Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Delivery of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy in Remote Indigenous Communities

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s management of initiatives to supply low aromatic fuel to Indigenous communities.

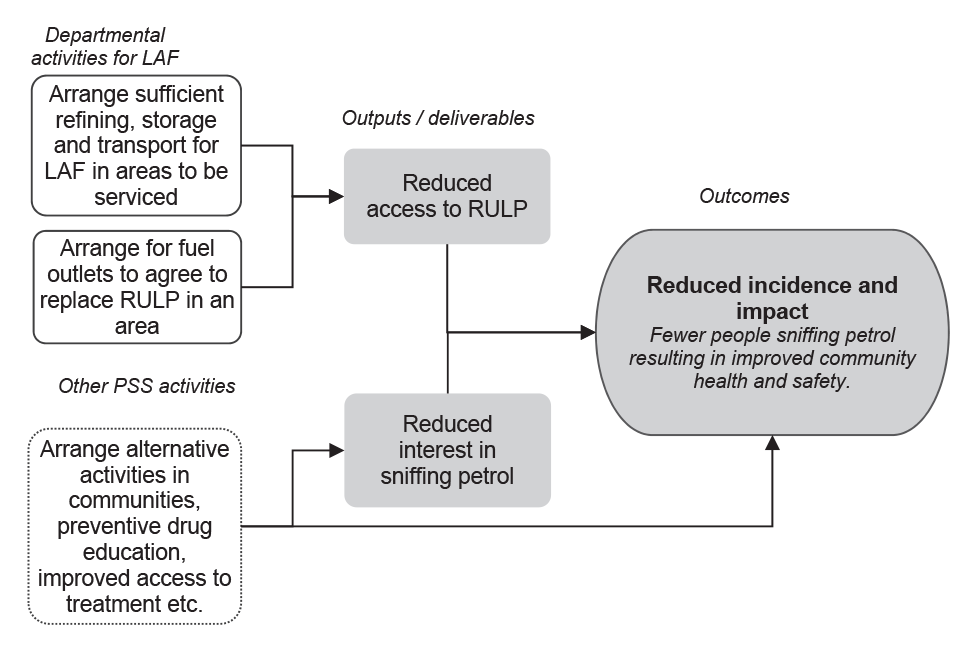

Summary

Introduction

1. In the late 1990s, remote Indigenous communities concerned about the incidence of petrol sniffing and its negative consequences requested assistance from the Australian Government to support efforts to tackle outbreaks. The effects of petrol sniffing on communities include: increased rates of domestic violence; petty crime such as theft and vandalism; assaults; family and social disruption as well as affecting the health of the individuals involved in sniffing. Socially, the emotional and financial impacts on the community and the health and justice systems are significant, as is the cost of treating the short and long-term health effects of sniffing related harm.1

2. In response to concerns raised, the Australian Government commenced the Comgas Scheme in 1998, which subsidised the provision of Avgas, a low aromatic leaded aviation fuel, to participating communities. The lower aromatic formula does not produce the same intoxicating effects as regular petrol. Avgas was unattractive to petrol sniffers but was not a viable long term option as Australia was phasing out leaded fuels generally. In 2005, a low aromatic unleaded fuel (LAF) was developed by BP Australia Pty Ltd (BP) as a substitute to regular unleaded petrol (RULP) and the Australian Government commenced supporting its distribution to communities.

3. Petrol sniffers tend to be young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and marginalised groups.2 The Senate Community Affairs References Committee in 2006 documented underlying causes of petrol sniffing in Indigenous communities as including: poverty and hunger; boredom; the cultural and social impacts of colonisation and interaction with the non-Indigenous community; a lack of employment and education opportunities; and social factors such as family breakdown, neglect, and peer group pressure.3 The sniffing of volatile substances is not confined to petrol. Other commonly available products known to create similar effects include aerosol sprays, such as deodorant, glue, spray paint and butane gas (lighter fluids). Addressing the use of these other volatile substances is not currently the primary focus of the Australian Government’s efforts to reduce petrol sniffing.

The Petrol Sniffing Strategy

4. Building on the earlier Comgas Scheme, the Australian Government established the Petrol Sniffing Prevention Program (PSPP) in February 2005 as a mechanism to supply LAF to participating communities. PSPP was implemented by the former Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) and became the department’s contribution to the broader whole-of-government Petrol Sniffing Strategy (PSS). The PSS was developed in September 2005 as a collaborative approach between the Australian and the Western Australian, South Australian and Northern Territory governments, with the objective of reducing the incidence and impact of petrol sniffing. Under the PSS, the respective jurisdictions agreed to focus on developing: consistent legislation; appropriate levels of policing; further roll out of LAF; alternative activities for young people; treatment and respite facilities; communication and education strategies; strengthening and supporting communities; and evaluation. These activities are collectively referred to as the Petrol Sniffing Strategy Eight Point Plan.

5. Prior to September 2013, the Australian Government contribution to the PSS was delivered by four departments. DoHA delivered the LAF component and undertook research and data collection; the former Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs was responsible for overall coordination of the strategy and providing funding for community strengthening initiatives. The Attorney-General’s Department delivered the Indigenous justice components including the surveillance of trafficking in volatile substances and other drugs and the former Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations provided education and work-related diversionary activities targeting youth at risk of sniffing.

6. Following the 2013 Federal election, responsibility for the delivery of Australian Government Indigenous programs was transferred to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), including activities in relation to the PSS. Subsequently, Indigenous program funding arrangements were consolidated in 2014, which resulted in approximately 150 individual programs and activities being brought together into the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS). Within the IAS there are five program areas, and organisations may apply for grant funding to support the delivery of relevant activities. Petrol sniffing activities generally fall within the Safety and Wellbeing Programme. While the IAS is mainly a grants program, the Government has agreed to implement specific initiatives through the program, including the supply of LAF. As at 21 April 2015, PM&C was negotiating agreements with various organisations for the provision of services under the IAS.

7. Since its establishment, the PSS has been periodically expanded to enable the supply of LAF to new areas. An initial 41 sites4, principally in the Central Desert Region5, received LAF in 2005.6 In the 2006–07 Federal Budget, $20.1 million over four years was allocated to extending the strategy to two more zones: the ‘Extended Central Desert Region’ and the East Kimberley. Additional sites in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland outside the identified priority areas were also supplied with LAF and included in the strategy during this time. A further $12 million over three years was allocated by the Australian Government to supply LAF to fuel outlets in Alice Springs from 2007–08. To address the need for continuing efforts to reduce the incidence and impact of petrol sniffing, the PSS became an ongoing Budget measure in 2008.

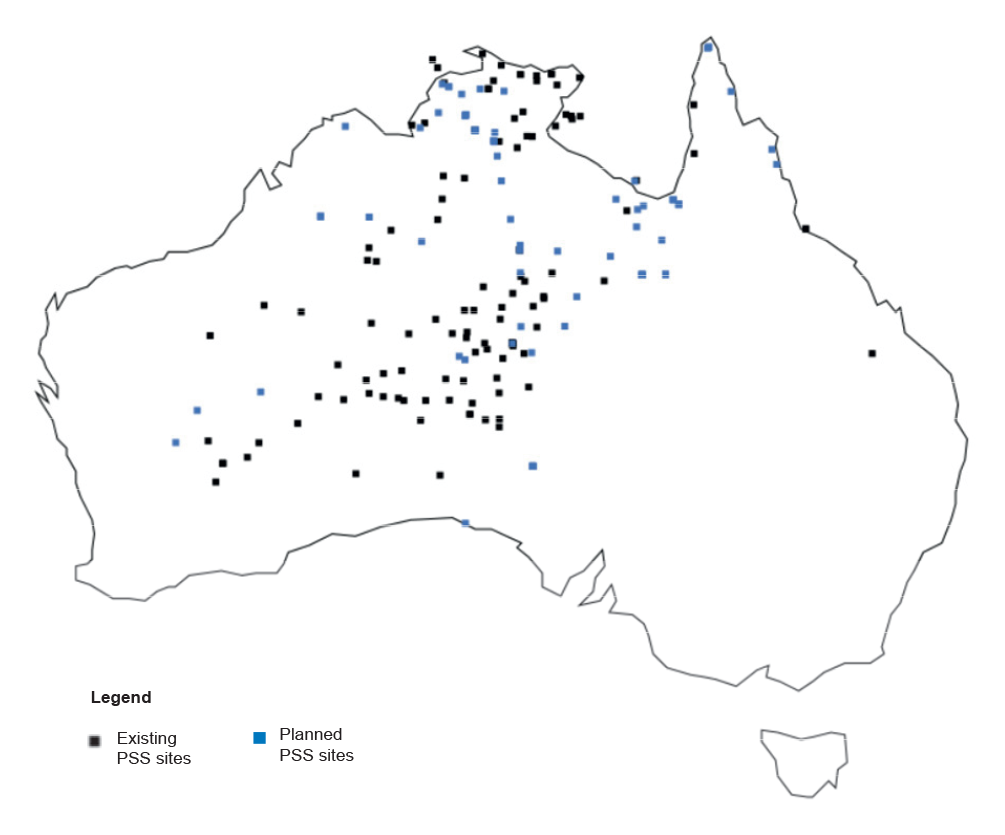

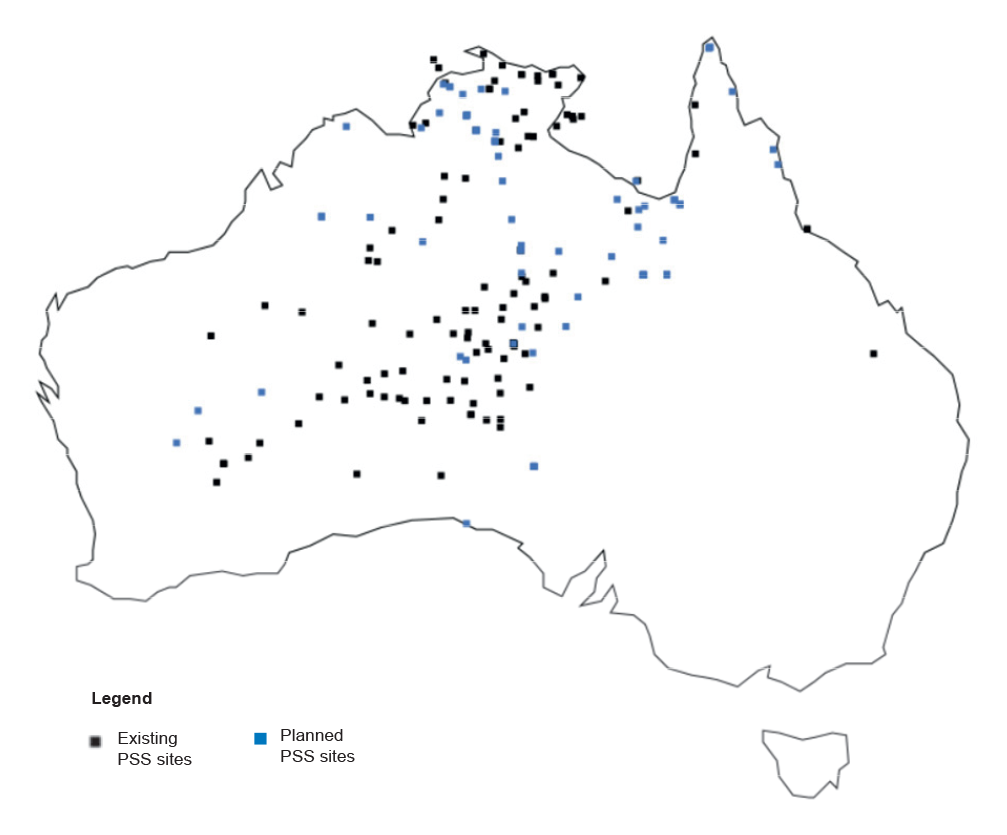

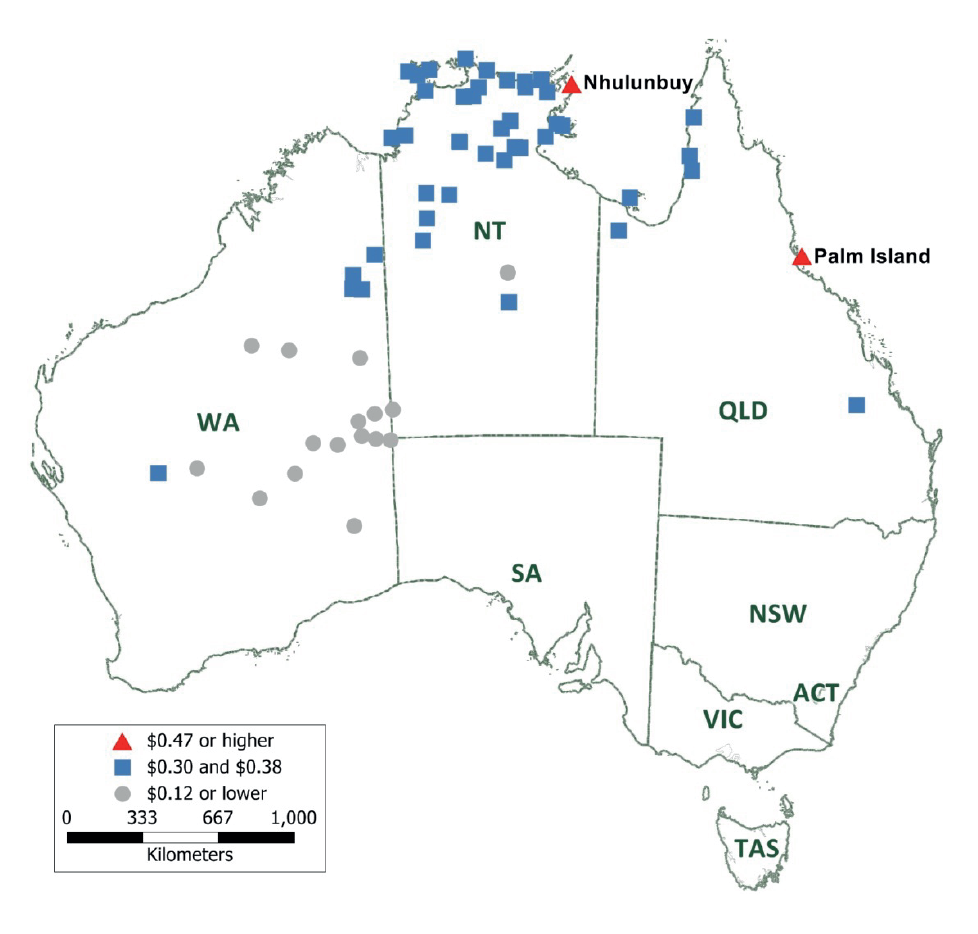

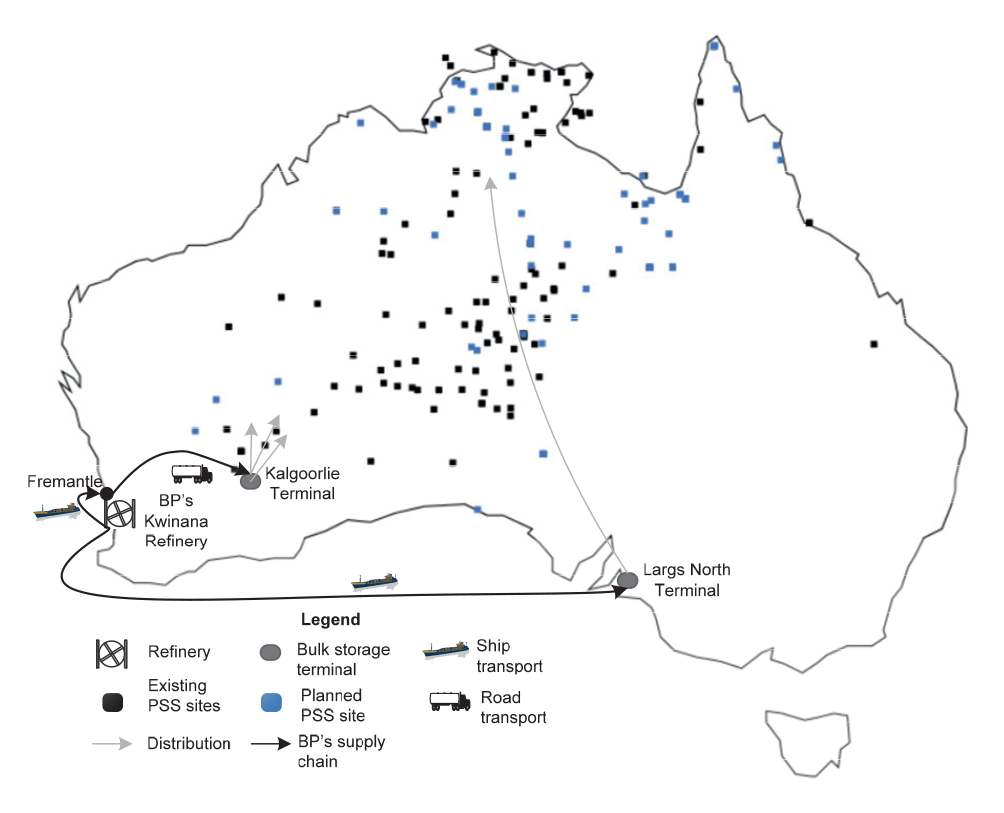

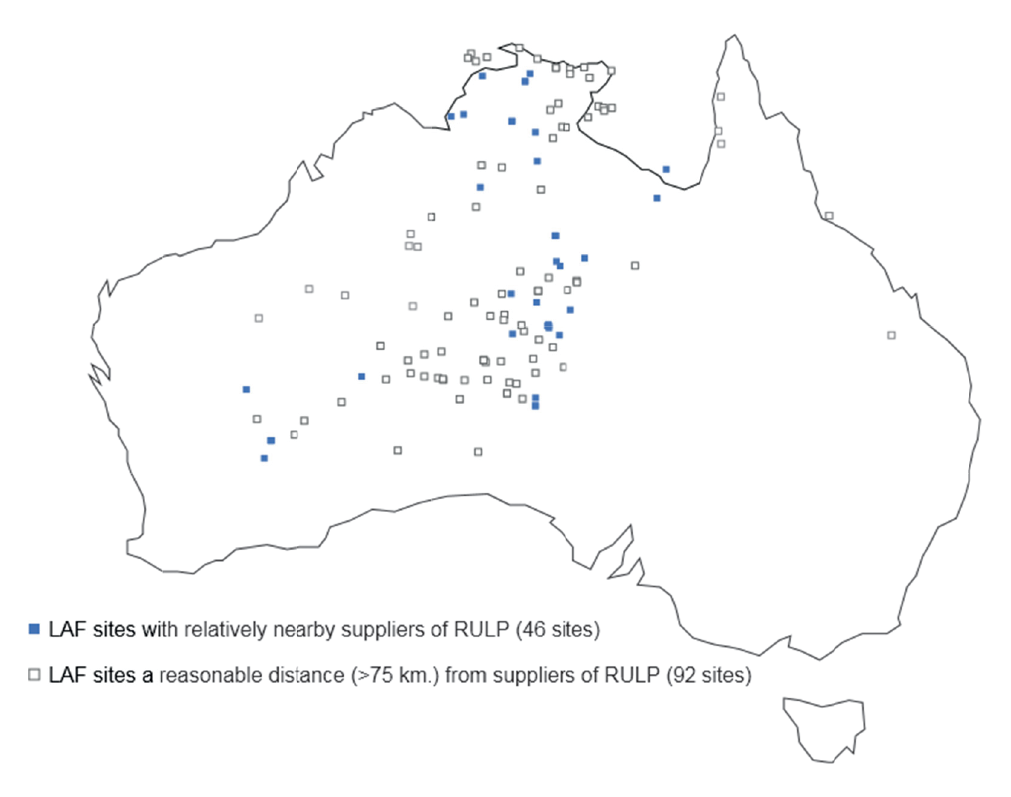

8. By 2010, LAF was being supplied to 106 sites. As part of the 2010–11 Budget, the Australian Government announced a new Budget measure, Enhancing the Supply and Uptake of Opal Fuel7, which committed a further $38.5 million to supply LAF and included funding to access bulk fuel storage facilities in Darwin. As part of this measure an additional 39 sites covering 11 communities across the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia were to be targeted. As at January 2015, LAF was available at 138 sites. The distribution of current and planned LAF sites across the Northern Territory, South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland, as at January 2015, is shown in Figure S1.

Figure S.1: Map of current and planned LAF sites, as at January 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C data.

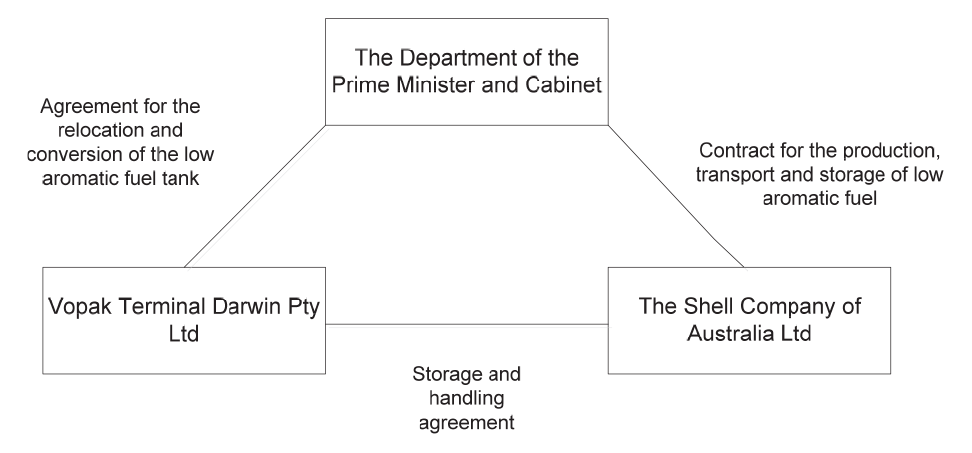

9. As LAF is required to be produced, distributed and stored separately to RULP, there are additional costs involved in supplying it to Indigenous communities. To prevent these costs acting as a barrier to the purchase of LAF, the Australian Government subsidises its production and distribution so that LAF may be made available at the same price to fuel outlets as RULP. Funding agreements for the production, storage and distribution of LAF were entered into at various times between 2005 and 2011, when these elements of the PSS were administered by the former DoHA. Between 2005 and 2012, the Australian Government funded BP to produce LAF under a grant arrangement. In 2012, to support an expansion of the PSS and after a procurement process, production contracts were entered into with BP and with The Shell Company of Australia Ltd (now known as Viva Energy Australia). Also, in December 2013, the Australian Government entered into an agreement with Vopak Terminal Darwin Pty Ltd (Vopak) to construct a bulk storage fuel tank to support the expansion of the PSS by allowing an increased supply of LAF in northern Australia.

10. The PSS is administered by PM&C and, as mentioned in paragraph 6, is funded as a specific initiative under the Safety and Wellbeing Programme of the IAS. Annual expenditure for the LAF component of the PSS over the last two financial years has been on average $24 million. Expenditure for 2014–15 is also expected to be approximately $24 million.

Legislation

11. In targeted regional and remote areas where LAF has been rolled out, the majority of fuel outlets have participated voluntarily. Some outlets, however, have chosen not to stock the fuel, creating a potential supply pathway for RULP into vulnerable communities which may reduce the effectiveness of efforts to control petrol sniffing. In March 2012, a Private Member’s Bill, the Low Aromatic Fuel Bill 2012, was passed by Parliament and received Royal Assent on 14 February 2013.8 The Low Aromatic Fuel Act 2013 (the Act) provides the responsible Minister9 with discretionary powers to designate a fuel control area and to determine the requirements relating to the supply, transportation, possession and storage of fuel in those areas. The Act aims to promote the supply of LAF in designated areas by prohibiting the supply of RULP. Powers under the Act have not been used as at April 2015 and the PSS continues to operate on the basis of voluntary participation. PM&C advised that two outlets previously reluctant to participate in the PSS voluntarily switched to supplying LAF after the bill passed.

Administrative role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

12. PM&C is responsible for the implementation of Australian Government components of the PSS, including providing advice and information on the strategy as requested by the Minister and Parliament. With regard to the provision of LAF, PM&C’s main functions include:

- managing the contracts for the subsidised production of LAF;

- managing the subsidy arrangements with petrol distributors;

- negotiating and managing the agreement for the construction of a bulk storage facility in Darwin;

- preparing communities to receive LAF, including consultation and logistical arrangements;

- developing and managing a communication strategy; and

- managing ongoing research and data collection for the PSS to assess the effectiveness of the provision of LAF.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

13. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s management of initiatives to supply low aromatic fuel to Indigenous communities.

14. To conclude on this objective, the ANAO’s high-level criteria considered: the service delivery arrangements in place to supply LAF to targeted Indigenous communities; the implementation of the expansion of the PSS, and the arrangements in place to monitor the supply of LAF; and assess the impact of its supply in line with the Government’s expectations.

Scope

15. The audit focussed on the administration of arrangements to support the supply and distribution of LAF. In particular the audit examined the procurement process conducted in 2011 for the production, transport to storage and storage of LAF which resulted in the contracts and agreements referred to in paragraph 9. The audit also examined the monitoring and reporting arrangements for the PSS, particularly in relation to the supply of LAF.

Overall conclusion

16. Through the Petrol Sniffing Strategy (PSS), the Australian Government has supported initiatives to reduce the incidence and impact of petrol sniffing in remote Indigenous communities since 2005.10 The key element of the PSS is to subsidise the production of low aromatic fuel (LAF) so that it replaces regular unleaded petrol (RULP) in areas at risk of petrol sniffing outbreaks, without the higher production costs acting as a barrier to its uptake. While there are many underlying causes of petrol sniffing, generally associated with young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and marginalised groups, research results have indicated that the introduction of LAF has been successful in contributing to reductions in the incidence of petrol sniffing. For this reason, additional funding has been made available by the Australian Government to expand the supply and distribution of LAF.

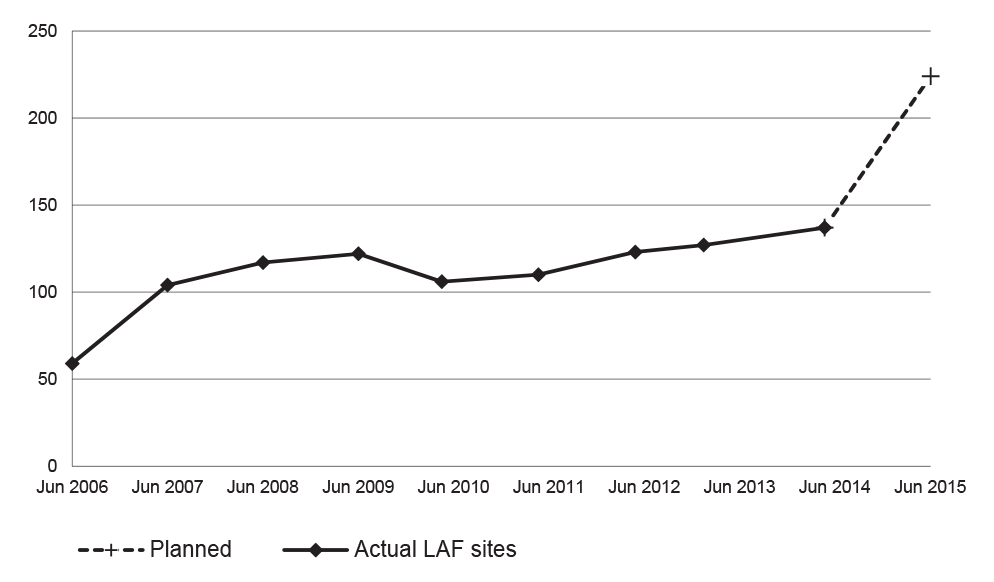

17. From an initial 41 sites in June 2005, the PSS expanded and, as at January 2015, LAF was available in 138 sites associated with 78 Indigenous communities in Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory. Consistent with the policy objective of the PSS, these sites are located in regional and remote areas of Australia. While the number of sites has increased, the overall annual volume of LAF produced has largely remained stable since 2007–08 with approximately 21 megalitres being produced on average each year.11 No performance targets have been set in relation to the volume of LAF produced and distributed, although contracts with LAF producers allow for an annual production of up to 53 megalitres.

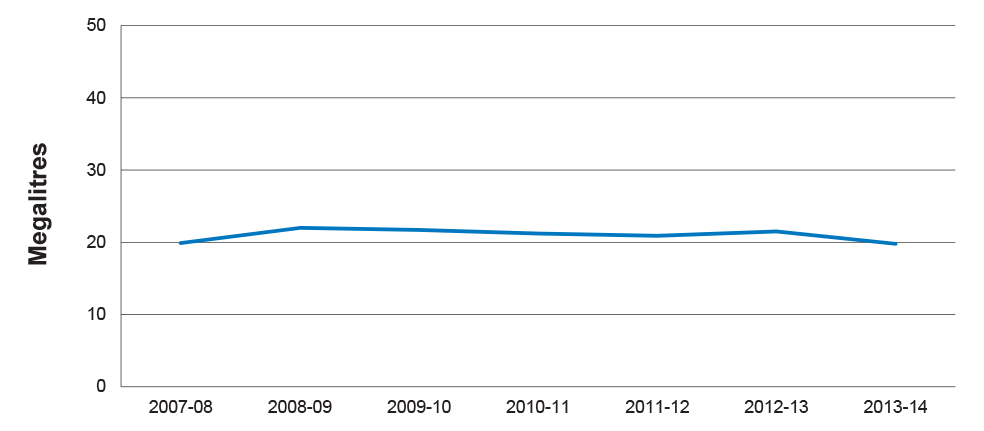

18. In the most recent expansion of the PSS in 2010–11, the Australian Government provided additional funding to include 39 sites covering 11 communities in Northern Australia, with an associated increase in annual volume of production of LAF. As well as supporting extra production capacity, a significant element of the increased funding was to provide for additional storage facilities as the lack of bulk storage had been identified as the key barrier to expanding the PSS in northern Australia. Following a select tender,12 the department responsible for providing LAF, the then Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA), entered into contracts with two major fuel producers to supply LAF to different regions of Australia. The development of additional storage infrastructure was initially included by DoHA in the tender for fuel production, however, the department subsequently chose to enter into direct negotiations with the operators of terminal facilities in Darwin. These negotiations were anticipated to have been completed in time to allow for facilities to be operational by 1 July 2012 which, in turn, would enable the contracts for increased production to commence.

19. Negotiations were lengthy and remained ongoing at the time the responsibility for petrol sniffing initiatives was transferred to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) in September 2013. An agreement for capital works was subsequently executed in December 2013, which enabled work to commence on developing the required storage infrastructure. The storage facility became operational in November 2014, more than two years later than expected. As a result of the delay, implementation of the expansion fell short of the Government’s initial expectations. The facility was also more expensive than first anticipated, with the contracted cost of establishing the bulk storage facility being up to $19.2 million (including GST)—exceeding significantly the initial estimates of up to $12.9 million. Following the establishment of storage facilities, additional production of LAF commenced in late November 2014 and PM&C anticipates that the annual volume of LAF produced in 2015–16 will double.

20. The department’s processes for managing existing contractual arrangements and for monitoring the delivery of LAF are largely sound. Information collected under the production and distribution agreements enables PM&C to maintain appropriate visibility over the volume of LAF supplied and the locations of sites to which it is supplied. The main approach of the PSS is to reduce the availability of RULP in high risk communities by encouraging fuel outlets serving those communities and outlets in surrounding areas to only stock LAF and create a distance buffer zone around vulnerable communities. Accordingly, PM&C monitors supply information so that sites ceasing to supply LAF can be contacted and encouraged to continue to participate in the PSS. In addition, since 2005, a contracted research provider has assessed a sample of communities periodically for incidences of petrol sniffing and the role of LAF in reducing outbreaks. As a result of these data collection arrangements, PM&C has a reasonable evidence base to support the assessment of LAF in reducing the incidence of petrol sniffing.

21. Between 2005 and 2009, the supply of LAF was identified as a program in the Health and Ageing Portfolio Budget Statements, and DoHA reported against the number of sites providing LAF as an indicator of performance for the PSS. Between 2009 and 2014 there was no formal reporting on the progress of the strategy. While the PSS has expanded, albeit more slowly than anticipated, there has been little information publicly reported on the effect that the supply of LAF has had on reducing the incidence of petrol sniffing in Indigenous communities. Research indicates that the supply of LAF is making a positive contribution to reducing petrol sniffing. The design of the PSS, however, also acknowledges that there are limitations to taking a single approach and that other actions need to be undertaken in conjunction with the supply of LAF to successfully address the issue of petrol sniffing. In 2014, the PSS was identified in the Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Budget Statements as a specific initiative to be delivered under the Safety and Wellbeing Programme, with the key performance indicator being the number of sites providing LAF. Using this narrowly-focussed indicator alone, however, will provide for only a limited assessment of performance. In view of the PSS’s maturity, it is timely for PM&C to strengthen its PSS-related performance reporting by including a greater focus on assessing the impact of the PSS.

22. The ANAO has made one recommendation to improve PM&C’s accountability and reporting for the PSS.

Key findings by chapter

Managing the Production and Supply Arrangements for Low Aromatic Fuel (Chapter 2)

23. PM&C has maintained appropriate administrative arrangements over the LAF component of the PSS, including planning and consultation for the roll out of LAF to new sites and for the monitoring of existing production contracts and distribution agreements. Information collected as part of the administration arrangements provides adequate oversight of the reach of the PSS and the distribution of LAF to sites. The volume of LAF distributed through the PSS has largely remained unchanged since 2007 as attempts to expand supply were hindered by the limited availability of appropriate bulk storage facilities in northern Australia.

24. Funding was provided to develop appropriate facilities in Darwin but delays in the establishment of these facilities affected the ability of the new contractor to produce LAF, and also effectively stalled the expansion of the supply of LAF to targeted communities. Nevertheless, since 2010–11, 32 sites have joined the PSS where there was a community need and logistical arrangements for delivery of LAF could be satisfied. Four of the 32 sites were part of the 39 targeted as part of the expansion of the PSS in 2010–11. Conversely, in 2013–14 nine sites stopped receiving LAF. PM&C advised that two of these sites switched to selling only premium unleaded and diesel fuel. Now that the bulk storage in Darwin is operational and additional LAF is being produced, PM&C has published a proposed timetable for 2015, identifying areas where LAF is to be introduced, including the remaining 35 sites that were initially targeted as well as additional areas identified since 2010–11.

Procuring the Production and Storage of Low Aromatic Fuel (Chapter 3)

25. In 2012, DoHA undertook a procurement process to increase the production of LAF and to address the bulk storage issues that had been identified as a barrier to expansion. Following a select tender, contracts were awarded in June 2012 to BP and in October 2012 to Shell (now known as Viva Energy Australia), with the production of additional LAF by Shell subject to establishing the bulk storage arrangements in Darwin. The process undertaken to approach the market to source suppliers of LAF was reasonable and the assessment of the tenders for the production of LAF was generally satisfactory. However, the subsequent decision to negotiate directly with the storage facility provider for the capital works was poorly documented and the tenderers informed sooner than they were.

26. Other documents generated at the time of, and subsequent to, the decision to negotiate directly for the construction of the bulk storage facility indicated that the reasons for this decision included reducing the risks and the costs of the procurement. Nonetheless, in 2011, a new bulk storage fuel tank was expected to cost between $6.2 million and $12.9 million13, but after a complex and difficult negotiation, the Government contracted for a cost of up to $19.2 million for the relocation and refurbishment of an existing biodiesel tank at the Darwin facility. It was not until mid-November 2014 that the storage facility became operational, over two years later than initially proposed, with a consequential delay to the expansion of the PSS.

Managing the Effectiveness of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy (Chapter 4)

27. Research and data collection arrangements to assess the effect of the provision of LAF are well-developed. Since 2005, a contracted research provider has assessed a sample of communities periodically for incidences of petrol sniffing. Also, when sniffing outbreaks occur in regional and remote Indigenous communities, these are investigated by the research provider, including validating the extent of the outbreak and identifying the source of the fuel. The arrangements were put in place at the commencement of the strategy and the periodic data collection in these communities has enabled an assessment of results in these communities over time.14 As a result of these data collection arrangements, PM&C has built up a reasonable evidence base to support the assessment of LAF in reducing the incidence of petrol sniffing.

28. Public reporting on the PSS has been sporadic. A selection of evaluation reports, or summaries, has been made publicly available following their completion. An interim report on the current data collection project was also published in 2013. Parliamentary interest has resulted in information being provided to Senate Committees and subsequently made publicly available through the release of Hansard transcripts. However, formal reporting to the Parliament has been limited. Between 2005 and 2009, the LAF component of the PSS administered by DoHA was considered a program for the purposes of the Portfolio Budget Statements and a key performance indicator, the number of sites with LAF, was established and formally reported against. Between 2009 and 2014, no formal reporting was undertaken for the PSS and the strategy was not considered as a program for the purpose of the Portfolio Budget Statements. For 2014–15, PM&C reinstated the indicator previously used by DoHA, but as a key performance indicator for the broader Safety and Wellbeing Programme under which the PSS is funded as a specific initiative.

29. An indicator using the number of sites with LAF is useful in terms of providing relevant information about the PSS’s footprint, but it does not support, by itself, an assessment of performance against the strategy’s broader objective. There is scope for PM&C to strengthen its public reporting by developing formal indicators that have a greater focus on the impact of the PSS in reducing the incidence and impact of petrol sniffing. Further information could be available to the public through: PM&C’s existing petrol sniffing website including information on the number of sites where LAF is available; the number of areas where RULP is no longer available within a defined distance; and the volume of LAF distributed. This would provide for a more rounded assessment of the use of LAF and the extent that the PSS has been successful in displacing RULP in targeted areas.

Summary of entity responses

Response from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

30. The Department agrees with the ANAO’s recommendation aimed at improving the accountability and reporting for the Petrol Sniffing Strategy. This recommendation, as well as the report as a whole, will be taken into account in the future planning and administration of the Strategy.

Response from Viva Energy Australia

31. Viva Energy Australia Ltd entered into a contract for the provision of up to 30 million litres of low aromatic fuel per year across northern Australia in October 2012, following a competitive tendering process. The Contract for Services with Viva Energy has been amended a number of times by mutual agreement of the parties, to enable the extension of the contract period to account for construction delays at the Vopak Darwin Terminal, to reflect the change of control in the Contractor from Shell to Vitol in August 2014, and to enable the change in both planned supply and storage locations.

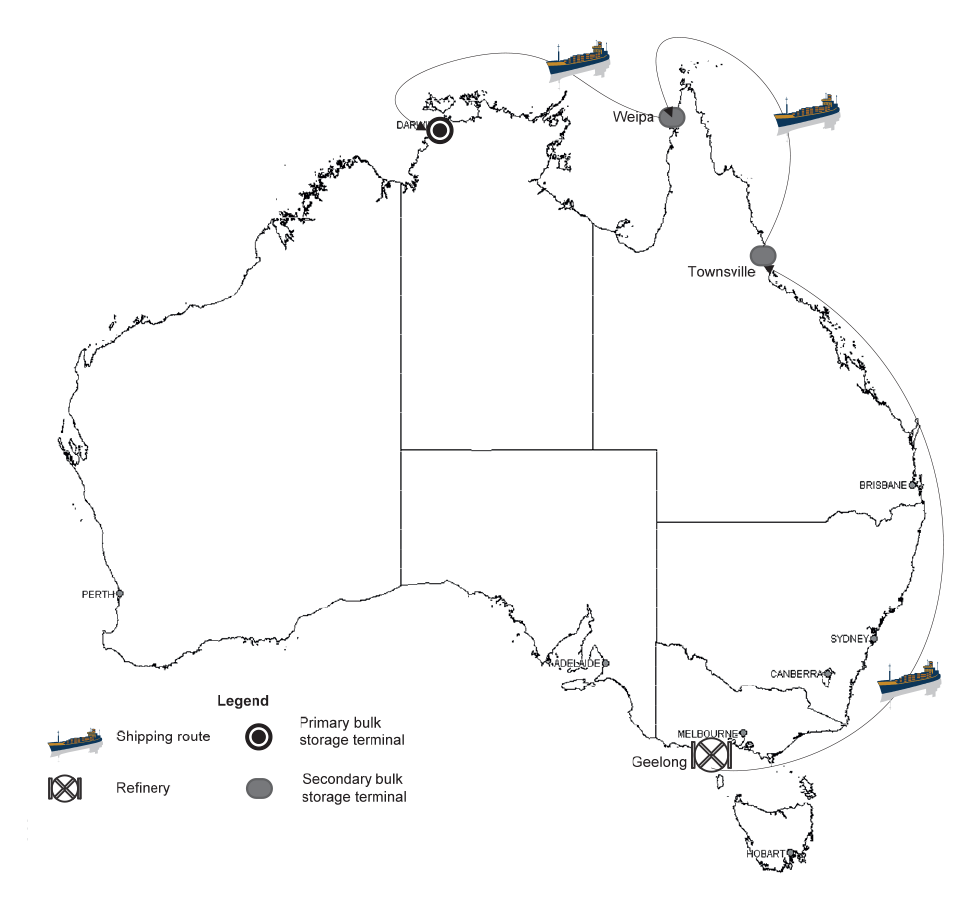

32. Practical Completion of the Vopak Darwin Terminal storage, which was a condition precedent to the Contract for Services, occurred on 17 November 2014. The supply of Low Aromatic Fuel to approved purchasers from the Darwin Terminal commenced on 21 November 2014, with supplies from the Weipa and Townsville Terminals following closely after in February and March 2015 respectively.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 4.25 |

In order to improve accountability and reporting for the Petrol Sniffing Strategy, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet:

Response from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides the background and context of the Australian Government’s Petrol Sniffing Strategy and outlines the audit objective, scope and criteria.

Background

1.1 In the late 1990s, remote Indigenous communities concerned about the incidence of petrol sniffing and its negative consequences requested assistance from the Australian Government to support efforts to tackle outbreaks. Petrol is a volatile substance that when inhaled induces a state of intoxication. The toxic chemicals in petrol, called hydrocarbons, rapidly enter the bloodstream through the lungs affecting the brain and central nervous system. The effects of petrol sniffing on communities include: increased rates of domestic violence; petty crime such as theft and vandalism; assaults; family and social disruption as well as affecting the health of the individuals involved in sniffing. Socially, the emotional and financial impacts on the community and the health and justice systems are significant, as is the cost of treating the short and long-term health effects of sniffing related harm.15

1.2 Petrol is generally readily available and required for use in everyday activities. International studies indicate that petrol sniffers tend to be young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and marginalised groups.16 The Senate Community Affairs References Committee in 2006 documented underlying causes of petrol sniffing in Indigenous communities as including: poverty and hunger; boredom; the cultural and social impacts of colonisation and interaction with the non-Indigenous community; a lack of employment and education opportunities; and social factors such as family breakdown, neglect, and peer group pressure.17 The sniffing of volatile substances is not confined to petrol. Other commonly available products known to create similar effects include aerosol sprays, such as deodorant, glue, spray paint and butane gas (lighter fluids). Addressing the use of these other volatile substances is not currently the primary focus of the Australian Government’s efforts to reduce petrol sniffing.

History of initiatives and policies

1.3 The impact of petrol sniffing on remote Indigenous communities was highlighted in the mid-1980s. In 1985, the Senate Select Committee on Volatile Substance Fumes reported that approximately 2000 children in Central Australia were sniffing petrol, representing about 10 per cent of all Indigenous children in the area at the time.18 When considered at the population level the number of Indigenous children sniffing petrol may not seem significant, but for a small remote community in which petrol sniffing may be endemic, the proportion of children engaged in petrol sniffing can be relatively high and the impact of their behaviours can devastate and dominate many aspects of community life.19

1.4 During the 1980s, some communities introduced a number of measures to tackle petrol sniffing, including: locking petrol bowsers; funding specific programs for petrol sniffers; and the addition of ‘ethyl mercaptan’, a sulphur-based stenching agent, to leaded petrol to deter people from sniffing.20 In the late 1990s, the Australian Government provided subsidised Avgas, a leaded aviation fuel, as a substitute for petrol under the Comgas Scheme to registered remote communities in the Northern Territory and South Australia. Avgas, produced by BP Australia Pty Ltd (BP), contained significantly fewer hydrocarbons in comparison to regular petrol and, consequently, the inhalation of Avgas did not induce intoxication.21 Whilst the Comgas Scheme was considered ‘a safe, effective, and popular intervention’,22 the high lead content and issues related to the suitability of use in motor vehicles meant that Avgas could not provide a long term solution.

1.5 To reduce the serious health risks from lead emissions generally, the Australian Government began phasing out leaded fuel across Australia in 2000 under the National Fuel Quality Standards Act 2000. From 1 January 2002, the sale of leaded fuels was prohibited. After the changes in the fuel standards, Avgas was no longer suitable for use in deterring petrol sniffing and BP developed a low aromatic, low lead alternative to regular unleaded petrol (RULP) with the brand name ‘Opal’. As a low aromatic fuel, Opal is a replacement for RULP, which is similar in terms of performance but contains fewer hydrocarbons that cause intoxication. Since the introduction of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy (PSS) in 2005, low aromatic fuel (LAF) has been progressively distributed throughout regional and remote communities. Funding from the PSS currently provides a subsidy23 for the production and distribution of LAF so that it is provided to consumers at the same price as RULP.

1.6 The persistent and pervasive nature of petrol sniffing, particularly in remote communities, has prompted intervention by every level of government. However, the need for a comprehensive approach was made clear by the Senate Community Affairs Committee in 2006:

the Committee believes that petrol sniffing in Indigenous communities has become so destructive and the need to find effective solutions is so urgent that the Council of Australian Governments must take responsibility for initiatives that address petrol sniffing.24

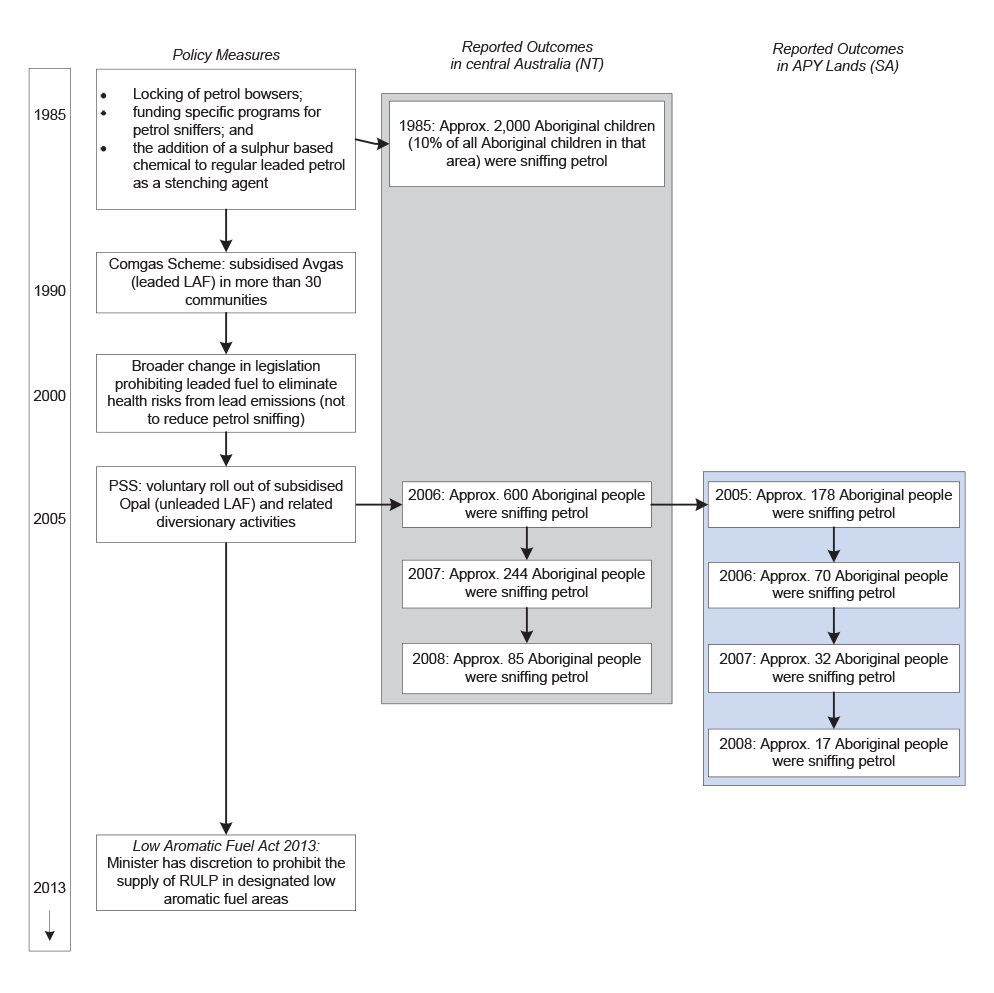

1.7 The range of supply reduction initiatives that has been undertaken by the Australian Government since 1985 to address petrol sniffing in regional and remote Indigenous communities is shown in Figure 1.1. Reported estimates of the progressive reduction in petrol sniffing in central Australia and the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands are also provided in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Australian Government supply reduction initiatives to address petrol sniffing, 1985–2014

Source: ANAO, compiled from reports of the Senate Select Committee on Volatile Substance Fumes (1985) and the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs (2009).

Notes: The 1985 figures in Figure 1.1 are taken from the Senate Select Committee on Volatile Substance Fumes, Volatile Substance Abuse in Australia, Canberra, 1985, p. 156.

The 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 figures in Figure 1.1 were taken from the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs, Grasping the Opportunity of Opal: Assessing the impact of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy, Canberra, 2009, pp. 7–8. These figures are approximate numbers of those engaged in petrol sniffing in selected communities and are not based on a census of all communities where individuals were known to be sniffing petrol.

The Petrol Sniffing Strategy and the supply of LAF

1.8 Building on the earlier Comgas Scheme, the Australian Government established the Petrol Sniffing Prevention Program (PSPP) in February 2005 as a mechanism to supply LAF to participating communities. The PSPP was implemented by the former Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) and became the department’s contribution to the broader whole-of-government Petrol Sniffing Strategy (PSS). The PSS was developed in September 2005 as a collaborative approach between the Australian and the Western Australian, South Australian and Northern Territory governments, with the objective of reducing the incidence and impact of petrol sniffing. Under the PSS, the respective jurisdictions agreed to focus on developing: consistent legislation; appropriate levels of policing; further roll out of LAF; alternative activities for young people; treatment and respite facilities; communication and education strategies; and strengthening and supporting communities and evaluation. These activities are collectively referred to as the Petrol Sniffing Strategy Eight Point Plan.

1.9 Prior to September 2013, the Australian Government contribution to the PSS was delivered by four departments. DoHA delivered the LAF component and undertook research and data collection; the former Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs was responsible for overall coordination of the strategy and providing funding for community strengthening initiatives; the Attorney General’s Department delivered the Indigenous justice components including the surveillance of trafficking in volatile substances and other drugs; and the former Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations provided education and work-related diversionary activities targeting youth at risk of sniffing.

1.10 Following the 2013 Federal election, responsibility for the delivery of Australian Government Indigenous programs was transferred to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C), including activities in relation to the PSS. Subsequently, Indigenous program funding arrangements were consolidated in 2014, which resulted in approximately 150 individual programs and activities being brought together into the Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS). Within the IAS there are five program areas, and organisations may apply for grant funding to support the delivery of relevant activities. Petrol sniffing activities generally fall within the Safety and Wellbeing Programme. While the IAS is mainly a grants program, the Government has agreed to implement specific initiatives through the program, including the supply of LAF. As at 21 April 2015, PM&C was negotiating agreements with various organisations for the provision of services under the IAS. Given the changes to Indigenous programs and the current state of negotiations with successful applicants, PM&C was not able to provide advice on the status of activities previously funded as part of the PSS Eight Point Plan such as Indigenous justice and diversionary activities for youth and community strengthening initiatives.

1.11 Since its establishment, the PSS has been periodically expanded to enable the supply of LAF to new areas. An initial 41 sites25, principally in the Central Desert Region26 received LAF in 2005.27 In the 2006–07 Federal Budget, $20.1 million over four years was allocated to extending the PSS to two more zones: the ‘Extended Central Desert Region’ and the East Kimberley. Additional sites in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland outside the identified priority areas were also supplied with LAF and included in the PSS during this time. A further $12 million over three years was allocated by the Australian Government to supply LAF to fuel outlets in Alice Springs from 2007–08. To address the need for continuing efforts to reduce the prevalence and incidence of petrol sniffing, the PSS became an ongoing Budget measure in 2008.

1.12 In May 2010, LAF was being supplied to 106 sites. As part of the 2010–11 Budget, the Australian Government announced a new Budget measure, Enhancing the Supply and Uptake of Opal Fuel 28, which committed a further $38.5 million to increase the supply of LAF and included funding to develop bulk fuel storage facilities in Darwin. The funding was intended to expand the PSS to an additional 39 sites covering 11 communities across the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia. As at January 2015, LAF was available at 138 sites. The distribution of current and planned LAF sites across the Northern Territory, South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland, as at January 2015, is shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Map of current and planned sites, as at January 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

Petrol Sniffing Strategy delivery arrangements

Production

1.13 LAF is similar to RULP with respect to its reported performance factors such as vehicle economy and efficiency. However, it has a higher cost of production than RULP because it requires additional refining and additives and is produced in smaller quantities. To maintain its production specifications, LAF requires separate distribution and storage arrangements.

1.14 Between, 2005–2012, the Australian Government subsidised BP for the production of LAF under a series of agreements. Over this period, the production subsidy reduced from $0.30 to $0.22 per litre. The details of the historical agreements are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Historical agreements with BP Australia Pty Ltd

|

Effective Date |

Subsidy rate Cents per litre |

Value of total contract ($m incl GST) |

Volume of LAF (megalitres) |

|

2005–06 |

30 |

1.3 |

4.3 |

|

2006–10 |

27 |

25.0 |

92.8 |

|

2010–12 |

27–221 |

9.5 |

42.1 |

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

Note 1: BP lowered the subsidy rate from 1 September 2012.

1.15 To support the expansion of the PSS, after a request for tender, DoHA entered into production, transport and storage contracts in 2012. With the new contractual arrangements, DoHA changed from providing a subsidy through a grant agreement to a fee for service model under contractual arrangements. The structure of the fee for service requires separate identification of the production, transport and storage charges to provide greater transparency.

1.16 In June 2012, DoHA entered into a contract valued at $23.2 million (GST inclusive) with BP to supply 24.6 megalitres per year. BP is contracted to supply the Western Australian Goldfields, South Australia and the Alice Springs region and does so using its refinery in Kwinana, Western Australia and bulk storage facilities in Largs North, South Australia and Kalgoorlie, Western Australia.

1.17 A new supplier was also contracted following the tender process. The Shell Company of Australia Ltd (Shell, now known as Viva Energy Australia29) entered into a contract in October 2012 valued at $41.8 million (GST inclusive) to supply 28.6 megalitres of LAF per year to the Top End of the Northern Territory, the Gulf of Carpentaria and Cape York as well as the East Kimberley for four years. Viva Energy commenced production of LAF at its Geelong refinery in Victoria in November 2014 and uses storage facilities in Darwin, Weipa and Townsville.

1.18 From 2015, the PSS will rely on five bulk storage terminals from which LAF is sold to approved purchasers.30 Producers will be paid for LAF sold from terminals, with the service fee varying to reflect the relative costs involved in transporting and using different bulk storage facilities. The service fees (covering the additional costs of the production of LAF, as well as the transportation and storage) range from $0.21 to $0.94 per litre.

Distribution

1.19 The distribution of LAF is generally by road, with distributors purchasing the fuel from bulk storage terminals and transporting it to fuel outlets. The LAF supply is not easily adapted to the existing distribution channels due to the need for separate storage facilities and compartments in tankers, which result in increased cost. The logistical complexities of incorporating comparatively small volumes of LAF over vast distances in already established distribution routes has resulted, in the past, in lost efficiencies and higher costs for distributors. Prior to the availability of multiple bulk storage facilities, the Australian Government provided subsidies to distribution companies to offset the additional costs of transport to assist in delivering LAF to consumers at the same price as RULP.

1.20 In 2013–14, eight distributors were paid subsidies to transport LAF from the BP terminal in Largs North, South Australia to fuel outlets as far away as Palm Island in Queensland and Kalumburu in Western Australia. The established scale of subsidies ranges from $0.08 to $0.30 per litre, but distribution to some sites may attract a higher rate of subsidy. In special circumstances, subsidies up to $0.61 per litre have been paid. Approximately $2 million in distribution subsidies was paid in 2013–14. With bulk storage facilities in Darwin being completed in late October 2014, PM&C advised that the distribution subsidy arrangements are expected to be phased out during 2015 and that further subsidies would be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Storage

1.21 A necessary underpinning for efficient distribution of LAF is being able to access bulk storage facilities at key distribution points. Bulk storage allows shipments of LAF to be delivered and stored for routine deliveries to fuel outlets. Until late 2014, BP provided LAF through its own storage facilities in Largs North, South Australia and in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. Expanding the supply of LAF into northern Australia under the contract with Shell (Viva Energy) required the provision of sufficient bulk storage in Darwin, Cape York and the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Government commenced negotiation for the establishment of key storage facilities in Darwin in August 2011 and the agreement with Vopak Terminal Darwin Pty Ltd (Vopak) was executed in December 2013 at a contracted cost of up to $19.2 million. The major storage facility in Darwin was completed in late October 2014 and became operational in November 2014. An example of a bulk storage tank is shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Bulk storage fuel tank

Source: Photo taken by ANAO, Botany, Sydney 2014.

Legislation

1.22 In targeted regional and remote areas where LAF has been rolled out, the majority of fuel outlets have participated voluntarily. Some outlets, however, have chosen not to stock the fuel, creating a potential supply pathway for RULP into vulnerable communities which may reduce the effectiveness of efforts to control petrol sniffing. In March 2012, a Private Member’s Bill, the Low Aromatic Fuel Bill 2012, was passed by Parliament and received Royal Assent on 14 February 2013.31 The Low Aromatic Fuel Act 2013 (the Act) provides the responsible Minister32 with discretionary powers to designate a fuel control area and to determine the requirements relating to the supply, transportation, possession and storage of fuel in those areas. The Act aims to promote the supply of LAF in designated areas by prohibiting the supply of RULP. Powers under the Act have not been used as at April 2015 and the PSS continues to operate on the basis of voluntary participation. PM&C advised that two outlets previously reluctant to participate in the PSS voluntarily switched to supplying LAF after the bill passed.

Previous reviews and evaluations of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy

1.23 Various aspects of the PSS have been reviewed since 2005. Two Senate Committees have reviewed the effectiveness of the PSS, once in 200633 and again in 2009.34 As mentioned previously, DoHA commissioned the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies to undertake a cost benefit analysis of the introduction of legislation to mandate LAF.

1.24 Since 2005, a contracted research provider has periodically assessed a sample of communities for incidences of petrol sniffing.35 The analysis conducted includes examining the contribution of LAF in reducing the incidence of petrol sniffing in specific communities. As well as continuing data collection, a whole of strategy evaluation was undertaken, with the final report released in 2013.36 This evaluation considered the future directions of the PSS and made 12 recommendations. The management of relevant agreements for the supply and distribution of LAF was not included in previous evaluations.

Administrative role of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

1.25 PM&C is responsible for the implementation of the Australian Government components of the PSS, including providing advice and information on the strategy as requested by the Minister and the Parliament. With regard to the provision of LAF, PM&C’s main functions include:

- managing the contracts for the production of LAF;

- managing the subsidy agreements with petrol distributors;

- negotiating and managing the capital works agreement for the construction of the bulk storage facility in Darwin;

- preparing communities to receive LAF, including roll out activities;

- developing and managing the communication strategy; and

- managing the ongoing research and data collection for the PSS to assess the effectiveness of the provision of LAF.

1.26 Annual expenditure for the LAF component of the PSS over the last two financial years has been on average $24 million. Expenditure for 2014–15 is also expected to be approximately $24 million.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.27 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s management of initiatives to supply low aromatic fuel to Indigenous communities.

Scope

1.28 The audit focussed on the administration of arrangements to support the supply and distribution of LAF following the expansion announced in the 2010–11 Budget. In particular, the audit examined the procurement process conducted in 2011 for the production, transport to storage and storage of LAF which resulted in the contracts and agreements referred to in paragraphs 1.15–1.17 and 1.21. The audit also examined the monitoring and reporting arrangements for the PSS, particularly in relation to the supply of LAF.

Audit Criteria

1.29 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO assessed whether the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet had:

- effective service delivery arrangements in place to supply LAF to identified Indigenous communities;

- effective arrangements to implement the expansion of the PSS; and

- effective arrangements in place to monitor the supply of LAF and assess the impact of its supply in line with the Government’s expectations.

Methodology

1.30 The methodology encompassed analysing key documents, including relevant departmental and contract decisions, planning and monitoring documents, performance data collected by the department and agreements between PM&C and relevant providers. The audit team also interviewed PM&C staff responsible for the PSS and selected stakeholders.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost of $421 360.

Report structure

1.32 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Chapter Two Managing the Production and Supply Arrangements for Low Aromatic Fuel |

This chapter examines PM&C’s management arrangements for the production and supply of low aromatic fuel under the Petrol Sniffing Strategy. |

|

Chapter Three Procuring the Production and Storage of Low Aromatic Fuel |

This chapter discusses the procurements undertaken for production and storage of low aromatic fuel to expand the Petrol Sniffing Strategy. |

|

Chapter Four Managing the Effectiveness of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy |

This chapter discusses PM&C’s arrangements to collect information to assess and report on the performance of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy. |

Source: ANAO.

2. Managing the Production and Supply Arrangements for Low Aromatic Fuel

This chapter examines PM&C’s management arrangements for the production and supply of low aromatic fuel under the Petrol Sniffing Strategy.

Introduction

The Petrol Sniffing Strategy

2.1 The objective of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy (PSS) is to reduce the incidence and impact of petrol sniffing. Since 2005–06, the key component of the PSS has been the supply of low aromatic fuel (LAF) to reduce or avoid outbreaks of petrol sniffing. This approach involves supplying LAF to fuel outlets in, and surrounding, vulnerable communities to provide a distance barrier for access to regular unleaded petrol (RULP).37 This reduces the risk of vehicles containing RULP entering, or being accessible by, Indigenous communities which could lead to a petrol sniffing outbreak. Implementing, the strategy involves the consultative and logistical arrangements to bring LAF to an identified area, and monitoring of contractual arrangements for supply. As at January 2015, 138 sites were receiving LAF, servicing 78 Indigenous communities. The administrative processes in place to manage the supply of LAF were developed within the former Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) and have been maintained by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

Introducing LAF to identified communities

2.2 Communities identified to receive LAF are either located in target areas that were identified during the development of the PSS or are communities where there have been recent outbreaks of petrol sniffing, which then warrant the introduction of LAF. In either case, for LAF to be introduced there needs to be support from the community. Where there has been an outbreak, typically PM&C receives notification directly from stakeholders, or concerned community members. Once a community or region is identified for the PSS, the process of introducing LAF commences. This usually begins with PM&C field staff visiting the communities for discussions with local stakeholders, including: community-based organisations; schools; police; local community leaders; and local councils, business associations and fuel outlets.

2.3 After the initial visit, planning then commences, including an assessment of the logistics required to have LAF delivered, general community agreement and whether the local fuel outlets will agree to stock LAF. PM&C has two staff working in the field with regional and remote communities to implement the PSS. The field staff develop a detailed plan which includes: demographic information about the community and the region, the fuel outlets encompassed within the area; the approach to providing LAF; communication strategies; and risk assessments.

2.4 The PSS is voluntary38 with fuel outlets needing to agree to stock and sell LAF in lieu of RULP before sites can participate. Some fuel outlets choose not to sell LAF, which has the potential to reduce the effectiveness of the strategy. Research undertaken in 2008 indicated that there was a ‘statistically significant relationship between the distance of each community to the nearest [RULP] outlet and the size of the decrease in the prevalence of sniffing …’39 Even though LAF may be available in a community and in some neighbouring fuel outlets, RULP from other sites can on occasion enter communities and trigger a petrol sniffing outbreak.

2.5 PM&C has little formal interaction with fuel outlets once LAF is stocked. Some promotional materials may be provided to fuel outlets, however, there is minimal departmental communication with outlets and acknowledgement of fuel outlets continued participation and support for the PSS is not currently part of the administration of the strategy. PM&C advised that sites are monitored through fuel deliveries and issues are followed up through the department’s regional network. PM&C also advised that, where necessary, it maintains contact with community stakeholders, data collectors and other partners on the ground who maintain relationships with fuel outlets.

Communications strategy 2014

2.6 In support of the voluntary approach for participation, the 2010–11 Budget announcement Enhancing the Supply and Uptake of Opal Fuel, which provided funding for an expansion of the strategy, also included funding for the establishment of a communication strategy to inform the community on the use of LAF. As discussed later in paragraph 2.35, the expansion of the roll out of LAF was delayed and, as a result, the release of the communications strategy was aligned with the timing of the bulk storage in Darwin becoming operational in late 2014. In September 2014, PM&C put in place its ‘Rollout of Low Aromatic Unleaded Fuel Communications Implementation Plan 2014–15’ to support the expanded roll out of LAF in northern Australia. The communication strategy is supported by research into the various groups affected by the introduction of LAF, including tourists, Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members, motorist associations and other professional bodies. The plan explains that negative perceptions about LAF have existed for some time and seeks to address these by focusing on the key concerns for most consumers, such as price equivalence to RULP and performance in engines. The communication plan is a necessary foundation for the expansion of LAF as it assists in educating key stakeholders and the public about the PSS and the use of LAF.

Low Aromatic Fuel Act 2013

2.7 Although a voluntary approach to the stocking of LAF has been adopted, during 2006–08 the then Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) considered the option of using legislation to enable the Australian Government to regulate the sale of RULP and mandate the use of LAF. In 2008, DoHA decided to examine the costs and benefits of enforcing the sale of LAF through legislation and commissioned the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies to undertake analysis. The report, Cost Benefit Analysis of Legislation to Mandate the Supply of Opal Fuel in Regions of Australia, was released in January 2010. The report included an examination of which jurisdiction was better placed to legislate, with strong support for the Commonwealth to do so, and identified a range of practical implementation considerations. The researchers modelled the benefits of a ban noting that ‘… the ban on RULP would have a net benefit so long as it reduced sniffing by at least 19 per cent from current [2009] levels.40 The then government decided not to proceed with introducing legislation.

2.8 In response to concerns about continued petrol sniffing, a Private Member’s Bill41 was introduced in March 2012 to Parliament. The Low Aromatic Fuel Bill 2012 sought to regulate the supply of LAF in certain areas and received Royal Assent on 14 February 2013. The Low Aromatic Fuel Act 2013 (the Act) is discretionary legislation which requires the responsible Minister to take specific actions before fuel can be regulated in a particular area. To exercise power under the Act, the Minister would need to develop a legislative instrument, which would define a LAF area or ‘Fuel Control Area’. The legislation requires adequate consultation and outlines the groups of people to be consulted.42 PM&C has developed draft guidelines which describe the circumstances when the legislation could be used, if the Minister so desired.

2.9 Powers under the Act have not been used as at April 2015, however, PM&C advised that two outlets previously reluctant to participate in the PSS voluntarily switched to supplying LAF after the bill passed. PM&C continues to seek voluntary agreement from outlets to stock LAF and could consider refinement of its approach to better focus on fuel outlets and their voluntary participation as well as their ongoing involvement in the strategy.

Administration of the LAF element of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy

2.10 As discussed in paragraph 1.25, administration of the LAF component of the PSS includes PM&C managing contracts and payments to fuel producers for the production and supply of LAF. PM&C also has oversight of agreements with fuel distributors and monitors the supply and distribution of LAF. PM&C’s administrative processes to support the provision of LAF are discussed in the following sections. In relation to the production contracts, only the arrangements in place for BP were examined by the ANAO. As at December 2014, although production had commenced no invoicing had occurred under the contract with Viva Energy for the production of LAF.

Supply of LAF under the BP contract

Management arrangements

2.11 Between 2005 and November 2014, BP Australia (BP) was the sole producer of LAF in Australia. BP manufactures the fuel at its Kwinana Refinery near Perth, Western Australia, and sells LAF to distributors through its bulk storage facilities at Largs North, South Australia and Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. Under the current contract, BP is required to produce enough LAF to meet demand in the nominated regions of Central Australia, South Australia and the Western Australian Goldfields.43 It is also required to have fuel available 95 per cent of the time for distribution. LAF must meet the National Fuels Quality Standards Act 2000 for RULP in accordance with industry best practice and BP is to provide ongoing assurance of the quality of LAF produced. In its August 2013 annual report to PM&C, as required by the contract, BP reported that LAF had been tested four times during the year. However, BP has not reported on the testing since that time. PM&C advised the ANAO that it will require BP to include information on the quality testing results in its regular contract reporting.

2.12 PM&C monitors the production and supply of LAF through reports provided by BP, which accompany the monthly invoices. These reports include information on the volume of LAF sold to each distributor, as well as providing stock on hand figures for its two bulk storage facilities and refinery. Management arrangements with BP include regular teleconferences to discuss issues as well as ad hoc contact to address matters that arise.

Invoice processing for BP

2.13 Under the contract, BP must supply a correctly rendered tax invoice each month in order to be paid. The invoice must be accompanied by an operational report which is to include details on the volume sold, date of sale, distributor details, and total fee amount claimed. In addition, BP provides half yearly reports outlining technical advice provided, logistical assistance to government and industry stakeholders and marketing and communications activities.

2.14 PM&C creates purchase orders to establish an annual ceiling on expenditure for the BP contract, which is calculated at approximately a quarter of the total contract amount of $21.1 million. In 2013–14, the annual amount committed was $4.9 million. Actual expenditure for that year was $3.9 million. Payments over the annual estimated amount would require additional approval from the delegate and a variation to the original purchase order. In effect, the monetary limit established by the purchase order acts as an overarching payment control mechanism, limiting routine payments to a set amount for the year.

2.15 As LAF consumption is demand driven, estimates are needed to first establish the volume required and then the associated subsidy costs for financial and logistical purposes. The estimated and actual annual costs between 2009–10 to 2013–14 are shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Forecast and actual LAF production subsidies 2009–10 to 2013–14

|

Financial year |

Estimate $ (million) |

Actual $ (million) |

|

2009–10 |

7.2 |

5.9 |

|

2010–11 |

8.0 |

4.9 |

|

2011–12 |

8.5 |

4.6 |

|

2012–13 |

6.5 |

4.2 |

|

2013–14 |

4.9 |

3.9 |

Source: ANAO from analysis of PM&C information.

2.16 In 2010–11, additional funding was committed to expand the PSS. DoHA increased the estimated volume over the following years in anticipation of a major expansion which would bring LAF to new sites. The expansion was, however, delayed and the overall downward trend in annual expenditure as shown in Table 2.1 is a result of several factors including a decrease in volume produced and reductions in the subsidy amounts paid to BP (paragraph 1.14 refers).

2.17 The current contract does not require BP to produce more than the agreed amount of 24.6 megalitres per year. Monthly analysis of the invoices and accompanying reports allows PM&C to anticipate whether more funds will be required as well as monitoring volumes of LAF produced and distributed.

2.18 Payments to BP for the LAF produced are generally made monthly in arrears once an invoice is received, validated and then approved for payment. Validation of invoices relies on the operational report, which specifies the volume of LAF sold and each distributor’s details along with individual invoice numbers and amounts. In turn, distributors also invoice PM&C to receive a subsidy and nominal reconciliations are carried out over the financial year using the volumes distributed.

Management of distribution arrangements

2.19 LAF is sold in relatively small volumes and is delivered to outlets in remote areas which are often difficult to access. As such, distributing LAF requires special arrangements that differ from the distribution of other fuels. Distributors generally carry several grades of fuel in a load, the volume of which is calculated to provide the greatest economy per delivery. The introduction of a new grade of fuel to the supply chain can create inefficiencies and some challenges for fuel distributors. Prior to the introduction of LAF, the Australian Government provided subsidies to fuel sites supplying Avgas in participating communities. These subsidy arrangements were continued for LAF with the subsidy being paid directly to distributors on a cents per litre basis to help meet the additional costs associated with the distribution of LAF. As a result of the establishment of additional bulk storage facilities in Darwin, Townsville and Weipa, PM&C anticipates that subsidies to distributors will be phased out during 2015, with further subsidies considered on a case-by-case basis.

2.20 Not all distribution companies received the PSS distribution subsidy, as only those that were required to travel out of normal routes or extended distances were eligible. To receive a subsidy, a fuel distribution company had to be delivering to an area designated as attracting a subsidy (refer Figure 2.1). The company then needed to enter into a subsidy agreement and supply information about LAF deliveries and provide invoices on a monthly basis to receive the subsidy. Some distribution companies did not receive a subsidy for every LAF site they delivered to as their delivery sites were close to bulk storage terminals. In 2013–14, 47 per cent of LAF sites attracted a distribution subsidy.

Subsidy rates for distribution

2.21 The scale of subsidies was based on the historical arrangements implemented under the Comgas Scheme from 1998–2005 and generally ranged from $0.08 to $0.30 per litre, depending on the location of the fuel outlet. Higher rates have been paid on a case-by-case basis. For example, distribution of LAF to Nhulunbuy required the fuel to travel overland from Adelaide to Darwin and then be shipped by barge. Under the 2014 distribution arrangements, the distributor received a $0.47 per litre subsidy to get the fuel from Adelaide to Nhulunbuy, $0.17 per litre more than most other sites in northern Australia.44 Also in 2014, as an interim arrangement, LAF distribution to Palm Island attracted a $0.61 per litre subsidy because the LAF was trucked from Largs North in South Australia to Townsville in Queensland and then shipped in containers to the island.45 The subsidy amounts in place in 2013–14 and corresponding regions of Australia are shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Distribution subsidy amounts by region 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C data.

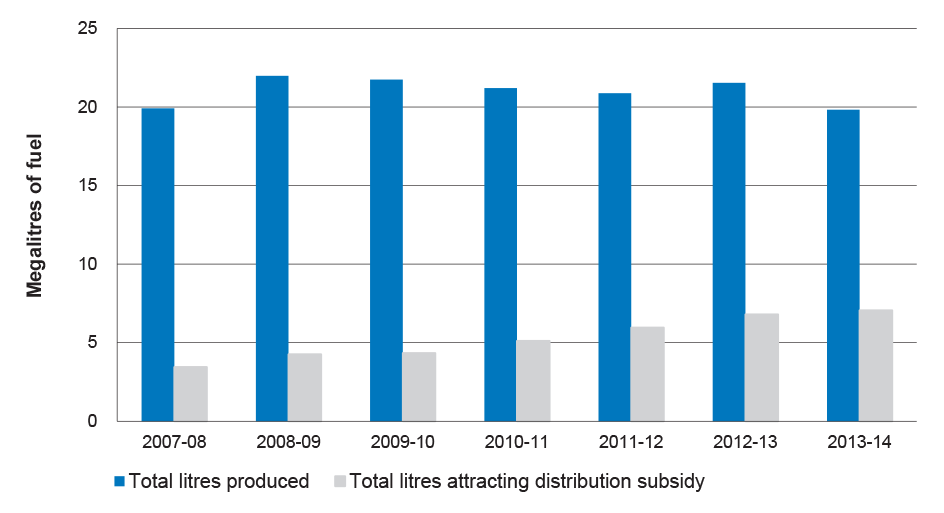

2.22 During 2013–14, PM&C had subsidy arrangements with eight distributors, a decrease in the number from previous years.46 The department informed the ANAO that smaller distributors appeared to be ceasing to deliver to uneconomical sites with larger distributors picking up those delivery sites. While the volume of LAF produced has remained steady between 2007–08 and 2013–14, the subsidies paid to distributors rose from $1 million in 2007–08 to approximately $2 million in 2013–14. The department advised that the rise in subsidies paid to distributors was due to the expansion of the supply of LAF over this period to sites located further away from the supply point. The department also advised that it intends to undertake further analysis of this issue in 2015. The volume of fuel produced, and the volume of fuel distributed which required a subsidy from 2007–08 to 2013–14 is shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Volume of fuel produced and volume of fuel attracting a distribution subsidy, 2007–08 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

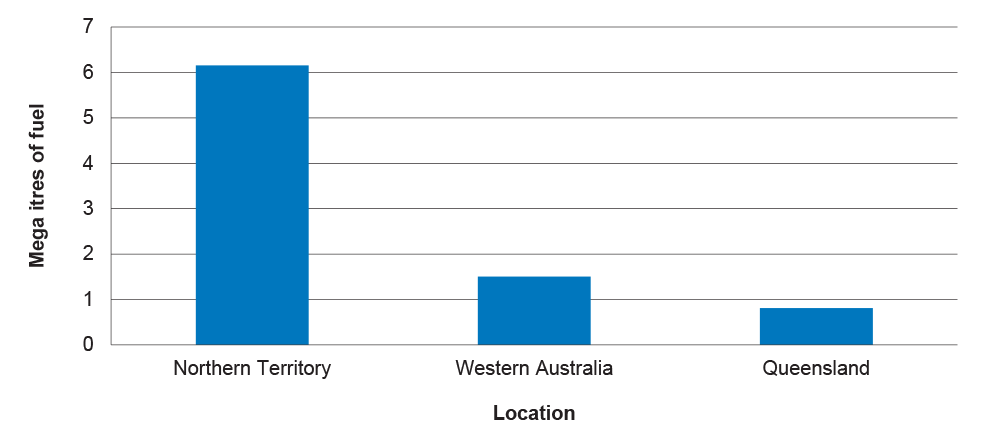

2.23 The majority of LAF sites that required a distribution subsidy in 2013–14 were in the Northern Territory, with lower volumes of LAF requiring subsidies in Western Australia and Queensland. The volume of fuel requiring a distribution subsidy by location in 2013–14 is shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Volume of fuel that required a distribution subsidy, by location in 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

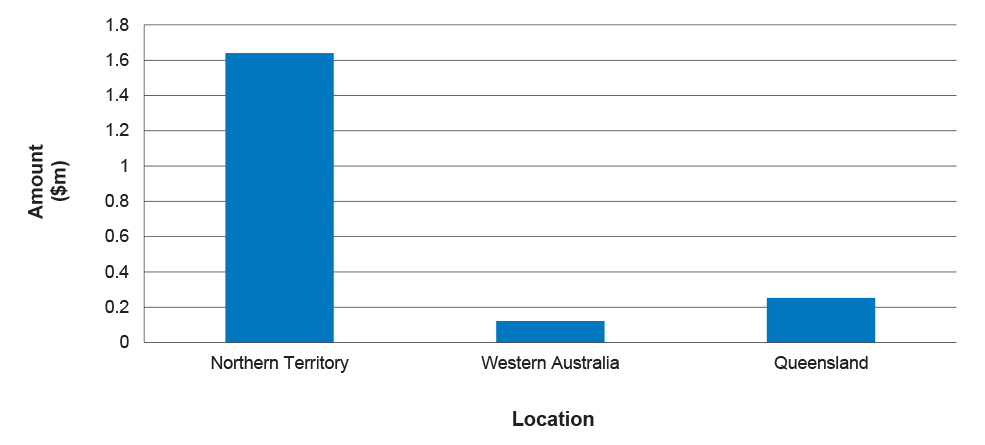

2.24 PM&C spent approximately $1.6 million subsidising the distribution costs to supply LAF to around 42 sites in the Northern Territory. The spread of distribution costs between locations is shown in Figure 2.4. LAF distributed to Western Australia and Queensland also attracted a distribution subsidy, and although Western Australia received a higher volume of LAF across the 15 sites that attracted a subsidy, the sites in Western Australia were generally closer to the distribution point. Accordingly, the distribution subsidies were lower.

Figure 2.4: Distribution costs by location, 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

Distribution agreements

2.25 Until 2015, distribution agreements were entered into on an annual basis, which meant that distribution companies had to re-sign agreements to continue to access the subsidy. While the rate of subsidy did not change, it was possible that new sites could be added to a distributor’s approved delivery list. Multi-year agreements may have reduced the administrative effort for distribution companies but PM&C advised that annual agreements provided more flexibility to revise the subsidy arrangements when required.

Monitoring the supply and distribution of LAF

2.26 A key additional benefit of PM&C’s agreements with fuel distribution companies is the supply of information on the volume of fuel supplied and to which sites. For example, in 2013–14, distributors had to complete a distributor statement and submit this with the invoice for payment. The distributor statement is a template prepopulated with the approved PSS site names and corresponding subsidy amounts applicable to that distributor. Each month the distributor supplied the details of sales to respective sites, including document numbers, date of sales and volume of delivery along with a tax invoice.

2.27 As well as acting as a payment support mechanism, this data is useful for oversight of the PSS and PM&C compares the total volume of fuel produced to the amount distributed in a financial year. The information provided on volumes of LAF delivered is also useful for estimating future demand and for the monitoring the continued participation of fuel outlets so that if a fuel outlet did not receive a delivery of LAF over a period of time, the department has the capacity to follow up. For example, an outbreak of petrol sniffing may be traced to a site that has stopped supplying LAF. In August 2014, PM&C wrote to distributors regarding the potential changes to the subsidy arrangements once the new bulk storage tank in Darwin became operational. Following on from its correspondence to distributors, PM&C advised that the distribution subsidy is expected to cease in early 2015. Once the subsidy arrangement ceases PM&C will no longer readily receive information about distribution of LAF and the participation of fuel outlets.

Expansion of the Petrol Sniffing Strategy

2.28 In the 2010–11 Federal Budget, the Government made available an additional $38.5 million over four years (2010–14) to enable increased production of LAF and to provide additional storage capacity in order to support an expansion in the supply of LAF to 39 targeted sites covering 11 communities, mainly in northern Australia.47 The additional funding across the four years 2010–14 is set out in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Budget allocation for the expansion of low aromatic fuel, 2010–11 Budget

|

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

Total |

|

Administered |

5 210 000 |

7 444 000 |

11 513 000 |

11 661 000 |

35 828 000 |

|

Departmental |

781 000 |

715 000 |

616 000 |

561 000 |

2 673 000 |

|

Total |

5 991 000 |

8 159 000 |

12 129 000 |

12 222 000 |

38 501 000 |

Source: Health and Ageing Portfolio Budget Statement, 2010–11, p. 45.

Development of additional bulk storage facilities

2.29 From 2006 to 2014, the supply chain to provide LAF to northern Australia involved distributors collecting LAF from the BP storage terminal at Largs North, South Australia and transporting the fuel long distances by road. Largs North had been the primary distribution point, selling 175 megalitres of LAF between 2005–14. However, fuel producers had raised concerns about the safety of transporting the fuel such long distances on a regular basis. Other considerations in transporting the LAF from southern Australia included the security of the supply chain, as increasing the length of the supply chain exposes distribution companies to a higher risk of stock running out.

2.30 A map of the distribution arrangements for LAF to December 2014 is shown at Figure 2.5. LAF was typically collected from Largs North in South Australia and transported by road to Alice Springs and Darwin in the Northern Territory before being distributed in smaller amounts to remote areas.

Figure 2.5: Distribution arrangements to supply targeted communities in northern Australia until December 2014

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

2.31 The barrier posed by limited storage facilities was a finding of a Senate Inquiry in 2009 into petrol sniffing, which included an examination of the progress of the provision of LAF. The inquiry found that:

… without the construction of a dedicated bulk storage facility in Darwin the costs and supply chain logistics associated with distributing [LAF] to northern Australia will be prohibitive and unnecessarily complicated.48

2.32 In 2010, another report commissioned by DoHA recommended that an additional bulk storage site in Darwin was needed to make LAF more accessible to sites that would ordinarily source other fuel grades from Darwin.49 Establishing a bulk storage facility for LAF in Darwin would also reduce the need for the distribution subsidies as DoHA considered that the additional costs associated with the bulk storage of LAF closer to sites in northern Australia would be offset by lower distribution fees associated with transporting LAF directly from Adelaide.

2.33 After consultation with industry, DoHA identified that Darwin was the best location for bulk storage of LAF as it was the main fuel distribution hub for northern Australia and accessible by both land and sea. The bulk storage fuel terminal is owned by an independent company that stores fuel for all fuel companies operating in the region. It was also recognised that smaller storage facilities were needed in the Gulf of Carpentaria and Cape York.

2.34 In the seven years between 2007–08 and 2013–14, $11.2 million was paid in distribution subsidies, or an average of $1.6 million per year. In 2011, DoHA anticipated that the cost of a new five million litre bulk storage tank in Darwin would range from $6.2 to $12.9 million.

Expansion of the PSS

2.35 Between 2010–11 and January 2015, 32 sites joined the PSS where there was a community need and where logistical arrangements for supply could be satisfied. Four of these 32 sites were among the 39 sites targeted as part of the expansion in the 2010–11 Budget measure. The remaining 35 sites, which were delayed because storage facilities in northern Australia had not been constructed, are expected to receive LAF during 2015. Of the 11 communities targeted in the 2010–11 Budget measure, three are scheduled to receive LAF during 2015. In 2013–14 nine sites previously participating in the PSS chose not to continue to supply LAF. PM&C advised that two of these sites switched to selling only premium unleaded and diesel fuel.

2.36 While the number of sites receiving LAF from 2010–11 increased, the annual volume of production of LAF largely remained stable, with a slight reduction in 2013–14 to below the 2007–08 levels. This indicates that some sites may be selling less LAF. The average production since 2007–08 was 21 megalitres per annum. No targets have been set in relation to the volume of LAF produced and distributed, although contracts with LAF producers signed in 2012 allow for an annual production of up to 53 megalitres. The volume of LAF produced from 2007–08 to 2013–14 is shown at Figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6: Volume of LAF produced from 2007–08 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

2.37 The volume produced for 2007–08 to 2013–14 along with the corresponding production and distribution subsidies is shown in Table 2.3. Over the period 2007–08 to 2013–14, the cost to the Australian Government for both production and distribution subsidies was $45.9 million, or approximately $0.31 per litre. As the Darwin bulk storage facility became operational in November 2014, additional production of LAF commenced. While there are no targets set for the volume of LAF, the contracts in place allow for annual production to increase a further 28.6 megalitres bringing contracted maximum volume to 53.2 megalitres per year.

Table 2.3: LAF production volume and subsidies 2007–08 to 2013–1450

|

Year |

Megalitres |

Production Subsidy $ (million) |

Distribution Subsidy $ (million) |

Total Subsidy $ (million) |

|

2007–08 |

19. 9 |

5.2 |

1.0 |

6.2 |

|

2008–09 |

22.0 |

5.9 |

1.3 |

7.2 |

|

2009–10 |

21. 7 |

5.9 |

1.5 |

7.4 |

|

2010–11 |

21. 2 |

4.9 |

1.6 |

6.5 |

|

2011–12 |

20.9 |

4.6 |

1.9 |

6.5 |

|

2012–13 |

21.5 |

4.2 |

2.0 |

6.2 |

|

2013–14 |

19.8 |

3.9 |

2.0 |

5.9 |

|

Total |

147.0 |

34.6 |

11.3 |

45.9 |

Source: ANAO analysis of PM&C information.

Conclusion

2.38 To support the supply of LAF, PM&C has maintained appropriate administrative arrangements. These arrangements were largely developed by the former DoHA and adopted by PM&C following the transfer of Indigenous program responsibilities in September 2013. These arrangements provide for the introduction of LAF into communities, including the development of plans that identify the geographic boundaries of the community, the key stakeholders and other relevant information. With two field staff responsible for this aspect of the strategy, PM&C has only a limited ability to maintain contact with fuel outlets once LAF has been rolled out, even though their continued participation is important to the success of the PSS.

2.39 The processes in place to manage the contracts for production and distribution of LAF are largely sound and allow for the supply of LAF to participating sites. Information gathered from monitoring existing contracts for LAF provide PM&C with valuable data on the reach of the PSS, including oversight of where LAF is available and the volumes provided. This information is also used for planning and budgeting purposes.

2.40 Overall, the volume of LAF production has largely remained stable over the life of the PSS, with 21 megalitres on average supplied per annum. While contracts signed in 2012 have provision for annual production of up to 53 megalitres of LAF, targets are not used for monitoring the performance of the PSS. From an initial 41 sites in June 2005, the strategy expanded and, as at January 2015, LAF was available in 138 sites associated with 78 Indigenous communities in Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory. The slow progress in establishing the bulk storage facility in Darwin has limited the operation of the contract to increase production and delayed the introduction of LAF to 35 of the 39 targeted sites identified in the 2010–11 Budget announcement Enhancing the Supply and Uptake of Opal Fuel. Since 2010–11, 32 fuel outlets have joined the PSS, four of which were among the 39 targeted sites. Conversely, in 2013–14 nine sites stopped receiving LAF. PM&C advised that the department will follow up with these fuel outlets to determine the reasons why they are no longer receiving LAF. With the expansion of the PSS now to occur mainly in 2015, PM&C has published a broad timetable for the supply of LAF to identified areas, which includes the remaining 35 sites.

3. Procuring the Production and Storage of Low Aromatic Fuel