA] resiling from its formal offer on key issues during the course of negotiations.

2.39 MIC advised the Shareholder Ministers that ‘some competitive tension’ could be maintained through: the clear commitments given by the preferred respondent in its proposal; and the ability to fall back to a competitive process by keeping two other respondents on ‘stand-by’. The two respondents placed on stand-by were those that scored second and fourth highest. This reflected a request from the third ranked respondent that it not be shortlisted if there were other respondents that were willing and able to develop the MIT.

Were negotiation timeframe risks well managed?

Negotiations took twice as long as had been planned. There was no evidence that MIC contemplated implementing the planned risk management strategy of terminating negotiations and re-engaging with other parties on ‘stand-by’ when it became evident that the negotiations were not proceeding in accordance with the planned timetable.

2.40 On 16 May 2014, MIC informed SIMTA that it intended to continue the procurement process by undertaking direct negotiations with SIMTA ‘for a period of time’, subject to MIC and SIMTA agreeing on the terms of this negotiation. MIC’s Negotiation Plan envisaged that contractual close would occur 24 weeks after a Procurement Process Deed was signed with SIMTA. As noted at paragraph 2.34, MIC’s advice to decision-makers had been that risks associated with direct negotiations could be managed, in part, by MIC terminating the negotiations if timeframes were not being met and re-engaging with two other EoI respondents that would be on stand-by.

2.41 The Procurement Process Deed was signed on 22 May 2014, to govern the conduct of the negotiations. Also on 22 May 2014, MIC informed the two EoI respondents that were being placed on stand-by that:

- it was ‘deferring the commencement’ of a multi-proponent PDR phase ‘for a limited time’ while direct negotiations occurred with SIMTA;

- direct negotiations with SIMTA would be for a period of ‘up to six months’; and

- it ‘may’ seek to re-engage with those respondents ‘in due course’.

2.42 The Procurement Process Deed outlined that the successful completion of Stage 5 was to result in the production of a ‘Final Binding Offer’ (FBO)—synonymous with contractual close. The FBO was also to signify the determination of SIMTA as the ‘preferred proponent’ and the release of the remaining qualifying EoI respondents from stand-by. Consistent with advice to the Shareholder Ministers, a key condition of the deed was that if the parties failed to complete Stage 5 by the 20 November 2014 termination date, MIC would cease direct negotiations with SIMTA.

2.43 The effectiveness of this approach as a control in maintaining competitive tension during direct negotiations was reliant on timely achievement of the approval hurdle milestones; and ensuring that documentation forming the basis of the FBO was sufficiently detailed. Table 2.2 highlights that considerable delays occurred throughout the negotiations.

Table 2.2: Stages for direct negotiations between MIC and SIMTA

|

|

Approval hurdle to be achieved |

Forecast date |

Completion date |

|

Stage 1 |

MoU Agreement on Fundamental Matters |

Mid-July 2014 |

12 September 2014 |

|

Stage 2 |

Term Sheet and largely complete precinct master plan prepared by SIMTA |

31 July 2014 |

20 November 2014 |

|

Stage 3 |

Detailed negotiation of all transaction documents |

25 September 2014 |

2 April 2015 |

|

Stage 4 |

MIC Board and Australian Government approvals |

23 October 2014 |

21 April 2015 |

|

Stage 5 |

Contractual close |

20 November 2014 |

3 June 2015 |

Source: ANAO analysis of MIC records.

2.44 In September 2014, MIC advised its Board that the MoU Agreement on Fundamental Matters discussions were far more detailed and lengthy than either MIC or SIMTA first contemplated, and due to this, the parties brought discussions for that stage to a conclusion by documenting the position on each fundamental matter whether agreed or otherwise. For matters yet to be agreed, the position of each party was recorded with a commitment to resolve the matter in Stage 2 (proposal negotiations). The MIC advice did not contemplate terminating negotiations and re-engaging with the two parties it had placed on stand-by.

2.45 The parties agreed an aggressive program to finalise the remaining transaction documentation, but were unable to make up for the time lost. This resulted in eight amendments to the Procurement Process Deed, each with the effect of extending the deed’s termination date. There was no evidence of MIC, prior to any of these amendments, contemplating the merits of implementing the planned risk management strategy of terminating negotiations and re-engaging with the two parties on stand-by.

2.46 Six months after entering into direct negotiations and shortly after finalising the detailed Term Sheet on 20 November 2014, media releases19 were published announcing that MIC and SIMTA had reached an agreement to develop the Moorebank project. As reflected in commercial and legal advice commissioned by DIRD and Finance, by this point in time and based on the process that had eventuated, MIC’s capacity to pursue an alternate process or new proposals had become limited and likely to carry substantial risk. On 11 December 2014, MIC wrote to the two other EoI respondents it had placed on stand-by thanking them for their time and effort in participating in the procurement process.

2.47 Contractual close was reached six months after the announcement was made, and more than six months later than had been intended when the decision had been taken to enter into direct negotiations.20

Did negotiations secure the expected contractual commitments?

Negotiations were expected to commence after MIC had obtained a binding commitment to the key elements of the successful respondent’s expression of interest. No such commitment was obtained. There is no evidence that going to direct negotiations at an early stage produced a better outcome than was achievable under the original planned procurement approach of getting firm and binding offers from two or three competing parties to select from.

The direct negotiations secured contractual commitments to the development and operation of intermodal freight terminals and warehousing, as well as to an open access regime for the terminals. Between the commencement of direct negotiations and the final contracted outcome, MIC agreed to arrangements that have increased the Australian Government’s financial contributions and contingent liabilities (as compared with those proposed within the successful proponent’s EoI); mitigated private sector exposure to demand risk; reduced the coverage and effectiveness of the access regime; and reduced the revenue streams to the Australian Government.

2.48 According to May 2014 departmental advice, and consistent with the approach suggested to the departments by their advisers (outlined at paragraph 2.38), the May 2014 Procurement Process Deed was to bind SIMTA to the ‘commitments’ expressed in its EoI submission. Similarly, in September 2017, MIC advised the ANAO that:

The first step in the direct negotiation was to secure SIMTA’s commitment to the key elements of its EoI response. This is recorded in Schedule 1 to the Procurement Process Deed executed by MIC and SIMTA on 22 May 2014.

2.49 The ANAO’s analysis is that the terms of the Procurement Process Deed did not involve MIC obtaining a commitment from SIMTA to key elements of its EoI response. Rather, the Deed set out the parties’ rights and obligations in relation to the conduct of the direct negotiations process. Further, the express purpose of Schedule 1 to the Deed was to ‘summarise the EoI response, including the respondent’s response to MIC’s written evaluation questions and the evaluation interview’. There was no commitment expressed in the Schedule, or elsewhere in the Deed, to the EoI response. The lack of any such commitment was consistent with:

- the EoI request having been issued by MIC on the basis that no legal or other relationship or obligations would arise between any Respondent and MIC unless and until binding legal documentation was signed, and that acceptance of any EOI response would not create a binding contract between MIC and the respondent; and

- responses to the EoI request not being in the form of binding bids (including clear commitments) that were capable of acceptance.

2.50 Key elements of the transaction changed significantly during the course of negotiations compared to the commercial arrangements envisaged by the EoI request and in SIMTA’s EoI response. The ANAO’s analysis is that the direct negotiations did not secure a contractual commitment to important elements of the Australian Government’s preferred approach to some matters (as articulated in the Request for EoIs); or to all key elements of SIMTA’s EoI response. This was the case in relation to:

- the Australian Government’s financial contributions and contingent liabilities increasing over the course of negotiations. For example, the successful EoI had indicated that no government subsidies would be sought to fund connecting rail infrastructure, or for the relocation of Moorebank Avenue.21 The Fundamental Matters MoU agreed in September 2014 stated that the Australian Government would fund a portion of the Southern Sydney Freight Line rail access and that SIMTA’s contribution towards relocating Moorebank Avenue would be capped at $20 million. The final contracted outcome reflected the same cap in relation to Moorebank avenue, but involved the Australian Government funding the entirety of the Southern Sydney Freight Line rail access22;

- the Australian Government being prohibited from divesting its interests to rivals of the successful respondent,23 as opposed to its original preference for an unfettered privatisation process;

- the mitigation of private sector exposure to demand risk. The successful EoI response had stated that the Australian Government (through MIC) would not be required to assume any demand risk for the project. The negotiated outcome maintained a position that demand risk is predominantly with the terminal operators but private sector exposure to demand risk is mitigated by the contractual arrangements:

- providing a number of grounds on which terminal capacity is not required to be expanded even in circumstances where there is unmet demand; and

- allowing the operator to set the prices it charges for terminal services and warehousing at market rates, without any reference to its costs with the contractual arrangements involving concessions from the Australian Government that reduce those costs;

- the value of land rent revenue streams from SIMTA diminishing progressively throughout negotiations from a starting position of ‘market value’ set out in the EoI response to a contracted position well below market rates;

- concerns raised by the Shareholder Ministers’ departments that the contractual arrangements should guard against the risk of the IMEX terminal being delivered, but not the interstate terminal. The contractual arrangements seek to address this issue, but there remain some circumstances under which the obligations to develop the interstate terminal to its ultimate capacity may be terminated, with SIMTA retaining its rights and obligations in relation to the IMEX terminal and rail access;

- MIC making a number of significant concessions in regard to warehousing development, most notably the granting of 99-year warehousing ground leases that will survive contract termination; and

- the contractual arrangements excluding certain aspects of terminal services that the EoI had identified would be captured as part of the Open Access Regime. In addition, the compliance arrangements for the Regime are not as strong as was envisaged in the EoI.

2.51 Details of the ANAO’s analysis are provided in Appendix 3.

Was probity in the procurement process well managed?

There were shortcomings in the management of probity. For example, the probity plan did not apply to all stages of the procurement process. In addition, a probity adviser and a separate probity auditor were appointed later in the procurement process than is desirable through processes that did not involve open and effective competition for the roles. Further, MIC’s response to the probity audit of the EoI process did not adequately address each of the findings that underpinned the auditor’s recommendations.

Probity framework

2.52 In May 2013, MIC appointed a probity adviser for the approach to the market. MIC did not conduct an open tender process for this role. Rather, it obtained and evaluated three quotes from firms recommended by its legal adviser (Herbert Smith Freehills). The contract specified a capped monthly fee of no more than $30 000 over a thirteen and a half month period representing a total potential fee value of $405 000. An engagement of this value should have been subject to an open tender under MIC’s procurement policy.

2.53 The statement of works for the probity adviser developed by MIC emphasised that its status as a GBE meant that it was not required to comply with Australian Government probity requirements. Rather, MIC was seeking to ‘work with the adviser to apply commercially appropriate and pragmatic probity practices for competitive procurement processes with a total project value of approximately $1 billion, and to implement good probity practices within its day-to-day business’. The adviser was paid a total of $54 130 for work undertaken between November 2013 and April 2015. Although the adviser was appointed in May 2013, no work was invoiced as having been undertaken prior to November 2013.

2.54 MIC also engaged a probity auditor (Risk Reward Pty Ltd)24 for the EoI and the direct negotiations processes. The July 2014 engagement was through a non-competitive process of MIC’s legal adviser seeking a quote from a provider that had previously (in December 2013) been identified by MIC. In September 2017, MIC advised the ANAO that the firm had been ‘recommended by MIC’s former General Counsel’ and that ‘given the relatively small size of the consultancy (approximately $25 000), an open tender was not adopted’.25

2.55 A probity plan was produced, although advice from MIC’s probity adviser had been that probity protocols would have been a better approach. The probity plan did not apply to the Registration of Interest process or the September 2013 market sounding exercise. The ANAO sought advice from MIC as to why a probity plan was not in place for the full extent of the engagement with the market. MIC’s advice to the ANAO in September 2017 was that:

The market sounding process was market research / information gathering for MIC. It was not proponent procurement or selection. The probity adviser reviewed and commented on the RoI documents and market sounding process, and his feedback was taken into account.26

2.56 The appointment of a probity adviser and probity auditor, and the establishment of a probity plan also occurred after MIC had made its major adviser appointments.

EoI process

2.57 A draft report from the probity adviser on the EoI process was provided to MIC on 1 May 2014. MIC amended the draft report, prior to the probity adviser’s final sign-off, to state that the adviser had attended ‘key meetings’ and that he endorsed the proposed approach of entering into direct negotiations. Accordingly, the adviser’s report signed on 1 May 2014 stated that:

- the EoI processes had been conducted fairly and properly and in a manner consistent with all probity requirements and those of procedural fairness; and

- it supported the entering into of exclusive negotiations with the first-ranking respondent ‘given the clear gap between this respondent and the other respondents’.

2.58 The probity auditor’s September 2014 report on the EoI process concluded that, apart from three areas, it believed the probity requirements were met during the EoI phase, including in relation to evaluation of the bids and the decision to proceed with direct negotiations with SIMTA. The three areas of findings and related recommendations addressed: management of conflicts of interest; transparency and accountability matters; and access security over confidential data and documentation.

2.59 MIC’s response adequately addressed the findings and recommendation relating to access security. But its response did not adequately address each of the findings that underpinned the probity auditor’s recommendations in the other two areas (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Management response to probity auditor findings and recommendations

|

Finding |

Recommendation |

ANAO analysis of MIC’s response |

|

Conflict of interest declarations by consultants addressed personal conflicts but not those on behalf of their employer organisations. |

Undertakings be obtained from consultant organisations that they are not assisting any EoI respondents. If they are, they should be asked to provide details of how the organisation is managing the conflict. |

The recommended undertakings were not sought. Instead, MIC’s response was that it was in the process of obtaining confirmation from each key adviser or consultant organisation that it has appropriate internal processes in place to check for conflicts of interest. Confirmations were to be sought on or before the 30 September 2014. The ANAO sought from MIC all confirmations obtained (as the ANAO had been unable to locate this information in MIC records). This revealed that MIC had not implemented the action it had committed to in its response to the probity audit. MIC advised the ANAO in October 2017, that it ‘has no record of conflict of interest declarations from consultant organisations, only employees within the consultant companies’. |

|

Minutes of the meetings of the Evaluation Panel and the Implementation Committee were not compiled and reports were unsigned and undated meaning the Panel and Committee had not formally reported in a transparent and accountable manner in accordance with the probity plan. |

Noting that the Negotiation Plan for the direct negotiations stage did not require minutes/notes to be compiled of each meeting, to satisfy the probity principles of transparency/ accountability and fairness/impartiality described in the Probity Plan, it was recommended that formal minutes/notes be compiled. |

MIC considered it was ‘impractical’ to keep meeting minutes/notes. Instead, its response to the recommendation:

In this latter respect, evidence provided by MIC to the ANAO in September 2017 indicated that 46 direct negotiation meetings had taken place and formal minutes recorded. The ANAO’s analysis of these records indicated that the probity adviser was present at 35 of these. Additional records examined by the ANAO suggest that at least a further 85 negotiation meetingsᵃ—for which there were no minutes or formal documentation—may have taken place between MIC and SIMTA. |

Note a: These further negotiation meetings predominantly involved discussions between senior MIC and SIMTA employees (including MIC’s Chair and CEO) without the presence of their respective advisers. The occurrence of these meetings was identified by the ANAO from examination of MIC calendar entries and email correspondence.

Source: ANAO analysis of MIC records.

Direct negotiation process

2.60 On 2 April 2015, MIC sought a sign-off from the probity adviser on the direct negotiations process. MIC informed the probity adviser that a final binding offer had been received that day from SIMTA, provided the adviser with the covering letters and outlined that the final binding offer would be available to view in MIC’s offices from 7 April 2015. On Saturday 4 April 2015, the probity adviser provided a sign-off that the probity adviser had:

- reviewed the final binding SIMTA offer27;

- monitored the entire negotiation process and attended all28 high level negotiation meetings to ensure that all probity requirements were met; and

- concluded that: ‘the process was conducted in a manner consistent with the Procurement Process Deed, principles of procedural fairness and all probity requirements and that, in view of the meeting of Commonwealth objectives with relatively low Commonwealth capital investment and SIMTA adopting the majority risk, value for money for the Commonwealth is able to be obtained’.

2.61 The probity auditor’s August 2015 report on the direct negotiation process stated that it was satisfied that the key controls put in place to mitigate the major probity risks to MIC were appropriate and operated effectively during the direct negotiation process.

What advice on the value for money of the project was provided to Shareholder Ministers?

Advice on the project’s progress and whether value for money was expected to be obtained was provided to Ministers at key milestones. At the conclusion of the negotiation process, MIC advised the Shareholder Ministers that the outcome represented ‘excellent value for money’. Ministers were separately advised by their departments that the negotiated outcome represented value for money.

2.62 Advice in respect to the project’s optimal delivery mechanism and its value for money has been provided to Ministers over a substantial period of time. Key advice was typically provided leading up to important project milestones, such as when the project’s detailed business case was finalised in February 2012; the selection of a preferred respondent in April 2014; and prior to the execution of the project contracts in June 2015.

Initial Australian Government approval

2.63 Initial Australian Government approval for the MIT was given in April 2012 and included $887 million29 for the implementation of the project via a dedicated Government Business Enterprise.30 The Government’s decision was on the basis of comprehensive departmental advice, which was underpinned by the project’s detailed business case.

2.64 A benefit cost ratio (BCR) was calculated for the MIT as part of its business case, in order to ensure the economic benefits outweighed the economic costs. This analysis indicated that the project showed a BCR of 1.72 and a positive net present value of $1 billion.31 This is the BCR referred to by Infrastructure Australia in its evaluation of the business case.32

2.65 The BCR of 1.72 did not take into account the cost to the Australian Government for the relocation of the School of Military Engineering (SME) from the Moorebank site—which was explicitly linked to the project—as these costs were considered as part of a separate Moorebank Units Relocation (MUR) business case compiled by the Department of Defence. In considering the Defence-specific costs and benefits, the MUR business case:

- identified that 78 per cent of the total cost of the Moorebank Units Relocation project were directly attributable to the MIT—as at September 2013, these costs were in the vicinity of $517 million;

- noted that the MUR project was ‘driven by the Government’s need to develop an Intermodal Terminal on the Defence land at Moorebank that lies between Moorebank Avenue and the Georges River’; and

- did not calculate a BCR for the MUR project.

2.66 Department of Finance advice was that the BCR for the project was 1.27 taking into account the Defence relocation costs.33

Advice provided throughout contractual negotiations

2.67 Following the September 2013 Federal Election, the new Shareholder Ministers approved the continuing operations and activities of the MIC in line with advice received from their respective departments.

2.68 This approval saw MIC continuing to be responsible for the procurement and, later, the contractual negotiations for the development of the MIT. The formal and informal governance arrangements between MIC and the Shareholder Ministers’ departments involved regular liaison between officials, and the seeking of approvals from the Ministers at key milestones. These milestones have included Shareholder Ministerial agreement that MIC:

- release its Request for EoI documentation in December 2013;

- depart from its published procurement process by entering into direct (one-to-one) negotiations with SIMTA;

- formalise high-level commercial arrangements via a ‘Fundamental Matters’ Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with SIMTA in September 2014;

- accept a detailed Term Sheet via an offer made by SIMTA in November 201434; and

- execute the finalised Development and Operations Deed on 3 June 2015 to achieve contractual close.

2.69 These approvals were sought and received by way of letters between the MIC Chair and the Shareholder Ministers. Advice and recommendations from the two Shareholder Ministers’ departments were often accompanied by copies of advice from the departments’ legal and commercial advisers.

Advice on the negotiated outcome

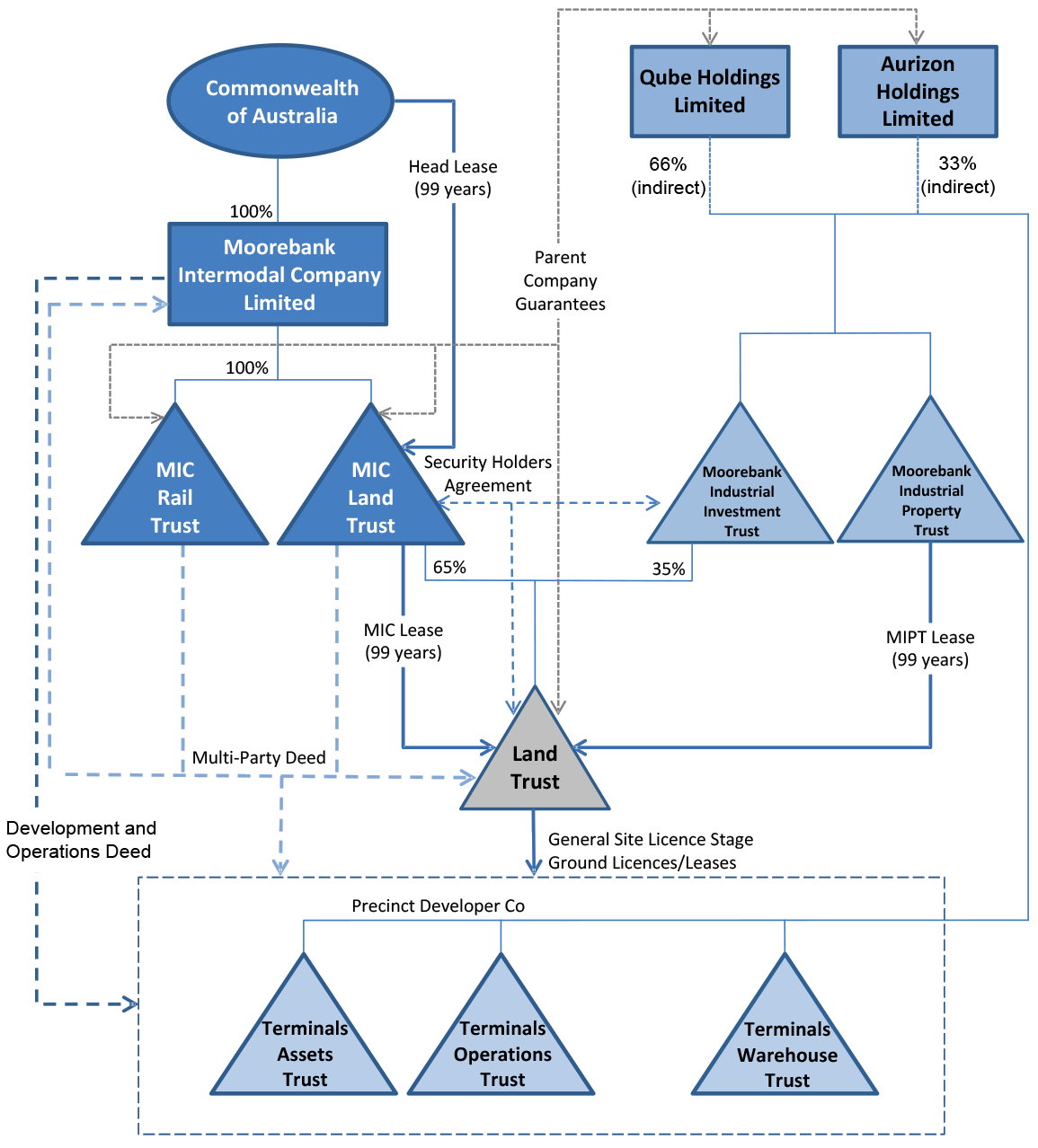

2.70 In April 2015 MIC wrote to Shareholder Ministers on the outcome of the negotiations. The settled commercial and contractual arrangements for the delivery of the project included:

- MIC assuming a landlord role, with no investment in the development of the terminal, warehousing or precinct infrastructure;

- all land required for development of the intermodal terminal would be leased to a land holding entity (Land Trust), jointly owned by MIC and SIMTA in proportion to the areas of developable land contributed (with this proportion being 65.63 per cent from MIC and 34.37 per cent from SIMTA);

- Land Trust leasing its land to Precinct Developer Co (PDC, a wholly owned SIMTA/Qube subsidiary), which will:

- develop and operate the interstate terminal, IMEX terminal, associated precinct infrastructure and warehousing for 99 years, subject to certain conditions; and

- assume the demand risk for the project;

- MIC funding the provision of the rail connection between the Southern Sydney Freight Line (SSFL) and the terminal; and

- MIC entering into a monitoring and enforcement role in respect to PDC adhering to the contractual open access regime.

2.71 Figure 2.1 provides a simplified illustration of the contractual relationship between the parties to the transaction.

Figure 2.1: Simplified MIT transaction structure as at April 2015

Source: MIC records.

2.72 The Shareholder Ministers were advised by MIC that the following attributes of the commercial agreement that had been reached meant that the project represented ‘excellent’ value for money:

- SIMTA’s willingness to take the demand risk and to fund the majority of the investment required to develop the terminal. MIC suggested that the Australian Government’s contribution was limited to the land and up to $370 million in funds, which ‘was about $1 billion35 less than foreshadowed in the 2012 business case’.36 Further, the Australian Government would earn a real equity return on its contribution over the longer term;

- the size of SIMTA’s contribution—being its land, valued at $105 million, and $693 million of capital expenditure on terminals and precinct infrastructure, consisting of $448 million over the period 2016 to 2020 (primarily on initial terminal development and associated infrastructure) and $244 million over the period 2021 to 2027 (primarily on terminal expansion and associated infrastructure)37; and

- SIMTA is obliged to develop and operate the intermodal terminal in accordance with contractual requirements that include development to an agreed master plan, and operation on principles of non-discrimination.

2.73 Separate but largely similar advice was provided to the Shareholder Ministers by their departments. Finance’s advice to its Minister was that ‘while there are trade-offs in the final negotiated outcome, MIC and SIMTA’s proposal represents a value for money proposition’. DIRD’s advice to its Minister was that ‘while there are trade-offs in the final negotiated outcome, we conclude that on balance, the MIC-SIMTA proposal represents a value for money proposition’.

3. Access arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether non-discriminatory open access is likely to be available within all aspects of the intermodal precinct.

Conclusion

It is not possible to provide assurance that non-discriminatory open access is likely to be available within all aspects of the intermodal precinct given:

- the contractual framework does not apply to all elements of terminal operations, partially applies to the rail shuttle service between Port Botany and the MIT and internal transfers within the terminal precinct, and does not apply to warehouse operations;

- most of the key detailed documents that are required for implementation of effective open access arrangements have yet to be developed; and

- significant non-compliance is permitted before enforcement action can be taken.

Why is open access provided through contractual arrangements?

Notwithstanding that the preferred tenderer would gain exclusive access to a significant tract of Commonwealth land, MIC’s view was that an open access regime administered through contractual arrangements was the only mechanism that would attract private sector interest in the development of the project. The alternative approach preferred by the Shareholder Ministers’ departments was an access undertaking under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 which would then be administered by the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission. The 2013 approach to the market did not seek to test whether an access undertaking would deter private sector interest in the project.

3.1 An Australian Government policy objective for the Moorebank Intermodal Terminal (MIT) is that it be a flexible and commercially viable common user facility that is available on reasonably comparable terms to all rail operators and other terminal users.